Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Comparative Study of Ethical Beliefs of Master

of Business Administration Students in the United

States With Those In Hong Kong

Mohammed Rawwas , Ziad Swaidan & Hans Isakson

To cite this article: Mohammed Rawwas , Ziad Swaidan & Hans Isakson (2007) A Comparative Study of Ethical Beliefs of Master of Business Administration Students in the United States With Those In Hong Kong, Journal of Education for Business, 82:3, 146-158, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.82.3.146-158

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.82.3.146-158

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 39

View related articles

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors

investigated personal beliefs and values and

opportunism variables that might contribute

to the academic dishonesty of American and

Hong Kong master of business

administra-tion (MBA) students. They also compared

American and Hong Kong MBA students

with respect to their personal beliefs and

val-ues, opportunism, and academic dishonesty

variables. Results showed that American

MBA students who were idealistic, theistic,

intolerant, and not opportunistic were likely

to behave ethically. Hong Kong MBA

stu-dents who were idealistic, intolerant,

posi-tive, and not opportunistic tended to act

morally. Hong Kong students tended to be

less theistic, more tolerant, more detached,

more negatively oriented, more relativistic,

less achievement-oriented, and more

human-istic-oriented than were their American

counterparts.

Key words: academic dishonesty, Hong

Kong students, masters of business

admin-istration (MBA)

Copyright © 2007 Heldref Publications

A Comparative Study of Ethical Beliefs of

Master of Business Administration

Students in the United States With Those

In Hong Kong

M O H A M M E D R A W W A S ZIAD SWAIDAN HANS ISAKSON

UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN IOWA UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON-VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN IOWA CEDAR FALLS, IOWA VICTORIA, TEXAS CEDAR FALLS, IOWA

s a result of the corporate scan-dals involving Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Health-South, Martha Stewart, and the Wall Street analysts and the firms that supported them, educators have developed a growing concern about the character of today’s master of business administration (MBA) stu-dents’ ethical beliefs, primarily because the students are tomorrow’s business leaders (Merritt, 2004). Harris and Sut-ton (1995) previously found that MBA students were more tolerant of behav-iors related to “fraud” and “self-inter-est” than were Fortune 1,000 execu-tives. And recently, the Chronicle of Higher Education referred to Stearns and Borna’s (1998) study in which they reported that inmates were as ethical as MBA students, and sometimes more laudable, when faced with ethical busi-ness dilemmas. To have a somewhat comprehensive understanding of the ethical beliefs of MBA students, it would be beneficial to compare them with other MBA students in an industri-al region such as Hong Kong. Students in industrial countries or regions are expected to have similar standards, but differences in cultures may have some impact on their ethical behaviors.

Purpose

Our purpose in this study was to iden-tify the determinants of and differences between the ethical beliefs toward

acad-emic dishonesty of MBA students in two distinct cultures, the United States and Hong Kong. We hope that the results will assist faculty to develop better teaching curriculum that might improve the ethical beliefs of MBA students.

As students continue to face various sources of pressure from family, poten-tial employers, and others to achieve higher grades and as the economic situ-ation continues to hold fewer employ-ment prospects for college graduates, academic dishonesty is likely to contin-ue to be a global isscontin-ue of concern specifically in highly populated regions, such as Hong Kong. Academic dishon-esty, which “consists of any deliberate attempt to falsify, fabricate or otherwise tamper with data, information, records, or any other material that is relevant to the student’s participation in any course, laboratory, or other academic exercise or function” (San Joaquin Delta Col-lege, 2003, p.1), is a growing problem and concern for instructors and adminis-trators in higher education (Rawwas, Al-Khatib, & Vitell, 2004). Results of a U.S. governmental research study con-ducted by the Center for Academic Integrity (2000) heightened concern because the researchers found that the percentage of students who admitted to some cheating in 1963 (11%) had dra-matically increased to 75% by 1999.

The importance of cross-cultural stud-ies in which researchers investigate

busi-A

ness students’ ethical differences has also been on the rise, and several researchers have answered the call for this research (Husted, Dozier, McMahon, & Kattan, 1996; Kennedy & Lawton, 1996; Lyson-ski & Gaidis, 1991; Okleshen & Hoyt, 1996; Whipple & Swords, 1992). Lyson-ski and Gaidis found that the reactions of American, Danish, and New Zealand business undergraduate students to ethi-cal dilemmas were similar. However, other researchers (Husted et al.; Kennedy & Lawton, 1996; Okleshen & Hoyt, 1996; Whipple & Swords, 1992) report-ed ethical differences among students of various cultures in their studies. Whipple and Swords stated that American stu-dents were more critical than were British students regarding confidentiali-ty, research integriconfidentiali-ty, and marketing mix issues. Okleshen and Hoyt found that American students were less tolerant of fraud, coercion, and self-interest than were New Zealand students. Kennedy and Lawton revealed that the levels of alienation of Ukrainian students were high and their levels of religiousness were low relative to those of the U.S. stu-dents. Their results also associated the willingness to engage in unethical busi-ness practices with higher levels of alien-ation and lower levels of religiousness. Finally, Husted et al. (1996) contrasted the ethical beliefs of business MBA stu-dents from the United States, Mexico, and Spain and found that the U.S. stu-dents used postconventional level rea-soning more than did their Mexican or Spanish counterparts.

Although ethical beliefs of under-graduate and MBA students have been of interest to researchers, very little is known about the academic dishonesty of MBA students in the United States or in a foreign market, such as Hong Kong. Furthermore, academic dishonesty among today’s MBA students may have far-reaching effects on their future ethi-cal behavior and on international trade. Kung (1997) argued that ethics played an indispensable role in the process of globalization. In addition, researchers have considered academic dishonesty to be the equivalent of business wrongdo-ing (Burton & Near, 1995). The ratio-nale is that cheating on a paper is the college equivalent to misreporting time worked.

The core of both activities is basical-ly to gain an additional benefit for work not completed. An MBA student exchanges bogus papers for higher grades in much the same way a busi-nessperson exchanges fake reports for a promotion.

Our purpose in the present study is twofold: (a) to investigate several per-sonal beliefs and values and oppor-tunism variables that might contribute to the academic dishonesty of American and Hong Kong MBA students and (b) to compare American and Hong Kong MBA students with respect to their per-sonal beliefs and values, opportunism, and academic dishonesty variables. Finally, we will provide recommenda-tions for improving MBA curriculum and curbing academic dishonesty in the United States and Hong Kong.

Hypotheses

Hofstede (1984, 1997) found that societies differed along four cultural dimensions: (a) power distance (divi-sions between people who have wealth and power and those who do not), (b) uncertainty avoidance(relying on rules and procedures designed to limit risk and uncertainty), (c) individualism (valuing a high degree of freedom and independence), and (d) masculinity (valuing aggressiveness, competition, and ambition) or femininity (e.g., cher-ishing relationships, and nurturing). Hofstede found many collectivist cul-tures, such as that found in Hong Kong, to be (a) high on power distance (main-taining deep divisions), (b) high on uncertainty avoidance, (c) low on indi-vidualism (valuing loyalty to family, friends, and the organization more than freedom and independence), and (d) low on masculinity.

In contrast, Hofstede (1984, 1997) found many individualist cultures, such as that of the United States, to be (a) low on power distance (maintaining broad distribution of wealth and power), (b) low on uncertainty avoidance (exhibit-ing tolerance for abnormal ideas and behaviors), (c) high on individualism (valuing a high degree of freedom and independence), and (d) high on mas-culinity (rewarding aggressiveness and competition). In previous research, we and our colleagues found that those

dif-ferences influenced cultural difdif-ferences in general (Rawwas, 2001; Rawwas et al., 2004; Rawwas & Isakson, 2000).

Personal Beliefs and Values

Results of several studies (Rawwas et al., 2004; Rawwas & Isakson, 2000; Roig & Ballew, 1994) also indicated personal values were determinants of academic dishonesty. For example, Roig and Ballew believed that the deci-sion to cheat or not to cheat inherently lay within the individual’s personal value system. Furthermore, Rawwas et al., and Rawwas and Isakson found that students’ academic dishonesty practices could be partially explained by several personal beliefs and values variables, such as tolerance, achievement, ideal-ism, and relativism.

Tolerance and Intolerance of Misconduct

Tolerant people have liberal view-points and reject absolute truths. Howev-er, intolerant people have strict outlooks and believe in one true system of stan-dards for social conduct. Researchers (Hofstede, 1984; Singh, 1990) found intolerant people endorsed conformity and relationships more than indepen-dence and risk. Conversely, tolerant peo-ple did not fear the future, accepted risk easily (Hofstede, 1984; Kale, 1991; Kale & Barnes, 1992), severed existing rela-tionships (Kale & Barnes), and tolerated blunders because the cost of wrongdoing was relatively low in such cultures (Doney, Cannon, & Mullen, 1998).

Although both the U.S. and Hong Kong cultures were characterized by Hofstede (1984) as low in uncertainty avoidance, the Hong Kong culture had a lower score. Consequently, Hong Kong individuals might tolerate unethical practices more than U.S. individuals might. Evidence of this conjecture might be viewed with respect to the abuse of software rights in both cul-tures: U.S. firms lost only $2.8 million from software rights abuse, whereas its practice in Hong Kong caused multina-tional corporations to lose $88.6 million (Moores & Dhillon, 2000). Roig and Neaman (1994) found a positive rela-tionship between intolerance of wrong-doing and ethical decision making, and

a negative association between toler-ance of misconduct and ethical decision making.

In other studies, researchers found that tolerance was a positive determi-nant of academic dishonesty (Rawwas et al., 2004) and that people of collec-tivist cultures, such as the Polish, had a much more tolerant view of academic dishonesty than did the U.S. students (Ashworth & Bannister, 1997; Lupton, Chapman, & Weiss, 2000; Roberts & Toombs, 1993; Roig & Ballew, 1994). Therefore, we developed the following hypotheses:

H1a: Intolerance of academic dishonesty will be negatively associated with acade-mic dishonesty practices. However, toler-ance of academic dishonesty will have the opposite effect.

H1b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more tolerant of academic dishonesty than will the U.S. MBA students.

Achievement and Experience

Achievement-oriented people tend to value goal accomplishment, success, and the constructive use of time, where-as experience-oriented individuals are likely to be relaxed and to live for the moment (Foltz & Miller, 1994). Both the U.S. and Hong Kong cultures are characterized as masculine, in which individual decision-making, competi-tiveness, assercompeti-tiveness, and the accrual of wealth and belongings are encour-aged (Hofstede, 1984), and time is viewed as a commodity to be saved, scheduled, and managed (Schuster & Copeland, 1996).

In masculine cultures, people believe that many ethical conflicts can be solved without standard rules, and prin-ciples and regulations should only be formulated in case of absolute necessity (Hofstede, 1984; Rawwas, 2001). Their performance evaluation is based on individual achievement (Ueno & Sekaran, 1992), and individual bril-liance is admired and idolized (Kale, 1991). People within these cultures often pride themselves on efficiency and place a high price on success.

Franklyn-Stokes and Newstead (1995) found that individuals seeking success in such cultures might identify goals but use different means to achieve them. Those who worked hard to feel

gratified rather than to obtain a mere reward were less likely to cheat (Foltz & Miller, 1994). Results from several studies indicated that the most common justifications given for practicing acade-mic dishonesty included the time pres-sures, the desire for better grades, and the aspiration of achievement (Franklyn-Stokes & Newstead; Payne & Nantz, 1994; Roig & Ballew, 1994).

In a recent study, Harding (2004) sur-veyed 650 students from 12 universities and found that 75% of students admitted to taking part in academic dishonesty during their academic career. Their motivation to be engaged in cheating is driven by the perceived need to achieve higher grades and be socially accepted. Nowell and Laufer (1997) also found that achieving higher grades was the most important factor in leading stu-dents to engage in academic dishonesty. They found that students who achieved high grades in the class had no need to cheat and did not do so. Students who performed poorly in class were signifi-cantly more likely to cheat to alter their scores on the exams (Nowell & Laufer) and to possibly acquire a better job offer upon graduation (Bunn, Caudill, & Gropper, 1992). Although Hofstede (1984) classified both the U.S. and Hong Kong cultures as masculine, the United States scored higher on mas-culinity than did Hong Kong. Therefore, we developed the following hypotheses:

H2a: Achievement will be positively asso-ciated with academic dishonesty prac-tices; however, experience will have a negative effect.

H2b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more experience-oriented than will U.S. MBA students, and U.S. MBA students will be more achievement-oriented than will Hong Kong MBA students.

Idealism and Relativism

Forsyth (1980) has identified two major categories of moral philosophy: idealism and relativism. Although ideal-ism focuses on the specific actions or behaviors of the individual, relativism concentrates on the consequences of actions or behaviors. In other words, idealists believe that the inherent good-ness or badgood-ness of an action should allow one to determine the ethical course of action. However, relativists

judge an act as right only if it produces for all people a greater balance of posi-tive consequences than do other avail-able alternatives.

In Hong Kong, culture is based on Confucian values in which one ideally should find one’s own way to become a healthy individual with an ultimate commitment to concern for society (Liu, 1998). Empirical results indicated that people from Hong Kong possess strong Confucian values (Hofstede, 1997; Hofstede & Bond, 1988) and that Confucianism and individualism were negatively related (Yeh & Lawrence, 1995). Newstead (1996) cited idealism as an important factor explaining acade-mic dishonesty.

In studying a mainland Chinese sam-ple, Rawwas et al. (2004) found that idealism was a negative determinant of academic dishonesty. Idealists have a strong belief that morality will guide a person’s actions. Researchers have found that individuals who scored high on idealism also judged academic dis-honesty harshly (Forsyth, 1980, 1981, 1985), had a great ethic of caring (Forsyth, Nye, & Kelly, 1988), and scored low on Machiavellianism (Leary, Knight, & Barnes, 1986). In another study, Barnett, Bass, and Brown (1996) found that idealistic individuals were more likely to report a peer who was engaged in academic dishonesty than were relativistic individuals.

In Western culture, Aristotle’s (McGee, 1992) theory of ethics noted that the goal of the moral life is the self-perfection of the individual human being. To attain this goal, one should use practical reason to determine what ought to be done in a concrete situation. Practical reason is the use of judgment, rather than formalized rules, by which an individual determines the morality of a real situation. This moral judgment can vary from person to person, and cer-tain judgments can have larger roles in the lives of some persons than they do in others (McGee).

According to Hofstede (1984, 1997), a combination of low uncertainty avoid-ance and high individualism character-ized many European and American entrepreneurs. A culture of masculine risk-takers emphasizes earnings, com-petition, advancement, challenge, and

individual decision making. In a situa-tion with an ethical component, individ-uals in these cultures compare all possi-ble options and select the one that promises the best result (i.e., relativism; Hofstede, 1997). In a poll of 5,000 American students, the majority responded that the greatest authority in matters of truth was “their gut instinct, whatever feels right, whatever turns them on, whatever is relative, nego-tiable” (Kidder, 1992, p. 10).

Leary et al. (1986) also found that relativistic individuals scored high on Machiavellianism.

Machiavellianism was typically asso-ciated with poor concern for morality, and highly Machiavellian individuals were thought to reason differently about ethical issues than were non-Machiavel-lian individuals (Christie & Geis, 1970; Leary et al., 1986). Forsyth and Nye (1990) found that relativistic individuals also violated societal norms for person-al gain more than nonrelativistic indi-viduals did. This suggested that rela-tivistic individuals might be more likely to excuse academic dishonesty practices that were self-beneficial than might nonrelativistic individuals (Barnett, Bass, & Brown, 1996). In studying the ethical beliefs of American students, Rawwas and Isakson (2000) found rela-tivism was a positive determinant of academic dishonesty. Therefore, we hypothesized that

H3a: Idealism will be negatively associat-ed with academic dishonesty practices; however, relativism will have the opposite effect.

H3b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more idealistic than will U.S. MBA stu-dents, and Hong Kong MBA students will be less relativistic than will U.S. MBA students.

Positivism and Negativism

Positive people are optimistic and believe that things will get better, where-as negative individuals are pessimistic and doubtful about the future. Shainess (1993) found that individuals with a pos-itive self-concept had a tendency to develop an ethical sense and to recognize the role of conscience in life. However, Love and Simmons (1998) found that individuals with negative personal atti-tudes were associated with misconduct.

In Hong Kong, two major factors contributed to negativism: the Asian economic crisis of July, 1997 ( Alon & Kellerman, 1999; Roubini, 1999), and the emergence of severe acute respira-tory syndrome (SARS; U.S. Depart-ment of State, 2004). Hong Kong experienced deflation from November 1998 to July 2004, and property prices had fallen 66% in mid 2003 from their peak in 1997 (U.S. Department of State). Throughout that time, Hong Kong witnessed declining currency values, large layoffs, shrinking gross domestic products, and rising prices of staple items. Whereas Hong Kong ideals of hard work, respect for learn-ing, and collectivism brought them unparalleled growth, many analysts believe that high power distance and the unquestionable authority of offi-cials led to collusion, lack of trans-parency, corruption, and a boost to the “quanxi” system—a network of con-tacts that an individual calls upon when something needs to be done and through which he or she can exert influence on behalf of another (Wikipedia, 2006).

These prevailing factors in Hong Kong promoted pessimism and a nega-tive outlook (Alon & Kellerman, 1999). In general, individual attitudes undoubt-edly influence behavior, as researchers have conceptualized and tested in sever-al models of ethicsever-al behavior (Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Hunt & Vitell, 1993; Shaw & Clarke, 1999; Vitell, Singha-pakdi, & Thomas, 2001). Research results revealed that those who scored high on positivism were less likely to engage in unethical practices, such as academic dishonesty, than were those who scored low on positivism (Vitell & Muncy, 1992).

In studying the ethical beliefs of American students, Rawwas et al. (2004) found that positivism was a negative determinant and negativism was a posi-tive determinant of academic dishonesty. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H4a: Positivism will be negatively associ-ated with academic dishonesty practices. However, negativism will have the oppo-site effect.

H4b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more negative than will U.S. MBA stu-dents, and U.S. MBA students will be

more positive than will Hong Kong MBA students.

Behaviorism and Humanism

Behaviorist-oriented individuals tend to put considerable trust in science as a means of understanding and dealing with people. Behavioristssee people as neutral at birth, having the potential to learn to be either good or bad. Society, as seen by behaviorists, can teach appropriate or inappropriate behavior to its children. Behaviorists discount ideas related to innate and intangible topics, such as instincts, consciousness, or soul. Humanists, however, believe people possess a positive inborn drive to grow and improve. Instead of being born neu-tral, humans are born basically good, and society should build their inherent tendency to remain healthy and moral.

Mencius, an itinerant Chinese philosopher and sage, argued that human beings are born with an innate moral sense and that the goal of honor-able cultivation is to maintain one’s innate morality (Liu, 1998). According to Mencius, humanity, righteousness, and propriety are not drilled into people from outside; they originally have them within them. If one does something wicked, it is due to adverse environmen-tal influences (Liu). Humanists frown upon academic dishonesty because it is evil and not an inherent characteristic of humans (Rawwas et al., 2004).

Evidence from anthropology, psy-chology, and political science confirms that individualistic and masculine soci-eties believe in behaviorism (Hofstede, 1984), and the large degree of freedom to learn to be either good or bad does lit-tle to restrict variance in human behav-ior and discounts the price for mischief (Doney, Cannon, & Mullen, 1998). Because individualist societies accept great range in peoples’ behaviors (Kale & McIntyre, 1991), the costs for engag-ing in wrongdoengag-ing, such as academic dishonesty, do not appear to be substan-tial (Hofstede, 1984).

The individualism or collectivism dimensions influence the likelihood that societies will act opportunistically (Doney et al., 1998). The possibility that collectivists will engage in misconduct is low because collectivists hold group values and beliefs and seek affiliated

interests (Hofstede 1984; Singh 1990). Self-serving behaviors, such as academ-ic dishonesty practacadem-ices, are unlikely because of the high cost of social sanc-tions; people who violate in-group norms may be ostracized by the group (Earley, 1989; Ueno & Sekaran, 1992). Therefore, we posed the following hypotheses:

H5a: Humanism will be negatively associ-ated with academic dishonesty practices; however, behaviorism will have the oppo-site effect.

H5b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more humanistic-oriented than will U.S. MBA students, and U.S. MBA students will be more behaviorist-oriented than will Hong Kong MBA students.

Detachment and Involvement

According to Foltz and Miller (1994), detached people tend to keep a distance from others, avoiding emotional risk. However, attached or involved people tend to feel it is important to make com-mitments and be associated with others. Selmer (1998) further reported that in collective societies, such as in Hong Kong, people have a strong sense of group identification. From a very young age, Hong Kong children are taught the importance of loyalty and obedience. The family unit teaches the children to restrain their individuality and maintain a harmonious atmosphere (i.e., be attached to the group).

The social order of the family also serves as a prototype for conduct in all other Hong Kong organizations. Indi-viduals subordinate themselves to the group, the community, and the state. Subordinates are expected to be loyal without question. Any misconduct by an individual is the responsibility of the group (Selmer, 1998). Because people in collectivist societies maintain confor-mity and seek collective interests, the likelihood that they will engage in opportunistic behavior is low (Hofstede, 1984; Singh, 1990).

By contrast, people in individualistic societies, such as the United States, often define themselves as standing out from the group (i.e., being detached), empha-sizing identity, reward, and status (Stei-dlmeier, 1999). The theory of motivation asserts that individuals should seek to maximize their own pleasure (Grassian,

1981). Other pleasures are important only if they are seen as means to the sat-isfaction of one’s own enjoyment (Grass-ian). Roig and Neaman (1994) found indications that the attitudes underlying academic dishonesty also seem to be associated with detachment.

Student detachment as regarded by Pruden, Shuptrine, and Longman (1974) includes a normlessness factor that represents an attitude in which social norms are no longer considered to be effective as rules for behavior. Thus, detached students are not likely to employ norms to guide their behavior, and therefore, one might expect that these students would find academic dis-honesty practices to be acceptable (i.e., student detachment would be positively related to academic dishonesty). This was supported in Rawwas et al.’s (2004) study in which they found detachment to be a positive determinant of receiving and abetting academic dishonesty.

In addition, Vitell and Muncy (1992) found that detached individuals had a negative attitude toward institutions, such as universities, and were not sen-sitive to ethical issues. In a more recent study, Vitell, Singhapadki, and Thomas (2001) found individual detachment to be associated negatively with one’s ethical beliefs. The theoretical reason-ing is that if social norms are no longer effective rules for behavior, then one might expect a student’s ethical beliefs to be adversely affected as well. There-fore, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H6a: Involvement will be negatively asso-ciated with academic dishonesty prac-tices; however, detachment will have the opposite effect.

H6b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more involved than will U.S. MBA stu-dents, and U.S. MBA students will be more detached than will Hong Kong MBA students.

Theism and Nontheism

Theistic-oriented people believe in the existence of God, or a supreme being, whereas nontheistic-oriented people share a secular outlook on behavior. Religion is a powerful ethi-cal voice in contemporary life. From a religious point of view, the deity’s laws are absolutes that must shape the

whole of one’s life, including work. Faith, rather than reason, intuition, or secular knowledge, provides the foun-dation for a moral life built on religion. Giorgi and Marsh (1990) indicated that religion and the level of religious fer-vor of individuals had a positive effect on their ethics. McCabe and Trevino (1993) found that unethical behavior was negatively related to the severity of penalties.

Singhapakdi, Marta, Rallapalli, and Rao (2000) reported that religiousness partly explained the insights and inten-tions of marketers toward an ethical dilemma. Likewise, Kennedy and Law-ton (1998) found a negative relationship between religiousness and willingness to behave unethically. In addition, researchers found that students at a reli-giously affiliated university were far less willing to engage in unethical behavior than were students at an unaf-filiated university (Roberts & Rabi-nowitz, 1992). In spite of the flourish of Buddhism, Taoism, and other religions in Hong Kong during the roughly 150 years of British colonialism, the influx of immigrants from mainland China has produced a good number of nontheistic people. Although an overwhelming majority of Americans (85%) catego-rized themselves as religious (“Psalm pilots,” 2001), only 43% of Hong Kong individuals classified themselves as reli-gious (U.S. Department of State, 2004). Therefore, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H7a: Theism will be negatively associated with academic dishonesty practices. However, nontheism will be positively associated with academic dishonesty.

H7b: U.S. MBA students will be more theistic than will Hong Kong MBA stu-dents.

Opportunism

Williamson (1975) defined oppor-tunism as “self-interest seeking with guile” (p. 6). For example, an official who conceals information or provides favoritism for the sake of self-enhance-ment is taking advantage of oppor-tunism. Temptation can even sway those with strong personal ethics. Malinowski and Smith (1985) reported lower inci-dents of cheating among those who pos-sessed higher moral reasoning.

er, this group was inclined to behave unethically when the temptation was great. Newstead et al. (1996) found indications that people who cheat neu-tralize their behavior by blaming it on the situation rather than on themselves.

Hofstede’s (1984) power distance dimension addressed ideological orien-tations and behavioral adaporien-tations to authority. Opportunism may be less likely in low power distance cultures (such as the United States), which tend toward a natural sharing of power and more participative decision making. In such cultures, people are more willing to consult with others and moderate the use of power (Kale & McIntyre, 1991). However, the use of power and coercion are frequent occurrences in high power cultures (such as Hong Kong; Kale & McIntyre, 1991). John (1984) showed empirically that perceptions of increased centralization, controls, and coercion led to more opportunism, and oppressed individuals sought more opportunistic behavior to alleviate oppression. On the basis of the previous analysis, we developed two hypotheses:

H8a: Opportunism will be positively associ-ated with academic dishonesty practices.

H8b: Hong Kong MBA students will be more opportunistic than will U.S. MBA students.

METHOD

Research Setting

We selected business college students who were taking MBA marketing classes as subjects for this study. This choice was motivated by several reasons. Foremost, cheating in college is a highly appropri-ate form of unethical behavior to study because students’ involvement in cheat-ing, such as communicating answers, peeping, using crib notes or formulas during exams, or submitting a forged paper are very prevalent. Second, previ-ous researchers used academic dishon-esty as a type of business organizational wrongdoing (e.g., Burton & Near, 1995). Finally, future business leaders will come from the ranks of today’s MBA students.

Data

Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to two groups of U.S.

and Hong Kong MBA students to iden-tify the determinants of and differ-ences between their attitudes toward various forms of academic dishonesty in the fall 2003 semester. The first group consisted of 288 students in 9 MBA marketing classes of a public university in the United States. The second group consisted of 140 students in five MBA marketing classes in a Hong Kong university. All of the MBA students completed English versions of the questionnaires during the first por-tion of a class period (the language of instruction in Hong Kong was Eng-lish). All responses were anonymous. The survey (see Appendix) included questions related to various forms of

academic dishonesty, personal values and beliefs, opportunism, and demo-graphics.

Student Attitudes Toward Various Forms of Academic Dishonesty (Factors 1 & 2)

Student attitudes toward cheating were measured using factor analysis of 13 sit-uations that resulted in two factors (“receiving and abetting academic dis-honesty” and “getting involved in ques-tionable academic dishonesty”) involv-ing various forms of cheatinvolv-ing (see Table 1). This scale was adopted from Rawwas and Isakson (2000), and factor labels were adopted from Rawwas et al. (2004).

TABLE 1. Factor Analysis Results and Reliabilities of American and Hong Kong Master of Business Administration (MBA) Samples

U.S. Sample H.K. Sample Factor Rel. Factor Rel.

Variable loading α loading α

Factor 1: Receiving and abetting

academic dishonesty .77 .70

1. Communicating answers (e.g., whisper, give sign language) to a friend during

a test. .65 .71

2. “Hacking” your way into the university’s

computer system to change your grade. .64 .64 3. Hiring someone or having a friend take

a test for you in a very large class. .62 .51 4. Peeping at your neighbor's exam during

the test. .61 .52

5. Using unauthorized “crib notes” during

an exam. .59 .63

6. Turning in a term paper that you

purchased or borrowed from someone else. .53 .77

Factor 2: Getting involved in questionable

academic dishonesty activities .72 .70

1. Receiving extra credit because the

instructor likes you. .70 .61

2. Receiving favoritism as a result of being a student athlete or member of a

campus organization. .60 .78

3. Receiving a higher grade through the influence of a family or personal

connection. .59 .70

4. Being allowed to perform extra work, which is not assigned to all class

members, to improve your grade. .59 .55 5. Brown-nosing your professors. .55 .71 6. Contributing little to group work and

projects, yet still receiving the same

credit and grade as the other members. .52 .65 7. Having access to old exams in a

particular course to which other students

do not have access. .50 .62

We asked the participants to indicate their approval of each activity on a Lik-ert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly believe that it is wrong) to 5 (strongly believe that it is not wrong). Factor analysis with varimax rotation identified two significant dimensions (see Table 1). According to Peterson (1994) and Nun-nally (1978), the reliabilities of the dimensions were generally acceptable (α ≥ .65) for both groups (see αin Table 1). Both dimensions, labeled as “receiving and abetting academic dishonesty” and “getting involved in questionable acade-mic dishonesty activities,” were treated as dependent variables.

The most significant characteristics of the first dimension, “receiving and abetting academic dishonesty” (see items in Table 1), were almost univer-sally perceived as unethical and initiat-ed by the student (e.g., using unautho-rized “crib notes” during an exam). The second dimension, “getting involved in questionable academic dis-honesty activities” (see items in Table 1), occurred when students were engaged in dubious situations, such as “receiving extra credit because the instructor likes you.”

Personal Beliefs and Values

Eight constructs (a) tolerance versus intolerance, (b) achievement versus experience, (c) negativism versus posi-tivism, (d) behaviorism versus human-ism, (e) detachment versus involve-ment, and (f) nontheism versus theism (included in Tables 2 and 4), (g) ideal-ism, and (h) relativism (included in Table 4; see Forsyth [1980] for indi-vidual items) were used to measure the beliefs and values of students about life and relations with other people. The first six measures were adopted from the Beliefs and Values Question-naire (BVQ) used by Foltz and Miller (1994). Each scale was measured by using a formula. For instance, Scale I measured a tolerance versus intoler-ance orientation by adding 10 to total scores of two tolerance items minus total scores of two intolerance items. The last two constructs were the pre-dominant ethical ideology (idealism and relativism) of the Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) used by Forsyth

(1980). Cronbach alphas for the EPQ scales were > .80 for both groups.

Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with each item for all aforementioned dimensions using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). All of the eight dimensions were treated as independent variables. To check the reliability of our results, we have compared the means of per-sonal beliefs and values of Foltz and Miller’s (1994) national study with those of our study. Table 2 shows the means of the beliefs and values of both studied samples and the national ple of Foltz and Miller. Our U.S. sam-ple seemed to benchmark reasonably

well against the U.S. national sample of Foltz and Miller.

Opportunism

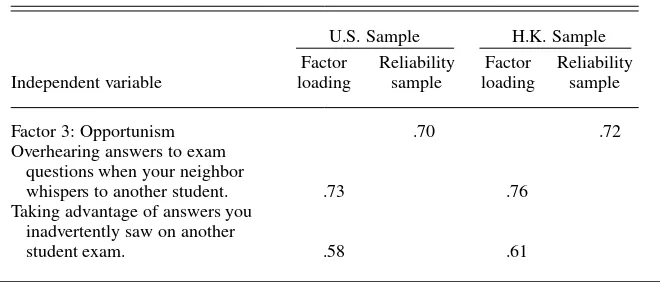

The opportunism construct included situations in which students were engaged in questionable practices that provided rewards, such as “taking advantage of answers you inadvertently saw on another student’s exam” (see Table 3). This scale was also adopted from Rawwas and Isakson (2000). Sub-jects were asked to indicate their approval of each activity on a standard Likert scale (1 = strongly believe that it is wrong, 5 = strongly believe that it is not wrong). This dimension was also treated as an independent variable.

TABLE 2. Descriptive Statistics of Beliefs and Values of American and Hong Kong Master in Business Administration (MBA) Students

Foltz &

Miller’s U.S. sample H.K. sample

M M SD M SD

Theistic or nontheistica 10 13.13 3.50 10.92 3.71 Achievement or experienceb 11 10.28 1.72 9.76 1.76 Detachment or involvementc 6 7.38 2.14 9.21 1.95 Tolerance or intoleranced 10 9.51 1.91 10.69 1.83 Behaviorism or humanisme 7 8.16 2.19 7.28 2.02 Positive or negativef 10 11.45 2.36 10.49 2.27

Note. Each scale was measured by using a formula. For example, Scale I measured a tolerance ver-sus intolerance orientation by adding 10 to total scores of two tolerance items minus total scores of two intolerance items. Data in Column 2 are from Appendix C by G. J. Foltz and N. Miller, 1994, in “Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases,” (pp. 326–328). aHigher scores

indicate a conventional religious outlook and low scores reflect a secular outlook. bHigh scores

characterize achievement-oriented individuals whereas low scores describe experience-oriented individuals. cHigh scores illustrate detached people whereas low scores characterize involved

peo-ple. dHigh scorers are tolerant while low scorers are intolerant. eThe high scorer tends to be

behav-iorism-oriented whereas the low scorer tends to be humanism-oriented. fThe high scorer is

posi-tive whereas the low scorer is negaposi-tive.

TABLE 3. Factor Analysis Results and Reliabilities of Opportunism for the American and Hong Kong MBA Samples

U.S. Sample H.K. Sample Factor Reliability Factor Reliability Independent variable loading sample loading sample

Factor 3: Opportunism .70 .72

Overhearing answers to exam questions when your neighbor

whispers to another student. .73 .76 Taking advantage of answers you

inadvertently saw on another

student exam. .58 .61

Statistical Analysis

We examined the personal beliefs and values of the students as well as oppor-tunism as determinants of the two dimensions of Rawwas and Isakson (2000). Academic Dishonesty Scale (“receiving and abetting academic dis-honesty” and “getting involved in ques-tionable academic dishonesty activi-ties”) using stepwise multiple regression analyses. We assumed the relationship between the two dimen-sions and the independent variables, personal beliefs and values and oppor-tunism, to be linear as follows:

Fi= αi+ βI Xij+ εij

where, Fi represented a vector of the two attitudes toward cheating,Xij repre-sented a vector of the nine independent variables for each of the two attitudes, and εijrepresents the error term that was assumed to have a multivariate normal distribution. The parameters αi and βi were estimated from the data using the stepwise ordinary least squares tech-niques. To determine whether ethical beliefs of Hong Kong and American MBA students differed with respect to the variables of interest, we used multi-variate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and multiple discriminant analysis (MDA).

RESULTS

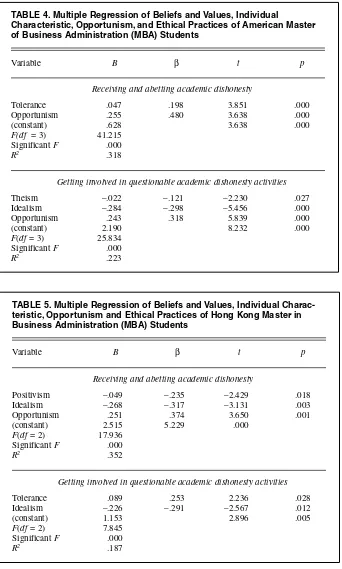

Table 4 shows the results of the regression analyses for the American sample, and Table 5 shows the results for the Hong Kong sample. The F- sta-tistic of each regression and the coeffi-cient of each independent variable were statistically significant. Independent variables that did not appear in the regressions for both groups (Tables 4 and 5) were eliminated by the stepwise regression technique because of their poor contribution to the explanatory power of the regressions.

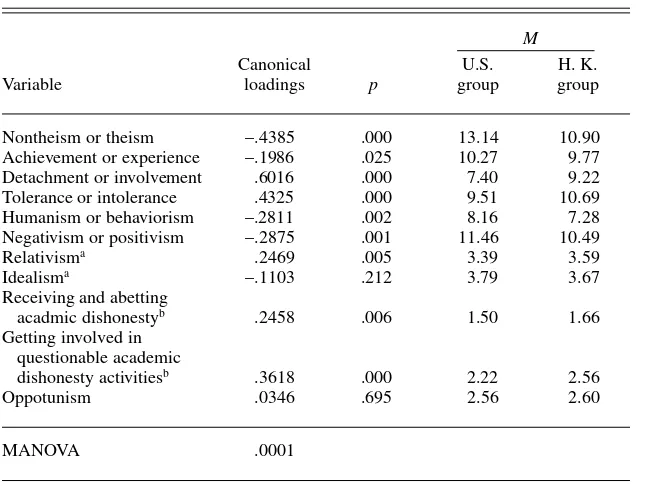

Table 6 shows a summary of the MANOVA and MDA results for the American and Hong Kong groups. The multivariate result was significant with high statistical power allowing for the subsequent univariate interpretation of the results. Of the 11 variables, 9 crite-rion variables (7 values and beliefs and 2 ethical behaviors variables) differed

significantly between the groups. We will discuss specific findings related to the hypotheses later.

Hypotheses1a–8a

Multiple regression analyses provid-ed partial support for H1a–8a. We con-ducted these for each separate subsam-ple (U.S. and Hong Kong; see Tables 4 and 5). They revealed that for the

Amer-ican group, tolerance (H1a) was a posi-tive determinant of receiving and abet-ting academic dishonesty, and for the Hong Kong group, it was a positive determinant of getting involved in ques-tionable academic dishonesty activities. For the American group, idealism (H3a) was a negative determinant of only get-ting involved in questionable academic dishonesty activities, but for Hong

TABLE 4. Multiple Regression of Beliefs and Values, Individual

Characteristic, Opportunism, and Ethical Practices of American Master of Business Administration (MBA) Students

Variable B β t p

Receiving and abetting academic dishonesty

Tolerance .047 .198 3.851 .000

Opportunism .255 .480 3.638 .000

(constant) .628 3.638 .000

F(df = 3) 41.215 Significant F .000

R2 .318

Getting involved in questionable academic dishonesty activities

Theism –.022 –.121 –2.230 .027

Idealism –.284 –.298 –5.456 .000

Opportunism .243 .318 5.839 .000

(constant) 2.190 8.232 .000

F(df = 3) 25.834 Significant F .000

R2 .223

TABLE 5. Multiple Regression of Beliefs and Values, Individual Charac-teristic, Opportunism and Ethical Practices of Hong Kong Master in Business Administration (MBA) Students

Variable B β t p

Receiving and abetting academic dishonesty

Positivism –.049 –.235 –2.429 .018

Idealism –.268 –.317 –3.131 .003

Opportunism .251 .374 3.650 .001

(constant) 2.515 5.229 .000

F(df= 2) 17.936 SignificantF .000

R2 .352

Getting involved in questionable academic dishonesty activities

Tolerance .089 .253 2.236 .028

Idealism –.226 –.291 –2.567 .012

(constant) 1.153 2.896 .005

F(df= 2) 7.845 Significant F .000

R2 .187

Kong students, it was a negative deter-minant of both of the dimensions of aca-demic dishonesty, receiving and abet-ting academic dishonesty and getabet-ting involved in questionable academic dis-honesty activities. Other results sug-gested that for the Hong Kong sample, positivism (H4a) was a negative determi-nant of receiving and abetting academic dishonesty, whereas for the American sample it was not. In addition, for the U.S. group, theism (H7a) was negatively associated with getting involved in questionable academic dishonesty activ-ities, but for the Hong Kong group it was not. Overall, opportunism (H8a) was the most significant determinant of aca-demic dishonesty practices.

The influences of achievement versus experience (H2a), relativism (H3a), humanism versus behaviorism (H5a), and detachment versus attachment (H6a) were not supported for either the Amer-ican group or the Hong Kong group.

Hypotheses1b–8b

In support of Hypotheses1b–8b, MANOVA and MDA analyses found that Hong Kong MBA students were more tolerant (H1b), less

achievement-oriented (H2b ), more negatively oriented (H4b), more humanistic-oriented (H5b), and less theistic (H7b) than were Ameri-can MBA students. Furthermore, and contrary to predictions, we found Hong Kong MBA students to be more rela-tivistic (H3b) and more detached (H6b) than were the U.S. students. There were no significant differences between the two samples regarding idealism (H3b) and opportunism (H8b).

Although there were no specific hypotheses regarding the two dimensions of academic dishonesty, we compared the two samples on both dimensions (see Table 4). Results showed that there were significant results related to the differ-ences between the two samples, and Hong Kong MBA students were more likely than were American students to believe that “receiving and abetting acad-emic dishonesty” and “getting involved in questionable academic dishonesty activities” were not wrong.

DISCUSSION

Overall, although many of the inde-pendent variables did not survive in the stepwise regressions, the results provid-ed some support to the relationships. In

the American sample, opportunism appeared twice, and theism, tolerance of academic dishonesty, and idealism each appeared once, all with the expected signs. Tolerance and opportunism explained 31.8% of receiving and abet-ting academic dishonesty. Theism, ideal-ism, and opportunism explained 22.3% of getting involved in questionable acad-emic dishonesty activities. In the Hong Kong sample, idealism appeared twice, and opportunism, tolerance of academic dishonesty, positivism, and idealism each appeared once, all with the expect-ed signs. Positivism, idealism, and opportunism explained 35.2% of receiv-ing and abettreceiv-ing academic dishonesty. Tolerance of academic dishonesty and idealism explained 18.7% of getting involved in questionable academic dis-honesty activities.

Apparently, opportunism and toler-ance of academic dishonesty had the greatest impact upon the attitudes of the U.S. MBA students toward the two forms of academic dishonesty. MBA students who scored high on tolerance of academic dishonesty and oppor-tunism were most likely to be engaged in academic dishonesty. Theistic and idealistic students tended to find some forms of academic dishonesty less acceptable.

The results of this analysis revealed that the characteristics of the American MBA students most likely to find any form of academic dishonesty acceptable included high scores on tolerance of academic dishonesty and opportunism and low scores on idealism and theism. Conversely, the characteristics of the American MBA students most likely to find any form of academic dishonesty unacceptable included low scores on tolerance of academic dishonesty and opportunism and high scores on ideal-ism and theideal-ism.

For Hong Kong MBA students, opportunism, idealism, and tolerance of academic dishonesty had considerable influence upon their attitudes toward the two forms of academic dishonesty. In addition, among Hong Kong MBA stu-dents, positivism tended to be negative-ly associated with academic dishonesty. The characteristics of Hong Kong MBA students most likely to find any form of academic dishonesty acceptable

includ-TABLE 6. Determinants of Ethical Attitudes of American and Hong Kong Masters in Business Administration (MBA) Students

(Multiple Discriminant Analysis)

M

Canonical U.S. H. K.

Variable loadings p group group

Nontheism or theism –.4385 .000 13.14 10.90 Achievement or experience –.1986 .025 10.27 9.77 Detachment or involvement .6016 .000 7.40 9.22 Tolerance or intolerance .4325 .000 9.51 10.69 Humanism or behaviorism –.2811 .002 8.16 7.28 Negativism or positivism –.2875 .001 11.46 10.49

Relativisma .2469 .005 3.39 3.59

Idealisma –.1103 .212 3.79 3.67

Receiving and abetting

acadmic dishonestyb .2458 .006 1.50 1.66 Getting involved in

questionable academic

dishonesty activitiesb .3618 .000 2.22 2.56

Oppotunism .0346 .695 2.56 2.60

MANOVA .0001

Note.aMeasured on a 5-point scale (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). bMeasured on

a 5–point scale (1 = strongly believe that it is wrong, 5 = strongly believe that it is not wrong).

ed high scores on opportunism and tol-erance of academic dishonesty, and low scores on positivism and idealism. Con-versely, the characteristics of Hong Kong MBA students most likely to find any form of academic dishonesty unac-ceptable included high scores on ideal-ism and positivideal-ism and low scores on opportunism and tolerance of academic dishonesty.

When we compared both groups with each other in relation to the two acade-mic dishonesty factors and personal beliefs and values, we found that both factors significantly differed between the two groups: Both were rated by Hong Kong MBA students as more acceptable practices than they were by the U.S. MBA students. Therefore, we may deduce that Hong Kong MBA stu-dents showed less ethical sensitivity than did the U.S. MBA students. In addition, Hong Kong MBA students were more tolerant, more detached, less theistic, more negative, and more rela-tivistic than were the U.S. MBA stu-dents. These results showed that Hong Kong MBA students were less sensitive to academic dishonesty than were the U.S. MBA students.

Finally, the relationship between unethical behaviors and opportunism was supported by the regression analy-sis in both groups. When MBA students were presented with the opportunity to cheat, they tended to take advantage of it. This result suggested that the reduc-tion of opportunities to behave unethi-cally would tend to reduce MBA stu-dents’ cheating. Moreover, the coefficients of opportunism for both groups appeared, in almost all cases, higher than the coefficients of any other variable. This made opportunism the strongest determinant of MBA students’ attitudes toward academic dishonesty.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that certain actions can improve the moral behavior of future business leaders. Efforts in schools of business that would improve the ethical behavior of MBA students include (a) reducing opportunities to cheat, (b) improving positive attitudes, (c) encouraging intolerance of academ-ic dishonesty, and (d) giving concrete examples of the high cost of unethical

behavior in business. We also found that some actions would have little if any effect on the ethical behavior of MBA students, such as (a) encouraging involvement, (b) teaching formal reli-gious ethics classes, and (c) dissuading competition.

Academic dishonesty is a serious problem because the professor’s goal is to produce knowledge, but the knowl-edge acquired by students who cheat will be much less than that acquired by students who do not cheat. Students who are successfully engaged in acade-mic dishonesty can reap the benefits of passing the class or obtaining high grades at the expense of producing MBAs with less knowledge.

Although previous research results (Newstead et al., 1996) indicated that the elimination of opportunism was the major solution to control academic dis-honesty, in this study we found that this solution is not sufficient. According to the results of this study, professors should be involved in a three-stage process to eradicate academic dishon-esty. They should not only eliminate opportunities to cheat but also raise the costs of academic dishonesty practices and keep students informed about the consequences of cheating.

In the first stage, professors can reduce or eliminate opportunism or temptation to cheat by dispersing stu-dents in the class during examinations and making several versions of an exam. In class, during an exam, they can prohibit the presence of items such as computers, cell phones, and advanced calculators that provide easy opportuni-ties to cheat. Professors can also main-tain a physical and vigilant presence during examinations. Malinowski and Smith (1985) found that even students high in moral standards are likely to cheat when the temptation is strong.

In the second stage, professors can increase the cost or price of cheating rather than attempting to improve the personal and religious beliefs and val-ues of students because we found these factors to have little or no ability to deter academic dishonesty. Professors can increase the cost of cheating by either increasing the probability of cap-ture and conviction or by increasing the penalty or consequences of cheating.

Careful monitoring of students during an exam and the use of computer-based methods of detecting plagiarism are just two ways in which faculty can increase the probability of capture. Increasing the probability of conviction, once cap-tured, depends upon the willingness of the institution to prosecute cheaters. Although the process of prosecuting cheaters is largely outside the control of an individual professor, the faculty can and, often does, have considerable col-lective influence on this process as well as the consequences of cheating.

In the third stage, professors can keep students well informed regarding the consequences of cheating. An institu-tional well-articulated honor code with specific consequences can go a long way toward achieving this last stage. When students have a clear understand-ing about what constitutes cheatunderstand-ing, as well as the consequences of cheating, students will respond accordingly. Without an institutional honor code with specific consequences, faculty can establish their own. Unfortunately, this sort of individual-professor approach to honor codes and consequences can make this entire stage very confusing for students and faculty alike. In addi-tion, centralized tracking of cheaters aids in capturing and punishing repeat offenders, who could otherwise claim ignorance and first-time offender status every time they get caught by a different professor.

The findings of this study also sug-gest that teaching MBA students’ for-mal ethical behavior based on religious beliefs or other beliefs and values will probably not influence their behavior. Studying ethics alone does not influ-ence the ethical behavior of MBA stu-dents. Instead, the third stage suggests that some practical instruction of ethical business practices might be beneficial. MBA students who study the conse-quences of ethical mistakes might behave more ethically in the future. For example, professors of the Robert Smith School of Business of the University of Maryland have taken their 2nd-year MBA students to visit white-collar con-victed felons in federal prisons for the past 8 years (Merritt, 2004). Unless business MBA students are convinced that there is a high cost associated with

unethical business behavior, they will not be likely to become less tolerant of unethical practices.

U.S. professors teaching in Hong Kong’s business schools may incorpo-rate into their course an ethics compo-nent or lecture that focuses on practical ethics and consequences of misbehavior similar to the accreditation course requirement in the United States (Asso-ciation to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International [AACSB], 2004). Consistent with the recommendation by Marta, Singhapakdi, Rallapalli, and Joseph (2000), U.S. business educators may instruct Hong Kong MBA students in how to analyze different ethical cases and mistakes from diverse cultures. A visit to white-collar felons in prisons might also help shape the ethical behav-iors of Hong Kong MBA students. We hope that this will improve positive atti-tudes and encourage intolerance toward academic dishonesty.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dr. Mohammed Rawwas, Univer-sity of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA 50614.

E–mail: rawwas@uni.edu

REFERENCES

Alon, I., & Kellerman, E. A. (1999). Internal antecedents to the 1997 Asian economic crisis.

Multinational Business Review, 7(2), 1–12. Ashworth, P., & Bannister, P. (1997). Guilty in

whose eyes? University students’ perceptions of cheating and plagiarism in academic work and assessment. Studies in Higher Education,

22(2),187–203.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International (AACSB). (2004).

Accreditation council policies, procedures and standards. St. Louis, MO: American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., & Brown, G. (1996). Reli-giosity, ethical ideology, and intentions to report a peer’s wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics, 15,1161–1175.

Bunn, D. N., Caudill, S. B., & Gropper, D. M. (1992). Crime in the classroom: An economic analysis of undergraduate student cheating behavior. Research in Economic Education, 23,

197–208.

Burton, B. K., & Near, J. P. (1995) Estimating the incidence of wrong doing and whistle-blowing: Results of a study using randomized response technique. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(1), 17–30.

Center for Academic Integrity. (2000). CAI research. Retrieved December 29, 2006, from www.academicintegrity.org/cai_research.asp Christie, R., & Geis, F. I. (1970). Studies in

Machiavellianism.New York: Academic Press. Doney, P. M., Cannon, J. P., & Mullen, M. R. (1998). Understanding the influence of a national culture on the development of trust.

Academy of Management Review, 23,601–620. Earley, P. C. (1989). Social loafing and collec-tivism: A comparison of the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34,565–581.

Ferrell, O. C., & Gresham, L. G. (1985). A con-tingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Mar-keting, 49,87–96.

Foltz, G. J., & Miller, N. (1994). Beliefs and Val-ues QVal-uestionnaire (BVQ). In O. C. Ferrell & J. Fraedrich (Eds.),Business ethics: Ethical deci-sion making and cases(pp. 326–328). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ide-ologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psy-chology, 46,1365–1375.

Forsyth, D. R. (1981). Moral judgment: The influ-ence of ethical ideology. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 7,218–223.

Forsyth, D. R. (1985). Individual differences in information integration during moral judgment.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49,264–272.

Forsyth, D. R., & Nye, J. L. (1990). Personal moral philosophies and moral choice. Journal of Research in Personality, 24,398–758. Forsyth, D. R., Nye, J. L., & Kelley, K. (1988).

Idealism, relativism, and the ethic of caring.

The Journal of Psychology, 112,243–248. Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Newstead, S. E. (1995).

Undergraduate cheating: Who does what and why? Studies in Higher Education, 20,

159–172.

Giorgi, L., & Marsh, C. (1990). The protestant work ethic is a cultural phenomenon. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20,499–517. Grassian, V. (1981). Moral reasoning: Ethical

the-ory and some contemporary moral problems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Harding, T. (2004). An honest look at cheating.

Industrial Engineer, 36(9), 16–18.

Harris, J. R., & Sutton, C. D. (1995). Unraveling the ethical decision-making process: Clues from an empirical study comparing Fortune 1000 executives and MBA students. Journal of Business Ethics, 14,805–818.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related val-ues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Cambridge, England: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1988). The Confu-cius connection: From cultural roots to eco-nomic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 5–21.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1993). The general theo-ry of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revi-sion. In N. C. Smith & J. A. Quelch (Eds.),

Ethics in marketing(pp. 775–784). Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Husted, B. W., Dozier, J. B., McMahon, J. T., Kat-tan, M. W. (1996). The impact of cross-nation-al carriers of business ethics on attitudes about questionable practices and form of moral rea-soning. Journal of International Business Stud-ies,27,391–412.

John, G. (1984). An empirical investigation of some antecedents of opportunism in a market-ing channel. Journal of Marketing Research, 21,278–289.

Kale, S. H. (1991). Culture-specific marketing communications: An analytical approach, Inter-national Marketing Review, 8(2), 18–30. Kale, S. H., & Barnes, J. W. (1992).

Understand-ing the domain of cross-national buyer-seller

interactions. Journal of International Business Studies, 23,101–132.

Kale, S. H., & McIntyre, R. P. (1991). Distribution channel relationships in diverse cultures. Inter-national Marketing Review, 8(3), 31–45. Kennedy, E., & Lawton, L. (1996). The effects of

social and moral integration on ethical stan-dards: A comparison of American and Ukrain-ian business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 15,901–911.

Kennedy, E. J., & Lawton, L. (1998). Religious-ness and busiReligious-ness ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 17,163–175.

Kidder, R. M. (1992), Ethics, a matter of survival.

Futurist, 26(2), 10.

Kung, H. (1997), A global ethic in an age of glob-alization. Business Ethics Quarterly, 7(3), 17–32. Leary, M. R., Knight, P. D., & Barnes, B. D. (1986). Ethical ideologies of the Machiavellian.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12,

75–80.

Liu, S. H. (1998). Understanding Confucian phi-losophy: Classical and sung-ming. London: Greenwood Press.

Love, P. G., & Simmons, J. (1998). Factors influ-encing cheating and plagiarism among graduate students in a college of education. College Stu-dent Journal, 32,539–550.

Lupton, R. A., Chapman, K. J., & Weiss, J. E. (2000). A cross-national exploration of business students’ attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies toward academic dishonesty. Journal of Educa-tion for Business, 75,231–235.

Lysonski, G., & Gaidis, A. (1991). A cross-cultur-al comparison of the ethics of business students.

Journal of Business Ethics, 10,141–150. Malinowski, C. I., & Smith, C. P. (1985). Moral

reasoning and moral conduct: An investigation prompted by Kohlberg’s theory. Journal of Per-sonality and Social Psychology, 49,

1016–1027.

Marta, J. K., Singhapakdi, A., Rallapalli, K. C., & Joseph, M. (2000). Moral philosophies, ethical perceptions, and marketing education: A multi-country analysis. Marketing Education Review, 10(2), 37–47.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1993). Acade-mic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contex-tual influences. Journal of Higher Education, 64,523–538.

McGee, R. W. (1992). Business ethics and com-mon sense. Westport, CT: Quorum Books. Merritt, J. (2004, October 18). Welcome to ethics

101. Business Week, 90.

Moores, T., & Dhillon, G. (2000). Software pira-cy: A view from Hong Kong. Association for Computing Machinery, Communications of the ACM,43,88–93.

Newstead, S. E., Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Arm-stead, P. (1996). Individual differences in stu-dent cheating. Journal of Educational Psychol-ogy, 87,229–241.

Nowell, C., & Laufer, D. (1997). Undergraduate student cheating in the fields of business and economics. Journal of Economic Education, 28(1), 3–12.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory(2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Okleshen, M., & Hoyt, R. (1996). A cross cultur-al comparison of ethiccultur-al perspectives and deci-sion approaches of business students: United States of America versus New Zealand. Journal of Business Ethics, 15,537–549.

Payne, S. L., & Nantz, K. S. (1994). Social accounts and metaphors about cheating. Col-lege Teaching, 42(3), 90–97.

Peterson, R. A. (1994). A meta-analysis of