Correlation between Sparring and Cognitive Function in Boxers of Two

Boxing Camps in Medan

Alfansuri Kadri, Aldy S. Rambe, dan Hasan Sjahrir Departemen Penyakit Syaraf

Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Sumatera Utara/RS H. Adam Malik, Medan

ental Questionnaire (SPMQ), and Clock Drawing Test (CDT). Data regarding their sparring exposure were also collected.

Results: The mean ± SD of MMSE score of the participants was 27 ± 1.95 (95% CI), while for SPMQ and CDT was 9.86 ± 0.35 (95% CI) and 3.92 ± 0.28 (95% CI). Correlations between the boxers’ performance on the neuropsychological tests and their age and boxing record were non significant (p>0.05). However, various indices of increased sparring exposure were inversely correlated with MMSE (p<0.05) and SPMQ score (p<0.05), but not with CDT score (p>0.05). More frequent sparring was correlated with decreased test performance on portions of the Orientation (p<0.05) and Total score (p<0.05) of the MMSE.

Conclusion: Sparring, which involves repetitive blows to the head, may be correlated with statistically significant reductions in cognitive performance.

Keywords: sparring, cognitive function, MMSE, SPMQ, CDT

Abstrak: Banyak studi Neuropsikologis yang menyatakan bahwa tinju dapat mengakibatkan gangguan pada fungsi kognitif, khususnya memori, atensi dan pengolahan informasi. Resiko gangguan kognitif sehubungan dengan tinju – dementia pugilistica – telah dikenal selama bertahun-tahun. Resiko ini memerlukan perhatian dari para dokter, karena tinju merupakan olah raga yang populer dengan ribuan peserta.

Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui apakah nilai beberapa tes neuropsikologis yang dipilih berhubungan dengan dimensi paparan latih tanding tinju yang dipilih, terlepas dari norma- norma populasi umum.

Studi potong lintang dilakukan pada bulan Maret – April 2005 pada 36 petinju dari dua sasana tinju di kota Medan. Seluruh peserta diminta untuk menyelesaikan 3 buah tes neuropsikologis: MMSE, SPMQ dan CDT. Data tentang seputar paparan latih tanding juga dikumpulkan.

Rata-rata ± SD dari nilai MMSE pada peserta adalah 27 ± 1,95 (95% CI), sementara untuk SPMQ dan CD adalah 9,86 ± 0,35 (95% CI) dan 3,92 ± 0,28 (95% CI). Hubungan antara performa petinju dengan hasil tes neuropsikologis serta dengan umur dan rekor bertinjunya adalah tidak bermakna (p>0,05). Namun berbagai indeks dari paparan latih tanding berhubungan terbalik dengan nilai MMSE (p<0,05) dan SPMQ (p<0,05), tetapi tidak dengan nilai CDT (p > 0,05). Latih tanding yang lebih sering, berhubungan dengan penurunan performa pada porsi orientasi (p < 0,05) dan nilai total MMSE (p < 0,05).

Sebagai kesimpulan, latih tanding yang melibatkan pukulan yang berulang-ulang pada kepala, dapat berhubungan dengan penurunan performa kognitif yang bermakna secara statistik.

INTRODUCTION

A ubiquitous feature of participation in organized or recreational athletics is the inherent risk of injury. Although most participants never consider the possibility of head injury, brain trauma remains a major cause of both severe and mild disability after athletic injury. The concern of the neurosurgical community with neurologic problems confronting those who participate in recreational and competitive athletics can be

describe as underwhelming.1-2

Athletic head injury encompasses a spectrum from mild head injury, characterized by transient alteration in consciousness, to severe injuries causing major morbidity and mortality. Cognitive impairments are a core feature of traumatic brain injury and can impair all manner of daily activities, depending on the patterns of

impairment.1-6

No sport has garnered more adverse publicity because of its neurological sequelae than boxing. The debate over the risk of long-term neurological and neuropsychological deficits among ex-boxers and the concern generated by recent catastrophic injury in the ring have focused the attention of the medical community and the public on the risk of

boxing.1

Given the relationship between neurological dysfunction and professional boxing, there has been interest in analysing the relationship between amateur boxing and traumatic brain injury. Most neuropsychological studies of boxers suggest that boxing may lead to impairment in memory, attention, and information processing. The risk of cognitive impairment associated with boxing—dementia

pugilistica—has been noted for many years.7-11

Neuropsychological testing represents the most sensitive technique to detect neurologic dysfunction associated with boxing. Despite the sensitivity of such testing, interpretation of the results poses some difficulties. Test score norms for the general population are not representative of the boxing population and therefore are of limited value or should be

used with caution.8

This study, therefore, was designed to determine if selected neuropsychological tests

scores correlate with selected dimensions of boxing exposure, without reference to the general population norms.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were boxers recruited from 2 boxing camps in Medan (Rajawali Boxing Camp and FKPPI Boxing Camp). Subjects were included if they were male boxers, graduated from junior high school (had 9 years of educational level), and agreed to sign the informed consent. Boxers with history of head injury other than from boxing activity within the past 6 months, mute, and unable to communicate in Indonesian language were excluded. A total of 36 boxers were eligible for this study.

All boxers who participated in the investigation underwent neuropsychological testing and were interviewed the day of the testing regarding neurologic symptoms and boxing history

Boxing exposure

Boxing history was obtained via a questionnaire administered by the examiner at the time of the interview. Exposure variables, all self reported, included boxing record, duration of boxing career. Sparring exposures was assessed and defined as follows:

1. Frequency: sessions per week

2. Rounds: rounds per session

3. Total rounds: the estimated average

number of rounds sparred per week. This was obtained by multiplying the average number of sparring sessions per week by the average number of rounds per session.

4. Intensity: the estimated average intensity

of the sparring, which is the average number punches that a boxer took in one round, graded as follow: grade 1: no contact, grade 2: 1-10 punches per round, grade 3: 11-20 punches per round, grade 4: > 20 punches per round.

5. Exposure index: the total number of

rounds per week, multiplied by the intensity.

6. Cumulative exposure index: the sparring

Neuropsychological Testing

Each boxer underwent a battery of neuropsychological tests consisted of Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) test, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMQ), and Clock Drawing Test (CDT).

• Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)

By far the most common measure used for briefly assessing mental status is the MMSE, developed in the mid-1970s. The MMSE has been extensively used in both the clinical and epidemiologic literature. The MMSE is comprised of items assessing six principal domains of mentation: orientation, registration, attention, calculation, short-term memory, and language. The final score is trichotomized, with high score (24-30) suggesting no cognitive impairment; scores in an intermediate range (17-23) suggesting probable cognitive impairment; and low scores (0-16) indicating definite cognitive impairment. The median score in high school education ages 18-69 is 28-29. 2, 12, 13

• Short Portable Mental Status

Questionnaire (SPMQ)

Other traditional cognitive screening instruments include the Mental Status Questionnaire (MSQ) and its revision, the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMQ). The SPMQ is a 10-item psychometric tool designed to be a revision of the MSQ and to be more difficult, assessing orientation to personal information (age, date of birth, mother’s maiden name), time (date), place (location), recent events (president, previous president), and serial subtraction. All items carry the same weight and performance is judged by number of errors committed, the range extending from 0 to 10. The final score is divided into 4 categories, 0-2 errors indicating intact intellectual function; 3-4 errors suggesting mild cognitive impairment; 5-7 errors suggesting moderate cognitive impairment; and 8 – 10 errors indicating

severe cognitive impairment.2, 14

• Clock Drawing Test (CDT)

The drawing of clocks is a common procedure in neurobehavioral examination and has been adopted by some examiners as a quick screening test for dementia and other neurologic disorders. Briefly, an

individual is required to draw the face of a clock on command, putting all the numbers in the correct order, and placing the hands at a requested time typically “10 after 10” or “20 after 3”. Because the test requires conceptualisation and abstraction, planning, organization, visuospatial judgement, and motor abilities, it constitutes a broad screen for diverse cognitive problems.2, 12,15,16

Data Analysis

Since accepted norms for neuropsychological data cannot be applied to the boxing population, the boxers’ test score were not classified according to available normative data. Instead, correlations between the boxers’ test performance and their age, boxing record, and exposure variables were examined. Measures of correlations were calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

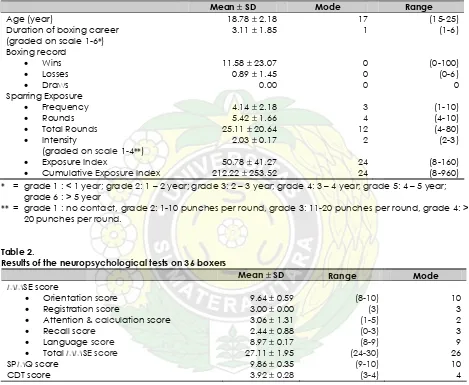

The characteristics of the 36 boxers are shown in table 1. The average age was 18.78 years (range, 15 to 25 years) and most of the boxers had duration of boxing career of < 1 year (grade 1). Member of the group apparently were fairly successful in amateur boxing, as evidenced by the relatively high win-loss ratio. Sparring practices appeared to be quite variable; boxers sparred anywhere from 1 to 10 times per week (mean, 4.14 times).

Correlations between the boxers’ performance on the neuropsychological tests and their age, duration of boxing career, and boxing record were non significant (P>0.05). However, various indices of increased sparring

exposure were inversely associated with test scores (table 3). These results mostly reflected dysfunction in the areas of orientation and Total score of the MMSE.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 36 boxers tested for cognitive function

Mean ± SD Mode Range

Age (year) 18.78 ± 2.18 17 (15-25)

Duration of boxing career (graded on scale 1-6*)

3.11 ± 1.85 1 (1-6)

(graded on scale 1-4**) • Exposure Index

• Cumulative Exposure Index

4.14 ± 2.18 20 punches per round.

Table 2.

Results of the neuropsychological tests on 36 boxers

Mean ± SD Range Mode MMSE score

• Orientation score • Registration score

• Attention & calculation score • Recall score

• Language score • Total MMSE score

Correlations of neuropsychological test results with indices of sparring exposure among 36 boxers Sparring • Attention &

calculation

More frequent sparring was correlated with decreased performance on portions of Orientation, Recall, and the Total Score of the MMSE (p<0.05). The number of rounds per session (mean, 5.42; range 4 to 10) was inversely correlated to performance on the SPMQ (p<0.05). The total sparring rounds per week averaged 25.11 (range, 4 to 80). Greater number of rounds per week correlated with poorer performance on the Total MMSE Score (p<0.05). Sparring intensity ranged from grade 2 to 3. Higher sparring intensity correlated with diminished performance on the Orientation score of the MMSE (p<0.05). The sparring exposure index was not inversely correlated with any of neuropsychological test (p>0.05) and the cumulative sparring index correlated inversely with Orientation, Recall, and Total Score of the MMSE, and also the SPMQ score.

DISCUSSION

The neurobehavioral effects of closed head injury due to athletic events include alterations in cognition, mood, and social functioning that reduce the quality of life for both the patient and significant others. Chronic traumatic brain injury is considered by some authorities to be the most serious health problem in modern day boxing. The condition is often referred to by a number of names in the medical and non-medical literature, including dementia pugilistica and

“punch drunk” syndrome.11

Memory loss and dementia have been a frequent finding in ex-fighters. The pathological correlation of this impairment may stem in part from mesial temporal neurofibrillary tangle formation, disruption of the fornix by caval septum formation, atrophy and gliosis of the mamillary bodies, or

generalized cerebral atrophy.1

Study by Jordan and colleagues also suggests that possession of

an APOE ε 4 allele may be associated with

increased severity of chronic neurologic

deficits in high-exposure boxers.17

Neuropsychological examination in active amateur fighters has been performed to assess for early brain damage. In McLatchie and colleagues’ investigation of 20 active amateurs, 15 had abnormal neuropsychological profile; deficiencies of memory and attention were

found most commonly.1

Matser and colleagues

examined the Acute Traumatic Brain Injury

(ATBI) in 38 amateur boxers.8

They found that boxers who competed exhibited an ATBI pattern of impaired performance in planning, attention, and memory capacity.

The correlation between increased sparring exposure and declining performance on the neuropsychological tests was not unexpected. It is widely known among the boxing community that most of a boxer’s traumatic exposures occur during sparring. Sparring here is defined as making the motions of attack and defense with the fist and arms.18,19

This observation is supported by the findings of a survey of boxing injuries among cadets at the US Military Academy at

West Point, New York.20

During a 2-year period, the majority of injuries occurred during instructional boxing rather than competition, even though the injury rate was higher during competition. The greater number of injuries occurring during instruction may reflect greater exposure time during instruction and/or sparring. In an analysis of 42 professional boxers in New York city, Jordan et al also found that sparring is associated in poorer performance on

neuropsychological tests.9

The present study found that correlations between the boxers’ performance on the neuropsychological tests and their age, duration of boxing career, and boxing record were non significant (P>0.05). However, various indices of increased sparring exposure were inversely associated with test scores, especially in the areas of Orientation and Total score of the MMSE (p<0.05). Thus, the results of this cross-sectional study suggest that sparring is correlated with poorer performance on neuropsychological tests, which matches the previous studies. These significant correlations between cognitive function and sparring exposure are highly compatible with well-documented sequelae of closed cerebral trauma.

determine the neuropathological changes in the brain of the boxers that may be associated with the neuropsychological tests results.

As a conclusion, sparring, which involves repetitive blows to the head, may be correlated with statistically significant reductions in cognitive performance. This correlation, and the lack of relationship between competition and declining cognitive function, may be explained by the fact that boxers spend far more time sparring than actually competing. Thus, measures to prevent brain injury should include supervision of sparring bouts and reassessment by boxers of the amount and intensity of sparring they do.

REFERENCES

1. Evans RW. Neurology and Trauma.

Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1996.

2. Rizzo M, Eslinger PJ. Principles and

Practice of Behavioural Neurology and Neuropsychology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2004.

3. Matser EJT, Kessel AG, Lezak MD, et al.

Neuropsychological Impairment in Amateur Soccer Player. Journal of American Medical Association 1999; 282: 971 – 75.

4. Collins MW, Grindel SH, Lovell MR.

Relationship between concussion and neuropsychological performance in college football player. Journal of American Medical Association 1999; 282: 964 -70.

5. Teasdole TW, Engberg AW. Cognitive

disfunction in young men following head injury in childhood and adolescence: a population study. Journal of Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74: 933 – 36.

6. Goldstein FC, Levin HS, Goldman WP.

Cognitive and Behavioural Sequele of Closed Head Injury in Older Adults According to Their Significant Others. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 1999; 11: 38-44.

7. Moriarty J, Collie A, Olson, et al. A

prospective controlled study of cognitive function during an amateur boxing tournament. Journal of Neurology 2004; 62: 1497 – 1502.

8. Matser EJT, Kessels AG, et al. Acute

Traumatic Brain Injury in Amateur Boxing; The Physician and Sportsmedicine Journal 2000; 28: 87.

9. Jordan, Barry D. Sparring and Cognitive

Function in Professional Boxers Sportsmedicine Journal 1996; 24: 87-92.

10.Slemmer JE, Matser EJT, De Zeeuw CI.

Repeated mild injury causes cumulative damage to hippocampal cells. Guarantors of Brain Journal 2002; 125: 2699 - 2709

11.McCrory P. Boxing and the Brain. British

Journal of Sports Medicine 2002; 36: 2.

12.Asosiasi Alzheimer Indonesia (AazI),

Pengenalan dan Penatalaksaan Demensia Alzheimer dan Demensia Lainnya. Jakarta. 2003

13.Mini-Mental State Exam. Available from:

www.fpnotebook.com/NEU71.htm

14.Short Portable Mental Status

Questionnaire. Available from: www.medicine.uiowa.eduigectoolsassetsS

hortPortableMentalStatusQ.pdf.

15.Clock Drawing Test. Available from:

www.fpnotebook.com/NEU74.htm

16.Shah J. Only Time Will Tell: Clock

Drawing as an Early Indicator of Neurological Dysfunction. Spring 2001. 30 – 34.

17.Jordan BD, Relkin NR, Ravdin LD, et al.

Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 associated with Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury in Boxing. Journal of American Medical Association 1997; 278: 136 – 40.

18.Definition of spar. Available from:

www.wordreference.com

19.Sparring-definiton. Available from:

www.hyperdictionary.com

20.Welch MJ, Sitler M, Kroeten H: Boxing