THE REALIZATION OF EFL LEARNERS’ REQUESTS AND THE CROSS CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS ON THE POLITENESS OF THE REQUESTS

AT SMA TUNAS MEKAR INDONESIA BANDAR LAMPUNG

By Seniarika

POLITENESS OF THE REQUESTS AT SMA TUNAS MEKAR

INDONESIA BANDAR LAMPUNG

A Thesis

By

SENIARIKA

TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION FACULTY LAMPUNG UNIVERSITY

THE REALIZATION OF EFL LEARNERS’ REQUESTS AND THE CROSS CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS ON THE POLITENESS OF THE REQUESTS

AT SMA TUNAS MEKAR INDONESIA BANDAR LAMPUNG

By Seniarika

POLITENESS OF THE REQUESTS AT SMA TUNAS MEKAR

INDONESIA BANDAR LAMPUNG

By SENIARIKA

A Thesis

TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION FACULTY LAMPUNG UNIVERSITY

BANDAR LAMPUNG 2016

The writer’s name is Seniarika. She was born on September 28th, 1981 in Bandung. She is the first daughter of a happy Moslem couple, Muhammad Thamrin, S.H. and Zurniati. Both of them take care of her with her lovely younger sister and brother. She is also a mother of a lovely boy, Dyven Ramskatra, who has become her spirit in accomplishing this thesis.

She graduated from State Elementary School 1 Teladan Kotabumi in 1993. Then she continued her study at State Junior High School 5 Kotabumi and graduated in 1996. After that she entered State Senior High School 10 Bandar Lampung and graduated in 1999. In the same year she was accepted at English Education at Lampung University and graduated in 2004. In 2014, she was registered as a student of the 1stbatch of Master of English Education at Lampung University.

She taught at Bandar Lampung University and English First from 2003 until 2012. She has been teaching for various age levels and subjects. She has also been conducting English trainings in some government offices, institutions, and companies such as Attorney office, Customs office, State Electricity Company, Rabo Bank, Healthcare and Social Security Agency (BPJS), and etc. Since 2015 she has been teaching in Lampung State Polytechnic.

By offering my praise and gratitude to Allah SWT for the abundant blessing to me, I would proudly dedicate this piece of work to:

• My beloved parents, Muhammad Thamrin, S.H and Zurniati. • My beloved son, Dyven Ramskatra

• My beloved brothers and sisters, Irena Friska, A.Md. and Rendi Hortamadeni, S.ST.

• My beloved brother-in-law and sister-in-law, Muhammad Chairul Hasibuan, A.Md. and Febby Adika Lubis, A.Md.

• My beloved nephew and nieces, Rafa Rheynaru Hasibuan, Falisya Alenia Hortamadeni, and Sheeha Varenzha Hasibuan.

• My amazing friend, Rizki Amalia, S.Pd.

“Courage is not having the strength to go on.

It is going on whenyou don’t have the strength”

-Alhamdulillahirabbil’alamin, praise to Allah SWT, the Almighty and Merciful

God, for blessing the writer with faith, health, and opportunity to finish this thesis entitled “The Realization of EFL Learners Requests and the Cross Cultural Perceptions on the Politeness of the Requests at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung”.

Gratitude and honor are addressed to all persons who have helped and supported the writer until completing this thesis, since it is necessary to be known that it will never have come into its existence without any supports, encouragements, and assistances by several outstanding people and institutions. Therefore, the writer would like to acknowledge his respect and sincere gratitude to:

1. Hery Yufrizal, M.A., Ph.D. as the first advisor, for his assistance, ideas, advice, and cooperation in triggering the writer’s spirit for conducting seminars and final examination.

2. Dr. Tuntun Sinaga, M.Hum. as the second advisor, for his advice, criticism, and cooperation in encouraging the writer to think more critically.

3. Dr. Ari Nurweni, M.A. as the 1st examiner, for her advice, ideas, and carefulness in reviewing this thesis.

4. Dr. Flora, M.Pd. as the Chief of Master of English Education Study Program, for her unconditional help, support, and motivation, and all lecturers of Master of English Education Study Program who have contributed during the completion process until accomplishing this thesis.

5. Ujang Suparman, M.A., Ph.D. as the 2ndexaminer and the academic advisor, for his contribution, ideas, and support.

research.

8. Siwi Arbarini Prihatina, S.Pd. as the teacher of the twelfth graders, for her help and full support.

9. All beloved students of twelfth graders at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung, academic year 2015 - 2016, for their participation as the subject of the research.

10. All beloved foreigner teacher friends, for their participation as the raters in the research.

11. Her beloved parents, Muhammad Thamrin, S.H. and Zurniati, who have always prayed and supported the writer.

12. Her brothers and sisters, for their prayers.

13. Her beloved friend, Rizki Amalia, S.Pd., for her unconditional prayers, unlimited inspiration, great motivation, and encouragements.

14. All lovely friends of the 1st batch of Master of English Education, for their solidarity, care, cooperation, togetherness, and irreplaceably unforgettable happy moments.

Finally, the writer fully realizes that this thesis may contain some weaknesses. Therefore, constructive comments, criticisms, and suggestions are always appreciatively welcomed for better composition. After all, the writer expects this thesis will be beneficial to the educational development, the reader, and particularly to those who will conduct further research in the same area of interest.

Bandar Lampung, 16th May 2016 The writer,

Page

2.3.1.1 Blum-Kulka and Olshtain’s Requests Strategy Types ... 18

2.3.1.2 Development of Requests Strategy Types ... 20

2.3.2 Variables Affecting the Realization of Requests ... 21

2.4 Politeness ... 24

2.4.1 Politeness and the Speech Acts of Requests ... 31

2.5 Perception……… 32

2.8 Elicitation techniques in requests studies……… 40

2.8.1 Discourse Completion Test (DCT)……….. 40

2.8.2 Role Play………. 41

III. RESEARCH METHOD 3.1. Research Design ... 43

3.2. Participants of the Research ... 44

3.2.1. The Participants for Speech Acts of Requests Realization Group ... 44

3.2.2. The Participants for Perception Group ... 44

3.3. Data Collecting Techniques ... 45

3.3.2.1 Scaled Perception Questionnaire (SPQ)……… 46

3.3.3. Recording the Role Play, Transcribing the Recorded Role Play, and Coding the Transcript ... 46

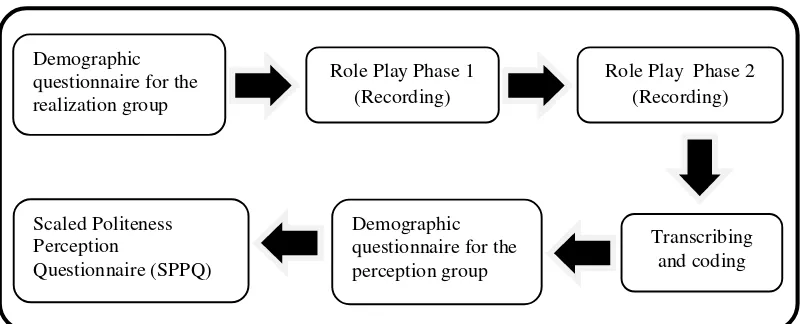

3.4. Steps in Collecting the Data ... 47

3.4.1. Determining the Subjects of the Research ... 47

3.4.2. Administering the Demographic Questionnaire for Request Realization Group ... 48

3.4.3. Conducting the Role Play ... 48

3.4.4. Recording, Transcribing, Coding ... 49

3.4.5. Administering the Demographic Questionnaire for Perception Group ... 49

3.4.6. Administrating the Scaled Perception Questionnaire (SPQ) ... 50

3.5. Data Treatment ... 50

4.1.1 Subjects of Study ... 52

4.1.2 EFL Learners’Requests ... 53

4.1.3 Factors Influencing the Realization of Requests ... 63

4.1.3.1 Gender Effect……… 63

4.1.3.2 Proficiency Level Effect ... 65

4.1.3.3 Interlocutor’ssocial power effect ... 66

4.1.4 Cross Cultural Perception ... 68

4.2 Discussion………. 70

4.2.1 The Realization of EFL Learners’Request Strategy Types…. 70 4.2.2 The Factors Influencing the Realization of Requests…………. 73

4.2.2.1 Gender Effect ... 73

4.2.2.2 Proficiency Level Effect ... 75

4.2.2.3 Interlocutor’ssocial power effect ... 76

4.2.3 The Perception of Cross Cultural Raters……… 77

4.2.4 The Implications………. 82

V. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS 5.1 Conclusion ... 85

5.2 Suggestions ... 87

5.2.1 Suggestion for Future Research ... 88

5.2.2 Suggestion for Second/Foreign Language Classroom Practice . 88 REFERENCES ... 88

APPENDICES Page

1. Appendix A: Demographic Questionnaire for Speech Acts of Requests

Realization Group ………..……. 95

2. Appendix B: Demographic Questionnaire for Perception Group……... 96 3. Appendix C: Role Play Situation……… 96

4. Appendix D: Transcription………. 99

Chapter one provides background of the problem where the researcher elaborates the things that underlie the present study, lays research questions, objectives of the research, use of the research, scope, and definition of terms which aims to help readers to understand the terms used in the present study.

1.1 Background of the problem

English, as a communication tool, is playing an extremely significant role in cross-cultural communication (Lihui and Jianbin, 2010: 41). Whenever people from different countries and from different cultures meet and have communication, they use English to express their ideas or to let the hearer understand what they mean. Thomas (1983:91) uses the term ‘cross-cultural’as a shorthand way of describing not just native-non-native interaction, but any communication between two people who, in any particular domain, do not share a common linguistic or cultural background. This might include workers and management, members of ethnic minorities and the police, or (when the domain of discourse is academic writing) university lecturers and new undergraduate students.

Principle (CP) named quantity, quality, relation, and manner. Quantity means giving the right amount of information, not making the contribution more informative than is required; quality means contributing true information, not saying what the speakers believe to be false; relation means giving the relevant information; and manner means giving perspicuous information, not giving ambiguity and in order contribution.

In other words a cross culture communication is considered to be successful if what the speaker wants to say is clearly heard by the hearer, the

speaker’s intention is understood by the hearer, and there is an effect of the

speaker’s utterance. Austin (1962:108) distinguished a group of things people do in saying something into locutionary act, which is roughly equivalent to uttering a certain sentence with a certain sense and reference; illocutionary act is utterances which have a certain (conventional) force such as informing, ordering, warning, undertaking; and perlocutionary act is what we bring about or achieve by saying something. In short locutionary act is a performance of an utterance, illocutionary act is a hidden intention that a performance of an utterance bring, and perlocutionary act is an action or an effect that comes after locutionary act is performed.

Regarding to the importance of sociolinguistic competence in communication, language learners need to have pragmatics competence. On some occasions conversation involves incomplete sentences, ungrammatically sentences, and indirect statements or indirect request. Hence having pragmatics competence can help people to maintain their conversation. As Fraser (2010:33) said that pragmatic competence is necessary if one is to communicate effectively in a language.

Pragmatic competence is the ability to communicate your intended message with all its nuances in any socio-cultural context and to interpret the message of your interlocutor as it was intended (Fraser, 2010:15). In other words pragmatic competence is crucial to successful cross-cultural and interpersonal communication as it will facilitate speakers to convey their communicative intention and hearers to comprehend the message as it is intended by the speakers.

Speakers who do not use pragmatically appropriate language run the risk of appearing uncooperative at the least, or, more seriously, rude or insulting (Bardovi-Harlig et. al, 1991:4). Pragmatic failure refers to the inability to

understand ‘what is meant by what is said’ (Thomas, 1983:91). In short, pragmatic failure occurs when the hearers do not understand the locutionary act and feel offended.

pragmatic knowledge and cultural information should be incorporated into English teaching.

Leech (1983) in Liu (2007:14-15) proposed to subdivide pragmatics into pragmalinguistics and sociopragmatics components. Pragmalinguistics refers to the resources for conveying communicative acts and relational and interpersonal meanings.On the other hand, sociopragmatics refers to “the sociological interface of pragmatics” which means the social perceptions underlying participants’

interpretations and performances of communicative action.

One of the subsets which lies in pragmatic is speech act.The term “speech act” is used to refer to how the words that a speaker chooses to use affect the behavior of the speaker and the listener in a conversation.Drawing from Austin’s

classification of speech acts, further Searle (1976:10-14) developed and classified illocutionary act into five main categories including representative (such as hypothesizing or flatly stating), directives (such as commanding or requesting), commissives (such a promising or guaranteeing), expressives (such as apologizing, welcoming or sympathizing), and declarations (such as christening, marrying or resigning).

to a greater or lesser extent imposes on the addressee hence there is a need to put politeness strategies into action in order to mitigate the imposition.

The importance of producing polite request ability and having good perception towards utterances heard is unquestionable. If the requests used by the speaker are considered impolite by the hearer, the relationship between the speaker and the hearer can be jeopardized. The speaker may not receive what he or she wanted or needed and the hearer may feel offended. In short cross-cultural

communication requires both speakers’ sufficient mastery of the linguistic

knowledge of the target language and hearers’pragmatic competence.

Having adequate knowledge about perception of people from different cultures on politeness of requests is needed since it can be a guideline for those who have cross culture communication. Meier (1997:24) stated what is perceived as a formal context in one culture may be seen as informal in another. Lee (2011:22) added that utterance which deviates from the frame of a particular culture will of course be seen as impolite or in appropriate in that particular culture. In terms of requests, Aubrecht (2013:14) said that requests that would be pragmatically appropriate in one culture could be inappropriate in another culture. Numerous statements which state that perception on the politeness of the request is different from one culture to another culture has become the main reason why this study is conducted, to know cross-cultural perceptions on the politeness of requests realized by Indonesian EFL learners.

and Chinese EFL learners (Han, 2013) but the number of studies which show the use of requests strategy by Indonesian learners of English is still limited (e.g. Sofwan and Rusmi, 2011). Furthermore many scholars investigated cross cultural perception on the politeness of requests (e.g. Taguchi, 2011; Matsuura, 1998; Lee, 2011) but I have not found any scholars who paid attention on finding out whether the perception of native speaker teachers similar with the perception of non native speaker teachers of English on the politeness of requests in school context.

This study, which focuses on production and perception, took students in EFL setting in Indonesia as the participant in the realization group and took teachers from different culture as the participant in the perception group. The researcher conducted this study because she found some native speakers got confused, felt uncomfortable, and got offended with the requests realized by EFL learners. They did not understand what the EFL learners want them to do or they thought the requests were impolite. In addition this study seemed to be urgent to be conducted due to the fact that more and more Indonesian students go to English speaking countries to continue their studies and due to an assumption that it is important toknow the interlocutors’ perceptionin cross culture communication.

Pragmatics deals with who speaks to whom and politeness as well. Since there is a tendency that Indonesians use different kinds of utterances when talking to those who are in the same age and those who are older, this study involved the

power of interlocutor as one of issues discussed besides other learners’

differently than if she were making a request to ask for something from a teacher or another authority figure.

To sum up since no studies have been found regarding to the EFL

learners’ requests strategy types in school context and to the perceptions of native speaker teachers and non native speaker teachers on the politeness of the requests, this study was accordingly intended to find out the realization of the speech act of requests realized by the EFL learners and the cross cultural perception on politeness of the requests.

1.2 Research Questions

This investigation considers both aspects of pragmatic competence: production/ performance (pragmalinguistic knowledge) and perception (sociopragmatic knowledge). Based on background of the problem mentioned previously the research questions are as follow:

1. What are request strategy types realized by EFL learners at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung in school context?

2. Do gender, proficiency level, and social power of interlocutor (P) influence the requests realized by EFL learners at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung?

1.3 Objectives

The objectives of this research are as follow:

1. To find out what requests strategy types realized by EFL learners at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung.

2. To find out whether gender, proficiency level, and interlocutor’s social

power (P) influence the requests realized by EFL learners at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung.

3. To find out the perceptions of teachers from different culture on the politeness of requests realized by EFL learners at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung.

1.4 Uses

Theoretically first, the results of this study can enrich the previous theory on request strategy types and to confirm findings like there are some factors influence the realization of request and there are differences between perception of native speakers and non native speaker regarding to the politeness of requests used in school context;

especially those realized by EFL learners. Third, they can be used as references to

improve the EFL learners’ sense on the politeness ofrequests.

1.5 Scope

In this study there were two groups involved, the realization group which consisted of third graders students at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung and the perception group which consisted of teachers from different cultures. Those students were chosen because they use English as means of communication and they had chances to interact with people from other countries who were hired as teachers at their school. The teachers were chosen as raters in this study since they are assumed as people who know more about polite requests in school context.

The requests strategy types realized by EFL learners at SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung were elicited through elicitation technique called role play and the perceptions from cross culture raters were obtained through questionnaire called Scaled Politeness Perception Questionnaire (SPPQ). The role plays were recorded and the results were transcribed, coded manually and elaborated qualitatively. The results of the questionnaire were analyzed and explained qualitatively as well.

1.6 Definition of Terms

1. Requests:

Utterances that attempt to get a person to perform an action (Rose, 1999 in Aubrecht, 2013:14)

2. Politeness:

Interactional balance between the need for pragmatic clarity and the need to avoid coerciveness (Blum-kulka, 1987:131)

3. Perception:

Chapter Two mainly establishes a theoretical foundation for this study and presents the previous researches that focus on the realization of request and perception of native and non-native speakers of English. The first part of the chapter unravels the views on pragmatics competence while the second part elaborates speech acts. The third is about speech acts of requests including the requests frameworks and variables affecting the realization of requests. Before exposing previous studies on requests and perception, the researcher explains the politeness in part four and perception in the following part. The last part, eighth part, is about elicitation techniques in requests studies.

2.1 Pragmatics Competence

Pragmatic competence is an important component in communicative competence. The notion of communicative competence has been the subject of discussion for decades (i.e. Canale and Swain, 1980; Canale, 1983; Bachman, 1990; Celce-Murcia et.al, 1995). In Canale and Swain’s communicative competence model (1980:28-31) there are three main competencies: grammatical competence, sociolinguistics competence, and strategic competence. Grammatical competence will be understood to include knowledge of lexical items and rules of morphology, syntax, sentence-grammar semantics, and phonology. Sociolinguistic competence is made up of two sets of rules: sociocultural rules of use and rules of discourse. The primary focus of these rules is on the extent to which certain propositions and communicative functions are appropriate within a given sociocultural context depending on contextual factors such as topic, role of participants, setting, and norms of interaction. Strategic competence is made up of verbal and non verbal communication strategies that may be called into action to compensate for breakdowns in communication due to performance variables or to insufficient competence.

In simple terms, grammatical/linguistics competence refers to the learners’

abilities to produce grammatically or phonologically accurate sentences in the language used; sociolinguistics/sociocultural competence refers to the learners’ ability

to accurately present their sensitivity to linguistic variation within different social contexts; strategic competence refers to the ability to successfully “get one’s message

Canale (1983) in Celce-Murcia et.al (1995:7) then developed the communicative competence model and added another component called discourse competence. So in his model, the communicative competence has four components: grammatical competence- the knowledge of the language code (grammatical rules, vocabulary, pronunciation, spelling, etc); sociolinguistic competence- the mastery of the sociocultural code of language use (appropriate application of vocabulary, register, politeness and style in a given situation); discourse competence- the ability to combine language structures into different types of cohesive texts (e.g., political speech, poetry); strategic competence- the knowledge of verbal and non-verbal communication strategies which enhance the efficiency of communication and, where necessary, enable the learner to overcome difficulties when communication breakdowns occur. In line with the Canale and Swain’s communicative competence model, pragmatics competence is still element part of sociolinguistic competence.

communication takes place. The third element is physiological mechanisms which refer to the neurological and psychological processes that are involved in language use.

Unlike Canale and Swain’s research whereas pragmatic competence is represented as sociolinguistic competence, Bachman’s model of communicative

language ability represent pragmatic competence as a competence in its own right. In other words pragmatics is an element of language competence which refers to the ability to use language to fulfill a wide range of functions and interpret the illocutionary force in discourse according to the contexts in which they are used.

carry illocutionary force (speech acts and speech act sets). Sociocultural competence

refers to the speaker’s knowledge of how to express appropriate messages within the

overall social and cultural context of communication, in accordance with the pragmatic factors related to variation in language use. Finally, these four components are influenced by the last one, strategic competence, which is concerned with the knowledge of communication strategies and how to use them.

2.2 Speech acts

One major component of pragmatics competence is the production and perception of speech acts and their appropriateness within a given context. The idea of speech acts was presented by Austin (1962) and further developed by Searle (1975, 1976). Austin (1962:120) maintained that things we do in saying things perform locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts. The locutionary act which has a meaning, the illocutionary act which has a certain force in saying something, and the perlocutionary act which is the achieving of certain effects by saying something”. For

example, in the utterance, “It’s hot in here,” the locutionary act is the speaker’s

statement about the temperature in a certain location. At the same time, it is possibly an illocutionary act with the force of a request for the door to be opened. It becomes a perlocutionary act when someone is persuaded to go and open the door.

behavior (e.g., to apologize, commending, or condoling); and expositives,acts making plain how our utterances fit into the course of an argument or conversation, how we

are using words, or, in general, are expository (e.g., ‘I reply’, ‘I argue’, or ‘I

illustrate’).

Drawing on Austin’s notion that a theory of language is a theory of action (1962), Searle (1975, 1976) further refined and developed Austin’s illocutionary acts

into speech act theory. Searle (1975:71) said that the theory of speech acts would enable us to provide a simple explanation of how sentences, which have one illocutionary force as part of their meaning, can be used to perform an act with a different illocutionary force. He added that each type of illocutionary act has a set of conditions that are necessary for the successful and felicitous performance of the act. The conditions are identified as felicity conditions.

Searle’s felicity condition types are preparatory conditions, sincerity conditions, propositional content conditions, and essential conditions. For example, for request, preparatory condition is when hearer (H) is able to perform act (A), Sincerity condition is when speaker (S) wants H to do A, propositional content condition is when S predicates a future act A of H, and essential condition counts as an attempt by S to get H to do A.

Claiming that Austin’s taxonomy was based on illocutionary verbs rather than illocutionary acts, which resulted in too much overlap of the categories and too much heterogeneity within the categories, Searle (1976:8-14) further revised Austin’s

do something (e.g., requesting, commanding); 3. Commissives, the speaker’s commit

to some future course of action (e.g., promising, threatening); 4. Expressives, express a psychological state specified in the sincerity condition about a state of affairs specified in the propositional content. (e.g., thanking, apologizing, welcoming); 5. Declarations, the successful performance of one of its member brings about the correspondence between the propositional content and reality, successful performance guarantees that the propositional content corresponds to the world (e.g., christening, declaring war).

2.3 Request

According to Searle’s classification (1976:11) a request is categorized as a “directive” speech act whereby a speaker (requester) conveys to a hearer (requestee) that he/she wants the requestee to perform an act, which is for the benefit of the speaker.

2.3.1 Requests Frameworks

Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1984:201) said that on theoretical grounds, there seem to be three major levels of directness that can be expected to be manifested universally by requesting strategies;

a. the most direct, explicit level, realized by requests syntactically marked as such, such as imperatives, or by other verbal means that name the act as a request, such as performatives and hedged performatives;

c. nonconventional indirect level, i.e. the open-ended group of indirect strategies (hints) that realize the request by either partial reference to object or element needed for the implementation of the act ('Why is the window open'), or by reliance on contextual clues ('It's cold in here').

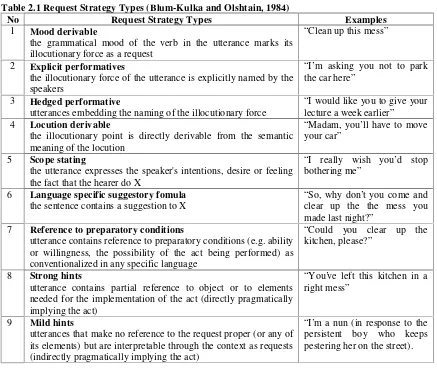

2.3.1.1 Blum Kulka and Olshtain ’s requests strategy types

On the basis of empirical work on requests in different languages, Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1984:201) launched the term CCSARP (Cross Cultural Study of Speech Act Realization Patterns) and subdivided the three levels of directness into nine distinct sub-levels called 'strategy types' that together form a scale of indirectness. The categories on this scale are expected to be manifested in all languages studied; the distribution of strategies on the scale is meant to yield the relative degree of directness preferred in making requests in any given language, as compared to another, in the same situation.

The nine strategy types proposed by Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1984:202) are: (1) Mood derivable, the grammatical mood of the verb in the utterance marks its

illocutionary force as a request, e.g “Clean up this mess” ; (2) Explicit performatives, the illocutionary force of the utterance is explicitly named by the speakers, e.g “I’m asking you not to park the car here” ; (3) Hedged performative, utterances embedding the naming of the illocutionary force, e.g “I would like you to give your lecture a week

earlier” ; (4) Locution derivable, the illocutionary point is directly derivable from the semantic meaning of the locution, e.g “Madam, you’ll have to move your car” ; (5)

specific suggestory formula, the sentence contains a suggestion to X, e.g “So, why don’t you come and clear up the the mess you made last night?” ; (7) Reference to preparatory conditions, utterance contains reference to preparatory conditions (e.g. ability or willingness, the possibility of the act being performed) as conventionalized in any specific language, e.g “Could you clear up the kitchen, please?” ; (8) Strong hints, utterance contains partial reference to object or to elements needed for the implementation of the act (directly pragmatically implying the act), e.g “You’ve left

this kitchen in a right mess” ; (9) Mild hints, utterances that make no reference to the request proper (or any of its elements) but are interpretable through the context as requests (indirectly pragmatically implying the act), e.g “I’m a nun (in response to the

persistent boy who keep pestering her on the street).

Table 2.1 Request Strategy Types (Blum-Kulka and Olshtain, 1984)

No Request Strategy Types Examples

the illocutionary force of the utterance is explicitly named by the speakers

“I’m asking you not to park the car here”

3 Hedged performative

utterances embedding the naming of the illocutionary force

“I would like you to give your lecture a week earlier”

4 Locution derivable

the illocutionary point is directly derivable from the semantic meaning of the locution

“Madam, you’ll have to move your car”

5 Scope stating

the utterance expresses the speaker's intentions, desire or feeling the fact that the hearer do X

“I really wish you’d stop

bothering me”

6 Language specific suggestory fomula the sentence contains a suggestion to X

“So, why don’t you come and

clear up the the mess you

made last night?”

7 Reference to preparatory conditions

utterance contains reference to preparatory conditions (e.g. ability or willingness, the possibility of the act being performed) as conventionalized in any specific language

“Could you clear up the kitchen, please?”

8 Strong hints

utterance contains partial reference to object or to elements needed for the implementation of the act (directly pragmatically implying the act)

“You’ve left this kitchen in a right mess”

9 Mild hints

utterances that make no reference to the request proper (or any of its elements) but are interpretable through the context as requests (indirectly pragmatically implying the act)

“I’m a nun (in response to the

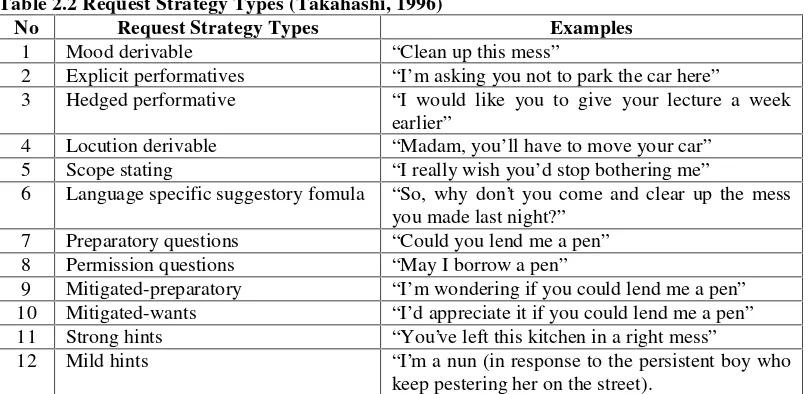

2.3.1.2 Development of requests strategy types

Several researchers (e.g., Takahashi, 1996; Lin, 2009) have attempted to develop coding schemes for analyzing requests. Takahashi (1996:220) developed the framework of request by adding several types on preparatory expression: preparatory questions (i.e., questions concerning the hearer's will, ability, or possibility to perform

a desired action), e.g. “could you lend me a pen” ; permission questions, e.g. “may I

borrow a pen” ; mitigated-preparatory (i.e., query preparatory expressions embedded

within another clause), e.g. “I’m wondering if you could lend me a pen” ; and

mitigated-wants (i.e., statements of want in hypothetical situations), e.g. “I’d

appreciate it if you could lend me a pen” .

Table 2.2 Request Strategy Types (Takahashi, 1996)

No Request Strategy Types Examples

1 Mood derivable “Clean up this mess”

2 Explicit performatives “I’m asking you not to park the car here”

3 Hedged performative “I would like you to give your lecture a week earlier”

4 Locution derivable “Madam, you’ll have to move your car”

5 Scope stating “I really wish you’d stop bothering me”

6 Language specific suggestory fomula “So, why don’t you come and clear up the mess you made last night?”

7 Preparatory questions “Could you lend me a pen”

8 Permission questions “May I borrow a pen”

9 Mitigated-preparatory “I’m wondering if you could lend me a pen”

10 Mitigated-wants “I’d appreciate it if you could lend me a pen”

11 Strong hints “You’ve left this kitchen in a right mess”

12 Mild hints “I’m a nun (in response to the persistent boy who

keep pestering her on the street).

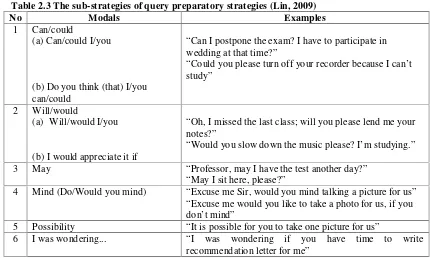

have the test another day); IV. Mind (Do/Would you mind) (example: Excuse me Sir, would you mind talking a picture for us); V. Possibility (example: It is possible for you to take one picture for us); VI. I was wondering...

Table 2.3 The sub-strategies of query preparatory strategies (Lin, 2009)

No Modals Examples

1 Can/could

(a) Can/could I/you

(b) Do you think (that) I/you can/could

“Can I postpone the exam? I have to participate in

wedding at that time?”

“Could you please turnoff your recorder because I can’t

study”

2 Will/would

(a) Will/would I/you

(b) I would appreciate it if

“Oh, I missed the last class; will you please lend me your notes?”

“Would you slow down the music please? I’m studying.”

3 May “Professor, may I have the test another day?” “May I sit here, please?”

4 Mind (Do/Would you mind) “Excuse me Sir, would you mind talking a picture for us” “Excuse me would you like to take a photo for us, if you

don’t mind”

5 Possibility “It is possible for you to take one picture for us”

6 I was wondering... “I was wondering if you have time to write recommendation letter for me”

The studies were conducted in different places and involved people from different cultures and with different characteristics. They showed that requests strategy used all over the world is influenced by the culture of people where the language is used and by the people’s characteristics. The variables affecting the realization of

requests are discussed in the following section.

2.3.2 Variables affecting the realization of requests

Lorenzo-Dus and Bou-Franch (2003:196-197) got, at least, two findings in their study involved Spanish and British undergraduates: both Spanish men and women used mainly direct strategies in their requests, and British women were not more direct than men.

The requests strategies use is also influenced by cultural background of society. Zhu and Bao (2010:850) compared between Chinese and Western politeness in cross cultural communication. They found that in western society, personal interest, individual power and privacy are all believed sacred and inviolable. So, even in communication between employer and employee, parents and children, teachers and students, communicators must follow the tact maxim to reduce the threat to other

person’s negative face or reduce the compulsive tone. However, from the point of

view of Chinese tradition, people’s behavior is restricted by social expectation. Some people have the right to give the others commands, requests, suggestions, advices, warnings, threatens, etc.; while other people have to accept or fulfill the behavior. For example, directive language can only be used by the elderly to the younger ones, employers to their employees, teachers to their students and parents to their children, or else it is impolite.

Saudi students in intimate situations where directness is interpreted as an expression of affiliation, closeness and group-connectedness rather than impoliteness.

Power and distance were also found as variables affecting the use of requests strategies (Han, 2013:1104). By contrasting the strategies of head acts both in English and Chinese, we can find that the similarity between native Chinese speakers and native English speakers is that both value conventionally indirect strategies and their difference lies in that native Chinese speakers prefer to use direct strategies i.e. imperatives, in some cases, while native English speakers seldom choose to use imperatives when requesting someone to do something. Furthermore, in adopting conventionally indirect strategies, native Chinese speakers are inclined to use tag questions such as “…Is it ok?” or “Do you agree?)” while their English counterparts tend to use general questions in the forms of “Can/Could you…?”, “Will/Would you…?” and “Would you mind…?”. In Chinese traditional culture, individual’s

position and power in the society is very much emphasized since China had been a hierarchical society for thousand years. On the other hand in almost all the English-speaking countries, individualism is highly valued and cherished. The value of equality is also emphasized in everything from government affairs to daily social deals. Since everyone in such a society treat others as equals, the power relationship, which is stressed in Chinese society, will not play a big role. As a result, direct strategies or imperatives, which seem more or less like orders, will certainly not be preferred when they make requests.

grammatical knowledge performed better both in grammatical knowledge and pragmatic competence.

Rank of imposition can also be a variable affecting the realization of request. This finding was obtained by Sofyan and Rusmi (2011:78) after they investigated the requests strategy types realized by English teachers of Junior High school in Indonesia. When the imposition of the situation is low, the teachers used three kinds of strategies: direct, conventionally indirect, and non-conventionally indirect strategies, with the mood derivable strategy is the most direct strategies, followed by Query preparatory, and then mild hints. On the other hand when the imposition of the situation is high, all the teachers used conventional indirect strategies to address their requests. They used query preparatory (75%), followed by direct strategies in the form of hedged performatives (20%) and mood derivable (5%). In other words, they found that the higher the rank of imposition, the more indirect the request strategies will be.

However, this study does not investigate all factors discussed above. This study discusses about requests realization in school context only so the researcher limits the area of discussion to three factors only- gender, proficiency level, and social power.

2.4 Politeness

Stephen C. Levinson, and Richard J. Watts. Numerous scholars deal with politeness but their theories are considered as the most influential ones.

a. Robin Lakoff’s theory of politeness

Lakoff (1973) in Subertova (2013:13-14) defines politeness as forms of behavior that have been developed in societies in order to reduce friction in personal interaction. According to her, pragmatic competence consists of a set of sub-maxims, namely: 1- Be clear and 2- Be polite. There are many situations in which the requirement of the first maxim (be clear) is more important than the other one (be polite), and vice versa. Lakoff clarifies this relationship by asserting that politeness usually supersedes. It is considered more important in a conversation to avoid offense than to achieve clarity. This makes sense since in most informal conversations actual communication of important ideas is secondary to merely reaffirming and strengthening a relationship.

Lakoff characterizes politeness from the perspective of the speaker. She identifies three sub-types: 1. formal (or impersonal) politeness (don't impose/remain aloof). 2. informal politeness – hesitancy (Give options) 3. intimate politeness –

strategy can be troubling. In brief, Lakoff views politeness both as a way to avoid giving offense and as a lubricator in communication that should maintain harmonious relations between the speaker and the hearer.

b. Geoffrey Leech’s theory of politeness

Leech in (1983) in Subertova (2013:14-17) formulates the Politeness Principle by giving us a set of maxims. His concept is based on the terms self and other. In a conversation theselfwould be identified as the speaker(or anybody or anything close to the speaker), and the otherwould normally be identified as the hearer(or anybody or anything associated with the hearer). The goal of the PP is to maintain the social equilibrium and the friendly relations which enable us to assume that our interlocutors are being cooperative in their communication with us. The PP employs six maxims (that tend to go in pairs) to perform its functions.

The six maxims with their corresponding sub-maxims go as follows: 1. TACT MAXIM: a) Minimize cost to other; b) Maximize benefit to other. 2. GENEROSITY MAXIM: a) Minimize benefit to self; b) Maximize cost to self. 3. APPROBATION MAXIM: a) Minimize dispraise of other;b) Maximize praise ofother. 4. MODESTY MAXIM: a) Minimize praise of self;b) Maximize dispraise of self. 5. AGREEMENT MAXIM: a) Minimize disagreement between self and other; b) Maximize agreement betweenselfandother. 6. SYMPATHY MAXIM: a) Minimize antipathy between self

andother; b) Maximize sympathy betweenselfandother.

(e.g. Sit down, please.) brings more benefit to the addressee than a request does (e.g.

Wash the dishes, please.) 2. The OPTIONALITY SCALE on which illocutions are ordered according to the amount of choice which s allows to h. A request in the imperative (e.g. Help me!) gives addressee a smaller amount of choice than the same request formulated as question (e.g. Could you help me, please?) 3. The

INDIRECTNESS SCALE on which, from s’s point of view, illocutions are measured

with respect to the length of the path (in terms of means-end analysis) connecting the illocutionary act to illocutionary goal. For example, an interpretation of Close the win dow, please is easier than a request formulated I am cold. 4. The AUTHORITY SCALE on which is the ‘power’ of authority of one participant over another is

determined. This, for example, means that a superior has more of a right to expect an inferior to fulfill his request than vice versa. 5. The SOCIAL DISTANCE SCALE on which we ascertain the overall degree of respectfulness, which depends on relatively permanent factors of status, age, degree of intimacy, etc. but to some extent on the temporary role of one person relative to another. This means that a speaker can expect help from his friend rather than from a passer-by.

c. Brown and Levinson’s theory of politeness

One of the most influential, detailed and well-known models of linguistic politeness is that of Brown and Levinson (1987) in Subertova (2013:18-21). They were not only inspired by Grice’s CP and Austin’s and Searle’s theory of speech acts,

but also by conception of face. Face is the public self-image of a person. Thus, every

participant of a conversation has a face, and everyone’s task in a conversation is to

threatened in specific situations and such threats are called face-threatening acts

(FTAs).

In their theory, face is two dimensional – they work with the concepts of positive and negative face. However, the terms positive and negative are not subject to evaluation; we cannot consider the positive face to be better than the negative one. The terms are meant in a directional way (vectorial), i.e. the positive face metaphorically aims outwards and the negative inwards, into the inner world of the speaker. Brown and Levinson define the positive face as the positive consistent self-image of ‘personality’ (crucially including the desire that this self-image be appreciated and approved of) claimed by interactants. On the other hand, thenegative face is our wish not to be imposed on by others and to be allowed to go about our business unimpeded with our rights to free and self-determined action intact. To sum up, the negative face

is the desire of every ‘competent adult member’ for his/her actions to be unimpeded by

others while the positive face is the wish of every member for his/her wants to be desirable to at least some others.

Brown and Levinson give us examples of positive politeness strategies: expressing an interest in and noticing the hearer, using ‘in-group’ language, noticing and attending to the hearer’s desires, making small talk, exaggerating

As already mentioned, the face is threatened in certain situations, and those threats are called face-threatening acts (FTA). FTA’s categories are: acts threatening

the positive face of the speaker (e.g. apologies, confessions), acts threatening the negative face of the speaker (e.g. expressing gratitude, promises, offers, obligations), acts threatening the positive face of the addressee (e.g. criticism, disrespect, refusal), acts threatening the negative face of the addressee (e.g. orders, requests, threats).

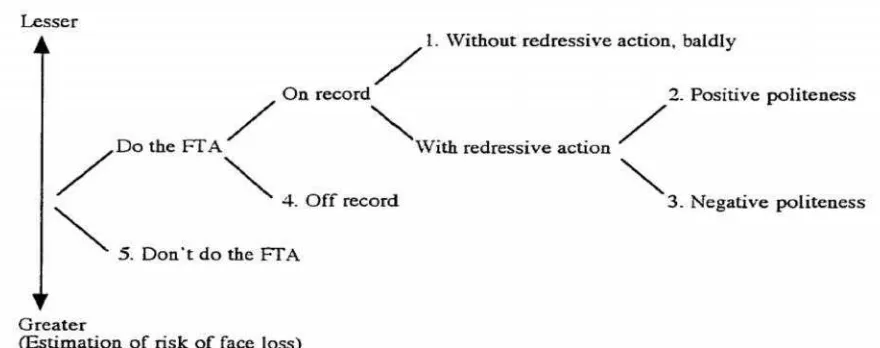

Brown and Levinson then focus especially on acts threatening the addressee, providing us with a taxonomy of strategies that the speaker can follow when intending to do the FTA: 1. Do the FTA on record without redressive actions (the least polite) –

e.g. Watch out!; Don’t burn yourself!; Give me 10 bucks. 2. Do the FTA on record with redressive action addressing positive face–e.g.Your concert had a relatively low attendance. 3. Do the FTA on record with redressive action addressing negative face–

e.g. Would you mind...?; Forgive me for interrupting. 4. Do the FTA off record– e.g. irony, rhetorical questions, discourse markers; conversational implicatures in general

(Grice 1975), 5. Don’t do the FTA (the most polite strategy). This can also be

illustrated in the following figure:

d. Richard J Watts’s theory of politeness

Watts (2003:4-10) classified (im)politeness into two parts: first-order (im)politeness, folk interpretation; and second-order (im)politeness, a concept in a sociolinguistic theory. He says that first-order politeness or politeness 1 reveals a great

deal of vacillation on how behavior is evaluated as ‘polite’ at the positive end of the scale when compared with the negative end. Further whether or not a participant’s

behavior is evaluated as polite or impolite is not merely a matter of the linguistic expressions that s/he uses, but rather depends on the interpretation of that behavior in the overall social interaction. On the other side, second-order politeness or politeness 2 means something rather different from our everyday understanding of it and focuses almost uniquely on polite language in the study of verbal interaction.

In simple terms, the linguistic definition of politeness is usually different from the general perception of the term politeness. First order politeness is what the majority of people of a certain cultural and language community consider polite (e.g. to behave well by using polite phrases, like please, thank you, your welcome, etc.) while second-order politeness is the theoretical term used in sociolinguistics. First-order politeness is always connected with evaluation, while second-First-order politeness is a term for a set of strategies in communication, not an evaluative term.

particular interaction, which happens in a certain environment, in a certain situation, with a specific speaker and addressee. Moreover, we must consider the perspective of the speaker and also the addressee. Lexical terms such as please orthank you are not polite inherently or always. They can be interpreted as polite only in certain communication.

Watts is one of the first linguists to have noticed aspects that earlier authors had not; for example, the above-mentioned fact that abstract theories of politeness are not always reflected in the use of real language, and that politeness is something that every interlocutor can perceive differently.

2.4.1 Politeness and the speech acts of requests

Politeness is one of the most important impressions of human and human being cannot live with each other and communicate together if conventions of politeness are not observed in the society that they live in. it is a universal, interdisciplinary phenomenon. Every culture, every language, has its ways of displaying respect and deference, saving face, avoiding, or minimizing, imposition and exercising good manners verbally and non-verbally. Numerous studies have shown that the conventions of politeness are different from one culture to another (e.g. Lee, 2011; Matsuura, 1998; Taguchi, 2011).

A request is people’s communication of their intentions with others by words

and sentences. It is a person’s intention to have his anticipation reached by another

person. Request acts can affect the pressure on the hearer. It may threaten the addressee’s negative face or positive face. A negative face-threatening act can

positive face-threatening act is against the addressee’s desire to be liked and

appreciated.

In performing a request, the speaker should always adhere to the principles of politeness and try to avoid direct request. Leech and Brown and Levinson explain that direct form appear to be impolite and face threatening act, but indirect form tend to be more polite and is a suitable strategy for avoiding threatening face. Since there is a the connection between politeness and speech acts of requests, the proper realization of

requests needs both the speaker’s awareness of politeness and judgment of the request

strategies.

2.5 Perception

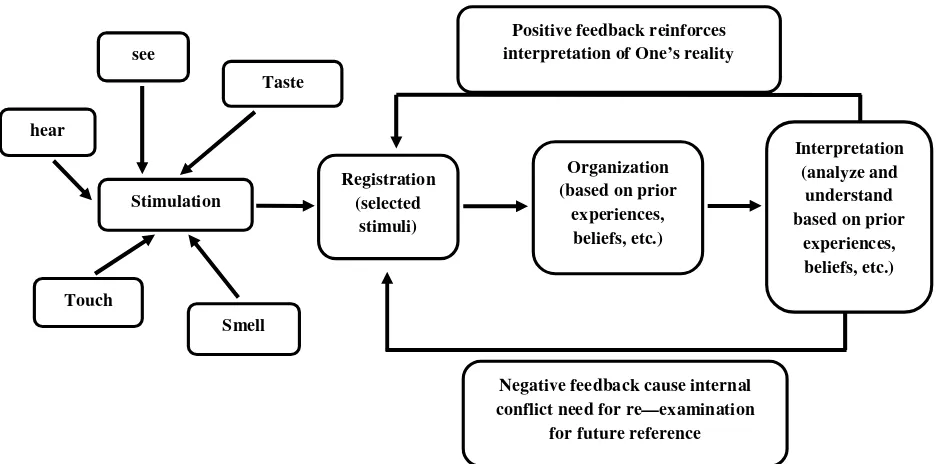

Lindsay and Norman (1977) in Borkowski (2011:52) said that perception is a process by which organisms interpret and organize sensation to produce a meaningful experience of the world. Borkowski (2011:52) added that the perception process follows four stages: stimulation, registration, organization, and interpretation.

The figure shows that sense organs and past experience affect someone’s

perception. When someone is confronted with a situation or stimuli, he or she interprets the stimuli into something meaningful to him or her based on what he or she got through sense organs and based on prior experiences. In addition the target or interlocutor and the context in which a person see objects or events are also important factors to shape a perception.

2.5.1 Cross Cultural Perception

Perception across culture plays an important role in categorizing politeness. Lee (2011:22) said that people shape their frames about politeness based on the environment and culture in which they live. In other words what is considered in one culture to be polite may seem impolite in another. Similar opinion was expressed by Meier (1997:24) who stated that what is perceived as a formal context in one culture may be seen as informal in another. Perception differences from one culture to another make the widely known politeness marker like “please” could be shown to be not polite if it increases the directness of requests by making their force more obvious.

2.6 Studies on the Realization of Requests

Many researchers conducted studies on the requests realized by English learners and different results indicate that there are varieties of requests strategy used in communication (e.g. Kim, 1995; Otcu and Zeyrek, 2008; Sofyan and Rusmi, 2011; Jalilifar et. Al, 2011, Hendriks, 2008)

a. Request realized by Korean learners of English

Kim (1995:6) involved 15 American English native speakers, 15 Korean ESL learners, and 25 native Korean speakers. The finding was that in requesting to get off work early, non native speakers and native Korean speakers were much more indirect-which might seem rude to a native English speaker in this type of situation. In contrast, non native speakers were overly direct in asking a child to go to sleep.

b. Requests realized by Turkish learners of English

c. Request realized by Indonesian learners of English

Sofyan and Rusmi (2011:69) involved 20 teachers, ten male and ten female from Junior High Schools in their study. They have been teaching English for more than five years and were holders of the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English language education. The requests strategy type analyzed are based on CCSARP categories. There were 180 request strategies in the utterances found in this study. The strategies were then classified into three categories: higher-ranking to lower ranking, equal to equal, and lower-ranking to higher-ranking.

The results showed that in category one the teachers used direct strategies 5 times (2.8%), conventional indirect strategies 54 times (30%) and non-conventional indirect strategies only once (0.6%). The only non-conventional indirect strategy was in the form of mild hints. In category two the teachers used direct strategies 14 times (7.8%), conventional indirect strategies 46 times (25.6%) and 0% non-conventional indirect strategies. In category three the teachers used eleven times (6.1%) of direct strategies, 49 times (27.2%) of conventional indirect strategies and 0% of non-conventional indirect strategies.

d. Request realized by Iranian learners of English

Jalilifar et.al (2011:790) investigated the request strategies used by Iranian learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and Australian native speakers of English. A Discourse Completion Test (DCT) was used to generate data related to the request strategies used by each group. The data showed that the EFL learners with higher proficiency displayed overuse of indirect type of requesting, whereas the native group was characterized by the more balanced use of this strategy. The lower proficiency EFL learners, on the other hand, overused the most direct strategy type.

e. Request realized by Dutch learners of English

Hendriks (2008:34) involved three groups of respondents: native English, non-native English, and non-native Dutch. The data showed that hints, the most indirect request strategies, were used in less than one per cent of all requests. Only about ten per cent of the requests were formulated with direct request strategies, the majority of which were want statements, in which speakers state their wishes or desires. Few of the native Dutch or native English requests were formulated with want statements, but the learners used them slightly more often. This suggests that although the learners know that want statements can be used to formulate English requests, they use them slightly too often.

2.7 Studies on the Perception of Requests

different with another person (e.g. Lee, 2011; Matsuura, 1998; Taguchi, 2011;

Mohammadi and Tamimi Sa’d,2013)

a. Perception of NS and NNS towards requests realized by Chinese learners of English

After having cross culture investigation, Lee (2011:28-33) found that there are similarities and differences when it comes to the topic of what “politeness” is in Chinese and Western cultures. Both groups of Chinese learners and native speakers agreed that some form of request like “go get the book”, “why don’t you get the book”, and “I want you to get the book” considered to be “not acceptable and not

polite”.

On the other hand, different perceptions were found in forms of requests like “you will go get the book, right?”, “I would like you to go get the book”, “would you

go get the book”, and “would it trouble you to go get the book?”. Native speakers

thought the request “you will go get the book, right?” was “not acceptable and not polite” while Chinese learners thought it was “acceptable but not polite”. Native speakers thought the request “I would like you to go get the book” and “would you go

get the book” were “acceptable and not polite” while Chinese learners thought they were “acceptable and polite”. Native speakers thought the request “would it trouble you to go get the book?” was “acceptable and polite” while Chinese learners thought it

b. Perception of Japanese and American towards English requests

Matsuura (1998:38-46) conducted a study on how the Japanese perception of politeness in making English requests could differ from that of Americans. The study involved 77 Japanese and 48 American university students. They were given 11 English sentences which were used in the action of borrowing a pen, with a seven-point rating scale. The sentences were I was wondering if I could…, May I borrow a pen?, Could you lend me a pen?, Could I borrow a pen?, Do you have a pen I can use?, Can you lend me a pen?, Can I borrow a pen?, Got a pen I can use?, Let me borrow a pen., Lend me a pen., Give me a pen.

The results showed that both groups felt that "I was wondering if I could borrow a pen" was the most polite request, followed by such interrogatives as "Could you lend me a pen?" and "Could I borrow a pen?". Japanese students and American students have different perception on "May I ... ?" form. Japanese students rated this interrogative request to be almost neutral in politeness while Americans evaluated it as a very polite request.

c. Perception of mixed cultural background towards requests realized by Japanese learners of English

Using a five-point rating scale, four native English speakers of mixed cultural background (one African American, one Asian American, and two Australians) rated the appropriateness of requests produced by 48 Japanese EFL students (Taguchi, 2011:459-463). The five-point rating scale is ranging from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent): 5 is for Excellent: almost perfectly appropriate and effective in the level of directness, politeness, and formality. ; 4 is for good: not perfect but adequately appropriate in the level of directness, politeness, and formality. Expressions are a little off from target-like, but pretty good. ; 3 is for fair: somewhat appropriate in the level of directness, politeness, and formality. Expressions are more direct or indirect than the situation requires. ; 2 is for poor: clearly inappropriate. Expressions sound almost rude or too demanding. ; and 1 is for very poor: not sure if the target speech act is performed.

For a request like “Ah, sorry, I beg you pardon? Please one more time, what you said” which was addressed to a close friend, the two Australian have the same perception. They said that it was in category 3 which is fair. The Japanese American participant had different perception. She rated 4 for the request inasmuch as it was a little overly polite. The African American gave even a perfect score on this request, 5.

2.8 Elicitation technique in requests studies

Kasper and Dahl (1991:216) divided data-collection methods in pragmatics research into the categories of (a) production-based methods (observation of authentic discourse and use of discourse completion tasks [DCTs] and role plays) and (b) perception/comprehension-based methods (the use of multiple-choice and scaled response instruments [questionnaires] and interviews).

Numerous requests studies use Discourse Completion Test (DCT) (e.g. Jalilifar

et.al, 2011; Woodfield, 2008; Mohammadi and Tamimi Sa’d, 2014; Sattar et.al, 2009;

Hendriks, 2008; Kim, 1995; Tawalbeh and Al-Oqaily, 2012) or Role Play (e.g. Otcu and Zeyrek, 2008; Tanaka, 1988; Han, 2013; Taguchi, 2006) as their elicitation technique to obtain data of requests strategy.

2.8.1 Discourse Completion Task (DCT)

DCT has many administrative advantages, for example allowing the researcher to control for certain variables (i.e. age of respondents, features of the situation, etc) and to quickly gather large amount of data without any need for transcription, thus making it easy to statistically compare responses from native to non native speakers (Golato, 2003:92). In other words, DCT can provide large amounts of data in a short period of time with a minimum of effort. Although DCT cannot provide authentic speech, it can provide insights into what subjects think they would do in a certain situation.

However, Beebe and Cummings (1985) in Kasper and Dahl (1991:243) found that written role plays bias the response toward less negotiation, less hedging, less repetition, less elaboration, less variety and ultimately less talk. The data do not correspond to natural spoken language, or in other words the language collected with DCTs does not reveal the actual pragmatics features of spoken interaction (Han, 2013:1099)

2.8.2 Role Play

Role plays have advantage over authentic conversation that it is replicable and, just as Discourse Completion, allow for comparative study (Kasper and Dahl, 1991:229). Other advantages of this method are that the subjects have the opportunity to say what they would like to say at their own chosen length, and their spoken

language is thought to be a good indication of their “natural” way of speaking.

This chapter lays out the design used in the study, explains who the participants are, describes the data collection technique used in the study, outlines the procedures employed, and elaborates how the researcher treats and analyses the data obtained.

3.1 Research Design

This study is a qualitative study. This study was intended to find out what requests strategy types realized by the EFL learners at SMA TMI Bandar Lampung in school context, what factors influencing the realization of requests and whether perception of native speakers and non native speakers towards the politeness of requests similar. To obtain a thorough data for answering the research questions, the researcher conducted role plays and administered questionnaire.

Role plays were conducted in order to elicit students’ requests strategy

requirements as those who were capable to rate the politeness of requests realized by the students. Another questioner given to the raters was so called Scaled Politeness Perception Questionnaire (SPPQ). It was aimed to find out and then compare the perception of NS and NNS towards the speech act of requests realized by EFL learners.

3.2 Participants of the research

There were two groups involved in this study, speech act of request realization group and perception group.

3.2.1 The participants for speech act of requests realization group

The participants for realization group were senior high school students of SMA Tunas Mekar Indonesia Bandar Lampung. The students were purposively chosen since they have been learning English for years and they use English as a means of communication. In this study there were 20 students who were paired to do role plays. All pairs were given four different situations in school context. In the two situations the power of the relationship was equal (=P) while in the other two situations the power of the listener was higher (+P).

3.2.2 The participants for perception group

assumes that teachers are group of people who are well-educated and know more about polite requests in school context.

In this study the three Native Speaker teachers and three Non Native Speaker teachers were asked to fill out Scaled Politeness Perception Questionnaire (SPPQ). In that questionnaire those participants expressed their perceptions regarding to the speech act of requests realized by EFL learners.

3.3. Data Collecting Techniques

This study considers the two primary aspects of pragmatics competence, production (pragmalinguistics knowledge) and perception (sociopragmatics knowledge). Multimethod data collecting technique was applied to obtain thorough data needed, role play for eliciting the pragmalinguistics knowledge and Scaled Politeness Perception Questionnaire (SPPQ) to find out the sociopragmatics knowledge.

3.3.1. Requests Realization Group 3.3.1.1 Demographic questionnaire

Demographic questionnaire was administered in order to find out the

participants’ background and characteristics. From the questionnaire the researcher got the data about name, age, gender, and proficiency level.

3.3.1.2 Role Play

simulating more authentic situation. This method also allows interaction with an interlocutor and offers the opportunity to observe a great variety of pragmatics feature which can be found in natural conversation and that are often lost when other methods of data collection such as discourse completion tasks (DCT) are used.

The Role Play conducted in this study involved twenty students which were paired. They did role play based on the four situations in school context. The situations are asking a classmate to move his or her bag, asking a teacher to repeat his or her lesson, asking a classmate to lend his or her biology notes, and asking a teacher to extend a due date of paper submission.

3.3.2. Perception Group

3.3.2.1 Demographic questionnaire

Demographic questionnaire was administered in order to find out the

participants’ background. From the questionnaire the researcher got the data about

name, age, gender, job, nationality, and educational background.

3.3.2.1 Scaled Politeness Perception Questionnaire (SPPQ)

This questionnaire consisted of ten requests which were chosen randomly. It was given to be rated and commented by the six raters who come from different culture. They were asked to perceive the politeness of the requests strategy types realized by the EFL learners at SMA TMI Bandar Lampung.