SU R VEY

Environmental tax reform: does it work? A survey of the

empirical evidence

Benoıˆt Bosquet *

T he W orld Bank,1818 H S treet, N W , W ashington, DC 20433, US A

R eceived 16 July 1999; received in revised form 15 F ebruary 2000; accepted 15 F ebruary 2000

Abstract

Environmental tax reform is the process of shifting the tax burden from employment, income and investment, to pollution, resource depletion and waste. Can environmental tax reform produce a double dividend — help the environment without hurting the economy? This paper reviews the practical experience and available modeling studies. It concludes that when environmental tax revenues are used to reduce payroll taxes, and if wage-price inflation is prevented, significant reductions in pollution, small gains in employment, and marginal gains or losses in production are likely in the short to medium term, while investments fall back and prices increase. R esults are less certain in the long term. They might be more positive if models selected welfare instead of production indicators for the second dividend, and if several important variables, such as wage rigidities and the feedback of environmental quality on production, were factored into simulations. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Environmental tax reform; M odeling studies; D ouble dividend

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. Introduction

Environmental tax reform (ETR ) represents an important development in environmental policy and public finance reform. ETR ‘entails a recon-sideration of the present tax system. The present system is aimed predominantly at taxing factors of production such as labor and capital. The basic idea of ecological taxation is a shift of tax burden

from these factors towards pollution and the use of natural resources’ (European Commission, 1997b). ETR shifts the tax burden from economic ‘goods’ to environmental ‘bads’, from what is socially desirable, such as employment, income and investment, to what is socially undesirable, such as pollution, resource depletion and waste. ETR is also called ecological tax reform, green tax reform, environmental fiscal reform, green tax swap, or green tax shifting (von Weizsa¨cker and Jesinghaus, 1992; G oulder, 1995; Carraro and Siniscalco, 1996; H amond et al., 1997; European Commission, 1997b; OECD , 1997b).

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-202-4771234; fax: + 1-202-4776391.

E -mail address:[email protected] (B. Bosquet)

R evenue recycling allows the government to carry out the operation in a revenue-neutral way, i.e. leaving total tax revenues unchanged. H ow-ever, ETR can be positive or revenue-negative, depending on how much tax revenue is recycled. In Europe, ETR is usually advertised under the banner of revenue neutrality, as the overall tax burden in these countries is already high, and additional taxation is economically damaging and politically unpalatable. H owever, F inland, Sweden, and to a lesser degree G ermany, have launched a revenue-negative ETR , thus re-ducing the overall tax burden on the economy.

In any case, the intention is to alter the system of incentives through lower taxes on ‘goods’, such as labor and capital, and higher taxes on ‘bads’. ETR , thus, creates the potential for a ‘double dividend’, i.e. an environmental improvement coupled with an economic benefit: revenues of environmental taxes could be used to cut distort-ing taxes on capital and labor and thus reduce the excess burden of the tax system, with positive consequences for employment and investment. This double dividend hypothesis has been the cause of intense academic and political contro-versy in recent years.

The enviromnental goal (first dividend) pursued by most governments consists of reducing carbon emissions. Among various measures to achieve these objectives, several European countries have adopted a carbon/energy tax. Such a tax discour-ages the use of fossil fuels that release carbon dioxide.

D ifferent directions than energy taxation are possible, however. Taxes on resource use, re-source rents, or the removal of environmentally harmful subsidies can also be used to finance an ETR .

On the tax reduction side, most countries have chosen to reduce employers’ social security contri-butions (SSC), one of the non-wage labor taxes paid by firms for each worker employed, because this tax directly affects the cost of labor.

The theoretical literature on ETR centers on the debate around the double dividend hypothe-sis. It tends to conclude that although a double dividend is possible, under neutral assumptions about preferences and the structure of the tax

system, it does not arise. F or the double dividend to arise, the tax system must be inefficient in a way that fully compensates for what otherwise would be the relative inefficiency of green taxes as a means of raising revenue.1F rom a review of the theoretical literature, it also appears that each ETR needs to be studied independently in order to determine the likelihood of a positive second dividend. A critical discussion of the theoretical arguments surrounding ETR can be found else-where (G oulder, 1995; Parry and Oates, 1998; Bosquet, 2000; Eissa et al., 2000).

M ost of the empirical literature to date has focused on carbon and energy taxation (Pezzey and Park, 1998). It consists of ex ante modeling studies of the economic and environmental impact of ETR . These studies are ex ante insofar as they attempt to predict the impact ETR will have and not, in what would be ex post fashion, the impact ETR has had. Several reviews of these studies exist, including European Commission (1992b), G oulder (1995), M ors (1995), Bruce et al. (1996), IN F R AS and ECOPLAN (1996), M ajocchi (1996), Baranzini et al. (2000), European Com-mission (2000a,b). These studies and reviews have concluded, with various degrees of assuredness, that ETR can, in certain conditions, achieve both environmental and economic improvements. H owever, most of these studies reviewed only a limited number of simulations.

This paper expands the scope of investigation by synthesizing the results of 139 simulations from 56 studies on the impact of ETR on CO2 emissions, employment, economic activity, invest-ments and consumer prices. In addition, several specific issues are addressed, including the distri-butional and sectoral impacts, and practical im-plementation of ETR .

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly describes the various explicit ETR pack-ages in existence, Section 3 summarizes the mod-eling evidence on the environmental and economic impacts of ETR , and Section 4 concludes.

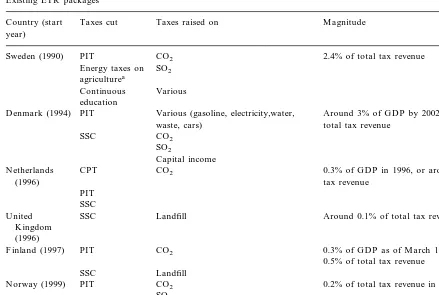

Table 1

Existing ETR packages Taxes cut

Country (start Taxes raised on M agnitude

year)

CO2

PIT 2.4% of total tax revenue

Sweden (1990)

Energy taxes on SO2

agriculturea

Continuous Various education

D enmark (1994) PIT Various (gasoline, electricity,water, Around 3% of G D P by 2002, or over 6% of total tax revenue

waste, cars) CO2

SSC

SO2

Capital income CPT

N etherlands CO2 0.3% of G D P in 1996, or around 0.5% of total

tax revenue (1996)

PIT SSC

Around 0.1% of total tax revenues in 1999 SSC

U nited Landfill

K ingdom (1996)

CO2

F inland (1997) PIT 0.3% of G D P as of M arch 1999, or around 0.5% of total tax revenue

Landfill SSC

CO2

PIT 0.2% of total tax revenue in 1999

N orway (1999)

SO2

D iesel oil

Petroleum products Around 1% of total tax revenue in 1999 G ermany (1999) SSC

Petroleum products Less than 0.1% of total tax revenue in 1999 SSC

Italy (1999)

aSweden’s year 2000 step towards ETR raised several energy taxes on industry and recycled the funds to reduce energy taxes on

agriculture and finance continuous education of the workforce. Sources of the data for financial magnitude of the tax shifts, OECD (1999), Jens H olger H elbo H ansen, D anish M inistry of Taxation, personal communication, F ebruary 9, 1999; D ominic H ogg, ECOTEC R esearch and Consulting, London, personal communication, M arch 15, 1999; Asa Johannesson, Swedish M inistry of F inance, personal communication, October 6, 1999; Timo Parkkinen, F innish M inistry of the Environment, personal communica-tion, F ebruary 15, 1999; K ai Schlegelmilch, G erman M inistry for the Environment, N ature Conservation and N uclear Safety, personal communication, F ebruary 25, 1999; Jacob van der Vaart, D utch M inistry of F inance, personal communication, F ebruary 15, 1999; The R oyal N orwegian M inistry of F inance and Customs.

2. ETR under way

So far, eight countries have embarked on ex-plicit ETR , namely, D enmark, F inland, G ermany, Italy, the N etherlands, N orway, Sweden and the U nited K ingdom (see Table 1).

Table 1 conveys several messages. F irst, explicit ETR is a recent phenomenon: all shifts have occurred in the past 10 years. Environmental taxes have admittedly existed for much longer and helped raise part of the government revenues, but explicit tax shifting is relatively new.

Second, the N ordic countries have been the

pioneers of the movement, although larger economies in western and southern Europe have since followed suit, including the U nited K ing-dom, G ermany and, to a lesser degree, Italy. M ore countries have announced their intention to launch an ETR , e.g. the F rench government re-vealed its plan to launch an environmentally moti-vated energy tax, the revenues of which would help cut labor taxes starting in 2001, subject to agreement at the European level (EN D S, 2000; Le M onde, 2000).

cut-ting non-wage labor costs in the form of social security contributions (SSC) paid by employers and employees, or personal income taxes (PIT). This focus on labor is due to the preoccupation with the high levels of unemployment in Europe. R educing the tax burden on labor increases incen-tives to work and hire.

F ourth, the financial magnitude of ETR pack-ages varies from small in the U nited K ingdom and Italy to significant in D enmark. Perhaps the main reason behind the limited magnitude of the shifts is the concern to preserve industrial compet-itiveness and not impose excessive harm on en-ergy-intensive sectors. A detailed account of the various ETR packages, including the taxes raised, the taxes cut, and the political economy of re-form, can be found elsewhere (H oerner and Bosquet, 2000). In addition, expositions of envi-ronmental taxes in European countries, some of which serve to finance ETR , can be found in EEA (1996), OECD (1997b,c, 1999), Baranzini et al. (2000) and especially European Commission (2000a).

F ifth, tax rises have mostly occurred in the energy sector given the need for curbing the risk of global climate change induced by greenhouse gases, in particular carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted from the combustion of fossil fuels, as well as the revenue potential of energy taxes compared with other green taxes. A carbon/energy tax has con-siderable revenue potential, which proves neces-sary to carry out substantial reductions in taxes on economic goods. F or example, of all the Swedish taxes with an explicitly environmental purpose, the CO2 tax is the one that collects the largest receipts, namely 2 – 3% of total tax revenue (Swedish EPA, 1997). The Stanford Energy M od-eling F orum suggests that carbon taxes or permit auctions could supply 15% of government rev-enues worldwide (R oodman, 1998).

It is worth noting that different directions than energy taxation are possible. Taxing resource use or resource and land rents, for instance, offers some potential. Taxes on resource use are singled out as further candidates for ETR as they induce materials internalization (first dividend) and have sufficient revenue potential to finance the reduc-tion of other taxes (second dividend). Specifically,

proposals are being studied for using taxes on sand, gravel, phosphorus, etc. (Axelsson, 1996; R epetto, 1996; Vermeend and van der Vaart, 1998; H M Customs and Excise, 1999; EN D S, 2000).

R esource rents are defined as profits in excess of the production cost of a resource. Crucial is that rents are excess profits and taxable surplus (G affney, 1994). Taxing rents is neutral as it does not deter economic activity, i.e. rental taxes are neutral or not distortionary (Tideman and Plass-man, 1998). The potential of taxing land and resource rents is considerable. A number of economists since the Physiocrats have even claimed that a comprehensive system of taxing land and resource rents could finance most public expenditures (Quesnay, 1756; R icardo, 1817; G eorge, 1879; Tideman, 1994). If appropriate rental payments were imposed, large revenues could become available to reduce distortionary taxes on labor and capital. It is estimated taxes on land, for instance, could raise over 70% of govern-ment revenues (G affney, 1996).

Shifting taxes to resource rents suggests an indirect approach to ETR . Since taxes on rents capture excess profits, they do not affect price levels. As resource prices remain unchanged, rent taxes do not create any immediate incentives for resource conservation. They would foster the sec-ond dividend, but do little if anything about the first (Bento and R ajkumar, 1998; D urning and Bauman, 1998; Bovenberg and G oulder, 2000).

Pure taxes on rent are not commonly found, however. Their indifference with respect to envi-ronmental quality explains why they are not de-ployed as part of existing ETR . Another difficulty has to do with estimating the rent. The produc-tion cost of a resource includes both current and capital costs, which may be hard to calculate accurately. A third obstacle is that natural re-source rents are usually grabbed by powerful in-terests opposing increases in taxation.

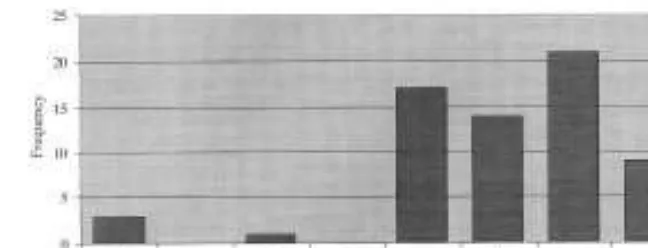

F ig. 1. Predicted impact on carbon emissions (bassed upon 67 simulations; 64 simulations did not return data; one outlier was excluded (−45%)).−5 means−5.0% impact B0% of reference CO2emissions scenario.

K ent (1998) put the estimate at over a trillion dollars a year.

3. Modeling evidence

The evidence from 139 simulations coming from 56 different studies is synthesized below. These simulations conceal a great variety of mod-eling techniques, with respect to model type (par-tial equilibrium, computable general equilibrium, macroeconomic, input – output, etc.) and assump-tions (concerning the phase-in of the tax, its na-tional or internana-tional scope, the substitutability among factors of production, price adjustment mechanisms, recycling of income, labor market conditions, etc.). This variety and the large num-ber of simulations rule out a unidirectional bias in the results.

These 139 simulations are the ones available to the author as of April 2000.2 F or the purpose of the graphical presentation of results, simulations that did not return results on the type of revenue recycling or the specific variable under examina-tion were excluded, as were outliers, i.e. single data points in their class at either tail of the distribution. This reduces the number of simula-tions actually reviewed to 131.

3.1. Is there a first di6idend?

U sing carbon emission reductions as the indica-tor of environmental effectiveness, ETR appears to influence the environment positively. F ig. 1 plots the results of 67 simulations on reductions of CO2emissions. R esults are organized in classes of 5%. F or example, class ‘−35’ includes values comprised between −35 and −31%, i.e. a reduc-tion of 31 – 35% compared with baseline-scenario emissions. 56 simulations (84%) return reductions in emissions. The mode is at the ‘−5’ class.

In support of these predictions, some ex post assessments have been conducted for the effective-ness of N orwegian and Swedish carbon taxes. One source reports that the N orwegian carbon tax is estimated to have achieved a 3 – 4% reduction in the carbon emissions of stationary sources in the manufacturing and services sectors, as well as stationary and mobile sources of households, to-gether representing around 40% of total CO2 emissions in N orway, over the period 1991 – 1993 (Larsen and N esbakken, 1997). Similarly, the Swedish carbon tax is estimated to have helped reduce carbon emissions, although no quantitative estimate is available (Swedish EPA, 1997).

3.2. Is there a second di6idend?

The second (economic) dividend is traditionally defined in terms of welfare (utility) or employ-ment. Theoretical studies have tended to focus on welfare, while in numerical models employment is

2Interested readers can request the table containing the

a more concrete and measurable concept. The distinction matters as changes in welfare and em-ployment do not necessarily coincide. Employ-ment creation, or the reduction in unemployEmploy-ment, for example, does not mean that welfare has increased. Therefore, an employment double dend might be achieved without a welfare divi-dend. Conversely, welfare could increase without translating into employment gains.

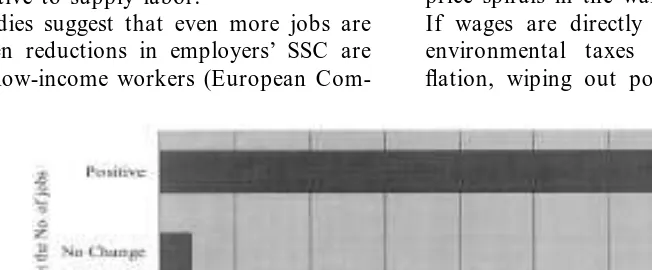

3.2.1. Employment

F ig. 2 presents employment data as a tri-chotomy (positive, negative or no change). Sev-enty-five simulations (73%) predict that ETR will help create jobs.

The weight of evidence from Belgium (Bossier et al., 1993a), D enmark (D anish F inance M istry, 1994), F inland (F innish Environment M in-istry 1994), G ermany (R IW, 1999), the N etherlands (CPB, 1997), the U nited K ingdom (Tindale and H oltham, 1996), as well as Europe as a whole (Standaert, 1992; Baron et al., 1996) suggests that the best results in terms of employ-ment are obtained when recycling occurs through cuts in SSC. This is because employers’ SSC directly influence the price of labor; the higher employers’ SSC, the more costly it is to hire labor, similarly, the higher employees’ SSC, the greater the disincentive to supply labor.

Some studies suggest that even more jobs are created when reductions in employers’ SSC are targeted at low-income workers (European

Com-mission, 1994; IN F R AS and ECOPLAN , 1996). The European unemployed consist mostly of low-income and low-productivity workers, whose cost elasticity of demand is greater than other workers’. Social charges and income taxes (the ‘tax wedge’), together with minimum wage ar-rangements, therefore, penalize primarily those workers by making them unproductive in times of production cost increases. In addition, low-in-come labor tends to be a good substitute for energy and capital and the elasticity of labor supply is the highest at low-income levels. R educ-ing SSC, therefore, encourages substitution of low-wage, low-productivity workers for high-wage high-productivity workers, in addition to a gen-eral shift to a more labor-intensive economy (Bossier et al., 1993b; European Commission, 1993; M ors, 1995).

One important caveat is that for employment gains to materialize, the labor market must be flexible (Proost and Van R egemorter, 1992; Stan-daert, 1992; Beaumais and Bre´chet, 1993; Eu-ropean Commission, 1993; F innish Environment M inistry, 1994; Bossier and Bre´chet, 1995; M ors, 1995; D on, 1996; IN F R AS and ECOPLAN , 1996; N orwegian G reen Tax Commission, 1996; G reenpeace and D IW, 1997; R IW, 1999). M odels underscore the need for preventing wage-price spirals in the wake of environmental taxes. If wages are directly linked to the price level, environmental taxes risk translating into in-flation, wiping out potential employment gains.

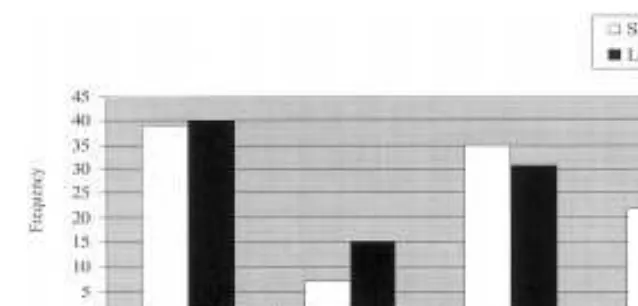

F ig. 3. Impact on time horizon. Based upon 46 short- to medium-term simulations of employment impact, 55 long-term simulations of employment impact, 57 short- to medium-term simulaaations of G D P impact, and 72 long-term simulations of G D P impact. ‘Empl 0 or +’ means positive or zero employment effect; ‘Empl −’ means negative employment effect; ‘G D P 0 or +’ means positive or zero G D P effect; ‘G D P −’ means negative G D P effect. Short- to medium-term means less than 10 years; long-term means 10 years or more.

Indeed, certain models suggest that sharp in-creases in the real wage rate on account of higher energy and consumer prices must be prevented. The tax increase cannot be fully passed on to sales prices as the rest of the world is prepared to absorb only a fraction of the price increase. The rest must, thus, be split between domestic capital and labor. F or jobs to be created, most of the residual cost increase will be borne by labor in the form of reductions in real wage costs. If, instead, wages are rigid, high losses of employment may result.

The remarks above are aptly encapsulated in the conclusion that ‘if a wage-price spiral can be avoided then a CO2-energy tax has the potential of improving employment if the revenues are used for a cut in SSC… a noticeable although not

spectacular increase in employment on the order of

0.5% can be ex pected’ (European Commission, 1993).

It was suggested earlier in the literature that the type of model used in the simulation might bias the sign of the second dividend. In particular, macroeconomic models would return more posi-tive results than general equilibrium models (M abey and N ixon, 1997). This paper contradicts that finding: out of a total of 77 macroeconomic simulations, 58 (75%) predict a positive or zero impact on employment. This contrasts with a

total of 24 general equilibrium simulations, out of which 21 (88%) predict a positive or zero impact. The same conclusion is arrived at when only the European simulations are analyzed (H oerner and Bosquet, 2000).

The mode of recycling of environmental tax revenue plays a more significant role than the model type. F ifty four percent of the simulations assuming recycling through reductions in PIT forecast a positive or zero effect on employment, while as many as 86% of the simulations assuming recycling through reductions in SSC forecast a positive or zero effect. Other recycling modes are not available in sufficient numbers to draw mean-ingful conclusions.

F inally, the time horizon of the simulation ap-pears to influence results as well. F ig. 3 suggests that long-term simulations, i.e. those with a time horizon equal to or greater than 10 years, are more likely to predict a negative effect on employ-ment than short- to medium-term simulations.

3.2.2. Economic acti6ity

argue that these come at the expense of aggregate production and production growth.

F ig. 4 plots 119 data points on ETR ’s impact on activity levels. Sixty-one simulations (51%) predict a G D P loss, and the mode is at the ‘−0.5’ class. Seventy-one percent predict an impact be-tween −0.5 and +0.5% of G D P, i.e. a change of less than 0.5% of G D P relative to the reference scenario. This is small given the uncertainty em-bedded in the reference scenario itself.

This paper again challenges earlier suggestions that macroeconomic models are more likely to forecast positive effects than general equilibrium models: out of a total of 77 macroeconomic simu-lations, 38 (49%) predict a positive impact on G D P. This contrasts with a total of 38 general equilibrium simulations, out of which 22 (58%) predict a positive impact.

Chronologically, a positive effect on production (and employment) might occur as follows, assum-ing that the environmental tax increase produces its effect faster than reductions in labor costs. At first, the new taxes raise consumer prices and wages, which depresses activity because of a re-duction in domestic and external demand. After some time, cuts in SSC more than offset the negative impact on demand, leading to gains in employment, followed by rises in demand and, thus, G D P.

As in the case of employment, the mode of recycling of environmental tax revenue plays a more significant role than the model type. As many as 65% of the simulations assuming cuts in

SSC returned positive results, compared to merely 23% for reductions in PIT. The reason is that reductions in SSC have a favorable effect on firms’ profitability. Assume a carbon tax imposed on business, for instance. If employers’ SSC are reduced by the total carbon tax revenue, business is more than fully compensated for the tax in-crease. Indeed, firms assimilate the tax, adjust their production levels or input mixes, then pass on the remaining cost increase to consumers. F irms will not only hire more labor, but also boost their investments and production. The same positive effects cannot be expected with the VAT or PIT: VAT is in principle neutral to firms and falls on final consumers, whereas the PIT affects only individuals.

Again, the time perspective seems to matter. As F ig. 3 suggests, a less favorable impact on G D P is more likely in the long term.

The problems with G D P have been amply dis-cussed in the ecological economics literature. They help explain why G D P and G D P growth do not inform on the second dividend. G D P fails to measure long-term sustainable growth and welfare. Beyond a certain level, growth may ac-tually make us poorer, as the costs of production increase faster than the benefits. Although the flows of services and goods produced are posi-tive, the stocks of natural, human, and man-made capital may become depleted. F rom a welfare point of view, G D P presents an incon-gruous sum of expenditures, combining, for

F ig. 4. Predicted impact on output. Based upon 120 simulations; 7 simulations did not return data; four outliers were excluded (−5,

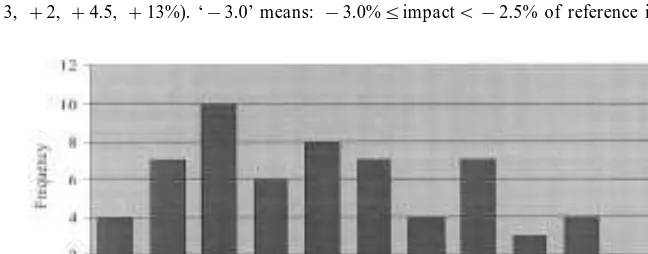

F ig. 5. Predicted impact on investments. Based upon 58 simulations; 67 simulations did not return data; six outliers were excluded (−8, −6.5, −3, +2, +4.5, +13%). ‘−3.0’ means:−3.0%5impactB−2.5% of reference investments by firms etc.

F ig. 6. Predicted impact on prices. Based upon 64 simulations; 66 simulations did not return data; one outlier was excluded (−1%) ‘−1.0’ means−1.0%5impactB−0.5% of reference CPI, etc.. N egative impact means deflation, positive impact means inflation. example, such ‘goods’ as labor incomes or the

improvement of health and education, and the defensive expenditures incurred to fight such ‘bads’ as pollution and car accidents (Boulding, 1966; El Serafy and Lutz, 1989; D aly, 1993a,b).

Instead of production and G D P, a numerical indicator of welfare might be used to inform on the second dividend. This could be achieved by the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), the Sustainable Social N et N ational Product (SSN N P), or the G enuine Progress Indi-cator (G PI) (El Serafy and Lutz, 1989; D aly and Cobb, 1994; D aly, 1996; R owe and Anielski, 1999). One can speculate that the predicted effect of ETR on the second dividend would be better than using G D P.

It should be noted, however, that using such an index would blur, indeed void of its substance, the

distinction between the first and the second divi-dend, if only because reductions in carbon emis-sions enter as a plus in computing the second dividend. Such an index would instead inform on the effect of ETR without distinguishing between environmental and non-environmental benefits.

3.2.3. In6estments

3.2.4. Prices

In F ig. 6, 56 simulations (94%) predict rises in the consumer price index (CPI). This is due to the limited capacity of the economy to substitute away from carbon-intensive processes and products. Even if the carbon or energy tax is imposed on producers, these will pass at least part of it on to consumers, resulting in rises in the CPI. Inflation might be prevented if VAT was reduced. But, as explained earlier, recycling the carbon tax revenue through cuts in SSC is generally preferred to VAT. In this preferred option, the unit cost of labor to firms decreases, but the number of jobs rises. The reduction in labor costs will, therefore, not compen-sate for the increase in energy costs, unless a complete substitution away from fossil fuels took place, which is considered impossible in the short-to medium-term.

3.3. Competiti6eness

N ationally, empirical evidence suggests that en-ergy-intensive sectors will be the most affected, but that labor-intensive sectors will benefit (Standaert, 1992; D anish F inance M inistry, 1995; N orwegian G reen Tax Commission, 1996; H arrison and K ristro¨m, 1997; SOU 1997; Vermeend and van der Vaart, 1998).

At the European level, the overall economic impact of energy taxation is likely to be modest. F irst, the majority of manufacturing branches have a direct energy cost share between 0 and 5% of total production costs. A few branches are energy-inten-sive, with a direct energy cost share between 10 and 20%. H owever, employment in those sectors repre-sents less than 10% of total industrial employment (European Commission, 1992a). Second, with the exception of the energy sector, most firms should be able to alleviate the impact of the energy tax by switching to other energy sources or investing in more energy-efficient equipment (European Com-mission, 1997a). Third, compensations to nega-tively affected sectors may include border-price adjustments, refunds, exemptions, and subsidies. On balance, some sectors or sub-sectors may be hurt, but the objective pursued is a structural reform towards a more sustainable, less energy-intensive economy (Ekins, 1999; Ekins and Speck, 1999).

An important variable in determining the inter-national competitiveness impact of ETR is capital mobility. The more mobile capital, the greater the risk of relocation of firms abroad as a result of the imposition of unilateral environmental taxes (de Wit, 1995). An international tax may alleviate the burden on domestic industry (CPB, 1992; F innish Environment M inistry, 1994; European Commis-sion, 2000b), which points to the need for interna-tional coordination. As recent developments suggest, however, neither the U nited N ations under the K yoto Protocol to the F ramework Convention on Climate Change nor the European U nion are moving closer to the adoption of an international carbon tax. Progressive countries are thus left with little choice but to grant numerous refunds and reductions to their industries by way of protection, a move which detracts from the environmental effectiveness of ETR .

F urthermore, even with full international coordi-nation and assuming no capital relocation, some loss in competitiveness can be expected for energy-intensive industries (K oopman, 1994). In addition, the imposition of a tax on an international scale may slow down economic activity and spark off infla-tionary tendencies in a wider group of countries. In a small open economy, this could further worsen economic performance (Bossier and Bre´chet, 1995). F inally, international fiscal harmonization may even thwart ETR . Some options for ETR are barred by international rules, including recycling revenues through cuts in VAT: in Europe, VAT rates are harmonized across the M ember States of the Eu-ropean U nion and unilateral cuts in national VAT rates are considered an unfair advantage to domes-tic producers.

3.4. Distribution

progres-sive. In D enmark, Ireland and the U nited K ing-dom, it would be the most regressive (Symons and Proops, 1998). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1996) reviewed several studies, four of which suggest that carbon taxes are re-gressive, and three suggest a proportional or pro-gressive impact (Bruce et al., 1996). D ifferent country studies produce equally ambiguous re-sults (Baranzini et al., 2000).

With revenue recycling and special poverty alle-viation measures, the impact of energy taxes could be considerably altered and softened. In G er-many, ETR would benefit all households, but those with children more than those without (R IW, 1999). In the N etherlands, energy tax relief is predicted to alleviate the impact on households with average energy consumption, while addi-tional compensatory measures protect the particu-larly vulnerable, energy-dependent, members of society (Vermeend and van der Vaart, 1998). These measures have contributed to the tax’s ac-ceptability (Ekins, 1999).

Besides the direct impact of higher energy prices, the poor will benefit from higher employ-ment if CO2/energy tax revenues are recycled through reductions in employers’ SSC targeted at low-income jobs. In that case, the tax burden will be shifted to those outside the workforce. This raises an additional equity issue: how to protect the vulnerable members of society who are not in the workforce, including pensioners, the disabled, etc.?

4. Conclusions

Substantial empirical evidence exists on the pre-dicted effect of ETR . This paper has reviewed 139 modeling simulations. The general findings are that reductions in carbon emissions may be sig-nificant, marginal gains in employment and mar-ginal gains or losses in activity may be recorded in the short- to medium-term, and investments de-crease and prices inde-crease moderately.

With likely emissions reductions and gains in employment, the trend corroborates the hypothe-sis that ETR can, under certain conditions and subject to the limits inherent to modeling

tech-niques, achieve both environmental and economic improvements. In particular, when environmental tax revenues are redistributed to cut distorting taxes on labor, such as SSC, environmental quality improves, small gains tend to be registered in the number of jobs and output in non-polluting sec-tors. R esults are more ambiguous in the long run. ETR may cause some harm to energy-intensive sectors, but such sectoral changes may be neces-sary for the economy to become more energy-effi-cient and achieve the desired reductions in carbon emissions.

Environmental taxes may disproportionately hurt households that spend a greater share of their income on ‘dirty’ goods, but revenue recy-cling and compensatory measures targeted mea-sures at vulnerable elements of society abate this effect.

1998). F ifth, the taxes modeled so far have been relatively small energy and carbon taxes, the im-pact of which is predicted to be moderate. But small causes have small effects (OECD , 1997b). If, in addition to higher energy and carbon taxes, ETR included taxes on land and resource rents, far greater revenue may become available to re-duce other distortionary taxes. In the latter case, a higher second dividend would probably come at the expense of the first dividend.

Simulation results remain uncertain and should not serve as the only guide for policy-making, for several reasons. F irst, no model is capable of accurately predicting the impact of an elaborate ETR package or reflecting all the subtleties of an economy. Second, all models of economic impact are ex ante studies. Ex post interpretation is noto-riously difficult because of the existence of myriad confounding factors and the small size of environ-mentally motivated changes relative to other fac-tors (M ors, 1995; OECD , 1997a,c). Third, given the error margins involved in assumptions, the size of some of the predicted gains and losses may not be correct.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the helpful comments pro-vided by Lawrence G oulder, Andrew H oerner, H erman D aly, Asa Johannesson, Timo Parkki-nen, K ai Schlegelmilch, the R oyal N orwegian M inistry of F inance and Customs, and three anonymous reviewers. All remaining mistakes and omissions are mine.

References

Axelsson, S., 1996. Ecological Tax R eform: Tax Shift, A Tool to R educe U nemployment and Improve the Environment. N aturskydds fo¨reningen, Stockholm.

Baranzini, A., G oldemberg, J., Speck, S., 2000. A future for carbon taxes. Ecol. Econ. 32, 3.

Baron, R ., D ower, R ., M orgenstern, D ., M artinez-Lopez, M ., Johansen, H ., Johnsen, T., Alfsen, K ., Ezban, R ., G ron-lykke, M ., 1996. Policies and M easures for Common Ac-tion, Annex I Experts G roup on the U N F CCC. International Energy Agency, Paris.

Beaumais, O., Bre´chet, T., 1993. La Strate´gie communautaire de re´gulation de l’effet de serre: quels enjeux pour la F rance? L’analyse des mode`les H erme`s-M idas. ER ASM E, Ecole centrale and U niversite´ de Paris I, Paris.

Bento, A.M ., R ajkumar, A.S., 1998. R ethinking the N ature of the D ouble D ividend D ebate. World Congress of Environ-mental and R esource Economists. F ondazione Eni Enrico M attei, M ilan.

Bernow, S., R udkevich, A., R uth, M ., Peters, I., 1998. A Pragmatic CG E model for assessing the influence of model structure and assumptions in climate change policy analy-sis. Tellus Study N o. 96-190. Tellus Institute, Arlington, VA.

Bosquet, B., 2000. Environmental tax reform: a theoretical review. U niversity of M aryland School of Public Affairs, U npublished.

Bossier, F ., Bre´chet, T., 1995. A fiscal reform for increasing employment and mitigating CO2emissions in Europe.

En-ergy Policy 23 9, 789 – 798.

Bossier, F ., Bre´chet, T., G ouze´e, N ., 1993a. F aire face au changement climatique: Les politiques de lutte contre le renforcement de l’effet de serre. Planning paper N o. 63. Bureau du Plan, Brussels.

Bossier, F ., Bracke, I., Bre´chet, T., Lemiale, L., Streel, C., Van Brusselen, P., Zagame´, P., 1993b. U n rede´ploiement fiscal au service de l’emploi en Europe: re´duction du couˆt salarial finance´e par une taxe CO2/e´nergie. Planning paper N o.65.

Bureau du Plan, Brussels.

Boulding, K .E., 1966. The economics of the coming spaceship earth. In: Jarrett, H . (Ed.), Environmental Quality in a G rowing Economy. R esources for the F uture. Johns H op-kins U niversity Press, Baltimore, M D , pp. 3 – 14. Bovenberg, A.L., G oulder, L.H ., 2000. Environmental

taxa-tion. In: Auerbach, A., F eldstein, M . (Eds.), H andbook of Public Economics (forthcoming), second ed. N orth H ol-land, N ew York.

Bruce, J.P., Lee H ., H aites, E.F . (Eds.), Climate Change 1995: Economic and Social D imensions of Climate Change. Con-tributions of Working G roup III to the Second Assessment R eport of the IPCC 1996, Cambridge U niversity Press, N ew York.

Carraro, C., Siniscalco, D . (Eds.), 1996. Environmental F iscal R eform and U nemployment. K luwer Academic Publishers, D ordrecht, The N etherlands.

Carraro, C., G aleotti, M ., G allo, M ., 1995. Environmental Taxation and U nemployment: Some Evidence on the ‘‘D ouble D ividend H ypothesis’’ in Europe. N ota di La-voro, Environmental Policy N o. 34.95, F ondazione Eni Enrico M attei, M ilan.

Centraal Planbureau, 1992. Economic Long-Term Conse-quences of Energy Taxation. Working Paper N o. 43, CPB, The H ague.

Centraal Planbureau, 1997. G reening Taxes and Energy: Ef-fects of Increased Energy Taxes and Selective Exemptions. Working Paper N o. 96. CPB, The H ague.

Valuing the Earth: Economics Ecology, Ethics. M IT Press, Cambridge, M A, pp. 11 – 47.

D aly, H .E., 1993b. Sustainable growth: an impossibility theo-rem. In: D aly, H .E., Townsend, K .N . Jr (Eds.), Valuing the Earth: Economics Ecology, Ethics. M IT Press, Cam-bridge, M A, pp. 267 – 273.

D aly, H .E., 1996. Beyond G rowth: The Economics of Sus-tainable D evelopment. Beacon Press, Boston.

D aly, H .E., Cobb, J.B. Jr, 1994. F or the Common G ood, second ed. Beacon Press, Boston.

D anish F inance M inistry, 1994. G rønne afgifter og erhver-vene. D anish F inance M inistry, Copenhagen.

D anish F inance M inistry, 1995. Energy Tax on Industry in D enmark. D anish F inance M inistry, Copenhagen. D eCanio, S.J., 1997. The Economics of Climate Change.

R edefining Progress, San F rancisco.

de Wit, G ., 1995. Belastingverschuiving en werkgelegenheid. Economisch Statistische Berichten 8, 134 – 137.

D on, H ., 1996. Tax reform and job creation. R eport no. 1996/4, CPB, The H ague.

D urning, A.T., Bauman, Y., 1998. Tax Shift: H ow to H elp the Economy, Improve the Environment, and G et the Tax M an off Our Backs. R eport no. 7, N orthwest Envi-ronment Watch, Seattle.

European Environment Agency, 1996. Environmental Taxes: Implementation and Environmental Effectiveness. EEA, Copenhagen.

Eissa, N ., Blundell, R ., Blow, L., 2000. Employment, Envi-ronmental Taxes, and Income Taxes. R edefining Progress, San F rancisco, in press.

Ekins, R ., 1999. European environmental taxes and charges: recent experience, issues and trends. Ecol. Econ. 31, 39 – 62.

Ekins, R ., Speck, S., 1999. Competitiveness and exemptions from environmental taxes in Europe. Environ. R esour. Econ. 13, 369 – 396.

El Serafy, S., Lutz, E., 1989. Environmental and resource accounting: an overview. In: Ahmad, Y., El Serafy, S., Lutz, E. (Eds.), Environmental Accounting for Sustain-able D evelopment. The World Bank, Washington, D C, pp. 1 – 7.

Environmental N ews D aily Service, London, 2000. F rance Adopts N ational Climate Change Plan, January 20. European Commission, 1992a. European Economy: The

Cli-mate Challenge, Economic Aspects of the Community’s Strategy for Limiting CO2 Emissions, Statistical Annex.

Long-Term M acroeconomic Series N o. 51. European Commission, D irectorate-G eneral II, Brussels.

European Commission, 1992b. The Economics of Limiting CO2 Emissions. Special Edition N o. 1. European

Com-mission, Brussels.

European Commission, 1993. Taxation, Employment and En-vironment: F iscal R eform for R educing U nemployment. European Commission, Brussels.

European Commission, 1994. Croissance, compe´titivite´, em-ploi: les de´fis et les pistes pour entrer dans le XXIe sie´cle. White Book. European Commission, Brussels.

European Commission, 1997a. Pre´sentation du nouveau dis-positif communautaire de taxation des produits e´nerge´-tiques: evaluation de l’impact de la proposition. Working D ocument N o. SEC(97) 1026/2. European Commission, Brussels.

European Commission, 1997b. Tax Provisions with a Poten-tial Impact on Environmental Protection. Office for Offi-cial Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

European Commission, 2000a. D atabase on Enviromnental Taxes in the European U nion M ember States, plus N or-way and Switzerland: Evaluation of Environmental Ef-fects of Environmental Taxes. European Commission’s website: http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/enveco/

database.htm.

European Commission, 2000b. Study on the R elationship between Environmental/Energy Taxation and Employment Creation. European Commission, Brussels, in press. F innish Environment M inistry, 1994. Interim R eport of the

Environmental Economics Committee. F innish Environ-ment M inistry, H elsinki.

F ullerton, D ., M etcalf, G .E., 1998. Environmental Taxes and the D ouble-D ividend H ypothesis: D id You R eally Expect Something for N othing? Chicago-K ent Law R eview, 73. G affney, M ., 1994. Land as a distinctive factor of production.

In: Tideman, N . (Ed.), Land and Taxation. Shepheard-Walwyn, London, pp. 38 – 102.

G affney, M ., 1996. Land R ent in a Tax-F ree Society. Outline of R emarks at M oscow Congress, M ay 21, U npublished. G eorge, H ., 1879. Progress and Poverty, 1992 edn., R obert

Schalkenbach F oundation, N ew York.

G oulder, L.H ., 1995. Environmental taxation and the double dividend: a reader’s guide. Int. Tax Public F inance 2 (2), 157 – 183.

G oulder, L.H ., Schneider, S.H ., 1999. Induced technological change, crowding and the attractiveness of CO2abatement

policies. R esour. Energy Econ. 21, 211 – 253.

G reenpeace and D eutsches Institut fu¨r Wirtschaftforschung, 1997. The Price of Energy. D artmouth Publishing Com-pany, Aldershot, U K .

H amond, M .J., D eCano, S.J., D uxbury, P., Sanstad, A.H ., Stinson, C.H ., 1997. Tax Waste, N ot Work: H ow Chang-ing What We Tax Can Lead to a Stronger Economy and a Cleaner Environment. R edefining Progress, San F rancisco. H arrison, G .W., K ristro¨m, B., 1997. Carbon Taxes in Sweden.

U niversity of U mea˚, U mea˚, Sweden.

H M Customs and Excise, 1999. Potential Aggregates Tax, London.

H oerner, J.A., Bosquet, B., 2000. F undamental Environmental Tax R eform: The European Experience. Center for a Sus-tainable Economy, Washington, D C, in press.

IN F R AS and ECOPLAN , 1996. Economic Impact Analysis of Ecotax Proposals: Comparative Analysis of M odelling R e-sults. European Commission, D irectorate-G eneral XII, Brussels.

N o. II/563/94-EN , European Commission, D irectorate-G eneral II, Brussels.

Larsen, B.M ., N esbakken, R ., 1997. N orwegian emissions of CO2 1987 – 1994: a study of some effects of the CO2tax.

Environ. R esour. Econ. 9 (3), 275 – 290.

Lemiale, L., Zagame´, P., 1998. Taxation de l’e´nergie, effic-ience e´nerge´tique et nouvelles technologies: les effets macroe´conomiques pour six pays de l’U nion europe´enne. In: Schubert, K ., Zagame´, P. (Eds.), L’environment: U ne nouvelle dimension de l’analyse e´conomique. Vuibert, Paris, pp. 353 – 370.

Le M onde, 2000. Le plan pre´voit l’instauration d’une e´cotaxe. January 20.

M abey, N ., N ixon, J., 1997. Are environmental taxes a free lunch? Issues in modelling the macroeconomic effects of carbon taxes. Energy Econ. 19, 29 – 56.

M ajocchi, A., 1996. G reen fiscal reform and employment: a survey. Environ. R esour. Econ. 8, 375 – 397.

M ors, M ., 1995. Employment, revenues and resource taxes: genuine link or spurious coalition? Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 5 (2/3), 118 – 134.

M yers, N ., K ent, J., 1998. Perverse subsidies: Tax $s U nder-cutting Our Economies and Environments Alike. Interna-tional Institute for Sustainable D evelopment, Oxford. N orwegian G reen Tax Commission, 1996. Policies for a Better

Environment and H igh Employment. N orwegian M inistry of F inance and Customs, Oslo.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and D evelopment, 1997a. Environmental Policies and Employment. OECD , Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and D evelopment, 1997b. Environmental Taxes and G reen Tax R eform. OECD , Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and D evelopment, 1997c. Evaluating Economic Instruments for Environmen-tal Policy. OECD , Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and D evelopment, 1999. Economic Instruments for Pollution Control and N atural R esources M anagement in OECD Countries: A Survey. OECD , Paris.

Parry, I.W.H ., Oates, W.E., 1998. Policy Analysis in a Second Best World. D iscussion Paper N o. 98-48. R esources for the F uture, Washington, D C.

Pezzey, J.C.V., Park, A., 1998. R eflections on the double dividend debate: the importance of interest groups and information costs. Environ. R esour. Econ. 11 (3-4), 539 – 555.

Porter, M .E., van der Linde, C., 1995. Towards a new concep-tion of the environment competitiveness relaconcep-tionship. J. Econ. Perspectives 9 (4), 97 – 118.

Proost, S., Van R egemorter, D ., 1992. Carbon Taxes in the European Community: D esign of Tax Policies and their

Welfare Impacts. In: European Commission (Ed.), The Economics of Limiting CO2, Emissions, Special Edition

N o. 1. European Commission, Brussels, pp. 91 – 124. Quesnay, F ., 1756. The general maxims for the economic

government of an agricultural kingdom. In: M eek, R . (Ed.), The Economics of Physiocracy. H arvard U niversity Press, Cambridge, M A, pp. 231 – 262.

R epetto, R ., 1996. Shifting taxes from value added to material inputs. In: Carraro, C., Siniscalco, D . (Eds.), Environmen-tal F iscal R eform and U nemployment. K luwer Academic Publishers, D ordrecht, The N etherlands, pp. 53 – 72. R icardo, D ., 1817. The Principles of Political Economy and

Taxation, 1911 edn., E.P. D utton, N ew York.

R heinisch-Westfa¨lisches Institut fu¨r Wirtschaftsforschung, 1999. Stellingnahme zum Entwurf eines G esetzes zum Ein-stieg in die o¨kologische Steuerreform. R IW, Essen, G er-many.

R oodman, D .M ., 1998. The N atural Wealth of N ations: H ar-nessing the M arket for the Environment. W.W. N orton and Company, N ew York.

R owe, J., Anielski, M ., 1999. The G enuine Progress Indicator. R edefining Progress, San F rancisco.

Statens offentliga utredningar, 1997. Skatter, miljo¨ och syssel-sa¨tning: Slutbeta¨nkande av Skatteva¨xlingskommite´n. Swedish F inance M inistry, Stockholm.

Standaert, S., 1992. The M acro-Sectoral Effects of an EC-Wide Energy Tax: Simulation Experiments for 1993-2005. In: European Commission (Ed.), The Economics of Limit-ing CO2, Emissions. Special Edition N o. 1, European

Commission, Brussels, pp. 127 – 151.

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 1997. Envirom-nental Taxes in Sweden: Economic Instruments of Envi-ronmental Policy. R eport N o. 4745. Swedish EPA, Stockholm.

Symons, E., Proops, J., 1998. The D istributional Implications of Pollution Taxes on European F amilies. K eele U niver-sity, K eele, U K .

Tideman, N ., 1994. The economics of efficient taxes on land. In: Tideman, N . (Ed.), Land and Taxation. Shepheard-Walwyn, London, pp. 103 – 140.

Tideman, N ., Plassman, F ., 1998. Taxed out of work and wealth: the costs of taxing labor and capital. In: H arrison, F . (Ed.), The Losses of N ations: D eadweight Politics ver-sus Public R ent D ividends. Othila Press, London, pp. 146 – 174.

Tindale, S., H oltham, G ., 1996. G reen Tax R eform: Pollution Payments and Labour Tax Cuts. Institute for Public Policy R esearch, London.

Vermeend, W., van der Vaart, J., 1998. G reening Taxes: The D utch M odel. K luwer, D eventer, N etherlands.

von Weizsa¨cker, E.U ., Jesinghaus, J., 1992. Ecological Tax R eform. Zed Books, London.