Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:36

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Teaching Creativity to Business Students: How Well

Are We Doing?

Regina Pefanis Schlee & Katrin R. Harich

To cite this article: Regina Pefanis Schlee & Katrin R. Harich (2014) Teaching Creativity to Business Students: How Well Are We Doing?, Journal of Education for Business, 89:3, 133-141, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2013.781987

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2013.781987

Published online: 06 Mar 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 832

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2013.781987

Teaching Creativity to Business Students:

How Well Are We Doing?

Regina Pefanis Schlee

Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, Washington, USA

Katrin R. Harich

California State University, Fullerton, Fullerton, California, USA

As calls for enhancing the ability of business students to think creatively and develop innovative goods and services have become universal, researchers in the area of creativity have expressed concerns that the U.S. educational system may not foster creative thinking. The authors’ research is based on a sample of 442 undergraduate business students enrolled in marketing classes at two different universities. Students’ creativity was assessed using a creativity scale that measured ways of thinking in six different areas. The authors compared creativity scores of different business majors in each of these six dimensions and found that contrary to earlier research findings, students in the quantitative business disciplines of accounting, finance, economics, and information systems outperformed other business majors in some categories of creative thinking. Specific recommendations are presented to include training in a greater variety of dimensions of creative thinking in the business curriculum.

Keywords: business students, creativity, creativity training, personality

Creativity has been equated with innovative thinking. A report by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) on Business Schools on an Innova-tion Mission calls for business schools to sharpen the cre-ative problem solving skills of students to enable innova-tion (AACSB, 2010). The Harvard Business Review has published several articles on the importance of creativity (Florida, 2004; Pink, 2004). In addition to articles in the pop-ular business press, concerns about fostering creative think-ing in business schools have echoed in a large number of articles in the business education literature (Driver, 2001; Fekula, 2011; Kerr & Lloyd, 2008; Schmidt-Wilk, 2011; Ungaretti et al. 2009; Weik, 2003).

In this study, we measure the creative thinking of business students along six dimensions, examine the students’ own perceptions of how creative they are, and discuss strategies for enhancing students’ creativity. Although this research was conducted in marketing courses, over one third of the

Correspondence should be addressed to Regina Pefanis Schlee, Seattle Pacific University, School of Business and Economics, 3307 Third Avenue W., Suite 201, Seattle, WA 98119-1950, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

students in our sample are majoring in business disciplines other than marketing.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON CREATIVITY

Definition and Measurement

There is little agreement on the definition of creativity and its components. Researchers understand that there are two levels of creativity, namely the creativity of people who solve ordi-nary problems versus breakthrough creativity that revolution-izes a discipline. There is disagreement among researchers as to whether creativity is a trait that affects a variety of areas, or whether its effects are specific to one area such as art, music, and mathematics (Baer, 1994; Plucker, 1998).

Researchers differentiate between four components of creativity, the 4 Ps: person, product, process, and press (Davis, 2004). The person component is usually assessed through self-report measures identifying characteristics as-sociated with creativity (Kelly, 2004), or by measures of participation in previous creative activities (Bull & Davis, 1980). Measures of creativity focusing on product examine

134 R. P. SCHLEE AND K. R. HARICH

the creative outcomes or products that have been generated by a person in the past, or when that person follows the instructions of a tester (Amabile, 1996). The process compo-nent of creativity is usually measured by divergent thinking tests. The press component often focuses on the effects of the environment on creativity such as the encouragement of creative activities by an organization and the provision of freedom and resources to engage in creative problem solving (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996).

The most common test measuring the creative process was developed by Torrance in 1966 and “renormed” in 1974, 1984, 1990, and 1998 (Kim, 2006). Torrance (1966) mea-sured creativity in terms of fluency (generating multiple ideas), originality (the perceived novelty of the ideas), elab-oration (the ability to articulate the ideas), abstractness of titles (the ability to look beyond the concrete manifestation of a new idea), and resistance to premature closing (keep-ing an open mind). Scor(keep-ing the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT) is very time consuming and requires that scorers have received proper training. While the TTCT is widely used, there are concerns about the ability of the test to measure actual creativity (Sternberg & Lubart, 1996). In addition, a 40-year follow up of students who had taken the TTCT explained only about 23% in the variance in the creative production of the individuals involved in the study (Cramond, Matthews-Morgan, Bandalos, & Zuo, 2005).

Amabile (1982) argued that creativity should be mea-sured more simply. She developed a consensus-based eval-uation of creativity that she called the Consensual Assess-ment Technique. Additionally, instead of focusing on the different dimensions of the creative thinking process, Ama-bile and Pillemer (2012) argued that creativity is not a trait that a person is born with, but rather a skill that can be taught and practiced. Fostering the creativity of employ-ees is essential to the success of businesses in the 21st century.

Creativity in Business Education

Within the business education literature, researchers have posited that creativity training should be part of the critical thinking skills of business students (Driver, 2001; Fekula, 2011; Kerr & Lloyd, 2008; Schmidt-Wilk, 2011; Smith, 2003; Ungaretti et al. 2009; Weik, 2003). However, some studies have found that business students have lower creativ-ity ratings than other college students. For example, McIn-tyre, Hite, and Rickard (2003) found that business adminis-tration undergraduate and graduate students scored relatively lower in creativity than other groups of students, with gradu-ate students scoring significantly lower than undergradugradu-ates. Wang, Peck, and Chern (2010) found that business admin-istration students had significantly lower scores than design students in the areas of fluency (ability to generate a number of creative ideas), flexibility (the ability to shift from one idea to another or to change perspective), originality (the ability

to produce ideas that are not commonplace), and elaboration (the ability to develop specific details for creative ideas).

Business students vary in terms of how they perceive their own creativity. Accounting graduate students appear to have both a low regard for the importance of creativity and lower personal creativity scores than the general popu-lation of master of business administration (MBA) students (Bryant, Stone, & Wier, 2011). Schlee, Curren, Harich, and Kiesler (2007) found that marketing students were the most likely to consider that the wordcreativedescribed them per-fectly (55%), as compared to management students (41%), finance students (32%), accounting students (31%), and eco-nomics students (25%). Similar findings were reported by Roach, McGaughey, and Downey (2011). Marketing is fre-quently seen as the most creative of the business disciplines because by its very nature it is focused on developing and offering “creative solutions to consumer problems” (Titus, 2000, p. 226).

Throughout the first decade of the new millennium there have been several articles in the marketing education literature focusing on techniques that improve the creative abilities of marketing students. McIntyre et al. (2003) demon-strated improvement in student creativity scores after in-troducing creativity training to MBA students. Anderson (2006) introduced a series of creative exercises to MBA students to build their creativity skills. Pearce (2006) de-scribed assignments in the marketing curriculum using ed-ucational drama to develop students’ creativity. A similar technique, the Improv Mind-Set, was used by Aylesworth (2008) to increase creative problem solving skills in case discussions.

Titus (2007) developed the Creative Marketing Break-through (CMB) model that consists of the following elements: task motivation (necessary for perseverance), serendipity (the chance finding of relationships), cognitive flexibility (the willingness to break away from conven-tional solutions and fixed patterns of thought), and disci-plinary knowledge (proficiency in a discipline). Accord-ing to Titus, CMB requires that students are taught the psychological aspects of creativity by stressing the im-portance of cognitive flexibility (uncommon sense), mak-ing them comfortable with uncertain situations or un-defined problems, and teaching them the importance of perseverance.

Possibly as a result of greater emphasis on the impor-tance of creativity in marketing, McCorkle, Payan, Reardon, and Kling (2007) found that marketing students value cre-ativity and believe it is an important skill, although it is not perceived to be more important than writing skills, oral pre-sentation skills, teamwork, leadership, marketing knowledge, and knowledge of business. Marketing students believed that their professors encouraged but did not reward creativity. In addition, McCorkle et al. found that although marketing students believed they were creative, they were no more cre-ative than other students in the following areas: flexibility,

originality, fluency, and elaboration, as well as in their total creativity scores.

Creativity Training Techniques

Although there is disagreement on the best way to mea-sure creativity and in spite of the fact that the validity and reliability of most measures of creativity have been criti-cized, training in creativity appears to impact the creative process with those receiving instruction outperforming con-trol groups by approximately one standard deviation (Pyryt, 1999). Several meta-analyses of creativity studies have also found moderate improvement in the creativity of subjects after training (Ma, 2006; Scott, Leritz, & Mumford, 2004). Business students generally receive some training in the idea generation–developing multiple ideas component of creative thinking, as brainstorming is viewed as a common way to ar-rive at new product ideas (Armstrong & Kotler, 2012; Kerin, Hartley, & Rudelius, 2012). Brainstorming as a technique for increasing creative output was pioneered by Alex Osborn (1957) in the advertising industry. Training in brainstorming techniques appears to increase ideational fluency (Clapham, 1997).

Training in metaphorical and analogical thinking tech-niques that focus on the transfer of solutions from one con-text into another is generally less common in the business curriculum. Businesses, on the other hand, often participate in workshops that enhance the metaphorical or analogical thinking of their employees. Synectics is a program that tries to generate creative solutions by taking a new perspective. For example, the understanding of how some fish are able to escape predators by having the same colors and patterns of fish that are poisonous can help design a system for pre-venting bicycle theft (Gordon, 1980). One possible answer is making the bicycle seem like something a thief would not want to steal (i.e., a bicycle owned by the police). As Synec-tics is more difficult to implement than brainstorming, we believe that most business students will not be familiar with metaphorical or analogical thinking techniques.

There are several other dimensions of creativity that have not been the subject of training programs, but have neverthe-less been found to increase creative outcomes. For example, incubation is a “period of preconscious, fringe conscious, off-conscious or perhaps unoff-conscious mental activity” (Davis, 2004, p. 122) that is often necessary before someone comes up with a creative answer to a problem. Creative people know that inspiration often does not strike when sitting at a desk, but rather when engaged in unrelated activities such as driving, eating, or taking a bath. There is some indica-tion that the creative process can even occur while dreaming because the mind is free from the distractions of everyday life (DeAngelis, 2003). Flow, the focused state of conscious-ness whereby one loses track of time while involved in an activity, is similarly a very important aspect of the creative problem-solving process (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Flow is

something that creative people do, but there are no specific creativity training programs to specifically teach this mental practice.

OUR STUDY

Methodology

The Cognitive Processes Associated with Creativity (CPAC) scale was developed by Miller (2009) and is available for use by other researchers. The CPAC scale measures both the person and process components of creativity. The primary advantages of the CPAC scale are its simplicity and its abil-ity to measure several important components of the creative problem-solving process. The CPAC scale does not rely on raters to determine the magnitude of the creative process, but instead focuses on the person’s own self-report of ways of thinking. Although social desirability has been found to con-found measures of creativity based on self-reports using other creativity scales (Whitley, 2002), the CPAC scale was found to be unrelated to social desirability and is not correlated with academic achievement and demographic characteristics.

The CPAC scale contains several of the components of creativity (analogical reasoning, brainstorming, flow, im-agery, incubation, and perspective-taking) and was validated by having students also take traditional measures of cre-ative thinking such the Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults (Goff & Torrance, 2002), the Scale of Creative Attributes and Behaviors (Kelly, 2004), the Creativity Styles Questionnaire-Revised (Kumar & Holman, 1997), and several other measures of creative reasoning. Thus, the CPAC scale mea-surements of creativity are comparable to those of other cre-ativity scales such as the TTCT.

The CPAC creativity scale (Miller, 2009) consists of six subscales measuring six different dimensions of creativity that are characterized by ways of thinking. The perspective-taking–idea manipulation component consists of five state-ments that focus on an individual’s ability to look at problems from different angles, such as “If I get stuck on a problem, I try to take a different perspective of the situation” and “Looking at a problem from a different angle can lead to a solution.” Flow is a condition that has been identified with the creative process. Flow is measured by statements such as “I can completely lose track of time if I am intensely working.” The sensory dimension focuses on the attention the creative people place on imagery, imagination, and paying attention to their senses (what it feels like). The sensory dimension was measured by statements such as “While working on a problem, I try to imagine all aspects of the solution”; “I try to act out potential solutions to explore their effectiveness”; and “While working on something, I often pay attention to my senses.” Metaphorical–analogical thinking, applying a solu-tion from another situasolu-tion to a new problem, is measured by statements such as “If I get stuck on a problem, I try to apply

136 R. P. SCHLEE AND K. R. HARICH

previous solutions to the new situation,” and “Incorporating previous solutions in new ways leads to good ideas.” Idea generation–developing multiple ideas is the creative process that is usually stimulated through brainstorming. The idea generation–developing multiple ideas was measured by state-ments such as “While working on something, I try to generate as many ideas as possible” and “Combining multiple ideas can lead to effective solutions.” Incubation, the willingness to put the problem aside to let one’s subconscious work on finding a solution is measured by statements such as “When I get stuck on a problem, a solution just comes to me when I set it aside” and “I get good ideas while doing something routine, like driving or taking a shower.” The six dimensions of creativity measured by the CPAC scale examine the mental processes used to arrive at creative outputs. It is noteworthy that most training programs in creativity focus on the men-tal processes measured by the CPAC scale as these ways of thinking precede the development of creative solutions to problems.

Hypotheses

In this research, we address several issues that pertain to the training of business students in creativity. Earlier research by McIntyre et al. (2003) and McCorkle et al. (2007) demon-strated that marketing students believe that they are more creative, but their creativity scores in terms of flexibility, originality, fluency, and elaboration as well as their total cre-ativity scores using the TTCT scale were not significantly different than those of other business students. Our first hy-pothesis examines whether business majors differ in the ways of creative thinking as measured by the CPAC scale. Our sec-ond hypothesis follows the research of Schlee et al. (2007) by examining whether marketing students believe that they are more creative than other business students using self-reports of creativity. Our third hypothesis examines the re-lationship between creativity and academic achievement. As some of the components of creativity appear to be related to creative problem solving such as perspective taking and analogical thinking, it is logical to assume that creativity is related to academic performance. However, prior research measuring the relationship between creativity and academic performance is inconclusive. Some research studies show an overall positive relationship between creativity and academic achievement (Kuncel, Hezlett, & Ones, 2004) while other studies have shown no clear relationship between creativity and academic achievement (Miller, 2009; Poropat, 2009). In this study, academic performance is measured using student self-reports of getting mostly As, Bs, or Cs. If a significant relationship is found to exist between student grades and cer-tain components of creativity, business professors may pro-vide incentives to engage high or low performing students through the use of creativity enhancing activities.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): There would be no differences in the components of creativity scores (as measured by the CPAC scale) of different groups of business majors.

H2: Marketing majors would believe that they are more cre-ative than other business majors.

H3: Academic performance would be positively related to creativity.

Sample

Our sample consists of 442 undergraduate business students at two AACSB-accredited business schools on the west coast of the United States (a large public university and a private university). During the 2011 and 2012 academic years, these students enrolled in marketing classes taught by three differ-ent professors were asked (for extra credit) to take an online version of the CPAC scale (Miller, 2009) and to rate their own creativity skills. The response rate to the online survey was over 80%.

Most of the 442 business students in our sample attended the large public university (84%). About 65% were marketing majors, 18% were mostly accounting, finance, information systems, or economics majors (the quantitative business ma-jors were combined), and 17% were mostly management and international business majors (these non-quantitative business majors were combined). There were slightly more women (52%) than men (48%) in our sample. Most students were either juniors (35%) or seniors (60%). The majority of students reported that they get mostly Bs in their classes (63%), with the remainder of the sample reporting that they get mostly As (20%) or mostly Cs (16%).

FINDINGS

Differences in the Creativity Dimensions by Business Major

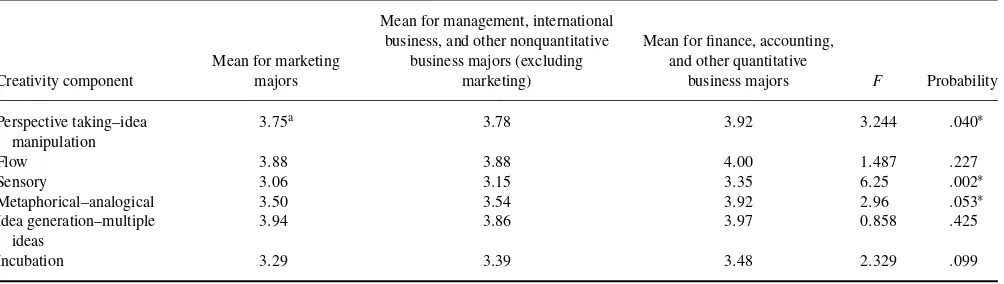

Based on the findings by McIntyre et al. (2003) and Mc-Corkle et al. (2007), we hypothesized that marketing ma-jors would have similar scores in the different dimensions of creativity as measured by the CPAC scale as other busi-ness majors. Table 1 shows the mean scores for each of the six dimensions measured by the CPAC scale. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to evaluate whether differ-ences between the three types of business majors (marketing, management and international business, and the quantitative disciplines of accounting, finance, economics, and informa-tion systems) were statistically significant. The scale in each of the dimensions ranges from 1 as the lowest score to 5 as the highest score.H1was supported for three of the six dimensions measured by the CPAC scale: flow, idea genera-tion (brainstorming), and incubagenera-tion. Idea generagenera-tion scores appear to be higher than flow and incubation scores, but the

TABLE 1

Comparison of Creativity Dimension Scores of Different Business Majors

Creativity component

differences in scores observed between the three categories of majors were not statistically significant. There were sig-nificant differences among the three types of business majors in the categories of perspective taking, sensory creativity, and metaphorical–analogical thinking. However, the differences between how the different majors scored were in an unex-pected direction. Students in the quantitative business majors appeared to score higher than the other business students in each of these three categories of creative thinking processes. Marketing majors not only did not score higher than stu-dents in the quantitative business majors as was documented by McIntyre et al. (2003) and McCorkle et al. (2007), but they actually scored lower in the scales measuring perspec-tive taking, sensory creativity, and metaphorical/analogical thinking.

H2stated that marketing majors would believe that they are more creative than other business majors based on their self-assessment. This hypothesis was based on findings by McCorkle et al. (2007), Schlee et al. (2007), and Roach et al. (2011). For this study, students were asked to rate their own creativity based on 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (low) to 10 (high). The mean rating for marketing majors was 7.64, for management and international business majors was 6.74, and for accounting, finance, economics, and in-formation systems students was 7.57. Analysis of variance revealed that the differences for the three categories of busi-ness majors were not statistically different at the .05 level of significance. Thus, hypothesis 2 was not supported. Most business students, regardless of their major, view themselves as being equally creative with a mean creativity rating of 7.51.

Creativity and Academic Grades

H3 stated that creativity and academic performance would be positively related as students who are able to engage in creative thinking may perform better in their coursework.

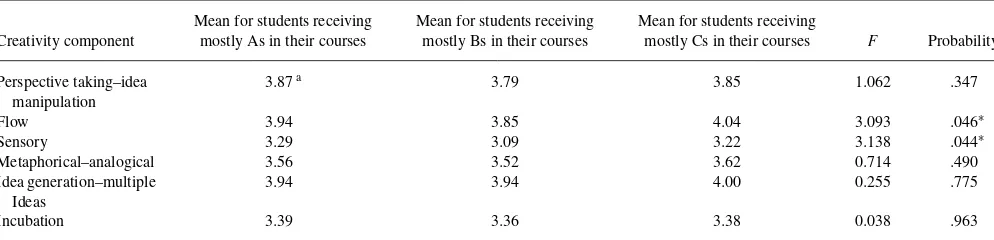

Table 2 presents a comparison of the mean scores for the six dimensions of creativity measured by the CPAC scale among the business students who reported that they received mostly As, Bs, or Cs in their courses. The results of our analysis indicate significant differences in the creativity scores of A, B, and C grade students in the areas of flow and sensory abilities. Interestingly, in both of these areas of creativity, the students receiving As were similar to students receiving Cs in terms of their flow and sensory scores. Students re-ceiving Bs received lower scores in these two dimensions of creativity than both the high and low achieving students. A possible explanation of the differences in the creativity di-mension of flow may lie in students’ abilities to engage or to become involved in a topic. Some students who received a high flow score may focus intensely on coursework that inter-ests them and thus get high grades, while the same intensity of focus may also distract other students from their academic work and result in C grades. Sensory creativity may have the same effect on academic performance by either engaging the imagination when working on a business problem or by be-ing distracted by the imagination from course requirements. Thus, engaging all students in creative problem solving may represent both a challenge and an opportunity for business educators in order to harness the creativity of low-performing students.

DISCUSSION

In reviewing our research findings, we were surprised to find that in contrast to expectations business majors in the quantitative fields of accounting, finance, economics, and in-formation systems engage in more creative ways of thinking than previously thought. While McIntyre et al. (2003) and McCorkle et al. (2007 found that marketing students score no higher in actual measurements of creativity than other business students, we found that marketing students (as well

138 R. P. SCHLEE AND K. R. HARICH

TABLE 2

Comparison of Creativity Scores by Self-Reported Student Grades

Creativity component

Mean for students receiving mostly As in their courses

Mean for students receiving mostly Bs in their courses

Mean for students receiving

mostly Cs in their courses F Probability

Perspective taking–idea

as management and international business students) scored lower than business majors in the quantitative fields of ac-counting, finance, economics, and information systems in some categories of creativity. Students in the quantitative business fields appear to be more likely to examine problems from different perspectives in order to find solutions, are more likely to consider their feelings and engage their imagination when coming up with solutions (sensory creativity), and are more likely to apply solutions from a different problem to a new situation (metaphorical/analogical thinking).

We were similarly surprised when marketing students did not rate themselves as being more creative (self-assessment) than students in the other business disciplines. Earlier re-search by McCorkle et al. (2007), Schlee et al. (2007), and Roach et al. (2011) had shown that marketing students are more likely to think of themselves as being creative than other business students. It is likely that calls for more cre-ative thinking in some of the quantitcre-ative disciplines such as accounting (Wynder, 2004) might have resulted in greater emphasis in creative problem solving in those classes.

In contrast to popular beliefs that marketing is a creative discipline (Titus, 2000), many marketing classes may not adequately encourage and reward creativity. Marketing stu-dents appear to understand the importance of generating a lot of ideas in the creative process, but so do most other business students. However, a large quantity of ideas is not synonymous with truly original ideas. Thus, the creative ef-fort may be undermined by a focus on one of the easiest ways to teach creative skills, namely the generation of numerous ideas through brainstorming. Marketing students appear to be less familiar with some of the other components of creativ-ity such as incubation, metaphorical/analogical reasoning, and the sensory component of creativity than students in the quantitative business disciplines. We believe that marketing educators in particular should integrate more creativity com-ponents in their courses. Several exercises for developing students’ creativity skills are available by Anderson (2006), Pearce (2006), Titus (2007), and Aylesworth (2008).

The differences in creativity scores by students’ grades should also be considered by business educators. Our find-ings indicate higher creativity scores in the areas of flow and sensory dimensions for students receiving A and C grades. While students receiving A grades may find appropriate av-enues for exercising their creativity in their business classes, it is possible that some students who receive Cs may not en-gage their creativity in ways that enhance their educational experience. Encouragement to engage in creative activities may provide an incentive for underperforming students to focus on business course requirements.

As creativity has been identified as an important compo-nent for business education, creativity exercises should be included in all business courses. Research has demonstrated that creativity exercises enhance students’ creative abilities (Hoever, van Knippenberg, van Ginkel, & Barkema, 2012; Nui & Liu, 2009; Reese, Parnes, Treffinger, & Kaltsounis, 1976; Ridley & Birney, 1967). In addition to the scholarly ar-ticles cited earlier that include creativity exercises, exercises for all business students can be found outside the business education literature. The nonprofit Center for Development and Learning recommends that educators model creativity in the classroom, teach students to questions assumptions, en-courage idea generation, bring different groups of students together for a cross-fertilization of creative ideas, tolerate ambiguity and mistakes, and reward creativity (Sternberg & Williams, 2013).

It is also important to acquaint students with the different dimensions of creativity. We have produced a creativity exer-cise using a creativity technique developed by psychologist Guilford (1967) that can be used in marketing in its current form and modified for use in management courses (Figure 1). Using Guilford’s technique of assessing creative thinking by developing ideas for alternative uses of common products, this exercise asks students to think of alternative uses for old tires. The exercise begins with a brief paragraph that describes the ecological problem presented by the old tires. Students are asked to think of alternative uses for discarded

Stage 1: Brainstorming. All group members should come up with several ideas for new uses for

discarded tires. Feel free to build on the suggestions made by other group mates.

Stage 2. Perspective taking. Take the perspective of a driver. Can you think of any uses for old

tires that will help drivers?

Stage 3. Metaphorical/analogical thinking. Think about uses for discarded paper. What types of

products are made with recycled paper? Then think about discarded tires. Can you apply any of

the uses of recycled paper for recycling of old tires?

Stage 4. Sensory creativity. Does driving with new tires for your car feel different than when you

had old tires? How does it feel to handle products made with recycled rubber (ex. door mats)?

Can you think of any uses of old tires based on your experiences?

Stage 5. Incubation. This stage will be completed at our next class meeting. Did you think of any

new uses for old tires after our last class period? Share your ideas with your group first and then

with the class.

The Problem: According to the Federal Highway Administration (2012), about 280 million tires

are discarded by U.S. motorists each year. There are several uses for old tires such as using them

for fuel (about 40% of used tires), using them as retreads, or grinding them so that they can be

reused in other products such as door mats, or as an additive to asphalt for paving roads. The

Federal Highway Administration estimates that 45% of old tires are dumped into landfills.

Your Job: To develop alternative uses for discarded tires. Please get into groups of 4 to 6

students. Appoint one group member as the recorder of your suggestions. You will have 5

minutes to come up with creative ideas at each stage. The recorder will share your group’s

creative ideas with the class after we complete each stage of this exercise.

FIGURE 1 Alternative uses of old tires creativity exercise.

tires using a series of questions focusing on the different di-mensions of creativity (idea generation, perspective taking, sensory, analogical, metaphorical, and incubation). Figure 1 describes the sequence of steps in creative thinking. The first step asks students to brainstorm new uses for old tires. Al-though brainstorming is one of the most common techniques for generating new product ideas, the product ideas gener-ated by students at this stage were generally not novel (e.g., create large plant containers, use the tires in playgrounds, use tires for physical education classes in high schools and colleges). The second step, perspective taking, resulted in more elaborated creative ideas. When students were asked to take the perspective of a driver for possible uses of old

tires, one student mentioned the use of old tires as barri-ers as in Go-Kart racing tracks. Another student was able to build on the Go-Kart barrier idea by noting that old tires can be formed into rectangular barriers to be used instead of cement barriers to separate lanes of oncoming traffic in highways. Rubber highway barriers were perceived by stu-dents to be superior to cement barriers because they would cause less damage to vehicles coming in contact with the barrier. Step 3, sensory creativity, did not result in many new ideas for using old tires. Students liked the feel of driving with new tires because they perceived the ride was smoother. This stage reinforced student interest in adding ground rub-ber tires to asphalt pavement to achieve a smoother ride.

140 R. P. SCHLEE AND K. R. HARICH

For Step 4, analogical creativity, students considered current uses for recycled paper for product packages and egg car-tons and suggested creating durable packing materials out of tire rubber. Step 5, incubation, required students to con-sider alternative ideas for using old tires during the following class period. This stage produced important elaborations of the ideas that had been generated during the previous class period such as creating better packaging materials out of rub-ber or improving the concept of rubrub-ber barriers for highways by combining a cement core with an external coat of rub-ber. In management courses, this exercise can be modified by focusing students’ efforts on developing alternative so-lutions to management issues such as increasing employee engagement and productivity.

The exercise shown in Figure 1 not only teaches students how to use the different dimensions of creativity when look-ing for solutions to problems, but also demonstrates the im-portance of continuing to work on creative ideas over time. Great ideas do not always occur when one is working at one’s desk or in the classroom. Allowing the mind to rest, putting the problem aside for a few hours or even days, is an important component of the incubation process of creativ-ity. Original ideas often occur at times when one is involved in unrelated activities such as driving or taking a shower. Creativity also requires long-term commitment to innovative thinking processes. Titus (2007) included task motivation and perseverance in his Creative Marketing Breakthrough model. Titus gave the examples of Thomas Edison who conducted 1,000 experiments before perfecting the incandescent light bulb and Arthur Jones who worked for 20 years in the devel-opment of the Nautilus exercise machine. Creativity does not just happen in an hour-long brainstorming session in a focus group setting; creativity requires preparation, perseverance, and patience. Presenting information on the lives of creative people such as Edison and Jones can demonstrate both con-nections and ways of thinking, but also ways of working that result in creative ideas (Strauss, 2002).

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The sample of students who participated in this study may not reflect the attitudes and thought patterns of business stu-dents in other areas of the United States. Thus, our findings are specific to the time and place where this research took place. The differences we observed between our findings and the findings of McCorkle et al. (2007) might have been the result of the specific group of students used in each study and may not reflect an increased appreciation of creativity among business students in the quantitative disciplines. Future re-search on different samples of business students using the publically available CPAC scale as well as different scales of creativity should provide greater insights on the state of creativity training in the business curriculum.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual as-sessment technique.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,45, 997–1013.

Amabile, T. M. (1996).Creativity in context.Boulder, CO: Westview. Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996).

Assessing the work environment for creativity.Academy of Management Journal,39, 1154–1184.

Amabile, T. M., & Pillemer, J. (2012). Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity.The Journal of Creative Behavior,46, 3–15.

Anderson, L. (2006). Building confidence in creativity: MBA students. Mar-keting Education Review,16, 91–96.

Armstrong, G., & Kotler, P. (2012).Marketing: An introduction(11th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2010). Business schools on an innovation mission.Retrieved from http://www. aacsb.edu/resources/innovation/business-schools-on-an-innovation-mis-sion.pdf

Aylesworth, A. (2008). Improving case discussion with an improve mind-set. Journal of Marketing Education,30, 106–115.

Baer, J. (1994). Divergent thinking is not a general trait: A multi-domain training experiment.Creativity Research Journal,7, 35–36.

Bryant, S. M., Stone, D., & Wier, B. (2011). An exploration of accountants, accounting work, and creativity.Behavioral Research in Accounting,23, 45–64.

Bull, K. S., & Davis, G. A. (1980). Evaluating creative potential using the statement of past creative activities.The Journal of Creative Behavior, 14, 249–257.

Clapham, M. M. (1997). Ideational skills training: A key element in creativ-ity training programs.Creativity Research Journal,10, 33–44. Cramond, B., Matthews-Morgan, J., Bandalos, D., & Zuo, L. (2005). A

report on the 40-year follow-up of the Torrance Tests of creative thinking. Gifted Child Quarterly,49, 283–356.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996).Creativity: Flow and the psychology of dis-covery and invention. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers. Davis, G. (2004).Creativity is forever(5th ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. DeAngelis, T. (2003). The dream canvas.Monitor on Psychology,34(10),

44–46.

Driver, M. (2001). Fostering creativity in business education: Developing creative classroom environments to provide students with critical work-place competencies.Journal of Education for Business,7728–33. Federal Highway Administration. (2012). User guidelines for waste

and byproduct materials in pavement construction.Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved from http://www.fhwa. dot.gov/publications/research/infrastructure/structures/97148/st1.cfm Fekula, M. (2011). Managerial creativity, critical thinking, and emotional

in-telligence: Convergence in course design.Business Education Innovation Journal,3, 92–102.

Florida, R. (2004). America’s looming creativity crisis.Harvard Business Review,82, 122–130.

Goff, K., & Torrance, E. P. (2002).Abbreviated Torrance test for adults manual.Bensenville, IL: Scholastic Testing Service.

Gordon, W. J. J. (1980).The new art of the possible: The basic course in synectics.Cambridge, MA: Porpoise Books.

Guilford, J. P. (1967).The nature of human intelligence. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hoever, I. J., van Knippenberg, D., van Ginkel, W. P., & Barkema, H. G. (2012). Fostering team creativity: Perspective taking as key to un-locking diversity’s potential.Journal of Applied Psychology,97, 982– 966.

Kelly, K. E. (2004). A brief measure of creativity among college students. College Student Journal,38, 594–596.

Kerin, R., Hartley, S., & Rudelius, W. (2012).Marketing(11th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Kerr, C. & Lloyd, C. (2008) Pedagogical learnings for management educa-tion: Developing creativity and innovation.Journal of Management and Organization,14, 486–503.

Kim, K. H. (2006). Can we trust creativity tests? A review of the Torrance tests of creative thinking (TTCT).Creativity Research Journal,18, 3–14. Kumar, V. K., & Holman, E. R. (1997). The Creativity Styles Questionnaire–Revised. Unpublished psychological test. Department of Psychology, West Chester University of Pennsylvania, West Chester, PA. Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct pre-dict them all?Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,86, 148. Ma, H. H. (2006). A synthetic analysis of the effectiveness of single

compo-nents and packages in creativity training programs.Creativity Research Journal,18, 435–446.

McCorkle, D. E., Payan, J. M., Reardon, J., & Kling, N. D. (2007). Per-ceptions and reality: Creativity in the marketing classroom.Journal of Marketing Education,29, 254–261.

McIntyre, F. S., Hite, R. E., & Rickard, M. K. (2003). Individual charac-teristics and creativity in the marketing classroom: Exploratory insights. Journal of Marketing Education,25, 143–149.

Miller, A. L. (2009).Cognitive processes associated with creativity: Scale development and validation.Muncie, IN: Ball State University. Retrieved from http://cardinalscholar.bsu.edu/763/1/Amiller 2009–2 BODY.pdf Nui, W. & Liu, D. (2009). Enhancing creativity: A comparison between

the effects of an indicative instruction “to be creative” and more elab-orate heuristic instruction on Chinese student creativity.Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts,3, 93–98.

Osborn, A. F. (1957).Applied imagination: Principles and procedures of creative problem solving. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Pearce, G. (2006). University student perceptions of the difference between

educational drama and other types of educational experiences.Journal of Marketing Education,16, 23–35.

Pink, D. H. (2004). The MFA is the New MBA.Harvard Business Review, 82, 21–22.

Plucker, J. A. (1998). Beware of simple conclusions: The case for content generality of creativity.Creativity Research Journal,11, 179–182. Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality

and academic performance.Psychological Bulletin,135, 322–338. Pyryt, M. C. (1999). Effectiveness of training children’s divergent thinking:

A meta-analytic review. In A. S. Fishkin, B. Cramond, & P. Olszewski-Kubilius (Eds.),CPAC scale validation, investigating creativity in youth: Research and methods(pp. 351–365). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton. Reese, H. W., Parnes, S. J., Treffinger, D. J., & Kaltsounis, G. (1976). Effects

of creative studies program on structure-of intellect factors.Journal of Educational Psychology,68, 401–410.

Ridley, D. R. & Birney, R. C. (1967). Effects of training procedures on creativity test scores.Journal of Educational Psychology,58, 158–164. Roach, D. W., McGaughey, R. E., & Downey, J. P. (2011). Selecting a

busi-ness major within the college of busibusi-ness.Administrative Issues Journal, 2, 107–121.

Schlee, R. P., Curren, M. T., Harich, K. R., & Kiesler, T. (2007). Percep-tion bias among undergraduate business students by major.Journal of Education for Business,82, 169–177.

Schmidt-Wilk, J. (2011). Fostering management students’ creativity. Jour-nal of Management Education,35, 775–778.

Scott, G., Leritz, L. E., & Mumford, M. D. (2004). The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review.Creativity Research Journal, 16, 361–388.

Smith, G. F. (2003). Beyond critical thinking and decision making: Teaching business students how to think.Journal of Management Education,27, 24–51.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1996). Investing in creativity.American Psychologist,51, 677–688.

Sternberg, R. J., & Williams, W. M. (2013). Teaching for creativity: Two dozen tips. Center for Development and Learning. Retrieved from http://www.cdl.org/articles/teaching-for-creativity-two-dozen-tips/ Strauss, S. D. (2002).The big idea: How business innovators get great ideas

to market.Chicago, IL: Dearborn Trade.

Titus, P. A. (2000). Marketing and the creative problem-solving process. Journal of Marketing Education,22, 225–235.

Titus, P. A. (2007). Applied creativity: The creative marketing breakthrough model.Journal of Marketing Education,29, 262–272.

Torrance, E. P. (1966).The Torrance tests of creative thinking. Norms. Technical manual research edition: Verbal tests, forms A and B. Figural tests, forms A and B.Princeton, NJ: Personnel Press.

Ungaretti, T., Chomowicz, P., Canniffe, B. J., Johnson, B., Weiss, E., Dunn, K., & Cropper, C. (2009). Business+design: Exploring a competitive edge for business thinking.SAM Advanced Management Journal,74, 4–43.

Wang, S., Peck, K. L., & Chern, J. (2010). Difference in time influencing creativity performance between design and management majors. Interna-tional Journal of Technology & Design Education,20, 77–93.

Weik, C. W. (2003). Out of context: Using metaphor to encourage cre-ative thinking in strategic management courses.Journal of Management Education,27, 323–343.

Whitley, B. E., Jr. (2002).Principles of research in behavioral science(2nd ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Wynder, M. (2004). Facilitating creativity in management accounting: A computerized business simulation.Accounting Education: An Interna-tional Journal,13, 231–250.