Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:00

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Electronic Learning Systems in Hong Kong

Business Organizations: A Study of Early and Late

Adopters

Simon C. H. Chan & Eric W. T. Ngai

To cite this article: Simon C. H. Chan & Eric W. T. Ngai (2012) Electronic Learning Systems in Hong Kong Business Organizations: A Study of Early and Late Adopters, Journal of Education for Business, 87:3, 170-177, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.586005

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.586005

Published online: 01 Feb 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 130

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.586005

Electronic Learning Systems in Hong Kong Business

Organizations: A Study of Early and Late Adopters

Simon C. H. Chan and Eric W. T. Ngai

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Based on the diffusion of innovation theory (E. M. Rogers, 1983, 1995), the authors examined the antecedents of the adoption of electronic learning (e-learning) systems by using a time-based assessment model (R. C. Beatty, J. P. Shim, & M. C. Jones, 2001), which classified adopters into categories upon point in time when adopting e-learning systems. Based on a structured questionnaire survey from 143 business organizations, results indicated significant differences in the reasons why adopters decided to adopt e-learning systems. Technical compatibility, top management support, and social pressures had a greater influence on the adoption of the e-learning systems by the early adopters than on the late adopters.

Keywords: adopters, electronic learning systems, time-based analysis

Electronic learning (e-learning) systems have long become an alternative for organizations in their move toward their vision of organizational learning. The context of learning is evolving from the traditional classroom setting to the self-service online format. The rapid development of e-learning systems has prompted business organizations to reassess and redesign the way individual learners learn via the Internet and technologies (Halawi, McCarthy, & Pires, 2009; Zhang, Zhao, Zhou, & Nunamaker, 2004). E-learning provides an ideal medium to deliver learning materials, which eventually improve knowledge sharing and organization performance (Rosenberg, 2000). The speed and connectivity through the network provide operational and administrative benefits to organizations, benefits that ultimately improve their compet-itive advantages (Chang, Hsu, Smith, & Wang, 2004).

LITERATURE REVIEW

There are many definitions for e-learning, but there is real no universal definition. E-learning can be defined as a web-based system that enables users and learners to share infor-mation (Sun, Tsai, Finger, Chen, & Yeh,2008). In its broad-est definition, e-learning is Internet-enabled learning, which offers and delivers learning materials in multiple formats,

Correspondence should be addressed to Simon C. H. Chan, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Department of Management and Marketing, Hung Hom, Kowloon 852, Hong Kong. E-mail: mssimon@polyu.edu.hk

supported by a networked community of learners, instruc-tors, content developers, and experts (Gunasekaran, McNeil, & Shaul, 2002). In a narrower definition, e-learning is defined as instructional content or a learning experience enabled by electronic information technologies including the Internet, intranets, and extranets (Wang, Wang, & Shee, 2007). E-learning system, in this study, is then defined as a web-based system that creates, fosters, delivers, and facilitates learning experience and training materials to individuals. The use of interactive network technologies by individual learners is at all time and elsewhere. The terme-learning environmentis also commonly used to describe the platform supporting the self-learning process of individual learners (Sun et al., 2008). The learning environment is a function of knowledge-derived tools and devices by which individual learners acquire infor-mation and knowledge (Liao & Lu, 2008; Liaw, Chen, & Huang, 2008).

Empirical studies have made valuable contributions to the effectiveness of e-learning systems (e.g., Sun et al., 2008). Alavi and Leider (2001) indicated that institutional strat-egy and information technology are important indicators of the development of e-learning systems. The technology fea-tures engage the psychological learning processes of individ-uals through which learning occurs and results in the desired learning outcomes. Johnson, Hornik, and Salas (2008) and Piccoli, Ahmad, and Ives (2001) highlighted the character-istics of individual trainees and technology and emphasized that the creation of a shared learning environment is signif-icantly associated with e-learning outcomes. More recently,

ELECTRONIC LEARNING SYSTEMS 171

Johnson, Gueutal, and Falbe (2009) found the significant effects of individual characteristics and technologies on e-learning outcomes. These findings show the positive influ-ence on the relationship between the antecedents and the adoption of e-learning systems.

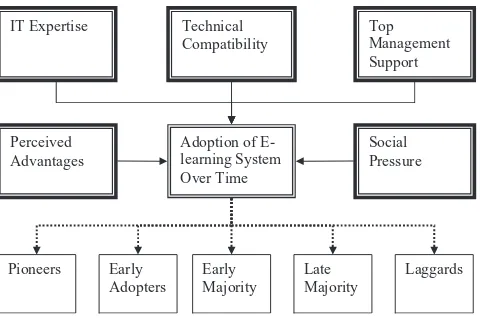

As information technology (IT) systems adoption has taken place and has been investigated over time (Harrison & Waite, 2006), studies appear to identify the reasons for deci-sions on innovation adoption. Rogers’ (1983, 1995) diffusion of innovation theory refers to the spread of abstract ideas and concepts, technical information, and actual practices from sources to adopters within a social system. This theory was specifically used in determining the attributes of innovations adopted by potential organizations, which are classified into five adopter categories: a) pioneers, b) early adopters, c) early majority, d) late majority, and e) laggards. Although the five categories do not have a standard proportion, they follow a bell-shaped curve based on the point in time when they adopted IT systems (Beatty et al., 2001; Harrison & Waite, 2006). In a study of corporate website adoption, Beatty et al. (2001) adopted the time-based assessment model to exam-ine the relationship between the factors and the differences among the different stages of adopters. Based on the ra-tionality of adoption decisions by organizations at different times (Beatty et al.), the adopters of e-learning systems are classified into five main categories based on the number of years they have been adopting e-learning systems: a) pioneers (3 years or longer), b) early adopters (at least 2 years but less than 3 years), c) early majority (at least 1 year but less than 2 years), d) late majority (less than 1 year), and e) laggards (presently developing). To examine adoption decisions, pio-neers, early adopters, and early majority adopters have been defined as early adopters. Meanwhile, late majority adopters and laggards are identified as later adopters.

In reviewing prior IT adoption literature, the majority of the reasons the affect adoption decision were generally classified according to the characteristics of organizations or the environment, and as benefits of IT systems (Downs & Mohr, 1976; Hung, Hung, Tsai, & Jiang, 2010; Kuan & Chau, 2001). Empirical studies have identified organi-zational size (Lee & Xia, 2006), organiorgani-zational commitment (Ramamurthy, Sen, & Sinha, 2008), top management support (Lee & Shim, 2007), and innovation and environment charac-teristics (Premkumar & Roberts, 1999) as the antecedents of adoption decision. Chau and Tam (1997) developed a model for open systems adoption that incorporates three aspects, namely, the external environment, the organizational tech-nology, and the characteristics of the technology.

Several studies have emphasized organizational and indi-vidual readiness with regard to the adoption of IT systems (e.g., Liu, 2005). The perceived advantages and the character-istics of individual learners (Shim, Shropshire, Park, Harris, & Campbell, 2007) have been found as the antecedents in-fluencing the adoption of IT systems. Top management sup-port (Grover, 1993), technical compatibility (Raho, Beholav,

& Fiedler, 1987), and social pressures (Flanagin, 2000) are also considered as antecedents influencing the adoption de-cision. Sabherwal and Sabherwal (2005) demonstrated that the antecedents posited by the diffusion of information inno-vations theory underlie a variety of IT systems. In particular, adopters put more emphasis on the perceived advantages and technical compatibility of e-learning systems. As a result, perceived advantages, IT expertise, technical compatibility, top management support, and social pressures were identified as potential factors of adoption of e-learning systems.

HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

In this study, five antecedents (perceived advantages, IT ex-pertise, technical compatibility, top management support, and social pressures) were included to examine the influence of e-learning systems among adopters. In addition, adopters were classified into five categories (pioneers, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards) based on the num-ber of years that organizations have adopted the e-learning systems. Figure 1 depicts the relationships of the five an-tecedents and the e-learning systems adoption over time.

Perceived Advantages

An e-learning system is a cost-effective training delivery option for individual learners. The perceived advantages in-clude reduced costs, delivery of consistent and timely infor-mation, and better communication between instructors and individual learners (Gordon, 2003; Smith & Mitry, 2008). The perceived advantages have been significantly associated with e-learning systems adoption (Wang, 2003). If an organi-zation has a quick response to e-learning systems adoption, early adopters may benefit more than the later adopters. We then hypothesized the following:

FIGURE 1 E-learning adoption model over time.

Hypothesis 1(H1): Earlier adopters place more importance

on the perceived advantages of having an e-learning sys-tem than do later adopters.

Information Technology Expertise

An important factor in e-learning systems adoption depends on the IT usage of individual learners. Individual learners’ basic knowledge and skills in computers, networks, and soft-ware systems are required in adopting e-learning systems. The characteristics of individual learners are important and are significantly associated with e-learning adoption decision (Johnson et al., 2008; Piccoli et al., 2001). Early adopters are more likely to adopt e-learning systems than later adopters if individual learners have a higher level of IT expertise and are familiar with an organization’s IT values. Hence,

H2: Earlier adopters have more individual learners with IT

expertise for e-learning systems than do later adopters.

Technical Compatibility

E-learning systems design is necessary for a good foundation on technical infrastructure and compatibility of technology. Technical compatibility is defined as the extent to which the adoption of e-learning systems can be integrated into the existing IT infrastructure and learning environment. The incompatibility of IT adoption with an organization’s existing hardware, software, or networks largely inhibits the adoption of e-learning systems (Premkumar & Ramamurthy, 1995). The more sophisticated the existing IT architecture is, the higher the willingness of organizations to adopt e-learning systems.

H3: The e-learning system is perceived as more technically

compatible by earlier adopters than by later adopters.

Top Management Support

Top management support is found to be significantly asso-ciated with the adoption of IT systems (Wong, 2005). Top management support is defined as the extent to which there is decision support from the top management of an organi-zation (Lee & Shim, 2007). Their support is critical to the success of adopting e-learning systems. In other words, an earlier adopter would request for top management support to adopt e-learning systems rather than the later adopters. We propose that the support of top management is important for the e-learning systems adoption process. Hence,

H4: Earlier adopters have greater top management support

on having e-learning systems than do later adopters.

Social Pressures

Social pressures are generally perceived to be associated with the adoption of IT systems. Social pressures refer to the degree in which organizations feel pressure from their

competitors or organizations in the same industry. Evidence has shown that external forces of the environment can in-fluence organizations’ adoption decision (Flanagin, 2000). Organizations view the IT adoption as a business strategy in competing with existing competitors. We then posited the following:

H5: Earlier adopters face more social pressure to have an

e-learning system than do later adopters.

METHOD

Instrument

To test the hypotheses, a survey questionnaire was developed to measure the relevant constructs. A pilot test was admin-istrated to ensure the validity of the instruments. First, the questionnaire was refined by a pilot test involving the as-sistance of two professors. Based on the comments, some measurement items were modified. Second, 10 managerial practitioners reviewed the questionnaire, as well as the clar-ity of the content and appropriateness of the items.

The questionnaire items used were mainly from existing scales. The items for perceived advantages (9 items with a 7-point scale) were largely based on the unique context of e-learning systems. IT expertise (5 items with a 7-point scale), developed by Flanagin (2000), was used to mea-sure the extent to which individuals are sophisticated in the use of IT. In addition, technical compatibility (4 items with a 7-point scale), also developed by Flanagin (2000), was used to measure technical support. Top management support (4 items with a 7-point scale), developed by Grover (1993), was used to measure top management attitude toward e-learning adoption. Also, social pressure (6 items with a 7-point scale), developed by Flanagin (2000), was used to measure external pressure from competitors.

Sample and Procedures

A sample was randomly drawn from the membership list of an e-learning conference in Hong Kong. The conference con-tact list provided by the host was used, and 345 business or-ganization managers were selected. A survey was conducted by sending structured questionnaires, with the objective of the study specified in the cover letter. The survey partici-pants were requested to forward the survey questionnaires to their staff responsible for e-learning systems adoption. The respondents were then asked to complete the question-naire. A total of 143 questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 41.5%. The potential nonresponse bias was examined by comparing the first half of the responses received with the second half (the theoretical nonrespon-dents). The mean differences between the two groups of responses in a random selection of measurement items in the

ELECTRONIC LEARNING SYSTEMS 173

TABLE 1

Demographic Profile of the Respondents

Characteristic %

Organization size

Less than 500 employees 44.1

Between 500 and 2,000 employees 30.8

More than 2,000 employees 25.1

Industry

questionnaire were tested. There were no significant differ-ences between the respondents and nonrespondents.

Profile of Respondents

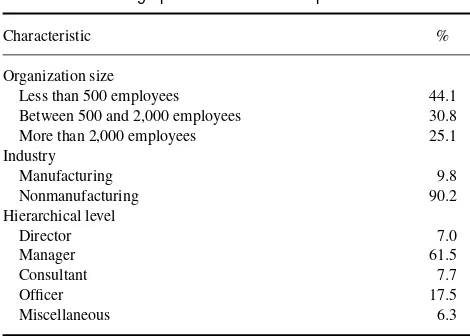

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of respondents. Or-ganizations with fewer than 500 employees made up 44.1% of the responding organizations, and those with over 500 em-ployees comprised 55.9% of all responding organizations. Nearly 90% of the participating organizations represented nonmanufacturing industry sector. Over 75% of the respon-dents held managerial or equivalent positions, including di-rector, manager, and consultant positions, and were among decision makers for e-learning systems. The relative senior-ity of the respondents gives assurance that the sample is valid because these respondents are more likely knowledgeable of organizational strategies behind e-learning adoption.

Statistical Procedures

Data were analyzed by using the exploratory factor analy-sis (EFA) to assess the construct validity of the independent variables (Doll & Torkzadeh, 1988; Kerlinger, 1986). EFA offers a way of constructing an interrelated set of indicators, meeting one of the conditions for construct validity (Zmud & Boynton, 1991). A principal component factor analysis using the Varimax criterion was performed to assess unidimension-ality. A rotation to obtain a simple and interpretable result was accomplished using the oblique rotation technique. Two essential criteria are involved in determining the number of factors in the analysis: (a) the magnitude of the eigenvalue (with a minimum required value of 1.0; Kaiser, 1974) and (b) the scree test (Cattell, 1966). Moreover, convergent va-lidity is demonstrated if the items load strongly with factor loadings >0.50. Discriminant validity is achieved if each

item loads stronger on its associated factor than on any other loadings. Items with factors of at least 0.30 and at least a 0.10 difference between their loading on other factors were examined to determine if such items conceptually measured

another factor (Messick, 1990, 1995). The reliability (i.e., internally consistent) of the score derived for each factor was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (>.70; Cronbach, 1961;

Nunnally, 1978).

Following the EFA, the effects of the five adopter cate-gories on perceived advantages, IT expertise, technical com-patibility, top management support, and social pressures were examined by using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). It is an extension of an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to accommodate more than one dependent vari-able (adopters; i.e., pioneers, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards). MANOVA measures the differ-ences between two or more dependent variances based on a set of categorical variables (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995).

RESULTS

EFA

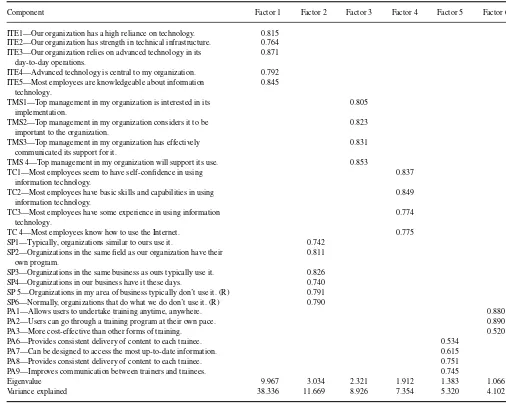

Using the criteria as stated in the statistical analysis section, an EFA of the antecedents of e-learning systems adoption was performed. The total number of factors recommended was six. A total of 26 items remained after two items were dropped from the original 28 items due to cross loading in the factor analysis. The factor structure resulted in 26 items measuring six distinct factors and explaining 75.7% of the variance, as shown in Table 2. The items predicted to measure perceived advantages were loaded on two separate factors rather than one single variable, representing perceived direct advantages and perceived indirect advantages. Together, the structure of the six factors went well with the structure of the items. The results showed that items of the same construct distinctly exhibited higher factor loading on a single construct rather than on other constructs, suggesting adequate convergent and discriminant validity.

The Cronbach’s coefficient of perceived direct advantages (α =.76), IT expertise (α =.93), technical compatibility

(α =.92), top management support (α= .93), and social

pressures (α=.91) had coefficient alpha values exceeding

.70. Perceived indirect advantages exhibited marginal failure (α=.67).

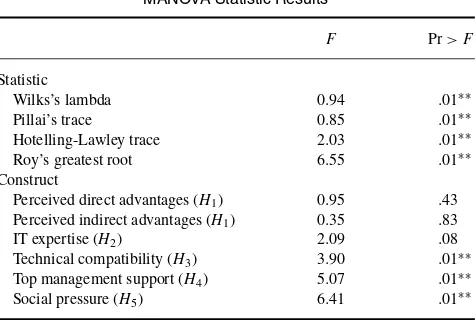

MANOVA

As shown in Table 3, MANOVA was used to test the hypothe-ses. The Wilks’s criterion for the test of overall statistical effect was significant,F()=0.94,p =.01, indicating that the means for the five categories of adopters contain signifi-cant differences in the constructs of technical compatibility, top management support, and social pressures (atα=.05).

The findings do not provide support for the hypotheses on perceived direct and indirect advantages (H1) and IT

exper-tise (H2). However, they support the hypotheses on technical

TABLE 2

Operationalization of Research Variables

Component Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Factor 5 Factor 6

ITE1—Our organization has a high reliance on technology. 0.815

ITE2—Our organization has strength in technical infrastructure. 0.764

ITE3—Our organization relies on advanced technology in its day-to-day operations.

0.871

ITE4—Advanced technology is central to my organization. 0.792

ITE5—Most employees are knowledgeable about information technology.

0.845

TMS1—Top management in my organization is interested in its implementation.

0.805

TMS2—Top management in my organization considers it to be important to the organization.

0.823

TMS3—Top management in my organization has effectively communicated its support for it.

0.831

TMS 4—Top management in my organization will support its use. 0.853

TC1—Most employees seem to have self-confidence in using information technology.

0.837

TC2—Most employees have basic skills and capabilities in using information technology.

0.849

TC3—Most employees have some experience in using information technology.

0.774

TC 4—Most employees know how to use the Internet. 0.775

SP1—Typically, organizations similar to ours use it. 0.742

SP2—Organizations in the same field as our organization have their own program.

0.811

SP3—Organizations in the same business as ours typically use it. 0.826

SP4—Organizations in our business have it these days. 0.740

SP 5—Organizations in my area of business typically don’t use it. (R) 0.791

SP6—Normally, organizations that do what we do don’t use it. (R) 0.790

PA1—Allows users to undertake training anytime, anywhere. 0.880

PA2—Users can go through a training program at their own pace. 0.890

PA3—More cost-effective than other forms of training. 0.520

PA6—Provides consistent delivery of content to each trainee. 0.534

PA7—Can be designed to access the most up-to-date information. 0.615

PA8—Provides consistent delivery of content to each trainee. 0.751

PA9—Improves communication between trainers and trainees. 0.745

Eigenvalue 9.967 3.034 2.321 1.912 1.383 1.066

Variance explained 38.336 11.669 8.926 7.354 5.320 4.102

Note.(R) indicates reverse coding. TC=technical compatibility; ITE=information technology expertise; PA=perceived advantages; SP=social pressures; TMS=top management support.

compatibility (H3), top management support (H4), and social

pressures (H5).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we examined the antecedents of the adop-tion of e-learning systems using a time-based assessment model. Some findings from previous IT adoption literature on the antecedents of the adopters of e-learning systems over a particular time period (Rogers, 1983, 1995) have been con-firmed. The results of the present study did not support per-ceived advantages (H1) and IT expertise (H2); instead, they

supported hypotheses related to technical compatibility (H3),

top management support (H4), and social pressures (H5).

In contrast to the results of Beatty et al.’s (2006) website adoption, there was no significant difference between the early and late adopters of the perceived advantages (H1) of

e-learning systems. This implied that early and late adopters seem to favor reasonably the perceived advantages of e-learning systems as awareness of IT innovations increases. One possibility is that the perceived benefits of e-learning systems, such as the stimulation of individuals’ learning mo-tivation and attitude (Liaw et al., 2008) and cost reduction (Chau & Tam, 2000), would apply among adopters over time as the diffusion process continues. Early and late adopters of e-learning systems perceive the advantages to organization and individual development despite the early and late adop-tion (Barolli, Koyama, Durresi, & De Marco, 2006; Shim et al., 2007).

ELECTRONIC LEARNING SYSTEMS 175

Hotelling-Lawley trace 2.03 .01∗∗

Roy’s greatest root 6.55 .01∗∗

Construct

Perceived direct advantages (H1) 0.95 .43

Perceived indirect advantages (H1) 0.35 .83

IT expertise (H2) 2.09 .08

Technical compatibility (H3) 3.90 .01∗∗

Top management support (H4) 5.07 .01∗∗

Social pressure (H5) 6.41 .01∗∗

∗∗p<.01.

The nonsignificant result for IT expertise (H2) is

sur-prising. One possible explanation is that the adopters of e-learning systems may not necessarily request individual learners with high levels of expertise in IT. E-learning activ-ities only require individual learners to possess basic tech-nical skills while adopting systems such as an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system that demands individual learners with better IT knowledge and skills (Morton & Hu, 2008; Ngai, Law, & Wat, 2008; Waarts, van Everdingen, & van Hillegersberg, 2002).

Consistent with the diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 1983, 1985), early adopters have placed more em-phasis on technical compatibility, top management support, and social pressure when considering whether to acquire e-learning systems. This highlights the importance of IT com-patibility in affecting the adoption decision (Premkumar & Ramamurthy, 1995). The e-learning system is perceived as more technically compatible by early adopters than by late adopters (H3). In addition, early adopters have strong top management support for e-learning systems (H4). Consistent

with the IT literature, top management support would ensure the successful adoption of new skills and the maintenance of competitiveness within the industry (Beatty et al., 2006; Lee & Shim, 2007). This is a confirmation of top management support as a champion for innovation adoption, including the e-learning system. Finally, the early adopters of e-learning systems are influenced by social pressure because they may have eventually decided to adopt the e-learning systems based on widespread acceptance among their competitors (H5). According to Flanagin (2000), organizations acquiring

e-learning systems because of their expected benefits is un-likely. Instead, they might have considered using e-learning systems due to social pressure than from the existing compet-itive market. In summary, the adoption of e-learning systems can meet the needs of organizations and provide a great learn-ing environment and experience to individual learners.

Limitations

Only a relatively small sample size of 143 adopters was uti-lized. Another potential limitation of the present study was that data were collected from business organizations. More research is needed for the application of the results to other types of organizational settings such as those characterized by the strictly regulated usage of e-learning systems (e.g., training institutes). Although in the present study we exam-ined five adoption innovation antecedents and e-learning sys-tems adoption over time, the characteristics of adopters such as organization size (Lee & Xia, 2006) apparently have impli-cations for potential e-learning adopters. Future researchers should explore the relationship between the antecedents of adoption innovation and the characteristics of adopters. Fi-nally, this study was conducted using a common method source questionnaire for all variables, which may lead to common method bias.

Conclusion

The contribution of this study is the extension of e-learning system literature through the examination of the relation-ship among the antecedents and the adopters of e-learning systems over time. This approach adds value, as it com-pares the adopters of e-learning systems on a time-frame basis. The findings suggest that technical compatibility, top management support, and social pressures have significant differences between early and late adopters. Compared with late adopters, early adopters view e-learning systems as more compatible with existing technology infrastructures, have po-tential to gain more support from top management, and are in accordance with pressures from the social learning environ-ment. However, the study also shows no significant difference between the early and late adopters in terms of perceived ad-vantages. This nonsignificance may be attributed to the fact that the perceived benefits of e-learning systems become ap-plicable among adopters over time as the diffusion process continues.

This study also shows that the success of decisions on the adoption of e-learning systems depends on the commitment of top management and its technical infrastructure. Organiza-tions also need to experience social pressures when consider adopting e-learning systems. We believe that more research is required to further develop our understanding of early and late adopters in e-learning systems, and determine other dif-ferences between early and late adopters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for the constructive comments of the referees and the editors on an earlier version of this arti-cle. This research was supported in part by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University under grant number 8CGP.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M., & Leider, D. (2001). Technology-mediated learning: A call for greater depth and breadth of research.Information Systems Research,

12(1), 1–10.

Barolli, L., Koyama, A., Durresi, A., & De Marco, G. (2006). A web-based e-learning system for increasing study efficiency by stimulating learner’s motivation.Information Systems Frontier,8, 297–306.

Beatty, R. C., Shim, J. P., & Jones, M. C. (2001). Factors influencing cor-porate web site adoption: A time-based assessment.Information & Man-agement,38, 337–354.

Cattell, R. B. (1966).Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Chang, W. C., Hsu, H. H., Smith, T. K., & Wang, C. C. (2004). Enhancing SCORM metadata for assessment authoring in e-learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,20, 305–316.

Chau, P. Y. K., & Tam, K. Y. (1997). Factors affecting the adoption of open systems: An exploratory study.MIS Quarterly,21, 1–24.

Chau, P. Y. K., & Tam, K. Y. (2000). Organizational adoption of open sys-tems: A “technology-push, need-pull” perspective.Information & Man-agement,37, 229–239.

Cronbach, L. J. (1961). Coefficient alpha and the structure of tests. Psy-chometrika,16, 297–334.

Doll, W. J., & Torkzadeh, G. (1988). The measurement of end-user comput-ing satisfaction.MIS Quarterly,12, 259–274.

Downs, G. W., & Mohr, L. B. (1976). Conceptual issues in the study of innovation.Administrative Science Quarterly,21, 700–714.

Flanagin, A. J. (2000). Social Pressures on organizational website adoption.

Human Communication Research,26, 618–646.

Gordon, J. (2003). E-learning tagged as best corporate IT investment. E-learning,4(1), 8.

Grover, V. (1993). An empirically derived model for the adoption of customer-based interorganizational systems. Decision Sciences, 24, 603–640.

Gunasekaran, A., McNeil, R. D., & Shaul, D. (2002). E-learning: Re-search and applications.Industrial and Commercial Training,34(2), 44– 53.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995).

Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Halawi, L. A., McCarthy, R. V., & Pires, S. (2009). An evaluation of

e-learning on the basis of Bloom’s taxonomy: An exploratory study.Journal of Education for Business,84, 374–380.

Harrison, T., & Waite, K. (2006). A time-based assessment of the influ-ences, uses and benefits of intermediary website adoption.Information & Management,43, 1002–1013.

Hung, S. Y., Hung, W. H., Tsai, C. A., & Jiang, S. C. (2010). Critical factors of hospital adoption on CRM system: Organizational and information system perspectives.Decision Support Systems,48, 592–603.

Johnson, R. D., Gueutal, H., & Falbe, C. M. (2009). Technology, trainees, metacognitive activity and e-learning effectiveness.Journal of Manage-rial Psychology,24, 545–566.

Johnson, R. D., Hornik, S. R., & Salas, E. (2008). An empirical examination of factors contributing to the creation of successful e-learning environ-ments.International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,66, 356–69. Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity.Psychometrica,39,

31–36.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1986).Foundations of behavioral research(3rd ed.). New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Kuan, K. K. Y., & Chau, P. Y. K. (2001). A perception-based model for EDI adoption in small businesses using a technology-organization-environment framework.Information & Management,38, 507–521.

Lee, C. P., & Shim, J. P. (2007). An exploratory study of radio frequency identification (RFID) adoption in the healthcare industry.European Jour-nal of Information Systems,16, 712–724.

Lee, G., & Xia, W. (2006). Organizational size and IT innovation adoption: A meta-analysis. Information & Management, 43, 975– 985.

Liao, H. L., & Lu, H. P. (2008). The role of experience and innovation characteristics in the adoption and continued use of e-learning websites.

Computers & Education,51, 1405–1416.

Liaw, S. S., Chen, G. D., & Huang, H. M. (2008). Users’ attitudes toward web-based collaborative learning systems for knowledge management.

Computers & Education,50, 950–961.

Liu, N. Y. (2005). Internet and e-commerce adoption by the Taiwan semiconductor industry.Industrial Management & Data Systems,105, 476–490.

Messick, S. M. (1990).Validity of test interpretation and use (No.ETS-PR-90–11). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Messick, S. M. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning.American Psychologist,50, 741–749.

Morton, N. A., & Hu, Q. (2008). Implications of the fit between or-ganizational structure and ERP: A structural contingency theory per-spective.International Journal of Information Management,28, 391– 402.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978).Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Ngai, E. W. T., Law, C. C. H., & Wat, F. K. T. (2008). Examining the critical success factors in the adoption of enterprise resource planning.

Computers in Industry,59, 548–564.

Piccoli, G., Ahmad, R., & Ives, B. (2001). Web-based virtual learn-ing environments: A research framework and a preliminary assess-ment of effectiveness in basic IT skills training.MIS Quarterly, 25, 401–426.

Premkumar, G., & Ramamurthy, K. (1995). The role of interorgani-zational and organiinterorgani-zational factors on the decision mode for adop-tion of interorganizaadop-tional systems. Decision Sciences, 26, 303– 336.

Premkumar, G., & Roberts, M. (1999). Adoption of new information tech-nologies in rural small businesses.Omega,27, 467–484.

Raho, L. E., Beholav, K. A., & Fiedler, K. A. (1987). Assimilating new technologies into the organization: An assessment of McFarlan and McKinney’s model.MIS Quarterly,11, 47–57.

Ramamurthy, K., Sen, A., & Sinha, A. P. (2008). An empirical investigation of the key determinants of data warehouse adoption.Decision Support Systems,44, 817–841.

Rogers, E. M. (1983).Diffusion of innovations(1st ed.). New York, NY: The Free Press.

Rogers, E. M. (1995).Diffusion of innovations(4th ed.). New York, NY: The Free Press.

Rosenberg, M. J. (2000).E-learning: Strategies for delivering knowledge in the digital age. New York, NY: Viking Press.

Sabherwal, R., & Sabherwal, S. (2005). Knowledge management using information technology: Determinants of short-term impact on firm value.

Decision Sciences,36, 531–567.

Shim, J. P., Shropshire, J., Park, S., Harris, H., & Campbell, N. (2007). Podcasting for e-learning, communication, and delivery.Industrial Man-agement & Data Systems,107, 587–600.

Smith, D. E., & Mitry, D. J. (2008). Investigate of higher education: The real costs and quality of online programs.Journal of Education for Business,

83, 147–152.

Sun, P. C., Tsai, R. J., Finger, G., Chen, Y. Y., & Yeh, D. (2008). What drives a successful e-Learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction.Computers and Education,50, 1183–1202.

Waarts, E., van Everdingen, Y. M., & van Hillegersberg, J. (2002). The dynamics of factors affecting the adoption of innovations.The Journal of Product Innovation Management,19, 412–423.

Wang, Y. S., Wang, H. Y., & Shee, D. Y. (2007). Measuring e-learning systems success in an organizational context: Scale

ELECTRONIC LEARNING SYSTEMS 177

opment and validation. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 1792– 1808.

Wang, Y. X. (2003). Assessment of learner satisfaction with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Information & Management,41(1), 75– 86.

Wong, K. Y. (2005). Critical success factors for implementing knowledge management and small and medium enterprises.Industrial Management & Data Systems,105, 261–279.

Zhang, F., Zhao, J. L., Zhou, L., & Nunamaker, J. (2004). Can e-learning re-place traditional classroom learning: Evidence and implications of the evolving e-learning technology.Communications of the ACM, 47(5), 75–79.

Zmud, R. W., & Boynton, A. C. (1991). Survey measures and instruments in MIS: Inventory and appraisal. In K. Kraemer (Ed.),The information sys-tems research challenge: Survey research methods(pp. 149–180). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.