Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:40

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Does Ethicality Wane With Adulthood? A Study of

the Ethical Values of Entrepreneurship Students

and Nascent Entrepreneurs

Fernando Lourenço, Natalie Sappleton & Ranis Cheng

To cite this article: Fernando Lourenço, Natalie Sappleton & Ranis Cheng (2015) Does Ethicality Wane With Adulthood? A Study of the Ethical Values of Entrepreneurship

Students and Nascent Entrepreneurs, Journal of Education for Business, 90:7, 385-393, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1081863

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1081863

Published online: 18 Sep 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 34

View related articles

Does Ethicality Wane With Adulthood? A Study of

the Ethical Values of Entrepreneurship Students and

Nascent Entrepreneurs

Fernando Louren

co

¸

Institute for Tourism Studies, Macau SAR, China

Natalie Sappleton

Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK

Ranis Cheng

Sheffield University, Sheffield, UK

The authors examined the following questions: Does gender influence the ethicality of enterprise students to a greater extent than it does nascent entrepreneurs? If this is the case, then is it due to factors associated with adulthood such as age, work experience, marital status, and parental status? Sex-role socialization theory and moral development theory are used to support the development of hypotheses. A total of 128 undergraduate business enterprise students and 204 nascent entrepreneurs participated in this study. Ordinary least squares regression was used to produce estimates to support hypothesis testing. The findings suggest implications for entrepreneurship education and future research in this area.

Keywords: business enterprise students, business responsibility, entrepreneurship, gender, ethics, nascent entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship education is a critical intervention to stimulate entrepreneurial behavior, an enterprise culture, to promote business startups and minimize failure rates. In higher education (HE), courses in entrepreneurship first emerged and grew in the United States in the late 1970s, later spreading into Europe, and more recently increasing in status in developing countries such as the BRIC nations (Lourenco & Jones, 2006). As an educational discipline,¸ entrepreneurship is also beginning to embrace and tackle issues such as ethics, corporate social responsibility as well as sustainable development to support social wellbeing, environmental protection and economic prosperity. The growth of the sustainability agenda worldwide necessitates the development of business education and knowledge that suits the modern business environment. The power of mass

media, social networks, and the Internet may have also played a role in this development. Greater connectivity means that any wrong doings of corporations can be easily recognized, shared and admonished by consumers across the world.

Evidence of how responsibility can improve the compet-itiveness and financial performance of businesses has been documented in a broad range of studies (Peloza, 2009). This is exemplified in a number of special issues of man-agement education journals, focusing, for example, on: edu-cation for sustainable development (Egri & Rogers, 2003; Rusinko & Sama, 2009; Starik, Rands, Marcus, & Clark, 2010), ethics and social responsibility (Beggs, Dean, Gilles-pie, & Weiner, 2006; Giacalone & Thompson, 2006b), and responsible management education (Forray & Leigh, 2012). There is still a lot be learned, however, particularly in entrepreneurship, which arguably is still an emerging sub-discipline of business and management. One difficulty with the previous literature is that researchers have tended to

Correspondence should be sent to Fernando Lourenco, Institute for¸

Tourism Studies, Colina de Mong-Ha, Macau SAR, China. E-mail: fernan-dolourenco@ift.edu.mo

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1081863

evaluate the ethical perceptions and attitudes of business students while extrapolating the findings to business owners or executives (Bampton & Maclagan, 2009). Where busi-nesspeople have been studied, it is rare for researchers to study samples of entrepreneurs. Rather, the ethical attitudes and actions of line managers (Harris, 1990), business exec-utives (Dawson, 1997), or employees in single occupations such as accountants (Jones & Hiltebeital, 1995) have been examined. We contend that it is important to study the atti-tudes of those engage in entrepreneurship, rather than man-agers because entrepreneurs’ personal value system and that of the organization are often one and the same (Sethi & Sama, 1998).

Business education has an important role to play in shap-ing the values and attitudes of students who will eventually become business practitioners, entrepreneurs, and leaders. A broad range of studies has examined the ethical values of business students and practitioners; however, little research has explicitly focused on those engaged in entrepreneurship courses. In this study we aimed to investigate the relation-ship between aspects of adulthood (gender, age, work expe-rience, marital status, and parental status) and business ethical values among undergraduate enterprise students and nascent entrepreneurs. Following Reynolds (1997), nascent entrepreneurs are defined as individuals committing time and resources to starting up a new business. Sex-role social-ization theory and moral development theory are used to explain the assumptions made in this research.

The following section begins with review of previous studies on business ethics education leading to an explora-tion how gender differences may influence the ethical val-ues of learners. The effect adulthood has on the moral development of individuals is discussed and a series of hypotheses regarding the relative manner in which female and male enterprise students and nascent entrepreneurs respond to ethical business statements are proposed. Hypotheses are then tested using two samples of business enterprise undergraduates and nascent entrepreneurs. We conclude with implications for practice and future research.

BUSINESS ETHICS: STUDENTS, ADULTS, AND GENDER

The business school is a critical agent in the socialization process (Langenderfer & Rockness, 1989; Peery, 1968). It has the potential to influence the process of moral develop-ment and, hence, the ethical behavior of students and future practitioners (for example, see Rest, 1979). Critics have suggested that conventional business education prescribes a mindset that favors profit maximization and materialism whereby aspects such as social responsibility and ethicality are neglected (Ghoshal, 2005; Giacalone & Thompson, 2006a; Mitroff, 2004). Education of this type may promote morally reprehensible behaviors in business students. For

example, studies on cheating behavior found that business students are more likely to cheat on exams (McCabe, But-terfild, & Trevi~no, 2006). Moreover, business students are more likely to engage in unethical behaviors, have higher propensity for material rewards, tend to favor Machiavel-lian actions (Tang, Chen, & Sutarso, 2008). Similarly, work by Klein, Levenburg, McKendall, and Mothersell (2007) indicates that business students have lax attitudes toward ethical behavior.

The literature, nevertheless, also provides findings that contradict those conclusions. For example, there are meta-analyses of business ethics research failing to establish any differences between business and nonbusiness students (Borkowski & Ugras, 1998). Neubaum, Pagell, Drexler, McKee-Ryan, and Larson (2009) failed to establish any dif-ferences between business and nonbusiness students on aspects such as ethical attitudes, moral philosophy, and atti-tudes toward profitability and sustainability. There are also studies that suggest a positive impact of business education toward developing ethical values (Lopez, Rechner, & Olson-Buchanan, 2005), developing attitudes toward sus-tainable development (Neubaum et al., 2009) and corporate environmental practices (Slater & Dixon-Fowler, 2010).

The topic of gender differences in ethics has been widely studied, and not just in the business and management litera-ture. Several studies have found that female students are more ethical than their male counterparts (Beltramini, Peterson, & Kozmetsky, 1984; Chai, Lung, & Ramly, 2009). There is also evidence that females place greater value on corporate ethical, environmental, and societal responsibilities (L€ams€a, Vehkaper€a, Puttonen, & Pesonen, 2008). Some literature suggests that the sex-role socializa-tion process may influence us at an early age in ways that meet the stereotype that accords to our biological sex. For example, according to Gilligan (1982), there is a tendency for women to make judgments based on an ethics of care. This concerns relationships, caring and compassion that relate to oneself and a wider range of potential beneficia-ries. It is suggested that men are more likely to judge ethical dilemmas based on justice or rule-based reasoning pro-cesses. The rationalized moral justification tends to suit self or corporate interest and may influence men to make less ethical decisions. The profit maximization and shareholder value that is taught in conventional business education may have reinforced the notion of business in accordance with the stereotypical male sex role.

There is evidence, nevertheless, indicating that gender differences eventually disappear when individuals reach adulthood and become professionals, possibly because exposure to professional roles enforces similarities between sexes in ethical behavior (Betz, O’Connell, & Shepard, 1989). As individuals age, they are repeatedly exposed to social norms that have the potential to influence their values and behaviors via the socialization process (Mujtaba & Sims, 2006). These social norms have their own ethical

386 F. LOURENCO ET AL.¸

standards and values. Social norms are attached to different institutions, such as families, culture, schools, media, work-place, and networks. More exposure to social norms and ethical standards will take place as an individual grows into adulthood. This phase of life will affect their values toward ethics, as well as values that fit their current roles (Mujtaba & Sims, 2006). Serwinek (1992) suggests that such changes are due to the effect of social influences that increase the conservative position on ethics held by individuals as they age. The longer a person is exposed to standards permeating all life activities, the more likely a person will be to accept those standards. Known unethical behaviors can potentially jeopardise adults’ financial security as well as their status quo in business and in society (Lerner, 1980).

Based on the findings and assumptions derived from the literature discussed previously, the first hypothesis was pro-posed to examine if gender differences disappear among adult nascent entrepreneurs engaging in business startup program compared to undergraduate business enterprise students:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Gender would be significantly related to ethical values of enterprise students but not among adult nascent entrepreneurs.

THE EFFECT OF ADULTHOOD

Greater exposure to social norms and ethical standards will take place as an individual grows into adulthood. This phase of life will affect their values toward ethics and val-ues that fit their current roles (Mujtaba & Sims, 2006). The theory of moral development as proposed by Kohlberg (1969) and later extended in by Rest (1979) explains how age is related to the development of ethical values. This the-ory suggests that morality and ethicality evolve over time, via multiple moral developmental stages. The older an indi-vidual is, the longer the period of moral development a per-son will have. This leads to higher level of moral reaper-soning that will influence ethical values and behaviors.

Age has been used in many empirical studies to examine its effect on ethical reasoning and behavior. Empirical investigations yield, to some extent, inconsistent outcomes. For example, there are studies that have produced few sig-nificant differences between individuals of different ages in terms of ethics (Burton & Casey, 1980; Eweje & Brunton, 2010). In one study, senior students displayed more unethi-cal behavior than junior students (Tse & Au, 1997). There is also a broad range of studies yielding contradictory find-ings. For example, Borkowski and Ugras’s (1998) meta-analysis of ethics studies found that older students exhibited higher ethical attitudes than younger students. Rawwas and Singhapakdi’s (1998) study also indicated that a person’s ethical values grows with age. A recent study of undergrad-uate business students in the United States found that senior

business students have positive attitudes toward sustainabil-ity and have stronger intentions to work for responsible companies compared to junior business students (Neubaum et al., 2009).

Work experience has also been examined in previous studies concerned with business ethics and sustainable entrepreneurship. Previous research also linked life experi-ence with moral development theory to explain ethical behavior (Rest, 1979). Once again, results are generally mixed. For example, one empirical study failed to produce any significant relationship between ethical perceptions and years of work experience among business owners and employees (Serwinek, 1992). Parsa and Lankford (1999) found that experienced master of business administration students exhibited lower ethical values compared to under-graduate students. Kraft and Singhapakdi (1991) found that business managers exhibited less concern for ecology com-pared to business students. Another study found that stu-dents with greater levels of experience appear to be more ethically oriented (Eweje & Brunton, 2010). Glover, Bumpus, Sharp, and Munchus (2002) suggested that age and years of work experience moderate the relationship between gender and ethics. As previous studies offer little consistency, this study draws on the theory of moral devel-opment to assume that age and work experience are posi-tively related to values toward ethical business practice:

H2: Among enterprise students and adult nascent entre-preneurs, age would be positively related to atti-tudes toward business ethics.

H3: Among enterprise students and adult nascent entrepre-neurs, work experience would be positively related to attitudes toward business ethics.

As argued in Serwinek (1992), we are all exposed to social norms that influence our values and behaviors. Social norms are attached to different institutions, such as fami-lies, culture, schools, media, workplace and networks. Hav-ing a family and children, will inevitably expose a person to social norms associated with such life situation and roles that requires care for others and nurturance. Individuals learn and internalize these roles and ethical standards via the socialization process and therefore develop their moral attitudes and values that fit their current roles. Empirical studies in this particular aspect are lacking and the findings of those that do exist are inconclusive (Swaidan, Vitell, & Rawwas, 2003). On the one hand, there are studies that did not find any relationship between ethics and parental status (Serwinek, 1992) and marital status (Rawwas & Isakson, 2000; Serwinek, 1992). On the other hand, Premeaux (2005) discovered that married individuals are more likely to cheat on exams and another study argued that outside commitments increase the tendency toward cheating (Now-ell, 1997). Erffmeyer, Keillor, and LeClair (1999) found that married people are more likely to accept questionable

practices compared to single individuals, and are more likely to be classified as relativists or Machiavellians than unmarried individuals. There is also a range of studies that indicates that having family responsibilities may influence a person’s ethical values and behavior. For example, Devitt and Hise (2002) found that family responsibilities affect a person’s ethical judgment and decision-making process. Spence and Lozano (2000) found that informal mechanisms (e.g., family) can influence business owners’ attitudes toward ethical issues. Poorsoltan, Amin, and Tootoonchi (1991) produced findings that suggest that married students are more conservative and moral than those that are single. This study follows the assumptions of sex-role socialization theory (Blau, Ferber, & Winkler, 2006; Holmes, 2007) and moral development theory (Kohlberg, 1984; Rest, 1979) to suggest that marital status and parental status will signifi-cantly affect adult nascent entrepreneurs attitudes toward business ethics:

H4: Among adult nascent entrepreneurs, marital status would be positively related to attitudes toward busi-ness ethics.

H5: Among adult nascent entrepreneurs, parental status would be significantly related to attitudes toward busi-ness ethics.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

This study includes a group of undergraduate business enterprise students at a University Business School in the Northwest of England and a group of nascent entrepreneurs undergoing a government-funded business startup program run by the same University. Training sessions designed to assist individuals seeking to start-up and manage a small business were exposed to these two sample groups. Partici-pants completed and returned a survey that included multi-ple items examining attitudes toward business ethics. In order to reduce socially desired responses, participants were informed that the survey results would be treated anonymously, their perceptions treated as confidential and their data would not be used to assess their performance in the training program. The returned questionnaires were col-lected via a designated box outside the classroom as an additional anonymity strategy. A 100% response rate was obtained although participation in the survey was strictly and expressly voluntary. A total of 128 students and 204 nascent entrepreneurs completed the survey.

Measures and Analysis

Twelve statements probing respondents’ attitudes to a vari-ety of ethical statements were used in the questionnaire.

Four items were adopted from the new environmental para-digm scale (Noe & Snow, 1990; Roberts, 1996), four items from the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility scale (Singhapakdi, Vitell, Rallapalli, & Kraft, 1996) and another four items adopted the attitude toward business ethics questionnaire (Etheredge, 1999). Examples of these statements are social responsibility and profitability can be compatible; good ethics is often good business; moral val-ues are irrelevant to the business world; the only moral of business is making money. The respondents rated their agreement to each of the items using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The dependent variables for gender were coded 1 D male and 2Dfemale. Occupation was coded 1Dstudent and 2Dentrepreneur. The independent variables, age and years of work experience, were treated as continuous varia-bles. These two variables were used to represent the extant length of exposure to social norms. Entrepreneurs that were not married or living with partner were coded 0, and entre-preneurs that were married or living with a partner were coded 1. Entrepreneurs without children were coded 0; those with children were coded 1. These two variables were used to represent the exposure to key life phase associated to adulthood.

We adopted the statistical software program SPSS (ver. 19) for Windows to analyze the data collected from the questionnaires. The use of principal component analysis supported the refinement of the constructs for hypothesis testing. Ordinary least squares regression was used to pro-duce estimates to support hypothesis testing. For ease of interpretation, separate tests were run for the student and entrepreneur samples.

FINDINGS

The age, years of work experience, and education level dif-fer between the two samples (Table 1). Students were around 12–14 years younger than the nascent entrepreneurs and had 13–14 years less work experience, and the majority of the student sample were single compared to around half of the entrepreneur sample who were married or living with partner and had children.

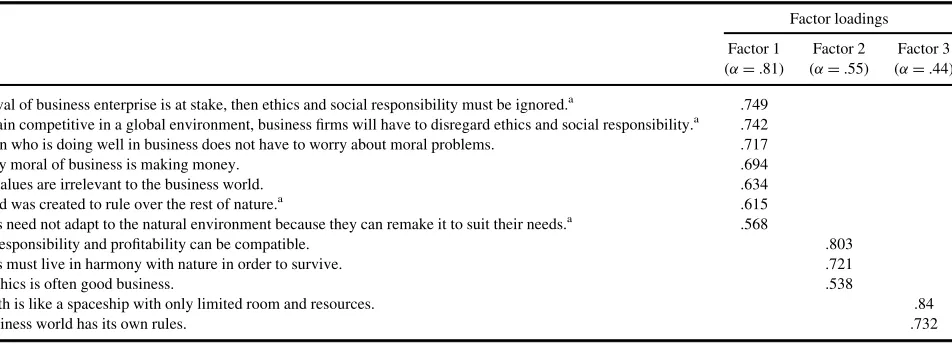

Principal components analysis with a varimax solution was used to construct indices of ethics. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant atp<.001 and a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy of 0.830 indicated that it was acceptable to proceed with the analysis. Compo-nents with eigenvalues of 1 or above were selected and fac-tors loadings above 0.4 were considered acceptable (Stevens, 2002). The results of the principal components analysis are reported in Table 2. All items loaded power-fully onto one of three factors with minimal cross loading. Together, the factors explain 53.18% of the total variance

388 F. LOURENCO ET AL.¸

in the data. Cronbach’s alpha scores were calculated for each factor in order to determine reliability. Only factor 1 reached the minimum acceptable figure of 0.7 recom-mended by Nunnally (1978), and this factor is used for sub-sequent analysis.

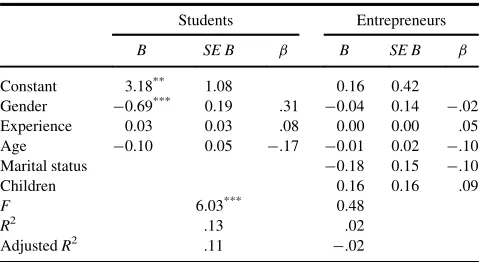

Consistent with the previous literature, the regression shows an effect for gender in the student sample, but this variable loses its significance in the sample of nascent entrepreneurs (see Table 3 for the results of the ordinary least squares regression). Attitudes toward business ethics are lower among male compared to female enterprise stu-dents. The t-test revealed that in statistical terms, female students (M D ¡0.22,SD D0.87) were more ethical than male students (MD0.49,SDD1.07),tD2.19,p<.001. Attitudes toward business ethics were lower among enter-prise students compared to nascent entrepreneurs. The result derived from a t-test revealed that students (M D

0.25,SD D1.06) were less ethical than nascent entrepre-neurs (MD ¡0.15,SDD0.94),tD3.66,p<.001. As sug-gested byH1, there was no sex difference between nascent entrepreneurs. Women and men indicate positive signs of

ethical attitudes. Hence women (M D ¡0.20, SDD 0.95) and men (M D ¡0.11, SD D0.91) nascent entrepreneurs were not statistically different in our study,tD0.65,p D

.515. This provides support for H1; however, the assump-tions that age, years of work experience, marital status, and parental status had an effect on the ethicality are not sup-ported across all samples. This suggests a lack of support forH2–H5.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This study indicates that female enterprise students are sig-nificantly more ethical than their male counterparts. This study suggests that sex-role socialization has a role in shap-ing the attitudes of these young individuals. In the case of female students, the stereotypical role played by women is internalized at an early age and via this process they are nurtured to be more caring, have greater concern with rela-tionships and their behavior is more inclined to support relationships in such a way as to gain approval by others

TABLE 2

Principle Component Analysis

Factor loadings Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 (aD.81) (aD.55) (aD.44)

If survival of business enterprise is at stake, then ethics and social responsibility must be ignored.a .749

To remain competitive in a global environment, business firms will have to disregard ethics and social responsibility.a .742

A person who is doing well in business does not have to worry about moral problems. .717 The only moral of business is making money. .694 Moral values are irrelevant to the business world. .634 Mankind was created to rule over the rest of nature.a .615

Humans need not adapt to the natural environment because they can remake it to suit their needs.a .568

Social responsibility and profitability can be compatible. .803 Humans must live in harmony with nature in order to survive. .721

Good ethics is often good business. .538

The earth is like a spaceship with only limited room and resources. .84

The business world has its own rules. .732

aItem was reverse-coded.

TABLE 1 Descriptive Characteristics

Student sample Entrepreneur sample

Male (nD84) Female (nD44) Male (nD100) Female (nD104)

Mean age (years) 21.2 21.9 36 34

Mean years of work experience 2.2 3.2 17.1 15.2 Educated to undergraduate level (%) 100 100 39.1 44.1

Has children (%) 0 2.3 51 49.5

Marital status (%)

Single 94.0 70.5 42.2 47.7

Married/living with partner 3.6 29.5 50 46.8

Other 2.4 0.0 7.8 5.5

(Barnett & Karson, 1989; McCabe, Ingram, & Dato-on, 2006). The stereotypical traits of male behavior reflect the business ideal of the free market society where organiza-tional success depends on the aggressive nature manifested in the behavior of its employees (McCabe et al., 2006; Spence, 1993; Spence & Buckner, 2000). Such values could have been reinforced among male enterprise students via their business education (Giacalone, 2004, 2007; Giacalone & Thompson, 2006a) and this could potentially explain their relatively low ethicality. This suggests implications for business schools to improve the moral development of male enterprise students, in particular, in order to develop their values toward responsible business. This area proves to be heating up in recent entrepreneurship journals in the forms of ethics in entrepreneurship, responsible entre-preneurship, green entreentre-preneurship, social entrepreneur-ship and sustainable entrepreneurentrepreneur-ship.

Business ethics has been an integral aspect of most busi-ness curriculum. Entrepreneurship education can benefit by building sustainability and ethicality into the content of its content. For example, Paschall and W€ustenhagen (2012) offered suggestions regarding the use of role-play activities to teach social responsibility and sustainability. Role-play activities can be adapted where students have to start up and run micro enterprises to teach entrepreneurship as well as how to make a business sustainable, responsible, and eth-ical (McCormick & Gray, 2011). Moreover, students can become the champions for their university, encouraging pedagogics to develop new policies with the capacity to create a responsible and entrepreneurial university (Lavine & Roussin, 2012). There are opportunities to engage stu-dents in action research (Benn & Dunphy, 2009), where critical thinking (Kearins & Springett, 2003) and systems thinking (Porter & Cordoba, 2009) are applied via service-learning strategies (McCrea, 2010). This particular activity allows students to engage in a range of community projects to manage stakeholders’ expectations and to identify

entrepreneurial solutions that are sustainable and responsi-ble (Collins & Kearins, 2007). There is scope for opportu-nity identification and innovation courses with a focus on sustainable business practices and sustainable innovation (Steketee, 2009; Viswanathan, 2012). There is also room for courses on making specific business functions sustain-able, responsible and ethical (Walker, Gough, Bakker, Knight, & McBain, 2009). Furthermore, it is important to raise the point that success can come from both sexes throughout the learning process. Multiple cases and role models from both sexes should be used to highlight this point. The ultimate aim is to improve students awareness as well as providing students with opportunities to implement these ideas to do well in business (Cordano, Ellis, & Scherer, 2003).

This study provides evidence that both male and female adult nascent entrepreneurs are generally equal in terms of their level of ethicality. This supports the argument that gender differences between students disappear among older samples and professionals (Betz et al., 1989). This has implications for future research because it suggests that enterprise students do not serve as a valid proxy to explain the attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs who are older, have longer work experience, and have different marital and parental status. This study argues that the development of ethical values can be due to the exposure of social norms and influences associated to being in adulthood. This study, nonetheless, informs us that being married or living with a partner and having children has no effect on ethical values toward business practice among nascent entrepre-neurs. Similar to previous research (e.g., Burton & Casey, 1980; Eweje & Brunton, 2010), this study also failed to uncover any relationship between work experience, age and ethicality. Future statistical models should move beyond simple socio-demographic variables to explain the disappearance of the gender gap (Tavris, 1992). It has been suggested that multidimensional social-psychological-environmental constructs will contribute to a deeper under-standing of ethical perceptions of individuals (Lan, Gow-ing, McMahon, Rieger, & KGow-ing, 2008; McCabe et al., 2006). Values held by each individual will have significant impacts on the reasoning and decision-making process leading to actual behavior (see the review of Lan et al., 2008). Our personal values and perceptions of desirable or ideal behavior will influence the evaluation of actions and moral reasoning (Jones, 1991; Rokeach, 1967). Schwartz (2005) argued that our priorities among different values are only understood when judgments or actions have con-flicting implications. How we prioritize values and make trade-offs will inevitably influence our moral reasoning processes and behaviors. Previous studies provide some evidence to support these assumptions (for example, Fritz-sche & Oz, 2007; Lan et al., 2008).

To overcome the limitations of the present study, future researchers should examine

social-psychological-TABLE 3

Ordinary Least Squares Regression, by Sample

Students Entrepreneurs

B SE B b B SE B b

Constant 3.18** 1.08 0.16 0.42

Gender ¡0.69*** 0.19 .31 ¡0.04 0.14 ¡.02

Experience 0.03 0.03 .08 0.00 0.00 .05 Age ¡0.10 0.05 ¡.17 ¡0.01 0.02 ¡.10

Marital status ¡0.18 0.15 ¡.10

Children 0.16 0.16 .09

F 6.03*** 0.48

R2 .13 .02

AdjustedR2 .11 ¡.02

Note.For marital status and children, analysis was not conducted among the student sample.

*p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001.

390 F. LOURENCO ET AL.¸

environmental constructs according to the way in which values are formed during the socialization process. For example, studies can be established by investigating the values held by individual and family, school and univer-sity, peers and colleagues, workplace, previous educa-tion, work experience, and via other social groups and social institutions (e.g., community, culture, business sector). It is important to examine the influence of these values on the moral development, moral reasoning, moral decision making, and moral behaviors as well as learning among business practitioners and entrepreneurs, in particular.

CONCLUSION

We investigated the ethicality of undergraduate business enterprise students and adult nascent entrepreneurs. The findings indicate that male enterprise students have lower ethical attitudes toward business compared to female enterprise students and adult nascent entrepreneurs. Moreover, a gender gap only exists between young enter-prise students; this disparity disappears among the adult nascent entrepreneurs. The findings suggest that being in adulthood—as explained by age, work experience, mari-tal status and parenmari-tal status—is not a significant factor that affects the ethicality of individuals. Future research-ers will benefit from the examination of more complex variables, such as the values associated with different social groups and social institutions. This study contrib-utes to business ethics studies and ethics education by testing a range of previously held assumptions on two samples that have, up to now, been neglected in this field of research.

REFERENCES

Bampton, R., & Maclagan, P. (2009). Does a ‘care orientation’ explain gender differences in ethical decision making? A critical analysis and fresh findings.Business Ethics: A European Review,18, 179–191. Barnett, J. H., & Karson, M. J. (1989). Managers, values, and executive

decisions: An exploration of the role of gender, career stage, organiza-tional level, function, and the importance of ethics, relationships and results in managerial decision-making.Journal of Business Ethics,8, 747–771.

Beggs, J. M., Dean, K. L., Gillespie, J., & Weiner, J. (2006). The unique chal-lenges of ethics instruction.Journal of Management Education,30, 5–10. Beltramini, R. F., Peterson, R. A., & Kozmetsky, G. (1984). Concerns of

college students regarding business ethics.Journal of Business Ethics,3, 195–200.

Benn, S., & Dunphy, D. (2009). Action research as an approach to integrat-ing sustainability into MBA programs: An exploratory study.Journal of Management Education,33, 276–295.

Betz, M., O’Connell, L., & Shepard, J. M. (1989). Gender differences in proclivity for unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 8, 321–324.

Blau, F., Ferber, M. A., & Winkler, A. E. (2006).The economics of women, men and work. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. Borkowski, S. C., & Ugras, Y. J. (1998). Business students and ethics: A

meta-analysis.Journal of Business Ethics,17, 1117–1127.

Burton, R. V., & Casey, W. M. (Eds.). (1980).Moral development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chai, L. T., Lung, C. K., & Ramly, Z. (2009). Exploring ethical orientation of future business leaders in Malaysia.International Review of Business Research Papers,50, 109–120.

Collins, E., & Kearins, K. (2007). Exposing students to the potential and risks of stakeholder engagement when teaching sustainability: A class-room exercise.Journal of Management Education,31, 521–540. Cordano, K. M., Ellis, K. M., & Scherer, R. F. (2003). Natural capitalists:

Increasing business students’ environmental sensitivity.Journal of Man-agement Education,27, 144–157.

Dawson, L. M. (1997). Ethical differences between men and women in the sales profession.Journal of Business Ethics,16, 1143–1152.

Devitt, R. M., & Hise, J. V. (2002). Influences in ethical dilemmas of increasing intensity.Journal of Business Ethics,40, 261–274.

Egri, C. P., & Rogers, K. S. (2003). Teaching about the natural environ-ment in manageenviron-ment education: new directions and approaches.Journal of Management Education,27, 139–143.

Erffmeyer, R. C., Keillor, B. D., & LeClair, D. T. (1999). An empirical investigation of Japanese consumer ethics.Journal of Business Ethics,

18, 35–50.

Etheredge, J. M. (1999). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibil-ity: An alternative scale structure.Journal of Business Ethics,18, 51–64. Eweje, G., & Brunton, M. (2010). Ethical perceptions of business students in a New Zealand university: Do gender, age and work experience mat-ter?Business Ethics: A European Review,19, 95–111.

Forray, J. M., & Leigh, J. S. A. (2012). A primer on the principles of responsible management education: Intellectual roots and waves of change.Journal of Management Education,36, 295–309.

Fritzsche, D., & Oz, R. (2007). Personal values’ influence on the ethical dimension of decision making.Journal of Business Ethics,75, 335–343. Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good man-agement practice.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 75–91.

Giacalone, R. A. (2004). A transcendent business education for the 21st century.Academy of Management Learning & Education,3, 415–420. Giacalone, R. A. (2007). Taking a Red Pill to disempower unethical

stu-dents: Creating ethical sentinels in business schools.Academy of Man-agement Learning & Education,6, 534–542.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006a). Business ethics and social responsibility education: Shifting the worldview.Academy of Manage-ment Learning & Education,5, 266–277.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006b). From the guest co-editors: Special issue on ethics and social responsibility.Academy of Manage-ment Learning & Education,5, 261–265.

Gilligan, C. (1982).In a different voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-sity Press.

Glover, S. H., Bumpus, M. A., Sharp, G. F., & Munchus, G. A. (2002). Gender differences in ethical decision making.Women in Management Review,17, 217–227.

Harris, J. (1990). Ethical values of individuals at different levels in the organi-zational hierarchy of a single firm.Journal of Business Ethics,9, 741–750. Holmes, M. (2007).What is gender?London, England: Sage.

Jones, S. K., & Hiltebeital, K. M. (1995). Organizational influence in a model of the moral decision process of accoutants.Journal of Business Ethics,14, 417–431.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organiza-tions: An issue-contingent model.Academy of Management Review,16, 366–395.

Kearins, K., & Springett, D. (2003). Educating for sustainability: Develop-ing critical skills.Journal of Management Education,27, 188–204.

Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., McKendall, M., & Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: How do business school students compare?Journal of Business Ethics,72, 197–206.

Kohlberg, L. (1984).Essays on moral development. San Francisco CA: Harper and Row.

Kohlberg, L. (Ed.). (1969).Stage sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Kraft, K. L., & Singhapakdi, A. (1991). The role of ethics and social responsibility in achieving organizational effectiveness: Students versus managers.Journal of Business Ethics,10, 679–689.

L€ams€a, A. M., Vehkaper€a, M., Puttonen, T., & Pesonen, H. L. (2008). Effect of business education on women and men students attitudes on corporate responsibility in society.Journal of Business Ethics,82, 45–58. Lan, G., Gowing, M., McMahon, S., Rieger, F., & King, N. (2008). A study

of the relationship between personal values and moral reasoning of under-graduate business students.Journal of Business Ethics,78, 121–139. Langenderfer, H., & Rockness, J. (1989). Integrating ethics into the

accounting curriculum: Issues, problems and solutions. Issues in Accounting Education,4, 58–69.

Lavine, M. H., & Roussin, C. J. (2012). From idea to action: Promoting responsible management education through a semester-long academic integrity learning project.Journal of Management Education,36, 428–455. Lerner, M. (1980).The belief in a just world. New York, NY: Plenum. Lopez, Y. P., Rechner, P. L., & Olson-Buchanan, J. B. (2005). Shaping

eth-ical perceptions: An empireth-ical assessment of the influence of business education, culture, and demographic factors.Journal of Business Ethics,

60, 341–358.

Lourenco, F., & Jones, O. (2006). Developing entrepreneurship education:¸

Comparing traditional and alternative teaching approaches. Interna-tional Journal of Entrepreneurship Education,4, 111–140.

McCabe, A. C., Ingram, R., & Dato-on, M. C. (2006). The business of ethics and gender.Journal of Business Ethics,64, 101–116.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevi~no, L. K. (2006). Academic dis-honesty in graduate business programs: Prevalence, causes, and proposed action.Academy of Management Learning & Education,5, 294–305. McCormick, B., & Gray, V. (2011). Message in a bottle: Basic business

lessons for entrepreneurs using only a soft drink.Journal of Manage-ment Education,35, 282–310.

McCrea, E. A. (2010). Integrating service-learning into an introduction to entrepreneurship course. Journal of Management Education, 34, 39–61.

Mitroff, I. (2004). An open letter to the deans and the faculties of American Business Schools.Journal of Business Ethics,54, 185–189.

Mujtaba, B. G., & Sims, R. L. (2006). Socializing retail employees in ethi-cal values: The effectiveness of the formal versus informal methods.

Journal of Business and Psychology,21, 261–272.

Neubaum, D. O., Pagell, M., Drexler, J. A. Jr., McKee-Ryan, F. M., & Lar-son, E. (2009). Business education and its relationship to student per-sonal moral philosophies and attitudes toward profits: An empirical response to critics.Academy of Management Learning & Education,8, 9–24.

Noe, F. P., & Snow, R. (1990). The new environmentalism paradigm and further scale analysis.Journal of Environmental Education,21(4), 20– 26.

Nowell, C. (1997). Undergraduate student cheating in the fields of busi-ness.Journal of Economic Education,28, 3–13.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978).Psychometric theory. New York, NY: MacGraw-Hill. Parsa, F., & Lankford, W. M. (1999). Student’s views of business ethics:

an analysis.Journal of Applied Psychology,29, 1045–1057.

Paschall, M., & W€ustenhagen, R. (2012). More than a game: Learning about climate change through role-play.Journal of Management Educa-tion,36, 510–543.

Peery, W. G. (1968).Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years: A scheme. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Peloza, J. (2009). The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance.Journal of Management,

35, 1518–1541.

Poorsoltan, K., Amin, S., & Tootoonchi, A. (1991). Business ethics: Views of future leaders.S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal,56, 4–10.

Porter, T., & Cordoba, J. (2009). Three views of systems theories and their implications for sustainability education.Journal of Management Edu-cation,33, 323–347.

Premeaux, S. R. (2005). Undergraduate student perceptions regarding cheating: Tier 1 versus Tier 2 AACSB accredited business schools.

Journal of Business Ethics,62, 407–418.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., & Isakson, H. (2000). Ethics of tomorrow’s business managers: The influence of personal beliefs and values, individual char-acteristics, and situational factors.Journal of Education for Business,

75, 321–330.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., & Singhapakdi, A. (1998). Do consumers’ ethical beliefs vary with age? A substantiation of Kohlberg’s typology in mar-keting.Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice,6, 26–38.

Rest, J. R. (1979).Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Reynolds, P. D. (1997). Who starts new firms? Preliminary explorations of firms-in-gestation.Small Business Economics,9, 449–462.

Roberts, A. J. (1996). Green consumer in 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising.Journal of Business Research,36, 217–231.

Rokeach, M. (1967).Value survey. Sunnyvale, CA: Halgren Tests. Rusinko, C. A., & Sama, L. M. (2009). Greening and sustainability across

the management curriculum: An extended journey.Journal of Manage-ment Education,33, 271–275.

Schwartz, M. S. (2005). Universal moral values for corporate codes of ethics.Journal of Business Ethics,59, 27–44.

Serwinek, P. (1992). Demographic & related differences in ethical views among small businesses.Journal of Business Ethics,11, 555–566. Sethi, S. P., & Sama, L. M. (1998). Ethical behavior as a strategic choice by

large corporations: The interactive effect of marketplace competition, industry structure and firm resources.Business Ethics Quarterly,8, 85–104. Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Rallapalli, K. C., & Kraft, K. L. (1996). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: A scale development.

Journal of Business Ethics,15, 1131–1140.

Slater, D. J., & Dixon-Fowler, H. R. (2010). The future of the planer in the hands of MBAs: An examination of CEO MBA education and corporate environmental performance.Academy of Management Learning & Edu-cation,9, 429–441.

Spence, J. T. (1993). Gender-related traits and gender ideology: Evidence for a multifactorial theory.Journal of Personality and Social Psychol-ogy,64, 624–635.

Spence, J. T., & Buckner, C. E. (2000). Instrumental and expressive traits, trait stereotypes, and sexist attitudes.Psychology of Women Quarterly,

24, 44–62.

Spence, L. J., & Lozano, J. F. (2000). Communicating about ethics with small firms: Experiences from the U.K. and Spain.Journal of Business Ethics,27, 43–53.

Starik, M., Rands, G., Marcus, A. A., & Clark, T. S. (2010). From the guest editors: In search of sustainability in management education.Academy of Management Learning & Education,9, 377–383.

Steketee, D. (2009). A million decisions: Life on the (sustainable business) frontier.Journal of Management Education,33, 391–401.

Stevens, J. P. (2002).Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences

(4th ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Swaidan, Z., Vitell, S. J., & Rawwas, M. Y. A. (2003). Consumer ethics: Determinants of ethical beliefs of African Americans.Journal of Busi-ness Ethics,46, 175–185.

Tang, T. L.-P., Chen, Y.-J., & Sutarso, T. (2008). Bad apples in bad (busi-ness) barrels:The love of money, machiavellianism, risk tolerance, and unethical behavior.Management Decision,46, 243–263.

392 F. LOURENCO ET AL.¸

Tavris, C. (1992).The mismeasure of woman: Why women are not the bet-ter sex, the inferior sex, or the opposite sex. London, England: Touch-stone Books.

Tse, A. C. B., & Au, A. K. M. (1997). Are New Zealand business students more unethical than non-business students.Journal of Business Ethics,

16, 445–450.

Viswanathan, M. (2012). Curricular innovations on sustainability and sub-sistence marketplaces: Philosophical, substantive, and methodological orientations.Journal of Management Education,36, 389–427. Walker, H. L., Gough, S., Bakker, E. F., Knight, L. A., & McBain, D. (2009).

Greening operations management: An online sustainable procurement course for practitioners.Journal of Management Education,33, 348–371.