Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:31

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Estimates of Indonesian population numbers: first

impressions from the 2010 census

Terence H. Hull

To cite this article: Terence H. Hull (2010) Estimates of Indonesian population numbers: first impressions from the 2010 census, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 46:3, 371-375, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2010.522505

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2010.522505

Published online: 23 Nov 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 291

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/10/030371-5 © 2010 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2010.522505

ESTIMATES OF INDONESIAN POPULATION NUMBERS:

FIRST IMPRESSIONS FROM THE 2010 CENSUS

Terence H. Hull

Australian National University

This note provides a critical perspective on the preliminary results of the 2010 population census, which were announced by President Yudhoyono on 16 August 2010. It explores the concepts of population used and the adjustments made to in-crease the accuracy of census estimates. The assumptions underlying various ofi-cial population projections in the last decade produced estimates for mid-2010 that were substantially below the igure of over 237 million persons counted in May. The note argues that, far from relecting a ‘population explosion’, this is due to the achievement in the 2010 census of greatly increased coverage of people residing in Indonesia on the census date.

Oficials in charge of family planning, population registration, health, educa -tion and economic planning often argue that they need a single set of popula-tion forecasts to carry out their duties. For this reason the Indonesian government requires BPS (Statistics Indonesia) and Bappenas (the central planning agency) to

produce a unique projection of the population, using the latest census igures as

the base population, and the most accurate recent estimates of fertility, mortality and migration for the assumptions about population dynamics. For professional demographers in BPS, this poses a problem. The decennial census provides

infor-mation that allows the deinition of the population in terms of actual or legal residents and in terms of Indonesian citizens or all residents. In addition the dei -nition may include or exclude special groups like prisoners, members of the

mili-tary and seafarers. For each of these deinitions there is a big difference between

the reported, recorded and actual numbers. While a census may produce a single number of recorded actual residents on the census date (15 May in the case of the 2010 census), an understanding of that number requires consideration of how much it is subject to an under-count, and how it is adjusted to produce the esti-mate of the true resident population.

PROCEDURES FOR THE 2010 POPULATION COUNT

This is nowhere more starkly shown than in the release of the ‘oficial’ census

number as part of the president’s Independence Day speech to parliament on 16 August 2010. BPS provided a number that took account of both the house-hold listing undertaken before the census enumeration and the full househouse-hold

count continuing up to early August. The listing was done by teams in the irst

372 Terence H. Hull

couple of weeks of May, and recorded on the census’s ‘L1’ form. The preliminary results released in previous decennial censuses were largely based on the listing

stage of census ieldwork. In 2010 ieldworkers discovered at a very early stage of

enumeration that the household listing was not reliable. The L1 summary forms contained space for a comparison with the long questionnaire (the ‘C1’ form). The so-called full count was completed in most provinces in the period 12–28

May, though dificulties in some urban and isolated areas led to extension of the

census period through June and occasionally into July and August. If, during the

main data collection, the ield supervisors found an error in the L1 listing, they

had an opportunity to make a correction. Also, as the C1 forms were scanned and

processed, the analysts in the central ofice had the opportunity to verify some

problematic regional population estimates and revise the L1 count with the most up-to-date numbers. The corrections or completions made late in the process all asked about people’s residence as at the census date of 15 May. The persistence of BPS staff ensured that as many people as possible would be enumerated.

THE 16 AUGUST SPEECH POPULATION NUMBERS

But the national population number given to the president covered more than the L1 households. It included the listings from special census blocks (such as large hotels, hospitals, prisons and military facilities), smaller institutions in ordi-nary census blocks and the special counts of the homeless and shipboard popula-tions, recorded on census form ‘L2’. Efforts were made to ensure that nobody was skipped or counted twice.

Inevitably, the population numbers released on 16 August as Hasil Sensus Pen-duduk 2010: Data Agregat per Provinsi [2010 Population Census Results:

Aggre-gate Data per Province] immediately became the ‘oficial’ count of the country’s

population. The number announced to the world was 237,556,363 (http://www. bps.go.id/65tahun/SP2010_agregat_data_perProvinsi.pdf). The reality is that we cannot regard this as the true population for 15 May, even within a couple of per-centage points, since BPS is still processing the full count and checking popula-tion numbers through a post-enumerapopula-tion survey in every province. Indonesia’s preliminary population count is in a state of continuing update and correction.

CONCEPTS OF POPULATION

It is impossible to produce a totally accurate count because of the huge number and high mobility of Indonesia’s people. Moreover, the preliminary estimate of residents is only one of many ‘populations’ that people think about when con-sidering the constituents of a nation. Should we count citizens only, or should resident non-citizens be included? If all residents within the boundaries of the

nation are to be included, is it eficient, or even possible, to check every place

where people may have set up living quarters, or are there some mountain peaks, remote islands or urban pocket-slums that interviewers cannot be expected to visit? Finally, how should the census deal with large institutions – the army, pris-ons, mental hospitals and the like – which are not ‘households’ in the common use of the word, and which often place security barriers between interviewers and the inhabitants. The answer to each of these questions gives rise to a different concept

of population, and in political discourse Indonesians talk about these concepts for different purposes and with different understandings. BPS has a strong sense of mission to be as inclusive as possible, and to devote all resources necessary to reach every resident of the archipelago. However, as any economist can tell

us, there is a point of diminishing returns at which the cost of inding additional people is greater than the beneits of a more accurate population count.

THE 2010 POPULATION ESTIMATE AND THE PROJECTIONS

What can we learn from the 2010 population estimate? Probably most observers will want to know how it compares with that of the 2000 census and with the projections made to the middle of 2010. If the number is above the projections it will be said that family planning failed in Indonesia, while if it is below the projec-tions, then various politicians will claim credit for having overcome a population explosion. Both interpretations would be naive in the extreme.

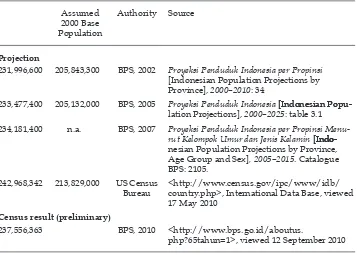

In table 1 we can see that the projections of resident population to mid-year

2010 (speciically to 30 June at midnight) differed according to the assumed base

population numbers and the assumptions about trends in fertility, mortality and migration. Over the past decade, emerging data on fertility decline were fed into

oficial population projections and there was growing conidence that fertility

would be lower than previously projected. Mortality assumptions changed more slowly, and at the national level there was an assumption of no net migration.

Thus changes in oficial projections over the decade were largely relections of

beliefs about fertility levels.

TABLE 1 Projections to Mid-Year 2010 and Census Figures as at 15 May 2010

Assumed 2000 Base Population

Authority Source

Projection

231,996,600 205,843,300 BPS, 2002 Proyeksi Penduduk Indonesia per Propinsi [Indonesian Population Projections by Province], 2000–2010: 34

233,477,400 205,132,000 BPS, 2005 Proyeksi Penduduk Indonesia [Indonesian Popu-[Indonesian Popu-lation Projections], 2000–2025: table 3.1 234,181,400 n.a. BPS, 2007 Proyeksi Penduduk Indonesia per Propinsi

Menu-rut Kelompok Umur dan Jenis Kelamin [Indo-[Indo- Indo-nesian Population Projections by Province, Age Group and Sex], 2005–2015. Catalogue BPS: 2105.

242,968,342 213,829,000 US Census Bureau

<http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/ country.php>, International Data Base, viewed 17 May 2010

Census result (preliminary)

237,556,363 BPS, 2010 <http://www.bps.go.id/aboutus.

php?65tahun=1>, viewed 12 September 2010

374 Terence H. Hull

Changes to assumptions can increase or decrease by millions the popula-tion projected to mid-2010. What is most interesting about these numbers is not

that they are different, but that the differences among the oficial Indonesian

projections are generally small. The projection of the US Census Bureau Inter-national Data Base is another matter: at 243 million, it is much higher than any Indonesian policy makers expected.

This difference is particularly important in gaining an understanding of the 2010 census results. The US Census Bureau assumed the 2000 base population to be 214 million, to adjust for what was known to have been a substantial census under-count. All other projections assumed the base population to be between 205 and 206 million.

THE 2000 CENSUS

The 2000 census failed to enumerate all Indonesians because between 1997 and 2001 the country suffered a string of political and economic disasters. The demise

of the New Order government came at the time of the Asian inancial crisis, and

national budgets were cast into disarray. Planning for the decennial population census had started in the middle of the 1990s, with a large number of ambitious innovations on the drawing board. As budget cuts proceeded, BPS leaders were forced to abandon much of what had been planned: post-enumeration surveys were carved back, travel budgets squeezed and many training and supervision

activities adjusted to it the new inancial realities. The most devastating blow came a few weeks before the start of ieldwork, when the government imposed

a reduction in interviewer wages. All in all, the entire episode inevitably

com-promised data quality. Coverage was also reduced when conlicts broke out in

a number of provinces. This prevented interviewers from making the necessary visits to households, and forced them to rely instead on estimates from local

gov-ernment oficials.

BPS was able to adjust for some but not all of the under-count that took place in 2000. The projections for that year had been 210 million, and the actual count of population was under 200 million. The adjustments for regions not covered brought the estimates up to about 205 million, and although it was known that there were also substantial under-counts of particular population groups — such as highly mobile young people, apartment dwellers and marginalised communi-ties — there were no data available to permit further adjustments to account for these people. The lack of a systematic post-enumeration survey robbed BPS of the

information it needed to make better estimates, and thus undermines conidence

in the assumed base population used in the BPS projections.

THE 2010 CENSUS

By comparison, the 2010 enumeration has been able to avoid many of these

dif-iculties. Government funds have been more generous and reliable, almost all dis -tricts have enjoyed social order and security, and the ambitious innovations for

training and ield supervision have improved interviewer performance.

The results announced on 16 August were higher than all the projections, other

than that of the US Census Bureau. This relects virtually universal coverage in

2010 – in contrast with the complex under-count of 2010 – and should be a cause for celebration. It is not evidence that the country has experienced a‘population explosion’ or a ‘baby boom’. Such terms are totally out of the question, given Indonesia’s remarkable success in bringing fertility down to replacement level, right on target, in 2010. It is a sign of the success of the census rather than the failure of social policies.

This is a truly remarkable achievement. But it is also a challenge for professional demographers in universities, research organisations and government policy centres. Lay observers will look at the projections, the estimates and the implied

growth rate, and will try to use these raw igures to assess government perfor

-mance. That would be a serious error. It will be necessary to reine, adjust, com -pare and assess all these numbers, and to turn the products of these assessments into stories understandable to politicians and the public. Unfortunately the record of census interpretation in recent decades has not been good. There has been a general failure to take account of falling fertility estimates and annual surveys

showing that contraceptive use has remained stable at around 60% of women of

reproductive age. As a result, the public debate has been infused with speculation about coming baby booms and population explosions. This is a serious example of how misguided much discussion of population numbers can become.

FINAL COMMENT

It is worth remembering that the 2010 population census is the most inclusive activity ever undertaken by the Indonesian government. All other government

data collections focus on speciic groups – the poor, the urban, the young, women, the elderly, or electors. These are groups that have some speciic characteristic

worthy of concentrated attention. But the characteristic of the census population is simply residence. All people living in Indonesia on 15 May 2010 were to be included. In contrast to the experience of previous censuses, it seems that this was largely achieved. All researchers interested in Indonesia’s economy and society

will anxiously await the release of inal census data over the next two years.