Comunicar,

49,

XXIV,

2016

Media Education around the World:

Curriculum & Citizenship

La educación en comunicación en el mundo: currículum y ciudadanía

Guest-edited special issue: Dr. Alexander Fedorov, Rostov State University of Economics (Russia) Dr. Jorge-Abelardo Cortés-Montalvo, Autonomous University of Chihuahua (Mexico)

Dr. Yamile Sandoval-Romero, University of Santiago de Cali (Colombia)

I

ntroduction

ommunicative competence, positioned today globally in a transverse axis for the exercise and performance of any other academic competence, marks a required pattern to recognize that it is necessary for educational environments to contribute to the process of media literacy as an essential part of it is vital in everyday life both for teachers and students, aimed primarily at the formation of responsible and critical citizenship.

The incorporation of education and media literacy in the curriculum for all levels of education, from preschool to university, has been the subject of recent discussions and analysis in several countries, the proposals also include teacher training, as is the case Curriculum for Media and Information Literacy for Teachers (Media Information Literacy, MIL), in which UNESCO points out a set of com-petencies, goals, activities and materials. However, in few countries, media literacy has become a part of the compulsory curriculum structure within the general education system. There are also cases when policies have been adopted to encourage, through procedures of non-formal education, which prepa-res citizens to be media literate, both in regard to the reception, the analysis, and production of messa-ges in multiple formats.

Still due to inertia and resistance of educational institution system in general, and in particular in the countries with distinct and urgent political and economic priorities, it makes it difficult to pay due atten-tion to media literacy challenge. Another possible reason for this lag, lies in the belief that the effort in training teachers and students in developing skills in managing and updating information and communi-cation technology (ICT) or its more recent conceptualization, learning and knowledge technologies (LKT) comprises in itself media competence, with the result of poor training of educators in the recog-nition and mastery of the factors that make up the dimensions of media communication.

It is therefore important to document the situation in the educational structure that media literacy is in worldwide and answer questions such as: what is the current state of academic development of media literacy?, what features does a successful media literacy curriculum have (based on a specific educational level)?, what elements authorize a curriculum for media literacy education aimed at tea-chers?, is it necessary to introduce mandatory courses on media education in the curriculum?, what are the best strategies and methods to educate citizens about media?, etc.

The “Comunicar” Journal current issue shares the results of experience and research into the pos-sibilities of gradual, but consistent inclusion of programs and projects aimed at the development of media literacy. In the dossier of the monograph there are important contributions of research conducted

C

I

ntroduction

in a wide geography. They include the analysis of a set of case studies, qualitative and quanti-tative research analyzed with the phocus on the implementation of civic engagement through online activities in several regions of Portugal. Data and empirical results obtained through questionnaires were used to create a scoring system capable of reflecting school par-ticipation and strategies on media literacy and civic action online of teachers and students. The article, entitled “Media education as a strategy for online civic participation in Portu guese schools” is written by Tânia DiasFon -seca and John Potter.

Jennifer Tiede and Silke Grafe, being con-vinced that media pedagogy should be integra-ted into pre-service teacher training in order to use the media in their classrooms effectively and successfully, focus on examples of Ger -many and the US, reviewing different models of media of both countries and try pedagogical skills, through a study that measured the skills in media education of students from both coun-tries, to answer the question of whether these skills are promoted by training programs. The data allow, likewise, to identify different ways of integrating media pedagogy in teacher

ning. In addition, conclusions can be drawn about the consequences of processes involved in teacher trai-ning and media literacy.

The Nupairoj Nudee’s article entitled “The ecosystem of media literacy: A holistic approach to media education” proposes a systematic way to spread media literacy education in Thailand following the MIL competencies of UNESCO. The ecosystem is composed of the apprenticeship scheme (students, facilitators, curriculum and pedagogy), society (community, civil sector, media and parents) and politics, the purpose of which is to bring a change of behaviour among students and to have an impact on their way of life.

The investigation and analysis on out-of-school models is illustrated with the contribution of Mônica Pegurer-Caprino and Juan-Francisco Martínez-Cerdá. This article analyzes the current status of the exis-ting media literacy education in Brazil from the perspective of informal education. The situation is descri-bed through a sample of projects and organizations operating under the three internationally recognized dimensions of media education: access / use, critical understanding, and production of media content. From the data provided the study proposes a model of media literacy projects developed in the field of non-formal education.

Formal school media education is exemplified by research “Media competence of teachers and stu-dents of compulsory education in Spain”, reported by Antonia Ramirez-Garcia and Natalia

González-© ISSN: 1134-3478 • e-ISSN: 1988-3293

9omunicar,

48,

XXIV,

Fernández. This research uses a quantitative methodology to determine the levels of media competence of teachers and students of compulsory education in the six dimensions that comprise it. These levels provide a preliminary assessment of possible shortcomings and needs of educational intervention. Their observations and findings show that despite the existance of the curriculum that meets the needs of media literacy in the compulsory education and proliferate technology supporting policies, in practice one of the greatest weakness of the teachers- participants is that they tend to focus on the technological aspect. The authors suggest that a critical review of school curricula should prevent media literacy edu-cation from possible exclusion.

Number 49 of the Scientific Journal Comunicar with such a big scale international sampling, is aimed at researchers, teachers and others readers interested in the inclusion of media literacy education in plans and curricula, as well as its empowering strategies beneficial for broad social sectors and specific segments of the population.

© ISSN: 1134-3478 • e-ISSN: 1988-3293

Comunicar,

48,

XXIV,

European Researcher, 20 15, Vol.(93), Is. 4

Copyright © 20 15 by Academ ic Publishing House

Researcher

Published in the Russian Federation

European Researcher

H as been issued since 20 10 . ISSN 2219-8 229E-ISSN 2224-0 136

Vol. 93, Is. 4, pp. 331-334, 20 15

DOI: 10 .1318 7/ er.20 15.93.331 www.erjournal.ruUDC 37

Me d ia Lite racy Fu n ctio n in Critica l B lo gs

1 Alexander Fedorov 2 Anastasia Levitskaya

1 Anton Chekhov Taganrog Institute, Russian Federation Branch of Rostov State University of Econom ics

Doctor of Pedagogic Sciences, Professor E-m ail: m ediashkola@ram bler.ru

2 Taganrog Managem ent and Econom ics Institute, Russian Federation PhD, Associate professor

E-m ail: m ediashkola@ram bler.ru

Abs tra ct

The Internet is widely recognized as playing an im portant role in facilitating education on a range of issues, including m edia literacy. Analyzing the m edia critical activity of contem porary Russian bloggers, the authors of the article reveal the following reasons for popularity or, on the contrary, unpopularity of blogger's m edia criticism : targeted orientation, em otional charge, entertainm ent nature, duration, interactiveness, m ultim edia m ode, sim plicity/ com plexity of the language of a m edia text, the level of conform ity.

Ke yw o rd s : m edia criticism ; m edia education; m edia literacy; m edia com petence; analytical thinking; ethics; m edia blogger.

In tro d u ctio n

It is difficult to challenge the viewpoint that the new "hyper technological environm ent, this deepening of com m unicative globalization, has not only altered the way we perceive and use tim e and space, it has also changed the chem istry of our everyday life and our culture. This new life and cultural chem istry fostered by the acceleration of the rapid configuration of huge, changing publics is in fact generating chain reactions of an unheard of scope and com plexity that we are still far from being able to grasp. It is affecting our environm ent, our culture and also our way of being individuals, our way of fram ing ourselves as hum an beings. Perhaps we are not prepared to wholly explain the change, but we m ust exam ine it because it affects all the dim ensions of our existence. Perhaps this is an unprecedented m utation that will not only affect our environm ent but also decisively influence our psyche and our character" [Perez Tornero, Varis, 20 10 , p. 13-14].

In fact, interactive m edia, engaging their user into the creating process, thus turning him / her from a receiver/ translator into a creator of media texts, have made a real breakthrough to a personal freedom in m ass information sphere. The degree of dependence of a person from the dictate of a media message's producer has significantly decreased and the borders of choice have been broadened; the personality's status and self esteem have been raised [Korkonosenko, 2013, p. 38].

European Researcher, 20 15, Vol.(93), Is. 4

Ma te ria ls a n d m e th o d s

S.V. Ushakova (20 0 6) classified the form s of m edia contribution to the developm ent of citizens' m edia com petence. According to her, there are two groups - of direct and of indirect participation.

The form s of indirect participation include:

- self education of the audience during m edia exposure; additionally, broadening of one's com m unicative experience;

- enhancem ent of the audience's m edia com petence due to its cooperation with m edia agencies as freelance correspondents, sources of journalistic inform ation, and/ or participants of television/ radio program s;

- release of periodicals and TV/ radio program s by a m edia center in an educational institution/ club/ com m unity center;

- blogging - publishing discussion or inform ational posts on the World Wide Web; - "self-press" - participation in publication of alternative (inform al) periodicals;

- public, out-of-editorial body com m unication of journalists and other m edia sphere specialists with representatives of the audience (in the form of special events, journalists' m eetings with public, television audiences, etc.).

In contrast, the form s of direct participation include:

- m edia education publications and program s in m ass m edia;

- m edia journalists/ m edia critics articles, containing analysis, interpretation and evaluation of the contents of m ass m edia and the issues of their functioning in society;

- publishing periodical TV guides and film guides, targeted at the m ass audience and aim ed at the developm ent of basic abilities to perceive and evaluate audiovisual m edia texts (facilitated by reading publications, related to the analysis of TV program s and film s);

- publishing syllabi, lesson plans and other m aterials produced by public m edia m onitoring organizations and m edia activists - representatives of civic society;

- sections and colum ns in m ass m edia aim ed at m aintaining the feedback with the audience, and explaining the "inside" journalism policy of collecting, evaluating, and verifying the inform ation;

- om budsm en's colum ns, inquiring into disputable cases of journalism [Ushakova, 20 0 6]. Whereby, speaking about professional media criticism, the peculiarity of the current situation is connected to the fact that some media critics, actively involved in press, also successfully collaborate with electronic media as well, thus television criticism begins to acquire some synthetic forms, uniting political analysis and dismantling internal corporate problems, political bias and the independent view, theoretical analysis of the form and method, and superficial, tabloid-tinted simplistic view [Gureev, 2004].

One would think that such active media critics as Dmitry Bykov, working nearly 24/ 7 in press, on TV and on the Internet, would fully get hold of the audiences' attention. However it is not happening - there are quite a few m edia bloggers on the Internet who sometimes attract even more readers.

Co n clu s io n s

Why is bloggers' m edia criticism popular?

We suggest the following reasons for popularity or, vice versa, unpopularity of bloggers' m edia criticism :

1) Targeted orientation: media texts of popular bloggers may be aimed at a broad audience (thus potentially popular) or at a narrow circle, joined by thematic or other interests. Professional m edia critics' texts, apart from being targeted at a wide audience, may be corporative, that is "can influence comparatively sm all, but strategically important groups of audiences (journalists and top media managers, teachers and students of journalism schools, working journalists, researchers in various fields of social studies and humanities, and social activists), empowering them with new ideas and approaches, new vision of common problems of media functioning" [Korochensky, 20 03, p.33].

2) Duration: popular m edia bloggers' texts are usually short, and professional m edia critics' texts, on the contrary, often require prolonged reading/ listening, that, evidently, discourages the concentration of an im patient part of the audience with a short attention span (especially, the young); 3) Interactiv eness, m ulti-m edia m ode: popular m edia bloggers' texts are often interactive. Short texts are accom panied by photographs, video clips, links to other sites, etc. On the other hand, professional m edia critics' texts, even on the web, resem ble the form at of print press;

European Researcher, 20 15, Vol.(93), Is. 4

4) Language. Popular m edia bloggers' texts are written in plain, understandable for a wide audience, language; often without a deep analysis and logical structure. Meanwhile professional m edia critics' texts are well structured, logical, and often aim ed at m edia com petent readers who are aware of the social and cultural context of the issue, understand m edia language, and specialized m edia term s, know the functions of m edia agencies, m anipulative effects, the creative work of m edia professionals, and so on.

5) Em otional charge. The texts written by m edia bloggers, in general, are clearly em otionally charged. They som etim es contain sharp, straightforward judgm ents and com m ents, while professional m edia critics' texts are characterized by the understatem ent, som etim es am bivalent, (im plicitly) ironic, reasonable, argum entative evaluation of the ethical, aesthetic and other categories. Moreover, the m edia critics of older generation often act in the spirit of "enlightenm ent" and developm ent of good taste in their audience.

6) Entertainm ent. Popular m edia bloggers' texts frequently exploit the entertainm ent function, while professional m edia critics' texts are occasionally too serious, or even pom pous.

7) Conform ity . On the one hand, non-conform ist texts of m edia bloggers com m only oppose any authority, criticize m edia personalities of any scale and position. On the other hand, professional m edia critics avoid any personal attacks, they tend to use apophasis, they do not break social taboos. That said, we encounter that both bloggers and professional journalists frequently break social norm s [Muratov, 20 0 1], and are not shy to use abusive lan guage, including obscene lexis, in their political propaganda statem ents.

What does the above-said m ean for the m edia education practice? In this sense, it im plies that besides the m ass com munications theory, the syllabi for m edia teachers' pre-service or in-service education should include theoretical units on non-m ass m ediated com m unication - ranging from auto-m edia com m unication and interpersonal com m unication to in-group and intergroup m edia com m unication. This theoretical background should becom e a starting point for the developm ent of the new fram ework of media education both in schools and universities [Sharikov, 20 12]. Bloggers' m edia texts m ay becom e a useful teaching and learning tool for a modern teacher, the sam e as traditional m edia texts, created by professionals working in press, on television, and on radio.

Ackn o w le d ge m e n t

The article is written within the fram ework of a study supported by the grant of the Russian Science Foundation (RSF). Project № 14-18 -0 0 0 14 "Synthesis of m edia education and m edia criticism in the preparation of future teachers", perform ed at Taganrog Managem ent and Econom ics Institute.

Re fe re n ce s :

1. Gureev, M. Does m odern television criticism exist? / / Culture. 2004. № 44.

2. Korkonosenko, S.G. J ournalism education: the need for pedagogical conceptualization / / International journal of experim ental education. 2013. №1, pp. 38-41.

3. Korochensky, A.P. M edia criticism in the theory and practice of journalism . Ph.D. dis. St.Petersburg, 20 0 3.

4. Muratov, S.A. TV - the evolution of intolerance. Moscow: Logos, 20 0 1. 240 p.

5. Sharikov, A.V. On the need for reconceptualization of m edia education / / M edia Education. 2013. № 4.

6. Ushakova, S.V. The role of journalism in the developm ent of m edia culture of the audience / / Journalism and M edia Education in the X X I century . Belgorod: Belgorod State University, 20 0 6.

European Researcher, 20 15, Vol.(93), Is. 4

УДК 37

Медиаобразовательная функция блогерской медиакритики

1 Александр Федоров 2 Анастасия Левицкая

1 Таганрогский институт имени А.П. Чехова, Российская Федерация Доктор педагогических наук, профессор

E-m ail: m ediashkola@ram bler.ru

2 Таганрогский институт управления и экономики, Российская Федерация Кандидат педагогических наук, доцент

E-m ail: m ediashkola@ram bler.ru

Аннотация. Анализируя медиакритическую деятельность современных российских

блоггеров, авторы статьи выявили следующие причины популярности или, наоборот, непопулярности блоггерской медиакритики: целевые ориентации, эмоциональность, развлекательный характер, продолжительность, интерактивность, мультимедиахарактер, простота/сложность языка медиатекста.

Ключевые слова: медиа; медиакритика; медиаобразование; медиаграмотность;

медиакомпетентность; аналитическое мышление; этика; средства массовой информации; блоггер.

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

82

Matej Bel University, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia Has been issued since 2014

ISSN 1339-6773 E-ISSN 1339-875X

Narrative Analysis of Media Texts in the Classroom for Student Audience

Alexander Fedorov

Anton Chekhov Taganrog Institute, branch of Rostov State University of Economics, Russian Federation

Prof. Dr. (Pedagogy)

E-mail: [email protected]

Abstract

The author analyzes the features of the narrative analysis of media texts on media education classes in the university. The paper also provides examples of creative problems and issues associated with this type of narrative analysis in the context of media education problems, ie based on six key concepts of media literacy education: agency, category, language, technology, audience, representation. The author argues that the narrative analysis of media texts on media education classes can significantly develop media competence of students, including critical thinking and perception.

Keywords: narrative analysis, media, media texts, media education, media literacy, media competence, students.

Introduction

Narrative Analysis is the analysis of the plots of media texts. This analysis is closely related with the structural, mythological, and other types of semiotic analysis of media and media texts [Barthes, 1964; 1965; Berelson, 1984; Gripsrud, 1999; Eco, 1976; Masterman, 1984; Propp, 1998; W.J. Potter [Potter, 2014], A. Silverblatt [Silverblatt, 2001; 2014].

Media literacy education offers a variety of creative ways to develop students‟ capacities for the analysis of story / narrative concepts (plot, scene, topic, conflict, composition and others). In general terms, these methods can be divided into: 1) literary simulations works (writing applications for the scenario, writing mini scenario of media texts); 2) theatrical-role works (dramatization of various episodes of media texts, the process of creating a media text, etc.); 3) image simulation (create posters, collages, drawings on the themes of culture media, etc.). Imitation is a very popular method of learning media, and simulation is a form of role-playing games: it attracts students and gives them the opportunity to be the creators of media texts [Buckingham, 2003, p.79], because students do not play the role of cineastes, journalists or advertisers: they are cineastes, journalists or advertisers. And even though students‟ achievements can be amateurish, they involved in the decision-making processes [Craggs, 1992, p.21].

Narrative analysis of media texts implies a number of creative tasks (part of these tasks is available at: BFI, 1990; Semali, 2000, pp.229-231; Berger, 2005, p.74; Nechay, 1989, p.265-280; Usov, 1989; Fedorov, 2004, p.43-51; Fedorov, 2006, p.175-228, however, the cycle of tasks I substantially supplemented and revised): literary simulation, drama, role-playing, image simulation. Each of these tasks includes analysis of the key concepts of media literacy education (media agencies, media categories, media language, media technologies, media representations, media audiences, etc.).

Materials and methods

Cycle of literary simulation tasks for the narrative analysis of media texts in the classroom at the student audience:

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

83

- writing the application for original screenplay (scenario plan) of media text (any types and genre) followed his suggestion producers of hypothetical media company;

- drawing up of the producer‟s plan for media project. Media / media text categories:

- writing the original text (in the genres of articles, reports, interviews, etc.) for a newspaper, magazine, internet publication;

- writing the same plot synopsis in the different media genres. Media technologies:

- development plan of technological methods that will be used in the scenario of a media (film, radio / television program, computer animation, etc.).

Media languages:

- writing the shooting mini-script of a media (film, radio / television program, computer animation, etc.):camera angles, camera movements, installation techniques, etc.

Media representations:

- writing of the mini-scenario for one of episode from famous book;

- writing of mini-scenario for one of episodes from your own application for the original script;

- writing of the mini-scenario for the original product media culture (for example, the plot for approximately 2-3 minutes of video action);

- create annotations and scenarios for advertising media texts; - writing of the messages for TV-news, related to the case of your life; - writing the story for the sequel of well-known media text;

- preparing newspaper website with stories, that are associated with events of your life or the lives of your friends and acquaintances.

Media audiences:

- use the same plot for the scenario, designed for audiences of different ages, education level, ethnicity, socio-cultural environment, etc.

Thus, the audience develops in practice (with the creative literary and performing simulation tasks), such important concepts of narrative analysis of media texts as an idea, topic, scenario, synopsis, plot, conflict, composition, script, screening, etc., without separate study of so-called “means of expression.”

Of course, each such occupation is preceded by introductory remarks by the teacher (on goals, objectives, and course assignments). The majority of literary and simulation tasks are perceived audience is not just an abstract exercise, but have a real prospect for practical implementation in a further series of training sessions.

Students‟ mini-scenario, episodes for hypothetical films; structural and thematic plans for hypothetical magazines and newspapers, radio / TV programs, interactive sites can be submitted for collective discussion, the best ones are selected for further media literacy works.

In this assignment, students should imagine that mini-scenario can be realized only for the subjects that do not require bulky accessories, complex scenery, costumes, makeup, etc. However, the scenario‟s fantasy is not limited to: students can develop any fantastic, unbelievable stories and themes. But for video shooting understandably, purely practical reasons, only those selected scenario development, which could be used without too much difficulty, for example, in the class room, or to the nearest street.

Step by step, the audience on their own experience becomes aware of the role of the author-screenwriter in the creation of media texts, the basics of narrative works of media culture. The main indicator of the literary and performing simulation creative tasks: the student's ability to formulate briefly their scenic designs, verbally disclosing audiovisual, space-time image of a hypothetical media text.

Thus, students increase the level of their media competence on the basis of practice developing of creative potential, critical thinking, and imagination.

Cycle of theatrical role-creative tasks for the narrative analysis of media texts in the classroom at the student audience:

Media agencies:

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

84

Media / media text categories:- dramatization of the media text episode with the same story line, but in a format different media genres.

Media technologies:

- dramatization of the implementation of various technological methods that are used in the scenario of a media text (film, radio / television program, computer animation, etc.).

Media languages:

- shooting short movie (duration: 2-3 min.) using different techniques of visual and sound solutions;

Media representations:

- dramatization on acting roles performed by students: the characters must be close to the plot of an episode of a particular media text. Work is proceeding in groups of 2-3 people. Each group prepares and puts into practice your game project of the plot of the episode of a media text. The teacher acts as a consultant. The results are discussed and compared;

- interview (various options for interviews with various imaginary media text person and characters);

- dramatization of “press conference with the "author" of media text” (imaginary writer, director, producer and others.);

- dramatization of interviews with imaginary “foreign persons of media culture” (can be in foreign languages);

- dramatization of imaginary “international meeting of media criticism”: discussions about various topics related to the subjects of media texts, analyze the plot, etc.;

- casting (casting of the characters or actors of media texts); - shooting a video short movie or TV show.

Media audiences:

- use the same plot for theatrical sketches on the theme of hypothetical media texts, designed for audiences of different ages, education level, ethnicity, socio-cultural environment, etc.

Naturally, all the above work collectively discussed and compared.

In fact, the role creative activities complement and enrich the skills acquired by the audience during the literary simulation workshops. In addition to the practical immersion in the logic of the plot structure of a media text, they promote emancipation, sociability audience, make it looser students, and activate improvisational abilities.

The disadvantages of some role-playing activities can probably be attributed quite a long stage of preliminary preparation of the audience who want to get into the role of “author”, “journalists”, etc.

Cycle of graphic creative tasks for the narrative analysis of media texts in the classroom at the student audience:

Media agencies:

- preparation of a series of cards, drawings, which could relate to the main stages of the creation of a media text in the studio / edition.

Media / media text categories:

- preparation of a series of cards, drawings, which could relate to the implementation of the same plot in media texts of different genres.

Media technologies:

- preparation of a series of cards, drawings, which could relate to the implementation of the same plot of a media text using different technologies.

Media languages:

- preparation of a series ofpictures that could be used as a basis of a plot to shoot fight scene, for example, in the western or detective (with support for various types of crop - the general plan, close-up, detail, etc.).

Media representations:

- preparation of a series of pictures / cards that might correlate with the plot of a media text; - creation of a posters, collages, drawings on the themes of various media texts;

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

85

Media audiences:- preparation of a series of pictures that visually would disclose various emotional reactions in the perception of media texts audiences of different ages, education level, ethnicity, socio-cultural environment, etc.

Cycle of literary and analytical creative tasks aimed at developing the skills of audience for narrative analysis of media texts in the classroom:

Media agencies:

- analysis of factors, causes, which may affect the agency change the original story, the narrative skills.

Media / media text categories:

- analysis of the factors that may affect the transformation scenes in media texts, depending on specific genres.

Media technologies:

- analysis of the factors that may affect the transformation scenes in media texts depending on the specific technology chosen for their implementation;

Media languages:

- analysis of promotional posters of media texts in terms of reflecting them in the narrative media text;

- analysis of possible audiovisual, stylistic interpretations of the same plot of a media text. Media representations:

- creating a “time line” to show the sequence of events in media text;

- modeling (in tabular / structural form) of narrative stereotypes of media texts (characters, a significant change in the lives of the characters, problems encountered, solutions to the problem, the solution / return to stability); revealing the narrative structure of a particular episode of a media text;

- selection of thesis from the point of view of the student, truly reflects the logic of the plot of a media text;

- selection of media text abstracts in order of importance for the understanding and description of the narrative structure of a media text;

- separation of media text blocks on the plot. Attempt to interchange these blocks and, consequently, the creation of options for changing the course of events;

- understanding of the mechanism of “emotional pendulum” in the media text plot (alternation of episodes that cause positive and negative emotions of the audience);

- acquaintance with the first (or final) episode of a media text, followed by an attempt to predict the future (past) events in the story;

- analysis of stereotypes in particular genre of media texts;

- analysis of the relationship between significant events and characters in the media texts; - analysis of the plot of a media text on a historical theme, based on documentary evidence. The study of regional geographic, political and historical materials relating to the subject and the time period. Comparison of the studied material depicting historical events in the story of a particular media text;

- identification plot stereotypes image of the country, nation, race, nationality, social structure, political governance, the justice system, education, employment, etc.;

- comparison of reviews and discussion (articles, books about media texts) in professional media criticism, and journalism;

- preparing essays devoted to the peculiarities of narrative in media texts;

- students‟ reviews about the media texts of different types and genres (with emphasis on the analysis of the plot).

- group discussions (with the help of problem questions of the teacher) about plots of media texts.

Media audiences:

- analysis of media perception typology of same media stories for audience of different age, education level, ethnicity, socio-cultural environment, etc.

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

86

work as a whole; analysis of logic thinking of authors in the plot of a media text (in the development of conflicts, characters, ideas, audio-visual, spatial images, etc.).

Concludes with a discussion of problem-test questions, affecting the utilization of the audience received a plot of a media text analysis skills (for example: "What are the known media texts stories you can compare this story? Why? What do they have in common?", etc.).

Classes for the formation of skills of analysis of media texts‟ plots aimed at training the memory, the stimulation of creative abilities of the individual, on improvisation, independence, a culture of critical thinking, the ability to apply this knowledge in new pedagogical situations, the reflections on the moral and artistic values, etc. etc.

Methodical implementation of these steps based on a cycle of workshops devoted to the analysis of specific media texts.

However, as my experience shows, it is necessary, first, to go from simple to more complex: first choose to discuss, analyze of the plot, the author's thoughts, the style of media texts. And secondly aim:to take into account the genre, thematic preferences of the audience.

Using creative, game, heuristic and problem tasks, significantly increasing the activity and interest of the audience. Heuristic form of the class, in which the audience is invited to a few wrong and right judgment, much easier for the audience analytical tasks and serves as a first step to subsequent gaming and problematic forms of media texts discussion.

During the implementation of heuristic approaches methodology of training audiences include:

- true and false interpretations of the story on the material of a particular episode of a media text;

- right and incorrect versions of the author's conception, reveals in a particular media text. Such a heuristic form of employment is particularly effective in the classroom with low media competence, with mild personality beginning and independent thinking. This audience will undoubtedly need "support" theses on the basis of which (plus own additions, etc.) can be formulated as a particular analytical judgment.

Critical analysis of media texts stories also connected with an acquaintance with the works of critics' community professionals (reviews, theoretical articles, monographs devoted to media culture and specific media texts), in which the audience can judge the different approaches and forms of this type of work.

The audience is looking for answers to the following problematic questions:

- What media critic opinion about the advantages and disadvantages of the media text? - How deep reviewers penetrate the author's intention?

- Do you agree or not with this or that estimates reviewers? Why Are?

- Do this reviewer has the individual style? If yes, what is it manifests itself (style, vocabulary, accessibility, irony, humor, etc.)?

- Why the author has constructed story composition of his media text so and not otherwise? Performing creative tasks related to the plot analysis of media texts, student Paul D., for example, composed entirely convincing imaginary interview with a famous director. Student Natalya B. created the interesting texts on subjects of continuing a newspaper article about a woman who has lost her memory at the accident. Student Sergei S. wrote several short stories in a variety of genres (comedy, romance, thriller, etc.).

Student Anna V. in his creative work moved the action comedy "Operation "Y" in the fantastic future on one of the planets of distant galaxies. Student Irina K. suffered another action comedy "Prisoner of the Caucasus" in contemporary America. Student Eugene V. transformed the comedy "Home Alone" into a dark bloody drama...

Questions for narrative analysis of media texts [Buckingham, 2003, pp.54-60; Silverblatt, 2001, pp.107-108; Fedorov, 2004, pp.43-51; Fedorov, 2006, pp.175-228]:

Media agencies:

- What agency / communicatorwants to make you feel in specific scenes of the story? - Why creators of media text want you to feel this?

Media / media text categories:

- What stereotypical stories, storylines conventions specific to the genre?

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

87

- Is it possible creating of media text without the dramatic conflict?

- As a genre is refracted in the plots of specific persons of media culture (the same genre in plots of different figures of media culture, different genres of stories in the works of the same person of media culture)?

Media technologies:

- How different media technologies used in the development of plots of specific figures of media culture (for example, different technologies in the development of plots of the same person of media culture)?

Media languages:

- Are audio-visual, stylistic features of a media text depend on whether or not from the concrete plot? If so, how?

Media representations:

- What is the significance for the understanding of the plot is called a media text?

- What is the relationship between significant events and characters in the story of a media text?

- What are the causes of action, the characters' behavior?

- What the characters have learned as a result of their experiences gained in the development of a media story?

- What events occur in the complication of the plot of a media text? What that tells us about a media text?

- Do you trust this media text? If not, what prevents your trust? - Can you identify the secondary storylines?

- Are there any links between secondary storylines that help to understand the world, the characters and themes of media text?

Whether the final set in the logic complication of the plot, the logic of the characters and their world?

Media audiences:

- What is your emotional response for the media text?

- Does your emotional reactions understanding your personal value system?

- What types of media text stories, in your opinion, cause difficulties in the perception of a mass audience?

Conclusions

So I presented the main path for the narrative analysis of media texts on media education classes in the university, including the examples of creative problems and issues associated with this type of narrative analysis in the context of media education problems, ie based on six key concepts of media literacy education: agency, category, language, technology, audience, representation. I suppose that the narrative analysis of media texts on media education classes can significantly develop media competence of students, including critical thinking and perception.

References:

1. Barthes, R. (1964). Elements de semiologie. Communications, N 4, pp. 91-135. 2. Barthes, R. (1965). Mythologies. Paris: Editions de Seuil.

3. Berelson, B. (1954). Content Analysis in Communication Research. New York: Free Press, pp. 13-165.

4. Berger, A.A. Seeing is believing. Introduction to visual communication. Moscow: Williams, 2005. 288 p.

5. BFI. Film Education. Moscow, 1990. 124 p.

6. Buckingham, D. (2003). Media Education: Literacy, Learning and Contemporary Culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 219 p.

7. Craggs, C.E. (1992). Media Education in the Primary School. London – New York: Routledge, 185 p.

8. Eco, U. (1976). A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

European Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 2015, Vol.(6), Is. 2

88

10. Fedorov, A.V. Specificity of media pedagogical students // Pedagogy. 2004. № 4, pp.43-51.

11. Gripsrud, J. (1999). Understanding Media Culture. London – New York: Arnold & Oxford University Press Inc., 330 p.

12. Masterman, L. (1984). Television Mythologies. New York: Comedia.

13. Nechay, O.F. Film education in the context of fiction // Specialist. № 5. 1993, pp. 11-13. 14. Nechay, O.F. Fundamentals of Cinema Art. Moscow: Education, 1989, pp. 265-280. 15. Propp, V.Y. Folklore and Reality. Moscow: Art, 1976, pp.51-63.

16. Propp, V.Y. The morphology of the fairy tale. The historical roots of the fairy tale. Moscow: Labirint, 1998. 512 p.

17. Semali, L.M. (2000). Literacy in Multimedia America. New York – London: Falmer Press, 243 p.

12

Available online at www.jmle.org

The National Association for Media Literacy Education’s

Journal of Media Literacy Education 7(2), 12 - 22

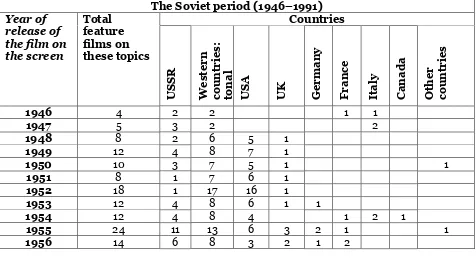

Soviet Cineclubs: Baranov’s Film/Media Education Model

Alexander Fedorov,

Anton Chekhov Taganrog State Pedagogical Institute

Elizaveta Friesem,

Temple University

Abstract

In this paper we analyze a historical form of media literacy education that is still insufficiently discussed in English-language literature: Russian cineclubs. We focus on one particular cineclub that was created by a Soviet educator Oleg Baranov in the 1950s. We describe this cineclub’s context and structure, and discuss its popularity among students. The content of Baranov’s classes might have been shaped by ideological requirements of the time. However, we believe that the structure of his model can be used as an inspiration for a media literacy club in today’s schools globally, and not only in Russia.

Keywords: film, education, critical thinking, ideology, film clubs, Russia, Soviet, history

According to the definition of the National Association for Media Literacy Education, “[t]he purpose of

media literacy education is to help individuals of all ages develop the habits of inquiry and skills of expression

that they need to be critical thinkers, effective communicators and active citizens in today’s world” (Core

Principle of MLE, n.d.). Many European countries, as well as Russia, use the definition of media literacy

education formulated by UNESCO which states that “[i]nformation and media literacy enables people to

interpret and make informed judgments as users of information and media, as well as to become skillful creators

and producers of information and media messages in their own right” (Media and Information Literacy, n.d.).

What these and many other definitions of media literacy education share is the focus on teaching audiences to

critically engage with media messages (e.g. Fedorov, 2012; Buckingham, 2003; Hobbs, 1998; Masterman,

1985; Potter, 2004). Thus, it should not come as a surprise that many activities in media literacy classes involve

interactions with media texts. Students discuss films, TV programs, commercials, music videos, magazines, and

websites while the teacher provides examples and questions (Hobbs, 2011). Sometimes young people also

create media texts to express their voices using the power of the media (Goodman, 2003).

We argue that the emergence of media literacy education can be traced back to the days when educators

started to encourage their students to critically analyze media texts, which happened when popular media began

to play increasingly important role in people’s lives. The goal of these educators was often to protect audiences

from negative effects of entertainment culture, which seemed to sway the masses in the beginning of the

twentieth century (Ortega-y- Gasset, 1985 [1930]). For example, the U.S. film education movement in the

1930s “consisted of a series of efforts to regulate the conditions and effects of film viewing” (Jacobs, 1990, p.

29). The goal of these efforts was not to develop critical thinking skills in the way media literacy educators

understand them today (Hobbs, 2011), but to protect people from the dangerous influence of entertainment

media (Leavis & Thompson, 1977 [1933]; Macdonald, 1962).

A. Fedorov & E. Friesem / Journal of Media Literacy Education 7(2), 12 - 22

13

Educational cineclubs in U.S.S.R. had much in common with the film education courses described by

Jacobs (1990). In both cases, one of the main goals was to teach the appreciation of “better” films and to

influence audiences’ tastes (Baranov, 1968). Cineclubs were recreational and/or educational clubs where

participants gathered to watch and discuss films. They were not an exclusively Russian phenomenon. The first

cineclubs (сiné-clubs) appeared in France in the beginning of the twentieth century, soon after the cinema was

invented. A variety of educated people who loved cinema gathered in these clubs to watch and discuss

experimental films of the French avant-garde, which were unavailable in ordinary cinema theaters (Hoare, n.d.;

Martineau, 1988; Pinel, 1964). Soon, similar clubs appeared in other European countries, such as Great Britain

and Belgium (Geens, 2000).

In the U.S.S.R., cineclubs emerged in the 1920s. Soviet cinema theaters of the time mostly showed

entertainment movies, many of them imported from European countries. The U.S. Soviet cineclubs initially

offered spaces where people could watch films that were difficult or impossible to find; in this sense, they were

similar to European сiné-clubs. Later, the number of their purposes expanded. They began to be used for

political propaganda, entertainment, research, and education – to improve popular tastes in films (Penzin, 1987).

As media literacy scholars, we are primarily interested in the educational application.

In this paper, we focus on one educational cineclub that was created in the end of the 1950s by Oleg

Baranov in a school of Tver/Kalinin, a Russian town located between Moscow and St. Petersburg. We chose

this cineclub because of the role that Baranov has played in Soviet/Russian film (later media) education (Penzin,

1987). When he started this cineclub, Baranov was a physics teacher with a passion for developing young

people’s aesthetic taste and moral values through cinema. Soon he became known as one the first film educators

in the U.S.S.R., and the author of a successful film education model. Baranov’s model (also known as the

Kalinin/Tver model) was based on the spiral approach (Harden, 1999) – reiterative teaching with levels of

difficulty increasing from elementary to middle to high school. Activities in this cineclub included not only

viewing and discussing films, but also a variety of games, trips to film studios, correspondence with actors and

film directors, media production (short films, wall newspaper), maintenance of a cinema museum, and

peer-to-peer teaching (Baranov, 2008b). This model inspired Baranov’s colleagues (Monastirsky, 1995; Penzin, 1987)

and helped this pedagogue to maintain the popularity of his cineclub among students for almost two decades.

Baranov has authored numerous books and articles where he describes his educational practices and the success

of his cineclub (e.g., 1967, 1973, 1979, 2008a, 2008b).

On the following pages, we offer a detailed description of Baranov’s model and explain its relevance for

media literacy education today. Baranov’s focus on cultivating in his students an understanding of the difference

between high cinema art and mindless entertainment (Baranov & Penzin, 2014) might be not be considered

media literacy education by some scholar who emphasize inquiry-based approach and independent thinking

(Hobbs, 1998). We admit that the content of Baranov’s classes might have been rooted in and shaped by

ideological requirements of the time. However, we believe that the structure of his model can be used as an

inspiration for a media literacy club in today’s schools globally, and not only in Russia.

At the time when Baranov created his cineclub, films were one of the most popular kinds of media texts.

Today, this is not the case. To be relevant, a modern media literacy club would need to include not only films,

but also TV programs, video games, Internet websites, advertising, social networks, and other types of media.

Such a club, engaging students on all stages of a school program, attracting them with exciting activities and

thrilling opportunities, could offer an alternative to stand-alone media education courses (which largely remain

an ideal in the rigidly-structured U.S. school system), integrated media literacy education (see Hobbs, 2007;

Masterman, 1985), and short-term (often extracurricular) initiatives (e.g., Friesem, 2014; Irving, Dupen, &

Berel, 1998; Scharrer, 2006).

Terms and Sources

A. Fedorov & E. Friesem / Journal of Media Literacy Education 7(2), 12 - 22

14

mediaobrazovanie

, which is literally translated as media education. In the period from the 1950s to the 1980s,

when Baranov’s cineclub existed, Russian academic and education literature did not mention media education in

their writings. Rather, Soviet scholars and practitioners of the time usually talked about film education

(

kinoobrazovanie

), defined as education about and through the cinema. The term film education in Soviet

literature was first used by Oleg Baranov, whose cineclub is in the focus of this paper (Baranov, 1967).

As far as we know, Soviet educators had little access to academic works outside of their country.

Therefore, we believe that the term film education did not appear because of the Western influence. In his

works, Baranov does not talk about film education efforts outside of the U.S.S.R. and it is likely that he was not

aware of them. We assume that educators within and outside of the U.S.S.R. developed the idea to teach film

appreciation independently from each other. As for media education, this term eventually came to the U.S.S.R.

in the 1980s, when more academic literature from outside of the Soviet Union started to penetrate the Iron

Curtain (Sharikov, 1990).

Many Soviet cineclub theorists initially defined themselves as film educators and their field as film

education. Since the 1980s, they started to use terms media education and film education interchangeably

(Baranov, 2008). As the shift in terminology occurred when cineclubs already existed, we use the term

film/media education in order to reflect this change.

For this study we reviewed a number of Russian-language sources on cineclubs and film/media

education in the U.S.S.R. We used works of several key film/media educators, such as Penzin (1987),

Rabinovich (1969), Monastirsky (1995), and Levshina (1978). Penzin (1987) has been a prominent Russian

film/media educator for over three decades. He was one of the first Soviet educators who systematized the

theory of film education and cineclubs in the U.S.S.R. Rabinovich (1969) has worked in the area of film

education since the 1950s, and later became one of the leading authorities of media education in the U.S.S.R.

Monastirsky (1995) has studied cineclubs since the 1970s, and created his own cineclub in Tambov. Levshina

(1978) is a renowned cinema critique and educator. All these authors have worked in the field of film/media

education alongside Baranov, the author of the model we discuss on the following pages. They witnessed the

popularity of his cineclub and described it in their works. Some of them even collaborated with Baranov. Penzin

and Baranov still co-author works on theory and practice of film/media education (Baranov & Penzin, 2014).

Last but not least, in our analysis we used several works by Baranov himself (e.g., 1967,

1973, 1979, 2008a, 2008b). Over the five decades of working in film/media education, Baranov wrote an

impressive amount of articles and books on the role of the cinema in aesthetic and moral education of youth. For

this study, we were particularly interested in Baranov’s works where he described the history and structure of

his famous cineclub.

Historical Context and Structure of

Soviet Cineclubs

The first cineclubs appeared in Russia in the 1920s. As soon as in 1925, the Soviet government

recognized the value of cineclubs for the propaganda of communism and created the Society for Friends of the

Soviet Cinema (SFSC), whose board of directors included such prominent Soviet cinematographers of the time

as Sergei Eisenstein. SFSC started to use cineclubs for introducing ideology-laden films to Soviet audiences

(Maltsev, 1925).

A. Fedorov & E. Friesem / Journal of Media Literacy Education 7(2), 12 - 22

15

against the Tsarist regime represented by cruel officers. The film

Mother

encourages the viewer to sympathize

with the plight of a woman who is trying to help her son to fight against the unfair and ruthless Tsarist regime.

Cineclubs served for promotion of these and other ideological films, which were usually less popular among the

public than entertaining cinema hits of the time (Ilyichev & Nashekin, 1986).

SFSC made sure that most Soviet cineclubs of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s watched films

approved by the government. Although during this period discussing political aspects of screened films was not

explicitly prohibited, cineclub-goers understood very well that not all opinions could be openly expressed

(Monastirsky, 1995). As Stalin started gaining power in the end of the 1920s, the situation got worse.

Expressing dissident opinions could lead to arrest, a concentration camp, or even execution. In 1934 Stalin

closed the Society for Friends of the Soviet Cinema. One can assume that discussions about the communist

ideology in cineclubs led to more reflection than the government could tolerate (Zalessky, 2009).

From 1935 to the mid-1950s cineclubs virtually did not exist in Russia (Stalin died in

1953). The cineclub movement started to re-emerge only during Khrushchev’s thaw – a period from the

mid-1950s to the early 1960s when political repression and censorship were partially reversed and the communist

regime softened. New cineclubs were in many ways similar to the pre-Stalin ones. The government was still

pushing cineclub organizers to use films for communist propaganda. At the same time, the focus on aesthetic

qualities remained prominent (Monastirsky, 1995). Combining these two functions, cineclubs were increasingly

seen as a place of aesthetic and moral education for Soviet youth.

The sociocultural situation in Russia from the end of 1950s until the middle of the 1980s contributed to

the popularity of cineclubs, especially among young people. During this period, there was no organization like

SFSC that would directly control cineclubs; thus, cineclub organizers could combine ideological films with

popular and art house movies. Films were still seldom shown on TV, and the number of television channels was

limited (Vladimirova, 2011). Despite the effects of Khrushchev’s thaw, censorship persisted, in particular in

relation to the information about the “West.” Audiences also felt the lack of access to films of some cult

directors whose work the government did not favor (e.g., Tarkovsky and Parajanov). The screen of some

cineclubs offered to Soviet cinema lovers an access to this censored and desired material.

During Khrushchev’s thaw, cineclubs appeared in so-called palaces of culture (establishments for

recreational activities such as cinema watching, singing, dancing, and theater), as well as in many cinema

theaters, schools, and colleges. The target audience of U.S.S.R. cineclubs of the 1950s-1980s was primarily

youth, especially students (Monastirsky, 1995). Films for cineclubs – including Soviet and “Western” movies –

were selected according to their perceived artistic value, although ideological requirements of the time also had

to be taken into consideration. Cineclub organizers had a variety of goals: to provide a venue for recreation, to

promote ideological films, to give access to films that were seldom screened in commercial cinema theaters,

and/or to educate people by developing their tastes (Ilyichev & Nashekin, 1986).

Two main activities in post-thaw cineclubs were, predictably enough, watching films and discussing

them. Typically, before the screening, the head of the cineclub or one of its participants made a short

introduction to tell the audience about the time the film was created, its scriptwriter, director, photographer,

composer, and actors. Following the introduction, participants watched the film and discussed it for 30-40

minutes (Penzin, 1987).

A. Fedorov & E. Friesem / Journal of Media Literacy Education 7(2), 12 - 22

16

Baranov and His Film/Media Education Model

Oleg Baranov was born in 1934. He graduated from Kalinin Pedagogical University in 1957, the same

year that he started working in the Internat-school #1 (the equivalent of a foster home) as a physics teacher and

founded his soon to be famous cineclub. In 1965, Baranov started combining teaching at the Kalinin State

University with his work at school. In 1967, the pedagogue described the history of his cineclub and the theory

behind it in his first book (Baranov, 1967). In 1968, he finished graduate studies at the All-Union State Institute

of Cinematography. He was one of the first Soviet scholars to defend a dissertation in film education (Baranov,

1968). In 1971, Internat-school #1 was closed, and Baranov moved his cineclub experiments to several other

schools in Kalinin. After his last school cineclub was closed in 1984, the by then renowned scholar focused on

teaching in the Kalinin (Tver after 1990) State University. While there, he served for many years as chair of the

Pedagogy Department. During his pedagogical career, Baranov made more than forty presentations at academic

conferences and published more than eighty scholarly works. His model of film/media education (the

Kalinin/Tver model) has been famous among Russian film and media educators for several decades.

The first cineclub, which Baranov started in 1957, shared a number of characteristics with similar

educational cineclubs of the time. It aimed to develop students’ aesthetic taste and moral values by focusing

their attention on what Baranov deemed to be the best examples of cinema art. The cineclub also emphasized

the importance of growing young people’s knowledge base about the cinema by helping them memorize facts

about films, actors, and directors using a variety of activities. Bearing in mind these similarities, here we would

like to focus on characteristics that made Baranov’s cineclub unique.

Baranov’s model, which he started to develop through trial and error as soon as he opened his first

cineclub, was characterized by several features. In his cineclub, Baranov used a spiral approach to teaching,

which emphasized students’ independent work, peer-to-peer learning and the combination of various activities:

memory games, media production (short videos and wall newspaper), trips to famous cinema studios,

communication with prominent cinema personalities (in person and through letters), staging scenes from

popular films, and maintaining a cinema museum. We describe this structure and some of the activities in more

detail below.

The cineclub existed in the Internat-school #1 until 1971, when Baranov moved his film education

project (including the museum) to several other schools in Kalinin. This second stage of Baranov’s cineclub

lasted from 1972 to 1984. Starting from the middle of the 1980s, cineclubs began to lose their popularity.

Television was offering more and more channels, cinemas expanded their repertoire, and increasing numbers of

“Western” films were penetrating (both legally and illegally) into the Soviet market. After Baranov’s last school

cineclub was closed in 1984, he focused on teaching film/media education in Kalinin (later, Tver) State

University.

Inside Baranov’s Cineclub

Baranov’s cineclub started with a school cinema theater. Such theaters were common at the time. They

usually consisted of a large auditorium equipped with a 16-millimeter projector and a screen. However, Baranov

added to the familiar an unusual twist; he delegated many responsibilities of maintaining the theater to his

students. With Baranov’s help, young people decided how to divide assignments. The students became

technicians, decorators, and ticket sellers. The theater even had its own director (one of the students) and

janitors (Baranov, 2008b). Young people created posters for upcoming screenings, chose the price of the ticket

(no low grades during a given week), and supervised screening sessions. Those who wanted to join in had to

start by doing simple tasks (e.g., cleaning); later, they could move up the career ladder, and choose

A. Fedorov & E. Friesem / Journal of Media Literacy Education 7(2), 12 - 22

17