Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:50

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Contexts for Communication: Teaching Expertise

Through Case-Based In-Basket Exercises

James M. Stearns , Kate Ronald , Timothy B. Greenlee & Charles T. Crespy

To cite this article: James M. Stearns , Kate Ronald , Timothy B. Greenlee & Charles T. Crespy (2003) Contexts for Communication: Teaching Expertise Through Case-Based In-Basket Exercises, Journal of Education for Business, 78:4, 213-219, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309598603

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309598603

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 17

View related articles

Contexts for Communication:

Teaching Expertise Through Case-

Based In-Basket Exercises

JAMES M. STEARNS

KATE RONALD

TIMOTHY B. GREENLEE

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Miami

UniversityOxford, Ohio

CHARLES T. CRESPY

University of Texas, El Paso

El Paso, Texas

ommunication contexts and tech-

C

nologies have become so sophisti- cated and pervasive that effective writ- ten communication is essential to success for managerial personnel at all levels of the organization. Because of the increased importance of written communication, calls for a managerial workforce that writes well have come from a variety of academic and practi- tioner stakeholders. Higher education accrediting agencies have mandated the integration of communication skills, both oral and written, in curricula. Sur- veys of academics, practitioners, and recent graduates have all identified writ- ten communication as both a high prior- ity and the area that needs the most improvement.Scholars have responded to such crit- icism with a new emphasis on writing across the curriculum and many skill development initiatives. What is striking about all of these efforts is the unanimi- ty of concern and the cooperation among disciplines and institutions, both within and outside of academe. In this article, we discuss one powerful tool for improving student writing. Case-based in-basket exercises (CIBEs) challenge students to write for a variety of purpos- es and to a range of audiences in busi- ness contexts. These exercises not only offer students the opportunity to prac- tice the kinds of writing that profession-

ABSTRACT. Stakeholders from both business and academe are challenging educators to integrate meaningful writing into the business curriculum.

In

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

this article, the authors describe theuse of case-based in-basket exercises (CIBEs) as a particularly effective way to elicit such writing. CIBEs require students not only to master course concepts but also to learn how to communicate what they know to a variety of professional audiences beyond the classroom. CIBEs require students to combine specialized func- tional area knowledge with analysis of communication contexts; thus they lead students to expertise, or the abili- ty to adapt disciplinary content to var- ied audiences and purposes.

als use every day but also show students how to translate their disciplinary learn- ing into meaningful action that requires sophisticated analysis of context, audi- ence, purpose, and knowledge. In other words, CIBEs help students manage the contexts in which their developing dis- ciplinary knowledge will be needed.

Forces Behind Efforts to Improve Written Communication

The Association to Advance Colle- giate Schools of Business-International (AACSBI) and its predecessor the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) have been powerful forces in the drive to

improve written communication in busi- ness curricula. The AACSB re-empha- sized written communication as a key element of undergraduate education in 1994. Other stakeholders have corrobo- rated this concern and supported this initiative. Lee and Blaszczynski (1 999) reported that Fortune 500 executives perceive an increase in the relative importance of communication skills as compared with functional area exper- tise. Moody, Brent, and Bolt-Lee (2002) provided evidence that corporate recruiters consistently place written communication at the top of their crite- ria in selecting job candidates (pp. 23-24). Recruiters strongly advise busi- ness faculty to “prepare [students] more to work and communicate with others rather than strictly with books” and “bring in as much ‘real life’ business experience to the class as possible. Teach to communicate well, reason well” (p. 29).

Organizational action also corrobo- rates the concern of academics and prac- titioners. Many firms, such as Ford and Procter and Gamble, use written com- munication exercises as part of the inter- viewing process. These exercises are designed to determine individuals’ abili- ty to function in the corporate culture by measuring their capacity to communi- cate effectively with different levels of

the organization (Barclay &

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

York, 1999).zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MarcWApril2003 213

Technical Writing Expertise and Content Knowledge Are Not

Enough

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Scholars have described a myriad of methods for placing more emphasis on communication through the integration of writing into the functional business

disciplines (Carnes, Jennings, Vice,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&Wiedmaier, 2001; Hansen & Hansen, 1995; Holter & Kopka, 2001; Peterson, 1997; Plutsky &Wilson, 2001; Riordan, Riordan, & Sullivan, 2000). These

2001). Zorn (2002) argued that business

students should “work toward

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

expertisein a topic, not just a discipline” (p. 44, emphasis added).

Academic writing researchers have translated this pressure from constituent groups into major research projects.

Worlds Apart: Acting and Writing in Academic and Workplace Contexts

(Dias, Freedman, Medway, & Pare, 1999) documented the chasm that even successful student writers have to cross to write well in professional settings.

~ ~ ~~~

Research on writing and writing instruction has

shown for decades that skills taught in isolation,

through exercises, or out of context do not last

and do not transfer to other writing situations.

efforts, however, have addressed only partially the issues of (a) how one defines and measures the relevant dimensions of effective written commu- nication and (b) what framework under- pins the integration process.

After entering the workforce, man- agers soon find that technical writing expertise and content knowledge of a functional discipline, although neces- sary, are not sufficient for effective communication in complex organiza- tions. This realization is manifest in observations about academic writing and job-related writing. For example, Rubin (1996) argued that communica- tion is “much more than expressing the content o f .

.

.

business disciplines” and “is integral to the process of problem solving in the team-oriented workplace” (p. 7). Catanach and Golen (1996) maintained that previous research and recommendations by accounting educa- tors regarding the development of writ- ing skills are of limited use because of the narrow focus. Catanach and Golen asserted that users of accounting infor- mation often are not accountants and that audience, or a “user-orientation,’’ should be an important component in the evaluation of the writing skills of accountants (see also Borzi & Mills,The authors concluded their survey and case study research with the statement that “the writing abilities of students graduating from universities are increasingly in question when they move into the workplace” (p. 5). Dias et al. attributed this mismatch to the differ- ences between writing as an education- al activity and writing as a rhetorical action in professional settings. In other

words, in the educational setting, stu- dents write largely to say something or to report their knowledge; in the work- place, professionals write in order to do something, to persuade with their knowledge. Worlds Apart suggested that

educators could help students “experi- ence the practitioner’s rhetorical life” by devising writing activities that more closely resemble the purposeful action of workplace communication (p. 226).

Research on writing and writing instruction has shown for decades that skills taught in isolation, through exer- cises, or out of context of meaningful discourse (with an audience, purpose, and a style and form suitable to that audience and purpose) do not last and do not transfer to other writing situations. Although business academics have been slow to react, experts in business writing have long called for attention to context

in writing. Tebeaux (1985) argued that the most important factor in acquiring the skills of business writing is an “emphasis on adapting communication to various audiences” and the develop- ment of assignments that “require stu- dents to place their writing in an organi- zational context and to make deliberate choices about strategy, style, and tone when they address an audience for a par- ticular purpose” (pp. 423-424). Such choices depend on particular contexts, such as organizational hierarchy, the audience’s functional expertise and per- spectives, and the writer’s intended mes- sage, which may exist on several levels at once. Zachry (2000a) suggested that the communicative action be viewed as a “set of practices embedded in a larger sociohistorical network of activities” (pp. 97-98). We believe that, to be suc- cessful, managers must be able to recog- nize and manage the communication context-the audience, purpose, form, style, and tone.

Yet conventional advice about busi- ness writing tends to rely on standard examples and maxims without taking shifting and multilayered contexts into account. Brady (1993) described con- ventional advice about writing in busi- ness as “templates for situations that will never be replicated” and that dis- courage students from looking beyond the textbook toward “seeing subtle ways that texts are inflected with many voic- es” (p. 454). This reliance on textbook examples and conventional advice has its roots in the division between acade- mic and real-world conceptions of the relationship between writing and learn- ing. Academic advice about learning to write has traditionally relied on imita- tion of standard forms and examples in which the “content” or information in the writing simply exists to fill up the form that students practice.

In Worlds Apart, Dias et al. (1999)

argued that “learning to manage the relationships” within organizations and disciplines remains the crucial task for novice professionals. At the same time, academic writing has been confined too often to exercises, such as essay exam answers or research reports, that address the teacher as the sole audience and whose primary purpose is the demonstration of knowledge, not com-

21 4 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessmunication. Traditionally, writing is modeled in academic settings as the container or package for the content or knowledge that students acquire in their courses. Information is put into writing according to prescribed formulae and rules learned through imitation. In the last decade, however, researchers in composition and professional writing have begun to suggest another model for academic writing: immersion in contexts that approximate real writing

situations.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A Tool for Integrating Business Writing and Business

Knowledge: The Case-Based In-Basket Exercise

A useful vehicle for helping students gain experience in communicating their knowledge to diverse audiences in var- ied contexts is the case-based in-basket exercise (CIBE). CIBEs differ from tra-

ditional in-basket exercises (Barclay

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&York, 1999; Castlebeny, 1990) in the richness and level of information pro- vided to the student. CIBEs include a case-study-like “front end” that places the student in a mid- or upper level man- agement role for a particular company, at a specific point in time, and presents him or her with a series of memos from superiors, subordinates, and peers. The exercise places the student in a scenario that provides significant information

about the formal and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

informal organiza-tion. The student knows specifics regarding the corporation’s culture, its business threats and opportunities, its idiosyncrasies, competition within the industry, the functions of the jobs per- formed by co-workers to whom the stu- dent is to respond, the strengths and weaknesses of the individuals to whom he or she is required to respond, and sig- nificant details about the role that he or she is being asked to assume.

Acting as experts, students must put what they have learned into action in different contexts in which different people require different interpretations and answers from them. Students must make decisions, answer questions, and recommend alternatives; therefore, they need to know more than simply how to perform an accounting, finance, man- agement, or marketing function. For

example, rather than merely performing

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

a statistical test, students must know how to communicate results, recognize subtleties, teach subordinates, and use results rhetorically.

Circle K Stores (see Appendix) is an example of a CIBE designed for a mar- keting research or marketing analysis course. This exercise requires the stu- dent to respond to various audiences, with varying purposes and in different contexts, by using functional discipline- based knowledge. Simply knowing how

the form of communication almost always involves presentation.

The type of CIBE illustrated by Circle K Stores is very effective in responding to some of the major criticisms of busi-

ness education and business writing. Requiring that students contextualize their analytical skills by writing solu- tions, suggestions, and directives to “real” audiences in memo form (elec- tronic or hard copy) helps students see writing as a real-world skill with conse- quences that affect their success as man-

~~

Requiring that students contextual ize their

analytical skills by writing solutions, suggestions,

and directives to “real” audiences in memo form

(electronic or hard copy) helps students see

writing as a real-world skill with consequences

that affect their success

to write correctly, in conventional forms, will not be enough to deal with the mClange of requests and information in Circle K Stores. (We include a sam- ple memo in the Appendix. Many dif- ferent memos from several different organizational members are available in the typical CIBE. Please contact the authors for details.)

For the purpose of accomplishing the kinds of objectives set out by Dias et al. (1999), Moody et al. (2002), Rubin

( 1996), Catanach and Golen (1 996), Forman and Rymer (1999), Zachry (2000b), and Zorn (2002), CIBEs are superior to simple in-basket exercises and written case analyses for several reasons. CIBEs provide more organiza- tional and individual information than do simple in-basket exercises, which tend to focus on prioritizing and dele- gating. In-basket exercises force stu- dents to consider the audience for their writing but are limited in context and ability to “involve” students in rhetori- cal situations in which they take on a stakeholder’s role. Written case analy- ses provide great detail about context, but the “audience” for case write-ups is usually artificial and limited only to the course instructor. When live cases or practitioners are used in case analyses,

as managers.

agers. Combining analytical skill with contextual problem solving, in writing, translates into expertise, which we describe as the combination of rhetorical and content knowledge.

ClBEs and the Nature of Expertise

In her comprehensive study Academ-

ic Literacy and the Nature of Expertise,

Geisler (1994) suggested that CIBE activity in a discipline distinguishes an expert from a novice. Geisler defined an expert as someone able to abstract from what she calls “domain content representation.” In other words, exper-

tise involves understanding the princi- ples underlying and overarching any particular discipline. But the ability to abstract is not enough to produce an expert; novices, too, learn abstract prin- ciples, such as statistical formulae or the concept of statistical significance used in Circle K Stores. An expert, Geisler posited, also possesses the abil- ity to “adapt abstractions to case specif-

ic data” (p.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

85). Together, these twoabilities-abstraction and applica- tion-lead to expertise. However, there is yet another connecting factor- rhetoric.

MarcWApril2003 21 5

Expertise is divided into two areas: domain content and rhetorical aware- ness. In other words, it is not enough to know one’s subject or be able to relate abstractions to specific cases; one must also know how, when, where, and why to communicate that knowledge and to whom one is communicating. (As should be clear by now, a simple way to

describe the concept would be to say that

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

context is always part of the acquisition of knowledge.) Most students develop “domain content” expertise-the ability to work with an increasing number of abstract representations of the “problem space” of disciplines-during their un- dergraduate years. But they are not yet experts because during this time the “rhetorical problem space remains basi- cally naive” and “knowledge still has no rhetorical dimension” (Geisler, 1994, p. 87). For example, a student may com- prehend the concept of cost-benefit analysis or Bayesian value of informa- tion (expected value), but he or she may still be unable to use these concepts effectively to convince a higher-level person in the organization that a research study should or should not be done.

Geisler blamed academics’ tendency to present (and view) texts (and text- books-the primary source of knowl- edge in formal education) as auton- omous, existing without context and impervious to critique, as containers of information with no agenda of their own. Students tend to view their profes- sors, lectures, and classes in much the same way-as autonomous sources of knowledge. However, usually sometime after undergraduate school-either on the job or in graduate studies-students begin to see texts and sources different- ly, as documents in context, with claims that can be argued and refuted and styles that tell much about hierarchical

relationships. As Geisler stated,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The emergence of an expert representa- tion of the rhetorical problem space is the final stage in the acquisition of expertise.

For it is only when both the domain con- tent and the rhetorical processes of a field

are represented in abstract terms that they can, together, engage in the dynamic

interplay that produces expertise.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

. . .

Expertise, then, becomes a knowing thatlinked to a knowing how” (pp. 87, under- score added).

It is not enough, then, to learn the ab-

stract concepts and tools of a discipline (knowing that); one must be able to use, apply, and communicate that knowledge in particular contexts (knowing how, why, when, and for whom).

CIBEs are a valuable tool for devel- oping expertise in students by having them practice the application of not only content but also judgment regarding how best to communicate. Andrews (1999) argued that faculty members can help students understand their roles as writers in organizations by “asking them to play that role in class’’ and giv- ing them “experience in crafting docu- ments within settings” (pp. 7-8). The CIBE in the Appendix, Circle K Stores, is one of several examples that we have used successfully as a practice exercise and as a testing instrument in a market- ing analysis course. Circle K Stores places the student in the role of a mar- keting vice president who must respond to a series of memos involving typical scenarios that a decision maker in such a position could expect to encounter. Scenarios are varied and include the interpretation of statistical analysis (see the example memo at the end of Appen- dix), the design of an appropriate research study, financial analysis and interpretation of parameters, and the construction of an agenda for a staff meeting. These memos originate from various levels within the organization and from co-workers with varying degrees of understanding of research and analysis. In their responses, stu- dents are expected to recognize the sub- tleties of the context and the relevant discipline principles-in other words, how, when, why, and for whom.

As an example of the level of exper- tise expected of students completing a CIBE, we can consider the “Urban Store Operating Hours” memo included in the Circle K Stores CIBE. The memo, sent by the subordinate employee Dale, places the student decision maker in the position of addressing the safety con- cerns of employees with respect to rob- beries at urban stores. The student is presented with three distinct issues in the memo, two related to analysis (knowing what) and one related to com- munication (knowing how). First, the student must interpret the statistical evi- dence from a sample of urban stores

closed during late night hours to deter- mine if the store closings reduce rob- beries. Second, the student must assess Dale’s claim that the closing of the urban stores during late night hours would be financially insignificant. Thus, the student is required to (a) ana- lyze the sample evidence for statistical and managerial significance through hypothesis testing and probability val- ues and (b) assess the financial impact of the potential store closings.

Third, after completing the analysis, the student decision maker must com- municate his or her information to Dale in a manner that not only addresses Dale’s concerns and level of under- standing but also provides a possible solution to the current situation. In this situation, the decision maker must rec- ognize that Dale is caught between two levels of the organization. Moreover, some of Dale’s store managers harbor resentment and strong emotions. The socially responsible alternative may not be the one that maximizes profit in this situation, and the student must consider Dale’s dual roles as an advocate for store managers and as a representative of the “home office.” We provide a sam- ple response memo at the end of the Appendix.

The response given in the sample memo at the end of the Appendix does an excellent job: It demonstrates use of analytic and inferential statistical tools, study of the financial implications in the situation, and addressing of the con- cerns of the store managers and Dale Duville. Also, the response gives Dale a specific task (“investigate better securi- ty”), is empathic (“close the stores in those markets”), and allows for more discussion of the issue (“Let’s talk more at the staff meeting”).

Students’ responses to this exam also demonstrate that they are learning expertise. Although the CIBE exam has taken on almost legendary status among the students as one of the most difficult assignments of their academic careers, they understand that it teaches them to integrate functional and rhetorical knowledge. The following is a small list of responses given by students when asked by writing experts, not course instructors, what they learned from

completing the CIBE:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

21 6 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessThis exam really helped me to under- stand the importance of audience in writ- ing. Tell your audience what they need to know. Make sure you are clear about your decision and, obviously, support it.

The exam gives you the impression that you have some sort of power. Put- ting myself in a position of authority and writing from that position really helped me apply course concepts in order to make decisions.

I really feel that I’m going to be

doing something like this, and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I need toknow how to make decisions in writing and back them up. This exam is more relevant to the real world than most other tests would be.

I had to think about my sentence structure when writing these memos. I had to make sure that my writing was concise and that I said just what needed to be said.

Writing from a VP’s perspective and

responding to different people in differ- ent departments of a company really helped me understand how everything is so integrated in the business world.

In my profession I will always be

writing memos. I learned from this exam how important it is to know to whom you are talking and to get right to the point.

If you want to do well on this exam, you have to get into your head that you

are a marketing executive.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Conclusion

Educators no longer can ignore the need to integrate meaningful writing into business curricula. This need is well documented by the experiences of a variety of stakeholders. The objective of this integration should be more than a series of writing-across-the-curriculum programs and exercises that merely have students write more or technically better. We should strive to develop man-

agers with

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

expertise. Thus, we mustdevelop exercises that vary the audience for and the context surrounding stu- dents’ business writing and that force them to recognize and deal with these two elements. Essay exams, written case analyses, simple memo writing and in-basket exercises, research reports, and projects are not enough. The CIBE

allows a student to use all of his or her resources-subject knowledge, audi- ence knowledge, context knowledge, rhetorical knowledge, and basic writing skill-to deal with complex managerial decision making situations.

Although the costs of introducing CIBEs in any business course are signif- icant, faculty members must consider the challenges that our constituents have put before us. The AACSBI is demand- ing a better job of integrating written communication into the business cur- riculum. Industry uses CIBE-like instru- ments to evaluate and hire our students. Twenty-first century organizations de- mand managers with sophisticated and adaptive skills. For these reasons, we must look to the sound theoretical bases provided by learning and writing schol- ars. Much of effective management requires persuading and/or inspiring oth- ers. Today, knowing how to achieve such ends beyond simple communication of ideas is essential for advancement in organizations. CIBEs compel students to develop and use true expertise.

REFERENCES

Andrews, D. (1999). No right answer. Business

Communication Quarterly, 62(4), 7-8.

Barclay, L. A.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& York, K. M. (1999). Electroniccommunication skills in the classroom: An e- mail in-basket exercise. Journal of Education

for Business, 74(4), 249-253.

Borzi, M.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

G., & Mills, T. H. (2001). Communica-tion apprehension in upper level accounting students: An assessment of skill development.

Journal of Education f o r Business, 76(6), 193-1 97.

Brady, L. (1993), A contextual theory for business writing. Journal of Business and Technical

Communication, 7(October), 45247 1. Carnes, L. W., Jennings, M. S., Vice, J. P., & Wei-

dmaier, C. (2001). The role of the business edu- cator in a writing-across-the-curriculum pro- gram. Journal of Education for Business, 76(4), 2 1 6-2 19.

Castleberry, S. B. (1990). An in-basket exercise for sales courses. Marketing Education Review, Catanach, A. H., & Golen, S (1996). A user-ori- ented focus to evaluating accountants’ writing skills. Business Communications Quarterly, 59(4), Ill-121.

Dias, P, Freedman, A., Medway, P., & Pare, A. (1999). Worlds apart: Acting and writing in

academic and workplace contexts. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Forman, J. & Rymer, J. (1999). Defining the genre of the ‘case write-up.’ Journal of Business

Communication, 36, 103-1 33.

Geisler, C. (1994). Academic literacy and the

nature of expertise: Reading, writing, and knowing in academic philosophy. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hansen, R. S., & Hansen, K. (1995). Incorporat-

I , 51-55.

ing writing across the curriculum into an intro- ductory marketing course. Journal of Marker-

ing Education, 17(1), 3-12.

Holter, N. C., & Kopka, D. J. (2001). Developing a workplace skills course: Lessons leamed.

Journal of Education f o r Business, 76(3), Lee, D. W., & Blaszczynski, C. (1999). Perspec-

tives of “Fortune 500”

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

executives on the com-petency requirements for accounting graduates.

Journal of Education f o r Business,

74(2), 104-107.

Moody, J., Brent, S., & Bolt-Lee, C. (2002). Showcasing the skilled business graduate: Expanding the tool kit. Business Communica-

tion Quarterly, 65(1), 21-36.

Peterson, M. S. (1997). Personnel interviewers’ perceptions of the importance and adequacy of applicant’s communication skills. Communica-

tion Education, 46, 287-29 1.

Plutsky, S. (1996). Faculty perceptions of stu- dents’ business communication needs. Business

Communications Quarterly, 59(4), 69-76. Plutsky, S., & Wilson, B. (2001). Writing across

the curriculum in a college of business and eco- nomics. Business Communication Quarterly, 64(4), 26-41.

Riordan, D., Riordan, M., & Sullivan, M. (2000). Writing across the accounting curriculum: An experiment. Business Communication Quarrer-

ly, 63(3), 4 9 4 9 .

Rubin, J. R. (1996). New corporate practice, new classroom pedagogy: Toward a redefinition of management communication. Business Com-

munication Quarterly, 59(2), 7-19.

Tebeaux, E. (1985). Redesigning professional writing courses to meet the communication needs of writers in business and industry. Col-

lege Composition and Communication, 36, 419-428.

Zachry, M. (2000a). Conceptualizing communica- tive practices in organizations: Genre-based research in professional communication. Busi-

ness Communication Quarterly, 63(4), 95-101. Zachry, M. (2000b). Communicative practices and

the workplace: A historical examination of genre development. Journal of Technical Writ-

ing & Communication, 30, 57-79.

Zorn, T. (2002). Converging within divergence: Overcoming the disciplinary fragmentation in business communication, organizational com- munication and public relations. Business Com-

munication Quarterly, 65(2), 44-53. 138-141.

APPENDIX

Authors’ note. This CIBE is partially based on “Circle K Pushes for a New Look at Convenience Stores,” Wall Street Journal, November 6, 1995, p. B4.

Circle K Stores

6454 Convenience Way

Phoenix, Arizona 84206

The Competitive Environment

The convenience store industry has been a roller coaster ride in the last decade. In the early 1990s, three of the largest competitors were operating under bankruptcy protection after posting stag-

gering loses. Things have stabilized in

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MarcwApril2003 21 7

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

the last

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 years, but only after thousandsof store closings, tens of thousands

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

oflayoffs, and major debt restructuring. The current convenience store market can be characterized as mature and stag- nant. Industry sales total $132 billion. Management Horizons, the consulting arm of Price Waterhouse, estimates growth to be less than 1% per annum through the year 2005. The “big three” include the Dallas-based Southland Corp., which operates 5,500 7-Eleven stores; Circle K Corp. of Phoenix, with slightly less than 2,500 stores; and National Convenience of Houston, with about 1,000 stores in the south. The industry faces threats from gas stations, drugstores, and even discount stores, all of which now offer services similar to those of convenience stores. For exam- ple, Walgreens and Wal-Mart are selling more food and are showing signs of competing more directly for conve-

nience store patrons.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Circle

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

K

CorporationCircle K was in bankruptcy when it hired John Antioco from Southland Corp. as President and CEO in 1995. With the company bloated from a rapid and expensive expansion binge, Mr. Antioco was faced with eliminating 2,000 stores and finding a way to reju- venate a slumbering Circle K. After streamlining operations, Mr. Antioco managed to raise $400 million from the Bahrain-based Investcorp SA. With this infusion of fresh capital, Circle K expe- rienced a dramatic turnaround in the late 1990s. Sales starting in fiscal 2000 rose to $3.9 billion, from $3.6 billion in 1999. Net income also was in the black; in 1999 it was $23.6 million, and in 2000, $27.5 million. Gross margins are roughly 20%, whereas net return on sales is slightly less than 1%. The final data are not in yet for 2001, but analysts speculate that results should be slightly better than those for 2000.

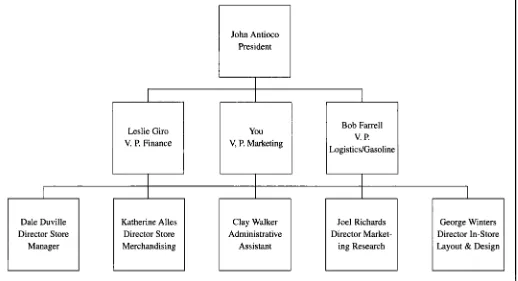

You were with Mr. Antioco at South- land as Director of Marketing. One of the first things Mr. Antioco did was lure you to Circle K to be the National Vice President of Marketing (see Organiza- tion Chart). He has great confidence in your ability to read situations and clear- ly identify marketing problems and opportunities. This confidence is largely

21 8

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal ofzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Education for Businessbased on your expertise in data evalua- tion, data interpretation, and marketing research. Mr. Antioco relies almost completely on you in these matters, as most of his time is spent dealing with financial problems, public relations, and looking for acquisition opportunities.

One of the first changes that you introduced after coming over from Southland was the remodeling of stores away from the full, drab convenience store look. In the last 2 years, all Circle

K stores have been spruced up with new paneling and miniature departments. Stores are now divided into areas labeled “Snack World,” “Grocery Ex- press,’’ “Dairy Land,” and other catchy phrases. At the much-visited coffee area, metal dispensers have given way to glass pots, a move that has helped increase monthly coffee sales from $500 per store 4 years ago to an esti- mated $1,600 last year. Also, per-store customer counts estimated to be 800 a day, up from 450 a few years ago.

Major Initiatives

Circle K is looking at three major changes in the immediate future: (a) the introduction of Unocal 76 brand gaso- line in 400 of its stores, (b) the opening

of several free-standing Emily’s Meals

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& More stores, considered to be a high- risk proposal, and (c) the restricting of hours in urban markets.

Emily’s Meals & More is a take-out restaurant that includes hot entrees and desserts. The Emily’s idea has been championed by Katherine Alles, the Director of Store Merchandising.

The notion of restricting hours in urban markets is a response to high lev- els of crime in these stores between midnight and 6:OO a.m. Circle K has had hundreds of robberies in urban stores, and, tragically, two store clerks were murdered during these hours in the last 12 months. There are 814 stores located in urban markets; the remaining stores are classified as being either suburban or rural. Store managers believe that closing certain stores from midnight to 6:OO a.m. would reduce the probabilities of robberies and physical harm to employees. Historically, Circle Ks have remained open 24 hours a day, 364 days a year (closing only on Christmas Day).

Store Information

Typical stores cover 2,400 square feet and 85% of them sell gasoline, which represents half of total corporate sales but only one quarter of operating profit. An experiment that has not proven to be successful was the introduction of a store brand name for gasoline. In the last 3 years, Circle K has tried “2-2000”

and “Performazene” without much suc- cess. Currently, Bob Farrell handles all aspects of gasoline logistics. This had become such a challenging task that Bob’s position has been elevated to that of corporate vice president. Bob works independently of much of the staff. He keeps close ties with major gasoline wholesalers and is working jointly with you on the new Unocal project.

Unfortunately, more of your time in the last 2 weeks has been spent advising Mr. Antioco in a failed attempt to acquire United Convenience Stores of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Mr. Antioco was particularly disappointed because this acquisition would have strengthened Circle K’s position in one of its weaker regional markets, the upper Midwest.

Upon returning to Phoenix, you find several important memos from Circle K’s marketing directors in the corporate offices (see Figure 1 for the organization chart). Mr. Antioco wants to have a mar- keting department staff meeting before Passover-preferably Tuesday, April 8

-so you need to respond to the memos and establish an agenda for the meeting to secure his final approval on any action. Mr. Antioco was quite upset and has seemed a little testy since the acqui- sition failed, so you are concerned that his time not be wasted in the meeting.

Circle K Stores 6454 Convenience Way Phoenix, Arizona 84206 April 1,2002

To: You

From: Dale Duville, Director of Store Managers

Re: Urban store operating hours

I really need some help with the store managers concerning the operating hours of our urban stores. Many of the managers have personally been in-

V.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

P. Finance V, P. Marketing Logistics/GasolineLeslie Giro

V. P. Finance V, P. Marketing

Logistics/Gasoline

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

:

Dale Duville Director Store [image:8.612.50.568.51.332.2]Manager

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

FIGURE 1. Organization chart: Circle K Stores, inc.

Clay Walker Joel Richards Administrative Director Market-

Assistant ing Research

George Winters Director In-Store

I

Layout & Designvolved in robberies. Several of them are frightened. The managers are convinced that the “home office” (you and Mr. Antioco) are concerned only about sales per square foot, turnover, margins, and the company bottom line. I am not sure

whether their fears are justified, but their feelings seem genuine. They want themselves and their employees safe, and I can’t really argue with that. This

issue has the potential to undermine everything I am trying to do.

Historically, 32% of our urban stores

have been robbed at least once a year. As you know, we randomly selected 38

urban stores last year and closed them between midnight and 6:OO a.m. to see if robberies would decline. We have now run this test for a year and the pro- portion of stores that were robbed was only 24%. Because this is only a sam-

ple, could this finding be a fluke? Can you help me with the interpretation of these findings? If we have good evi- dence that there are fewer robberies, we may want to initiate this policy (closing stores between midnight and 6:OO a.m.) in all of our urban stores. We only do about 7% of daily sales between mid- night and 6:OO a.m., so the financial impact really would not be that great.

Sample Memo From Student Decision Maker

To: Dale Duville, Director of Store Managers

From: Student Decision Maker Re: Urban Store Operating Hours

Thanks for reporting the results of our test investigating the percentage of stores that were robbed. Mr. Antioco and I are very concerned about the

safety of our store clerks and man- agers. We would never place revenues or profit above their safety and securi- ty. I trust you will communicate that to

them.

The results provided by your sample could be a “fluke,” but it is not likely. Given the sample size (38 stores) and

the sample percentage of stores robbed

(24%), the likelihood is relatively small

that the percentage of stores whose hours have been reduced and that are being robbed will still be 32% (. 14 prob.

value). Thus, the percentage of stores being robbed would probably be less than 32% when the stores are closed between midnight and 6:OO a.m. We

have some evidence that our strategy of closing stores during those hours is working.

What I do not agree with is that “the financial impact is really not that great.” If each of our urban stores does 7% of its sales between midnight and 6:OO a.m., that means that those sales are slightly more than $300 per night.

That generates approximately $88.8

million in sales per year and approxi- mately $17.7 million in margin. Thus, this decision carries a very large financial impact. We are assuming that urban stores do “average” sales during those hours. Those stores may in fact do more given the nature of those markets.

We would never compromise the safety of our employees, but we would need to consider such a drastic decision

carefully. We need to

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

try to find a way tostay open and make all of our employ- ees safe and secure. Perhaps you could investigate better security for the urban stores. That way, we could solve the problem with capital investment rather than with lost sales. If we can’t do that, we should probably close the stores in those markets. Let’s talk more at the

staff meeting.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA