Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:01

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Succeeding in the Corporate Arena: The Evolution

of College Students’ Perceptions of the Necessary

Ethical Orientation

Milton M. Pressley & Pamela A. Kennett-Hensel

To cite this article: Milton M. Pressley & Pamela A. Kennett-Hensel (2013) Succeeding in the Corporate Arena: The Evolution of College Students’ Perceptions of the

Necessary Ethical Orientation, Journal of Education for Business, 88:4, 223-229, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.683462

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.683462

Published online: 20 Apr 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 134

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.683462

Succeeding in the Corporate Arena: The Evolution

of College Students’ Perceptions

of the Necessary Ethical Orientation

Milton M. Pressley and Pamela A. Kennett-Hensel

University of New Orleans, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

The authors’ purpose was to determine the perceptions of present university students regarding job politics as practiced by those climbing the corporate career ladder, and to compare them with the perceptions of students from a previous generational cohort that participated in a similar study more than 25 years earlier. Data were collected from 1,512 students enrolled at a major urban university in the Southeastern United States. Results from the present study, as compared to the 1984 study, indicate that today’s college students are more optimistic regarding what it takes to get ahead in the corporate world. Comparative results also uncover the declining influence of citizenship, race, and religion, and the increasing influence of education-related demographics. A discussion of the findings and implications for educators and the business community is provided.

Keywords: cohort analysis, college students, ethical orientation, job politics, millennials

In 1984, Pressley and Blevins assessed the extent to which university students, presumably the executives of the future, agreed with various commonly heard assertions regarding the tactics of those climbing the career ladder. Essentially their study examined the necessary ethical orientation for success in the corporate arena, and the results, not surpris-ingly, reflected the Gordon Gekko mentality of the times in which winning is everything and selling one’s soul is a pre-cursor to success. Since 1984, these respondents and their contemporaries have entered the workplace, a world that has been marred by major ethical breaches in recent years. Add to these business scandals those in the political, legal, media, academic, and other environments, it is hard not to won-der how today’s cohort of primarily Millennium Generation students would respond to the questions asked of their late Baby Boomer and early Gen X predecessors in 1984 and what differences might be uncovered.

The purpose of this study was to replicate the work of Pressley and Blevins (1984) in order to explore the percep-tions of present university students regarding job politics as practiced by those climbing the corporate career ladder. As

Correspondence should be addressed to Pamela A. Kennett-Hensel, Uni-versity of New Orleans, College of Business, Department of Marketing & Logistics, KH 343F, New Orleans, LA 70148, USA. E-mail: pkennett@ uno.edu

was done in the original study, the results are also examined to determine if differences exist among various demographic groups among the present students. Finally, we compare the results to data collected in 1984 to explore possible changes that may have occurred in the past 25+years. Implications for educators, organizations, and managers are discussed.

GENERATIONAL CHANGES

Anyone teaching in a university in the mid-1980s who is still teaching today has observed significant changes in the mindset of the student population. Most of today’s col-lege students, especially undergraduates, are members of the Millennium Generation, and are compared to their Baby Boomer and Gen X predecessors. Schewe and Noble (2000) stated that each cohort generation shares common and dis-tinct social characters shaped by their experiences over time. Kupperschmidt (2000) concluded that each generation has developed a personality that influences their feelings toward authority and organizations, what they expect from their work, and how they plan to achieve those expectations. A significant body of research substantiates that differences do exist between college students past and present (cf. Alexan-der & Sysko, 2011; Bourke & Mechler, 2010; Giacomino, Brown, & Akers, 2011) and that the traditional profiles of

224 M. M. PRESSLEY AND P. A. KENNETT-HENSEL

various cohorts are well founded (Gibson, Greenwood, & Murphy, 2009).

When contrasted with previous generations of college stu-dents, present college stustu-dents, predominantly Gen Y and commonly referred to as Millenials, view themselves as highly reliable and responsible members of society (Har-risInteactive, 2004). They have witnessed the downsizing of their parents’ generation and developed a distrust of insti-tutions (Ryan, 2000). Having seen terrorist attacks, war, an erratic economy and multiple corporate and other scandals, they are pessimistic about the direction of the country and dissatisfied with American leadership. They are not hesitant to voice their opinions. According to Jennings (2000), they crave higher salaries, flexible work arrangements, and more financial leverage. Three-fourths of this cohort say how they spend their time is more important than how much money they make (HarrisInteractive, 2004). Having a tremendous appetite for work, they are expected to be the first generation to be socially active since the 1960s (Ryan, 2000).

In the same breath, today’s college students have been characterized by others using seven sometimes unflattering descriptors: internalize the belief that they are special, live sheltered lives, are self-confident, are team oriented, are con-ventional, feel pressured, and are high achieving (Bourke & Mechler, 2010). On a less negative note, they have been found to exhibit positive attitudes toward work and low lev-els of cynicism when it comes to the workplace and the ability to be successful postcollege (Josiam et al., 2009). The overwhelming majority believe that companies have a social responsibility (Achua & Lussier, 2008). Similarly, a posi-tive change in the cohort’s value system has been identified when compared to previous generations of college students (Giacomino et al., 2011).

This is heartening given the recent findings of the Rutgers Institute for Ethical Leadership, which concluded that there is “a dearth of ethical behavior and ethical leadership” and that “trust in leaders is low, trust in CEOs is lower” (Plinio, Young, & Lavery, 2010, p. 172). Many of today’s college students will advance to leadership roles in the future. In a meta-analysis exploring ethical choice in the workplace, Kish-Gephart, Harrison, and Trevino (2010) provide strong evidence that an individual’s cohort places a critical role in moral reasoning and views of ethical behavior. This peer in-fluence on ethics is quite prevalent in today’s college environ-ment (Joseph, Berry, & Deshpande, 2010). An exploration of how today’s college students as compared to previous gener-ations view the role of ethics in workplace success will shed light on how the corporate arena may change in the future and provide an historical perspective on the present business climate.

METHODOLOGY

To accomplish the research objectives, a survey containing two distinct sections was designed. The first section

con-tains 12 questions (11 scaled and 1 open-ended) that capture respondents’ perceptions of ethical orientation. These ques-tions are identical to the quesques-tions utilized by Pressley and Blevins (1984). As in the original 1984 study, respondents were asked for descriptive, not normative, opinions. In other words, subjects were asked whether they believe that individ-uals climbing the corporate ladder have to engage in certain activities, not whether they should engage in said activi-ties. The second section contains 10 demographic questions. These questions mirror those used by Pressley and Blevins (1984), but were updated to reflect appropriate vernacular. The Appendix provides a more detailed overview of the sur-vey.

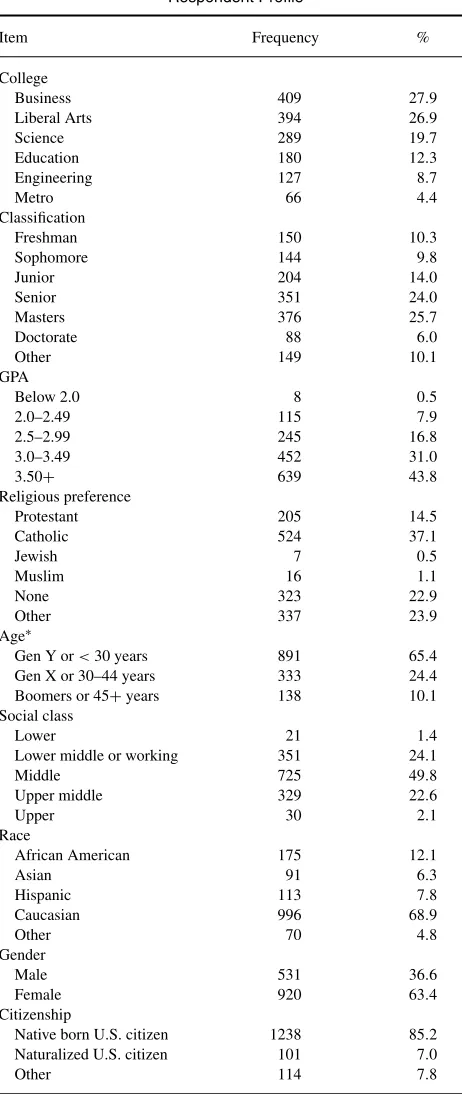

Data was collected using online survey software from students enrolled at a major public, urban university in the Southeastern United States. An initial email containing a request for participation and link to the survey was sent to all students enrolled at the institution (n=10,502). This initial request was followed by three reminder emails sent over a 10-day period. The survey was left open for approximately three weeks following the last reminder email. While response rate varies by question, 1,512 individuals started the survey (14.4%), and 1,471 completed the entire survey (14.0%). Respondents represent a cross-section of the student body (see Table 1 for a respondent profile). Further, this profile was compared to the university’s student profile data to ensure it adequately depicted the defined population. It is worth noting that this sample is similar to the sample (n=941) utilized by Pressley and Blevins in 1984, which was also drawn from the student body of a major state university in the Southeastern United States.

RESULTS

Perceptions of Present Students

Respondents were asked to consider the 11 statements found in Part I of the survey and evaluate each statement us-ing a 7-point scale, rangus-ing from 1 (always the case) to 7

(never the case). This numerical scale, a variant of a

se-mantic differential scale, is ordinal in nature. However given that the intervals are equal appearing and the data is essen-tially normally distributed, it can be analyzed as interval data (Bollen & Barb, 1981; Rash & Guiard, 2004; Spector, 1976). The mean responses and standard deviations are found in Table 2. In general, mean responses tended to gravitate to-ward the middle three points on the scale (i.e., frequently the case, occasionally the case, and infrequently the case). How-ever, some interesting differences in responses did emerge.

Respondents to the present study were least likely to be-lieve that family does not matter (Q10), personal values had to be set aside (Q9), and an individual has to indulge in dirty tactics (Q6). They were more likely to believe that success leaves one with an overdeveloped head and underdeveloped

TABLE 1

Education 180 12.3

Engineering 127 8.7

Metro 66 4.4

Protestant 205 14.5

Catholic 524 37.1

Lower middle or working 351 24.1

Middle 725 49.8

Upper middle 329 22.6

Upper 30 2.1

Race

African American 175 12.1

Asian 91 6.3

Hispanic 113 7.8

Caucasian 996 68.9

Other 70 4.8

Gender

Male 531 36.6

Female 920 63.4

Citizenship

Native born U.S. citizen 1238 85.2

Naturalized U.S. citizen 101 7.0

Other 114 7.8

Note.Majors within colleges were reported by respondents, but are not included in this profile due to the large number of different majors. Reported percentages represent valid percents; percents in some categories may not total 100% due to rounding.

∗Mean=29.13;SD=9.911.

TABLE 2

Perceptions of Ethical Orientation Mean Responses

Evaluated statement M SD

To progress, one has to develop the philosophy that winning is everything. (Q1)d,f,h

3.37 1.495 The career pressures of advancing leave one

with an overdeveloped head and an underdeveloped heart. (Q2)d

3.33 1.205

One can succeed even if one’s work is not the most important thing in one’s life. (Q3)h

3.34 1.479 Even though one might say and believe

something like “customer satisfaction” is the primary goal of the organization, one has to develop an attitude that making money is the single most important objective. (Q4)d

3.34 1.706

One just about has to “sell their soul” to the organization to get ahead. (Q5)b,c,d,e,g,h

3.74 1.648 To progress, one will occasionally have to

indulge in “dirty” tactics. (Q6)a,c,d

4.59 1.690 To advance, the corporation has to come first,

even before one’s family. (Q7)b,d,e,h

4.01 1.772 One cannot progress without “stepping on a

few people.” (Q8)a,d,e

3.82 1.734 All personal values have to be set aside in

order for one to advance. (Q9)a,d,e

4.55 1.723 To advance, one has to develop the philosophy

that what does not relate to winning and career advancement, including one’s family, does not really matter. (Q10)d,h

4.81 1.708

To climb the ladder, one must not only be prepared to aggressively move past those who stand in the way, but may find it necessary to “clear the path.” (Q11)d,e,g

3.87 1.592

Note.Responses were rated on a 7-point numerical scale ranging from 1 (always the case) to 7 (never the case).

aSignificant differences by college of study (p≤.05),bSignificant dif-ferences by year in school (p≤.05),cSignificant differences by GPA (p≤ .05),dSignificant differences by gender (p≤.05),eSignificant differences by social class (p≤.05),fSignificant differences by citizenship (p≤.05), gSignificant differences by race (p≤.05),hSignificant differences by age (p≤.05).

heart (Q2), an individual can succeed even if his or her work is not the most important thing in life (Q3), an individual must develop the attitude that making money is the single most im-portant objective (Q6), and adopt the philosophy that winning is everything (Q1). Differences based on demographic char-acteristics are examined using analyses of variance (or in the case of gender, an independent samplet-test). Where signif-icant differences emerged based on the analysis of variance (p≤.05), least significant difference tests were run to isolate the exact differences. These differences also are highlighted in Table 2.

Some differences did emerge in responses based on three important educational classification variables: college, year in school, and grade point average (GPA). For certain ques-tions, students enrolled in liberal arts and sciences hold differ-ent perceptions than those in business and engineering, with

226 M. M. PRESSLEY AND P. A. KENNETT-HENSEL

the former indicating that unethical behaviors may be more necessary than the latter. Further, for select questions fresh-men were a bit more optimistic than their more seasoned counterparts—indicating their perception that the corpora-tion does not have to come first. Last, those students with higher GPAs, for certain questions, were less optimistic than those with lower GPAs.

When examining the responses for differences by the more personal characteristics, some very interesting significant differences emerged. With the exception of Q3 (“One can succeed even if one’s work is not the most important thing in one’s life”), men and women held different views. Men consistently had lower mean responses, indicating that they felt the statements were more likely to be the case than their female counterparts and are, perhaps, more cynical when it comes to what it takes to climb the corporate ladder.

Also, age, as grouped to reflect the three generational co-horts, yielded some interesting differences for five of the 11 questions. Gen Y generally appeared to be more optimistic about what is necessary to succeed in the workplace. This generation was less likely to believe that winning is every-thing, it is necessary for an individual to sell his or her soul, the corporation has to come first, and that family does not matter. Also, Gen Y was more likely to believe that an in-dividual can succeed even if work is not the most important thing,

Social class also resulted in some interesting differences. Differences were uncovered for five of the 11 questions. In particular, individuals who considered themselves of lower–lower middle–working classes were more likely to believe that it is necessary to sell their soul and to have to set personal values aside. The middle class was less likely to agree that it is necessary to clear the path, step on people, and to put the corporation first.

Only one significant difference emerged when examin-ing the data by citizenship. Individuals who are native-born Americans were less likely to believe that winning is every-thing when compared to naturalized Americans and citizens of other nations. When it came to race, two significant dif-ferences emerged. African Americans were less likely than Caucasians and Hispanics to believe that an individual must sell his or her soul, but more likely to believe that it is neces-sary to clear the path. Perhaps, most surprising, is that no dif-ferences in opinions were uncovered by religious preference.

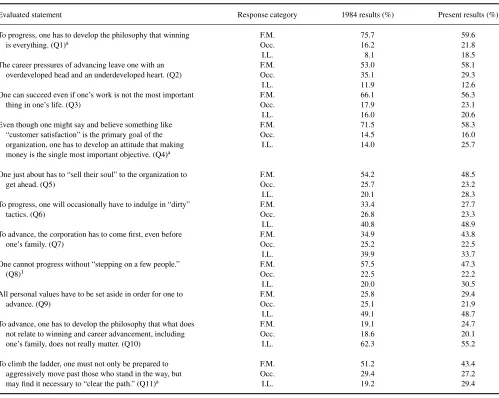

Comparison to 1984 Results

In the original 1984 study, responses to the 11 perceptions of ethical orientation questions were collapsed into three cate-gories: frequently or more often, occasionally, infrequently or less often. For comparative purposes, the results of the present study were collapsed in the same manner. Table 3 summarizes the comparison of the results of the two studies. To determine if statistically significant (p≤.05) changes have occurred over time, a chi-square analysis was conducted. We

opted for the most conservative analysis, treating the 1984 re-sponses as the expected rere-sponses and comparing the present responses to these expectations.

Statistically significant changes occurred over time for four of the 11 questions: to progress, an individual has to develop the philosophy that winning is everything (Q1); an individual has to develop an attitude that making money is the single most important objective (Q4); an individual cannot progress without stepping on a few people (Q8); an individual may find it necessary to clear the way (Q11). The present respondents tended to be more optimistic regarding their ethical perceptions. With respect to all four of these questions, the shift was toward the infrequently or less often end of the scale.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Have students’ perceptions of job politics in the workplace changed more than 25 years later? The answer is yes and, arguably, for the better. Perhaps, this is a continuation of a trend first identified by Emerson and Conroy (2004) who noted that ethical attitudes of students in 2001 were higher than in 1985. While they observed normative changes in ethi-cal behavior, this study identifies descriptive changes in what students feel is necessary to get ahead in the corporate world. These positive changes are consistent with the research re-garding today’s college students and how they differ from previous cohorts (e.g., Giacomino et al., 2011). Interestingly, these differences are further underscored by the significant differences found when examining the results of the present study by age. While the sample in its entirety exhibited some-what positive perceptions, the positivity was magnified in those who can be classified as Gen Y and millennials.

The most pronounced shift in responses of 1984 versus today’s students was with respect to two questions. First, there was considerably less agreement with the notion that to progress, one has to develop the philosophy that winning is everything. In 1984, 75.7% of the respondents felt that this was frequently or more often the case, but today, only 59.6% felt this way. A similar shift was seen in responses to the notion that making money is the single most important objective. In 1984, 71.5% of respondents felt this was fre-quently or more often the case, but today, only 58.3% felt this way. Today’s college student would appear to encom-pass a true stakeholder view of the business world in which a corporation has a responsibility to multiple groups of indi-viduals and not simply a fiduciary responsibility to investors. Woven in this philosophy is a different definition of winning, and perhaps that a true win–win situation might be possible versus a win at all costs perspective.

Two other statistically significant changes emerged in the comparative analysis. When asked their assessment of the statement that an individual cannot progress without stepping on a few people, 30.5% of the present respondents indicated

TABLE 3

Comparison to 1984 Results

Evaluated statement Response category 1984 results (%) Present results (%) To progress, one has to develop the philosophy that winning

is everything. (Q1)a

F.M. The career pressures of advancing leave one with an

overdeveloped head and an underdeveloped heart. (Q2)

F.M. One can succeed even if one’s work is not the most important

thing in one’s life. (Q3)

F.M. Even though one might say and believe something like

“customer satisfaction” is the primary goal of the organization, one has to develop an attitude that making money is the single most important objective. (Q4)a

F.M.

One just about has to “sell their soul” to the organization to get ahead. (Q5) To progress, one will occasionally have to indulge in “dirty”

tactics. (Q6) To advance, the corporation has to come first, even before

one’s family. (Q7) One cannot progress without “stepping on a few people.”

(Q8)1 All personal values have to be set aside in order for one to

advance. (Q9) To advance, one has to develop the philosophy that what does

not relate to winning and career advancement, including one’s family, does not really matter. (Q10)

F.M. To climb the ladder, one must not only be prepared to

aggressively move past those who stand in the way, but may find it necessary to “clear the path.” (Q11)a

F.M.

Note.F.M.=frequently or more often; Occ.=occasionally; I.L.=infrequently or less often. aStatistically significant (p≤.05) shift in response pattern from 1984 to today.

this to be infrequently or less often the case versus 20.0% in 1984. A similar response pattern was found with respect to the necessity to clear the path as an individual climbs the corporate ladder. In 1984, 19.2% indicated this as an infre-quent or less often occurrence, versus 29.4% today. Present college students seem to be less convinced of the notion that one’s success has to be at the expense of another’s.

In the 1984 study, highly significant differences were found based on citizenship, race, and religion. In stark contrast, very few, if any, significant differences were found with respect to these same variables in the present study. Religious preference resulted in no differences in students’ perceptions. Citizenship resulted in one difference and race in two. Historically, as outlined in Parson’s theory of so-cialization, cultural values are transferred from generation to generation through an individual’s interactions in the home,

school and church (Parsons, 1951). However, these results indicate that perhaps over the last 25 years the influence of the home and church has become less pervasive and other identities or communities are performing this function.

Very pronounced differences were found in the present study when it came to gender, age, and social class. In the 1984 study, these changes were considered only moderately significant. Consistent with other ethics research (e.g., Arlow, 1991; Borkowski & Ugras, 1992; Cole & Smith, 1996; Mir-shekary, Yaftian, & Mir, 2011; Rawwas & Isakson, 2000; Shepard & Hartenian, 1990), we found that women were more optimistic when it comes to ethical and socially sible issues, and as previously discussed, younger respon-dents were more optimistic. Social class differences suggest that lower classes are less optimistic regarding what is neces-sary to get ahead, and that middle classes are most optimistic.

228 M. M. PRESSLEY AND P. A. KENNETT-HENSEL

One plausible explanation is that college students who view themselves as middle class have watched their parents make something of themselves while those in the lower class have yet to witness that movement. Further, these social class dif-ferences are in line with Marx’s theory that each social class determines its own value system (Abercrombie & Turner, 1978).

When it comes to education-related demographics, some significant differences were found with respect to college of enrollment, year in school, and GPA. In the 1984 study, no significant findings were found with respect to GPA, and moderately significant differences emerged for the other two variables. The role of the educational system in the transfer-ence of cultural values has conceivably grown stronger over the past 25 years increasing the influence of these variables. Students spend a significant amount of time in the classroom setting in which tolerance and egalitarianism are common themes.

The workplace of the future likely is to be much different as Boomers and Gen Xers are replaced by today’s college students, many of whom are Millenials. A shift in cultural values and perspectives is evident between these cohorts. Today’s college students seem more optimistic and balanced in their views of what it takes to be successful in the corporate world compared to individuals at the same point in their life cycle a quarter of a century earlier.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

As with any research study, this study has several limitations. This multiple cross-sectional study presents the views of not only the present cohort of college students, but compares its views to the views of a similar cohort of students who were in college in 1984. However, both studies capture a group’s thoughts at a single point in time and cannot isolate all variables impacting those thoughts. It would be insightful to understand the why behind these changes. Another interesting issue that cannot be examined is how the original 1984 cohort has changed over time. A longitudinal study such as this would be useful in understanding trends and changes within a cohort. While beyond the scope of this study, future researchers are encouraged to pursue longitudinal data collection.

The generalizability of the results of this study also should be considered. Any given student body has its unique characteristics. This particular university is located in the Southeastern United States. It is typically characterized as a commuter school with a large number of students who work to put themselves through school. As a result, these individ-uals may be savvier about the business world than students from a noncommuter school. Further, there is likely some nonresponse bias in this sample. The survey was emailed to the entire student body. While the demographics of those who participated are suitably reflective of the student body

demographics, those who chose to participate may be dif-ferent than those who did not participate. Future researchers may find other sampling techniques more appropriate than the one employed in this study.

The comparative analysis outlined in this manuscript was driven by the initial analysis conducted by Pressley and Blevins in 1984. Perhaps, other approaches to assessing changes would be preferable, but were not plausible given that the original data in its raw form was not available. The summary data as presented in the originalJournal of Business

Ethicsarticle were utilized. Further, comments regarding the

quality of the original sample cannot be noted given this lack of access to the original data set.

This research has shown a positive shift in the perceptions of present college students regarding what it takes to succeed. The ascension of these students to higher levels of authority and power in the workplace may create some very interesting changes, in attitudes and behaviors. Today’s generation of college students, as noted in the literature review, take distinct characteristics to the workforce. Future researchers should study the impact of this generation on the corporate world and whether this optimism remains intact. Future researchers should also explore the intriguing issue of mechanisms for transferring cultural values. Where do present and future generations learn their values and what impact does this have on the future of the corporate arena?

REFERENCES

Abercrombie, N., & Turner, B. S. (1978). The dominant ideology thesis.

British Journal of Sociology,29, 149–170.

Achua, C., & Lussier, R. N. (2008). An exploratory study of business stu-dents’ discretionary social responsibility.Small Business Institute Jour-nal,1(1), 76–90.

Alexander, C. S., & Sysko, J. M. (2011). A study of the cognitive determi-nants of generation y’s entitlement mentality.Proceedings of the Academy of Educational Leadership,16, 1–6.

Arlow, P. (1991). Personal characteristics in college students’ evaluations of business ethics and corporate social responsibility.Journal of Business Ethics,10, 63–69.

Bollen, K. A., & Barb, K. H. (1981). Pearson’srand coarsely categorized measures.American Sociological Review,46, 232–239.

Borkowski, S. C., & Ugras, Y. J. (1992). The ethical attitudes of students as a function of age, sex and experience.Journal of Business Ethics,11, 961–979.

Bourke, B., & Mechler, H. S. (2010). A new me generation? The increasing self-interest among millennial college students.Journal of College & Character,11, 1–9.

Cole, B. C., & Smith, D. L. (1996). Perceptions of business ethics: Students vs. business people.Journal of Business Ethics,15, 889–896.

Emerson, T. L. N., & Conroy, S. J. (2004). Have ethical attitudes changed? An intertemporal comparison of the ethical perceptions of college students in 1985 and 2001. Journal of Business Ethics, 50, 167–176.

Giacomino, D. E., Brown, J., & Akers, M. D. (2011). Generational dif-ferences of personal values of business students.American Journal of Business Education,4(9), 19–30.

Gibson, J. W., Greenwood, A., & Murphy, E. F. Jr. (2009). Generational differences in the workplace: Personal values, behaviors, and popular beliefs.Journal of Diversity Management,4(3), 1–8.

HarrisInteractive. (2004). Millennium generation studies: The fifth study conducted for: Northwestern Mutual. Retrieved from http://www. nmfn.com/tn/learnctr–studiesreports–fifth study

Jennings, A. T. (2000, February). Hiring generation-x: The apple doesn’t fall anywhere near the tree anymore.Journal of Accountancy. Retrieved from http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2000/Feb/Hiring GenerationX

Joseph, J., Berry, K., & Deshpande, S. P. (2010). Factors that impact the ethical behavior of college students.Contemporary Issues in Education Research,3(5), 27–34.

Josiam, B. M., Crutsinger, C., Reynolds, J. S., Dotter, T., Thozhur, S., Baum, T., & Devine, F. G. (2009). An empirical study of the work attitudes of generation Y college students in the USA: The case of hospitality and merchandising undergraduate majors.Journal of Services Research,9(1), 5–30.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Trevino, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work.Journal of Applied Psychology,95, 1–31.

Kupperschmidt, B. R. (2000). Multigeneration employees: Strategies for effective management.The Health Care Manager,19(September), 65–76. Mirshekary, S., Yaftian, A. M., & Mir, M. Z. (2011). Students’ perceptions of academic and business dishonesty: Australian evidence.Journal of Academic Ethics,8, 67–84.

Parsons, T. (1951).The social system. London, England: Routledge. Plinio, A. J., Young, J. M., & Lavery, L. M. (2010). The state of ethics in

our society: A clear call for action.International Journal of Disclosure and Governance,7, 172–197.

Pressley, M. M., & Blevins, D. (1984). Student perceptions of ‘job politics’ as practiced by those climbing the corporate career ladder.Journal of Business Ethics,3, 127–138.

Rasch, D., & Guiard, V. (2004). The robustness of parametric statistical methods.Psychology Science,46, 175–208.

Rawwas, M. Y., & Isakson, H. R. (2000). Ethics of tomorrow’s business managers: The influence of personal beliefs and values, individual char-acteristics, and situational factors.Journal of Education for Business,75, 321–330.

Ryan, M. (2000, September 10). Gerald Celente: He reveals what lies ahead.

Parade Magazine, 22–23.

Schewe, C. D., & Noble, S. M. (2000). Market segmentation by cohorts: The value and validity of cohorts in America and abroad.Journal of Marketing Management,16, 129–142.

Shepard, J. M., & Hartenian, L. S. (1990). Egoistic and ethical orientations of university students toward work-related decisions.Journal of Business Ethics,10, 303–310.

Spector, P. E. (1976). Choosing response categories for summated rating scales.Journal of Applied Psychology,61, 374–375.

APPENDIX—Survey Overview

Section I—Perceptions of Ethical Orientation

11 scaled questions (1=always the case; 7=never the case):

“To progress, one has to develop the philosophy that winning is everything.” (Q1)

“The career pressures of advancing leave one with an overdeveloped head and an underdeveloped heart.” (Q2) “One can succeed if one’s work is not the most important thing in one’s life.” (Q3)

“Even though one might say and believe that something like ‘customer satisfaction’ is the primary goal of the organization, one has to develop an attitude that making money is the single most important objective.” (Q4) “One just about has to ‘sell their soul’ to the organization to get ahead.” (Q5)

“To progress, one will occasionally have to indulge in ‘dirty’ tactics.” (Q6) “To advance, the corporation has to come first, even before one’s family.” (Q7) “One cannot progress without ‘stepping on a few people.’” (Q8)

“All personal values have to be set aside in order for one to advance.” (Q9)

“To advance, one has to develop the philosophy that what does not relate to winning and career advancement, including one’s family, does not really matter.” (Q10)

“To climb the ladder, one must not only be prepared to aggressively move past those that stand in the way, but may find it necessary to ‘clear the path.’” (Q11)

1 open-ended question:

“Please use this space to express any related ideas which you desire to share.”

Section II—Demographic Information

College within the university: Major/department:

Classification (i.e., freshman, sophomore, etc.): Age:

GPA:

Religious preference: Social class:

Race: Gender: Citizenship: