i

Harnessing Talent towards an Inclusive

Malaysia

An Assessment of the National Policy on Science, Technology and

Innovation (NPSTI) in Enhancing Social Inclusion in Research and

Innovation

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia

And

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Jakarta Office

Project funded by Malaysian Funds-in-Trust for UNESCO

i

Harnessing Talent Towards

An Inclusive Malaysia

An Assessment of the National Policy on Science,

Technology and Innovation (NPSTI) in Enhancing Social

Inclusion in Research and Innovation

FINAL REPORT

United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural

Organization

(UNESCO) Jakarta

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Bangi, Malaysia

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES ··· vi

LIST OF TABLES ··· vi

ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ··· vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ··· xi

PREFACE ··· xiv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ··· xvi

PART I: INTRODUCTION AND MACRO OVERVIEW ··· 1

CHAPTER 1: OBJECTIVES AND METHODS OF STUDY, AND THE PROBLEMATIC OF SOCIAL INCLUSION ··· 1

1.1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.2 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY ... 2

1.3 METHODS ... 3

1.4 THE PROBLEMATIC OF SOCIAL INCLUSION... 3

CHAPTER 2: THE EMBEDDEDNESS OF SOCIAL INCLUSION IN MALAYSIAN PUBLIC POLICIES: EVOLUTION OF AN IDEA ··· 5

2.1 INTRODUCTION ... 5

2.2 THE FIRST PERIOD 1957-1970 ... 5

2.3 THE SECOND PERIOD 1971-1990 ... 6

2.4 THE THIRD PERIOD 1991-2010 ... 6

2.5 THE FOURTH PERIOD, 2011-2020 ... 7

CHAPTER 3: HIGHLIGHTS OF CONTEMPORARY MALAYSIAN POLICY DOCUMENTS: NEM, GTP, 10MPLAN AND 11MPLAN WITH REGARD TO SOCIAL INCLUSION ··· 7

3.1 INTRODUCTION ... 7

3.2 NEW ECONOMIC MODEL (NEM) ... 8

3.3 TENTH MALAYSIA PLAN (10MP) ... 8

3.4 ELEVENTH MALAYSIA PLAN (11MP) ... 9

3.5 CONCLUSION ... 11

PART 2: THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION (NPSTI) & ITS PROGRAMMES: AN EVALUATION OF METHODOLOGY AND INSTRUMENTS··· 12

CHAPTER 4: THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION (NPSTI) 2013-2020 ··· 12

4.1 INTRODUCTION ... 12

4.2 THE NEED FOR STI POLICY ... 12

iii 4.4 THE FRAMEWORK FOR THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY

AND INNOVATION (NPSTI) ... 14

4.5 STRATEGIC THRUSTS ... 15

4.6 CONCLUSION ... 19

CHAPTER 5: A CRITICAL DISCUSSION ON METHODOLOGY AND INSTRUMENTS: ROBUSTNESS AND MATCHINGS BETWEEN POLICY DOCUMENTS AND INSTRUMENTS ··· 20

5.1 INTRODUCTION ... 20

5.2 PRE-ANALYSIS PHASE ... 20

5.3 EQUIFRAME ANALYSIS OF THE NPSTI ... 22

5.4 NPSTI: SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 24

5.5 EXTENSION OF THE EQUIFRAME ANALYSIS: INCORPORATING THE EXTENDED NARRATIVE ... 25

5.6 THE USE OF EQUIPP IN THE CONTEXT OF THE NPSTI ... 25

5.7 HARMONISING THE NPSTI WITH THE UNESCO POLICY LAB INCLUSIVE POLICY DESIGN FRAMEWORK FOR MALAYSIA ... 26

5.8 CONCLUSION ... 29

PART 3: PROGRAMMES UNDER NPSTI – ASSESSMENT OF NPSTI IN ENHANCING SOCIAL INCLUSION IN RESEARCH AND INNOVATION··· 30

CHAPTER 6: OVERVIEW OF SELECTED PROGRAMMES UNDER NPSTI STRATEGIC THRUST 2: DEVELOPING, HARNESSING AND INTENSIFYING TALENT ··· 30

6.0 INTRODUCTION ... 30

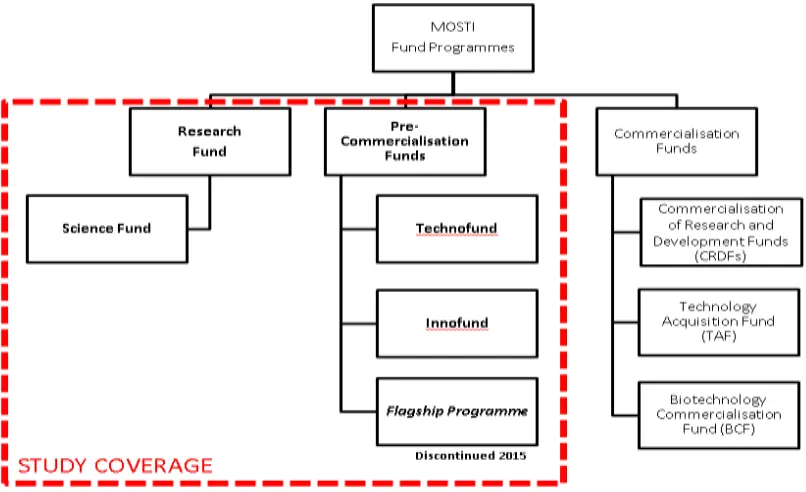

6.1 MOSTI’S RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALISATION FUNDS . 30 6.2 RESEARCH FUND (SCIENCE FUND) ... 31

6.3 PRE-COMMERCIALISATION FUND ... 31

6.4 COMMERCIALISATION FUND... 34

6.5 SUMMARY ... 34

CHAPTER 7: TECHNOFUND ··· 36

7.1 INTRODUCTION ... 36

7.2 RESEARCH PRIORITY AREAS ... 36

7.3 ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA... 37

7.4 EQUIPP ANALYSIS OF TECHNOFUND ... 38

7.5 CONCLUSION ... 41

CHAPTER 8: INNOFUND ··· 41

8.1 INTRODUCTION ... 41

8.2 RESEARCH PRIORITY AREAS ... 41

8.3 EQUIPP ANALYSIS OF INNOFUND ... 42

iv

CHAPTER 9: SCIENCE FUND ··· 45

9.1 INTRODUCTION ... 45

9.2 RESEARCH PRIORITY AREAS ... 46

9.3 EQUITY AND INCLUSION IN POLICY PROCESS (EquIPP) ANALYSIS ... 47

9.4 CONCLUSION ... 50

CHAPTER 10: FLAGSHIP PROGRAMME ··· 50

10.1 INTRODUCTION ... 50

10.2 THE NATIONAL SCIENCE AND RESEARCH COUNCIL ... 50

10.3 CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE FLAGSHIP PROGRAMME RESEARCH PRIORITY AREAS FROM A SOCIAL INCLUSION PERSPECTIVE ... 51

10.4 SELECTED EXAMPLES OF PROJECTS UNDER THE FLAGSHIP PROGRAMME 54 10.5 EQUITY AND INCLUSION IN POLICY PROCESSES (EquIPP) ANALYSIS OF THE FLAGSHIP PROGRAMME ... 55

10.6 CONCLUSION ... 57

CHAPTER 11: ASSESSMENT OF NPSTI IN ENHANCING SOCIAL INCLUSION IN RESEARCH AND INNOVATION ··· 58

11.0 INTRODUCTION ... 58

11.1 THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION (NPSTI) ... 58

11.2 INNOFUND, TECHNOFUND, SCIENCE FUND AND THE FLAGSHIP PROGRAMME ... 59

11.3 EQUITY AND INCLUSION IN POLICY PROCESSES (EquIPP) ANALYSIS OF THE VARIOUS PROGRAMMES BASED ON NINE THEMES ... 61

11.4 CONCLUSION ... 65

CHAPTER 12: ASSESSMENT OF DATA NEEDED FOR ENHANCING SOCIAL INCLUSION THROUGH THE NATIONAL POLICY FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION (NPSTI) ··· 66

12.1 INTRODUCTION ... 66

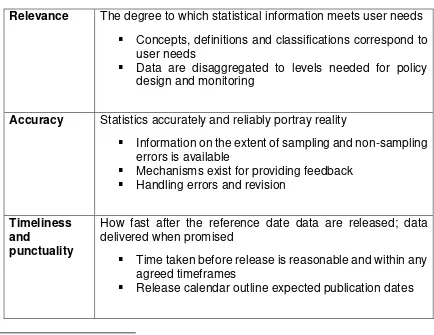

12.2 METHOD ... 67

12.3 DATA NEEDS FOR MONITORING SOCIAL INCLUSION IN THE STI SECTOR ... 68

12.4 CURRENT AVAILABILITY AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR PRODUCING DISAGGREGATED STI STATISTICS ... 71

12.5 RECOMMENDATIONS ... 73

PART 4: OVERALL CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS··· 74

CHAPTER 13: CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS: HARNESSING TALENT TOWARDS AN INCLUSIVE MALAYSIA ··· 74

13.1 INTRODUCTION ... 74

13.2 KEY FINDINGS ... 74

v

13.4 MOVING FORWARD ... 77

CHAPTER 14: ANJUNG FRAMEWORK: ANALYSIS OF NETWORKS AND JUXTAPOSITIONS OF SOCIAL INCLUSIVENESS UNDERPINNING NATIONAL GOVERNANCE ··· 77

14.1 INTRODUCTION ... 77

14.2 THE NEED FOR AN EXTENDED NARRATIVE ... 78

14.3 THE JUXTAPOSITION OF THE CONCEPT OF SOCIAL INCLUSION WITH SOCIOECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ... 78

14.4 ELEMENTS OF ANJUNG FRAMEWORK ... 79

14.5 APPLYING ANJUNG FRAMEWORK BEYOND THE NSTPI ... 81

REFERENCES ··· 82

APPENDIX 1: COMMERCIALISATION OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FUND (CRDF) ··· 85

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 - National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (2013-2020) ... 13

Figure 2 –Composite Elements of Social Inclusion in the UNESCO Policy Lab “Framework for Inclusive Policy Design: Malaysia” ... 27

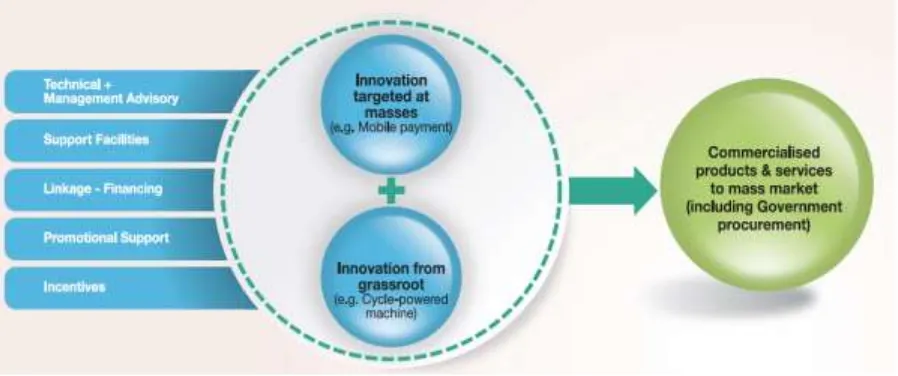

Figure 3: Framework for the 6th High Impact Programme (HIP6) of the SME Master Plan 2012-2020 Concerning Inclusive Innovation ... 29

Figure 4 - MOSTI Research, Development and Commercialisation Funds ... 30

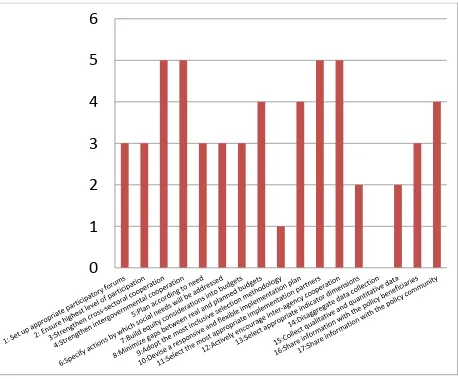

Figure 5 - Rating of EquiPP Key Actions in the Flagship Programme ... 55

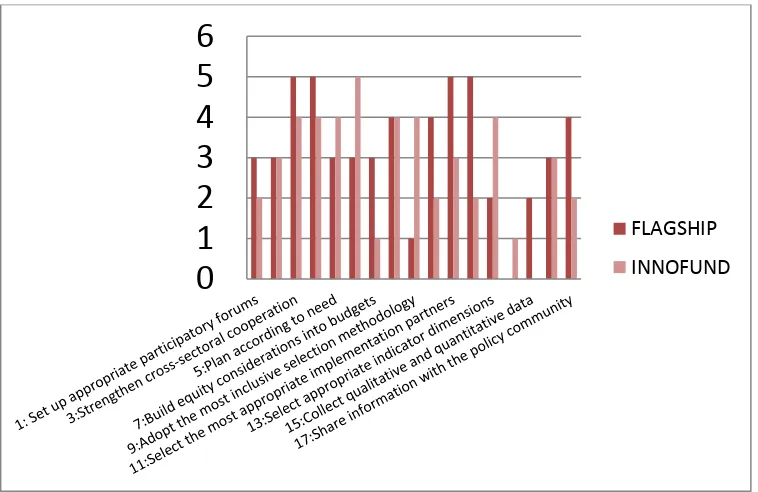

Figure 6 - Outcome of Selected MOSTI Grants Using EquIPP Anaysis ... 61

Figure 7 - Malaysia: Preliminary Review of Data Availability for 229 SDG Indicators by Source Agency ... 71

Figure 8 - ANJUNG Framework ... 80

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 - Benefits to the Rakyat (as envisaged in the New Economic Model) ... 8Table 2 - Core Concepts, Associated Language in the NPSTI and the Number of Times a Core Concept was Addressed ... 22

Table 3 - MOSTI’s Types of Research and Commercialisation Funds ... 34

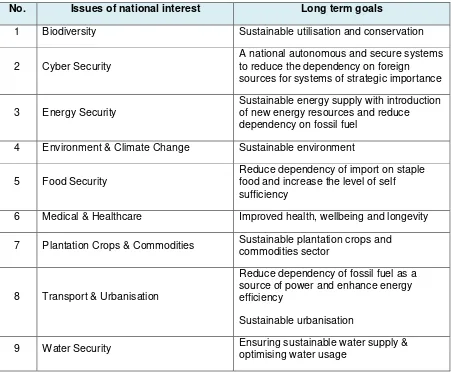

Table 4 - National Interests and Specific Long Term Goals of Research Priority Areas ... 52

Table 5 - Specific Priority Areas of Research ... 52

vii

ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS

10MP Tenth Malaysia Plan

11MP Eleventh Malaysia Plan

ABI Agro-Biotechnology Institute Malaysia

AIM Malaysia Innovation Agency

AIN Anugerah Inovasi Negara (National Innovation Award)

APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

B40 Bottom 40

BCF Biotechnology Commercialisation Fund

CCs Core Concepts

CIF Community InnoFund

CRDF Commercialisation of Research & Development Fund

DOSM Department of Statistics Malaysia

EIF Enterprise InnoFund

EPPs Entry Points Projects

EPR End of Project Report

EPU Economic Planning Unit

EquIPP Equity and Inclusion in Policy Processes

ETP Economic Transformation Programme

EWGs Expert Working Groups

FOR Fields of Research

FTA Free Trade Agreement

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GERD Gross Expenditure on Research & Development

viii GSIAC Global Science and Innovation Advisory Council

GTP Government Transformation Programme

HIP High Impact Programmes

ICT Information and Communication Technology

IHLs Institutions of Higher Learning

IKMAS

IP

Institute of Malaysian and International Studies

Intellectual Property

IPL Inclusive Policy Lab

JKD Jawatankuasa Kelulusan Dana (Funds Approval Committee)

JPK Jawatankuasa Pemantauan Khas (Special Monitoring Committee)

LGBTI Lesbian. Gay, Bisexual, Trans and/or Intersexual

KPWKM Ministry of Women, Family and Community Affairs

MAPEN Majlis Perundingan Negara (National Consultative Council)

MASTIC Malaysian Science and Technology Information Centre

MIGHT Malaysia Industry-Government High Technology Group

MOA Ministry of Agriculture

MOSTI Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation

MoU Memorandum of Understanding

MPI Multidimensional Poverty Index

MSI MOSTI Social Innovation Fund

MTDC Malaysia Technology Development Corporation

MyIPO Intellectual Property Corporation of Malaysia

MyNDS Malaysian National Development Strategy

MYR Malaysian Ringgit

NAM Non-Aligned Movement

NEM New Economic Model

NEP New Economic Policy

NGO Non-Governmental Organisations

NIC National Innovation Council

ix NIP National Integrity Plan

NKEAs National Key Economic Areas

NKRAs National Key Result Areas

NOD National Oceanographic Directorate

NPSTI National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation

NSRC National Science Research Council

OBOR One Belt One Road

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

OIC Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

PMO Prime Minister’s Office

PMTs Project Monitoring Teams

POC Proof of Concept

PRIs Public Research Institutes

R&D Research and Development

R,D&C Research, Development and Commercialisation

RIs Research Institutions

RMCs Research Management Centres

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

SEO Socioeconomic Objectives

SMEs Small and Medium Enterprises

SPS Sanitary and Phyto-sanitary

SRIs Strategic Reform Initiatives

STI Science, Technology and Innovation

STP Science and Technology Policy

TAF Technology Acquisition Fund

TOR Terms of Reference

TVET Technical and Vocational Education and Training

UKM Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (National University of Malaysia)

UMT Universiti Malaysia Terengganu (University of Malaysia, Terengganu)

x UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation

VGs Vulnerable Groups

WHO World Health Organisation

WTO World Trade Organisation

xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NATIONAL WORKING GROUP – MALAYSIA

Emeritus Prof. Dato’ Dr. Abdul Rahman Embong (Team Leader), Principal Research Fellow, Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Prof Dr. Rahimah Abdul Aziz (Chief Researcher), Centre for Social, Development and Environment Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Prof Dr. Rashila Ramli, Director & Principal Research Fellow, Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Dr. Husyairi Bin Harunarashid, Coordinator of Research Unit, Department of Emergency Services, Hospital Tuanku Mukhriz, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Mdm Chan Hong Jin, Deputy Division Secretary, Planning Division RSE Unit, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI)

Associate Prof. Dr. Sity Daud, Chairperson, Centre for History, Politics and Strategic Studies, Faculty of

Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Dr. Andrew Kam Jia Yi, Fellow, Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Dr. Sharifah Syahirah Syed Sheikh, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Cognitive and Human Development Kolej Poly-Tech MARA

Encik Hariszuan Jabarudin (Research Team Secretariat), Junior Fellow, Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

We would like to acknowledge with thanks the following colleagues from Malaysia who have given their contribution to the study during different stages of the project implementation:

Dr. Lee Yok Fee, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Human Ecology, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Puan Mastura Mohd Zaki, Assistant Secretary, Planning Division RSE Unit, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI)

Puan Nur Fakhriyyah El-Emin Muhardi, Deputy Director, Education Planning and Research Division Ministry of Education Malaysia

xii INTERNATIONAL CONSORTIUM OF EXPERTS

Ms. Anita Sykes-Kelleher, UNESCO Policy Lab

Ms. Jessica Gardner, UNESCAP Pacific Operations Centre (EPOC), Bangkok

Mr. Mac Maclachlan, Director of the Centre for Global Health, Trinity College, University of Dublin

Mr. Hasheem Manan, Health Sciences Centre, University College Dublin

Ms. Tessy Huss, Centre for Global Health and School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin

UNESCO

Mr. Irakli Kodeli, Programme Specialist of Social and Human Sciences Sector, UNESCO Office Jakarta Cluster Office to Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Timor-Leste

Mr. John Crowley, Chief of Research, Policy and Foresight Section, Sector for Social and Human Sciences, UNESCO Paris

Ms. Sue Vize, Regional Adviser for Social and Human Sciences Asia-Pacific, Social and Human Sciences UNESCO Bangkok

We would also like to put on record our thanks to the following individuals and institutions in Malaysia and abroad that have contributed directly or indirectly to the successful conclusion of this study:

H.E. Hon. Dato’ Sri Rohani Abdul Karim, Minister of Women, Family and Community Development of Malaysia; President of the UNESCO Inter-Governmental Council (IGC) of the Management of Social Transformation (MOST) Programme

H.E. Dato’ Sri Dr. Noorul Ainur Mohd Nur, Secretary General, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI) Malaysia; Immediate Past Vice President of Asia-Pacific Region of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Council (IGC) of the Management of Social Transformations (MOST) Programme

Malaysia Fund-in-Trust (MFIT)

UNESCO Jakarta & Paris

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM)

Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS) UKM

xiii Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI), Malaysia

Malaysian Science and Technology Information Centre (MASTIC) Ministry of Education, Malaysia

Ministry of Human Resource, Malaysia

Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development, Malaysia National Commission for UNESCO Malaysia

Universiti Putra Malaysia

Faculty of Cognitive and Human Development, Kolej Poly-Tech MARA Department of Statistics Malaysia

Trinity College, University of Dublin University College Dublin

UNESCAP Bangkok

NGOs and Individuals from Malaysia and Timor Leste who had attended the National Workshop in June 2015 and the National Dialogue in March 2016

xiv

PREFACE

This Report is an outcome of the project entitled “Harnessing Talent Towards An Inclusive Malaysia: An assessment of the National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (NPSTI) in enhancing social inclusion in research and innovation”. The project was funded by UNESCO under the Malaysia Fund-in-Trust (MFIT) and conducted by the National Working Group of researchers, under the leadership of key researchers from the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS) Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) with the collaboration of an international consortium of experts provided by UNESCO.

The study was conducted for almost a year beginning July 2015 and ending in May 2016. The overall objective of this initiative was to strengthen national capacity in Malaysia to assess and reform social policy and regulatory frameworks toward increasing their inclusiveness and ensuring equal enjoyment of human rights by all, including the disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in the country. The specific objectives of the study were:

To identify aspects/attributes/elements of social inclusion in the National Policy on Science, Technology & Innovation 2013-2020 (NPSTI);

To assess the degree of inclusiveness in the areas of research and innovation in NPSTI; and To assess the quality of relevant data and identify gaps and issues to be addressed. The National Working Group chaired by IKMAS UKM benefitted tremendously from the contribution of various parties in the course of conducting this research. As a necessary prelude to the study, a Policy Initiation Workshop on the theme “Promoting Social Inclusion through Public Policy in Malaysia” was organised by UNESCO and IKMASin Putrajaya, Malaysia on 8-10 June 2015 during which experts from UNESCO Policy Lab and Trinity College Dublin presented their research instruments namely: The UNESCO Analytical Framework for Inclusive Policy Design: Malaysia, (b) Equity Framework (Equiframe), and (c) Equity and Inclusion in Policy Processes (EquIPP). These instruments were to be utilised in the social inclusion policy research to be undertaken in Malaysia.

After the take-off of the project from July 2015 onwards, several meetings and consultations were held by the National Working Group with officials of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation Malaysia (MOSTI) to obtain data and their input on NPSTI. At the same time, similar meetings and consultations were also held with the experts from the international consortium to gain greater familiarity with the research instruments as well as to gather their input on the findings of the research. Another meeting with senior officers of MOSTI was also held to share some key findings of the study and to obtain their input before they were presented at the National Dialogue.

Towards the end of the project, a one-day concluding workshop and National Dialogue attended by several experts from the international consortium as well as various stakeholders from Malaysia was held on 22 March 2016. This was the culminating event in the framework of the UNESCO-Malaysia initiative that brought together national stakeholders to assess and enhance social inclusion in public policies – in particular in the STI sector – through the application of cutting-edge social science policy tools and methodologies. The National Dialogue showcased the results of the study and its policy recommendations, as well as the analytical tools employed during the policy assessment to a wider audience of national stakeholders, international partners and experts. This Report benefits greatly from insights and inputs provided by the participants at the National Dialogue.

xv This Report presents a historical overview of social inclusion in the Malaysian development policies since independence to the present, before zeroing in on the NPSTI and its four grant programmes. It presents important findings with respect to the degree of inclusiveness of the NSPTI and its four programmes, as well as offers policy recommendations to strengthen social inclusion in the STI sector in Malaysia.

The Report also highlights another important contribution of this study, that is, the construction of a research framework called “Analysis of Networks and Juxtapositions of Social Inclusive Policies Underpinning National Governance” or ANJUNG. ANJUNG is a new methodology which has been developed based on the Malaysian case study. This framework can and should be used in conjunction with the UNESCO Analytical Framework as well as the EquiFrame and EquIPP in any future country studies on social inclusion in public policies.

It is hoped that this Report and its recommendations can spark off and generate informed discussions for policy reforms to enhance social inclusion not only in the STI sector, but in various national policies generally in line with the orientation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2030. It is also hoped that the new methodology – ANJUNG – can be used creatively as a supplementary framework in the relevant policy studies in future.

While the National Working Group acknowledges the contributions of various parties in the preparation and refinements of this Report, the latter are not responsible for the Report’s shortcomings. The shortcomings are the sole responsibility of the National Working Group which welcomes further comments and criticisms.

xvi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Malaysia has enjoyed one of the best economic growth records in Asia over the last five decades despite a multitude of challenges and economic shocks. Malaysia rose from the ranks of a low income economy in the 1970s to a high middle-income economy in the 1990s and remains so today. Nevertheless, with success come various challenges as there are gaps that need to be effectively addressed to incorporate especially those left out of mainstream development besides having to address the current challenging international economic situation along the way. In this regard, the study on promoting social inclusion through public policies in Malaysia is also in keeping with the UN Declaration of Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework in which of the 17 SDGs six goals pertain to social inclusion.

This study aims to address the problem of harnessing talent in various levels of society towards an inclusive Malaysia as part of the process of becoming a developed nation. Since not all talents are easily recognised, they need to be identified and nurtured regardless of geographical locations, social class positions, gender and ethnicity.

A key dimension to harness talent is to examine the National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (NPSTI) to assess in what way and to what extent it enhances social inclusion in research and innovation. Specifically the objectives of the study are: 1) to identify aspects/attributes/elements of social inclusion in the National Policy on Science, Technology & Innovation 2013-2020 (NPSTI), 2) to assess the degree of inclusiveness in the areas of research and innovation in NPSTI, and 3) to assess the quality of relevant data as well as identify gaps and issues to be addressed.

The study was conducted using the “Framework for Inclusive Policy Design: Malaysia” from the UNESCO Inclusive Policy Lab, as well as Equiframe and the EquIPP. To execute that, the study looked into the documents and conducted interviews with relevant resource persons. For purposes of this study in the Malaysian context, social inclusion is defined as a rakyat or people-centered approach that can be considered as a goal and a process. Inclusiveness takes into account the environment where everyone feels a sense of belonging and where everyone has access to develop one’s full potential or talent. Inclusiveness is a process, as in ensuring the participation of all, including the disadvantaged and the vulnerable groups, the different stakeholders are engaged. Strategies formulated will be based on consultations and participatory approach, which then will allow for more voices to be heard, leading towards making better decisions and good governance. Inclusiveness is also a goal, for at the end of the process, it is expected that there will be higher degree of prosperity, greater equity and solidarity, and a lesser degree of discontent among the citizens of Malaysia.

xvii At the completion of the study, the report highlighted the following eleven findings:

1. The NPSTI is not a social policy that tends to be specific both in target groups as well as its targets in correcting various forms of inequality and social exclusion that resulted in the core problem which the particular policy tries to address. Rather, it is a policy of social development, or more accurately, a policy of social transformation given the very ambitious targets to be completed in what arguably is a short few years before the year 2020.

2. The NPSTI as a policy document has a number of core concepts pertaining to social inclusion although it could be more explicit on its concerns on social inclusion including on vulnerable groups.

3. Drawing on the approach put forward by UNESCO in its Analytical Framework for Inclusive Policy Design, NPSTI is not taken here as a stand-alone document, but is looked at from a wider perspective and seen as an extension of the national planning documents and the policy framework they proposed.

4. A historical approach is necessary to understand the evolution of the idea of social inclusion as it has been a guiding principle for Malaysia since its independence in 1957.

5. The research instruments of EquiFrame, EquIPP and the ‘Framework for Inclusive Policy Design: Malaysia’ from the UNESCO Policy Lab - while to some extent could be generalised in order for NPTSI to be analysed – the instruments need to be used with care and with an understanding of the wider and deeper historical context of Malaysia.

6. The EquIPP was useful for the purpose of assessing the processes of social inclusion in policy making.

7. This study made use of the three instruments in various ways, and in the process, had developed its own broad approach by combining the various methods. This approach is called an “ANJUNG Framework: Analysis of Networks and Juxtapositions of Social Inclusiveness Underpinning National Governance”.

8. The assessment of the four grant programmes under NPSTI shows that they achieve a “moderate level” score in terms of social inclusion based on EquIPP instrument.

9. It is recommended that policy documents such as NPSTI make more explicit the concepts and concerns of social inclusion including the vulnerable groups, more so with Malaysia’s commitment to SDG goals.

10. The prioritization of the fields or areas of research can be reconsidered. As it is, only one area is categorised as social sciences and humanities, while the other areas are under science-related fields. To enhance social inclusion, the perspectives of social sciences and humanities are very crucial hence more attention should be given to it in terms of grants for research and innovation.

11. To ensure social inclusion, data is necessary. In this regard there is a crucial need for data disaggregation in particular by sex, age, geography, including rural-urban location, and ethnicity in keeping with the SDG framework.

This report is divided into four parts: Part 1: Introduction and Macro Overview

xviii contemporary Malaysian Policy Documents with regard to social inclusion. Part 1 basically situates the setting – contextual and historical – for the study.

Part 2: The National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (Npsti) & Its Programmes: An Evaluation of Methodology and Instruments

This part discusses the National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (NPSTI) together with a critical discussion of the methodology and instruments used in the research, especially with respect to its robustness and matchings between policy documents, instruments and study objectives.

Part 3: Programmes under NPSTI – Assessment of NPSTI in Enhancing Social Inclusion in Research and Innovation

Part 3 discusses the programmes under NPSTI with specific reports on the four programmes -TechnoFund, InnoFund, Science Fund and the Flagship Programme and an overall assessment of NPSTI and its programmes in enhancing social inclusion in research and innovation. It also contains an assessment of data needs for enhancing social inclusion through NPSTI.

Part 4: Overall Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

1

PART I: INTRODUCTION AND MACRO OVERVIEW

CHAPTER 1: OBJECTIVES AND METHODS OF STUDY, AND THE PROBLEMATIC OF

SOCIAL INCLUSION

1.1

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia has enjoyed one of the best economic growth records in Asia over the last five decades despite a multitude of challenges and economic shocks. The economy has achieved a stable real GDP growth of 6.2% per annum since 1970, successfully transforming from a predominantly agriculture-based economy in the 1970s, to manufacturing in the mid-1980s, and to modern services in the 1990s. Malaysia rose from the ranks of a low income economy in the 1970s to a high middle-income economy in the 1990s and remains so today. Malaysia’s national per capita income expanded more than twenty-five fold from US$402 (1970) to US$10,796 (2014) and is expected to surpass the US$15,000 threshold of a high-income economy by 2020 (Malaysia 2015: 3).

Nevertheless, with success come various challenges as there are gaps that need to be effectively addressed to incorporate especially those left out of mainstream development, besides having to address the current challenging international economic situation along the way. In this regard, the study on promoting social inclusion through public policies in Malaysia as proposed by UNESCO is extremely timely as Malaysia aspires to achieve a developed nation status by 2020 and beyond. This is made all the more necessary as in the recently launched 11th Malaysia Plan (2016-2020), enhancing

inclusiveness towards an equitable society is one of the sixth strategic thrusts (see Chapter 4). This is in keeping with the UN Declaration of Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework in which of the 17 SDGs, six goals pertain directly to social inclusion as shown below:

Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable

industrialization and foster innovation.

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions for all.

2 achievement of the 17 SDG goals and 169 targets by 2030 with “…quality, accessible, timely and reliable disaggregated data …to ensure that no one is left behind”.1

This study aims to address the problem of harnessing talent in various levels of society towards an inclusive Malaysia as part of the process of becoming a developed nation. Not all talents are easily recognised, what more developed. As such they need to be identified and nurtured regardless of geographical locations, social class positions, gender and ethnicity. A key dimension to harness talent is to examine the National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (NPSTI) to assess in what way and to what extent it enhances social inclusion in research and innovation (see Chapter 4).

However, the examination of the NPSTI needs to be located within the framework of an overarching national paradigm on social inclusion as well as examined within a historical perspective in order to have a holistic grasp and comprehensive view of social inclusion as the guiding principle of Malaysia’s national development. A single policy approach to the study of social inclusion will only give a partial view, which sometimes can be misleading. This is because the question of social inclusion – as will be shown below – is often embedded within the mesh of multifarious cross-cutting social inclusion policies that pervade across sectors, and which flow from the over-arching national paradigm that guides the nation building process since the country’s independence in 1957 and more so since the 1970s.

It is with this understanding that this Report consciously begins with an overview of social inclusion – or what can be regarded as attempts at social inclusion –in Malaysian public policies, to trace the evolution of the idea before we begin with the analysis of the NPSTI. It poignantly argues that the idea of social inclusion has been embedded in the Malaysian Constitution and development plans since the birth of the independent nation almost 60 years ago, i.e. well before it became an explicit mainstream policy concern in the 21st century both nationally and globally. It is the contention of this Report that

without the understanding of this historical context and the grasp of the embeddedness of social inclusion in public policies since Independence, we will not do justice to the study of social inclusion in Malaysian public policies today including the NPSTI, and will not be able to make appropriate recommendations to strengthen national capacity and to suggest reforms.

1.2

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The overall objective of this study is to strengthen national capacity in Malaysia to assess and reform social policy and regulatory frameworks toward increasing their inclusiveness and ensuring equal enjoyment of human rights by all, including the disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in the country.

Specifically the objectives of the study are:

1. To identify aspects/attributes/elements of social inclusion in the National Policy on Science, Technology & Innovation 2013-2020 (NPSTI);

2. To assess the degree of inclusiveness in the areas of research and innovation in NPSTI; and 3. To assess the quality of relevant data and identify gaps and issues to be addressed.

1United Nations.Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for

3

1.3

METHODS

Based on the outcome of the discussion between UNESCO, the international consortium and the National Working Group chaired by IKMAS UKM, the study was conducted by applying the following instruments to the selected policies: (a) UNESCO Analytical Framework for Inclusive Policy Design: Malaysia, (b) Equiframe, and (c) EquIPP. The three instruments employed in this work have been selected for their complementarity, in terms of level of application and approaches, and their specific focus on furthering inclusive social development through inclusive public policies and government programmes. To achieve its objectives, the study looked into the policy documents and conducted interviews with relevant resource persons.

1.3.1. Analytical Framework for Inclusive Policy Design: Malaysia. Produced by UNESCO, the tool was contextualised to national and sectoral needs by IKMAS and the members of the Malaysian National Working Group. The resulting product put forward quality- and process-related markers against which the inclusive character of the overall national strategic documents, especially the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (11MP), and the portfolio of NPSTI policies was weighed.

1.3.2. Equiframe. The instrument ‘EquiFrame” is intended to evaluate the degree of explicit commitment of an existing public policy to 21 Core Concepts of Human Rights (based on research evidence and UN Conventions) and inclusion of 12 Vulnerable Groups (for Malaysian context, additional vulnerable groups are included).

1.3.3. EquIPP. Equity and Inclusion in Policy Processes (EquIPP) is an approach which insists that the processes of government facilitate the translation of policy content into priority access for ‘vulnerable groups’ and adherence to core human rights principles. This is in recognition that by bridging gaps and encouraging exchanges between policy makers, service providers and service users, more effective service design and delivery will result, as well as being better tailored to meet the different needs of the different people in the community. Within the framework of this project, the tool was primary applied to NPSTI policy and programmes.

1.4

THE PROBLEMATIC OF SOCIAL INCLUSION

The Report maintains that while the explicit use of the concept of social inclusion in academic discourse and in public policies is very recent, the idea and practice of social inclusion in society as observed in various countries is not new. Various religions and civilisations throughout the ages have social inclusion embedded in their teachings and practices. In Islam, for example, there is the precept of the

zakat– the compulsory tithe – to be paid by the well-to-do, and distributed to the eight categories of people (asnaf) who meet the criteria – or what today can generally be described as the vulnerable socioeconomic groups. However, it is not just the question of giving that is emphasised as there is also the idea of empowering the people, or releasing their initiatives, capability and talent to enable them to stand on their own feet. Thus the injunction in Islam that “Allah will not change the fate of a people unless they themselves strive to change it” is very pertinent.

4 they live…” (Atkinson &Marlier 2010:1), while social inclusion is defined as “…the process by which societies combat poverty and social exclusion…” (ibid:1). The ultimate objective is to create an inclusive society, defined as “…a society for all in which every individual, each with rights and responsibilities, has an active role to play…” (UN 1995, chpt. 1, para 66).2 More specifically, an inclusive society is one

“…that rises above differences of race, gender, class, generation and geography to ensure equal opportunity regardless of origin, and one that subordinates military and economic power to civil authority…” (Atkinson & Marlier 2010: 3).

The United Nations through its various agencies has adopted the agenda of social inclusion since the late 1990s, an agenda that has since become a mainstream global policy concern especially since the launching in 2000 of the Millennium Developments Goals (MDGs) to be achieved by 2015. TheMDGs are the world's time-bound and quantified targets for addressing extreme poverty in its many dimensions – income poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter, and exclusion – while promoting gender equality, education, and environmental sustainability. However, critics have argued that there was a lack of analysis and justification behind the MDGs’ objectives, and the difficulty or lack of measurements for some goals, and that much of the aid from developed countries went to debt relief, natural disaster relief and military aid, rather than for development and capacity building. Some other criticisms also merit attention: These include the lack of consultations at its conception to build ownership that has led to the perception of a donor-centric agenda; inadequate incorporation of other important issues, such as environmental sustainability, productive employment and decent work, inequality; limited consideration of the enablers of development; and the failure to account for differences in initial conditions. As highlighted earlier, the Sustainable Development Goals (SGs) towards 2030 adopted by the UN in 2015 are supposed to have addressed these shortcomings, and take into account more directly the question of social inclusion.

UNESCO defines social inclusion as “a multi-dimensional process geared towards the creation of conditions and, if required, lowering of economic, social and cultural barriers for a full and active participation of every member of the society in all aspects of life. Such a process pays due attention to how and for whom terms and conditions are to be improved” (UNESCO Analytical Framework for Inclusive Policy Design, p. 6). While the above definition is used as a guide, for purposes of this study in the Malaysian context, social inclusion is defined as a rakyat or people-centered approach that can be considered as a goal and a process. Inclusiveness takes into account the environment where everyone feels a sense of belonging and where everyone has access to develop one’s full potential or talent.

Inclusiveness is a process, as in ensuring the participation of all, including the disadvantaged and the vulnerable groups, the different stakeholders are engaged. Strategies formulated will be based on consultations and participatory approach, which will then allow for more voices to be heard, leading towards making better decisions and good governance. Inclusiveness is also a goal, for at the end of the process, it is expected that there will be higher degree of prosperity, greater equity and solidarity, and a lesser degree of discontent among the citizens of Malaysia.

In conclusion, it should be stressed that social inclusion in public policies is a necessary precondition for nurturing and harnessing talent in every level of society. It seeks to overcome obstacles and ensure access to opportunities in order to realize one’s potentials irrespective of race, gender, geography, creed, age, etc.

2

.

See documents of the United Nations World Summit for Social Development held in Copenhagen in5

CHAPTER 2: THE EMBEDDEDNESS OF SOCIAL INCLUSION IN MALAYSIAN PUBLIC

POLICIES: EVOLUTION OF AN IDEA

2.1

INTRODUCTION

As indicated in the first chapter, while the discourse specifically on the concepts of social exclusion and social inclusion as well as stakeholder engagement is relatively new, more so in Malaysia, it does not mean that the awareness of the need for inclusion and the actual action to ensure inclusion has been absent in Malaysian society and in public policies. Similarly, the process of stakeholder participation in policy formulation is also not something new. Indeed the idea of social inclusion and stakeholder participation has been embedded within Malaysian policy documents ever since the birth of the Malaysian nation in 1957 until today. The formulation of the Federal Constitution by the Reid Commission in 1955 was preceded by a series of stakeholder consultations to get as much inputs as possible to be integrated into the founding document.

For analytical purposes, the discussion on academic awareness and policy commitment to social inclusion in Malaysia will have to be seen in four distinct historical phases – 1957 to 1970; 1971-1990; 1991-2010; and 2011 and 2020.

2.2

THE FIRST PERIOD 1957-1970

2.2.1 The first period 1957-1970: This was basically the immediate post-independence years during which the principal document guiding the country was the Federal Constitution. Articles 8, 10 and 12 of the Constitution expressly state Malaysia’s commitment to human rights – the fundamental principle of social inclusion. Article 8 of the Federal Constitution states that:

“(1) All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law; (2) Except as expressly authorised by this Constitution, there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent, gender or place of birth in any law relating to the acquisition, holding or disposition of property or the establishing or carrying on of any trade, business, profession, vocation or employment.”

Article 10 is on the freedom of speech and expression; the right to assemble peaceably and without arms; and the right to form associations. All these indicate the respect for basic human rights. Recognising the multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-religious diversity of the Malaysian society, and the specific socioeconomic challenges faced by the Malays and other Bumiputera groups, the Constitution stipulates certain guiding principles to ensure unity and inclusiveness. For example, on the question of religious diversity, Article 3 of the Constitution addresses it thus: that “(1) Islam is the religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practised in peace and harmony in any part of the Federation.”

6 Hashim 1972: 245). It is not meant to deprive the rights of other communities as the Article balances it by stating that the King would protect “…the legitimate interests of other communities…”

The enshrining of these principles in the Constitution constitutes the overarching paradigm and the necessary basis for the formulation of subsequent national plans and policies that take into account the interest of the people at large.

2.3

THE SECOND PERIOD 1971-1990

2.3.1 The second period 1971-1990: This was the period of the implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP), a long term perspective plan covering 1971 to 1990. While the ideas of the NEP were already in gestation since the early 1960s, the NEP as a plan was triggered by the May 13, 1969 race riots, which led to a brief suspension of Parliament for one and half years. It also led to some soul-searching and serious stakeholder consultations on how to rebuild a united cohesive nation. This led to the promulgation of the Rukunegara or the National Ideology, the formulation of which was the efforts of the National Consultative Council (Majlis Perundingan Negara or MAPEN), headed by Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein with a view to create racial harmony and national unity. It became the guiding principles of the New Economic Policy (1971-1990) which was launched in 1971, with the aim to forge unity among the various ethnic groups in Malaysia.

The Preamble in Rukunegara which was announced on Merdeka Day on 31 August 1970 articulated Malaysia’s aspirations to achieve greater unity among her peoples; maintaining a democratic way of life; creating a just society where the prosperity of the country can be enjoyed together in a fair and equitable manner; ensuring a liberal approach to her rich and diverse cultural traditions; and building a progressive society which shall be oriented to modern science and technology.

As can be seen above, the idea of social inclusion and an inclusive society is already embedded within the preamble of Rukunegara, and was expressed in policy formulation in the New Economic Policy (1971-19990). The two-pronged objectives of the NEP were: (a) to eradicate poverty irrespective of race; and (b) to restructure society to remove the identification of race with economic function. It should be noted here that the understanding of social exclusion during that period was related to poverty, and hence the focus was on the eradication of this scourge.

2.4

THE THIRD PERIOD 1991-2010

2.4.1 The third period 1991-2010: This was the period covered by two long term perspective plans, (a) The National Development Policy, 1991-2000, which focused on ensuring the balanced development of major sectors of the economy and regions, as well as reducing socioeconomic inequalities across communities; and (b) The National Vision Policy, 2001-2010, focused on building a resilient and competitive nation. The planning during this period was predicated upon the big visionary ideas articulated in Vision 2020, a national vision which was launched in February 1991.

7 democratic, moral, tolerant, progressive, caring, fair and equal in accordance with the goals of Vision 2020.”

To raise the awareness and commitment further, in 2004, the National Integrity Plan (NIP) was also launched together with the setting up of the Malaysian Institute of Integrity. Integrity is a necessary prerequisite to combat corruption and abuse of power, to ensure transparency and accountability, and commitment to people’s well-being and unity among all ethnic groups.

All these policy reforms were important social innovations, a significant milestone in enhancing social inclusion in public policies despite the fact that the term ‘social inclusion’ was not yet extensively used.

2.5

THE FOURTH PERIOD, 2011-2020

2.5.1 The fourth period, 2011-2020. It is during this period that the concept of social inclusion has been made explicit in development policies. This is in keeping with the global agenda initiated by the United Nations through UNESCO and others to promote social inclusion in public policies and strengthen regulatory frameworks for that purpose.

It is worthy to note that the National Transformation Policy, 2011-2020, maintains the people-centric focus through the New Economic Model, which sets the goal of becoming a high-income economy with advanced technology that is both inclusive and sustainable. This transformation agenda is supported by the Economic Transformation Programme, which focuses on the 12 economic areas that are most critical to the nation’s continued growth, and the Government Transformation Programme, which focuses on transforming areas of public service that are of greatest concern to the rakyat. As the policies and plans for the contemporary period are more varied and cross-cutting, a more detailed treatment of this period and the commitment to social inclusion is necessary. This will be addressed in the following Chapter 3.

CHAPTER 3: HIGHLIGHTS OF CONTEMPORARY MALAYSIAN POLICY DOCUMENTS:

NEM, GTP, 10MPLAN AND 11MPLAN WITH REGARD TO SOCIAL INCLUSION

3.1

INTRODUCTION

As Malaysia entered the 21st century, the government and policy makers, the business community,

academics and civil society (the quadruple helix) have realised that Malaysia has reached a defining moment in her history, a crossroads in its development path to achieve a developed nation status by 2020. To go beyond the crossroads, the government launched the New Economic Model (NEM) on 30 March 2010 whose key ideas are high income, sustainability and inclusiveness, and to shift the ethnic-based affirmative action to one that is need-ethnic-based. This is supposed to be implemented through four key pillars, viz. (a) The 1Malaysia, People First, Performance Now concept to unite all Malaysians to face the challenges ahead; (b) The Government Transformation Programme (GTP) to strengthen public services in the National Key Result Areas (NKRAs); (c) The Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) which will propel Malaysia to be an advanced nation with inclusiveness and sustainability in line with the goals set forth in Vision 2020; and (d) The 10th Malaysia Plan 2011-2015, and later the 11th Malaysia

8

3.2

NEW ECONOMIC MODEL (NEM)

As stated in government policy documents, the NEM strives for broader goals than just boosting growth and attracting private investments. The NEM takes a holistic approach, focusing also on the human dimension of development, recognising that while we have substantially reduced poverty, a hefty 40% of Malaysian households still earn less than RM1500 per month. Income disparity must still be actively addressed. Measures are needed to narrow the economic differences prevalent in Sabah and Sarawak as well as in the rural areas of the Peninsula. Hence, the concept of the Bottom 40 (B40) emerged as a key policy initiative for social inclusion. As stated in the Foreword to the 10th Malaysia

Plan by the Prime Minister, “…The Government is committed to uplift the livelihoods of the bottom 40% of households, irrespective of ethnicity, background or location, through income and capacity building programmes, strengthening the social safety net and addressing the needs of the disadvantaged groups...”

The New Economic Model envisages the following benefits for the rakyat that will be achieved through the plan.

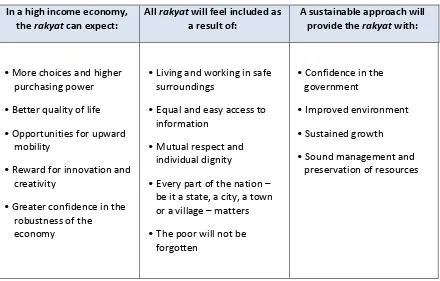

Table 1 - Benefits to the Rakyat (as envisaged in the New Economic Model)

In a high income economy, the rakyat can expect:

All rakyat will feel included as a result of:

stipulates clearly the concept of rakyat-centric development, and distinguishes between what it calls ‘the capital economy’ and ‘the people economy’. In Chapter 1 of the 10MP, among the 10 Big Ideas, two are specific on social inclusion. These are: “Ensuring equality of opportunities and safeguarding the vulnerable” and “Concentrated growth, inclusive development”.

9 o Raising the Income Generation Potential of Bottom 40% Households

o Elevating the Quality of Life of Rural Households

o Enhancing the Economic Participation of Urban Households

o Assisting Children in Bottom 40% Households to Boost Their Education and Skills Attainment

o Strengthening Social Safety Net to Reduce Vulnerability of Disadvantaged Groups

o Providing Housing Assistance Programmes to Deserving Poor Households in Rural and Urban Areas

o Providing Income Support, Subsidies and Improved Access to Healthcare o Addressing the Needs of Special Target Groups with Integrated Programmes

o Strengthening the Capabilities of Bumiputera in Sabah and Sarawak and Orang Asli

Communities in Peninsular Malaysia

o Providing Financial Assistance to Chinese New Villages’ Residents to Upgrade Their Homes and Fund Their Business Activities

o

Enhancing Access to Basic Amenities and Infrastructure for Estate Workers to Improve Their Living Standards3.4

ELEVENTH MALAYSIA PLAN (11MP)

The Eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016-2020 is even more explicit in its policy concerns with social inclusion, namely the rakyat-centric approach to development. In Chapter 1 “Anchoring Growth on People”, it states that the Eleventh Malaysia Plan reaffirms the Government’s commitment to a vision of growth that is anchored on the prosperity and wellbeing of its rakyat. The Eleventh Malaysia Plan is premised on a progressive and united Bangsa Malaysia that shares a common commitment towards building a better Malaysia for all Malaysians.

As stated in the Eleventh Malaysia Plan, “…The development of the Eleventh Plan was guided by the Malaysian National Development Strategy (MyNDS), which focuses on rapidly delivering high impact on both the capital and people economies at low cost to the government. The capital economy is about Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, big businesses, large investment projects, and financial markets, while the people economy is concerned with what matters most to the people, which includes jobs, small businesses, the cost of living, family wellbeing, and social inclusion...” It stresses further that the Eleventh Malaysia Plan is a strategic plan that paves the way for Malaysia to deliver a future that the rakyat desires and deserves. It represents the Government’s commitment to fulfilling the aspirations of the people.

10 For example, in “Strategic thrust 1: Enhancing inclusiveness towards an equitable society”, it states that inclusivity has always been a key principle in Malaysia’s national socioeconomic development agenda, and a fundamental goal of the New Economic Model. This commitment is to enable all citizens – regardless of gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic level, and geographic location – to participate in and benefit from the country’s prosperity. It is anchored on a belief that inclusive growth is not only key to individual and societal wellbeing, but also critical for sustaining longer periods of solid economic growth. It further states that to enable everyone to participate in and enjoy the benefits of economic growth, the Government is committed to ensuring equitable opportunities for all segments of society, in particular the B40 households.

One of the strategic game changers is the “Uplifting of B40 households towards a middle-class society” (p. 12) The Eleventh Malaysia Plan says that today, there are 2.7 million B40 households with a mean monthly household income of RM2,537. As Malaysia continues to grow, the B40 households should not miss out on the opportunities that come with national prosperity. Allowing the B40 households to remain in their current socioeconomic status will create social costs for all Malaysians, as it reduces the number of skilled workers needed to grow national output, perpetuates urban inequality, and limits the growth potential of rural and suburban areas. As a result, the Eleventh Malaysia Plan asserts that all B40 households regardless of ethnicity will be given greater focus, especially the urban and rural poor, low-income households, as well as the vulnerable and aspirational households.

In order to realise the aspiration stated above, the Government will implement strategies to raise the income and wealth ownership of the B40 households, address the increasing cost of living, and strengthen delivery mechanisms for supporting B40 households. The Government will also introduce the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) to ensure that vulnerability and quality of life is measured in addition to income.

Another important game changer is “Enabling industry-led Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)”. Arguing that TVET is important for Malaysia, the Eleventh Malaysia Plan envisages 60% of the 1.5 million jobs that will be created will require TVET-related skills. Meeting this demand will require Malaysia to increase its annual intake gradually from 164,000 in 2013 to 225,000 in 2020. Yet, the challenge is not merely about numbers. The Plan takes note that industry feedback consistently reveals that there is disconnect between the knowledge, skills, and attitudes these graduates possess, and what is required in the workplace.

An effective and efficient TVET sector is one where supply matches demand, and there are robust quality control mechanisms which ensure that all public and private institutions meet quality standards; that industry and TVET providers collaborate across the entire value chain from student recruitment, through to curriculum design, delivery, and job placement; and that students are well-informed of the opportunities that TVET can offer and view TVET as an attractive pathway. Students also have access to a variety of innovative, industry-led programmes that better prepares them for the workplace. From the perspective of assessment of social inclusion in a particular policy or programme, TVET is an example of a policy which reflects the cross-sectoral involvement of many stakeholders. To get a comprehensive view of the policy, one cannot merely examine TVET under the Ministry of Education alone, but should examine the other related policy documents and other ministries/agencies that deal with the same issues. In fact, TVET is provided by seven different ministries:

o Ministry of Education

11 o Ministry of Defense

o Ministry of Works.

3.5

CONCLUSION

12

PART 2: THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND

INNOVATION (NPSTI) & ITS PROGRAMMES: AN EVALUATION OF

METHODOLOGY AND INSTRUMENTS

CHAPTER 4: THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION

(NPSTI) 2013-2020

4.1

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia has an overarching goal of becoming a developed nation that is inclusive and sustainable by the year 2020 with a society that is stable, peaceful, cohesive and resilient. A central challenge towards the attainment of the nation’s Vision 2020 goal is that of establishing a scientifically advanced and progressive society, one that is innovative and forward-looking, which is not only a consumer of technology but also a contributor to the scientific and technological civilisation of the future. This challenge underscores the important role of science, technology and innovation (STI), particularly in facing the rapid changes of a globalised and competitive world. Realising that STI are central to propel the socioeconomic landscape of the nation, it is imperative that STI be strengthened and mainstreamed into all sectors and at all levels of national development agenda. STI should be pervasive and inclusive in order to touch the lives of every Malaysian irrespective of race, creed, class, gender and geography.

The commitment of Malaysia in harnessing, utilising and advancing Science and Technology is reflected with the formulation and implementation of the First National Science and Technology Policy (1986-1989), The Industrial Technology Development: A National Action Plan (1990-2001), and The Second National Science and Technology Policy and Plan of Action (2002 – 2010). The various initiatives and programmes that were implemented under these policies, including the enhancement of national capabilities and capacities of Research and Development (R&D), the forging of partnerships between public funded research organisations and industries, enhancement of commercialisation through National Innovation Model, and development of new knowledge-based industries, have accelerated the advancement of country’s STI. Moving forward to the next stage and addressing some of the gaps, the National Innovation Model was launched in 2007 to take a balance approach between technology– driven and market-driven innovation, recommending a paradigm shift especially in the modus operandi of the various universities, industries and research institutes that undertook research and development (R&D).

Moving ahead in an era fraught with uncertainties and intense global competition, business as usual approach will not work. Therefore, in 2009, the Government, through The New Economic Model (NEM), adopted new and bold initiatives to ensure the achievement of Vision 2020. NEM laid out a new course for Malaysia to realise its aspiration of becoming a high-income nation with an economy that is inclusive and sustainable. The broad directions of the NEM have been incorporated into the Tenth Malaysia Plan (2011-2015) and implemented through the Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) incorporating, among others, the 12 National Key Economic Areas and 6 Strategic Reform Initiatives (SRIs) (see Chapter 3).

4.2

THE NEED FOR STI POLICY

13 the science, technology and innovation (STI) capabilities towards establishing Malaysia’s competitiveness and leadership regionally and globally. In order to succeed, Malaysia has to innovate based on strong scientific fundamentals. In this regard, fostering strong and resilient partnerships, connectivity and inter-dependence amongst all sectors of the society is essential. The changing landscape has become a challenge for Malaysia, not only to the government but also to industries, universities, research institutes, and the whole STI ecosystem. Efforts to review the previous policy have led to the framing of the current National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation (NPSTI) (2013-2020). NPSTI adoption and integration of holistic and inclusive approach is timely to respond to these challenges.

4.3

THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION (2013-2020)

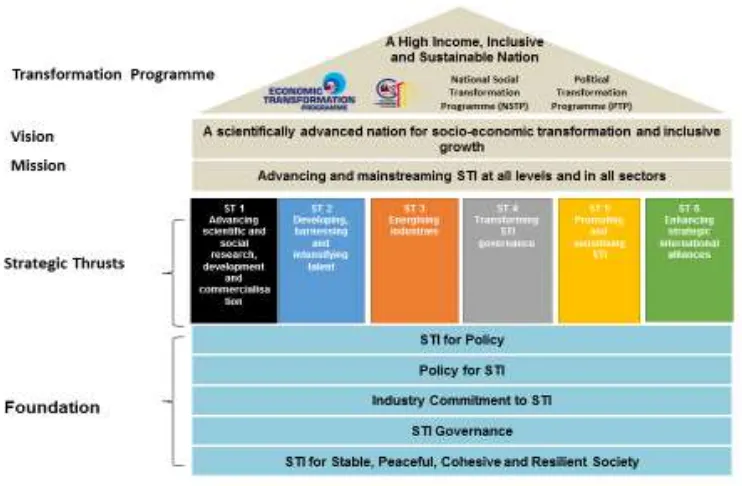

The new NPSTI describes an agenda to advance Malaysia towards a more competitive and competent nation built upon strong STI foundations. The policy is formulated based on the nation’s achievements, challenges and lessons learnt. It charts new directions to guide the implementation of STI in creating a scientifically advanced nation for socioeconomic transformation and inclusive growth (Figure 1). The NPSTI is grounded on the following five fundamental foundations:

i. STI for Policy; ii. Policy for STI;

iii. Industry Commitment to STI; iv. STI Governance; and

v. STI for a stable, peaceful, prosperous, cohesive and resilient society.

14

4.4 THE FRAMEWORK FOR THE NATIONAL POLICY ON SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND

INNOVATION (NPSTI)

The NPSTI framework focuses on the pivotal role of STI in the context of Government Transformation framework, knowledge-based economy, and other changing “rules of the game” to steer Malaysia towards a high income nation that is sustainable and inclusive. The thrusts and its strategies described in this policy are the driving forces of STI that will guide Malaysia’s initiatives in achieving its vision.

Vision

A scientifically advanced nation for socioeconomic transformation and inclusive growth.

Mission

Advancing and mainstreaming STI at all levels and in all sectors. Strategic Thrusts

i. Advancing scientific and social research, development and commercialisation; ii. Developing, harnessing and intensifying talent;

iii. Energising industries;

iv. Transforming STI governance; v. Promoting and sensitising STI; and

vi. Enhancing strategic international alliances.

The above strategic thrusts are not mutually exclusive. They are, instead, inextricably linked. The success of one strategic thrust has ramifications on the others. Similarly, the failure of any of these strategic thrusts will have debilitating effects on the rest. With the solid development of these strategic thrusts Malaysia will emerge as a healthier, prosperous, and greener country based on STI foundations imbued with strong ethical and humanistic values embedded within a resilient and inclusive society. Key Policy Foundations

The NPSTI endorses that STI is a powerful socioeconomic instrument that will enhance the generation of knowledge, creation of wealth and societal well-being. This will be achieved through adoption of a holistic approach incorporating the following policy foundations:

1) STI for Policy

STI for policy is the most important foundation. It ensures that STI are mainstreamed into, embraced and implemented by all ministries, agencies, private sectors and all relevant stakeholders. NPSTI embodies the needs of harnessing STI in the context of socioeconomic transformation programme. It is based on the New Economic Model (NEM) and the Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) with the 6 strategic reform initiatives (SRIs), 12 national key economics areas (NKEAs) and 131 entry points projects (EPPs).

2) Policy for STI

15

3) Industry commitment to STI

Private sectors, including SMEs, are at the forefront of translating ideas into new or improved products, processes, services or solutions. They should be dynamic and robust to act as the driver of economic growth. However, the limitations of some of Malaysia’s larger private sectors and SMEs in terms of technology and innovation are well known. To address this issue, we have to do things differently. NPSTI will help to strengthen STI capabilities for industry to play a more active role as envisioned in the government’s Economic Transformation Programme (ETP). The industry will be re-energised and reinvigorated through various incentives and measures. Linkages and collaborations among the public and private sector, research organisations, and industry-specific research institutes must be further forged.

4) STI governance

A sound institutional and regulatory framework is central to an effective and well-functioning STI system. Since matters pertaining to STI transcend all ministries and involve the participation of various stakeholders such as the civil service, industry, academia and the community, issues pertaining to coordination, collaboration and harmonisation assume great importance. NPSTI reinvigorates the nation’s existing STI framework in order to enhance the execution of policies besides providing mechanisms to ensure commitment by all parties towards the development of STI in the country. It will help to overhaul our STI tracking system to ensure that it informs policy makers on the performance of the STI programmes. In addition, the innovative potential of the public service, including the policy makers and implementers should be harnessed to ensure a more efficient and effective delivery system. In line with the demands required to become a high-income economy, the public delivery system should be further improved. The principles of sound public sector governance should be adopted.

5) STI for a stable, peaceful, prosperous, cohesive and resilient society

An environment which encourages creativity, risk taking, and rewards market-driven ideas will inspire interest in S&T careers and is vital for STI to flourish. The community must be engaged so that they will continue to be supportive, and values and places a high premium on STI. Many players including the government, universities, science-oriented communities, professionals and journalists need to support and promote the enculturation of STI. While STI plays an important role in humankind, the risk and ethical questions as well as issues of public interest (safety, health, security and the environment) will always be of concern. Therefore, the NPSTI also ensures that the ethical and humanity issues are taken into consideration and be understood through the promotion of integration of knowledge across disciplines and sectors so as to foster a balanced approach in economic and social development as well as in environmental protection.