Benevolence in Business Marketing

Fred Selnes

NORWEGIANSCHOOL OFMANAGEMENT–BI

Kjell Gønhaug

NORWEGIANSCHOOL OFECONOMICS ANDBUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

The authors address the important issue of how supplier behavior in unexpected problems arise (Kumar et al., 1995). Given that the supplier has a goal to develop and maintain customer

terms of reliability and benevolence creates positive and negative affect,

influences customer satisfaction, and subsequently behavioral intentions loyalty, it is important to understand how reliability and be-nevolence can create such results. The purpose of this article

to be loyal to the supplier. Recent research suggests that affective responses

are important, but has mainly focused on products’ performance in con- is to develop and test a model of how affective and cognitive processes mediate the effect of supplier reliability and

benevo-sumer markets. The authors extend past research by examining affective

and cognitive responses to suppliers’ performance in an industrial context. lence on behavioral intention to be loyal to the supplier. Affective responses have received considerable attention in

In a study of 150 established buyer–seller relationships in the industrial

telecommunication market, they found that customers’ affective responses recent research on consumer satisfaction (e.g., Westbrook, 1987; Westbrook and Oliver, 1991; Oliver, 1993; Mano and

to supplier reliability were different from their responses to supplier

benevolence. Low supplier reliability was found to create negative affect, Oliver, 1993). Despite growing acknowledgment of the impor-tance of affect in consumer markets, modest attention has

while high supplier benevolence created positive affect. Supplier reliability

showed a strong positive effect on satisfaction with the supplier, which been given to affect in industrial markets. Although it does not make sense to talk about feelings as a characteristic of an

subsequently increased loyalty. Supplier benevolence appeared to have

organization itself, members of the organizational buying team

no direct effect on overall satisfaction, but was found to influence customer

may have feelings toward a supplier as an organization.

Indi-loyalty indirectly through positive affect. Thus, both cognitive and affective

viduals involved in decision making are, as reflected in the

processes mediate the effects of supplier reliability and supplier benevolence

buying-center literature, influenced by among other things

on loyalty. J BUSN RES2000. 49.259–271. 2000 Elsevier Science

their subjective experiences (Johnston and Bonoma, 1981;

Inc. All rights reserved.

Kohli, 1989). Although not explicitly discussed in the litera-ture, it is reasonable to expect affective and cognitive responses also to be present in buyer–seller relationships, and to

influ-S

upplier reliability and benevolence have been identifiedence decision making in industrial markets. Anecdotal evi-as two key factors in developing relationships bevi-ased

dence from business practice in industrial markets indicates on trust and commitment (e.g., Kumar, Scheer, and

that marketers exert behaviors that are directed toward af-Steenkamp, 1995). Reliability is the perceived ability to keep

fective responses. an implicit or explicit promise. A supplier is perceived as

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: after reliable when deliveries are made according to contract, when

discussing underlying theory, we develop a model and derive relevant information is provided timely and accurately, when

hypotheses related to affective and cognitive responses to sup-members of the organization are knowledgeable about their

plier behavior. Next, we report the research method used and business and their products, and so on (e.g., Kumar et al.,

the results of the empirical test. Finally we discuss future re-1995; Biong and Selnes, 1997). Supplier benevolence is the

search possibilities and managerial implications of the findings. perceived willingness of the supplier to behave in a way that

benefits the interest of both parties. A supplier is perceived

as benevolent if they are willing to make an extra effort when

Theory and Hypotheses

Supplier Behavior

Address correspondence to Fred Selnes, Professor of Marketing, Norwegian Ravald and Gro¨nroos (1996) propose that customers value School of Management-BI, Oslo, Norway. Tel.: 14722985101; E-mail:

[email protected] not only the focal product, but also the firm supplying the

Journal of Business Research 49, 259–271 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

product or service, and that the two entities represent different while negative and positive cognitions (such as satisfaction processes in creating value. We will focus on the supplier’s and dissatisfaction with a supplier) rarely co-occur (Edell and ability to create value through being reliable and showing Burke, 1987).

benevolence. Clearly, a supplier should be reliable and fulfill Because suppliers should be reliable, it is reasonable to what is promised to the customer. However, a supplier could expect negative emotions to occur when they are experienced be benevolent in situations in which there are no explicit not to be so. Attribution theory may be useful in understanding or implicit promises. More precisely, customers expect the when negative and positive feelings carry over to positive and supplier to solve unpleasant events that cause problems for negative affect toward the supplier (Deighton, 1992; Oliver, them when they believe such events to be within the supplier’s 1997, p. 281–282). The basic point of departure in attribution domain (i.e., within the supplier’s responsibility, whether the theory is that the individual tries to make sense of the social supplier’s promise is explicit or implicit). However, even if context in which he or she is embedded (see Folkes, 1988; unpleasant events are outside the supplier’s perceived respon- Harvey and Weary, 1984 for excellent reviews). Research has sibility, the supplier could help the customer. Showing benev- demonstrated that attributions of motivation may be self-olence is believed to be interpreted differently by the custom- serving or hedonic, typically expressed as attributing favorable ers than is the supplier’s ability to be reliable, and hence outcomes to oneself and unfavorable outcomes to external customers are likely to respond differently toward the seller forces (cf. Miller and Ross, 1975). Deviance from promised in these situations. When the focus is on a single transaction, reliability (“the supplier should”) can be both positive and the distinction between reliability and benevolence will not negative. It follows from attribution theory that negative devi-be important or relevant. However, in the perspective of an ance from what is promised, particularly in routine or ordinary ongoing relationship, the distinction may be crucial. When activities and operations, would be attributed to the supplier. committed to the continuity of a relationship, the supplier Negative experiences may evoke affective responses of negative may be willing to help or surprise positively the customer in valence (e.g., anger). Further, when poor performance is at-other ways, even when such efforts are outside what is implic- tributed to the supplier, the evoked negative feelings would itly or explicitly promised. carry over to the supplier (Oliver, 1993). It also follows from

attribution theory that positive outcomes (i.e., high reliability)

Affective Responses

would be attributed to “self,” that is, the buyer (e.g., “I didCustomers’ affective responses are important for several rea- well because I was careful to choose a good supplier”) or to sons. For example, recent advances in social cognition, cogni- the specific situation (e.g., “I had a lucky day”). In such tive psychology, and social psychology suggest that affective situations, evoked positive affective feelings are not likely to processes constitute not only a powerful source of motivation, be carried over to the supplier.

but is also a major influence on information processing and

H1: Perceived low supplier reliability leads to negative choice (see Lazarus, 1991, for an excellent overview). Affect is

affect toward the supplier. generally understood to comprise a class of mental phenomena

characterized by a consciously experienced, subjective state Because benevolence is likely to be perceived as positive, of feeling, commonly accompanying emotions and moods. showing benevolence is likely to create positive affect. In cases Several taxonomies have been proposed to classify the variety of supplier benevolence (i.e., situations in which “the supplier of subjective feelings into a small set of fundamental, or pri- could”), attribution processes are likely to be different from mary effects (e.g., Izard, 1977). Russell (1980) suggests that experienced reliability. Recall that situations of demonstrated emotions can be described in terms of two primary dimensions benevolence are outside the contract or promise, but still that define a circular configuration, commonly referred to as within the relationship. Experienced benevolence is likely to a circumplex. The dimensions are pleasure/displeasure and be attributed to the supplier and perceived as a friendly act degree of arousal. Westbrook (1987) posited that affect has (e.g., “He didn’t have to help me, but he did.”). Such a positive a similar structure and can be classified according to valence, experience is likely to create positive affective arousal and that is either positive, neutral, or negative. Oliver (1993) found even excitement (Russell, 1980). When the supplier does not that attribute satisfaction and attribute dissatisfaction had help the customer in an unpleasant situation, and thus is not crossover influences on both positive and negative affect. benevolent (only “neutral”), we predict that the outcome is These findings also confirm the “affect-balance theory” pro- likely to be attributed to self and/or situation. We predict that posed by Bradburn (1969), which recognized that positive

the affective arousal in this case is more in the direction of experiences (or positive affect) are not necessarily inversely

depression and sadness attributed to oneself (see also Oliver, correlated with negative experiences (or negative affect),

pre-1997, p. 280), and thus not a negative feeling toward the dicting that positive and negative affect make independent

supplier. contributions to satisfaction (Oliver, 1993). This implies,

H2: Perceived supplier benevolence enhances positive af-among others, that positive and negative affect about an object

(e.g., Hirchman, 1970; Kelly and Thibaut, 1978). When

buy-Cognitive Responses

ers engage in product-related conversations, they seek and Supplier behavior is predicted to influence cognitive responses

give advice about products/services and suppliers. Of particu-in terms of customer satisfaction and behavioral particu-intention.

lar value for the marketer are customers who “witness” posi-Customer satisfaction is believed to be a function of

expecta-tively in favor of the supplier (e.g., Blodgett, Granbois, and tions and experienced performance of a product or service

Walters, 1993; Richins, 1983). Finally, satisfaction with a offering (e.g., Oliver, 1980; Oliver and DeSarbo, 1988).

supplier may result in more business and a stronger commit-Churchill and Surprenant (1982) found that level of

perfor-ment and thus motivation to expand the scope of the relation-mance had a direct effect on satisfaction. Oliver (1997, p.

ship (e.g., Johanson, Halle´n, and Seyed-Mohamed, 1991; Mor-120) reported several other studies showing direct effects from

gan and Hunt, 1994; Gundlach, Achrol, and Mentzer, 1995). performance to satisfaction. Thus, we propose that

perfor-Thus, we hypothesize that: mance of a supplier in terms of reliability and benevolence

will influence satisfaction with the supplier. H7: Customers’ satisfaction with a supplier enhances

be-havioral intention and motivation to be loyal to the

H3: Experienced supplier reliability positively influences

supplier. satisfaction with the supplier.

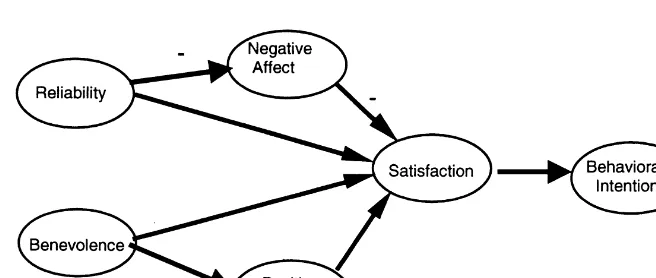

H4: Experienced supplier benevolence positively influ- Figure 1 summarizes the preceding discussion. ences satisfaction with the supplier.

Westbrook (1987) found that positive and negative affect

Methods

carry over to satisfaction, which has been confirmed insubse-The data used to test the hypotheses were collected in a quent studies (Evrard and Aurier, 1994; Mano and Oliver,

telephone survey of business customers of a telecommunica-1993; Oliver, 1993). Thus, we hypothesize that:

tion company. A professional research firm conducted the

H5: Positive affect toward the supplier increases

satisfac-interviews. Because companies differ in their use of telecom-tion with the supplier.

munication products and services depending on the nature

H6: Negative affect toward the supplier reduces satisfac- of the business and the information technology employed, tion with the supplier. they represent a large variety of needs. We wanted the sample of relationships to reflect complexity in interactions between Reichheld (1996) pointed out that customer loyalty should

supplier and customer. In addition, we wanted the sample be the goal of a company and not satisfaction per se. Multiple

to reflect established relationships in which customers had studies have found strong positive relationships between

satis-sufficient experience with the supplier to evaluate relevant faction and behavioral intentions such as expressed future

attributes describing the supplier. To create such a sample of loyalty toward a supplier or product. Customer satisfaction

relationships we asked the company’s account managers to is important for several reasons. In highly competitive markets

provide a list of customers with which they had an established customers will consider alternative sources of supply if not

relationship. A random sample of 250 customer relationships satisfied, particularly when exit barriers from an existing

rela-was drawn from the total list of reported relationships to avoid tionship are modest (cf. Fornell and Wernerfelt, 1987).

En-systematic biases. hanced customer satisfaction is argued to motivate the

cus-We also asked the account managers to provide the names tomer to continue to transact with the supplier (e.g., Fornell,

of the contact persons within the buyers’ organizations. Where 1992; Richins, 1983; Singh, 1988), and conversely to reduce

the likelihood of exit from the relationship with the supplier several contact persons were used, we asked for the name of

the person who had the most formal authority and knowledge positive (POSAFF) and negative (NEGAFF) feelings toward about the focal relationship. Qualitative interviews conducted the supplier (Mano and Oliver, 1993). Although positive and prior to the main study indicated that the identified contact negative affect are negatively related, several studies find that persons had a good overview and knowledge of the relation- these are actually two different constructs (e.g., Bradburn, ship with the supplier and that they were also motivated to 1969; Watson, Clark, and Tellegen, 1988; Russell, 1980), provide the type of information wanted. These observations and thus separate scales for positive and negative affect were are in accordance with the experience of other researchers developed. Construction of the scales started with the list of studying industrial buyer–seller relationships (Anderson and positive and negative items reported by Watson et al. (1988). Weitz, 1989; Heide and John, 1990). Hence, the person con- Qualitative interviews with three customers were conducted tacted was expected to possess the qualifications necessary to to assess the applicability of those items in the study context. serve as key informant (Campbell, 1955). We found that items directed toward a supplier became irrele-The contact persons identified from the supplier’s list were vant when we used terms like “strong,” “proud,” “guilty,” and telephoned. Several callbacks were necessary to increase the

“scared.” After the interviews we decided to keep four positive response rate. However, some prospective respondents were

and five negative items of the original scales. In addition, the not available at the time of data collection. Only a few people

qualitative interviews suggested “useful” as a possible positive refused to answer. All of the qualified persons contacted

evalu-item describing feelings toward the supplier. The positive ated the relationship as complex. A total of 150 respondents

items were: (1) enthusiastic, (2) excited, (3) inspired, (4) completed the interview (i.e., a response rate of 60%). On

interested, and (5) useful. The negative items were: (1) dis-average the interviews lasted about 15 minutes.

tressed, (2) nervous, (3) jittery, (4) irritable, and (5) upset. Respondents were asked to describe the relationship with

Subjects indicated on six-point scales (1 5 “not at all” to the supplier in terms of its relative cost for their firms. On a

65“very much”) the degree to which the specific emotion six-point scale (15“very little,” 65“very much”), the mean

described their feelings toward the supplier. score was 3.61 with a standard deviation of 1.61. Hence,

Satisfaction (SATISFA) is defined as the (cognitive) overall the relationship with the supplier represented on average a

evaluation of the relationship with the supplier. We used substantial cost to the firms investigated. On a similar scale,

three items previously suggested by Fornell (1992), to assess we measured the strategic importance of the relationship. The

satisfaction with the supplier: (1) general satisfaction, (2) con-mean score was 4.46, and skewed toward high importance.

firmation of expectations, and (3) the distance from the cus-Hence, the sample consisted of buyers who viewed the

rela-tomer’s hypothetical ideal supplier. For the first two items, tionships with their supplier as strategically important.

Sev-subjects indicated on six-point scales (15“not at all” to 65

enty-six percent reported that the relationship had lasted 10

“very much”) the degree to which they felt the specific question years or longer.

described their relationship with the supplier. For the third

Development of Measures

item, subjects indicated on a six-point scale the distance from Supplier reliability (RELIAB) is defined as the supplier’s ability an ideal supplier (15“far away” to 65“very close”). to keep their promise. Building on prior work by Kumar et Behavioral intention (BEINTEN) is defined as the motiva-al. (1995) and Biong and Selnes (1997), we used five items tion to be loyal to the supplier. We used four items to assess to capture this construct: (1) ability to deliver according to this variable. First item is intention to change the share of contract; (2) provision of enough and relevant information; (3) business with a supplier (Kumar et al., 1995). We measured trust in provided information; (4) trustworthiness (expertise); this variable on a five-point scale (15“much less than before,” and (5) overall reliability of the supplier. Responses were given 2 5 “less,” 3 5 “about the same,” 4 5 “more,” and 5 5 on six-point scales with endpoint “not at all” (1) and “very “much more”). In line with Hirschman (1970), we measuredmuch” (6). continuity/exit and voice. Continuity/exit was measured with

Supplier benevolence (BENEVOL) is defined as a perceived

one item, the likelihood of exit from the relationship within willingness of the supplier to behave in a way that benefits

two years, on a six-point scale ranging from 1 5 “not very the interest of both parties in the relationship. We adopted

likely” to 65“very likely” (Kumar et al., 1995). In Hirsch-five items used by Kumar et al. (1995) to measure supplier

man’s terminology, voice represents negative reactions toward benevolence. These were (1) willingness to support the

cus-the supplier. In marketing, voice as word of mouth is directed tomer if the environment causes changes; (2) consideration

toward someone other than the supplier, and thus its effects of the customer’s welfare when making important decisions;

are external to the relationship but important to the supplier. (3) responding with understanding when problems arise; (4)

As in previous studies (Blodgett et al., 1993), word-of-mouth consideration of how future decisions and actions will affect

was measured as the likelihood that the customer would give the customer; and (5) dependable support on things that are

positive recommendations if asked for an opinion about the important to the customer. Responses were given on six-point

supplier. Two items were used, one reflecting telling profes-scales with endpoint “not at all” (1) and “very much” (6).

Table 1. Initial Measurement Model—Standardized Coefficients

BEINTEN SATISFA POSAFF NEGAFF RELIAB BENEVOL

SHARE 0.43

EXIT 0.69

POSWO1 –

POSWO2 0.93

SATISFA1 0.82

SATISFA2 0.90

SATISFA3 0.70

POSAFF1 –

POSAFF2 0.83

POSAFF3 0.85

POSAFF4 0.72

POSAFF5 0.73

NEGAFF1 0.77

NEGAFF2 0.72

NEGAFF3 0.88

NEGAFF4 0.84

NEGAFF5 0.89

RELIAB1 0.56

RELIAB2 0.61

RELIAB3 0.68

RELIAB4 0.75

RELIAB5 0.77

BENEVOL1 0.74

BENEVOL2 0.74

BENEVOL3 0.88

BENEVOL4 0.83

BENEVOL5 –

and one related to telling others inside the buyer’s organization ings below 0.7. The loading-matrix is reported in Table 1. We removed SHARE, RELIAB1, RELIAB2, and RELIAB3. The (measured on six-point scales from 15 “not very likely” to

65“very likely”). Thus, the four items reflecting behavioral measurement model was re-estimated with 20 items. The overall fit of the model is still poor and we inspected the intention are: (1) share of supply, (2) exit from the

relation-ship, (3) positive word-of-mouth to external colleagues, (4) modification indexes in order to identify items that appeared to correlate high with other constructs. As modification in-positive word-of-mouth to internal colleagues.

A total of 27 items were used to capture the six constructs. dexes are interrelated we removed items sequentially and re-estimated the model after each removal. This procedure was The means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of

the items are reported in Appendix 1. The correlation matrix repeated until modification indices were below five for all remaining items. In this process we removed POSAFF3, PO-is reported in Appendix 2. To avoid multicollinearity we

re-moved items POSWO1, POSAFF1 and BENEVOL5 as these SAFF5, NEGAFF1, NEGAFF2, NEGAFF4, and BENEVOL2. The measurement model was re-estimated with 14 items and correlated above 0.80 with other items.

Validity of the measurement model was addressed in sev- six latent variables. The overall fit of the purified model is now satisfactory with a chi-square of 102.88 (d.f.5 62 and eral steps. First, by using the maximum-likelihood procedure

in LISREL VIII, we estimated the fit of the measurement model. p 5 0.00086), root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.067, an adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) Second, we removed items that loaded low on their respective

latent variable or items that loaded high on other latent vari- of 0.86, and a normed fit index (NFI) of 0.93. The loading-matrix of the estimated measurement model is reported in ables as indicated by modification indexes (m.i.). Finally we

assessed the overall fit of the purified model. Table 2.

We computed two reliability indices for each construct The initial measurement model consisted of 24 items and

six latent variables. The overall fit of the initial measurement based on the estimated measurement model. The first reliabil-ity measure is a composite score, whereas the second is an model is low, with a chi-square of 920.56 (d.f.5237),

root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.14, an indication of average variance extracted for the construct (Dil-lon and Goldstein, 1984, p. 480). The reliabilities for each adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) of 0.66, and a normed

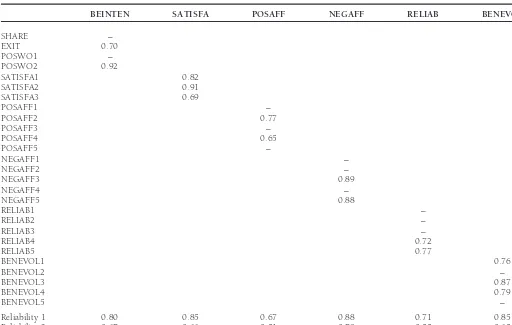

load-Table 2. Estimated Measurement Model: Standardized Coefficients

BEINTEN SATISFA POSAFF NEGAFF RELIAB BENEVOL

SHARE –

EXIT 0.70

POSWO1 –

POSWO2 0.92

SATISFA1 0.82

SATISFA2 0.91

SATISFA3 0.69

POSAFF1 –

POSAFF2 0.77

POSAFF3 –

POSAFF4 0.65

POSAFF5 –

NEGAFF1 –

NEGAFF2 –

NEGAFF3 0.89

NEGAFF4 –

NEGAFF5 0.88

RELIAB1 –

RELIAB2 –

RELIAB3 –

RELIAB4 0.72

RELIAB5 0.77

BENEVOL1 0.76

BENEVOL2 –

BENEVOL3 0.87

BENEVOL4 0.79

BENEVOL5 –

Reliability 1 0.80 0.85 0.67 0.88 0.71 0.85

Reliability 2 0.67 0.66 0.51 0.79 0.55 0.65

or higher which indicate internal consistency among the mea- Although overall fit of the hypothesized model is accept-able, we decided to examine modification indexes to explore sures. POSAFF has reliability 1 coefficient of 0.67, which is

close to the recommended level. All reliability 2 indices were if the model can be improved through better specifications of the structural paths. The examination revealed three potential above the recommended 0.5. In sum, we concluded that the

measurement model was satisfactory. paths with relatively large modification indexes. These were: (1) an effect from positive affect on behavioral intention (m.i5

9.87); (2) an effect from behavioral intention on

satisfac-Results

tion (m.i.5 16.75); and (3) an effect from benevolence on We estimated the hypothesized model by using the maximum- behavioral intention (m.i.510.64). As these were quite large likelihood procedure in LISREL VIII. Supplier behavior perfor- indications that the model was not correctly specified, we mance, RELIAB and BENEVOL were included as exogenous decided to explore how the overall fit could be improved by variables and the others as endogenous variables. The

hypoth-esized model has an acceptable fit with a chi-square of 134.23

(d.f.569), an RMSEA of 0.08, an AGFI of 0.84 and a NFI Table 3. Estimated Structural Model: Standardized Coefficients

of 0.91. Five of the seven structural paths in the hypothesized

Path Standardized t-value

model are statistically significant and in the expected direction

(see Table 3). Neither the direct hypothesized path from be- SATISFA

→BEINTEN BE(1,2) 0.86 8.78** nevolence on satisfaction nor the indirect effect from positive POSAFF→SATISFA BE(2,3) 0.19 0.58 affect on satisfaction is confirmed. Thus the hypothesized NEGAFF→SATISFA BE(2,4) 20.20 23.88**

RELIAB→SATISFA GA(2,1) 0.79 2.16* effect of supplier benevolence on behavioral intention

medi-RELIAB→NEGAFF GA(4,1) 20.56 24.62**

ated through affect and satisfaction is not confirmed. As

ex-BENEVOL→POSAFF GA(3,2) 0.95 8.78** pected, supplier benevolence has a significant effect on posi- BENEVOL

→SATISFA GA(2,2) 20.06 20.12

tive affect. Supplier reliability has an effect on satisfaction, both RELIAB↔BENEVOL PHI(1,2) 0.50 5.96** directly and indirectly through negative affect. As expected,

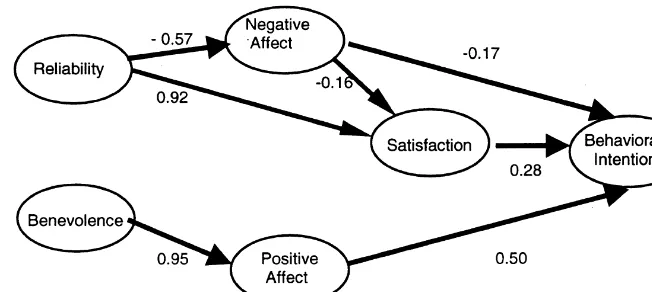

Figure 2. Estimated adjusted model for af-fective and cognitive responses to supplier reliability and benevolence.

following the suggestions given by the modification indexes. tion operate in parallel through both a cognitive and an af-fective process. However, the finding is supported by Zajonc As modification indexes will change depending on new

struc-tural paths we followed a procedure of sequential re-specifica- (1980) who argues that thinking and feeling are two indepen-dent evaluation systems. For supplier reliability, the effect tion. The purpose of our research was to find the mechanisms

by which supplier behavior in terms of reliability and benevo- on behavioral intention works both through satisfaction and through negative affect. This implies, among others, that when lence affects behavioral intentions. Our hypotheses were that

theses effects were mediated through satisfaction as a cognitive the customer dislikes the supplier (negative affect), behavioral intention to be loyal is lower even if the customer is satisfied route from affect to behavioral intention. A competing

hypoth-esis, as discussed in Edell and Burke (1987), is that affect has with the supplier. For supplier benevolence, the effect works only through positive affect. Thus, benevolence appears to an independent route on motivation to be loyal. Thus, we

decided to test out if the effect of positive affect has a direct create liking for the supplier that next may create a kind of bonding to the supplier. This latter bonding may thus operate effect on behavioral intention.

The modified model produced a significantly better fit with even when the customer is not satisfied with the supplier. As can be seen in Figure 2, behavioral intention to be an improved chi-square of 13.01 (d.f.5 1). The structural

path from positive affect on behavioral intention was signifi- loyal appears to be driven highly by affective states, whereas satisfaction (as a cognitive evaluation) appears to have a fairly cant (t53.8). A new inspection of the modification indexes

revealed that only the path from negative affect on behavioral modest effect on intentions of loyal behavior when we control for affects. The effect from positive affect on behavioral inten-intention had a large (greater than five) modification index

(m.i.511.38). Given the competing hypothesis of an inde- tion is 0.50 and the effect from negative affect on behavioral intention is 20.17, whereas the effect from satisfaction is pendent affective route and the suggestion provided by the

modification index, a revised model was estimated where the “only” 0.28. Thus, motivation to be loyal in a buyer–seller relationship appears to be more influenced by affect (i.e., path from negative affect on behavioral intention was opened.

The second modified model also produced a significant liking/disliking the supplier) than by satisfaction with the supplier. The effect of reliability on behavioral intention is improvement in chi-square of 12.15 (d.f.51). Seven of the

nine structural paths in the modified model were significant. 0.446 [(0.92*0.28) 1 (20.57*20.16) 1 (20.57*20.17)] and the effect of benevolence on behavioral intention is 0.475 As in the hypothesized model, the effect from benevolence

on satisfaction and the effect from positive affect on satisfac- (0.95*0.50). Thus, supplier benevolence and reliability ap-pears to have about equal effect in developing buyer–seller tion, were not significant. We finally estimated a revised model

where we closed the two non-significant paths. The fit of the relationships. final modified model produced a satisfactory fit with a

chi-square of 109.53 (d.f.569 andp50.0014), an RMSEA of

Discussion

0.063, an AGFI of 0.87, and a NFI of 0.92. The estimatedinten-inclination to talk favorably about the supplier. Lack of relia- promises. It follows that suppliers should try to understand fully their customer’s expectations to achieve reliability. bility creates negative emotions and negative affect from the

Benevolence, on the other hand, requires a different mana-customer toward the supplier (i.e., dislike) and subsequently

gerial handling than reliability. As opportunities to show be-reduces the motivation to be loyal. Supplier benevolence

ap-nevolence are tied to unpredictable situations in the ongoing pears to invoke a different type of response than supplier

relationship, this kind of behavior must be secured through reliability, and we found that it influences behavioral intention

other mechanisms than standard operating procedures. One to be loyal only indirectly through positive affect. Supplier

way to increase benevolence is to give frontline personnel benevolence thus appears to create a “liking” for the supplier

authority to provide the customer with flexible solutions. An-that promotes loyal behavior independent of the customers’

other avenue may be to create a relationship-oriented culture satisfaction with the supplier.

where benevolent behavior is desired and valued by the orga-With reference to Herzberg’s two-factor motivation hygiene

nization. The supplier need not incur expenses, but should theory (Herzberg, 1966) and Oliver’s (1997, pp. 151–153)

try to be flexible and creative in finding good solutions that discussion of monovalent satisfiers and monovalent

dissatisfi-will benefit both parties. Most importantly is that the custom-ers, we propose that perceived benevolence is a “motivator”

ers should feel that the suppliers care about their problems with a potential to create positive affect, and that perceived

and that they are motivated to help in a manner equivalent reliability is a “hygiene” with a potential to create negative

to friendship. satisfaction and negative affect. For example, a buyer who

Future research should address two issues. First, the exter-thinks a supplier should deliver a product on time will be

nal validity of the findings should be examined through repli-dissatisfied if the delivery is late. Delivery on time (as it should

cations in other industrial settings. The advantage by using be) is expected to have little or no effect on positive affect,

data from only one industry and customers of the same sup-that is liking of the supplier. Showing benevolence is a

psycho-plier, as in the present study, is that the potential confounding logical “extra” (Oliver 1997, p. 152) causing positive affect

effect of the industrial context is reduced. However, a stronger only when fulfilled. For example, if the demand for the buyer’s

test of the model would be to test the hypothesized model product suddenly increases and the additional parts needed

across several industries and types of relationships. Second, exceed the number set in their contract, the supplier could

future research should address how the theoretical constructs charge a higher price for the extra parts. However, the supplier

can be better measured. In particular, we need better measures may demonstrate flexibility and willingness to help, forgoing

of affective states. The measures of affect employed in the a short-term profit. Showing benevolence is likely to cause

present study were borrowed from studies conducted in other positive mental activity similar to gratitude and a sense of

contexts, and in the future we need measures that better friendship.

capture the situation in buyer–seller relationships. An interest-Our findings have several managerial implications. Both

ing approach to develop better affect measures would be to supplier reliability and supplier benevolence is important,

conduct in-depth interviews with buyers and sellers and per-influencing the customer’s motivation to behave loyally toward

form content analysis of their verbal protocols to capture how the supplier. We suspect that most companies have

empha-they describe and understand their business partners. sized development of reliability as indicated by the interest

in ISO certification processes. However, even in professional

The authors are grateful for the financial support from Telenor and valuable

business-to-business relationships the customers value

benev-assistance by Kjetil Aasdal and Tore Haraldstad Sandmoen. The authors thank

olent behavior. The important finding is that the effect of two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments on earlier versions benevolence appears to be about equally strong as the effect of this article.

of reliability. Suppliers should therefore take care to manage both reliability and benevolence in buyer–seller relationships.

References

Avoiding negative affective responses and dissatisfaction canAnderson, Erin, and Weitz, Barton: Determinants of Continuity in

be achieved by carefully monitoring and developing the

relia-Conventional Industrial Channel Dyads.Marketing Science8 (Fall

bility attributes of the supplier. Reliability is for example

im-1989): 310–323.

proved through carefully managing procedures and systems

Biong, Harald, and Selnes, Fred: The Strategic Role of the Salesperson

involved in order-delivery processes and customer service

in Established Buyer-Seller Relationships.Journal of

Business-to-operations. The most important is to fulfill promises, and to Business Marketing3(3) 1997: 39–78. avoid promising what cannot be delivered. An important task

Blodgett, Jeffery G., Granbois, Donald H., and Walters, Rockney G.:

of account managers is therefore to ensure delivery of what The Effects of Perceived Justice on Complainants’ Negative Word-is promWord-ised and orchestrate the daily interaction between the of-Mouth Behavior and Repatronage Intentions.Journal of Retailing two firms (Biong and Selnes, 1997). In addition, managers 69(4) (1993): 399–429.

should be aware that customers often make implicit assump- Bradburn, Norman M.:The Structure of Psychological Well-Being.

Al-dine, Chicago, IL. 1969.

Campbell, Donald T.: The Informant in Quantitative Research.Ameri- Kumar, Nirmalya, Scheer, Lisa K., and Steenkamp, Jan-Benedict E.M.: The Effects of Supplier Fairness on Vulnerable Resellers. can Journal of Sociology60 (1955): 339–342.

Journal of Marketing Research32 (February 1995): 54–65. Churchill, Gilbert A., and Surprenant, Carol: An Investigation into

Lazarus, Richard S.: Cognition and Motivation in Emotion.American the Determinants of Customer Satisfaction.Journal of Marketing

Psychologist46 (April 1991): 352–367. Research19 (November 1982): 491–504.

Mano, Haim, and Oliver, Richard D.: Assessing the Dimensionality Deighton, John: The Consumption of Performance.Journal of

Con-and Structure of Consumption Experience: Evaluation, Feeling, sumer Research19 (December 1992): 362–373.

and Satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research 20 (December Dillon, William R., and Goldstein, Matthew:Multivariate Analysis—

1993): 451–466. Methods and Applications.John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Miller, D.T., and Ross, M.: Self-Serving Biases in Attribution of Cau-1984.

sality: Fact or Fiction.Psychological Bulletin82 (1975): 213–225. Edell, Julie A., and Burke, Marian Chapman: The Power of Feelings

Morgan, Robert M., and Hunt, Shelby D.: The Commitment-Trust in Understanding Advertising Effects.Journal of Consumer Research

Theory of Relationship Marketing.Journal of Marketing58 (July 14 (December 1987): 421–433.

1994): 20–38. Evrard, Yves, and Aurier, Philippe: The Influence of Emotions on

Oliver, Richard L.: Theoretical Bases of Consumer Satisfaction Re-Satisfaction with Movie Consumption.Journal of Consumer

Satis-search: Review, Critique, and Future Directions.Theoretical Devel-faction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior7 (1994): 119–

opments in Marketing, in Charles W. Lamb, Jr., and Patrick M. 125.

Dunne eds., American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL. 1980, Folkes, Valerie S.: Recent Attribution Research in Consumer Behav- pp. 206–210.

ior: A Review and New Directions.Journal of Consumer Research

Oliver, Richard L.: Cognitive, Affective, and Attribute Bases of the 14 (March 1988): 548–565.

Satisfaction Response.Journal of Consumer Research20 (December Fornell, Claes: A National Customer Satisfaction Barometer: The 1993): 418–430.

Swedish Experience. Journal of Marketing 56 (January 1992): Oliver, Richard L.:Satisfaction, A Behavioral Perspective on the

Con-6–21. sumer, McGraw-Hill, New York. 1997.

Fornell, Claes, and Wernerfelt, Birger: Defensive Marketing Strategy Oliver, Richard L., and DeSarbo, Wayne S.: Response Determinants by Customer Complaint Management.Journal of Marketing Re- in Satisfaction Judgments.Journal of Consumer Research14 (March

search24 (November 1987): 337–346. 1988): 495–507.

Gundlach, Gregory T., Achrol, Ravi S., and Mentzer, John T.: The Ravald, A., and Gro¨nroos, Christian: The Value Concept and Relation-Structure of Commitment in Exchange.Journal of Marketing59 ship Marketing. European Journal of Marketing 30(2) (1996):

(January 1995): 78–92. 19–30.

Harvey, J.H., and Weary, G.: Current Issues in Attribution Theory Reichheld, Fredrick F.: Learning from Customer Defections.Harvard and Research.Annual Review of Psychology35 (1984): 427–459. Business Review(March–April 1996): 56–69.

Heide, Jan, and John, George: Alliances in Industrial Purchasing: Richins, Marsha L.: Negative Word-of-Mouth by Dissatisfied Con-The Determinants of Joint Action in Buyer-Supplier Relationships. sumers: A Pilot Study. Journal of Marketing47 (Winter (1983): Journal of Marketing Research54 (February 1990): 24–36. 68–78.

Herzberg, Fredrick: Work and Nature of Man, World Publishing, Russell, James A.: A Circumplex Model of Affect.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology39(6) (1980): 1161–1178.

Cleveland, OH. 1966.

Singh, Jagdep: Consumer Complaint Intentions and Behavior: Defini-Hirschman, Albert O.:Exit, Voice and Loyalty Responses to Declines

tional and Taxonomical Issues.Journal of Marketing 52 January in Firms, Organizations and States.Harvard University Press,

Cam-(1988): 93–107. bridge, MA. 1970.

Westbrook, Robert A.: Product/Consumption-based Affective Re-Izard, Carrol E.:Human Emotions, Plenum Press, New York. 1977.

sponses and Postpurchase Processes.Journal of Marketing Research Johanson, Jan, Halle´n, Lars, and Seyed-Mohamed, Nazeem: Interfirm 24 (August 1987): 258–270.

Adaptation in Business Relationships. Journal of Marketing 55

Westbrook, Robert A., and Oliver, Richard L.: The Dimensionality (April 1991): 29–37.

of Consumption Emotion Patterns and Consumer Satisfaction. Johnston, Wesley J., and Bonoma, Thomas V.: The Buying Center: Journal of Consumer Research18 (June 1991): 84–91.

Structure and Interaction Patterns. Journal of Marketing 45(3)

Watson, David, Clark, Lee Ann, and Tellegen, Auke: Development (1981): 143–156.

and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: Kohli, Ajay: Determinants of Influence in Organizational Buying: A The PANAS Scales.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology54

Contingency Approach.Journal of Marketing53(3) (1989): 50–65. (June 1988): 1063–1070.

Appendix 1. Statistical Metrics of Items

Item Mean S.D. Skewness Kurtosis

SHARE 3.29 1.32 0.22 0.94

EXIT 2.34 1.49 1.09 0.39

POSWO1 3.87 1.31 20.38 20.13

POSWO2 3.93 1.24 20.25 0.03

SATISFA1 4.28 1.14 20.07 0.15

SATISFA2 3.83 1.11 20.15 0.25

SATISFA3 2.92 0.82 0.23 1.85

POSAFF1 3.24 1.18 0.05 20.02

POSAFF2 3.14 1.25 0.51 0.18

POSAFF3 3.31 1.20 20.01 20.09

POSAFF4 4.23 1.09 0.05 0.04

POSAFF5 4.53 1.11 0.15 20.12

NEGAFF1 1.96 1.87 0.40 20.71

NEGAFF2 0.83 1.66 1.03 0.01

NEGAFF3 0.87 1.71 0.92 20.44

NEGAFF4 2.40 1.88 0.02 21.09

NEGAFF5 0.93 1.80 0.85 20.63

RELIAB1 3.93 1.31 0.20 20.18

RELIAB2 3.89 1.31 0.15 20.32

RELIAB3 4.36 1.27 20.12 20.28

RELIAB4 3.86 1.07 20.28 0.13

RELIAB5 4.67 1.27 20.36 0.22

BENEVOL1 4.34 1.26 20.06 20.02

BENEVOL2 3.24 1.43 0.59 20.14

BENEVOL3 4.36 1.57 0.16 20.80

BENEVOL4 3.70 1.24 0.21 0.10

Appendix 2. Correlation Matrix of All 30 Items

SHARE EXIT POSWO1 POSWO2 SATISFA1 SATISFA2 SATISFA3

SHARE 1.00

EXIT 0.18 1.00

POSWO1 0.34 0.63 1.00

POSWO2 0.42 0.65 0.89 1.00

SATISFA1 0.22 0.48 0.67 0.63 1.00

SATISFA2 0.35 0.63 0.73 0.73 0.75 1.00

SATISFA3 0.33 0.45 0.55 0.55 0.55 0.63 1.00

POSAFF1 0.32 0.33 0.60 0.58 0.44 0.51 0.42

POSAFF2 0.32 0.38 0.65 0.66 0.52 0.56 0.46

POSAFF3 0.29 0.34 0.57 0.57 0.41 0.49 0.32

POSAFF4 0.18 0.34 0.54 0.48 0.38 0.38 0.29

POSAFF5 0.27 0.40 0.61 0.60 0.54 0.57 0.47

NEGAFF1 20.33 20.44 20.58 20.60 20.49 20.57 20.52

NEGAFF2 0.01 20.25 20.31 20.30 20.10 20.27 20.21

NEGAFF3 20.20 20.40 20.49 20.49 20.44 20.42 20.43

NEGAFF4 20.42 20.53 20.58 20.59 20.55 20.62 20.52

NEGAFF5 20.23 20.38 20.53 20.51 20.41 20.42 20.35

RELIAB1 0.24 0.29 0.50 0.50 0.36 0.44 0.38

RELIAB2 0.25 0.35 0.47 0.47 0.43 0.38 0.43

RELIAB3 0.28 0.42 0.55 0.51 0.60 0.56 0.50

RELIAB4 0.35 0.46 0.50 0.56 0.53 0.61 0.48

RELIAB5 0.26 0.51 0.53 0.62 0.64 0.64 0.47

BENEVOL1 0.25 0.57 0.57 0.66 0.53 0.60 0.46

BENEVOL2 0.28 0.25 0.39 0.44 0.44 0.42 0.26

BENEVOL3 0.29 0.47 0.65 0.70 0.54 0.61 0.47

BENEVOL4 0.34 0.44 0.56 0.59 0.51 0.52 0.38

BENEVOL5 0.28 0.48 0.64 0.66 0.58 0.60 0.43

J

Busn

Res

F.

Selnes

and

K.

Gønhaug

2000:49:259–271

Appendix 2. continued

POSAFF1 POSAFF2 POSAFF3 POSAFF4 POSAFF5 NEGAFF1 NEGAFF2 NEGAFF3 NEGAFF4 NEGAFF5

SHARE EXIT POSWO1 POSWO2 SATISFA1 SATISFA2 SATISFA3

POSAFF1 1.00

POSAFF2 0.87 1.00

POSAFF3 0.85 0.80 1.00

POSAFF4 0.52 0.50 0.61 1.00

POSAFF5 0.47 0.49 0.53 0.74 1.00

NEGAFF1 20.40 20.37 20.38 20.36 20.35 1.00

NEGAFF2 20.08 20.05 20.06 20.11 20.19 0.50 1.00

NEGAFF3 20.21 20.23 20.22 20.22 20.35 0.70 0.74 1.00

NEGAFF4 20.41 20.45 20.38 20.33 20.36 0.73 0.51 0.69 1.00

NEGAFF5 20.29 20.30 20.22 20.31 20.27 0.61 0.69 0.79 0.78 1.00

RELIAB1 0.41 0.43 0.37 0.35 0.35 20.31 0.00 20.13 20.38 20.31

RELIAB2 0.41 0.52 0.38 0.36 0.42 20.41 20.17 20.38 20.38 20.39

RELIAB3 0.35 0.43 0.32 0.27 0.41 20.47 20.10 20.31 20.43 20.37

RELIAB4 0.47 0.50 0.41 0.43 0.55 20.45 20.24 20.31 20.43 20.38

RELIAB5 0.42 0.51 0.46 0.42 0.51 20.44 20.12 20.32 20.55 20.41

BENEVOL1 0.49 0.49 0.55 0.56 0.59 20.44 20.19 20.30 20.45 20.33

BENEVOL2 0.47 0.50 0.58 0.39 0.49 20.35 0.05 20.05 20.30 20.12

BENEVOL3 0.57 0.60 0.61 0.52 0.59 20.46 20.20 20.20 20.43 20.26

BENEVOL4 0.54 0.59 0.60 0.48 0.57 20.32 20.08 20.23 20.50 20.30

BENEVOL5 0.56 0.63 0.65 0.56 0.64 20.44 20.14 20.25 20.46 20.23

271

Supplier

Reliability

and

Benevolence

J

Busn

Res

2000:49:259–271

Appendix 2. continued

RELIAB1 RELIAB2 RELIAB3 RELIAB4 RELIAB5 BENEVOL1 BENEVOL2 BENEVOL3 BENEVOL4 BENEVOL5

SHARE EXIT POSWO1 POSWO2 SATISFA1 SATISFA2 SATISFA3 POSAFF1 POSAFF2 POSAFF3 POSAFF4 POSAFF5 NEGAFF1 NEGAFF2 NEGAFF3 NEGAFF4 NEGAFF5

RELIAB1 1.00

RELIAB2 0.44 1.00

RELIAB3 0.40 0.53 1.00

RELIAB4 0.37 0.56 0.51 1.00

RELIAB5 0.39 0.41 0.48 0.55 1.00

BENEVOL1 0.40 0.39 0.38 0.55 0.57 1.00

BENEVOL2 0.36 0.24 0.20 0.39 0.48 0.54 1.00

BENEVOL3 0.48 0.41 0.48 0.60 0.59 0.62 0.64 1.00

BENEVOL4 0.43 0.29 0.41 0.46 0.61 0.56 0.72 0.73 1.00