INTRODUCTION

The practice of emergency medicine requires both a broad knowledge base and a large range of technical skills. The effective practice of emergency medicine requires a

thorough comprehension of the assessment and management of conditions that threaten life and limb; the ability to provide immediate care is fundamental. Although there is a significant crossover between emergency medicine and other clinical specialties, emergency medicine has unique aspects, such as the approach to patient care and the decision making process.

HISTORY OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE

The history of emergency medicine as a distinct medical discipline encompasses the past 60 years. The genesis of emergency medicine involved several elements and stemmed from recognition of the unique nature of trauma care and emergency transport, increasing mobility of the population and improvements in emergency care and resuscitation. The American Board of Emergency Medicine became the twenty-third medical specialty, following its approval by the American Board of Specialties in September 1979. The first board examination in emergency medicine was offered in 1980. In the early 1980's, the Australian Society of Emergency Medicine was formed by a group of doctors committed to the practice and development of emergency medicine, and in 1993 the discipline was accepted as a principal specialty. These developments have led to the transformation in the practice of emergency medicine in most hospitals. However, away from the major centres, there are many non-specialist doctors playing an important role in the delivery of emergency care to seriously ill patients. These doctors often do so in relative isolation and without the benefit of the supervision and back up of specialists. Groups such as rural general practitioners and hospital based medical officers carry a significant emergency medicine role.

Emergency Medicine has long been established especially in Australasia, Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States, in Asia othe emergency medicine officially inauguration of Asian Society of Emergency Medicine in Singapore on the 24th of October 1998 at the first Asian Conference on Emergency Medicine which as Prof.DR.dr. Eddy Rahardjo,SpAnKIC and dr. Tri Wahyu Murni sat as member of Board Director.

It is thus sometimes seen to be synonymous with emergency medical care and within the province and expertise of almost all medical practitioners. However, the Emergency Medicine incorporates the resuscitation and management of all undifferentiated urgent and emergency cases until discharge or transfer to the care of another physician. Emergency Medicine is an inter-disciplinary specialty, one which is interdependent with all other clinical disciplines. It thus complements and does not seek to compete with other medical specialties.

Basic science concepts to help in the understanding of the phatophysiology and treatment of disease.The medical curriculum has become increasingly vertically integrated, with a much greater use of clinical examples and cases to help in the understanding of the relevance of the underlying basic science, The Emergency Medicine block has been written to take account of this trend, and to integrate core aspects of basic science, pathophysiology and treatment into a single, easy to use revision aid.

In accordance the lectures that have been full integrated for studens in 6 Th

semester, period of 2012, one of there is The Emergency Medicine Block. There are many topics will be discuss as below:

,Shock, Cardiac critical care (Cardiac arrest and CPR), Emergency toxicology and poisoning, Pregnancy induce Hypertension, Shoulder dystocia, Urologic concern in critical care, Phlegmon, Acute Blistering and Expoliative skin, Trauma which potentially disabling and Life threatening condition and Basic Clinical Skill

Beside those topics, also describes the learning outcome, learning objective, learning task, self assessment and references. The learning process will be carried out for 4 weeks (20 days).

Due to this theme has been prepared for the second time, so many locking mill is available on it. Perhaps it will better in the future

CURRICULUM CONTENTS

Mastery of basic knowledge with its clinical and practical implication include airway, breathing and circulation management.

Establish tentative diagnosis, provide initial management and refer patient with : Seizure and mental status changes

Acute Psychiatric episode

Acute respiratory distress syndrome and failure

Bleeding disorders (epistaxis, dental bleeding, vaginal bleeding) Shock

Cardiac critical care (Cardiac arrest and CPR) Emergency toxicology and poisoning

Pregnancy induce Hypertension, Shoulder dystocia Urologic concern in critical and non critical care Phlegmon

Acute Blistering and Expoliative skin

Trauma which potentially disabling and Life threatening condition

SKILLS

To implement a general strategy in the approach to patients with critical ill through history and physical examination and special technique investigations

To manage by assessing, provide initial management and refer patient with critical ill

PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT/ATTITUDE Awareness to :

Ethic in critical care

Basic principle of critical care

The importance of informed consent to patient and family concerning critical ill situations

Risk of patient with critically ill and its prognosis

COMMUNITY ASPECT :

Communicability of the critical cases Cost effectiveness

PLANNERS TEAM

NO. NAME DEPARTMENT

1. Dr.dr. Tjok Gde Agung Senapathi, Sp.AnKAR (Chairman)

Anesthesiology and Intensif Terapy 2. dr. I Ketut Suyasa, SpB,SpOT(K) (Secretary) Surgery

3. dr. IGN Budiarsa,SpS Neurology

4. dr. Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL, dr. Wayan Sucipta, SpTHT KL

ENT

5. drg. Putu Lestari Sudirman, M.biomed. Dentistry

6. dr. Agus Somya, SpPD, KPTI Internal Medicine

7. dr. Dewa Made Artika, SpP Pulmonology

8. Dr.dr. Diah Kanyawati, SpA(K) Pediatric

9. Dr.dr. Wayan Megadana, SpOG(K) Obstetric-Gynecologic

10. dr. Hariyasa Sanjaya, SpOG(K) Obstetric-Gynecologic

11. dr. Megaputra, SpOG(K) Obstetric-Gynecologic

12. dr. Gd Wirya Kesuma Duarsa, SpU, MKes, dr. Budisantosa, SpU

Surgery

13. dr. Ratep,SpKJ Psychiatric

14. dr. Nyoman Suryawati, SpKK Dermatology

15 dr. Sri Laksminingsih SpR (K) Radiology

LECTURERS

NO. NAME DEPARTMENT PHONE

1. Dr.dr. Tjok Gde Agung Senapathi, Sp.AnKAR (Chairman)

Anesthesiology and Intensif Terapy

081337711220

2. dr. I Ketut Suyasa, SpB,SpOT(K) (Secretary)

Surgery 081558724088

3. dr. IGN Budiarsa,SpS Neurology 0811399673

4. dr. Sari Wulan,SpTHT KL, dr. Wayan Sucipta,SpTHT KL

ENT 081237874447(SW)

08125318941 (WS) 5. drg. Putu Lestari Sudirman,

M.biomed.

Dentistry 08155764446/7494974

6. dr. Agus Somya, SpPD, KPTI Internal Medicine 08123989353 7. dr. Dewa Made Artika, SpP Pulmonology 08123875875 8. Dr. dr. Diah Kanyawati, SpA(K) Pediatric 081285705152 19. Dr.dr. Wayan Megadana,

SpOG(K)

Obstetric-Gynecologic

08123917002

10. dr. Hariyasa Sanjaya, SpOG(K) Obstetric-Gynecologic

081558314827

11. dr. Megaputra, SpOG(K) Obstetric-Gynecologic

08123636172

12. dr. Gd Wirya Kesuma Duarsa, SpU,MKes, dr. Budisantosa, SpU

Surgery 081339977799 (BS)

081338333951 (GWK)

13. dr. Ratep,SpKJ Psychiatric 08123618861

FACILITATORS

(REGULAR CLASS)

N

O

NAME

GROUP

DEPT

PHONE

VENUE

1 Dr. dr. I Wayan Putu Sutirta Yasa, M.Si

1 Clinical

Pathology

08123953344 2nd floor:

R.2.09

2 dr. Yuliana, M Biomed 2 Anatomy 085792652363 2nd floor:

R.2.10 3 Dr.dr. Anna Marita Gelgel,

Sp.S(K)

3 Neurology 08123800180 2nd floor:

R.2.11 4 dr. Pratihiwi Primadharsini,

M.Biomol, Sp.PD

4 Interna 081805530196 2nd floor:

R.2.12 5 dr. Ni Luh Putu Ariastuti , MPH 5 Public Health 0818560008 2nd floor:

R.2.13 6 dr. Reni Widyastuti, S.Ked 6 Pharmacology 08174742501 2nd floor:

R.2.14 7 dr. Ida Bagus Alit, Sp.F, DFM 7 Forensic 081916613459 2nd floor:

R.2.15 8 dr. Agus Roy Rusly Hariantana

Hamid, Sp.BP-RE

8 Surgery 08123511673 2nd floor:

R.2.16 9 dr. I Ketut Wibawa Nada, Sp.An 9 Anasthesi 087860602995 2nd floor:

R.2.20

10 dr. Muliani , M Biomed 10 Anatomy 085103043575 2nd floor:

R.2.23

FACILITATORS (ENGLISH CLASS)

NO NAME GROUP DEPT PHONE VENUE

1 dr. Jodi Sidharta Loekman, SP.PD-KGH-FINASIM

1 Interna 08123810423 2nd floor:

R.2.09 2 dr. Ida Ayu Sri Wijayanti,

M.Biomed, Sp.S

2 Neurology 081337667939 2nd floor: R.2.10 3 dr. I Wayan Sugiritama, M.Kes 3 Histology 08164732743 2nd floor:

R.2.11

4 dr. I Made Sudipta, Sp.THT- KL 4 ENT 08123837063 2nd floor:

R.2.12 5 dr. I Made Oka Negara, S.Ked 5 Andrology 08123979397 2nd floor:

R.2.13 6 dr. Jaqueline Sudirman,

GrandDipRepSc, PhD 6 Obgyn 082283387245 2nd floor:R.2.14

7 dr. Dyah Kanya Wati, Sp A (K) 7 Pediatric 05737046003 2nd floor: R.2.15 8 Dr.dr. Cokorda Bagus Jaya

Lesmana, Sp.KJ

8 Psychiatry 0816295779 2nd floor:

R.2.16 9 Dr. dr. Made Sudarmaja, M.Kes 9 Parasitology 08123953945 2nd floor:

R.2.20 10 dr. Ida Bagus Kusuma Putra,

Sp.S

TIME TABLE

Regular Class

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING

ACTIVITY VENUE CONVEYER 1. Mon, 7 Sept 2015

08.00-09.00 Highlight in

Emergency Medicine (Chairman)

Class room

Dr.dr. Tjok Gde Agung

Senapathi, Sp.AnKAR

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room

Dr.dr. Tjok Gde Agung

Senapathi, Sp.AnKAR

2.Tue, 8 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 2.

Status Epilepticus and Other Seizure Disorders

Class room

dr. IGN Budiarsa,SpS

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room

dr. IGN Budiarsa,SpS

3.Wed, 9 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 3.

Acute Psychiatric Episodes

Class room

dr. Ratep,SpKJ

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room

dr. Ratep,SpKJ

4.Thu, 10 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 4.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Failure

Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team), Dr. Dewa

Made Artika, SpP, Dr. dr

Diah Kanyawati,SpA (K),

dr. Srie Laksminingsih,

SpR

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team)

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING ACTIVITY VENUE CONVEYER 5. Fri, 11 Sept 2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 5. Bleeding Disorder(Epistaxis,

Hemorrhage In

Pregnancy) and

Airway

Obstruction

Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL, dr. Sucipta, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team) Dr.dr Wayan

Megadhana, SpOG(K) (and OBGYN Team)

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL, dr. Sucipta, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team) Dr.dr Wayan

Megadhana, SpOG(K) (and OBGYN Team) 6.

Mon, 14 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 6.

Shock Class room dr. IGAG. Utara Hartawan, SpAn MARS

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr. IGAG. Utara

Hartawan, SpAn MARS 7.

Tue, 15 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 7.

Cardiac Arrest and + Cardiopulmonary Resuscitaton

Class room dr. IGN. Mahaalit Aribawa, SpAn KAR

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr. IGN. Mahaalit Aribawa, SpAn KAR 8

Wed, 16 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 8 Emergency Toxicology and Poisoning

Class room dr. Agus Somya, SpPD KPTI

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING ACTIVITY VENUE CONVEYER

9 Thu, 17 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 9

Pregnancy Induce Hypertension

Class room dr. Megaputra, SpOG(K)

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr. Megaputra, SpOG(K) 10

Fri, 18 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 10

Shoulder Dystocia Class room dr. Hariyasa Sanjaya, SpOG(K)

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr. Hariyasa Sanjaya, SpOG(K) 11.

Mon, 21 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 11

Acute Blistering and Exfoliative Skin

dr. Nyoman Suryawati Sp.KK

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Fasilitator

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary dr. Nyoman

Suryawati Sp.KK 12.

Tue, 22 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 12. Trauma Which Potentially Disabling and life Threatening Conditions

dr. Ketut Suyasa, SpB SpOT(K) Spine dr. IGN Wien Aryana, SpOT

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Fasilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary dr. Ketut Suyasa,

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING ACTIVITY VENUE CONVEYER 13 Wed, 23 Sept 2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 13. Phlegmon

Class room Drg. Lestari Sudirman

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning -

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room Drg. Lestari

Sudirman

14 Fri, 25 Sept

2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 14.

Urologic Concern in Critical Care for NonTrauma Case

Class room dr. Gede Wirya Kusuma Duarsa, M.Kes, SpU(K)

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr. Gede Wirya

Kusuma Duarsa, M.Kes, SpU(K) 15 Mon, 28 Sept 2015

08.00-09.00 Lecture 15

Urologic Concern in Critical Care for Trauma Case

Class room

dr. Budi Santosa, SpU

09.00-10.30 Individual Learning -

-10.30-12.00 SGD Disc room Facilitators

12.00-12.30 Break

12.30-14.00 Student Project

14.00-15.00 Plenary Class room dr. Budi Santosa, SpU

16. Tue, 29 Sept

2015

08.00-selesai Basic clinical skill (1)

CPR (Regular Class) Clinical skill lab Team

17. Wed, 30 Sept

2015

08.00-selesai Basic clinical skill (2) Basic Trauma Care (Regular Class)

Clinical skill lab Team

18. Thu, 1 Oct 2015

08.00-Finish Basic clinical skill (1)

CPR (English Class) Clinical skill lab Team

19. Fri, 2 Oct 2015

08.00- Finish Basic clinical skill (2) Basic Trauma Care (English Class)

Clinical skill lab Team

Sat-Sud-

Mon-Tue-Wed,

3-4-5-6-7

Oct

2015

Examination

21 Thu, 8 Oct

2015.

EXAMINATION

English Class

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING

ACTIVITY VENUE CONVEYER 1. Mon, 7 Sept 2015

09.00-10.00 Highlight in

Emergency Medicine (Chairman)

Class room

Dr.dr. Tjok Gde Agung

Senapathi, Sp.AnKAR

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room

Dr.dr. Tjok Gde Agung

Senapathi, Sp.AnKAR

2.Tue, 8 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 2.

Status Epilepticus and Other Seizure Disorders

Class room

dr. IGN Budiarsa,SpS

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room

dr. IGN Budiarsa,SpS

3.Wed, 9 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 3.

Acute Psychiatric Episodes

Class room

dr. Ratep,SpKJ

10.00-11.30 Student Project

11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room

dr. Ratep,SpKJ

4.Thu, 10 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 4.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Failure

Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team), Dr. Dewa

Made Artika, SpP, Dr. dr

Diah Kanyawati,SpA (K),

dr. Srie Laksminingsih,

SpR

10.00-11.30 Student Project

11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team)

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING ACTIVITY VENUE CONVEYER 5. Fri, 11 Sept 2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 5.

Bleeding Disorder Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL, dr. Sucipta, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team) Dr.dr Wayan

Megadhana, SpOG(K) (and OBGYN Team)

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr Sari Wulan, SpTHT KL, dr. Sucipta, SpTHT KL ( and ENT Team) Dr.dr Wayan

Megadhana, SpOG(K) (and OBGYN Team) 6.

Mon, 14 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 6.

Shock Class room dr. IGN. Mahaalit Aribawa, SpAn KAR

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. IGN. Mahaalit Aribawa, SpAn KAR 7.

Tue, 15 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 7.

Cardiac Arrest and + Cardiopulmonary Resuscitaton

Class room dr. IGAG. Utara

Hartawan, SpAn MARS

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. IGAG. Utara

Hartawan, SpAn MARS 8

Wed, 16 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 8 Emergency Toxicology and Poisoning

Class room dr. Agus Somya, SpPD KPTI

10.00-11.30 Student Project

11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

9 Thu, 17 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 9

Pregnancy Induce Hypertension

Class room dr. Megaputra, SpOG(K)

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. Megaputra, SpOG(K) 10

Fri, 18 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 10

Shoulder Dystocia Class room dr. Hariyasa Sanjaya, SpOG(K)

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. Hariyasa Sanjaya, SpOG(K) 11.

Mon, 21 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 11

Acute Blistering and Exfoliative Skin

Class room dr. Nyoman Suryawati Sp.KK

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Fasilitator

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. Nyoman

Suryawati Sp.KK 12.

Tue, 22 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 12. Trauma Which Potentially Disabling and life Threatening Conditions

Class room dr. Ketut Suyasa, SpB SpOT(K) Spine dr. IGN Wien Aryana, SpOT

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Fasilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. Ketut Suyasa, SpB SpOT(K) Spine dr. IGN Wien Aryana, SpOT

DAY/DATE TIME LEARNING

ACTIVITY

VENUE CONVEYER

13

23 Sept

2015 10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room Drg. Lestari

Sudirman

14 Fri, 25 Sept

2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 14.

Urologic Concern in Critical Care for NonTrauma Case

Class room dr. Gede Wirya Kusuma Duarsa, M.Kes, SpU(K)

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. Gede Wirya

Kusuma Duarsa, M.Kes, SpU(K) 15 Mon, 28 Sept 2015

09.00-10.00 Lecture 15

Urologic Concern in Critical Care for Trauma Case

Class room

dr. Budi Santosa, SpU

10.00-11.30 Student Project

-11.30-12.00 Break Facilitators

12.00-13.30 Individual Learning

13.30-15.00 SGD Disc Room

15.00-16.00 Plenary Class room dr. Budi Santosa, SpU

16. Tue, 29 Sept

2015

08.00-selesai Basic clinical skill (1)

CPR Clinical skill lab Team

17. Wed, 30 Sept

2015

08.00-selesai Basic clinical skill (2)

Basic Trauma Care Clinical skill lab Team

18. Thu, 1 Oct 2015

08.00-Finish Basic clinical skill (1)

CPR (English Class) Clinical skill lab Team

19. Fri, 2 Oct 2015

08.00- Finish Basic clinical skill (2) Basic Trauma Care (English Class)

Clinical skill lab Team

3-4-5-6-7

Oct

2015

21 Thu, 8 Oct

2015.

EXAMINATION

ASSESSMENT METHOD

Assessment will be carried out on Thursday 8 th of October 2015. There will be 100 questions consisting mostly of Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) and some other types of questions. The minimal passing score for the assessment is 70. Other than the examinations score, your performance and attitude during group discussions will be consider in the calculation of your average final score. Final score will be sum up of student performance in small group discussion (5% of total score) and score in final assessment (95% of total score). Clinical skill will be assessed in form of Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) at the end of semester as part of Basic Clinical Skill Block’s examination.

STUDENT PROJECT

with different tittle. The paperwork will be written based on the direction of respective lecturer. The paperwork is assigned as student project and will be presented in class. The paper and the presentation will be evaluated by respective facilitator and lecturer.

Format of the paper :

1. Cover Title (TNR 16)

Name Green coloured cover Student Registration Number

Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University 2015

2. Introduction

3. Journal critism/literature review 4. Conclusion

5. References

Example : Journal

Porrini M, Risso PL. 2005. Lymphocyte Lycopene Concentration and DNA Protection from Oxidative Damage is Increased in Woman. Am J Clin Nutr 11(1):79-84.

Textbook

Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pober JS. 2004. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 4th ed.

Pennysylvania: WB Saunders Co. Pp 1636-1642.

Note.

Minimum 10 pages; line spacing 1.5; Times new roman 12

STUDENT PROJECT

lecturer. The paperwork is assigned as student project and will be presented in class. The paper and the presentation will be evaluated by respective facilitator and lecturer.

Format of the paper :

6. Cover Title (TNR 16)

Name Green coloured cover Student Registration Number

Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University 2012

7. Introduction

8. Journal critism/literature review 9. Conclusion

10. References

Example : Journal

Porrini M, Risso PL. 2005. Lymphocyte Lycopene Concentration and DNA Protection from Oxidative Damage is Increased in Woman. Am J Clin Nutr 11(1):79-84.

Textbook

Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pober JS. 2004. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 4th ed.

Pennysylvania: WB Saunders Co. Pp 1636-1642.

Note.

Minimum 10 pages; line spacing 1.5; Times new roman 12

LEARNING PROGRAMS

Tjok Gde Agung Senapathi

Objective

To describe

1. Highlight Emergency Medicine

2. Basic principal of Emergency Medicine 3. Triad Emergency Medicine

4. Ethics in critical care

Medical ethics is the art of resolving conflicts that arise around treatment and treatment decisions. The conflict may involve the patient, family, caregivers, or society. An approach to these conflicts is as necessary as, say, an approach to hypotension or oliguria. Without an approach we would be ignoring the mechanism that led the conflict or problem in the first place. A little preparation will allow one to be more comfortable when confronting these situations, making responses more likely to be useful (and less likely to make things worse).

There are four basic principles or medical ethics that give us the tools to begin to resolve some of these conflicts : autonomy, beneficence, and justice. The weight we give each of these four different principles is often determined by our individual and societal morals.

AIRWAY

OBJECTIVES

1. To review basic airway management

2. To review indications for definitive airway management 3. To review rapid sequence intubation

INTRODUCTION

In the resuscitation of any patient, management of the airway is the first priority. One cannot continue in managing breathing or circulation problems if the patient does not have a patent airway. Even after airway management has taken place, in any patient who fails to improve, or who deteriorates, always start again with assessment and management of the airway. ASSESSING THE AIRWAY

Before managing any patient‘s airway, it is important to quickly assess and identify those patients in whom you anticipate difficulty in ventilation and / or intubation. If you do – call for help.

Some key predictors of a difficult airway include: Difficult Bag-valve Mask Ventilation -

“BOOTS”

B = Beard O = Obese

O = Older T = Toothless S = Snores / Stridor

Difficult Intubation - “MAP the Airway” M = Mallampati Class and Measurements

Evaluate the Mallampati classification by asking patient to open their mouth ―3-3-2-1 rule ‖ 3 fingers mouth opening

3 fingers distance from hyoid to chin

2 fingers distance from thyroid cartilage notch to floor of mandible 1 finger anterior jaw subluxation

A = Atlanto-occipital (neck) extension Normal = 35 degrees or more

P = Pathologic conditions

Tumour, hematoma, trauma, etc.

REVIEW OF AIRWAY TECHNIQUES Temporizing / Adjunctive Measures

Chin lift/jaw thrust to open airway - caveat: no neck extension if suspected C-spine injury

Bag-valve-mask ventilation – probably the most important, yet under-appreciated, skill of airway management. In the ED, when bagging, use a two-hands on the mask technique for a tight seal, and always use an oral airway

Suctioning/removal of foreign bodies

Nasal airway - generally well-tolerated by the temporarily obtunded patient (e.g. post-ictal, post-procedural sedation, intoxicated)

Oral airway – aids in peri-intubation ventilation; not to be used in patient with intact gag reflex

Laryngeal mask airway (LMA) – this device is inserted into the mouth and has a cuff that occludes the hypopharynx. It has a port through which ventilation can then occur. A variation is the Intubating LMA – this allows the insertion of an endotracheal tube via the ventilation port. The LMA is used both as a ―rescue device in failed‖ intubation, and as a primary airway device

Needle cricothyroidotomy - accomplished by inserting a needle in cricothyroid membrane, and oxygenating the patient using high pressure oxygen source

Definitive Airway

A definitive airway is the placement of a cuffed tube in the trachea. A cuffed endotracheal tube does not ensure that aspiration cannot occur, but does reduce the risk.

Orotracheal / nasotracheal intubation

Section One RESUSCITATION INDICATIONS FOR INTUBATION

The indications for intubation can be broken down into four main categories. These can be recalled as the four P s:‟

1. Patency - to obtain and maintain a patent airway in the face of obstruction. Examples include: decreased LOC, airway edema/burns, neck hematoma, tumour 2. Positive-pressure ventilation - to correct deficient oxygenation and/or ventilation.

Examples include: pulmonary edema, COPD exacerbation

3. Protection - to protect the airway from aspiration in the event of decreased LOC 4. Predicted deterioration - in some situations, early intubation may be preferable to the

potential need to urgently intubate in a less favourable environment (e.g. in CT scan), or when it may be significantly more difficult (e.g. progressive edema)

WHEN INTUBATION SHOULD BE ANTICIPATED

The following are several situations during which ED patients are commonly intubated: Trauma

Overdoses on medications which cause rapid decrease in level of consciousness Severe congestive heart failure, asthma, COPD

Head injured patients, or those who are comatose for non-traumatic reasons

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE ED

Airway management in the ED usually occurs on an urgent or emergent basis. The following are some things to keep in mind, as they will modify the plan of airway management:

less time to assess airway, obtain past history, etc. less controlled than in the elective setting

patients are frequently hemodynamically unstable

all must be considered to have full stomachs, with the attendant risk of aspiration patients often have altered mental status, from markedly decreased to

fighting/agitated due to alcohol, drugs, or head injury

Cervical spine injury and instability must be assumed in patients who have experienced major trauma, falls, or have an unknown history of injury.

this consideration requires modification of airway techniques, both basic and advanced

when intubating a patient with a known or suspected c-spine injury, remove the front of the cervical collar and have an assistant manually stabilize the neck (‗in-line manual stabilization‘). The collar can be replaced once tube placement is confirmed.

Rapid sequence intubation is defined as the simultaneous administration of a powerful sedative (induction) agent and a paralytic agent to facilitate intubation and decrease the risk of aspiration.

Although a detailed discussion of RSI is beyond the scope of this chapter, the basic steps are reviewed below. These can be recalled as the six P s. ‟

1. Preparation – prepare all equipment, personnel, and medications

2. Pre-oxygenation – patient breathing 100% oxygen for 3-5 minutes or asking the patient to take 4-8 full breaths on 100% oxygen will wash out the nitrogen in the lungs, and prolong the time available for intubation before desaturation occurs.

3. Pretreatment – pretreatment with medications such as atropine in children, defasciculating doses of a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant prior to the administration of succinycholine, and lidocaine in the setting of head injury is considered optional, given the lack of evidence for their benefit

4. Paralysis with induction – administration of a sedative agent (e.g. ketamine, propofol, etomidate) followed rapidly by the administration of a muscle relaxant (e.g. succinylcholine or rocuronium)

5. Place the tube with proof – intubate the patient, and confirm tube placement with end-tidal capnometry

6. Post-intubation management – chest x-ray, analgesia and sedation, further resuscitation

Relative contraindications to rapid sequence intubation include:

anticipated difficult airway, especially difficult bag-valve mask ventilation. In this situation, an ―awake intubation with the patient maintaining respirations is‖ preferred

inadequate familiarity and comfort with the technique

unnecessary (e.g. the patient in cardiac arrest or near-arrest)

THE TECHNIQUE OF LARYNGOSCOPY

Ensure that the proper preparations have been made, and the patient is positioned correctly in the ―sniffing position . The laryngoscope is held in the left hand, ‖

and introduced into the mouth on the right side of the tongue. Advance the laryngoscope slowly to the base of the tongue. Identification of the epiglottis is crucial. A common novice error is to rapid insert the blade too deeply, missing identification of the epiglottis.

Once the epiglottis is identified, seat the tip of the blade in the vallecula. Lift can now be applied to the laryngoscope in the direction of the handle. Do not lever the blade back. Once the epiglottis is lifted, the vocal cords should come into view. Without losing sight of the vocal cords, ask an assistant to hand you the endotracheal tube in your right hand. The tube is introduced into the right side of the patient‘s mouth without obscuring your view of the cords. It is important to visualize the tip of the tube as it passes through the cords. As the tip passes, ask the assistant to remove the stylet, and place the tube in its final position. Inflate the cuff, and confirm end-tidal CO2.

For an excellent laryngoscopy video, go to http://emcrit.org/airway/laryngoscopy

TIPS AND TOOLS TO FACILITATE INTUBATION

A number of tips and tools exist that can make intubation easier, even in patients for whom a clear visualization of the vocal cords is not possible. Some of those commonly used in the ED include:

‗BURP‘ technique – refers to application of ‗backward, upward, rightward pressure‘ on the larynx to facilitate visualization of the cords during laryngoscopy. It is important to understand how this differs from ‗cricoid pressure‘ which is applied in order to prevent aspiration

Bougie or tracheal tube introducer – long, thin, flexible device inserted under the epiglottis during laryngoscopy. As it enters the trachea, ―clicks are felt as‖ thebougie passes over tracheal rings, and it STOPS when it reaches a mainstem bronchus. If esophageal, no clicks are felt and the bougie advances into stomach. Once in trachea, advance ET tube over bougie.

Video laryngoscopy (Glidescope) – a laryngoscope with a camera mounted on a more sharply-angled blade allows for improved visualization of the anterior larynx

SUMMARY

Most patients' airways can be managed, at least temporarily, with simple airway maneuvers and a bag-valve mask device

Familiarize yourself with assessing an airway

Emergency patients have a number of special considerations regarding airway management

In any patient who fails to improve, or who deteriorates, always start again with assessment and management of the airway

REFERENCES

1. Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Airway Interventions and Management Education (AIME) manual.

2. Kovacs G, Law JA. Airway Management in Emergencies. 2008; McGraw-Hill. 3. Blanda M, Gallo UE. Emergency airway management. Emerg Med Clin North Am

2003;21(2):1-26.

4. Reynolds SF, Heffner J. Airway Management of the Critically-Ill Patient: Rapid Sequence Intubation. Chest 2005;127(4):1397-412.

5. McGill J. Airway Management in Trauma: An Update. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2007;25:603–622

BREATHING

1. To develop an organized approach to breathing problems

2. To use the history and physical examination to help identify the cause of breathing problems

3. To understand the utility of various investigations for breathing problems 4. To know the various treatment modalities related to breathing problems

INTRODUCTION

After airway, the next priority in resuscitation (ABC‘s) is assessment and management of breathing problems. The label ‗Breathing‘ encompasses all problems related to shortness of breath (SOB) and respiratory dysfunction, and these are among the most common clinical problems encountered in the Emergency Department (ED).

Airway and breathing problems can be difficult to distinguish from each other initially, and are frequently assessed in tandem. Of course, airway management always comes first. ‗Breathing‘ comes before ‗Circulation‘ in resuscitation because there is no point in working on the pump part of the equation unless that pump is delivering oxygenated blood to the tissues.

APPROACH

The causes of respiratory distress or dyspnea are myriad. Rather than learn long lists of possible diagnoses, it is better to have a clear approach in which to organize all the information gathered from your history and physical exam. However, the following is a short list of immediately life-threatening diagnoses that must be rapidly identified and treated:

Pulmonary Embolus Pulmonary Edema (CHF) Acute exacerbation of COPD Acute severe Asthma

Tension Pnuemothorax

Mnemonic: Breathing Poorly Can Cause Alot of Tension

After considering these immediately life-threatening diagnoses, an anatomical approach can be used to identify other causes of breathing difficulties:

Bronchi and Bronchioles Asthma, COPD, Bronchiectasis

Lung Parenchyma

The etiologies listed with clinical examples cause problems by filling or blocking the alveoli and thus preventing gas exchange. Alveoli can be blocked by pus (infection), fluid (edema), blood and gastric contents (aspiration).

Blood: Pulmonary Contusion, Goodpasture‘s Syndrome, Bleeding Carcinoma

Fluid/Edema: CHF, ARDS, Neurogenic Pulmonary Edema, Toxin/Drug Induced Pulmonary Edema, High Altitude Pulmonary Edema

Pus/Infection: Bacterial Pneumonia, TB, Fungal Gastric Contents: Aspiration Diffusion Diseases: Amyloidosis, Interstitial Pulmonary Fibrosis

Vasculature and Blood

This category includes blockage of the pulmonary circulation and disorders of the content/chemistry of the blood.

Emboli: Clot, Fat, Air, Amniotic Fluid Metabolic: Acidosis, Thyroid disease Anemia

Pleural Space

The pleural space is a potential space between the lung pleura and the chest wall, usually devoid of any significant fluid/substance. Accumulation of exogenous material in the pleural space impedes normal respiratory function.

Air: Tension Pneumothorax, Simple Pneumothorax Blood: Hemothorax

Fluid: Pulmonary Effusion Pus/Infection: Empyema

Chest Wall & Diaphragm

When the chest wall, intercostal musculature or diaphragm is either damaged or non-functioning, the result is breathing impairment. Trauma, neurologic disease and congenital deformity are potential culprits.

Trauma: Flail Chest, Spinal Cord injury, Diaphragmatic Rupture Neurogenic Causes: Guilliane-Barré, Myasthenia Crisis and ALS Congential: Kyphosis, Scoliosis

Cardiac Causes

While many cardiac causes of dyspnea cause pulmonary edema, some cardiac disease increase pulmonary vascular pressures and decrease lung compliance, thus producing dyspnea. These include:

Myocardial Infarction Cardiac Tamponade

Valvular and Congenital Heart Disease

Central Causes

Hypoventilation: over-sedation or CO2 retainers Fever

Psychogenic/Anxiety

HISTORY

Try to ascertain, even in the sickest patients, some historical features of the disease process. Important features of the history are:

Onset of Symptoms Progression of Symptoms Severity of Symptoms

Presence of Associated Symptoms – especially chest pain, fever, cough

Exposure to Noxious Substances Exposure to Allergens

Possible FB ingestions

Past Medical History: This is particularly important as many respiratory and cardiac diseases like asthma, COPD, and CHF have a recurrent course.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical exam can be very revealing and is based on the classic components of the physical examination: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

Once the airway is controlled, the rate and pattern of breathing are important clues to underlying diseases. Tachypnea is usual for most conditions - both intrapulmonary and extrapulmonary. Bradypnea is classic of opiate intoxication (as well as some, usually catastrophic, CNS events). Certain patterns of breathing, (eg. Kussmaul's or apneustic breathing) may be indicators of metabolic and neurogenic causes of respiratory dysfunction. Both hypoxia and hypercarbia may cause agitation, anxiety, and obtundation. Carefully observe the mechanics of breathing such as chest expansion, accessory muscle use, paradoxical breathing, indrawing, and number of words spoken per breath (if applicable). These signs indicate significant respiratory dysfunction and the need for prompt treatment. Cyanosis is a late and ominous sign (except in chronic intrapulmonary and intracardiac shunts). Look for surgical scars over the chest as clues to underlying pulmonary disease and impairment.

Palpation may reveal subcutaneous emphysema over the neck or chest, suggesting pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax. Check the position of the trachea; if it is not midline then something is causing it to shift, such as air, fluid or a mass lesion in the chest. Percussion helps to define what this could be. Hyperresonance is due to air and pneumothorax (+/- tension) is the likely cause. Percussion that is dull may be due to a pleural effusion or a hemothorax.

Auscultation may reveal normal, absent, or diminished breath sounds that help to delineate some of the underlying causes of respiratory dysfunction. Wheezing may be due to bronchospasm secondary to asthma, COPD, CHF or aspirated foreign body. Crackles may indicate CHF, pneumonia or chronic underlying lung pathology. Pleural friction rubs suggest pneumonia or pulmonary embolism.

Although clinical assessment of respiratory function is invaluable, adjunctive tests are often employed. These tests include pulse oximetry, blood gas determination, and pulmonary function testing.

PULSE OXIMETRY

Pulse oximetry provides continuous, immediate and non-invasive assessment of arterial oxygenation. It is of great value at the bedside in rapidly determining the patient‘s oxygenation status, and usually obviates an immediate need for blood gas testing. Pulse oximetry measures hemoglobin saturation, rather than

6 Section One RESUSCITATION

pO2, via spectrophotometric determination of the relative proportions of oxygenated versus deoxygenated hemoglobin in blood coursing through an accessible pulsatile capillary bed (usually the nailbed). Using the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve, it is possible to estimate the pO2 for any given oxygen saturation. An SaO2 of 90% equals a pO2, of 60 mmHg. Below this level of saturation you have hit the steep portion of the curve and pO2 drops off precipitously. For this reason, we strive to keep the oxygen saturation well above 90%.

The accuracy of pulse oximetry is dependent on adequate pulsatile blood flow. Therefore, shock states, severe anemia, hypothermia, and use of vasopressor agents impairs accurate measurements. Jaundice, skin pigmentation and nail polish may also interfere with readings.

INVESTIGATIONS

CBC- looking for evidence of infection or severe anemia Electrolytes- looking for evidence of anion gap acidosis Cardiac Enzymes- in patients with risk factors for ischemia

D-dimer- frequently used to rule out the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism CXR- visualizes many forms of lung pathology

Blood Gas - to assess oxygenation and ventilation

Arterial or Venous Blood Gases

Blood gases are a useful adjunct for a precise assessment of respiratory function, notably providing information on the adequacy of alveolar oxygenation (pO2), ventilation (pCO2), the acid-base status of the patient, and whether the respiratory condition is acute or chronic. Venous blood gases (VBG) provide a close approximation of pH, CO2 and bicarbonate to the arterial blood gas. While arterial blood gases are slightly more accurate, they cause a great deal of pain to the patient and require more time to perform. Therefore a VBG is often measured first and may be sufficient in the clinical asessment.

Pulmonary function tests (PFT)

The most commonly used PFT in the ED is peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). This is easily measured with a hand held peak flow meter, in the patient who is co-operative, to assess the severity of airflow limitation and response to treatment in asthma and COPD. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) is another test sometimes used for this purpose.

ACUTE RESPIRATORY FAILURE

This is defined as hypoxia (pO2<50 mmHg) with or without associated hypercapnia (pCO2>45 mmHg). It is divided into two types:

Type I: respiratory failure without pCO2 retention.

This is characterized by marked V/Q mismatch and intrapulmonary shunting. Examples include diffuse pneumonia, pulmonary edema, ARDS.

Type II: respiratory failure with pCO2 retention.

This involves V/Q mismatch and inadequate alveolar ventilation. There are two categories of this type of respiratory failure:

A. Patients with intrinsically normal lungs but with inadequate ventilation due to disorders of respiratory control (e.g. overdose, trauma, CNS disease), neuromuscular abnormalities (e.g. muscular dystrophy, Guillain-Barre, myasthenia), and chest wall trauma.

B. Patients with intrinsic lung disease with V/Q mismatch and alveolar hypoventilation. Respiratory failure is precipitated by additional clinical insult, usually infection, which worsens the underlying disease. Examples include COPD, asthma, cystic fibrosis.

INDICATIONS FOR INTUBATION

1. Airway Protection

decreased level of consciousness (ie. CNS bleed or overdose) general rule of thumb is ―GCS Eight – Intubate ‖

prevent aspiration 2. Respiratory Failure

this may be a clinical assessment with bedside adjuncts such as pulse oximetry (blood gases NOT necessary to proceed to intubation)

examples include hypoxic OR hypercarbic failure 3. Anticipated Course (Prophylactic Intubation)

ill patient that is CT or O.R.-bound

transfer of critically ill patient to another facility

SPECIFIC TREATMENT MODALITIES

Nasal Prongs

Nasal prongs are usually a well-tolerated method of administering oxygen to the spontaneously breathing patient. With O2 flows of 2-6 L/minute FiO2 of 25-40% can be attained.

Face Mask

Use of a face mask requires a spontaneously breathing patient and can deliver up to 50-60% FiO2 with a flow rate of 10L/minute. This FiO2 may vary depending upon how well the mask fits, and what the patient‘s minute ventilation is; i.e. how much room air is entrained through the mask.

Oxygen Reservoir Mask

Oxygen reservoir mask is essentially the same as the above set-up, except the mask has an attached inflatable bag that stores O2 during expiration and from which O2 is inspired. With a tight fit and low entrainment, FiO2 of up to 90% can be obtained with O2 flow of >10L/minute.

Bag-valve Mask Devices

These masks can be used to manually supplement the patient's respiratory effort in patients who are breathing spontaneously, but require respiratory assistance. The mask comes in various styles with the most common being the ‗AMBU bag‘. It consists of a rubber or inflatable plastic facemask, a connector bag which contains O2, and an O2 reservoir attached to the bag and to the O2 outlet. These devices can deliver up to 100% O2 with high flow O2 and proper bagging procedure. If tolerated, an oral or nasal airway can help facilitate ventilation of the patient.

Bag-valve mask ventilation can temporize patients in respiratory arrest until other therapeutic modalities take effect. However, the majority of patients needing this type of intervention will require intubation and mechanical ventilation. The decision to mechanically ventilate the patient in the ED is usually a clinical one. For patients in severe respiratory distress, do not wait for the blood gas to confirm what you should already know.

CPAP Masks/ BiPAP Masks

CPAP (continuous positive airways pressure masks) are a therapeutic modality option being increasingly used to treat patients in respiratory distress. The commonest and most studied uses are in the patient with CHF or severe COPD. This non-invasive mechanical ventilation

CLINICAL PEARL

temporizes the need for intubation, and may reduce the incidence of patients that need invasive respiratory support.

Other Therapeutic Modalities

Needle thoracostomy can relieve tension pneumothorax prior to chest tube insertion. Tube thoracostomy can relieve pneumo-/hemo- thoraces and drain pleural effusions.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Certain medical therapies may assist in specific diseases. Examples include bronchodilation (ie. salbutamol) in asthma/COPD, diuretics in CHF, antibiotics in pneumonia, anticoagulation/thrombolysis in MI/PE.

Summary

The prompt recognition of respiratory dysfunction, including the respective clinical signs and adjunctive testing, is critical in the ED. Knowledge of specific oxygenation/ventilation and pharmacologic therapies is paramount to prevent further clinical deterioration.

CIRCULATION

OBJECTIVES

1. To recognize shock utilizing the physical examination 2. To understand the causes of shock

3. To review the management of different types of shock

INTRODUCTION

The circulatory system exists in order to supply cells with oxygenated blood and nutrients, and to remove waste products. Shock is defined as ‗an abnormality of the circulatory system causing inadequate tissue perfusion which, if not corrected, will result in cell death.‘

CAUSES OF SHOCK

The circulatory system consists of two pumps connected in series (right and left heart), a system of conduits (blood vessels), and circulating fluid (blood). The causes of shock can be understood by looking at the various components of the circulatory system, and the disorders that affect them. The following table lists some of the circulatory disorders that may result in shock.

The mnemonic ―SSHOCK commonly used for remembering the causes of shock can be‖ reviewed in chapter 43.

RECOGNIZING SHOCK

Shock has many causes, and the clinical presentation varies. However, many features of hypoperfusion can be easily recognized by the bedside examination of the patient.

Mental Status

Early: Agitation due to increased sympathetic tone Late: Obtundation due to decreased CNS perfusion

Pulse

Tachycardia is generally sensitive for acute losses in excess of 12-15% blood volume. Exceptions occur in primary bradyarhythmias, in patients on beta blockers, and in some cases of intraperitoneal bleeding.

The presence of palpable pulses may give a rough indication of systolic blood pressure. If the radial pulse is palpable, systolic pressure exceeds 80mm Hg. If the femoral pulse is palpable, systolic pressure exceeds 70mm Hg. If the carotid pulse is palpable, systolic pressure exceeds 60mm Hg.

Blood Pressure

Hypotension is an insensitive marker for tissue hypoperfusion. In the case of hemorrhagic shock, a fall in blood pressure may not occur until there is blood loss in excess of 30% of total blood volume. (Similarly, hypotension can occur without shock.)

Orthostatic Vital Signs

An assessment of the change in pulse and blood pressure as a patient is moved from a supine to sitting or erect position has been used to identify mild degrees of hypovolemia. There is no consensus as to what changes constitute a ‗positive response‘ and the test is insensitive and nonspecific in the assessment of volume status. Orthostatic vital signs should never be performed in a potentially unstable patient.

Tachypnea occurs in response to increased sympathetic tone and metabolic acidosis. It is an early sign of hypovolemic shock. The tachypneic response may be blunted in response to CNS depressants or head trauma.

Skin

The skin is cool and pale early on as blood is shunted to vital organs. Peripheral cyanosis may

appear later. The exception to this rule is in vasogenic shock, when the skin may be warm and possibly flushed due to peripheral vasodilatation. In later stages of vasogenic shock, depression of cardiac output may cause the usual changes of skin hypoperfusion to become manifest.

Capillary Blanch Test: A positive test occurs when a compressed nail bed takes >2 seconds to

‗pink up‘ and is said to occur when there is acute blood loss in excess of 15% of total blood volume.

Heart Sounds

Muffled heart sounds may be noted in cardiac tamponade. Jugular Venous Pressure

Low: Hypovolemia, Sepsis

High: Left Ventricular Failure, Right Heart Problem

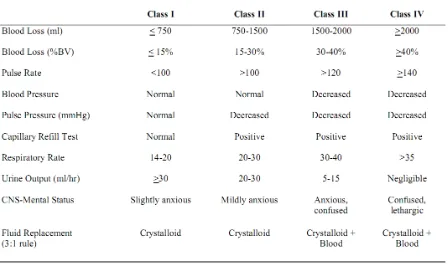

[image:31.595.95.543.380.645.2]RESUSCITATION

Table 2. Assessment of Hemorrhagic Shock According to Presentation

BEDSIDE ULTRASOUND

ED ultrasound can be a useful tool in identifying the cause of shock. It can rapidly detect intraabdominal hemorrhage, hyovolemia (IVC filling), pericardial tamponade, or RV dysfunction (PE).

GENERAL MANAGEMENT ABCs + Monitoring

Cardiac monitor

Intravenous access and send blood to lab (crossmatch if hemorrhage is suspected); Lactate

Control any external bleeding by applying pressure to the wound Foley catheter - monitor urine output

Ongoing assessment of clinical parameters of tissue perfusion include: ◦ Blood pressure, pulse, respirations, level of consciousness, skin ◦ Invasive Monitoring: CVP measurement, Arterial line, ScvO2

SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT Treatment of Hemorrhagic Shock

ABCs

If active control of internal hemorrhage is needed, consult surgery (or occasionally GI) while you resuscitate - don't wait until the patient is stabilized and the blood work is back

Restore circulating blood volume: Prompt restoration of circulating blood volume is felt to be a critical factor in the reversal of shock. In hemorrhagic shock, as in most other types, fluid resuscitation begins with aggressive intravenous infusions of (warmed) crystalloid. Use at least two short, large bore catheters (flow is inversely proportional to the length of the catheter, and proportional to the 4th power of the catheter radius). Pressure infusion devices may be used to increase flow rates. The chart above provides some guidelines for appropriate fluid management.

Peripheral access (preferred):

Equipment: 16-gauge angiocath or larger Sites: forearm, antecubital

Central access:

Equipment: 8FR introducer inserted via Seldinger technique Sites: femoral vein, internal jugular vein, subclavian vein Fluids:

Ringers lactate or normal saline

1-2 litres administered rapidly (20ml/kg in children)

Expect to need approximately 3 times the estimated blood loss (3:1 rule)

Blood (packed RBC‘s):

if no response or transient response to 2-3L fluids

Platelets and FFP

In patients with significant blood loss, early transfusion of platelets and FFP may improve outcome. Many institutions have a ―massive transfusion protocol . ‖

Adequacy of fluid resuscitation is assessed by following the clinical parameters of tissue perfusion as well as urine output. Measurement of central venous pressure may be helpful. Adequate volume replacement is important, but administration of volume in excess of need is harmful. Watch for development of pulmonary edema (cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic).

Under investigation:

SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT NON-HEMORRHAGIC SHOCK

Anaphylactic Shock

Epinephrine (IM; IV if cardiovascular collapse) Intravenous crystalloid Antihistamines (H1 and H2 blockers) Corticosteroids

Wheezing: Nebulized beta2 agonists Stridor: Nebulized epinephrine

Cardiogenic Shock

Inotropes, intra-aortic balloon pump, emergency angioplasty

Tension Pneumothorax

Needle thoracostomy followed by chest tube

Septic Shock

Intravenous crystalloid Antibiotics

Goal directed therapy in the ED decreases mortality in sepsis: urine output >0.5 mL/kg/h

CVP 8 to12 mm Hg MAP 65 to 90 mm Hg ScvO2 >70%

Definitive therapy (drainage of closed space infections, sugery).

Cardiac Tamponade

Intravenous crystalloid, pericardiocentesis

Massive Pulmonary Embolus

Intravenous crystalloid, inotropes, thrombolysis or surgery

Arrhythmias

Specific anti-arrhythmic therapy

SUMMARY

The causes of shock can be understood by looking at the various components of the circulatory system, and the disorders that affect them (pumps, vessels, blood) Many features of shock can be easily identified on physical examination by

assessing mental status, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, skin, jugular venous pressure and capillary refill

Hemorrhagic shock can be classified into 4 categories depending on the estimated amount of blood lost and some of the above mentioned physical examination findings

In fluid resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock, expect to need approximately 3 times the estimated blood loss (3:1 rule)

It is important to rapidly identify the cause of shock and institute specific treatment as soon as possible

REFERENCES

2. Tintinalli J. et al, editors. Emergency medicine: A comprehensive study guide. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011.

3. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 345: 1368, 2001.

Lecture 2 : SEIZURE AND MENTAL CHANGES DISORDER

STATUS EPILEPTICUS IGN Budiarsa

Status epilepticus is defined as a condition in which epileptic activity persists for 30 minutes more.

The seizures can take the form of prolonged seizures or repetitive attacks without recovery in between. There are various types of status epilepticus and a classification :

(Table below)

Status epilepticus confined to early childhood 1. Neonatal status epilepticus

2. Status epilepticus in specific neonatal epilepsy syndrome 3. Infantil spasms

Status epilepticus confined to later childhood 1. Febrile status epilepticus

2. Status in childhood partial epilepsy syndrome 3. Status epilepticus in myoclonic – static epilepsy 4. Electrical status epilepticus during slow wave sleep 5. Landau – Kleffer syndrome

Status epilepticus occurring in childhood and adult life 1. Tonic – clonic status epilepticus

2. Absence status epilepticus 3. Epilepsia partialis continua 4. Status epilepticus in coma

5. Specific form of status epilepticus in mental retardation 6. Syndrome of myoclonic status epilepticus

7. Simple partial status epilepticus 8. Complex partial status epilepticus

In clinical practice status epilepticus classified : A. Convulsive status epilepticus

B. Non convulsive status epilepticus

Principle of management of status epilepticus 1. Lifesaving (ABC)

2. Stop seizures immediately 3. Manage in ICU

COMA AND DECREASE OF CONCIOUSNESS DPG Purwasamatra

Objectives : To diagnosis and manage patients with decrease of conciousness

Conciousness is the state of awareness of the self and the enviroment and coma its opposite, i.e. the total absence of awareness of self and enviroment even when the subject is externally stimulated.

Conciousness is maintened by each cerebral hemisphere with constant prodding from the reticular activating system within the central core of the brainstem tegmentum. Disruption of the reticular activating system or extensive damage to both cerebral hemispheres impairs conciousness.

The five basic physiologic explanation for loss of conciousness are:

Bilateral cerebral hemisphere disease, unilateral cerebral hemisphere lesion with compression of the brainstem, primary brainstem lesion, cerebellar lesion with secondary brainstem compression and non organic or feigned stupor.

Coma, however, is an emergency that the physician must treat before pursuing a diagnosis.

LECTURE 3 : ACUTE PSYCHIATRIC EPISODE Ratep

Objective :

1. To describe etio-pathogenesis and pathophysiology of acute psychiatric episodes 2. To implement a general strategy in the approach to patients with acute psychiatric

episodes through history and special technique investigations

3. To manage by assessing, provide initial management and refer patient with acute psychiatric episodes

4. To describe prognosis patient with acute psychiatric episodes

Emergency occur in psychiatric just as we do in every field of medicine. However, psychiatric emergencies are often particularly disturbing because we do not just involve the body’s reactions to an acute disease state, as must as actions directed against the self or others. These emergencies, such as suicidal acts, homicidal delusions, or a serve in ability to care for oneself, are more likely than medical ones to be sensationalized when they are particularly dramatic or bizarre.

Psychosis is difficult term to define and is frequently misused, not only in the newspaper, movies, and on television, but unfortunately among mental health professionals as well. Stigma and fear surround the concept of psychosis and the average citizens worries about long-standing myths of mental illness, including psychotic killers, psychotic rage, and equivalence of psychotic with the pejorative term crazy. Aggressive and hostile symptoms can overlap with positive symptoms but specifically emphasize problems in impulse contro

For example, a mother killing her five children in the belief that they are inhabited by Satan, a famous poet killing herself, the delusional murder of legendary musician, the son of prominent family found wondering confused and malnourished in a city park, all of these are psychiatric emergencies that can and up on the front pages of newspaper.

Psychiatric emergencies occur everyday to people. Psychiatric emergencies arise when mental disorders impair people’s judgment, impulse control, and reality testing. Such mental disorders include all the psychotic disorders, manic and depressive episodes in mood disorders, substance abuse, borderline, and antisocial personality disorders and dementias. There may also be emergencies related to particularly severe reactions to psychiatric medications, such as neuroleptic malignat syndrome or acute granulocytosis, that must be recognize, diagnosed and treated immediately.

LECTURE 4 : ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME AND FAILURE

ARDS is an emergency in the lung area due to disturbance in alveolocapiler membrane permeability by a number of thing causing liquid accumulation/build up inside alveoli or bronchus oedema. While ARF is a kind of ARDS complication which is a distability of lung to do respiration function causing accumulation of CO2 and decrease in O2 inside the

artery. Incident of ARDS is high. In the USA, 150.000 cases were found per year and 50% of them died due to breathing failure.

Diagnosed based on : complaint, sudden breathing difficulties, coughing, tiredness and decrease in consciousness and usually preceded by basic illness and triggering factors. On the thorax photo it was found infiltrate diffuse in the two lungs region, while in ARF depend on basic illness. The important thing is examination of blood gas analyses where there is a decrease on PaO2 until below 50 and PaO2 above 50 or refer to as rule of fifty.

Principle of procedure is to give the Oxygen, CO2 removal either with or without

ventilator, liquid restriction, clearing of breathing pathway, overcoming obstruction using bronchodilator, etc.

Learning Objective

Students are able to describe pathogenesis, to set diagnoses, propose examination, give medication and evaluate ARDS and ARF patients.

ACUTE UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Wayan Sucipta,

Abstract

Acute upper airway can result from a variety of disorders including trauma, neoplasm, infection, inflammatory process, neurologic dysfunction, presence of a foreign body.

Affected site can include the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx and trachea.

Emergency airway management principles include the determination of the site and degree of obstruction, airway control by ventilation, intubation or surgical bypass of the obstructed site with a crico thyroidectomy or tracheostomy and treatment of the precipitating cause of obstruction.

NEONATAL RESUSCITATION and ELECTROLITE IMBALANCE

Diah Kanyawati

Abstract

Ninety percent of asphyxia insults occur in the antepartum or intrapartum periods a a result of placental insufficiency. After delivery, the baby’s ineffective respiratory effort and decrease cardiac output. Hypoxic tissues begin anaerobic metabolism, producing metabolic acids that are initially buffered by bicarbonate.

The incidence of perinatal asphyxia usually related to gestational age and birth weight. The basic goal of resuscitation are : to expend the lungs and maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation, to maintain adequate cardiac output and tissue perfusion. Neonatal resuscitation equipment and emergency medications should be immediately available.

RADIOLOGY

Learning Objective

At the end of meeting, the student will be able to :

1. Describe the radiology imaging of thorax photo for IRDS (Idiopathic Respiratory Distress Syndrome) case, Bronchopneumonia, CHD, Pericardial Effusion, Lung Edema, Pneumothorax, Pleural Effusion, Vena Cava Superior Syndrome.

2. Describe the imaging of abdominal plain photo in : Illeus Obstruction, Paralytic Illeus, Stone in the Urinary Bladder, Peritonitis, NEC, Cholelithiasis & Acute Cholecystitis.

LECTURE 5 : BLEEDING DISORDER

HEMORRHAGE IN PREGNANCY : ANTEPARTUM AND POST PARTUM

Wayan Megadhana

ANTEPARTUM HEMORRHAGE

Objectives :

1. Recite the incidence of antepartum hemorrhage 2. List the etiology of antepartum hemorrhage

3. Distinguish the differences in the diagnosis of placenta previa and abruption placenta

4. Apply the principles of fetal and maternal stabilization in the management of anterpartum

Antepartum haemorrhage (APH) is defined as bleeding from or in to the genital tract, occurring from 28 weeks of pregnancy and prior to the birth of the baby. The most important causes of APH are placenta praevia and placental abruption, although these are not the most common. APH complicates 3–5% of pregnancies and is a leading cause of perinatal and maternal mortality worldwide.Up to one-fifth of very preterm babies are born in association with APH, and the known association of APH with cerebral palsy can be explained by preterm delivery. Bleeding during various times in gestation may give a clue as to its cause. Uterine bleeding, however, coming from above the cervix, is concerning. It may follow some separation of a placenta previa implanted i