AN ANALYSIS ON THE TRANSLATION OF

SHIRAISHI’S YOUNG HEROES: THE INDONESIAN FAMILY IN POLITICS INTO PAHLAWAN-PAHLAWAN BELIA: KELUARGA

INDONESIA DALAM POLITIK BASED ON TRANSLATION EQUIVALENCE THEORIES

A Thesis Presented to

The Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Magister Humaniora (M. Hum) in

English Language Studies

by

YOHANA VENIRANDA 01.6332.007

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

PAGE OF TITLE ………..………..… i

PAGE OF APPROVAL ………...………..…. ii

PAGE OF DEFENCE APPROVAL PAGE ………. iii

STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ……….…. iv

LIST OF TABLES ………..………... v

LIST OF FIGURES ……….………..…. vi

ABSTRACT ………...…. vii

ABSTRAK ….……….….… ix

PREFACE ………...… xi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ………...….. xiii

CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ……….. 1

A. Background of Study……….…… 1

B. Problem Formulation ………..….. 7

C. Objectives of Study ……… 7

D. Problem Limitation ……….….…. 8

E. Benefits of the Study ……….…… 8

CHAPTER II. THEORETICAL REVIEW ………. 10

A. Definitions of Terms ……….…. 10

1. Translation ………..… 10

2. Source Text (ST) ...………. 12

4. Source Language (SL) ………...… 13

5. Target Language (TL) ………..…. 13

B. Theories on Translation……….…... 13

1. The Processes of Translation ……….…... 14

2. General Principles of Translation ………..… 21

3. Approaches to Translation ……….……… 23

a. The Functional Approach ……….….…… 24

b. The Variational Approach ……….……… 25

4. Approaches to Teaching Translation ……….……….27

a. The Process-Oriented Approach ……….……...… 27

b. The Product-Oriented Approach ……….……... 31

5. Equivalence ………..…….. 31

a. Equivalence at Word Level ……….……... 32

b. Equivalence above Word Level ….……….……... 36

c. Grammatical, Textual, and Pragmatic Equivalence .……….….… 39

6. Untranslatability ……….….... 46

7. Using Translation as a Resource for the Promotion of Language Learning ……….……… 48

C. Theories on English to Indonesian Translation ….……… 50

1. Simple and Complex Noun Phrases ……….……….… 51

2. Conjunctions and Conjuncts ……….……… 51

3. Relative Pronouns ……….……… 53

4. Tense and Aspect ……….………. 54

6. Prepositions ……….………….………….. 57

7. Pronouns ……….………….…………... 60

8. Singular and Plural ……….……… 61

9. Problems in English to Indonesian Translation: Grammatical and Socio-Political-Cultural Aspects ……….……….…….. 63

CHAPTER III. METHODOLOGY ………. 69

A. Research Data ……….………. 69.

B. Research Procedures ………. ……….… 70.

C. Data Analysis ………….……….……….…. 70

CHAPTER IV. DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ………..… 74

A. Data ………...… 74

B. Analysis …..………...… 97

C. Discussion …..………... 130

CHAPTER V. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS ……….…… 140

A. Conclusions …..….………..… 140

B. Suggestions ……....……….. 144

BIBLIOGRAPHY ……… 147

ABSTRACT

YOHANA VENIRANDA. (2003). AN ANALYSIS ON THE TRANSLATION OF SHIRAISHI’S YOUNG HEROES: THE INDONESIAN FAMILY

IN POLITICS INTO PAHLAWAN-PAHLAWAN BELIA: KELUARGA INDONESIA DALAM POLITIK BASED ON TRANSLATION EQUIVALENCE THEORIES. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies, Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University.

This thesis has aimed at exploring the theories on translation as an overview in general and the theories on English to Indonesian in particular, and presenting the results of a case study on a translation product. There are three questions in this study. The first is what the psychological nature of translation processes is. The second is what the theoretical nature of English to Indonesian translation is. And the third is how the results of the analysis on the phrases and sentences in the translation of Shiraishi’s Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics into Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia: Keluarga Indonesia dalam Politik are. The answers to questions number one and number two have been derived from the study on the theories on translation. The answer to the third question has been the result of the analysis on the data, that consist of phrases and sentences, of the translation of Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics into Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia: Keluarga Indonesia dalam Politik.

From several models of translation processes, it can be concluded that the process of translation is the process of information processing. The psychological nature of translation process is the transfer of meaning. The translator needs to discover the meaning of the ST and re-express the meaning in the TL. The process involves syntactic, semantic and pragmatic analyzers, which continues with syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic synthesizers. It is possible for some stages to be passed through very quickly, for example in the Frequent Structure Store and Frequent Lexis Store. The norm for the process is a combination of bottom-up and top-down.

The nature of English to Indonesian translation can be concluded as follows:

1. English and Indonesian have some differences in grammatical aspects, among others are the use tenses and aspects, verb agreement/ concord with the Subject, use of pronouns, relative pronouns, singular and plural markers of noun phrases, use of articles, positions of conjuncts, and meanings of conjunctions 2. Some problems in socio-political-cultural aspects include some daily

expressions, idioms, fixed expressions, and use of measurements.

3. Understanding the nature of the differences between the SL and the TL, a translator will be able to anticipate problems that may arise from the differences.

1. Meaning or message has been the main focus rather than the forms. The translator is not too much tied up with the literal words and phrases. For a better understanding, many reformulations of the sentences have been done. 2. Easy reading has been tempted by cutting very long sentences into shorter and

precise ones. The translator has taken into account the consideration that the TT is a popular reading.

3. Most of the translation losses have been for some purposes such as to avoid lengthy repetition, to make the sentence more precise, to avoid unexpected misinterpretation of some phrases. The translation losses have been mostly for understandable reasons and there are no significant meaning biases that have changed or destroyed the main message of the ST.

4. Machali’s description of good translation can be used to describe the result of the analysis of the data in this study: There is basically no distortion of meaning. There are some inappropriate literal translations, grammatical and idiomatic mistakes but less than 15% of the whole text, and there are one or two uses of non-standard terms and one or two spelling errors.” (Machali, 2000:120)

At the end of the discussion on the theories on translation, it is worthwhile to remind translators that in translation, translators have some missions to accomplish. Benjamin (1968:76) mentions that the task of the translator consists in finding that intended effect (intention) upon the language into which he is translating which produces in it the echo of the original. Siegel (1986:7) emphasizes the responsibility of a translator because translation can sustain a culture as well as stifle it. Sontag (2002:340-341) mentions three variants of the modern idea of translation, i.e. translation as explanation, translation as adaptation, and translation as improvement.

ABSTRAK

YOHANA VENIRANDA. (2003). AN ANALYSIS ON THE TRANSLATION OF SHIRAISHI’S YOUNG HEROES: THE INDONESIAN FAMILY

IN POLITICS INTO PAHLAWAN-PAHLAWAN BELIA: KELUARGA INDONESIA DALAM POLITIK BASED ON TRANSLATION EQUIVALENCE THEORIES. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies. Graduate Program. Sanata Dharma University.

Tesis ini bertujuan mendalami teori terjemahan sebagai tinjauan umum, dan teori terjemahan dari bahasa Inggris ke bahasa Indonesia khususnya, dan melaporkan hasil studi kasus suatu hasil terjemahan. Ada tiga pertanyaan dalam penelitian ini. Pertanyaan pertama tentang hakekat psikologis dari proses terjemahan. Yang kedua tentang hakekat teori terjemahan dari bahasa Inggris ke bahasa Indonesia. Dan yang ketiga, hasil analisa dari frasa dan kalimat dalam terjemahan karya Shiraishi Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics menjadi Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia: Keluarga Indonesia dalam Politik.

Jawaban untuk pertanyaan pertama dan kedua diperoleh dari kajian pustaka tentang teori-teori terjemahan. Jawaban untuk pertanyaan ketiga diperoleh dari hasil analisa data, yang terdiri dari frasa-frasa dan kalimat-kalimat, dari terjemahan Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics menjadi Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia: Keluarga Indonesia dalam Politik.

Dari beberapa model proses terjemahan, dapatlah disimpulkan bahwa proses terjemahan adalah proses pengolahan informasi. Hakekat psikologis dari terjemahan adalah transfer makna. Penerjemah menemukan makna dari naskah sumber dan menyampaikan makna tersebut dalam bahasa yang dituju. Proses itu mencakup analisa sintaksis, semantik, dan pragmatik, yang kemudian dilanjutkan dengan sintesa sintaksis, semantik, dan pragmatik. Beberapa tahap dilalui dengan cepat, seperti di Frequent Structure Store and Frequent Lexis Store. Proses ini merupakan kombinasi proses dari bawah ke atas dan dari atas ke bawah.

Hakekat teoritis terjemahan dari bahasa Inggris ke bahasa Indonesia dapat disimpulkan sebagai berikut:

1. Bahasa Inggris dan bahasa Indonesia memiliki perbedaan dari segi tata bahasa, antara lain penggunaan tenses dan aspek, perubahan kata kerja yang disesuaikan dengan Subyek, penggunaan kata ganti, kata ganti penghubung, penunjuk kata benda tunggal/jamak, penggunaan artikel, posisi kata penghubung kalimat, dan arti kata sambung.

2. Beberapa masalah aspek social, politik, dan budaya mencakup ungkapan sehari-hari, kata kiasan, peribahasa, dan istilah untuk penunjuk ukuran.

3. Dengan memahami hakekat perbedaan antara bahasa sumber dan bahasa yang dituju, seorang penerjemah dapat mengantisipasi masalah yang mungkin muncul dari perbedaan itu.

1. Makna lebih menjadi pokok perhatian dari pada bentuk. Penerjemah tidak terlalu terikat pada kata dan frasa secara harafiah. Untuk memberikan pemahaman yang lebih baik penataan ulang kalimat telah dilakukan.

2. Untuk menghasilkan karya yang nyaman dibaca, kalimat-kalimat yang terlalu panjang telah dipenggal menjadi lebih pendek. Penerjemah mempertimbangan bahwa naskah terjemahan ditujukan untuk bacaan popular. 3. Sebagian besar dari bagian yang hilang dalam terjemahan memiliki tujuan

tertentu seperti untuk menghindari pengulangan yang terlalu banyak, untuk menghasilkan kalimat yang lebih ringkas, dan untuk menghindari penafsiran yang keliru dari beberapa bagian frasa. Terjemahan yang hilang lebih dikarenakan alasan-alasan yang dapat diterima dan tidak ada penyimpangan makna yang signifikan yang mengubah atau merusak makna inti dari naskah sumber.

4. Penjelasan Machali tentang terjemahan yang baik dapat digunakan untuk menjelaskan hasil analisa data dalam penelitian ini: Tidak ada distorsi makna; Ada terjemahan harafiah yang kaku, kesalahan tata bahasa dan idiom tetapi relatif tidak lebih dari 15% dari keseluruhan teks. Ada satu-dua penggunaan istilah yang tidak baku/umum dan satu atau dua kesalahan tata ejaan.” (dari Machali, 2000:120)

Pada akhir pembahasan tentang teori terjemahan, perlulah mengingatkan penerjemah bahwa dalam menerjemahkan, penerjemah memiliki misi yang perlu dicapai. Benjamin (1968:76) menyebutkan tugas dari penerjemah mencakup penyampaikan makna yang dimaksudkan dengan bahasa yang dituju, yang dapat menghasilkan gaung dari bahasa sumber. Siegel (1986:7) menekankan tanggung jawab penerjemah karena penerjemahan dapat mempertahankan dan juga meniadakan suatu budaya. Sontag (2002:340-341) menyebutkan tiga pemikiran baru tentang terjemahan, yaitu terjemahan sebagai penjelasan, sebagai adaptasi, dan sebagai perbaikan.

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

A. Background of Study

Some cases of onomatopoeia, i.e. the use of words, which have been formed like the noise of the thing that they are describing or representing, can be interesting to start the discussion of translation. When English people write down the sound of the cocks in the morning as cock-a-doodle-doo, the sound is ku-ku-ru-yuk in Indonesian, and it becomes tik-ti-la-ok in the Philippines. The sound of a gun, for example, in English is usually written down as bang-bang but in Indonesian, it is dor-dor. To imitate the knock on the door in English, people use “knock-knock” and in Indonesian it is “tok-tok-tok”.

Cases of idiomatic expressions can be funny jokes. Translating It’s raining cats and dogs into Indonesian will not mention the two kinds of animals. It is Hujan lebat sekali. Translating This book costs me a fortune, a student has confidently related it to a familiar word fortune teller and the result was Saya membutuhkan seorang peramal untuk memberitahu saya harga buku ini instead of Buku ini sangat mahal. A Further question is why puppy love is cinta monyet.

And still about animals, let the sleeping dogs lie is Jangan membangunkan macan tidur.

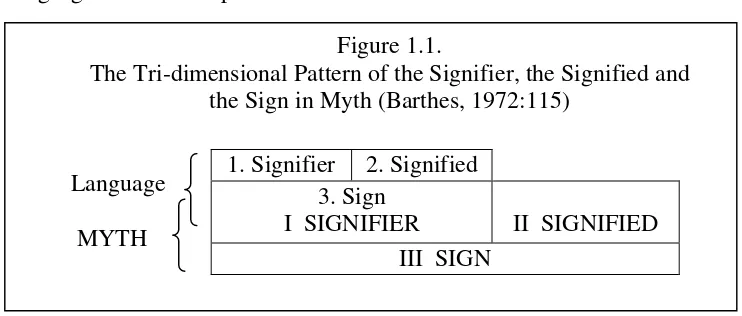

The examples above can be discussed from the view Saussure proposes, i.e. about the sign, the signified and the signifier. In a language, the signified is the

concrete entity (Saussure in Barthes, 1972:113). Starting from the fact that in human language the choice of sounds is not imposed on us by the meaning itself, Saussure had spoken of an arbitrary relation between signifier and signified. The ox does not determine the sound ox, since in any case the sound is different in

other languages (Barthes, 1981:50). A further problem for translators to recognize is the second set of sign, signifier and signified, which form a myth. The following figure shows the pattern:

Figure 1.1.

The Tri-dimensional Pattern of the Signifier, the Signified and the Sign in Myth (Barthes, 1972:115)

1. Signifier 2. Signified 3. Sign

I SIGNIFIER II SIGNIFIED III SIGN

Language

MYTH

Barthes (1972:115) calls the first set ‘language-object’ and the second set ‘metalanguage’. When talking about the signs, translators cannot avoid considering the signified and the signifier of the source language and the target language, especially in the level of myth. The same sign between the source language and the target language will not always refer to the same signifier or signified.

translation on the words in the dictionary, they are “safe”, meaning they cannot be wrong.

Translation can be a complex process that involves many aspects to consider before we come to a final version of a translation product. Some teachers consider translation as a separate skill. It implies that translation requires practice rather than theories. To some extent, translation is a skill because the more one practices to translate, the better he can do it. However, some students have complained that they cannot improve themselves well by merely keeping on translating without understanding any theories on translation.

Some teachers treat translation as a scientific orientation to linguistic structures, semantic analysis, and information theory. According to Nida and Taber (1974:vii), translation is far more than a science. It is also a skill, and in the ultimate analysis, fully satisfactory translation is always an art. The translation of the Bible into some 800 languages, representing about 80 percent of the world’s population involved at least 3,000 persons. According to Nida and Taber (1974:1), in the translation of the Bible, the underlying theory of translation has not caught up with the development of skills. Despite consecrated talent and painstaking efforts, a comprehension of the basic principles of translation and communication in the bible translation has lagged behind the translation in secular fields. Translators of religious materials have sometimes not been prompted by the feeling of urgency to make sense (Nida and Taber, 1974:1).

have got it or you have not. Translation is similar to subjects like mathematics or physics. Some people are good at it, others find it difficult (Hervey and Higgins, 1992: 13).

Hervey and Higgins (1992:13) argue that when we talk of proficiency in translation, we are no longer thinking merely of the basis of natural talent an individual may have, but of the skill and facility that require learning, technique, practice and experience. The answer to anyone who is skeptical about the formal teaching of translation is twofold: students with a gift for translation invariably find it useful in building their native talent into a fully-developed translating proficiency; students without a gift for translation invariably acquire some degree of proficiency.

Newmark (1981:38) quotes Savory’s words from The Art of Translation (1968:54):

A translation must give the words of the original. A translation must give the ideas of the original. A translation should read like an original work. A translation should read like a translation.

A translation should reflect the style of the original. A translation should possess the style of the translation. A translation should read as a contemporary of the original. A translation should read as a contemporary of the translation. A translation may add to or omit from the original.

A translation may never add to or omit from the original. A translation of verse should be in prose.

A translation of verse should be in verse.

Belitt (1983:481) describes translation from different groups of people’s point of view:

“Indeed, Babel is always with us. The moralist will say, for example: Translation is a long discipline of self-denial, a matter of fidelity or betrayal. The vitalist will say: Translation is a matter of life and death, merely: the life of the original or the death of it. The poet will say: Translation is either the composition of a new poem in the language of the translator, or the systematic liquidation of a master-piece from the language of the original. The epistemologist will say: “Translation is an illusion of the original forced upon the translator at every turn because he has begun by substituting his own language and occasion for that of the poet’s and must fabricate his reality as he goes. The sybil sees all and says: Translation is the truth of the original in the only language capable of rendering it “in truth”: the original language untouched by translation.” (Belitt: 1983:481)

The quotation above adds the list of the various descriptions and definitions of translation with a sense of confusion in it.

A translation class has not been an easy class to handle. The problem lies on the difficulties to judge a translation of a certain text when we are given a list of alternatives. We can only say this one is possible and that one is also possible. Then a decision on which is better between two alternatives or which is the best among several alternatives is made. Sometimes it takes a long time to decide which version of translation is better or the best. The decision is usually not a single absolute choice and it is sometimes still debatable. Going through such a process of decision-making can sometimes be tiring, but students need to understand that the process can also be part of learning.

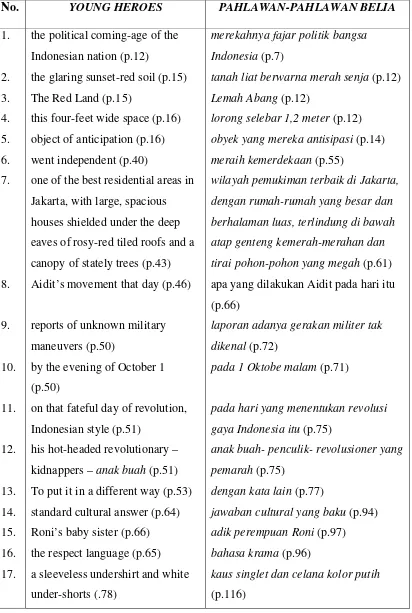

Politik, which is translated from Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics, as a case study, for the analysis. Henceforth, in most part of this thesis, the source text is referred to as Young Heroes and the target text is Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia. The source text has been chosen on the ground that it is a

research report, an academic work. As a form of scientific writing, the language is a formal language. It uses good and standard English. Choosing a novel or another kind of literary work will require another kind of analysis and it will involve more cultural implications, rhymes, beauty, style, and some personal mode.

The writer of Young Heroes, Shiraishi, is a Japanese, who pursued her further studies at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. This book is derived from her dissertation for her doctorate degree. From the point of the content, it is an interesting book because it depicts a lot of Indonesian family values. The values are projected and reflected into the political life of the nation. One part of the book also discusses children in the classroom. This book is worth reading for teachers and anyone involved in educational field.

Another reason is that it has been translated into Indonesian by Tim Jakarta Jakarta, with Seno Gumira Ajidarma, who is an artist and a novelist, as

the coordinator. With the English and the Indonesian versions at hand, the analysis can be done. We may see and learn something from Tim Jakarta Jakarta, because they are professionals in using Indonesian for popular purposes.

is mostly non-Indonesians, although they are ‘Indonesianists’, who have involved a lot in Indonesian studies. The audience of the target text (TT), as a popular book, is Indonesians, especially the educated, middle-class Indonesians. This difference may result in some consequences in the translation product. It can be interesting to find out the consequences of such different audiences for the ST and TT. Even Shiraishi herself said that she was anxious to wait and see how this book would be read by Indonesians. In her opinion, Indonesian people like to introduce themselves as the Javanese, the Sundanese, etc. Shiraishi wants to convince to readers that the concept of “Indonesian people” does exist. She is curious how the translators will maintain the nuance of her English text into Indonesian. In many examples of cases in her book, Indonesian is a language which often maintains a weird emptiness, a void at its core (Shiraishi, 1997:121).

B. Problem Formulation

This study tries to answer the following questions: 1. What is the psychological nature of translation processes?

2. What is the theoretical nature of English to Indonesian translation?

3. How are the results of the analysis on the phrases and sentences in the translation of Shiraishi’s Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics into Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia: Keluarga Indonesia dalam Politik?

C. Objectives of Study

results of a case study on a translation product. By using Shiraishi’s Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia: Keluarga Indonesia dalam Politik, which has been translated from Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics, this study tries to present an example of an English to Indonesian translation product. The analysis to present the strengths and weaknesses of the translation product is done based on the theories on translation.

D. Problem Limitation

Some theories on translation are applicable to translation in general. It means that they can be used as the general principles to translate a text of any languages into any other languages. This study focuses on English to Indonesian translation. Some general theories on translation are included on the considerations that they are useful to provide some basic principles of translation and some general approaches to translation. The discussion on the general theories on translation is followed by the discussion on the theories English to Indonesian translation. In this part, more examples of English to Indonesian translation are given. It is impossible to include all the theories on translation in this study. The theories presented are chosen on the consideration that they are applicable to translation in general and relevant to the analysis of English to Indonesian translation.

E. Benefits of the Study

translation. The theories on English to Indonesian translation can provide us with some general principles of translating English to Indonesian texts. The theories include some discussion on the difference between the two languages in lexical, syntactic, as well as socio-political-cultural aspects.

The results of the analysis on the translation product will provide us with some insights about the problems, techniques and considerations in English to Indonesian translation. Shiraishi’s Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics is an interesting book. There are a lot of similar books on Indonesian, which are still written in English. The translation of such books will be useful for more Indonesian people to reflect on themselves. The analysis on the book in this study can be as a sample for other translators who are interested in translating similar books.

CHAPTER II

THEORETICAL REVIEW

A. Definitions of Terms 1. Translation

According to Webster (1994), translation is an act, process, or instance of translating as a) a rendering from one language into another, and also the product of such a rendering, b) a change to a different substance, form, or appearance (conversion). Webster describes the verb to translate as 1) to turn into one’s own or another language, 2) to transfer or turn from one set of symbols into another (transcribe), 3) to express in different terms and especially different words (paraphrase), 4) to express in more comprehensible terms (explain, interpret). Nida and Taber (1974:12) define translation as the reproduction in a receptor language of the closest natural equivalent of the source message, first in terms of meaning, and secondly in terms of style. Cobuild (1995:1781) defines translation as a piece of writing or speech that has been translated from a different language. Hornby (1974:919) defines translation as giving the meaning of something said or written into another language. However, Hornby differentiates a translator from an interpreter. He defines a translator as a person who translates, especially something written, and an interpreter for something spoken. Other authors have other different opinions.

insofar as translation is supposed to preserve the meaning of the original utterance, and it is unlike interpretation, which aims at going beyond the meaning of the utterance.

Though some writers differentiate translation from interpretation, many writers use the two terms interchangeably. According to Quine and Davidson (in Martinich, 1996:442), the fact that understanding, interpretation, and translation are conventionally used in different circumstances is not relevant to the fact that the cognitive activity is the same in each case. In other words, according to them, the difference between the terms is a matter of usage, not meaning.

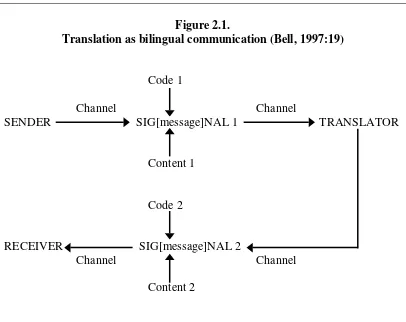

Bell (1997:19) discusses translation as bilingual communication. He describes the communication process in the following figure.

Figure 2.1.

Translation as bilingual communication (Bell, 1997:19)

Code 1

Channel Channel

SENDER SIG[message]NAL 1 TRANSLATOR

Content 1

Code 2

RECEIVER SIG[message]NAL 2 Channel Channel

Bell describes the figure as follows: translator receives signal 1 containing message, recognizes code 1, decodes signal 1, retrieves message, comprehends message, translator selects code 2, encodes message by means of code 2, selects channel, transmits signal 2 containing message.

Bell (1997:13) also tries to define three distinguishable meanings for the word translation.

a. Translating: the process (to translate; the activity rather than the tangible object);

b. A translation: the product of the process of translating (i.e. the translated text); c. Translation: the abstract concept, which encompasses both the process of

translating and the product of that process.

In this study, translation is defined as bilingual communication that involves the reproduction in a target language or receptor language of the closest natural equivalent of the source message, both in meaning and style.

2. Source Text (ST)

A source text or ST is the text that requires translation (Hervey and Higgins, 1992: 15). The source text is sometimes referred to as the original version of a text. In this study, the source text (ST) is the English text of Shiraishi’s Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics.

3. Target Text (TT)

4. Source Language (SL)

A source language or SL is the language in which the text requiring translation is couched (Hervey and Higgins, 1992: 14). In this study, Shiraishi’s Young Heroes, which is the source text (ST), uses English. Therefore, English is

the source language (SL). 5. Target Language (TL)

A target language or TL is the language into which the original text is to be translated (Hervey and Higgins, 1992:15). Some other writers such as Larson (1984), Nida and Taber (1974) also use the term a receptor language to refer to TL. In this study, Pahlawan-Pahlawan Belia, which is the target text (TT), uses Indonesian. Indonesian is the target language (TL).

B. Theories on Translation

“The purpose of translation theory is to reach an understanding of the process undertaken in the act of translation and not to provide a set of norms for affecting the perfect translation” (Bassnett-Mcguire in Bell, 1997:22). De Beaugrande (in Bell, 1997:23) gives a warning that it is inappropriate to expect a theoretical model of translation to solve all the problems a translator encounters. Instead, it should formulate a set of strategies for approaching problems and for coordinating the different aspects entailed. In other words, translation theory is reoriented towards description, whether of process or product, and away from prescription.

The first is a theory of translation as process (i.e. a theory of translating). This would require a study of information processing and within that, such topics as perception, memory, the encoding and decoding of messages, and would draw heavily on psychology and on psycholinguistics.

The second is a theory of translation as product (i.e. a theory of translated texts). This would require a study of texts not merely by means of the transitional levels of linguistics (syntax and semantics) but also making use of stylistics and recent advances in text-linguistics and discourse analysis.

The third is a theory of translation as both process and product (i.e. a theory of translating and translation). This would require the integrated study of both and such a general theory is, presumably, the long- term goal for translation studies (Bell, 1997:26).

1. The Process of Translation

According to Hervey and Higgins (1992:15), a translation process can, in crude terms, be broken down into two types of activity, i.e. understanding an ST and formulating a TT. According to Nida and Taber (1974:208), translation, which aims at dynamic equivalence comprises three stages, namely analysis, transfer, and restructuring. Larson (1984:3) states that translation consists of studying the lexicon, grammatical structure, communication situation and cultural context:

Larson’s description of the process of translation is shown in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2.

The Process of Translation (Larson, 1984:4)

SOURCE LANGUAGE RECEPTOR LANGUAGE

Text to be Translation

Translated

Discovering Re-express

the meaning the meaning

MEANING

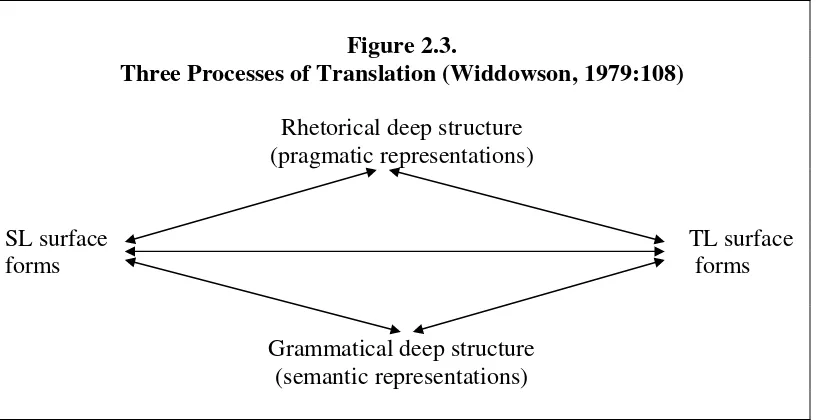

Widdowson (1979:108) thinks of translation in terms of three alternative processes, which is shown in the following figure.

Figure 2.3.

Three Processes of Translation (Widdowson, 1979:108) Rhetorical deep structure

(pragmatic representations)

SL surface TL surface

forms forms

Grammatical deep structure (semantic representations)

through pragmatic representations, one teaches communicative acts and shows how they may be realized in formally diverse ways in the SL and TL.

Bathgate (in Widyamartaya, 1989:40-41) describes the translation process into seven steps, namely tuning, analysis, understanding, terminology, restructuring, checking, and discussion. Tuning means trying to get the feel of the text to be translated. Each ‘register’ as it is usually called, demands a different mental approach, a different choice of words or turn of phrase. In the analysis, after the translator attunes his mind to the framework of the text to be translated, he will take each sentence in turn and split it up into translatable units - words and phrases. The syntactic relations between the various elements of the sentence are also established.

In the next step, i.e. understanding, after having split up the sentence into its elements, the translator will generally put it together again in a form which he can understand. Due attention to both form and content is essential. In the next step called terminology, the translator considers the key words and phrases in the sentence to make sure they are in line with standardized usage and is neither misleading, ridiculous, nor offensive for the target-language reader.

In restructuring, when all the bricks needed for the edifice of the target language text have been gathered or made, the translator will fit them together in a form which is in accordance with good usage in the TL. This is the phase where ‘form’, as opposed to ‘content’, comes into its own.

more correct, translation. In addition, someone other than the translator can read through the finished translation and make or suggest changes.

The last step is discussion. A good way to end the translation process is a discussion between the translator and the expert on the subject matter. It is inadvisable to have more than two participants – out of this: too many cooks spoil the broth. On the other hand, it is sometimes necessary to point out to translators that they should not work in isolation.

It can be inferred from the process above that the translation process is not a one-punch work. In the restructuring and checking, the translator may need to go back to the beginning of the process again.

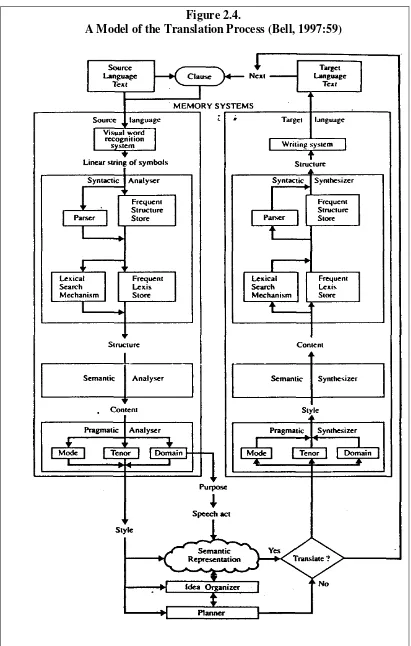

Bell (1997:44-45) describes the process of translation that includes the process in the memory system. The model can be seen in figure 2.4. He explains that there are several assumptions that underlie the model. The process of translating:

a. is a special case of the more general phenomenon of human information processing;

b. should be modeled in a way which reflects its position within the psychological domain of information processing;

c. takes place in both short-term and long-term memory through devices for decoding text in the SL and encoding text into the TL, via a non-language-specific semantic representation;

e. proceeds in both a bottom-up and a top-down manner in processing text and integrates both approaches by means of a style of operation which is both cascaded and interactive, i.e. analysis or synthesis at one stage need not be completed before the next stage is activated and revision is expected and permitted;

f. requires there to be, for both languages

1) a visual word-recognition system and a writing system

2) a syntactic processor which handles the options of the MOOD system and contains a

3) Frequent Lexis Stores (FLS), a Lexical Search Mechanism (LSM), a Frequent Structure Store (FSS), and a parser, through which information passes to (or from) a

4) semantic processor which handles the options available in the TRANSITIVITY system and exchanges information with a

5) pragmatic processor which handles the options available in the THEME system and there is also an

6) idea organizer which follows and organizes the progression of the speech acts in the text (and, if the text-type is not known, makes inferences on the basis of the information available) as part of the strategy for carrying out plans for attaining goals, devised and stored in the

Figure 2.4.

The figure contains several important terms. The first is Frequent Lexis Stores (FLS). This is the mental (psycholinguistic) correlate of the physical glossary or terminology database, i.e. an instant ‘look-up’ facility for lexical items both ‘words’ and ‘idioms’ (Crystal in Bell, 1997:47). The second is Frequent Structure Store (FSS). It is a set of operations that involves the exploitation of frequently occurring structures, which are stored in memory in their entirety as is a lexical item with direct access to phrases and sentences, nearly as rapid as it is for individual words (Steinberg in Bell, 1997:48).

The third is Lexical Search Mechanism (LSM). This has the task of probing and attempting to ‘make sense’ of any lexical item which cannot be matched with items already stored in the FLS. The fourth is Parser. Parser has the task of analyzing any clause for which analysis appears necessary. The following sample sentence can be used to describe parser:

The smaggly bognats grolled the fimbled ashlars for a vorit.

It is the sequence of phrases NP-VP-NP-PP. Bognats and ashlars are countable, possess the attributes of being smaggly and fimbled respectively. Bognats are able to groll ashlars either for a period of time (how long) or for some client (i.e. on behalf of a vorit). All this information is derived from the reader’s syntactic knowledge (Bell, 1997:49).

The last one is Domain of Discourse. The domain of discourse is the ‘field’ covered by the text; the role it is playing in the communication activity; what the clause is for, what the sender intended to convey; and its communicative value. Domain is connected with function. In a narrow sense, domain is connected with the use of language to persuade, to inform or some other speech acts. In a much broader sense, domain can refer to such macro-institutions of society as the family, friendship, education, and so forth (Bell, 1997:191).

Tenor, mode and domain of discourse are three stylistic parameters. In sociological variables, tenor refers to the participants, mode refers to the purposes, and domain refers to the settings (Bell, 1997:9)

2. General Principles of Translation

In 1540, Dolet published a short outline of translation principles, entitled La manière de bien traduire d’une langue en aultre (How to Translate Well from

One Language into Another) and established five principles for the translator (Bassnett, 1996:54):

a. the translator must fully understand the sense and meaning of the original author, although he is at liberty to clarify obscurities;

b. the translator should have a perfect knowledge of both SL and TL; c. the translator should avoid word-for-word renderings;

d. the translator should use forms of speech in common use;

Dolet’s principles stress the importance of understanding the SL text as primary requisite. According to Dolet, the translator is far more than a competent linguist, and translation involves both a scholarly and sensitive appraisal of the SL text and an awareness of the place the translation is intended to occupy in the TL system.

Nida and Taber (1974:173) try to answer the question “What is a good translation?” They try to answer it by contrasting a good translation with bad translations of two kinds:

Table 2.1.

A Good Translation Contrasted with Two Kinds of Bad Translations (Nida and Taber, 1974:173)

BAD GOOD BAD Formal correspondence:

the form (syntax and classes of words) is preserved; the meaning is lost or distorted

Dynamic equivalence: the form is restructured (different syntax and lexicon) to preserve the same meaning

Paraphrase by addition, deletion, or skewing of the message.

Further Nida and Taber explain that it is possible to produce a bad translation, as in column 1, by preserving the form at the expense of the context. On the other hand, it is possible to produce a bad translation as in column 3, by paraphrasing loosely and distorting the message to conform to alien cultural patterns. This is the bad sense of the word “paraphrase”. However, as in column 2, a good translation focuses on the meaning or context as such and aims to preserve that intact; and in the process it may quite radically restructure the form. This is paraphrase in the proper sense.

a. uses the normal language form of the receptor language

b. communicates, as much as possible, to the receptor language speakers the same meaning that was understood by the speakers of the source language, and c. maintains the dynamics of the original source language text.

Maintaining the “dynamics” of the original source text means that the translation is presented in such a way that it will, hopefully, evoke the same response as the source text attempted to evoke.

Hymes (in Bell, 1997:11) describes a good translation to be:

“That in which the merit of the original work is so completely transfused into another language, as to be as distinctly apprehended, and as strongly felt, by a native of the country to which that language belongs, as it is by those who speak the language of the original work.”

From this, Hymes says that three laws. The first is that the translation should give a complete transcript of the ideas of the original work. The second is that the style and manner of writing should be of the same character with that of the original. And the third is that the translation should have all the ease of original composition.

3. Approaches to Translation

a. The Functional Approach

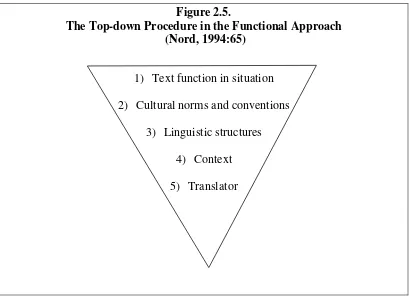

In the functional approach, the translation strategies should follow a ‘top-down’ procedure, as shown in figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5.

The Top-down Procedure in the Functional Approach (Nord, 1994:65)

1) Text function in situation 2) Cultural norms and conventions

3) Linguistic structures 4) Context 5) Translator

Nord (1994:66) describes the steps in the procedure as follows:

1) a particular translation problem is analyzed with regard to its function in the text and in the target situation;

2) the analysis leads to a decision whether the translation has to be adapted to target-culture norms and conventions or whether it should reproduce source-culture conventions used in the source text;

3) this decision sets limits to the range of linguistic means to be used;

5) if there is still a choice between various means, the translator may decide according to individual preferences.

b. The Variational Approach

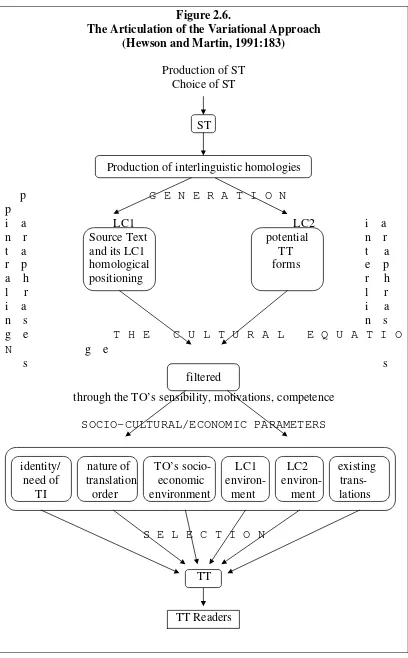

The approach is not a description of ‘what happens’ when one translate, but a proposition for a more dynamic approach to translating. As shown in figure 2.6, the two complementary procedures of generation and selection are productive, and can help the translator to break away from the somewhat mechanical notion of one-to-one equivalents, which some people tend to work with.

The separation between the two halves of the model appears rigid in the figure, but given the speed of operations carried out, it is likely that there may be a to-and-fro movement within the model, as options are generated, selected, and then submitted to a regeneration process as certain parameters start to take precedence (Hewson and Martin, 1991: 182).

Figure 2.6 that shows the articulation of the Variational Approach contains several abbreviations. They are LC, TO and TI. LC is Language Culture, and LC1, therefore, goes beyond what is called elsewhere the ‘Source Language’, as it necessarily brings in the indissociable pair of Language and Culture. The same applies to LC2, which replaces ‘Target Language.’

Figure 2.6.

The Articulation of the Variational Approach (Hewson and Martin, 1991:183)

Production of ST Choice of ST

ST

Production of interlinguistic homologies

p G E N E R A T I O N

p

i a LC1 LC2 i a

n r Source Text potential n r t a and its LC1 TT t a r p homological forms e p

a h positioning r h

l r l r

i a i a

n s n s

g e T H E C U L T U R A L E Q U A T I O N g e

s s

filtered

through the TO’s sensibility, motivations, competence SOCIO-CULTURAL/ECONOMIC PARAMETERS

identity/ nature of TO’s socio- LC1 LC2 existing need of translation economic environ- environ- trans-

TI order environment ment ment lations

S E L E C T I O N

TT

TI is Translation Initiator. The illustration of the fundamental role of the TI can be started from the premise that translation does not just ‘happen’. Translation results from 1) a need, and 2) an order. The need corresponds to a foreseen or actual breakdown in communication. The order corresponds to the instructions given by the TI to ensure that communication takes place. Once one has identified the TI as the driving force behind the translation operation, it becomes clear that his identity, his ‘position’ in socio-cultural and LC terms, is of prime importance. The translation will be fashioned to suit his order. That very order can be determining in itself if it is of a restricted or specific nature (Hewson and Martin, 1991:113).

4. Approaches to Teaching Translation

Different approaches to teaching translation result in different techniques of teaching translation, and in assessing translation products.

a. The Process-Oriented Approach

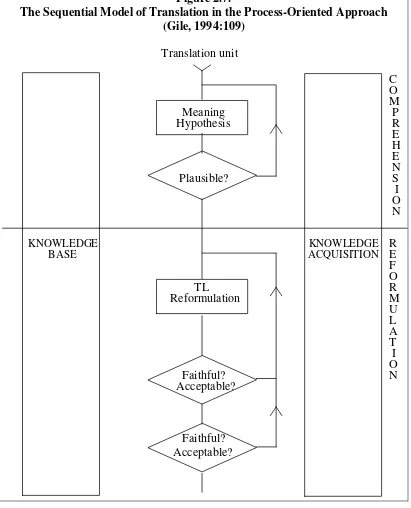

Gile (1994:108) sums up the basic philosophy of a process-oriented translation training system as follows:

1) during the process-oriented part of the course, trainees are considered as students of translation methods rather than as procedures of finished products; 2) teachers take a normative attitude as far as the process are concerned. They

3) processes are supported by theoretical models which explain and integrate them. The most important one is the sequential model of translation, which is discussed in the following part and shown in Figure 2.7;

4) problem diagnosis can be done partly by analyzing the product and partly by putting questions to the students as explained above. When handling in translation assignments, students are also required to report in writing the problem they encountered while doing the translation – difficulties in understanding a particular sentence, in reformulating an idea, in finding the meaning of a source language term, in finding a good target language equivalent, etc.

The sequential model of translation, as mentioned above as an important model in process-oriented translation consists of a ‘comprehension phase’ and a ‘reformulation phase’. Translation starts with a ‘translation unit’. It is read. Its meaning is inferred from the text as a meaning hypothesis. This hypothesis is then checked for plausibility on the basis of the translator’s existing linguistic and extra-linguistic knowledge. If the first meaning hypothesis is deemed plausible, the translator can move to the reformulation phase. If not, the translator must find another hypothesis and check its plausibility, etc.

In the reformulation phase, the translator formulates a first target language text for the translation unit. He then tests it for fidelity and for linguistic acceptability. If results are not satisfactory, he writes a new target language text for the same unit and tests it again, and so on.

good results at the text level. At every step of the process, existing linguistic and extra-linguistic knowledge must be used, and whenever necessary, additional knowledge must be sought.

When finding a problematic word or statement in a translation, the teacher asks the student whether this solution sounds logical, plausible, linguistically acceptable, and consistent with the rest of the text. The teacher can accept the answer on the grounds that the procedure was correct, even if the student’s solution is wrong by his standards. The teacher can make a mental (or written) note of recurrent problems, which will have to be dealt with in the product-oriented part of the course.

Psychologically, the process-oriented approach seems to generate less stress than the product-oriented approach. Problem- reporting is a strong component of the approach.

Figure 2.7.

The Sequential Model of Translation in the Process-Oriented Approach (Gile, 1994:109)

Translation unit

C

O

M

Meaning P Hypothesis R E H E N Plausible? S

I

O

N

KNOWLEDGE KNOWLEDGE R

BASE ACQUISITION E

F

O

TL R

Reformulation M U L A T I O Faithful? N Acceptable?

Faithful? Acceptable?

language are poor, in so far as it does not teach how to write. Similarly, it does not provide solutions for difficult cases. The approach is very useful in the first part of the course, but product-oriented teaching must follow (Gile, 1994:112).

b. The Product-Oriented Approach

Machali (2000:156-157) discusses the product-oriented approach in looking at translation as the step following the process-oriented approach. Otherwise, learners or translators may consider their work as already good because the process is already appropriate. The product-oriented approach is expected to lead to better-quality translation.

In teaching, according to Machali, the activities can involve changing a target text so that it is suitable for the target readers, and revising a text that involves re-ordering sentences. Some exercises on collecting terms, analyzing them, and standardizing them, and putting them in a database that can be retrieved when needed, can be done.

5. Equivalence

a. Equivalence at Word Level

A discussion on equivalence can be started with a discussion on non-equivalence. Larson (1984:89-97) discusses the non-equivalence or mismatching of lexical systems between languages. Even though the same things, events, and attributes may exist in the referential world, the systems of reference do not match one-to-one across languages. Languages arbitrarily divide the meaning differently. Larson uses examples of various languages to describe the difference in lexical systems:

English red Mbembe

orange okora

yellow

green ohina

blue black

house oikos numuno

The Greek word oikos is used in the sentence Peter went up to the housetop to pray. A translation into languages of Papua New Guinea may result in a very distorted understanding if simply translated with the word numuno. The

round thatched roof would be an inappropriate place to climb up on in order to pray (Larson,1984:96).

false literal translation, and “False friends”. Symbolic words acquire some symbolic value and carry figurative or metaphorical meaning as well as the basic meaning of the word, for example the word cross. It refers to the wooden cross used for crucifixion during the time of the Roman empire. Symbolically, it means death and suffering, it can also stands for Christianity. In the translation of Ephesians 2:16, the word cross is retained and addition has been made in order to carry the correct meaning:

ST: … might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross thereby bringing hostility to an end…

TT1: …by his death on the cross Christ destroyed the enmity; by means of the cross he united both races into one body and brought them back to God.

TT2: he died on the cross to put an end to the hatred and bring us back to God as one people.

There are problems with word combinations and false literal translation because some groups of words function in the same way as a single word. The meaning of the combination as a whole cannot always be determined by the meaning of the individual constituent parts. For example, a translation from the French word pomme de terre would be potato in English and not the literal apple of earth.

“False friends” can be defined as words in the source language, which look very much like words in the receptor language because they are cognate with them, but in fact mean very different. An example is the word affair in English and afair in Indonesian.

and the target languages make different distinctions in meaning, the target language lacks a super-ordinate, the target language lacks a specific term (hyponym), difference in physical or interpersonal perspective, differences in expressive meaning, differences in form, differences in frequency and purpose of using specific forms, and the use of loan words in the source text.

Besides listing the types of problems, Baker (1992: 26-42) also suggests several strategies to cope with the problems. The first is translation by a more general word (super-ordinate). Translator may need to go up a level in a given semantic field to find a more general word that covers the core propositional meaning of the missing hyponym in the target language. For example, the verb shampoo when translated into Spanish, the back translation is wash. Another example, translating the word to orbit into Spanish, the back translation is to revolve (Baker, 1992:27).

The second is translation by a more neutral/less expressive word. For example, translating an English word mumbles into Italian:

Someone mumbles, “Our competitors do it.”

Qualcuno suggerisce: “i nostri concorrenti lo fanno.”

Back translation: Someone suggests: Our competitors do it.”

The Italian near equivalent mugugnare tends to suggest dissatisfaction rather than embarrassment or confusion (Morgan Matroc in Baker, 1992:29).

The third is translation by cultural substitution. For example, translating the word porca in Italian into bitch in English represents a

straightforward cultural substitution in the following quotation.

…and began to stamp his feet, bellowing bitch, bitch, bitch… until she gave up, which was not very soon.

Porca is literally the female of swine (piglet), when applied to a woman,

indicates unchastity and harlotry (Trevelyan in Baker, 1992:33)

The fourth is translation using a loan word or loan word plus explanation. This strategy is common in dealing with culture-specific, modern, and buzz words. Following the loan words with an explanation is very useful when the word in question is repeated several times in the text. Once explained, the loan words can then be used on its own.

The fifth is translation by paraphrase using a related word. For example, translating the word creamy into Arabic, the back translation is that resembles cream. Another example, translating terraced gardens into French, the

back translation is gardens created in a terrace.

The sixth is translation by paraphrase using unrelated words. For example, translating a Lonrho affidavit into Arabic, the back translation is a written communication supported by an oath presented by the Lonrho organization. Another example, translating the word accessible into Chinese, the

back translation is where human beings enter most easily.

The eighth is translation by illustration. For example, there is no easy way of translating tagged, as in tagged teabags, into Arabic without going into lengthy explanations which would clutter the text. An illustration of a tagged teabag is used instead of a paraphrase (Baker, 1992:42).

b. Equivalence above Word Level

The discussion on equivalence above word level includes the discussion on first, collocation, and second, idioms and fixed expressions. Collocation refers to the tendency of certain words to co-occur regularly in a given language. For example, cheque is more like to occur with bank, pay, money, write than with moon, butter, playground or repair. Strong tea is literally dense tea in Japanese. Break the law is an unacceptable collocation in Arabic, the more common is contradict the law (Baker, 1992:47-54).

Marked collocation or unusual combination of words is sometimes used in the source text in order to create new images. Ideally, the translation of a marked collocation will be similarly marked in the target language.

In translating idioms and fixed expressions, there are some main difficulties:

1) an idiom or fixed expression may have no equivalent in the target language; 2) an idiom or fixed expression may have a similar counterpart in the target

language, but its context of use may be different;

language idiom both in form and meaning, the play on idiom cannot be successfully reproduced in the target text;

4) the very convention of using idioms in written discourse, the context in which they can be used, and their frequency of use may be different in the source and target languages.

Idiom demands that the translator be not only accurate, but also highly sensitive to the rhetorical nuances of the language. Some strategies to translate idioms are proposed by Baker (1992:72-78). The first is using an idiom of similar meaning and form. The second is using an idiom of similar meaning but dissimilar form. The third is translation by paraphrase, and the fourth is translation by omission

Larson (1984:111-117) discusses this kind of equivalence in figurative senses of lexical items. Besides idioms, some types of uses of figurative senses of lexical items that require careful treatment are metonymy, synecdoche, euphemism, and hyperbole.

Metonymy is the use of words in a figurative sense involving association, for example, The kettle is boiling (water), He has a good head (brain), The response from the floor was positive (people). In the first example, what is

boiling is not the kettle but the water in the kettle. The kettle is used to refer to the water in the kettle. In the second example, the head is used to refer to the brain. In the third example, the floor refers to the people.

the examples, the words the souls, the hearts, and the face are used to refer to the persons as a whole.

Euphemism is the use of one word for another or one expression for another to avoid offensive expression or one that is socially unacceptable or unpleasant (Beekman and Callow, 1974 in Larson, 1884:116). All languages have euphemistic expressions, especially in the areas of sex, death, and the supernatural. To say die, English uses pass away. Hebrew used gone to the fathers. In Mangga Buang of Papua New Guinea, your daughter’s eyes are

closed is preferable to your daughter is dead. In the US old people are now called senior citizens. In Chontal, the devil is called older brother. In Finnish, he is sitting in his hotel means he is in prison. The important thing is for the

translator to recognize the euphemistic nature of the source language expression and then translate with an appropriate and acceptable expression of the receptor language whether euphemistic or direct. The Greek Expression he is sleeping with his fathers might be translated he went to his village in Twi. Some others might simply say he died.

A hyperbole is a metonymy or synecdoche with more said than the writer intended the reader to understand. The exaggeration is deliberately used for effect, and is not to be understood as if it were a literal description. For example, they turned the world upside down; I am frozen to death; I am starving; He’s mad. Such deliberate exaggerations in the source language text may be

The goal of translation is not to eliminate all secondary and figurative senses. It is to use only secondary and figurative senses, which are peculiar to the receptor language and eliminate any strange collocations or wrong meaning caused by literal translation of source language secondary and figurative senses (Larson, 1984:114).

c. Grammatical, Textual, and Pragmatic Equivalence

There is no doubt that translators work with words and phrases as their raw material. Equivalence, however, cannot be truly established at this level alone. At the decision-making stage, the appropriateness of particular items can only be judged in the light of the item’s place within the overall plan of the text (Hatim and Mason, 1990: 180). With this thought in mind, translators also need to always consider equivalence above word level.

1) Grammatical Equivalence

It is difficult to find a notional category, which is regularly and uniformly expressed in all languages. Some major categories in the following discussion, namely number, gender, person, tense and aspect and voice, can illustrate the kinds of difficulty that translators often encounter because of differences in the grammatical structures of source and target languages (Baker, 1992: 82-110).

with no category of number has two main options: one, omit the relevant information on number, and two, encode this information lexically.

The second category is gender. French distinguishes between masculine and feminine gender in nouns such as fils/fille (son/daughter) and chat/chatte (male cat/ female cat). In addition, nouns such as magazine and construction are also classified as masculine and feminine respectively. An Arabic speaker or writer has to selct between ‘you, masculine’ (anta) and ‘you, feminine (anti) in the case of the second singular. This type of information must be signaled in the form of the verb itself. The use of passive voice instead of imperative form of the verb allows the translator to avoid specifying the subject of the verb altogether (Baker, 1992:90-94).

The third category is person. A large number of modern European languages, not including English, have a formality/ politeness dimension in their person system. For example, French vous as opposed to tu. Some languages also have different forms of plural pronouns which are used to express different levels of familiarity or deference in interaction with several addressees (Baker, 1992:94-98).

The fifth is voice. Languages which have a category of voice do not always use the passive with the same frequency. Nida (in Baker, 1992:106) explains that in some Nilotic languages the passive forms of verbs are so preferred that instead of saying ‘he went to town’, it is much more normal to employ an expression such as ‘the town was gone to by him’.

Baker (1992: 167-172) suggests some strategies for minimizing linear dislocation, i.e. by voice change, change of verb, nominalization, and extra-position. Extra-position involves changing the position of the entire clause in the sentence by, for instance, embedding a simple clause in a complex sentence. Cleft and pseudo-cleft structures provide good examples.

To sum up, a translator cannot always follow the thematic organization of the original. A translator should make an effort to present the target text from a perspective similar to that of the source text. Certain features of syntactic structure such as restrictions on word order, the principle of end-weight, and the natural phraseology of the target language often mean that the thematic organization of the source text has to be abandoned. What matters is that the target text has some thematic organization of its own, that it reads naturally and smoothly, does not distort the information structure of the original, and that it preserves, where possible, any special emphasis signaled by marked structures in the original and maintains a coherent point of view as a text in its own right (Baker, 1992:172).

2) Textual Equivalence

in English, namely reference, substitution, ellipsis, conjunction, and lexical cohesion.

Reference is a device, which allows the reader/hearer to trace participants, entities, events, etc. in a text. Hebrew, unlike English, prefers to use proper names to trace participants through a discourse. In some languages such as Japanese and Chinese, pronouns are hardly ever used and a participant is introduced. Continuity of reference is signaled by omitting the subjects of following clauses. Different preferences exist across languages for certain general patterns of reference.

In substitution, an item (or items) is replaced by another item (or items). For example, My axe is too blunt. I must get a sharper one. (One replaces axe). Ellipsis involves the omission of an item. In other words, an item is replaced by nothing. For example, Joan brought some carnations, and Catherine some sweet peas. (Ellipted item: brought on the second clause). In Arabic, all verbs agree with their subjects in gender and number, which means that links between the two are clear even when they are separated by a number of embedded clauses with their own subjects and verbs. Every language has its own devices for establishing cohesive links. Language and text-type preferences must both be taken into consideration in the process of translation (Baker, 1992:189-190).

languages, such as German, tend to express relation through subordination and complex structures. Chinese and Japanese prefer to use simpler and shorter structures and to mark the relations between these structures explicitly where necessary. Arabic prefers to group information into very large grammatical chunks (Baker, 1992:190-192).

Lexical cohesion refers to the role played by the selection of vocabulary in organizing relation within a text. A given lexical item cannot be said to have a cohesive function per se, but any lexical item can enter into a cohesive relation with other items in a text. An example comes from an advertisement of a woman’s magazine which shows a woman wearing a large hat, accompanied by the following caption: ‘If you think Woman’s Realm is old hat… think again’ (Cosmopolitan, October, 1999). Old hat means ‘boringly familiar/uninteresting’, but the literal meaning of hat is used here to create a lexical/visual chain by tying in with the actual hat in the photograph. This type of chain often has to be sacrificed in translation because interweaving idiom-controlled chains can only be reproduced if the target language has an idiom which is identical to the source idiom in both form and meaning.

The translator must always avoid is the extreme case of producing what appears to be a random collection of items which do not add up to recognizable lexical chains that make sense in a given text (Baker, 1992:207).

3) Pragmatic Equivalence

Two useful topics are coherence and implicature (Baker, 1992: 218). To discuss coherence, implicature and translation strategies, Baker underlines the importance of some considerations on some of the following aspects. The first is the conventional meanings of words and structures and the identity of reference. Knowledge of the language system may not be sufficient but it is essential if one is to understand what is going on in any kind of verbal communication. The ability to identify references to participants and entities is essential for drawing inferences and for maintaining coherence of a text.

The third is the context, linguistic or otherwise, of the utterance. Apart from the actual setting and the participants involved in an exchange, the context also includes co-text and the linguistic conventions of a community in general. The fourth consideration is on the items of background knowledge: text-presented information can only make sense if it can be related to other information we already know. A text may confirm, contradict, modify, or extend what we know about the world, as long as it relates to it in some way. It is important to note that in translation, as in any act of communication, a text does not necessarily have to conform to the expectations of its readership. Readers’ versions of reality, their expectations, and their preferences can be challenged without affecting the coherence of a text, provided the challenge is motivated and the reader is prepared for it.

The last consideration is on the availability of all relevant items falling under the previous headings. In order to convey an intended meaning, the speaker/writer must be able to assume that the hearer/reader has access to all the necessary background information, features of context, etc., that is items listed above, and that it is well within his/her competence to work out any intended implicatures. In attempting to fill gaps in their readers’ knowledge and fulfill their expectations of what is normal or acceptable, translators should not ‘overdo’ things by explaining too much and leaving the reader with nothing to do.

stylistic characteristics including purpose, and takes into account the three stylistic parameters, i.e. the tenor, the mode, and the domain of discourse.

6. Untranslatability

Catford (1974:98-99) distinguishes two types of untranslatability, i.e. linguistic and cultural untranslatability. Linguistic untranslatability is due to differences in the SL and the TL, whereas cultural untranslatability is due to the absence in TL culture of a relevant situational feature for the SL.

One of the difficulties mentioned above in the difficulties at word level is the cultural-specific concept. Most cultural-specific concepts are untranslatable. Shiraishi keeps the word bapak-anak relationship in her book because the literal translation father-child cannot match the concept.

Many tr