Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:36

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Cognitive Learning Strategy as a Partial Effect on

Major Field Test in Business Results

Kenneth David Strang

To cite this article: Kenneth David Strang (2014) Cognitive Learning Strategy as a Partial Effect on Major Field Test in Business Results, Journal of Education for Business, 89:3, 142-148, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2013.781988

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2013.781988

Published online: 06 Mar 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 96

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2013.781988

Cognitive Learning Strategy as a Partial Effect

on Major Field Test in Business Results

Kenneth David Strang

State University of New York, Queensbury, New York, USA

An experiment was developed to determine if cognitive learning strategies improved stan-dardized university business exam results. Previous studies revealed that factors such as prior ability, age, gender, and culture predicted a student’s Major Field Test in Business (MFTB) score better than course content. The experiment control consisted of identical syllabi and fac-ulty (except for the treatment). The analysis of covariance results were statistically significant (n=134) with a 40% effect size (and a 74% effect size using multiple regression). The study demonstrated that cognitive learning strategies (accounting for gender and course level grade point average) can influence a student’s MFTB exam score. An analysis of covariance can be used to accurately measure student learning gain regardless of prior ability.

Keywords: cognitive learning strategy, exit exam, Major Field Test in Business

How can professors help large classes of undergraduate uni-versity students improve standardized exam scores? The problems in this case were that exam scores were low and it was difficult to measure the corresponding impact of faculty pedagogy (or other factors).

The reason for the obsession with standardized exams is that business school accreditation committees advocate inde-pendent student learning benchmarks (Accreditation Coun-cil for Business Schools and Programs, 2012; Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, 2012) such as the Major Field Test in Business (MFTB) from the Educational Testing Service (ETS, 2012). Furthermore, accreditation and standardized exam administration generally cost$27,000 to $100,000 per cycle depending on the situation (Marshall, 2007; Mason, Coleman, Steagall, Gallo, & Fabritius, 2011; Terry, Mills, Rosa, & Sollosy, 2009).

The main constraint I faced in this study was that the literature revealed that the key predictor of standardized exam grade was prior ability (Scholastic Aptitude Test [SAT] score), and sometimes other factors were significant such as gender, age or ethnic culture (Bagamery, Lasik, & Nixon, 2005; Bycio & Allen, 2007; Charter, 2003; Feeley, Williams, & Wise, 2005; Hamilton, Pritchard, Welsh, Potter, &

Sac-Correspondence should be addressed to Kenneth David Strang, State University of New York, Plattsburgh College, School of Business & Eco-nomics, Regional Higher Education Center, 640 Bay Road, Queensbury, NY 12804, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

cucci, 2002; Mirchandani, Lynch, & Hamilton, 2001; Picou, 2011; Santelices, & Wilson, 2010; Terry et al., 2009; Wallace & Clariana, 2005). SAT is a common metric used at univer-sities for admission and it is frequently cited in the literature. Ironically, ETS develops both the SAT and MFTB exams, so it is not surprising that there is some correlation between student scores.

Cognitive-learning strategies are well documented in the literature as being effective in terms of improving student outcomes (Schunk, 2004). These approaches are based on the cognitive learning theories developed by Piaget, Vygot-sky, Reuven, Feuerstein, and other educational psychology experts, although they were based on studies of children (Duncan, 1995). Earlier theories advocated that teaching self-regulation helped motivate students to improve study strate-gies (Piaget, 1970; Vygotsky, 1978) while newer approaches have applied game theory and career goals as the stimulus for motivation (Strang, 2010). Nonetheless, the basics of a cognitive learning strategy remain unchanged: develop an approach for solving problems without overloading mem-ory with complex information while also mastering subject matter for recall (Schunk, 2004).

I posited that the cognitive strategies introduced above could be used by a professor during pedagogy through role modeling, in a course preceding the MFTB. That is the unique pedagogy in this study because it is different that the theoret-ical application of teaching cognitive strategies to students. The research hypothesis was that modeling cognitive learn-ing strategies durlearn-ing pedagogy would help students increase

MFTB COGNITIVE LEARNING STRATEGY 143

their MFTB exam scores, if prior ability were accounted for as a covariate. However, a high degree of experimental control and statistical validity would be needed to provide credibility for any results and to allow this study to make a significant contribution to the literature.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Cognitive Learning Strategies for MFTB in Pedagogy

Cognitive learning strategies are whole-brain, holistic ap-proaches for solving problems. This is an effective type of pedagogy documented in the school-based educational psy-chology literature (Schunk, 2004), but it can also be effective for helping university students increase their standardized exam scores. Students must first be motivated to learn, which can be achieved by two steps. First, adult business students need to know the economic benefits of learning this approach (e.g., passing an exam to avoid wasting their tuition and time). Second, students have to be shown their existing approaches are faulty, otherwise they may tend to be overconfident and assume they can guess correct answers.

This second step can be implemented by having a mock exam, using a small but representative set of questions, strate-gically chosen by the professor to have 50% easy and 50% extremely difficult items; thus, it would likely result in most students barely making a pass. This encourages weaker stu-dents to develop a positivistic outlook, but demonstrates to the stronger students that practice is needed to maintain high grades. A link must be established between the standardized test score and a grade point average (GPA) outcome (not just a pass–fail but a percent or letter grade), so as to apply expectancy motivation theory (Schunk, 2004).

A cognitive strategy means to think about the approach to problems, by having the core models memorized, select-ing the correct model to apply to a problem, rearrangselect-ing the model to fit the variables in the problem, and working out an estimated answer. Standardized tests often do not allow sufficient time to calculate precise answers so the student must learn to estimate and to discriminate between correct versus impossible solutions, in multiple-choice answers. This may also require an interdisciplinary approach, because basic math models can be applied to solve a number of quantitative problems, namely the break-even technique. Speed of execu-tion for problem solving can be developed through practice, after the core basic models are mastered, and the student has practiced matching the model to a variety of problems.

The approach to prepare for a standardized university exam is important. Students often make the mistake of skip-ping the cognitive strategy practice by practicing questions in groups of similar concepts, which does not require iden-tifying the correct model (as the category is known before hand for many practice tests; e.g., accounting, time value of

money). A cognitive strategy means that the question must be quickly assessed for a match against a memorized model, to determine if a quantitative operation is necessary at all, as some questions are simply qualitative memory recall. When a quantitative calculation is needed, a basic model is recalled, the formula is rearranged as needed, the known variables are substituted into the terms using appropriate units, and then the unknown variable is solved for, using algebra to expedite the process (e.g., eliminating common terms, dropping zeros or changing decimal points in common between numerators and denominators). Modeling cognitive learning strategies requires the professor to perform the previous in front of students, and then having the students repeat the process. Once the students learn the methodology, practice at home can improve the overall speed.

Cognitive learning style strategies can be taught to stu-dents and these have improved academic outcomes on stan-dardized tests (Campbell & Mayer, 2009; Rovai, Wighting, Baker, & Grooms, 2009; Tsai & Huang, 2008). Brain re-search indicates that students are using cognitive learning styles when their synapses are more active. This is because they are looking for cross-disciplinary relationships to first find a method to apply to a problem, and then to find short cuts to find a solution (Nadolski, Kirschner, & Merri¨enboer, 2005; Zhang, 2005).

The most relevant study for our purposes was the large experiment of exam taking strategies by Picou (2011). He found that GPA was a significant predictor of standardized test scores, but gender and age were not (N=1,196). More so he determined that students performed better when the test items were ordered in a logical progression (linked) instead of a pure random pattern. His model captured 37% of the vari-ance on test score, with the following significant factors: GPA (β=12.924),t(1, 1,195)=3.89,p<.001, and subject link (β=1.913),=2.15,p<.001.

Based on this, an appropriate pedagogy would be to help students develop strategies for approaching quantita-tive questions that may have no pattern in their underlying theories. In other words, each quantitative question should be approached with a goal to quickly identify the problem solving theory–model, then to populate the formula and use short cuts for quickly obtaining the optimal solution.

Cognitive learning styles are ways that students organize knowledge to solve problems. In problem-based learning, hypotheticodeductive reasoning (or backward reasoning) is used (Smith, 2005). This means to use hypothesis testing to determine the falsity of assumptions. There is no time during the MFTB to do this. In generalized cognitive reason-ing, students practice selecting predefined models or theories by framing problems into categories of well-known subjects (e.g., a concept map each with its own keyword and problem solving methodology).

Sousa’s (2008) research on brain learning showed that ef-fective cognitive strategies for high stakes exams included: repeating complex methods, memorizing by linking new

information to existing schemas, applying heuristics by rec-ognizing patterns in problems to chose correct techniques, and actively repeating problem solving (Sousa, 2008; Strang, 2008, 2009, 2010). Students need to use memory dump func-tions with closed-book exams whereby they write down perti-nent keywords, models and formulas right at first before they become tired during the exam itself (Strang, 2011, 2012). In this way, students have models to choose from during the exam, especially when they get tired, or to solve those more complex bookmarked problems when they come back to them.

Predictors of MFTB Score for Experimental Control

Most empirical researchers concur that aptitude tests (SAT, ACT) are the strongest predictor of MFTB score, rather than the GPA from course work (Stivers & Phillips, 2009; Vitullo & Jones, 2010).

One of best-known benchmark studies was published by Black and Duhon (2003). They developed a regression model to predict MFTB score using (in order of greatest influence first): GPA from finance, accounting, and economics courses (β =5.51),t=7.37,p<.01; gender (β =4.91),t=4.94,

p<.01; SAT/ACT score (β=1.35),t=10.62,p<.01; and age (β=0.81),t=6.97,p<.01. Their model,F(296, 1)=

83.48,p<.01 (n=297) captured 53% of adjustedr2(Black

& Duhon, 2003).

Bycio and Allen (2007) measured the predictive ability of GPA and other factors on the MFTB. They found that business core GPA and other course GPA’s were significant predictors (N =132). Two interesting differences in their findings as compared to most other studies cited here were that gender did not predict MFTB score but student moti-vation was a significant factor. A recommendation in their study was to survey students several weeks or months prior to the exit exam in order to either motivate earnest students to increase studying or encourage unprepared students to postpone the test until next term.

Mason et al. (2011) applied ordinary least squares regres-sion on a large sample of 892 students over eight terms only to find that “clearly, ETSB outcomes are highly predictable; therefore, it is hard to conclude that the institution receives much if any incremental information from the ETS major field test in business” (p. 75). The factors were age, ethnic-ity, gender, matriculation term, final GPA, GPA in business courses only, GPA in nonbusiness courses, SAT (or equiva-lent ACT) score, declared major, transfer student status, and term of graduation.

Based on the previous, the following replication hypothe-ses were developed. These were designed to show how this study compares to existing research. The common predictors of MFTB will be replicated for statistical control. Because the status quo is that the common factors will predict MFTB

score, the alternative is that SAT effect can be reduced as a covariate of prior ability. The alternative hypotheses are the following:

Replication Hypothesis 1(H1): GPA would correlate highly with MFTB score.

Replication H2:Coursework grades would correlate highly with MFTB score.

Replication H3:Demographics (except gender) would not correlate highly with MFTB score.

Replication H4:Gender would correlate highly with MFTB score.

When considering the aforementioned literature review and assuming the experimental control (replication) hypothe-ses previous are be applied first, the final research hypothesis is the following:

H5:The treatment group using cognitive learning strategies during pedagogy would have higher MFTB scores when prior ability (SAT) is held constant as a covariate.

METHOD

I employed a theory-dependent positivist philosophy con-sisting of a deductive literature review to assist in identifying the common factors and then using the hypothesis testing approach (Gill, Johnson, & Clark, 2010) to determine the significance of the treatment condition and predictors on the dependent variable MFTB score. This means that I used the literature to identify important theories, concepts, or factors, and then tested them in a study. An inductive ideology is usually interpretive because the researcher observes or tests participants, and then tries to develop a new theory or cite supporting literature to describe the phenomena that have occurred.

Quantitative data techniques were selected because the study was designed to collect exam scores, which were ratio data types (Creswell, 2009). Descriptive statistics, validity tests, correlation, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and regression were applied to test the hypotheses at the 5% significance level.

Case Study Participants

The sampling method was non-random using natural intact convenience groups consisting of existing School of Business and Economics (SBE) students at the State University of New York (SUNY) Plattsburgh and Queensbury campuses located north of the state capital Albany (New York). The SBE had approximately 1,700 students during the study period. The sample consisted of 134 students across seven class sections in their last year of the bachelor of science in business ad-ministration degree program.

MFTB COGNITIVE LEARNING STRATEGY 145

Procedures

Purposive selection was used to identify senior students be-ing taught by the same faculty team in their last term before graduation. Students were excluded if they wrote the MFTB more than once. Students were selected for convenience be-fore the term commenced so that a modified syllabus could be constructed to reflect the pedagogy (instructional treatment and assessment).

The same professor taught both control and treatment groups. The same capstone undergraduate course was used—business strategy—but in different sections (due to mandatory faculty:student ratios). This was done to enforce high experiment control (to eliminate differences between instructors or course materials). The faculty team consisted of Kenneth David Strang as professor along with teaching as-sistants. For control purposes, the quasiexperiment was not discussed with the students. I randomly preselected the treat-ment and control groups before the term started. The syllabus was identical for all.

The treatment was applied to the test groups leaving the other sections in the business-as-usual control condition. For motivation, the MFTB exam was weighted as 20% in all courses for all sections. Both control and treatment groups were given the same MFTB preparation materials consisting of the directions and sample exams downloaded from the ETS (2012).

All students were given the same faculty-developed MFTB study materials at the beginning of the course, which consisted of PowerPoint slides of the main subject-related theories expected to be covered in the exit exam (e.g., ac-counting ratios, time value of money, marketing 4Ps). The faculty team, along with the chair of SUNY-SBE, gave a motivational briefing to all sections at the start of the term.

The pedagogy treatment consisted of the professor spend-ing four 1-hr class sessions focused on how to read work problems, select a common problem solving theory–model, and practice timed runs with a short MFTB exam. The treat-ment was given during the two weeks immediately preceding the exam. The control groups were given the same time dur-ing scheduled classes to study individually for the exam.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Validity

The key demographic factor and independent variable es-timates for the entire sample were (N = 134): M age =

24.1 years (SD =2.1 years); course GPA M =3.3 (SD=

0.6); female gender=53%; non-White or foreign ethnicity

=2%, SAT scoreM=1060.1 (SD=159.6); MFTB score

M =150.4 (SD=11.4). The MFTB national average was

M=152.4 (SD=13.2) at the time of writing (ETS, 2012). Descriptive statistics on all the factors and on the depen-dent variable (MFTB score) illustrated three important results

necessary to provide evidence of statistical and experimental validity:

• Demographic factors such as age, gender, course grades, and SAT and ACT scores were similar between the two groups: experimental control versus treatment pedagogy, based on descriptive statistics.

• Demographic factors age and culture were not related to MFTB, except for gender (explained subsequently).

• SAT scores were verified for reasonableness using the goodness-of-fit test, which revealed there was no signifi-cant difference between the sampling distribution of SAT scores as compared to what had been reported in recent Education Benchmarking Inc. surveys for accreditation purposes,χ2(18,N=217)=0.507,p=.999967.

Hypothesis Testing Analysis

Pearson product moment correlations of all factors identified during the literature review were tested with the MFTB score. As noted previously, demographic factors and course level scores did not reliably correlate with MFTB score either. The benchmark is that a coefficient beyond±0.3 is gener-ally considered significant but factors about±0.15 may be significant in social science studies (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

There was significant correlation between gender and SAT (+0.192) as well as with gender and MFTB score (+0.247), which clearly showed the advantage to men as the data were coded 1 =female, 2 =male. The correlations were very strong between GPA and SAT (0.429). MFTB correlated highly with the other variables, namely gender+0.247, SAT

+0.826, GPA+0.452, and pedagogy+0.364. Note that ped-agogy was a coded factor where 1 =experimental control group and 2=pedagogy treatment group.

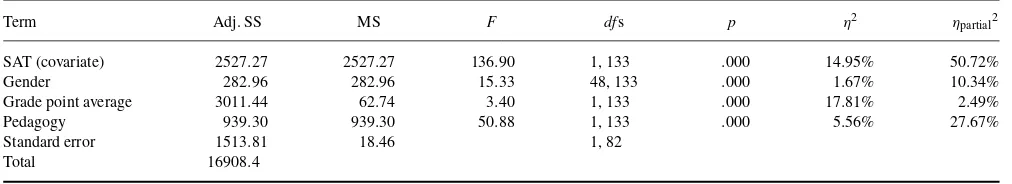

Hypothesized factor interactions on the dependent vari-able MFTB score were checked to prepare for ANCOVA. As anticipated, SAT×GPA was significant (p=.001). There-fore, SAT was appropriate as a covariate. The results of the ANCOVA model are shown in Table 1. eta squared effect size was calculated by dividing the adjusted sum of squares for the predictors including the covariate by the total (a conser-vative approach) while partial eta squared was estimated as

Ftest orFtest+maximumdf. All factors were statistically significant, which supported the research hypotheses.

As anticipated, SAT was the strongest factor in the AN-COVA model with a 15% eta squared effect size,F(1, 133)=

136.9,p =.000, and a large 51% partial eta squared mul-tivariate partial effect size. The next important factor was GPA (as hypothesized), an effect size 18%, F(1, 133) =

3.4, p =.000, with a small 3% partial multivariate effect. The pedagogy factor (treatment vs. business as usual) real-ized a 6% effect size,F(1, 133)=60.88, p =.000, along with a large 28% multivariate partial effect size. Gender

TABLE 1

Analysis of Covariance Linear Regression on Major Field Test in Business Score (N=134)

Term Adj. SS MS F dfs p η2 ηpartial2

SAT (covariate) 2527.27 2527.27 136.90 1, 133 .000 14.95% 50.72%

Gender 282.96 282.96 15.33 48, 133 .000 1.67% 10.34%

Grade point average 3011.44 62.74 3.40 1, 133 .000 17.81% 2.49%

Pedagogy 939.30 939.30 50.88 1, 133 .000 5.56% 27.67%

Standard error 1513.81 18.46 1, 82

Total 16908.4

Note: Adjustedr2(133)=.40. All terms were statistically significant atp<.05. SS=16908.5; MS=3830.73.

demonstrated a small 2% effect, F(1, 133) = 15.33, p = .000, with a moderate 10% partial multivariate effect.

The ANCOVA model using these four factors (with SAT as a covariate) captured 40% of the true variation in MFTB score (using the more conservative adjusted r2

estimate). According to benchmarks, this adjustedr2

of 40% was con-sidered a large ANCOVA effect size (Cohen, Cohen, West & Aiken, 2003). The adjusted means were treatment pedagogy using cognitive learning strategiesM =155 (n =79) and experimental control using business-as-usual approachM=

149.38 (n=55). Therefore, it is clear that the cognitive learn-ing strategies significantly improved MFTB score, when SAT was held constant to account for prior ability. Based on this there was adequate support to accept all hypotheses.

DISCUSSION

Modeling Cognitive Learning Strategy Reflections

The cognitive learning strategy pedagogy was very effective when the professor modeled the approach in front and with the students, rather than merely explaining how the technique theoretically worked. The pedagogy modeling started after the professor first scheduled a timed experiment using an example MFTB exam, allowing 40 min for 40 questions. This was done before modeling the cognitive learning strategies in order that they would realize the need for having a quick problem-solving methodology. In addition, students would build awareness of the two different categories of MFTB questions: qualitative subject matter requiring memorization and quantitative reasoning type problems.

There are nine subject matter disciplines on the MFTB: accounting, economics, management, quantitative business analysis, finance, marketing, legal social environment, in-formation systems and international issues (ETS, 2012). Of these, accounting, quantitative business analysis and finance are predominately quantitative reasoning categories. Each of these is believed to have at least 12 commonly used theories or models with standard equations. Therefore there are 12×

3=36 standard equations to know for framing quantitative reasoning problems (not including equation reformatting).

Quantitative reasoning problems on the MFTB will gener-ally take more than 1 min each so time must be made available by using rapid memory recall to solve the qualitative items. Heuristics can be used on some problems such as those with obvious answers as divide by zero has no solution.

The professor then modeled the cognitive strategy for framing and solving each of the most common quantitative subjects. Note that the professor did not explain the strategy but instead applied (modeled) it. This works by identifying keywords in the problem, which point to the subdiscipline (e.g., marketing, operations research), and the specific gen-eral model or theory (e.g., sales margin, break even analysis, waiting line queues). Each theory has a standard equation where the terms can be rearranged to suit the data available in the problem, position the dependant variable on the left side of the sign, and solve it.

Table 2 lists a break even problem from the MFTB prac-tice exam (questions 4 and 5; ETS, 2012), consisting of an introduction and two questions. Theoretically 2 min should be spent solving these.

The next step of the cognitive modeling strategy was to model each technique, which in this case was break even. The professor demonstrated how to identify operations re-search keywords such asmanufactureandproduction. Next the frame of reference type is a break-even problem (BEP) as there are fixed costs, direct variable selling prices, direct variable costs (e.g., labor and raw materials). The first ques-tion of “How many pillows. . .” refers to a whole quantity (integer units). Students were shown to quickly write the for-mula down, on a blank self-created forfor-mula page (permitted for the test), the first time it is encountered as shown sub-sequently (but using abbreviations). Every time the formula was needed the professor looked at the formula page. The professor demonstrated this on all the sample exam prob-lems.

The standard break even formula is:

Z (BEP)=Fixed Costs/(Variable Selling Price

−Variable Cost). (1)

The professor then wrote the formula when needed with terms rearranged to place the unknown variable on the left side of the sign, and the known values substituted. In this case

MFTB COGNITIVE LEARNING STRATEGY 147

TABLE 2

Example Major Field Test in Business Exam Question

Dreamland Pillow Company sells the “Old Softy” model for$20 each. One pillow requires two pounds of raw material and one hour of direct labor to manufacture. Raw material costs$3 per pound and direct production labor is paid$4 per hour. Fixed supervisory costs are$2,000 per month and Dreamland rents its factory on a five-year lease for$4,000 per month. All costs are considered costs of production.

4. How many pillows must Dreamland produce and sell each month to earn a monthly gross profit of$1,000?

5. Another firm has offered to produce “Old Softy” pillows and sell them to Dreamland for$12 each. Dreamland cannot avoid the factory lease payments, but can avoid all labor costs if it does not produce these pillows. Under these conditions, how many “Old Softy” pillows must Dreamland sell to earn monthly gross profits of$1,000?

the professor underlined key process words and circled all relevant data constants in the problem regardless of whether they were written as numbers or spelled out (e.g., five and 5 would be potentially considered data). The gross profit is fixed and can be treated as a numerator in the formula (added to fixed costs). It is clear from the process words that quantity to make per month is needed. Therefore the solution to question 4 is the following:

Z(BEP)=Profit+FC/SP−VC : (1000+2000)

+(4000)/(20−(3∗2)+(4∗1))=700.(2)

For question 5, the data was circled, and process words underlined. It is clear from the process words that quantity per month to produce is again needed. Profit is unchanged but fixed supervisory costs are eliminated, and variable costs are now $12 due to outsourcing. Therefore the solution to question 5 is the following:

Z(BEP)=Profit+FC/SP

−VC : (1000+4000)/(20−12)=625. (3)

Implications and Recommendations

This study went beyond replicating earlier models. A new model was developed that demonstrated that pedagogy, specifically cognitive learning strategies, could help students improve their MFTB scores. Furthermore, this study illus-trated how to use ANCOVA to measure learning gain from standardized exams such as the MFTB, which can provide evidence of the subject matter knowledge obtained from a de-gree program. This type of benchmark is needed for business school accreditation.

From a teaching practice standpoint, the important points were that students needed to be motivated to use cognitive learning strategies and the professor had to show how to do this in front of the students (model it). It was essential for students to first learn how to memorize core business models, and then identify how to match those models with complex word problems. Then students had to learn how to use algebra to rearrange factors and variables in the core models to solve slightly different but related problems, which reduced the cognitive load of having to memory variations

of the same basic theories. Students also learned how to use algebra to quickly estimate likely answers by simplifying terms in a model after the known values were substituted into the variables. Speed of problem solving was obtained through practice after cognitive learning strategies were mastered. The results indicate that both weak and strong students can apply cognitive learning strategies to improve their scores.

From an institutional perspective, if an accredited uni-versity wishes to use an independent standardized exam to demonstrate the ability of their faculty to teach and the abil-ity of their students to learn, then why not use the ANCOVA model technique demonstrated in this study which will more accurately report learning gain from course work? This will appease all stakeholders, those that want independent mea-sures, those that want to see money expended on independent measures, and the faculty and students who both want more accurate indicators of what was actually learned during the degree program.

The key limitations for generalizing this study were the small sample size of 134 undergraduate business students and the university context where the study took place (be-cause the experiment was conducted within the classroom not online). Nonetheless the author observed that other stu-dents beyond the current sample who followed this cogni-tive learning strategy approach consistently scored higher on standardized exams as compared with the other campuses and the national mean. Finally, as reviewers pointed out, this is not a new educational psychology learning theory, but it can serve as encouragement that this model can be applied in accredited business schools to appease the divergent views of including independent external benchmarking into the cur-riculum while also accounting for true learning based on the collaborative hard work of students and their dedicated faculty during the program.

REFERENCES

Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs. (2012). Accredi-tation Council for Business Schools and Programs (ACBSP). Kansas City, KS: Author.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2012).Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). Tampa, FL: Author. Bagamery, B. D., Lasik, J. J., & Nixon, D. R. (2005). Determinants of success on the ETS business major field exam for students in an undergraduate

multisite regional university business program.Journal of Education for Business,81, 55–63.

Black, H. T., & Duhon, D. L. (2003). Evaluating and improving student achievement in business programs: The effective use of standardized assessment tests.Journal of Education for Business,79, 90–98. Bycio, P., & Allen, J. S. (2007). Factors associated with performance on the

educational testing service (ETS) major field achievement test in business (MFAT-B).Journal of Education for Business,82, 196–201.

Campbell, J., & Mayer, R. E. (2009). Questioning as an instructional method: Does it affect learning from lectures?Applied Cognitive Psychology,23, 747–759.

Charter, R. A. (2003). A breakdown of reliability coefficients by test type and reliability method, and the clinical implications of low reliability.The Journal of General Psychology,130, 290–304.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003).Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences.Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches.New York, NY: Sage.

Duncan, R. M. (1995). Piaget and Vygotsky revisited: Dialogue or assimi-lation?Developmental Review,15, 458–472.

Educational Testing Service (ETS). (2012).Information and validity about the Management Field Test in Business. Princeton, NJ: Author. Feeley, T. H., Williams, V. M., & Wise, T. J. (2005). Testing the predictive

validity of the GRE exam on communication graduate student success: A case study at University at Buffalo.Communication Quarterly,53, 229–245.

Gill, J., Johnson, P., & Clark, M. (2010).Research methods for managers. London, England: Sage.

Hamilton, D. M., Pritchard, R. E., Welsh, C. N., Potter, G. C., & Saccucci, M. S. (2002). The effects of using in-class focus groups on student course evaluations.Journal of Education for Business,77, 329–333.

Marshall, L. L. (2007). Measuring assurance of learning at the degree pro-gram and academic major levels.Journal of Education for Business,83, 101–109.

Mason, P. M., Coleman, B. J., Steagall, J. W., Gallo, A. A., & Fabritius, M. M. (2011). The use of the ETS Major Field Test for assurance of business content learning: Assurance of waste?Journal of Education for Business, 86, 71–77.

Mirchandani, D., Lynch, R., & Hamilton, D. (2001). Using the ETS Major Field Test in Business: Implications for assessment.Journal of Education for Business,77, 51–56.

Nadolski, R. J., Kirschner, P. A., & van Merri¨enboer, J. J. (2005). Optimizing the number of steps in learning tasks for complex skills.British Journal of Educational Psychology,75, 223–237.

Piaget, J. (1970). InCarmichael’s manual of child psychology(vol. 1). New York, NY: Wiley.

Picou, A. (2011). Does gender, GPA or age influence test performance in the introductory finance class? A study using linked questions.Review of Business Research,11, 118–126.

Rovai, A. P., Wighting, M. J., Baker, J. D., & Grooms, L. D. (2009). Devel-opment of an instrument to measure perceived cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning in traditional and virtual classroom higher educa-tion settings.Internet and Higher Education,12, 7–13.

Santelices, M. V., & Wilson, M. (2010). Unfair treatment? The case of freedle, the SAT, and the standardization approach to differen-tial item functioning. Harvard Educational Review, 80, 106–133, 141–142.

Schunk, D. H. (2004).Learning theories: An educational perspective.Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Smith, R. O. (2005). Working with difference in online collaborative groups. Adult Education Quarterly,55, 182–199.

Sousa, D. A. (2008).How the brain learns mathematics.Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press/Sage.

Stivers, B., & Phillips, J. (2009). Assessment of student learning: A fast-track experience.Journal of Education for Business,84, 258–262. Strang, K. D. (2008). Quantitative online student profiling to

fore-cast academic outcome from learning styles using dendrogram deci-sion models.Multicultural Education & Technology Journal,2, 215– 244.

Strang, K. D. (2009). How multicultural learning approach impacts grade for international university students in a business course.Asian English Foreign Language Journal Quarterly,11, 271–292.

Strang, K. D. (2010).Effectively teach professionals online: Explaining and testing educational psychology theories.Saarbr¨ucken, Germany: VDM. Strang, K. D. (2011). How can discussion questions be effective in online

MBA courses?International Journal of Information & Learning Tech-nology in Campus-Wide Information Systems,28, 80–92.

Strang, K. D. (2012). Skype synchronous interaction effectiveness in a quan-titative management science course.Decision Sciences Journal of Inno-vative Education,10, 3–23.

Terry, N., Mills, L., Rosa, D., & Sollosy, M. (2009). Do online students make the grade on the business major field ETS exam?’Academy of Educational Leadership Journal,13, 109–118.

Tsai, M.-T., & Huang, Y.-C. (2008). Exploratory learning and new product performance: The moderating role of cognitive skills and environmental uncertainty.The Journal of High Technology Management Research,19, 83–93.

Vitullo, E., & Jones, E. A. (2010). An exploratory investigation of the as-sessment practices of selected association to advance collegiate schools of business-accredited business programs and linkages with general edu-cation outcomes.Journal of General Education,59, 85–104.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978).Mind in society.Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-sity Press.

Wallace, P., & Clariana, R. B. (2005). Gender differences in computer-administered versus paper-based tests.International Journal of Instruc-tional Media,32, 171–179.

Zhang, L.-F. (2005). Predicting cognitive development, intellectual styles, and personality traits from self-rated abilities.Learning and Individual Differences,1, 67–88.