A Multi-Study

Investigation of

Outcomes of

Franchisees’ Affective

Commitment to Their

Franchise Organization

Karim Mignonac

Christian Vandenberghe

Rozenn Perrigot

Assâad El Akremi

Olivier Herrbach

Franchisees’ affective organizational commitment refers to the degree to which franchisees experience an emotional attachment to their franchise organization. Using a social exchange theory perspective, this research reports four studies that explore the relationship between franchisee’s affective commitment and franchisee outcomes. We found that affective com-mitment to the franchise organization was positively related to franchisee objective perfor-mance (Study 1) and intent to acquire additional units (Study 2), and negatively related to franchisee opportunism (Study 3) and intent to leave the franchise organization, particularly when continuance commitment (i.e., commitment based on the cost associated with mem-bership to the franchise) was low (Study 4). The implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

Franchising is a popular business arrangement that involves cooperation between an entrepreneurially minded firm—i.e., the franchise organization (or franchisor)—and several individual entrepreneurs—i.e., the franchisees (Combs, Ketchen, Shook, & Short, 2011). Typically, a franchisor that already has a successful product or service enters a continuing contractual relationship with franchisees operating under the franchisor’s trade

Please send correspondence to: Karim Mignonac, tel.: (33) 5-61-63-38-87; e-mail: karim.mignonac@ univ-tlse1.fr, to Christian Vandenberghe at [email protected], to Rozenn Perrigot at rozenn. [email protected], to Assâad El Akremi at [email protected], and to Olivier Herrbach at [email protected].

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

© 2013 Baylor University

461 May, 2015

name and usually with the franchisor’s guidance, in exchange for an investment fee and ongoing royalties (Pappu & Strutton, 2001, p. 113). Past research has essentially addressed the economic aspects of the franchisor–franchisee relationship (Combs, Ketchen, & Short, 2011), pointing out the instrumental basis of franchisee behavior (Gassenheimer, Baucus, & Baucus, 1996).

However, a broader understanding of the franchisor–franchisee relationship might be gained by recognizing that franchisees “are not single economic actors simply reacting to economic incentive mechanisms but are social actors embedded within a complex set of interpersonal relationships” (Lawrence & Kaufmann, 2011, p. 299). These relationships can be understood through the lens of Social Exchange Theory (SET), which states that exchange interactions result in both economic and social outcomes that engender obli-gations between the parties, expectations of future rewards, and a willingness to invest time and effort in the relationship (Lambe, Wittman, & Spekman, 2001; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). However, social exchange theorists have often considered economic and social exchange separate forms of relationship. Social exchange differs from economic exchange in that (1) trust and socio-emotional components are central ingredients, (2) personal investment in the relationship is essential to its maintenance over time, and (3) a long-term orientation is required for mutual obligations to be fulfilled (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Shore, Tetrick, Lynch, & Barksdale, 2006). While this separation of economic and social exchange might be relevant to employee–employer relationships, it is less applicable to franchising because franchisee–franchisor relationships are sealed in strong economic inducements from the start. Franchisees make significant idiosyncratic investments (e.g., lump sum payment, annual royalty fee based on sales) and franchisors provide agreed-upon assistance in management, operational procedures, training, and advertising (Shane, 1996). As a result, both parties have a vested interest to maintain the relationship over time. Thus, it is not clear that SET holds to the same extent among franchises, where economic forces might alone be sufficient.

Although economic conditions may appear to suffice to build a mutually beneficial relationship between the franchisee and the franchisor, SET suggests that the social component of the relationship still represents a major driver of the future outcomes associated with it. We focus on affective commitment because prior research shows that it is central to the social component of exchange relationships (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Lawler & Thye, 1999). Affective commitment refers to an emotional attachment to an organization based on a sense of identification to its goals and values (Meyer & Allen, 1991; Meyer, Becker, & Vandenberghe, 2004). Thus, although franchising is thought to be an efficient solution to the agency problem of having the principal (i.e., the franchisor) monitor and control the agent (i.e., the franchisee) by sealing the relationship into eco-nomic and contractual constraints (Shane, 1996), franchisees’ affective commitment to the relationship represents an important driver on its own of future outcomes because it reflects acommitment to the franchisor’s goals.

(i.e., performance, acquisition of new outlets, opportunism, and intent to leave the franchise), even though franchising is characterized by strong economic incentives. We base our reasoning on the idea that economic exchange relationships become mutually beneficial to the extent that relational norms emerge (Lambe et al., 2001), and the current relationship is viewed as more rewarding than other exchange alternatives (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). This might happen when the franchisee experiences a sense of affective commitment to the franchise.

In the following sections, we present four studies that examine the relationships between franchisee’s affective commitment to the franchisor and franchisee performance (Study 1), intent to acquire additional units (Study 2), opportunism (Study 3), and intent to leave the franchisor (Study 4). Across these studies, our intention is to highlight how affective commitment can work as a driver of franchise outcomes and franchisor– franchisee relationships, which take place in an incentive intensive context.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Much of the research on franchisee–franchisor relationships has been conducted through the lens of economic exchanges whereby franchisees’ behavior is determined by the so-called “carrot-and-stick” approach (the carrot being the residual profits and the stick the loss of ex-post rents; Lawrence & Kaufmann, 2011). This research conceives franchisees’ behavior as being regulated by external rewards. In this view, franchisee’s behavior reflects an externally regulated motivation, i.e., the reason for engaging in the behavior (e.g., staying with the franchise organization or making the franchise profitable) is external to the individual. This approach is consistent with an economic exchange perspective. Economic exchanges are give-and-take relationships, based on tangible inducements, and typically short-term (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Shore et al., 2006).

However, some scholars have recently criticized the exclusive focus on economic exchanges (e.g., Dant, Weaven, Baker, & Jeon, 2013; Weaven, Grace, & Manning, 2009) and recognized that franchisee motivation is “more varied and complex than being simply an expression of profit maximization desires” (Stanworth & Curran, 1999, p. 338). This stance is compatible with the tenets of SET. Contrary to the economic exchange perspec-tive, SET proposes that, in the longer term, the maintenance of constructive relationships requires and is explained by mutual commitments among partners (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005), which are intrinsically tied to emotional attachment to the relationship. Following this logic, affective commitment to the franchisor, which emerges in the context of ongoing and repeated social exchanges, constitutes an important driver of the franchisee’s willingness to act in the best interests of the franchisor and invest effort into making the relationship efficient in the long term.

Franchising represents an organizational form where the franchisee receives the right to sell a product or service using a brand name in return for a lump sum and annual royalties, and the franchisor is expected in return to provide assistance in management, training, advertising, and operational procedures (Norton, 1988; Shane, 1996). While these conditions create strong economic incentives that encourage parties to cooperate and ensure the relationship is mutually beneficial (hence making exchange alternatives less attractive; Lambe et al., 2001; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959), SET would predict that these inducements would lead to positive outcomes only if relational exchange norms emerge in which partners experience a sense of commitment to the relationship’s goals. For example, if the franchisee feels that the franchisor fails to some extent to provide timely

and substantial support for managing outlets (which may be related to time constraints on the part of the franchisor; Norton), he/she may reduce his/her commitment and potentially engage in opportunism. The point is that franchisees’ affective commitment is an indicator that the relationship is not asymmetrical and exploitative (Gundlach, Achrol, & Mentzer, 1995) and that significant effort maintaining the relationship is expected to be exerted by the parties in the future. Following this logic, franchisees’ affective commitment should be tied to all of the behaviors that ultimately help to maintain long-term exchanges with the franchisor. For example, research conducted among employees suggests that affective commitment is a relevant predictor of firm performance (e.g., Gong et al., 2009), organi-zational citizenship behavior (e.g., Meyer et al., 2002), and reduced turnover (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000; Meyer et al.).

Performance

Successful franchise organizations depend heavily on their franchisees to perform well. However, the determination of outlet performance remains poorly understood (Michael & Combs, 2008). SET suggests that the economic and social outcomes tied to the exchange contribute and reinforce one another to create the conditions for outlet performance. As argued above, franchisor–franchisee exchanges are tinged by strong economic inducements that both make exchange alternatives less attractive and encourage franchisees to become self-motivated in managing their business. However, economic incentives are not enough by themselves to ensure that parties invest significant inputs in the future success of the exchange. For this to happen, relational norms need to emerge which are typically reflected in mutual commitments to the relationship’s goals (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Lambe et al., 2001). In other words, SET states that there should be some balance among the economic inputs generated by the parties over time so that interdependence is achieved and the relationship is mutually rewarding (Lambe et al.). For example, the provision of assistance (e.g., support to advertising and opera-tional procedures) that is proporopera-tional to and meets franchisees’ needs may instill the expectation of future positive outcomes. These conditions should lead to a franchisee’s affective commitment to the relationship, and ultimately result in increased effort promoting outlet performance.

Franchisees with high affective commitment may work toward outlet performance through a variety of means. For example, they may engage in customer-focused citizen-ship behavior (such as going out of their way to help a customer or attending to customer needs) that in the end would lead to stronger customer satisfaction and indirectly increased sales performance (e.g., Schneider, Ehrhart, Mayer, Saltz, & Niles-Jolly, 2005). Alterna-tively, they may engage in cooperative behaviors directed at their own employees, taking steps toward creating a service climate in their franchise (e.g., Schneider, White, & Paul, 1998), or developing strong social exchange relationships with employees (Liao & Chuang, 2007). This would indirectly instill a sense of service toward customers among their employees which may lead to higher sales performance.

productivity, and profit (among others). Thus, based on the above, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Franchisees’ affective commitment to the franchise organization is positively related to franchisees’ performance.

Intent to Acquire Additional Units

From the franchisor’s perspective, multi-unit franchising is a growth strategy (Kaufmann & Dant, 1996) that allows franchisees to open additional units, either one unit at a time (sequential multi-unit strategy), or multiple units at the outset (area devel-opment multi-unit strategy). Scholars have studied how and why franchisors benefit from multi-unit franchising (Hussain & Windsperger, 2009; Perryman & Combs, 2012), but very little is known about the factors affecting franchisees’ intent to contribute to this strategy, that is, to increase the number of units they own within the same franchise organization.

Within a SET perspective, the acquisition of additional units represents a significant investment in the future prospects of the relationship. Such investment can only be granted if the franchisee perceives the relationship with the franchisor as being open-ended, based on mutual commitments, and rewarding in the long term. These conditions, which reflect franchisee affective commitment, should happen when the franchisee expects the exchange to generate (social and economic) benefits that match his/her expected rewards (i.e., a comparison levelperspective) and to be more rewarding than other exchange alternatives (i.e., acomparison level of alternativesperspective) (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). In other words, franchisees with high levels of affective commitment envision the rewarding opportunities that the acquisition of new units affords. Hence, they are likely to see the acquisition of additional outlets as an attractive goal. This leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: Franchisees’ affective commitment to the franchise organization is positively related to franchisees’ intent to acquire additional units.

Opportunism

Franchisee opportunism refers to the extent to which franchisees act according to their self-interests in order to achieve their own goals despite possible damage to franchisors (Jambulingam & Nevin, 1999). Examples of franchisee opportunism include free-riding on the franchisor’s brand name and the efforts of other franchisees (Kidwell, Nygaard, & Silkoset, 2007); withholding information from the franchise organization (El Akremi, Mignonac, & Perrigot, 2011); or not complying with the franchisor’s standards, policies, and relational norms (Davies, Lassar, Manolis, Prince, & Winsor, 2011; El Akremi et al.). Although franchisors may to some degree accept certain forms of opportunism on the part of their franchisees (Cox & Mason, 2007; Kidwell & Nygaard, 2011), franchisee opportunism is largely discouraged because it jeopardizes the performance and survival of both the franchisor and franchisees (Kidwell et al.; Szulanski & Jensen, 2006; Winter, Szulanski, Ringov, & Jensen, 2012). Thus, overcoming opportunism is a major challenge for franchise systems (Davies et al.).

Franchisees with high affective commitment perceive that there is a balance between the efforts they put forth and the benefit and support they gain from the franchisor. In other

words, they perceive that relational norms govern the exchanges which representagreed uponmechanisms of controlling parties’ behavior without the difficulties associated with asymmetrical exchanges created by coercion or power (Lambe et al., 2001). Therefore, franchisees’ affective commitment is an indicator of a mutually rewarding exchange in which the expected rewards outweigh the selfish perspective of free-riding and opportun-ism. Thus, these individuals should be reluctant to engage in opportunistic behaviors that would otherwise compromise the long-term survival of the relationship and threaten the interests of the franchisor. Indirect evidence that this could be the case can be found in research reporting a negative relationship between affective commitment and deviant or counterproductive work behavior (e.g., Dalal, 2005; Gill, Meyer, Lee, Shin, & Yoon, 2011). This leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: Franchisees’ affective commitment to the franchise organization is negatively related to franchisees’ opportunism.

Intent to Leave the Franchise Organization

We define franchisees’ intent to leave as the perceived likelihood that a franchisee will voluntarily terminate the relationship with the franchisor when his/her current franchise agreement expires. Retaining franchisees is a major challenge for franchise organiza-tions because franchisee exits have detrimental effects on the chain’s growth (e.g., loss of royalties and financial resources to expand) and brand equity (e.g., competing ex-franchisees operating in a similar business; Frazer, Merrilees, & Wright, 2007). Since turnover intention has been found to be a strong antecedent of actual turnover behavior (Griffeth et al., 2000), studying the precursors of franchisees’ turnover intention is impor-tant and allows a franchise organization to take action before the intention turns into actual behavior (Meek et al., 2011).

Hypothesis 4: Franchisees’ continuance commitment moderates the relationship between franchisees’ affective commitment to the franchise organization and intent to leave, such that this (negative) relationship is stronger when continuance commitment is low vs. high.

Study 1: Relationship With Performance

Sample and Data Collection

We obtained the agreement of a French franchise organization that retails beauty care products globally to conduct a study about their franchisees’ attitudes and performance. In early 2009, we mailed a questionnaire to all 164 franchisees located in France, with a cover letter outlining the franchisor’s support for the research. We received 92 completed questionnaires, which represents a 56.1% response rate. Franchise headquarters provided data about product sales revenue and retail space for each franchisee for years 2008 and 2009. Usable data on franchisee responses, sales revenue, and retail space were available for 79 franchisees (48.17% of the original sample). To estimate the likelihood of a nonresponse bias, we compared respondents and nonrespondents on franchise organization-provided variables (i.e., product sales revenue and retail space). We found no significant differences in the responses (p>.05), which suggests that nonresponse bias was not a major concern in this study.

Measures

All items (see Appendix) were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1= com-pletely disagree; 5=completely agree) unless specified otherwise. Except for product sales revenue and retail space data that were collected from franchisors, all the other data were collected from franchisees.

Affective Commitment. We measured affective commitment to the franchise organization

by slightly modifying the French version of Meyer, Allen, and Smith’s (1993) 6-item scale (Vandenberghe & Bentein, 2009). We replaced the word “organization” with “franchise organization” in all items. To minimize measurement errors due to careless responding or fatigue, we positively worded all items (Merritt, 2012). A sample item is “I really feel that I belong in this franchise organization” (a =.92).

Performance. We operationalized franchisee performance through two measures: (1) the

ratio between the yearly revenue earned from store product sales (in euros) and the total area of retail space (in square meters); this ratio represents sales per unit and is a measure of productivity commonly used in the retail industry (Fenwick & Strombom, 1998; Litz & Stewart, 2000); and (2) yearly sales revenue, which represents an absolute measure of sales performance.

Control Variables. We controlled for multi-unit ownership because research suggests that

multi-unit franchisees can benefit from the experience of their previously opened outlets, and thus be more productive than single-unit franchisees (Darr, Argote, & Epple, 1995). We also controlled for the number of employees, because this may explain variations in store performance (Arnold, Palmatier, Grewal, & Sharma, 2009). In addition, we controlled for age and tenure in the franchise organization, in order to hold constant the

variance due to human capital variables. We also controlled for the market potential of the franchisee’s geographic location with the number of potential customers for each franchisee as calculated by the franchisor and performance in 2008 (either sales revenue per square meter or sales revenue). Finally, we additionally controlled for retail space in the regression equation for sales revenue.

Results

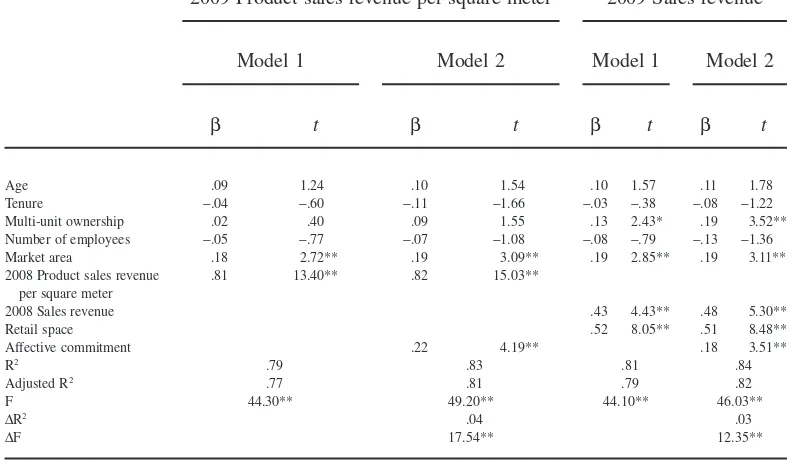

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations for Study 1 variables. Of interest, affective commitment was positively related to 2008 and 2009 sales revenue per square meter (r=.26,p<.05, and r=.32,p<.01, respectively) but not to 2008 and 2009 sales revenue (r=.08, ns, and r=.08, ns, respectively). Thus, the productivity measure (sales revenue per square meter) was significantly related to fran-chisee affective commitment, plausibly because this measure better reflects whether the outlet is well managed, while the measure of overall performance (sales revenue), which may be more sensitive to market potential, was not. Hypothesis 1 predicted that franchi-sees’ affective commitment would be positively related to franchisee performance. We tested hypothesis 1 using hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses. We entered the control variables in Model 1 and added affective commitment in Model 2. As can be seen from Table 2 (Model 2), affective commitment was significantly and positively related to 2009 sales revenue per square meter (b =.22,p<.01) and 2009 sales revenue (b =.19,p<.01), controlling for all the other variables, namely 2008 measures of these outcomes. Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported.

Study 2: Relationship With Intent to Acquire Additional Units

Sample and Data Collection

As part of a larger project, the research team personally contacted 100 franchise organizations at their leadership meetings or at franchise exhibitions. We targeted fran-chisors listed in the 2008 directory of the French Franchise Federation with at least 10 units and operating in France for more than 5 years. We approached franchisors and asked them whether they would agree to participate in a study of business strategies in franchise organizations. We also asked them if they would accept that we survey their franchisees about their work attitudes. We offered a free report of the study’s results to franchisors in return for their participation (which involved completing a questionnaire—see Measures subsection for a description of franchisor variables—and the provision of a list of their members). Eighty franchisors returned usable questionnaires and supplied contact infor-mation for all their franchisees. Key informants among franchisors were chief executive officers, executive vice presidents of franchising, or directors of franchise development. T-tests and chi-square statistics showed no significant differences (p>.10) between respondents and nonrespondents among key informants on franchise organization age, size, and industry, proportion of franchised outlets, and level of internationalization.

Table 1

Study 1 and 3 Means, Standard Deviations, Reliabilities, and Correlations

Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Study 1 (N=79)

1. Age 46.42 9.29 —

2. Tenure in the franchise organization (years) 17.49 8.53 .63** — 3. Multi-unit ownership (1=multi-unit franchisee) .10 .29 .00 .04 —

4. Number of employees 5.10 2.70 .04 .17 .35** —

5. Market area (log. population size) 4.66 .33 .19 .31** .29* .55** — 6. Retail space (square meter) 53.03 21.94 -.23* -.22 .27* .49** .36** —

7. Affective commitment to the franchise organization 4.39 .49 .15 .32** -.02 .07 .08 -.14 (.80) 8. 2008 Product sales revenue per square meter 9,649.04 4,757.40 .32** .28* .22 .28* .26* -.48** .26* — 9. 2009 Product sales revenue per square meter 10,046.16 4,004.45 .35** .28* .23* .28* .38** -.30** .32** .87** — 10. 2008 Sales revenue 462,310.11 212,230.25 .09 .14 .28* .84** .52** .43** .08 .46** .41** — 11. 2009 Sales revenue 506,433.76 258,395.34 .04 .04 .41** .68** .60** .75** .08 .08 .35** .72** — Study 3 (N=529)

1. Age 44.04 8.98 —

2. Gender (1=male) .35 .48 .11* —

3. Tenure in the franchise organization (years) 5.43 5.31 .31** -.07 — 4. Multi-unit ownership (1=multi-unit franchisee) .20 .40 .02 .10* .14** —

5. Positive affectivity 4.22 .51 -.09* -.05 -.05 .03 (.81)

6. Negative affectivity 2.34 .81 -.06 .02 -.05 -.07 -.30** (.80)

7. Self-reported performance 3.07 .85 -.01 .10* .08 .08 .25** -.24** (.89)

8. Affective commitment to the franchise organization 3.72 .86 .01 .02 .01 .08* .24** -.15** .32** (.92)

9. Opportunism 2.01 .52 -.06 -.01 .02 -.02 -.28** .22** -.24** -.46** (.72)

*p<.05; **p<.01

Note:Pearson product moment correlations are reported for pairs of continuous variables, Spearman rank correlations are reported for pairs of continuous and dichotomous variables, and Phi correlations are reported for pairs of dichotomous variables. Internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alphas) appear across the diagonal in parentheses.

469

May

,

Measures

All items (see Appendix) were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1= com-pletely disagree; 5=completely agree) unless specified otherwise. We collected data regarding affective commitment to the franchise organization, intent to acquire additional units, demographics, and self-reported performance from franchisees’ questionnaires. Additionally, data regarding franchisors’ strategies for multi-unit ownership were col-lected from franchisors’ questionnaires. Finally, we gathered basic information about franchisors, such as age, size, contract length, and minimum cash required to open a franchise unit, directly from the French Franchise Federation directory.

Affective Commitment. We measured affective commitment to the franchise organization

using the same scale as in Study 1 (a =.93).

Intent to Acquire Additional Units. We developed a 3-item scale to measure franchisees’

intent to acquire additional units. A sample item is “I intend to own one or several additional units of this franchise organization within the next two years” (a =.86).

Franchisee-Level Control Variables. Control variables were chosen based on their

potential influence on growth intentions among small business owners: these included

Table 2

Study 1 Ordinary Lead Square (OLS) Regression Analyses Predicting Franchisee Performance

2009 Product sales revenue per square meter 2009 Sales revenue

Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2

b t b t b t b t

Age .09 1.24 .10 1.54 .10 1.57 .11 1.78

Tenure -.04 -.60 -.11 -1.66 -.03 -.38 -.08 -1.22

Multi-unit ownership .02 .40 .09 1.55 .13 2.43* .19 3.52**

Number of employees -.05 -.77 -.07 -1.08 -.08 -.79 -.13 -1.36

Market area .18 2.72** .19 3.09** .19 2.85** .19 3.11**

2008 Product sales revenue per square meter

.81 13.40** .82 15.03**

2008 Sales revenue .43 4.43** .48 5.30**

Retail space .52 8.05** .51 8.48**

Affective commitment .22 4.19** .18 3.51**

R2 .79 .83 .81 .84

Adjusted R2 .77 .81 .79 .82

F 44.30** 49.20** 44.10** 46.03**

DR2 .04 .03

DF 17.54** 12.35**

*p<.05; **p<.01

age, gender, tenure with the franchise organization, and multi-unit ownership (Dant et al., 2013; Morrison, Breen, & Ali, 2003; Weaven & Frazer, 2003). Additionally, we controlled for number of units owned because cash flow from other units may influence expansion. We also controlled for franchisees’ perceptions of performance because success may tempt franchisees to acquire additional units. We used a 3-item scale to measure perceptions of performance (Samaha, Palmatier, & Dant, 2011). The items were “As compared to other similar franchisees, our performance is very high in terms of: (1) sales growth, (2) profit growth, (3) overall profitability” (a =.90).

Franchise Organization-Level Control Variables. In order to account for the variance

potentially explained by idiosyncratic characteristics of the franchise organizations, we controlled for age and size of franchise organizations, length of franchise contracts, minimum cash required to open a franchise unit, and strategy for multi-unit franchising. We developed a 4-item scale to assess franchisors’ multi-unit strategy (e.g., “We encour-age our franchisees to own more than one unit”;a =.74).

Measurement Analyses

We compared two nested confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models. The baseline two-factor measurement model comprising affective commitment and intent to own additional units yielded a satisfactory fit to the data:c2(26)=118.92,p

<.01; comparative fit index (CFI)=.99; non-normed fit index (NNFI)=.98; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=.076; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)=.025. This model proved superior to a single-factor model combining the two constructs (Dc2 [1]=794.73,p<.01). These results supported the convergent and discriminant validity of our study measures.

To test for common method variance, we compared our theoretical model to a model that also included an orthogonal method factor on which all items had a loading (in addition to a loading on their intended factor). The model that included the method factor resulted in a good fit (c2 [17]=37.62,p

<.01; CFI=.99; NNFI=.99; RMSEA=.045; SRMR=.016), and outperformed the model with no method factor (Dc2 [9]=127.57, p<.01). Further analyses of factor loadings revealed that 22% of the variance was accounted for by the method factor, which is similar to percentages typically found in other studies (Lance, Dawson, Birkelbach, & Hoffman, 2010). The poor fit of the one-factor model (NNFI=.80; RMSEA=.232) also suggests that common method vari-ance does not appear to be an excessive threat to this study. Hence, we proceeded with hypothesis testing.

Results

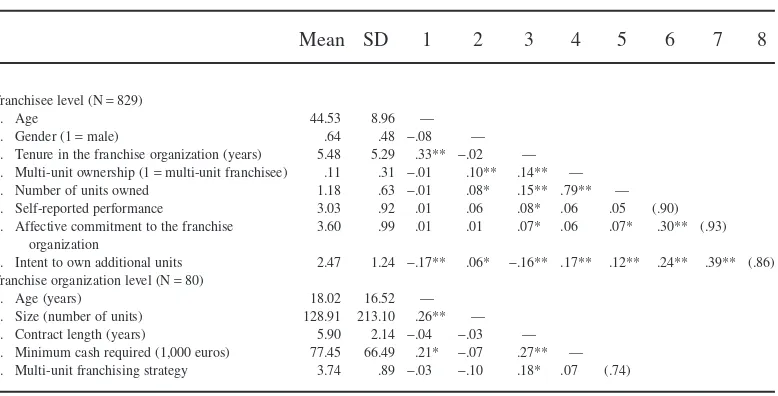

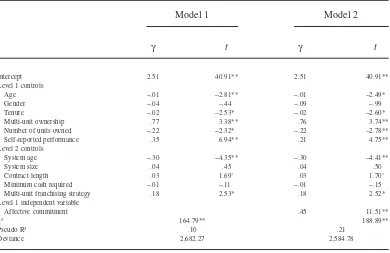

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations for Study 2 variables. As can be seen, age and tenure correlated negatively with the intention to acquire additional outlets (r= -.17,p<.01, and r= -.16, p<.01, respectively), sug-gesting that those who expand their units are younger and less tenured. In contrast, being a male franchisee (r=.06,p<.05), being a multi-unit franchisee (r=.17,p<.01), number of units (r=.12,p<.01), perceived performance (r=.24,p<.01), and affective commitment (r=.39,p<.01) were all positively associated with intent to own more units. Hypothesis 2 predicted that franchisees’ affective commitment would relate positively to franchisees’ intent to own additional units. We used hierarchical linear modeling

(HLM) to account for the multi-level and nested structure of the data (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). To justify HLM as the appropriate analytic technique for testing this hypoth-esis,1we first ran a null model with no predictors and intent to acquire additional units as the dependent variable. This analysis revealed that franchisees’ intent to own additional units varied significantly across franchise organizations (c2=184.72 [70], p

<.01; ICC(1)=.13), with 13% of its variance being explained by the franchise organization to which franchisees belonged. Consequently, we proceeded to test hypothesis 2 using HLM. We entered control variables in Model 1 and added affective commitment in Model 2. The results for Model 2, as reported in Table 4, indicated a positive and statistically significant relationship between affective commitment and intent to own additional units (g =.45, p<.01), controlling for all other variables. Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported.

Study 3: Relationship With Opportunism

Sample and Data Collection

The sampling frame used for this study was a database of 12,000 franchisee contacts located in France. We developed this database from 737 business-format franchise

1. In the present study, franchisees (Level 1) were nested within franchise organizations (Level 2). HLM allows an examination of the relationships across levels of analysis by simultaneously estimating both within-organization and between-organization variances in the dependent variable (i.e., intent to own addi-tional units). However, if there is little or no variance in the dependent variable across franchise organizations, the assumptions of OLS regression are not violated, and HLM is not required to examine cross-level relationships (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Table 3

Study 2 Means, Standard Deviations, Reliabilities, and Correlations

Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Franchisee level (N=829)

1. Age 44.53 8.96 —

2. Gender (1=male) .64 .48 -.08 —

3. Tenure in the franchise organization (years) 5.48 5.29 .33** -.02 — 4. Multi-unit ownership (1=multi-unit franchisee) .11 .31 -.01 .10** .14** —

5. Number of units owned 1.18 .63 -.01 .08* .15** .79** —

6. Self-reported performance 3.03 .92 .01 .06 .08* .06 .05 (.90)

7. Affective commitment to the franchise organization

3.60 .99 .01 .01 .07* .06 .07* .30** (.93)

8. Intent to own additional units 2.47 1.24 -.17** .06* -.16** .17** .12** .24** .39** (.86) Franchise organization level (N=80)

1. Age (years) 18.02 16.52 —

2. Size (number of units) 128.91 213.10 .26** —

3. Contract length (years) 5.90 2.14 -.04 -.03 —

4. Minimum cash required (1,000 euros) 77.45 66.49 .21* -.07 .27** — 5. Multi-unit franchising strategy 3.74 .89 -.03 -.10 .18* .07 (.74)

*p<.05; **p<.01

organizations listed in the 2008 directory of the Fédération Française de la Franchise (i.e., the French Franchise Federation). We retained only those franchisors with at least 10 units and operating in France for more than 5 years. We obtained the names and addresses of franchisees from their respective websites and the Yellow Pages phone directory. To avoid employees or managers of the franchisee mistakenly receiving and completing the survey questionnaire, we included in the database only prospective participants for whom complete professional and contact information were available. Moreover, questionnaires were addressed to the franchisees personally. In total, 3,000 franchisees were randomly selected from the database and invited to participate in the survey in April 2009.

We received 529 completed and usable questionnaires, corresponding to a response rate of 17.6%. To estimate the likelihood of a nonresponse bias, we compared early and late respondents on all of the variables listed in Table 1 and found no significant differ-ences in the responses (p>.05), which suggests that nonresponse bias was not a major concern in this study.

Measures

All items were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=completely disagree; 5=completely agree) unless specified otherwise. Scale items are reported in the Appen-dix. All of the data were collected from the franchisees.

Table 4

Study 2 HLM Analyses Predicting Intent to Own Additional Units

Model 1 Model 2

g t g t

Intercept 2.51 40.91** 2.51 40.91**

Level 1 controls

Age -.01 -2.81** -.01 -2.49*

Gender -.04 -.44 -.09 -.99

Tenure -.02 -2.53* -.02 -2.60*

Multi-unit ownership .77 3.38** .76 3.74**

Number of units owned -.22 -2.32* -.22 -2.78**

Self-reported performance .35 6.94** .21 4.75**

Level 2 controls

System age -.30 -4.35** -.30 -4.41**

System size .04 .45 .04 .50

Contract length .03 1.69† .03 1.70†

Minimum cash required -.01 -.11 -.01 -.15

Multi-unit franchising strategy .18 2.53* .18 2.52*

Level 1 independent variable

Affective commitment .45 11.51**

c2 164.79** 188.89**

Pseudo R2 .10 .21

Deviance 2,682.27 2,584.78

†p

<.10; *p<.05; **p<.01

Note: Fixed effects (g) are reported. Pseudo R2is calculated based on proportional reduction of error variance due to

predictors in the models of Table 4 (Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

Affective Commitment. We measured affective commitment using the same scale as in Study 1 (a =.80).

Opportunism. We used Jambulingam and Nevin’s (1999) 7-item scale to measure

franchisee opportunism. We translated this measure into French, and followed back-translation procedures (Brislin, 1980). A sample item is “I sometimes withhold informa-tion that would help my franchisor to run his/her business” (a =.72).

Control Variables. Control variables included age, gender, tenure in the franchise

orga-nization, and multi-unit ownership, because they account for variance in franchisee opportunism (El Akremi et al., 2011; Jambulingam & Nevin, 1999). We also controlled for franchisee affectivity (i.e., stable individual differences in the tendency to experience positive and negative mood states), because of its demonstrated relationships with work-place deviance (Lee & Allen, 2002), and thus its likely relationship with our outcome variable. In addition, controlling for affectivity may help reduce potential common-method effects (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). We assessed trait positive (5 items;a =.81) and negative (5 items;a =.80) affect using the items from the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form (Thompson, 2007). We also controlled for franchisees’ perceptions of performance, because performance may be related to franchisee opportunism (Dunlop & Lee, 2004). We used the same scale of self-reported performance as in Study 2 (Samaha et al., 2011) (a =.90).

Measurement Analyses

We tested and compared the fit of a series of nested CFA models. The baseline four-factor model included affective commitment (AC), positive affectivity (PA), negative affectivity (NA), self-reported performance (PF), and opportunism (OP): it yielded a satisfactory fit to the data: c2 (289)=829.54, p

<.01; CFI=.95; NNFI=.94; RMSEA=.061; SRMR=.056. This model proved superior to simpler representations of the data, including three-factor models obtained by combining AC and PA (Dc2[4]=1,131.27,p

<.01); AC and NA (Dc2[4]=1,011.76,p

<.01); AC and PF (Dc2 [4]=774.57, p<.01); PA and NA (Dc2 [4]=717.53, p

<.01); a two-factor model com-bining AC, PA, NA, and PF (Dc2 [9]=3,015.30, p

<.01); and a single-factor model combining all the study constructs (Dc2[11]=3,286.68,p

<.01). In sum, these results support the convergent and discriminant validity of our measures.

To test for common method variance, we added an uncorrelated method factor to the 4-factor model (Podsakoff et al., 2003). We allowed all items to load on their intended construct and on the method factor. The model that included the method factor resulted in a good fit (c2 [263]=647.99, p

<.01; CFI=.96; NNFI=.96; RMSEA=.054; SRMR=.047) and improved over the fit obtained for the measurement model alone (Dc2 [26]=204.19, p

<.01), thus indicating the presence of a method effect. Further analyses of factor loadings revealed that 14% of the variance was accounted for by the method factor, a proportion which compares favorably to estimates of the pervasiveness of method effects in organizational research (Lance et al., 2010). Thus, common method variance did not seriously affect our ability to test our hypotheses.

Results

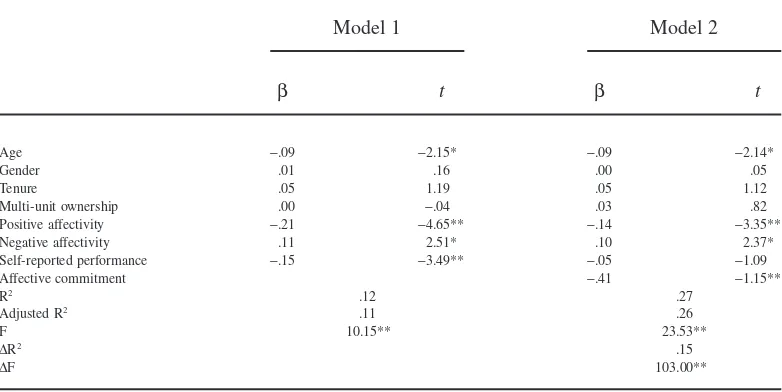

commitment correlated negatively with franchisees’ opportunism (r= -.24,p<.01, and r= -.46, p<.01, respectively). Hypothesis 3 predicted that there would be a negative relationship between franchisees’ affective commitment and opportunism. We tested hypothesis 3 using hierarchical OLS regression analyses. We entered control variables in Model 1 and added affective commitment in Model 2. Table 5 shows that in Model 2 there is a negative and significant relationship between affective commitment and opportunism (b = -.41,p<.01), controlling for all the other variables. Thus, hypothesis 3 was supported.

Study 4: Relationship With Intent to Leave

Sample and Data Collection

For purposes of this study, we drew a separate and independent sample of 3,000 contacts from the same database of 12,000 franchisee contacts already used in Study 3 (i.e., the 3,000 contacts used in Study 3 were excluded). We collected data in June 2009 using the same procedure as in Study 3. In total, we received 417 completed and usable questionnaires, for a response rate of 13.90%. We compared early and late respondents on the study variables and found no significant differences (p>.05), which suggests that nonresponse bias was not a concern.

Measures

All items (see Appendix) were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=

completely disagree; 5=completely agree) unless specified otherwise. All of the data were collected from the franchisees.

Table 5

Study 3 Regression Analyses Predicting Opportunism

Model 1 Model 2

b t b t

Age -.09 -2.15* -.09 -2.14*

Gender .01 .16 .00 .05

Tenure .05 1.19 .05 1.12

Multi-unit ownership .00 -.04 .03 .82

Positive affectivity -.21 -4.65** -.14 -3.35**

Negative affectivity .11 2.51* .10 2.37*

Self-reported performance -.15 -3.49** -.05 -1.09

Affective commitment -.41 -1.15**

R2 .12 .27

Adjusted R2 .11 .26

F 10.15** 23.53**

DR2 .15

DF 103.00**

*p<.05; **p<.01

Note: Standardized regression coefficients (b) are reported.

Affective Commitment. We measured affective commitment to the franchise organization using the same scale as in the previous three studies (a =.81).

Continuance Commitment. We assessed franchisees’ continuance commitment using

the revised 6-item scale of Continuance Organizational Commitment (Powell & Meyer, 2004). This scale measures the high-sacrifice component of continuance commitment, which represents the core essence of the construct (Powell & Meyer). We replaced the word “organization” with “franchise organization” in all items. A sample item was “Leaving this franchise organization now would require considerable personal sacrifice” (a =.84).

Intent to Leave. We developed two items to measure franchisees’ intent to leave (e.g.,

“How likely is it that you will voluntarily leave your franchise organization when your current franchise agreement expires?”). The scale anchors ranged from very unlikely(1) tovery likely(5). The Pearson correlation (r) between these two items was .55 (p<.01). Note that although this scale was anad hocmeasure of intent to leave and comprised only two items, it closely parallels similar 2-item measures of the construct (e.g., Bentein, Vandenberg, Vandenberghe, & Stinglhamber, 2005; Hom & Griffeth, 1991).

Control Variables. We included franchisee’s age, gender, and tenure in the franchise

organization as controls as prior research found them to be correlated with affective commitment and turnover intention (Jaros, 1997; Meyer et al., 2002). As research sug-gests that single-unit and multi-unit franchisee owners differ in terms of disposition toward their franchisors (Dant et al., 2013), we also controlled for multi-unit ownership. Finally, we controlled for self-reported performance using a 3-item scale that we specifi-cally developed for this study (a =.85). This allowed controlling for the possibility that franchisees who perceive their outlets as high performing would not consider leaving their franchise organization. Two items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree): “Compared to other franchisees in this chain, my outlet(s) is/are performing well” and “To date, I have been able to meet the business objectives for my outlets,” while the third item read as follows: “Based on the franchisor’s forecasts, the performance of my outlet(s) is (1) poor, (2) below expectations, (3) average, (4) above expectations, (5) outstanding.”

Measurement Analyses

We tested and compared a series of nested CFA models. The baseline four-factor measurement model, that comprised affective commitment (AC), continuance commit-ment (CC), self-reported performance (PF), and intent to leave (IL), yielded a satisfactory fit to the data: c2 (113)=427.18, p

<.01; CFI=.97; NNFI=.96; RMSEA=.082; SRMR=.058. This model proved superior to simpler representations of the data, includ-ing three-factor models obtained by combininclud-ing AC and CC (Dc2[3]=112.05, p

<.01), AC and IL (Dc2[3]=20.45,p

<.01), CC and IL (Dc2[3]=31.06,p<.01), and a single-factor model combining all the study constructs (Dc2[6]=331.82,p

<.01). In sum, these analyses attest to the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures used in this study.

To test for the presence of common-method variance, we repeated the procedure used in Studies 2 and 3. The model with the method factor resulted in a good fit (c2 [112]=426.24, p

p>.10). Analyses of factor loadings revealed that only 2.1% of the variance was accounted for by the method factor, which suggests that common-method variance did not significantly affect our ability to test study hypotheses.

Results

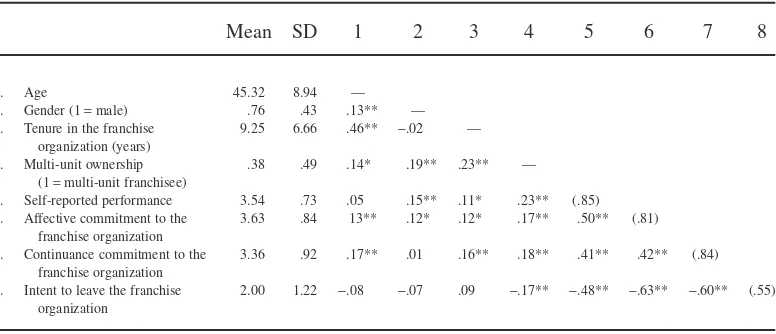

Table 6 presents the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations for Study 4 variables. As can be seen, multi-unit ownership (r= -.17,p<.01), self-reported performance (r= -.48, p<.01), and affective (r= -.63, p<.01) and continuance (r=

-.60, p<.01) commitment were significantly and negatively related to the intention to leave the franchise organization.

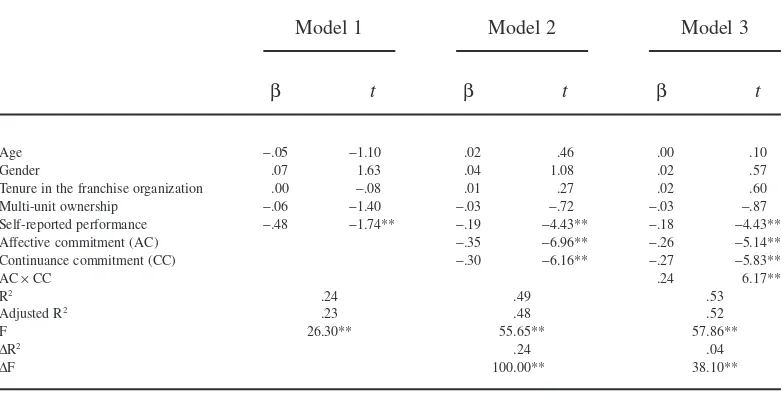

Hypothesis 4 predicted that low levels of franchisees’ continuance commitment would be associated with a stronger relationship between franchisees’ affective commit-ment and intent to leave. We tested hypothesis 4 using hierarchical OLS regression analyses and the moderated multiple regression procedures recommended by Aguinis and Gottfredson (2010). More precisely, we entered control variables in Model 1, added centered affective and continuance commitment in Model 2, and the affective¥

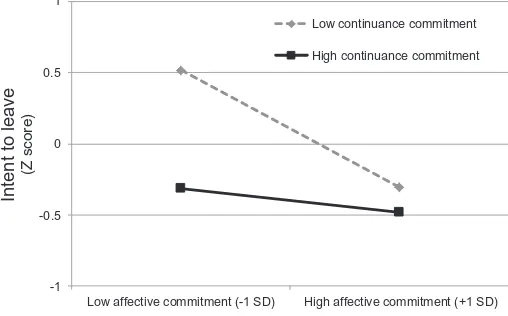

continuance commitment product term in Model 3. The results, which are displayed in Table 7, indicated a statistically significant interaction between affective and continuance commitment in predicting intent to leave (b =.24,p<.01).2

2. Note that, although not reported, we also measured normative commitment (i.e., commitment based on a sense of obligation toward the organization; Meyer & Allen, 1991) in Study 4. Controlling for normative commitment and for its interaction with affective commitment and continuance commitment did not change the results presented in Table 7. Moreover, none of these terms was significant.

Table 6

Study 4 Means, Standard Deviations, Reliabilities, and Correlations

Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1. Age 45.32 8.94 —

2. Gender (1=male) .76 .43 .13** —

3. Tenure in the franchise organization (years)

9.25 6.66 .46** -.02 —

4. Multi-unit ownership (1=multi-unit franchisee)

.38 .49 .14* .19** .23** —

5. Self-reported performance 3.54 .73 .05 .15** .11* .23** (.85) 6. Affective commitment to the

franchise organization

3.63 .84 13** .12* .12* .17** .50** (.81)

7. Continuance commitment to the franchise organization

3.36 .92 .17** .01 .16** .18** .41** .42** (.84)

8. Intent to leave the franchise organization

2.00 1.22 -.08 -.07 .09 -.17** -.48** -.63** -.60** (.55)

*p<.05; **p<.01

Note: N=417. Pearson product moment correlations are reported for pairs of continuous variables, Spearman rank correlations are reported for pairs of continuous and dichotomous variables, and Phi correlations are reported for pairs of dichotomous variables. Internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alphas or correlation for the 2-item scale of intent to leave) appear across the diagonal in parentheses.

To interpret the form of this interaction, we plotted the simple slopes at one standard deviation above and below the mean of continuance commitment (Aguinis & Gottfredson, 2010). As displayed in Figure 1, affective commitment was negatively related to intent to leave at low but not high levels of continuance commitment. To test this interpretation statistically, we compared each of the simple slopes to zero. When continuance commit-ment was low, the relationship between affective commitcommit-ment and intent to leave was negative and statistically significant (b= -.43, t= -8.70, p<.001). In contrast, when continuance commitment was high, the relationship between affective commitment and intent to leave did not differ significantly from zero (b= -.08,t= -1.27,p=.22). These results support hypothesis 4.

Discussion

This research reports four studies showing that franchisees’ affective commitment to the franchisor is positively related to franchisee objective performance (Study 1) and intent to acquire additional units (Study 2), and negatively related to opportunism (Study 3) and to intent to leave the franchise organization when continuance commitment is low (Study 4). These findings have important implications because even though research on regular employees has established the value of affective commitment as a predictor of a variety of outcomes including performance (e.g., Gong et al., 2009; Meyer et al., 2002), it was not known whether SET could help explain important outcomes in a context like franchising where economic incentives appear sufficient. The present investigation reveals that affective commitment, which represents a major SET construct, is an impor-tant vehicle through which social norms emerge among franchise partners and positive

Table 7

Study 4 OLS Regression Analyses Predicting Intent to Leave

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

b t b t b t

Age -.05 -1.10 .02 .46 .00 .10

Gender .07 1.63 .04 1.08 .02 .57

Tenure in the franchise organization .00 -.08 .01 .27 .02 .60

Multi-unit ownership -.06 -1.40 -.03 -.72 -.03 -.87

Self-reported performance -.48 -1.74** -.19 -4.43** -.18 -4.43**

Affective commitment (AC) -.35 -6.96** -.26 -5.14**

Continuance commitment (CC) -.30 -6.16** -.27 -5.83**

AC¥CC .24 6.17**

R2 .24 .49 .53

Adjusted R2 .23 .48 .52

F 26.30** 55.65** 57.86**

DR2 .24 .04

DF 100.00** 38.10**

*p<.05; **p<.01

outcomes are achieved. Thus, affective commitment adds explanatory power in a context dominated by strong economic incentives. Specific implications for theory and practice are outlined below.

Theoretical Implications

Our findings contribute to the scarce but growing literature on commitment in fran-chising. First, our research reveals that franchisees’ affective commitment is associated with stronger performance (as measured by product sales revenue per square meter and sales revenue). This represents a contribution to research aimed at identifying the factors that come into play in predicting franchisee performance (Michael & Combs, 2008; Morrison, 1997). This relationship can be explained using a SET perspective. Indeed, while SET states that there are both economic and social outcomes in exchange relation-ships (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959), the significant role of affective commitment in predicting outlet performance reveals that, besides the existence of strong economic incentives, the creation of relational norms strengthens goal interdependence and helps expectations of future rewards to come to reality (Lambe et al., 2001). In line with SET principles, franchisees’ affective commitment indicates that both parties invest significant resources into the exchange such that it is mutually rewarding. In essence, such commitment indicates partners’ willingness to “put forth the effort and make the investments necessary to produce mutually desirable outcomes” (Lambe et al., p. 11). Therefore, outlet perfor-mance appears a logical outcome of franchisees’ commitment to the relationship.

Second, our research examined intent to acquire additional units, a franchisee outcome that has been neglected in the multiple-unit franchising literature (Weaven & Frazer, 2003). While previous research suggests that multi-unit ownership is a desired and efficient way for franchisors to organize (Perryman & Combs, 2012), franchisees’ moti-vation to expand their business is not entirely rooted in economic incentives. Our finding of a positive association between franchisees’ affective commitment and intent to own additional units signals that relational support is a necessary component of the exchange,

Figure 1

Moderating Effect of Continuance Commitment on the Relationship Between Affective Commitment and Intent to Leave the Franchise Organization

-1 -0.5 0 0.5 1

Low affective commitment (-1 SD) High affective commitment (+1 SD)

Intent to leave

(Z score)

Low continuance commitment High continuance commitment

beyond the economic incentives, that explains why franchisees desire to expand their business. SET suggests that the expansion of efforts into the exchange relationship and the associated rewards are judged using two perspectives: the comparison level and the comparison level of alternatives (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). That is, franchisees would both compare the expected (economic and social) benefits of acquiring new outlets to pre-defined standards and compare these potential benefits to what exchange alternatives would offer. One can reasonably assume that franchisees with high affective commitment to the relationship are convinced that the prospect of acquiring multiple outlets meets both performance criteria and that positive outcomes will ensue in terms of profit, career growth, and gaining a more central position in the franchise.

Future research should however clarify whether franchisees’ expansion into the acqui-sition of new units is primarily explainable by affective commitment to the franchisor vs. the outlets. The commitment literature has indeed evolved into considering multiple foci of exchange such as supervisors or work groups, which are more proximal and tangible than the abstract organization (Becker, 2009). Franchisees may feel that the exchange relationship primarily develops with their own outlets rather than with the more distal franchisor. Another avenue would be to explore whether franchisees’ entrepreneurial orientation would moderate their willingness to expand. Franchisees may act as entrepre-neurs when they recognize and seize opportunities and take risks. Therefore, franchisees who are entrepreneurs may want to develop multiple units (Ketchen, Short, & Combs, 2011). Hence, the relationship between affective commitment and the acquisition of multiple units may be moderated by the entrepreneurial orientation of the franchisee.

Third, we found that franchisees with high affective commitment were less likely to engage in opportunistic behaviors. This makes sense from a SET perspective. Indeed, franchisee commitment emerges through the creation of relational norms that both govern future exchanges among the parties and represent agreed upon mechanisms aimed at controlling future behavior (Lambe et al., 2001). SET suggests that affective commitment to the relationship is the result of parties’ willingness to maintain a balance among their respective social and economic inputs such that they would experience mutual depen-dence on the relationship. This interdependepen-dence feeds the expectation that there will be an equitable split of social and economic outcomes over time (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). Therefore, the incentive for free-riding and opportunistic behavior may be minimal in this case. This may explain why franchisee affective commitment was negatively related to opportunism. However, it would be worth formally testing whether franchisees’ affective commitment suffers when the franchisor is perceived to be contributing less to the relationship than the franchisee, which would open the door to opportunism.

Fourth, this research examined thecontingenciesimpacting the relationship between franchisees’ affective commitment and intent to leave. We actually found that continuance commitment acted as a boundary condition, and that affective commitment had a stronger and negative impact on exit intention when continuance commitment was low. In other words, as stated by SET, franchisee retention is explained by both the social (affective commitment) andeconomic(continuance commitment) outcomes of the exchange. This finding is particularly important as research suggests that franchisees are more likely to leave their system when the associated start-up cost is relatively low (Frazer & Winzar, 2005). Franchises with low start-up costs would thus be well advised to build affective commitment among their franchisees. However, even if continuance commitment alone seems to be sufficient to retain franchisees, our research suggests that affective commit-ment has positive effects besides retention.

responsibility for a particular target” (Klein, Molloy, & Brinsfield, 2012, p. 137). This framework conceives commitment as emerging from the perception of a set of antecedents including individual characteristics (e.g., personality), target characteristics (e.g., close-ness), interpersonal factors (e.g., social exchange), and organizational (e.g., HR practices) and societal (e.g., culture) factors. As our study focused on the interpersonal factors (social exchange), future research should examine how the other factors influence com-mitment in franchising.

Practical Implications

This research also offers practical implications for franchise organizations. Our find-ings suggest that franchisors may benefit from developing affective commitment among their franchisees. Although developing commitment is particularly challenging as fran-chisees’ affective commitment tends to be weaker than the commitment of managers of company-owned units (Castrogiovanni & Kidwell, 2010), recent research provides some preliminary recommendations in this area. Franchisors may build franchisee’s affective commitment by communicating with them on a frequent, formal, rational, and reciprocal basis (Meek et al., 2011). They may also select franchisees on the basis of personality traits (Weaven et al., 2009), as extraverted, agreeable, and emotionally stable franchisees tend to be more affectively committed to the franchisor (Morrison, 1997). Finally, fran-chisors could also pay attention to other drivers of affective commitment that have been examined in nonfranchising contexts such as met expectations and support from peers or mentors.

Other aspects of our findings have practical implications. For example, age and tenure were negatively related to the intention to acquire new outlets in Study 2. This suggests that those franchisees who want to expand are generally younger and less tenured. Consequently, franchisors should work at identifying those factors that reduce older and more tenured franchisees’ expansion strategy. Similarly, those franchisees that already had multiple outlets were more likely to entertain an expansion strategy (see Table 4). There may thus be a behavioral commitment operating here, whereby initial expansion builds confidence in the ability to develop one’s business further. Findings regarding self-reported performance are also interesting. Self-reported performance was negatively related to opportunism (see Table 5) and intent to leave (see Table 7), and positively related to the intention to acquire additional units (see Table 4). As self-rated performance is potentially influenced by self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura, 1993), this would suggest that franchisors should attempt to foster these beliefs among franchisees, for example by demonstrating trust and support on a regular basis.

Limitations

The present set of studies has limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of Studies 2, 3, and 4 precludes any inference of causality. Study 1 allows for a more causal interpretation of findings (i.e., commitment predicts change in performance from 2008 to 2009) but also reveals that affective commitment and franchisee performance may be reciprocally related across time (see correlations reported in Table 1). Longitudinal research is thus needed to further examine the directionality of the relationship between affective commitment and franchisee performance. Second, except for Study 1, all vari-ables were collected at the same time from a single source, raising the possibility of common method variance effects. However, this concern may be alleviated by several

features of our studies. First, Study 3 partialed out the effects of trait affectivity, which is a source of method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Second, the interaction effect reported in Study 4 is unlikely to be artifactual as common method variance actually reduces the power of detecting interaction effects (Evans, 1985). Finally, our test of common method variance bias in our three self-report studies showed that it was limited.

Third, response rates in Studies 2, 3, and 4 were generally low (34.47%, 17.6%, and 13.90%, respectively). Although our analyses of attrition bias revealed no systematic bias in responses, further replication of our findings is warranted. Fourth, while Study 1 found significant relationships between affective commitment and performance criteria, the effect sizes were modest (DR2=4 and 3%; see Table 2). One explanation for this lies in the type of performance considered. Franchisee commitment may be more strongly related to discretionary performance (e.g., making innovative suggestions to improve the quality of the franchise organization) than to objective performance (such as the produc-tivity or sales revenue measures used in this research) (Riketta, 2002). Alternatively, franchisees’ affective commitment may be more related to performance when there is a climate for competitiveness (Lam, 2012) or service (Schneider et al., 2005) in the fran-chise organization. Future research should address these issues.

Finally, except for Study 4, this research did not consider potential moderators of commitment’s effects. For example, the relationship between franchisee commitment and opportunism may be weaker when the franchisor exerts a tight control over franchisees (Mellewigt, Ehrmann, & Decker, 2011). Also, the relationship between affective commit-ment and intent to own additional units may be weaker when the franchisee experiences a low sense of competence in managing multiple outlets. Considering such potential moderators and others would advance our understanding of the influence of commitment on franchisee behavior.

Despite these limitations, this research offers some meaningful contributions to our understanding of affective commitment in franchising. This area of research is still in its infancy, and many interesting questions remain to be addressed. We hope that the preliminary findings reported in this paper in regard to the role of affective commit-ment, and more broadly SET, as a driver of franchise outcomes, will encourage researchers to further investigate the influence of social exchange relationships in the context of franchising.

Appendix

Survey Items

Affective commitment

This franchise organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me. I really feel a sense of belonging to my franchise organization.

I am proud to belong to this franchise organization. I feel emotionally attached to my franchise organization.

I really feel as if my franchise organization’s problems are my own. I feel like “part of the family” at my franchise organization.

Continuance commitment—perceived switching costs

I have invested too much time in this franchise organization to consider working elsewhere.

For me personally, the costs of leaving this franchise organization would be far greater than the benefits.

I would not leave this franchise organization because of what I would stand to lose. If I decided to leave this franchise organization, too much of my life would be disrupted. I continue to work for this franchise organization because I don’t believe another franchise organization could offer the benefits I have here.

Opportunism

I sometimes alter facts slightly in order to gain the cooperation of my franchisor. I sometimes explicitly promise to do things requested by my franchisor without actually doing them later.

I sometimes withhold information that would help my franchisor to run his business. I do not always share information in a timely manner with my franchisor.

I sometimes make vague promises to my franchisor that I later ignore.

I sometimes purposely withhold information that would put me in a bad light. I sometimes tell my franchisor what I think he wants to hear instead of telling him the truth.

Intent to acquire additional units

I intend to own one or several additional units of this franchise organization in the next two years.

Within the next six months, I intend to acquire an additional unit of this franchise organization.

I don’t plan to own additional units of this franchise organization (reverse scored). Intent to leave

How likely is it that you will voluntarily leave your franchise organization when your current franchise agreement expires?

How likely is that you will renew your franchise agreement at the end of term? Affectivity (control variable)

Thinking about yourself and how you normally feel, to what extent do you generally feel:

Upset Hostile Alert Ashamed Inspired Nervous Determined Attentive Afraid Active

Self-reported performance—Study 1 and Study 3 (control variable)

As compared to other similar franchisees in this franchise organization, our perfor-mance is very high in terms of:

Sales growth Profit growth Overall profitability

Self-reported performance—Study 4 (control variable)

Compared to other franchisees in this chain, my outlet(s) is/are performing well. To date, I have been able to meet the business objectives for my outlets.

Based on the franchisor’s forecasts, the performance of my outlet(s) is (1) poor, (2) below expectations, (3) average, (4) above expectations, (5) outstanding.

Franchisor strategy for multi-unit franchising (control variable) We encourage our franchisees to own more than one unit

We are reluctant to allow a franchisee to manage several units (reverse scored) We limit the number of units a franchisee can open (reverse scored)

Multiple-unit franchising is a part of our strategy

REFERENCES

Aguinis, H. & Gottfredson, R.K. (2010). Best-practice recommendations for estimating interaction effects using moderated multiple regression.Journal of Organizational Behavior,31(6), 776–786.

Arnold, T.J., Palmatier, R.W., Grewal, D., & Sharma, A. (2009). Understanding retail managers’ role in the sales of products and services.Journal of Retailing,85(2), 129–144.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning.Educational Psycholo-gist,28(2), 117–148.

Becker, T.E. (2009). Interpersonal commitments. In H.J. Klein, T.E. Becker, & J.P. Meyer (Eds.),Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions(pp. 137–178). New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

Bentein, K., Vandenberg, R., Vandenberghe, C., & Stinglhamber, F. (2005). The role of change in the relationship between commitment and turnover: A latent growth modeling approach. Journal of Applied Psychology,90(3), 468–482.

Blau, P. (1964).Exchange and power in social life. New York: John Wiley.

Brislin, R.W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. Triandis & J.W. Berry (Eds.),Handbook of cross-cultural psychology(Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Castrogiovanni, G.J. & Kidwell, R.E. (2010). Human resource management practices affecting unit managers in franchise networks.Human Resource Management,49(2), 225–239.

Combs, J.G., Ketchen, D.J., Shook, C.L., & Short, J.C. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of franchising: Past accomplishments and future challenges.Journal of Management,37(1), 99–126.

Combs, J.G., Ketchen, D.J., & Short, J.C. (2011). Franchising research: Major milestones, new directions, and its future within entrepreneurship.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,35(3), 413–425.

Cox, J. & Mason, C. (2007). Standardisation versus adaptation: Geographical pressures to deviate from franchise formats.Service Industries Journal,27(8), 1053–1072.

Cropanzano, R. & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review.Journal of Management,31(6), 874–900.

Dalal, R.S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior.Journal of Applied Psychology,90(6), 1241–1255.

Dant, R.P., Weaven, S.K., Baker, B.L., & Jeon, H.J. (2013). An introspective examination of single-unit versus multi-unit franchisees.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,41(4), 473–496.

Darr, E.D., Argote, L., & Epple, D. (1995). The acquisition, transfer, and depreciation of knowledge in service organizations: Productivity in franchises.Management Science,41(11), 1750–1762.