www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Taste reactivity patterns in domestic cats

ž

Felis sil

Õ

estris catus

/

Ruud Van den Bos

), Margot K. Meijer, Berry M. Spruijt

Animal Welfare Centre, Utrecht UniÕersity, Yalelaan 17, NL-3584 CL Utrecht, NetherlandsAccepted 9 March 2000

Abstract

Ž

The present study is aimed at finding taste reactivity patterns in domestic cats Felis silÕestris

.

catus which reflect ‘liking’ or perceived palatability. Three groups of nonstressed cats living in households were formed which a priori were expected to differ in motivational state for eating

Ž .

food items more or less hungry , and which were offered two different food items differing in

Ž .

general taste properties more or less flavourful food, MFF and LFF, respectively around the time that they were fed their normal food. Analysis of the amount of food eaten showed that MFF was consumed regardless of hunger level and that LFF was consumed depending on the hunger level of cats: the more hungry cats ate more of LFF than the less hungry cats. Analysis of post-meal behavioural sequences showed that the ‘MFF consumption sequence’ differed from the ‘LFF refusal sequence’ and that the ‘LFF consumption sequence’ strongly resembled the ‘MFF consumption sequence’ but also contained elements of the ‘LFF refusal sequence’. Subsequent analysis of the frequencies and total durations of behavioural patterns showed that two kinds of patterns existed, possibly reflecting two ‘palatability dimensions’: hedonic taste reactivity patterns

Žlickrsniff feeding bowl, lip lick and groom face and aversive taste reactivity patterns lick. Ž rsniff

.

food and lick nose . These dimensions may be combined to obtain a single palatability score.

q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Cat; Palatability; Taste reactivity patterns; Welfare

1. Introduction

Ž .

Vertebrates possess a system to maintain the balance between positive ‘satisfaction’

Ž .

and negative ‘stress’ experiences to make efficient use of resources against the

Ž .

background of changing environmental conditions incentivesrstressors and changing

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q31-30-2534-373; fax:q31-30-2539-227.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] R. Van den Bos .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

internal physiological conditions, and to estimate costs and benefits prior to taking

Ž .

action Spruijt et al., 2000; Mason et al., 1997 . The reward system, supporting the ‘satisfaction-component’ of this system, consists of two parts which can be

sepa-Ž

rated conceptually, neurobiologically and behaviourally Berridge, 1996; Berridge and .

Robinson, 1998; Fraser and Duncan, 1998; Spruijt et al., 2000 : one part, which deals

Ž .

with the immediate appreciation of commodities likingrdisliking , and one part which

Ž .

deals with the disposition to act upon this appraisal in future wanting . It should be noted that ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ do not point to self-conscious or second-order intentional processes but rather to first-order intentional or goal-directed processes ŽBerridge and Robinson, 1998; Van den Bos, 1997, 2000; Dickinson and Balleine, 1994;

. Heyes and Dickinson, 1990 .

The present study concentrated solely on the immediate appreciation of a commodity itself. This appraisal is determined after the commodity’s ‘consumption’ and dependent on several factors such as motivational state, previous experience and general properties

Ž .

of the commodity Grill and Berridge, 1985 . The commodity in this study is food. As

Ž . Ž .

shown in rats, the incentive value ‘liking’ or perceived palatability of food items can be measured by the occurrence of discrete behavioural patterns, i.e. taste reactivity patterns: ‘‘taste reactivity patterns must be regarded as true affective reactions, which

Ž

connote core processes of affective ‘liking’ versus ‘disliking’’’ italics in the original text omitted; Berridge, 1996; Berridge and Robinson, 1998, p. 355; Grill and Berridge,

.

1985; Grill and Norgren, 1978 . More specifically, it has been shown that two types of Žsequences of patterns exist: hedonic patterns and aversive patterns. These have been. obtained by analysing the rats’ behaviour after forced intra-oral infusion of solutions,

Ž . Ž . Ž

which were subsequently ingested e.g. sucrose solution or rejected e.g. quinine .

solution . It has been shown that the expression of these patterns is affected by the motivational state of the animals, such as revealed by manipulating the deprivational state of animals, and the previous experiences with food items, such as revealed by the

Ž .

conditioned taste aversion paradigm Grill and Berridge, 1985 . For instance, it has been

Ž .

shown that as animals are or become satiated, less hedonic and more aversive taste reactivity patterns to the same stimulus are shown, suggesting a change in ‘liking’ or

Ž

perceived palatability Grill and Berridge, 1985, p. 16; Cabanac and Lafrance, 1990,

. Ž .

1991, 1992; Berridge, 1991 . Cabanac 1971, 1979, 1992 observed the same phe-nomenon in humans, using verbal ratings of pleasantness in response to stimuli, and labelled it alliesthesia: ‘a given stimulus can induce a pleasant or unpleasant sensation

Ž

depending on the subject’s internal state’ Cabanac, 1971, p. 1107; Berridge, 1996, p. 2, .

1991, p. 103 .

To study such patterns in cats, therefore, different groups of cats were studied which

Ž .

had different motivational states more or less hungry and received two different food

Ž .

items more or less flavourful under the following hypothesis: palatability is dependent

Ž Ž .

on general features of the food item external: more flaÕourful food MFF than average

Ž . .

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

In order to form a uniform group of nonstressed animals, with no a priori changed sensitivity to the taste of food items, we sought domestic cats which had — in principle

Ž .

— to comply with the following criteria: 1 be of known origin and not separated from their mothers before the age of 8 weeks, since early separation may change the

Ž . Ž .

sensitivity of the stress system Liu et al., 1997 ; 2 be older than 1 year to discard any Ž .

effects due to maturation; 3 be neutered, since, e.g. the oestrus cycle may affect

Ž . Ž . Ž .

palatability Cabanac, 1979 ; 4 be able to go outside regularly; 5 not have had a history of serious illnesses, allergies or problem behaviour such as overgrooming,

Ž

aggression or overeating, which may indicate a history of chronic stress Bolka, 1984; . Ž .

Willemse et al., 1994 ; 6 not being a pedigree cat, since some breeds may have an

Ž .

altered sensitivity to stressors and rewards Van den Bos, in preparation .

Originally, 27 cats were selected. However, four cats were rejected after or during testing. Of one cat, it proved to be very likely that it had had a history of overgrooming. The other three cats proved to be too nervous of the observer or would not eat at all

Ž

during the observations. The remaining 23 cats 16 castrated males, six spayed females .

and one intact female were recruited from 18 households, varying between students’ houses and single-family homes, located in urban settings in the Netherlands. Of these cats, 10 were the only cat in the household, 12 were from two-cat households and one was from a three-cat household. Ten cats were living in households together with other animals, e.g. dogs and rodents.

Four cats did not comply to all criteria: one cat was taken out of a cat shelter at the age of one. According to the owner, direct examination by the veterinarian had not revealed any signs of stress, e.g. due to early separation of the mother. One cat had only free access to the roof of the block of houses where it lived and was allowed to go outside on the street about one night a week. One 2-year old female cat was not spayed.

Ž .

She was administered anticonception ‘cat pill’ the first year and had not been in oestrus the second year. One cat was born in Africa and brought to Europe as the owners moved. Its mother was a European shorthair cat, the father was of unknown origin and may therefore have been a wild cat. However, it has been found that male cats may pass on the tendency to be friendly to people to their offspring without ever coming into

Ž .

social contact with them Turner et al., 1986 . This particular cat was very sociable

Ž .

towards humans suggesting that its father was a domesticated nonwild cat. In order to be sure that the data of these cats would not confound the data of their respective

Ž .

groups, an outlier test was performed per group see below .

Ž .

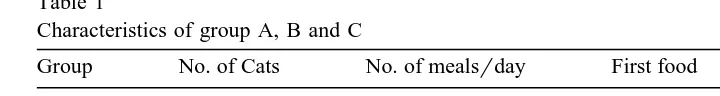

The cats were divided over three groups Table 1 . Because four cats were rejected

Ž .

afterrduring testing, the groups differed in size 5, 8 and 10 cats, respectively . Groups Ž

A and B consisted of cats that were fed one to three meals a day dry food or canned .

Table 1

Characteristics of group A, B and C

Group No. of Cats No. of mealsrday First food Second food

A 5 1–3 Normal Experimental

B 8 1–3 Experimental Normal

C 10 Ad libitum Experimental Normal

2.2. Test procedure

All cats were tested twice at their owners homes. During each test session, the cats were presented two types of food: the food they were usually fed at that time of day Žnormal food: NF and one of the two experimental foods one food being more. Ž

Ž . Ž ..

flavourful than average MFF , the other one less flavourful than average LFF . Cats of group A were presented NF as the first food and an experimental food as the second food. Cats of groups B and C were presented an experimental food as the first food and NF as the second food. Each cat was fed MFF during one test session and LFF during the other. The intersession interval was at least 2 weeks. To be sure that the cats’ response to the different types of experimental food was not influenced by the order in

Ž

which they were presented, each group was divided into two subgroups group A: three .

versus two; group B: five versus three; group C: five versus five . One subgroup was fed MFF during the first session and LFF during the second session; the other subgroup was fed MFF and LFF in the reverse order.

All food items were presented at room temperature. NF was presented in the cat’s own feeding bowl, MFF or LFF was presented in a feeding bowl that was brought by the observer.

It should be noted that cats of group A and C were fed the experimental food while

Ž . Ž .

they were supposed to be more or less satiated created through different conditions , whereas cats of group B were fed the experimental food while they were supposed to be Žmore or less hungry..

2.3. Food items

NF was either dry or canned cat food of a brand and taste the cat was used to be fed Žall brands were commercially available . The normal amount of food was presented. If. the cat was only fed dry food ad libitum, a full feeding bowl was supplied. MFF was

Ž

;50 g of Sheba Trout a commercially available premium quality product on a meat .

and fish base . This product proved in other experiments to be highly appreciated by cats ŽVan den Bos et al., unpublished data . LFF was. ;50 g of a cheap canned cat food that

Ž .

was mixed with ;30 drops of orange essence Genfarma, Houten, the Netherlands .

Ž .

Pilot experiments had shown this to be a useful LFF as it turned out to be less or un-flavourful, but not uneatable. Furthermore, it was a completely harmless product.

Ž

It should be noted that in contrast to experiments in rats Berridge, 1996; Berridge .

reasons for this are as follows. First, cats appear to be rather insensitive to sucrose’s

Ž .

taste Bartoshuk et al., 1971; Beauchamp et al., 1977; Bradshaw, 1992 . Second,

Ž .

although cats do show an aversion to quinine Bradshaw et al., 1996 , the use of quinine would have discouraged the owners to allow their cats to participate in experiments. The

Ž

same applies to the use of sweet- and bitter-tasting amino acids White and Boudreau, .

1975 .

2.4. Recording procedure

All observations were done by the second author and were arranged in advance. The observations were done on weekdays between 1500 and 2100 hours, around the time the

Ž .

cats were usually fed. Cats of group C with dry food ad libitum were observed at the time that they were fed canned food. If only fed dry food ad libitum, no special time point was chosen.

Ž

Before observations started, the owners defined as the persons normally feeding the .

cats were instructed to present or take away the feeding bowls at a signal of the observer, and were asked to try not to talk loudly or make sudden noises and not to stroke the cats during the observations. The cats were not able to leave the room during the observations. Cats of multi-cat households were fed separately to prevent cat–cat interactions.

The test sessions were composed of two parts: presentation of the first food item at

Ž .

ts0 min maximal presentation duration: 10 min and presentation of the second food

Ž .

item starting at ts15 min latest maximal presentation duration: 10 min . The be-haviour of the cats was recorded throughout the session. Observations started when the first food item was presented to the cat and the cat was aware of it. For both food items, if necessary, the cat’s attention was drawn by calling the cat and showing the food item; in a few cases, when the cat was reluctant to come, it was picked up by its owner and placed next to the feeding bowl. In practice, this never happened for the first food item, and only a few times for the second. For both food items, 5 min of post-meal behaviour Žperiod cf. Bradshaw and Cook, 1996 were sampled as follows: either when cats.

Ž

stopped eating and did not return to the food bowl within 5 min which was subse-.

quently taken away after 5 min of recording , or in case cats ate nothing at all, from the Ž

time-point on that they had sniffed the food and went away again the food bowl was .

taken away after 5 min . When the cats did not finish eating after 10 min of food

Ž .

presentation see above , or kept returning to the bowl before 5 min of recording passed and after 10 min of food presentation had passed, the bowl was taken away and 5 min were sampled from thereon. The latter happened only once. The maximal test session duration was 30 min.

Total duration, frequencies and sequences of behaviour patterns were recorded during Ž

the entire period. Recording was done using a handheld computer Psion Workabout;

. Ž

Psion, London, England loaded with The Observer, version 3.0 Noldus Information .

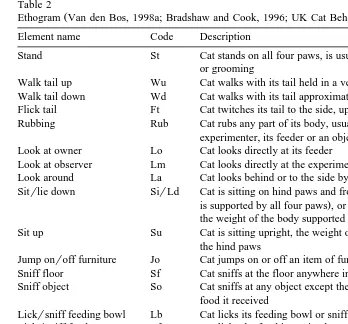

Table 2

Ž .

Ethogram Van den Bos, 1998a; Bradshaw and Cook, 1996; UK Cat Behaviour Working Group, 1995

Element name Code Description

Stand St Cat stands on all four paws, is usually alert but not looking round or grooming

Walk tail up Wu Cat walks with its tail held in a vertical position Walk tail down Wd Cat walks with its tail approximately horizontal Flick tail Ft Cat twitches its tail to the side, upwards or downwards Rubbing Rub Cat rubs any part of its body, usually head, flank or tail, on the

experimenter, its feeder or an object Look at owner Lo Cat looks directly at its feeder Look at observer Lm Cat looks directly at the experimenter

Look around La Cat looks behind or to the side by moving its head regularly

Ž

Sitrlie down SirLd Cat is sitting on hind paws and front paws the weight of the body

.

is supported by all four paws , or is lying on its side or back, the weight of the body supported by the body rather than the paws Sit up Su Cat is sitting upright, the weight of the body is supported by

the hind paws

Jump onroff furniture Jo Cat jumps on or off an item of furniture Sniff floor Sf Cat sniffs at the floor anywhere in the room

Sniff object So Cat sniffs at any object except the floor, its feeding bowl and the food it received

Lickrsniff feeding bowl Lb Cat licks its feeding bowl or sniffs at it Lickrsniff food Lf Cat licks the food it received or sniffs at it

Eat Ea Cat eats from the food it received

Lick nose Ln Cat flicks its tongue quickly over its nose Lick lip Ll Cat flicks its tongue around the outside of its mouth Lick paw Lp Cat licks one of its front paws without passing it over its head Groom facial area Gf Cat grooms its facial area by passing a previously licked

paw over its head

Groom chestrgroom body GcrGb Cat grooms its chest or any part of its body except front paws and face

Other behaviour Ot Everything the cat does that is not described in this table

presentation. It was denoted whether the cat had eaten all, a part or nothing of the food items.

2.5. Data analysis

Ž For every cat, 5 min of post-meal behaviour after each of the four food items two

. times experimental food, once MFF and once LFF, and two times normal food were

Ž .

analysed. Data of different cats were combined in Excel 97 Microsoft and were tested

Ž .

for significant differences pF0.05; two-tailed unless otherwise stated in SPSS Žstandard version, release 7.5 using Mann–Whitney U-test for independent samples. Ždata of different cats. and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test in case of

Ž . Ž .

correlated samples data derived of one and the same cat Ferguson, 1981 . Nonpara-Ž .

metric statistics over parametric statistics were chosen since 1 group A contained only

Ž . Ž .

some data were not expected to be normally distributed, e.g. durations of behaviour

Ž .

patterns are limited to 300 s 5 min , favouring nonparametric statistics. Therefore, all data are presented as medians instead of means. Total duration and frequencies of post-meal behaviour were tested for outliers using the ‘Explore: Statistics’ function of SPSS.

Sequences of events of 5 min post-meal behaviour of MFF or LFF were obtained by generating transition matrices for each group of cats. Matrices were edited and tested for

Ž

significant transitions in Matman version 1.0 Noldus Information Technology,

Wa-. Ž .

geningen, the Netherlands . Significant transitions pF0.05–0.001 were detected

Ž .

using the chi-square x2 test followed by the adjusted residuals procedure in Matman.

Ž .

Sign tests Ferguson, 1981, pp. 401–402 were used to test for differences between

Ž .

the amounts of MFF and LFF, and normal food before or after MFF NF-MFF and

Ž .

normal food before or after LFF NF-LFF eaten per cat within the three groups. Per group, it was scored in how many cases a cat ate more of MFF than of LFF and more of NF-MFF than of NF-LFF. Between groups x2 tests were used.

3. Results

3.1. General

Ž .

To test for order effects MFF before LFF and vice versa total duration and frequencies of post-meal behavioural patterns for each of these subgroups for each of the four food items were tested against one another. In groups B and C, no significant

Ž .

differences were found p)0.05; Mann–Whitney U-test . Group A contained too few cats to run a meaningful analysis, but no differences appeared to be present upon visual inspection of the data. Therefore, results of the cats within one group were pooled.

Furthermore, total duration and frequencies of post-meal behaviour were tested for outliers. Special attention was paid to the four cats that did not comply with all selection criteria. No outliers were detected.

3.2. Amount of the food items eaten and latencies to eating MFF and LFF

Ž

In group A, more MFF than LFF tended to be eaten per cat sign-test: zs1.5, .

pF0.14 whereas no difference was observed between the amount of NF-MFF and

Ž .

NF-LFF eaten per cat zs0, n.s.; Table 3 . In group B, no differences were detected

Ž .

between the amount of MFF and LFF eaten per cat zs1.15, n.s. , or NF-MFF and

Ž .

NF-LFF eaten per cat zs0.58, n.s. . In group C, more MFF than LFF was eaten per

Ž . Ž .

cat zs2.67, pF0.01 as well as more NF-LFF than NF-MFF zs2.04, pF0.05 . No differences were observed as to the amounts of MFF eaten per cat between

Ž .

of LFF than cats in group A this difference did not reach significance x2s3.18, .

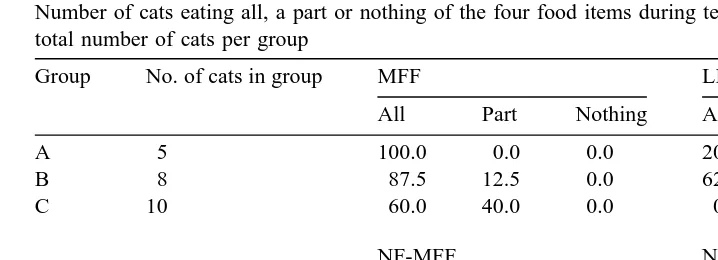

Table 3

Number of cats eating all, a part or nothing of the four food items during testing expressed as percentages of total number of cats per group

Group No. of cats in group MFF LFF

All Part Nothing All Part Nothing

A 5 100.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 20.0 60.0

B 8 87.5 12.5 0.0 62.5 0.0 37.5

C 10 60.0 40.0 0.0 0.0 30.0 70.0

NF-MFF NF-LFF

All Part Nothing All Part Nothing

A 5 60.0 40.0 0.0 40.0 60.0 0.0

B 8 62.5 25.0 12.5 75.0 25.0 0.0

C 10 20.0 40.0 40.0 40.0 60.0 0.0

Ž

cats in group C this did not reach significance x2s3.58, dfs2, n.s. and x2s2.22, .

dfs2, n.s. .

In group A, it was not possible to measure the latencies for eating MFF or LFF precisely, since these food items were presented as the second food item, and therefore the exact moment the cat was presented the food item was never the same. In group B,

Ž . Ž

the latency to eating MFF median: 0.0 s was shorter than to eating LFF 170.1 s; .

Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test: zs y2.52, pF0.05 . The same was true

Ž .

for group C: MFF, 2.2 s versus LFF, 300.0 s zs y2.81, pF0.01 . There were no Ž differences in latency to eating either MFF or LFF between groups B and C Mann–

. Whitney U-tests, n.s. .

Of the five cats of group B that did eat LFF, 81.6% of the time spent before eating

Ž .

LFF median value consisted of sniffing and licking at the food. The three cats of group C that ate from the LFF were spending 84.7% of the latency period by sniffing and

Ž .

licking at it median value . The percentages of time spent on licking or sniffing at LFF

Ž .

of group B and C were not significantly different Mann–Whitney U-test, n.s. .

3.3. Sequences of behaÕioural patterns

Post-meal behavioural patterns were recorded as a sequence of events. Transition probabilities of behavioural patterns for each group of cats were calculated for both MFF and LFF. There was a strong resemblance between the resulting sequences for the different groups in terms of general patterns, and the behavioural events at the beginning and end of the sequences. Therefore, the results of all the cats were pooled resulting in one sequence for post-meal behaviour of MFF and one sequence for post-meal

be-Ž . Ž .

haviour of LFF. In the matrix of MFF in total 441 cells , 200 cells 45.4% had a value

Ž . Ž

of zero and 147 cells 33.3% had a value of F5. In the matrix of LFF in total 441

. Ž . Ž .

To test if the resulting sequences were however representative for common cat post-meal behaviour, ‘split half tests’ were performed. This means that transition probabilities were

Ž

calculated again, using the results of only half the number of animals ns11 and .

ns12 cats; the distribution of cats over the two halves was randomly assigned , leading to two ‘new’ sequences for both MFF and LFF. The resulting split-half sequences resembled the original sequences. Therefore, it can be assumed that if a larger group of cats was used and thus a higher number of behavioural events would emerge, the sequence would not have changed very much either.

Ž

The sequences of MFF and LFF are shown in Fig. 1 both matrices were significant:

x2s2064.4, dfs341, zs38.2, pF0.001 and x2s1692.5, dfs419, zs29.3, .

pF0.001, respectively, Ferguson, 1981, p. 204 . Both sequences started with activities Ž

around the feeding bowl such as lickrsniff food 56.5%, only displayed when LFF was

. Ž

presented , lickrsniff feeding bowl 26% when presented LFF and 47.8% when

. Ž

presented MFF and sniff floor 21.7% when presented MFF; this pattern could be displayed anywhere in the room but was most frequently seen in close proximity of the feeding bowl; percentages were calculated as the number of times the patterns were marked as the first event in the individual sequences as a proportion of the total number

Ž ..

of individual sequences ns23 . The activities around the feeding bowl were followed by a period of walking around, exploration of the room and interaction with the owner andror the observer. Near the end of the sequences a period of grooming occurred, which was normally done while the cat sat, therefore sit up is closely associated with the different grooming behaviours. The sequence was usually ended by sit or lie down Ž17.4% and 21.7% when presented MFF or LFF, respectively , sit up 30.4% when. Ž

. Ž .

presented MFF , lick paw 8.7% when presented MFF or groom chestrgroom body Ž8.7% when presented LFF; percentages were calculated as the number of times the patterns were marked as the last event in the individual sequences as a proportion of the

Ž ..

total number of individual sequences ns23 .

The MFF and LFF sequences showed a number of differences. Lick nose was only present in the LFF sequence. Furthermore, the LFF sequence started with either lickrsniff feeding bowl or lickrsniff food while the MFF sequence started with lickrsniff feeding bowl only. Considering the fact that only 10 of the 23 cats ate LFF, it

Ž .

was decided to see whether the behavioural sequence of the cats ns10 that ate LFF Žall of it or only a part. was different from the behavioural sequence of the cats Žns13 that did not eat any LFF in terms of, e.g. these initial behavioural patterns..

Ž

Both matrices were significant: x2s986, dfs419, zs15.5, pF0.001 cats eating

. Ž

LFF, ns10 and x2s1045.9, dfs419, zs16.8, pF0.001 cats not eating LFF,

. Ž .

ns13 . The sequence of the cats that ate no LFF at all LFF refusal sequence started Ž

with lickrsniff food 100%; lickrsniff feeding bowl was only recorded twice in these

. Ž .

cats , while the sequence of the cats that did eat LFF LFF consumption sequence Ž

started with lickrsniff feeding bowl 60%; lickrsniff food was only recorded three

. Ž .

times in these cats or sniff floor 20% similar to after eating MFF. Furthermore, the ‘LFF consumption sequence’ but not the ‘LFF refusal sequence’ resembled the ‘MFF

Ž .

3.4. Total duration and frequencies of behaÕioural patterns

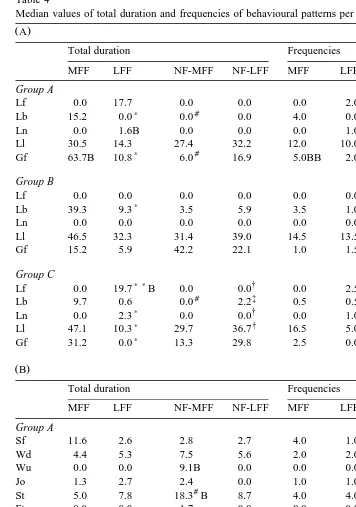

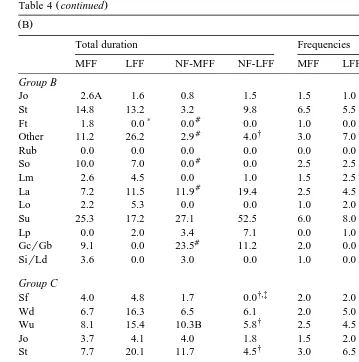

In Table 4, total duration and frequencies of behavioural patterns for the different food items are presented per group. For ease of presentation and subsequent discussion, Table 4A contains only those behavioural patterns that showed consistent differences over the groups and food items, i.e. the patterns that were in line with our hypothesis. The data of the remaining behavioural patterns are listed in Table 4B. Neither the data of MFF and NF-LFF, nor the data of LFF and NF-MFF were compared with one another since this would not give any extra useful information. The most relevant differences between food items within the groups will be summarised per group.

3.4.1. Group A

The cats of group A, which were normally fed one to three meals a day and which started both observations with their normal food, showed no differences in behavioural patterns between NF-MFF and NF-LFF. In group A, total duration and frequency of groom face were significantly increased after MFF when compared to after LFF, and to after NF-MFF. Except for the frequencies of MFF and LFF the same was true for lickrsniff feeding bowl. The frequency of groom chestrgroom body was significantly increased after MFF when compared to after NF-MFF.

3.4.2. Group B

In group B, the cats were normally fed one to three meals a day and started the observations with one of the experimental food items. Total duration of lickrsniff feeding bowl was significantly increased after MFF compared to after LFF. The frequency of lickrsniff feeding bowl after MFF was significantly higher compared to after NF-MFF. The frequency of sniff floor was significantly increased after MFF when compared to after NF-MFF as well as after LFF when compared to after NF-LFF. Total duration of sniff floor after LFF was significantly higher than after MFF. Finally, total duration of groom chestrgroom body after NF-MFF was significantly increased when compared to after MFF.

3.4.3. Group C

Group C consisted of cats fed ad libitum by their owners and started the observations with one of the experimental food items. Total duration and frequency of lickrsniff food after LFF were significantly increased when compared to after MFF, and to after

Fig. 1. Post-meal transition probabilities between behavioural patterns after different food items. Abbreviations of patterns are found in Table 2. Frequencies are shown between brackets. Sequences start at the top

Žunderlined behavioural patterns and end at the bottom underlined behavioural patterns . Panel A: Presumed. Ž .

Ž .

sequence of patterns after MFF Sheba trout . Data of groups A, B and C combined to reveal one sequence

Žns23 cats, 1661 transitions, see text . Panel B: Presumed sequence of patterns after LFF common brand. Ž

. Ž

with drops of orange essence . Data of groups A, B, and C combined to reveal one sequence ns23 cats,

.

1629 transitions, see text .

Table 4

Median values of total duration and frequencies of behavioural patterns per food item per group

Ž .A

Total duration Frequencies

MFF LFF NF-MFF NF-LFF MFF LFF NF-MFF NF-LFF

Group A

MFF LFF NF-MFF NF-LFF MFF LFF NF-MFF NF-LFF

Ž .

Table 4 continued

Ž .B

Total duration Frequencies

MFF LFF NF-MFF NF-LFF MFF LFF NF-MFF NF-LFF

Group B

Symbols indicate the level of significance between food items Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test .

Ž .

Capitals refer to differences between food items of groups Mann–Whitney U-test ; single capital: pF0.05,

Ž .

double capital: pF0.01. Capitals are placed near the highest value. In A , patterns are shown of which the

Ž .

changes over food items and groups are consistent with the hypothesis formulated in Section 1, in B patterns

Ž .

which are not see text for discussion . For abbreviations of behavioural patterns, see Table 2.

) Ž .

3.5. Differences between the groups

The frequencies and total duration of lick paw and groom face and the frequency of groom chestrgroom body after MFF were higher in group A compared to group B. Furthermore, total duration and frequency of lick nose were increased after LFF in group A when compared to group B. In group C, total duration of lickrsniff food after LFF was increased when compared to group B.

4. Discussion

4.1. General

As a working hypothesis, it was formulated that the hungrier cats are, the more likely it is that they will eat LFF and the more the behavioural patterns which normally belong to MFF they will show, i.e. show hedonic taste reactivity patterns; and conversely the less hungry cats are, the less likely they will eat LFF and the more behavioural patterns which belong to LFF they will show, i.e. show aversive taste reactivity patterns. The fact that the experiments were run in domestic cats living in households precluded any forced feeding techniques, the use of potentially harmful food items or deprivation

Ž .

regimes Grill and Berridge, 1985; Grill and Norgren, 1978 for review which would allow for a more straightforward testing of this hypothesis and assessment of taste reactivity patterns. For instance, these techniques do not suffer from the confounding effect that animals e.g. refuse to eat for reasons not associated with the experiment. In this study, three cats were discarded from the experiments for this reason. Still, by prior

Ž . Ž .

selection of the general external taste of a food item and the internal motivational state of the individual animal, the present study showed that distinct behavioural patterns, i.e. hedonic and aversive taste reactivity patterns, exist for food items which are indicative for the perceived palatability or ‘liking’ thereof. It should be noted that all cats did have contact with the food items even in case they did not eat it. In the latter case, they would sniff at it.

4.2. MotiÕational states and food items

Groups of cats were formed which were a priori expected to differ in internal Žphysiological state hunger level and food items were chosen — based on pilot. Ž . experiments — which would allow to elicit both kinds of taste reactions, and in conjunction with one another allow changes from one kind of reaction to the other using

Ž .

the same food item stimulus . Indeed, the amounts of MFF and LFF that the cats ate

Ž . Ž

showed that the prior selection of food items MFF and LFF and internal physio-.

logical, motivational states was effective in inducing the necessary conditions for Ž .

studying taste reactivity patterns: 1 cats of groups A and C ate more MFF than LFF Ž .

Žfood stimulus may have a different appreciation depending on variation in the internal. state. Secondly, it confirms the prediction that the cats of groups A and C were less hungry than the cats of group B.

4.3. BehaÕioural sequences

Ž . Analysis of the sequences of behavioural events of MFF and LFF revealed 1 that the motivational state did not affect the sequence of behavioural patterns as such — the

Ž .

MFF and LFF sequences for groups A, B and C were alike, 2 that distinct sequences of

Ž . Ž .

patterns appear to exist for food items which are consumed MFF and refused LFF ,

Ž . Ž .

and 3 that the same food item LFF appears to induce two kinds of sequences of patterns depending on whether it is eaten or refused.

The MFF sequence strongly resembles the post-meal behavioural sequences of

Ž . Ž .

Bradshaw and Cook 1996 who pooled the post-meal data of eight different palatable Ž

food items tested in 36 domestic cats 288 individual sequences with 15,095 behavioural events, i.e. 52.4 eventsrsequence, compared to 23 sequences with 1638 events, i.e. 71.2

Ž . .

eventsrsequence for the palatable item MFF in the present study . The fact that these sequences are alike underlines the notion of the ‘split half tests’ that the present sequences are based on sufficient data. Probably the fact that in all groups some cats ate

Ž LFF and some not — although with clearly different numbers of animals per group see

.

above — has resulted in the sequences being alike in the different groups. Subsequent splitting of the sequences between cats that did not and cats that did eat LFF regardless of the groups to which they belonged to, showed the differences with respect to MFF, and with respect to eating and refusing LFF.

Three differences between the sequences of cats which ate MFF and cats which refused LFF stand out. Firstly, the sequences start with different behavioural patterns:

Ž .

the ‘MFF consumption sequence’ started with lickrsniff feeding bowl or sniff floor whereas the ‘LFF refusal sequence’ started with lickrsniff food. Secondly, the ‘LFF refusal sequence’ contained the pattern lick nose, which was absent in the ‘MFF consumption sequence’. Lick nose has been found in previous observations to be

Ž . Ž .

associated with acute social stress Van den Bos, 1998a, see below . Thirdly, the ‘MFF consumption sequence’ showed a pronounced ‘oral and grooming behaviour’ part which was absent in the ‘LFF refusal sequence’. It should be noted that the frequency of grooming behaviour has been observed to be shortly increased after acute social stress ŽVan den Bos, 1998a,b . However, grooming behaviour appears to be of a different form. in these two situations. Under the present pleasant-food conditions predominantly

Ž .

face-washing occurs see also below , whereas under the social stressful conditions

Ž .

grooming of bodyrchest dominates unpublished data , leading eventually to skin Ž

damage hereof, when this develops into the overgrooming syndrome Bolka, 1984; .

Muller et al., 1995 .

That the ‘LFF consumption sequence’ appears to resemble the ‘MFF consumption sequence’ — both starting with lickrsniff feeding bowl and sniff floor, and displaying

Ž .

clearly grooming behaviour — suggests that the same stimulus LFF may induce two different kinds of sequences. Still it should be noted that even in case of the ‘LFF consumption sequence’ elements of refusal remained such as the presence of the patterns

Ž .

4.4. BehaÕioural patterns

The analysis of behavioural patterns between groups reinforces the impression obtained from the analysis of the sequences of behavioural events: a double dissociation of behavioural patterns between food items which are eaten and refused.

The behavioural patterns lickrsniff food and lick nose are displayed when cats are presented LFF under less hungry conditions in groups A and C, and disappear when cats

Ž .

eat LFF under the hungry conditions in group B. They are not or hardly associated with MFF and NF in any of the groups. Presumably, the licking or sniffing at the food shows the cat’s hesitation to eat the LFF. This is also illustrated by the fact that lickrsniff food makes out a high percentage of the time period before eating LFF. The frequency of lick nose has been observed to be shortly increased after a social stressful

Ž .

event aggression; Van den Bos, 1998a . The occurrence in the present context therefore could be caused by frustration due to the fact that the cats expected food which could be consumed and found out that it was not eatablerpalatable, i.e. lick nose as an expression of acute stress. However, it has been shown that in such acute stress conditions cats also Žtend to show other ‘acute stress’ behavioural patterns: grooming most notably groom. Ž

. Ž

chestrbody , shake head and scratching Van den Bos, 1998a; Van den Bos and Coerse, .

unpublished data . Inspection of the LFF data showed this not to occur. Unless it would

Ž .

be due to the type or intensity of stressors used which needs further study , alternatively therefore lick nose could be a direct expression of the dislike of the food item. Thus, it would appear that lickrsniff food and lick nose may be labelled as aversive taste reactivity patterns under the present conditions.

Ž .

Bradshaw and Cook 1996 observed the behaviour of cats before and after eating Žeight food items and found sniff object, sniff floor, groom face, groom chest, groom. body, and lip lick to be selectively shown in the post-meal phase. This would suggest that all these patterns could potentially be hedonic taste reactiÕity patterns. However, inspection of the data in the present study shows that only three behavioural patterns clearly show a consistent pattern with respect to general features of the food item Žexternal: MFF and LFF and the internal states of the cats more or less hungry in the. Ž . different groups and may therefore be marked as hedonic taste reactiÕity patterns under the present conditions: lickrsniff feeding bowl, lip lick and groom face.

In general, lickrsniff feeding bowl is shown more often after MFF than after LFF. This is also true in group B where more cats ate of LFF than in groups A and C. Furthermore this pattern is also more often shown after MFF than after NF-MFF, even in group A where cats had just finished eating their normal amount of food. Moreover

Ž .

this pattern tended to be shown more strongly in group B the more hungry cats than in

Ž .

group C the less hungry cats .

Lip lick is a behavioural pattern that always appears to be shown in response to contact with a food item as it is shown after presentation of all four food items. Still, as

Ž .

Groom face is also a behavioural pattern which is nearly always shown after contacting a food item as indicated by the fact that it is nearly always present after presentation of the four food items — except in group C for LFF. In the less hungry cats of groups A and C groom face was more often shown after MFF than LFF whereas such a difference did not exist in the hungry cats of group B. Furthermore, in group A groom face was also more often shown after MFF compared to after NF-MFF.

The differences in the occurrence of lip lick and groom face in relation to MFF and LFF and hunger levels of cats clearly cannot be reduced to differences in the amount of stickiness of MFF and LFF to the peri-oral area of cats. However, their occurrence per se in relation to food items could. For, most food items used in this study — MFF, LFF and NF — were wet foods. Currently, we are exploring whether this is the case by analysing post-meal behaviour of dry food items.

Ž

Groom chestrgroom body shown only less after NF-MFF compared to MFF in

. Ž

group A and more after NF-MFF compared to MFF in group B , lick paw shown only

. Ž

more after NF-LFF compared to LFF in group C , sniff floor shown for instance less after NF-MFF compared to after MFF and after NF-LFF compared to after LFF in both

. Ž

group B and C and sniff object shown only more after MFF compared to after .

NF-MFF in group B showed no consistent pattern with respect to food items and internal states.

Ž

It should be noted that after eating MFF grooming behaviour in general groom face, .

groom chest and lick paw is increased in group A compared to group B. This could be due to the fact that the cats of group A had already eaten their normal food which would have made them more satiated after eating MFF than the cats of group B which could not have been satiated after the small amount of MFF that they had eaten. Accordingly, the response of the cats in group A could have been stronger, or alternatively they may have reached the end-point of the sequence earlier — and therefore could devote more time to grooming behaviour — as it had been already activated after eating their normal food.

4.5. Taste reactiÕity patterns and palatability

Despite the differences in techniques by which the patterns were studied in rats Žforced intra-oral infusion; Grill and Berridge, 1985; Grill and Norgren, 1978; Berridge,

. Ž .

1996 and cats free-eating behaviour; present study the hedonic taste reactivity patterns of these different species show certain similarities. In both rats and cats, hedonic

Ž . Ž .

patterns include oral behaviour, i.c. lateral tongue protrusion rats and lip licking Žcats . Furthermore, rats show prolonged lapping at targets Berridge, 1996, p. 5 , which. Ž .

Ž .

is most often their paw Grill and Norgren, 1978 , which may be comparable to licking the feeding bowl in cats. In contrast to cats, groom face is seen in the aversive taste reactivity patterns in rats. In general, there is no similarity between the aversive taste reactivity patterns between cats and rats. Rats show behavioural patterns such as gapes, head shakes, facerpaw wipes, forelimb flails, paw shakes and rearingrlocomotion ŽBerridge, 1996; Grill and Berridge, 1985; Grill and Norgren, 1978 . These differences.

Ž may be due to either the techniques used, or to species-specific differences see

Ž .

.

humans, chimpanzees, Old world monkeys and rats, pp. 5–6 . Whatever the similarities and differences in the expression of hedonic and aversive taste reactivity patterns, it may be hypothesized that the underlying neural control is similar in different species.

Ž

As shown and discussed by Grill and Berridge Berridge, 1991, 1996; Berridge and . Grill, 1983; Berridge and Pecina, 1995; Breslin et al., 1992; Grill and Berridge, 1985 ,

˜

hedonic and aversive taste reactivity patterns can be separately affected by manipula-tions suggesting different underlying neural networks. These separate dimensions of positive and negative palatability may be projected onto a two-dimensional space toŽ

obtain a two-dimensional model of palatability processing see also Fraser and Duncan, .

1998 . Perceived palatability or ‘liking’ may be the summation then of these different Ž

processes resulting in a single value on a single continuum cf. as in humans; Cabanac, .

1971 . We are currently exploring the possibility whether it is possible to arrive at a composite palatability score using the frequencies and durations of lick nose, lickrsniff food, lickrsniff feeding bowl, lip lick and groom face.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the cat owners for allowing them to study their cats. Furthermore, they thank two anonymous referees for valuable suggestions.

References

Bartoshuk, L.M., Harned, M.A., Parks, L.H., 1971. Taste of water in the cat: effects on sucrose preference. Science 171, 699–701.

Ž .

Beauchamp, G.K., Maller, O., Rogers, J.G., 1977. Flavor preferences in cats Felis catus and Panthera sp. . J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 91, 1118–1127.

Berridge, K.C., 1991. Modulation of taste affect by hunger, caloric satiety and sensory-specific satiety in the rat. Appetite 16, 103–120.

Ž .

Berridge, K.C., 1996. Food reward: brain substrates of wanting and liking. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 20 1 , 1–25.

Berridge, K.C., Grill, H.J., 1983. Alternating ingestive and aversive consummatory responses suggest a

Ž .

two-dimensional analysis of palatability in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 97 4 , 563–573.

Berridge, K.C., Pecina, S., 1995. Benzodiazepines, appetite and taste palatability. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 19˜

Ž .1 , 121–131.

Berridge, K.C., Robinson, T.E., 1998. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning or incentive salience? Brain Res. Rev. 28, 309–369.

Ž .

Bolka, D.L., 1984. Normal, abnormal and misdirected behavior of cats. Vet. Rec. 5 4 , 272–279. Bradshaw, J.W.S., 1992. The Behaviour of the Domestic Cat. C.A.B. International, Wallingford.

Bradshaw, J.W.S., Cook, S.E., 1996. Patterns of pet cat behaviour at feeding occasions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 47, 61–74.

Bradshaw, J.W.S., Goodwin, D., Legrand-Defretin, V., Nott, H.M.R., 1996. Food selection by the domestic´

cat, an obligate carnivore. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 114A, 205–209.

Breslin, P.A., Spector, A.C., Grill, H.J., 1992. A quantitative comparison of taste reactivity behaviors to sucrose before and after lithium chloride pairings: a unidimensional account of palatability. Behav.

Ž .

Neurosci. 106 5 , 820–836.

Cabanac, M., 1971. Physiological role of pleasure. Science 173, 1103–1107.

Ž .

Cabanac, M., 1992. Pleasure: the common currency. J. Theor. Biol. 155, 173–200.

Cabanac, M., Lafrance, L., 1990. Postingestive alliesthesia: the rats tells the same story. Physiol. Behav. 47

Ž .3 , 539–543.

Cabanac, M., Lafrance, L., 1991. Facial consummatory reponses in rats support the ponderostat hypothesis.

Ž .

Physiol. Behav. 50 1 , 179–183.

Cabanac, M., Lafrance, L., 1992. Ingestiveraversive response of rats to sweet stimuli. Influence of glucose,

Ž .

oil, and casein hydrozalate gastric loads. Physiol. Behav. 51 1 , 139–143.

Dickinson, A., Balleine, B., 1994. Motivational control of goal-directed action. Animal learning and Behaviour

Ž .

22 1 , 1–8.

Ferguson, G.A., 1981. Statistical Analysis in Psychology and Education. 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, Auckland. Fraser, D., Duncan, I.J.H., 1998. ‘Pleasures’, ‘pains’ and ‘animal welfare’: toward a natural history of affect.

Anim. Welfare 7, 383–396.

Grill, H.J., Berridge, K.C., 1985. Taste reactivity as measure of the neural control of palatability. In: Sprague,

Ž .

J.M., Epstein, A.N. Eds. , Prog. Psychobiol. Physiol. Psychol.. Academic Press, Orlando, FL, pp. 1–65. Grill, H.J., Norgren, R., 1978. The taste reactivity test: I. Mimetic responses to gustatory stimuli in

neurologically normal rats. Brain Res. 143, 263–279.

Heyes, C., Dickinson, A., 1990. The intentionality of animal action. Mind and Language 5, 87–104. Liu, D., Dorio, J., Tannenbaum, B., Caldji, C., Francis, D., Freedman, A., Sharma, S., Pearson, D., Plotsky,

P.M., Meaney, M.J., 1997. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic–pitui-tary–adrenal responses to stress. Science 277, 1659–1662.

Mason, G., Cooper, J., Garner, J., 1997. Models of motivational decision-making and how they affect the experimental assessment of motivational priorities. In: Forbes, J.M., Lawrence, T.L.J., Rodway, R.G.,

Ž .

Varley, M.A. Eds. , Animal Choices, BSAS Occasional Publication No. 20. British Society of Animal Science, Edinburgh, pp. 9–17.

Muller, G.H., Kirk, R.W., Scott, D.W., 1995. Small Animal Dermatology. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. Spruijt, B.M., Van den Bos, R., Pijlman, F.T.A., 2000. A concept of welfare based on how the brain evaluates

Ž

its own activity: anticipatory behaviour as an indicator for this activity. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., under

.

revision .

Turner, D.C., Feaver, J., Mendl, M., Bateson, P., 1986. Variation in domestic cat behaviour towards humans: a paternal effect. Anim. Behav. 34, 1890–1901.

Ž

UK Cat Behaviour Working Group, 1995. An Ethogram for Behavioural Studies of the Domestic Cat Felis

.

silÕestris catus L. . Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, Potters Bar, UK.

Van den Bos, R., 1997. Reflections on the organisation of mind, brain and behaviour. In: Dol, M.,

Ž .

Kasanmoentalib, S., Lijmbach, S., Rivas, E., Van den Bos, R. Eds. , Animal Consciousness and Animal Ethics; Perspectives from the Netherlands. Animals in Philosophy and Science vol. 1 Van Gorcum, Assen, pp. 144–166.

Ž .

Van den Bos, R., 1998a. Post-conflict stress-response in confined group-living cats Felis silÕestris catus . Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 59, 323–330.

Ž .

Van den Bos, R., 1998b. The function of allogrooming in domestic cats Felis silÕestris catus : a study in a

Ž .

group of cats living in confinement. J. Ethol. 16 2 , 1–13.

Van den Bos, R., 2000. General organizational principles of the brain as key to the study of

Ž .

animal consciousness. Psyche An Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Consciousness 6 5 , http:rrpsyche.cs.monash.edu.aurv6rpsyche-6-05.vandenbos.html, February.

Willemse, T., Mudde, M., Josephy, M., Spruijt, B.M., 1994. The effect of haloperidol and naloxone on excessive grooming behavior of cats. Eur. Neurospychopharmacol. 4, 39–45.