CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SMART CITY ENVIRONMENTS

M. Angelidoua, E. Karachalioua T. Angelidoua, E. Stylianidisa

a School of Spatial Planning and Development, Faculty of Engineering, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece mangel@auth.gr; ekaracha@auth.gr; angelidoutatiana@gmail.com; sstyl@auth.gr

Commission II

KEY WORDS: Smart city, strategy, application, urban development, touristic development, cultural heritage management

ABSTRACT:

This paper investigates how the historical and cultural heritage of cities is and can be underpinned by means of smart city tools, solutions and applications. Smart cities stand for a conceptual technology-and-innovation driven urban development model. By becoming ‘smart’, cities seek to achieve prosperity, effectiveness and competitiveness on multiple socio-economic levels. Although cultural heritage is one of the many issues addressed by existing smart city strategies, and despite the documented bilateral benefits, our research about the positioning of urban cultural heritage within three smart city strategies (Barcelona, Amsterdam, and London) reveals fragmented approaches. Our findings suggest that the objective of cultural heritage promotion is not substantially addressed in the investigated smart city strategies. Nevertheless, we observe that cultural heritage management can be incorporated in several different strategic areas of the smart city, reflecting different lines of thinking and serving an array of goals, depending on the case. We conclude that although potential applications and approaches abound, cultural heritage currently stands for a mostly unexploited asset, presenting multiple integration opportunities within smart city contexts. We prompt for further research into bridging the two disciplines and exploiting a variety of use cases with the purpose of enriching the current knowledge base at the intersection of cultural heritage and smart cities.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, increasing urbanisation along with a rapid population growth in major modern cities have been impacting the quality of citizens’ life at technical, social, economic and organisational level. Smart city initiatives along with Information and Communication Technology (ICT) integration aim to advance traditional networks while providing efficient services and public benefits urban dwellers.

While we observe that the smart city literature variably sets forth the objectives of cultural advancement, touristic development and heritage preservation, research into the specificities of the relationship between urban ‘smartness’ and cultural heritage remains limited. In addition, there is no complete review of smart city applications used in the domain of cultural heritage worldwide. Addressing this research gap, in this paper we aim to examine how the historical and cultural heritage of cities is and can be underpinned by means of smart city tools, solutions and applications.

2. CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SMART CITY ENVIRONMENTS

2.1 Literature review and state of play

According to UNESCO’s universally accepted definition, the term “Cultural Heritage” refers to several main categories of heritage (UNESCO, 2016): (i) Tangible cultural heritage: movable cultural heritage (paintings, sculptures, coins, manuscripts), immovable cultural heritage (monuments, archaeological sites, and so on), underwater cultural heritage (shipwrecks, underwater ruins and cities), (ii) Intangible cultural heritage: oral traditions, performing arts, rituals and

(iii) Natural heritage: natural sites with cultural aspects such as cultural landscapes, physical, biological or geological formations. The majority of the above types of cultural heritage can be found in the complex of a city and in many cases they are called to coexist and be integrated in the contemporary structures of modern cities and their technological advances. Moreover, cultural heritage represents a domain where sustainability of interventions, people gratification, promotion and preservation of spaces and artworks have to be considered in total and at the same time (Chianese et al, 2015).

Smart cities, on the other hand, are urban settlements that make a conscious effort to capitalise on the new ICT landscape in a strategic way, seeking to achieve prosperity, effectiveness and competitiveness on multiple socio-economic levels (Angelidou, 2014). The concept of the smart city emerged recently and is constantly being transformed by contemporary technological and economic trends and ongoing discussions. One of the distinctive characteristics of smart cities is the central role of technology as a means for accumulating, organising and making vast amounts of information accessible to an increasing number of people (Angelidou, 2016). This results to a technologically-enabled ecosystem which yields improvements on the city’s functions, enhancing environmental sustainability and rendering the city ‘smart’ (Allwinkle and Cruickshank, 2011; Angelidou, 2015; Caragliu et al., 2009; Tranos and Gertner, 2012).

local tangible and intangible assets can be highlighted and promoted through those strategies, enabling cities to capitalise on their competitive advantage to become more attractive to people, tourists and businesses (Giffinger et al., 2007). In this sense, one-size-fits-all solutions are to be avoided in the context of smart cities. Rather, customised approaches should be adopted, depending on the specific situation.

Vattano (2014) asserts that the integration of a city’s historical elements into its modern reality is a significant factor towards the advancement of its urban intelligence. The specific benefits of including cultural heritage in a smart city initiative derive from big data management and augmented reality (AR). Big data management allow to store and administer great amounts of data, beneficial for the preservation of cultural heritage, and the sustainable monitoring of its life cycle conservation. Meanwhile, optimising technological use in cultural heritage management leads to cost reduction in terms of maintenance. Further, smart city initiatives could advance cultural heritage ontologies with AR characteristics allowing both citizens and visitors to readily access their historical value.

Despite the abovementioned benefits, and although cultural heritage is one of the many issues addressed by existing smart city strategies, this takes place in an abstract and fragmented way. For example, according to Bélissent (2010), the vision of what kind of smart city is desired could be inspired from different ideas: cities might envision becoming a business hub, a tourist and heritage destination, or a manufacturing or retail centre. Hollands (2008) observes that ICTs lie at the core of the smart city idea, as they undergird networked infrastructures to improve economic and political efficiency and enable social, cultural and urban development. Amato et al. (2012) describe a platform, tool and possible functionalities for incorporating smart city technologies in the cultural heritage domain. Chianese et al. (2015) propose a smart cultural heritage architecture and platform for enhancing user experience in cultural heritage sites. Similarly, Jara et al. (2015) put forth an Internet of Things (IoT) function architecture for smart towns. Garau (2014) describes a platform that is fed through bottom-up input to aggregate, inform, and suggest cultural heritage points of interest and paths in the Region of Sardinia, Italy. Overall, we observe that although occasionally important work has been done, especially in the field of user experience and process architecture, the available literature on the overall strategic relationship between cultural heritage and smart cities remains limited and abstract.

The situation is not very different in practice. In analysing 61 applications from 33 smart cities in different parts of the world, Zubizarreta et al. (2015), found that although an abundance of smart city applications is used in local smart city strategies, most of them function as standalone tools, rather than collectively contributing to an integrated vision towards sustainable local development. In terms of existing smart city strategies, one of the major objectives of London’s smart city strategy is to be a world-class city in the fields of commerce and culture (Greater London Authority, 2013); in the smart city strategy of Barcelona, technology is seen –among others- as an enabler for universal access to culture and education (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2014); with respect to the smart city applications in the Amsterdam Smart city initiative, Lee and Gong Hancock (2012) found that smart city applications in the category ‘tourism/culture/sports/leisure’ count for the 26% of the smart city services portfolio. The City of Genova, Italy has created the Smart Museum and Park arena platform,

aiming to simultaneously advance the city’s natural and cultural heritage and safety and security in urban spaces (Schaffers, 2011). For the city of Gold Coast (popular tourist city in Queensland, Australia) which received an IBM Smarter Cities Challenge Grant, Bajracharya et al. (2014) propose that the preservation and promotion of cultural and natural amenities should be a priority of the smart city strategy. None of the previous approaches, however, is backed by clearly defined objectives, processes and tools to enhance cultural heritage through the smart city route.

Altogether we see that cultural heritage is inarguably a priority domain of urban development policy, including smart city development. Nevertheless, there is lack of an in-depth definition of the strategic relationship between urban ‘smartness’ and cultural heritage, as well as lack of clarity with respect to the included objectives, processes, and results.

2.2 A research into how cultural heritage objectives have been incorporated in existing smart city ventures initiative

2.2.1 Research design

Inspired by the above situation, in this paper we examine how the historical and cultural heritage of cities has been incorporated in existing smart city strategies so far. The methodology we use is ‘cross-case analysis’ (Yin, 2003), whereby selected information is collected across selected cases and then analysed comparatively in order to identify underlying trends, patterns and relationships, allowing for the extraction of theoretical propositions (Eisenhardt, 1989).

In this paper, we present three European smart city initiatives which have variably addressed the issue of cultural heritage. These include the strategies of Barcelona, Amsterdam and London. The factors that drove our selection are (i) the existence of a ‘cultural heritage’ component within the strategy (be it subtle or pronounced), (ii) the maturity of the initiatives, which is a precondition for being able to acquire the necessary data and (iii) the availability of information through academic and government publications (academic journal and conference papers, theses and research reports, policy documents).

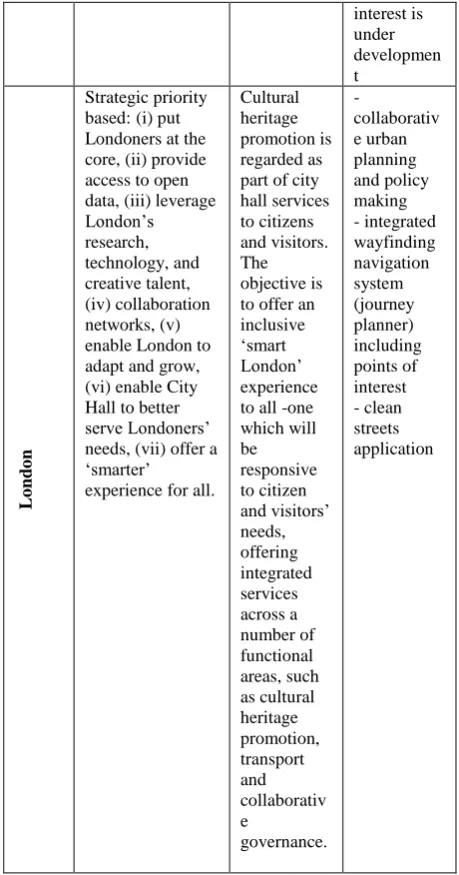

For each case (Barcelona, Amsterdam, and London) we collected information about:

- the scope and structure of the smart city initiative - the specific objectives of cultural heritage promotion

within the smart city initiative and

- the particular smart city applications related to cultural heritage which are deployed in the context of the smart city strategy under examination

The collected data were arranged in a tabular display, which features the above information per each case (Table 1). On the basis of this display, the collected information was scanned vertically and horizontally to uncover underlying patterns.

2.2.2 Field research

Barcelona’s Smart City strategy (Spain) is structured upon three pillars: ‘international promotion’, ‘international collaboration’ and ‘local projects’. The strategy has a global outlook, seeking to forge an open environment for the collaboration among government, industry, academia and citizens (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2013; Angelidou, 2016; Bakici et al., 2012; Barcelona Smart City official website, 2017; Mora and Bolici, 2015). Smart city applications can be found in the areas of (i) smart mobility, (ii) public and social services, (iii) environment, (iv) companies and business, (v) research and innovation, (vi) communications, (vii) infrastructures, (viii) tourism, (ix) citizen cooperation and (x) international projects. Each one of the previous includes a number of smart city programmes and projects, such as the ‘City Operation System’, the ‘Smart City Campus’, ‘Smart Lighting’, ‘Smart Urban Mobility’ and so on -the number of local projects is more than 100. In this strategy, among others, technology is seen as an enabler of culture, education and healthcare (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2014).

Amsterdam smart city (the Netherlands) is a partnership among businesses, authorities, research institutions, and the people of Amsterdam to reduce CO2 emissions and improve the environmental record of the city (Amsterdam Smart City official website, 2017; Angelidou, 2016; Lee and Gong Hancock, 2012; Mora and Bolici, 2017). In this strategy, the city is seen as an open platform for experimentation. Smart city products and services are user centric, altogether contributing to the development of more liveable urban environments. More particularly, the majority of the included projects are targeted towards informing citizens, entrepreneurs and the public sector about their energy consumption and educating them about how to manage it more prudently. Currently the program comprises an array of projects that present innovative ideas and new business models across Amsterdam’s neighbourhoods. These projects fall within six thematic areas: (i) infrastructure and technology, (ii) energy, water and waste, (iii) mobility, (iv) circular city, (v) governance and education, (vi) citizens and living. The projects are initially tested on a small scale and the ones that prove to be effective are subsequently extended to larger areas. In Amsterdam’s strategy, cultural heritage, manifested through the city’s canals, monuments and traditional residential areas, is addressed as a component of urban liveability and quality of life (Amsterdam Smart City official website, 2017).

Smart London (United Kingdom), is a smart city initiative that began in 2013 with the formation of the Smart London Board and the release of the Smart London Plan (Anthopoulos, 2017; Goh, 2015; Greater London Authority, 2013, 2016; Smart London official website, 2017). The Smart London initiative is structured upon seven strategic priorities: (i) put Londoners at the core, (ii) provide access to open data, (iii) leverage London’s research, technology, and creative talent, (iv) collaboration networks, (v) enable London to adapt and grow, (vi) enable City Hall to better serve Londoners’ needs, (vii) offer a ‘smarter’ experience for all. In the strategy it is recognized that London is already a vibrant, international and cosmopolitan business and tourist hub, one of the most significant centres of creativity and culture globally -for this reason the entire strategy is focused on upgrading and enforcing these qualities. Measures loosely connected with cultural heritage promotion can be found under the initiatives (vi) and (vii). It can be argued that, in general lines, the promotion of London’s cultural heritage in the context of its smart city strategy is primarily seen as a service to citizens and

visitors, integrated with other smart city services such as city hall services and smart mobility around the city.

interest is

Table 1. Tabular display with field research findings across the three cases (authors’ elaboration)

2.2.3 Analysis of findings

The first overarching observation is that cultural heritage preservation and promotion can be regarded as a differentiating component among smart city strategies, reflecting different lines of thinking and serving different goals. In particular, in Barcelona’s strategy it is seen as a touristic development component; in Amsterdam’s strategy it is regarded as a quality of life component; and in London’s strategy it is regarded as a public service component. These three different approaches denote the different positioning of cultural heritage in the context of technology led urban development and the diverging roles that it can acquire towards local urban and social development. This fact carries contextual, management and technical implications about the integration of cultural heritage development within smart cities, which call for different courses of action depending on the case.

Another important observation to be made is that, although themes such as cultural, touristic, creativity and innovation

driven development, accessibility to services and quality of life are horizontally present throughout the examined smart city strategies, cultural heritage promotion as an objective is not particularly pronounced in any of them. This comes as a surprise, given that all three of the examined cities are places endowed with rich history, vibrant culture and abundant points of historical interest, which could play a major role towards the enhancement of urban intelligence. In this sense, one would expect that –at least for these cities- cultural heritage would be used as an overarching asset upon which smart city approaches would be built, capitalizing on the multifaceted roles that it can play towards enhancing urban innovation, liveability and socio-economic prosperity. Yet it seems that the focus of smart cities tends to be geared towards more ‘fashionable’ trends of thinking about urban development, such as liveability, inclusivity, accessibility and openness, and cultural heritage is regarded as one of the many low-tier components that could contribute to these objectives.

A third remark to be made regards the specific smart city applications which are included in the strategies and pertain to the cultural heritage preservation and promotion objective. We observe an absence of smart city applications referring to cultural heritage per se. Instead, the included applications have a broader focus and attempt to integrate elements of cultural heritage within a broader system of information and services provision. For example, cultural points of interest are integrated, along with other leisure and commercial attractions, in tourist maps and agendas, or within wayfinding applications and journey planners. There is also an array of smart city applications that are not directly related to cultural heritage itself, but can be regarded as external facilitators of cultural heritage promotion. Typical examples include collaborative (neighbourhood) city making and urban planning applications and citizen reporting platforms.

After the above analysis, one could argue that in general lines smart cities fail to successfully incorporate the component of cultural heritage within smart cities and the vision towards long term, innovation and sustainability-led urban development. Although potential applications and approaches abound, cultural heritage currently stands for a mostly unexploited asset, presenting multiple integration opportunities within smart city contexts. Most of these opportunities are currently bypassed. In this paper we made a first step towards mitigating this weakness, highlighting both the specific benefits of including cultural heritage in smart city initiatives, and several different pathways to be pursued to this end.

3. CONCLUSIONS

Another general observation emerging from our research is that there seems to be an integration gap between overarching smart city solutions and site-based cultural heritage preservation and promotion applications. Although both areas are currently entering a phase of maturity, and share (at least some) common concerns, they have not worked in consort so far. It is also possible that research at the intersection of smart cities and cultural heritage might have more to benefit by focusing on different types of cases and methods. For example, there might be smaller historical cities that could showcase more advanced smart city solutions in the areas of cultural heritage preservation and promotion, given that they will typically encompass narrower economies and be more focused toward touristic driven development.

The above observations and findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how local cultural heritage can be strategically underpinned through the smart city approach, and namely the positioning of the cultural heritage preservation and promotion objective in the smart city context, and which tools and applications are available to this end. Using these results, policy makers, researchers and developers can create more documented, targeted and informed strategies and tools towards incorporating cultural heritage objectives in technology-led urban development.

REFERENCES

Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2012. Barcelona urban habitat: The vision, approach, and projects of the City of Barcelona towards smart cities (presentation by L. Olivella), Smart City Summit 2012, 2 July, Milano.

Available:http://www.theinnovationgroup.it/wpcontent/uploa ds/2012/05/Olivella_City-of-Barcelona.pdf

Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2013. Barcelona Smart City; The vision, focus and projects of the City of Barcelona in the context of Smart Cities.

Available: http://www.slideshare.net/MicrosoftSuomi/city-next-smartbarcelona-28102013.

Allwinkle, S. and Cruickshank, P., 2011. Creating Smart-er Cities: An Overview. Journal of Urban Technology, 18(2), pp. 1-16.

Amato, F., Chianese, A., Moscato, V., Picariello, A., and Sperli, G., 2012. SNOPS: a smart environment for cultural heritage applications. Twelfth ACM International Workshop on Web information and data management, pp. 49-56.

Amsterdam Smart City official website, 2016. Available: https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/

Angelidou, M., 2016. Four European Smart City Strategies. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 4, pp.18-30

Angelidou, M., 2015. Smart Cities: a conjuncture of four forces. Cities, 47, pp. 95–106.

Angelidou, M., 2014. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities, 41, pp. S3-S11.

Anthopoulos, L., 2017. Smart utopia VS smart reality: Learning by experience from 10 smart city cases. Cities, 63, pp. 128-148.

Bajracharya, B., Cattell, D. and Khanjanasthiti, I., 2014. Challenges and Opportunities to Develop a Smart City: A Case Study of Gold Coast, Australia. REAL CORP 2014, 21-23 May 2014, Vienna, Austria.

Bakici, T., Almirall, E., and Wareham, J., 2012. A Smart City Initiative: the Case of Barcelona. Journal of the knowledge economy. Special Issue: Smart Cities and the Future Internet in Europe, pp. 135-148.

Barcelona Smart City official website, 2017. Available: http://smartcity.bcn.cat/en/

Bélissent, J., 2012. Governments Embrace New Modes Of Constituent Engagement; Social Media, Mobility, And Open Data Transform eGovernment. Forrester for CIOs: Forrester.

Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C., and Nijkamp, P., 2009. Smart Cities in Europe. Serie Research Memoranda 0048 (VU University Amsterdam, Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Econometrics).

Chianese, A., Piccialli, F., and Valente, I., 2015. Smart environments and cultural heritage: a novel approach to create intelligent cultural spaces. Journal of Location Based Services, 9(3), pp. 209-234.

Eisenhardt, K. M., 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review, 14(4), pp. 532-550.

Garau, C., 2014. Smart paths for advanced management of cultural heritage. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), pp. 286-293.

Giffinger, R., Fertner, C., Kramar, H., Kalasek, R., Pichler-Milanović, N., and Meijers, E., 2007. Smart cities; Ranking of European medium-sized cities (final report): Vienna University of Technology, University of Ljubljana, Delft University of Technology.

Goh, K., 2015. Who’s Smart? Whose City? The Sociopolitics of Urban Intelligence. In Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities, Springer, pp. 169-187.

Greater London Authority. 2016. The future of smart: Harnessing digital innovation to make London the best city in the world (update report of the Smart London Plan 2013). Available: https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/business- and-economy/science-and-technology/smart-london/future-smart

Greater London Authority, 2013. Smart London Plan. Available:

https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/smart_london_ plan.pdf

Hollands, R. G., 2008. Will the real smart city please stand up? City, 12(3), pp. 303-320.

Kitchin, R., 2015. Making sense of smart cities: addressing present shortcomings. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8, pp. 131-136.

Lee, J.-H., and Gong Hancock, M., 2012. Toward a framework for Smart Cities: A Comparison of Seoul, San Francisco and Amsterdam. Innovations for Smart Green City. What’s

Working, What’s Not and What’s Next, 26-27 June 2012,

Stanford. Available:

http://fsi.stanford.edu/events/innovations_for_smart_green_ci ty_whats_working_whats_not_and_whats_next/

Mora, L., and Bolici, R., 2017. How to Become a Smart City: Learning from Amsterdam. Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions, Springer, pp. 251-266.

Paskaleva, K. A., 2011. The smart city: A nexus for open innovation? Intelligent Buildings International, 3(3), pp. 153-171.

Schaffers, H., Komninos, N., Pallot, M., Trousse, B., Nilsson, M. and Oliveira, A., 2011. Smart Cities and the Future Internet: Towards Cooperation Frameworks for Open Innovation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer.

Schulte, M. A., 2012. IDC Smart Cities Benchmark; Deutschland 2012 (in german): IDC. Available: https://www.karlsruhe.de/b2/wirtschaftsstandort/rankings/sta edteranking/HF_sections/content/ZZjZJCvt1QmCTK/ZZkzT HI8aXhrBV/IDC

Smart Cities Benchmark - Zusammenfassung für Städte und Gemeinden.pdf Smart London official website, 2017. Available: https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/business-and-economy/science-and-technology/smart-london

Tranos, E., and Gertner, D., 2012. Smart networked cities? The European Journal of Social Science Research, 25(2), pp. 175-190.

UNESCO, 2017. What is meant by "cultural heritage"? Available:

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/illicit- trafficking-of-cultural-property/unesco-database-of-national- cultural-heritage-laws/frequently-asked-questions/definition-of-the-cultural-heritage/

Vattano, S., 2014. Smart Technology for smart regeneration of cultural heritage. Italian smart cities in comparison. In MWF2014: Museums and the Web Florence.

Available: http://mwf2014.museumsandtheweb.com

Yin, R., 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods (3rd edition ed.). London: SAGE Publications.