An emotional learning environment for subjects with

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Francesca Bertacchini

Environmental and Territorial Engineering and Chemical Engineering Department

University of Calabria, Unical Arcavacata di Rende, Cosenza, ITALY

francescabertacchini@live.it

Eleonora Bilotta, Lorella Gabriele, Diana Elizabeth

Olmedo Vizueta, Pietro Pantano, Francesco Rosa,

Assunta Tavernise, Stefano Vena

Physics Department University of Calabria, UnicalArcavacata di Rende, Cosenza, ITALY eleonora.bilotta@unical.it; lgabriele@unical.it;

dayusnb7@hotmail.com; piepa@unical.it; rosa.avvocato@libero.it, assunta.tavernise@unical.it,

stefano.vena@gmail.com

Antonella Valenti

University of Calabria, Unical Arcavacata di Rende, Cosenza, ITALYavalenti@unical.it

Abstract— Numerous studies highlight that serious games, 3D virtual learning environments and Information Communication Technologies can be powerful tools in supporting people affected by Autism Spectrum Disorders. In particular, they can be very effective in helping to recognize and comprehend social behaviours and emotions.

In this paper, an authoring system designed and implemented in order to stimulate and to facilitate the understanding of emotions is presented (Face 3D). This software could be a highly appropriate tool for autistic children with high cognitive functions, who are often attracted by technology.

Keyword: Emotions, learning, autism, learning by doing, emotional learning environment, teaching/learning strategies, improving classroom teaching, multimedia/hypermedia systems, advanced learning environments.

I. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, advanced 3D virtual learning environments have been designed and implemented in different fields, from training simulation to scientific visualization, from medicine to education. Hence, many researches highlight as individuals affected by an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) can use and interpret virtual environments fruitfully [1, 2, 3], also learning simple social skills [4, 5, 6, 7, 8].

Regarding the ASD, it refers to Autistic Disorder, Asperger's syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, and the Generalized Disorder (pervasive) Development Not Otherwise Specified. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - DSM-V, the American Psychiatric Association affirms that the symptoms of these disorders are so similar that they can be considered belonging to the same continuum, rather than separate entities. In the past, the diagnostic triad of symptoms for these diseases involved lack of social interaction, stereotyped communication, and restricted patterns of interest, while today the DSM-V clusters symptoms in two fundamental criteria: persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts (not explainable by general

developmental delays), and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities. These symptoms have to be present in early childhood and limit or impair everyday functioning [9]. However, thanks to the contribution of autistic children’s

caretakers, several steps on understanding the true nature of autism have been discovered. Hence, the possibility of accurate and timely diagnosis has allowed immediate intervention at different levels, from the most closely medical care to educational plans.

Many developmental processes such as the imitative repertoire that in a child arises during the first years of life and allows to learn language and play with peers are disrupted in the ASD. In this view, several specialized institutions hold master courses devoted to train educators with specific expertise in planning educational activities by using Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) [10, 11, 12, 13]. In particular, ICTs [14] and cognitive artifacts facilitate the processes of imitation and joint attention. In fact, different studies underline how technologies or multimedia software programs can effectively support children and adults with disorders which compromise emotional, relational and behavioural abilities. Some authors [2, 15, 16] use computerized technologies to teach social understanding, while others [17, 18, 19] utilize multimedia technologies to help children in recognize emotion and mental states. Moreover, Burton et al. [20] find how delivering academic content via iPad® to adolescents with autism and intellectual disability can successful influence retention. In comparative studies on traditional materials versus contents delivered via iPad®, Neely et al. [21] demonstrate the feasibility of the iPads® as a powerful instructional method.

24, 25, 26]. By these systems, all information and experienced emotions impress strongly the subject. Furthermore, the improvement of perception, attention and memory, as well as the facilitation of behaviour change are allowed through a

particular way of learning called “learning by doing” [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. As an example, Silver and Oakes (2001) investigated the use of the software the Emotion Trainer

to train individuals with ASD to recognize and anticipate emotions in others. The program uses photographs of real people as well as animated emotional expressions [35]. However, a number of software and virtual environments are at disposal of educators and caretakers.

In this wide possibility of choice, at University of Calabria

(Italy) a new system called “Face3D” has been ideated and implemented. The novelty of this software is represented by the possibility of both inserting real people’ pictures (e.g.

relatives’ photos) for creating virtual avatars, and virtually performing ad-hoc built social situations. Since individuals can differ widely in the manifestation of ASD conditions (an oft

repeated ‘quote’ that is difficult to attribute to one author is, ‘If

you know one person with autism then you know one person

with autism’ [6]), a tool allowing personalized contents has seemed the best choice. Social situations can be numerous and very different; for example, in some researches danger situations have been employed [3]. Moreover, thanks to its

easiness of use, the system could be used by ‘high functioning autistic’ (HFA): although there is not an official diagnosis of the APA, in general, people referred to as having HFA are able to communicate verbally, to read and write, and they do not have a cognitive disability [6]. Moreover, many of HFA individuals are spontaneously attracted by technology. Nevertheless, educators or caretakers can easily learn to realize proper contents.

This study aims at presenting Face3D system and its possible educational use. In particular, the relationship between emotions and autism, as well as a programme devoted to the enhancement of empathy, are explored in the second section. After an explanation of the use of the software in order to realize the programme by educational technology (third section), the instructional use of Face3D is proposed in the fourth part of the paper. The realization of the scenes in the virtual environment is briefly explained in the fifth part and, finally, promising further developments are analyzed in conclusions.

II. EMOTIONS AND AUTISM

The first studies on facial expressions can be dated back to the seventeenth century, even if the most famous are those by Charles Darwin in The expression of the emotions in man and animals [36]. In the twentieth century the most important studies on the theories of emotions and their coding have been carried out [37, 38, 39, 40, 41]. Regarding the coding systems for facial expressions, the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) [42, 43] is the most used in psychological studies and the most precise from a psychometric point of view [44]. Other studies have been focused on the role of non verbal communication in socialization [45, 46], demonstrating that human heads move constantly [44, 47], and that also faces

have constant movements as blinking [48, 49, 50]. Moreover, these researches have demonstrated that transactions from specific facial expressions to other ones are very fast; for example, a smile can come to lips in a split second [51]. Furthermore, the synchronization of language production with gestures is due to the coordination of several components: arms, hands, and head have a structured time organization at different levels [52, 53]. For this reason, for the recognition of facial expressions, different researches have examined various factors [54, 55, 56], as the recognition of familiar faces or the intensity of a facial expression [57], or the identification of an emotion during a continuum [58].

Having social-communication difficulties centred around impairments in communication, impairments in social behaviour, and repetitive behaviours [6, 59], individuals with autism show difficulties in nonverbal communication such as understanding and using facial expressions, as well as gestures [60, 61, 62, 63]. However, many individuals with autism spectrum disorders are able to use a wide range of nonverbal means to communicate, but communication partners are not always able to understand the meaning of the displayed behaviours [64]. The difficulties in communication among individuals with autism have some change: some subject learn spoken language but show difficulties in an appropriate use; many have echolalia and maybe use it with a communicative meaning; some do not acquire functional speech, although many studies suggest that the number of nonverbal individuals is not nearly as high as has been believed [63, 65].

In the programme developed by Valenti [66], the first objective is the recognition of different emotions displayed by the autistic individuals and the other communication partners. The proposal of intervention is arranged in five steps: recognition of facial expressions in pictures; recognition of facial expressions in schematic drawings; identification of emotions in particular social situations; identification of emotions caused by wishes; identification of emotions caused by opinions. These steps can be realized thanks the new 3D learning environment called Face3D, already used with success in numerous educational activities [67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73].

III. FACE3D

available in the system (the creation of new small alterations in these expressions are also possible). The "noise" function, consisting in constant random movements of head and eyes

inspired by Perlin’s studies [78], has also been inserted.

Figure 1 – The parametric basic model in Face3D.

Regarding the GUIs, the main characteristics are the following:

x Face3DEditor allows the facial 3D modelling of real people. This interface offers the opportunity to insert a drawing or a picture under the basic parametric model (Figure 2), and to move the vertices to model the character. In particular, it is possible to select a vertex or a group of vertices of a specific facial area (forehead, nose, eyes, mouth, cheek, chin, neck), or add textures realized in other Computer Graphics software (i.e. eyes and hair).

Figure 2 –THE GUI Face3DEditor.

x Face3DRecorder allows the animation of the created virtual character synchronizing facial expressions with pre-recorded files of speech. Users can select the abovementioned seven standard facial expressions or create new small alterations in these expressions, using specific sliders for each part of the face (Figure 3).

Figure3 – THE GUI Face3DRecorder.

x Virtual Theatre allows the implementation of a performance importing the animations created in Face3DRecorder, as well as the managing of the performance of different virtual agents (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – The GUI Virtual Theatre.

IV. EDUCATIONALUSEOFFACE3D

Starting from the programme developed by Valenti [66], as present in paragraph II, the objective is the recognition of different emotions displayed by the autistic individuals and the other communication partners, using Face3D system.

Step 1 – training on the recognition of facial expressions in pictures. HFA subjects’ pictures and those of their relatives are showed for recognition. In this step, using the virtual learning environment, the participant can:

a) create a virtual face of himself/herself and work with the software to learn how to manage different emotions on his/her own face;

Figure 5 – 3D virtual faces of a child and his relatives (mother, father, and grandmother).

Step 2 – Recognition of facial expressions in schematic drawings (with assignation of scores). The autistic subject observes casual facial expressions in schematic drawings and recognizes the emotions.

In Face3D, the virtual learning environment allows the creation of schemas thanks to the possibility to insert pictures in the GUI. In fact, the system can show the vertices in Face3DEditor.

Step 3 – Identification of emotions in particular social situations.

Step 4 – Identification of emotions caused by wishes. Step 5 – Identification of emotions caused by opinions. In these steps, using Face3D, the subject can:

a) analyze basic emotions in social contexts through a guided process of decoding;

b) create small stories about social events.

Dialogues and social situations can be performed in the GUI Virtual Theatre. Obviously, the different steps in Face3D could also be arranged by educators, thanks to its characteristic of easiness of use.

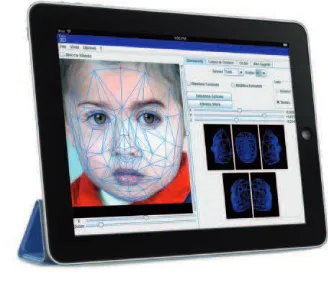

An iPad version of the 3D application (Figure 6) has also been realized by ESG, based on the cross-platform engine Unity for the development of the iPad plugin for the management of contents. Face3D-iPad supports users during the experience by providing the same content of the personal computer version, but also allowing the portability and the access through the touch screen opportunity. In fact, as initial studies confirm, the multi-touch interface characterizing this pervasive technology can be another key of force in autism intervention, since it can stimulate manipulation, eye-hand coordination, perception and intuition.

Figure 6 – IPad-based version of Face3D.

V. HOW TO CREATE THE ANIMATION OF A SOCIAL EVENT USING FACE3D

The first phase consists in the realization of virtual characters. In the GUI Face3DEditor, the Menu File on the toolbar has to be selected. Three different kinds of 3D faces (Woman, Man, or General Model) can be chosen.

In Open Background a picture of real people can be inserted, and the function Block Background utilized to lock the uploaded background. The model can be adapted to the picture moving the vertices and using the cursors X, Y and Z.

Afterwards, in the panel Colore&Texture, it is possible to select the option Texture of a Photograph, and add textures to the face. In order to add textures properly, it is necessary to select both the location for the centre line of the image and a specific part of the picture for each of the vertices. Moreover, the image can be scaled by the function Zoom.

Other textures as ears or hair (created in 3D Max Design software and exported in OBJ format) can be added; to put each object in the right position three types of cursors are active:

x Cursors position X, Y and Z – they allow to move the selected object along the three indicated axes. x Scale Slider – it determines the size of the object. x Rotation Sliders X, Y and Z – they allow the rotation

of the selected object around the three axes.

Through the Remove button the previously selected textures for the object can be removed.

expression. A series of events creates a continuum of different facial expressions during a speech.

Figure 7 – The facial expression “Happiness” in Face3D Recorder, represented by a red point on the timeline.

Finally, the animations of the different characters can be imported in the Virtual Theatre interface through the option

“Add a character”, in order to produce a performance in social circumstances. Two or more characters can interact or a social event can simply be represented. Different situations can be generated.

VI. CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS

Technology has proven to be an effective method of providing students with special needs with opportunities to engage in basic drill and practice, simulations or communication activities that can be matched to their individual needs, levels of functioning and abilities [7, 79]. Face3D, a system developed at University of Calabria (Italy), can help to enhance understanding and reasoning about others’ mental and

emotional states thanks to the possibility of creating avatars and observe them in ad-hoc built social situations. It could be a useful technology because, as Frith [80] affirms, autistic children have to learn social skills systematically, in the same way students learn their school lessons. Moreover, personalized contents can be chosen or created by HFA subjects, even if it is suggested that educators or caretakers realize them.

The proposed 3D learning environment can be seen as a tool for creating cognitive artifacts [81, 82, 83, 84, 85], and it can be proposed in an individualized educational programme. However, it is necessary to remove the current several barriers for the use of technologies at school. For this reason, firstly teachers should be aware of the opportunities guaranteed by this kind of technologies. Moreover, a collaborative use of devices is not only suitable but necessary for ASD subjects.

Regarding the software itself, the Laboratory of Psychology at University of Calabria has planned a version by which it will be possible to careful modify gestures. Moreover, experimentations with Face3D-iPad, the iPad-based application, are in progress.

REFERENCES

[1] Y. Cheng, D. Moore, and P. McGrath, ‘‘Collaborative virtual environment technology for people with autism”. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, vol. 20, n. 4, pp. 231-243, 2005. [2] S. Parsons, P. Mitchell, and A. Leonard, “The use and understanding of

virtual environments by adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders,” Journal of Autism and Developmental disorders, vol. 34(4), pp. 449–466, 2004.

[3] Y. Cheng and J. Ye, “Exploring the social competence of students with autism spectrum conditions in a collaborative virtual learning environment – The pilot study,” Computers & Education, vol. 54, pp. 1068–1077, 2010.

[4] S. Parsons, P. Mitchell, and A. Leonard, “Do adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders adhere to social conventions in virtual environments?,” Autism, vol. 9, pp. 95–117, 2005.

[5] M. Schmidt, J. M. Laffey, C. T. Schmidt, X. Wanga, and J. Stichter, "Developing methods for understanding social behavior in a 3D virtual learning environment," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 28, pp. 405– 413, 2012.

[6] J. E.N. Irish, "Can I sit here? A review of the literature supporting the use of single-user virtual environments to help adolescents with autism learn appropriate social communication skills," Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 29, Issue 5, Pages A17–A24, in press.

[7] V. Hulusica and N. Pistoljevicb, “LeFCA”: Learning framework for children with autism, Procedia Computer Science, vol. 15, pp. 4-16, 2012 [Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-GAMES’12)]

[8] Y. Cheng, H. Chiang, J. Ye, and L.Cheng, "Enhancing empathy instruction using a collaborative virtual learning environment for children with autistic spectrum conditions," Computers & Education, vol. 55, 1449–1458, 2010.

[9] American Psychiatric Association, “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disordersm - Fifth Edition (DSM-5™),” Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

[10]A. Valenti, "I nodi problematici dell'integrazione scolastica," in Scuola e Integrazione, D. Milito, Ed., Roma: Anicia, 2008, pp. 55-66.

[11]A.Valenti, "Il bambino con autismo nella scuola di tutti," in I percorsi formativi tra analisi teoriche e proposte educative, A. Valenti, Ed., Napoli: Luciano, 2007, pp. 107-123.

[12]P.A. Bertacchini, A. Feraco, E. Pantano, A. Reitano, A. Tavernise, “Cultural Heritage 2.0 – “Prosumers” and a new collaborative environment related to Cultural Heritage,” International Journal of Management Cases, 2008, vol. 10, n. 3, pp. 543-550, 2008.

[13]M. Martirani, C. Perri, and A. Valenti, "I bisogni formativi dell'insegnante specializzato: risultati di una ricerca," in Didattica e didattiche disciplinari - Quaderni per la nuova secondaria, vol. 5, F.A. Costabile, Ed., Cosenza: Pellegrini, 2007, pp. 81-154.

[14]E. Pantano, A. Tavernise, and M. Viassone, “Consumer perception of computer-mediated communication in a social network,” 4th International Conference on New Trends in Information Science and Service Science - NISS, vol. II, Gyeongju - Korea, pp. 609-614, 11 – 13 May, 2010. [15]V. Bernard-Opitz, N. Sriram, and S. Nakhoda-Sapuan, “Enhancing social

problem solving in children with autism and normal children through computerassisted instruction,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 31, pp. 377–384, 2001.

[17]S. Bolte, S. Feineis-Matthews, S. Leber, T. Dierks, D. Hubl, and F. Poustka, “The development and evaluation of a computer-based program to test and to teach the recognition of facial affect,” International Journal of Circumpolar Health, vol. 61, pp. 61–68, 2002.

[18]S. Baron-Cohen, O. Golan, S. Wheelwright, and J. J. Hill, "Mind reading: The interactive guide to emotions”. London: Jessica Kingsley Limited, 2004.

[19]P. G. LaCava, O. Golan, S. Baron-Cohen, and B. Smith Myles, “Using assistive technology to teach emotion recognition to students with Asperger syndrome: A pilot study,” Remedial and Special Education, vol. 28, pp. 174–181, 2007.

[20]C.E. Burton, D.H. Anderson, M.A. Prater, and T.T. Dyches, “Video self-modeling on an ipad to teach functional math skills to adolescents with autism and intellectual disability,” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28 (2), pp. 67-77, 2013.

[21]L. Neely, M. Rispoli, S. Camargo, H. Davisn, and M. Boles, “The effect of instructional use of an iPad1 on challenging behavior and academic engagement for two students with autism,” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, vol. 7, pp. 509–516, 2013.

[22]E. Pantano and A. Tavernise, “Enhancing the educational experience of Calabrian Cultural Heritage: a technology-based approach,” in Human Development and Global Advancements through Information Communication Technologies – New Initiatives, S. Chhabra and H. Rahman, Eds. Hershey, PA - USA: IGI Global, 2011, pp. 225 – 238. [23]G. Naccarato, E. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Educational personalized

contents in a Web environment: Virtual Museum Net of Magna Graecia,” in Handbook of Research on Technologies and Cultural Heritage: Applications and Environments, G. Styliaras, D. Koukopoulos, and F. Lazarinis, Eds. Hershey, PA - USA: IGI Global, 2011, pp. 446 – 460. [24]F. Bertacchini and A. Tavernise, “Using Virtual Museums in education:

tools for spreading Calabrian Cultural Heritage among today’s youth,” in Archaeological Heritage: Methods of Education and Popularization, R. Chowaniec and W. Wieckowski, Eds. Oxford – England: BAR IS (British Archaeological Reports International Series) 2443, 2012, pp. 25 – 30. [25]R. Chowaniec and A.Tavernise, “Fostering education through virtual

worlds: the learning and dissemination of ancient Biskupin,” in Archaeological Heritage: Methods of Education and Popularization, R. Chowaniec and W. Wieckowski, Eds. Oxford – England: BAR IS (British Archaeological Reports International Series) 2443, 2012, pp. 43 – 47. [26]F. Bertacchini and A. Tavernise, “NetConnect virtual worlds: results of a

learning experience,” in Virtual Worlds in Online and Distance Education, S. Gregory, M.J.W. Lee, B. Dalgarno, and B. Tynan, Eds. Australia: Athabasca University Press, 2013.

[27]E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, R. Servidio, and A. Tavernise, “Motor Manipulatory Behaviours and Learning: an Observational Study,” International Journal of Online Engineering - iJOE, vol. 4, n. 3, pp. 13 – 17, 2008.

[28]P.A. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, P. Pantano, and R. Servidio, “Apprendere con le mani. Strategie Cognitive per la Realizzazione di Ambienti di Apprendimento-insegnamento con i Nuovi Strumenti Tecnologici,” Milano: Franco Angeli, 2006.

[29]F. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, P. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, (2013). Toward the Use of Chua’s Circuit in Education, Art and Interdisciplinary Research: Some Implementation and Opportunities. Leonardo, 46 (5), 2013.

[30]E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, R. Servidio, and A. Tavernise, “Edutainment Robotics as Learning Tool,” in Transactions on Edutainment III, Z. Pan, A.D. Cheok, W. Müller, and M. Chang, Eds. Springer Berlin: Heidelberg, NuovaSerie, Vol.2 LNCS 5940, 2009, pp. 25-35, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-11245-4_3.

[31]F. Bertacchini, L. Gabriele, and A. Tavernise, “Looking at Educational Technologies through Constructivist School Laboratories: problems and future trends,” Journal of Education Research, vol. 6, issue 2, pp. 235-239, 2012.

[32]L. Gabriele, “Tecnologie didattiche e robotica educativa per supportare lo sviluppo nei soggetti autistici," Periferia, vol. 2(81), pp. 59-69, 2012, [33]L. Gabriele, A. Tavernise, and F. Bertacchini, “Active Learning in a

Robotics Laboratory with University Students”, in Increasing Student Engagement and Retention Using Immersive Interfaces: Virtual Worlds,

Gaming, and Simulation. Cutting-Edge Technologies in Higher Education Vol. 6C. C. Wankel and P. Blessinger, Eds., Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2012, pp. 315-339.

[34]G. Faraco and L. Gabriele, “Using LabVIEW for applying mathematical models in representing phenomena,” Computers & Education, vol. 49 (3), pp. 856-872, 2007. 10.1016/j.compedu.2005.11.025.

[35]A. L. Wainer and B. R. Ingersoll, “The use of innovative computer technology for teaching social communication to individuals with autism spectrum disorders,” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, vol. 5, pp. 96–107, 2011.

[36]C. Darwin, “The expression of the emotions in man and animals,” New York: Academic Press, 1872, 3rd Edition: 1998.

[37]P. Ekman, “Facial expression and emotion,” American Psychologist, vol. 48, 384-392, 1993.

[38]P. Ekman, “Facial Expressions,” in Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. T. Dalgleish and M. Power, Eds. New York: Wiley & Sons, 1999. [39]C.E. Izard, “Human emotions,” New York: Plenum, 1977.

[40]C.E. Izard, “Facial expression scoring manual (FESM),” Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware, 1979.

[41]P. Ekman and E. Rosenberg, “What the face reveals (2nd ed.)”, New York: New York. 2005.

[42]P. Ekman and W.V. Friesen, “Facial action coding system,” Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978.

[43]P. Ekman, W.V. Friesen, and J. Hagen, “The Facial Action Coding System,” London: Weidenfeld Nicolson, 2002.

[44]J.F. Cohn, L.I. Reed, T. Moriyama, J. Xiao, K.L. Schmidt, and Z. Ambadar, “Multimodal coordination of facial action, head rotation, and eye motion,” Sixth IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition. Seoul - Korea, pp. 645-650, 17-19 May, 2004. [45]S. Kaiser, “Facial expressions as indicators of ‘functional’ and

‘dysfunctional’ emotional processes,” in The human face: Measurement and meaning. M. Katsikitis, Ed. Dordrecht - the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002.

[46]U. Hess and P. Philippot, “Group Dynamics and Emotional Expression,” New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[47]D. Roark, S.E. Barrett, M.D. Spence, H. Abdi, and A.J. O'Toole, “Psychological and neural perspectives on the role of facial motion in face recognition,” Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, vol. 2(1), pp. 15-46, 2003.

[48]P.A. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, P. Pantano, S. Battiato, M. Cronin, G. Di Blasi, A.Talarico, A. Tavernise, “Modelling and Animation of Theatrical Greek Masks in an Authoring System,” Eurographics Italian Chapter 2007 Conference, pp. 191-198, 14 – 16 February 2007, Trento (Italy), DOI: 10.2312/LocalChapterEvents/ItalChap/ItalianChapConf2007/191-198.

[49]E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, R. Servidio, and A. Tavernise, “Espressioni facciali in agenti virtuali: il software Face3D e il riconoscimento di emozioni,” Giornale di Psicologia, vol. 4(2), pp. 139 – 148, July 2010. [50] P.A. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, R. Servidio, and A. Tavernise,

“La modellazione 3D di espressioni facciali per il riconoscimento delle emozioni,” National Congress of Experimenthal Psychology – Associazione Italiana di Psicologia, 18-20 of September, 2005, Cagliari, 2005.

[51]L. Zhang, N. Snavelvelyn, B. Curless, and M. S. Seitz, “Spacetime faces: high resolution capture for modeling and animation,” SIGGRAPH2004, vol. 23(3), pp. 548-558, 2004.

[52]G. Schöner and J.A.S. Kelso, “Dynamic pattern generation in behavioral and neural systems,” Science, vol. 239, 1513-1520, 1988.

[53] S. Kopp and I. Wachsmuth, “Natural timing in coverbal gesture of an articulated figure - Working notes,” Workshop Autonomous Agents ’99, Seattle, 1999.

[54]J. A. Russell, “Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expression? A review of the cross-cultural studies,” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 115, pp. 102-141, 1994.

[56]S.D. Pollak, M. Messner, D. J. Kistler, and J. F. Cohn, “Development of perceptual expertise in emotion recognition.,” Cognition, vol. 110(2), pp. 242-247, 2009.

[57]U. Hess, S. Blairy, and R.E. Kleck, “The intensity of emotional facial expressions anddecoding accuracy,” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, vol. 21 (4), pp. 241–257, 1997.

[58]N.L. Etcoff and J.J. Magee, “Categorical perception of facial expressions. Cognition,” vol. 44, pp. 227-240, 1992.

[59]L. Wing and J.Gould, “Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: epidemiology and classification,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 9, n. 1, pp. 11–29, 1979.

[60]J. Boucher, “Language development in autism,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, vol. 67S1, pp. 159-163, 2003.

[61]L.K. Koegel, “Communication and language intervention (6th printing),” in Teaching children with autism. Strategies for initiating positive interactions and improving learning opportunities, R.L. Koegel and L.K. Koegel, Eds., Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing, pp. 17-32, 2003. [62]H. De Clercq, “L’autismo da dentro. Una guida pratica (Trad. It. A.

Valenti)”. Trento: Erickson, 2011.

[63]V. Vellonen, E. Kärnäa, and M. Virnes, “Communication of children with autism in a technology-enhanced learning environment,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 69, pp. 1208 – 1217, 2012. [64]A. Wetherby, B. Prizant, and A. Schuler, “Understanding the nature of

communication and language impairments,” in Autism spectrum disorders: A transactional developmental perspective, A. Wetherby and B. Prizant, Eds. Baltimore: Brookes, pp. 109-141, 2000.

[65]H. Tager-Flusberg, R. Paul, and C. Lord, “Language and communication in autism,” in Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders, D. J. Cohen and F. R. Volkmar, Eds. New York: Wiley, pp. 335-364, 2005.

[66]A. Valenti, “Autismo. Modelli teorici, principi pedagogici e applicazioni educative,” Roma: Monolite Editrice, 2008.

[67] A. Tavernise, L. Gabriele, and P.A. Bertacchini, “Simulazioni di agenti in un teatro greco,” 2° Workshop Italiano di Vita Artificiale, Istituto di Scienze e Tecnologie della Cognizione, CNR, Roma, 2-5 Marzo, 2005, G. Baldassarre, D. Marocco, and M. Mirolli, Eds. Roma: CNR, 2005. [68]E. Bilotta, P. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Using an Edutainment Virtual

Theatre for a Constructivist Learning,” 18th International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE 2010) - New paradigms in learning: Robotics, play, and digital arts”, T. Hirashima, A.F. Mohd Ayub, L.-F. Kwok, S.L. Wong, S.C. Kong, and F.-Y. Yu (Eds.), Putrajaya, Malaysia: Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education, pp. 356–360, 29 November – 3 December, 2010.

[69]E. Bilotta, F. Bertacchini, L. Gabriele, and A. Tavernise, “Education and Technology: Learning By Hands-On Laboratory Experiences,” EduLearn2011 Conference – IATED, pp. 6475-6483, Barcelona, Spain,. 2011.

[70]E. Bilotta, F. Bertacchini, G. Laria, P. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Virtual Humans in Education: some implementations from research studies,” EduLearn2011 Conference – IATED, pp. 6465–6474, Barcelona, Spain, 2011.

[71]F. Bertacchini, L. Gabriele, and A. Tavernise, “Bridging Educational Technologies and School Environment: implementations and findings from research studies,” in Educational Theory. Series: Education in a Competitive and Globalizing World, J. Hassaskhah, Ed., Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp. 63-82, 2011.

[72]F. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, P. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Motivating the learning of science topics in secondary school: A constructivist edutainment setting for studying Chaos,” Computers & Education, vol. 59 (4), pp. 1377–1386, 2012.

[73]F. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, and A. Tavernise, “Sviluppare la creatività nella scuola primaria attraverso la costruzione di storie con il software Face3D Virtual Theatre,” XII Congresso Nazionale della Sezione di Psicologia Sociale - Associazione Italiana di Psicologia - AIP, Padua (Italy), 26-28 September 2013, in press.

[74]A. Adamo, P.A. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, P. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Connecting art and science for education: learning through an advanced virtual theater with ‘Talking Heads’,” Leonardo Journal, MIT press, vol. 43(5), pp. 442–448, 2010.

[75]E. Pantano and A. Tavernise, “Learning Cultural Heritage through Information and Communication Technologies: a case study,” International Journal of Information Communication Technologies and Human Development, vol. 1(3), pp. 68-87, July-September 2009. DOI: 10.4018/jicthd.2009070104.

[76]V. Corvello, E. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “The design of an advanced Virtual Shopping Assistant for improving consumer experience,” in Advanced Technologies Management for Retailing: Frameworks and Cases, E. Pantano and H. Timmermans, Eds. Hershey, PA - USA: IGI Global, pp. 70–86, 2011.

[77]A. Tavernise, “Narrazione e Multimedia - Ricerca educativa e applicazioni didattiche,” Roma: Ed. Meti, 2012.

[78]K. Perlin, Layered compositing of facial expression. ACM/SIGGRAPH Technical Sketch, http://mrl.nyu.edu/ perlin/experiments/facedemo, 1997. [79]E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, R. Servidio, and A. Tavernise, “Edutainment

robotics as learning tool,” 4th International Conference on E-Learning and Games 2009, Springer's LNCS 5670, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, p. 422, 2009. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-03364-3_5.

[80]U. Frith, “Autism explaining the enigma (2nd ed.),” Cornwall, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

[81]F. Bertacchini, A. Tavernise, L. Gabriele, E. Bilotta, P. Pantano, F. Rosa, and M. Carini, “Musical Lab role in developing creativity and cognitive skills,” EduLearn13 - International Conference on Education and New Learning technologies, Barcelona (Spain), 1 – 3 July 2013.

[82]A. Febbraro, G. Naccarato, E. Pantano, A. Tavernise, and S. Vena, “The fruition of digital cultural heritage in a web community: the plug-in "Hermes"," IADIS Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (MCCSIS’08) - WBC 2008, Amsterdam, 22 - 27 July, 2008, Kommers P., Ed., pp. 93-99, 2008.

[83]E. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Learning Cultural Heritage through Information and Communication Technologies: a case study,” in Handbook of Research on Computer Enhanced Language and Culture Learning, M. Chang & C.-W. Kuo, Eds., Hershey, PA - USA: IGI Global, pp. 103 – 119, 2009.

[84]F. Bertacchini, E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, P. Pantano, and A. Tavernise, “Art inside Chaos: New Routes to Creativity and Learning,” Leonardo OL, 2012. Online access: http://leonardo.info/isast/journal/bilotta-chaos-article.html. Updated 5 January 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2012. [85]E. Bilotta, L. Gabriele, R. Servidio, and A. Tavernise, “Investigating