A short description of Gangalidda (Ganggalida/Yukulta)*

This description was prepared for the Gangalidda Dictionary compiled by Cassy Nancarrow, published by the Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation and launched in

Bourketown on June 18, 2014. The published version was an edited version of this manuscript.

Although the text is aimed at a non‐technical audience, it may be of interest to the linguistic community insofar as it contains analysis, especially of the morphology and the clitic

complex, which attempts to go beyond the treatment in Keen (1983).

All language forms are cited in the practical orthography of the Dictionary, indicated below. All examples are from my own transcriptions and analysis of Sandra Keen’s field recordings.

Sound Ganggalida spelling Sound Ganggalida spelling

low vowel aa, a palatal nasal ny

bilabial stop b retroflex r r

alveolar stop d retroflex stop rd

velar stop g (or k after n) retroflex l rl

high front vowel ii, i retroflex nasal rn

palatal stop j trilled r rr

alveolar l l dental stop th

bilabial nasal m high back vowel uu, u

alveolar nasal n labiovelar glide w

velar nasal ng palatal glide y

dental nasal nh

Erich Round,

University of Queensland, August 2014 e.round@uq.edu.au

* The language community’s preferred spelling, agreed to after this manuscript was compiled, is

1. Ganggalida grammar — the key points

This section is short, but useful. It describes some key points of Ganggalida grammar. Much more detail can be found in the later sections.

1.1 Kinds of words and what they do

Every language has several different kinds of words, that perform different tasks. An

interesting fact is that languages don’t all work the same way. Here is a quick description of the main kinds of words that Ganggalida has, and what they do.

Nouns

Nouns are words that can name people, places and things. Examples of nouns in Ganggalida are ngurliwa ‘little girl’, malara ‘sea’ and wanggurdu ‘woman’s younger brother’. There are also nouns that can name events, such as wirrganda ‘dance’, or abstract ideas, like bayi ‘trouble’.

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that can describe what people, places, events and things are like. Examples of adjectives in Ganggalida are gunyara ‘small’, burdaburda ‘wet’ and

yanangarrbanda ‘new’.

Determiners

Determiners are words that say which person or thing someone is talking about. Examples of determiners in Ganggalida are ngijinda ‘my’ and danda ‘this’.

Nouns, adjectives and determiners can be put together into a group of words called a Noun Phrase, such as danda gunyara ngurliwa ‘this little girl’.

Pronouns

Pronouns can name something that someone has already been talking about, like gilda ‘them’, or they can name something that is clear from context, like nyingga ‘you’ or danda ‘this’.

Verbs

Verbs name the action in the sentence, like jawija ‘run’ or waaja ‘sing’.

Clitics

Clitics in Ganggalida are a special kind of word. They are introduced in section 1.2.

1.2 The parts of a sentence

This section briefly mentions three features of Ganggalida sentences which can be

unfamiliar if you are mainly used to English. They are the Clitic, the endings on words, and the order of the words in the sentence.

The main Clitic

Almost all Ganggalida sentences have a Clitic, which attaches itself to the end of another word. For example in the sentence in (1) the Clitic ‐ngga attaches itself to the word

danggara, meaning ‘man’.

(1) Danggara‐ngga thaldija gamarri.

‘The man is standing on the stone.’

In sentence (1) the Clitic expresses information about who is doing the action: ‐ngga tells you that it is just one person or thing doing the action, and it’s not me and it’s not you. The person or thing which does an action is called the Subject, and the Clitic ‐ngga tells you about the Subject.

In sentence (2) the Clitic ‐nki attaches itself to the word gurrija, meaning ‘see’.

(2) Gurrija‐nki barrunthaya?

‘Did you see me yesterday?’

Endings on words

In English, endings on words can tell us certain kinds of information, for example, the ending ‐s on dogs tells us that we are talking about more than one dog. In Ganggalida, endings are used to express many kinds of information. For example, the word for ‘stone’ is

gamarra, but with a different ending, the word gamarri means ‘on the stone’. You can see the word gamarri in sentence (1). There are many more endings too. To find out more about endings, see section 2.

Because endings are important, sentences in this description of Ganggalida grammar will be written with their words divided up into parts, like in (3). The Clitic is shown with ‘=’ before it, and there are short labels for the endings, on the line below the Ganggalida words. (To find about more about the short labels for endings, see section 3.)

(3) Dangga‐ra=ngga thaldij‐a gamarr‐i.

man‐ABS=3sg(NTR.PRES) stand on‐IND stone‐LOC

‘The man is standing on the stone’

The order of words

In English, the order of words is very important. There is a big difference between the goanna eats the crab and the crab eats the goanna. It is an interesting fact that in many of the world’s languages, including Ganggalida, the order of words is much less important than in English. An example is sentence (4).

(4) Jagarrangu=gadi diyaj‐a warrun‐ki

crab(ABS)=TR.PRES(3sgS.3sgO) eat‐IND goanna‐ERG

‘The goanna eats the crab’

In (4), the words are literally ‘crab eat goanna’, but the sentence means ‘the goanna eats the crab’. In Ganggalida this is possible, because the word warrunki ‘goanna’ has an ending ‐ki which tells you that the goanna is the Subject — it is the one which is doing the action.

You can find out much more about Ganggalida sentences in section 3, though to understand section 3, you’ll need to know about word endings first. Endings are discussed in section 2.

2. How to make words — stems and endings

In Ganggalida, almost all words are made up of at least two parts. For example, the word for ‘man’ is danggara, which is made up of dangga‐ and ‐ra, and the word ngawuwa ‘dog’ is made up of ngawu‐ and ‐wa. The first part is called a stem, like the stem of a plant. The parts after the stem are called endings.

To understand how words work in Ganggalida, it is useful to divide them into stems and endings. For example, to say ‘for the man’ you use the same stem dangga‐ but a

different ending ‐ntha to make the word danggantha ‘for the man’. To say ‘for the dog’ you use the stem ngawu‐ and the ending ‐ntha to make the word ngawuntha ‘for the dog’.

When Ganggalida words are put together into sentences, a lot of the meaning is expressed by endings. Because the endings are a vital part of Ganggalida grammar, this discussion of Ganggalida grammar will mention them very often. And because of that, it will be helpful to give the endings specific names, like Absolutive and Dative. The names will be especially useful when we discuss more complex parts of Ganggalida grammar in section 3. They also help when we want to compare Ganggalida with other languages of Australia and the world.

2.1 Stems and endings for nouns, adjectives and determiners

The endings on nouns, adjectives and determiners in Ganggalida can help to express who is doing what in an action. Or they can help to express whether an action is happening in a certain place, or if someone is going to that place or coming away from it. They can express what belongs to someone, or what someone has or doesn’t have. And they can express whether the noun, adjective or determiner is naming just one person or thing, or two of them, or many of them.

One of the complex aspects of Ganggalida is that endings have many different forms. Just like the moon looks different on different days of the month, the endings have different appearances on different kinds of stems. For that reason, I will list the many forms of each ending, so that you can see how it appears and changes.

In the following sections you can read about the most common endings for nouns, adjectives and determiners. For each ending, there is a short description of what it is used for and a full description of its different forms.

Forms of the Absolutive ending

used to organise the dictionary — you can look up Ganggalida words by looking for their Citation Form.

The Absolutive ending has six different forms: ‐ra, ‐wa, ‐ya, ‐da, ‐ga and ‐a. Which one you use depends on the stem, for example the stem dangga‐, which means ‘man’, uses the Absolutive form ‐ra, but the stem ngawu‐ ‘dog’ uses the Absolutive form ‐wa. To know which form of the ending is appropriate, you need to look at the last sound of the stem. For example, Table 1 shows you stems that end with consonants. The stem gamarr‐ means ‘stone’. It ends with the sound rr and uses the form ‐a of the Absolutive ending. That tells you that any stem in Ganggalida which ends with the rr sound will use the Absolutive form ‐a.

Meaning Full Absolutive word form Stem Ending

‘stone’ gamarra gamarr‐ ‐a

‘spear’ miyarlda miyarl‐ ‐da

‘head’ nalda nal‐ ‐da

‘tooth’ damanda daman‐ ‐da

‘my’ ngijinda ngijin‐ ‐da

‘meat’ yarlbuda yarlbuth‐ ‐da

‘strange’ warlngida warlngij‐ ‐da

‘boomerang’ wangalga wangalg‐ ‐a

‘word’ gangga gang‐ ‐ga

Table 1. Absolutive word forms for stems ending with consonants

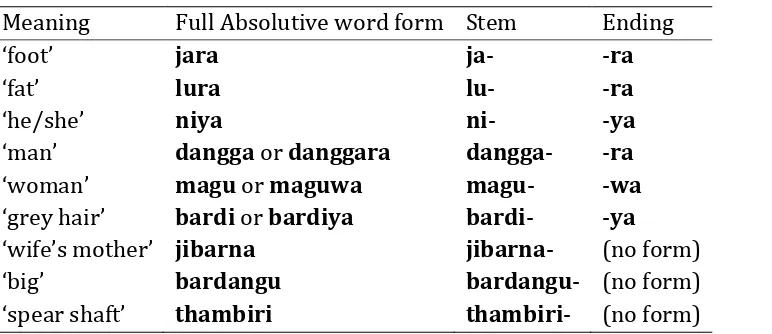

Table 2 shows stems that end with vowels. When the stem ends with a vowel, short stems and long stems behave differently: stems with one syllable must take their ending, stems with two syllables can take their ending, and stems with three or more syllables take no ending.

Meaning Full Absolutive word form Stem Ending

‘foot’ jara ja‐ ‐ra

‘fat’ lura lu‐ ‐ra

‘he/she’ niya ni‐ ‐ya

‘man’ dangga or danggara dangga‐ ‐ra

‘woman’ magu or maguwa magu‐ ‐wa

‘grey hair’ bardi or bardiya bardi‐ ‐ya

‘wife’s mother’ jibarna jibarna‐ (no form)

‘big’ bardangu bardangu‐ (no form)

‘spear shaft’ thambiri thambiri‐ (no form)

A small number stems that end with ng have two alternative Absolutive forms. One form uses the ending ‐ga. The other form just removes the ng from the end of the stem

Meaning full Absolutive word Stem Ending

‘southwest’ balungga or balu balung‐ ‐ga, or remove ng ‘southeast’ larlungga or larlu larung‐ ‐ga, or remove ng

‘northeast’ lilungga or lilu lilung‐ ‐ga, or remove ng

‘northwest’ jirrgurlungga or jirrgurlu jirrgurlung‐ ‐ga, or remove ng

Table 3. Stems ending with ng, which have alternative Absolutive word forms

The stem ngimirlung‐ means ‘morning’. To create its Absolutive word form, the ng is always removed, to make the form ngimirlu. Finally, the stem dathin‐ means ‘that’ or ‘there’. It has two alternative Absolutive word forms: dathina or dathinda.

Forms of the Dative ending

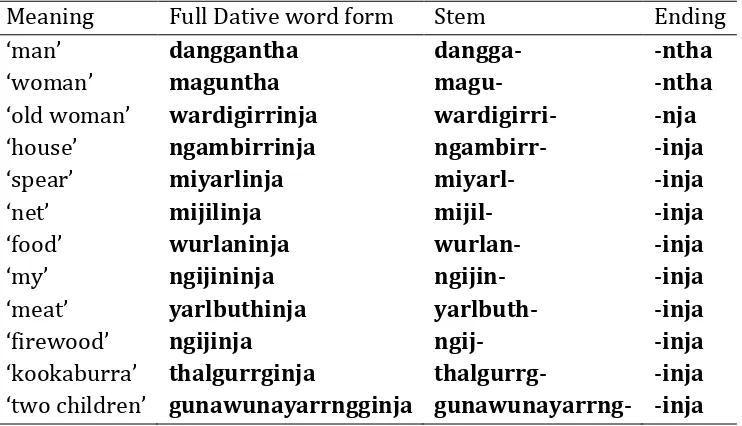

Words with a Dative ending have several uses in Ganggalida, including indicating who something is for. For example, the stem magu‐ ‘woman’ plus the Dative ending ‐ntha gives the full Dative word form maguntha which can mean ‘for the woman’. The Dative ending has the form ‐ntha after a stem that ends with a or u. It has the form ‐nja after a stem that ends with i, and the form ‐inja after a stem that ends with a consonant. Examples are shown in Table 4.

Meaning Full Dative word form Stem Ending

‘man’ danggantha dangga‐ ‐ntha

‘woman’ maguntha magu‐ ‐ntha

‘old woman’ wardigirrinja wardigirri‐ ‐nja

‘house’ ngambirrinja ngambirr‐ ‐inja

‘spear’ miyarlinja miyarl‐ ‐inja

‘net’ mijilinja mijil‐ ‐inja

‘food’ wurlaninja wurlan‐ ‐inja

‘my’ ngijininja ngijin‐ ‐inja

‘meat’ yarlbuthinja yarlbuth‐ ‐inja

‘firewood’ ngijinja ngij‐ ‐inja

‘kookaburra’ thalgurrginja thalgurrg‐ ‐inja

‘two children’ gunawunayarrngginja gunawunayarrng‐ ‐inja

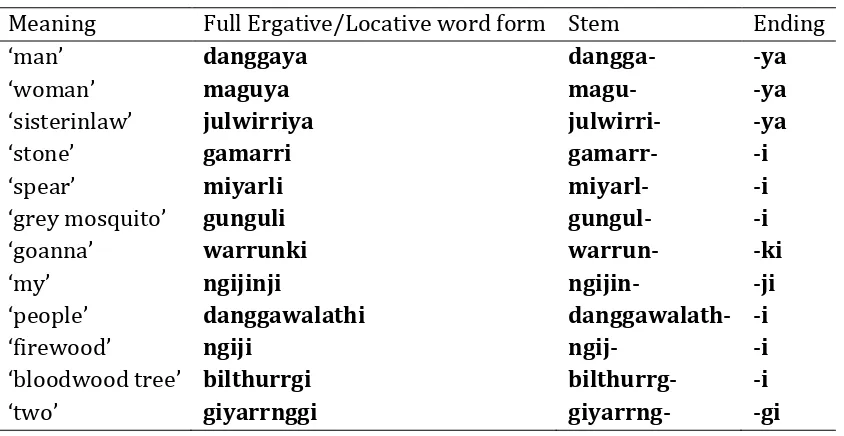

Forms of the Ergative and Locative endings

Words with the Ergative ending can be used to show who is doing an action — the Subject of the sentence. For example, in the sentence ‘the goanna eats the crab’, the goanna is doing the action, it is the Subject, and so the stem warrun‐ ‘goanna’ would have the Ergative ending ‐ki. The Ergative ending has the form ‐ya after a stem that ends with a vowel, and the forms ‐i, ‐gi, ‐ki or ‐ji after stems that end with consonants. The Locative ending is exactly the same. Words with the Locative ending can be used to express where an action takes place. For example, to say ‘on the stone’, the stem gamarr‐ ‘stone’ would have the Locative ending ‐i.

Meaning Full Ergative/Locative word form Stem Ending

‘man’ danggaya dangga‐ ‐ya

‘woman’ maguya magu‐ ‐ya

‘sisterinlaw’ julwirriya julwirri‐ ‐ya

‘stone’ gamarri gamarr‐ ‐i

‘spear’ miyarli miyarl‐ ‐i

‘grey mosquito’ gunguli gungul‐ ‐i

‘goanna’ warrunki warrun‐ ‐ki

‘my’ ngijinji ngijin‐ ‐ji

‘people’ danggawalathi danggawalath‐ ‐i

‘firewood’ ngiji ngij‐ ‐i

‘bloodwood tree’ bilthurrgi bilthurrg‐ ‐i

‘two’ giyarrnggi giyarrng‐ ‐gi

Table 5. Ergative & Locative word forms

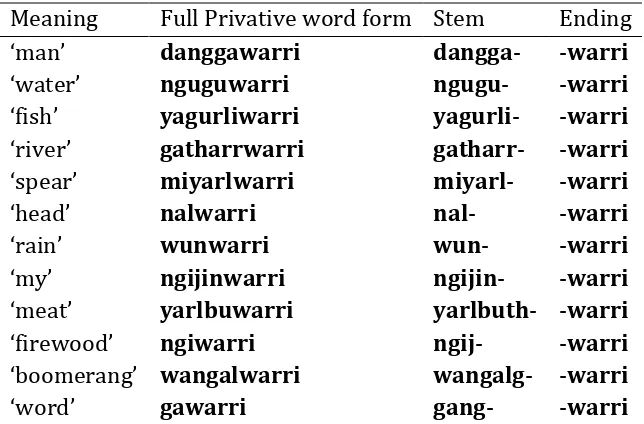

Forms of the Privative ending

The Privative ending is ‐warri. Words with the Privative ending can express what is missing, or something that someone doesn’t have, a bit like the English ending ‐less in waterless. For example, the stem ngugu‐ means ‘water’. The word nguguwarri means ‘no water’ or ‘without water’, like in that place has no water or he left without any water.

Meaning Full Privative word form Stem Ending ‘man’ danggawarri dangga‐ ‐warri

‘water’ nguguwarri ngugu‐ ‐warri

‘fish’ yagurliwarri yagurli‐ ‐warri

‘river’ gatharrwarri gatharr‐ ‐warri

‘spear’ miyarlwarri miyarl‐ ‐warri

‘head’ nalwarri nal‐ ‐warri

‘rain’ wunwarri wun‐ ‐warri

‘my’ ngijinwarri ngijin‐ ‐warri

‘meat’ yarlbuwarri yarlbuth‐ ‐warri

‘firewood’ ngiwarri ngij‐ ‐warri

‘boomerang’ wangalwarri wangalg‐ ‐warri

‘word’ gawarri gang‐ ‐warri

Table 6. Privative word forms

Forms of the Proprietive ending

The opposite of the Privative is the Proprietive. Words with the Proprietive ending can express what is there, or something that someone has. For example, the word ngawuwurlu means ‘with a dog’ or ‘having a dog’. The Proprietive ending has several forms. After a stem that ends with a vowel, it has the form ‐wurlu, except that after a stem which ends with u and has three or more syllables it has the form ‐rlu. After consonants it has the

forms ‐urlu, ‐gurlu, ‐ kurlu or ‐jurlu.

Meaning Full Proprietive word form Stem Ending ‘boy’ marnduwarrawurlu marnduwarra‐ ‐wurlu

‘dog’ ngawuwurlu ngawu‐ ‐wurlu

‘big’ bardangurlu bardangu‐ ‐rlu

‘old woman’ wardigirriwurlu wardigirri‐ ‐wurlu

‘rock’ gamarrurlu gamarr‐ ‐urlu

‘spear’ miyarlurlu miyarl‐ ‐urlu

‘tree’ diwalurlu diwal‐ ‐urlu

‘plant food’ wurlankurlu wurlan‐ ‐kurlu

‘my’ ngijinjurlu ngijin‐ ‐jurlu

‘meat’ yarlbuthurlu yarlbuth‐ ‐urlu

‘firewood’ ngijurlu ngij‐ ‐urlu

‘boomerang’ wangalgurlu wangalg‐ ‐urlu

‘word’ ganggurlu gang‐ ‐gurlu

Forms of the Ablative ending

Words with the Ablative ending can be used to express where something or someone is coming from. For example, to say ‘from the camp’, the stem natha‐ ‘camp’ would have the Ablative ending ‐naba, to form the Ablative word nathanaba. After a stem that ends with a vowel, the Ablative ending has the form ‐naba. After consonants it has the

forms ‐inaba, ‐kinaba, ‐ginaba or ‐jinaba.

Meaning full Ablative word form Stem Ending

‘camp’ nathanaba natha‐ ‐naba

‘water’ ngugunaba ngugu‐ ‐naba

‘fish’ yagurlinaba yagurli‐ ‐naba

‘stone’ gamarrinaba gamarr‐ ‐inaba

‘spear’ miyarlinaba miyarl‐ ‐inaba

‘net’ mijilinaba mijil‐ ‐inaba

‘food’ wurlankinaba wurlan‐ ‐kinaba

‘my’ ngijinjinaba ngijin‐ ‐jinaba

‘meat’ yarlbuthinaba yarlbuth‐ ‐inaba

‘firewood’ ngijinaba ngij‐ ‐inaba

‘mud’ mardalginaba mardalg‐ ‐inaba

‘morning’ ngimirlungginaba ngimirlung‐ ‐ginaba

Table 8. Ablative word forms

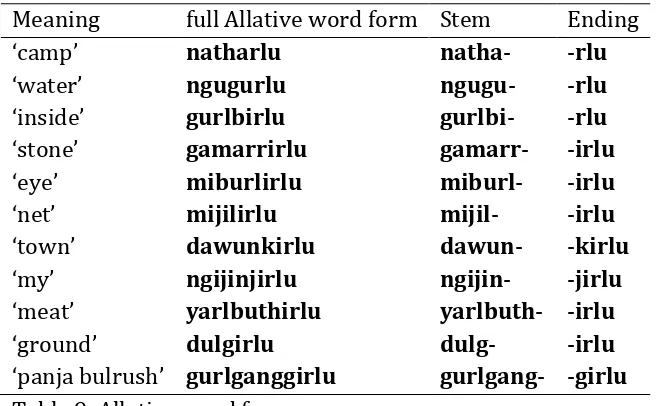

Forms of the Allative ending

Words with the Allative ending can be used to express where something or someone is going to. For example, to say ‘to the camp’, the stem natha‐ ‘camp’ would have the Allative ending ‐rlu, to form the Allative word natharlu. After a stem that ends with a vowel, the Allative ending has the form ‐rlu. After consonants it has the forms ‐irlu, ‐kirlu, ‐girlu

or ‐jirlu.

Meaning full Allative word form Stem Ending

‘camp’ natharlu natha‐ ‐rlu

‘water’ ngugurlu ngugu‐ ‐rlu

‘inside’ gurlbirlu gurlbi‐ ‐rlu

‘stone’ gamarrirlu gamarr‐ ‐irlu

‘eye’ miburlirlu miburl‐ ‐irlu

‘net’ mijilirlu mijil‐ ‐irlu

‘town’ dawunkirlu dawun‐ ‐kirlu

‘my’ ngijinjirlu ngijin‐ ‐jirlu

‘meat’ yarlbuthirlu yarlbuth‐ ‐irlu

‘ground’ dulgirlu dulg‐ ‐irlu

‘panja bulrush’ gurlganggirlu gurlgang‐ ‐girlu

Table 9. Allative word forms

Forms of the Genitive ending

Words with the Genitive ending can be used to express who owns or possesses something. For example to say ‘the man’s dog’, you could put the Genitive ending ‐garra on the stem

dangga‐ ‘man’, and say danggagarra ngawuwa. After a stem that ends with a vowel, the Genitive ending has the form ‐garra. After consonants it has the forms ‐wagarra

or ‐bagarra.

Meaning full Genitive word Stem Ending ‘little girl’ ngurliwagarra ngurliwa‐ ‐garra

‘woman’ magugarra magu‐ ‐garra

‘old man’ balalanyigarra balalanyi‐ ‐garra

‘spear’ miyarlwagarra miyarl‐ ‐wagarra

‘tree’ diwalwagarra diwal‐ ‐wagarra

‘horse’ yarramanbagarra yarraman‐ ‐bagarra

‘my’ ngijinbagarra ngijin‐ ‐bagarra

‘meat’ yarlbuwagarra yarlbuth‐ ‐wagarra

‘kookaburra’ thalgurrwagarra thalgurrg‐ ‐wagarra

‘two men’ danggayarrmbagarra danggayarrng‐ ‐bagarra

Table 10. Genitive word forms

A second use for the Genitive ending is to express what something is near to. To do that, the Genitive ending has a special form that has an extra n on it, which gets followed by a

ngamathu‐ ‘mother’ plus the special Genitive form ‐garran‐ plus the Locative ending ‐ji, to make the word ngamathugarranji.

Forms of the Stative ending

Ganggalida determiners and time words like ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow’ can appear with a Stative ending after the stem. Words with a Stative ending can then have two forms: an Absolutive form, which will end with ‐ma, or an Ergative/Locative form that ends

with ‐mang‐ plus the Ergative/Locative ending ‐gi. Examples are shown in Table 11 and Table 12.

Meaning Full Stative Absolutive word Stem Ending

‘this’ danma dan‐ ‐ma

‘my’ ngijinma ngijin‐ ‐ma

‘now’ yanma yan‐ ma

Table 11. Stative Absolutive word forms

Meaning Full Stative Ergative/Locative word Stem Endings

‘some’ jangkinmanggi jangkin‐ ‐mang‐gi

‘those two’ dathinkiyarrmanggi dathinkiyarrng‐ ‐mang‐gi

‘tomorrow’ balmbimanggi balmbi‐ ‐mang‐gi

‘yesterday’ barrunthamanggi barruntha‐ ‐mang‐gi

Table 12. Stative Ergative/Locative word forms

Forms of the Dual ending

Any noun in Ganggalida can name a single person or thing, or it can name many. For example, the noun danggara is made of the stem dangga‐ ‘man’ and the Absolutive ending ‐ra. It can mean ‘man’, or it can mean ‘men’. It is also possible to be more specific. The Dual ending tells you that someone is talking about exactly two people or things. The Dual ending has the forms ‐yarrng‐, ‐iyarrng‐, ‐kiyarrng‐ and ‐jiyarrng. It gets followed by other endings, like the Absolutive ending ‐ga.

Meaning Full Dual Absoltive word Stem Endings

‘man’ danggayarrngga dangga‐ ‐yarrng‐ga

‘older sister’ yagugathuyarrngga yagugathu‐ ‐yarrng‐ga

‘man’s sister’ balgajiyarrngga balgaji‐ ‐yarrng‐ga

‘hand’ marliyarrngga marl‐ ‐iyarrng‐ga

‘unmarried person’ ngumaliyarrngga ngumal‐ ‐iyarrng‐ga

‘that’ dathinkiyarrngga dathin‐ ‐kiyarrng‐ga

‘my’ ngijinjiyarrngga ngijin‐ ‐jiyarrng‐ga

Table 13. Dual Absolutive word forms

Forms of the Plural ending

The Plural ending tells you that someone is talking specifically about three or more people or things. The Plural ending has the forms ‐walath‐ and ‐balath. It gets followed by other endings, like the Absolutive ending ‐da, or the Ergative/Locative ‐i.

Meaning Full Plural Ergative/Locative word Stem Endings ‘man’ danggawalathi dangga‐ ‐walath‐i

‘woman’ maguwalathi magu‐ ‐walath‐i

‘my’ ngijinbalathi ngijin‐ ‐balath‐i

Table 14. Plural Ergative/Locative word forms

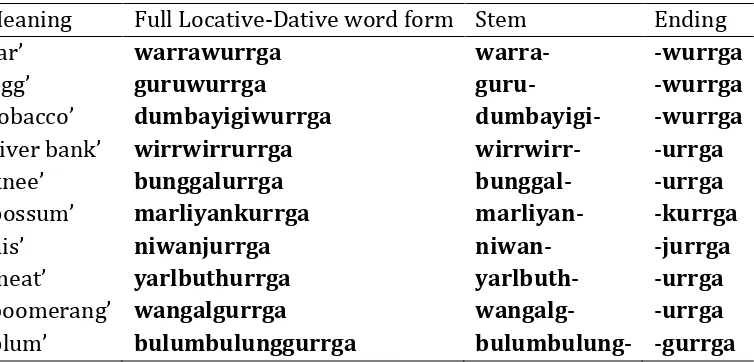

Forms of the combined Locative‐Dative ending

In section 3.11 we will see that in some complex sentences, some words have a combined Locative‐Dative ending:

Meaning Full Locative‐Dative word form Stem Ending

‘far’ warrawurrga warra‐ ‐wurrga

‘egg’ guruwurrga guru‐ ‐wurrga

‘tobacco’ dumbayigiwurrga dumbayigi‐ ‐wurrga

‘river bank’ wirrwirrurrga wirrwirr‐ ‐urrga

‘knee’ bunggalurrga bunggal‐ ‐urrga

‘possum’ marliyankurrga marliyan‐ ‐kurrga

‘his’ niwanjurrga niwan‐ ‐jurrga

‘meat’ yarlbuthurrga yarlbuth‐ ‐urrga

‘boomerang’ wangalgurrga wangalg‐ ‐urrga

‘plum’ bulumbulunggurrga bulumbulung‐ ‐gurrga

2.2 Singular, plural, subjects, objects, and more

Every language has its own way of organising its words and sentences, and to understand how words work, it helps to understand how the language organises itself. For example, one way that English organises itself is in terms of singular and plural. You need to pay attention to singular and plural in English when you choose whether to use the word dog or dogs. This section talks a little more about the organisation of Ganggalida. It introduces some important ideas, and ways to discuss them.

The idea of Number

The term Number is used to talk about ideas like Singular and Plural. In Ganggalida, Number is a little more complex than in English. In Ganggalida, one thing is Singular, two things are Dual and three or more things are Plural. Sometimes, it will also be useful to talk about Non‐singular, which is two or more. A summary is in Table 16.

Abbreviation

One person or thing Singular sg Two people or things Dual du More than two Plural pl More than one Non‐singular nonsg Table 16. Number in Ganggalida

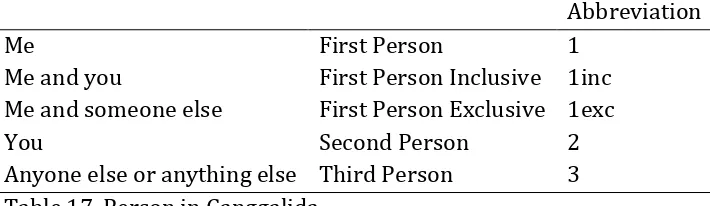

The idea of Person

When we speak, we can talk about ourselves, or about the person we’re speaking to, or about other people or things. The idea of Person is concerned with these choices, and you can see a summary in Table 17.

Abbreviation

Me First Person 1

Me and you First Person Inclusive 1inc Me and someone else First Person Exclusive 1exc

You Second Person 2

Anyone else or anything else Third Person 3 Table 17. Person in Ganggalida

First Person is when you mention yourself, for example in English, it’s when you use the words I or me. Second Person is when you mention the person you’re speaking to. In English, it’s when you use the word you. Third Person is when you mention anyone or anything else. There is one more issue: in English, the word us can mean ‘me and you’ or ‘me and someone else’. In Ganggalida, those two meanings are kept distinct. The meaning ‘me and you’ is called First Person Inclusive. The meaning ‘me and someone else’ is First Person Exclusive.

The idea of Subjects, Objects and Goals

The Subject of a sentence is the one who is doing the action. The Object of a sentence is the one who is having the action done to them. In Ganggalida, some sentences have a person or thing which we can call the Goal. One kind of Goal is someone who receives something, or who benefits for the action. You can find out more about Goals in sections 3.5 and 3.6.

The idea of Transitivity

Subjects, Objects and Goals influence how Ganggalida words are put together. An important idea related to them is Transitivity. Sentences that have a Subject and no Object, like the man sleeps are called Intransitive sentences. Sentences that have a Subject and an Object, like the goanna eats the crab, are called Transitive sentences. In addition to Intransitive and Transitive sentences, Ganggalida also has Semi‐transitive sentences, which have a Subject and a Goal. A summary is shown in Table 18. To learn more about when a sentence has an Object and when it has a Goal, see section 3.5.

Transitive sentence Subject & Object Semi‐transitive sentence Subject & Goal Intransitive sentence Subject

Table 18. Basic sentence types in Ganggalida

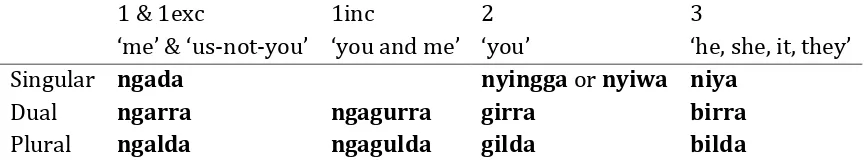

2.3 Stems and endings for pronouns

Pronouns are words like the English words you, me, him, them, us and your, my, his, their. In Ganggalida, they express information about Number (Singular, Dual, Plural) and Person (First Person, Second Person, Third Person), as well as some other information. In this section you can read about the forms of Ganggalida pronouns.

The Direct forms of pronouns

1 & 1exc

‘me’ & ‘us‐not‐you’ Singular ngada nyingga or nyiwa niya

Dual ngarra ngagurra girra birra

Plural ngalda ngagulda gilda bilda

Table 19. Direct forms of personal pronouns

1 & 1exc

‘me’ & ‘us‐not‐you’ Singular ngijuwa

or ngiju

ngumbara or ngumba

niwara or niwa

Dual ngarrawa ngagurruwa girrwara or girrwa

birrwara

or birrwa

Plural ngalawa ngaguluwa gilwara or gilwa

bilwara or bilwa

Table 20. Dative forms of personal pronouns

1 & 1exc

‘me’ & ‘us‐not‐you’ 1inc

‘you and me’

2 ‘you’

Singular ngijinji ngumbanji

Dual ngarrawanji ngagurruwanji girrwanji

Plural ngalawanji ngaguluwanji gilwanji

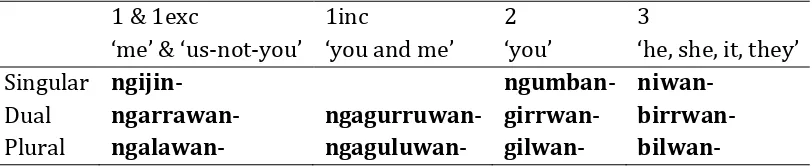

Stems for other endings

To make pronouns with any other ending, Ganggalida uses the stems in Table 22. The endings that can go on those stems are: Privative ‐warri, Proprietive ‐jurlu,

Ablative ‐jinaba, Allative ‐jirlu, Genitive ‐bagarra, Dual ‐jiyarrng‐ and Plural ‐balath‐. Those endings have the same use with pronouns as they have with nouns, adjectives and determiners. For example, to say ‘without me’ you would use the First Person singular stem

ngijin‐ plus the Privative ending ‐warri, to make the word ngijinwarri. To find out more about the uses of those endings, see section 3.1.

1 & 1exc

‘me’ & ‘us‐not‐you’

Singular ngijin‐ ngumban‐ niwan‐

Dual ngarrawan‐ ngagurruwan‐ girrwan‐ birrwan‐

Plural ngalawan‐ ngaguluwan‐ gilwan‐ bilwan‐

Table 22. Stems of personal pronouns for use with other endings stems are: Absolutive ‐da, Ergative & Locative ‐ji, Dative ‐inja, Privative ‐warri,

Proprietive ‐jurlu, Ablative ‐jinaba, Allative ‐jirlu, Genitive ‐bagarra, Dual ‐jiyarrng‐ and Plural ‐balath‐. To find out more about the uses of those endings, see section 3.1.

1 & 1exc

‘me’ & ‘us‐not‐you’

Singular ngijin‐ ngumban‐ niwan‐

Dual ngarrawan‐ ngagurruwan‐ girrwan‐ birrwan‐

Plural ngalawan‐ ngaguluwan‐ gilwan‐ bilwan‐

Table 23. Stems of possessive pronouns, for use with all endings

The Stative forms of pronouns

The Stative ending ‐ma can appear on pronoun stems, as in Table 24. To find out about the Stative ending on other words, see section 2.1.

1 & 1exc

Singular nganhma nyima nima

Dual ngarrma ngagurrma girrma birrma

Plural ngalma ngagulma gilma bilma

Table 24. Stative Direct forms of personal pronouns

2.4 Stems and endings for Verbs

The verb expresses what kind of action is happening. Ganggalida verbs can be Transitive, like balatha ‘hit’ and gurrija ‘see, or look at’, or Intransitive like thaatha ‘go walkabout’ and jawija ‘run’, or Semi‐transitive like lardija ‘wait for’ and gamburija ‘talk to’.

In Ganggalida, verb stems all end with the sounds th or j. The endings that come after the stems are used to show that a sentence is a statement (telling you about of a verb is made either by adding the ending ‐a or by removing the final th or j sound from the stem. For example, with the stem balath‐ ‘hit’, you can make the Indicative form either by adding ‐a, to get balatha, or by removing the final th sound, to get bala. Examples are shown in Table 25.

meaning full Indicative verb stem ending

Transitive ‘hit’ balatha or bala balath‐ ‐a, or remove th Transitive ‘look at’ gurrija or gurri gurrij‐ ‐a, or remove j

Semi‐transitive ‘wait for’ lardija or lardi lardij‐ ‐a, or remove j

Intransitive ‘go’ thaatha or thaa thaath‐ ‐a, or remove th

Intransitive ‘run’ jawija or jawi jawij‐ ‐a, or remove j

Table 25. Indicative verb forms, for statements

The Imperative forms of verbs

meaning full Imperative verb stem ending Transitive ‘hit’ balaga balath‐ ‐ga Transitive ‘look at’ gurriga ngudij‐ ‐ga

Semi‐transitive ‘wait for’ lardija lardij‐ ‐a

Intransitive ‘go’ thaatha thaath‐ ‐a

Intransitive ‘run’ jawija jawij‐ ‐a

Table 26. Imperative verb forms, for commands

The Hortative forms of verbs

The Hortative form of a verb is for making polite commands. The Hortative form is made by adding the ending ‐gi to Transitive verb stems, or by adding ‐i to Semi‐transitive and

Intransitive verb stems. The g in the ‐gi ending replaces the final th or j sound of the stem.

meaning full Hortative verb stem ending

Transitive ‘hit’ balagi balath‐ ‐gi

Transitive ‘look at’ gurrigi ngudij‐ ‐gi

Semi‐transitive ‘wait for’ lardiji lardij‐ ‐i

Intransitive ‘go fishing’ ngagathi ngagath‐ ‐i

Intransitive ‘go hunting’ wambalmaji wambalmaj‐ ‐i

Table 27. Hortative verb forms, for polite commands

The Desiderative forms of verbs

The Desiderative form of a verb is for expressing wishes, desires and possibilities. It is made by adding the ending ‐da to the verb stem. The d in the ‐da ending replaces the final th or j sound of the stem.

meaning full Desiderative verb stem ending Transitive ‘hit’ balada balath‐ ‐da Transitive ‘look at’ gurrida ngudij‐ ‐da

Semi‐transitive ‘wait for’ lardida lardij‐ ‐da

Intransitive ‘go fishing’ ngagada ngagath‐ ‐da

Intransitive ‘go’ warrada warraj‐ ‐da

Negative forms

Verbs can also have specifically Negative endings, to describe what doesn’t, won’t, can’t or shouldn’t happen. The Negative forms of balath‐ ‘hit’ and warraj‐ ‘go’ are summarised in Table 29 together with the positive forms. There are no Negative Hortative forms.

‘hit’ ‘go’

Positive Indicative balatha or bala warraja or warra

Imperative balaga warraja

Hortative balagi warraji

Desiderative balada warrada

Negative Indicative balatharri warrajarri

Imperative balana warrana

Desiderative balanada warranada Table 29. Summary of Positive and Negative verb forms

2.5 The main Clitic

Most sentences in Ganggalida have a Clitic which expresses information about Subjects, Object and Goals, and about when the action happens: in the past, present or future. The Clitic has no stem. Instead, it is made entirely from endings, and then it attaches itself to the end of other words. The Clitic has three main parts:

• Part A expresses information about the Person and Number of the Goal.

• Part B expresses information about the Person and Number of Subject and Objects. • Part C expresses information about when the action happens, and whether it really

happens or it only could have or should have happened. These ideas can be called Tense and Mood. Part III also expresses information about whether the sentence is Transitive or not.

To make the complete Clitic, you put the parts A, B and C together. This section goes though each part: A, B and C.

The forms for Part A of the Clitic

it is Singular, then the form of Part A of the Clitic is given in Table 30. The symbol ‘ø’ means “nothing”.

Goal: 1sg ‘me’ ‐thu‐ 2sg ‘you’ ‐ba‐ 3sg ‘him, her, it’ ‐rna‐ or ø

Table 30. Part A of the Clitic, for singular Goal

An example of a sentence with a First Person singular Goal is (5). You can see that the Clitic begins with ‐thu.

(5) Dathina=thu‐ganda mirralaya ngijuwa miyarl‐da.

That=1sgG‐TR.PST make(IND) 1sg.DAT spear‐ABS ‘That (man) made a spear for me.’

If the Goal is Non‐singular, then the form of Part A of the Clitic depends on the Goal’s Person and Number, and on whether the Subject of the sentence is Singular or Non‐singular.

Subject:

Singular Non‐singular

Goal: 1inc.du ‘me and you’ ‐gurruwa‐ ‐gurra‐

1inc.pl ‘me and you lot’ ‐guluwa‐ ‐gurra‐

1exc.du ‘us two, not you’ ‐ngarrawa‐ ‐ngarra‐

1exc.pl ‘us lot, not you’ ‐ngalawa‐ ‐ngarra‐

2du ‘you two’ ‐rrawa‐ ‐rrawa‐

2pl ‘you lot’ ‐lawa‐ ‐rrawa‐

3du ‘them two’ ‐wurruwa‐ ‐wurra‐

3pl ‘them lot’ ‐wuluwa‐ ‐wurra‐

Table 31. Part A of the Clitic, for Non‐singular Goal

The forms for Part B of the Clitic

Part B of the Clitic expresses information about the Subject and, if the sentence is

Transitive, about the Object. We can begin with cases where the sentence is Transitive. In those sentences, if the Subject is Singular, then the form of part B of the Clitic is given in Table 32. The grey square in Table 32 tells you that the combination of Third Person Singular Subject and First Person Singular Object never occurs, so the Clitic does not need to have a form for it.

Subject:

1sg ‘me’ 2sg ‘you’ 3sg ‘he, she, it’

Object: 1sg ‘me’ ‐nga‐ ‐nki‐

2sg/3sg ‘you, he, she, it’ ‐nga‐ ‐yi‐ ø

2du/3du ‘you two, them two’ ‐ngarrngu‐ ‐rrnguyi‐ ‐rrngu‐

2pl/3pl ‘you lot, them lot’ ‐nganbunga‐ ‐nbuyi‐ ‐nbu‐

Table 32. Part B of the Clitic for Transitive sentences, for Singular Subject

1inc.du

‘me & you’

2sg/3sg

‘you, he, she, it’ ‐gurr‐ ‐gul‐ ‐ngarr‐ ‐ngal‐ 2/3nonsg

‘you/them two/lot’ ‐gurr‐ ‐gul‐ ‐ngarru‐ ‐ngalu‐ (alternative) ‐gurru‐ ‐gurru‐ ‐ngarru‐ ‐ngarru‐

2sg/3sg ‘you, he, she, it’ ‐wurr‐ ‐wul‐ ‐rr‐ ‐l‐

2/3nonsg ‘you/them two/lot’ ‐wurru‐ ? ‐rr‐ ‐l‐

(alternative) ‐wurru‐ ‐wurru‐ ‐rru‐ ‐rru‐

Table 33. Part B of the Clitic for Transitive sentences, for Non‐singular Subject

Table 34 shows the forms of part B of the Clitic in a Transitive Imperative sentence, where the Subject will be Second Person: ‘you’, ‘you two’ or ‘you lot’.

Subject:

2sg ‘you’ 2du ‘you two’ 2pl ‘you lot’

Object: 1sgO ‘me’ ‐nki ? ‐nkul‐

3sgO ‘him, her, it’ ø ‐rr‐ ‐l‐

3duO ‘them two’ ‐rrngu ‐rru ‐rru‐

3plO ‘them lot’ ‐nbu ‐rru ?

Table 34. Part B of the Clitic for Transitive Imperative sentences

Table 35 shows the forms that are recorded, for part B of the Clitic in a Transitive Hortative sentence.

Object: 3sg ø

3du ‐yarr‐ 3pl ‐yal‐

Table 35. Part B of the Clitic for Transitive Hortative sentences

In Intransitive sentences, a different set forms are used for part B of the Clitic. If the Subject is Singular, then the forms depends on what the Tense/Mood is, shown in Table 36.

Subject:

1sg ‘me’ 2sg ‘you’ 3sg ‘he, she, it’ Tense/Mood: Present ‐ga‐ ‐nyi ‐ngga‐

Past ‐ga‐ ‐nyi‐ ø

Past Irrealis ‐ga‐ ‐nyi‐ ‐rni‐ or ‐ni‐

Future ‐tha‐ ‐yini‐ ‐rni‐ or ‐ni‐

Table 36. Part B of the Clitic for Non‐transitive sentences, for singular Subject

If the Subject is Non‐singular, then the form of part B of the Clitic depends whether the Sentence has a Non‐singular Goal or not. The forms are shown in Table 37.

Subject:

1inc.du

‘me & you’ with Non‐singular Goal ‐gurr‐ ‐gurr‐ ‐ngarr‐ ‐ngarr‐

otherwise ‐gurr‐ ‐gul‐ ‐ngarr‐ ‐ngal‐

with Non‐singular Goal ‐wurr‐ ‐wurr‐ ‐rr‐ ‐rr‐

otherwise ‐wurr‐ ‐wul‐ ‐rr‐ ‐l‐

Table 37. Part B of the Clitic for Non‐transitive sentences, for Non‐singular Subject

Subject:

2sg ‘you’ 2du ‘you two’ 2pl ‘you lot’ with Non‐singular Goal ø ‐wurr‐ ‐wurr‐

otherwise ø ‐rr‐ ‐l‐

Table 38. Part B of the Clitic for Non‐transitive Imperative sentences

Table 39 shows the forms that are recorded, for part B of the Clitic in a Transitive Hortative sentence.

Subject:

2/3nonsg ‘you/them two/lot’

Goal: 1inc.du ‘me and you’ ‐gurruwa‐

1inc.pl ‘me and you lot’ ‐guluwa‐

1exc.du ‘us two, not you’ ‐ngarrawa‐

1exc.pl ‘us lot, not you’ ‐ngalawa‐

2du ‘you two’ ‐rrawa‐

2pl ‘you lot’ ‐lawa‐

3du ‘them two’ ‐wurruwa‐

3pl ‘them lot’ ‐wuluwa‐

Table 40. Alternative to Parts A & B, for certain combinations of Goal/Subject

The forms for Part C of the Clitic

Part C of the Clitic expresses information about Tense/Mood. Table 41 shows the forms for Transitive sentences. Table 42 shows the forms for Intransitive and Semi‐transitive

sentences. In both cases, the forms can depend on the last sound of the first two parts of the Clitic.

Mood Tense After a After i, u or ø After l or rr Indicative & Desiderative Present ‐rri ‐garri ‐garri

Past ‐nda ‐ganda ‐ganda

Irrealis Past ‐ndi ‐gandi ‐gandi

Future ‐ndi ‐gandi ‐gandi

Imperative & Hortative Present ø ø ‐a

Table 41. Part C of the Clitic for Transitive sentences

Mood Tense After i After a, u or ø After l or rr Indicative & Desiderative Present ø ø or di ‐a or ‐adi

Past ‐ngga ‐yingga ‐ingga

Irrealis Past ‐nggi ‐yinggi ‐inggi

Future ‐nggi ‐yi ‐ayi

Imperative & Hortative Present ø ø ‐a

Table 42. Part C of the Clitic for Non‐transitive sentences

3 How to make sentences

This section describes how sentences are made in Ganggalida. The section is divided into many individual topics, starting with some simple cases, and gradually working up to the most complex sentences in the language. Throughout this section you will see many example sentences. Each sentence is numbered, so that it’s easy to talk about them. In the sentences, each word is broken into its parts and labeled, and there is a translation of the Ganggalida sentence into English at the bottom. The meanings of the labels are listed in Table 43, and you can read more about many of those ideas in sections 1 and 2.

ABL Ablative O Object

ABS Absolutive PRIV Privative

ALL Allative PROP Proprietive

DAT Dative nonsg Non‐singular Number DES Desiderative Mood NTR Non‐transitive

DIR Direct NEG Negative

DUAL Dual Number pl Plural Number du Dual Number PAST Past Tense

ERG Ergative PRES Present Tense

exc Exclusive Person PROP Proprietive FUT Future Tense PRIOR Prior Tense

G Goal REL Relative clause

GEN Genitive S Subject

HORT Hortative Mood sg Singular Number inc Inclusive Person STAT Stative

IND Indicative Mood TR Transitive IMP Imperative Mood 1 First Person IRR Irrealis Mood 2 Second Person

LOC Locative 3 Third Person

Table 43. Labels for endings and word forms

3.1 Describing what something is

(6) Ngijin‐da ngawu‐wa mirra‐ra.

my‐ABS dog‐ABS good‐ABS ‘My dog is good.’

(7) Ngijin‐ma ganthathu yarlbugaban‐da.

my‐STAT(ABS) father(ABS) good hunter‐ABS ‘My father is a good hunter.’

In sentence (8), the phrase ngijininja wanggurduntha describes a Goal — the person who something is for. Words that express the Goal have Dative endings.

(8) Danthin‐ma gunya yagurli ngijin‐inja wanggurdu‐ntha.

that‐STAT(ABS) small(ABS) fish(ABS) my‐DAT brother‐DAT ‘That small fish is for my brother.’

3.2 Describing where something is

To tell someone where something is, Ganggalida has sentences like (9)–(12). The thing that you’re talking about, like darrganbalda ‘frog’ in (9) or dangga ‘man’ in (10), has Absolutive endings. The place where it is, has Locative endings. These sentences use the verb wirdi, meaning ‘be at’, and they have a Clitic.

(9) Darrganbalda=ngga yarlgath‐i gamarr‐i wirdi.

frog=3sg(NTR.PRES) underneath‐LOC stone‐LOC be at(IND) ‘The frog is under the stone.’

(10) Dangga=ngga wirdi gurlbi gumangu‐ya.

man=3sg(NTR.PRES) be at(IND) inside(LOC) cave‐LOC ‘The man is inside the cave.’

The Clitic always attaches itself to the end of another word in the sentence. In almost all sentences, it attaches either to the first word, or to the end of the first Noun Phrase. A Noun Phrase is a group of words that describe a person, thing or place, like magugarra bayigi ‘the woman’s bag’ in (11).

(11) Magu‐garra bayigi=ngga gamarr‐i wirdi,

woman‐GEN bag(ABS) =3sg(NTR.PRES) stone‐LOC be at(IND)

minda‐ya gamarr‐i.

beside‐LOC stone‐LOC

‘The woman’s bag is at the stone, beside the stone.’

Sentence (12) shows an alternative way to say where something is, by using no verb and no Clitic.

(12) Magu‐garra bayigi gamarr‐i.

woman‐GEN bag(ABS) stone‐LOC ‘The woman’s bag is on the stone.’

3.3 Intransitive actions

Many sentences in Ganggalida are Intransitive. In those sentences, the Subject does the action, but without doing it to anyone or anything. Examples are shown in (13)–(17). In Intransitive sentences Subjects, like wunda in (13), have Absolutive endings. If the Subject is a Pronoun, then it appears in the Direct form, like nyingga in (14).

(13) Yulmburrinda=yingga wun‐da barljijbarljij‐a.

long time=(3sg)NTR.PAST rain‐ABS fall and fall‐IND ‘The rain’s been falling for a long time.’

(14) Rangarrwatha=nyi nying‐ga.

feel hot=2sgS(PRES) 2sg‐DIR ‘You’re feeling hot.’

Sometimes the Clitic will tell you exactly who is doing the action. In that case, the sentence often has no Subject Pronoun or Subject Noun Phrase. For example, the Clitic tells you that the Subject is ‘I’ (1sg) in (15) and (16), and ‘we two’ (1exc.nonsg) in (17).

(15) Gubarrmaja=ga‐yingga.

hurt self=1sg‐NTR.PAST ‘I hurt myself.’

(16) Yan‐da=ga‐yingga warraj‐a yarraman‐kurlu.

today=1sg‐NTR.PAST go‐IND horse‐PROP ‘I came today by horse.’

(17) Balmbi‐ya=ngarr‐ayi warraj‐a dawun‐kirlu.

yesterday‐LOC=1exc.nonsg‐NTR.FUT go‐IND town‐ALL ‘We two will go to town tomorrow.’

Sentences can include many other kinds of information. Examples are when the action happens, like yanda ‘today’ in (16), balmbiya ‘tomorrow’ in (17) and yulmburrinda ‘for a long time’ in (13), or with what, like yarramankurlu ‘with a horse; by horse’ in (16), or where, like dawunkirlu ‘to town’ in (17).

3.4 Transitive actions

Gangglida also has Transitive sentences and Semi‐transitive sentences, where the Subject does an action to someone or something else. In Transitive sentences, the Subject does the action to the Object. You can find out more about deciding whether a sentence should be Transitive or Semi‐transitive in section 3.5. Examples of Transitive sentences are shown in (18), (19) and (20). In Transitive sentences, if the Subject or Object is a pronoun, it will have a Direct form, like ngalda ‘we lot’ and kirra ‘you two’ in (18). Otherwise, Subjects have Ergative endings, and Objects have Absolutive endings.

(18) Ngal‐da=ngarru‐ganda gabath‐a girr‐a.

1pl‐DIR=1exc.duS.2nonsgO‐TR.PAST find‐IND 2du‐DIR ‘We lot found you two.’

(19) Magu‐ya=garri gurlij‐a gunawuna

woman‐ERG=TR.PRES(3sgS.3sgO) wash‐IND child(ABS) ‘The woman is washing the child.’

(20) Ganggarliju‐ya=gandi ni‐da gabath‐a

father’s father‐ERG=TR.FUT(3sgS.3sgO) name‐ABS find‐IND ‘The grandfather will find a name (for the baby)’

The verb wuuja ‘give’ is also Transitive: the Subject gives something to the Object. The words that describe the thing which is given, like jurlamarrgankurluya ‘turtle’ in (22), have two endings: Proprietive and Ergative.

(21) Ngarr‐a=ngarr‐gandi wuuj‐a nying‐ga thungal‐wurlu‐ya.

1exc.du‐DIR=1exc.duS.2sgO‐TR.FUT give‐IND 2sg‐DIR thing‐PROP‐ERG ‘We two will give you something.’

(22) Ngagurr‐a=gurru‐garri wuuj‐a jurlamarrgan‐kurlu‐ya

1inc.du‐DIR=1inc.duS.3nonsgO‐TR.PRES give‐IND turtle‐PROP‐ERG

dathin‐a jardi.

that‐ABS mob(ABS) ‘You and I give them lot turtle.’

(23) Ngamathu‐ya ganthathu‐ya=rr‐ganda wuuj‐a

mother‐ERG father‐ERG=3duS.3nonsgO‐TR.PAST give‐IND

kujiji kiyarrng‐ka.

young(ABS) two‐ABS

‘The mother and father give (food) to the young two.’

3.5 When to use Semi‐transitive sentences

Most of the time, if the Subject does an action to someone or something else, then the sentence is Transitive. But there are specific cases where the sentence will be

Semi‐transitive instead. This section discusses what the those cases are, and what the Semi‐transitive sentences look like.

The first case where Ganggalida uses Semi‐transitive instead of Transitive sentences is when the verb is a Middle verb. In the dictionary, Middle verbs are shown with the

abbreviation v.m. Some examples of Middle verbs are lardija ‘wait for’, gamburija ‘talk to’ and bulwija ‘be frightened of’. If the verb is a Middle verb, then the sentence is

Semi‐transitive, and the Subject acts on a Goal. Subjects have Absolutive endings and Goals have Dative endings:

(24) Dathin‐a=yingga lardij‐a ngugu‐ntha.

That‐ABS=(3sg)NTR.PAST wait‐IND water‐DAT ‘That fella waited for water.’

(25) Gamburij‐a=wurruwa‐yingga dathin‐kiyarrng‐inja.

In sentences with Middle verbs, Pronoun Subjects have the Direct form, like ngarra ‘we two’ in (26). Pronoun Goals have the Dative form, like niwa ‘him’ in (27).

(26) Ngarr‐a=ngarr‐ingga lardij‐a dathin‐inja jardi‐nja.

1exc.du‐DIR=1exc.duS.nonsgG‐NTR.PAST wait‐IND that‐DAT mob‐DAT

‘We two waited for that lot.’

(27) Niwa=rna‐nyi bulwij‐a.

3sgDAT=3sgG‐2sgS(NTR.PRES) be frightened of‐IND ‘You are frightened of him.’

The second case where Ganggalida uses Semi‐transitive instead of Transitive sentences is in sentences whose verbs have Negative endings. You can find more about those sentences in section 3.9.

The third case is when a verb has a Desiderative ending. In those sentences, there is the option of expressing the desire in a more gentle way, by making the sentence a

Semi‐transitive. Sentence (28) is an example of a Transitive Desiderative, and the second half of (29) is a Semi‐transitive Desiderative sentence.

(28) Badi‐da=thu‐rr‐garri yarlbu‐da.

carry‐DES=1sgG‐3duS.3sgO‐TR.PRES meat‐ABS ‘Those two ought to carry the meat for me’

(29) Ngawarri=ga‐di, ngugu‐ntha gurdama‐da=ga‐di.

thirsty(ABS)=1sgS‐NTR.PRES water‐DAT drink‐DES=1sgS‐NTR.PRES ‘I’m thirsty, I should drink water.’

The fourth case where Ganggalida uses Semi‐transitive instead of Transitive sentences is for certain combinations of who is doing what in the action. The deciding factor is the Person of Subject and Object/Goal (to remind yourself about Person, see section 2.2). Table 44 shows combinations of Subject, who is doing the action, and Object/Goal, which is having the action done to it, and shows whether the sentence needs to be Semi‐transitive.

Subject: 2

3

Object/Goal: 1 Semi‐transitive 1inc Semi‐transitive Semi‐transitive 1exc Semi‐transitive Semi‐transitive

2 Semi‐transitive

Table 44. Semi‐transitivity triggered by Person combinations

Examples of Semi‐transitive sentences, which are Semi‐transitive because of the Person of the Subject and Goal, are shown in (30)–(32). For example, in (30) the Subject is

dathinkiyarrngga ‘those two’, which is Third Person, and the action is done to ngijinji ‘me’ which is First Person. Because of that, the sentence must be Semi‐transitive.

(30) Dathin‐kiyarrng‐ga=thu‐rr‐a jinka ngijin‐ji.

That‐DUAL‐ABS=1sgG‐3du‐NTR.PRES follow(IND) 1sg‐LOC ‘Those two are following me.’

(31) Dathin‐a jardi=ba‐l‐ayi gurri ngumban‐ji.

That‐ABS mob(ABS)=2sgG‐3plS‐NTR.FUT see(IND) 2sg‐LOC ‘That lot will see you.’

(32) Jinkaj‐a=guluwa‐ni‐nggi ngaguluwan‐ji burldamurr‐i.

Follow‐IND=1inc.plG‐3sgS‐NTR.FUT 1inc.pl‐LOC three‐LOC

‘He will follow us three.’

3.6 Someone who possesses something can be a Goal

Sometimes, if someone in the sentence possesses something, they appear in the Clitic as a Goal. For example, in (33), ngumbaninja jibarnantha ‘your mother‐in‐law’ is possessed by ‘you’ (Second Person Singular), and so ‐ba appears in the Clitic, expressing a Second Person Singular Goal.

(33) Dan‐ma bijarrba=ba ngumban‐inja jibarna‐ntha.

this‐STAT(ABS) dugong=2sgG your‐DAT mother in law‐DAT ‘That dugong is for your mother‐in‐law.’