ITS

E

FFECTS ON

F

REE

-R

IDING IN

N

EW

Z

EALAND

DAVIDWILKINSON,* RAYMONDHARBRIDGE* ANDPATWALSH**

F

ree-riding occurs where an employee gains a benefit without joining the union that negotiated that benefit. New Zealand unions endured a decade of high levels of free-riding under the Employment Contracts Act. This paper establishes that, in New Zealand, collective bargaining coverage has a positive relationship with free-riding whereas union membership levels have a negative relationship. Free-free-riding in New Zealand has fallen to pre-1991 levels with the re-regulation of employment relations, indicating environment too may be an important factor. These findings have implications for Australia where unions have sought to coerce membership through applying a fee for service to non-members, while the Commonwealth Government recently passed legislation preventing such coercion.INTRODUCTION

It’s like signing a birthday card and not contributing for the present—they should either pay the fee or not receive the negotiated benefit. (Health Services Union National Assistant Secretary Jeff Jackson quoted in The Age, 16 February 2001, p. 6.)

Free-riding, in an employment relations context, is the situation where an employee attains the benefits of a collectively negotiated agreement specifying wages and other conditions of employment, without contributing to the cost of the negotiations and the servicing of the agreement by joining the relevant union. New Zealand’s decade of ‘employment contracting’ in the 1990s led to a spec-tacular collapse in union membership with unions losing over 50 per cent of their members in just the first three years of labour market deregulation. Union density collapsed from around 44 per cent to around 17 per cent over the decade (May et al. 2001). That collapse has been attributed to the legislative failure to externally legitimate New Zealand’s unions (Harbridge & Honeybone 1996). Traditionally, in many occupations, unionists were ‘reluctant conscripts’ (Bramble & Heal 1997, p. 133) and the abolition of external legitimisation led to serious union decline.

Elsewhere we have explored the impact of the lack of external legitimisation specifically on free-riding rates. Free-riding grew from around 16 per cent in 1989/90 under the system of industrial conciliation and arbitration, to 27 per cent in 1998/99 under the system of employment contracting (Harbridge & Wilkinson 2001). We concluded that, in the absence of a legislative system that allowed for coercion or ‘cheap-riding’, unions in industries with high labour turnover rates had limited effective responses to free-riding. Restricting the collective agreement to unionists only allowed the undermining of the agreement with the formation of a (lower) tier agreement. Coupled with the traditional inter-national explanations of unions decline,1 New Zealand unions have suffered

as changes to international trade and increased import competition led to an inability to recruit and retain members where imported goods accounted for a large and/or increasing share of domestic consumption (see Blumenfeld et al. 1999a, 1999b; Crawford & Walsh 1999). In addition to this ‘regular’ union decline, New Zealand’s unions have experienced an important level of growth in free-riding, with crippling levels of free-riding in the high labour turnover, smaller employer, service based industries, since the introduction of the Employment Contracts Act. Price and Bain (1989) note that periods of institutional development, such as that which occurred during the 1990s in New Zealand, are marked by:

Acute socio-political changes, which emerge from, and reflect the pre-existing power resources available to the three main parties involved—State, employers and workers, and the outcome of which is the interplay of these power resources . . . The institutional and attitudinal arrangements which emerge out of these periods of accelerated change impose key constraints on the subsequent development of union organisation and collective bargaining; a paradigm shift (1989, p. 105).

A paradigm shift creates new patterns in the context of industrial relations, primarily changes in labour laws and the powers and roles of regulatory agencies, employer policies towards unionisation and collective bargaining, collective bargaining structures, and union structures, political activities and ideology. Once the new context is in place, the parties enter a period of insti-tutional consolidation; they undergo changes of degrees rather than changes of type until the next paradigm shift occurs (Chaison & Rose 1991). The election of a Labour Coalition Government in late 1999 heralded just such a paradigm shift. The new Government repealed the Employment Contracts Act 1991 and replacement it with the Employment Relations Act 2000—a law designed to bring about a ‘fairer’ system of bargaining in New Zealand. Whether this new paradigm has effectively dealt with free-riding is the focus of this paper.

METHOD

from the Statistics New Zealand series, Household Labour Force Survey. The data is disaggregated at two-digit industry level. It is not possible to sensibly calculate collective bargaining coverage at two digit industry level for 1991 as some 180 000 employees were then covered by multi-employer awards negotiated on an occupational (rather than industry) basis. Data for two major industry categories have been omitted in the results presented. Data for the largely un-unionised agricultural sector is generally omitted in employment relations research as it distorts the results; the data for the mining sector has been excluded as the numbers involved are small and probably unreliable. In some categories we present the data at (major industry) one digit level. We present the raw data and then regress the data to explore explanations as to the trends.

RE-REGULATION AND FREE-RIDING

The post-entry closed shop system of essentially compulsory union membership existed in New Zealand in one form or another, and with brief periods of voluntary unionism, from 1936 until 1991. Workers covered by an award or collective agreement were required by the terms of that agreement to join the union that had negotiated it. Free-riding did exist, but only through non-enforcement of the terms of the agreement. By 1991 we estimated that free-riding ran at around 16 per cent of collective bargaining coverage. The Employment Contracts Act outlawed any form of compulsion over union membership, and enabled a variety of explicit and implicit forms of free-riding to take place. Employers generally applied the union negotiated collective agreement to all employees. The transactional costs of negotiating multiple individual employment contracts encouraged employers simply to apply the collective. Employees frequently found little incentive to join the union in these circumstances. They got the benefit of the collective agreement without needing to join the union and accordingly free-riding rose to some 27 per cent by the end of the 1990s (Harbridge & Wilkinson 2001). Oxenbridge (1998) examined free-riding in two unions positioned in the low wage, service orien-tated industries. She found that officials of the union, along with members and delegates, used ‘peer pressure’, ‘guilt’ and ‘humiliation’ appeals to persuade employees to join, while other officials ‘sold’ membership on the basis of contract enforcement and benefits. Neither method was reported as particularly successful. One of the unions studied reported that some anti-union employers were ‘ . . . using HRM techniques . . . to persuade workers that since non-members received the same wages as non-members there was little to gain from union membership’ (Oxenbridge 1998, p. 307).

The Employment Relations Act 2000 offers a different philosophy to the regulation of industrial relations, clearly promoting collective bargaining, and promoting the observance of ILO Conventions 87 on Freedom of Association and 98 on the Right to Organise and Bargaining Collectively. Unions are re-legitimised through a process of registration. The objects of the new Act are, with respect to the recognition and operation of unions:

• to provide for the registration of unions that are accountable to their members;

• to confer on registered unions the right to represent their members in collective bargaining; and

• to provide representatives of registered unions with reasonable access to workplaces for purposes related to employment and union business.

Towards the end of the Employment Contracts Act regime there had been approximately 80–85 active unions. A further 80 unions have registered under the new legislation. Registration is a precursor to bargaining and accordingly is of interest. Registered unions have the sole right to undertake collective bargaining. Collective bargaining is to be undertaken in a duty of good faith. The obligations of the duty of good faith in the New Zealand context are some-what onerous and are discussed in detail, along with the general bargaining provisions, in Walsh and Harbridge (2001).

The Employment Relations Act deals with the issue of free-riding ineffectively. The Employment Contracts Act allowed new employees to join the collective employment contract, but it was not mandatory and many unions were unable to write provisions into their contracts that gave new employees the right to the existing contract. By 1999/2000, around 37 per cent of employees covered by collective employment contracts were on contracts that did not provide for automatic extension of the contract to new employees (Harbridge & Crawford 2000). The Employment Relations Act gives force to the principle of ‘join the union, join the contract’. This means that a new employee will automatically be bound by the terms of any applicable collective agreement where he or she is a member of the negotiating union. In other cases, the Act provides that where there is an applicable collective agreement in place, new employees will be employed on an individual employment agreement containing the relevant terms and conditions of the collective. For the first 30 days of employment any variations to these terms cannot be inconsistent with, that is no less favourable to the employee than, those contained in the collective. Only at the expiry of this 30 day period, and providing the employee does not subsequently become a union member, can the new employee’s terms and conditions be varied without

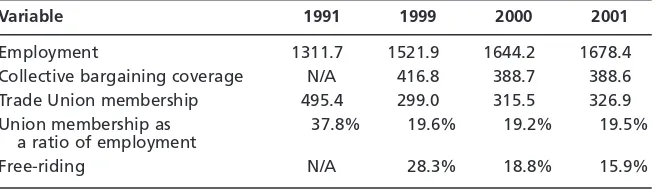

Table 1 Employment relations data for selected industries, 1991–2001

Variable 1991 1999 2000 2001

Employment 1311.70 1521.90 1644.20 1678.40 Collective bargaining coverage N/A 416.8 388.7 388.6 Trade Union membership 495.4 299.0 315.5 326.9 Union membership as 37.8% 19.6% 19.2% 19.5%

a ratio of employment

Free-riding N/A 28.3% 18.8% 15.9%

regard to the terms of the collective agreement. In effect, the Act provides for the automatic extension of the terms and conditions of a collective agreement to all new employees. Accordingly, it seems likely that while the intention of the legislation was to encourage employees to join the union to receive the benefits of the collective agreement, there is no real incentive to do so as the employer cannot unilaterally apply an inconsistent agreement. The ‘new employee’ and ‘coverage’ clause issue has proved difficult to manage in reality. A good number of new agreements entered into appear to have extended the coverage of the agreement to all employees, regardless of the legal position which requires employees to be union members before coverage can be assumed. Free-riding had the potential to remain a significant problem.

The data in Table 1 summarise general trends across the selected industries. The Employment Relations Act took effect from October 2000. The data show that:

• employment grew during the period of the Employment Contracts Act and under the Employment Relations Act;

• collective bargaining coverage collapsed during the period of the Employment Contracts Act and is largely unchanged under the Employment Relations Act; • trade union membership collapsed during the period of the Employment Contracts Act but has increased slightly under the Employment Relations Act;

• trade union membership as a ratio of employment decreased during the period of the Employment Contracts Act and has increased slightly under the Employment Relations Act; and

• free-riding increased under the Employment Contracts Act but has decreased back to 1990 levels under the Employment Relations Act. Notably, free-riding has decreased by more than 40 per cent since 1999.

We have explored free-riding in detail over a three year period from 1999 to 2001. During this period three distinct bargaining environments existed. Bargaining in 1999 was conducted under the Employment Contracts legislation. Bargaining in 2000 was conducted in a transitional climate—with a newly elected Labour/Alliance Coalition committed to the repeal of the Employment Contracts Act and its replacement by ‘fairer’ legislation; this new legislation took effect from

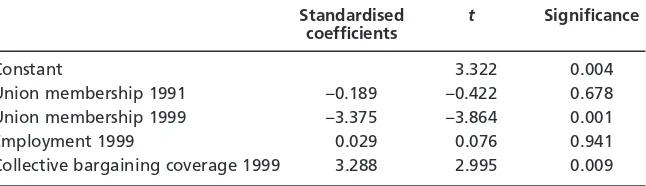

Table 2 Determinants of free-riding, 1999

Standardised t Significance

coefficients

Constant 3.322 0.004

Union membership 1991 –0.189 –0.422 0.678 Union membership 1999 –3.375 –3.864 0.001 Employment 1999 0.029 0.076 0.941 Collective bargaining coverage 1999 3.288 2.995 0.009

October 2000. Bargaining in 2001 was conducted under the Employment Relations Act, a re-regulation of the bargaining rules.

In an attempt to explain some of the factors determining free-riding, several regression models were run. The dependant variable was free-riding by industry in three years: 1999, 2000 and 2001. The independent variables were union membership by industry in 1991, 1999, 2000 and 2001; employment by industry in 1999, 2000 and 2001; and collective bargaining coverage by industry for 1999, 2000 and 2001.

The hypothesis underlying each model was similar: that free-riding was inversely related to the level of union membership by industry, positively related to the level of employment in each industry and, positively related to the level of collective bargaining in each industry. The first part of the regression (a negative relationship between free-riding and union membership) would appear self-evident. However, by itself, it may be misleading in that union membership may be low as a consequence of low employment in an industry sector. This leads to the second component of the regression analysis: a positive relationship between free-riding and employment in each industry sector. If industry employment is high, but union membership is low, it implies, ceteris paribus, that free riding must be higher. Finally, given that a primary function of unions is to be successful in wage bargaining, the existence of higher levels of collective bargaining leads to an incentive for employees to free-ride.

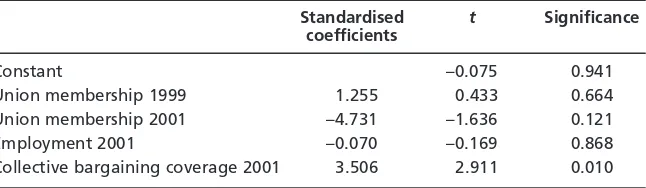

Table 4 Determinants of free-riding, 2001

Standardised t Significance

coefficients

Constant –0.075 0.941

Union membership 1999 1.255 0.433 0.664 Union membership 2001 –4.731 –1.636 0.121 Employment 2001 –0.070 –0.169 0.868 Collective bargaining coverage 2001 3.506 2.911 0.010

Dependant variable: Free-riding in 2001. Adjusted R2: 0.427

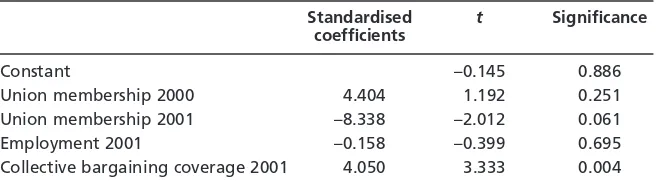

Table 3 Determinants of free-riding, 2000

Standardised t Significance

coefficients

Constant 0.237 0.816

Union membership 1999 –0.741 –0.227 0.823 Union membership 2000 –3.178 –1.091 0.292 Employment 2000 –0.030 –0.086 0.932 Collective bargaining coverage 2000 3.882 3.870 0.001

The results of the regression analyses are shown in Tables 2 to 5. The tables indicate that only one independent variable is consistently significant in each case, this being collective bargaining. In each case, collective bargaining has a positive relationship with free-riding—that is, the higher the level of collective bargaining, the higher the level of free-riding. As noted earlier, given that collective bargaining is a central aim of unions, these results indicate that the more successful a union is in undertaking such activities, the more it encourages free-riding.

The second hypothesis—that there is a positive relationship between free-riding and industry employment—is not supported. Table 2, for the year 1999, does show a small, positive relationship. This is not significant however. The remaining Tables show small but negative relationships, again not significant.

The union membership variables show mixed results. Each model contains two measures for union membership. One for the year in which free-riding is measured and one for an earlier period (for example union membership in 2000, union membership in 2001 and free-riding in 2001—Table 5). This variable was incorporated into the models in order to see whether the size of a union in an earlier period impacted on the free-riding issue. The results were mixed.

Union membership for the year in which free riding is measured shows a negative relationship with free-riding in all models—that is, the higher the level of union membership, the lower the level of free-riding. However, this variable is only significant in 1999 (Table 2) and in one of the models for 2001 (Table 5). However, the variable showing union membership for an earlier period showed a negative relationship in the two earlier models (Tables 2 and 3) and a positive relationship in the later two models (Tables 4 and 5). This variable was not signifi-cant in any model.

The models for 1999 and 2000 (Tables 2 and 3) indicate that they are good overall estimators of free-riding, with adjusted R2 of 0.639 and 0.708,

respectively. The same models for 2001 (Tables 4 and 5) do not perform as well, the adjusted R2 declining to 0.427 and 0.468, respectively, even though

collective bargaining remains highly significant. Since the models are identical in terms of independent variables used (other than the years involved), this is suggestive that other factors have changed.

Table 5 Determinants of free-riding, 2001

Standardised t Significance

coefficients

Constant –0.145 0.886

Union membership 2000 4.404 1.192 0.251 Union membership 2001 –8.338 –2.012 0.061 Employment 2001 –0.158 –0.399 0.695 Collective bargaining coverage 2001 4.050 3.333 0.004

DISCUSSION

Free-riding is an issue for Australian and New Zealand unions. Users are not paying, well not allusers are paying. Coercion is no longer an option for New Zealand unions. Apart from being illegal, the general climate (both political and public opinion) would not permit it. Australian unions have recently attempted the coercion path, applying the agency shop variation which is widely used throughout the USA.2 In February 2001, the Australian Industrial Relations

Commission ruled that a $500 service fee for non-union workers introduced by the Electrical Trades Union was legally valid. This was adoption in practice of policy enacted at the June 2000 Australian Council of Trade Unions Congress. The response from the ‘furious’ Workplace Relations Minister, Tony Abbott, was swift and on two fronts. First, and as an employer, the Government, through the Department of Workplace Relations, wrote to public service agency and department heads advising them not to include service fees in workplace agree-ments for Australia’s 100 000 public servants. The spokeswoman for the Minister was quoted as saying: ‘It’s just an advice, but we think it will be fairly persuasive’ (reported in The Age, 21 February 2001, p. 4). Second, the Government intro-duced, on 23 May, the Workplace Relations Amendment (Prohibition of Compulsory Union Fees) Bill 2001. The purpose of the Bill was simple: to prohibit the inclusion in enterprise agreements of a clause allowing industrial organisations to charge a fee for service in respect of enterprise bargaining negotiations.

After several rejections by the Senate, followed by a compromise by the Government, the Bill was finally passed by Senate on 26 March 2003, coming into effect on 9 May 2003. The compromise agreed to by the Government means that new legislation opens the door for bargaining fees if the employees agree to pay them. This was a backdown by the Government which had rejected the concept of permissible bargaining fees the previous August.

Just prior to this (January 2003) a Full Bench of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission, hearing an appeal on earlier decisions, ruled that union bargaining fees were not matters that pertain to the employment relationship between employers and employees, and therefore were not industrial matters that could be included in a certified agreement. The situation is somewhat confused however as the Industrial Relations Commissions of both New South Wales (December 2002) and South Australia (June 2003) have ruled that bargaining fees can be charged.

suffer the fate of facing higher levels of free-riding. Where they are successful in getting high levels of union membership within an industry, they experience lower levels of free-riding. Quite a conundrum really.

While New Zealand unions may well be pleased with the recent fall in free-riding levels, they would be less pleased with the overall results delivered by the Employment Relations Act. Collective bargaining coverage levels remain at approximately the same levels they have been at since about 1993—around 400 000 employees. While union decline has ended and union growth has emerged, that growth has been low. However, union density has remained at 1999 levels. Growth in the workforce is not being matched by a growth in either union density or collective bargaining coverage.

A fall in free-riding has occurred despite the apparent ineffectiveness of the Act in dealing legislatively with the issue. In our analysis of the data, we proposed that comparatively low adjusted R2scores were suggestive of other

factors being responsible in the fall in free-riding since the implementation of the Employment Relations Act. Such factors are not captured by the data gathered. One such factor could well be climate or environment. The Government in implementing the Employment Relations Act made much of ‘fairness’ in bargaining. We have previously reported (Harbridge et al. 2002) that interviews with the Secretaries of four large New Zealand unions had indi-cated that non-members were now reporting that ‘seeing as it is now legal to join . . .’ Union membership had not been illegal under the Employment Contracts Act. However, the harsh environment of that Act, coupled with employer ascendancy during the early years of the Act, may well have led employees to believe it either was illegal, or was certainly not the correct thing to do. The ‘fair’ environment of the new legislation could well be the important other factor influencing the fall in free-riding. Climate or environment in such circumstances is difficult, if not impossible, to quantify in the way we have quantified other factors. What we do know for certain is that, at industry level, unions that attain high levels of collective bargaining penetration experience high levels of free-riding. This result, however, leads to a basic contradiction for unions.

Earlier work by on the determinants of union growth (Harbridge et al. 2002) showed that union growth is a function of collective bargaining, but so is free riding. The more successful is the level of collective bargaining, the greater is the ability to retain or attract new members, but the greater is the incentive, ceteris paribus, for free riding to occur. The results reported here would further support that initial finding.

In the absence of legislative support, free riding is likely to remain a problem for unions in both Australia and New Zealand.

ENDNOTES

1. Union decline is primarily attributed to macro-economic or business cycle conditions and sharp rises in unemployment (Bain & Price 1983; Tyler 1986); and the shift from manufacturing to services, contingent employment and changes in firm size (Troy 1990; Peetz 1998). 2. See Orr (2001) for a comprehensive review of the agency shop in the USA, and for discussion

REFERENCES

Bain G, Price R (1983) Union Growth: Dimension, Determinants and Density. In: Bain G, ed.,

Industrial Relations in Britain, pp. 3–33. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Blumenfeld S, Crawford A, Walsh P (1999a) Trading Up or Trading In? Manufacturing Wages in a Globalised Economy: The Case of New Zealand. Paper presented to Globalisation and Labour Regulation Conference, 13–14 May, University of Newcastle.

Blumenfeld S, Crawford A, Walsh P (1999b) Globalisation, Trade and Unionisation in an Open Economy: The Case of New Zealand. In: Tipples R, Shrewsberry H, eds, Global Trends and Local Issues, Proceedings of the 7th Annual International Employment Relations Association (IERA) Conference, July, Christchurch, New Zealand, Vol. 1, pp. 63–78.

Bramble T, Heal, S (1997) Trade Unions, In: Rudd C, Roper B, eds, The Political Economy of New Zealand, pp. 119–140. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

Chaison GN, Rose J (1991) The Macrodeterminants of Union Growth and Decline. In: Strauss G, Gallagher D, Fiorito J, eds, The State of the Unions. Madison, Wisconsin: Industrial Relations Research Association Series.

Crawford A, Walsh P (1999) No Longer Creatures of the State: The Response of New Zealand’s Trade Unions to the Employment Contracts Act. Paper presented to The Future of Trade Unions Network Conference, University of Cardiff, Wales, 19–20 November.

Harbridge R, Crawford A (2000) Employment Contracts: Bargaining Trends and Employment Law Update 1999/2000.Wellington: Industrial Relations Centre, Victoria University of Wellington. Harbridge R, Honeybone A (1996) External legitimacy of unions: trends in New Zealand.Journal

of Labor ResearchXVII (3), 425–444.

Harbridge R, Thickett G, Kiely P (2001) Employment Contracts: Bargaining Trends and Employment Law Update 2000/2001. Wellington: Industrial Relations Centre, Victoria University of Wellington.

Harbridge R, Walsh P, Wilkinson D (2002) Re-regulation and union decline in New Zealand: likely effects. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations27 (1), 65–78.

Harbridge R, Wilkinson D (2001) Free-riding: trends in collective bargaining coverage and union membership levels in New Zealand.Labor Studies Journal26 (3), 53–74.

May R, Walsh P, Thickett G, Harbridge R (2001) Unions and union membership in New Zealand: annual review for 2000. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations26(3), 317–328.

Orr G (2001) Agency shops in Australia? compulsory bargaining fees, union (in)security and the rights of free-riders. Australian Journal of Labour Law14 (1), 1–35.

Oxenbridge S (1998) Running to Stand Still: New Zealand Service Sector Trade Union Responses to the Employment Contracts Act 1991. Ph. D thesis, Victoria University of Wellington.

Peetz D (1998) Unions in a Contrary World: The Future of the Australian Trade Union Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Price R, Bain G (1989) The Comparative Analysis of Union Growth. In: Recent Trends in Industrial Relations and Theory, Proceedings of the 8th Annual Congress of International Industrial Relations Association, Brussels, pp. 99–110.

Troy L (1990) Is the U.S. unique in the decline of private sector unionism? Journal of Labor Research

11 (2), 111–143.

Tyler G (1986) Labor at the Crossroads. In: Lipsett S, ed., Unions in Transition: Entering the Second Century, pp. 373–392. San Francisco: ICS Press.

Walsh P, Harbridge R (2001) Re-Regulation in New Zealand: the Employment Relations Act 2000.