GREEN PRODUCTIVITY AS AN APPROACH TO ADDRESS

THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEM OF LEATHER TANNING SMEs

IN YOGYAKARTA, INDONESIA

DWI NINGSIH

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BOGOR

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Green Productivity as an Approach to Address the Environmental Problem of Leather Tanning SMEs in Yogyakarta, Indonesia” is my original work produced through the guidance of my academic advisors and have not been submitted to any tertiary institution. This thesis also presented for the award of a degree in The University of Adelaide as a double degree program between Bogor Agricultural University and The University of Adelaide. All of the incorporated material originated from other published or unpublished papers are stated clearly in the text as well as in the bibliography.

I hereby delegate the copyright of my paper to the Bogor Agricultural University.

Bogor, July 2015

SUMMARY

DWI NINGSIH, 2015. Green Productivity as an Approach to Address the Environmental Problem of Leather Tanning SMEs in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Supervised by ONO SUPARNO and SUPRIHATIN.

The leather tanning industry is a most promising industry in Yogyakarta. However, the industry faces environmental problems due to poor environmental management practices. This study develops strategies to address the environmental issues of the impact of leather tanning SMEs in Yogyakarta. It identifies opportunities for improvement based on Green Productivity (GP) approach, and obstacles to formulating strategies for enhancing environmental performance.

This study uses a Case Study approach using field observations and interviews with a number of leather tanning SMEs and industry experts. The results show that the SMEs in this sector adopt only a limited level of environmental practices. A set of GP options is proposed based on the observational evidence and expert judgements. Using an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a priority selected is to optimize the production processes of leather tanning SMEs.

This study found that internal obstacles to green adoption included insufficient resources and infrastructure, low-skilled human resources, poor financial capability, lack of awareness, and poor organizational strategies. The external obstacles are significant and include inadequate law enforcement and government support, a small and limited market segment, and the lack of available green chemicals. These contribute toward poor environmental practices.

To deal with these problems, this research proposes eight strategies for tackling the obstacles that prevent the implementation of leather tanning green practices. The strategies are divided into internal and collaborative. The internal strategies include encouraging enhanced product development processes and promote proactive and innovative strategies. Regarding their limitations, SMEs need stakeholder assistance to help solve their issues. A collaborative approach is crucial. Developing low-cost green technologies through R&D activities, developing best practice guidance and promoting its implementation, providing adequate facilities and machinery, identifying suitable suppliers to supply green chemicals, intensifying knowledge transfer of good environmental management, and establish a punishment and reward system are proposed for addressing the issues.

RINGKASAN

DWI NINGSIH, 2015. Green Productivity as an Approach to Address the Environmental Problem of Leather Tanning SMEs in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Dibimbing oleh ONO SUPARNO dan SUPRIHATIN.

Industri penyamakan kulit adalah industri yang menjanjikan di wilayah Yogyakarta. Namun, industri ini menghadapi permasalahan lingkungan dikarenakan praktek manajemen lingkungan yang rendah. Studi ini bertujuan untuk menyusun strategi dalam rangka penyelesaian permasalahan lingkungan yang timbul sebagai dampak dari proses penyamakan kulit oleh IKM di Yogyakarta. Penelitian ini mengidentifikasi peluang perbaikan berdasarkan pendekatan Produktivitas Hijau, dan hambatan yang dihadapi untuk selanjutnya menyusun strategi untuk meningkatkan kinerja lingkungan IKM.

Studi ini menggunakan studi kasus dengan tinjauan lapangan dan wawancara dengan sejumlah IKM dan ahli industri penyamakan kulit. Hasil studi menunjukkan bahwa IKM pada sektor industri ini masih terbatas dalam pengimplementasian praktek perlindungan lingkungan. Serangkaian opsi produktivitas hijau diusulkan berdasarkan dengan bukti observasi di lapangan dan pendapat ahli. Selanjutnya, menggunakan Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), prioritas yang terpilih adalah untuk mengoptimasi proses produksi penyamakan kulit.

Studi ini mengungkapkan bahwa hambatan internal dalam mengadopsi praktek hijau adalah terkait dengan sumber daya dan infrastruktur yang tidak memadai, sumber daya manusia yang kurang terampil, kemampuan keuangan yang rendah, kesadaran yang rendah, dan strategi organisasi yang rendah. Sedangkan hambatan eksternal adalah penegakan hukum dan dukungan pemerintah yang masih redah, segmentasi pasar yang masih terbatas dan keterbatasan ketersediaan bahan kimia ramah lingkungan. Hambatan ini yang menyebabkan rendahnya tingkat praktek lingkungan di lingkungan IKM.

Untuk menanggulangi permasalahan ini, studi ini mengusulkan delapan strategi untuk mengatasi hambatan yang menghalangi penerapan praktek hijau di IKM penyamakan kulit. Strategi ini dibagi menjadi internal dan kolaboratif strategi. Internal strategi yaitu mendorong peningkatan proses pengembangan produk dan mempromosikan strategi yang proaktif dan inovatif. Terkait dengan limitasi yang ada, IKM membutuhkan bantuan dari stakeholder lain untuk menyelesaikan permasalahan yang mereka hadapi. Sebuah kolaborasi diperlukan seperti mengembangkan teknologi hijau yang terjangkai melalui kegiatan R&D yang memadai, mengembangkan petunjuk praktek terbaik dan mempromosikan penerapannya, menyediakan fasilitas dan mesin yang memadai, mengidentifikasi ketersediaan supplier untuk menyediakan bahan kimia ramah lingkungan, mengintensifkan kegiatan transfer pengetahuan tentang managemen lingkungan yang baik dan menyediakan sistem hukuman dan penghargaan.

Copyright ©2015, by Bogor Agricultural University

All Right Reserved

1. No part or all of this thesis excerpted without inclusion or mentioning the sources

a. Excerption only for research and education use, writing for scientific papers, reporting, critical writing or reviewing of a problem

b. Excerption does not inflict a financial loss in the proper interest of Bogor Agricultural University

GREEN PRODUCTIVITY AS AN APPROACH TO ADDRESS

THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEM OF LEATHER TANNING SMEs

IN YOGYAKARTA, INDONESIA

DWI NINGSIH

Thesis

submitted as one of the requirements for achieving title Magister Science In Department of Agroindustrial Technology

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BOGOR

Thesis Title : Green Productivity as an Approach to Address the Environmental Problem of Leather Tanning SMEs in Yogyakarta, Indonesia Name : Dwi Ningsih

NRP : F351137071

Study Program : Agroindustrial Technology

Approved by

Advisory Committee

Prof Dr Ono Suparno, STP, MT Coordinator

Prof Dr Ir Suprihatin Co-supervisor

Acknowledged by

Head of Study Program of Agroindustrial Technology, IPB

Prof Dr Ir Machfud, MS

Dean of Graduate School of Magister Program, IPB

Dr Ir Dahrul Syah, MScAgr

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must start by thanking to Allah SWT, the Almighty, the most beneficent and the most merciful. I also want to express my gratitude to so many people for the supports, so that this thesis could be well completed as a requirement to get a Master Degree in Bogor Agricultural University (IPB). The title of the thesis is Green Productivity as an Approach to Address the Environmental Problem of Leather tanning SMEs in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

In particular, many thanks to my amazing advisory committee, both in IPB and UoA, Prof. Dr. Ono Suparno, S.TP., MT, Prof. Dr. Ir. Suprihatin and Prof Noel Lindsay, for their guidance, support and encouragement in every stage of my study.

I would like also thanks to Dr. Barry Elsey and Amina Omarova for the guidance and supports during the long workshops in the University of Adelaide. Thank you so much. Many thanks for the helps from the editor, Charles Clennell and Isabella Slevin.

Many thanks are also devoted to my brother, Sulistyanto, my sister-in-law, Eli Karlina Azis and my little niece, Shofia Nurul Izzati Al-Quds, and my other-mother in Adelaide, Joyce Hassan, for their supports. Many thanks to my fellow Double Degree program students, namely Nuni, Anin, Yani, Syarifa, Nur Aini, Karim, Tri, Benny, Andar, Farda, Iwan, Danang, Aditya, Dickie, Ahmad Rudh, and Koko. Finally we get to the end of this journey.

Finally, I must thank to my parents, this thesis I dedicated for both of you, my beloved mother, Waginah and father, Tasrip. Thanks for supporting me so far. Thanks so much, I feel nothing without your amazing supports.

Bogor, July 2015

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ... vi

LIST OF FIGURES ... vi

LIST OF APPENDIXES ... vi

1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

Research Background ... 1

Problem Statement ... 3

Research Questions ... 3

Research Objective ... 3

Research Benefits ... 3

Significance of Research ... 3

2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 4

Introduction ... 4

A glimpse of the Yogyakarta Leather Tanning Industry ... 4

Green Productivity (GP) ... 4

Barriers of SMEs in Green Practice Implementation ... 6

Strategy Formulation ... 7

Summary ... 8

3 METHODS ... 9

Introduction ... 9

Setting ... 9

Participants ... 10

Data Collection ... 10

Procedures ... 11

Data Analysis ... 11

4 RESULTS AND FINDINGS ... 12

Characteristics of Yogyakarta Leather SMEs ... 12

The Opportunities Identified to Achieve Better Environmental Performance (RQ1) ... 13

Prioritization of the Green Productivity Options using AHP (Analytical Hierarchy Process) ... 17

Obstacle Identification (RQ2) ... 17

Strategy Process Development (RQ3) ... 20

5 CONCLUSION ... 22

Summary ... 22

Implications of the research ... 22

Limitations of the research and future research directions ... 22

Recommendations ... 22

REFERENCES ... 23

APPENDIXES ... 26

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Export value of leather products from 2009-2013 ... 1

Table 2. GP projects in the leather industry ... 5

Table 3. Proposition 1 details ... 6

Table 4. Identified internal barriers ... 7

Table 5. Identified external barriers ... 7

Table 6. Proposition 2 details ... 7

Table 7. Proposition 3 details ... 8

Table 8. Research procedures ... 11

Table 9. SWOT analysis ... 20

Table 10. Strategy Classification ... 20

Table 11. More detailed discussion of strategies ... 20

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Map of Yogyakarta Province ... 1Figure 2. Leather processing waste ... 2

Figure 3. Research framework ... 9

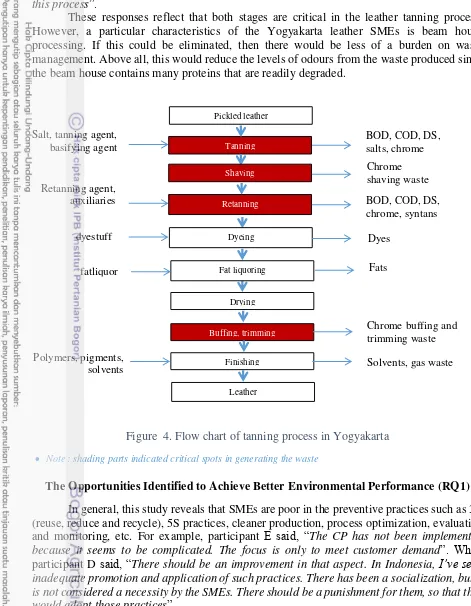

Figure 4. Flow chart of tanning process in Yogyakarta ... 13

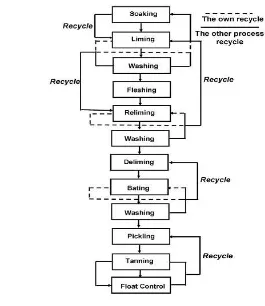

Figure 5. Special recycling economy model ... 15

Figure 6. Recycle of wastewater tannery with circular economy model ... 16

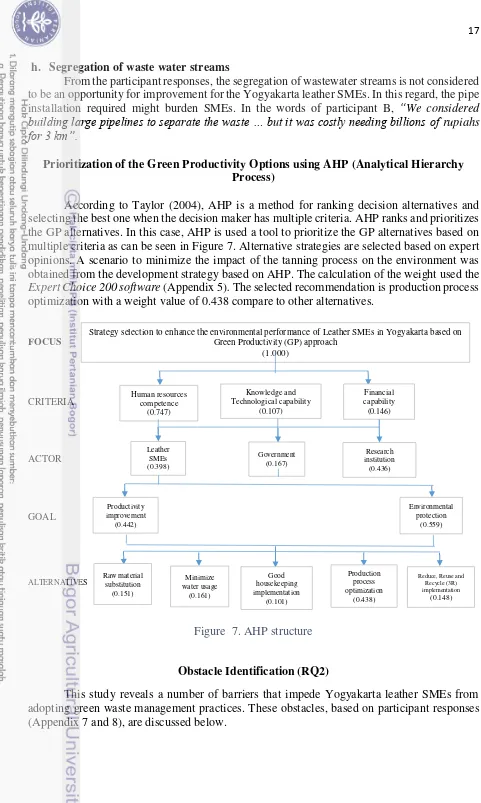

Figure 7. AHP structure ... 17

LIST OF APPENDIXES

Appendix 1. Glossary of Specific Terms ... 26Appendix 2. Profile of the SMEs ... 27

Appendix 3. Semi-Structure Questions and the analysis ... 28

Appendix 4. AHP questionnaire (sample per level of the hierarchy) ... 33

Appendix 5. AHP results ... 36

Appendix 6. The proposition GP options and the quotes... 38

Appendix 7. Proposition of Internal Obstacles and the quotes ... 40

Appendix 8. Proposition of External Obstacles and the quotes ... 42

Appendix 9. Proposition Strategies and the quotes ... 43

1

INTRODUCTION

Research Background

Leather is a most promising Indonesian industry as evidenced by the upward trend of international demand toward its leather products (Table 1). The industry is centralized in several main areas; namely, West Java, East Java, Central Java, Bali, Yogyakarta, and Jakarta. The main sourcing centres for the leather industry are in the East Java, West Java and Bali provinces. However, Yogyakarta is also an important sourcing centre because it has a role as a key supply zone that generates significant tourism sales.

Table 1. Export value of leather products from 2009-2013

Year Export value (million USD) Destination country

2009 178.4 US, Japan, Germany, Italy, Malaysia, Belgium, UK, Russia Federation, Egypt, Morocco, India, Taiwan, Canada, Australia, Georgia, Singapore, Algeria, Ecuador, France, South Africa

2010 246.4

2011 292.1

2012 324.7

2013 338.1

Yogyakarta is a provincial region in Indonesia located on Java Island (Figure 1). The economic structure of Yogyakarta is dominated by trade (21%), services (18%) and agriculture

(16%). Yogyakarta’s development is significant and includes two leading industries: leather manufacturing and textile processing. These two industries contribute significantly to the GDP, employment, investment, and development potential of the Province with multiplier effects to related industries in other provinces (Kemenperin, 2009). The focus of this research is on the leather tanning industry. Although this industry is well developed in Yogyakarta, there are significant waste management environmental problems such as the generation of significant liquid and solid wastes, and the emission of repulsive smells (because of the degradation of proteinous material of skin) and generation of gases such as NH3, H2S, and CO2 (Figure 2).

According to the Indonesian Tannery Association, approximately 75% of the leather industry firms are small and medium enterprises (SMEs). These SMEs have limitations which hinder their waste management environmental protection efforts. Previous studies (e.g., Hobbs 2000) have found that SMEs tend to be more harmful to the environment compared to larger corporations due to their poor production techniques. Other studies (e.g., Kanagaraj et al. 2006) have found that leather tanning SMEs in developing countries face significant waste disposal problems with many being closed for not meeting the required standards. This situation is similar in Indonesia, particularly in Yogyakarta, where there is a low level of adoption of leather tanning green practices (“Badan Lingkungan Hidup” (BLH)).1

Figure 2. Leather processing waste

Promoting sustainable strategy development is not an easy task; e.g. cleaner production, eco-efficiency, pollution prevention, etc. Most SMEs focus on the end-of-pipe (EOP) treatment which is less effective and disregard preventative management. In addition, the typical SME view of environmental protection is merely about added costs that are inopportune for the business. These perceptions prevent SMEs understanding the urgency in participating in the environmental protection efforts.

Green practice (GP) is a new concept that was introduced by the Asian Productivity Organization (APO) in 1992 which proposes a two-pronged approach that attempts to protect the environment without sacrificing the economic performance of a business. A number of scholars found benefits from GP implementation (Darmawan, Putra & Wiguna 2014; Mohan Das Gandhi, Selladurai & Santhi 2006; Singgih, Suef & Putra 2010; Sittichinnawing & Peerapattana 2012). A number of Indonesian studies was conducted but these were limited to the phenol and rubber industries. There is no evidence of any investigations into the Indonesian leather industry.

As stated by Al-Darrab (2000) cited in Logamuthu & Zailani S (2010), increasing global consumer environmental awareness has begun to pressure manufacturers and service providers to be more responsible regarding the impact of their processes on the environment. A series of studies during 1985 showed that more than a third (37.6%) of consumers require green products. They also were beginning to become concerned then as well about product disposals. In this regard, the Indonesian Government is looking to clean up “dirty” industries by introducing industry green policies (e.g., National Regulation 3, 2014).2 Consequently, leather tanning SMEs need to upgrade their existing practices and find better ways to solve

1 The BLH is an environmental agency in Yogyakarta which has identified that most leather tanning SMEs have not met the required environmental standards.

their challenges while developing better competitive advantages. Many Yogyakarta SMEs, however, claim that they are challenged in implementing green practices though there is no empirical evidence to support these claims.

In response to this lack of empirical evidence, this research has three main purposes:

(1) Identify green practice improvement options using a GP approach in Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs

(2) highlight the obstacles that inhibit green practice implementation, and

(3) formulate strategies to tackle these obstacles for better implementation of green practices.

Problem Statement

Most Yogyakarta leather SMEs have inadequate green practices leading to low levels of environmental performance. There are a number of factors that hinder the implementation of those practices. Moreover, the urgency of implementing such practices is considered insignificant by the SMEs because they tend to focus on their day-to-day activities while using their limited resources for the purposes of their business’ core operations.

Research Questions

RQ1. What opportunities can be identified to achieve better environmental performance for Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs?

RQ2. What are the principal obstacles that hinder improving their environmental performance? RQ3. What strategies can be proposed to overcome these obstacles?

Research Objective

This research aims to provide Green Practice recommendations and strategies for overcoming the main obstacles faced by leather tanning SMEs in order to achieve better environmental practices.

Research Benefits

The benefits of this study are:

a. Collection of empirical evidence of the existing green practices in the Indonesian leather industry, especially in Yogyakarta province

b. Guidance for enhancing green practices in Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs, and

c. The development of strategies to tackle the environmental issues associated with their businesses.

In addition, identification of the principal barriers to implementing green practices in Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs is a prerequisite to formulating better public policies to remove or mitigate environmental problems.

Significance of Research

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

Since leather is Yogyakarta’s primary industry, the sustainability of this industry is paramount. This can only be achieved through the development and implementation of appropriate environmentally friendly strategies. Good environmental performance can improve the poor corporate image of this industry; however, overcoming the low levels of green practice implementation which affect the poor environmental performance of leather tanning businesses is a huge challenge. In this Chapter, a number of topics are addressed. First, discussion occurs about the Indonesia leather tanning industry, particularly in Yogyakarta province together with its environmental problems. Second, a green practice (GP) approach to solving the problems is discussed, followed by the barriers to SMEs implementing GP, and what is needed to formulate appropriate GP strategies.

A glimpse of the Yogyakarta Leather Tanning Industry

Yogyakarta is one of the provinces on Java Island, Indonesia. It consists of one city (Yogyakarta) and four districts (Sleman, Bantul, Kulonprogo, and Gunung Kidul). Leather is the primary industry. It is a successful industry and it is spread across the Yogyakarta provincial region. According to the regulation of the Indonesian Ministery of Industry No. 138/M-IND/PER/10/2009, the Map Guide (Road Map) about “Industrial Development Yogyakarta Province”, the other leading industry is textile processing (Kemenperin, 2009). Yogyakarta SMEs generate significant export and local tourism sales.

Although the economic benefits of the leather industry are important, it has an adverse environmental impact (Ozgunay et al. 2007). During the manufacturing process, pollution occurs through the generation of toxic liquids and solid wastes which emit repulsive smells. Only one-fifth of the raw hides/skins are converted into products; the rest are discharged as waste or by-products. The tanning process produces 45-50m3 of waste water per ton of raw hides/skins (Kanagaraj et al. 2006). Tanning wastewater is a serious threat to the environment due to its content of strong alkalis, bio-waste, and heavy metals.

Most of the Indonesian leather industry is comprised of SMEs (small and medium enterprises). These, unquestionably, are a significant component of the Indonesian economy. They employ 97.16% of all workers and contribute toward 59.08% of Indonesia’s GDP (KemenkopUKM 2012). SMEs, however, are recognized as the largest contributors toward polluting the environment due to their substandard production techniques (Hobbs 2000).

Green Productivity (GP)

The Asian Productivity Organization (APO) defines GP as a strategy for enhancing productivity and environmental performance for socio-economic development (APO 2002). The APO proposed a concept that involves a customer focus (on quality) in achieving balance between profitability and environmental performance. GP is the application of appropriate productivity and environmental management tools, techniques, and technologies to reduce the

environmental impact of an organization’s activities.

including rubber, foundry, phenol, and cayenne pepper. GP benefits include increased product quality, reduced scrap, reduced pollution, and reduced risks for the enterprise (Logaa & Zailani 2013). Other benefits include cost savings in raw material purchases (Singgih, Suef & Putra 2010) and higher yields without compromising the environment (Sittichinnawing & Peerapattana 2012). Similar benefits have been associated with some projects in the leather industry which have been conducted by the APO. These projects identify various GP options in each industry in different countries (Table 2). The options proposed are based on a cause analysis, materials and component balance, literature survey, and brainstorming among team members and experts.

A study of GP in the context of Indonesian industry, however, is still limited though there are studies in two industry sectors: phenol and rubber (Darmawan, Putra & Wiguna 2014; Singgih, Suef & Putra 2010). Both studies have identified GP benefits in reducing the impact of industry processes upon the environment. In terms of the Indonesia leather industry, two studies focused on cleaning up production in two different areas in Indonesia, Garut and Bogor. They identified various improvement options (Alihniar 2011; Wardhana 2011). In Garut, the industry needs to improve its water usage control. In Bogor, chromium recycling has been identified as solving their environmental issues.

Table 2. GP projects in the leather industry

No GP projects Details data of the industry GP options

1 TANCHEM leather used by the garment and shoe manufacturing industries.

Number of worker: 30

The experts identified 45 GP options that divided into:

1. Good housekeeping 2. Process modification 3. Material change 4. Elimination & reduction 5. Equipment modification 6. Technology change, and

7. Recycle, reuse and recovery (3R). 2 NASSAU

The experts identified 59 GP options that divided into:

1. Good housekeeping 2. Process modification 3. Material change 4. Elimination & reduction 5. Equipment modification 6. Technology change

7. Recycle, reuse and recovery (3R) 3 SHUI-HUA cases and many other consumer goods.

Number of worker: >200

The expert proposed 7 main GP options: 1. Process improvement

2. Improve housekeeping

3. Separation of waste water streams 4. Recovery of chrome

5. Desalination 6. Resource recovery

It can be argued that although in the same sector industry, the improvement options proposed

might be different depending on a process’ characteristics such as the raw materials used,

technology applied, production processes adopted, etc. There have, however, been no studies in the context of the Yogyakarta leather industry. For this reason, we investigate the GP options for the Yogyakarta leather tanning industry and generate the propositions appearing in Table 3.

Table 3. Proposition 1 details

RQ: What opportunities can be identified to achieve a better environmental performance of leather SMEs in Yogyakarta?

Proposition

Proposition 1a: Good housekeeping Proposition 1b: Process improvement Proposition 1c: Material substitution Proposition 1d: 3R (reduce, reuse, recycle) Proposition 1e: Desalination

Proposition 1f: Water usage control Proposition 1g: Equipment modification

Proposition 1h: Segregation of waste water streams

Barriers of SMEs in Green Practice Implementation

Definitions of SMEs vary in each country. The SMEs in Indonesia have been defined based on the number of workers, income, and their amount of assets. Based on the Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) definition, a small business is an entity that has 5 to 19 workers, a medium-sized business is an entity that has 20 to 99 people.

In general, SMEs are focused on generating profits to keep their businesses operating. They are preoccupied with reducing resource use and waste in order to achieve short-term goals; however, this is not a priority if they do not gain associated benefits (Esty & Winston 2009). Wilson, Williams & Kemp (2012) found, for example, that UK SMEs see environmental innovation as a financial burden, and that they do not recognize the contributions toward the performance of environmental best practice. Thus, poor environmental practices exist because SMEs tend to focus on day-to-day activities ( Studer et al. 2008) with their resources restricted to issues related to their business’ core (Biondi, Frey & Iraldo 2000) rather than on green practices. Therefore, SMEs tend to be more reactive in tackling environmental problems. It is the larger companies that tend to be more proactive (e.g., Bianchi & Noci 1998; Hobbs 2000). SME reactive strategies focus more on compliance than sustainability (Hobbs 2000); they are not willing to contribute voluntarily. However, SME non-compliance is acknowledged and considered serious only if there is a threat of prosecution (Wilson, Williams & Kemp 2012).

Table 4. Identified internal barriers

Internal barriers Authors

Insufficient resources and infrastructure

Rojsek (2001); Brammer, Hoejmose & Marchant (2012); Tilley (1999);

Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres (2011)

Inadequate technical

knowledge and skills (human factor)

Hillary (2004); Rojsek (2001); Zilahy (2004); Moors, Mulder & Vergragt (2005); Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe & Rivera-Torres (2011)

High cost of environmental technologies (financial factor)

Hillary (2004); Rojsek (2001); Tilley (1999); Shi et al. (2008); Zilahy (2004), Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe & Rivera-Torres, (2007); Zutshi & Sohal (2004); Moors, Mulder & Vergragt (2005); Massoud et al. (2010); Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres (2011)

Lack of awareness Wilson, Williams & Kemp (2012); Tilley (1999); Zilahy, (2004).

Lack of organizational strategy Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres (2007); Zilahy (2004), Moors, Mulder, & Vergragt (2005); Massoud et al. (2010)

Aversion to innovation Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres (2011)

Table 5. Identified external barriers

External barriers Authors

Market segment for green product is too small

Rojsek (2001); Zilahy (2004)

The ‘green’ supplier support is

insufficient

Rojsek (2001); Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres (2011)

Poor environmental legislation Rojsek (2001); Wilson, Williams & Kemp (2012); Brammer, Hoejmose & Marchant (2012); Shi et al. (2008); Revell & Rutherfoord (2003); Moors, Mulder & Vergragt (2005) Limited government support Massoud et al. (2010)

Table 6. Proposition 2 details

RQ: What are the barriers that inhibit the implementation of the green practices Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs?

Proposition Internal barriers:

Proposition 2a: Insufficient resources and infrastructure

Proposition 2b Human factors Proposition 2c: Financial factors Proposition 2d: Lack of awareness

Proposition 2e: Organizational strategy factors Proposition 2f: Aversion to innovation

External barriers:

Proposition 2g: Market segment is too small Proposition 2h: Insufficient ‘green’ supplier support Proposition 2i: Poor environmental legislation Proposition 2j: Limited government support

Strategy Formulation

undertaken. It was informed by previous research and was the key tool for developing strategic plans for improving the environmental performance of Yogyakarta leather SMEs.

A variety of studies have identified various recommendations for better environmental practice implementation. For example, Tilley, F (1999), in his study of manufacturing and services small firms in the UK, found that better environmental practices can be achieved through more extensive environmental education and training, stronger regulatory frameworks, financial assistance, and better management guidance from stakeholders. The study undertaken by Zutshi & Sohal (2004), addressing several industrial sectors in Australia and New Zealand, also proposed training and communication as being key to addressing green management practice barriers. Government and policy makers also need to play a role in policing environmental regulatory breaches (Revell & Rutherfoord, 2003). For example, Rojsek (2001), in his study in Slovenia, found that enhancing technical progress and applying stricter environmental regulations are crucial. In addition, Lee (2009) argued that SMEs are capable of making themselves greener by making strategic and organizational changes. Based on these studies, additional propositions were developed (refer Table 7).

Table 7. Proposition 3 details

RQ3: What strategies can be proposed to tackle the existing barriers?

Proposition

Proposition 3a: Intensifying education and training programs Proposition 3b: Providing financial assistance

Proposition 3c: Providing environmental management guidance Proposition 3d: Stricter environmental regulation

Proposition 3e: Encouraging the organizational change process

Summary

3 METHODS

Introduction

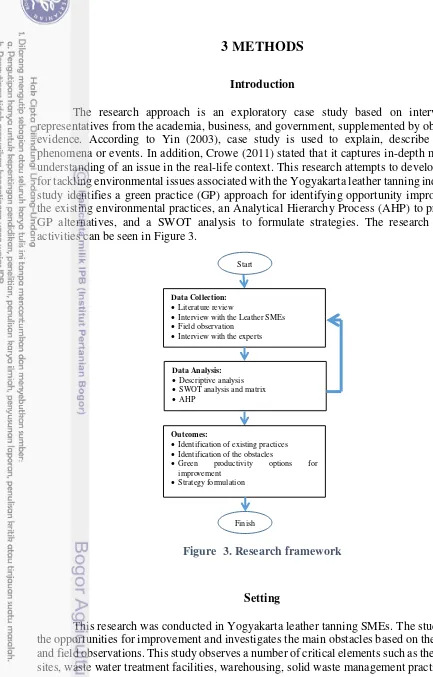

The research approach is an exploratory case study based on interviews with representatives from the academia, business, and government, supplemented by observational evidence. According to Yin (2003), case study is used to explain, describe or explore phenomena or events. In addition, Crowe (2011) stated that it captures in-depth multifaceted understanding of an issue in the real-life context. This research attempts to develop strategies for tackling environmental issues associated with the Yogyakarta leather tanning industry. This study identifies a green practice (GP) approach for identifying opportunity improvements in the existing environmental practices, an Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to prioritize the GP alternatives, and a SWOT analysis to formulate strategies. The research framework activities can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Research framework

Setting

This research was conducted in Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs. The study explores the opportunities for improvement and investigates the main obstacles based on the interviews and field observations. This study observes a number of critical elements such as the processing sites, waste water treatment facilities, warehousing, solid waste management practices.

Data Collection:

Literature review

Interview with the Leather SMEs Field observation

Interview with the experts

Data Analysis:

Descriptive analysis SWOT analysis and matrix AHP

Outcomes:

Identification of existing practices Identification of the obstacles

Green productivity options for improvement

Strategy formulation Start

Participants

The participants were purposively sampled based on their experience and knowledge: a. Participant A (RA): The owner of AA enterprise, Yogyakarta leather SME

b. Participant B (RB): The owner of BB enterprise, Yogyakarta leather SME

c. Participant C (RC): Head of Division, Centre for Leather, Rubber and Plastics (CLRP), Yogyakarta

d. Participant D (RD): Head of the Indonesian Tanneries Association

e. Participant E (RE): Lecturer at the Academy of Leather Technology, Yogyakarta

The details of the SME participants can be seen in Appendix 2. Participant C was chosen due to his experience in leather processing and waste management. Participant D was chosen due to his experience and knowledge as Head of the Association and as owner of a larger Yogyakarta leather SME. Participant E was selected because of her expertise as a lecturer in the leather-based institution.

Data Collection

This research collected both primary and secondary data. The primary data was collected through field observations and interview with the respondents. The secondary data was based on the literature review of prior studies, government reports, and government statistical data. The tools used in collecting the primary data were:

a. Interview Questions (Appendix 3)

Interview durations ranged between 45-90 minutes per respondent. These were conducted using semi-structure interview scripts. All interviews were recorded with additional note-taking during the interview. All recordings were transcribed for analysis.

b. Questionnaire from the AHP (Appendix 4)

A questionnaire was sent to the experts via e-mail. Responses were analyzed using expert

Procedures

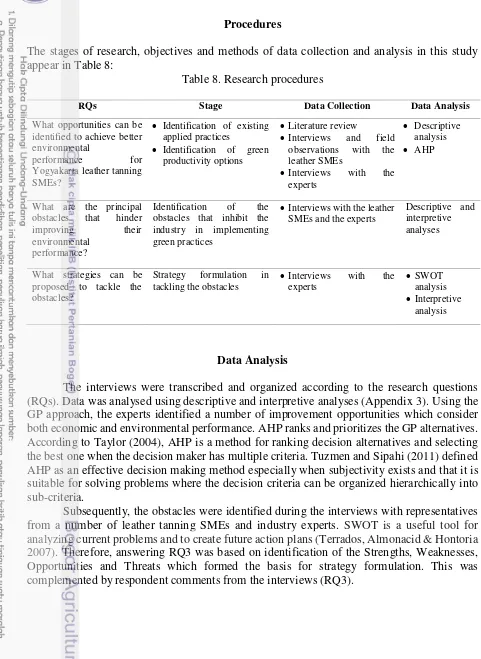

The stages of research, objectives and methods of data collection and analysis in this study appear in Table 8:

Table 8. Research procedures

RQs Stage Data Collection Data Analysis

What opportunities can be identified to achieve better environmental

performance for Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs?

Identification of existing applied practices

Identification of green productivity options

Literature review

Interviews and field observations with the leather SMEs obstacles that hinder improving their environmental

performance?

Identification of the obstacles that inhibit the industry in implementing green practices

Interviews with the leather SMEs and the experts

Strategy formulation in tackling the obstacles

The interviews were transcribed and organized according to the research questions (RQs). Data was analysed using descriptive and interpretive analyses (Appendix 3). Using the GP approach, the experts identified a number of improvement opportunities which consider both economic and environmental performance. AHP ranks and prioritizes the GP alternatives. According to Taylor (2004), AHP is a method for ranking decision alternatives and selecting the best one when the decision maker has multiple criteria. Tuzmen and Sipahi (2011) defined AHP as an effective decision making method especially when subjectivity exists and that it is suitable for solving problems where the decision criteria can be organized hierarchically into sub-criteria.

4 RESULTS AND FINDINGS

Characteristics of Yogyakarta Leather SMEs

Typically, the Yogyakarta SME leather tanning process starts with “pickling” and not from treating the rawhides/skins (Figure 4). The industry argues that commencing the process with pickling is more efficient and can reduce waste, odours and sludge. For example, participant B said,“The reason (for starting with pickling) is environmental. This location is already configured as a leather factory site but it is still close to population centers. And their

focus is the smell of the waste”.Also, in the words of participant A, “If you do not want to

have a longer process, and do not wish to have a problem with the community, do not start the

process from processing the raw hides/skins”. However, while there is a realization that environmental considerations will be a challenge in the future, these are not a priority for the SMEs because there is little pressure from regulatory bodies or customers to comply. For example participant A said, “It will affect the environment if the effluent is not treated.” However, participant A also said, “As long as there are no complaints …. I think that is okay. But, a consequence of the industry is to generate waste. I have tried to minimize the waste but

as long as the cost is reasonable”.

These types of comments suggest that the Yogyakarta SME environmental leather problems are unresolved. These SMEs have no special treatments for solid and gas waste, nor for waste-water. Critically, they do not regularly monitor and/or evaluate treatment results. Regulatory enforcement is an issue because of customer apathy toward green practices since most customers are local and focus on quality and price - not environmental issues. Thus, SMEs do not focus on preventive pollution management.

In terms of the generated waste, most of the respondents agreed that solid waste appears to be the biggest problem which needs to be tackled. In the words of participant C, “The hardest problem is chrome. Chrome content causes the waste to be classified as hazardous and toxic waste. Because its handling cost is quite high, it is impossible for SMEs to manage their solid waste individually. The government sees that their wastewater effluent has not met the requirements, but at least they have tried. While there is no alternative choices available for

the solid waste”.

These responses indicate that the industry, particularly the SMEs, feel burdened with solid waste management due to the considerable costs involved. Chrome content in solid waste and sludge requires the industry to pay for the particular treatment associated with dealing with this. Based on Regulation 101 Year 2014 regarding the Handling of Hazardous Materials and Toxic Waste, SMEs need to pay for the treatment which is costly even for larger companies. In the words of participant D, “The range of costs for one truck of solid waste took 30 million

rupiahs. It is already a heavy burden for the industry”. This evidence explains the reluctance

“The hardest part is always in the beam house operation. Therefore, the industry tends to avoid this process”.

These responses reflect that both stages are critical in the leather tanning process. However, a particular characteristics of the Yogyakarta leather SMEs is beam house processing. If this could be eliminated, then there would be less of a burden on waste management. Above all, this would reduce the levels of odours from the waste produced since the beam house contains many proteins that are readily degraded.

Figure 4. Flow chart of tanning process in Yogyakarta

Note : shading parts indicated critical spots in generating the waste

The Opportunities Identified to Achieve Better Environmental Performance (RQ1)

In general, this study reveals that SMEs are poor in the preventive practices such as 3R (reuse, reduce and recycle), 5S practices, cleaner production, process optimization, evaluation and monitoring, etc. For example, participant E said, “The CP has not been implemented

because it seems to be complicated. The focus is only to meet customer demand”. While

participant D said, “There should be an improvement in that aspect. In Indonesia, I’ve seen inadequate promotion and application of such practices. There has been a socialization, but it is not considered a necessity by the SMEs. There should be a punishment for them, so that they

would adopt those practices”.

These types of comments indicate that SMEs lack green practices because of poor law enforcement which makes them reluctant to implement such practices voluntarily. Lack of

Salt, tanning agent, basifying agent

BOD, COD, DS, salts, chrome

Chrome shaving waste Retanning agent,

auxiliaries BOD, COD, DS,

chrome, syntans

Chrome buffing and trimming waste

Polymers, pigments,

solvents Solvents, gas waste

dyestuff

fatliquor

Dyes

Fats Pickled leather

Tanning

Shaving

Retanning

Drying

Buffing, trimming

Finishing

Leather Dyeing

knowledge seems to be another reason which results in the low level of environmental practices in this area.

Subsequently, this study found a number of green waste management practice improvement opportunities that may be suitable for Yogyakarta leather SMEs. These opportunities, based on participant responses (Appendix 6) and supplemented by field observations, appear below.

a. Good housekeeping

According to participant responses, good housekeeping seems to be one of the improvement opportunities for Yogyakarta leather SMEs. As stated by participant C,”SMEs use chemicals carelessly. They have prepared the chemicals in a packing for the basis of 1 ton of materials, without considering the loss of the materials weight during the process. For

example after the splitting process, the weight must be different”. In this case, good

housekeeping is not only related to keeping the workplace clean and eliminating leaks and spills, but it is also relevant for operational improvement procedures for resource consumption efficiencies (for example, in the preparation of the formula for the tanning process to avoid surplus chemicals used). More precise measurements are required. These practices could reduce 20-25% of the waste generated (APO 2002). SMEs tend to be careless in using chemicals. It might be because there is inadequate information related to good housekeeping practices.

b. Process improvement

Chrome is the most hazardous chemical affecting the environment. Process improvement is considered as a way to minimize chrome content in the waste. During the tanning process, leather absorbs only 60-80% of Cr2(SO4)3 and the rest is discharged as waste (Garg et al. 2007; Belay 2010). Minimizing chrome content waste can only be achieved by enhancing the absorbing capability of chrome through a particular technological process. A range of studies have examined how new technologies can reduce the amount of waste. For example a study by Suresh et al. (2001) found a technology that reduces the chemical oxygen demand (COD), total dissolved solids (TDS), and chlorides in the spent tan liquor by 51, 81 and 99%, consecutively. Another study by Morera et al. (2007) reduced the residual float, the chrome content, and the chlorides discharged by 75%, 91% and 94 % respectively. Both studies claim that they can still produce good quality products and make them techno-economically viable. However, it seems difficult for Yogyakarta SMEs to apply the latest technologies. It could be argued that there might be inadequate transfer technologies which lead SMEs to stick to the traditional methods.

c. Material substitution

Participant responses indicate that chrome seems to be irreplaceable for SME processes. More environmentally friendly tanning agents such as vegetable agents are unlikely to replace chrome even though this is biodegradable. Chromium tanning is superior in comparison to vegetable tanning agent in terms of hydrothermal stability and strength characteristics (Ali, Rao & Nair, 2000). It also has an exceptional mechanical resistance and an excellent dyeing suitability (Belay 2010). To achieve the same characteristics, vegetable tanning needs additional chemicals which create slightly higher production costs. In the words of participant

D. “It requires approximately 30 cents additional cost per 1 sqft hide or skin, for the chemicals

lack of information about the latest leather tanning technology. Thus, SMEs apply traditional technologies in operating their tanning processes. Therefore, based on expert opinion, the substitution of toxic and hazardous materials is still considered a promising alternative. To encourage SMEs to apply this recommendation, it requires low-cost green technology that can substitute the predominance of chrome as a tanning agent. For example, a study by Morera et al. (2007) found an alternative tanning process which can give benefits of 32% more economic benefits than the traditional approach. The technology reduces clean water consumption and finishes the tanning at 55 0C. The characteristics of the finished leather are no different with that produced by the traditional technology and it can create considerably savings in the water supply. The process reduces the residual float, the chrome content, and the chlorides discharged by 75%, 91% and 94 % respectively.

d. Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle (3R)

This study reveals that SMEs are poor in 3R practices. According to participant responses, there is room for improvement to reuse, reduce, and recycle chrome, lime, sulfide, salt, pickling waste, waste water, fleshing, sludge, etc. However, it seems that the SMEs are reluctant to adopt such practices because it requires additional costs for operations, increased costs associated with high-skilling of human resources, and the use of more sophisticated technology. These three factors seem to be the largest obstacles to implementing 3R practices.

Hu et al. (2011) developed a recycling economy model (Figure 5) to depict the recycling process in the leather tanning industry by applying the reduce, reuse, and recycle or recovery system. They proposed that this should apply to the whole recycle tannery process (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Special recycling economy model

The most common techniques for this practice are chemical precipitation, membrane processes, adsorption, redox adsorption, and ion exchange. As stated by Belay (2010), the membrane process offers more compelling benefits compared to other alternatives for recovery and recycling the spent liquors of soaking, unhairing, degreasing, pickling, dyeing, and chromium tanning. In the words of participant C, “Unlike pickle recycling, SMEs need equipment and additional chemicals to recycle sulfide and chrome. However, these efforts are not worth enough because they require extra costs for the human resources and chemicals

Figure 6. Recycle of wastewater tannery with circular economy model

e. Desalination

From the participant responses, desalination is not considered an opportunity to improve Yogyakarta leather SMEs. This is due to the leather tanning process in Yogyakarta not starting from raw hides/skins. The process that is adopted is spared from conventional methods that use nearly 40-50% salt to preserve the raw hides/skins (Hu et al. 2011).

f. Water usage control

The tanning process produces significant waste water - approximately 45-50m3 of waste water per ton raw hide/skin production (Kanagaraj et al. 2006). Therefore, the minimization of water usage can be a real opportunity for the industry if it can also minimize production costs as well as the waste generated. As stated by Dandira (2013), water management is critical for the leather tanning industry because it is a water-intensive industry. Ideally, any innovative process would reduce 30% or more from the total water needed. Another way of improving the process involves recycling the water; e.g. soaking, liming, and/or unhairing - which can reduce 20% of water consumption. Morera et al. (2007) achieved both benefits: reducing water consumption and the disposal of chrome which was economically viable.

g. Equipment modifications

h. Segregation of waste water streams

From the participant responses, the segregation of wastewater streams is not considered to be an opportunity for improvement for the Yogyakarta leather SMEs. In this regard, the pipe installation required might burden SMEs. In the words of participant B, “We considered

building large pipelines to separate the waste … but it was costly needing billions of rupiahs

for 3 km”.

Prioritization of the Green Productivity Options using AHP (Analytical Hierarchy Process)

According to Taylor (2004), AHP is a method for ranking decision alternatives and selecting the best one when the decision maker has multiple criteria. AHP ranks and prioritizes the GP alternatives. In this case, AHP is used a tool to prioritize the GP alternatives based on multiple criteria as can be seen in Figure 7. Alternative strategies are selected based on expert opinions. A scenario to minimize the impact of the tanning process on the environment was obtained from the development strategy based on AHP. The calculation of the weight used the

Expert Choice 200 software (Appendix 5). The selected recommendation is production process

optimization with a weight value of 0.438 compare to other alternatives.

FOCUS

CRITERIA

ACTOR

GOAL

ALTERNATIVES

Figure 7. AHP structure

Obstacle Identification (RQ2)

This study reveals a number of barriers that impede Yogyakarta leather SMEs from adopting green waste management practices. These obstacles, based on participant responses (Appendix 7 and 8), are discussed below.

Internal Obstacles

a. Insufficient resources and infrastructure

Some participants considered “insufficient resources and infrastructure” as a key factor that hinders green practices. This is consistent with previous research (Rojsek 2001; Brammer, Hoejmose & Marchant 2012; Tilley 1999; Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres 2011). Limited infrastructure and resources negatively impact efforts to protect the environment. Most SMEs use only simple treatments, simple chemicals, and no biological treatments for waste. With limited staffing, they cannot focus on environmental aspects but only day-to-day activities (Studer et al. 2008). This obstacle makes it difficult for SMEs to participate in environmental efforts because it clearly requires sufficient resources and infrastructure which they do not have. SMEs need assistance in providing adequate resources and infrastructure to greening their businesses.

b. Human factors

Most participants identified staff as a key factor that hinders green practice implementation. This is consistent with prior studies (Hillary 2004; Rojsek 2001; Zilahy 2004; Moors, Mulder, & Vergragt 2005; Murillo-Luna, Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres 2011). Low-skilled human resources have prevented positive organizational change. According to Lee (2009), human factors are one of the most cited SME barriers to adopting green management and that green businesses require high levels of human resource skills because of the need to develop innovation-focused environmental initiatives. Thus, the enhancement of human resource competency in Yogyakarta leather SMEs should be investigated.

c. Financial factors

Participants agreed that financial factors are a significant barrier; thus, it is a challenge for SMEs to innovate (Hart 2005). Environmental innovation is seen as a financial burden (Wilson, Williams & Kemp 2012) and is not considered a priority (Esty & Winston 2009). This factor seems to be the most significant factor that burdens SMEs. One solution may be for SMEs to develop a collaborative partnership which can lighten their financial burden.

d. Lack of awareness

This study reveals that awareness about environmental protection in SMEs varies. Some of them are aware, yet some do not see this issue as a big deal to be overcome. This was depicted by Tilley (1999) who examined the gap between environmental attitudes and the environmental behavior of small firms. Consistent with Tilley (1999), SME awareness varies with some not seeing green as important. This factor seems to be a high priority to overcoming the problem. This might become the duty of the government - to encourage the industry and facilitate SME socialization to enhance their awareness of the environment.

e. Organizational strategy factor

Participant responses confirmed previous studies that SMEs adopt reactive strategies rather than proactively contribute to environmental protection efforts (Bianchi & Noci 1998; Hobbs 2000) focusing on compliance rather than sustainability. (Hobbs 2000). In the words of

participant A, “If I need to comply with the environmental requirements, I will look for a way to comply. But, for now, I do not want to. As long as there is no problem with customers, it will

be fine ... No need for additional costs, additional human resources”. This type of comment

of awareness among SMEs. SMEs need to be convinced by the government about the benefits of applying proactive strategies.

f. Aversion to innovation

Although the level of SME innovation is low, no participant considered this factor a principal barrier. This problem might be more an organizational factor.

External Barriers

a. Market segment is too small

The results suggest that SMEs focus on customer requirements. Most customers are local, do not require any green environmental aspects (i.e., Eco-labelling products, ISO 14001 certification, etc), and tend to focus on appearance and price. Thus, SMEs seems to feel that it is not necessary to implement green practices. This finding is consistent with Rojsek (2001) and Zilahy (2004).

b. Insufficient ‘green’ supplier support

Raw material prices are a sensitive issue for SMEs. If they have a choice between the environment and economic benefits, then economics will always dominate. With limited finances, SMEs ignore environmental considerations. Most of the imported green chemicals are more expensive compared to the local chemicals that are commonly used. In the words of participant D, “The consequence of producing green products … is a significant price

increase.” This is consistent with previous research (Rojsek 2001; Murillo-Luna,

Garcés-Ayerbe, & Rivera-Torres 2011). This type of comment demonstrates that SMEs focus on production costs and gained profits. Thus, the availability of green materials and/or their higher price make SMEs reluctant to purchase green materials.

c. Poor environmental legislation

According to Kwong (2002), cited in Logaa & Zailani (2013), pollution preventive management and waste management to protect the environment have not worked in many countries. The reasons typically are poor regulation and an industry view that environmental protection is an added cost. In Indonesia (a developing country), the regulations are not strictly enforced. This causes SMEs to feel no obligation to adopt green practices. This is consistent with Wilson, Williams & Kemp (2012) who found that SMEs have poor awareness of compliance issues.

d. Limited government support

The results are also consistent with Massoud et al. (2010). Most participants considered that SMEs need government support to deal with the installation of communal waste water treatment facilities. However, the support for this is limited. For example, participant C said,

“Unlike Garut and Magetan, in Yogyakarta, there is no integrated waste treatment plant for

the leather industry”. This is supported by participant D, “There is a plan to build an integrated

Strategy Process Development (RQ3)

Strategy development was aligned with the previous results and those identified based on participant responses (Appendix 9). Using the participant interviews, a SWOT analysis was conducted to determine possible strategies to tackle the barriers to current environmental practices (Table 9). Strategies formulated according to SWOT appear in Appendix 10.

Table 9. SWOT analysis

STRENGTHS

(S1) Have a localized land area for leather tanning

(S2) Competent and experienced in producing good quality products

WEAKNESSES

(W1) Inadequate data and low-skilled human resources in environmental management (low in competency, knowledge, and commitment)

(W2) Inadequate facilities, machinery, and funding

(W3) A focus on end-of-pipe treatment c.f. preventive management (W4) Limited access to more environmentally-friendly chemicals

OPPORTUNITIES

(O1) Increasing trend of leather product demand

(O2) Availability of stakeholders concerns with the leather industry such as government (CLRP), association (APKI), and academician (ATK)

(O3) Substitution products of chromium as a tanning agent

THREATS

(T1) Future demands directed to green products

(T2) Environmental regulations will be increasingly strictly enforced (T3) Have not found cost-effective environmentally-friendly technologies

Table 10 summarizes the strategies developed. These are classified as internal and collaborative. Table 11 discusses these in more detail. Collaborative strategies suggest that SMEs need stakeholder support to green their businesses since the use of stakeholders enhance environmental management practices (Tilley 1999; Woo et al. 2014). However, stakeholders are not always ready to assist ( Moorthy et al. 2012). Thus, for greater effectiveness, both internal and collaborative strategies should be adopted.

Table 10. Strategy Classification

Internal strategies

1. Encourage product development processes 2. Promote proactive and innovative strategies Collaborative strategies

1. Develop low-cost green technology through R&D activities 2. Develop best practice guidance and promote its implementation 3. Provide adequate facilities and machinery

4. Provide suppliers to supply the green chemicals

5. Intensify knowledge transfer of good environmental management 6. Establish a punishment and reward system

Table 11. More detailed discussion of strategies

Strategy 2 Promote proactive and innovative strategies: SMEs need to shift from reactiveness to proactiveness and develop innovative strategies. SMEs with high innovation capabilities are associated with progressive green management practices (Noci and Verganti 1999).

Strategy 3 Develop low-cost green technology through R&D activities: Technological innovation is challenging. There needs to be collaboration between SMEs, government, and research institutions (Lee 2009).

Strategy 4 Develop best practice guidance and promote its implementation: SMEs can make themselves greener through organizational change (Lee 2009). There should be collaboration, with the government providing guidance on best practice (Tilley 1999).

Strategy 5 Provide adequate facilities and machinery: Government should investigate providing communal waste treatment facilities.

Strategy 6 Provide suppliers to supply green chemicals: Internal and external stakeholders to enhance green management practices are essential. Local suppliers to be encouraged to provide green chemicals.

Strategy 7 Intensify knowledge transfer of good environmental management: Environmental training programs should be conducted to assist SMEs change their attitudes and behaviors toward green practice.

Strategy 8 Establish a punishment and reward system: A stricter environmental regulation approach needs to be enforced (Rojsek 2001).

The majority of the strategy proposed are collaborative strategies which need other stakeholder participation. As stated by a previous study, there are four critical groups of stakeholders, who influenced or are influenced by the company’s activities, namely regulatory, organizational, community, and media stakeholders (Henriques and Sadorsky 1999 cited in Rojsek 2001). The finding of the study by Rojsek (2001) found that top management is the

most important source of pressure for better company’s environmental performance. While the government is in the second level priority who has the responsibility to prevent environmental depletion caused by the industry.

Regarding the limitation of the Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs in the environmental protection efforts, it seems to be unlikely to initiate the implementation from the internal stakeholder, e.g., top management. Therefore, it seems that the government becomes the key stakeholders in attempt to enhance the environmental performance of leather tanning SMEs.

In addition, there are six collaborative strategies which need government participation to initiate the strategy implementation. As the key stakeholder in enhancing the performance, the government needs to encourage the participation of the industry in the environmental protection efforts. For example in the word of respondent D, “Socialization related green practices has been conducted, but the SMEs does not consider it as a priority. Punishment

seems to be the way to encourage the SMEs to implement such practices”. It is supported by

participant C responses, “Control from the government need to be improved, and the

punishment should be enforced”.While participant E stated that “In improving the awareness, the government need to provide punishment but have to be balanced by giving the SMEs the

solution to tackling the environmental issue.”

5 CONCLUSION

Summary

This study used purposeful sampling to examine waste management problems associated with Yogyakarta leather producing SMEs. A set of improvement opportunities is developed to enhance the environmental performance of the SMEs. These options are identified based on the participant responses supplemented by field observation. Process optimization is considered as the best recommendation for Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs to overcome the environmental issue faced by them.

In addition, these SMEs face a range of limitations and need assistance to adopt green management practices. These limitations are related to the factors which come from internal and external organizations. These factors hinder the Yogyakarta leather tanning SMEs to contribute in the adequate environmental management practices.

A set of strategies proposed in this study is expected to successfully assist SMEs in solving the environmental issues. Both, internal and collaborative strategies are proposed. However, for greater effectiveness, both internal and collaborative strategies need to be adopted.

Implications of the research

Practically, SMEs might adopt the alternatives proposed (GP options) in this study to enhance their environmental performance which can provide benefits at social, economic, and environmental levels. As the strategic implication, SMEs might promote proactive strategies within their businesses. In addition, barriers investigation are useful for formulating strategies to cope with the future. A thorough investigation of the apparent barriers is needed for formulating better strategies so that these can be removed or mitigated. In the term of policy making, the findings of this study can be used for developing good SME environmental management practices. Lastly, this research contributes toward existing theory and provides the basis for future research. Process optimization might be considered as one of the strategies to improve SME environmental performance.

Limitations of the research and future research directions

A limitation of this pilot research is the small sample size used and the purposeful sampling adopted. Thus, caution should be exercised in generalizing the results of this research. However, respondents were selected for particular reasons due to their expertise and knowledge. Future studies may consider embracing a larger and more randomly selected sample.

Recommendations

REFERENCES

Ali, SJ, Rao, JR, & Nair, BU 2000, ‘Novel approaches to the recovery of chromium from the chrome-containing wastewaters of the leather industry’, Green Chemistry, 2(6), 298-302.

Alihniar F 2011,’Study on Cleaner Production Implementation in Leather Tanning Industry: A Case Study in Cibuluh, North Bogor Sub-District’, undergraduate thesis, Bogor Agricultural University, Indonesia

APO 2002, Green productivity: Training manual, viewed 20 February 2014, <http://www.apo-tokyo.org/00e-books/GP-02_TrainerManual.htm>.

Belay, AA 2010, 'Impacts of chromium from tannery effluent and evaluation of alternative treatment options', Journal of Environmental Protection, 1(01), 53.

Bianchi, R & Noci, G 1998, '" Greening" SMEs' Competitiveness', Small Business

Economics, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 269-281.

Biondi, V, Frey, M & Iraldo, F 2000, 'Environmental Management Systems and SMEs',

Greener Management International, no. 29, Spring2000, p. 55.

Brammer, S, Hoejmose, S & Marchant, K 2012, 'Environmental management in SMEs in the UK: practices, pressures and perceived benefits', Business Strategy and the

Environment, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 423-434.

Dandira, VS & Madanhire I 2013,'Design of A Cleaner Production Framework to Enhance Productivity: Case Study of Leather Company, International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), India Online ISSN: 2319-7064

Darmawan, MA, Putra, MPIF & Wiguna, B 2014, 'Value chain analysis for green

productivity improvement in the natural rubber supply chain: a case study', Journal

of Cleaner Production, vol. 85, pp. 201-211.

Esty, D & Winston, A 2009, 'Green to gold: How smart companies use environmental strategy to innovate, create value, and build competitive advantage', John Wiley & Sons.

Garg, UK, Kaur, MP, Garg, VK, & Sud, D 2007, 'Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution by agricultural waste biomass', Journal of Hazardous

Materials, 140(1), 60-68.

Hillary, R 2004, 'Environmental management systems and the smaller enterprise' Journal of cleaner production, 12(6), 561-569.

Hobbs, J 2000, 'Promoting cleaner production in small and medium-sized enterprises', in

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises and the Environment: Business Imperatives,

vol. 148, Greenleaf Publishing in association with GSE Research, pp. 148-157.

Hu, J, Xiao, Z, Zhou, R, Deng, W, Wang, M, & Ma, S 2011, 'Ecological utilization of leather tannery waste with circular economy model', Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(2), 221-228.

Kanagaraj, J, Velappan, K, Chandra Babu, N & Sadulla, S 2006, 'Solid wastes generation in the leather industry and its utilization for cleaner environment-A review', Journal

of scientific and industrial research, vol. 65, no. 7, pp. 541-548.

Kangas, J, Kurttila, M, Kajanus, M, & Kangas, A, 2003, 'Evaluating the management strategies of a forestland estate—the SOS approach', Journal of environmental management, 69(4), 349-358.