A. Definition of Motivation

Motivation has been widely accepted as one of the key factors that

influence the success of foreign language (FL) or second language (L2)

learning. Although it is a term frequently used in both educational and

research contexts, there is little agreement as to the exact meaning of this

concept (Dwinalida, 2015:385). The following are some definitions quoted

from different researchers.

Motivation refers to the choices people make as to what experiences

or goals they will approach or avoid, and the degree of effort they will exert

in that respect (Keller (1983) as cited in Crookes & Schmidt, 1985:481).

When people make certain choice and use effort to attain it, they are

motivated.

From the simple definition, it is developed to be motivation refers to

the direction of attentional effort, the proportion of total attentional effort

directed to the task (intensity), and the extent to which attentional effort

toward the task is maintained over time (persistence) (Kanfer & Ackerman

(1989) as cited in Dornyei, 1998:118). Motivation deals with effort,

proportion, and the maintenance of the effort.

Furthermore, Dornyei (1998:117) defines motivation as a process

persists as long as no other force comes into play to weaken it and thereby

terminate action or until the planned outcome has been reached.

In addition, there is an attempt to achieve a synthesis of conception of

motivation by defining it as a state of cognitive and emotional arousal, which

leads to a conscious decision to act, and which gives rise to a period of

sustained intellectual and/or physical effort in order to attain a previously set

goal (goals) (Williams & Burden (1997) as cited in Dornyei, 2001:46). To

make the three stages of motivation clearer, let’s see the following model of motivation:

special purpose. In addition, motivation is thought to be responsible for why

people decide to do something, how long they are willing to sustain the

activity and how hard they are going to pursue it (Dornyei, 2001:47). The

psycho-social views that to be motivated means to move to do something

(Ryan & Deci, 2000:54). Unlike unmotivated people who have lost impetus

and inspiration to act, motivated people are energized and activated to the end

of a task.

From reviewing various definitions proposed by different researchers,

it is concluded that there has been no general agreement on definitions of

motivation. Besides, motivation research is an area of ongoing debate and,

Although there has been no agreement on definitions of motivation, it

can be seen from the review above that most research agree that it concerns

the direction and proportion of human behavior. Those are:

1. the choice of a particular action;

2. the effort made towards accomplishing that action;

3. the persistence towards accomplishing the action.

Therefore, this research draws a conclusion that motivation is

responsible for:

1. why people decide to learn a language (here in this means English as a

foreign language);

2. how hard they are going to pursue this study;

3. how long they are willing to sustain the activity.

The three elements of motivation are interrelated to one another.

Motivation starts with the learner’s choice of a particular action. Without a

choice in the first place, there will be no motivation at all.

B. Motivation and Foreign Language Learning

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners is described as

situations where learners are learning English in order to use it with any other

English speakers in the world; when learners may be a tourists or business

people (Harmer, 2007:19). Learners often study EFL in their own country, or

sometimes on short courses in Britain, USA, Australia, Canada, Ireland, New

In addition, a lot of research shows that in foreign language learning, a

number of factors can contribute to differences in various learners’ academic

performance and attainment, such as age, gender, attitudes, aptitude,

motivation, learning approach, language learning strategies and learning style

(Dornyei, 1994:274). Among all those contributing factors, motivation has

been regarded by researchers working in the field of second/foreign language

learning as one of the most vital factors in the process of second/foreign

language learning (Dornyei, 2001:275).

Along with ability, motivation is seen as the major source of variation

in educational success (Keller (1983) as cited in Dornyei, 2001:45).

Specifically, these researchers also suggest that motivation of a learner can

indicate the rate and success of second/foreign language attainment. Hsu

(2010:188) also says that learners’ motivation is critical for the effectiveness

of learning foreign language. Therefore, motivation is one of the main

determinants of successful second/foreign language learning (Dornyei,

1994:273).

Besides, Gardner (1985:146) awards great importance to the subjects’ orientation or integral motivation. His socio-educational model seeks to

interrelate four aspects of foreign language (FL) or second language (L2)

learning:

1. Cultural beliefs. L2 learning takes place in specific cultural contexts. The

their attitude towards the community of L2 speakers exerts an important

influence on those subjects’ identities and on the results they obtain.

2. Individual learner differences. These differences are determined by the

degree of:

a. Intelligence, which establishes the efficiency and rapidity with which

subjects perform tasks in class.

b. Language aptitude, which includes several verbal and cognitive

capacities which facilitate learning, such as the capacity for phonetic

codification, grammatical sensitivity, memorization of linguistic

elements, inductive capacity, verbal intelligence, auditory capacity,

etc.

c. Motivation, which involves the subjects’ degree of commitment to L2 acquisition. It integrates three basic components namely desire to

learn, effort towards a goal (L2 learning), greater or lesser

satisfaction in learning (affective component).

3. Learning contexts. The activity of obtaining knowledge within particular

situation.

a. Formal: when L2 learning takes place in the classroom.

b. Informal: it occurs in more spontaneous and natural situations where

there is no formal instruction.

4. Outcomes. The result of teaching and learning process.

a. Linguistic: they refer to linguistic competence: knowledge of

b. Non-linguistic competence: this involves the affective component,

that is, the subjects’ attitudes and values.

In an educational context, Skehan (1989: 49) distinguishes four main

sources of motivation:

1. Learning and teaching activities. Those are related to the learner’s intrinsic motivation. In this case, the learner’s interest to learn would generate motivation, due to the types of tasks (s)he is offered, as such

tasks can generate a greater or lesser degree of motivation.

2. Learning outcomes. The learners’ success or failures are the basis of what is termed resultative motivation. Good results act as a reward and

reinforce or increase motivation, whereas failure diminishes the learners’

expectations, sense of efficiency, and global motivation. In this sense,

motivation is a consequence and not a cause of the learning outcomes.

3. Internal motivation. This dimension is closely related to the first point in

that extrinsic motivation is present in both cases. The difference lies in

the origin of that motivation: whereas in the first case it is to be found in

attractive tasks, in this instance, the learner already has a certain degree

of motivation upon arriving in class, developed due to the influence of

other motivating agents (e. g. importance of languages in present-day

society, parental influence, etc.).

4. Extrinsic motivation. Finally, Skehan (1989:50) highlights the influence

of external incentives (such as rewards or punishment) on the learners’

The afore-mentioned four sources of motivation are presented in the

following table (Skehan, 1989:50):

Table 2.1. Sources of Motivation

Learning contexts Learning outcomes

Outside individuals

In line with this, Crookes and Schmidt (1985:484) hold a perspective

which is less centered upon social factors and more focused on the classroom.

The suggested model relates motivation with L2 learning on four levels:

1. Micro level. At this level, the relationship between attention and

motivation is especially noteworthy. The former is a necessary condition

for L2 learning to take place. In turn, attention is closely tied to interest

and to the subject’s disposition, goals, intentions, and expectations.

2. Classroom level. The events which take place in the classroom are likely

to increase, maintain, or decrease the learners’ motivation. Classroom

tasks, the methodology followed, the type of interaction between teacher

and learners, possible anxiety states, and many other factors, all have an

important bearing on the learners’ motivation. Crookes and Schmidt

(1985:484) also establish a relationship between classroom dynamics and

the learners’ needs for “affiliation”. With the generalized use of

collaborative enterprise, and group work is more frequently employed,

thereby satisfying the learners’ needs of socialization. The effects of the

learners’ perceptions and their expectations should be placed at this level.

3. Curricular level. With the advent of the communicative approach, it has

become essential to explore the learners’ needs as a step prior to curricular planning and implementation.

4. Long-term learning outside the classroom. This level comprises those

learning contexts which are outside the classroom. Certain research has

revealed that motivated L2 learners seek out opportunities in which to

practice the language outside the classroom, such as informal situations

with natives or other contexts.

C. Types of Motivation

1. Gardner’s Model

Led by the pioneering work of Canadian social psychologists,

research into motivation is shaped by social-psychological perspectives

on learner attitudes to target language cultures and people (Gardner &

Lambert (1972) as cited in Lamb, 2007:758). Language learning

motivation is understood differently from other forms of learning

motivation, since language learning entails much more than acquiring a

body of knowledge and developing a set of skills. On top of this, the

language learner must also be willing to identify with members of

behavior, including their distinctive style of speech and their language

(Gardner & Lambert (1972) as cited in Lamb, 2007:759).

Relate to this, there is a speculation saying that learners’ underlying attitudes to the target language culture and people will have a

significant influence on their motivation and thus their success in

learning the language. This speculation gives rise to the now classic

distinction between integrative and instrumental motivation, the former

reflecting a sincere and personal interest in the target language, people,

and culture and the latter its practical value and advantages (Gardner &

Lambert (1972) as cited in Lamb, 2007:760).

In addition, Crookes and Schmidt (1985:471) state that when

learners are driven to learn English because they believe learning it will

benefit them in certain, specific ways (meeting other people, getting a

job, and social pressure), this is referred to as instrumental motivation

because the foreign language (English, in this case) is learned so that it

can be used as a tool to improve the learners’ lives. Crookes and Schmidt (1985:471) state that one will be instrumentally motivation to learn a

foreign language when they recognize the practical advantages provided

by learning the language, for instance, to pass an examination or to

advance economically or socially). In one of research in Egypt, it was

found that adult EFL learners demonstrated instrumental motivation in

that their major goal of learning English was to emigrate to the West

not the only factor, however. Good communicative ability in English

brings with it possibilities for an improved life in Egypt, a high level of

fluency in English implies a high level of education, which therefore

determines a person’s social status, affecting the advancement of careers

in many fields (Kassabgy (1976) as cited in Kassing, 2011:12).

On the other hand of the spectrum lies what is known as

integrative motivation. This type of motivation is driven by an

individual’s desire to learn a foreign language because he or she is

genuinely interested in the culture of the language. Crookes and Schmidt

(1985:474) state that one is integratively motivated if he or she desires to

learn a foreign language simply because they find the target language

culture, group, or the language itself to be attractive.

In one of research, two French dominant bilingual American

graduate learners were interviewed and it was found that they were

intensely motivated to learn French. The conclusion was that this

motivation was the cause of their high competence levels in the L2

(Lambert (1974) as cited in Gardner, 1985:53). One of the learners was

“certain that he did more thinking in French” and only had positive

reactions for French-related materials. This learner, he deemed, was

dominated by integrative motivation. On the other hand, the other learner

was a French teacher at a high school, trying to get a graduate degree in

French. She had to learn French for the sake of her career, and therefore,

1985:55). In addition, in one of research on learners of Welsh, it was

found that their attitudes had significant correlations with their Welsh

proficiency levels. (Jones (1966) as cited in Gardner, 1985:57).

Furthermore, Learner’s ethnocentric tendencies and his attitudes toward the other group are believed to determine his success in learning the new

language (Lambert (1974) as cited in Gardner, 1985:58).

From the explanation above, a question appears then, which is

more effective for foreign language learning? Is it an instrumental drive

to learn a foreign language as a tool or an integrative drive to learn a

foreign language simply because of an attraction to the target language

and culture? While these two motivational factors may be seen as being

in opposition to each other, this is not always true, as in the case of

learners who are motivated by both instrumental and integrative

motivation, those who are motivated by neither, and those who have

higher motivation in one type than another (Crookes & Schmidt,

1985:475). Although there is a commonly held belief that integrative

motivation is stronger than instrumental motivation because instrumental

motivation holds that the learner may or may not actually like the

language being learned and only learn it for the purposes of advancing in

life. Crookes and Schmidt (1985:475) further state that based on several

previous research, it is unclear whether integrative motivation causes

Furthermore, the investigation of the effects of motivation on

foreign language learners emphasized that integrative motivation had an

important role in language learning success (Shaaban & Ghaith (2000) as

cited in Kassing, 2011:15). Ma and Ma (2012:840), however, found that

in the case of Chinese learners in a Chinese cultural setting, learners were

more instrumentally motivated. Ma and Ma (2012:842) attributed this

tendency to the fact that Chinese learners learning English did so because

of the important international role that English holds, as well as

government requirements. In addition, Alrabai (2014:240) found that

Saudi EFL learners were also instrumentally motivated rather than

integratively motivated.

On the other hand, some research has been conducted regarding

the motivation of Indonesian learners. All of these are presented through

the lens of the dichotomist viewpoint and present Indonesian learners as

being purely instrumentally motivated. This may be true, but Indonesian

EFL learners can also be characterized by values and motivations

generally associated with a more integrative motivation (Bradford (2007)

as cited in Nichols, 2014:16).

Additionally, the pragmatic use of English is highly valued,

specifically as it relates to economic gain. The motivations effective for

most Indonesian EFL learners involve the ability to communicate in the

workplace, the possibility to advance to a higher social position, and the

cited in Nichols, 2014:16). In this regard, then, Indonesians fit the model

of instrumental motivation for English language learning. Yet, there are

also elements of integrative motivation in Indonesian EFL learners as

well, though they are mitigated by instrumental concerns. Indonesians do

report using English language media, but they do not identify the desire

to participate in media as a goal for learning English as foreign language.

Furthermore, Indonesians do express a desire to befriend native English

speakers, but they do not desire to integrate. For example, they are not

motivated to mimic native speaker pronunciation or nonverbal

communication techniques. Any attempts to integrate seem to be focused

as means to an end for social or economic advancement and are therefore

more instrumental in nature than integrative (Bradford (2007) as cited in

Nichols, 2014:16).

In line with this, two research conducted in Indonesia, for

instance, revealed that the participants’ motivation in studying English as

a foreign language in two Indonesian high schools were more integrative

than instrumental (Lamb (2004); Liando et al., (2005) as cited in Astuti,

2013:17). This could indicate that the primary reason for studying

English in these research contexts was to be able to have opportunities in

a conversation with English speaking people, rather than pragmatic goals

like in assisting in the pursuit of a career (Liando et al., (2005) as cited in

There is a common belief that integrative motivation is stronger

than instrumental motivation as learners who are instrumentally

motivated may not actually like the target language being learned; yet the

superiority of integrative motivation over the instrumental is debatable,

as research results have varied in different research contexts (Crookes &

Schmidt, 1985:486).

2. Deci’s Model

With the move towards more education-friendly and

classroom-based approaches to the research of motivation, research attention since

the 1990s has increasingly turned to cognitive theories of learner

motivation, thus bringing language learner motivation research more in

line with the cognitive revolution in mainstream motivational

psychology. Cognitive theories focus on the patterns of thinking that

shape motivated engagement in learning. These patterns of thinking

include, for example, goal setting, mastery versus performance

goal-orientation, self-perceptions of competence, self-efficacy beliefs,

perceived locus of control, and causal attributions for success or failure

(Dornyei, 1994:276). From a pedagogical perspective, a key message

emanating from research on cognitive theories of motivation in education

and in language learning is the vital importance of learners having their

own motivation “from within” (Ryan & Deci, 2000:54). The optimal kind

pleasurable rewards of enjoyment, interest, challenge, or skill and

knowledge development. Conversely, extrinsic motivation, that is, doing

something as a mean to some separable outcomes, such as gaining a

qualification, getting a job, pleasing the teacher, or avoiding punishment

(Ryan & Deci, 2000:55).

Relate to this, there is a considerable body of research evidence to

suggest that intrinsic motivation not only promotes spontaneous learning

behavior and has a powerful self-sustaining dynamic but also leads to a

qualitatively different and more effective kind of learning than extrinsic

forms of motivation. This may be because the rewards of learning are

inherent in the learning process itself, in the shape of feelings of personal

satisfaction and enhanced personal competence and skill deriving from

and sustaining engagement in learning (Ushioda (2007) as cited in

Griffiths, 2008:22). Thus, intrinsically motivated learning is not simply

“learning for the sake of learning” (though many teachers would

undoubtedly value such learner behavior in itself); nor it is simply

learning for fun and enjoyment (though many teachers and learners,

especially within primary and secondary school contexts, might regard

“motivating” assynonymous with “fun” as opposed to “boring”). Rather,

intrinsically motivated learners are deeply concerned to learn things well,

in a manner that is intrinsically satisfying and that arouses a sense of

optimal challenge appropriate to their current level of skill and

motivated counterparts, research suggests that such learners are likely to

display much higher levels of involvement in learning, engage in more

efficient and creative thinking processes, use a wider range of

problem-solving strategies, and interact with and retain material more effectively

(Ushioda (2007) as cited in Griffiths, 2008:21).

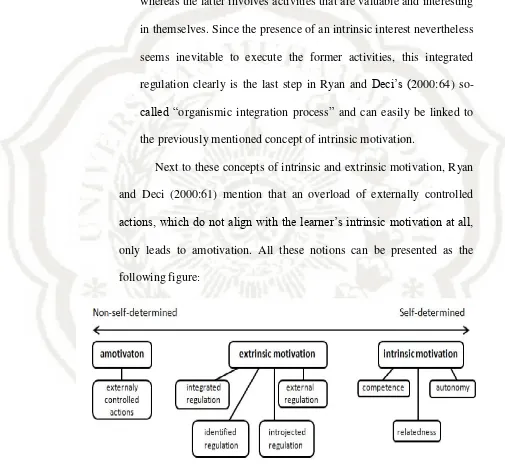

Furthermore, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and

amotivation lie on a continuum from self-determinedness to

non-self-determinedness. Amotivation means there’s no motivation at all or no impetus to make movement, where demotivation is a condition when a

learner has got motivation but because of some factors, it decreases

(Ryan & Deci, 2000:55). Regarding the first ‘category’ of motivation, Ryan and Deci (2000:57) point out that three innate needs that foster

intrinsic motivation can be distinguished:

a. Competence involves understanding how to attain various external

and internal outcomes and being efficacious in performing the

requisite actions.

b. Relatedness involves developing secure and satisfying connections

with others in one’s social milieu.

c. Autonomy refers to being self-initiating and self-regulating of one’s

own actions’ (italics mine).

The second aspect, extrinsic motivation, is divided into four

become “self-regulation”, Ryan and Deci (2000:61) make a distinction

between the following types of regulation:

a. External regulation is the least self-determined form of extrinsic

motivation. An example provided by Ryan and Deci (2000:61)

concerns the wish for praise. In this sense, the behavior is initiated

by another person, most probably the teacher in a classroom context,

and is highly-reward or punishment-driven.

b. Introjected regulation involves internalized rules or demands that

pressure one to behave and are buttressed with threatened sanctions

(e.g. guilt) or promised rewards (e.g. self-aggrandizement) (Ryan &

Deci, 2000:62). The most important difference between this type and

the former one is that no physically present authority is required

here. Although this form of extrinsic motivation consequently finds

itself in the learner, it does certainly not stem from his innate needs.

The example provided by Ryan and Deci (2000:62) concerns a

learner who does not want to be late for class, in order to avoid

feeling guilty.

c. Identified regulation finds itself on the verge of extrinsic and

intrinsic motivation. If the learner identifies with a certain activity,

and hence has come to value it, his behavior is in keeping with his

own convictions.

d. Integrated regulation refers to activities that have become fully

between integrated motivation and intrinsic motivation entails that

the former concerns activities that lead to highly valued results,

whereas the latter involves activities that are valuable and interesting

in themselves. Since the presence of an intrinsic interest nevertheless

seems inevitable to execute the former activities, this integrated

regulation clearly is the last step in Ryan and Deci’s (2000:64)

so-called “organismic integration process” and can easily be linked to

the previously mentioned concept ofintrinsic motivation.

Next to these concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, Ryan

and Deci (2000:61) mention that an overload of externally controlled

actions, which do not align with the learner’s intrinsic motivation at all,

only leads to amotivation. All these notions can be presented as the

following figure:

Figure 2.1. Motivation/Self-Determination Continuum.

This representation of a continuum from external to internal

to stimulate learning, rather than oppose one another (Ryan & Deci,

2000:61). Hence, externally controlled actions can only be beneficial if

they gradually fall in step with intrinsically motivated actions, so that

other-regulation can become self-regulation (Ryan & Deci, 2000:62). As

a consequence, an important task for teachers is to stimulate their

learners’ intrinsic motivation, so as to get the most out of their interests and curiosity. Ryan and Deci (2000:63) point out, “not doing so is like

sailing into the wind”.

As can be derived from the notion of external regulation, a great

pitfall in this context is the use of “surrogate motivators”, which severely undermine intrinsic motivation. When you reward learners for their

behavior, you tend to reduce learners’ interest in performing those behaviors for their own sake (Ryan & Deci, 2000:63).

3. Dornyei’s Model

Among other models which attempt to explain motivation in an

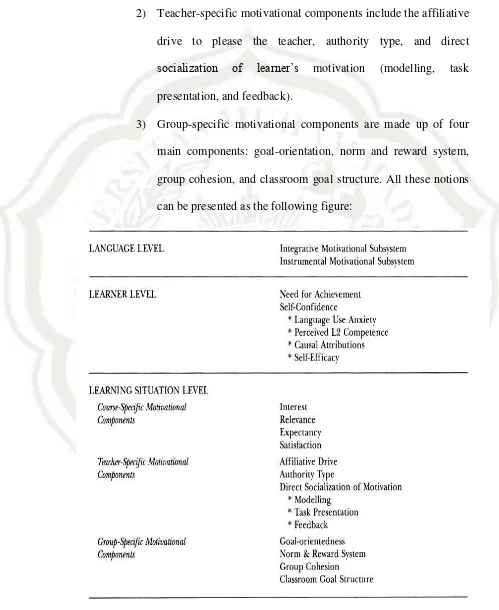

educational context, Dornyei (1994:280) is worthy of mention. In this

model, the components of motivation are organized in three levels which

are somehow related to L2 learning processes (Dornyei, 1994:280):

a. Language Level. The most general level of the construct is the

language level where the focus is on orientations and motives related

to various aspects of the L2, such as the culture it conveys, the

community in which it is spoken, and the potential usefulness of

goals and explain language choice. In accordance with the

Gardnerian approach, this general motivational dimension can be

described by two broad motivational subsystems:

1) The subsystem of integrative motivation is centered around the

individual's L2-related affective predispositions, including

social, cultural, and ethnolinguistic components, as well as a

general interest in foreignness and foreign languages.

2) The subsystem of instrumental motivation consists of

well-internalized extrinsic motives (identified and integrated

regulation) centered around the individual's future career

endeavors.

b. Learner Level. It involves a complex of affects and cognitions that

form fairly stable personality traits. Two motivational components

underlying the motivational processes at this level can be identified

namely need achievement and self-confidence and security (anxiety,

self-esteem, causal attributions, self-efficacy, etc.).

c. Learning Situation Level. It’s made up of intrinsic and extrinsic motives and motivational conditions concerning three areas:

1) Course-specific motivational components are related to the

syllabus, the teaching materials, the teaching method, and the

learning tasks. These are best described by the framework of

four motivational conditions proposed by Crookes and Schmidt

2) Teacher-specific motivational components include the affiliative

drive to please the teacher, authority type, and direct

socialization of learner’s motivation (modelling, task

presentation, and feedback).

3) Group-specific motivational components are made up of four

main components: goal-orientation, norm and reward system,

group cohesion, and classroom goal structure. All these notions

can be presented as the following figure:

D. Levels of Motivation

Highly motivated individual enjoys striving for a goal and makes use

of strategies in reaching that goal (Gardner (2001) as cited in Cheng &

Dornyei, 2007:154). Motivation to learn a foreign language is often triggered

when the language is seen as valuable to the learner in view of the amount of

effort that will be required to be put into learning it. With the proper level of

motivation, language learners may become active investigators of the nature

of the language they are studying.

Similarly, a substantial amount of research has shown that motivation

is crucial for second/foreign language learning because it directly influences

how much effort learners make, their level of general proficiency and how

long they persevere and maintain foreign language skills after completing

their language study (Cheng & Dornyei, 2007:155).

Furthermore, cognitive skills in the target language do not guarantee

that a learner can successfully master a foreign language. In fact, in many

cases, learners with greater second/foreign language learning motivation

receive better grades and achieve better proficiency in the target language

(Brown, 2000:73). No matter how appropriate and effective the curriculum is,

and no matter how high aptitude or intelligence an individual has, without

sufficient motivation, even individuals with outstanding academic abilities are

unlikely to be successful in accomplishing long-term goals (Brown, 2000:75).

In addition, high levels of motivation can make up for considerable

(Dornyei, 2001:51). Likewise, motivated learners can master their target

language regardless of their aptitude or other cognitive characteristics,

whereas without motivation, even the most intelligent learner can fail to learn

the language.

In an EFL setting, for example, in a country like Indonesia, English is

a compulsory subject, so learners definitely have no choice but take the

course. Without effort, persistence will make little sense and motivation will

be greatly weakened. Furthermore, without persistence, motivation will be

terminated and can no longer make any contribution to learning outcomes.

Therefore, both effort and persistence are meaningful elements of motivation

and should receive as much attention as reasons for action. In the particular

setting mentioned above, effort and persistence play a more important role.

In the context of Indonesian learners, having the characteristics of low

motivation is often included (Astuti, 2013:15). One of the causes is the large

classroom size (Bradford (2007) as cited in Astuti, 2013:15). This is

supported by Lamb (2007:770) who found that Indonesian high school

learners are initially motivated to learn but their experience of learning

English at school decreases their motivation over time. In general, Indonesian

learners, like other Southeast Asian learners, tend to be passive and nonverbal

in class. Indonesian learners rarely initiate class discussions until they are

called on. This is because of the nature of the course content, teaching

methods and assessment (Bradford (2007) as cited in Astuti, 2013:16). They

case their answers are incorrect. Moreover, relating English to the daily life of

Indonesian learners becomes another problem in increasing their motivation

in learning the language. It is due to the fact that English is a foreign language

not a second language in Indonesia (Liando, et al., (2005) as cited in Astuti,

2013:17). The learners do not have life experience using English and they are

not expected to be able to speak English in their future careers. The learners

use the Lingua Franca, Bahasa Indonesia, most of the time, at school and

sometimes at home. Clearly, the social and cultural environments do not

provide strong support for learning English (Astuti, 2013:18).

On the contrary, some research has been conducted to find out the

learners’ motivation in learning language. One of the researchers is Martin Lamb (2004:12) who conducted a series of research by looking at 11-12 years

old children’s English learning motivation in the Indonesian context. They are

junior high school learners and most of them start learning English for the

first time. In elementary school, English is not a compulsory subject. Lamb

used open and closed questionnaire items followed by class observation and

interviews. His findings indicated that learners’ motivation both integrative and instrumental in relation to learning English as a global language is

moderate.

E. Basic Assumption

Motivation is one of key factors of success in learning English as

foreign language. Figuring out types and levels of motivation of learners can

educational stakeholders of university, and lecturers or educators of English

to gain better understanding on how to design curricula, syllabuses and

pedagogical practices to stimulate and maintain learners’ motivation through

an understanding of the types and levels of motivation of learners in