BACK-VOWEL LENGTHENING PROCESS

IN AMERICAN-ENGLISH PRONUNCIATION

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

WAHYU ADI PUTRA GINTING

Student Number: 034214122ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

An “A” is not a purpose.

It’s an effect.

(

Wahyu Ginting

)

You will never be able to think about the

earth when you are still preoccupied by a

chrysanthemum called PARADISE.

(Wahyu Ginting)

That is the trap of a scientific research. One interesting thing will

carry you away to many other interesting things. What you have to

do is to insist on your original topic despite other interesting enticing

ones.

(Dr. Fr. B. Alip M. Pd. M. A.)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, let me express my highest gratitude to God the Almighty for all of the invisible but touchable guidance and for all blessings during the years I spent in finishing my study. I also would like to thank my sponsor, Dr. Fr. B. Alip M. Pd. M. A., for all of the corrections, suggestions, challenges, cautions, and guidance which had been helping me in the process of writing my thesis. I would like to thank my co-sponsor, Dra. B. Ria Lestari M. S., for performing a precise correction to my written report. I thank M. Luluk Artika W., S. S., my thesis examiner, for her questions and appreciation helpful for my thesis.

My best gratitude also goes to Mr. Paul Boersma and Mr. David Weenink who have intelligently established such a complete, accurate, and easy-to-utilize program of conducting the analysis of acoustic phonetics as Praat program. Thank you for letting all people around the world download your masterpiece freely from www.praat.org.

I thank also Mas Ernest for giving me a short practical course in understanding how to use SPSS for my statistical calculation. You saved me from the trap of those frustrating manual numeric statistical formulations.

Particularly, I would like to thank Budi Permana and Eston Wesley, who kindheartedly showed me how to re-record the data using Cool Edit Pro. 2. You two had been a big help for me and my thesis. I would never forget the help given by my brother and sister, Lae Palmer and Ito Novita Debora, who had lent me a copy of Longman Dictionary of American English, the source of my data, when mine was broken into pieces. You came at the right time.

Ni Ketut Herni Prabawathi (Adhek) and Mei Ratri Sri Handayani deserve my best gratitude since they had voluntarily combed all over the city of Yogyakarta to search a new copy of Longman Dictionary of American English to replace my broken one. Though unsuccessful, your effort had truly inspired me.

thank Mbak Nik who had been so patient serving me with helpful answers for all my questions about the administrative procedures when writing this thesis. All of the lectures of the Department of English Letters of Sanata Dharma University deserve my thankful expression since they have always been one of my best sources of knowledge from the time I got myself involved in this institution. Thanks to the library of Sanata Dharma University and the library of Gajah Mada University for the books which helped me find the appropriate theories.

I thank friends in Sastra Mungil, the community where I started my real social life. The desired people in A Streetcar Named Desire also deserve my best desired

gratitude. Pals in Media Sastra, by providing a vast space of discussion, had indirectly assisted me in doing my thesis. I thank you people for that.

I would like to express a gigantic gratitude to a woman with whom I have been experiencing many varieties of emotion, Desy “Ringgi” Pramusiwi. You have been the unpredictably twisted waving acoustics of one long chapter of my life.

Lastly, I give my gratitude and affection to my parents: Jamal Ginting and Yusmiati Sembiring, brother: Tri Aginta Ginting, and sisters: Silva Astari Ginting and Aprilla Malriati Ginting, to whom this thesis is dedicated.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE ……… i

APPROVAL PAGE ……… ii

ACCEPTANCE PAGE ……… iii

MOTTO PAGE ……… iv

Lembar Pernyataan Persetujuan Publikasi Karya Ilmiah ……….. v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ……… vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ……… viii

ABSTRACT ……… xi

ABSTRAK ……… xii

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ……… 1

A. Background of the Study ……… 1

B. Problem Formulation ……… 5

C. Objectives of the Study ……… 5

D. Definition of Terms ……… 5

CHAPTER II: THEORETICAL REVIEW……….. 7

A. Review of Related Studies………... 8

B. Review of Related Theories……….. 13

B.1. Articulatory Phonetics……… 13

B.1.a. Speech Sounds Production ………. 13

B.1.b. The Nature of Speech Sounds ……… 15

B.1.c. The Back Vowels of American-English …………. 18

B.1.d. The Stop Consonants of American-English ……... 22

B.2. Acoustic Phonetics …………..………... 25

B.2.a. Sound Waves ……….. 25

B.2.b. Pitch and Frequency ……… 28

B.2.c. Loudness and Intensity ……… 29

B.2.d. Spectrographic Analysis ………. 30

B.3. Vowel Lengthening Process ……….. 32

B.3.a. A Controversial Debate ……….. 32

B.3.b. The Nature of Vowel Length ………. 33

B.4. Phonological Processes ………...……….. 35

B.4.a. Interaction among Sounds ……….. 35

B.4.b. Syllable Structure ………... 37

C. Theoretical Framework ……… 39

D. Hypothesis ……… 40

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY……… 41

A. Object of the Study………. 41

B.3. Longman Dictionary of American English ……… 44

B.4. The Ideal Data ……… 47

C. Method of the Study……….. 50

C.1. An Empirical Research……… 50

C.2. Data Collection ……… 51

C.3. Statistical Data Analysis ……… 56

C.3.1. The T-Test ……….. 56

D. Null Hypothesis ……….. 60

CHAPTER IV: ANALYSIS………. 62

A. The Influence of Voiced and Voiceless Stop Consonants on the Length of the Preceding Back Vowel ……… 62

A.1. High Back Lax Rounded Vowel ……..……… 63

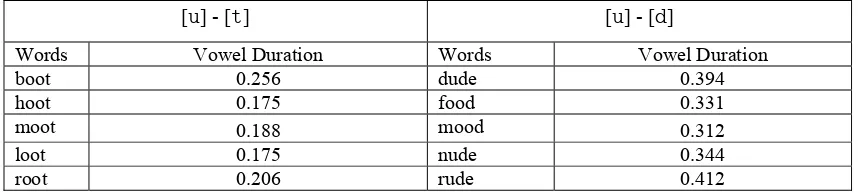

A.1.a. [][t]-[][d] ……… 64

A.2. High Back Tense Rounded Vowel ……….. 68

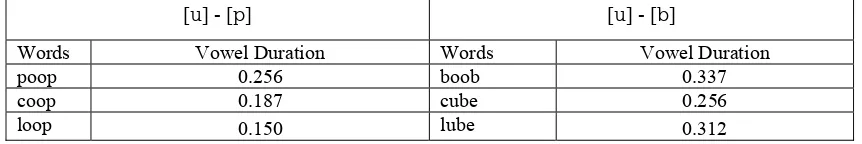

A.2.a. [u][p]-[u][b]………. 68

A.2.b. [u][t]-[u][d]………. 72

A.3. Mid Back Lax Rounded Vowel ………... 75

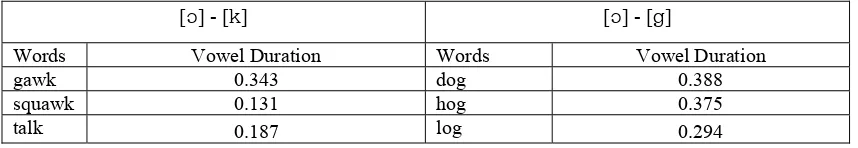

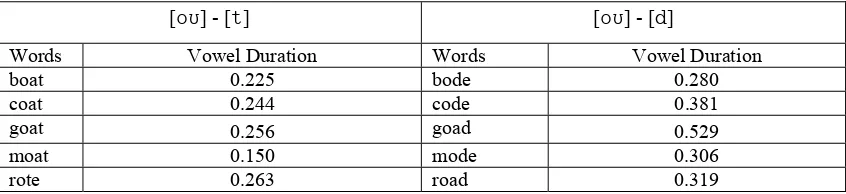

A.3.a. [][k]-[][]………. 76

A.3.b. [][t]-[][d]………. 79

A.4. Mid Back Tense Rounded Vowel ……… 82

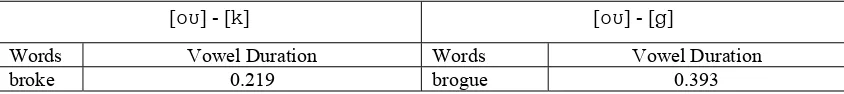

A.4.a. [o][k]-[o][]……… 83

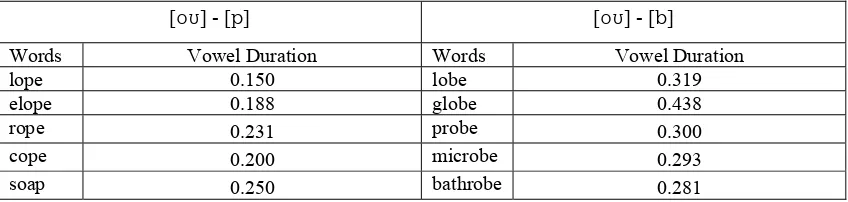

A.4.b. [o][p]-[o][b]……… 85

A.4.c. [o][t]-[o][d]……… 88

A.5. Low Back Tense Unrounded Vowel ………... 91

A.5.a. [][k]-[][]……… 92

A.5.b. [][p]-[][b]……… 95

A.5.c. [][t]-[][d]……… 98

A.6. Statistical Conclusion ………. 101

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION …….……….. 102

A. Concluding Remark ..…….……… 102

B. Suggestions ……… 105

BIBLIOGRAPHY ……….……… 107

APPENDICES ……… 109

App. I. The Result of the T-Test ……… 109

App.I.A. T-Test of [][t] - [][d] ……… 110

App.I.C. T-Test of [u][t] - [u][d] ……… 112

App.I.D. T-Test of [][k] - [][] ……… 113

App.I.E. T-Test of [][t] - [][d] ……… 114

App. I.F. T-Test of [o][p] - [o][b]……… 115

App.I.G. T-Test of [o][t] - [o][d] ……… 116

App.I.H. T-Test of [][k] - [][] ……… 117

App.I.I. T-Test of [][p] - [][b] ………. 118

App.I.J. T-Test of [][t] - [][d] ………. 119

App. II. The Spectrographic Analyses of the Attachment of Back-Vowels to Voiceless and Voiced Stop Consonants ……….. 120

App.II.A. The Attachment of Back-Vowels to Voiceless Stop Consonants ……… 121

App.II.A.1. []-[t]………. 122

App.II.A.2. [u]-[p]……….. 136

App.II.A.3. [u]-[t]……….. 145

App.II.A.4. []-[k]……….. 160

App.II.A.5. []-[t]……….. 169

App.II.A.6. [o]-[k]……… 181

App.II.A.7. [o]-[p]……… 184

App.II.A.8. [o]-[t]……… 199

App.II.A.9. []-[k]……….. 214

App.II.A.10. []-[p]……… 229

App.II.A.11. []-[t]……… 244

App.II.B. The Attachment of Back-Vowels to Voiced Stop Consonants ………. 259

App.II.B.1. []-[d]………. 259

App.II.B.2. [u]-[b]……….. 274

App.II.B.3. [u]-[d]……….. 283

App.II.B.4. []-[]……….. 298

App.II.B.5. []-[d]……….. 307

App.II.B.6. [o]-[]……… 319

App.II.B.7. [o]-[b]……… 322

App.II.B.8. [o]-[d]……… 337

App.II.B.9. []-[]……….. 352

ABSTRACT

WAHYU ADI PUTRA GINTING. Back Vowel Lengthening Process in American-English Pronunciation. Yogyakarta: Department of American-English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma University, 2008.

As a means of human communication which uses speech sounds as its main message-transferring media, language cannot be separated from its dependency on discourses discussing about human’s speech sounds. Phonetics and phonology are two branches of linguistics – the scientific study of language – undergoing discussions about sounds. Moreover, those two discourses will help non-native speakers improve their ability to utter a correct pronunciation upon, in this case, English words. The importance of speech-sounds is what stimulates the present researcher to analyze a particular topic involving sounds as its focus of discussion.

This research is done under the awareness of continuing a previous study conducted by Kartika Kirana, a graduate of English Letters Department of the Faculty of Letters of Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta. Her thesis, entitled The Influence of Voiced and Voiceless Stop Consonants and Their Place of Articulations on the Length of the Preceding Front Vowel in American English Pronunciation, has inspired the present researcher to extend the scope of the object of the study: from

front vowels to back vowels. Though, the influence of the places of articulation of the stops on the length of the preceding vowel is not discussed since the data being utilized in this present study are not applicable to the analysis of that particular theoretical issue.

In this study the present researcher focuses his observation on the American-English pronunciation. More specifically, the nucleus of the analysis is on the process of vowel lengthening, particularly English back-vowels. This research bases its concept of thinking on the theory suggested by O’Grady saying that “English vowels are long when followed by a voiced obstruent consonant in the same syllable” (1997: 107). Therefore, this study is aimed to figure out how voiced and voiceless stop consonants influence the duration of the preceding back vowels’ lengthening.

ABSTRAK

WAHYU ADI PUTRA GINTING. Back Vowel Lengthening Process in American-English Pronunciation. Yogyakarta: Jurusan Sastra Inggris, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sanata Dharma, 2007.

Sebagai alat komunikasi manusia yang menggunakan bunyi sebagai media utama penyampaian pesan, bahasa tidak dapat dipisahkan dari ketergantungannya terhadap wacana-wacana yang membahas tentang bunyi kata. Fonetik dan fonologi adalah dua cabang linguistik – kajian ilmiah yang mempelajari bahasa – yang membahas tentang bunyi. Lebih lagi, kedua diskursus ini dapat membantu penutur tidak asli mengembangkan kemampuan mereka melafalkan kata-kata, dalam hal ini, bahasa Inggris. Pentingnya penggunaan bunyi dalam bahasa inilah yang membuat penulis tertarik untuk meneliti topik yang melibatkan bunyi sebagai fokus diskusinya. Penelitian ini dilakukan sebagai usaha melanjutkan penelitian pendahulunya, yang dikerjakan oleh Kartika Kirana, seorang mahasiswi Jurusan Sastra Inggris Fakultas Sastra Universitas Sanata Dharma, Yogyakarta. Skripsinya, yang diberi judul The Influence of Voiced and Voiceless Stop Consonants and Their Place of Articulations of the Length of the Preceding Front Vowel in American English Pronunciation, telah mengilhami peneliti untuk melanjutkan lingkup objek penelitiannya: dari vokal depan ke vokal belakang. Namun, pengaruh dari perbedaan tempat pelafalan dari konsonan henti pada panjang vokal belakang tidak dibahas karena data yang digunakan di penelitian ini tidak memungkinkan dilakukannya analisis terhadap isu teoretis itu.

Dalam penelitian ini, penulis memusatkan penelitiannya pada pelafalan bahasa Inggris-Amerika. Lebih spesifik lagi, inti dari analisis penelitian ini adalah proses pemanjangan bunyi suara vokal, dalam hal ini vokal belakang dalam bahasa Inggris. Penelitian ini mendasarkan konsep pemikirannya pada teori yang dirumuskan oleh O’Grady yang mengatakan bahwa “Bunyi vokal dalam bahasa Inggris akan menjadi panjang ketika diikuti oleh bunyi konsonan bervibra dalam suku kata yang sama” (1997: 107). Maka dari itu, penelitian ini ditujukan untuk mengetahui bagaimana konsonan henti-getar dan konsonan henti-tak-getar mempengaruhi durasi dari panjang pelafalan bunyi vokal belakang yang mendahuluinya.

Metode yang diterapkan dalam penelitian ini adalah usaha memperoleh durasi dari vokal belakang ketika dilekatkan dengan konsonan henti-getar atau konsonan

berupa perangkat-lunak audio Realtek AC 97. Sementara itu, instrumen yang digunakan untuk mendapatkan tampilan spektrografik dari setiap datum adalah program Praat yang digunduh dari situs internet www.praat.org. Setelah mendapatkan durasi bunyi vokal untuk setiap kata yang digunakan, uji-t digunakan untuk menganalis durasi tersebut.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

A. Background of the Study

Language, as a means of human communication, can be scientifically analyzed into five kinds of prominent partitions, namely: phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics. The first part, phonetics, is the lowest layer of a language analysis. It studies the most common utility of producing utterances in human communication: sounds. Meanwhile, the other four are more developed language discussions. They are described as the bread and butter of the study of language due to their function as linguistic phases which form the phonemic structure of particular tongues (Aitchison, 1978: 17).

Two out of five linguistic studies, phonetics and phonology, share the same ingredient of specified discussion: sounds. While phonetics discusses “the speech sounds that are utilized by all human languages to represent meanings”, phonology grounds its focus on the way sounds construct a kind of conventional “system and pattern of human language” (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988: 31, 70). Moreover, intensifying the distinction between phonetics and phonology, the focus of phonetics is on “acoustics and articulations”, while phonology aims its focus on “the system and structure of speech” (Clark and Yallop, 1990: 4).

linguistically significant in a particular language” (Wolfram and Johnson, 1982: 5). Sounds, being “linguistically significant”, are understood as having distinctive (read: phonemic) characteristics, which make the existence of those certain sounds significant, and, therefore, prominent in a “particular language”. Scrutinizing more in the noun phrase “particular language”, one should be brought to a comprehension that not all languages occupy the same sounds, and also sound-patterns, as their means of message-transferring. Simply saying, there are several specific sounds which will honestly separate English from French, for example. Interestingly, this fundamental phenomenon does not only happen in the discussion of the external relationship of a particular language (the relationship between English and French is one of the examples of an external relationship of a language), but also in the internal one, meaning that the relationship of a particular language with its own variants. English is one of those languages experiencing this particular phenomenon.

The fact that different languages should consist of different sounds contributes difficulties for people who intend to learn a foreign language. The constraints will particularly be on the matter of pronunciation. This is true realizing that there are sounds in English which do not exist in some other languages and vice versa. This fact results in another fact that people, since they are frustrated by those sounds that do not fit their tongue, tend to choose to replace those unfamiliar sounds their own local sounds which share similar (but exactly not the same) distinctive features with those in foreign sounds. For example, many Indonesians pronounce English /ri/into simply /tri/because the sound // does not exist in Indonesian

language.

Still related to the problem of difficulties in pronunciation, the individual factors can not be neglected since those factors contribute significant influences in pronouncing sounds correctly. Not only on the regional social dialect do the exact settings of the larynx that can be regarded as producing “normal voice” depend, but also on the individual factors (Laver, 1968, as cited in Clark and Yallop, 1990: 61). The case mentioned in the previous paragraph is simply a matter of the individual’s tendency to use his/her local sounds.

they are asked to pronounce sounds in the form of a word. Ordinarily, the problem occurs because they do not recognize the phonological effects created by a certain sound to the sounds preceding or following it. In English pronunciation, being more specific, the same phenomenon occurs in a sound string in which a final voiced or voiceless consonant influences the preceding sounds. Related to the topic of this research, the preceding sounds that are to be analyzed are vowels. It has widely been known that a vowel is more likely to be lengthened whenever it precedes a voiced consonant. Though, some phoneticians doubt this phenomenon’s phonemic quality. This particular issue is what interests the present researcher.

This research is a continuation of a former research conducted by Kartika Kirana, a graduate of English Letters Department of Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta. The research was done in the year of 2003, and was reported in the form of an Undergraduate Thesis which had been defended in the same year. Kirana utilized English front vowels /, æ, , e, i/ as the preceding sounds that were to be analyzed in her research. Meanwhile, the consonants occupied were the stop consonants/p, t, k, b, d, /. The specific focus of her research was to analyze the phonological process of vowel lengthening as a result of the influence of the voiced or voiceless consonant following it.

the phonetic alphabets will be presented in the American English version, which are

/, u, , o, / (taken from Longman Dictionary of American English). In addition

to that, stop consonants are still used to be analyzed as the sounds following the back vowels. This writing is to prove the practical theory saying that, ordinarily, a vowel will be lengthened whenever it is followed by a voiced consonant. In relation to the speakers’ competence in acknowledging English, Gordon and Wong assert that if this phonological phenomenon is not done, it will create a non-English rhythm which leads us to recognize the speaker’s incompetence mastering English (1961: 14). B. Problem Formulation

In this research, there is one problem to answer. That particular problem is: 1. How do the voiced stop consonants and the voiceless ones influence the

length of the preceding back vowels in American English pronunciation? C. Objective of the Study

Referring to the problems formulated above, this study is obviously conducted to discover how voiced and voiceless stop consonants influence the duration of the preceding back vowels’ lengthening.

D. Definition of Terms

those specific technical terms. Thence, the present researcher provides their definitions, which are taken from some reliable sources, as described below:

1. Stop consonants are consonants that are made with a complete and momentary closure of airflow through the oral cavity, for example: [p] and

[b] (O’Grady, Drobrovolsky, and Aranoff, 1989: 21).

2. Back vowels are vowels that are produced with lip rounding, for example:

[u] and [] (Wolfram and Johnson, 1982: 30), except [], whose

pronunciation does not involve active labial movement (Prator, 1951: 100). 3. Voiced sounds are sounds which are pronounced with vibration of the vocal

cords, for example: [] and [d] (Jones, 1969: 544).

4. Voiceless sounds are sounds which are pronounced without vibration of the vocal cords, for example: [s] and [f] (Jones, 1969: 544).

CHAPTER II

REVIEW ON LITERATURE

This chapter will be divided into four major parts, namely: review on related studies, review on related theories, theoretical framework, and hypotheses. A short description about those four divisions will be depicted in the rest three of these introductory paragraphs.

The first sub-chapter – review on related studies – is to review one previous study conducted by Kartika Kirana, the study which inspires this present one. The review covers a brief discussion about the topic, the problem formulations, the object of the study, the method of conducting the study, problematic findings figured out in the analysis, the conclusion made, and how the study is different from the present one.

A review on related theories will be loaded in the second sub-chapter. There are four partitions in this sub-chapter. They are articulatory phonetics, acoustic phonetics, vowel lengthening process, and phonological processes. Each of them will still be re-divided into several smaller units. These partitions are meant to classify each theory into their practical quality. Some of the theories are used to describe the object of the study and some others are utilized as the tools in analyzing the data.

steps done in analyzing the data. Meanwhile, the hypotheses part consists of tentative answers for the research’s problems.

A. Review on Related Studies

As already mentioned in the first chapter of this report, the present researcher conducts this study based on the awareness of continuing the previous study done by Kartika Kirana in the year of 2003. Therefore, a brief review will be committed on the research report written by Kirana. This review is done to give a clearer basic knowledge of what has been done by the former researcher. By having the description of the former study, the present researcher can emphasize his area of study – to ensure readers that there are distinctions isolating the topic of the present research from the previous one.

The title of the former research’s report is The Influence of Voiced and Voiceless Stop Consonants and Their Place of Articulations on the Length of the

Preceding Front Vowel in American-English Pronunciation. This research was conducted by Kartika Kirana – a student of English Letters Department of Sanata Dharma University Yogyakarta – and was approved and successfully defended in the year of 2003.

prove the theory, Kirana held a field research using American English native-speakers as her respondents. She was also eager to find out whether the places of articulation of the stop consonants will contribute influences to the vowel lengthening process or not. For the latter, she based her thought on the theory asserted by Clark and Yallop saying that “if a consonant involves tongue movement, more time will be needed to establish the consonantal articulation, and the adjacent vowel will be longer. Thus, vowels are likely to be longer before alveolars or velars than before bilabials, for example” (1990: 72).

Kirana formulated two problems for her research, namely:

1. How do the voiced and voiceless stop consonants influence the length of the preceding front vowel?

2. How do the different places of articulation of the stop consonants influence the length of the preceding front vowel?

These problems were answered by working on the data of the research: recordings of strings pronounced by the respondents of the research. Obviously, the sound-strings utilized in the study were those which contained the phonologically-patterned-arrangements of [p], [t], [k], [b], [d], [] (voiced and voiceless stop consonants) and [], [i], [æ], [], [e] (front vowels).

diagram showing the display of the sounds is called spectrogram. Later on, the collected data would be observed further using the Praat program. This analysis was aimed to measure the duration of time needed by the speaker in pronouncing a sequence of sounds. Finally, the data of the observation results would be tested statistically using the T-test and Friedman test.

The samples used as the source of the data were four American native-speakers: two of them were males and the other two were females. Though, Kirana did not try to enhance her research into a broader analysis, for example: the implication of sex-difference to the research’s findings.

The phonemic-sound-sequences were gathered from dictionaries, and then administered to the respondents in order to be pronounced. The recording activity was done during the act of pronouncing the sounds. The recording was then transferred into the computer to be analyzed.

not indicate the influence of different places of articulation of the stop consonants to the front vowel lengthening process.

The present researcher will use the same analytic method of research as Kirana did. The spectrographic analysis is still going to be used. The data will also be analyzed in a computerized checking system using Praat program. Statistical analysis is going to be used as well. The T-test will show the result of the data analysis answering the problem formulated. However, besides the different source of the data being used, the very basic distinctive element that differentiates the present researcher’s study to Kirana’s is the preceding vowels to be analyzed. The present researcher decides to use English back vowels, /, u, , o, /, as the sound unit experiencing the phonological phenomenon – the vowel lengthening process as the effect of regressive assimilation of the following stop consonants.

B. Review on Related Theories

The related theories reviewed in this sub-chapter will be divided into four divisions according to their practical quality. Some theories are used as a means to describe the subject matter of the research. Such theories are loaded in the “Articulatory Phonetics” sub-chapter. Another sub-chaptering is done to load the theories describing the technical process of the spectrographic analysis. That particular sub-chapter is entitled “Acoustic Phonetics”. A specified sub-chaptering will be given to the theories of vowel lengthening processes since they are the nucleic discussion of the study. The theories are presented in the “Vowel Lengthening Processes” sub-chapter. Meanwhile, some other theories are presented as the practical ones to apply in the process of analyzing the data. Those theories are collected and, then, presented in the “Phonological Processes” sub-chapter. This is done in the awareness of being structurally systematic in putting the theories in a properly ordered turn. Each descriptive theory will be clustered into one sub-chapter, and the same thing will also be done to the practical ones.

B.1. Articulatory Phonetics

B.1.a. Speech Sounds Production

the continuous flow of speech to what we regard as isolated sounds; it is helpful to examine exactly how sounds are produced” (1982: 12). The following paragraphs are to describe the production of sounds.

In accordance with the need of communication, some parts of humans’ biological organ structure are designed to accomplish the production of speech sounds – since sounds are the most common means used for human communication. A simultaneous activity is done by a group of anatomical organs that collaborate to produce speech sounds. However, none of those anatomical organs is designed exclusively to produce speech sounds. It means that there are other original biological functions possessed by those organs, for instance, nose and mouth are meant to inhale and exhale the air. Meanwhile, producing speech sounds is a kind of “minor function” because those organs should be combined when producing sounds – they cannot be used to produce speech sounds when being individual, for example, we will not be able to produce the fricative sound articulated in the palatoalveolar area [] by counting on the use of lungs alone. There is a collaboration of tongue, palate, glottal, velum, and lungs which activate their own auxiliary activity so that the sound can be articulated.

1. The respiratory system, whose parts are the lungs, the bronchial tubes, the trachea, diaphragm, and various muscles whose function is to help move the air through the system.

2. The larynx, whose ability is to provide voice for speech sounds. Larynx also provides an additional function, which is to give protection to the lungs by “sealing them off” when the sounds production process is being done.

3. The articulatory system (vocal tract), which includes the lips, teeth, tongue, and other parts of the mouth.

B.1.b The Nature of Speech Sounds

In English, all sounds are produced by pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism. The sounds are produced by using the air that comes from the lungs, so it is called pulmonic. The process of creating sounds in human communication is mostly done by pushing the air from the lungs out of the body through mouth and nose. To produce phonemic sounds by inhaling the air from outside of the body into the lungs is practically a difficult, tiring activity. This is what makes the egressive manner produce speech sounds (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988: 34).

a voiceless sound is uttered, there will not be any vibration that can be felt from the vocal folds. The voiced sounds are produced “when the vocal folds are brought close together, but not tightly closed, air passing between them causes them to vibrate…” (O’Grady et al, 1997: 22). There will be vibration that can be felt from the vocal folds when examining a voiced sound. A whisper will be produced when the vocal folds are “adjusted so that the anterior (front) portions are pulled close together, while the posterior (back) portions are apart (O’Grady et al, 1997: 23). This position of the vocal folds results in the voicelessness of a whisper. A murmur, or whispery voices, in terms of the glottal configuration, is produced quite similarly with the process of producing a voiced sound. Yet, though the sound is voiced, the vocal folds are more relaxed to “allow enough air to escape to produce a simultaneous whispery effect” (O’Grady et al, 1997: 23).

pass through the nasal cavity. This happens when sounds like [m], [n], [] are pronounced (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988: 37).

Another condition that can differentiate the sound and the quality of the sound produced is the shape of the mouth. Inside the oral cavity (the mouth), there are several speech organs supporting each other to produce speech sounds. They are lips, tongue, teeth, palates, and jaws. Lips are the last part of the oral cavity that can be used to produce different sounds. Two basic treatments can be done to shape different lips positions, namely to shut and to hold apart. Shutting the lips will prevent the air-stream from escaping at all. The sounds produced by this treatment can be found in the initial sounds of post and boast. Alternatively, by lowering the soft palate, the air-stream can be directed to the nose like in the initial sound of moose. Meanwhile, when the treatment done to the lips is to hold them apart, there will be six positions shaped. They may be held sufficiently close together over all their length that friction occurs between them, held so sufficiently far apart so no friction to be heard (spread position), held in a relaxed position with a medium lowering of the lower jaw (neutral position), held relatively wide apart, without any marked rounding (open position), or held wide apart but with slight projection and rounding (open rounding position) (Indriani, 2001: 4)

airflow. Alveolar ridge and the velum are with which the tongue experiences a full contact creating a complete obstruction blocking the airflow. The tongue itself has three parts. They are the front part which “lies opposite the hard palate”, the back part which “faces the soft palate”, and the centre part “where the front and back meet” (Indriani, 2001: 5). Specifically for the pronunciation of vowels, those parts will distinguish the vocalic sounds produced. The sounds formed by the involvement of the front part of the tongue will clearly be different from the ones formed by the involvement of the back or centre part.

B.1.c The Back Vowels of American English

“Vowels are sonorous, syllabic sounds made with the vocal tract more open than it is for consonant and glide articulations” (O’Grady, Drobrovolsky, Aronoff, 1989: 26). Vowels’ being sonorant means that they are pronounced louder in terms of the volume of the voice. Vowels can also be pronounced longer since there is no blockage from the other speech organs, as the theory says that “while consonants are typically produced with some sort of constriction or stoppage in the oral cavity, vowels are produced without radical constriction” (Wolfram, 1982: 27).

part of the body of the tongue on a horizontal scale” (1982: 27). It means that, being oppositional with the status of the vertically highest part of the tongue body, a vowel can be classified into three positions, namely front, central, and back.

Supporting the height and backness dimensions, another point can be added to help describe the articulatory processes of different vowels. The dimension meant is tenseness. Vowel tenseness is defined as “the degree to which the root of the tongue is pulled forward and bunched up” (Wolfram, 1982: 28). According to the tenseness status, vowels can be stratified into two statuses: tense and lax. Tense vowels are produced “with a greater degree of construction of the tongue body or tongue root than are certain other vowels” (O’Grady et al., 1989: 29). Comprehensively, there will be a kind of motion experienced by the tongue when a certain vowel is pronounced. Lax vowels are made “with roughly the same tongue position but with a less constricted articulation” (O’Grady et al., 1989: 29). It means that the tongue will be more relaxed when a lax vowel is sounded. Tense and lax vowels tend to correlate with the tongue height status because the vertical position of the tongue will influence the tenseness status of a vowel. For example, the vowel sounds in beat[bit] (tense) compared with the one in bit[bt] (lax).

(rounded) compared with pit (unrounded).Thus, all English back vowels are rounded except the low, back, lax vowel [] as in hot (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988: 50).

Back vowels are vowels that are produced with lip rounding (Wolfram and Johnson, 1982: 30) except [] (Prator, 1951: 100). Five back vowels that exist in American-English are /, u, , o, / (Longman Dictionary of American English)

a) Low back tense unrounded vowel []

This vowel is sounded with a remarkable separation of the jaws. With “a slight muscular effort”, the lower jaw is moved down “more than it would be in a normal relaxed position.” As the result, the lips are forced to be wide open (i.e.

one inch across and one inch from top to bottom), and the consequence of this condition is the occurrence of the unrounded status. To a certain point, the tongue tip lightly reaches a spot on the floor of the mouth, “so low that in compensation the back of the tongue must be raised just a little in the throat” (Prator, 1951: 100).

b) Mid back lax rounded vowel []

remains in approximately the same position as for[], but is ‘bunched’ a little toward the back of the mouth” (Prator, 1951: 101).

c) Mid back tense rounded vowel [o]

This vowel is uttered by shaping the lips into the form of the alphabet o. It means that the lips need to be “protruded” and “rounded” more than that of []. The diameter of the lip-rounding for this vowel is about one inch. “The jaw has been raised still a little more, and the ‘bunching’ of the tongue in the back of the mouth is greater.” Moreover, there is a probability that the tongue tip does not touch the floor of the mouth anymore. One distinctive feature that belongs to the pronunciation of this particular vowel is that “it is frequently diphthongized.” For instance, in pronouncing words like boast and boat, in which the back vowel

[o] acts as the nucleus, “the complete vowel begins as a pure [o], and moves

on to a brief []” (Prator, 1951: 101).

d) High back lax rounded vowel []

e) High back tense rounded vowel [u]

The protrusion and the rounding of the lips, in the pronunciation of this vowel, should be in its maximum projection. The size of the opening’s diameter is about the size of a pencil. The visibility of the teeth is negative. “The tip of the tongue is drawn quite far and back and touches nothing, but the sides of the tongue press firmly for some distance along the upper tooth ridge” (Prator, 1951: 102-103). B.1.d The Stop Consonants of American English

Consonants, also known as consonantal sounds, are produced with a narrow or complete closure in the vocal tract. The airflow, started egressively from the lungs to the larynx, is blocked temporarily or resisted so much that there will be noise produced as the air flows past the constriction (O’Grady et al, 1989: 17).

et al., 1989: 20). Stop consonants are included in the category of manner of articulation.

Stop consonants are sounds that are experiencing a complete blockage (obstruction) for a brief period of time (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988, 40). Concerning about the durations of the stoppage, Clark and Yallop say that they are “partly conditioned by the phonetic context and are therefore variable: the stoppage itself may last for from 40 up to 50 ms, and the closure and release phases may each last for between 20 and 80 ms” (1990: 72). American English consonants, in relation with the manner of articulation, can be categorized into voiced and voiceless consonants. The consideration determining the voicing status of a sound is the existence of a vibration in the vocal cord when the sound is being pronounced. Those sounds which are included in English stop consonants are[p],[t],[k] which are voiceless, and

[b],[d],[] which are voiced.

a) Bilabial stops[p], [b]

b) Alveolar stops[t], [d]

In the process of pronouncing alveolar stops [t] and[d], the soft palate is raised and the uvula shuts off the nasal cavity. The main restriction to the air-stream is provided by the complete blockage constructed “between the tip and rims of the tongue and the upper alveolar ridge and side teeth”. The air pumped from the lungs is compressed behind this stoppage, and the vocal cords are wide apart for[t], yet, there will be vibration for all part of the compression stage for[d]. The shape of the lips will be influenced by the neighboring sounds, specifically the preceding vowel or semi-vowel, for example: widened lips for /t/ in tit, and rounded lips for /d/ in dude (Indriani, 2001: 17, examples are not included).

c) Velar stops[k], []

preceding vowel or semi-vowel, for example: widened lips for /k/ in cheek, and rounded lips for // in log (Indriani, 2001: 20, examples are not included). B.2. Acoustic Phonetics

The significance of the discussion of acoustic phonetics is that, by observing sounds acoustically, learners are able to describe sounds not only by stating how sounds are produced, as learnt in articulatory phonetics, but also by describing sounds in terms of what listeners can hear. Sometimes, learners who are interested in the study of sounds production meet problems in explaining why certain sounds are confused with one another and in specifying sounds that are difficult to describe in terms of articulatory movements, for example, vowels. This fact is true since, to face such problems, learners should go further to the study of the acoustic structure of sounds rather than being preoccupied by the analytic descriptive observation of how phonemic sounds are produced (Ladefoged, 1982: 165). The specific theories of acoustic phonetics will be described briefly in the next sub-titles. These theories are important remembering that the present researcher utilizes spectrographic analysis in his effort of figuring out the duration of each back vowel being studied.

B.2.a. Sound Waves

gas is that it can be “compressed” or “rarefied”. What to be “compressed” or “rarefied” means is that the component molecules can be brought closer together or further apart. This specific characteristic is what later is transcribed as an oscillated graphic. The following direct quotation from O’Connor’s Phonetics describes more clearly and more precisely how speech sound travels using air as it medium.

When we move our vocal organs in speech we disturb the air molecules nearest our mouth and thus displace them; they in turn displace other molecules in a similar way and so on in a chain reaction until the energy imparted by the vocal organs dies away at some distance from the speaker. When one molecule, as it were, collides with another it rebounds back to and beyond its starting point and continues to oscillate to and fro until eventually it stands still again. The sounds that we hear are closely related to the characteristic of oscillations or vibrations of the similar behavior in the next one in the chain we can confine our attention to the behavior of a single molecule (1973:71).

In observing a printed graphic of a sound wave, one must find some technical terms such as: amplitude, cycle, point of rest, frequency, and intensity. In this sub-title, the discussion of amplitude, cycle, and point of rest will be presented. Meanwhile, the discussion of frequency and intensity will be loaded in a different sub-title since it has a very close relation to other acoustic items called pitch and loudness. So, their discussion will be joined in one specific sub-title.

The description of the regular movement of the collided molecules, which is “rebounding back to and beyond its starting point”, is what so called as the amplitude. Clearly the activity of the sound wave can be understood as a vibration. In producing a vibration, obviously some energy is needed. Therefore, the amount of the energy will determine the width of molecule’s oscillation, as O’Connor states, “if the molecule is given a good strong bump it will travel further from its place of rest than if it were bumped only lightly”. Furthermore, “the maximum movement away from the place of rest,” he proceeds, “is the amplitude of vibration” (1973: 73).

In the context of the “point of rest”, from the explanation above, we might derive an understanding that point of rest means the exact point from which a molecule starts and ends its swinging. In its graphical display, a point of rest is often drawn as a horizontal line from which a line of amplitude starts going up until its highest peak, then going down crossing the point of rest to reach its lowest point, and going up again to meet the same point of rest.

place of rest to the maximum amplitude in one direction, then back to the maximum amplitude in the other direction and finally back to the place of rest again – is known, appropriately, as one cycle” (1973: 73). Therefore, a cycle can be understood as a complete up-and-down swing of a molecule.

B.2.b. Pitch and Frequency

Ladefoged defines frequency as “a technical term for and acoustic property of a sound – namely the number of complete repetitions (cycles) of variations in air pressure occurring in a second” (1982: 168). Therefore, by counting the amount of the complete cycles of the vibration, we may get the number of the frequency. Respectively, frequency is connected with the time measurement. The quotation from Ladefoged defines the time measurement in second. It means that the number of frequency is counted in a second length. “The unit of frequency measurement is the Hertz, usually abbreviated as Hz” (Ladefoged, 1982: 168). Therefore, if there are one hundred complete repetitions in one second, the frequency will be valued as 100 Hz.

B.2.c. Loudness and Intensity

“The intensity of a sound is the amount of energy being transmitted through the air at a particular point, say the ear-drum or at a microphone within range of the sound” (O’Connor, 1973: 81). The important phrase from the quotation above is “the amount of energy”. Energy is what makes all the activities of sound wave possible to happen. It starts from the amplitude created by the molecule. When the amplitude is suddenly doubled whereas the frequency stays the same, it means that what increases is the velocity of the swinging molecules. The increasing velocity, understandably to keep the frequency the same while the amplitude is doubled, respectively increases the amount of energy expended to enable this.

Ladefoged suggests that “the intensity is proportional to the average size, or amplitude, of the variations in air pressure” (1982: 169). This means that “if the amplitude of a sound is doubled, the intensity increase four times; if the amplitude is trebled the intensity will increase nine times”, and so on and so forth (O’Connor, 1973: 82). The unit utilized to measure the intensity is called decibels, abbreviated as dB (Ladefoged, 1982: 169).

Therefore, the discussion of loudness is more appropriate to be placed in auditory phonetics in which we learn and judge what we hear.

B.2.d. Spectrographic Analysis

“The only record that we can usually get of a speech event is a tape-recording” (Ladefoged, 1982: 165). What acoustic phoneticians usually utilize as their data to analyze sound wave is a recording of a speech event. The recording will be sensed by a set of special microphone, and then is read a device called Oscillomink, which displays the description of the sound in a form of ink-written oscillograph (1982: 167). This oscillograph is what is then transferred to a presentation of a spectrogram.

Paul Boersma, in his manual of Praat Program, defines spectrogram as a “spectral-temporal representation of the sound” (www.praat.org., Praat Program: Intro 3.1. Viewing a Spectrogram, 2003). There are a couple of directions presented in a spectrographic display: horizontal and vertical directions. The horizontal direction represents the time (therefore it is called “temporal”) and the vertical direction represents the frequency (therefore it is called “spectral”).

The wideband spectrogram provides the temporal detail of the signal, but cannot separate harmonics. Therefore, the usage also depends on what will be researched. Usually, the wideband spectrogram is more often used because people are usually more interested in the formants of the sound than its harmonics (Asher, 1994: 3075). Since this research is intended to find data of the time duration, then, the wideband spectrogram will be utilized due to the inability of the narrowband one to display the time.

Formant is one of the most prominent items to be observed in a spectrographic analysis. Formant is considered as the bank of energy, in which the energy used to produce a speech sound reaches its peak (O’Connor, 1973: 87). Formants are numbered vertically from low to high according to the amount of the frequency counted in cps unit (cycle per second). Normally, consonants have three formants (F1, F2, and F3). Though, usually, vowels have more than three formants (F4, F5, and more). However, the most fundamental formants that characterize sounds are the first three formants. Meanwhile, those higher formants “are more connected with identifying the voice quality of a particular speaker” and not to be needed in specifying certain sounds, for example: vowels.

In its spectrographic representation, formants are shown by the darkness of the horizontal mark (Ladefoged, 1982: 177). Moreover, Boersma intensifies that “darker parts of the spectrogram mean higher energy densities, lighter parts mean lower energy densities” (www.praat.org., Praat Program: Intro 3.1. Viewing a Spectrogram, 2003). Energy densities here, of course, mean the peak of energy: the formant.

In Praat Program, the maximum number of formants is limited up to five formants only. These formants are tied in one vertical frame, which means that in one frame we will have five formants at maximum.

B.3. Vowel Lengthening Process

B.3.a A Controversial Debate

The discussion about the prominence of length as a feature which is phonemically relevant to distinguish sounds actually still remains a “war of words” (read: a dispute). Some experts assert that length cannot be neglected in analyzing sounds, especially vowels, since, to a certain extent, it truly distinguishes phonemically some pairs of sounds, for instance: bean and bin. Though, some others confront that argument by proposing an idea that the importance of including length as a phonemic feature contrasting a minimum pair is not primary.

In the case of vowel, for instance, to contrast an almost similar pair such as

[] and[u], since the height and the backness dimension of the articulation are the

the tenseness. Therefore, [] will be [- tense] and [u] will be [+ tense]. Yet, it is also hard to deny that there is another feature contrasting the pair which is length since [u] is somewhat pronounced longer than[]. Therefore, [] will be [- tense, - long] and [u] will be [+ tense, + long].

Nonetheless, according to Gieberich, “one of these features is redundant on the abstract phonemic level.” (1992: 99). It means that one of them is not primary to be put in the binary feature distinguishing the pair. Furthermore, Gieberich asserts that the tenseness seems more likely to be a “more basic” and “phonemically relevant” to be the binary feature. Length loses its chance to grab the position occupied by tenseness because of its relativity, as Gieberich said: “it is at least difficult to give absolute definitions of ‘long’ and ‘short’ as it is to define tenseness in absolute terms” (1992: 100).

Up to now, it seems that the discussion of length loses its interest for it is not considered as a chief phonemic binary feature. Nevertheless, in the next sub-chapter, it can be seen how length, especially in the context of vowel, becomes prominent because, in the pronunciation, particular environments indeed influence the length of vowels.

B.3.b The Nature of Vowel Length

Many languages have a phonemic contrast of longer versus shorter duration on vowel sounds, although very often this is combined with differences of vowel quality. This is true of English where the checked vowels like // are shorter than the free vowels like/i/ (Collins and Mees, 2003: 65).

Though possibly not as explicit and phonemic as vowel lengthening process in languages like Danish, Finnish, Arabic, Japanese, and Korean, vowel length in English also contributes phonemic values. In English pronunciation, the length of vowel is something which should be observed. The neighboring segment, the preceding one, is recognized as what affecting a vowel to be lengthened (Wolfram and Johnson, 1982: 32). Length can function as a distinctive feature that can show the difference between a particular vowel and another one. How heed differs to hid will proof the distinctiveness possessed by vowel length. There will be no stagnant boundaries about the minimum or maximum duration of vowel length because the duration is “relative to each other” (Clark and Yallop, 1990: 72-73, but see also Fromkin and Rodman, 1969: 81-82).

“English vowels are long when followed by a voiced non-sonorant consonant in the same syllable” (O’Grady et al, 1989: 76). Formulating the phonological rule of vowel lengthening process will be depicted as follows:

V Æ [+ long] / C #

[- long] + voiced - sonorant

B.4. Phonological Processes

B.4.a. Interaction among Sounds

“Clearly, the hierarchy of phonological structure is a dynamic one” (O’Grady et al, 1989: 77). Phonology, as a study which is not stagnant, experiences its dynamicity in the occurrence of phonological processes. Assimilation, dissimilation, epenthesis, metathesis, and deletion are five kinds of the phonological processes (Wolfram and Johnson, 1982: 88). Since the study is dealing with one particular phonological process, assimilation, several theories of assimilation will be presented.

“Assimilation always results in a feature or features from one segment being adjusted to conform with a feature or features from a neighboring segment” (O’Grady et al, 1989: 77). To assimilate means to make similar. It means that, in the process of assimilation, one segment will be “adjusted” to the other segment which influences it due to the place where the influencing segment locates. A feature or features will be added to the influenced sound in order to have it similar to the influencing one.

regularly, it is then formulated into a phonological rule (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988: 99).

There are two kinds of assimilation, namely progressive assimilation and regressive assimilation. These two kinds of assimilation are all related to the place where the influencing segment locates. Progressive assimilation happens when a feature or features from the preceding segment are added to the following influenced segment. The past tense inflectional suffixes case, as well as the case of plural suffixes one, are the instance of progressive assimilation. In the assimilating process, the final sound of the word base contributes an influence to the following attached sound.

Examples:

1. cooked: [kkt]

The final sound of the word base is [k], which is a velar voiceless stop. The voicing status of [k], which is voiceless, influences pronunciation of the past tense inflectional suffix –ed to be alveolar voiceless stop [t].

2. rags [ræz]

Regressive assimilation happens when a feature or features from the following segment are added to the preceding influenced one. Vowel nasalization is a popular example for regressive assimilation.

For instance: [mæn]. In this sequence of sounds, the vowel [æ] is nasalized into [æ] because the segment following it is a nasal stop [n]. The nasal feature owned by the sound [n], which comes right after the vowel [æ], is added regressively to the vowel to conform the nasal sound.

B.4.b. Syllable Structure

Since the study is dealing with the analysis of the relationship between vowels and stop consonants in a syllable, it is important to review some theories about syllable. Syllable is considered as the basic unit in the division of a stream of sound (Wolfram and Johnson, 1982: 13). Sound prominence is what determines a sound sequence to have syllable(s). Mostly in every word made of more than a single sound, there is, at least, one sound which stands out of its other neighboring sounds. That particular standing-out sound is therefore called prominent. The number of prominent sound(s) in sequences of sounds will decide how many syllables exist (Jones, 1958: 134).

prominent sounds in certain sound sequences will help determine the segmentation of the syllable.

In word-syllabification, there are two major divisions involved, namely: onset, and rhyme. The latter can be divided again into two smaller partitions such as: nucleus, and coda (O’Grady et al, 1989). “Vowels usually constitute the ‘main core’ or the nucleus of a syllable” (Fromkin and Rodman, 1988: 47). Other than vowels, liquids and nasals can also hold the nucleic position in a syllable. This happens because the characteristic of liquids and nasals – its resonance – is “so vowel-like”, which means that they, like vowels, are prominently more hearable compared with other consonants. Words like funnel[fnl] and button[btn] are examples in which a liquid or nasal sound can occupy the nuclei position in a syllable (O’Grady et al, 1989:26).

The description of a syllable structure can be seen as follows:

a) Syllabic nucleus (N). The most frequent sound occupying the nucleus is a vowel. kæt spr dk

N N N

b) The cluster of consonants in preceding the nucleus is the onset (O) of a syllable. k æ t

c) The remaining consonant following the nucleus is the coda (C). k æ t : monosyllabic word

O N C (O’Grady, 1989) C. Theoretical Framework

Specifically, to answer the problem formulated, the theories of vowel lengthening process will be utilized to produce the answer of the problem. The theory asserted by O’Grady, which says that “English vowels are long when followed by a voiced non-sonorant consonant in the same syllable” (1989: 76), will be the basic way of thinking when analyzing the data. O’Grady’s vowel lengthening theory is supported by Clark and Yallop who suggest that “…vowels followed by voiced stops and fricatives are considerably longer than those followed by voiceless consonants” (1990: 72). The result of the observation is expected to be a kind of proof which justifies the theory of vowel lengthening process – the theory which is treated as the theoretical temporary answer for the problem of this study.

D. Hypothesis

Since the study uses statistical method in analyzing the data, therefore, the hypothesis that serves as a tentative answer to the problem in the discussion needs to be formulated. The hypothesis presented in this chapter is an operational hypothesis – it is devoted to the ideas asserted in the theory of vowel lengthening process proposed by O’Grady and Clark and Yallop. The hypothesis is formulated as follows:

1. The hypothesis of the relation between back-vowel and the following voiced and voiceless stop consonant

CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

This is the chapter which describes what the present researcher did in the study. Yet, not only would the process of the analysis be depicted in the sub-chapters, but also a fully descriptive and decisive explanation of the object and the data of the study, and the null hypotheses.

A. Object of the Study

Since this study is to analyze the data – words –each of which has a back vowel occupying the nucleic position (the nucleus) of its last syllable, and immediately followed by a voiced or voiceless stop consonant, then, the object of this study is English back vowels, voiced stop consonants, and voiceless stop consonants. Yet, in a deeper look, the focus actually works on the phonological process happening in the environment in which a particular back vowel precedes a certain voiced or voiceless consonant.

There are five back vowels that exist in English. They are [], [u], [],

[o], and []. Out of these five vowels, [] is the only one which does not posses

Stop consonants in English can be classified based on their voicing status. Voiced stop consonants in English are [b], [d], and []. While their voiceless counterparts are [p], [t], and [k]. There are other voiced stop consonants in English, namely [m], [n], and []. However, this group also belongs to another sound’s natural class, categorized as [+ nasal]. Thus, it is not included as the object of the study because the study will only use [- nasal] stop consonants. The reason why this study does not use nasals is for the absence of their voiceless counterparts.

It is stated in the first paragraph of this sub-chapter that, in a deeper look, the focus of the study is on the predictable phonological process emerged by the attachment of a voiced or voiceless stop consonant with a certain back vowel preceding it in a single syllable. Therefore, the analysis will be aimed to observe the details occurring in such phonological process. The phonological process meant here is the assimilation process. More specifically, this phonological phenomenon is called as regressive assimilation in which a feature or features from the following segment are added to the preceding influenced one.

B. The Data

B.1. The Authentic Data

or voiceless stop consonant. Yet, in the second layer of understanding, which is more technical, the data are actually recorded sounds, albeit frankly we must agree that it is the recorded sounds of the chosen words that are analyzed. Still, later on, in the analysis, the recorded sounds of those chosen words will be the authentic compelling data to scrutinize.

The measurement of the length of the back vowel can be obtained only from the analysis of the spectrographic display of the sounds of the pronounced words. Therefore, considering that fact, it is fairer to claim that the real authentic data are the recorded sounds of words chosen based on the requirement needed: words containing a back vowel as the nucleus of the last syllable and immediately followed by a voiced or voiceless stop consonant.

This research employed 92 recorded words. Those 92 recorded words were combined in 46 pairs of recorded sound-strings. The discussion about how those recorded words were set and put into their own specific pairings can be seen in C.2. B.2. The Statistical Data

To make it clear, an example will be given. The back vowel duration of [] in the environment [klk]and [kl] was obtained after the spectrographic analysis had been done. From the analysis, it was acknowledged that the duration of

[] in the first environment was 0.276 second and the duration of [] in the second

environment was 0.403 second. The duration of [] in the first environment (0.276 s) and that of the latter (0.403 s) would be the input of data of the statistical analysis. Therefore, those durations are called the statistical data.

B.3. LONGMAN Dictionary of American-English

As has been stated in the second previous division of this sub-chapter, the data that will be analyzed in this research are the recorded sounds of words containing a back vowel as the nucleus of the last syllable and immediately followed by a voiced or voiceless stop consonant. Therefore, this research necessarily needs an auxiliary bank of data providing those particular words and also their recorded pronunciation.

of recorded daily conversations done by the samples, the research’s volunteers. From the transcription of the recorded conversations the researchers filtered the most common and effective dictions used by American-English native speakers. Lastly, there are two main considerations that make this bank of data worth a use, namely: the entries suit the type of geographical dialect of English this research is studying (American-English); it has an interactive CD-ROM in which all entries are pronounced in the form of recorded voices, which is very important for this research.

By using the data taken from a particular American-English dictionary, it is hoped that the negatively-affective miscellaneous type of pronunciation of words that may be done even by native speakers can be avoided. It is because the recorded voices are loyal to the conventional American-English phonetic transcription of the words uttered. Miscellaneous pronunciations happened because of the different geographical dialects of the speakers had been proven disadvantageous for this particular research especially for the analysis of the data answering the second problem formulation as experienced by the former researcher.

like to have those four different recorded voices just as real persons. Nevertheless, to the devil of it, these “digital” persons take alphabetically random turns in pronouncing the dictions, meaning that they pronounce the words not in a well-distributed portion. Moreover, a single diction is not pronounced by all of the speakers. Instead, one random entry is only pronounced once by one random speaker. This restriction results in an impossibility to treat the recorded sounds distinctively according to the very person pronouncing it. To the worst of it, contextually in this research, since the case study is very specific: to analyze words containing a back vowel as the nucleus of the last syllable and immediately followed by a voiced or voiceless stop consonant, thus, such words will be very specific as well, and there is a possibility that not all those four recorded voices are involved in the pronunciation of the chosen words.

For those reasons, the present researcher decided to treat the recorded voices as recorded voices, which means that, if the term “respondent” is used, this research will have only one respondent, namely the recorded voices acting as the pronunciation of particular words chosen as the data to be analyzed spectrographically. This might not be ideal for the expected statistical data, but that fact gives no other alternatives.

speakers of the dictionary also have their own idiosyncrasy, which may lead to the different characteristic of pronouncing words. Again, the researcher is forced to ignore this fact, at least in this study, since the recorded voices in the dictionary CD-ROM are unable to cope with the ideal statistical data.

B.4. The Ideal Data

The making of this sub-chapter is based on the awareness to formulate requirements which can construct the most ideal data for the research. Nonetheless, there is no guarantee that the data can fulfill the requirements. Still, this classification is needed as a guide to carefully choose the words since many of the sound-combinations provide more number of data than what this study needs.

The qualifications required to form an ideal data for the spectrographic analysis are described as follows:

2. It consists of three sounds only. This requirement is prioritized for, technically, it will ease the researcher to alienate the sound of back vowel from its neighboring sounds. Specifically for the sounds occupying the onset, having two or more consonant clusters will bring more difficulties in isolating the back vowel’s sound.

4. Morphologically, it should not be words which occupy the same suffix – remembering that the last syllable is suggested to be applied as the data. The use of words which occupy the same suffix will result in a “boredom”, meaning that, since the taken sound is obviously the suffix for it is the very last syllable of the word, the characteristic of the sound will be the same, and it will be a considerable waste. For example, there are eighteen words which occupy hood [hd] as their suffix. Just take parenthood, sisterhood,

sainthood, and brotherhood as some of them. It is not suggested to pick up these words as the chosen data. Instead, taking the suffix itself will be more advantageous.

5. No glides occupying the onset. Words containing glides, [w] and [y], occupying the onset of the syllable structure are avoided to be applied as the data of the spectrographic analysis. This is because glides have a quite similar characteristic as vowels do. Especially in American pronunciation of glides,

[y] is “a palatal glide whose articulation is virtually identical to that of the

position of the syllable structure will present another technical difficulty to separate the glide with the back vowel since glides have a close characteristic of articulation compared with vowel.

Thus, to apply the requirements of the ideal data, the example will more or less be described like the following: from the words nincompoop, poop,swoop, and

coop, the best choice will exactly be coop [kup]. Nincompoop is not chosen because it has more than one syllable and its last three sounds are the same as in

poop. Swoop is not chosen because, albeit a monosyllabic word, it contains more than three sounds, and it also contains a glide [w] occupying the onset position. Poop can actually be chosen, but, apparently, it has no voiced minimal pairs. Later on, coop

[kup] is best paired to cube[kub] for they are minimal pairs.

It is essential to know that the requirements made for the ideal data are not absolute. There are many resistances which disable the effort to provide the ideal data. Moreover, the data should not be stuck to the ideal form. If the condition does not allow the researcher to form the ideal data, a dispensation will be given to other data to be applied albeit unable to fulfill the ideal requirements.

C. Method of the Study

C.1. An Empirical Research

which all the areas of the study are limited in books, this research treats recorded sounds as its main source of data. Therefore, since the actual data are recorded voices of the pronunciations of the lexicons in the dictionary, it means that the data are more likely to be empirical rather than bookish.

Conclusively, it will be safer to call this study as an empirical research because it is not merely dealing with words from books, but, actually, with a more concrete form: human speech sounds.

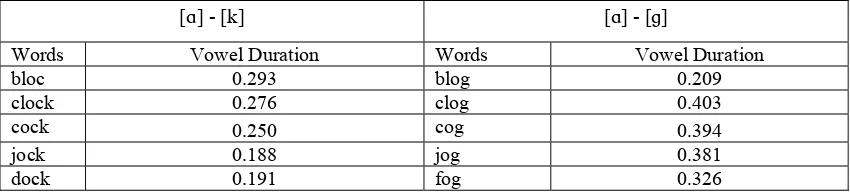

C.2. Data Collecti

![Figure 1. The spectrographic display of the sound-string cop [kp]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/1646625.2069636/68.612.115.529.119.350/figure-spectrographic-display-sound-string-cop-k-p.webp)