Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:15

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

An Examination of the Relationship Between

Academic Dishonesty and Workplace Dishonesty:

A Multicampus Investigation

Sarath Nonis & Cathy Owens Swift

To cite this article: Sarath Nonis & Cathy Owens Swift (2001) An Examination of the Relationship Between Academic Dishonesty and Workplace Dishonesty: A Multicampus

Investigation, Journal of Education for Business, 77:2, 69-77, DOI: 10.1080/08832320109599052 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320109599052

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 906

View related articles

An Examination

of

the Relationship

Between Academic Dishonesty and

Workplace Dishonesty:

A

Multicampus Investigation

SARATH NONE

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Arkansas

State UniversityState University, Arkansas

hat is the relationship between

W

academic dishonesty and work- place dishonesty? If a student is prone to cheating in college, will that same student be prone to cheating in the workplace? Although an extensive body of literature deals with either academic dishonesty or workplace dishonesty, only a single study to date (Sims, 1993) has dealt with the possible relation between these behaviors. In this study, we attempted to bridge the gap between these related fields of study.One need only read today’s headlines to know that unethical behavior seems to be on the increase. The scandals in the Oval Office regarding sexual harass- ment, infidelity, lying under oath, and illegal campaign contributions only confirm that unethical behavior can be found at all levels. Indeed, Jones and Gautschi (1988) have suggested that the fall of television evangelists, pollution controversies, and leveraged buyouts and hostile takeovers leading to down- sizing and layoffs over the past decades have convinced some that “the sky is falling” in terms of ethical conduct.

Polls have shown that business exec- utives are the lowest ranked category among professional groups in perceived

ethical behavior (Stevens, Harris,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&Williamson, 1994). Members of the business profession have been accused of subordinating, abusing, and ignoring their ethical responsibilities (Stevens &

CATHY OWENS SWIFT

Georgia

Southern UniversityStatesboro, Georgia

ABSTRACT. This article addresses academic integrity in both the class- room and the work environment. The authors distributed an in-class ques- tionnaire to a sample of business stu-

dents from

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

6 different campuseszyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(N =1,051). The study was

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an attempt tobridge the gap between findings relat- ed to academic dishonesty and those regarding dishonesty in the work- place. The authors found that students who believed that cheating, or dishon- est acts, are acceptable were more likely to engage in these dishonest behaviors. Additionally, students who engaged in dishonest acts in college classes were more likely to engage in dishonest acts in the workplace. The authors suggest some techniques to discourage dishonesty in the class- room.

Stevens, 1987). Increasingly, corpora- tions are the targets of accusations of ethical violations. In fact, Cole and Smith (1995) suggested that the term “business ethics” has become an oxy- moron to some. Recent headlines have highlighted unethical business prac- tices, such as those by 13 engine makers in the United States who were fined for illegally equipping engines with com- puterized devices to ensure that they would run cleaner in federal emissions tests than they would under normal con- ditions on the road (Cole, 1998).

What message do these unethical behaviors send to today’s youth, who

will compose our future workforce? Studies report that the incidence of cheating on college campuses is at an all-time high, with the percentage of students cheating ranging from 30% to 96% (Berton, 1995; Diekhoff, et al.,

1996; Haines, LaBeff, Clark, & Diekhoff, 1986; Nonis & Swift, 1998). Some studies have reported that busi- ness students have lower ethical values than nonbusiness students (Harris, 1989). Others have found that business students are more willing to engage in questionable behaviors than are non- business students (Wood & Longeneck- er, 1988). Stevens, Harris, and Williamson (1994) found that business faculty have a slightly higher tolerance for questionable business practices than do faculty in other disciplines.

What impact does dishonest behavior in college have on future behavior in the workplace? In study of the medical pro- fession, Baldwin and Daugherty (1996) found that the best predictor of cheating in medical school was having cheated previously in one’s academic career, either in high school or college. Fass (1990) observed a correlation between cheating in school and cheating in pub- lic arenas such as income tax payment, politics, and college athletics. Another study indicated that communications majors who cheat in college will become the next dishonest communications pro-

fessionals (Todd-Mancillas, 1987).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

NovembedDecember

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2001 69The purpose of the current study was threefold. First, we evaluated business students’ beliefs about various forms of dishonest behaviors at work. Second, we attempted to determine the relation- ship between student beliefs about dis- honest behaviors and the frequency of occurrence of these behaviors in the workplace. If a relationship exists, this result should provide additional confir- mation of the need for moral training among college students in colleges and universities. Finally, we attempted to determine the relationship between dishonesty in college and dishonesty in the workplace. Even though we are neither proposing nor evaluating a cause-and-effect relationship in this study, if a significant relationship should exist, the results will downplay the situational (contextual) influence on dishonest behavior. That is, if dis- honest behaviors are situation-specific, there should not be a relationship between dishonest behaviors in college and dishonest behaviors in the work- place.

The problem of academic dishonesty in higher education has received consid- erable attention in the past decade

(McCabe

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Trevino, 1997). However,only Sims (1993) has investigated the relationship between academic dishon- esty and workplace dishonesty among business students. One limitation of the Sims study was the very small sample of 57 graduate students included in the study. In our study, we used a multi- campus sample including both graduate and undergraduate students. Thus, our findings should be generalizable to the

larger business student population.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Dishonesty in the Workplace

Workplace crime, particularly employee theft, is a major problem fac- ing American business and industry today (Payne & Pettingill, 1983). Loss- es from fraud and theft by employees exceed losses from fire (Gray, 1997).

According to

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

U.S. Chamber of Com-merce estimates, American businesses lose more than $50 billion annually to employee-related crimes (Fitzpatrick, 1995). That figure, of course, does not include the billions of dollars spent on protecting against such thefts, including

security guards, security systems, and insurance.

The National Retail Federation found that over several years there was a slight decline in the percentage of crime loss- es attributed to shoplifting but an increase in those committed by employ- ees (McCormick, 1997). The Associa- tion of Certified Fraud Examiners (Gray, 1997) recently estimated that fraud and other employee crimes cost employers more than $400 billion per year, or $9 per day per worker on aver- age. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce

has noted that 75% of employees likely steal at least once and that half of these steal repeatedly (U.S. Mutual Associa-

tion, I998), and the American Manage- ment Association has estimated that employee dishonesty causes as much as 20% of the nation’s business failures (McCormick, 1997). Not only is employee theft increasing but the aver- age amount stolen is staggering. One survey showed that retail employees steal seven times as much as shoplifters

(Meyer, 1994), and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Trendwatch (1 998)suggested that one dishonest employee steals nine times as much as the average shoplifter.

Over time, studies on crime have indicated an increase in frequency of such crimes. Homing (1 970) found that workers in an industrial plant regarded stealing small items from the company not as stealing but as “taking things from the plant.” Hollinger and Clark (1983) discovered that two thirds of employees in a sample admitted to some level of counterproductive behav- ior and one third admitted that they had stolen company property. In a 1991 study, over 96% of employees consid- ered themselves honest yet admitted to having stolen something from their employers (Roderick, Jelley, Coiok, & Forcht, 1991). Additionally, when they were asked if they felt guilty about steal- ing, over 60% of those who had stolen things from their employers answered “no.”

What is the origin of this increase in employee dishonesty? Frustration with the job accounts for 5% to 10% of employee theft (Albrecht & Wernz, 1993). Another study suggested that dis- honesty comes from three factors: lack of individual integrity, personal pres-

sures, and opportunity (Albrecht, Wernz, & Williams, 1995). One theory is that personal values and organization- al values determine ethical behavior, regardless of anything that is learned in college (Gellerman, 1986). Hosmer

( 1 988) suggested that ethical standards

are set by families, schools, churches, and peers long before a student reaches college.

Academic Dishonesty

The undergraduate experience is often the first time a student is away from home and family. Students are exposed to new influences, new peers, and new ideas while in the university environment. Glenn (1992) found that students can learn to make more ethical decisions by taking a business ethics course. Therefore, studying academic dishonesty at college may provide some clues to dishonesty at work.

According to the American Council on Higher Education, academic dishon- esty, or cheating, is on the increase (Nowell & Laufer, 1997). The percent- ages of those found to have cheated range from 40% to 60% (Rittman, 1996) to 80% (Nonis & Swift, 1998). Other reports (CAI, 1998) have indi- cated that chronic cheating is preva- lent, and that those who cheat once are more likely to cheat with increasing frequency. Another study on student attitudes toward cheating found that 70% of the students either did not view cheating as a problem or viewed it as a trivial one (Bunn, Caudill, & Gropper, 1992).

Marketing students who cheated said that they did so because dishonesty sur- rounds them in college and society (Allen, 1998). Another study on market- ing students determined that those who had cheated in the past were likely to cheat again (Nonis & Swift, 1998). Additionally, those who cheated on exams were likely to cheat on out-of- class assignments and projects (Swift & Nonis, 1998). However, Duizend and McCann (1998) found that taking a business ethics class affected students’ propensity to engage in unethical or ille- gal business practices.

Roig and Ballew (1994) found that

business and economics majors had

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

70 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessmore tolerant attitudes toward cheating than did those in other majors. Business faculty were also found to have a higher tolerance for unethical situations than faculty in other disciplines (Stevens,

Harris,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Williamson, 1994). Harris(1 989) determined that business stu- dents had lower ethical values than non- business students did, and Wood and Longenecker (1 988) determined that business students were more willing to engage in questionable behaviors than their nonbusiness counterparts were. Etzioni (1989) even suggested that the average curriculum of the business school has hidden assumptions that could lead business students to believe that unethical decisions are necessary for success. Business schools have been blamed for teaching students to be successful at the cost of social and ethical responsibilities (Stevens et al.,

1993).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Development of Hypotheses

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Beliefs and Attitudes About Dishonest Behaviors on the Job

Research on the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior has estab- lished that attitude is a reliable predictor of intentions and behavior (Ajzen, 1969; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein

& Ajzen, 1975). Fishbein and Ajzen

( 1994) defined attitude toward an act as the degree to which an individual has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior in question. Attitude is therefore dependent on the individual’s beliefs and his or her evaluation of those beliefs.

These theories can be applied to dis- honest behavior in college and in the workplace. If beliefs and attitudes influ- ence behaviors, it is reasonable to expect that individuals who believe dis- honest acts to be acceptable behavior are more likely to engage in dishonest behavior in the workplace than those who believe dishonest acts to be less acceptable. Thus, we formulated our first hypothesis:

H,: Individuals who believe dis- honest acts to be acceptable behavior will engage in dishonest acts more fre- quently than individuals who believe dishonest acts to be less acceptable.

Relationship Between Dishonesty at College and Dishonesty at Work

Media reports of school surveys and work behavior have highlighted the state of intellectual dishonesty in Amer- ican schools and social institutions (Deursch, 1988; McLoughlin, 1987). Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper (1992) saw a similarity between cheating in the classroom and the crime of theft. They likened the professor and student peers to policemen and the cheating student to the criminal. Although Glenn and Van Loo (1993) found that business students make less ethical choices than business practitioners, they questioned whether the reason is that the students have lower ethical standards or whether they are just naive and not knowledgeable about what is right and wrong.

Sims (1993), in a study of business students, suggested that if students cheat in college and are then hired on academic credentials that they obtained dishonestly, employers who hire them will suffer. He determined that students who engage in a wide range of academ- ic dishonesty also engage in a wide

range

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of work-related dishonesty. Hisfindings suggest that if individuals believe that dishonesty is an appropriate behavior in one context (college), they will believe that it is appropriate in oth- ers (work). Ogilby (1995) discovered that a majority of students believe that there is a direct correlation between aca- demic behavior and behavior in the business world. These findings led us to our second hypothesis:

The frequency of cheating in college is positively related to the fre- quency of cheating at work.

H,:

Method

We collected data from a sample of 1,05 1 business students in both graduate and undergraduate business classes at six AACSB-accredited universities in the South and Midwest. We selected classes at each university to obtain a proportional sample of classes, majors, ages, and class levels. The question- naires were administered in class, and students were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Fifty-two percent of the respondents

were men, and 48% were women. Sev- enty-four percent of the respondents were undergraduates; 26% were gradu- ate students. We compared the sample characteristics with demographic charac- teristics of college students in the United States (The Chronicle of Higher Educa-

tion, 1998) and found that they were comparable in that no demographic char- acteristic was over- or underrepresented. Therefore, the sample can be considered representative of the population.

Beliefs About Dishonest Acts at Work

We measured beliefs about dishonest behaviors at work through 18 items from Sims (1993) and three items adapt- ed from Hilbert (1988). We asked stu- dents to respond to this section of the questionnaire only if they had had a

part-time or full-time job in the previous

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 years. We provided a list of behaviors and asked students, “Please indicate whether you believe each of the follow- ing activities is dishonest by circling the correct number, where 1 = dejnitely cheating, 2 = probably cheating, 3 =

probably not cheating, and 4 = dejnite-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ly not cheating.”

Academic Dishonesty

We measured academic dishonesty through 44 separate items adapted from a variety of studies (Ferrell & Daniel, 1995; Franklyn-Stokes & Newstead, 1995; Sims, 1993; Stevens & Stevens, 1987; Tom & Borin, 1988). After pro- viding a list of behaviors representing a continuum of cheating and noncheat- ing activities, we asked students to think about their experiences in college and indicate, in general, how often they had participated in each of the activities on a scale ranging through 1 (never), 2

(seldom), 3 (occasionally), 4 (ofen), and

5 (very ofen). We averaged the scores of

these 44 items to form a composite score of academic dishonesty frequency.

The majority of studies on cheating behavior have used either experimental situations or self-reported dishonest behavior. It has been suggested that the self-reporting of one’s own deviant behavior, as in this study, may result in underreporting of these behaviors (Scheers & Dayton, 1987). However,

NovembedDecember 2001 71

Rost and Wild (1994) have claimed that questionnaires are a standard instrument and that providing conditions of

anonymity ensures an honest response.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Work-Related Dishonest Behavior

We measured work-related dishonest behavior through the same items taken from Sims (1993) and Hilbert (1988). As previously, we asked students to respond to this section of the questionnaire only if they had had a part-time or full-time job in the previous 5 years. Behaviors were provided, and students were asked to indicate how often they participated in them on the job by circling the corre- sponding number on the same 5-point scale used to measure academic (dis)honesty. We averaged the scores of these 2 1 items to form a composite score

of work-related dishonest behavior.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Results

In Table 1, we provide the means, standard deviations, and simple correla- tion coefficients (Pearson product moment correlation coefficients) for selected demographic variables (gender and age) and variables under investiga- tion. Reliability coefficients for fre- quency of academic dishonesty, beliefs about work-related dishonest actions, and work-related dishonest actions (behaviors) are provided on the diago- nal. All scales demonstrated excellent reliability coefficients with the guide- lines provided by Nunnally (1978).

Consistent with previous studies

(McCabe

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Trevino, 1997; Nonis &Swift, 1998), both demographic vari- ables gender and age showed significant correlation coefficients with frequency

of cheating at college. The negative cor- relation coefficients (in the data entry,

men were coded as

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

“0’ and womenwere coded as “1”) demonstrate that male students and younger students were more dishonest in college than female students and older students. In the workplace, gender demonstrated ‘a significant relationship with dishonest work behaviors. However, in this situa- tion, age was not significant.

The first objective of the study was to evaluate business students’ beliefs about various forms of dishonest behaviors at work. For this purpose, we obtained fre- quencies for the 21 statements of mea- sured dishonest actions at work (see Table 2). For over half (12) of the dis- honest actions, more than 10% of the respondents felt that they were probably not or definitely not cheating (dishon- esty). This finding has significant impli- cations and will be discussed later.

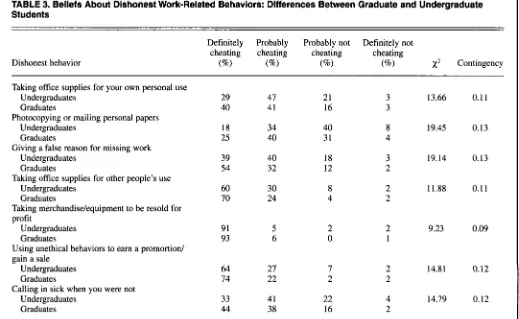

Because the sample consisted of both undergraduate and graduate students, we decided to determine whether the beliefs held differed between the two groups. We conducted cross-tabulations and chi-square tests for this purpose. For every belief regarding the seven dis- honest actions included in Table 3, there were significant relationships between these variables and student classifica- tion (graduate or undergraduate) at the .05 level. Beliefs not included in Table 3 did not demonstrate any significant rela- tionship with student classification. The contingency coefficient shows the strength of the relationship between the two variables, student classification and beliefs about dishonest actions. For all items, graduate students felt these actions to be more dishonest than under- graduate students did.

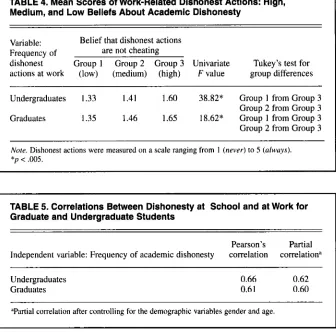

We tested our first hypothesis through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test. Because we found significant differences in beliefs about dishonest behaviors between graduate and undergraduate students, we conducted separate analyses for the two groups. In both analyses, the inde- pendent variable was the measure of students’ beliefs and the dependent vari- able was the frequency of dishonest behaviors at the workplace.

To allow analysis, we divided stu- dents’ average response to the compos- ite value of dishonest beliefs into three subgroups based on lower third (33rd percentile), middle third (between the 33rd and 67th percentiles) and upper third (67th percentile) for both under- graduates and graduates separately. Results from the ANOVA and Tukey’s test are provided in Table 4. We found significant differences in means for work-related dishonest behavior between students categorized as “low” and “medium” regarding beliefs about dishonest actions and those categorized as “high” regarding those beliefs, at the

.05 significance level. We identified dif- ferences in means for both graduate and undergraduate samples. These results support H,, that individuals who believe dishonest acts to be acceptable will engage in dishonest acts more frequent- ly than those who believe dishonest acts to be less acceptable.

We tested our second hypothesis through partial correlation coefficients, controlling for the variables gender and age. Numerous studies (including this one) have indicated that these two vari- ables are significantly correlated with dishonest behaviors in college. Both Pearson’s product moment correlation

TABLE 1. Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations, and Reliability Coefficients’ for the Sample

Variable

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M SD 1 2 3 4 51. Gender

-

2. Age 24.25 5.86 -.05 -

3. Beliefs about dishonesty at work 1.71 0.44 -.09* -.12** ( 9 1 )

4. Frequency of academic dishonesty 1.49 0.4 1 -.12** -.24** .37** (.93)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 . Frequency of workplace dishonesty 1.55 0.38 -.15** -.02 .64** .64** (39)

“Reliability coefficients are provided within parentheses

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

*p < .05. **p < .01.

72 Journal of Education for Business

TABLE 2. Beliefs About Dishonest Work-Related Behaviors, by Percentage of Respondents

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Dishonest behavior

Definitely Probably Probably not Definitely not cheating cheating cheating cheating

(1) (2) (3) (4)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MaPhotocopying or mailing personal papers Giving preferential treatment to family/friends Completing personal business on company time Taking office supplies for your own use Calling in sick when you were not

Withholding the total truth to cover up other people’s mistakes Doing less than your share of work in a group project Giving a false reason for missing work

Making long-distance personal telephone calls from work

Taking long lunches or leaving early when your supervisor is not present Withholding the total truth to cover up for your own mistakes

Breaking something that belongs to your company and not reporting it

Taking office supplies for other people’s use

Using unethical behaviors to earn a promotion/gain a sale Taking merchandise/equipment for one’s own personal use Coming to work under the influence of drugs, including alcohol Reporting expenses incurred different from the actual total Taking credit for work that someone else completed Reporting hours worked different from the actual total Taking merchandise/equipment to be resold for profit Taking money from the company

20.0% 20.9 21.3 31.8 35.9 33.0 35.0 43.1 44.7 45.8 45.8 47.2 62.8 66.4 71.3 76.7 74.8 77.8 80.1 91.6 92.0

35.2% 42.6 50.2 45.4 40.4 50.1 48.3 37.5 40.5 40.2 42.7 40.4 28.7 25.5 22.3 15.4 21.4 18.1 15.7 5.4 5.4

37.1% 28.3 25.2 19.5 20.3 15.2 14.6 16.6 12.1 12.0 9.7 9.9 7.0 5.8 5.0 5.5 2.6 2.7 3. I 1.6 1.4

7.2% 2.32 8.0 2.23 2.8 2.10 2.4 1.92 3.2 1.91 1.5 1.85 1.9 1.83 2.7 1.79 2.5 1.72 1.8 1.70 1.7 1.67 2.2 1.67 1.2 1.46 2.0 1.43 1.2 1.36 2.3 1.33 1.1 I .30 1.3 1.27 0.9 1.25 1.2 1.12

1.1 1.12

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

”Mean was computed on the basis of each respondent’s raw score on the item.

TABLE 3. Beliefs About Dishonest Work-Related Behaviors: Differences Between Graduate and Undergraduate Students

Dishonest behavior

Definitely Probably Probably not Definitely not cheating cheating cheating cheating

(%I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(%> t%) (%Ix2

ContingencyTaking office supplies for your own personal use

Undergraduates 29 47 21 3 13.66 0.1 I Graduates 40 41 16 3

Photocopying or mailing personal papers Undergraduates

Graduates Undergraduates Graduates Undergraduates Graduates

Giving a false reason for missing work Taking office supplies for other people’s use Taking merchandiselequipment to be resold for profit

Undergraduates Graduates

Using unethical behaviors to earn a promortion/ gain a sale

Undergraduates Graduates Undergraduates Graduates

Calling in sick when you were not

18

25 39 54 60 70 91 93 64 74 33 44

34 40 40 32 30 24 5 6 27 22 41 38

40 31 18 12 8 4 2 0 7 2 22 16

8 19.45 0.13 4

3 19.14 0.13 2

2 11.88 0.11 2

2 9.23 0.09 1

2 14.81 0.12 2

4 14.79 0.12

2

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. All relationships were significant at p < .05.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

November/December 2001

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

73

[image:6.612.48.567.389.708.2]TABLE 4. Mean Scores of Work-Related Dishonest Actions: High,

Medium, and Low Beliefs About Academic Dishonesty

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Variable: Belief that dishonest actions

Frequency of are not cheating

dishonest Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Univariate Tukey’s test for

actions at work (low) (medium) (high)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

F value group differencesUndergraduates 1.33 1.41 1.60 38.82* Group 1 from Group 3

Group 2 from Group 3 Graduates 1.35 1.46 1.65 18.62* Group 1 from Group 3

Group 2 from Group 3

Note. Dishonest actions were measured on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 (always).* p <

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

,005.TABLE 5. Correlations Between Dishonesty at School and at Work for Graduate and Undergraduate Students

Pearson’s Partial Independent variable: Frequency of academic dishonesty correlation correlation”

Undergraduates

Graduates

0.66 0.62 0.6 1 0.60

“Partial correlation after controlling for the demographic variables gender and age.

coefficients (simple correlations) and partial correlation coefficients (see Table 5) support H,, that the frequencies of academic dishonesty and work dis- honesty are positively correlated (p < ,005). The partial correlations were somewhat lower than simple correla- tions for both groups due to overlapping variance of controlled variables with the independent variable and frequency of dishonesty at work.

Discussion

Our study’s findings are similar to those from other studies focusing on the relationship between cheating and cer- tain demographic characteristics. Acad- emic dishonesty occurred more fre- quently among younger students and male students. These two subgroups also were more tolerant of workplace dishonesty. Dishonest behavior in the workplace was related only to gender: that is, male students were more likely to actually engage in workplace dishon- esty than female students were.

May and Loyd (1993), Terpstra,

Rozell, and Robinson (1993), and Bud- ner (1987) have suggested that these differences can be explained by gender- role socialization theory. That is, throughout history, women have been conditioned socially and culturally to be more concerned with obediance to rules and acting morally. Terpstra et al. have also suggested that, because men tend to be more competitive, the finding that competitive individuals exhibit a predilection for unethical behavior pro- vides additional support for such a dif- ference between genders.

What significance does this knowl- edge have for faculty members? Obvi- ously, instructors cannot be advised to try to identify potential cheaters accord- ing to gender alone. A more proactive solution would be to plan active discus- sion of moral behavior during class and encourage female students to share their

ethical reasoning with other students.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Beliefs About Dishonest Work Behavior

Perhaps our most disturbing findings related to student beliefs regarding dis-

honest work behaviors. More than 10% of the respondents identified 12 of the 21 dishonest behaviors as probably not or definitely not examples of cheating. Some of these behaviors may be viewed as rather innocuous, such as “withholding the total truth to cover up for your own mistakes” or “doing less than your share of work in a group pro- ject.’’ Diekhoff et al. (1996) expressed concern that cheating in the academic environment may have become norma- tive behavior for today’s students, as they are under tremendous pressure to get good grades. There is also a con- cern that cheating is a “slippery slope” that starts with a relatively minor infraction and leads to more serious ethical blunders. This deterioration of ethical behavior has been blamed on changing attitudes toward education (Schulman, 1998). Whereas education was valued for its own sake in the 1960s, today the university is viewed more as a credentialing institution, and thus students are more easily able to rationalize cheating.

Even company attitudes toward dis- honest work behavior may have changed. Payne & Pettingill (1983) have noted the significant problem of “local tolerance.” Some companies take a strict position and punish employees for any type of cheating behavior, no matter what the circumstance. Other companies take a more tolerant position and allow small levels of dishonesty without disciplinary action.

Assuming that graduate students would have more actual work experi- ence than undergraduates, we com- pared the responses for each of these groups. As discussed earlier, there were significant differences between the two groups on seven, or one third, of the responses. Regarding the corre- sponding seven behaviors, graduate students were much less tolerant than undergraduates and believed the actions to be more dishonest. This find- ing supports Byrne’s (1992) suggestion that ethical values and the process for determining ethical behavior cannot be taught but rather must be learned in actual life settings. Thus undergradu- ates, with less real work experience, may not be aware of the ethicality of some of these actions.

74 Journal of Education for Business

[image:7.612.50.386.45.377.2]Beliefs Versus Actions

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

We found a significant relationship between students’ beliefs about whether a work behavior is cheating and the fre- quency of their actually engaging in it. This finding, which held true for both undergraduates and graduates, has important implications for both academ- ic institutions and business organiza- tions. Students who believe that there is nothing wrong with taking office sup- plies for their own personal use also tend to be people who take the supplies for their own use. This demonstrates the importance of helping to increase stu- dents’ awareness and understanding of what is unethical behavior. Roth and

McCabe

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(1 995) suggested that it maynot be possible to convince students to value integrity and honesty if they do not do so already when they arrive on cam- pus. However, faculty members may be able to persuade them to change their behaviors during their college stay. By means of a pre- and posttest, Glenn and Van Loo (1993) found that students in an ethics class learned to make more ethical choices by the end of the semester. On the other hand, Kumar, Borycki, Nonis, and Yauger (1991) found that students who were exposed to the strategic deci- sion framework, commonly taught to business students in the study of ethics, gave less consideration to ethical issues involved in decisionmaking than did stu- dents not exposed to the framework. Their conclusion was that the business curriculum and the way that it is taught may give students the mistaken impres- sion that success requires unethical or less-than-ethical decisions.

Findings from both Glenn (1992) and Kumar et al. (1991) clearly suggest the importance of discussing ethics throughout the business curriculum and not simply in a specialized class. Such discussion will enable the students to understand the implications of dishon- est behaviors in a variety of settings and possibly change students’ attitudes as well as the behaviors.

Relationship Between Academic Dishonesty and Workplace Dishonesty

In this study, we found a high corre- lation between the frequency of cheat-

ing at college and the frequency of cheating at work. Even controlling for age and gender differences, we found that students who cheated in the acade- mic setting tended to cheat in the corpo- rate setting also. This finding, which supports previous findings regarding business students (Ogilby, 1995; Sims, 1993), also has important implications for both academic institutions and busi- ness organizations. Results seem to

indicate that cheating is not situation specific. Once an individual forms the attitude that cheating is acceptable behavior, he or she is likely to use this behavior, not only in the educational arena but also in other areas.

Other studies have found that certain deterrents can influence the level of

cheating in the classroom (Barnett

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&Dalton, 1981; Nonis & Swift, 1998; Singhal, 1982). If students can be con- vinced not to cheat in their college classes, they may continue that pattern of behavior in the workplace and become more honest employees.

Business organizations should also have an interest in curbing academic dishonesty. With the increase in work- place fraud and white-collar crime, there is a need for a workforce that is grounded in ethical behavior. What bet- ter place to learn this ethical behavior than in the college classroom? If college prepares students for successful careers, then the college experience should also prepare students for how to deal with unethical behaviors inside and outside of the classroom.

Call for Faculty Action

Faculty members are responsible for encouraging ethical behavior among stu- dents. Faculty should establish a univer- sity-wide climate of academic integrity by enforcing ethical standards, modeling appropriate behavior, and teaching ethi- cal decisionmaking in the classroom. McCabe (1993) suggested that the real key to curbing academic dishonesty is to involve every member of the academic community in honest and open commu- nication about the value and importance of academic integrity. If students are involved in establishing and evaluating academic integrity, their own classroom behaviors may be improved.

The university must consistently communicate its rules regarding acade- mic dishonesty to students, faculty, and administrators, and all parties must be willing to accept and support the con- cepts. Campus-wide forums should be conducted to educate all parties. Sharing these responsibilities will help develop a

sense of community and create a sense of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

pride and honor among all.

McCabe and Trevino (1996) called for the creation of an environment in which academic dishonesty is “socially unacceptable.” However, academic hon- esty cannot be imposed on students; it must be accepted by them. Student par- ticipation in the development of the stan- dards of ethical conduct as well in the enforcement of those standards should help establish involvement and committ- ment. Students can also be involved in peer education and the continual evalua- tion of academic integrity policies.

Ethical standards in the classroom.

Having an Academic Dishonesty Policy

is not enough. In one study (Jendrek, 1989), 60% of faculty members observed cheating in their classrooms, but only 20% of them actually met with

the student and a higher authority. Diekhoff et al. (1996) suggested that faculty members hesitate to deter cheat- ing because they believe that they will not be supported at the administration level, Saunders (1 993) also suggested that instructors may tend to ignore cheating to avoid potential litigation and/or disciplinary hearings. It is also possible that faculty rationalize that a cheating student will cheat in other classes, too, and hope that some other professor will report the student. How- ever, if most faculty members do not report a student who cheats, that indi- vidual could cheat his or her way through school. If instructors do not fol- low the policies set forth by the institu- tion, they may be sendng a message to students that cheating is acceptable.

As suggested by Davis (1987), to ensure that students internalize academ- ic standards, faculty members “must openly and uniformly support such eth- ical behaviors” (p. 19). Therefore, instructors should clearly state their own academic dishonesty policies and clearly define dishonest behavior on the

NovembedDecember 2001

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

75syllabi. Additionally, they should hold discussions about what they regard as cheating and plagiarism, as well as the consequences for students who are

caught cheating.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Faculty as role models. In addition to enforcing academic standards of behav- ior in the classroom, instructors should also model high standards of ethical conduct. David, Anderson, and Law- rimore (1990) found that 92% of gradu- ates who had been out of school for sev- eral years believed business professors’ actions to be one of the most important factors in students’ development of eth- ical standards and values. One study

(Jones

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Gautschi, 1988) found thatzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MBA students saw faculty members as more attentive to ethical standards than other parties, including student peers, workplace supervisors, and business executives. Sauser (1990) also found that the behavior of business professors taught students more about ethical behavior than any other technique.

Daniel, Adams, and Smith (1994) suggested that students resent some pro- fessors who spend too much time out- side of class on research and consulting efforts. If the professors are not involved actively in the classroom, this resentment could lead students to pay less attention to their own class commitments and therefore be more susceptible to cheat- ing. Faculty members must be models of integrity for students and follow all of the rules of conduct themselves.

Ethics classes. Many experts as well as parents of students (Nazario, 1992) believe that ethics can be taught and that business professors have a responsibili- ty to teach ethical skills and decision- making. Yet more than two thirds of stu- dents in one study reported that the topic of white-collar crime had received little or no emphasis in business classes (Roderick et al., 1991), even though the topic of ethics is recommended for the AACSB-accredited curriculum.

Students need to learn that ethical issues are an important part of the busi- ness world and that these decisions have an impact on the company beyond legal ramifications (Kumar et al., 1991). Integrity must be taught and ethical issues discussed in every course, with

particular emphasis in the capstone course. Through lecture, class discus- sion, cases, role playing, guest speakers, and outside readings, students should be exposed to a wide variety of ethical sit- uations, with discussions of right and wrong courses of action, so that a strong ethical foundation is ingrained in them by the time they enter their first full-

time positions.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Conclusion

Using a sampling frame of business students (from all business disciplines) at six different campuses, in this study we obtained two major results: (a) Stu- dents who believed that dishonest acts are acceptable were more likely to engage in those dishonest acts than were those who believed the dishonest acts were unacceptable, and (b) students who engaged in dishonest behavior in their college classes were more likely to engage in dishonest behavior on the job. Our results suggest that if students do not respect the climate of academic integrity while in college, they will not respect integrity in their future profes- sional and personal relationships. Edu- cation and communication can create a shared commitment to academic integri- ty among students, faculty, and adminis- trators. It is essential that institutions demonstrate a commitment to the enforcement of academic dishonesty policies and provide the resources to help deter cheating in the classroom.

Students have indicated that, when they feel like real members of the cam- pus community, believe that faculty members are committed to ethical stan- dards, and are aware of their institu- tions’ policies regarding academic dis- honesty, they are less likely to cheat (McCabe & Trevino, 1996). When stu- dents support standards of academic integrity, they realize their responsibili- ties in regard to ethical behavior. This core value of the institution becomes their own individual core value, which they carry into their future careers.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Engle- wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I. F., & Fishbein, M. (1969). The predic-

tion of behavior intentions in a choice situation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 5, 234-244.

Albrecht, W. S . , & Wernz, G. W. (1993). The three factors of fraud. Security Management, 37(7),

Albrecht, W. S . , Wernz, G. W., &Williams, T. L. (1995). Fraud: Bringing light to the dark side of business. Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin Professional Publishing.

Allen, J., Fuller, D., & Luckett, M. (1998). Acad- emic integrity: Behaviors, rates, and attitudes of business students toward cheating. Journal of Marketing Education, 20( I), 41-52.

Baldwin, D. C., & Daugherty, S. R. ( 1 996). Cheat- ing in medical school: A survey of second-year students at 3 1 schools. Academic Medicine, 71, 267-273.

Barnett, D. C., & Dalton, J. C. (1981). Why col- lege students cheat. Journal of College Student Personnel, 22(6), 545-55 1.

Berton, L. (1995, April 25). Business students hope to cheat and prosper, a new study shows. Wall Street Journal, 225(80), B I .

Budner, H. R. (1987). Ethical orientation of mar- keting students. The Delta Phi Epsilon Journal. 29(3), 91-99.

Bum, D. N., Caudill, S . B., & Gropper, D. M. (1992). Crime in the classroom: An economic analysis of undergraduate student cheating behavior. Research in Economic Education. 23(3), 197-208.

Byrne, J . A. (1992, April). Can ethics be taught?

Harvard gives it the old college try. Business

Week, 6,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

34.Center for Academic Integrity (CAI). (1998).

Some research highlights. Retrieved from

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

http://www.academicintegrityorg/cai-research. asp

Chronicle of Higher Education. (1998). Almanac. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Cole, B. C., & Smith, D. L. (1995). Effects of ethics instruction on the ethical perceptions of college business students. Journal of Education for Business, 70(6), 351-356.

Cole, K. (1998, October 23). Engine makers tined $1 billion. The Detmit News, 75.

Daniel, L. G., Adams, B. N., & Smith, N. M . (1994). Academic misconduct among nursing students: A multivariate investigation. Journal

of Professional Nursing,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

10(5), 278-288.David, F. R., Anderson, L. M., & Lawrimore, K.

W. (1990). Perspectives on business ethics i n management education. SAM Advanced Man- agement Journal, 9.26-32.

Davis, L. (1987). Moral judgement development of graduate management students in two cul- tures: Minnesota and Singapore. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Deursch, C. H. (1988). Cheating: Alive and tlour- ishing. New York Times Educational Supple- ment, 131, 25-29.

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Clark, R. E., Williams, L. E., Francis, B., & Haines, V. I.

(1996). College cheating: Ten years later. Research in Higher Education, 37(4), 487-502. Duizend, J., & McCann, G. K. (1998). Do colle-

giate business students show a propensity to engage in illegal business practices? Journal qf

Business Ethics, 17, 229-238.

Etzioni, A. (1989). The moral dimension. New York: Free Press.

Fass, R. A. (1990). Cheating and plagiarism. In W. W. May (Ed.), Ethics and higher edudcation (pp. 170184. New York Macmillan.

Ferrell, C. M., & Daniel, L. G . (1995). A frame of reference for understanding behaviors related to

95-96.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

76 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessthe academic misconduct of undergraduate

teacher education students.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Research in HigherEducation, 36(3), 345-375.

Fishbein, L. (1994). We can curb college teaching. The Educatioan Digest, 59(7), 58-61,

Fishbein, M.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Ajzen,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I. (1975). Beliej attitude,intention and behavior: An introduction to the- ory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wes- ley.

Fitzpatrick, D. (1995). Insurance from theft. Fair- field County Business Journal. 34(20), 13. Franklyn-Stokes, A,, & Newstead, S. E. (1995).

Undergraduate cheating: Who does what and why? Studies i n Higher Education, 20(2),

Gellerman, G. W. (1986). Why “good” managers make bad ethical choices. Harvard Business Review, 86, 85-90.

Glenn, J. R.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Jr. (1992). Can a business and soci-ety course affect the ethical judgement of future

managers? Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Business Ethics, I1(3),217-223.

Glenn, J., & Loo, M. F. V. (1993). Business stu- dents’ and practitioners’ ethical decisions over time. Journal of Business Ethics, 12. 835-847. Gray, R. T. (1997, April). Clamping down on

worker crime. Nation’s Business, 4 4 4 5 . Haines, V. J., LaBeff, E. E., Clark, R. E., &

Diekhoff, G. M. (1986). Student cheating and perceived social control by college students. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 14( I), 13-16.

Harris, J. (1989). Ethical values and decision processes of male and female business students. Journal of Education for Business, 64(Febru- ary), 234-238.

Hilbert, G. A. (1988). Moral development andunethical behavior among students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 4(3), 163-167. Hollinger, R., & Clark, J. (1983). The3 by employ-

ees. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Homing, D. (1970). Blue collar theft New York

Wiley.

Hosmer, L. T. (1988). Adding ethics to the busi- ness curriculum. Business Horizons, 31,9-15. Jendrek, M. P. (1989). Faculty reactions to acade-

mic dishonesty. Journal of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

College StudentDevelopment, 30(September), 401406.

Jones, T. M., & Gautschi,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1. (1988). Will the ethicsof business change’? Journal of Business Ethics, 7, 231-248.

Kumar, K., Borycki, C., Nonis, S. A,, & Yauger, C. (1991). The strategic decision framework: Effect on students’ business ethics. Journal of Education for Business, 67(2), 74-79. May, K. M., & Loyd, B. H. (1 993). Academic dis-

honesty: The honor system and students’ atti-

tudes. Journal of college student development,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

34(2), 125-139.

McCabe. D. L. (1993). Faculty responses to acad- emic dishonesty: The influence of student honor codes. Human Sciences, 9,647-658. McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1993). Acade-

159-172.

mic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contex- tual influences. Journal of Higher Education,

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1996). What we know about cheating in college. Change(Janu- arymebruary), 29-33.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individ- ual and contextual influences on academic dis- honesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38(3), 379-396. McCormick, R. C. (1997). Reviewing business

theft and fidelity exposures. Rough Notes, 140, 42, 80.

McLoughlin, M. (1987, February 23). A nation of liars. U.S. News and World Report, 54-60. Meyer, H. (1994). Corns in the crow. Insights.

Retrieved October 28,1998, from www.insights-inc.com/articles/crows.html Nazario, S. L. (1992, September 1 I). Right and

wrong: Teaching values makes a comeback as schools see a need to fill a moral vacuum. The Wall Street Journal, B6.

Nonis, S . , & Swift. C. 0. (1998). Deterring cheat- ing behavior in the marketing classroom: An analysis of the effects of demographics, atti- tudes and in-class deterrent strategies. Journal of Marketing Education, 20(3), 188-199. Nowell, C.. & Laufer, D. (1997). Undergraduate

student cheating in the fields of business and economics. The Journal of Economic Educa- tion, 28(1), 3-12.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ogilby, S. M. (1995). The ethics of academic behavior: Will it affect professional behavior? Journal of Education f o r Business, 71(2),

Payne, S . L., & Pettingill, B. (1983). Theft per- ceptions. Personnel Administrator, October,

102-111.

Rittman, A. L. (1996, Fall). Academic dishonesty among college students. Missouri Western State College. Retrieved October 22,1998, from

www.psych.mwsc.edu/research/psy302/fall96/

andi-rittmaahtml

Roderick, J. C., Jelley, H. M.. Coiok, J. R., &

Forcht, K. A. (1991). The issue of white collar crime for collegiate schools of business. Journal of Education f o r Business, 66(5),

Roig, M., & Ballew, C. (1994). Attitudes toward cheating of self and others by college students and professors. The Psychological Record,

&(I), 3-12.

Rost, D., & Wild, K. P. (1994). Cheating and achievement-avoidance at school: Components and assessment. British Journal of Educational

Roth, N. L., & McCabe, D. L. (1995). Communi- cation strategies for addressing academic dis- honesty. Journal of College Student Develop- ment, 36(6), 531-539.

Saunders, E. J . (1993). Confronting academic dis- 64(5), 522-538.

92-96.

287-290.

PSychology, 64, 119-132.

honesty. Journal of Social Work Education, 2Y(2), 224- 231.

Sauser, J. (1990). The ethics of teaching business:

Toward a code for business professors. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 9 , 33-37. Scheers, N. J., & Dayton, C. M. (1987). Improved

estimation of academic cheating behavior: Using randomized response technique. Research in Higher Education. 2 6 , 6 1 4 9 . Schulman, M. ( 1 998). Cheating themselves.

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. Retrieved October 26, 1999, from http://scuish.scu.edu?Ethics/publications/lie/v9 n l/cheating.html

Sims, R. L. (1993). The relationship between aca- demic dishonesty and unethical business prac- tices. Journal of Education for Business, 68(4),

Singhal, A. C. (1982). Factors in students’ dishon- esty: What are institutions of higher education doing and not doing? NASPA Journal, 92-101. Stevens, G. E., & Stevens, F. W. (1987). Ethical

inclinations of tomorrow’s managers revisited: How and why students cheat. Journal of Edu- cation for Business 63(2), 24-29.

Stevens, R. E., Hams, 0. J., & Williamson, S . (1993). A comparison of ethical evaluations of business school faculty and students: A pilot

study. Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Business Ethics, 12(8),61 1-620.

Stevens, R. E., Harris, 0. J., & Williamson, S.

(1994). Evaluations of ethical situations by uni- versity faculty: A comparative study. Journal of Education,for Business, 69(3), 145-148. Swift, C. O., & Nonis, S. (1998). When no one is

watching: Cheating behavior on projects and assignments. Marketing Educution Review,

Terpstra, D. E., RozeU, E. J., & Robinson, R. K.

(1993). The influence of personality and demo- graphic variables on ethical decisions related to insider trading. The Journal of Ps,ychology, 127(4), 375- 389.

Todd-Mancillas, W. R. (1987). Academic dishon- esty among communication students and pro- fessionals: Some consequences and what might be done about them Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association, Boston.

Tom, G., & Borin, N. (1988). Cheating in acad- eme. Journal of Education, January, 153-157. Trendwatch. (1 998, June). Industry trends- Employee theft among retailers. Retrieved October 28, 1998, from http:// www.nations-

bank.com/smallbiz/archives/June98/ind-trends

.htm

U.S. Mutual Association (USMA). (1998). The cost of employee dishonesty. Retrieved June 2.

1999, from www.usmutual.com/cost.html Wood, J. A,, & Longenecker, J. G. ( 1988). Ethical

attitudes of students and business professionals: A study of moral reasoning. Journal of Busi- ness Ethics, 7, 249-257.

207-2 I 1.

8( I), 27-38.