TEL AVIV 2017

Salvage Excavation Reports

No. 10

Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology Tel Aviv University

Editor:

Efrat Bocher

Authors:

Hai Ashkenazi, Gil Breger, Amir Cohen Klonymus, Shay Dov Glibter,

Meir Edrey, Itai Elad, Yoav Farhi, Nissim Golding-Meir, Boaz Gross,

Mark Iserlis, Assaf Kleiman, Inbar Ktalav, Neer Lect Ben Ami, Yossi Nagar,

Assaf Nativ, Lidar Sapir-Hen, Alon Shavit, Ron Shimelmiz, Assaf

Yasur-Landau, Elisabeth Yehuda and Hagi E. Yohanan

ISSN 1565-5407

©

Copyright 2017

All rights reserved

SALVAGE EXCAVATION REPORTS

NUMBER 10

Editorial Board

Publications Director Scientific Editor Graphic Designer

Oded Lipschits Ze’ev Herzog Moshe Fischer

v

C O N T E N T S

Foreword

viiChapter

1

: Ard el-Samra: A Chacolithic, Early Bronze and

Intermediate Bronze Age Site on the Akko Plain

Assaf Nativ, Ron Shimelmiz, Lidar Sapir-Hen, Inbar Ktalav and Mark Iserlis 1

Appendix

1

: Basket list, Area Z

56Appendix

2

: Basket list, Area K

63Appendix

3

: List of loci and features, Area Z

67Appendix

4

: List of loci and features, Area K

69Chapter

2: A

Byzantine Aqueduct and Road Near Um el-Amad West

(Gideona) – Jezreel Valley

Hai Ashkenazi 73

Chapter

3: H

arish (East): Agricultural Features

Boaz Gross 81

Chapter

4

: Tel Malot

Alon Shavit 89

Chapter

5

: Nahalat Yehuda

Gil Breger 103

Chapter

6

: A Burial Cave Complex at Ras Abu Dahud

Neer Lect Ben Ami and Hagi E. Yohanan (With contribution by Kim Legziel) 107

Chapter

7

: Six Salvage Excavations at Ramat Bet Shemesh

Nissim Golding-Meir, Itai Elad, Boaz Gross and Assaf Kleiman (With contribution by Y. Farhi) 125

Chapter

8: H

orvat Akhbar

Nissim Golding-Meir and Shay Dov Glibter (With contribution by Y. Farhi and O. Ackerman) 141

Chapter

9

: Agricultural Installations in Western Ramat Beit Shemesh

Meir Edrey 153

Chapter

10: H

orvat

>

Alin (North)

Boaz Gross 161

Chapter

11

: Kever Dan

vi

Chapter

12

: A Salvage Excavation at Tzelafon

Boaz Gross 171

Chapter

13

: Gizo North: Winepress and a Cave

Hai Ashkenazi 179

Chapter

14: H

orvat Titora (West) and Hirbet Abu Freij (North-West)

Assaf Yasur-Landau 183

Chapter

15

: A Mamluk Period Cemetery at Beit Dagan

Meir Edrey and Yossi Nagar 189

Chapter

16

: Salvage Excavations along Highway

1

Nissim Golding-Meir and Amir Cohen Klonymus 195

Appendix

1

: The Coins from Highway

1

Yoav Farhi 243

Chapter

17

: Khirbat

H

arsis (North)

Gil Breger 247

Chapter

18: H

urvat el-Za

>

atar

Hai Ashkenazi 251

Chapter

19

: A Stone Quarry in Arnona, Jerusalem

Meir Edrey 259

Chapter

20:

>

En

H

emed

vii

FOREWORD

It is no simple challenge to bring together the work of dozens of excavators of over 20 diverse

salvage excavation sites and weave their ield work and analyses into a uniied report. Yet here,

after long and concerted effort by a wonderful

team, we are proudly able to presentreports of 20

salvage excavations from different periods, from different parts of the country, and from both rural and urban areas, all between the covers of one

volume —all conducted under the auspices of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University and the Israeli Institute of Archaeology and

Ramot Archaeology. Most of the reports were

written by the excavators themselves; a small number were written by researchers of the

Institute of Archaeology.

I extend my gratitude to the director of the

Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, Prof. Oded Lipschits.He recognized the importance of this volume in the Salvage Excavation Reports

Series and spared no effort, despite the dificulties involved, and provided us access to all the Institute’s technical and intellectual facilities. I also wish to thank Nirit Kedem, the administrative director of the Institute, who helped in every way possible to promote the project.

I thank Dr. Alon Shavit, head of the Israeli institute of Archaeology, for supporting the excavations and the very complicated publication and his staff, Efrat

Ashraf, director of budgets and manpower, and Boaz Gross, head of Qardom- Archeological Excavations,

for all their support and assistance from the outset

of the project.

Processing of the material and preparation

for publication of the inal report was done in the

laboratories of the Institute of Archaeology of

Tel Aviv University. Restoration of the ceramic material was done by Yait Wiener and Shimrit Salem. The inds, including pottery, stones, glass and metal, were drawn by Yulia Gottlieb, Itamar Ben-Ezra, Ada Perry and Na’ama Earon. Plates were arranged by Yulia Gottlieb. Maps and plans were produced for publication by Ami Brauner, Shatil Emmanuilov, Itamar Ben-Ezra and Noa Evron. All Photographs of the artifacts were taken and processed for publication by Pavel Shrago.

The scientiic content of the manuscript was carefully edited by Dr.Meir Edrey, Prof.Ze'ev

Herzog and Prof.Moshe Fischer.

Finally I wish to thank Myrna Pollak, director of publications of the Institute, for the English editing

of the manuscript and supervision of editing and

production throughout all stages. Noa Evron is responsible for the attractive graphic layout. Their efforts are gratefully acknowledged.

C H A P T ER 15

A M A M L U K P E R I O D C E M E T E R Y AT B E I T D A G A N

Meir Edrey and Yossi Nagar

As a result of the exposure of human remains during unauthorized sand mining activity, a salvage excavation was undertaken at HaHavazelet Street in Beit Dagan (License No. B-338/2009) in July, 2009. The excavation was directed by M. Edrey on behalf of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of

Archaeology of Tel Aviv University and inanced

by the Israel Land Administration.1

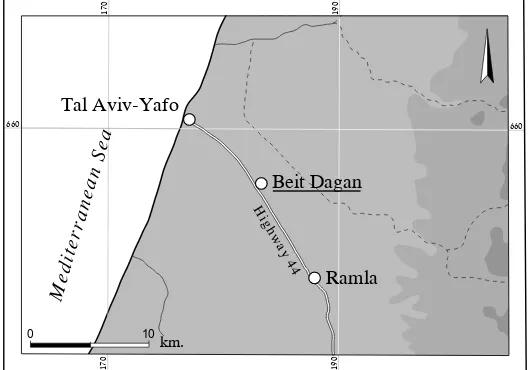

Beit Dagan is located halfway between Tel Aviv and Ramla on the low Hamra Hills adjacent to the southern basin of Nahal Ayalon (Gig. 15.1). It is situated on the outskirts of the third kurkar ridge of the Coastal Plain (Yaalon and Dan 1967, Karmeli,

1 The excavation and inal report were completed with

the assistance of A. Cohen-Klonymus, T. Olech and E. Bar (Area Supervisors), N. Cohen-Alloro (Registrar and Photography), N. Wahidi (Administration), Y. Nagar (Physical Anthropology), D. Porotzky, V. Pirsky, S. Emmanuilov, and I. Ben-Ezra (Plan drawing and Processing), and P. Shargo (Photography). We would also like to thank O. Tal, A. Shavit, T. Harpak, I. Taxel and R. Shimelmitz for contributing to the preparation of this article.

Yaalon and Ravina 1968). Excavations at Beit

Dagan irst took place between 1941–1942 during

the construction of the Tegart British police station, which is located at the Beit Dagan Intersection. The excavations conducted in the southern part of the police courtyard unearthed cist graves lined with stone slabs dated by the excavator to the Roman period.2 In a different excavation west of the mound, occupation levels dated to the Iron I–IIC

and subsequent Persian period were unearthed.

A large Byzantine–Early Islamic winepress and

remains of other structures dated to the same period were also found (Peilstöcker and Kapitaikin 1998:

84–85). In another excavation, tombs dated to the

Intermediate Bronze Age and Roman period were unearthed (Peilstöcker 2006). Close by, additional Intermediate Bronze Age shaft tombs and a large Mamluk period cemetery were found (Yanni 2008;

Yannai and Nagar 2014). Further excavations

2 The excavations were conducted by J. Ory on behalf of

the mandate government (IAA archive ATQ 786, 5.2.42).

Shuqba Cave 0 10 km. Beit Dagan Ramla Tal Aviv-Yafo M ed ite rr an ea

[image:9.595.165.430.471.656.2]n S ea H ig hw ay 44 660 660 170 170 190 190

190

Meir Edrey and Yossi Nagar

nearby unearthed a Byzantine period winepress,

occupation levels dated to the Byzantine–Early

Islamic periods (Rauchberger 2008), and also to the Ottoman period (Gorzalczany and Jakoel 2013; Yechielov 2013).

The excavation presented below took place on

the western border of modern Beit Dagan, in a ield located ca. 400 m southeast of the Tegart British police station (map. ref. 15630-15600/13360-13340) (Fig. 15.1).

METHODOLOGY

The excavation area was mostly lattened due to

unauthorized sand mining activities. Remains of mudbrick and of human skeletons were partly visible on the surface. The upper layer of the excavated area was carefully scraped back by workers until additional human or mudbrick remains were exposed. After exposure, these were articulated and removed. All of the human remains were eventually handed over to a representative of the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

THE EXCAVATION

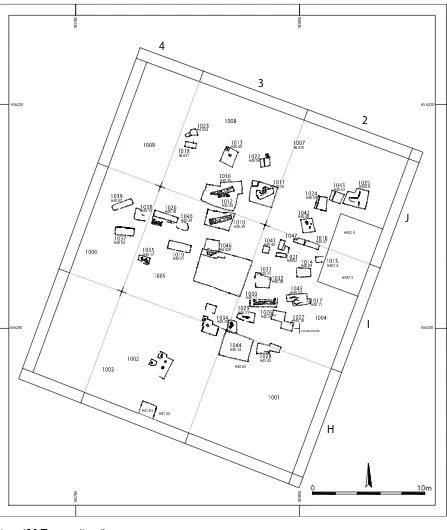

The excavation unearthed 22 human skeletons, mostly in very poor states of preservation, and the remains of 23 mudbrick-covered shallow graves

(Fig. 15.2). Only 12 of the skeletons were found

in graves covered with mudbrick; the rest were buried in simple cist graves dug into the ground, apparently with no markings. All of the burials

were aligned on an east–west axis; the deceased

were laid on their left side, heads in the west, facing

south, according to Islamic burial traditions (Fig.

15.3) (Gorzalczani 2007: 71). All of the deceased were buried at approximately at the same depth. No grave goods or burial offerings were found.

The excavation unearthed only a few scanty

remains. The majority of inds consisted of

extremely worn pottery sherds dated between the

7th to 12th centuries CE. Other inds included lint lakes and one broken lint blade with a retouched

back. Small fragments of glass vessels, tesserae of various sizes, a segment of a small metal chain,

and a single lattened and very eroded coin, which was probably used as an ornament (Fig. 15.4) were

also found.

HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS

Human skeletal remains were found in simple pit or mudbrick lined cist graves. The bones were visually checked on-site, then sent for reburial.

The bones were found in a very poor state of preservation, impeding comprehensive reconstruction of anthropological parameters. Most skeletons were partial, therefore the estimation of age was based upon dental markers (tooth development stages and attrition rate) only (Hillson

1993: 176–201).

Bone Description

Skeleton 10001

The remains included lower limb fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse was set on its right side,

in an east–west orientation, head in the west. Age

and sex estimations were uncertain, however, it was not an infant.

Skeleton 10005

The remains included skull vault, teeth, and post-cranial fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse

was set on its right side, in an east–west orientation,

head in the west facing south. Permanent teeth: upper and lower canines show dentine exposure, upper premolar shows dentine exposure at one cusp. Age at death estimation, based upon tooth

attrition rate: 20–30 years. Sex unknown.

Skeleton 10011

The remains included long bone fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse was set on its right side,

in an east–west orientation, head in the west. Age

and sex estimations were uncertain, however, it was not an infant.

Skeleton 10012

The remains included skull vault fragments and

teeth of an individual set in an east–west orientation,

191

[image:11.595.75.522.145.675.2]Chapter 15: A Mamluk Period Cemetery at Bet Dagan

Figure 15.2:The excavation site.

656200 656220

183800

183780

656200 656220

183800

183780

#40.07

#40.15 #40.18

#40.29

#40.04

#40.17 #40.51

#40.29 #40.39 #40.04 #40.35

#40.39 #40.56 #40.49

#40.31 #40.34

#40.70

#40.59

#40.48

#40.62 #40.48

#40.10

#39.73 #40.14 #40.27

#40.09 #40.02 #40.40

#40.31

#40.38

#40.11

#40.23

#40.11

#40.31

#40.30

#40.26 #40.18

#40.14

#45.45

#40.65

#41.35 #41.03

H

I

J 2

192

Meir Edrey and Yossi Nagar

crown. Age at death estimation, based upon tooth

development stages: 0.5–1 year.

Skeleton 10013

The remains included few non-diagnostic fragments.

Skeleton 10014

The remains included a skull vault, teeth and post-cranial fragments. The bones were found scattered; the original burial posture could not be determined. Permanent upper teeth: central incisor (left) shows dentine cup, lateral incisors and canine show dentine exposure, premolar shows enamel attrition, another premolar shows dentine exposure at one cusp, second and third molars show enamel attrition. Lower teeth: second

premolars show enamel attrition, irst molars show

dentine cup at one cusp, third molar erupted. Age at death estimation, based upon tooth attrition stages:

20–30 years. Sex estimation unknown. Another

permanent upper molar, representing a different individual, was also found in this locus. The tooth was in a development stage of nearly full crown,

indicative of a child, 3–12 years old.

Skeleton 10015.

The remains included a skull vault and one long

bone fragment of an individual set in an east–

west orientation, head in the west facing south. Permanent lower teeth: premolar shows dentine cup

at one cusp, irst molar shows dentine cup in at least

two cusps. Estimation of age at death, based upon

tooth attrition rate: 30–40 years. Sex unknown.

Skeleton 10019

The remains included a skull vault and one long

bone fragment of an individual set in an east–

west orientation, head in the west facing south.

Deciduous teeth: irst molar shows dentine

exposure at three cusps. Permanent upper teeth: canine and premolar show fully developed crown. Estimation of age at death, based upon tooth

development stages: 5–6 years.

Skeleton 10020

The remains included lower limb fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse was set on its right

side in an east–west orientation, head in the

west. Estimations of age and sex were uncertain, however, it was not an infant.

Skeleton 10021

The remains included a skull vault, teeth, and post-cranial fragments. The bones were anatomically

0 1cm

[image:12.595.74.525.86.269.2]193

Chapter 15: A Mamluk Period Cemetery at Bet Dagan

articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse

was put on its right side, in an east–west orientation,

head in the west facing south. Permanent lower

teeth: irst and second premolars and second molar show enamel attrition, irst molar shows dentine

exposure at one cusp, third molar erupted (root broken). Estimation of age at death, based upon

tooth attrition rate: 18–25 years. Sex unknown.

Skeleton 10022

The remains included skull vault fragments of an individual put in the east–west orientation. Age and sex estimations were uncertain, however, it did not represent an infant.

Skeleton 10023

The remains included few non-diagnostic fragments.

Skeleton 10024

The remains included long bone fragments and few rib fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The individual

was put on its right side, in the east–west orientation,

head in the west. Age and sex estimations were uncertain, however, it did not represent an infant.

Skeleton 10025

The remains included lower limb fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The dead was put on its right side,

in the east–west orientation, head in the west. Age

and sex estimations were uncertain, however, it did not represent an infant.

Skeleton 10027

The remains included lower limb fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse was set on its right side,

in an east–west orientation, head in the west. Age

and sex estimations were uncertain, however, it was not an infant.

Skeleton 10031

The remains included two permanent teeth. Canine

shows fully developed crown, upper irst or second

molar show nearly complete crown. Estimation of age at death, based upon tooth development stages:

4–6 years.

Skeleton 10032

The remains included a skull vault, teeth, and post-cranial fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse

was set on its right side, in the east–west orientation,

head in the west facing south. Permanent teeth: upper

premolar shows dentine cup at one cusp, lower irst

molar shows dentine cup at all cusps, third molar erupted. Age at death estimation, based upon tooth

attrition rate: 30–40 years. Sex unknown.

Skeleton 10035

The remains included a few non-diagnostic fragments.

Skeleton 10037

The remains included a skull vault, teeth, and post-cranial fragments. The bones were anatomically articulated, indicating primary burial. The corpse

was set on its right side, in an east–west orientation,

head in the west facing south. Deciduous teeth: canine shows dentine exposure. Permanent teeth: upper central incisor and canine show fully developed crown. Estimation of age at death, based

upon tooth development stages: 4–5 years.

Skeleton 10041

The remains included the skull of an individual

set on its right side, in the east–west orientation,

head in the west facing south. Upper permanent teeth: central incisor and canine show dentine cup, premolar shows dentine exposure at both cusps.

Lower teeth: irst molar shows dentine cup at all

cusps. Estimation of age at death, based upon tooth

attrition rate: 30–40 years. Sex unknown.

Skeleton 10046

The remains included a few non-diagnostic fragments.

Skeleton 10056

The remains included a few non-diagnostic fragments.

DISCUSSION

There were a total of 22 human skeletal remains at the Beit Dagan site. Of them, infants, children

194

Meir Edrey and Yossi Nagar

similar for all: The corpses were set on their right

side, in an east–west orientation, head in the west

facing south. Such posturing of the dead is typical of a Muslim population (Gorzalczani 2007). It is similar to that reported for a previously held nearby

excavation (Yannai and Nagar 2014), and probably

represents a continuation of the same cemetery. Despite the poor state of preservation, the data recovered from the skeletons in this excavation adds to what was reported earlier by Yannai and Nagar (ibid.:217ff). Together with that report the number of burials reaches 93 individuals. The overall sample is typical of a regular historical cemetery population, in which all age groups are represented.

CONCLUSIONS

The excavation most likely represents a section of the Mamluk period cemetery found in previous

excavations (Yanni 2008; Yannai and Nagar 2014:

217ff). The human remains unearthed during this excavation were in a very poor state of preservation due to burial in Hamra soil, which accelerates the decomposition process. The human remains represent a typical historical population. Interestingly, human remains found in graves covered by mudbrick were in a worse state of preservation than those found in simple cist graves. The gray mudbrick material fused with the human bones and it appeared as if the bones were on top of the mudbrick. The graves were either unmarked save for the mudbrick, or were marked with degradable materials, as some burials cut earlier ones. The graves were dug into seemingly sterile ground

as no inds were discovered in their vicinity. The scanty inds found inside the cist graves originated

exclusively from the mudbrick material. This probably indicates that the mudbricks were manufactured elsewhere and brought to the burial site. The pottery unearthed gives a terminus ante quem to the Mamluk

period, which its the dating of the nearby cemetery.

It should be noted that the excavation was abruptly halted due to budget issues and further human remains were left unexposed. Excavated human remains and suspected graves were marked and the

excavation area was covered with sand and left for future excavation. Excavation of further graves in the site continued in 2012 by Dayan and Eshed (2012),

and again in 2014 by Jakoel and Nagar (2014).

REFERENCES

Dayan, A. and Eshed, V. 2012. Bet Dagan. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 124. http://www.hadashot-esi.org.

il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=2187&mag_id=119 Gorzalczany, A. and Jakoel, E. 2013. Bet Dagan.

Hadashot Arkheologiyot 125. http://www. h a d a s h o t - e s i . o r g . i l / R e p o r t _ D e t a i l _ E n g .

aspx?id=5419&mag_id=120

Hillson, S. 1993. Teeth. Cambridge.

Jakoel, E. and Nagar, Y. 2014. Bet Dagan, Ha-Havazzelet

St. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 126. http://www. h a d a s h o t - e s i . o r g . i l / R e p o r t _ D e t a i l _ E n g .

aspx?id=8542&mag_id=121

Karmeli, D., Yaalon, D.H. and Ravina, I. 1968. Dune, Sand and Soil Strata in Quaternary Sedimentary Cycles of the Sharon Coastal Plain. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 17: 45–53.

Peilstöcker, M. 2006. Burials from the Intermediate Bronze Age and the Roman Period at Bet Dagan.

>Atiqot 51: 23–30.

Peilstöcker, M. and Kapitaikin, A. 1998. Bet Dagan.

Hadashot Arkheologiyot 108: 84 (Hebrew).

Rauchberger, L. 2008. Bet Dagan. Hadashot Arkheologiyot

120: http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail.

aspx?id=763&mag_id=114.

Yaalon, D.H. and Dan, J. 1967. Factors Controlling Soil Formation and Distribution in the Mediterranean

Coastal Plain of Israel during the Quaternary.

Quaternary Soils, 7th INQUA Congress Proceedings 1965, 9: 321–338.

Yannai, E. 2008. Bet Dagan. Hadashot Arkheologiyot

120: http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail.

aspx?id=867&mag_id=114.

Yannai E. and Nagar Y. 2014. The Burials. In: Yannai,

E. and Nagar, Y., eds.. Bet Dagan: Intermediate Bronze Age and Mamlok-Period Cemeteries 2004–2005 Excavations. (IAA Reports 55).

Jerusalem: 217–236.

Yechielov, S. 2013. Bet Dagan. Hadashot Arkheologiyot

125. http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_ D e t a i l _ E n g . a s p x ? i d = 2 2 3 1 & m a g _ i d = 1 2 0 Gorzalczani, A. 2007. The Kefar Saba Cemetery and Differences in Orientation of Late Islamic Burials from Israel/Palestine. Levant 39: 71–79.

Table 15.1: Age at death distribution at the Beit Dagan cemetery

Age Estimation (Years) NB–4 5–17 18–24 25–40 40< Unknown Age