Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:17

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Short-Term Study-Abroad Programs–A Professional

Development Tool for International Business

Faculty

Troy A. Festervand & Kenneth R. Tillery

To cite this article: Troy A. Festervand & Kenneth R. Tillery (2001) Short-Term Study-Abroad Programs–A Professional Development Tool for International Business Faculty, Journal of Education for Business, 77:2, 106-111, DOI: 10.1080/08832320109599058

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320109599058

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 111

View related articles

Short-Term Study-Abroad

P

rog rams-A Professional

Development Tool for International

Business Facultv

TROY A. FESTERVAND

KENNETH R. TILLERY

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Middle Tennessee State University

Murfreesboro,

Tennessee

ost academicians and practition-M

ers today generally embrace the notion that those involved in the global marketplace need greater exposure to the international business environment. In accord with this charge, the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) has stated in its accreditation standards that this area is a key business education aspect thai should include coverage of ethical, environmental, and demographic issues. This international mandate applies to all institutions.Business faculty and administrators are also charged with a professional development responsibility in addition to an international responsibility. According to the AACSB, professional development is an ongoing process that includes such activities as participation in professional organizations, research and publication, continuing education, the acquisition of new and/or additional technical and discipline specific skill sets, and other enriching activities (Sewell, 1999). Participation in a short- term study-abroad educational experi- ence, such as that described in this arti- cle, is consistent with that charge.

In this study, we discuss an interna- tional program that was developed pred- icated upon the acceptance of these

106

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for BusinessABSTRACT. In this article, the authors describe how faculty participa- tion in a short-term study-abroad pro-

gram contributed to faculty members’ international professional development

and teaching effectiveness. The acade- mic program and development experi- ence described occurred within the context of a graduate economics course that was developed in Japan and

conducted on several occasions. The

faculty who participated in this pro-

gram assumed the role of student, not program leader, instructor, or coordi- nator. In this juxtapositional role,

numerous experiential benefits,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

skills, and knowledge were acquired that oth-erwise would not have been possible. The intent of this article was to identi-

fy specific areas in which international professional development takes place and demonstrate how this international experience ultimately contributes to academic improvement.

charges and the perceived relevance and criticality of international exposure to both students and faculty. Faculty mem- bers, administration, and the university as a whole must accept and satisfy the responsibility for preparing students, as well as faculty, for the challenges and opportunities increasingly found in the global marketplace. The experience described in this article show how this professional development responsibility has been defined and operationalized in

the College of Business at Middle Ten- nessee State University (MTSU).

Our purpose in this article was to share our experiences, insight, and con- clusions gleaned from our participation in a short-term, international graduate economics course offered in Japan. We served in the roles of guest, adjunct fac- ulty, and part-time program contributor; on the basis of our combined experi- ences, we developed a chronicle of our activities and associated professorial reflections. We also profile the program, identify and discuss multiple areas in which this experience contributed to our professional development and offer pro- fessional development suggestions.

Program Overview

To broaden the international horizons of graduate students, a multisession, graduate economics class was devel- oped incorporating a 2-week interna- tional trip. This program has been con- ducted successfully four times; consequently, we have learned a great deal about its successful planning, organization, and execution. Because each institution has a unique set of parameters, the program and experi- ences that we outline should serve as a benchmark or starting point from which

individual adjustments and refinements can be made.

The program’s primary objective is to expose graduate students to the interna- tional business and economic environ- ment. Activities such as tours of over- seas businesses and institutions; discussions with executives; and expo- sure to cultural, historical, political, and technological institutions outside of the United States contribute to the achieve- ment of this objective. An additional objective of the program, and the focus of this article, is the contribution of the program and experience to the profes- sional development of international business educators.

Two practical matters have con- strained the scope of this program. First, given the students targeted for this course, financial exigencies limited the program’s scope. Second, because the program necessitates absence from campus for 2 weeks, it is important that neither the participating faculty mem- bers’ attendance in other classes nor stu- dent work schedules be disrupted. To achieve the program’s objectives within established parameters, we develped a graduate economics course for nontra- ditional students. This course is offered during a summer session and is broken into Part 1, presentation of the requisite academic preparation, and Part 2, the

international experience.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Target Markets

Many universities conduct short-term international trips that appeal to students across a broad range of disciplines. In contrast, this international exposure is targeted toward K-12 educators and administrators who meet minimum graduate prerequisites. A limited num- ber of university faculty members seek- ing to enhance their international cre- dentials also are allowed to enroll as non-degree-seeking graduate students.

Several advantages are associated with this approach. First, the relatively homogeneous background of K-12 fac- ulty and administrators makes a high level of concentrated academic content possible. Second, by focusing on the K-12 educator student, the university contributes to its community service responsibility. Third, participating stu-

dents return to their respective campus- es and become ambassadors who share their experiences and promote the uni- versity and program to others. Finally, participating, academically qualified faculty acquire needed international skills and experience, thus contributing to their professional development.

Having one or two university faculty members join the class serves several useful purposes in addition to profes- sional development. The university’s faculty provides an excellent source for obtaining a limited number of students. Because faculty from all disciplines typ- ically are interested in various aspects of international culture and travel, selec- tion criteria must be developed and applied. The program we describe selected those faculty members consid- ered most interested and for whom the experience would be most beneficial. Selecting faculty members who have traveled internationally is useful, because prior experience often can be extended to the current experience. Fur- ther, faculty members familiar with, or who have teaching or research interests in, a particular culture or region are ideal candidates. Others familiar with trip routines, protocol, and logistics have the potential to reduce the admin- istrative burden of the faculty organizer. Faculty members also contribute to the final class size and, because of universi- ty policy, may be eligible to register for the class at no cost. Finally, securing instructional development grant support from the university may be a viable source with which to partially or entire- ly fund a faculty member’s expense.

Program Components

Program objectives, academic con- tent, and student issues are of primary importance in offering an international educational experience. However, edu- cators involved soon find that a great deal of preprogram time and effort are required, because they must address a number of programmatic issues to ensure maximum benefits. Resolving these issues involves a sequence of deci- sions, each of which requires research and reflection. For example, within the context of an international education experience, “place” is a multidimen-

sional construct involving such issues as country or countries of destination; local destination(s); visits to economic, historical, and cultural attractions and relevant objectives; and itinerary, trans- portation, lodging, and meal decisions. Active involvement in the resolution of these issues by participating faculty members represents an additional, albeit somewhat less academic, aspect of their

professional development.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Destination

Though research has shown that Western Europe routinely emerges as the favorite international venue, internation- al experiences involving Asian nations also rank high because of the economic importance of those countries and the mystique that surrounds the Asian cul- ture. Within this group of Asian nations, no country offers more cultural and eco- nomic insight and opportunity than Japan. An international education expe- rience in Japan is an ideal international destination for several reasons:

1. The Japanese experience provides students with an exposure to a signifi- cantly different social, political, and economic environment. The experience also highlights a variety of non-Western educational and religious practices. Japan’s deep and broad assortment of both commercial and cultural institu- tions also makes it attractive from a pro- grammatic perspective.

2. Because of its size, Japan allows the class to operate using a series of rel-

atively short trips.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

As such, a number ofmajor cities and sites may be visited without requiring exorbitant amounts of travel time or expense. Notable cities include Tokyo, Osaka, and Hiroshima. Within Japan’s major cities, a plethora of multinational organizations (e.g., Nis- san, Bridgestone, Toshiba, and Sony) can be visited. Requests for tours and visits often are welcomed and provide an in-depth look at how these organiza- tions conduct business on a global scale.

3. In addition to international busi- nesses, most cities boast major universi- ties and cultural attractions. Experience has shown that a blend of these sites, vis- its, and tours is optimal, as a combination seems to provide synergistic benefits.

NovembedDecember 2001 107

Air Transportation

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

According to an old saying, “Half the fun of any trip lies in getting there.” This adage may be true on some occa- sions and for some persons; however, in

reality flying to Japan involves

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

14 hours in economy class, a fact representingthe major “downside” of the Japanese experience.

Ground Transportation

For groups of up to 15 students, such as our class, the use of public trans- portation is recommended. Bus and train networks in Japan are efficient, reasonably priced, and very convenient. In addition, the purchase of tickets andlor day passes provides students with opportunities to conduct small transactions, calculate foreign exchange equivalents, and become participants in the local culture and economy. Faculty members may find the local transporta- tion experience refreshing and educa- tional. Although the culture does not have the same love affair that the Unit- ed States has with automobiles, Japan- ese mass transporation is more comfort- able and efficient than its U.S. counterpart.

In planning ground transportation, both long-haul and local transport must be considered. Though short-haul, sin- gle tickets may be purchased, they tend to be expensive and somewhat inconve-

nient. As

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an option, unlimited mileage rail passes may be purchased. Thesepasses provide excellent value when a class involves multiple trips and covers significant distances. In Japan, the cost of a 2-week, unlimited-travel rail pass is

approximately

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

$375 and includes localand long-distance rail service.

Housing

As in other developed countries, Japan offers a number of lodging alter- natives including university dormito- ries, hotels, hostels, and home-stay options. For relatively brief visits involving multiple sites and frequent movement, we recommend extensive use of smaller hotels and youth hostels. Given the daily programmatic activities

typically involved, having everyone

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

108 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessbegin the day at the same time and place simplifies group movement.

In contrast with large hotels, smaller hotels and hostels offer several advan- tages. First, room rates can be negotiat- ed (a cultural experience in itself) and thus have the potential to be reasonably priced. Second, smaller hotels and hos- tels often are located in close proximity to major attractions and/or transporta- tion systems (i.e., subway or train). Finally, these accommodations tend to have interesting characteristics that are more reflective of the culture (again, a learning experience).

An international education experi- ence is not complete without a home stay. In this program, a limited home stay of 1 to 2 nights is available. These arrangements are made several months in advance through a local contact at a sister institution. Student and faculty spend 1 or 2 nights with a host family and experience the Japanese culture at the family level. Host families consider this an honor and customarily arrange special dinners, sightseeing excursions, and entertainment.

The giving and receiving of gifts is a Japanese custom and one that requires thought and attention. The host family typically gives a guest one or several gifts that reflect the Japanese culture. In turn, guests are encouraged to provide each member of the family or the entire family a gift that reflects the guests’ cul- ture. Locally produced items, personal- ized items, or unique items are recom- mended. Host families also enjoy personal photos that depict varied aspects of their guest’s personal life, especially his or her family. It is custom- ary for the host family to pay for all expenses associated with a home stay.

Academic Requirements and Content

First and foremost, the program’s re- quirements must meet (minimally) or exceed (as planned) university, college of business, graduate, and accreditation standards. Graduate students participat- ing in this international economics course are awarded 3 hours of graduate, elective course credit following their successful completion of all course requirements. These requirements include attending classes (classes meet

all day on 3 Saturdays prior to depar- ture), reading a compilation of articles that address various international issues, and obtaining satisfactory grades on a pretrip exam and posttrip term paper.

In this course, 25% of the student’s final grade is based on pretrip-related activities, including preparation and in- class presentation of materials relating to international economics; doing busi- ness in Japan; and the associated impli- cations of the Japanese culture, politics, and education (course reading list is available upon request). Fifty percent of

the student’s final grade is based on the student’s performance on the course’s only examination, which covers all the material presented in class and required readings. The pretrip exam consists of multiple essay questions that address specific issues associated with particu- lar presentationsheadings and general questions regarding differences between

U.S. and Japanese environments and

associated economic implications. The final 25% of the student’s course grade is based on a completed trip diary and term paper. The former focuses on the entire international experience and includes each student’s unique, daily observations and thoughts on the trip, along with anecdotal events and com- ments regarding personal experiences. The required posttrip term paper (due 2 weeks following return) addresses an international topic jointly selected by the student and professor (e.g., U.S./Japan balance of trade).

Program Itinerary

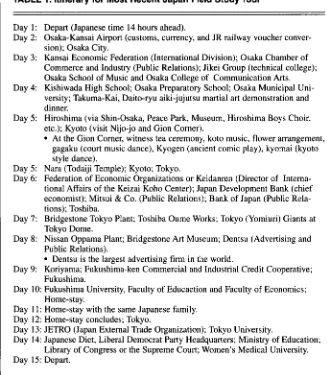

In Table 1, we present the itinerary for the most recent Japan Field Study tour. Though each program must decide on the amount of time to be spent on academic versus personal pursuits, this program limits the latter, given tempo- ral, academic, and financial parameters. Other program designers may decide to more discretionary time if they have different objectives, resources, and markets.

Faculty Development

It is generally accepted that faculty development should center around ac- tivities that promote the creation and

TABLE 1. Itinerary for Most Recent Japan Field Study Tour

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Day

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 : Depart (Japanese time 14 hours ahead).Day

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2: Osaka-Kansai Airport (customs, currency, and JR railway voucher conver-sion); Osaka City.

Day

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3: Kansai Economic Federation (International Division); Osaka Chamber ofCommerce and Industry (Public Relations); Jikei Group (technical college); Osaka School of Music and Osaka College of Communication Arts.

Day

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4: Kishiwada High School; Osaka Preparatory School; Osaka Municipal Uni-versity; Takuma-Kai, Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu martial art demonstration and

dinner.

Day

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5: Hiroshima (via Shin-Osaka, Peace Park, Museum, Hiroshima Boys Choir, etc.); Kyoto (visit Nijo-jo and Gion Comer).At the Gion Corner, witness tea ceremony, koto music, flower arrangement, gagaku (court music dance), Kyogen (ancient comic play), kyomai (kyoto style dance).

Day 5: Nara (Todaiji Temple); Kyoto; Tokyo.

Day 6: Federation of Economic Organizations or Keidanren (Director of Intema- tional Affairs of the Keizai Koho Center); Japan Development Bank (chief economist): Mitsui & Co. (Public Relations); Bank of Japan (Public Rela- tions); Toshiba.

Day 7: Bridgestone Tokyo Plant; Toshiba Oume Works; Tokyo (Yomiuri) Giants at Tokyo Dome.

Day 8: Nissan Oppama Plant; Bridgestone Art

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Museum; Dentsu (Advertising andPublic Relations).

Dentsu is the largest advertising firm in the world.

Day 9: Koriyama; Fukushima-ken Commercial and Industrial Credit Cooperative; Fukushima.

Day 10: Fukushima University, Faculty of Educaction and Faculty of Economics; Home-stay.

Day 11: Home-stay with the same Japanese family. Day 12: Home-stay concludes; Tokyo.

Day 13: JETRO (Japan External Trade Organization); Tokyo University.

Day 14: Japanese Diet, Liberal Democrat Party Headquarters; Ministry of Education; Day 15: Depart.

Library of Congress or the Supreme Court; Women’s Medical University.

transfer of knowledge. Outcomes are displayed through the individual’s teaching, research, and public service. Though individual faculty members in the international arena are expected to continually extend their knowledge of other cultures, because of increasing globalization of the business communi- ty, this need is also being recognized in other disciplines, often as a requirement for (re)accreditation purposes. Specific benefits or aspects of professional de- velopment accrue to a faculty member who participates in an international edu- cation experience. These benefits include academic validation, intellectu- al growth, acculturation, academic administration, and cognitive reposi- tioning.

Academic Validation

One of the most direct professional development results sought and provid-

ed by a study abroad experience is the grounding of concept and theory in reality, an outcome directly transferable to both future teaching and research activities. In this context, the experi- ence described was refreshing and vali- dating for both of us. For one of us, the benefits of prior work experience in the Middle East and travel in Japan and other parts of Southeast Asia had suf- fered the erosions of time. Lectures and class discussions were becoming staid, reflecting research results at the expense of incorporating real-life appli- cations. There was a need to see if the literature and prior experience were still valid.

As many readers are aware, interna- tional business texts and classroom dis- cussions often are filled with lengthy discussions of international entry srate- gies, operating guidelines, cultural nuances, and so forth. After multiple iterations of such discussions, the

instructor may begin to find their themes or validity muted, convoluted, or questionable. The primary benefit of a faculty member’s participation in a short-term international experience such as the one described in this article may be the resulting professional vali- dation. Meetings with corporate offi- cials, observation of business practices, and direct experience of cultural ideo- syncracies represent an “academic refu- eling’’ that provides the academic vali- dation so sorely needed.

Intellectual Growth

Whether academicians choose to admit it or not, after teaching a given class for a number of semesters, an instructor tends to emphasize the same topics, examples, literature, and so forth. Perhaps that is human nature, or perhaps the multiplicity of demands placed on a particular faculty member has rigidifed his or her perspective. Alternatively, after teaching the same class over an extended period of time, instructors may become so sure of their knowledge of the material that they do not think more or new information is necessary.

In any of these possible scenarios, the faculty members’ participation in a short-term international experience will result in the generation of signifi- cant intellectual growth. In some instances, new knowledge is acquired through overt, concerted efforts. As the course itinery described in this article indicates, we experienced this intellec- tual growth on multiple occasions and via multiple pedagogies (e.g., visits and discussions with Nissan, Toshiba, and Bank of Japan). Though not antici- pated, most intellectual growth occurred vicariously. Given our roles as participating faculty members (as described earlier), we could simply observe, listen, and experience. In this limited and passive role, we could identify a multitude of issues, topics, behaviors, and practices that, though rarely identified and discussed in inter- national business textbooks, are key elements in successful conduct of inter- national business. For example, we noted the specificity, formality, plan- ning, and business protocol evident in

November/December 2001 109

[image:5.612.47.374.52.427.2]all the businesses, organizations, and

institutions visited.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Acculturation

Regretably, faculty often carry bias- es, sterotypical images, and mispercep- tions into their everyday activities. Awareness of such attitudes, inaccura- cies, and behaviors is critical, as facul- ty may perpetuate these misrepresenta- tions through the classroom. Specifically, in teaching and research- ing international subjects, faculty mem- bers must be mindful of how such bias- es may be transferred to their students and colleagues. Even short visits allow the individual to re-establish a direct contact and correct such perceptions and biases.

In the program presented, the partic- ipants were placed in contact with another culture in numerous situations, ranging from formal meetings with business and nonbusiness groups to in- home stays and local transportation set- tings. At the superficial level, it was dif- ficult, if not impossible, to attribute behaviors exhibited or the attitudes dis- played in a stereotypical manner. Though we may have construed stereo- types, the one-on-one interaction afforded by this experience allowed us

both to prove otherwise.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

As a part of a study group, the facul-

ty member has the opportunity to review his or her own attitudes and behaviors through a self-reporting mechanism. He or she is challenged to contemplate and compare what has been “learned” from published sources and prior experiences with current per- sonal observations. Here the individual can assess daily actions against his or her own feelings and compare the home-based decisionmaking approach with that of another culture. Keeping a written record allows the individual to build future experiential exercises and lectures and evaluate his or her attitudes over time.

A secondary, but important, aspect of

an international experience is the unob- trusive observation of the decisionmak- ing dynamics of students, whether as individuals or a group, in a foreign cul- ture. For example, after our group

returned to Tokyo, we were informed

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 10 Journal of Education for

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Businessthat the hostel closed its doors at 1O:OO p.m. sharp and would not unlock its doors under any circumstances until the next morning. A number of students

who had been experiencing Tokyo nightlife returned at 10:45 p.m. Despite their pleas, they were forced to sleep outside in a very light off/on rain in their dress clothes.

The next morning, the students attempted to decide why and who caused the delay in returning late. In the following days, the conflict was re- solved with one particular outcome-no one ever returned late again. Thus, cul- tural learning had taken place.

Other observations allowed for the comparison of our individualized, self- centered focus with the more group- centered focus found in Japan.

As we noted earlier, it is refreshing and rewarding to validate academic con- cepts and practices. However, in this experience we found ourselves to be academic and cultural neophytes. Though we had our expectations at the macrolevel, we were not prepared at all for what we experienced at the microlevel. Though previous success in teaching international business and pub- lishing in international journals had expanded the perceived academic prowess of at least one of us, first-hand

experience in international reality pro- vided an immediate and profound cogn- tive correction. In turn, this cogntive re- positioning has stimulated us to rethink our pedagogies and professional status and standards, as well as to introduce substantive and responsive change in our classes.

Academic Administration

Conclusion

Though not a high priority, experi- ence in academic administration is gained by participating faculty mem- bers. Such growth includes a greater un- derstanding of budget development, funding sources, grant preparation, schedule development, and operational issues and arrangements as well as direct interaction with foreign ad- ministrators and executives.

In turn, the experience should prove helpful to those facuty members who at some point would like to develop their own study-abroad educational experi- ence. Given the voluminous amount of preparatory administrative work that must be done, the experience may dis- courage some faculty members from such an endeavor.

Cognitive Repositioning

Our short-term international experi- ence affected at least one of us in the area identified as “cognitive reposition- ing,’’ though a more accurate label for it would be “dose of humility.” Confidence in one’s ability is an admirable quality and plays an integral role in classroom excellence. However, for some faculty, confidence may unintentionally progress or regress to academic arrogance. A short-term study-abroad experience can correct that malady by providing a major dose of academic humility.

The program described in this article is supportive of both faculty with prior experience living or working in another culture and those just entering the inter- national arena. Such a program offers specific opportunities for developing professional relationships and ties that can lead to ongoing research efforts. Subsequent to participation in this pro- gram, both of us have continued contact with others involved and have several research proposals underway. To stimu- late the student in class who has limited exposure or interest in international activities, the instructor should be able to “talk the talk” and make the “walk” real. A study-abroad program can pro- vide an edge to the faculty member at- tempting to tranfer to students the simi- larities and differencies of another culture.

Today, more so than ever before, it is absolutely critical that students and fac- ulty study and experience the interna- tional business environment. In addition to the learning that occurs from on-site visits and presentations, students and faculty will experience cultural diversi- ty at the macro- and microlevels. This acculturation process will reshape how both groups view the world, its people, and its marketplace. In the case of edu- cators, the international experience will provide the basis for developing new

and richer teaching and learning materi- als gleaned from direct visits with

representatives of industry, education,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

REFERENCE

Sewell, A. M. (1999). New frames

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

for an uniden-Kwok, C. C.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Y., Arpan, J.,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Folks, W. R., Jr.(1994). A global survey of international busi-

neSS education in the 1990s,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Internu-tional Business Studies. 25(3). 605-623. tified future. National Forum, 79(1), 2-3.

Muuka, G. N., Harrison, D. E.. & Hassan, S. (1999). International business in American MBA programs4an we silence the critics? Journal of Education f o r Business, 74(4),

and government in another country and participation in its daily activities. We hope that this form Of

SUGGESTED READINGS

Chronicle of Higher Education. (1997, September 12). Business schools promote international

ment will be embraced bv more busi- focus. but critics see more hvoe than substance. * a 237-242.

ness educators interested

ln

developing their international business educationA14-15. Sarathy, R. (1990). Internationalizing MBA edu-

cation: The role of short overseas programs. tionalize American higher education? Not Journal of Teaching in International Business, Altbach, P. G., & Peterson, P. M. (1998). Interna-

expertise. exactly. Change, 30(4), 36-40. 1(3/4), 101-1 18.

Advertise in the

Journal of

Education for Business

For more information please contact:

Alison Mayhew, Advertising Manager

Heldref Publications

1319 Eighteenth St. NW

Washington, DC 20036-1802

Phone:

(202)

296-6267

Fax:

(202)

293-6130