PRACTICAL GUIDES FOR LIBRARIANS

About the Series

This innovative series written and edited for librarians by librarians provides authoritative, practical information and guidance on a wide spectrum of library processes and operations. Books in the series are focused, describing practical solutions to problems facing today’s librarian and delivering step-by-step guides for planning, creating, implementing, managing, and evaluating a wide range of services and programs.

The books are aimed at beginning and intermediate librarians that need basic instruction and guidance in specific subjects and also at experienced librarians who need to gain knowledge in a new area or guidance in implementing a new program or service.

About the Series Editors

The Practical Guides for Librarians series was conceived and edited by M. Sandra Wood, MLS, MBA, AHIP, FMLA, Librarian Emerita, Penn State University Libraries from 2014 to 2017. Ms. Wood was a librarian at the George T. Harrell Library, the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, College of Medicine, Pennsylvania State University, in Hershey, PA, for over thirty-five years, specializing in reference, educational, and database services. Ms. Wood received an MLS from Indiana University and an MBA from the University of Maryland. She is a fellow of the Medical Library Association and served as a member of the MLA’s Board of Directors from 1991 to 1995.

Ellyssa Kroski assumed editorial responsibilities for the series beginning in 2017. She is the director of Information Technology at the New York Law Institute and an award-winning editor and author of thirty-six books, including Law Librarianship in the Digital Age for which she won the American Association of Law Libraries 2014 Joseph L. Andrews Legal Literature Award. Her ten-book technology series, The Tech Set, won the American Library Association’s Best Book in Library Literature Award in 2011. Ms. Kroski is a librarian, an adjunct faculty member at Drexel and San Jose State University, and an international conference speaker. She has recently been named the winner of the 2017 Library Hi Tech Award from the ALA/LITA for her long-term contributions in the area of library and information science technology and its application.

Titles in the Series edited by M. Sandra Wood

by Julia K. Nims, Paula Storm, and Robert Stevens

3. Managing Digital Audiovisual Resources: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Matthew C. Mariner

4. Outsourcing Technology: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Robin Hastings

5. Making the Library Accessible for All: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Jane Vincent

6. Discovering and Using Historical Geographic Resources on the Web: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Eva H. Dodsworth and L. W. Laliberté 7. Digitization and Digital Archiving: A Practical Guide for Librarians by

Elizabeth R. Leggett

8. Makerspaces: A Practical Guide for Librarians by John J. Burke

9. Implementing Web-Scale Discovery Services: A Practical Guide for Librarians by JoLinda Thompson

10. Using iPhones and iPads: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Matthew Connolly and Tony Cosgrave

11. Usability Testing: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Rebecca Blakiston 12. Mobile Devices: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Ben Rawlins

13. Going Beyond Loaning Books to Loaning Technologies: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Janelle Sander, Lori S. Mestre, and Eric Kurt

14. Children’s Services Today: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Jeanette Larson

15. Genealogy: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Katherine Pennavaria 16. Collection Evaluation in Academic Libraries: A Practical Guide for

Librarians by Karen C. Kohn

17. Creating Online Tutorials: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Hannah Gascho Rempel and Maribeth Slebodnik

18. Using Google Earth in Libraries: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Eva Dodsworth and Andrew Nicholson

19. Integrating the Web into Everyday Library Services: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Elizabeth R. Leggett

20. Infographics: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Beverley E. Crane

21. Meeting Community Needs: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Pamela H. MacKellar

22. 3D Printing: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Sara Russell Gonzalez and Denise Beaubien Bennett

23. Patron-Driven Acquisitions in Academic and Special Libraries: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Steven Carrico, Michelle Leonard, and Erin Gallagher

24. Collaborative Grant-Seeking: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Bess G. de Farber

Alfonzo

27. Teen Services Today: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Sara K. Joiner and Geri Swanzy

28. Data Management: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Margaret E. Henderson

29. Online Teaching and Learning: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Beverley E. Crane

30. Writing Effectively in Print and on the Web: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Rebecca Blakiston

31. Gamification: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Elizabeth McMunn-Tetangco

32. Providing Reference Services: A Practical Guide for Librarians by John Gottfried and Katherine Pennavaria

33. Video Marketing for Libraries: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Heather A. Dalal, Robin O’Hanlan, and Karen Yacobucci

34. Understanding How Students Develop: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Hannah Gascho Rempel, Laurie M. Bridges, and Kelly McElroy

35. How to Teach: A Practical Guide for Librarians, Second Edition by Beverley E. Crane

36. Managing and Improving Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Programs: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Matthew C. Mariner

37. User Privacy: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Matthew Connolly

38. Makerspaces: A Practical Guide for Librarians, Second Edition by John J. Burke, revised by Ellyssa Kroski

39. Summer Reading Programs for All Ages: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Katie Fitzgerald

40. Implementing the Information Literacy Framework: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Dave Harmeyer and Janice J. Baskin

Titles in the Series edited by Ellyssa Kroski

41. Finding and Using U.S. Government Information: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Bethany Latham

42. Instructional Design Essentials: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Sean Cordes

43. Making Library Web Sites Accessible: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Laura Francabandera

44. Serving LGBTQ Teens: A Practical Guide for Librarians by Lisa Houde 45. Coding Programs for Children and Young Adults in Libraries: A Practical

Guide for Librarians by Wendy Harrop

Finding and Using U.S. Government

Information

A Practical Guide for Librarians

Bethany Latham

PRACTICAL GUIDES FOR LIBRARIANS, NO. 41

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2018 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-5381-0715-7 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-1-5381-0716-4 (e-book)

™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Contents Preface

Part I: Background and Context

1 Introduction to Government Information

2 Types of Government Information

3 Approaches to the Research Process

Part II: How to Find and Use Government Information

4 General Resources, Search Engines, and Tools for Locating Government Information

5 Business, Economics, and Labor

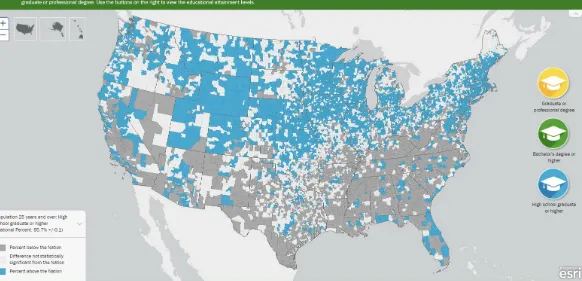

6 Census and Housing Data

7 Education

8 Environment

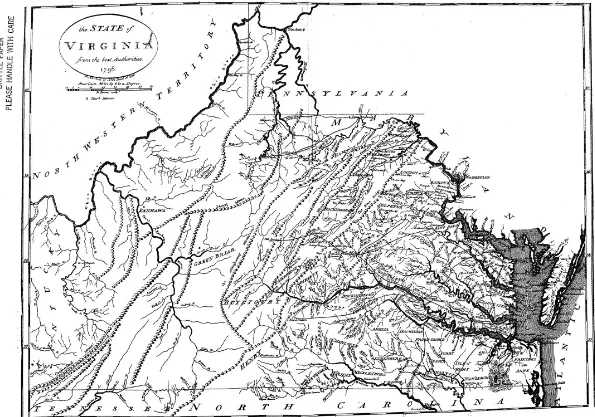

9 Geographical Information Systems, Maps, and Other Cartographic Materials

10 Health, Medical, and Consumer Information

11 Intellectual Property

12 Legislation, Law, Jurisprudence, and Criminal Justice

13 Scientific, Technical, and Statistical Information

Part III: Collection Management and Professional Development 14 Tips for Collection Development

Preface

Librarians are information professionals, and the U.S. federal government produces a massive trove of valuable information. Yet due to how federal government information is produced and organized, these resources can be more difficult to locate and effectively use than traditional information sources. Additional layers of understanding must be added to the librarian’s core skill set in order to make the most of these unique resources.

This book introduces the field of federal government information and provides a subject-based guide for government information reference sources and other issues related to government information management. The approach is one of simplicity—government information can be complicated, and it can also be intimidating for librarians who possess little experience with it. Think of this work as the sort of guidebook you would take to a foreign country when unacquainted with the culture and language. Guidebooks will not turn you into a native, but they will help you communicate, get around, and essentially get the job done. That is the goal of this book.

This work is written in plain language for practicing and new librarians in the areas of reference and other user services, as well as anyone interested in gleaning a basic understanding of how federal government information is created, acquired, organized, searched, and used. It is also written with the “inadvertent” depository coordinator in mind—those librarians who find themselves responsible for government information at their institutions but have had no background or training in this area. Those in charge of collection development will also find this book beneficial, since government information resources are often freely available, authoritative primary sources repackaged and sold by vendors to libraries at premium prices. Knowing what is freely available from the government allows libraries to be more efficient in the allocation of financial resources, which furthers collection development and management goals.

Scope

retrospective digitization projects it has begun. Many library users now prefer digital government information, though there are notable exceptions (e.g., cartographic materials). I have made every effort to provide easy access to digital resources when possible, with the caveat that this method is notoriously impermanent since it involves the use of URLs that change quite frequently.

This work is not a textbook for library and information science students (though they can certainly benefit from it, especially if they do not have the opportunity to take a government information course), and it is not intended to be an exhaustive examination of every single government information resource; such an endeavor would require multiple volumes and would not serve the audience for this book. Instead, the goal is to cover major resources and provide a ready reference for the types of sources that can answer many of the questions commonly encountered at the reference desk. Sources that will already be familiar to most practicing librarians (e.g., historical, archival, and library-related materials from the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services) are eschewed in favor of less familiar sources that can be used to answer government information questions from library users.

The scope of this book is information produced and disseminated by the U.S. federal government or under its auspices. Since the federal government aggregates state-level data in many of its sources and reaches outside our country’s borders in others (e.g., trade data), information at these levels can be found in this book. However, international/intergovernmental, state, and local government–created information is outside its scope. A few selected commercial resources are included to illustrate the ways vendors repackage government information and how those commercial resources can be weighed against freely available government information to determine which sources are best for certain applications. But the vendor resources listed are not comprehensive, nor should the inclusion of any particular commercial resource be taken as an endorsement of that product. They are provided simply to inform users about additional methods to access some types of government information.

Organization

government information collections are members of the Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP), which is the principal method of acquisition for most of these materials. Thus the history, governance, and procedures of the FDLP and the role it plays in public access to government information in the United States are covered in some detail. Chapter 2 briefly examines the available formats and methods of delivery for government information, as well as the branches of government that produce it and the few special audiences often singled out by the government as target audiences when creating its information. Chapter 3 discusses approaches to locating and using government information; some reference processes are universal, but government information reference has unique aspects that can affect the reference process, so librarians must be aware of them.

The meat of this book can be found in chapters 4–13. Taken on their own, these chapters can serve as a ready reference tool for those seeking government information broken down by subject. Parsing government information by subject can be problematic, since the information is a provenance-based system—it is beneficial to know the agency and what types of information it collects and publishes before pigeonholing subject categories to know what is available. Some agencies produce information that fits into multiple subject categories. Thus, chapters 4–13 arrange government information by the primary subjects under which most government agency publications fall. This topical list is not comprehensive but rather made up of the major topics that general users seek in the realm of government information. Each topical section also includes “practical applications” at its conclusion. These vary, from more in-depth terminology to assist with searching in certain subjects (e.g., industry information) to “how do I?” step-by-step guides geared to answering a particular question. These applications illustrate government information in action, showing the practical ways it can be used to further reference and informational goals.

Part I

T

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Government

Information

IN THIS CHAPTER

The value of federal government information

Background and history of government information in the United States Organization of government information

HE AMOUNT OF government information is vast, and it can be intimidating to the uninitiated. Even defining what constitutes “government information” is not a straightforward proposition. For the purposes of this book, we will primarily be exploring information produced and disseminated by the U.S. federal government, with side trips into the area of commercial resources, which repackage information in a meaningful way. The realm of international/intergovernmental, state, and local government information is as large; it is also beyond our scope. The goal here is to familiarize you with federal government information with an emphasis on digital methods of delivery and to provide you with the tools you need to understand how this information is:

Produced Organized Located Accessed

Effectively used

access this information and you will be a better librarian. You do not have to be depository coordinator (a term we will define later) to benefit from a working knowledge of government information sources. More importantly, your users will benefit, since they will have a more effective librarian to guide them. Government information includes sources of great usefulness, but its disparate systems of organization and the (often illogical) statutory dictates that affect its creation, access, and use can mean that library users will need even more assistance than with traditional, nongovernmental resources. You need to equip yourself with the knowledge necessary to offer that assistance.

The Value of Government Information

The U.S. federal government produces an enormous amount of information which encompasses almost every conceivable subject area. While the most familiar government information products are usually concerning law, demographics, or commerce, the government collects and disseminates information on everything from library cataloging practices to teen pregnancy to the number of forest acres impacted by the Rocky Mountain pine beetle. If your user has a topic in mind, chances are the government has collected and published information on it, probably at length. It is also possible that the government is the only source which has produced this information; while others may repackage or redistribute it, the U.S. federal government is uniquely positioned to provide primary source material. As you will read in the discussion of the history of public printing in this country, vendors have long recognized that government data is commercially valuable, and the relish with which the private sector has exploited this information has only grown with time and the use of digital methods of harvesting and delivering the information. The government itself recognizes this:

Government data is a key input to a wide variety of commercial products and services in the economy, although many of these uses may not be apparent because attribution to the Government is not required. . . . The lower-bound estimate, based on a very short and incomplete list of firms that rely heavily on Government data, suggests that Government data helps private firms generate revenues of at least $24 billion annually—far in excess of spending on Government statistical data. The upper-bound estimate suggests that this sector generates annual revenues of $221 billion. These crude estimates provide rough order-of-magnitude estimates of the range of the sector’s size and illustrate the importance of Government data as an input into commercial products and services.1

because the information it has repackaged is freely available from the government. It is not often that something truly valuable is offered for free and to everyone. This is precisely the case with the majority of government information. One simply has to know where to look for it and, once found, know how to utilize it.

Librarians have long seen it as a professional responsibility to educate information seekers about the authority of sources, and this is another area where government information demonstrates its value. As Eric Forte notes, “One of the most empowering aspects of understanding government information is the ability to conduct one’s own fact-checking.”2 While no information produced by someone can be said with certainty to be completely bias or agenda-free, government information is recognized as reliable source material. In an era when many library users get their “facts” from Facebook, checking information and statistics against official government sources can provide clarification. The digital age has also brought with it the concern of authenticity of information; since technology has changed how information products are created and delivered, that same technology has also provided a multitude of opportunities for alteration. U.S. federal government information has developed strategies to meet the challenge of verifying information—of ensuring that government information products are verified as authentic, unaltered, and “official.”

HOW DOES AUTHENTICATION WORK?

The Government Publishing Office (GPO) applies digital certificates to the government information it publishes in PDF format. Users can verify these certificates using Adobe Reader or Adobe Acrobat. Users can tell which documents the GPO has certified because a visible “seal of authenticity” with an eagle logo is added to the document; a blue ribbon icon also appears beneath the top navigation and in the signature panel. When a GPO-authenticated PDF is printed, the seal of authenticity prints on the document as well.

Background and History

right to know about the proceedings and legislation of their government. The motives of the printers were not entirely altruistic; as previously noted, government information has commercial value, and it was also lucrative for them to print and sell such documents (e.g., Acts of Parliament). By the end of the American Revolution, the concept of having access to government information as a right rather than a privilege solidified with the formal establishment of the United States of America as a country. The Continental Congress made provision for congressional journals to be printed, and Article I, Section 5, of the Constitution of the United States requires that “Each House shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same.”3 James Madison held forth his view, now taken as a mantra by government information specialists, that “A popular Government without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy, or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.”4 It is from these ideological roots that the concept of freely available government information produced through taxpayer expense was developed.

The tap for government information in the fledgling United States had been turned on, but logistical issues were yet to be resolved. In the late 1700s, Congress began accepting proposals from printers, and a small number of firms were employed to handle congressional printing. These firms soon realized that, with the increasing volume of government printing and the steady stream of revenue it provided, they could subsist almost entirely on the work commissioned by the federal government. Printers even followed Congress around, relocating from Philadelphia and New York to Washington, DC, when Congress moved to the newly established capital in 1800.

Resolution No. 25, which was passed in 1860, provided for the purchase of everything necessary to build an official, government-operated printing house— buildings, machinery, and all materials. The Government Printing Office (GPO) opened for business on March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln’s first day as president.5

The Government Publishing Office

A detailed history of the GPO is beyond the scope of this discussion, but an overview of certain aspects of its operation is necessary to understand how government information has been and currently is created, procured, published, accessed, and preserved for future use. You may notice from the heading of this section that the GPO is no longer the Government Printing Office—legislation was passed in 2014 to change its name to the Government Publishing Office, an update in terminology intended to reflect the myriad ways in which the GPO now produces government information.

The statutory foundation of the GPO originates in Title 44 of the United States Code; this legislation underpins the GPO’s mission and provides a basis for its organizational structure and operations. It is important to note that, as a government agency, the GPO is bound by statute and governmental mandate. Even what the GPO defines as a “government publication” is codified (specifically, “informational matter which is published as an individual document at government expense, or as required by law”).6 Many who delve into the world of government information find certain aspects confusing or frustrating. One encounters a great deal of: “Why do they do things this way? It would make more sense to . . .” In the majority of these cases, the GPO approaches issues the way it does because it is required to by law; modification would necessitate a literal Act of Congress.

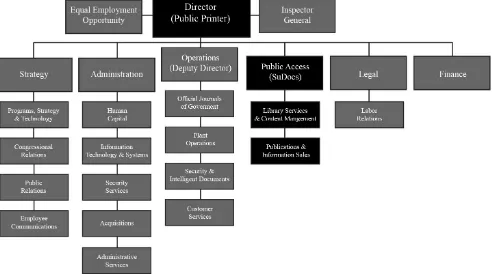

Figure 1.1. Government Publishing Office organizational chart, highlighting the Public Access division, which includes the Federal Depository Library Program. Courtesy of the author.

So how exactly is government information procured, published, and made available? The GPO is, by law, the sole source authorized for federal printing services. This does not mean that the GPO prints or produces all these materials itself; it can also serve as a procurement agency, contracting out to the private sector. Primarily, the GPO functions as a clearinghouse of sorts for all three branches of the federal government for any publication which meets the requirements of Title 44. In the past, this resulted in an enormous volume of printing, making the GPO the single largest printer not just in the United States but the entire world. With the advent of digital technologies and the concept of e-government information, the GPO saw its print production nosedive. Since the 1990s, it has downsized its print production facilities significantly while branching out in other areas. To remain viable, it has evolved—which is still ongoing—with an end goal of being the centralized source for all official government information products in all available formats.

statutory exceptions (e.g., classified and official-use-only or strictly administrative materials), this ensured that the GPO was aware of and could make available to the public the majority of government information produced by the three branches.

Born-digital government information has complicated the process. When an agency employee can compile a report, use desktop publishing software to put it into a “document” file form (e.g., PDF), and post that to an agency’s website to “publish” it, the GPO is less necessary as a middleman. It is by no means assured that every agency employee is even aware that the GPO is mandated to be such a middleman (i.e., not all agency employees may be familiar with Title 44). The GPO also has no power to compel federal agencies to use its services or notify it of these types of documents floating around outside the system (known as “fugitives”); Title 44 has no legislative teeth. In lieu, the GPO uses a sort of value proposition—that agencies can have significant cost and effort savings by utilizing the GPO for printing or digital production. In addition to print production, the GPO offers graphic design and digital media services, e-books, and web and other facilities aimed at helping government agencies provide their information in any way they choose, especially as electronic content.

Once the GPO has been made aware and seen to the production of a government information product, how is that product then made publicly available, for free, to any citizen of the United States? This is where the Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) comes in.

The Federal Depository Library Program

The origin of what would become the Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) pre-dates the GPO by nearly half a century. In 1813, Congress passed legislation to allow the provision of one copy each of the Journal of the House of Representatives and the United States Senate Journal, as well as a few other congressional documents deemed of importance, to be deposited with selected historical societies, state libraries, and universities. This resulted in the first “depository library”—the American Antiquarian Society (AAS). The responsibility for administration of this program originally rested with the Secretary of State. Through the years, it would pass to a “Superintendent of Public Printing” within the Department of the Interior, and then to the Secretary of the Interior in the 1850s. During this period, the Secretary of the Interior had the power to designate which libraries, as government depositories, would receive publications. Later legislation allowed each representative to designate a single depository from his or her district, and delegates from the territories were also included. Shortly afterward, each senator was also given the right to designate a depository in his or her state.

of importance is the Depository Library Act of 1962. The FDLP, as its structure exists today, is a product of this legislation. Not only did this act set up a hierarchy for depositories, but it also finally introduced the element of choice— the ability for certain depositories to select the publications they wished to receive. The last piece of the puzzle was added in the 1970s with the addition of an outside advisory body, the Depository Library Council to the Public Printer. Consisting of fifteen members who are appointed by the Director and serve three-year terms, and the Depository Library Council’s role is to advocate for depository libraries and the FDLP and to advise the GPO’s Director and Superintendent of Documents.

Governance and Structure of the Depository System

assessments also seek to point out the areas where a depository is succeeding or going above and beyond what is required—what the GPO refers to as “notable achievements.” This is representative of a certain shift in mindset; many libraries have voluntarily given up depository status due to staffing and space concerns, and the GPO itself has seen a reduction in staffing and other resources. Due to these factors, the approach now is more one of shepherding— the GPO wants libraries to remain in the program and has positioned itself more as a partner to help with meeting rules and regulations, rather than looking to penalize for noncompliance. The legislation also requires that depositories report to the GPO every two years; this is accomplished through the Biennial Survey, a questionnaire that depositories complete and submit online. The GPO then releases the results to the depository community.

There are approximately 1,200 libraries currently in the FDLP, and they can be one of two types of depositories: “selectives” or “regionals.” Selectives are what they sound like—depositories with a small basic collection to which they must maintain access, but outside that collection selectives are allowed to select which government publications they wish to receive.

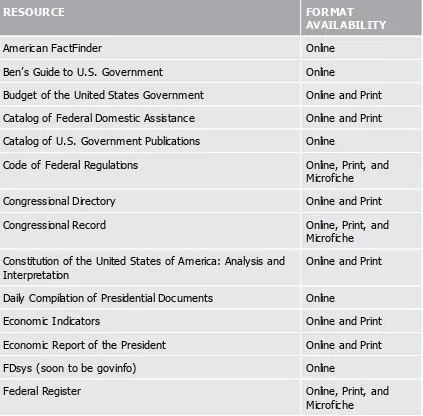

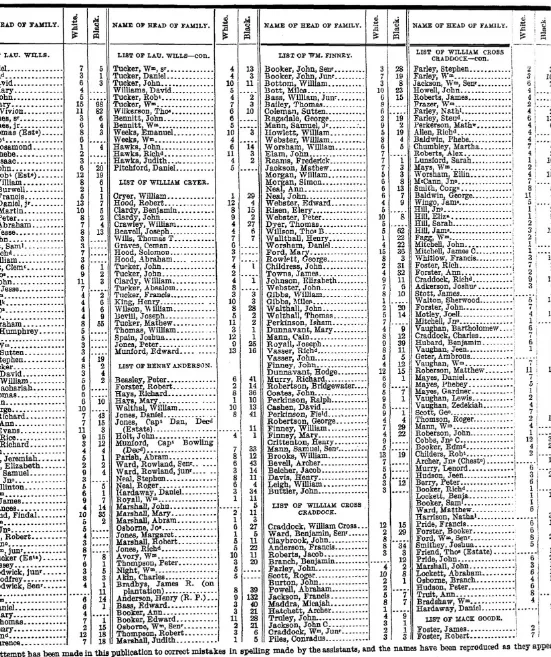

Table 1.1. Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) Basic Collection

RESOURCE FORMAT

AVAILABILITY

American FactFinder Online Ben’s Guide to U.S. Government Online

Budget of the United States Government Online and Print Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance Online and Print Catalog of U.S. Government Publications Online

Code of Federal Regulations Online, Print, and Microfiche

Congressional Directory Online and Print Congressional Record Online, Print, and

Microfiche Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and

Interpretation Online and Print Daily Compilation of Presidential Documents Online

Economic Indicators Online and Print Economic Report of the President Online and Print FDsys (soon to be govinfo) Online

Occupational Outlook Handbook Online

Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States Online and Print

Social Security Handbook Online and Print United States Code Online and Print United States Government Manual Online

United States Reports Online and Print United States Statutes at Large Online and Print

They are also allowed, within certain constraints and after following prescribed procedures, to discard publications. Each selective is required to have a depository coordinator; this is an individual who is responsible for keeping current with FDLP information, monitoring changes in regulation, liaising with the GPO, and in general overseeing depository operations for the library. Though depositories designate a coordinator—occasionally spreading these duties out across multiple positions within an institution—the final responsibility for meeting all mandates and regulations rests with the library’s top-level administration (i.e., dean, director, etc.).

Selectives report to a regional library, which is tasked with overseeing them and offering guidance and assistance, especially in the realm of collection management and materials disposal. In addition to acting as a intermediary between selectives and the GPO, regional libraries, of which there can be no more than two per state, were intended to serve as legacy collections; they were initially required to receive 100 percent of the publications available from the FDLP, and, with a few exceptions (e.g., superseded materials), to keep at least one copy in tangible form (print or microform) in perpetuity. In this way, preservation of these materials for continued public access would be assured. This resulted in an ever-expanding collection that could never be culled, a state of affairs that many regional libraries, after decades in the FDLP, began to see as a burden. In 2016, the Superintendent of Documents issued a policy statement allowing regional libraries to discard certain publications which had been retained for seven years and had authenticated digital versions available from the GPO or those which had at least four tangible copies geographically distributed within the FDLP.9 Advance approval for this disposal must be granted by the GPO, and the publications must be offered to the selective depositories within the regional’s state. This process is similar to the disposal process under which selectives have always operated: namely, that with regional approval and after offering the publication to all selectives within the state, a selective may dispose of a publication which it has held for five years.

Figure 1.2. The printed version of the List of Classes of United States Government Publications Available for Selection by Depository Libraries, 2015 revision.

While the Item List’s name suggests that selection could be made with specificity (one item number equaling one title), that is not the case. Many item numbers correspond to entire classes of publications, some of which are not helpfully labeled (e.g., Department of Agriculture, Electronic Products, Miscellaneous). The GPO has made strides over the years toward modifying the Item List to clarify what a library will be receiving if it selects a particular item number (and perhaps just as importantly, in what format that item will be received), but there is still much work to be done. The GPO also employs a practice it considers helpful: randomly adding certain item numbers to a library’s profile because the library selected an item number the GPO considers to be similar—consider it along the lines of Netflix’s type of suggestions where “because you watched Jane Eyre, we suggest you’ll enjoy this unspeakable squid-based erotica.” Government information librarians refer to this as “profile creep” and must monitor their selections to make sure they drop item numbers which result in publications they do not wish to receive (and occasionally, never selected). Understanding how government publications are selected—the item number method is codified in a statute—is essential, since it affects collection management in ways not applicable to traditional library resource acquisition.

In the past, the profile update cycle was annual; libraries could only make additions or drop item numbers once a year. Using the intuitively named Depository Selection Information Management System (DSIMS), libraries may now update their profiles continually, dropping or adding item numbers at any time. The addition of electronic products take effect immediately, as does the dropping of any item number; additions of tangible publications are “held” by the system until the beginning of the next fiscal year. Similar to ordering anything else online, tangible publications arrive at depository libraries in a cardboard box from a warehouse, usually from the larger of the GPO’s warehouses, located in Laurel, Maryland.

GPO. As is the case with much government information, the majority of these records are created by the GPO itself—the government freely provides the information, in this case through the Catalog of Government Publications (https://catalog.gpo.gov). Vendors are simply repackaging this information for libraries to purchase, with the value-added service of parsing it by library selection profile.

It bears mentioning that tangible federal government publications can be acquired outside the depository system, most notably through the GPO Bookstore. In the print era, the GPO operated some brick-and-mortar bookstores where government publications could be purchased. With the transition to a digital environment, these bookstores became a casualty of the GPO’s overall downsizing of facilities and personnel. The GPO still maintains a physical storefront location at its headquarters on North Capitol Street in Washington, DC, but the GPO Bookstore now exists primarily as an online presence (https://bookstore.gpo.gov/). Users can sign up for email alerts on new government publications by topic, and some of the recognizable titles (e.g., Code of Federal Regulations) are available for purchase and subscription. However, the purpose of the GPO Bookstore is not, as is that of the FDLP, to provide the public with access to government information; the GPO Bookstore is a cost-recovery and profit model program, so the titles it offers fall into the category of “customer favorites”—titles the GPO thinks it can sell in quantity. The vast majority of government publications are not offered for sale; membership in the FDLP is the only way to acquire them.

Organization of Government Information

far from static; as new agencies are created, old agencies die or are subsumed underneath new or modified departments, and these SuDocs symbols can change. The alphabetic symbol is followed by a number, which represents the subordinate office or sub-agency, followed by a period. A second number after the period represents the type of publication (e.g., annual report, maps and charts, etc.). This is an important feature to remember: SuDocs is a whole number system which uses periods, not decimals. This means that sorting in SuDocs order will differ from traditional library classifications—and can cause chaos for the uninitiated. After this second number is a colon; everything up to this colon is known as the SuDocs stem, and the stem represents a class of publications. Everything after the colon describes the item at hand—serial items will show a volume number, year, month, or a sequential designation. Monographs are given cutter symbols based on title rather than author. The general rule for sorting is date, letters, numbers, word, and an empty space will file before a letter or number. While this provenance-based classification is often mystifying to those first encountering it, it allows government publications to be cataloged using only the item at hand—all the information needed to create a call number can be found on the document itself since its subject does not have to be determined.

EXAMPLE OF SUDOCS CLASSIFICATION NUMBERS, SORTED

Y 4.EC 7:C 73/7 Y 4.EC 7:C 73/10

Y 4.EC 7:S.HRG.110-646 Y 4.EC 7:SA 9/2

step of creating Dewey or LC classification numbers for their government publications, and thus government information will be housed separately from the library’s main collection due to its disparate call number system. Integrated libraries, by contrast, treat government publications in the same manner as all other library acquisitions, assigning them comparable call numbers based on subject and shelving them within the main collection. Other libraries may choose a hybrid approach, creating subject-based call numbers for major government publications while sorting and shelving certain classes of them (e.g., vertical file pamphlets, microforms, and maps) by SuDocs.

Key Points

Government information encompasses a large number of resources on nearly every conceivable subject. While it is often repackaged by commercial vendors, government information obtained directly from the federal government can offer a freely accessible trove of primary source materials of great value to library users.

Federal government information in the United States is made available to the public through the Government Publishing Office (GPO), which serves as a procurement and publishing agency and a clearinghouse for information created by all government agencies.

Libraries can acquire federal government information through membership in the Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) or through purchasing some titles directly from the GPO, which oversees the FDLP.

The FDLP is governed by Title 44 of the United States Code; the responsibilities this entails for depository libraries are excerpted and provided for them in the Legal Requirements & Program Regulations of the Federal Depository Library Program.

There are two types of depository libraries: selectives and regionals. Selective libraries are allowed to choose which publications they wish to receive, and they can also deselect publications after certain restrictions are met. Regional libraries oversee selectives and are intended to serve as legacy collections and preservation repositories; they must select 100 percent of the publications available through the FDLP.

Each depository library must have a designated depository coordinator who is responsible for keeping current with FDLP information, monitoring changes in regulation, liaising with the GPO, and overseeing depository operations. Final responsibility for compliance with mandates and regulations rests with the library’s top-level administration.

classification system based on issuing agency, rather than a subject-based system such as Library of Congress (LC) or Dewey.

Notes

1. Fostering Innovation, Creating Jobs, Driving Better Decisions: The Value of Government Data, (U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, 2014), 4.

https://esa.gov/sites/default/files/revisedfosteringinnovationcreatingjobsdrivingbetterdecisions-thevalueofgovernmentdata.pdf.

2. Cassandra J. Hartnett, Andrea L. Sevetson, and Eric J. Forte, Fundamentals of Government Information: Mining, Finding, Evaluating, and Using Government Resources (New York: Neal-Schuman, 2016), 5.

3. U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 5.

4. James Madison, Letter to W. T. Barry (August 4, 1822).

5. U.S. Government Publishing Office, Keeping America Informed: 150 Years of Service to the Nation (U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2011), 5–8.

6. Title 44, United States Code, Section 1901, 62. 7. Title 44, United States Code.

8. U.S. Government Printing Office, Legal Requirements & Program Regulations of the Federal Depository Library Program (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2011).

9. Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office, Public Policy Statement 2016-3: Government Publications Authorized for Discard by Regional Depository Libraries (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2016). https://www.fdlp.gov/file-repository/about-the- fdlp/policies/superintendent-of-documents-public-policies/2737-government-publications-authorized-for-discard-by-regional-depository-libraries-1.

N

CHAPTER 2

Types of Government Information

IN THIS CHAPTER

Available formats and delivery methods Information by branch of government

Special audiences for government information

OW THAT YOU ARE familiar with the basics of how U.S. federal government information is created and organized, let’s take a look at how that information is presented. We will look at the available formats or methods of delivery, the types of information by the branches of government, and some of the specific special audiences that government information targets.

Available Formats and Delivery Methods

determines the delivery method for its content, and this decision might be made based on cost, habit, or even whim—not end-user preference. This is why depository librarians and general users often ask for a particular title to be offered in a specific format, and these pleas fall on deaf ears. Commercial publishers have a single goal in mind: sell a book (e-book, database, etc.), and make as much profit as possible while doing so. This means taking into consideration what buyers want. Since most government agencies are not looking to sell their products, this is a non-issue for them. Thus an examination of the formats available from the GPO is in order.

Currently, approximately 25 percent of the classifications of publications the GPO offers to depository libraries are available in print format.2 Translating classification formats into the actual number of items in print is difficult since, as outlined in Chapter 1, a single item number classification can equal a single publication or hundreds of different publications. While one might assume that “print equals book,” that is not the case. When using the List of Classes for selection, print classes are designated by a the letter “P,” and they include monographs but also items such as journals, newsletters, maps, posters, kits, flash cards, brochures and pamphlets, forms, calendars, coloring books, puzzles, and more. Also, the format designation in the List of Classes is based on what an agency tells the GPO. Some agencies do not bother to notify the GPO of what format they plan to use in publishing a particular item. In such a case, no format designation is listed, and the publication could appear in any format. Many publications will also be listed in hybridized format (e.g., “P/EL”), which means that publications under that classification stem could be released in either format or both.

Cartographic Materials

A significant number of the printed materials offered from the GPO are cartographic in nature—this includes everything from world and country maps published by the Executive Office of the President to vehicle and trail use maps for national parks. Other examples include:

nautical and navigational charts

airport terminal charts and aeronautical plans topographical maps

soil, geological, and mineralogical surveys land use maps

atlases

political maps

T he Federal Depository Library Handbook even includes an entire appendix geared toward map librarianship and selection of cartographic materials from the GPO.3 Since the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is a large government agency, it will come as no surprise that this agency produces a great number of the cartographic materials published by the U.S. government. While these materials are selected by depository libraries from the GPO using the print format designation in the List of Classes, they can also be purchased directly from the USGS through the USGS Store (https://store.usgs.gov). As will be seen in Chapter 9 under the section on Geographical Information Systems, Maps, and Other Cartographic Materials, tools such as this are helpful to end users, since print is not the only format in which many cartographic materials are now being offered by the GPO. A large number of these materials have recently been migrated to a digital format which, given how they are meant to be used, makes them far less convenient for many users. Thus, when the digital version is available through the GPO, many users will still turn to printed versions from the agency itself, even if that means they must pay to purchase their own printed copy.

Microforms

government information often found on the format. As previously mentioned, the greatest number of microfiche was dedicated to congressional materials, but the Department of Education was another significant contributor, as were agencies that created technical reports.

CDs and DVDs

Like microforms, CDs and DVDs as formats for the dissemination of information are becoming obsolete. Many desktops and laptops on the market today have eliminated the disk drive altogether. In the early 2000s, depository libraries were required to meet certain “minimum technical requirements” by the GPO for the workstations the public used to access government information within library buildings. This included computers with drives to read the formats the GPO used for dissemination: CDs and DVDs. The GPO’s revised editions of these requirements eventually fell by the wayside, and libraries which update their public access machines on a regular basis have now reached the point where many of the machines no longer have the capacity to read such formats. The types of government information which were usually disseminated on CD or DVD included geographic information system (GIS) programs, training programs and/or videos, census data, and occasionally monograph publications in PDF format. These CDs and DVDs, as is the case with microfiche, are now a very small percentage—approximately 1 percent—of the classes of publications available for selection. Most libraries that consistently weed out and appropriately manage their collections will have already transferred the PDFs to online-accessible versions and deselected the other software-based CDs and DVDs. This format retirement has not been without pitfalls. As just one example, many libraries deselected DVDs containing detailed data sets from the 1990 Decennial Census when this information became available through the online American FactFinder tool (https://factfinder.census.gov), only to learn later that the detailed data was intended to be kept in American FactFinder solely for the latest two censuses. Historical census reports are available, but they do not contain all of the data that was found on these DVDs. Many libraries that deselected them in favor of relying on American FactFinder now rue that decision.

Digital

variety of challenges for those who manage government information collections. Even the manner in which digital government information is created—digitized from a tangible format or born digital—is an area that has been problematic because standards can vary from agency to agency and may result in a different end product. These differences were one of the driving factors behind the creation in 2007 of the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative (http://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/), which seeks to provide a measure of consistency and sustainability for digitized and born-digital historical, cultural, and archival content from federal agencies. It bears noting that this type of information is by no means the bulk of the information created by federal agencies, ensuring that a great deal of digital government information falls outside these guidelines.

Since it can be easily altered, authentication is another concern of digital government information, especially when this information represents the official record. To address issues of alteration, the GPO has developed methods to ensure authenticity (see the textbox on page 5), primarily through the use of digital certificates. The GPO digitally signs the documents, usually in PDF format, and the documents are given a Seal of Authenticity (see Figure 2.1). The seal offers end users an easily visible method to determine that their document is the official version of the publication issued by the GPO.

Figure 2.1. The Government Publishing Office Seal of Authenticity, used to designate authentic versions of government information vetted and produced by the GPO.

community about the concept of a digital deposit—whereby the GPO would deposit digital copies of publications with the depository, which would then maintain and preserve them—the majority of depositories do not archive digital government information in bulk since they have neither the time nor the resources to do so, especially to continually migrate to ensure preservation. The impetus for the preservation of this format has rested primarily with the GPO, though it has and continues to look to Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) libraries for ways to partner in shouldering this responsibility. One example can be found in the GPO’s partnership with the University of North Texas Libraries to create CyberCemetery (examined further in Chapter 4) which captures, caches, and provides permanent public access to the websites of defunct agencies and commissions. There is a standing call for libraries, agencies, and other entities to reach out to the GPO with proposals for partnership, and as of this writing, eight libraries are currently serving as preservation stewards in partnership with the GPO. The libraries tend to choose projects that correlate to unique items already in their collections or items that are heavily used by their primary users. So far, the majority of these preservation efforts involve the retention and digitization of tangible government publications (e.g., Works Progress Administration posters). Given that there is no systematic nature to these types of projects, the result is a patchwork of random pieces as opposed to a comprehensive system of preservation based on particular standards of selection.

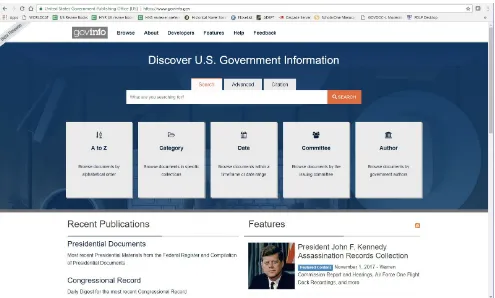

Resources Information Center (ERIC) educational reports, and presidential documents. Many of these publications, arranged as collections, are retrospective back to the early to mid-1990s, which is when the digital versions of the information first became available, but there are a few collections that have more historical timelines. FDsys itself is nearing its end—it is to be replaced with govinfo (www.govinfo.gov). Launched in 2016 and still in beta at the time of this writing, govinfo is intended to provide a one-stop shop for public access, content management, and digital preservation. More information about both FDsys and govinfo can be found in Chapter 4.

Information by Branch of Government

As taught in most grade schools, the three branches of government are the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. It is a simple enough breakdown, but given the behemoth that the U.S. federal government has become since its inception, it is beneficial to take a brief look at each branch of government, the major entities that make up each, and the information each produces. It is essential to understand this because, as it will become apparent in Chapter 3 when approaches to government information research processes are examined, provenance is more important with government information than some other types of reference—knowing which agency produces what kind of information is a building block for the effective and timely location of resources.

Executive

Most equate the executive branch entirely with the Executive Office of the President, but it is, in fact, a conglomeration of agencies, all of which are meant to serve an administrative function: to execute the laws of the land and enforce and implement the policies put forth by the government. The executive branch contains not only the president, vice-president, and the members of the president’s cabinet, but all of the major cabinet-level departments which we think of as being content producers for subject-based government information:

Agriculture Commerce Defense Education Energy

Health and Human Services Homeland Security

Housing and Urban Development Interior

State

Transportation Treasury

Veterans Affairs

These departments oversee a variety of sub-agencies, offices, and commissions, and in addition to these major departments, there are also many independent agencies and government corporations. Everything from the Central Intelligence Agency to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and much more can be found under the umbrella of the executive branch. Unsurprisingly, the amount of information this branch generates is vast, as are the subject areas it encompasses.

Legislative

In comparison with the executive branch, the organization of the other two branches of the U.S. federal government is refreshingly less complicated. The legislative branch, made up of the elected officials of the United States Congress, makes the laws which the executive branch is tasked with executing. In addition to senators and house representatives and all their staff, there are also a few other agencies and offices which can be found in this branch:

Architect of the Capitol

Congressional Budget Office

Government Accountability Office Government Publishing Office Library of Congress

United States Botanic Garden

As evidenced by the fact that at one point the Government Publishing Office operated under the Department of the Interior in the executive branch, agencies, offices, and government entities can move around. Just because an office originated under a specific agency or department does not mean that it will continue to reside there (or, indeed, that it will continue to exist at all).

Judicial

Administrative Office of the United States Courts Federal Judicial Center

United States territorial courts United States courts of appeals

United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims United States district courts

United States Court of Federal Claims United States Court of International Trade United States Sentencing Commission United States Tax Court

The structure of the federal judicial system and some of its most important resources are examined in greater detail in the Law and Judicial Interpretation section of Chapter 12.

Special Audiences

Information of use to almost every citizen is created by the U.S. government, and much of it is directed toward a general audience. There are, however, a few special audiences worth mentioning, since there is a large amount of information produced specifically with these groups in mind. The way the information is presented often differs from what is intended for general audiences, and the information often appears as a subset of subject resources from different government agencies.

Educators

the gamut, from long-term studies following students through their educational careers to instructional tips for educators in different situations. The focus on education is not limited strictly to the ED; many government organizations (e.g., the National Parks Service, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the GPO, the USDA, and even the U.S. Postal Service) produce lesson plans, publications, and other information intended to be used by teachers with their students in the classroom.

Children

Figure 2.2. Cartoon version of Benjamin Franklin created to engage children in the activities found on the “Ben’s Guide to the U.S. Government” website (https://bensguide.gpo.gov/).

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) takes a similar approach using a sub-site called the “NASA Kids’ Club” (https://www.nasa.gov/kidsclub/index.html) to offer age-appropriate information on everything from the International Space Station to the Mars Rover and items NASA thinks children will find engaging, such as ringtones fashioned from the sounds of historic space missions. The products geared toward children are not limited to the digital environment—puzzles, coloring books, picture books, and more are regularly distributed to depository libraries through the FDLP. The National Parks Service (NPS) has even teamed up with Sesame Street characters to make videos promoting child-friendly activities and safety tips for use in the National Parks, as well as creating the Junior Rangers program, aimed at children ages 5–13. These are just a few examples of the types of government information that are created for children.

Figure 2.3. Ready.gov emergency supply preparation checklist in Hindi, just one of many languages in which U.S. federal government publications are offered.

Seniors and the Disabled

The Older Americans Act of 1965 was designed to create a suite of social services aimed at assisting the elderly (defined as individuals aged 60 or older). The Act has continually been reauthorized and expanded. There are a variety of government programs that have been instituted to provide for seniors— Medicare and Social Security being two of the most readily recognizable. The Administration on Aging (AoA), a part of the Department of Health and Human Services, was created as a part of the Act to serve as a sort of focal point for all federal programs and information for seniors, a clearinghouse to offer assistance on government programs for the elderly. The AoA contains a variety of offices which provide targeted information for seniors and their caregivers: Supportive and Caregiver Services, Nutrition and Health Promotion Programs, Elder Justice and Adult Protective Services, and more.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 was a piece of legislation designed to prohibit discrimination against the disabled. Ever since the passage of this law and the subsequent guidelines and enforcement measures, a large amount of information targeted at the disabled has been created by the government on topics including labor, housing, health care, education, transportation, and more. Most of the primary Cabinet-level departments have sections on their websites and sometimes within their organizational structures that deal with the rights of and services for the disabled (e.g., the Office of Disability Integration and Coordination of the Federal Emergency Management Agency at the Department of Homeland Security). It has also resulted in the offering of tangible government materials geared toward those with specific disabilities. Since it is one of the major agencies that provides benefits to disabled persons, the United States Social Security Administration (SSA) publishes many of its informational materials in formats most useful for those with a particular disability—as just one example, the SSA offers braille-format publications to provide access for the blind.

Veterans

specifically to information aimed at veterans and their families.

Key Points

Government information is available in a variety of formats, the information produced by the three branches of government differs widely by branch, and while most government information is written with a general audience in mind, there are certain audiences that government agencies sometimes target.

Formats available for government information include printed and tangible materials, cartographic materials, microforms, CDs and DVDs, and born-digital and digitized tangible materials. Of these formats, digital is the most prevalent and also the most preferred by end users. Government information is produced by the three branches of the government: executive, legislative, and judicial. The executive branch has, by far, the widest range of subject coverage due to the variety of departments and agencies under its umbrella.

Special audiences often directly targeted by the government in the production of information include educators, children, individuals with limited English proficiency, seniors, the disabled, and veterans. In many cases, this is due to legislation created specifically for these groups.

Notes

1. “Government Documents Initiative Planning and Advisory Group Charge,” HathiTrust Digital Library , August 1, 2017, https://www.hathitrust.org/usgovdocs_planning_charge.

2. “Documents Data Miner 2,” Wichita State University, 2017, http://govdoc.wichita.edu.

3. Library Programs Service, U.S. Government Printing Office, Federal Depository Library Manual, Appendix C (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993).

4. U.S. Government Printing Office, Digital Preservation at the U.S. Government Printing Office: White P a p e r (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008),

https://www.govinfo.gov/sites/default/files/media/preservation-white-paper_20080709.pdf.

5. U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness, Fiscal Year 2018 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2017),

https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/budget.pdf.

M

CHAPTER 3

Approaches to the Research Process

IN THIS CHAPTER

The reference interview The referral

The proper foundation Admitting ignorance

ANY ASPECTS OF THE reference and research process are universal. No matter what type of research is being performed or the subject of the information, certain things about the process remain the same. Government information, due to the unique nature of its production and dissemination, can add additional layers to the research and reference process. We will look at the process with these differences in mind, incorporating and addressing them to achieve a successful result.

The Reference Interview

For librarians, every research process starts with a reference interview of sorts. In the past, users walked up to a reference desk and asked a question. Maybe they picked up the phone and called. Librarians now experience the reference process through a variety of additional access methods, such as email, texts, or chat. The objective is always the same: connect the user with the information he or she needs—the information he or she really needs. This information may not actually be what that user initially asks for. This is where the reference interview comes in.

i s pleasant for them. Listen, pay attention, and don’t interrupt or jump to conclusions about what you think they might want. Don’t chastise them for waiting until fifteen minutes before closing to ask a question or make them feel insecure or belittled for what they don’t know. Don’t give the impression that they are an unwelcome interruption or that you don’t have time for them. Don’t give them caveats about how difficult their question will be to answer (and government information questions can be some of the most difficult you may receive). Instead, focus on helping them. If you’re a librarian, it’s what you’re there for—never lose sight of that.

Ask open-ended questions to assist with narrowing queries. Think in terms of working from expansive down to minute. The average library user often asks for something broad when what is being sought is something quite specific. If you don’t take the time to narrow that field before you begin searching, you can waste a great deal of effort (not to mention never finding what was being sought). Or you might possibly send the user on a wild goose chase—you may have sent them off with exactly what they asked for, but it isn’t what they actually need. A typical interaction may go something like this: the user walks up and asks where the medical books are. You could give him a call number and send him on his way. If you do, you are a bad reference librarian, because: 1) you don’t send users off on their own, and 2) what he’s really after is a specific statistic on infant mortality that can be found in the Centers for Disease Control’s National Vital Statistics System. But it’ll take several questions from you to drill down that far. This type of interaction happens a great deal with government information; users may not understand where the information they seek is being generated or they think they do but are incorrect. Even when they’re aware it is government information that they are seeking, factors such as unfamiliarity with government structure and terminology can result in wrong ideas about where to look or even what to look for. A user may say he or she needs to look at judicial material, but in the course of the reference interview, you discover that what the user is actually seeking is an executive order and the reference process shifts to a different set of resources. The first step in the process is to get at what the user truly needs. To do that, you need to ask questions until you are certain exactly what it is you are being asked to find. Then you can start your search.