Autism Spectrum Disorder and Memory

Seema Nath

Supervisor: Dr. Claire Hughes

June 15th, 2012 Total words: 11, 079

Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of

Master of Philosophy in Social and Developmental Psychology

Division of Social and Developmental Psychology

Faculty of Human, Social and Political Science

University of Cambridge

Abstract

A number of risk factors indicate that children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are

represented in the criminal justice system as witnesses and victims of crime. The present study

attempts to understand the memory capabilities and quantity of recall in children with Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD) when compared with typically developing children specifically in

terms of episodic and semantic memory systems. The study employed a personal interview and a

words list paradigm respectively to study the episodic memory and the semantic memory under

free and cued recall conditions. In addition, the study examines the effect of the severity of ASD

on memory. The results show that children with ASD perform worse than typically developing

children in the episodic memory task while the children with ASD perform on par with the

typically developing children in the semantic memory task under both free and cued recall

conditions. Severity of the symptoms of ASD has a negative effect on the performance in both

the episodic and semantic memory task. The results imply that the severity of the ASD should be

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Claire Hughes whose able guidance made

this thesis possible. Thank you for cautioning me about the challenges of recruitment and yet

supporting me throughout my research. I would also like to thank Dr. Napoleon Katsos for

lending me the TROG-2 which was an integral part of the research.

I would also like to take this opportunity to thank all the schools in India who took part in the

study. I am very grateful for the support from the Director, Principal, staff and students at

Tamana School, the School of Hope, Prerona School, Carmel School, Springdale School and

Don Bosco School.

I owe my deepest gratitude to the Cambridge Commonwealth Trust for providing me with a

scholarship that helped me undertake this MPhil in Social and Developmental Psychology.

I am very thankful to my colleagues; Katherine, Laura, Nik, Divya and Amanda for keeping the

study sessions interesting and all their encouragement. It is my great pleasure to thank my friends

who made my time at the University of Cambridge so much fun, thank you Ashley, Lisa,

Karishma, Rebecca and Lydia.

Last but not the least; I would like to thank my parents and sister for their constant support and

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2

Acknowledgements ... 3

Table of Contents ... 4

List of Figures ... 5

Introduction ... 6

Autism Spectrum Disorder ... 6

Cognitive theories of autism ... 8

General overview of memory deficits in children with ASD ... 11

Free and cued recall in children with ASD ... 15

Implication of memory in child witness testimony in children with ASD ... 17

Relevance of the study ... 19

Research Questions and Hypothesis ... 20

Method - Participants ... 21

Method - Measures ... 23

Method - Procedure ... 26

Results ... 28

Discussion ... 37

Bibliography ... 44

Appendix 1 - Life Events Questionnaire ... 50

Appendix 2 – Semantic Memory Lists ... 54

List of Figures

Figure 1: Performance of children with ASD assessed as mild or moderate by CAR in the

episodic memory task- Life Events Questionnaire

(LEQ)………..35

Figure 2 : Performance of children with ASD assessed as mild or moderate by CAR in the

semantic memory task under free recall

condition………36

Figure 3. Performance of children with ASD assessed as mild or moderate by CAR in the

semantic memory task under cued recall

condition……….36

Memory in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Memory capabilities and quality of recall

in child witness testimony

The present study attempts to understand the memory capabilities and quantity of recall

in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) when compared with typically developing

children. This study examines two aspects of memory; episodic memory and semantic memory

under free recall and cued recall conditions using a personal interview and a words list paradigm

respectively. In addition, the study examines the effect of the ASD severity on memory.

The nature of memory function in individuals with ASD has been under study for

decades. While memory deficits have been found in children with ASD, the characterization of

the status of the memory abilities in children is still inadequate due to the developmental

differences that exist in autism (Williams, Golstein & Minshew, 2006). This is of consequence in

the area of child witness testimony as a number of risk factors indicate that individuals with ASD

are particularly likely to become victims or witnesses of crime (Maras & Bowler, 2012).

The first section provides an overview of ASD and the various causal theories, followed

by an account of memory and specifically episodic and semantic memory. This is followed by a

detailed review of memory functions in individuals with ASD and their implications for child

witness testimony together with a summary of the purpose and goal of the current investigation.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

The term ‘autism’ was coined by Eugen Bleuler (1916) to describe individuals with

schizophrenia who had trouble connecting with the social world. Leo Kanner (1943) in his

seminal paper ‘Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact’ published his observations of eleven

children whose condition he termed as ‘early infantile disorder’. A year later, Hans Asperger

he termed ‘autistic psychopathy’. Both Kanner and Asperger believed that the behaviour was

present from birth and had essential biological origins. Over the years research in autism has

progressed and it has come to include a family of disorders under Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD), which includes autism, Asperger’s Syndrome, Rett Syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative

Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not otherwise specified.

According to the DSM IV1, ‘The essential features of Autistic Disorder are the presence

of markedly abnormal or impaired development in social interaction and communication and a

markedly restricted repertoire of activity and interests. Manifestations of the disorder vary

greatly depending on the developmental level and chronological age of the individual. ’ Frith

(2004) has called it a ‘disorder of development’ (p.1). Autism is characterized by impairments in

three domains: reciprocal social interaction, communication, and restricted and repetitive

repertoire of behaviour and interests.

According to the WHO (2003), the prevalence of autism varies in the population

from 0.7 to 21.1 per 10,000 children while the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders is

estimated from 1 to 6 per 1000. They used the standard diagnostic handbooks and the Autism

Diagnostic Interview scores to determine the criteria for autism in the population. The incidence

of reported cases of autism has increased in recent years but this is attributed to increased

awareness and the use of wider criteria for diagnosing autism (Happe, 2004). A review of

epidemiological studies in different countries by Wing and Potter (2003) established that autism

is not limited to a particular geographical area nor is it limited to any specific social class.

Many causal factors for autism have been proposed including organic causes (Coleman &

Gillberg, 1985; Schopler & Mesibov, 1987 and C. Gillberg, 1991), and genetic causes (Rutter,

2000). The high incidence of epilepsy, ranging between 5% to 8.3 % ( Tuchman, Rapin &

Shinnar, 1991; Mouridsen, Rich, Isager, 1999; Steffenburg, Gillberg & Steffenburg, 1996; Rossi,

et. al., 1995; Wong, 1993; Tuchman & Rapin, 1997; Olsson, Steffenburg & Gillberg, 1988;

Volkmar & Nelson, 1990 and Giovanardi- Rossi, Posar & Parmeggiani, 2000) in children with

autism indicates brain damage to be a root cause of autism (Olsson et. al., 1988). Mental

handicap accompanies autism in around three quarters of people with autism, which is another

indication that autism has organic causal factors (Smalley et. al., 1988). Twin studies and sibling

studies have provided evidence for the presence of genetic causal factors in autism (Folstein &

Rutter, 1977 and Smalley, et. al., 1988). The sibling studies found that the incidence of autism is

50 times higher in siblings of people with autism than in the general population. Dizygotic twins

were found to have a lower incidence of both twins having autism than monozygotic twins in the

studies conducted by Folstein and Rutter (1977). The exact role of the genes in causing autism is

still not clear (Rutter, 2000).

Cognitive theories of autism

At the cognitive level, various theories provide an interface between the brain and

behaviour in explaining autism.

Autistic children are claimed to have impairment in the intuitive understanding of mental

states and experience a lack in attributing mental states to themselves and to others. This

attribution of mental states to themselves comes easily to other typically developing children.

This theory was tested by Baron-Cohen et. al., (1985) and is referred to as mind blindness.

Children and adults with autism have been shown to have deficits in theory of mind, which

autism therefore experience deficits in understanding pretence, irony, non- literal language and

deception.

Another cognitive theory to explain the causal basis for autism is the weak central

coherence theory. The central coherence refers to a style of information processing in which

incoming information is processed in its context. If the central coherence is strong then attention

and memory for details will suffer (Happe, 1999 and Frith, 2003). Individuals with autism have a

tendency to have a localised rather than global focus. Therefore in certain tests such as the

embedded picture task (Witkin et. al., 1971), where participants are required to locate small parts

within a global picture, individuals with autism are found to perform better than normal

individuals (Shah & Frith, 1983, 1993; Jolliffe & Baron-Cohen, 1997). This superior ability is

explained as stemming from the autistic individual’s tendency to be less influenced by the gestalt

and finding the local parts of the gestalt more salient. Another extension of this theory says that

rather than poor integration of information globally, it is enhanced discrimination of the

individual elements (Mottron et. al. 2000 and Plaisted 2001).This also explains savant abilities in

individuals with autism, which result from superior developed abilities and obsessive attention to

detail.

Executive dysfunction is another widely accepted theory for explaining some of the

behavioural problems in autism. Rigidity and perseverance are problems addressed by this theory

and it is explained by the likelihood of being stuck doing a given task set and poor initiation of

new actions (Hill & Frith, 2003). Planning, working memory, impulse control, shifting set and

the initiation and monitoring action and the inhibition of proponent responses are functions that

fall under the umbrella term of executive dysfunction. Deficits in planning have been observed in

London has been widely used tasks for evaluating executive function. Autistic children have

been found to be impaired on such tasks (Ozonoff et. al., 1991; Hughes, et. al., 1994; Ozonoff &

McEvoy, 1994 and Ozonoff & Jensen, 1999).

Memory-Episodic and Semantic

Memory plays a central part in our life as is evident from both our day-to-day and

academic life. Memory is distinguished as explicit (declarative) which refers to memories

revealed through intentional retrieval of previous experience (birth of a sibling) and implicit

(procedural) which are concerned with memories that are manifested in subsequent behaviour

without the direct recollection of a previous event (like riding a bicycle) (Balota et. al., 2000). In

this study the focus is on two specific types of explicit memory. Tulving (1972) proposed that

explicit memory could be divided into two types, episodic and semantic memory. His original

definition of episodic memory stated that it is the memory that focuses on the recall of events

from a specific time or place (Tulving, 1972). He later added that it depends on ‘autonoetic’ or

self knowing awareness in which information when retrieved successfully is experienced as a

part of one’s past and the encoding context is recalled. (Tulving, 2002 and Wheeler, Stuss &

Tulving, 1997). Tulving has also included ideas such as self and subjective time to the definition

of episodic memory. Semantic memory contains knowledge and facts relating to one’s past and

this include the knowledge of one’s identity, personal characteristics and historical facts

mediated by the awareness that the event has occurred (Levine, 2004). Semantic memory is

important for the use of language (Tulving, 1972). It consists of organized knowledge for words

and verbal symbols, their meanings and relationships between them. The semantic memory

makes retrieval of information not directly stored in it possible and this process of retrieval does

Tulving (1972) gave a taxonomic distinction between episodic and semantic memory

primarily for ease of communication rather than based on any structural or functional

differences. Subsequently different authors have advocated structural and functional distinction

between them and considered them two separate memory systems (Atkinson et. al., 1974;

Kintsch, 1975; Lockhart,Craik, & Jacoby, 1976; Tulving, 1976 and Watkins & Tulving, 1975).

The difference between episodic and semantic memory is that unlike episodic memory,

semantic memory is not dependent on time and does not require mental time travel. Tulving’s

later definition incorporated autonoetic or self-awareness of the time events occurred, in which

he likened it to mental time travel (Gardiner, 1988; Tulving, 1972, 1983, 1986 and Wheeler, et.

al., 1997).

The semantic memory system is found to be less likely to experience loss of information

and less susceptible to involuntary transformation than episodic memory system. (Tulving,

1972).

General overview of research relating to the episodic and semantic memory deficits of children

with Autism Spectrum Disorder

In the theoretical sense, child witness testimony is affected by memory deficits and hence

this section reviews the various episodic and semantic memory processes that are known to be

impaired in children with ASD.

Distinctive memory profiles have been observed in individuals with autism spectrum

disorder (ASD) with crests and troughs in their capabilities (Maras & Bowler, 2012). The role of

memory function and the classification of the significance of memory in ASD are still inadequate

due to inconsistency of findings till date. These inconsistent findings can be attributed to the

However, memory has been represented in ASD populations as an essential cognitive domain

that is responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disorder and also as secondary to a more

generalized cognitive deficit surpassing memory such as executive dysfunction (Williams,

Goldstein & Minshew, 2006).The specific difficulties with memory in individuals with ASD

have also been argued to be responsible for some of the behavioural characteristics of the

disorder (Boucher & Bowler, 2008).

Empirical research involving the memory of children with autism has found rote

memory, cued memory, associative memory, echoic and recognition memory intact in children

with autism (Ameli et. al., 1988; Bartak & Rutter,1976; Boucher, 1978; Boucher & Lewis, 1989;

Hermelin & O’Connor, 1970; Minshew & Goldstein, 1993 and Ozonoff et. al., 1991). Children

with autism have been found to have impairments in specific areas involving memory such as the

memory of recent events and the ability to remember faces and auditory and verbal skills

(Boucher & Lewis, 1989). Evidence of executive dysfunction has also been found in autism

(Bennetto, Pennington & Rogers, 1996; Hughes et al., 1994; Ozonoff et al., 1991). Fein et. al

(1996) have reported that young children with autism had less difficulties with digit recall, while

sentences were found to be difficult to recall and stories were the hardest to recall. Findings such

as these may have implications for eyewitness testimony of children and adolescents with ASD

who may be witnesses, victims or perpetrators of crime.

Boucher (1981) and Boucher and Lewis (1989) found children with autism had

difficulties in memory for events they had recently experienced and in free recall of information

when they were compared with normal age matched and mentally retarded ability matched

counterparts. This led her to conclude that in a complex stimulus, children with autism might

and Jordan (2000), adapted an early study by Boucher and Lewis (1989), which examined

memory for events in children with autism and a matched group of typically developing children.

Their research suggested that the recall of events experienced personally is particularly difficult

for children with autism. This study also revealed that children with autism recalled lesser

personal events as compared with the typically developing children who were matched controls

thus indicating that it was a specific rather than a general difficulty that children with autism

faced when required to recall personal events. Consequently it emerges from these studies that

the memories of children with autism are somewhat impaired when they have to process

information relating to self. A study (Jones, et al., 2010) of individuals with ASD concluded that

there are everyday memory deficits, which also include event based prospective memory. It also

mentions difficulties in verbal word recall. This study had 94 adolescent participants with ASD

and 55 participants without ASD. This study used Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test

(RBMT) and the Children’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test – 2 (CAVLT-2) to assess everyday

memory and standard word recall tasks respectively. This study provides emphasis on the real

world application of memory in children with ASD.

Another study on the content and structure relating to episodic memory in children with

and without Asperger’s Syndrome (Brown,2007) suggests that children with Asperger’s

syndrome provide less articulate memory narratives than their typically developed peers.Further

explaining memory deficits in adults and adolescents with ASD, research have shown that their

level of episodic memory can predict Theory of Mind impairments in adults and adolescents with

ASD. (Nogaet. al., 2009). Memory has been found connected to executive function ability in

children with ASD (Bennetto, Pennington & Rogers, 1996). These findings have been found to

reasoning in children with ASD that has not been observed in typically developing counterparts

(Toichi & Kamio, 2003).

The presence of semantic networks in children with autism originates from the research

done by O’ Connor and Hermelin (1967) and later by Tager-Flusberg (1991). Both researches

however came up with contrasting outcomes. While O’ Connor and Hermelin proposed that

children with autism are unable to encode meaningful stimuli, Tager-Flusberg, came to the

conclusion that children with autism just had a deficit in using linguistic information thereby

hampering their recall of stored information.

The presence of a semantic network for children with autism has been found with

evidence of the children using clustering strategies and category cues just as their typically

developed controls (Privett, 1995). Studies of children with autism involving both high

functioning and moderate cognitive impairments have found some evidence for the use of

memory strategy by children with autism though they tended to use it less than typically

developing children (Bebko & Ricciuti, 2000).

There has been work in the area involving both episodic and semantic memory, but this

study has involved adult participants (21-61 years) with autism spectrum disorders (Crane &

Goddard, 2008). The research consisted of first administering the Weschler’s Abbreviated Scale

of Intelligence, then the Children’s Autobiographical Memory Inventory (cited: CAMI: Bekerian

et. al., 2001) to the participants with ASD. These measures were used as a basis for an episodic

and semantic memory interview. This was followed by an Autobiographical Fluency task (cited:

Dritschel et. al., 1992) in which participants had to recall events and people from specific periods

of their life. Their findings suggest that individuals with ASD exhibit a deficit when

the control group the group of participants diagnosed with ASD showed a separate way of

remembering. The number of memories recalled by the ASD group was not affected as a

function of time whereas the control group’s memories peaked at the secondary school and the

five years post school period. This separate way of remembering is consistent with theories that

link autobiographical memory to the formation of self (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). The

lack of reminiscence has been attributed to difficulties in forming ideas of self in individuals

with ASD.

Another study on the semantic and episodic memory in children with ASD used a task

that determined recognition and self-other source memory (Lind and Bowler, 2009). Their

research showed recognition memory to have remained unaffected but source memory was

significantly reduced in children with ASD.

Free recall and cued recall in children with ASD

Retrieval and recall of information from the past is memory and there are mainly three

types of recall: free recall, cued recall and serial recall (Tulving, 1972). The present study

examines the conditions of free and cued recall. The recall process in which a person is presented

with a list of items and then asked to recall them in any order is called free recall (Bower, 2000).

The recall process in which a person is presented with a list of items that is accompanied with

cues to help with the recall of the items is known as cued recall (Bower, 2000). Both free and

cued recall has been studied in respect to the memory of children with ASD.

In a study by Tager-Flusberg (1991), children with autism were found to perform

significantly worse than their typically matched counterparts under free recall conditions where

typically developing group when they had to remember semantically unrelated words under free

recall conditions.

The free recall of pictures, written and spoken words have been found to be

impaired in children with ASD when compared with their verbal age matched typically

developing counterparts (Boucher and Warrington, 1976).As mentioned earlier, free recall of

events experienced by the self were found to be poor in children with autism (Boucher and

Lewis, 1989). In the same study when leading questions were used as cues then the performance

of the children with autism were found to be at par with their typically developing matched

group. Millward, Powell, Messer & Jordan (2000), later adapted these studies and reported

similar findings. These studies point to the presence of a decline in the amount of recall under

free recall conditions but enriched recall under cued recall conditions. Another study by

McCrory, Henry and Happe (2007); (discussed in detail in the later section) found children with

Asperger’s Syndrome when asked to use free recall to report a witnessed event had lower

remembrance of the details when compared to their typically developing peers. However their

overall accuracy and recall under guided recall conditions were found to be complete. Children

with ASD have also been reported to recall fewer details and made more errors under free recall

conditions than the typically developing counterparts (Maras and Bowler, 2011).

One explanation for the impaired free recall in individuals with autism has been

presented from the weak central coherence theory that gist representation might be impaired

while their verbatim memory stays steady (Happe and Frith, 2006). Another explanation put

forth by Bowler et. al., (2004) states that the impaired free recall and the intact cued recall may

Implication of memory in child witness testimony of children with ASD

Specific memory deficits in children with ASD put them at a disadvantage as a witness as

it diminishes their credibility as a witness (Maras & Bowler, 2012). It is therefore of great

importance to understand the memory capabilities in children with ASD.

With respect to specific studies investigating eyewitness testimony in ASD only two

studies have included children and adolescents as participants while the rest of the studies

involve adults (Maras and Bowler, 2012). Bruck et. al., (2007) investigated the extent to which

autistic children’s autobiographical memory can be distorted by suggestion. This study found

that children with ASD had difficulties recalling personal events as was reported earlier by

Millward, Powell, Messer and Jordan (2000). When compared with typically developing children

it was found that children with ASD showed deficits in recalling personal events as well as failed

to recall events completely in some instances. With regards to the dimensions of suggestibility

their research evidenced that the poor memory in children with ASD was mainly characterized

by omission errors rather than commission errors. This means that in comparison to their

typically developing counterparts children with ASD were more prone to denying that an event

has actually happened but were as prone to claiming that an event had happened when actually it

had not. This research concluded that children with ASD had a less recall of events and therefore

had poor autobiographical memory, hence bolstering the claim that children with ASD were not

more suggestible than typically developing children. The findings suggested that misinformation

leading to suggestibility was less likely to assimilate into their memory, as their autobiographical

memory was poor.

A study by McCrory, Henry & Happe (2007) explored the eyewitness memory and

that involved a live staged event and they interviewed the children the next day regarding the

event. The interviewer used a structured protocol and the children were given a free recall, then

they were asked a few general questions followed by specific questions. The interview ended

with the interviewer asking leading questions that entailed incorrect assumption. The AS group

performed worse than their typically developing counterparts on the free recall. However, no

significant differences were found between the AS group and the typically developing group in

the general and specific questioning or their performance on the leading questions. In addition,

the children were given two executive function tasks, Hayling Sentence Completion Test and

Fluency task. The results indicated deficits in response suppression in the AS group while no

group differences were found in the Fluency task. Their findings show that free recall

underestimates the memory for an event in individuals with AS while general and specific

questioning can elicit more information than free recall. In line with the findings of Bruck et. al.

(2007), this study found that children with AS were found to be no more suggestible than their

typically developing counterparts. The correlation found between executive function and

memory in AS has been used to explain that individuals with autism rely more on generic

cognitive resources during recall due to their weak central coherence.

Barring these studies involving children with AS and ASD as participants most other

studies have included adult participants. The findings by McCrory, Henry & Happe (2007) and

Bruck et. al., (2007) that children with ASD were no less suggestible than their typically

developing counterparts has been found to hold true in an adult ASD population in a study by

North et. al., (2007). In another study Maras and Bowler (2011) found that high functioning

individuals with ASD used schemas to aid their memory as much as the typically developing

was found to recall fewer details and reported to have made more errors than their typically

developing counterparts.

From the work in the field of eyewitness testimony done till date with high functioning

individuals with ASD it can be concluded that they are capable of providing reliable eyewitness

testimony. However, it must be noted that all the studies have involved high functioning

individuals with ASD and hence it may not be generalizable to the entire ASD population. This

is discussed in detail in the next section.

Relevance of the study

Memory in autism has been under study for decades. The purpose of the current

study was to assess the capability and quality of recall in children with Autism Spectrum

Disorder (ASD) when compared with typically developing children. As mentioned earlier,

almost all the memory studies that have involved individuals with ASD have involved relatively

high functioning participants (see review, Maras and Bowler, 2012). Therefore the research

needs to be extended to include low functioning individuals with ASD.

It has been widely accepted that the majority of people who meet the criteria for autism

also meet the criteria for mental retardation (APA, 1994 and NRC, 2001). Intellectual disability

has further damaging effects on memory (Lifshitz et. al., 2011), and therefore as individuals with

ASD with added intellectual disability can have more trouble with remembering details and

temporal order of events which as mentioned earlier is very important in case of eye-witness

testimony (Maras and Bowler, 2012). Individuals with more severe ASD have also been

observed to have delays and impairments in language development (Boucher et. al., 2008) and

The present study was carried out in India. The evaluation of previous research on

memory and autism presents that while a lot of research involving various aspects of memory in

individuals with autism have been done, most of this research has almost entirely been carried

out in Europe and America. As such there is no data on the various memory profiles in autistic

individuals available on this topic from developing countries. A cross-cultural interpretation will

be very useful in analysing the extent of the applicability of common principles across countries

and cultures. Having a dataset from a developing country will enable multi national comparisons

and the opportunity to explore more research options in the future involving cross-cultural

perspective of memory in autistic individuals. It is generally accepted that there is a difference in

the education system and the support network between western countries and developing nations

with regards to children and more specifically where children with disability are concerned, this

might also be a factor in the differences in their memory.

Research questions and hypothesis

The present study attempts to answer two questions: what is the quantity of recall in the episodic

memory task and semantic memory task under free and cued recall conditions in children with

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as compared with typically developing children? And does

severity of the symptoms of ASD have an effect on the recall capabilities of children with ASD?

The present study proposes to test the following hypotheses (H):

H1: Children with ASD will perform worse on the episodic memory task than typically

developing children; furthermore, this difference is predicted to be significant for semantic

H2: The severity of ASD symptoms as assessed using the Childhood Autism Rating Scale

(CARS) will have a negative effect on the performance in the episodic memory task and the

semantic memory tasks under free and cued recall conditions.

Method

In order to address the above hypotheses, data analysis was performed on a series of

memory tasks performed by a group of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and a

control group of typically developing children.

Participants

The participants consisted of 20 typically developing children and 19 children with

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). In the typically developing group there were 8 males and 12

females and in the ASD group there were 15 males and 4 females. Epidemiological studies have

shown that the incidence of autism is higher in males than females. The sex ratio has been found

to vary from 2:1 (Ciadella & Mamelle, 1989) to about 3:1 (Steffenburg & Gillberg, 1986). It has

been found to vary with respect to ability too, with females more likely to be at the lower end of

the autism spectrum while males are more likely to be at the higher end of the spectrum (Lord &

Schopler, 1987).As the sample was collected using convenience sampling 2 the participants were

not matched for gender. All the 20 typically developing children in the control group were

enrolled in Grade 1 to 4 of the Indian primary education system. The 19 children with Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD) were enrolled in Grade 1 to 4 in special education schools in India. An

examination of the school records showed that all the children in the ASD group were given a

formal diagnosis by a qualified clinician according to current diagnostic criteria; DSM – IV

(APA, 1994) and ICD- 10 (WHO, 1993). In the ASD group, 2 children were diagnosed with

Asperger’s Syndrome, 15 children were diagnosed with Autism and 2 children were diagnosed

with Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PD- NOS). In the ASD

group, 18 children were verbal while 1 child was non-verbal. However, the non-verbal children

were able to communicate by writing. The same instructions were provided to the non-verbal

child as the verbal children and he responded with his answers in writing. In order to avoid

comorbidity, children with ASD who received an additional diagnosis of mental retardation from

the clinical psychologist were not included. The present study included children with ASD who

have received an assessment of mild, moderate or severe ASD symptoms (as assessed by the

Childhood Autism Rating Scale).

The mean age of the participants in the typically developing group was 7.46 years (SD =

1.74). The mean age of the participants in the ASD group was 12.00 years (SD = 2.35). The age

range for the typically group was from 5.02 to 10.11 years and the age range for the ASD group

was from 7 to 14.11 years. Participants did not differ by gender on age. The two groups of

children were closely matched on verbal age as a group. On an individual level, they were

relatively matched though not perfectly matched. In the typically developing group, the

participant’s mean verbal comprehension age was 7.36 years (S.D = 2.19) and in the ASD group,

the participant’s mean verbal comprehension age was 7.37 years (S.D = 1.94). The verbal

comprehension age range for the typically group was from 4.11 to 12 years and the age range for

the ASD group was from 5.06 to 12 years.

The participants were recruited through contact with the schools, which in turn

contacted the parents. Parental consent was taken for all children. All the participants in the

language of instruction for all the children was English. All the children in the study were

bilingual and spoke English in addition to their mother tongue.

Measures

The present study used four measures. The Test for Reception of Grammar – 2 (TROG –

2) was used for both the groups of children. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) was

administered to the parents of the children with ASD to assess the severity of the autism. Both

groups of children were administered the ‘Life Events Questionnaire’ and the semantic memory

tasks under free and cued recall conditions. A brief description of all the measures is provided

below.

Test for Reception of Grammar – 2 (TROG- 2): Dorothy Bishop first developed The TROG in

1983. The revised version TROG – 2 (2003) is currently in use. The TROG – 2 assesses

grammatical ability by measuring the understanding of twenty constructions four times each

using different test stimuli. The test is individually administered and is presented in a four picture

multiple-choice format consisting of lexical and grammatical foils in English. The test provides a

comparison of the child’s comprehension in relation to his or her peer group and also provides a

qualitative assessment of specific areas of grammatical difficulty.

The test is suitable for administration to children in the age group of 4 to 12 years. In

addition, it can also be used for older children and adults with specific impairments and for them

the norms for children in the 12-year age group are applicable. The total test time varies between

10 – 20 minutes.

Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS): The CARS is a behaviour rating scale intended for use

in diagnosing the severity of autism (DiLalla and Rogers, 1994). It is used to provide additional

2011). Eric Schopler, Robert J. Reicher & Barbara R. Renner originally developed the CARS in

1986. The revised version CARS – 2 was used in the present study. It retains the original

Childhood Autism Rating Scale (renamed CARS – 2) and consists of 15 item rating scales to be

completed by the practitioner and a parent/care-giver. It also includes an additional rating scale

to make it more sensitive to detecting symptoms of ASD in children and adults with high

functioning autism and Asperger’s. The 15 items in the CARS – 2 address 15 functional areas

(Schopler, Bourgondien, Wellman & Love, 2010).

The Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ)3: The Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ) has been adapted

from the autobiographical memory4 questionnaire developed by Bruck et. al., (2007) for their

study. The LEQ was used as a measure of episodic memory in both groups of children. This

questionnaire has been used previously with both typically developing children and children with

ASD to assess autobiographical memory. The questionnaire was pilot tested by Bruck et. al.,

(2007) before administration on a small group of typically developing and a set of children with

ASD and found to be appropriate and was administered to 38 typically developing children and

30 children with ASD for their study to assess the children’s autobiographical memory. The

LEQ was also pilot-tested for the present study in a small group of typically developing children

in India to ensure that the vocabulary level and content was appropriate for administration to the

children. A few adjustments were made accordingly. For example, questions such as “How old is

your mother/father?” were dropped, as around 90% of the children were unable to answer the

question. The LEQ consists of three sections; Section 1 asks about Personal Information such as

name, age, parent’s information, etc.; Section 2 asks about School Information such as name of

school, teacher, classmates, etc., and Section 3 asks the child two open ended questions, what

3 Refer to Appendix 1 for the Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ)

they remember about their first day in school and what was their favourite holiday. Each section

measures the child’s recollection of facts about their life and events experienced personally by

the child such as a holiday they went for and the amount of details concerning the same. Every

correct answer in Section 1 and 2 get a score of 1 and every wrong answer gets scored 0. Section

3 was coded by giving a score of 1 per unique information recalled in both the questions. For

example; in the question about their favourite holiday the child was given a score of 1 for

answering where they went, and a point each for where they stayed, what they did, what places

they visited and so on. The total score were counted and recorded.

The Semantic MemoryTasks5: The Semantic Memory Tasks have been adapted from the

experimental design of Perner and Ruffman (1995). They have used these memory tasks

previously in their study to test the free and cued recall in young typically developing children

using list of words. The list of words from Perner and Ruffman’s (1995) study was pilot tested

on a sub set of typically developing children in India. Certain objects were changed to adapt

them to the Indian context. For example: in the musical instruments category, piano was replaced

by harmonium to make it more suitable to the Indian context.

The semantic memory tasks consist of a memory task involving pictures of familiar

objects or animals belonging to the same category. The tasks test for both free recall and cued

recall. In the first condition, the child was randomly presented with eight pictures belonging to

eight unrelated categories and then asked to recall the objects they were just shown. This was for

the purpose of assessing the performance under free recall condition. In the second condition, the

child was presented with eight pictures that are randomly presented but belonged to certain

categories and the instructions clearly mentioned that they would be presented with items

belonging to a certain category. This condition was for the purpose of assessing the child’s

performance under the cued recall conditions to distinct categories (for example; modes of

transport or type of fruits etc.). The objective of the test was to determine whether children

recalled more in the free recall condition or the cued recall condition. A score of 1 was given for

each correct recall. The total number of correct recalls were counted and recorded.

Procedure

The study had the approval of the University of Cambridge Ethics Committee. Parents of

children in both the typically developing group and the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) group

were informed of the study through the participating schools. All tests were administered as

individual sessions in paper and pen booklets.

In both groups, the Test for Reception of Grammar – II (TROG II) was administered first,

followed by the Life Event Questionnaire and the Semantic Memory Task; together these

measures took approximately 30 – 45 minutes to complete. In both the groups, the responses

given by the child on the Life Event Questionnaire was verified with the parent. In the ASD

group, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale - 2 (CARS 2) was also administered to the parent to

assess the severity of the autism symptoms.

Results

Variable and Sample Descriptive: The present study had 39 participants of which 19 were in the

Autism Spectrum Disorder group (ASD) and 20 were in the control group which consisted of

Descriptive Statistics

____________________________________________________________________________ Group N Mean S. D.

____________________________________________________________________

Autism Spectrum Disorder 19

Age 12 2.35

Verbal Comprehension Age 7.37 1.94

Typically Developing Children 20

Age 7.46 1.74

Verbal Comprehension Age 7.36 2.19

_____________________________________________________________________

Table 1

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations for the chronological age and the verbal

comprehension age scores, presented separately for the children with ASD and the control group

of typically developing children.

The mean chronological age of the ASD group was 12 years (S.D = 2.35) while the mean

chronological age of the control group was 7.46 years (S.D = 1.74). The age range for the ASD

group was between 7 to 14.11 years and the age range for the control group was between 5.02 to

10.11 years

Both groups of children were matched as a group based on their verbal comprehension,

which was assessed using the Test for Reception of Grammar-2 (TROG-2). At an individual

level, they were relatively matched though not perfectly matched. The mean verbal

comprehension age for the ASD group was 7.37 years (S.D. = 1.94) while the mean verbal

age range for the ASD group was from 5.06 to 12 years and the age range for the typically group

was from 4.11 to 12 years.

The ASD group was also assessed using the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS).

The mean score on CARS was 33.73 (S.D. = 1.69). The CARS score ranged from 31 to 39.

Preliminary Analyses:

An examination of the minimum and the maximum values revealed no mis-entered data.

Histograms with normal curves were generated for each of the individual variables. These

histograms were visually examined and were roughly normally distributed except for the age

variable. The age variable of the children with ASD was the only variable for which the values of

skewness reached -1.055 and the subsequent verbal comprehension age had a skewness of 1.065.

Their kurtosis was .085 and .254 respectively meaning that the distribution of age and TROG-2

verbal comprehension age scores were platykurtic.

For each variable box plots were generated in order to spot potential univariate outliers.

No univariate outliers were identified for any of the variables. Assumption checks were carried

for all the variables and all assumptions were met except the assumption for homogeneity of

variables in the cued recall condition where equal variance was not assumed.

In order to test the hypotheses, statistical analysis was carried out in the following order.

Descriptive statistics was used to report the sample means. The variables under study were the

age, verbal comprehension age, performance on the Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ), the free

recall task and the cued recall task. The first statistics to be used was bivariate correlation, which

was carried out to test the relationship between the variables. Then a t test was carried out to test

Correlations

To determine whether the memory tasks correlated with the verbal comprehension

age, correlations between the various memory tasks were examined for both children with

ASD and typically developing children with bivariate correlation (Table 2 & 3).

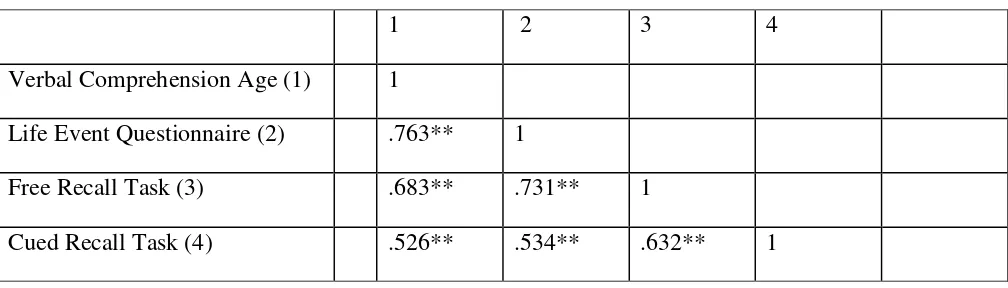

Bivariate correlations Between All Variables in the Autism Spectrum Disorder Group

Tasks. P <. 05*, P < .01 **.

Table 2

Bivariate correlations Between All Variables in the Typically Developing Group

Tasks. P <. 05*, P < .01 **.

Table 3

Table 2 shows the correlations between the variables in typically developing children.

The verbal comprehension age was highly correlated with the LEQ, free and cued recall task

with s(r=.69, p<.01), (r=.57, p<.01) and (r=.63, p<0.01) respectively.

1 2 3 4

Verbal Comprehension Age (1) 1

Life Event Questionnaire (2) .693** 1

Free Recall Task (3) .572** .789** 1

Cued Recall Task (4) .631** .709** .638** 1

1 2 3 4

Verbal Comprehension Age (1) 1

Life Event Questionnaire (2) .763** 1

Free Recall Task (3) .683** .731** 1

Table 3 shows the correlations between the variables in children with ASD. The verbal

comprehension age was highly correlated with the LEQ, free and cued recall task (r=.76, p<.01),

(r=.68, p<.01) and (r=.52, p<0.01) respectively.

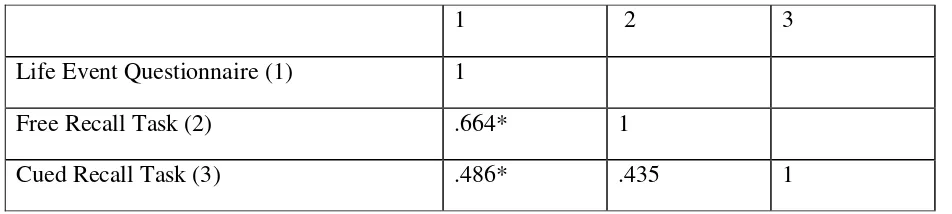

Partial Correlations Between Variables in the Autism Spectrum Disorder Group

Tasks. P <. 05*, P < .01 **.

Table 4

Partial Correlations Between Variables in the Typically Developing Group

Tasks. P <. 05*, P < .01 **.

Table 5

Table 4 shows the partial correlations between the performances on the memory tasks in the

ASD group. The verbal comprehension age was controlled. The life event questionnaire (LEQ)

had a moderate correlation with semantic memory under free recall condition and a low

correlation under the cued recall conditions (r=.44, p > .05) and (r=.24, p > .05) respectively.

They results were not significant.

1 2 3

Life Event Questionnaire (1) 1

Free Recall Task (2) .445 1

Cued Recall Task (3) .242 .440 1

1 2 3

Life Event Questionnaire (1) 1

Free Recall Task (2) .664* 1

Table 5 shows the partial correlations between the performances on the memory tasks in

the typically developing group. The verbal comprehension age was controlled. The life event

questionnaire (LEQ) has a high correlation with semantic memory under free recall condition

and a moderate correlation with the semantic memory task under cued recall conditions (r=.66, p

< .05) and (r=.48, p < .05) respectively.

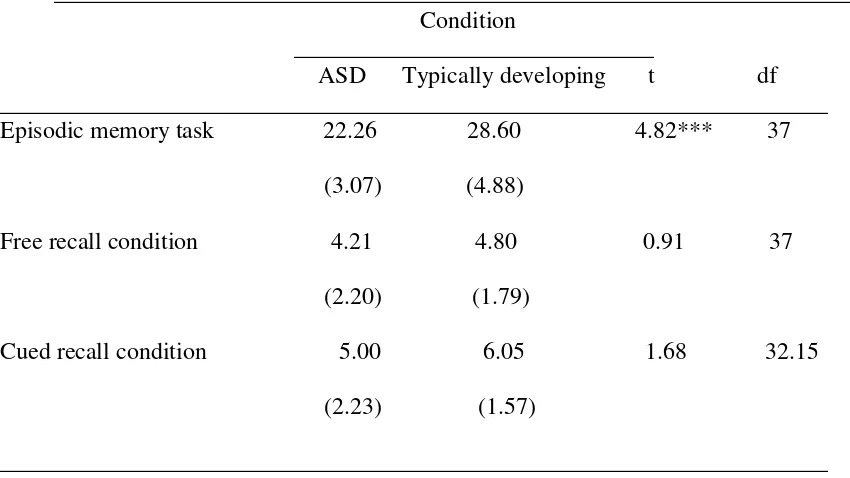

Results for H1:

The first hypothesis under study states that children with ASD will perform worse on the

episodic memory task than typically developing children; furthermore, this difference is

predicted to be significant for the semantic memory task under both free and cued recall

conditions. An independent sample t test was conducted to first compare the performance in

episodic memory tasks of children with ASD and typically developing children (Table 6).There

was a significant difference in the performance of episodic memory task scores for children with

ASD (M=22.26, S.D=3.07) and typically developing children (M=28.60, S.D = 4.88); t (37) =

4.82, p = 0.000, d = 1, 95% CI [3.67, 8.99]. The results clearly show that there is difference in

the performance of the episodic memory task by children with ASD when compared to typically

developing children. Children with ASD have been observed to perform worse than typically

developing children in the episodic memory task.

In order to further test the hypotheses for the free recall condition, an independent sample

t test was conducted to compare the performance in free recall memory task in children with

ASD and typically developing children (Table 6). An equal variances t test failed to reveal a

statistically reliable difference between the performance in the free recall condition for children

with ASD (M= 4.21, S.D=2.20) and typically developing children (M=4.80, S.D = 1.79); t (37) =

The values of skewness for the free recall condition was 0.053, which were moderately

skewed, and the kurtosis was -0.596 meaning that the scores were platykurtic. Therefore this did

not affect the results. The effect size reported is also small. Thus the results indicate that there

are no significant difference in the performance in free recall conditions between children with

ASD and typically developing children. This part of the hypotheses is thus not supported by the

findings.

Performance on the episodic memory and free recall and cued recall conditions in children with ASD and typically developing children

_____________________________________________________________________ Condition

______________________________

ASD Typically developing t df _____________________________________________________________________

Episodic memory task 22.26 28.60 4.82*** 37

(3.07) (4.88)

Free recall condition 4.21 4.80 0.91 37

(2.20) (1.79)

Cued recall condition 5.00 6.05 1.68 32.15

(2.23) (1.57)

_____________________________________________________________________

Note. * = p ≤ .0.05, *** = p ≤ 0.001. Standard deviations appear in parentheses below means.

Table 6

The hypothesis further predicted a significant difference between the performance in the

cued recall condition in children with ASD and typically developing children and therefore

children with ASD will perform worse than typically developing children. An independent

sample t test was conducted to compare the performance in cued recall memory task in children

significant difference was observed in children with ASD (M = 5.00, S.D = 2.23) and typically

developing children (M = 6.05, S.D = 1.57); t (32.15) = 1.68, p = 0.101, d = .50, 95% CI [-0.21,

2.31]. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (F = 4.61, p = 0.03), so degrees of freedom were

adjusted from 37 to 32.15. To provide more stable measures, Z scores were computed for raw

scores in the cued recall condition scores in the dataset. The z scores did not reveal any

significant outliers. This may slightly account for the non-significant results. The effect size

reported is medium. Thus the results indicate that there are no significant difference in the

performance in cued recall conditions between children with ASD and typically developing

children.

Results for H2:

The fourth hypothesis under study was that the severity of ASD symptoms as assessed

using the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) would have an effect on the performance in

the episodic memory task and the semantic memory task under free and cued recall conditions.

An independent sample t test was conducted to test how the severity of ASD (mild and moderate

CARS score) affected the performance in the episodic memory task and the free and cued recall

task (Table 7). In the episodic memory task, there was a significant difference in the performance

of ASD children diagnosed according to their CARS score as mild (M=25, S.D=2.00) and

moderate (M=20.66, S.D = 2.38); t (17) = 4.03, p = 0.001, d = 0.96, 95% CI [2.06, 6.59]. The

results indicate that children diagnosed as moderately autistic according to CARS were found to

perform worse in the episodic memory task than children diagnosed as mildly autistic.

In the free recall condition, there was a significant difference in the performance of the

ASD children diagnosed according to their CARS score as mild (M=6.00, S.D=2.44) and

test indicated unequal variances (F = 6.94, p = 0.01), so degrees of freedom were adjusted from

17 to 7.69. The results indicate that children diagnosed as moderately autistic according to CARS

were found to perform worse in the free recall task than children diagnosed as mildly autistic.

Effect of severity of autism on performance in the episodic memory and free recall and cued recall conditions

_____________________________________________________________________ Condition

______________________________ Mild Moderate t df

_____________________________________________________________________ Episodic memory task 25 20.66 4.03*** 17

(2) (2.38)

Free recall task 6 3.16 2.86* 7.69

(2.44) (1.19)

Cued recall 6.42 4.16 2.38* 17

(1.90) (2.03)

_____________________________________________________________________

Note. * = p ≤ .0.05, *** = p ≤ 0.001. Standard deviations appear in parentheses below means.

Table 7

In the cued recall condition, there was a significant difference in the performance of the

ASD children diagnosed according to their CARS score as mild (M = 6.42, S.D = 1.90) and

moderate (M = 4.16, S.D = 2.03); t (17) = 2.38, p = .029, d = 0.61, 95% CI [0.26, 4.25]. The

results indicate that children diagnosed as moderately autistic according to CARS were found to

perform worse in the free recall task than children diagnosed as mildly autistic.

The results thus show that the severity of autism as assessed by CARS has an adverse

children diagnosed as mildly autistic performing better than children diagnosed as moderately

autistic. Figure 1, 2 and 3 illustrates the results, there is a decline in the performance in the

episodic memory task (LEQ) and the semantic memory tasks under free and cued recall in

children diagnosed as more severe.

Performance of children with ASD assessed as mild or moderate by CARS

in the episodic memory task- Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ).

Performance of children with ASD assessed as mild or moderate by CARS

in the semantic memory task under free recall condition.

Figure 2

Performance of children with ASD assessed as mild or moderate by CARS

in the semantic memory task under cued recall condition

Discussion

The investigation of the results of the research provides partial support to the first

hypotheses, children with ASD did perform worse than the typically developing counterparts in

the episodic memory task. However, children with ASD were found to perform relatively on par

with their typically developing counterparts in the semantic memory tasks under both free and

cued recall conditions. The results support the second hypothesis that the severity of autism has

an effect on the performance in the episodic memory task and the semantic memory task under

both free and cued recall conditions. These findings provide the opportunity for some interesting

interpretations and possibilities as this study included children from the low functioning end of

the autism spectrum.

The initial findings from the first hypothesis are consistent with previous research

findings about the presence of a personal episodic memory deficit in children with autism.

(Millward, Powell, Messer & Jordan, 2000; Bruck et. al., 2007 and McCrory, Henry & Happe,

2007). In the episodic memory task, children with autism recalled significantly less details when

compared to their typically developing counterparts as assessed using the Life Events

Questionnaire (LEQ). In the LEQ, the performance of the children with ASD in the first two

sections of the questionnaire relating to Personal and School Information were found to be

somewhat better than their performance in the open ended questions relating to events

experienced in their life. These findings are consistent with previous research that has found the

memory for facts, percepts and skills to be intact in individuals with ASD (Ben Shalom, 2003and

Bowler, Gaigg & Lind, 2011). The facts relating to the ASD individuals life such as name of the

parents, the name of the school etc. are also information that are taught to the child and is

research has shown rote memory is relatively unimpaired in individuals with ASD (Ameli et. al.,

1988). As mentioned earlier, the memory for personally experienced events is poor in individuals

with ASD, which may be responsible for the poor performance on the episodic memory task.

Also events like the first day of school or a holiday are likely to elicit emotions. For example the

first day at school can be either exciting or upsetting as has been reported in the responses of the

typically growing children. However most of the children with ASD did not provide any details.

Individuals with ASD have been shown to have deficits when processing emotional stimuli

(Norbury et. al., 2009 and Spezio et. al., 2007) unlike in typically developing individuals where

emotionally arousing events are better remembered and less prone to forgetting than

non-emotional events (Bradley, et.al., 1992; Burke et. al., 1992; Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Heuer &

Reisberg, 1990 and Kessinger & Corkin 2003). Such emotion arousing events also require the

encoding of complex stimuli such as social interaction, and children with ASD have been found

to encode less information in such a situation (Boucher, 1981and Boucher & Lewis

1989).Another explanation is provided by the research regarding linguistic deficits

(Tager-Flusberg, 1991) and difficulties in processing information by children with ASD (Bowler et. al.,

2011 and Gaigg et. al., 2008), which may hamper their recall. This may have contributed to the

poor performance in the episodic memory task by the children with ASD.

However, the latter part of the hypothesis was rejected as the children with ASD were

found to perform more or less on par with the typically developing group of children in the

semantic memory task involving free and cued recall. The relatively similar performance of the

children with ASD with the typically developing children on the semantic memory tasks under

free recall conditions is inconsistent with previous findings, which report a decline in the amount

McCrory, Henry & Happe, 2007 and Maras & Bowler, 2011). One possible explanation for these

findings may be attributed to both the children with ASD and the typically developing children

having the same level of verbal comprehension. It must be noted that the children with ASD

were older than the typically developing children in their chronological age. And as the results

indicate when the verbal age was controlled then the correlations relating to the performance in

the episodic memory tasks and the semantic memory tasks under both the free and cued recall

conditions decreased in the children with ASD and the typically developing children.

The children with ASD were also found to perform on par with the typically

developing counterparts on the semantic memory task under cued recall condition. This is

consistent with previous research, which states that cued recall is more or less intact in children

with ASD (Bartak & Rutter, 1976; Boucher, 1978; Boucher & Lewis, 1989). A majority of the

children in the ASD group were found to have employed categorical cues to remember the

pictures as they recalled the words in clusters, in the same way as the typically developing

children. Previous research has reported the use of category cues by children with ASD (Privett,

1995). This could account for the on par performance of the children with ASD with their

typically developing counterparts. The organization of the objects presented into categories

provided the child with cues to recall them later. As in the case of the performance in the free

recall condition, the matched verbal comprehension age may also account for the similar

performance in the semantic memory task under cued recall condition between children with

ASD and their typically developing counterparts.

Another possible explanation for the findings may be attributed to the fact that the

semantic memory task had pictures of neutral objects and hence these pictures did not elicit any

children with ASD to remember. As the semantic memory task did not elicit any overwhelming

emotions in the child, the child was able to remember the objects and subsequently recall them

better.

In terms of the overall finding of the first hypothesis which reported poor performance in

the episodic memory task and better performance on the semantic memory tasks under free and

cued recall conditions, one possible explanation can be that children with ASD could not

perform better as they were required to provide information that related to their self in the

episodic memory task. Previous research has shown that children with ASD have a deficit in

reporting experience that involves their selves (Lind & Bowler, 2008).On the other hand, in the

semantic memory tasks; they did not have to include themselves in the task in any way. Hence

their performance was same as their typically developing counterparts.

According to the WHO (2003), the prevalence of autism varies in the population from 0.7

to 21.1 per 10,000 children while the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders is estimated from

1 to 6 per 1000. This makes them susceptible to risk factors that lead them to be represented in

the criminal justice system as witnesses, victims or perpetrators of crimes. Moreover, autism is

characterised by impairments in social interaction, communication and a rigid repertoire of

behaviour, which can make them prone to social naivety and reduce their insight into the thought

processes of others.

The implications of these findings in terms of child witness testimony are interesting.

While the semantic memory for items under free and cued recall have been found to be more or

less on par with the typically developing group of children, the episodic memory have been

found to be worse in children with ASD. If the episodic memory is impaired, then theoretically it

Bowler, 2012). This is noteworthy, as the results would suggest that children with ASD might be

unable to provide a reliable account of the events with details due to their episodic memory

deficits. However, the findings suggest that they may be relied on to provide information if they

are not directly involved in the event. Children with ASD have developmental differences and

this may account for the findings.

These findings lead us to consider the second hypothesis. The hypothesis states that the

severity of autism will have an effect on the performance in the episodic memory task and

semantic memory task under free and cued recall. The findings support this hypothesis and child

diagnosed as more severe in the ASD spectrum have been found to perform worse than the

children who have been diagnosed as having milder ASD symptoms. Individuals with ASD who

have accompanying intellectual disability have been reported to have wider difficulties with

memory on top of their regular memory deficits (Boucher et. al., 2008).

In terms of child eyewitness testimony this might have implications, as it would be

advisable to assess the severity of the autism symptoms in the individual while assessing their

suitability as an eyewitness. This is an exploratory study and there are no known studies

regarding the effect of the severity of ASD on memory and their implication in child witness

testimony. Though the findings from this study are not reflective of the entire ASD population

yet it is an important finding and will helpful for future research in this direction. It is noteworthy

that while the results regarding the performance on the episodic memory task and the semantic

memory task under cued recall was in line with previous research, the results regarding the

performance on the semantic memory task under free recall were different from previous

findings. This reflects possible implications for the validity of extrapolating findings from

This study has certain limitations. First, it would have strengthened the experimental

design to have a staged event paradigm, as that would have provided for stronger ecological

validity. However the same was not possible in the present study as it was done on a small scale

and had limitation of time. Second, children with ASD who get a diagnosis of severity are mostly

non-verbal and that can pose a challenge for assessing their memory. The present study had only

one participant who was non-verbal but he was able to communicate through writing. There is a

need to include more non-verbal participants. This study focused on the immediate recall in the

semantic memory tasks, and it will be interesting to study the effect of time on the recall.

However, it is stressed that this was an exploratory study. As such though the findings

may not be generalizable to the entire population, it still provides some interesting results.

Moreover, this study also studied the effect of the severity of ASD on recall. As mentioned

earlier, the effect of the severity of recall on memory has not been explored before in terms of

child witness testimony (see review, Maras & Bowler, 2012). Therefore this study provides an

interesting insight into the effect of severity of symptoms of ASD on memory. This study can

contribute to the gap in the literature in the area of the effect of the severity of the symptoms of

ASD on memory. In addition, this study was carried out in India. This will provide the

opportunity for multi-national comparisons.

Future research with a low-functioning group of individuals with an experimental

paradigm of staged event will be able to provide an even better insight into the memory of

children with ASD and their ability to be considered as a witness. It will also be interesting to

have a cross-cultural study to understand the applicability of principles of memory across