Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:24

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Institutional Characteristics and Preconditions for

International Business Education–An Empirical

Investigation

Len J. Trevino & Michael Melton

To cite this article: Len J. Trevino & Michael Melton (2002) Institutional Characteristics and Preconditions for International Business Education–An Empirical Investigation, Journal of Education for Business, 77:4, 230-235, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599077

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599077

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 10

View related articles

Institutional Characteristics and

Preconditions

for

International

Business Education-

An Empirical Investigation

LEN J. TREVINO

MICHAEL MELTON

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Th e University

of

Southern Mississippi Hattiesburg, Mississippi ne can trace the history of interna-0

tional business (IB) education at least back to 1955, when Columbia Uni- versity launched the first international business school program in the United States. Although the importance of international business education was proclaimed by Columbia and others as early as the mid-l950s, it was not until the 1980s, with accelerated globaliza- tion of the world’s economies, that internationalization of business school curricula began to take on a life of its own. Increased interest in IB education has led to wide and varied research onthe subject (Ball

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& McCulloch, 1988, 1993; Kwok & Arpan, 1994; Kwok,Arpan, & Folks, 1994; Nehrt,1987; Thanopoulos & Vernon, 1987). Global- ization of the world’s economy over the last decade has presented schools with unprecedented incentives for interna- tionalizing business school curricula, consistent with Beamish and Calof’s (1989) conclusion that institutions should take steps to internationalize their business programs.

Although much has been written about the importance of internationaliz- ing business school cumcula, no study has focused on institutional factors that

might explain the likelihood

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of aschool’s offering an international busi- ness education. To respond to globaliza- tion trends appropriately, business

ABSTRACT. To respond to global- ization trends that call for a strategic

shift in curricula, business schools

must possess or acquire the resources to allow for such change. In this study,

the authors investigated the institu- tional characteristics that might moti- vate a business school to decide to increase its emphasis on international business education. The authors found seven independent variables that were significant in business schools’ ten- dencies to offer international business courses: age of institution, tuition, stu- dent/faculty ratio, class size, whether

the school is in a state bordering a for- eign country, urban versus rural set- ting, and study-abroad programs. schools must possess or acquire the req- uisite resources. But what is the nature of these resources? Our purpose in this study was to examine institutional char- acteristics that may help to explain the drive toward an emphasis on interna- tional business education. Interestingly, the logic that explains some of the rela- tionships between institutional charac- teristics and internationalization of busi- ness school curricula parallels theoretical motivations that explain for- eign direct investment. That is, both involve decision-making shaped by external environments.

Theory and Hypotheses

We developed a comprehensive model that relates the following groups

of independent variables to the likeli- hood of a school’s having an IB orienta- tion. We measured the dependent vari- able by the number of IB courses offered. The independent variables included institutional factors: whether the institution was public or private, its age, its size, tuition, the school’s type of location was (urban vs. suburban), high- est degree offered by the institution, its American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) accredi- tation status, the student/faculty ratio, the percentage of faculty members hold- ing a doctorate, the percentage of class- es having less than 20 students, whether

the school offered a study-abroad pro- gram, and whether the school was locat-

ed in a state that borders a foreign coun-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

try. Second, we examined demographic factors, as measured by the percentage of international students attending the institution, the percentage of the student body studying business, and the per- centage of out-of-state students attend-

ing the institution.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Institutional Factors

Mixon and Hsing (1994) demonstrat- ed that, because private schools are not subject to state rules and regulations, they face fewer constraints, operate with smaller class sizes, and have a higher academic reputation than their public

230 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinesszyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

school counterparts do. They thus may be able to respond to the call for inter- nationalization more rapidly than public schools can. Concomitantly, schools offering more advanced certification, such as master’s or doctoral degrees, are likely to have more significant resources, such as academic talent and assets that facilitate such expansionary programs as IB education. These schools may be able to respond more rapidly to the environmental call for internationalization than their less advantaged counterparts are. Therefore, we formulated our first two hypotheses: H1: Private schools will tend to offer more international business courses than public schools.

H2: Schools offering more advanced degrees will tend to offer more interna- tional business courses than schools offering less advanced degrees.

Many studies, including Johanson and Vahlne (1977) and Trevino and Daniels (1994), have shown that the process of internationalization is one in which firms gradually increase their international involvement. Firms tend to follow this pattern because testing mar- kets and gaining limited experience before initiating full-scale operations overseas can minimize risk. Just as companies with more extensive opera- tions tend to be older than their less experienced counterparts, a school’s age should tend to be positively correlated to the number of IB course offerings. This hypothesis may hold even if the institution pursues a risk-minimization strategy, such as internationalizing core functional classes before undertaking full-scale internationalization of its cur- ricula.

According to IB theory, firms must logically meet some threshold size to be able to compete at home and have suffi- cient resources to invest abroad as well

(Trevino

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Daniels, 1994). Although this argument applies more directly tothe case of study-abroad programs, we applied this same line of reasoning to schools’ propensities to internationalize their curricula. We assumed that institu- tions with limited resources naturally would satisfy the demand for core func- tional areas, such as marketing, finance, and operations, before responding to

additional demands-such as that for curriculum internationalization-on the institution’s resources. Assets that increase the probability of curricular internationalization must be in excess capacity; thus, we expected that size would be positively correlated to a school’s propensity to offer internation- al business courses.

As shown by Tuckman (1970) and Mixon and Hsing (1 994), when students select universities, they select an opti- mal bundle of investment and consump- tion characteristics. Factors influencing investment characteristics of a universi- ty include quality and marketability of degree programs and tuition. If the mar- ket for higher education is envisioned as being imperfectly competitive, an aca- demic institution may bundle character- istics that lead to more inelastic demand for its services. The change agent glob- alization will possibly lead to a strategic shift within academic institutions. Con- comitantly, schools that respond with IB offerings, consistent with external demands placed on them, will be offer- ing more differentiated and highly mar- ketable degree programs, thus allowing those schools to charge higher prices. We formulated three hypotheses based

on these arguments:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

H3: The older the college or universi-

ty, the more international business courses it will tend to offer.

H4: The greater the size of the col- lege or university, the more internation- al business courses it will tend to offer.

H5: The higher the tuition of the col- lege or university, the more internation- al business courses it will tend to offer.

Researchers have shown that adver- tising generates and maintains product differentiation that allows firms to pur- sue such expansionary policies as for- eign direct investment (Kim & Lyn, 1987). It has been argued that AACSB accreditation, by maintaining product differentiation via reputation and prod- uct quality signaling, acts much like advertising in building a school’s repu- tation. We expected that schools with higher reputations would be more likely to possess assets that enable expansion than schools with lower reputations would be. We also expected that schools with excess capacity would be more

likely to pursue expansionary strategies such as internationalization of business school curricula. The percentage of fac- ulty members holding a doctorate is another institutional investment charac- teristic or resource that might act as an indicator of product quality. As in our reasoning regarding resources in excess capacity, we expected that a higher per- centage of faculty members holding a doctorate would facilitate international- ization of a school’s curricula.

Mixon and Ressler (1995) showed that lower studendfaculty ratios led to a greater interest in the institution among out-of-state students. This finding implies that smaller class sizes are indicative of higher quality in educa- tional institutions. Consistent with our previous arguments relating to product quality and expansion, we expected that the lower the studendfaculty ratio, the greater the likelihood of a school’s hav- ing an international business program. One may assume that the studendfacul- ty ratio acts as a proxy for class size. In fact, class size may be a function of such factors as the number of courses offered each term, or even the institu- tion’s policy dictating the amount of individual attention that a student is allowed. Because graduate-degree- granting institutions, especially re- search-intensive ones, have the option of allowing graduate students to teach, we decided to test another investment characteristic, class size.

We formulated four hypotheses relat- ed to school reputation and product quality:

H6: Schools that are AACSB accred- ited will tend to offer more internation- al business courses.

H7: The greater a school’s percentage of faculty members holding a PhD, the more international business courses it

will tend to offer.

H8: The lower a school’s studendfac- ulty ratio, the more international busi- ness courses it will tend to offer.

H9: The smaller a school’s class size, the more international business courses it will tend to offer.

Grosse and Trevino (1996) found that companies that were geographically closer to their target markets were more

likely to have undertaken international

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MarcWApril2002

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

231expansion than were those companies located farther away. We used a border variable to examine this relationship. Using a binary independent variable, whether a school resided in a state that borders a foreign country, we took into account the distance of our sample’s institutions to international market(s). We expected that this factor would influence a school’s number of IB course offerings. To further develop our hypothesis, we also considered the organization’s general environment: whether it was bounded by country andor state parameters. If the institu-

tion’s state bordered with other

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

U.S.states, we considered its domain domes- tic; if the institution’s state bordered with other countries, we considered its domain international and expected that its operations would be more subject to international pressures.

Given limited resources, an institu- tion must decide on alternate strategies that align it with its external environ- ment. A school located in a nonborder state would be less likely to have an IB orientation because of the perceived lower need to train its students in IB topics, which its graduates would be less likely to need. Conversely, schools located within states that border foreign countries would likely offer an IB edu- cation that benefits the consumers of education (i.e., students) and consumers of the end product (i.e., employers). We expected that a school’s location as defined by an urban versus suburban setting would exert a similar influence: Schools in urban settings, where IB activity is more likely to occur, were expected to have more IB course offer- ings than their suburban competitors. We formulated two hypotheses based on these arguments:

H10: Schools located in a state that borders a foreign country will tend to offer more international business cours- es than schools located in a nonborder state.

H1 1: Schools located in an urban set- ting will tend to offer more internation- al business courses than schools in a nonurban setting.

Study-abroad programs may act as a proxy for the level of interest the insti- tution has in international education as a

whole. In addition, study-abroad pro- grams are highly visible, as evidenced by Kashlak and Jones (1996), who found that 67% of all students in their sample were aware of the university’s international program offerings. In con- trast, study-abroad programs could be used as a substitute; that is, instead of investing in IB classes, institutions could choose to require their students to study abroad. Thus, business schools that have their own IB courses can be considered more vertically integrated than those that use study-abroad pro- grams as a substitute for international business curricula. Coupling these fac- tors led us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H12: Schools offering more study- abroad programs as a substitute for an international business curricula will tend to offer more (fewer) international business courses than schools offering

fewer or no study-abroad programs.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Student Body/Demographics

We decided that a cultural distance factor was related to our geographic dis- tance factor. As U.S. institutions recruit and enroll more international students, American students are increasingly exposed to diversity and differing views of the world. We expected that institu- tions with higher percentages of interna- tional students would be affected by globalization pressures much earlier than would schools with a more isolated student body. This factor should increase the cultural awareness of inter- national diversity, and we expected that schools with higher percentages of international students would have more IB class offerings.

Hymer (1976) found that firms must possess firm-specific competitive advantages that enable them to over- come the inherent disadvantages that they face as a result of operating in an unfamiliar setting. In addition, Dunning (1981) found that the host country for foreign direct investment must possess location-specific advantages in order to entice foreign companies to operate in areas where they face disadvantages resulting from their foreign status. Fol- lowing this line of reasoning, we

expected that out-of-state students would be more attracted to schools with

differentiated product offerings.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A stu- dent thus would be more willing toattempt to overcome the inherent disad- vantages (e.g., increased tuition) of attending a school outside of his or her state if the out-of-state school has advantages over that student’s in-state schools (e.g., an international business curricula). Thus, we expected that high- er out-of-state enrollment would lead to a greater likelihood of a school’s inter-

nationalizing its curricula.

Greater percentages of students studying business rather than other dis- ciplines can increase the political clout of colleges of business. Using this polit- ical power to its advantage, colleges of business may be able to garner more resources from central administration. Therefore, schools with higher percent- ages of students studying business may possess more abundant resources with which to respond to the increased call for curricular internationalization. The following hypotheses stemmed from those arguments:

H13: The greater the percentage of a school’s international students, the more international business courses it will tend to offer.

H14: The greater the percentage of a school’s out-of-state students, the more international business courses it will tend to offer.

H15: The greater the percentage of a school’s business students, the more international business courses it will tend to offer.

Method and Data

We used the 2001 edition of the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

US.

News and World Report-America’s Best Colleges‘ to gather data on institu- tional and demographic factors. Infor- mation not found (given) in the College Edition was attained from College

Source Online.2 Finally, we used

McBane

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

’s List of AACSB-Accredited Business Schools Online3 to gatherinformation pertaining to an institu- tion’s accreditation.

We merged these data sets and delet- ed all institutions that had missing or

inaccurate data for any of the factors we

232

Journal of Education for Businessconsidered in our hypotheses. After these data screens, the final sample con- sisted of 448 randomly selected institu- t i o n ~ . ~ Within this sample, 258 of the institutions were defined as universities and 190 were defined as colleges. One hundred and fifty-three institutions were accredited by the AACSB, and 295 were

not.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Model to Investigate Factors Influencing IB Education

We used a multivariate regression model to test the hypotheses. Based on previous studies, our model could be expressed as:

IBC

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= f(PUB/PRIV, DEGREE, AGE,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(1)SIZE, TUITION, AACSB, %PHD, STUDFAC, CLASS, BORDER, SETTING, ABROAD, %INTL, %OUTSTATE, %BUS)

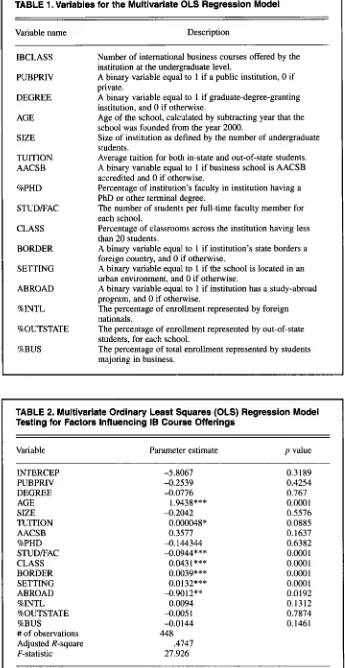

where IBC is the number of internation- al business classes offered by the insti- tution. We provide the variable defini- tions in Table 1. In general, the first 12 variables of equation (1) are institution- al characteristics, whereas the last three variables measure demographic (i.e., student body) characteristics of each college or university in the sample.

Results

In Table 2, we provide our results for estimating Equation 1 through ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Although the model has a .47 adjusted R-square, our focus in this study was the signs and significance of the relation- ships between the endogenous and exogenous variables. The positive and significant AGE variable confirmed our expectations that the older the college or

university was, the more IB course offerings it would have. The positive and significant variable TUITION sub-

stantiated Hypothesis

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 , indicating thatthose institutions having higher tuition would be more apt to have a larger num- ber of IB courses. Hypotheses 8 and 9 were confirmed, with the negative and significant variable STUDFAC and the positive and significant variable CLASS. Those institutions having smaller studendfaculty ratios and small- er classes may be signaling higher qual-

TABLE 1. Variables for the Multivariate OLS Regression Model

Variable name D e s

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c r i p t i o nIBCLASS

PUBPRIV

DEGREE

AGE

SIZE

TUITION AACSB

%PHD

STUDFAC

CLASS

BORDER

SETTING

ABROAD

%INTL

%OUTSTATE

%BUS

Number of international business courses offered by the institution at the undergraduate level.

A binary variable equal to 1 if a public institution, 0 if private.

A binary variable equal to 1 if graduate-degree-granting institution, and 0 if otherwise.

Age of the school, calculated by subtracting year that the school was founded from the year 2000.

Size of institution as defined by the number of undergraduate students.

Average tuition for both in-state and out-of-state students. A binary variable equal to 1 if business school is AACSB accredited and 0 if otherwise.

Percentage of institution’s faculty in institution having a PhD or other terminal degree.

The number of students per full-time faculty member for each school.

Percentage of classrooms across the institution having less than 20 students.

A binary variable equal to 1 if institution’s state borders a foreign country, and 0 if otherwise.

A binary variable equal to 1 if the school is located in an urban environment, and 0 if otherwise.

A binary variable equal to 1 if institution has a study-abroad program, and 0 if otherwise.

The percentage of enrollment represented by foreign nationals.

The percentage of enrollment represented by out-of-state students, for each school.

[image:5.612.222.567.44.712.2]The percentage of total enrollment represented by students majoring in business.

TABLE 2. Multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Model Testing for Factors Influencing IB Course Offerings

Variable Parameter estimate p value

INTERCEP -5.8067

PUBPRIV -0.2539

DEGREE -0.0776

AGE 1.9438***

SIZE -0.2042

TUITION 0.000048*

AACSB 0.3577

%PHD -0.144344

STUDBAC -0.0944***

CLASS 0.043 1

***

BORDER 0.0039***

SETTING 0.0132***

ABROAD -0.9012**

%INTL 0.0094

%OUTSTATE

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

-0.005 1%BUS -0.0144

# of observations 448

Adjusted R-square .4747

F-statistic 27.926

*Significant at the 10% level. ** Significant at the 5% level. ***Significant at the I % level.

0.3 189 0.4254 0.767 0.0001 0.5576

0.0885

0.1637 0.6382 0.0001 0.0001 0.0001

0.0001

0.0192 0.1312 0.7874 0.1461

MarcWApril2002 233

ity through those factors. Consistent with our arguments relating to product quality and expansion, these variables appeared to influence the number of IB courses offered. The positive and signif- icant variable BORDER verified our expectation that institutions located in states bordering foreign countries would tend to offer more IB courses. With respect to location within the state, the positive and significant variable SETTING validated the hypothesis that institutions located in an urban setting would tend to offer a larger number of IB courses. The negative and significant coefficient for the last institutional vari- able, ABROAD, helped to confirm

Hypothesis

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

12, indicating that schoolsmay be using study-abroad programs as a substitute for international business courses.

Though insignificant, the negative coefficient for the PUBPRIV variable was consistent with Hypothesis 1, indi- cating that private institutions would be more likely to have a greater number of IB course offerings. Inconsistent with our earlier hypothesis, our results sug- gest that advanced-degree-granting institutions may be less likely to inter- nationalize their business schools. Although insignificant, this conse- quence may be related to the fewer number of private schools offering such advanced degrees. However, this find- ing warrants further investigation. Whereas one would assume that size does matter, the insignificant and nega- tive coefficient for the SIZE variable

indicated otherwise. We also obtained an interesting result for the accreditation variable (ACCRED). Though the posi- tive sign met our expectations, the insignificance of the variable indicates that accreditation was not a major factor influencing the number of IB courses offered. In addition, the percentage of faculty members holding a PhD did not influence the likelihood of a school’s internationalization of business school curricula.

None of the demographic specific variables were significant at any level. Though the %INTL variable carried the correct sign, the percentage of interna- tional students at the institution did not influence the number of IB courses offered. In addition, the negative and

insignificant variables %OUTSTATE and %BUS did not confirm our earlier hypotheses regarding out-of-state stu- dents and business students. The insignificance of these results suggests that institutional, rather than students, characteristics play a greater role in influencing the internationalization of

business school curricula.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first

study focusing on institutional charac- teristics that help to explain the likeli- hood of a school’s internationalizing its business school curricula. Our findings demonstrate that many variables are sig- nificant in helping to explain the vari- ance in the number of IB course offer- ings among a sample of 448 academic institutions. A greater number of IB course offerings apparently signals to consumers that the school has responded to globalization trends and is attempting to prepare its students to compete in the international economy. A dearth of IB course offerings, conversely, tells prospective students that the institution has not adapted to globalization.

Many of our hypotheses were sup- ported by the empirical results of this study. First, the older schools were more likely to have internationalized their business school curricula. This is con- sistent with multinational enterprise theory that states that older multination- al enterprises are more likely to respond to globalization than are younger multi- national enterprises. In addition, the schools with higher tuition were more likely to have internationalized their business school curricula. Thus, schools that differentiate via IB education may face less elastic demand curves, enabling them to charge higher prices.

The institutions with a lower stu- dendfaculty ratio and/or a smaller class size tended to offer more IB courses. This may indicate that IB education is more of a specialty topic and thus more readily taught in smaller settings. In addition, our study results are in line with multinational enterprise research showing that firms residing in close physical and/or cultural proximity to international markets are more likely to internationalize their operations. Along

these same lines, we found that the like- lihood of more IB course offerings was greater for (a) schools located in a state that borders a foreign country and (b) schools located in an urban setting. These findings demonstrate that busi- ness schools that are closer to interna- tional markets are more influenced by the impetus to internationalize their operations. Furthermore, institutions offering study-abroad programs may be foregoing IB courses and allocating resources elsewhere. This substitution could indicate a cost-reduction effort by the school.

In future studies, researchers could

examine whether the substitute for

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TB

classes (study-abroad programs) is as academically enriching for students as IB courses. Other areas for future research include the possibility of a time-series study as well as a more per- sonalized survey of students, faculty, and administrators. In addition, a more international sample that includes Euro- pean, Asian, and Latin American insti- tutions would help to generalize our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge an anony- mous referee, Frank Mixon, Charles Sawyer, and Rohan Christie-David for comments on earlier drafts of this article, as well as Paula Boone, Jes- sica Gordon, Taisa Minto, and John Rankin for capable research assistance.

NOTES

1. The

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2001zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

U.S. News and World Report col-lege rankings could also be found on the Internet at <www.usnews.com/usnews/edu/college/corank. htms.

2. College Source Online is a subscriber-based data base found in most libraries of institutions of higher learning. Most information not available from the 2001 U.S. News college rankings could be found in this database. In addition, we collect- ed all data on the number of international business courses offered by institutions at the undergradu- ate level from this source.

3. McBane’s List of AACSB-Accredited Brrsi-

ness Schools

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Online can be found at <www.mkt.cba.cmich.edu/aacsbmkt/geolist.htm>.

4. We randomly selected 10 institutions ( 5 col- leges and 5 universities) from the pool of observa-

tions for each state. Those states not containing a

sample set of 10 institutions (AK, AZ, DC, DE,

HI, ID, MT, NH, NV, UT, and WY) include all institutions.

REFERENCES

Ball, D. A., & McCulloch, W. H., Jr. (1988). Inter- national business education programs in Amer- ican and non-American schools: How they are

234 Journal of Education for

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Businessranked by the Academy of International Busi-

ness.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of International Business Studies,Ball, D. A,,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& McCulloch, W. H., Jr. (1993). Theviews of American multinational CEOs on internationalized business education for

prospective employees. Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Internation-al Business Studies, 24(2), 383-391.

Beamish, P.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

W., & Calof, J. L. (1989). Interna-tional business education:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A corporate view.Journal of International Business Studies,

Dunning, J. H. (1981). International production and the multinational enterprise. London: Allen and Unwin.

Grosse, R., & Trevino, L. J. (1996). Foreign direct investment in the United States: An analysis by country of origin. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(1), 139-156.

Hymer, S. H. (1976). The international operations of national j r m s : A study of direct foreign investment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The interna-

19(2), 295-299.

20(3), 553-564.

tionalization process of the firm-A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, Summer, 23-32.

Kim, W. S., & Lyn, E. (1987). FDI theories, entry barriers, and reverse investment in U.S. manu- facturing industries. Journal of International

Business Studies,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

18, 53-66.Kashlak, R. J., & Jones, R.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M. (1996). Interna-tionalizing business education: Factors affect- ing student participation in overseas study pro- grams. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 8(2), 57-15.

Kwok, C. C. Y., & Arpan, J. S. (1994). A compar- ison of international business education at U.S. and European business schools in the 1990s. Management International Review, 34(4), 357-379.

Kwok, C. C. Y., Arpan, J. S., & Folks, W. R. (1994). A global survey of international busi- ness education in the 1990s. Journal qflnterna- tional Business Studies. 25(3), 605-623. Mixon, F. G., Jr., & Ressler, R. (1995). An empir-

ical note on the impact of college athletics on tuition revenues. Applied Economic Letters, 2,

Mixon F. G., Jr., & Hsing, Y. (1994). College stu- dent migration and

human capital theory: A research note. Education Economics, 2( I), 65-73.

Nehrt, L. C. (1987). The internationalization of the cumculum. Journal of International Busi-

ness Studies,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

18( I), 83-90.Thanopoulos, J., & Vernon, I. R. (1987). Interna- tional business education in the AACSB schools. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(1), 91-98.

Trevino, L. J., & Daniels, J. D. (1984). An empir- ical assessment of the preconditions of Japan- ese manufacturing foreign direct investment in the United States. Weltwirtschafriches Archive, 130(3), 576599.

Tuckman, H. P. (1970). Determinants of college student migration. Southern Economic Journal, 37. 184-189.

383-387.