Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology

Tribhuvan University

Kathmandu, Nepal

Yam Bahadur Kisan

Gopal Nepali

Ethnographic Research Series - 13

Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology

Tribhuvan University

Preface and Acknowledgments

his Ethnographic Research Series proiles Nepal’s diferent ethnic and caste groups. It forms part of the larger Social Inclusion Atlas and Ethnographic Proile (SIA-EP) project recently undertaken by the Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology (CDSA) at Tribhuvan University. he broad objective of the SIA-EP research is to promote an informed understanding of Nepal’s social diversity by producing up to date, research-based information about its social, cultural and linguistic composition and the state of human and social development.

In addition to this Ethnographic Research Series, the SIA-EP project has three other interrelated components: the Nepal Social Inclusion Survey (NSIS), the Nepal Multidimensional Social Inclusion Index (NSII) (which is presented together with further analysis of national level data including the 2011 Census) and the Social Inclusion Atlas series. he latter provides information about Nepal’s social diversity and development status, in a series of geographic maps. It is hoped that the atlas series will help to make ethnographic information easily accessible to decision-makers, planners, researchers, students and the general public. It is a matter of pride for CDSA to have successfully completed this research project and to be launching this series of publications.

Nepal is well known for its social and cultural diversity. he 2011 Census lists some 125 ethnic and caste groups living in diferent parts of the country. Each group has its own distinct identity, language, history, religion and culture, much of which remains undocumented. his series of Ethnographic Research Proiles will help to bring a better understanding of Nepal’s social, cultural, economic and political diversity. In the irst phase of the research, CDSA studied 42 caste/ ethnic groups that are historically excluded. hese studies form the irst volume of the series. he department hopes to carry out similar studies of other caste/ ethnic groups in the country in the future.

Both the successful completion of the SIA-EP project and the publication of this Ethnographic Proile Series were made possible due to the hard work of around 200 individuals and the generous support of a number of organizations. We would like to express our gratitude to all of them. In particular, we would like to thank the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Nepal for providing the research funding through the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV), and the Copyright @ 2014

Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology Tribhuvan University

Published by

Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology (CDSA)

Tribhuvan University (TU) Kirtipur

Kathmandu, NEPAL Tel: 0977-1-4331852 Email: cdsatu@cdsatu.edu.np Website: http://www.cdsatu.edu.np

First Edition: March 2014 1000 Copies

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission.

ISBN: 978-9937-524-70-4

Cover photo: (Clockwise) A Badi man playing Tabala, a main musical instrument of Badi, sulpa and ishing. All photos used in this book are taken by Gopal Nepali.

Design and layout by: Verve Media Pvt. Ltd.

Printed in Nepal by: Trigun Printing Press Pvt. Ltd. Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology

Tribhuvan University Kathmandu, Nepal

Ethnographic Research Series - 13

Ethnographic Research Series - 13

Social Inclusion Research Fund (SIRF) for managing funding and facilitating the research. Heartfelt thanks go to Kristine H. Storholt and Lena Hasle at the Embassy for their valuable support and insightful feedback. We would also like to thank SIRF Screening Committee Chair Prof. Ganesh Man Gurung and other Members for providing the valuable feedbacks and supporting the research. hanks also go to Prof. Shiva Kumar Rai, erstwhile Member of the National Planning Commission, for chairing the Advisory Committee for SIA-EP Research. We would also like to thank Prof. Surya Lal Amatya, erstwhile Rector of Tribhuvan University, for giving us permission to undertake this research project. We would like to thank the National Planning Commission and the Central Bureau of Statistics for making available data on selected variables from the 2011 Census sorted by Village Development Committee (VDC) and by ethnic / caste group. We extend our sincere gratitude to the Department of Survey for providing us with a spatial digital database of Nepal, and to the Central Department of Geography at Tribhuvan University for providing us with GIS software. Special thanks go to Prof. K.K. Mishra at the Anthropological Survey of India for hosting a seminar for the SIA-EP research team, sharing experience of ethnographic surveys in India and advising on their relevance to our own Nepal-based research. In addition, we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude and very special thanks to Dr. Manju hapa Tuladhar, and Sita Rana, Lead Advisor and Project Manager, Swasti Pradhan, Leena Bista and Sushila Moktan at the SIRF Secretariat, SNV who provided much invaluable support throughout the project life cycle.

We must also acknowledge the community leaders and community members from the 42 ethnic and caste groups we interacted with during ield trips, without whom, the publication of this series of studies would not have been possible. We thank community members for sparing time to talk to our researchers about their history, culture, society, economy, politics, human development and inclusion / exclusion status during the peak agricultural season. We also thank them for providing researchers with such warm and open hospitality. hanks also go to the many individual respondents and organizations that helped to make the ethnographic ieldwork meaningful. Particular thanks go to representatives of Dalit organizations, the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN), the National Foundation for Development of Indigenous Nationalities (NFDIN), Madhesi organizations, women’s organizations and others. We are also grateful to the academics and professionals who participated in a series of consultation workshops and provided valuable comments and suggestions for enhancing the quality of the research.

We thank our reviewers David Holmberg and Kathryn March at Cornell University, USA, Gérard Toin at National Sceintiic Research Center, Paris and Mark Turin and Sara Shneiderman at Yale University, USA for their valuable comments and suggestions, and copy-editors Andrew Steele, Wayne Redpath and Seema Rajouria for their meticulous editing work. Finally, we would like to express our appreciation to the SIA-EP support team, Sidharth Sherpa, Urmila hapa, Jeena Joshi, Krishna Gurung, Saugat Adhikari and Pushpa Gurung, for their hard work and eiciency throughout the project period. Although this series of proiles may have limitations and gaps, it will certainly contribute to a more thorough understanding of the richly diverse nature of Nepali society.

Om Gurung, Ph. D. Mukta S. Tamang, Ph. D.

Professor and Head, CDSA, TU Director, SIA-EP Research Coordinator, SIA-EP Research

March 2014

Abbreviation

CBS : Central Bureau of Statistics

CDO : Chief District Oice

CDSA : Central Department of Sociology and Anthropology

FGD : Focus Group Discussion

HH : Household Survey

MA : Master of Arts

KII : Key Informant Interview

NSIS : Nepal Social Inclusion Survey

SIA-EP : Social Inclusion Atlas and Ethnographic Proile Project

SIRF : Social Inclusion Research Fund

SLC : School Leaving Certiicate

VDC : Village Development Committee

Table of Contents

Chapter I: Introduction ... 1-5

1.1 Introduction ... 3

1.2 Methodology ... 5

Chapter II: Demography, Settlement and Territory ... 7-16 2.1 Settlements of Badi in Surkhet ... 9

2.2 History of settlement ... 10

2.3 History of migration ... 12

2.4 House types of Badi ... 13

2.5 Household Amenities ... 14

Chapter III: History, Society and Culture ... 17-41 3.1 History and myth of the origination of Badi ... 19

3.2 Society ... 21

3.2.1 Family ... 21

3.2.2 Family Structure ... 22

3.3 Marriage ... 23

3.3.1 Elopement ... 24

3.3.2 Jaari ... 25

3.3.3 Force marriage ... 25

3.3.4 Widow marriage ... 26

3.3.5 Divorce ... 26

3.3.6 Taboos ... 26

3.3.7 Pollution ... 27

3.4 Public places/community spaces ... 27

3.5 Language ... 29

3.6 Culture ... 30

3.6.1 Kinship and lineage ... 30

3.6.2 Lineage and clan ... 30

3.6.3 Fictive kinship/Miteri ... 31

3.6.4 Joking Relationship ... 31

3.7 Religion ... 32

3.7.1 Deities ... 32

3.8 Life circle and rituals ... 33

3.8.1 Birth rituals ... 33

3.8.2 Bratabandha ... 35

3.8.3 Marriage ... 35

3.8.4 Death ... 36

3.8.5 Festivals ... 39

List of Tables

Table 1: Demography and Location ... 4

Table 2: Household Amenities ... 15

Table 3: Economy and Resource ... 48

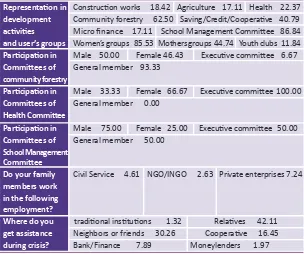

Table 4: Representation in development activities and user’s groups ... 53

Table 5: Education ... 55

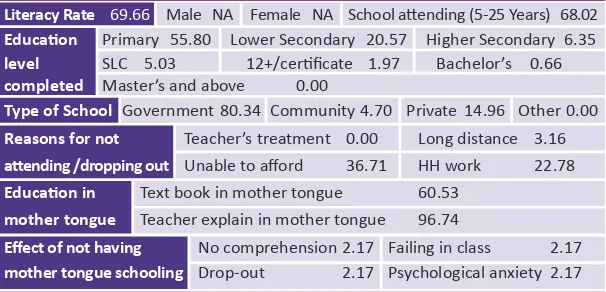

Table 6: Health ... 57

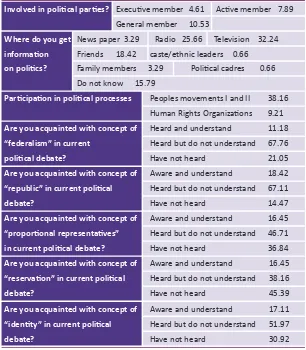

Table 7: Representation in Politics ... 62

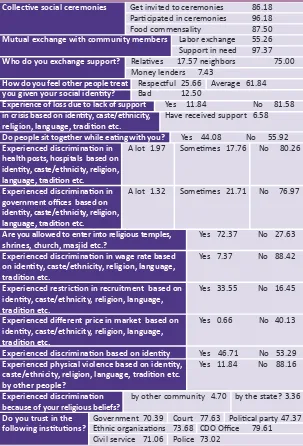

Table 8: Identity-based exclusion and discrimination ... 64

Table 9: Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality ... 68

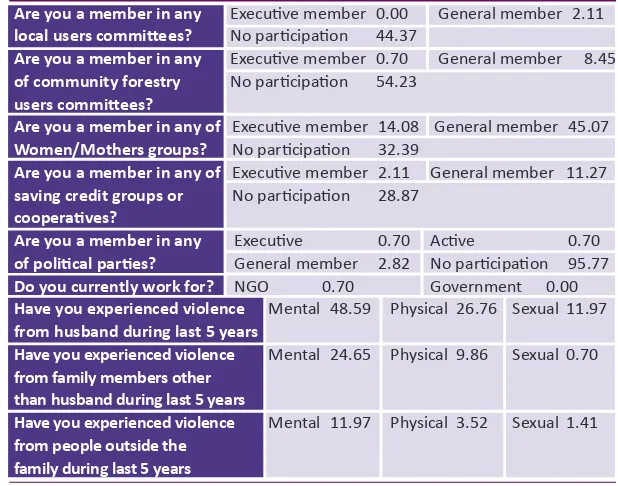

Table 10: Women’s Representation and violence against women ... 69

CHAPTER I

Introduction

vi 3.8.6 Costumes and ornaments ... 403.8.7 Domestic Tools/Technologies ... 40

Chapter IV: State of Human Development ... 43-57 4.1 State of Human Development ... 45

4.1.1 Prostitution ... 45

4.1.2 Nathuni kholne ... 46

4.1.3 Entertainment ... 47

4.2 Economy and resources ... 48

4.2.1 Agriculture ... 48

4.2.2 Land ... 49

4.2.3 Occupational skills ... 50

4.2.4 Inheritance ... 52

4.3 Representation ... 52

4.4 Tradition Institution ... 53

4.5 Representation Groups in study area ... 54

4.6 Education ... 54

4.7 Health ... 56

Chapter V: Current Issues of Exclusion and Inclusion ... 59-69 5.1 Political exclusion ... 61

5.2 Identity based exclusion and Caste-based discrimination 63 5.3 Intra-Dalit discrimination ... 67

1.1 Introduction

BADI is a caste of the Dalit community residing mostly in the mid-western hills of Nepal. hey were conceived to be the lowest of hill Dalits under the national civil code (Muluki Ain) of 1854. heir status in the code has not changed even today. Badis have been discriminated against by non-Dalits, and hill Dalits as well. heir discrimination occurs on the basis of caste, but they are also excluded in political, economic, educational, social, cultural activities and from employment opportunities in state and non-state sectors.

he Badi community represents 38,603 (0.145%) of national population of Nepal. he male population is approximately 18,298 and female is 20,305, with the population of female higher by 2,007 persons than the recorded male population (CBS: 2011). Badi settlements are dense in districts of the Mid-Western Region. In addition, they can be found in rural and urban areas of all ecological belts in all development regions, albeit in smaller numbers.

CHAPTER I

Introduction

3

Table 1: Demography and Location

More than 98 percent of Badis speak Nepali as a native language at home and in schools. Besides Nepali, they also speak a kind of code language (palsi). Most of the Badis (85.83%) follow Hinduism, while, 12.5 percent were found to believe in Christianity (see Table 1). he trend of conversion into Christianity is quite high among the Badis in comparison to other hill Dalit groups. hey are attracted to convert into Christianity because of its professed equality and non-discriminatory behavior, rather than religious understanding.

Discrimination is the primary reason for Badis conversion to Christianity. Badis interviewed for this proile say that it is better to belong to a religion in which there is no discrimination. A Badi youth says that the feeling that there is no discrimination in Christianity and all humans are treated equally, is growing in the community. He says that it gives dignity to people. Similarly, a converted Badi woman says Christianity teaches that children should be educated. She says that nowadays there is equal relation not only among Badi Christians, but also non-Badi people who have begun to behave respectfully toward them. “After we learned from the church, and after we changed our behavior and habits, others have changed their perspectives toward us.” It has also been observed that some people converted to Christianity due to superstition and disbelief, when they were told that praying to god would cure illness. Some have also converted after they learned about the principles of Christianity. In addition to Christianity, some women converted to Islam at the time of marriage.

5

4 2014 2014

CHAPTER I: Introduction CHAPTER I: Introduction

Demography Total 38,603 % of 0.145 Male 18,298 Female 20,305

and Locaion Populaion Populaion

Age Group < 5 Years 13.80 5-19 Years 40.33 20-59 Years 41.93 60+ Years 3.94

Marital status Unmarried 44.21 Married 47.26 Separated 1.22 Widow 4.57 Language Speak naive 98.68 Speak naive 98.68 % who can speak 92.77

language in family language in school naive language Speak naive language 97.37 Nepali Speaking proiciency 98.68 in govt. oice

Religion Hinduism 85.53 Chrisianity 12.50 Buddhism 0.00

Source: NSIS 2012

1.2 Methodology

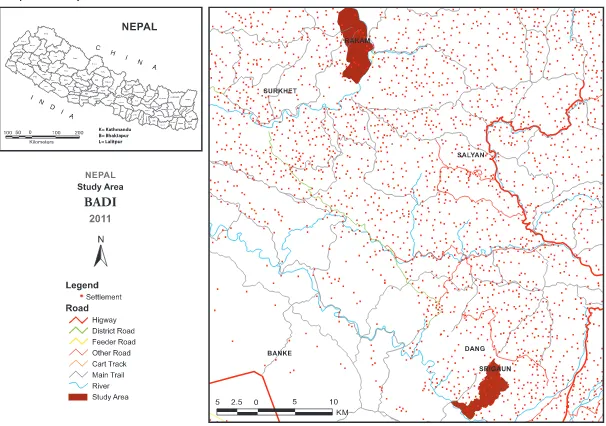

his study was conducted primarily at Rakam VDC of Surkhet District and Shrigaun VDC of Dang District. he research took place from September 10 to November 20 of 2012. Research methodologies implemented during the period included observation methods, group discussions, interviews, in-depth interviews, case study methods and collection of data. Altogether, out of the 25 total interviews, three in-depth interviews were taken from diferent persons and places on diferent topics. Out of 11 group discussions, three focused on Badi youths, women and aged people exclusively, eight mixed-group discussions were held in Rakam village of Surkhet district. Similarly, during the 26 days of study in Shrigaun, Dang District, out of 20 interviews, two key informant interviews, nine mixed group discussions, and ive expert opinion interviews were held.

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER II

Demography, Settlement,

Territory

9

2014

2.1 Settlements of Badis in Surkhet

here is a Badi settlement in Jamune Bazaar of Ward 6 and 2 of Rakam VDC. Badis themselves call it Jamune Bazaar. It is on a plateau made by the Bheri river, where Badis were the irst to settle. he place received its name because there was a Jamun tree (Indian black berry) on the plateau, and the irst settlement was made in the shade of the tree. Today it is a small bazaar, with villages in the east, west, and south and Bheri river in the north. he Badi settlement is surrounded by the settlements of other Dalits, hakuris, Bahun-Chhetris, and other groups. It is compact and clustered.

here is an interesting story about the naming of Rakam. Once, during Satya Yug, there was a great lood on the Bheri river (a tributary of the Ganges). he lood was causing damage in the upper areas. It was already dawn when the lood reached the lower area. Gangaji asked a rooster if she should wash the area away (falnu), the rooster requested Gangaji to keep (rakham) it. hus, the area got its name.

Today more people born outside Surkhet district live in Rakam. People from all walks of life come to live here.. A discussion with other merchants revealed that because this area accommodates people from everywhere, it got its name rakam (let’s keep).

10 2014

CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory

to the east or north of this area. As the village was at the top (shir), it was named Srigaon. According to another saying, there is a Siddha Baba temple at the top of the village he priest who worshiped there daily gave the name to the village. Badi settlements are also called Bagar because Badis live near the riverbank (bagar). Badi toles are named according to the original place from where the people have come, such as Falawangi tole (from Falawang); Salyani (from Salyan); Sangkoti (from Sangkot), etc. Such naming distinguishes people of a common place of origin, which helps to establish relationship at the time of marriage, death, and other occasions.

2.2 History of Settlement

Before the Christian era, during the reign of Bhure Takure (Magar) kings in far western Nepal, King Jiktisin ruled in Jajarkot district. He was regarded as a very powerful king. he vayupankhi winged horse, handmill, shot-put ball, and watermill used by him can still be seen in Bijeshwori in Rukum. he legend has it that he could throw a shot put from Jiktipur to Chaurjahari of Rukum. His horse used to go to Jajarkot to graze. When he traveled to Jajarkot, he liked the place and began to rule Jajarkot. hen he married a woman from Lucknow. When he went to his in-laws, he brought to Jajarkot some groups rode horses and entertained the king and the nobles. hese entertainers, who played music and danced (baadya baadan) later became Badi, according to Pustak Badi, a migrant from Jajarkot to Rakam. So, Jiktipur of Jajarkot is the origin of Badi, who were brought from India. When descendants of King Jiktisin recite stories and legends of King Jiktsin, they mention the Badis.

Badis are supposed to have come from Kumau Gadwal of Uttar Pradesh of India and, as reported by descendants of the petty kings of Salyan, initially settled in Salyan district of Nepal. he irst generation earned their living by entertaining others and making pottery, while the second generation adopted ishing as a secondary occupation. Stories and legends indicate that kings and nobles invited Badi girls of the third generation to serve as sex entertainers. Illegitimate children were born from the fourth generation. In the ifth generation, Badi women were kept as concubines. However, when keeping concubines began to interfere with social norms, petty kings, nobles, and oicials began to expel Badis from villages. After being displaced, they came to the streets and started begging by dancing, singing, and playing instruments (baadya). hey were later called Badis.

here are debates on the place of origin and identity of Badis. Some consider Salyan district as their original place, while Badis who migrated from Jajarkot to Surket report that they came from India to Bajhang and Jajarkot. Some regard Badis and Patars as part of indigenous traditions such as Deuki, Deuchel, Devdasi, Kumari, and Jhuma. A scholar of Badis in Dang argues that they came to Nepal from Vaishali in India with the Lichhavis. Lichhavis entered Nepal around the irst or second century of the Vikram era after conquest of Vaishali by the powerful Magadh state. At that time, prostitution was a socially acceptable and respected occupation in Magadh. Also, there were many women’s groups who entertained the king, royal oicials, and feudal lords with music, dance, and sexual services. hey would remain unmarried throughout their lives. Some of these women came to Nepal along with the Lichhavis. he present-day Badis are their descendents. Another argument states that along with Lichhavis, a large number of caste groups including the Badis, came to Nepal. Based on discussions with some educated Badis and a researcher of Badis in Dang, they belong to the Nat jati, and they entered western Nepal from Lucknow and the surrounding areas at the end of the Malla period. hey may have been brought from various Indian states by the Bhure hakure kings to entertain in their palaces.

Dalit activist Bishwabhakta Dulal Ahuti argues that Badis are not indigenes of Nepal but were brought here around 14th to 16th century from India. he Banjaras of India were a respected Hindu group who traveled to diferent places singing and dancing. It is argued that these Banjaras were brought to Nepal from India by the then Bhure hakure kings of Jajarkot, Rukum, and Salyan for their entertainment. During their reign, the Badi’s occupation of entertaining was respected and digniied. When King Bahadur Shah began to unify Nepal, the Bhure hakure petty states disappeared, and the occupation of Badis was in jeopardy. Because they were brought by kings and were not part of the traditional social structure, there was no balighare (jajmani) institution like that of other Dalits. After the kings left them, they came to the streets. hey earned their living by entertaining others by singing and dancing in the streets. Because they were entertainers, they were attractive. hat attractiveness later became helpful in their exploitation. Initially, the entertainment was respected because they used to welcome guests and entertain them at birth, marriage, and other life cycle rituals and festivals. his tradition spread from the king to the mukhiya, jimwal, ghadbudha, and pradhan level in the villages. When the women were sexually exploited, they adopted prostitution as an occupation. his shows that the Badis have the greatest mixed ancestry with Bahun,

11

2014

13

2014 Chhetri, hakuri, Janajati, Madhesi and other Dalit castes. Badis who migrated

from Salyan to Dang share this opinion. hey think that there are similarities between them and the Banjaras of India. Singing and dancing is the traditional occupation of Badis. Music players are called baadak and dances are called patra or patri in Sanskrit. Badi leaders assume that the current words Badi and Patar are corruptions of these words. Nowadays the word Patar means a prostitute, but in the past all Badi women were called Patar (prostitute).

2.3 History of Migration

According to a 40 year old Badi woman in Rakam VDC, ward no. 2, Surkhet, her ancestors came here from Jajarkot. She considers herself an ofspring of a Budhathoki man, who came here about seven generations ago. In Jajarkot, one of her forefathers married a Badi woman. At that time, if a man married a woman of low caste, his caste would be downgraded. As it was believed that if a person wanted to gain merit for the after life, they should expel such couples to the other side of the Kaligandaki River, the woman’s forefather and his wife were expelled and came to Rukum. Later adopted the culture, occupation, and lifestyle of the Badis. hey began to make maadal, and danced to entertain. hey also started ishing. he Badis came to Salyan in the process of begging from one village to the other. heir ancestors stayed for three generations in a place called Kafalpani. Here they learnt ishing and maadal making. hey survived by singing and dancing at rich people’s homes. When property was distributed, the woman’s grandfather got Rakam village. Because it was diicult to travel between Salyan and Rakam, her father migrated here. A major reason for migration of Badis is inter-caste marriage. Badis of Surkhet and Dang reported that many of their ancestors were expelled from their villages because of this. Finding ways of earning a living is another major reason for their migration.

Many Badis did not know the origin of their caste, history and ancestry, and their deities. Many reported that they were not told anything about these things. Badis of Dang had migrated mostly from Malta, Sangkot, and Bhaluwang of Salyan. Although it cannot be deinitely said from where the Badis of Rakam had migrated, it seems that they migrated from Jiktipur, Dhaiya, and Musikot of Jajarkot because they were driven away by villagers after high-caste men married them.

Badis of Dang consider Salyan their ancestral home and India (Vaishali, Lucknow, Gadwal) as their place of origin, but Badis of Surkhet consider India as their place of origin. hey do not consider Salyan as ancestral territory. Badis used to live six months in the hills and six months in the Terai, when some migrated due to fear of elites. = hey called the place they settled in the “new territory.” Badis are known and named by others according to their place of origin. For example, a man who migrates from Kafalpani will be known to others as Kafal Pani dai, one who has migrated from Dhaiya in Jajarkot as Dhaiyal, and one who has migrated from Gharigaon of Rukum as Gharigaunle. heir settlements (toles) are also named according to their place of origin. Most Badis consider their place of origin in Nepal as Salyan and Musikot. According to a Badi scholar, who has been studying them, they are indigenous people and are descendants of angels of heaven.

2.4 House Types of Badi

he houses of Badis in Jamune Bazaar are organized in a cluster. A Badi man says that the clustered pattern is needed for deepening social relationships. At times of sorrow or joy, at marriage or death, Badis need the company of their relatives. Badis were migratory in the past, and because they needed to settle by

CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory

12 2014

15

2014

14 2014

CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory

building huts or camping, they needed to be together. Another reason is that, others do not allow Badis to settle near them because of fear of their children getting spoilt. hey also fear that the Badis will steal their fruits and vegetables. So Badis live near river or in caves together. In both Surkhet and Dang districts, Badi houses face east. Badis consider east as an auspicious direction, while the west is considered the direction where funeral proceeds, the north is where the demon opens his mouth. hey may, however, place the front door facing south.

2.5 Household Amenities

Badis are a very poor community. Most houses are made of stone and mud, with the roofs also made of mud. Some houses have tin roof or are roofed with concrete, and some are thatched. A well-to-do Badi builds a big two-story rectangular house of brick and concrete. Most Badi houses are small and square in shape. he height of the house is usually low. he height seems to depend on the number of family members and the economic condition. Due to migration, Badis make houses often. An old Badi man who is fed-up with building houses, says he has lived in various places from caves to huts. He has seen his hut with thatched roof burned to ashes. He has also made a house of stones and mud. He had roofed his house with tin plate, but last year the storm blew it away, and now he has roofed it with slate.

Inside, the house is smeared and plastered with cow dung and mud. he walls are plastered with mud. here is no decoration whatsoever inside the house,

Household items of Badi.

whether the person is rich or poor. But on the day of Nag Puja, they paste a picture of a snake above the front door.

However small a house may be, it is usually two-storied. Usually, there are four rooms. One is a kitchen, one is a bedroom for the senior couple, one is room for the son, and one is a cow shed for cattle. here is no distinction between a kitchen and a bedroom. Only a few utensils are seen in the square kitchen, and there is not enough room for even two people to sit to eat.

hey have no blankets or beds in the bedrooms, which are very small. Most sleep on the loor. Sons get to sleep in a separate room. However, when guests come, the son moves to his friend’s house to make room for them. he small size of the house is due to lack of land.

In some houses, Badis have placed religious lags and wooden idols in the eastern corner of the kitchen. Other houses do not have a shrine or altar.. Because Badis were migratory, there dwellings did not have a room for worship. Even if they don’t workshop on a regular basis they believe in gods and goddesses. Badis do not plant the tulsi tree because they were not allowed to touch it. Nowadays as Badis have begun to settle permanently, they build a separate worship room in their houses. Badi women who are married to high caste men worship tulsi but they do not seem to have planted it.

Table 2: Household Amenities

Ownership of house Self-owned 3.95 No. of rooms used 3.94

Rooing Cardboard/ 4.61 Cement 1.32 Tin/ 56.58 Tile/ 15.79 Thatched/ 21.71

materialsPlasic Zinc Slate grass

Cooking Electricity 0.00 LP Gas 0.66 Kerosene 0.00 Firewood 98.03 Straw/ 1.32

fuel grass etc.

Source of Lighing Electricity 32.89 Solar 21.05 Kerosene 19.08

Batery lamp 20.39 Diyalo 6.58 Others 0.00

Household Assets TV 24.34 Landline Telephone 0.00 Mobile Telephone 73.68

Motorbike 2.63 Car/bus/tractor/truck 0.00 Cycle 17.76 Computer 1.32 Rickshaw/Tanga 0.66

Animal ownership Cow/Ox/Oxen/Calf 12269 Bufalos 35778 Pigs 7173 and approximate Chicken/Ducks 1818 Yak 0.00 Goats 10471 Horse 50000 values (Rs.)

16 2014

CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory

CHAPTER III

History, Society and

Culture

19

2014

CHAPTER II: Demography, Settlement, Territory

3.1 History and Myth of the Origination of Badi

Badis are also considered the ofsprings of Upadhyaya Brahmins. In Indralok, the realm of Indra, there was always entertainment and feasts. Only Upadhyaya Brahmins could be cooks in heaven. Once Indra organized a feast for the gods. An Upadhyaya Brahmin was charged with preparing the feast. Angels were entertaining the gods by dancing and singing. he Brahmin cook intently watched the performance through a hole in the kitchen. He was obsessed with the dance.

When Indra invited his guests for the meal, the Brahmin realized that overheating had spoiled the food. He sank at the feet of Indra and confessed that he had been so focused on the performance that he did not know the food was spoilt. Indra asked him whether he liked watching dances. he Brahmin replied that he enjoyed watching the angels’ sing, play music, and dance from childhood. Indra cursed him than and said: “from now on, you go to Earth. May your head not get any dirt, and may your feet not get any mud. May your hands never reap pepper, and may you get whatever you beg for. You will live by entertaining humans by playing music and dancing. You will also make your women, such as daughter, wife, and daughter-in-law, sing and dance.” Cursing thus, he sent the Brahmin to earth. from that time onwards, he and his family began to earn their living by singing and dancing and begging, as Badis do now. So, this proves that they are the descendents of the Upadhyaya Brahmin.

CHAPTER III

21

2014

20 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

here is another story about the origin of Badis and the word “Badi.” According to the story, Badis are descendents of a isherman. In Satya Yuga, when all animals and plants could speak, a man would ish in the Ganges every day. One day a ish complained to God that a man had been catching and killing the ish for no reason. God summoned the man and the ish, along with some other humans and asked the man his reasons for killing the ish. he man responded that there had been a abundance of ish, due to which the river was becoming polluted. Because he depended on the river for drinking water, he was merely trying to decrease the number of ish, he was not trying to eradicate them. He added that if the ish would urinate and defecate somewhere else outside the water, then the water would not be dirty, humans would be healthy, and there would be no need for him to catch them. God considered the man to be a killer (badhak) of ish and cursed him that from now on he would live by ishing. All the people started calling the man a badhak (killer). hus, the word Badi originated from this word badhak.

here is yet another legend about the origin of Badis. It suggests that division of labor based on caste was ordained by God.. One day, God decided to divide the work and invited humans from all the nine villages that inhabited the planet. he king asked each human to choose a piece of work. A woman said that she would like to worship and serve the gods by staying near the temple or shrine, and she became a Brahmin. Similarly, another woman wished that she would serve humans by digging the earth, and she became a Chhetrini. People of each village chose a particular work, but no one chose to entertain in the god’s palace. So, the gods were worried.

Next day, God went hunting. He saw his daughter Sita dancing in the jungle while another daughter, Parvati was singing. He assigned dancing to Sita and singing to Parvati. From that day on, God set Sita inside and Parvati outside. he two daughters accepted the order of their father, and he blessed them thus: they would never be hungry but never have enough to store, they would never be bewitched, that no one could accuse them even if they stole others’ vegetables and fruits, they could not eat inside another’s house, that they would turn a non-giver to a giver, and that they would accept things even with spit on it and wipe it. After many generations, the word Parvati was corrupted and became Patar (prostitute). After Parvati had become an entertainer, her father searched for a man to marry her. He wanted the man to have some special skills: he should not only be able to make a maadal (a kind of drum) but also be able to make sounds with the maadal so that Parvati could sing and dance in tune

with it. In order to marry Parvati, many men began to make maadal of diferent kinds of wood but did not succeed. Finally, a man made a maadal of khira wood, but it did not produce any sound even after many attempts at striking it. Frustrated, he threw the drum of the clif. When the drum was rolling, he heard it make a sound like chaamal-challi. He brought the drum back. After he worshipped it with rice (chamal) and chicken (challa), the drum began to beat. he man married Parvati, and their ofspring became Badi and Patar.

3.2 Society

3.2.1 Family

Badis live in nuclear families. Joint family has never been the preferred family organization. A Badi woman of Rakam says a son will separate from his parents some months after marriage. Because they needed to beg for food, they would need to feed more mouths in a joint family. Another reason for the nuclear family is because Badis are considered to be a community who eat good food and wear good clothes. According to a Badi man of Rakam, in a joint family one cannot eat good food because one needs to share it with all other members. His parents would go for work, and when they brought the food they would eat themselves without sharing with others. here is no dispute or quarrel between sons about inheritance because they do not have any property. he father would divide the villages in which he begged, and the sons would beg in these villages and earn their living.

23

2014

22 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

3.2.2 Family structure

Compared to other groups, Badi women have greater role and responsibility in the family. Badis were initially matriarchal, and so the role of mother was paramount in the family. he gender relation can be analyzed in diferent historical periods. Initially, when they went to the petty kings and the rich, the whole family was under the control of the male or father, and he was the head. he male decided on everything and had exclusive power. he second phase is that of migration, when Badis would travel from one place to another entertaining people, and they had no ixed settlement or house. hey lived in the Terai for six months and in the hills for another six months, begging from one village to another. During this phase, Badi women gave importance to the occupation of prostitution, and took the power and responsibility of decision making and running the household. According to Badis who were interviewed, in Badi communities the role of the mother is paramount in families which practice prostitution. Even now, in a household in which Badi women are involved in prostitution more rights are held by women than men.

At present, there is hegemony of the male. here is hierarchy in the family with the grandfather or father as the household head. he household head takes his meal in a big plate. here is a ritual of eating kalyulo, in which the father gets the head of the fowl while the mother gets the tail. When discussing the

gender-based explanation of this ritual, some admitted that it signiied the inferior status of women. Others, however, explained that it was not oppression, but a token of love. When a mother distributes food to the family she may have nothing left for herself. In that case, the tail given to her by her husband becomes a token of love.

he role and responsibility of the mother is greater than other members. he status of eldest daughter and eldest son is equal because daughters are more important than sons. According to an old Badi at Rakam, a mother generally begs to earn a living. Later when the daughter is young enough, she can start earning, so there is a greater role for women in the family.

he role of husband and wife is equal in the work outside the house, so they are mostly seen together. Whenever any work outside the house is initiated, the wife takes the lead, but she does not start it without irst consulting her husband. Badi women help their husbands. If men do not beg, the women’s group goes and brings grains, which supports their living. At present, however, in most households men are more powerful and have greater rights.

Power relationship between men and women can be observed in two ways. In households with a long tradition of prostitution, women have more power and men have little value. Women are responsible for household activities such as cooking, raising children, grinding the kit to make maadal, and weaving the ish net. he household is run by the earnings of women. here is greater responsibility of the mother, including welcoming the customer, involving daughters in prostitution, and managing the household with these earnings. he daughter may buy anything she needs without consulting her parents, and she can use the money or property in any way she likes.

3.3 Marriage

25

2014

24 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

In the irst phase, Badis married within their own community. But when they became migratory, , they did not give away their daughters in marriage, but rather made her a prostitute. hen Badi men began to marry women of other groups. his is the reason for celebrating the birth of a daughter, because a family with many daughters will have enough to eat without much hardship. However, it is common that only if there is no MBD will a Badi man ind another girl to marry.

Child marriage has been practiced by Badi from ancient times. When Badi girls went to kings, mukhiya, and the rich and powerful, they were sexually exploited. Later, when they were migratory and begged from village to village, they again were sexually exploited, and some married. In that phase, the mother would ind a rich man to have her daughter delowered when she began her menses, in a process called nathuni kholnu (opening a nose ring), so they were sexually exploited from an early age. Badis are still practicing this tradition. A Badi man in Rakam says that girls are given away in marriage at 14 or 15 because they cannot aford to send them to school and because they fear that girls will adopt the occupation of prostitution. his is relected in the perception that men aged 20 are considered old.

here are rare cases when men of another caste have married Badi women and lived happily. his is mostly observed among men of Indian origin. hey are kept mostly as concubines. Some Badi men had inter-caste marriage, usually elopements.

Badi women are kept for six months to one year by males from other castes for sexual pleasure. None of the Badi women have been wives. . A Badi activist of Dang says there are many such women, but they cannot be named. Once in Rakam VDC, a Badi political activist went with an elder to another non-Badi political activist’s home to propose her daughter for marriage, but they were ridiculed and shamed. hat is why it is felt there is little chance of standard/ arranged marriage between Badis and non-Badis.

3.3.1 Elopement

If a marriage is arranged within one’s community, then there is standard marriage. But if it is an inter-caste marriage, then there is elopement. But now elopements are also taking place within the Badi community. Badi girls are excluded from education due to illiteracy and poverty. here are no educated

persons in Badi in Rakam VDC apart from two who have passed SLC. Many children of school-going age have been found to have gone for labor work because it is diicult for them to survive if they do not work. hey added that the parents would come home from work having spent more than they had earned. Parents do not give away daughters in marriage because children are considered breadwinners, so girls and boys elope. hat is why elopement is increasing among the Badis.

3.3.2 Jaari

Jaari is prevalent in Badi. In the past, because there was no law, a husband had the right to kill his wife if she eloped with another man. his was called jaar sadhne. Although there was jaar system, there was no jaar sadhne. he rivalry may be within the tole (locality) or between toles. he mediation of a jaar case is similar to that in other communities.

In the past, there used to be a chaukidaar (guard) in the village. He would be sent to the adulterer and would contact the chief of the village. hen, they would set a date for both sides to meet. he cuckold would demand an amount greater than that spent on their marriage, but there would be negotiations on the price and resolution of the dispute. According to a senior Badi of Rakam, there is no diference between jaari of the past and that of the present except that there is no rivalry or jaari sadhne. As far as possible, the matter is resolved within the community itself, if not, respectable persons are called for arbitration. Legal complaint is iled as a last resort. About a month ago in Rakam, a 50-year-old Badi woman eloped with a man of another village of Surkhet district. he cuckold tried to resolve it within his own community, but he failed, even after mediation by respected persons of the village. hen he iled a complaint at the police. Badis, both husband and wife, are suspicious of one another. A Badi woman can never roam in the bazaar alone. It is explained that this is why there is a prevalence of the jaari tradition. Nowadays as many Badi men work abroad, this tradition has been spreading.

3.3.3 Force Marriage

27

2014

26 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

3.3.4 Widow marriage

When a man is widowed, after performing the funeral rites of his wife for 15 days, he goes to his in-laws. he in-laws receive him with rituals. If he is of marriageable age, he can marry from the day he is welcomed there. His irst choice will be his deceased wife’s sister (sali), and the in-laws are also generally willing to give the daughter away in marriage. If there is no sali, then he may marry another woman.

Similarly, a widow should observe mourning for either 35 days or 6 months by wearing white clothes. After the end of the mourning period (barkhi), she may wear anything except sindoor. A widow may “stay in dharma,” that is, may not remarry for life. A widow observes barkhi for six months and wears white clothes for life. But she may remarry and then wear red or other clothes.

3.3.5 Divorce

he divorce process now is somewhat diferent from what it used to be in the past. In the past, if a husband and wife wanted to separate, they would call their parents or closest relatives, along with 12 respectable persons in the village from the Badi community. he husband and wife would be asked if they deinitely wanted the divorce. If they agreed, the maji of the village would declare that they were no longer husband and wife by striking red berries 12 times with a stick. hey warn the couple that whoever does not obey the decision the 12 Badis would go to hell (sat jani). hen, they would make the divorce paper. Until now, there is a tradition of conducting a divorce by gathering people of the community. If there are complex problems, they go to court.

3.3.6 Taboos

here are many taboos and restrictions in Badi culture. For example, one should not stand at the door because the door is a place of worship, and witches chant their mantra standing on the door. Similarly, if a black cat crosses the road when one sets out for a long journey, one should proceed only after backing three steps or after someone else has walked on the road. Also, on such occasion others should not ask him where he is going and should stay away from him. It is believed that the black cat is a witch in disguise, and it would caste bad spell over the journey so that the purpose would remain unfulilled. Also, a son should not shave his mustache when his parents are alive. Only after a parent dies should he shave, and then he should shave all the hair from the body. One should not sneeze in an auspicious moment. When winnowing rice or grains, one should not sit nearby, it may cause blindness.

3.3.7 Pollution

he tradition of not accepting water from Badis is still prevalent. he prohibitions surrounding menses is not as rigid as before, according to a Badi woman. In the past when a woman had menses, she would be isolated in a dark room for three days and was not allowed to bathe. But this is not so nowadays. She is not allowed to enter the kitchen and not allowed to touch anyone. She is provided a separate kitchen and a room. Touching of food or water by a menstruating woman is considered inauspicious, and members of the family may become possessed. Similarly, if a person dies, his ofspring should not touch the water of another house.

3.4 Public Places/Community Spaces

Chautara (tree shade platform) is an important public place where people take rest and meet and talk on various issues. Although Badis participate considerably in such discussions, they do not come to the fore for discussion, and their role is mostly that of audience. Many political programs and settlements of disputes are decided at the chautara. he chautara is in the shade of a ig tree that is paved with stones. he villagers themselves made the chautara, and Badis had carried stones for it. hey did not feel the need to make a chautara of their own.

Tea shops are another public place where people of diferent groups meet, and there are discussions on various issues. It is also a very sensitive space because it is where caste discrimination is practiced. Nowadays, there is indirect discrimination by some high caste people such as Bahuns and Chhetris. For example, a high-caste person takes his tea but may sit away from the Badi. In the past, Badis were not served tea in teashops. Later, they were served but needed to wash the tea glasses themselves. Now they do not need to wash the glass, but high castes would not drink from the glass that had been washed after a Badi had drank from it.

29

2014

28 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

tea. his trend occurs even while Badis are discriminated by other shop owners. During a general discussion with some shopkeepers in Jamune Bazaar, it was found that Badis were discriminated and exploited when purchasing food and drinks. For example, one shopkeeper said that while others paid Rs. 10, Badis paid only Rs. 5 for a glass of tea, so they were served very thin, watery tea while others were served special tea. Similarly, Badis were served stale food, such as chowmein and gram.

It seems if a Badi runs a tea shop or a pub, the other Badis would not go there. his shows that the relationship amongst Badis is not good. When there was a ight between some Badi and Damai youth regarding a simple issue and the Damai youth beat the Badi youth, the Badis could not unite. When the issue was discussed at home, Badis said it was better to refrain from provoking other castes as they themselves belonged to a low caste. his shows that Badis are oppressed but desire to live harmoniously with others.

Before there were public taps in the area, all villagers drank water from the Bheri river. But if a high-caste person was fetching water from the river, no one was allowed to fetch water from the upper section of the river. Badis were not even allowed to touch the river. Nowadays, there are taps in every tole, and Badis in the Badi tole use a public tap located there. When Badis need to fetch water from taps located in other settlements, they have to wait until all others have inished. A Badi woman reported that once a Badi child was beaten for drinking from a public tap. he villagers irst denied that the child was beaten, but when pressed on the reason for beating, they said it was not because the child had touched the pot but because the child had made the pot dirty.

In temples, some people are allowed to enter and worship with dignity while others are kept outside and not allowed even to touch the bell. he Durga Bhagwati temple in the village is open only during the Dashain festival, and Badis are not allowed inside until now. In the past, Badis were not allowed inside the temple compound. One group of Badi replied that they were not allowed inside because they were Badis, while another group replied that no one except the priest is allowed inside to worship. he priest said that he takes the oferings of all people to the temple but no one is allowed inside. However, Badis insist that people from other communities go inside and that only they are excluded.

Badis do not yet have equal access to public places. hey remain as audience in discussions in the chautara, but there is no discrimination when Badis are at the chautara. However, discrimination has not been completely eliminated at tea shops. When asked why they had not protested against discrimination and oppression, they replied that the site of discrimination was a village bazaar and they needed each other, so there was no point in ighting.

3.5 Language

Khas Nepali language is the mother tongue of Badis and they speak Nepali at home with family members as well as in the community. Badis have developed a special language called Khamsi or Palsi, which is spoken among them to cope with various problems encountered when begging from house to house. But the new generation does not know the language, nor is it spoken inside the house. When a person of another community comes to the house, Badis used to talk among family members in this language so that others would not understand what they were saying. his language is still spoken in large Badi settlements, and Badi elders often use it.

31

2014

30 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

3.6 Culture

3.6.1 Kinship and Lineage

Badis have ainal, consanguineal, and ictive kinship relations similar to those of other ethnic and caste groups in Nepal. However, they have closer ainal relationships compared to other relations. Badis say that they like the gunyu (a sarong-like garment) relationship, or ainal relationships more. his is more so among Terai Badis because they give more importance to daughters compared to sons. Hill Badis give more importance to consanguineal relations.

Badis consider son-in-law and nephew/niece as special relations. hey respect son-in-laws as Brahmins (priests). he son-in-law or nephew is essential in marriage, death, bratabandha, or birth rites, etc., to serve as a priest. Other relatives are not essential in any rituals or festivals. hey do not respect close relatives. According to an experienced Badi man of Rakam, they did do not have family planning. As they marry at a young age, the age of nephew and uncle is similar. hat is why they do not show any respect while addressing them. his seems to have developed as a tradition. A Badi activist says that when children grow up they begin to use disrespectful words to address their parents, yet lovingly. However, there has been some change in use of such addresses. Now they use honoriic language when conversing with parents and seniors.

3.6.2 Lineage and clan

Badis have no gotra, or clan. Most Badi were unaware of gotra. A local Pandit (priest) of Rakam VDC also denied knowledge of it. He explained that Kashyap is the gotra of grass, leaves, animals, and all those who do not have gotra. his may not be true. Badis initially were caretakers in palaces of petty kings, and later Badi women were made concubines. Children of Badis were not given gotra. Due to continuation of such occupation, Badis are not a progeny of a ixed ancestor or a clan. So, Badis have the most mixed ancestry. Group discussion with Badis revealed that because a child gets his or her gotra from the father, and because children were not accepted as their own lineage by men, they do not have any gotra. Not a single gotra or lineage name was found among the Badis in the study areas. However, they use surnames. Such surnames do not afect establishing marriage or other relations with other Badis. here is diference between surname and lineage. Some are descendents of Sunar, Giri, Budhathoki, Rolpani Bahun, Salyani, Sankoti, Falabagi, Musikoti, and Jajarkoti, while Patar, Badi, Nepali, Rana, Bhand, Damai, Baigar, Singh, Kumal, Das, Vadyakar, and Gaine are some of the surnames.

3.6.3 Fictive kinship/

Miteri:

In the past, Badis were eager to make ictive relationships with elites, but because high castes would not readily accept such relations, they were compelled to have it with other Badis who were not relatives. Panche Badi of Rakam VDC says that nowadays they build such relationships with other communities. hey regard ictive friendship or mit as one’s own brother, to the extent that the mit should observe the death pollution similar to that by family members. he mit’s son can even perform the funeral rights of his mit father. Bhagauti Badi thinks that such rites may have been sanctioned by the petty kings and the nobles because Badis have close ties with them. According to her, the kings and nobles were respected by having such mit, so Badis also imitated it. Such relationships are diferent among Badis in comparison to others in two ways. he irst is, such ictive relationship is established by organizing a feast, where the two men would hold each end of a small stick together and vow that they are now mit and one can perform the funeral rites of another’s parents in another’s absence, and that from now on they are family members. Another informal friendship occurs between namesakes by declaring that they are now friends. However, such a friend is not seen as a member of the family.

3.6.4 Joking relationship

Joking relationships are mainly between sala-sali, solta-soltini, and phupa-bhadai. Similarly, in some places there is joking relation between ego and brother’s wife. here is a saying: “No need to seduce your sali.” During Holi, brother’s wife (bhauju) and husband’s brother (dewar) play Holi by embracing each other. According to Horilal Badi, this is mainly so by Badis living near haru settlements. First of all, bhauju and dewar smear color to one another. his tradition is found mainly among harus.

33

2014

32 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

3.7 Religion

Historically, Badis are Hindus. It is said that Badis are descendents of Hindu gods. Because they live among Hindus and because the kings and nobles for whom they work as caretakers or entertainers are Hindus, a Badi youth says it is obvious that they became Hindus. When Badi were migratory and when they used to perform street music and dances, they used to perform Hindu texts such as Gita, Mahabharat, and Ramayan. For the last few years, there has been a trend of religious conversion, and many have converted to Christianity.

3.7.1 Deities

Badis worship deities worshipped by other communities. hey worship mainly Krishna, Ram, Vishnu, and Shankar, and also local gods such as Bageswari, Deuti Bajai, and Bijeswori. Goddesses include Durga, Laxmi, Saraswati, and Kali. Some evil spirits are Varma, Masta, Bhaiyar, and Rote, Chokhalo, Jaldhanna (who takes sato), Varaha, Gailo, Hes, and Lato. Rote is the main devil. When a Badi woman delivers a baby, irst of all, the Rote devil should be propitiated. here are diferent ways of worship for diferent gods and devils. Some are ofered fowl while others are ofered goat, sheep, or even pig.

If someone is bedeviled with a chokhalo, the following items are required to propitiate it: goat, and lags of green, yellow, white, black, and red colors. he priest worships an area smeared with cow dung by marking with turmeric powder. Pregnant or menstruating women should not go near the site of worship and should not take the prasad because they are polluted by chokhalo. Only after propitiating chokhalo is the jagge worshipped by sacriicing a fowl. his puja can be done by anyone.

In the past, people sufered much from evil beings. If a person throws his sweat in the Raira of Salyan, he would be bedeviled by the arma devil. he devil would not kill a person immediately, but would kill him by torture. he possessed would show many types of diseases, and inally he would die. According to Ravi Badi, a shaman/dhami of Badi, baby goat, lags, kayo, etc., are needed to propitiate the devil. When worshiping chokhalo, a clean area is needed, usually far from home in a jungle or riverbank. he worshipped items should not be carried home. After worshipping they eat there and they give the remaining food to passing pedestrians. If anything remains, they should dig a hole and bury the leftovers in it.

When Badis migrated, they adopted the deity of their place of destination and worshipped them rather than deities of their place of initial settlement. Lilbhan Badi of Rakam reports that he did not know his ancestral deity when he lived in Jajarkot, but after he migrated to Rukum his family began to worship Kaljaishi Varma as their ancestral deity. When they moved to Salyan, they began to worship another deity, Khukure Varma. Finally, when they came to Rakam, they began to worship Kalika Devi. According to a study of some Badi families, they worshipped their forefathers as deities.

Badis worship the main pillar (mainkhamo) of the house as their ancestral deity. If the ancestral deity is far away and they cannot go to worship even once a year, then they worship the pillar as the deity. Badis erect the pillar when building the house. When someone leaves home, he or she informs his or her elder. If there is no elder in the house, he or she greets (dhog) the pillar as it is considered auspicious.

here are not many objects for worshipping. For ancestor worship, they need fruits, ash gourd, papaya, one mana of rice, lags, and saku. All family members should be present for this workship.

3.8 Life Circle and Rituals

3.8.1 Birth rituals

When a woman inds herself pregnant, she informs her husband. In other communities, when a woman gets pregnant, she and others wish that it be a son. But it is diferent among Badis. hey wish and pray that it be a daughter rather than a son because daughter is the breadwinner in Badi families. But not all Badis think like this. Baburam Badi thinks that such wishes began only after they involved their daughters in the dancing and prostitution occupation. An old Badi man says: “Oh Saili, your house has four daughters; now your days have come.” Like in other communities, pregnant women are given nutritious foods and rest.

35

2014

34 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

When all arrive, the ceremony begins. Usually, children are delivered at home. If a woman gives birth at her natal home, she needs to be puriied. On the day of removing the pollution, the natal home also should be puriied. It is believed that blood should be shown on that day, so they sacriice a fowl or goat. he Bahun puriies the house by sprinkling water dipped in gold (sunpani), sesame, barley, and an earthen lamp. hen he puts turmeric powder and lour and makes a yellow line on the jagge (altar). he animal is sacriiced and it is rotated around the jagge. On the ire of the jagge, the newborn is lifted according to the number of days of the child’s age. After the Bahun shouts that the pollution went away, it is considered gone. After the ceremony, the mother is sprinkled with sunpani and she is allowed in. Until the baby is christened, the mother and the child are kept in a room, and she should not touch anything in the house. Villagers also do not allow the mother to touch any sacred things. he naming ceremony is a little diferent from other communities. Nowadays the name is chosen by the family when they organize a feast and jagge. But in the past, the baby was named according to the month, day, and place of birth. For example, a child born on Sunday may have the name Aaite (aitabar=Sunday), born at karasa is called Karasi, born in the month of Ashad is Asare.

According to Lilbhan Badi, there was no tradition of Chhaithi. hey copied this tradition from the house of the king or nobles when they went to entertain at Chhathi. Badis dance the whole night and entertain to please the Bhabi (fate goddess) so that she may write good destiny for them during Chhathi. Nowadays there is a ritual of keeping a book under the mattress of the baby, wishing that the baby becomes a learned person.

In the past, because they needed to beg food from one village to another, they did not celebrate the rice feeding ceremony of the baby. But they have now begun to adopt this ritual. hey fed the baby jaulo at six months for a baby boy and at ive months for a baby girl. However nowadays, some have begun organizing a small feast.

here are ixed rules for the baby’s shaving ceremony. When a baby reaches nine months, the maternal uncle shaves the baby’s head. he uncle has an important role during this ceremony. He is fed good food and is given a set of clothes, and the uncle also gives the baby a new set of clothes. he hair is collected in a leaf-plate (tapari) so that it does not fall on the ground. Along with a lamp, the hair in the leaf-plate is carried away in the river. It is believed that if the hair reaches the sea, the child will live a long life.

3.8.2 Bratabandha

Badis do not have the ritual of bratabandha and chaurasi. It is said this is so because all rituals of bratabandha ceremony are done by the Brahmin, and because Brahmins do not come to Badi’s house due to untouchability, they do not observe such rituals. Badis also do not wear the sacred thread (janai).

3.8.3 Marriage

When a girl is born to a brother, there is a ritual where the sister ties a thread symbolizing the baby as the future daughter-in-law. But this ritual is gradually disappearing. For arranged marriages, Badis send their close relatives to the girl’s house to disclose the intention of marriage. If the girl’s parents are positive about the marriage, the boy’s parents and the boy go to the girl’s house and see her. To solidify the deal, they do pahelo tika rato achano, which means to give yellow tika and to sacriice an animal. Whereas in the past a wedding took only a few days to occur, nowadays the girl’s parents set 1-1/2 years as the deadline for wedding.

After 1-1/2 years, mangni (betrothal) is performed. In the betrothal, according to the wishes of the girl’s side, the boy’s side needs to take a bufalo, khasi (castrated he-goat), pig, and kasar (ball made of sugar and rice lour) to the girl’s house. According to the demand from the girl’s side, a decision is made on the amount of char (money paid by the boy’s side to the girl’s side) and the number of members in the wedding procession (janti). A relative serves as the priest for the wedding. hen a procession (janta) from the boy’s side goes to the girl’s house. When they reach near the girl’s house, two bhatkawa run ahead carrying dudhelo to inform how many are coming in the procession and what they would eat. Only when the girl’s side invites them would the procession go inside the girl’s house. Nowadays Damai musicians from the girl’s side welcome the procession, but in the past Badis were not allowed to play music at their weddings. he girl’s father and some girls welcome the procession. he members of the procession should give them money as gift. hen they begin to eat and drink.

37

2014

36 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

Typically, the groom’s sister or someone younger than the couple will obstruct the main door. he couple is allowed to go inside only when the bride gives some money. his ritual is called dhoka chhekai (blocking the entrance). heir own relative serving as the priest fulills the inal wedding ceremonies on a Wednesday or hursday. On the inal day of the wedding, the groom puts the sindoor, carried in a banana leaf, on the bride’s hair. In this way the wedding ceremonies conclude.

3.8.4 Death

here is a tradition of employing a dhami-jhankri (shaman) for treatment when a person falls ill,. If there is no shaman, the ill person is taken to the hospital. When the person has diiculty breathing and is near the end of life (ghiro manero), they are fed yogurt, milk, or water. his feeding is called hiran. It is believed that the death would be peaceful because the dying is remembering their relatives. he dying person is said to be having hiran with the person who feeds them last before death. hen the dead body is taken outside of the house and into the yard. If the dead had his knees lexed, then knife, dagger, or khukuri is placed on the top and bottom of the body so that the dead body would not elongate. Two ingers are bound with a thread, and two toes are also bound. On the chest, a green leaf-plate is placed with one mana of rice in it as saamal (daily food). A pitambar (yellow religious cloth) covers the body. At least two meters of wat is used according to the economic condition. he bier should be carried only by the sons. If the deceased has no sons, then close relatives carry the bier. here is a tradition of throwing parched paddy along the way to the cemetery. his is done by the Bahun or the son-in-law. In the past, Badis were not allowed to play shankha (conch-shell) or music in funerals. According to Pustak Badi, this was because the kings and nobles said that they would have no place in heaven if they played music and the music instruments themselves would be polluted.

Similarly, he reports that once Badis were beaten in Jakarkot when they played music during a funeral. Nowadays they play shankha and music. he dead body is carried to the ghat. In the ghat, half of the leg is submerged in water. In the ritual of matti dine (giving of soil), the eldest son ofers soil to the dead, and then others do the same. hen a funeral pyre is made, and the sons carrying the dead on their shoulders should go around the pyre three times instead of the usual seven times. All ties on the body are opened, and the eldest or the youngest son lights the pyre (dagbatti). Other sons are not considered appropriate to perform this task.

When it was discussed why other sons are not eligible for lighting the pyre of

their parents, many explanations were ofered. Among them, two folk stories are important. According to the irst story, once upon a time a country came under attack by its enemies and there was a great battle. Most of the young people either led or died in the battle. Afterward there was a decrease in the number of soldiers, and the king decreed that every family should send a young man to join the army. he king went to a house and asked the old man in the house to send one of his three sons to join the army. he old man could not reject the king’s request. He thought that the eldest son was needed for his funeral rites and the youngest was still very young, so he decided to send the second eldest son. he father then approached the son and sent him to join the army, saying: “You may die before I do, and you may not see my dead body. So, from now on, for me it is as if you were dead, and you don’t have to perform my funeral rights.” From that time onwards the second son is not required to perform the funeral rights of his parents.

39

2014

38 2014

CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture CHAPTER III: History, Society and Culture

After the couple discussed between themselves, they decided to send the second eldest son. hus, this middle son is called one who has been sacriiced. hat is why the second eldest son should not perform funeral rites of his parents.

In the past Badis were not allowed to cremate. he kings and nobles imposed such restrictions because cremation was done by Bahuns. So Badis were not allowed to do what Bahuns did. But nowadays Badi cremate the dead.

here is a belief that the pyre should be purchased. he chief mourner ofers two to three hundred rupees for the purchase of the pyre. After the body has been completely burned (or even if some small portions are not burnt) some pieces of the body are tied with the wat and placed in the river, which means that it reaches Kashi. Alternatively, the pieces are cooled in a religious site. hen the mourners bathe. he children of the dead have their heads shaved by the relative serving as the priest (Bahun). All ofspring of the dead should wear white clothes. All mourners bathe or sprinkle water on their bodies. In other communities, it is decided at the ghat the duration of death pollution. But in the case of Badis when the mourners return home they build a ire near the house, adding thorns and pressing both under a stone. he mourners next step on the stone, and then they are sprinkled with barley, sesame, and gold water and decide the duration of pollution, usually three, ive, seven, nine, eleven, or thirteen days. According to the elders, it is decided on the basis of the economic condition of the household. But usually it is seven days at the maximum.

On the day of puriication, the role of Bahun is paramount. he day before the puriication is the day of eating the katto (katto khane), when they go the river bank at three or four in the morning and the family members and the chief mourners eat chicken, yogurt, and milk, and the chief mourner also takes salt. On the day of puriication, because relatives and other people do not eat at the deceased’s house, they are given fruits. hey organize a feast by sacriicing a pig or a goat. he Bahun gives dana to the daughters and sisters by putting tika of yogurt, and puriies the house by sprinkling gold water. he Bahun is also discharged after they receive dakshina, as much as the household can give.

It is believed that the deceased would reincarnate in the animal whose ingerprints are found near the house during the night. A winnowing tray with ashes in it is placed in the rafter of the roof.

hado kriya is the rite performed the day after death, after noon of the next day.

After death, no one in the household is allowed inside other people’s house and vice versa. Badiss would not observe death pollution for a long time because they need to beg at other’s house for their daily food. Even if the deceased is not a close relative, they perform the thado kriya.

3.8.5 Festivals

As Badi are Hindus, they observe many Hindu festivals. here are some festivals which are observed diferently by the Badis, and they have diferent beliefs about such festivals.

he irst day of Asar month is celebrated by eating good and sweet food. In the rainy season, after Asar, Badis need to move through many hills and cross rivers when going from one village to another. As there is always the risk of falling or drowning in the rivers, they eat good food because of the danger and insecurity of their life in the month of Asar.

Ghiya Sankranti is the irst day of Bhandra month. he day is also called luto falne, or removing scabies. his festival is observed by taking a sigh of relief that they will survive for a year because the rainy season is over. Many dishes are made of ghee. hat night they discard the scabies. Because they needed to step in mud as