Konstrukcija seksualnega nadlegovanja v ameriških internetnih tabloidih in resnih časopisih: primerjalna študija

Teks penuh

(2) University of Maribor Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies. MAGISTRSKO DELO KONSTRUKCIJA SEKSUALNEGA NADLEGOVANJA V AMERIŠKIH INTERNETNIH TABLOIDIH IN RESNIH ČASOPISIH: PRIMERJALNA ŠTUDIJA. MASTER'S THESIS THE CONSTRUCTION OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT IN AMERICAN ONLINE TABLOIDS AND QUALITY NEWSPAPERS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY. Jasmina Odorčić. Mentor: doc. dr. Katja Plemenitaš. Maribor, 2018.

(3) Lektorica povzetka: Helena Korat, prof. slovenskega jezika in književnosti.

(4) Special thanks to my mentor, doc. dr. Katja Plemenitaš, for her valuable advice and professional guidance. I very much appreciate my family's and friends' support and love. I'm extremely grateful to Benjamin for his unconditional belief in me, and for his inexhaustible optimism..

(5)

(6) POVZETEK Magistrska naloga obravnava deset člankov na temo spolnega nadlegovanja, vzetih iz ameriških spletnih tabloidov (5) in resnih časopisov (5). Dolžina člankov je omejena na okoli 700 besed. Članki so analizirani s pomočjo diskurzne analize – jezikovne veje, ki diskurz obravnava z ozirom na družbeni kontekst. Jezikoslovec Michael Halliday (Halliday 2004, 29) je razvil teorijo treh metafunkcij jezika, ki so prisotne v določenem družbenem okviru. Študija, predstavljena v magistrski nalogi, je osredotočena na ideacijsko funkcijo/nalogo jezika, ki razkriva, kako ljudje s pomočjo jezika oblikujemo ideje in koncepte o različnih področjih naših izkustev (Martin in Rose 2007, 73). Poleg ideacijske funkcije magistrska naloga obravnava tudi interpersonalno (medosebno) funkcijo, še posebej to, kako so ovrednoteni ljudje in njihova čustva. Tretja, besedilna, metafunkcija jezika na tem mestu ni podrobneje obravnavana. Na primeru diskurza o spolnem nadlegovanju je obravnavana taksonomija dveh vrst udeležencev diskurza, in sicer žrtve ter storilca spolnega nadlegovanja. Pozornost je namenjena različnim ubeseditvam samega dejanja spolnega nadlegovanja. Prav tako nas je zanimalo, v kolikšni meri, če sploh, avtor besedil dopušča spregovoriti ostalim udeležencem diskurza (heteroglosija). V prvem delu je bila uporabljena deskriptivna metoda za teoretično predstavitev že obstoječih spoznanj s področja sistemske funkcijske slovnice in diskurzne analize. Manjši del je posvečen tudi sociološkemu vidiku spolnega nadlegovanja. Teoretična znanja o diskurzni analizi se naslanjajo na monografijo J. R. Martina in Davida Rosa z naslovom Obravnavanje diskurza: Pomen onstran stavka (Working with Discourse: Meaning beyond the clause) (2007) in na monografijo avtorjev J. R. Martina in P. R. R. Whita z naslovom Jezik vrednotenja: vrednotenja v angleškem jeziku (The Language of Evaluation: Appraisals in English) (2005). Tema spolnega nadlegovanja je v času pisanja te magistrske naloge še posebej aktualna v ameriških medijih. Na dan prihaja vse več osebnih izpovedi žensk in moških, ki so na delovnem mestu ali drugod doživeli neprijetno izkušnjo spolnega nadlegovanja. Odmevne so predvsem zgodbe slavnih – televizijskih napovedovalcev in napovedovalk ter hollywoodskih igralcev in igralk. Spolnega nadlegovanja so prav tako obtožene.

(7) slavne osebnosti, na primer Harvey Weinstein, Charlie Rose, Kevin Spacey, George H. W. Bush in drugi. Ob tem se poraja vprašanje, kako mediji, ki objavljajo tovrstne zgodbe, ustvarjajo diskurz o spolnem nadlegovanju, ki posledično vpliva na mišljenje bralcev in družbe na splošno. Da bi odgovorili na to vprašanje, je bilo 10 člankov iz ameriških spletnih tabloidov in resnih časopisov podrobneje obravnavanih z metodo diskurzne analize. V središču zanimanja so bile različne jezikovne izbire in reference, ki se nanašajo na žrtev in storilca spolnega nadlegovanja. Poleg tega je bila pozornost namenjena tudi vrstam spolnega nadlegovanja, ki se omenjajo v izbranih besedilih. Študija je zajela tudi področje večglasja znotraj obravnavanih besedil, ga kategorizirala in poskušala odgovoriti na vprašanje, ali avtorji izbranih besedil dopuščajo spregovoriti tudi ostalim glasovom in ali imajo v mislih tudi bralce ter njihova pričakovanja. Kot orodje pri označevanju, seštevanju in statistiki uporabljenih izrazov je bil v pomoč računalniški program CATMA. Program je prihranil ročno delo štetja in podčrtavanja besed in besednih zvez, kar je prispevalo k večji točnosti dobljenih rezultatov. V ospredju magistrske naloge je komparativna metoda, saj sta primerjani dve vrsti časopisov, in sicer tabloidi ter resni časopisi. Ugotovljene so bile razlike in podobnosti, na podlagi katerih smo iskali razloge za njihovo pojavitev. Predpostavljeno je bilo, da v izbranih besedilih poleg avtorjevega glasu nastopijo tudi drugi glasovi. Analiza je pokazala, da ta predpostavka drži. Avtorji v diskurz o spolnem nadlegovanju vključujejo predvsem glas žrtve, kar velja za obe vrsti časopisov. Storilci spolnega nadlegovanja v besedilih le redko dobijo besedo. Predpostavljeno je bilo tudi, da je stopnja modalnosti pri posredovanju informacij višja v tabloidih kot v resnih časopisih. Avtorji resnih časopisov naj bi bili bolj previdni glede tega, da informacijo posredujejo kot dejstvo, zato naj bi bila stopnja modalnosti nižja. Nasprotno pa je bilo predpostavljeno za tabloide. Analiza je pokazala, da je visoka stopnja modalnosti le redko izražena v obeh vrstah časopisov, več pa je primerov, ko je izražena nižja stopnja modalnosti. Sklepamo lahko, da so avtorji izbranih člankov tabloidov in resnih časopisov previdni ter informacij večinoma ne posredujejo kot absolutno resnico. Ugotavljali smo tudi, s katerimi leksikalnimi izbirami se besedilo nanaša na žrtve in.

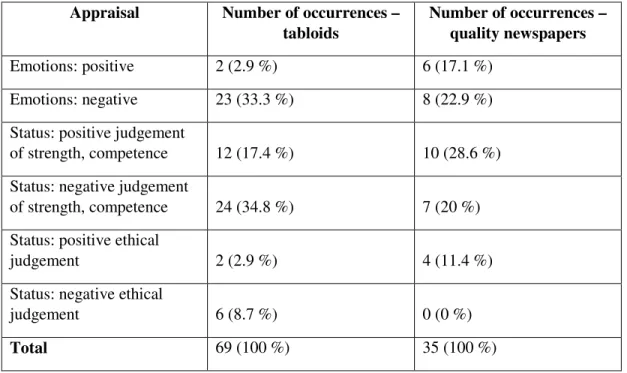

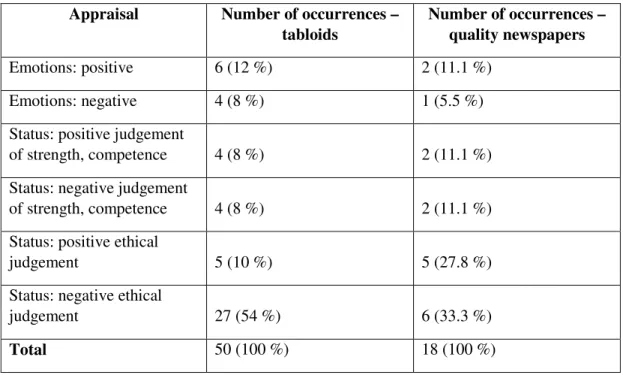

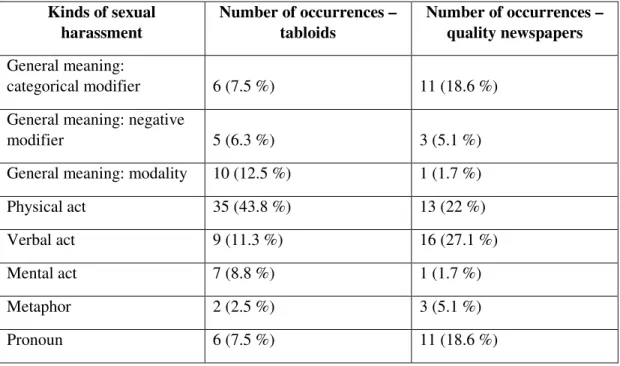

(8) storilce spolnega nadlegovanja. Predpostavljeno je bilo, da je znotraj vseh besedil več referenc na žrtev kot na storilca, kar je bilo z analizo tudi potrjeno. Žrtve so v tabloidih in v resnih časopisih predstavljene kot skupina žensk, pri čemer je v ospredju njihovo število (npr. Še šest žensk je Rogerja Ailesa obsodilo spolnega nadlegovanja.). Storilci v besedilih izstopajo tako, da se njihovo osebno ime nenehno ponavlja. V analizo so bila zajeta tudi poimenovanja telesnih delov, ki se največkrat pojavljajo v povezavi z žrtvijo in storilcem. Pri storilcih je največkrat omenjen telesni del roka, pri žrtvah pa noge in zadnjica. Predpostavljeno je bilo, da bodo storilci v tabloidih bolj negativno ovrednoteni kot žrtve. Rezultati so pokazali, da so tudi žrtve negativno ovrednotene zaradi svojih šibkosti in nesposobnosti. Po drugi strani pa so v izbranih tabloidih negativno ovrednoteni tudi storilci spolnega nadlegovanja, vendar zaradi svojega neetičnega vedenja. Pozornost je bila namenjena tudi vrstam spolnega nadlegovanja, ki se v izbranih besedilih najpogosteje pojavljajo. V tabloidih je to fizično spolno nadlegovanje, v resnih časopisih pa besedno. Tudi sicer tabloidi veliko bolj izpostavljajo fizično plat spolnega nadlegovanja, kar lahko pripišemo težnji po senzacionalnosti. Raziskava, izvedena v sklopu te magistrske naloge, ima tudi svoje omejitve. Analizirati bi bilo potrebno veliko več besedil, da bi lahko bila predstavljena realna slika konstrukcije spolnega nadlegovanja v ameriških resnih časopisih in tabloidih. Prav tako bi bilo dobro v analizo vključiti še druge metode diskurzne analize (na primer analizo nuklearnih razmerij ali podrobnejšo analizo modalnosti). Cilj te magistrske naloge je bil med drugim tudi dokazati, da lahko z metodami diskurzne analize postanemo bolj kritični udeleženci diskurzne skupnosti, ki ji pripadamo.. Ključne besede: diskurzna analiza, spolno nadlegovanje, žrtev, storilec, heteroglosija, tabloidi, resni časopisi..

(9) ABSTRACT This master’s thesis deals with the construction of sexual harassment in American online tabloids and quality newspapers. Ten texts of relatively the same length, 5 articles from tabloids and 5 articles from quality newspapers, have been selected for analysis, which was based on the methods of discourse analysis. The thesis deals with ideational and interpersonal metafunctions of language in the selected texts. In connection with this, the thesis examines how victims and perpetrators of sexual harassment are described and classified, and which kinds of sexual harassment are mentioned in the texts. This master’s thesis also analyzed external voices included in the texts (heteroglossia). Findings from tabloids have been compared with findings from quality newspapers. The results have shown that perpetrators were judged negatively for their harassment in both kinds of newspapers, while victims were judged for their lack of strength and competence. As expected, victims were referred to more frequently than perpetrators. Physical harassment was the center of focus in tabloids, while in quality newspapers the reference to verbal harassment was made more often.. Key words: discourse analysis, sexual harassment, victim, perpetrator, heteroglossia, tabloids, quality newspapers..

(10) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1. 2. METHODS ........................................................................................................... 2. 3. TEXTS FOR ANALYSIS.................................................................................... 2. 4. SYSTEMIC FUNCTIONAL LINGUISTICS (SFL) ........................................ 4. 5. DISCOURSE ANALYSIS ................................................................................... 7 5.1. NEGOTIATING ATTITUDES ........................................................................... 10. 5.1.1. Affect .............................................................................................................. 10. 5.1.2. Judgement ....................................................................................................... 11. 5.1.3. Appreciation .................................................................................................... 12. 5.1.4. Heteroglossia or engagement .......................................................................... 12. 5.1.5. Graduation....................................................................................................... 14. 5.2. IDEATION ............................................................................................................ 14. 5.2.1. Taxonomic relations........................................................................................ 15. 5.2.2. Nuclear relations ............................................................................................. 16. 5.2.3. Activity sequences .......................................................................................... 17. 5.3. TRACKING PARTICIPANTS ............................................................................ 17. 5.3.1. Resources for identifying people .................................................................... 18. 5.3.1.1. Presenting reference (introducing people) .................................................. 18. 5.3.1.2. Presuming reference (tracking people) ....................................................... 18. 5.3.2. Resources for identifying things ..................................................................... 19. 5.4. POWER AND IDEOLOGY IN THE LIGHT OF LANGUAGE ..................... 19. 5.5. GENRE .................................................................................................................. 20. 5.6. NEWSPAPER STORY AS A MASS MEDIA DISCOURSE ............................ 21. 5.7. REGISTER OF THE SELECTED TEXTS........................................................ 23. 5.7.1. The field of sexual harassment........................................................................ 24. 5.7.1.1 5.7.2. 6. Sexual harassment in the workplace: the US context ................................. 24 Mode and tenor ............................................................................................... 26. DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE SELECTED NEWSPAPER STORIES …………………………………………………………………………………. 29 6.1. The tool for computer-assisted analysis CATMA .............................................. 29. i.

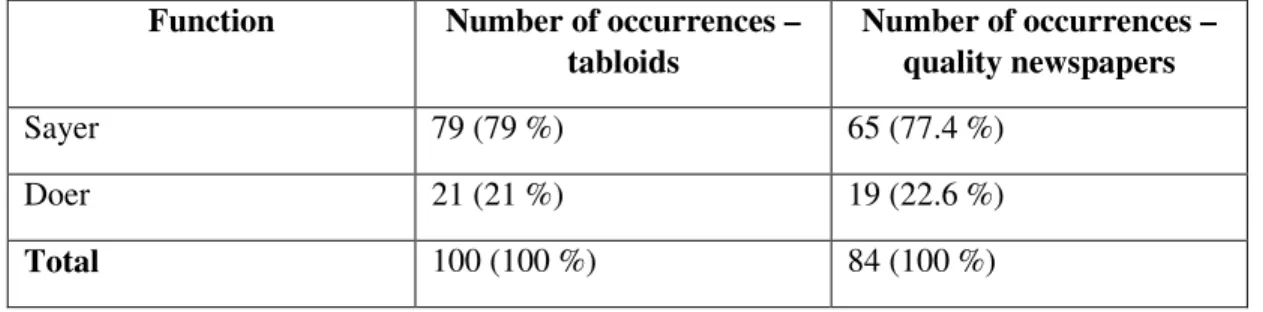

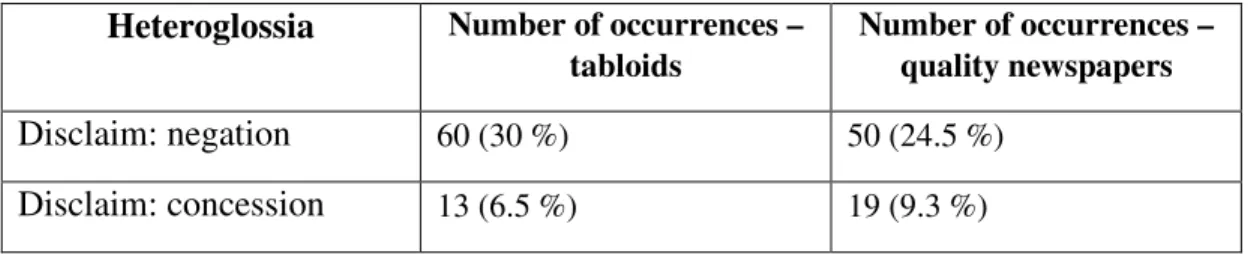

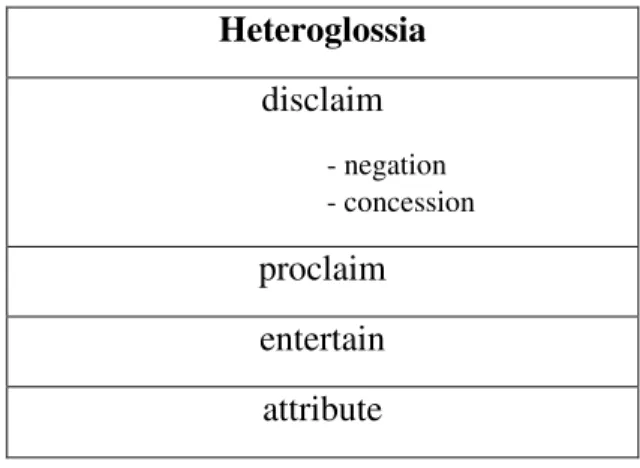

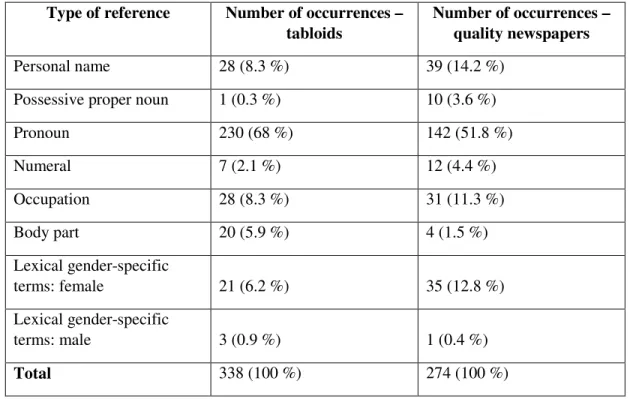

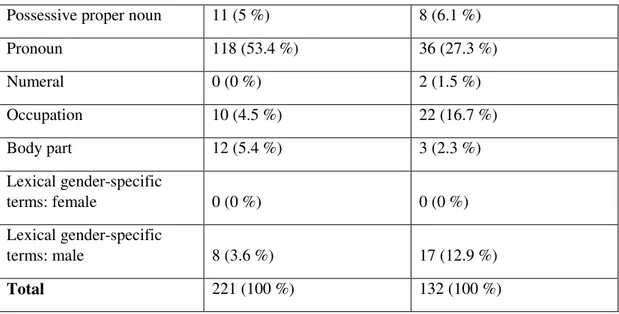

(11) 6.1.1 6.2. Shortcomings of the CATMA software .......................................................... 33 RESULTS .............................................................................................................. 33. 6.2.1. Results: Participants – Type of Reference ...................................................... 34. 6.2.2. Results: Participants – Function ...................................................................... 36. 6.2.3. Results: Participants – Appraisal .................................................................... 37. 6.2.4. Results: Kinds of Sexual Harassment ............................................................. 39. 6.2.5. Results: Heteroglossia ..................................................................................... 40. 6.3. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS .............................................................................. 41. 6.3.1. Pronouns and personal names ......................................................................... 41. 6.3.2. Possessive proper nouns.................................................................................. 42. 6.3.3. Numerals ......................................................................................................... 42. 6.3.4. Occupation ...................................................................................................... 43. 6.3.5. Body part ......................................................................................................... 43. 6.3.6. Lexical gender-specific term ........................................................................... 43. 6.3.7. Function: sayer and doer ................................................................................. 44. 6.3.8. Appraisal ......................................................................................................... 45. 6.3.8.1. Feelings: positive or negative ..................................................................... 45. 6.3.8.2. Judgements of strength and competence ..................................................... 46. 6.3.8.3. Ethical judgements ...................................................................................... 47. 6.3.9. Kinds of sexual harassment............................................................................. 48. 6.3.10. Heteroglossia................................................................................................... 50. 6.4. HYPOTHESES ..................................................................................................... 56. 7. CONCLUSION .................................................................................................. 58. 8. BIBLIOGRAPHY .............................................................................................. 59 APPENDIX …………………………………………………………………… 62. ii.

(12) INDEX OF TABLES Table 1: Heteroglossia Tag Library ............................................................................ 30 Table 2: Ideation Tag Library – Participants .............................................................. 32 Table 3: Ideation Tag Library: Kinds of Sexual Harassment ..................................... 33 Table 4: Victims – Type of Reference ........................................................................ 34 Table 5: Perpetrators – Type of Reference ................................................................. 34 Table 6: Victims – Function........................................................................................ 36 Table 7: Perpetrators – Function ................................................................................. 36 Table 8: Victims – Appraisal ...................................................................................... 37 Table 9: Perpetrators – Appraisal ................................................................................ 37 Table 10: Kinds of Sexual Harassment ....................................................................... 39 Table 11: Heteroglossia............................................................................................... 40. iii.

(13) 1 INTRODUCTION In various media and social networks, a lot of attention has been given to the topic of sexual harassment over the last year. We can read about and listen to numerous traumatic sexual harassment stories, from both women and men. Accounts of celebrities, including actors and actresses, TV/radio presenters, models, and writers, are receiving special attention and popularity in online media. People accused of sexual misconduct are often well-known personalities themselves, for example Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, Charlie Rose, George H. W. Bush, and so on. In October 2017 the #Me Too movement was created on social media to encourage victims of sexual harassment to use it and thus reveal how pervasive the problem of sexual harassment is in our society. Accounts on sexual harassment have been widely covered in various media, and victims have often been praised for courage they had for coming forward. The question is how is sexual harassment presented within a discourse community and how does such a presentation shape people’s opinion on the topic? These questions are too broad for one master’s thesis, therefore, I narrowed my research to ten American online newspaper stories, five from tabloids and five from quality newspapers, all written in English. I anticipated to find important differences in the construction of sexual harassment in tabloids and quality newspapers. For this master’s thesis the following hypotheses were set: 1) Apart from authorial, other voices are introduced into the discourse on sexual harassment, especially the voice of the victim. 2) In tabloids, the degree of modality is higher when negotiating information. 3) There are more references to the victim than to the perpetrator in the selected texts. 4) In tabloids, perpetrators are appraised more negatively than victims.. 1.

(14) 5) Physical sexual harassment is the most frequently mentioned kind of sexual harassment, both in tabloids and in quality newspapers.. 2 METHODS In the theoretical part of this master’s thesis, a descriptive method is used. Here, the theory of discourse analysis is presented and a short overview on systemic functional linguistics is made. Linguistic terms which are part of discourse analysis are explained in this part. A short sociological view on sexual harassment in the workplace is included in this part as well. In addition to the descriptive method, an analytical method is used for applying discourse analysis to the selected texts in the second part of this master’s thesis. Heteroglossia and relations between lexical elements are the central focus of the analytical part. For underlining and categorizing examples from the texts, I used a computer tool CATMA (Computer Assisted Text Markup and Analysis). Comparative method is used to examine differences in the construction of sexual harassment between tabloids and quality newspapers. Comparisons between victims and perpetrators are made as well.. 3 TEXTS FOR ANALYSIS The theoretical basis for the analysis of the selected texts is presented by J. R. Martin and David Rose in their monography Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause (2007). For marking and analysis of the texts the analytic online program CATMA was used. The texts for analysis were selected from American online newspapers. The language of the texts is English. Five texts were selected from American online tabloids and five 2.

(15) from American online quality newspapers. Their main theme is sexual harassment. They are all of approximately the same length (700 words or five minutes of reading). The dates of their publication range from October 2017 to November 2017, with an exception of one text that dates July 2016. The texts are included in the Appendix. From online tabloids the following titles were selected for analysis:. -. Chris Perez, “House of Cards' crew accuse Spacey of sexual harassment,” New York Post (Page Six), November 2, 2017;. -. Jackie Willis, “TV reporter Lauren Sivan claims Harvey Weinstein sexually harassed her in 2007,” Entertainment Online, October 9, 2017;. -. Kaiser, “Woman accuses Harvey Weinstein of assaulting her while she was on her period,” Celebitchy, October 25, 2017;. -. “Charlie Rose accused of multiple 'unwanted sexual advances',” Radar Online, November 20, 2017;. -. “Jesse Jackson & John Singleton accused of sexual harassment by journalist,” Perez Hilton, November 7, 2017.. From online quality newspapers the following titles were selected for analysis:. -. Cara Kelly, “Gretchen Carlson takes on the 'shocking epidemic' of sexual harassment in new book,” USA Today, October 17, 2017;. -. Erica Werner and Juliet Linderman, “Congressional leaders call for sexual harassment training,” The Denver Post, November 5, 2017;. -. Jonah Engel Bromwich and Matt Stevens, “George H. W. Bush Apologizes After Women Accuse Him of Grabbing Them,” The New York Times, October 27, 2017;. -. Kyle Swenson, “Putin associate sides with Harvey Weinstein and says America is too uptight,” Boston Globe, November 7, 2017;. 3.

(16) -. Stephen Battaglio, “Six more women come forward alleging sexual harassment by Fox News CEO Roger Ailes,” Los Angeles Times, July 9, 2016.. While selecting texts for analysis in November 2017, I encountered a lack of diversity since the majority of online newspaper stories wrote about accusations against Harvey Weinstein. Additionally, it was also hard to find texts of roughly the same length. Short texts with sensational content are usually published in tabloids. In quality newspapers the length of a newspaper story is normally longer when compared to tabloids. In order to compare results of the analysis from tabloids and quality newspapers more objectively, the length of the texts had to be approximately the same.. 4 SYSTEMIC FUNCTIONAL LINGUISTICS (SFL) Systemic Functional Linguistics or SFL is a functional approach to language mainly developed by British linguist Michael Halliday (Eggins 2005, 1–2). At present many languages besides English are taking part in the further development of SFL, for example Chinese, Danish, French, German, Indonesian, Japanese, Spanish etc. (Matthiessen, Teruya and Lam 2010: xi). Studies of SFL in various languages around the world build up an overall picture of SFL, and what is common to all of them is a shared interest in language used in our everyday interactions with other people. SFL, therefore, assigns great significance to the “social nature of language” and to language use in context (Plemenitaš 2007, 14). Systemic linguists assert that “language use is functional” and “its function is to make meanings” which are affected by society and culture (i.e. context). “The process of using language is a semiotic process, a process of making meaning by choosing” (Eggins 2004, 3). It follows that language use is “functional, semantic, contextual and semiotic” (Eggins 2004, 3), which means that the approach under consideration can be described as a functional-semantic approach to language.. 4.

(17) SFL is interested in functional questions about language, for example How do we use language? What do we do with it? and How is language structured for use? In addition to functional questions, systemicists ask semantic questions as well: How is language organized to make meanings? or How many different kinds of meaning do we use in language in order to create meanings? To answer these questions, systemicists study real discourses (spoken or written) that were produced by people in their social contexts (Eggins 2004, 3–4). When we use language we do it with a certain purpose in mind that we want to accomplish. Functional linguists state that every use of language “is motivated by a purpose”, some of which are more pragmatic in their nature while others are more interpersonal (motivation letter vs. conversation with a friend) (Eggins 2004, 5). While observing a text, we cannot isolate one sentence from the rest, but rather we should study it as a whole. The task of defining the author’s purpose only on the basis of one isolated sentence, is complicated if not impossible. The functional-semantic approach to language defines spoken or written text as “a complete linguistic interaction” (Eggins 2004, 5) from the beginning of a linguistic event to its end. Halliday and Hasan (1976) outline a text as “language functioning in context” (cited in Martin et al 2010, 218). A text can considerably vary in its length and nature and cannot be separated from its context. The term context includes field, tenor and mode of a text alongside with a situational context (Martin et al 2010, 77). As literate readers or listeners we are capable of recognizing patterns of meaning in a text and relatively easily presupposing its context. A sentence separated from the whole is ambiguous in meaning and it does not provide sufficient information about writer’s or speaker’s purpose. Additionally, we are able to foresee what kind of language is suitable in a particular context. All of this is evidence in favor of a conclusion that language and context must not be separated from one another (Eggins 2004, 9). SFL makes an important premise that how we choose to express ourselves with language is inevitably affected by our ideology. Language is encoded with positions and values of its users. Suzanne Eggins states straightforwardly that “for reasons which 5.

(18) are themselves ideological, most language users have not been educated to identify ideology in text, but rather to read texts as natural, inevitable representations of reality” (Eggins 2004, 10–11). The main reason why we use language in our interactions is to create meaning with other people, therefore, it can be said that the general purpose of language use is a semantic one. Texts that interactants participate in create not just one meaning, but a number of them at the same time. Halliday explains that language is structured in a way that three kinds of meaning are made at the same time: ideational, interpersonal and textual. Ideational meaning is concerned with how we portray experience in language: what kind of activities are undertaken, how are participants that engage in these activities described and classified. Interpersonal meaning of language is concerned with negotiating social relations, which includes different ways people interact with each other, but also their attitudes about other people and things (Martin and White 2005, 7). The third meaning that a text makes is called textual meaning. It is concerned with spoken or written text’s organization. For instance, a text can be organized around people or abstractions or around any other information. Textual meanings are about how interpersonal and ideational metafunctions are weaved together in order to create a meaningful text that relates to the context (Eggins 2004, 12). That these three kinds of meaning can be realized at the same time is only possible because “language is a semiotic system, a conventionalized coding system, organized as sets of choices” (Eggins 2004, 3). If we consider language as a semiotic system, we regard it as a resource from which we choose building blocks in order to make meanings in context (Martin 1992, cited in Plemenitaš 2007, 14). A sign, including a linguistic sign, is made of meaning (content) and realization (expression), and is a part of a semiotic system which contains a limited number of discrete signs (Eggins 2004, 14). An interesting observation about language as a semiotic system is that we can use it to talk about other semiotic systems (e.g. semiotic systems of colors or fashion), but not the other way around.. 6.

(19) Systemicists claim that language as a semiotic system is made of three levels or strata. Language has two levels of meaning-making: “an upper level of content” (semantics, first level) and “an intermediate level of content known as lexico-grammar” (second level) (Eggins 2004, 19). Meanings are realized through words used (wording) which are realized as sounds or letters (expression, third level). In technical terms semantics is realized through the lexico-grammar which is realized through phonology or graphology. Systemic linguists do not label linguistic choices of language users as right or wrong but rather as appropriate or inappropriate considering the specific context in which these choices were made (Eggins 2004, 20).. 5 DISCOURSE ANALYSIS Discourse analysis is a branch of linguistics that is interested in studying language use in a social context. In the case of this master’s thesis, the language under consideration is English. Discourse analysis came to life in the 1960s and 1970s, when it developed out of different disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, anthropology, sociology etc. Its subjects of interest are complex and simple, written and spoken texts. The first one to use the term discourse analysis was Zellig Harris who in 1952 published an article called Discourse analysis. At that time, linguists were occupied with analysis of single sentences. Contrary to them, Harris was more curious about how linguistic elements were distributed throughout a piece of text, and about connections between texts and culture (McCarthy 1991, 5). Van Dijk argues that discourse analysis has some of its roots in classical rhetoric. He points out rhetoricians like Aristotle who emphasized powerful effects that different structures of discourse have in persuading an audience (van Dijk 1988, 18). McCarthy lists some early milestones that had a significant impact on the evolution of discourse analysis: emergence of semiotics, structuralism, pragmatics, and diverse studies of scholars (Hymes, Austin, Searle, Grice) that took into consideration social context in their otherwise linguistic research. M. A. K. Halliday with his “functional. 7.

(20) approach to language” however had the greatest impact on discourse analysis in Britain (McCarthy 1991, 6). American type of discourse analysis has put an emphasis on close observation of groups of people that communicate with each other in as natural a setting as possible. It studies speech events in different social frameworks. Text grammarians, who predominantly work with written texts, have played a crucial role in the development of discourse analysis, as well. Grammar is, according to Martin and Rose (2007, 4), one of the three main strata of discourse analysis, alongside with discourse and social context. Grammatical tools provide analysts with an understanding of the roles of wordings in different parts of a text, while social theory helps them interpret the meaning of the text in a social context. Therefore, in discourse analysis approach to a text knowledge of grammar and social theory is crucial. To emphasize how indispensable grammar within a field of discourse analysis is, Halliday writes: It is sometimes assumed that (discourse analysis or ‘text linguistics’) can be carried on without grammar – or even that it is somehow an alternative to grammar. But this is an illusion. A discourse analysis that is not based on grammar is not an analysis at all, but is simply a running commentary on a text. (Cited in Eggins 2004, 20). Some of the great names of linguists that have a strong impact on this area are De Beaugrande, Halliday, Hasan and van Dijk. With its studies of connections between grammar and discourse, The Prague School of linguists also left a footprint in the development of discourse analysis. Although discourse analysis is far from being a homogenous discipline, two things stand out and unite all of its approaches. Firstly, an interest in studying language within a social context; and secondly, paying attention to meaning beyond the clause (McCarthy 1991, 6–7). Slovenian linguists that have contributed to the recognition and development of SFL in the Slovene area are Janez Dular, Tomo Korošec, Irena Kovačič, Mira Kranjc Ivič, Olga Kunst Gnamuš, Katja Plemenitaš, Andrej E. Skubic, Branka Vičar, Agata Križan, Monika Kavalir, and others.. 8.

(21) As mentioned above, discourse analysis interpretation of a certain text needs to consider its social context. Martin and Rose claim that “each interaction is an instance of the speakers’ culture”, therefore, the text under consideration can aid an analyst in interpretation of aspects of the culture it exhibits (Martin and Rose 2007, 1). The authors’ main point is, however, that a clause, a text and a culture are more than just things; they are “social processes, unfold[ing] at different time scales” (2007, 1–2). Discourse analysists are concerned with spoken and written interactions. One of the models proposed for an analysis of verbal discourse is the Birmingham model, which deals with interactions in classrooms (Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975). Simple verbal discourses are easily predictable (for example greeting our neighbors, doctor-patient talk etc.), while some can be more intricate, for example political debates. The nature of either spoken or written discourse is interactive (Martin and Rose 2007, 26), since discourse is never just a text, but also an interaction (van Dijk 1988, 29). In written texts, sentences are usually more carefully formed as opposed to spontaneous spoken texts. A writer has more time to contemplate how he wants to communicate his message, which results in well-formed sentences. When we observe properties of a written text, we need to consider its cohesion and coherence. Cohesive markers are “links between the clauses and sentences of a text” (McCarthy 1991, 25), and thus connect related elements. These links are realized in forms of grammatical (ellipsis, conjunction etc.) or lexical features (synonym, lexical repetition etc.). Cohesive items are but clues and not absolutes in indicating how a text should be read. Cohesion is a part of coherence, which creates an impression of meaningfulness of the text. Coherence is created by a reader in the process of reading, and also by a listener in the process of listening to a verbal text (McCarthy 1991, 26). Discourse analysis attributes a great role in building a text’s world to the reader, who is actively involved in interpretation of the text. How the reader understands the text depends on his or her previous knowledge about the world (McCarthy 1991, 27—28). This is called a cognitive dimension of discourse which alongside with interpretation includes the formulation of the text (van Dijk 1988, 29).. 9.

(22) Martin and Rose (2007) propose six different discourse systems consisting of sets of meaning: negotiating attitudes, enacting exchanges, representing experience, connecting events, tracking people and things, and information flow. I will not be using the full set of analytical tools since such analysis would considerably broaden the scope of my research. From these six discourse systems, the analysis presented in this theses examines the systems for negotiating attitudes, representing experience and tracking people and things.. 5.1 NEGOTIATING ATTITUDES The system of appraisals deals with evaluation of people, feelings, things and even abstractions such as qualities of life or relationships. Three main types of attitudes are affect, judgement and appreciation, which are generally referred to as emotion, ethics and aesthetics respectively (Martin and White 2005, 42). A linguistic resource for determining who the evaluations are coming from is called engagement, or if put in Halliday’s terminology projection. Our attitudes can be amplified which means they are gradable; this domain of appraisal is called graduation (Martin and Rose 2007, 25). The focus of an appraisal system is therefore on interpersonal meaning and can be applied both to written and spoken texts (Martin and White 2005, 7). Appraisal is a component of discourse semantics which focuses on the meaning of a text as a whole, and not just on a single clause taken out of context. Likewise, attitudes are not limited to one clause only, but can be found across the whole text. An attitude can be realized through different grammatical categories, for example through verbs, adjectives, adverbs and so on (Martin and White 2002, 7–9). 5.1.1. Affect. Normally people tend to express their feelings in different ways. Emotional expression can be divided broadly into groups of good or bad feelings, therefore, affect can be either positive or negative. We can also express how we feel in a straightforward manner, or we can indicate our emotions more indirectly, for example by the way we 10.

(23) behave. In such a case affect is expressed either directly or it is only implied. Emotional states (happy, sad, ecstatic) and physical expressions (shake with terror) are directly expressed feelings, while extraordinary behavior (sleeping days and nights) and metaphorical expressions (He’s been treated with cool indifference) are indirectly expressed feelings. Emotions can be realized by behavioral (He was crying), emotional (He was sad) and relational (He felt unhappy around his father) processes. (Martin and Rose 2007, 29–32). Furthermore, people’s emotions can be grouped into “three major sets having to do with un/happiness, in/security and dis/satisfaction” (Martin and White 2005, 49). The first and most common set of emotions includes ‘affairs of the heart’ which are happiness, sadness, hate and love. The next variable covers emotions concerned with “ecosocial well-being” (anxiety, confidence, fear and trust). The third set involves feelings associated with our achievements, learning and dissatisfaction with activities undertaken as participants or as observers; these feelings are ennui, displeasure, curiosity and respect (Martin and White 2005, 49–50). Some genres are more saturated with emotions (e.g. stories), while others are almost entirely void of them (e.g. scientific articles). 5.1.2. Judgement. The term judgement here signifies our positive (what we admire) or negative (what we criticize) judgements about people’s characters. We may judge them explicitly or implicitly, personally (admiration and criticism) or morally (praise and condemnation) (Martin and Rose 2007, 32–34). Judgements can be arranged into two general groups: judgements dealing with social esteem (normality, capacity and tenacity of the person being judged), and those dealing with social sanction (veracity and propriety of a person being judged). Rules of social esteem are not written down, but are controlled by friends, family etc. who share the same values. They live on through stories, gossip, jokes and so on. On the other hand, social sanction is written down by a state or church as a set of rules, laws and. 11.

(24) regulations that must be obeyed. A certain lexical item may vary its attitudinal meaning, therefore, it is essential that we read the text in its context (Martin and White 2005, 52). 5.1.3. Appreciation. Appreciation deals with our positive or negative attitudes about things, including our performances (festivals, plays, concerts), things we make (houses, parks, books, paintings) and nature (forests, mountains, constellations). Although relationships and qualities of people or things are abstract, they can be assessed as if they themselves are objects (Martin and Rose 2007, 37 & Martin and White 2005, 56). Appreciation can be divided into three main sets: our reaction to things (do they attract our attention and are we pleased with them?), their composition (“balance and complexity”) and their value (how original, creative, interesting or valuable they are). Our attitude about the value of things highly depends on the focus of our interest and on our opinion on the subject matter (Martin and White 2005, 56–57). Martin and White suggest that there is a link between an attitude of affect and the reaction variable of appreciation. They find it appropriate to distinguish between someone’s feelings and the power of a thing that triggers such feelings. In a like manner, a negative or positive evaluation of a thing (for example a thorough building plan) may resemble a positive or negative judgement of someone who is capable of certain behavior or performance (for example an excellent architect), but they are likewise distinguished from one another (Martin and White 2005, 57–58). 5.1.4. Heteroglossia or engagement. Engagement is a part of a larger system of negotiating attitudes (interpersonal metafunction of language). It is used for introducing additional voices in a text, and determining from who the evaluations in a text are coming. If there is more than one voice or source of attitude in the text, the term we use to describe it is heterogloss. In instances where there is only one voice (the author’s), the term is monogloss. An author. 12.

(25) of a newspaper story, for example, explicitly gives voice to other people by quoting or reporting what they said. Halliday and Matthiessen (2004, 508) call such a linguistic resource projection. Projecting clauses can include both, quoting someone verbatim, which in writing requires the use of speech marks, or reporting the main point of what had been said, which normally omits speech marks. We can as well quote or report what we feel, think, wish or know. Projections can also be found within clauses, where opinions are ascribed to a specific source. Words used in such instances are for example “saying,” “seeing,” and “feeling” (Martin and Rose 2007, 48–52). In addition to projecting clauses and projecting within clauses there are two more projecting sources: names for speech acts (story, extract, lines etc.), and scare quotes where punctuation signifies that the words come from another source (“famous”, “those at the top”, “feel comfortable” etc.). In addition to projection, modality is another tool for introducing additional voices into the text. According to Halliday, modality “sets up a semantic space between yes and no, a cline running between positive and negative poles” (in Martin and Rose 2007, 53). With modality we can negotiate services or information. On the scale of negotiating services we can determine how obliged is one to act (for example: do it you must do it you should do it you could do it don’t do it); and on the scale of negotiating information we can say how probable a statement is (for example: it is it must be it should be it might be it isn’t). In each case there is a choice of negative or positive polarity. Positive polarity invokes only one voice whereas negative polarity implies two, because negation puts one’s voice in relation to a possible voice of an opposing participant (Martin and Rose 2007, 53–54). When a writer of a text acknowledges different voices in addition to his or her own, we call it counterexpectancy or concession. The writer often creates an expectation in his or her readers, but later he or she may counter it thus acknowledging additional voices. In the case of concession, concessive conjunctions are used, such as but, however, although, even if, even by, in fact, at least, indeed, nevertheless, needless to say, of course, admittedly, in any case etc. In addition to conjunctions, a writer can use. 13.

(26) continuatives for adjusting readers’ expectations. The difference between conjunctions and continuatives is that the former occur at the beginning of a clause, while the latter occur inside it. Continuatives include the following words: already, finally, still, only, just and even. Time continuatives point out that something happened sooner or later than the reader might have expected. Continuatives also indicate that “there is more or less to a situation than has been implied” (conjunctions such as even and only) (Martin and Rose 2007, 56–58). 5.1.5. Graduation. Attitudes can be amplified with the help of linguistic resources for altering how strongly we feel about people and things. Martin and Rose (2007) point out two options for amplification: force and focus. Words that increase the force of attitudes are intensifiers (for example: very, extremely, really, quite), and we use them for to compare things, people, situations and so on (best, better, good, bad, worse) (Martin and Rose 2007, 42–46). The second resource of graduation is sharpening and softening focus. The dimension of focus makes something that usually is not gradable, gradable. We can sharpen or soften categories of things/people (e.g. a real policeman vs. kind of a policeman), types of qualities (e.g. deep blue vs. bluish) and numbers (e.g. after about four years vs. after exactly four years) (Martin and Rose 2007, 46–48). In this MA thesis the model of graduation was not applied.. 5.2 IDEATION Ideation deals with the formation of ideas and concepts. It is concerned with the way our experience is construed in discourse. In the center of its attention are activities that are undertaken and how the participants (people and things) undertaking these activities are described and classified. In addition to that, it focuses on places and qualities associated with people, things and activities.. 14.

(27) David and Rose discuss three systems of ideation – taxonomic relations, nuclear relations and activity sequences. The entire system of ideation is broadly speaking composed of lexical relations. These relations are “semantic relations between the particular people, things, processes, places and qualities that build the field of a text” (2007, 75). Text fields consist of people and things performing activities under certain circumstances. 5.2.1. Taxonomic relations. Taxonomic relations help an analyst to classify the participants of a text. Relations such as repetition, synonyms and contrast create a picture of people and things as the text unfolds. They also construct taxonomies of places and qualities. In our case, we track participants (perpetrators and victims) and observe how they are classified (explicitly or implicitly, generally or specifically) and which attributes are ascribed to them (positive or negative). The relation between one example of a class and the next is called co-class relation. These relations form strings of lexical relations throughout the text. Participants can be cross-classified by many various social categories, such as age, gender, ethnicity, capacity and social class. By observing these categories, we can build up a clearer picture of the social world represented in the text. Participants can be construed as organisms consisting of numerous parts. The relation between one such part and the other is referred to as co-part relation (Martin and Rose 2007, 76–80). David and Rose divide taxonomies into different types of lexical relations including class-member and co-class, whole-part and co-part. These types include repetition (repeating of the same lexical item), synonyms (a different lexical item, but a similar experiential meaning), and contrast. The latter includes oppositional relations between lexical items, namely antonyms (opposing meaning of two lexical items), and converse roles or converses (e. g. doctor – patient); and series, which are further divided into scales (e. g. excellent – good – average – poor – very poor) and cycles (e. g. months of a year). In the case of our genre of newspaper story, series are especially relevant for the interpretation of events and things. The reader reads a newspaper story similarly to every other story that jumps ahead and backward in time to create tension, and thus 15.

(28) attracts the reader’s attention. In genres where times are out of sequence, time cycles are a necessary lexical resource for making sense of the order of events (Martin and Rose 2007, 80–81). Taxonomic relations are significant for construing a field of experience as the reader progresses through the text. With each lexical item they create expectancy for the reader, or they counter it (Martin and Rose 2007, 81). Taxonomic relations are closely related to resources of appraisals, because we evaluate construed categories. It is also possible that categories do not include only people and qualities but abstractions, such as moral/immoral behaviors. 5.2.2. Nuclear relations. The next system of ideation is called nuclear relations. Because we did not apply the model of nuclear relations to the texts for analysis of this master’s thesis, the following passage is a condensed summary of concepts explained in Martin and Rose’s monography Working with Discourse (2007, 90–100). Nuclear relations deal with lexical relations between elements within a clause and are commonly known as collocations. In his works, Halliday (2004) describes different semantic patterns, of which the most important experiential pattern is “that people and things participate in a process” (in David and Rose 2007, 91). According to Halliday the main participant in the clause is known as Medium, through which “the process is actualized” (Halliday 2004, 336). In various texts we may come across more than one participant involved in the process. They are labeled as Agent, Beneficiary and Range. A third participant in the clause is known as Beneficiary. Both Agent and Beneficiary are of minor importance in terms of nuclear relations, therefore, they can be left out of the clause. Martin and Rose (2007, 93) state that because of common practice “relations between central and nuclear elements are predictable within the general field.” Within the nuclear system of ideation, there are also other nuclear relations, one of which is. 16.

(29) known as Range. It is “a second participant that is not affected by the process” (Martin and Rose 2007, 94). When observing the processes in clauses, we will sooner or later come across a variety of circumstances, including peripheral or outer circumstances (time, place and cause), and nuclear or inner circumstances (role, means, matter and accompaniment). Outer circumstances are peripherally associated with the activity of the clause. On the other hand, inner circumstances “are alternative ways of involving people and things involved in the activity” (Martin and Rose 2007, 95). 5.2.3. Activity sequences. The last system of ideation is activity sequences. Here the focus is on recurrent sequences of activities. Martin and Rose (2007, 101) define activity sequences as “series of events that are expected by a field.” It is not usual that texts provide continuous series of events, rather events are interspersed throughout the text. Our expectation is that activities within each phase are related – they can be parts of larger activities or they can be divided into smaller ones. For example, the activity of sexual harassment is part of a larger set of deviant behaviors, but at the same time this activity includes smaller components, such as inappropriate touching or making sexual remarks. Sometimes, processes can be challenging to recognize and analyze, because they are nominalized and thus they appear as things. In Halliday’s words this phenomenon is called a grammatical metaphor. To analyze activity sequences in such cases, we must convert them back to processes (Martin and Rose 2007, 106–107).. 5.3 TRACKING PARTICIPANTS To understand a text we are dealing with, we need “to be able to keep track of who or what is being talked about at any point” (Martin and Rose 2007, 156). Within discourse analysis, tracking participants is a part of textual metafunction of language. Martin and Rose divide participants into people and things. 17.

(30) 5.3.1. 5.3.1.1. Resources for identifying people. Presenting reference (introducing people). At the beginning of a discourse, people are introduced indefinitely, because it is assumed we do not know them. Indefinite determiners (a, an) and difference words (another) are used to introduce new people in the discourse. For example: “a former production assistant” and “another woman in the room”. When we can recognize an identity of people mentioned for the first time, a definite determiner (the) and personal names are used. For example: “the women” and “George H. W. Bush”. In English, there are instances in which people are already introduced, but are, nevertheless, described indefinitely. The main purpose for using such strategy is to classify and describe people, not to identify them. For example: “Reah Bravo, who started working for Rose as an intern before she became an associate producer for Rose […].”. 5.3.1.2. Presuming reference (tracking people). After having been introduced into the text, people are further referred to by personal names (Paul Ryan), possessive proper nouns (Ms. Staples’s), pronouns (she, he), possessive pronouns (her, his), definite determiner (the president), and as a kind of person (the kind of woman who would base her career on sexual favors). In many cases, authors use presuming reference, even though participants have not been introduced before. To avoid repetition, authors rely on the common knowledge of their audience, assuming that they already know something about those participant. As an example we can use an opening sentence of a newspaper story Woman accuses Harvey Weinstein of assaulting her while she was on her period: “Yesterday, a former production assistant named Mimi Haleyi came out and told her story about Harvey Weinstein.” 18.

(31) 5.3.2. Resources for identifying things. Under the category of things Martin and Rose (2007) include objects, institutions and abstractions. Considering identification, concrete objects are introduced and tracked like people: their introduction is indefinite (a, an), after which they are tracked with determiners (the) and pronouns (it) (Martin and Rose 2007, 163). In comparison with objects, institutions and abstractions are not so concrete, however, they can be identified in a like manner. One more resource for tracking participants (people and things) is comparison. In such cases the following words are being used: same, similar, other, different, else, first, second, third, next, last, former, latter etc.. 5.4 POWER AND IDEOLOGY IN THE LIGHT OF LANGUAGE Martin and Rose’s view on power and ideology in the context of language is that language users do not have an equal access to resources of meaning. Many a reader lacks resources for meaning which originate from different institutions, such as sciences, education or legislation; consequently, they cannot be actively involved in these discourses. Discourse analysis can contribute to advancements in equal range of resources for everyone by its literacy pedagogies. In addition, discourse analysis has been examining the reasons for uneven distribution of access to meaning (Martin and Rose 2007, 16). At this point we need to mention a method of discourse analysis called critical discourse analysis (CDA). It studies relevant social issues and forms of social discriminations, for example sexism, racism, nationalism and so on. Its emphasis is on connections between discourse and society (culture, politics etc.), and it aims its attention at power, inequality, control, and at how members of a discourse community create or resist them. CDA tries to unveil underlying ideologies that support inequality and control, which are usually hidden and impalpable. It further applies its approaches to film, photos, pictures, sounds, music and more (van Dijk 1995, 17–19). Critical. 19.

(32) discourse analysis is to a large extent based on the model of language and discourse proposed within systemic-functional linguistics.. 5.5 GENRE Within the field of discourse analysis, a great emphasis is put on genre. Genre consists of certain patterns of meaning, which make it easier to be recognized. As we grow up, we learn to distinguish between different kinds of genre, which make our life easier in a way that we recognize a certain social context and respond accordingly. For example, we learn what to say and how to react when our neighbors greet us, or we recognize scientific reports and judicial decisions (Martin and Rose 2007, 8). In order to recognize particular genres, we observe their rhetorical features, such as register, style and lexis (Hyland 2002, 116). Hyland (2002) argues that genres reveal different purposes of a writer or an institution, predictions of their audience, and various means of communication with a reader. People use written and spoken genres to express meanings in context. The same genre can vary “in relation to culture, historical period, social community and communicative setting” (Hyland 2002, 120). Genres can tell a great deal about discourse community that uses them, for example about its social norms, ideology, expectations etc. (Hyland 2002, 121). It is important to point out that a discourse community is not a utopian construct of a society with overall shared values. Rather, it consists of individuals with different beliefs and customs that create diversity within the same discourse community. In his article Hyland states that “a central principle of genre theory is that genres are ideological” (Hyland 2002, 124). It means that every text reflects values and beliefs of its users, and that within discourse community there are genres that are more dominant than others. The later implies that by using a certain genre that is not available to everyone some people are more privileged than others, what consequently leads to social inequalities. Such examples are academic and professional genres, which are. 20.

(33) often abstract in meaning, metaphorical, technical and considerably apart from everyday genres we use in our homes and neighborhoods. Martin and Rose (2007) state that in order to begin with discourse analysis of a text, an analyst needs to identify its genre (Martin and Rose 2007, 255). According to their division of genre, the written texts I chose for my analysis belong to the genre of stories, which is further divided into recount, anecdote, exemplum, observation and narrative. News stories are defined as peripheral types of the broader story genre. Though it might seem uncommon that they fall into a family of story genre, the theorists classify them as such because one can still chronologically reconstruct events (Martin and Rose 2008, 244). We will focus on some important features of the news story genre below.. 5.6 NEWSPAPER STORY AS A MASS MEDIA DISCOURSE Stories are a part of every culture, therefore it is not odd that they are the most widely studied genre family. Progress in technology has significantly affect the story genre and led to appearance of other genres in the fields of science, industry and bureaucracy. As more recent example Martin and Rose (2008) mention the evolution of the modern news story which began around the turn of 19th century. In 1890s broadsheets appeared and the audience shifted from specific to mass readership. To attract wide range of readers, the news stories had to be sensational. In order to achieve that, the story does not follow time order of sequences, but jumps around in time for the purpose of attracting a reader. A recount genre on the other hand starts off at the beginning of events and closes where they end. (Martin and Rose 2008, 74). One significant feature of a newspaper story is its structure, which consists of alternating voices and issues (Martin and Rose 2008, 76). Different voices are introduced at various times in the text in order to present multiple speakers and different issues. Some news stories are more action oriented while others have evaluative meaning to appeal to wider audience of readers. Journalists use patterns of appraisals to manipulate and engage the reader.. 21.

(34) In the center of a newspaper story is a social or political event or issue, for example elections, riots, and as is in our case, sexual harassment (van Dijk 1995, 5). Usually, we find the first important piece of information about a newspaper article in its headline, where the main points are given (van Dijk 1995, 35). A headline therefore acts as a summary of what follows. As is the case in many other discourse types, newspaper stories do not tell everything. Some information must be inferred and some is omitted because it is considered common knowledge or so-called common presuppositions, but some might be left out on purpose because of underlying ideologies of the media (van Dijk 1995, 69–75). Newspaper stories are written in a special style, called news style which meets various obstacles of a written monological text. Readers are hardly ever addressed and as discourse participants they are present only indirectly; consequently, we can observe a distant attitude towards the reader. As opposed to some other written discourses (for example personal letters), newspaper stories are regarded as public discourse with a wide range of readers. It is regarded as inappropriate if a newspaper story contains colloquialisms and characteristics of spoken language, but if it is important that they appear in the text, they are usually admitted within quotations. The authors use a formal style of writing with long, complex sentences and a special lexis (technical words, jargon). Within the field of news writing, many new words are coined and often original ways to look at past affairs are presented. Newsmakers need to adjust their texts in order to meet set space standards. Compact writing is a special style of writing which includes avoiding repetition, the use of relative clauses and nominalizations, and also assumption that the reader possesses knowledge about the topic under discussion from reading previous articles or by gaining it from other sources (van Dijk 1995, 74–76). Another characteristic of newspaper stories is that they are impersonal, because they are not generated by one individual but by institutionalized organizations. Although sometimes newspaper stories are signed, the names do not signal that a personal expression is included. Although it is generally expected that news are impartial and detached (Henry and Tator 2002, 4), personal or institutional ideologies cannot be. 22.

(35) entirely absent from the texts. Hidden believes and attitudes in the text can come into light indirectly and can be manifested, for example, through selection of topics and words used for description of certain facts. The ideologically-based lexis carries a deeper meaning and reveals implied values, for example, the same person can be denoted as a terrorist or as a freedom fighter, and as an immigrant or as a newcomer (van Dijk 81–82). In their book Discourses of Domination (2002) Henry and Tator contend that the media are a powerful institution, since they strengthen and pass on ideas, symbols and concepts of the society alongside with national myths. Newspaper stories are part of larger media discourse which greatly influences the collective belief and value system of the society. The media should “reflect alternative viewpoints” and “provide free and equitable access to all groups, irrespective of their sociocultural identity […], gender, social class, racial or ethnic background, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, and so on” (Henry and Tator 2002, 4). The media have an immense impact on the society and individuals, because they help in creating our conceptions and understandings about what is socially acceptable, and they mould our image of immigrants, women, homosexuals, the homeless and so on. It is not an exaggeration to say that film, music, literature, internet, radio and academia all form our identity as a culture and as individuals. Many people base their beliefs, even values, on what they see or hear in the mass media. The news provides them with an understanding of current affairs, on which they shape their opinions about the world. Another function of the media is that they serve as a mirror “in which society can see itself reflected” (Henry and Tator 2002, 5), though it can be argued whether the reflection is objective or disfigured (Henry and Tator 2002, 4–8).. 5.7 REGISTER OF THE SELECTED TEXTS Besides identification of genre of the selected texts, we need to define their register. Register represents one of the two most commonly discussed levels of context within. 23.

(36) SFL. Systemicists identify three basic dimensions of situations that impact the use of language. The three variables of register are field, mode and tenor (Eggins 2004, 9). 5.7.1. The field of sexual harassment. The field provides us with information about a territory of human experience (e. g. family life, law, medicine, public affairs) and belongs with ideational metafunction of a text. The texts we have chosen for our analysis are of the same field. They are about sexual harassment of women and men in their workplace.. 5.7.1.1. Sexual harassment in the workplace: the US context. The term sexual harassment became more widely used after the publication of Lin Farley’s book Sexual Shakedown: The Sexual Harassment of Women on the Job (1978). The book contains women’s stories of sexual harassment, and thus opening a discussion on an important social problem. Though forty years old book would seem out-of-date in the society in which thousands of books are published every year, its topic is still extremely relevant today. Since we consider the context of United States, our interest is directed at how their culture defines and copes with sexual harassment. U. S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing laws that provide equal opportunities for job applicants and employees, regardless of race, religion, sex, age, ethnicity and disability. Amongst other work situations, the EEOC laws cover sexual harassment as well. The term is defined as a type of discrimination that includes “sexual harassment or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature” (US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [EEOC], n. d.). Furthermore, harassment is not necessarily sexual by nature but can encompass “offensive remarks about a person’s sex.” It is marked as illegal if someone in a workplace makes improper remarks about women (or men) in general and thus treats the opposite gender as inferior. The law does not define as illegal isolated incidents or occasional teasing but. 24.

(37) condemns those in which harassment is so recurrent or serious “that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment.” A harasser can be anyone in a workplace: a coworker, a supervisor, and even a client or a customer. In the texts for analysis, victims and perpetrators come from the field of entertaining industry. However, it must be emphasized that people who are affected by sexual harassment can be found in most industries. American financial and business site Business Insider published an article on this topic, saying that according to the poll from their partner MSN about one in three people in the US claim to be sexually harassed in workplace (Business Insider, November 30, 2017). The survey reveals that women are by far more affected than men. It has been reported that when a victim speaks up, many people distance themselves from him or her. Many victims are afraid to bring up the problem, because they are anxious about their careers. They frequently feel ashamed and blame themselves for what happened. In most cases, women are those who are sexually harassed, but there is a growing number of men who report that they are victims of harassment in the workplace. Men can as well experience unwanted touching and caressing or inappropriate sexual comments and jokes. It is often believed that men cannot be harassed, which gives them one more reason not to speak up, because they are afraid no one would believe them. Many victims believe they can handle the situation on their own, or they are certain unwanted behavior will end soon. Lately, there has been an increasing number of people in the American workplaces who dare to speak up about their experience of sexual harassment. Alongside with articles about accusations and stories of the victims, there appear articles on how to behave in the workplace in order to avoid being accused of inappropriate behavior towards the opposite sex. The author of the book Sex & The Office (2015) and a research scholar at the University of California, Kim Elsesser, argues that nowadays, men view even ordinary decent behavior as too risky for their career and reputation. The companies are becoming terrified of legal action, therefore, they send their employees on sexual harassment training courses. She counts examples of men who have been accused of 25.

(38) harassment because they opened the door for their female colleagues, or even complimented them on their new outfit. Because of such cases, the fear of misinterpretation of innocent, friendly remarks, has increased. The fear of facing the charge of sexual harassment has grown so strong that some university professors in the U. S. keep their office door open when alone with female students. As reported, many people, especially men, find it hard to decide whether smiling, opening the door, or complimenting their co-worker is appropriate or not. Such fear and mistrust can create toxic and paranoid work environment, and increase gender separatism. It is of great importance to talk about social issues and seek solutions for problems we face in our society. Media stories about sexual harassment often send a positive message that such a behavior will no longer be tolerated, even if the perpetrator is a powerful man of high position. However, sexual harassment allegations sometimes do not have enough evidence to support them. Nonetheless, they have a power to destroy prosperous careers of people accused (Elsesser 2015, 23–28). On the other extreme, there are accusations that have proven to be false, but still have a great impact on the career, family and personal life of an accused (Elsesser 2015, 29).. 5.7.2. Mode and tenor. Mode: From the textual viewpoint we focus on mode, where we observe whether a text is written or spoken. In our case we deal with written news reports, of which some contain possibility of immediate feedback, which is otherwise characteristic of non-written spontaneous dialogic discourse of interactivity – they allow readers to leave their comments in a comment section below the text (Radar Online, Perez Hilton, Celebitchy, Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, The Denver Post). One more characteristic of the considered texts about sexual harassment is that they comprise recordings of interviews with victims or perpetrators. Consequently, there are. 26.

(39) characteristics of a spoken language in written texts (spoken language written down). In such cases a text contains “everyday sorts of words, including slang and dialect features, and often sentences will not follow standard grammatical conventions” (Eggins 2005, 93). The following passage can be used as a demonstration; words in boldface type are examples of spoken language written down (interjections, repetitions, short grammatical forms, and everyday words): While there, Sivan alleges that Weinstein attempted to kiss her. "I immediately rebuffed and said, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa. I had no idea that that’s what this was. I’m sorry, I have a very serious boyfriend and I’m not interested,’" she told the Post […]. "[He] said, ‘Well, then stand there and be quiet’ … It happened very quickly and he immediately exposed himself and began pleasuring himself.” (TV Reporter Lauren Sivan Claims Harvey Sexually Harassed Her in 2007). When we observe how texts engage an audience (readers) and how they “position us to accept their author’s point of view” (Martin and Rose 2007, 256), we take notice of a text’s tenor. Tenor is a component of the third, interpersonal, metafunction of language in social context. “The interactive nature of discourse” as the expression of the social relationships between the speaker and the hearer is realized through appraisals (Martin and Rose 2007, 17). Tenor: Newspaper articles are written by individual authors, generally considered as experts in the field of reporting, for a non-expert general public, so the intended recipient is non-specific. The overall tenor of a text is reflected in the formality or informality of the language that is being used. In the texts selected for analysis of this MA thesis, more formal language is found in quality newspapers, although even those texts include features of informal language apart from those cited from another source. These features include:. 27.

(40) -. Short forms of auxiliary verbs: Sitting down with Carlson, it’s clear she’s meticulous.. -. Naming people of high positions without honorifics: Last year, Putin signed into law a provision that decriminalized domestic abuse for first-time offenders […].. -. Extremely short sentences: But an epidemic? Really.. -. Revealing emotions: But an epidemic? Even after Title IX and Anita Hill and Bill Cosby, really? (The author reveals her surprise through words she uses.). -. Judgement: Today, six brave women voluntarily spoke out to New York magazine detailing their traumatic sexual harassment by Ailes. (positive judgement of strength and competence). -. Appreciation: The Associated Press reported Friday on the experiences of one current and three former female lawmakers, who said they had fended off unwanted advances […].. Tabloids contain more of the above listed features of informal language, including first person point of view: We applaud her bravery!! We’ll continue to keep you updated. Excessive use of punctuation to emphasize the emotions of a writer are also characteristic of informal language in tabloids: We applaud her bravery!! In the following chapter, ten American newspaper stories are closely analyzed with discourse analysis methods. The purpose of the analysis is to find out how is sexual harassment constructed in these texts. Victims of sexual harassment and perpetrators are carefully examined. To find out how they are represented in the texts, three main categories were created for each participants (type of reference, function and appraisal), which were further divided into subcategories (personal name, pronoun, possessive proper noun, lexical gender-specific term, occupation, numeral, body part; sayer, doer; emotions and judgements). Voices apart from authorial are analyzed in order to see whether the authors allow voices of other participants to speak, and if they acknowledge their readers. The analysis includes 5 newspaper stories from American online tabloids and 5 from. 28.

Gambar

Dokumen terkait

Permasalahan yang dikaji dalam penelitian ini meliputi dampak yang timbul pasca dijatuhkan nya Putusan Pengadilan Negeri Nomor 309/Pdt.G/2007/PN.Jkt.Pst tersebut bagi

Berdasarkan hasil pengujian hipotesis pada penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa variabel bebas LDR, LAR, IPR, APB, NPL, PDN, IRR, BOPO, FBIR secara bersama-sama mempunyai pengaruh

[r]

Berdasarkan hasil analisis laboratorium, kandungan Na -dd di lahan sawah lebak Kabupaten Banjar tiga kecamatan yang diambil sampel tergolong kriteria Rendah

Berdasarkan hasil pra-survei yang dilaksanakan oleh peneliti diperoleh informasi bahwa seluruh karyawan wanita dan telah menikah (khususnya wanita yang masih memiliki anak

Tidak terdapat pengaruh merugikan baik terhadap berat badan maupun kenaikan berat badan tikus akibat pemberian bahan yang diuji, bahkan tikus yang diberi cekokan bahan

mengembangkan ide-ide kreatif lebih lanjut dengan memanfaatkan alternatif-alternatif kegiatan yang ditawarkan di dalam buku panduan guru, atau mengembangkan ide-ide

Katalis yang umum digunakan pada proses transesterifikasi pembuatan biodiesel adalah larutan basa atau asam dan dapat berupa katalis homogen ataupun