Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:58

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

THE 2008 SHIPPING LAW: DEREGULATION OR

RE-REGULATION?

Howard Dick

To cite this article: Howard Dick (2008) THE 2008 SHIPPING LAW: DEREGULATION OR RE-REGULATION?, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 44:3, 383-406, DOI: 10.1080/00074910802395336

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910802395336

Published online: 06 Nov 2008.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 140

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/08/030383-24 © 2008 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910802395336

THE 2008 SHIPPING LAW:

DEREGULATION OR RE-REGULATION?

Howard Dick*

University of Melbourne

The restoration of democracy since 1998 has been accompanied by a revival of eco-nomic nationalism in Indonesia. This can be seen clearly in the fi eld of shipping

and ports. In the 1980s the government deregulated the highly protected and in-effi cient shipping industry to facilitate a non-oil export drive. Since 1999 a rising

tide of economic nationalism has seen a gradual process of re-regulation that has restored some of the old protectionist devices. This new protectionism is likely to frustrate government policies to improve logistics and facilitate trade. At the same time, there has been a mild liberalisation of state control over the ports sector. This paper addresses the key economic regulations embodied in the new Law 17/2008 on Shipping and assesses their potential impact. It highlights an ongoing confl ict in

government between protectionism/rent-seeking and development.

INTRODUCTION

Ever since the professional economists known as the ‘technocrats’ came into government in Indonesia in 1966, macroeconomic management has been much easier than microeconomic reform.1 Macroeconomic stability is widely accepted

as being a good thing and monetary and fi scal targets do not impinge directly

on vested interests. Microeconomic reform has been another matter. Here the technocrats have struggled to make headway against entrenched bureaucratic and rent-seeking interests. Their one notable period of success was during the non-oil export drive from the mid-1980s to the Asian crisis of the late 1990s. A non-oil export drive became a national policy priority when the collapse of oil prices from their 1981 peak led to a balance of payments crisis. The export drive policy focused upon removing some of the regulatory obstacles to the growth of trade. Presidential Instruction (Inpres) 4/19852 transferred responsibility for

* h.dick@unimelb.edu.au. I am grateful to David Hawes, David Ray, Thee Kian Wie and three anonymous referees for their advice on previous drafts. Research was assisted by an Australia Research Council (ARC) grant. Those who gave advice and the ARC bear no responsibility for the final version.

1 Thee (2003) provides a good insight into the role of these economists as ministers.

2 Instruksi Presiden Republik Indonesia No. 4 Tahun 1985 Mengenai Kebijaksanaan Kelancaran Arus Barang untuk Meningkatkan Kegiatan Ekonomi [Inpres 4/1985 on Policy on the Flow of Goods to Boost Economic Activities].

cbieDec08b.indb 383

cbieDec08b.indb 383 31/10/08 4:53:00 PM31/10/08 4:53:00 PM

customs clearance from the utterly corrupt customs service to the Swiss fi rm

Société Générale de Surveillance (SGS). Restrictions on the access of foreign-fl ag

shipping to Indonesian ports were also abolished, allowing Indonesia to benefi t

from the size and effi ciency of Singapore as an international container hub for

general cargo. Two more deregulation packages followed in 1988—‘Pakto’ (the October package) and ‘Paknop’ (the November package)—which, among other things, deregulated inter-island shipping. As the costs of shipment fell, so the volume of trade increased. Indonesia became part of emerging global produc-tion networks, and this led to expansion of labour-intensive manufacturing and lower unemployment (Hill 2000; Thee 2003).

Unfortunately this deregulation drive did not meet the Scott Jacobs test of sus-tainability (Jacobs and Astrakhan 2006). The virtuous cycle of reforms had come under pressure from entrenched rent-seeking interests even before the Asian crisis. In 1992 a new shipping law (Law 21/1992 on Shipping) was promulgated, embed-ding strong regulatory powers.3 Then in 1995, when non-oil exports looked secure,

the president gave in to the new director general of customs—who happened to be related to him by marriage—and restored the customs service to its former role. After the Asian crisis and the resignation of President Soeharto in May 1998, the transitional Habibie government restored many elements of the former mari-time regulatory regime through Government Regulation (PP) 82/1999,4

imple-menting powers embodied in the 1992 shipping law. After a sustained lobbying effort by the Indonesian National Ship-owners Association (INSA) in conjunction with the Directorate General (DG) of Sea Communications, the Megawati gov-ernment drafted what became Inpres 5/20055 to give presidential imprimatur to

restoring cabotage—that is, reserving domestic shipping routes for national-fl ag

vessels—and consolidating the regulatory regime. This highly protectionist and interventionist legislation was promulgated early in the life of the Yudhoyono government (in March 2005) without any proper analysis or scrutiny. Finally, Law 17/2008 on Shipping6 was approved by parliament and promulgated in May

2008. The new law updates that of 1992 in light of subsequent regulations and presidential instructions.

Under the cloak of economic nationalism, it appears that the government is all but de-coupling transport policy from trade policy, turning the clock back to the time before the non-oil export drive of the 1980s. Although economic goals of effi ciency, competitiveness and development are recognised in the preamble and

objectives (article 3) of the 2008 shipping law, they are much diluted by defence, strategic and nationalist concerns. While in 2005 the president had set the target of a 20% increase in the value of trade by 2008, the means to achieve this are very little

3 Undang-Undang No. 21 Tahun 1992 tentang Pelayaran [Law 21/1992 on Shipping], 17 September.

4 Peraturan Pemerintah [PP] Republik Indonesia No. 82 Tahun 1999 tentang Angkutan di Pengairan [PP 82/1999 on Sea Transport], 5 October.

5 Instruksi Presiden (Inpres) Republik Indonesia No. 5 Tahun 2005 tentang Pemberdayaan Industri Pelayaran Nasional [Inpres 5/2005 on the Development of the National Shipping Industry], 28 March.

6 Undang-Undang No. 17 Tahun 2008 tentang Pelayaran [Law 17/2008 on Shipping], May.

cbieDec08b.indb 384

cbieDec08b.indb 384 31/10/08 4:53:01 PM31/10/08 4:53:01 PM

within the control of the responsible Minister of Trade. Customs comes under the Ministry of Finance, and transport under the Ministry of Communications, whose world view and modus operandi are still heavily infl uenced by the military staffi ng

and culture of the New Order. The Minister of Finance is overhauling the staffi ng

and working of customs to improve its effi ciency and integrity, but meanwhile

the Ministry of Communications and the DG of Sea Communications still seek to apply protectionist policies to increase the size of an ineffi cient Indonesian-fl ag shipping fl eet and maintain state control of ports. Meanwhile, no-one takes

proper responsibility for marine safety—the one form of transport policy inter-vention that is absolutely essential.

The situation is the more serious because Indonesian government policy all but ignores the shift of international business towards global supply chains and logistics. In abstract the government is committed to increasing trade, but the country’s logistics systems are becoming less rather than more effi cient. This is

partly because of a 10-year hiatus in infrastructure investment that is only now being addressed. However, it is also attributable to heavy-handed government intervention that is insensitive—even hostile—to market forces. As Athukorala (2006) has documented, Indonesia is disengaging from global supply chains; trade in manufactures is languishing, with unhappy consequences for unemploy-ment and poverty.

This article seeks to contribute both to a broad debate on the consequences of economic nationalism and, more specifi cally, to understanding the relationship

between trade policy and transport policy in Indonesia. Its leitmotif is the swing of the policy pendulum from regulation to deregulation and back to regulation. By way of context, it fi rst summarises the path-dependent factors underpinning the

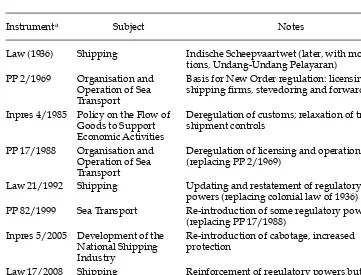

former regulatory regime, then reviews the deregulation of the 1980s. The body of the article sets out and analyses in detail the economic aspects of the 2008 ship-ping law in relation to the preceding PP 82/1999 and Inpres 5/2005 (summarised in table 1).7 The article then explores the impact in terms of cabotage, logistics,

marine safety and development of the shipping industry.

FROM REGULATION TO DEREGULATION

Policy usually embodies the mindsets and assumptions of previous generations, and this is certainly true of Indonesia’s maritime policy.8 Before independence,

inter-island shipping, including shipping to and from Singapore, was the vir-tual monopoly of the Dutch-owned KPM (Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij, or Royal Packet Company), which operated under contract as a virtual government instrumentality. Following independence and the failure of negotia-tions to establish a joint venture company between the state and KPM, the new

7 There is some diffi culty in directly comparing the various items of legislation because

of the sometimes wide gap between the general principles of law and the detail of imple-menting regulations. For example, the regulatory principles of Law 21/1992 on Shipping came into force while the deregulation of PP 17/1988 still applied. The new Law 17/2008 is much more explicit on economic regulation than Law 21/1992, but PP 82/1999 continues to apply until new implementing regulations are promulgated.

8 More detail can be found in Dick (1985, 1987).

cbieDec08b.indb 385

cbieDec08b.indb 385 31/10/08 4:53:01 PM31/10/08 4:53:01 PM

Indonesian government sought to reduce the role of the KPM by encouraging private operators, establishing a state-owned inter-island shipping corporation (Pelayaran Nasional Indonesia, or Pelni), and regulating tariffs and operating conditions. After the assets of the KPM were seized in December 1957 along with those of other Dutch enterprises, inter-island shipping suddenly became cha-otic, with few experienced operators, heavy reliance on chartered tonnage, and almost no regular scheduled services. A new Ministry of Shipping sought, with-out much success, to impose order. In 1964 the new Minister of Shipping in the Soekarno government, Ali Sadikin, issued PP 5/1964 to categorise and rationalise the number of fi rms and impose a regular liner system. Fine-tuned in PP 2/1969,9

this approach remained in place until the deregulation of 1988. The key assump-tion was that the government, through the DG of Sea Communicaassump-tions, needed in the public interest to determine the commercial guidelines for the industry, including the number of fi rms, shipping capacity, routes, the allocation of vessels

to routes, and the freight and passage rates to be charged. This was nothing less than central planning at a sectoral level. Given the enormity of this task and the

9 Peraturan Pemerintah No. 2 Tahun 1969 tentang Pe nyelenggaraan dan Pengusahaan Angkutan Laut [PP 2/1969 on Organisation and Operation of Sea Transport], 18 January.

TABLE 1 Main Changes to Shipping Regulations, 1936–2008

Instrumenta Subject Notes

Law (1936) Shipping Indische Scheepvaartwet (later, with modifi

ca-tions, Undang-Undang Pelayaran) PP 2/1969 Organisation and

Operation of Sea Transport

Basis for New Order regulation: licensing of shipping fi rms, stevedoring and forwarding

Inpres 4/1985 Policy on the Flow of Goods to Support Economic Activities

Deregulation of customs; relaxation of trans-shipment controls

PP 17/1988 Organisation and Operation of Sea Transport

Deregulation of licensing and operation (replacing PP 2/1969)

Law 21/1992 Shipping Updating and restatement of regulatory powers (replacing colonial law of 1936) PP 82/1999 Sea Transport Re-introduction of some regulatory powers

(replacing PP 17/1988) Inpres 5/2005 Development of the

National Shipping Industry

Re-introduction of cabotage, increased protection

Law 17/2008 Shipping Reinforcement of regulatory powers but simplifi cation of licensing and port

manage-ment (updating and replacing Law 21/1992)

a Undang-Undang = Law; PP = Peraturan Pemerintah (Government Regulation); Inpres = Instruksi

Presiden (Presidential Instruction).

cbieDec08b.indb 386

cbieDec08b.indb 386 31/10/08 4:53:01 PM31/10/08 4:53:01 PM

lack of expertise to fulfi l it satisfactorily across such a far-fl ung archipelago, other

responsibilities such as the monitoring of maritime safety were neglected. This central planning approach to maritime transport had other perverse out-comes. First, ship-owners came to accept that the only way to do business was to ignore and, if need be, to bribe their way around the mass of inconsistent and unworkable regulations. The resultant equilibrium was that bureaucrats collected their rents and bribes while the industry did more or less what it liked. Secondly, INSA became primarily a lobby group for industry dealings with the government. After 1969 it effectively sub-contracted daily management of the regular line sys-tem from the Directorate General, which gave ship-owners a deal of autonomy and required them to approach the Directorate General only on matters that required permits, such as to extend a licence, import a new ship or vary a route. This arrangement worked after a fashion, but it embedded ineffi ciencies and high

costs because market pressures were so greatly impeded.

Regulatory constraints became tighter in response to the new technology of con-tainerisation. Whereas hitherto general cargo ships had loaded cargo for Europe or America from all around the archipelago, perhaps taking a month in doing so, now large mother ships would stop just one or two days in Singapore to discharge and load cargo in pre-fabricated steel boxes. Indonesian ports were slow to acquire the necessary facilities and, when they did so, lacked the cargo fl ow to attract

the large specialised ships serving the Europe and trans-Pacifi c trades. The new

logistics therefore required Indonesian goods to be shipped in conventional form to Singapore for containerisation, or to be containerised in Indonesia and carried on specialist small feeder ships for immediate trans- shipment in Singapore. The Indonesian government sought to protect the direct and still conventional liner trade to Europe and America through Indonesian ports by denying feeder ships access to Indonesian ports. In 1975, at a time of good relations between Indonesia and Singapore, the Singaporean government consented to an agreement between INSA and the Singaporean Ship-owners Association to regulate the trade between the two countries. In 1980, Belawan (Medan), Jakarta, Surabaya and Makassar were designated as ‘gateway ports’ for Indonesian export cargoes. Indonesian shippers were thereby denied the lower costs of trans-shipping containers on large and fast ships through Singapore and were left at the mercy of increasingly outmoded and ineffi cient Indonesian ship-owners.

Even after Inpres 4/1985 swept away the corrupt customs service and aban-doned the ‘gateway’ policy, thereby opening Indonesian ports to direct feeder shipping links with Singapore, the regulatory interest remained strong. The bureaucracy attempted to fi ght back by hastening the passage of a new shipping

law to replace the colonial Indische Scheepvaartswet of 193610 and

accompany-ing legislation which, although translated into Indonesian, had remained in force with only minor revisions. Drafting of the new and more protectionist legislation by the DG of Sea Communications had proceeded slowly because of the many intricacies, confl icts and issues involved in a complete revision and updating of

the law. It would have been completely inconsistent with the non-oil export drive and have risked alarming the economic ministers.

10 Indische Scheepvaartswet (Staatsblad Tahun 1936 No. 700) [Indies Shipping Law].

cbieDec08b.indb 387

cbieDec08b.indb 387 31/10/08 4:53:02 PM31/10/08 4:53:02 PM

The deregulation of inter-island shipping introduced by PP 17/1988 on the Organisation and Operation of Sea Transport11 was revolutionary in that it sought

to defi ne the role of the sea transport industry in a way that was consistent with

national developmental goals. For the fi rst time in Indonesia’s maritime law it was

stated that sea transport should be carried out in the public interest and that there was a principle of effi ciency. These concepts were elaborated in the text (II.2–3):

Sea transport, which is one of the means for realising the Archipelago Vision (Wa-wasan Nusantara), specifi cally in terms of increasing national economic unity, shall

be organised as part of an integrated system of national communications.

The organisation of sea transport shall be oriented to the goals of:

(a) providing infrastructure, equipment and sea transport services that are safe, fast, orderly and at a cost that is affordable and consistent with the needs of the public, nation and state;

(b) realising certainty and orderly operations in the fi eld of sea transport to support

the development of other sectors;

(c) developing the potential of sea transport in accordance with developments in the national and international situation.

Although PP 17/1988 embodied the goal of developing the shipping industry, this had to be done in a way that supported other sectors of the economy and did not burden them. The impulse for deregulation was recognition that national shipping fi rms were being handicapped by the heavy-handed regulatory regime

embodied in PP 2/1969. The opening up of Indonesian ports to foreign-fl ag feeder

shipping by Inpres 4/1985 had placed even effi cient domestic fi rms under great

pressure because they were at a regulatory and cost disadvantage in carrying cargo to Singapore, while seeing cargo shift from inter-island to direct feeder ship-ping. PP 17/1988 was therefore intended to ‘level the playing fi eld’ so that

well-managed national shipping fi rms could realise their potential.

Accordingly, centralised regulatory control was abandoned. Shipping com-panies were given complete autonomy over the routing of their ships and were subject only to safety requirements (II.7) and obligations to report ports of origin and destination and cargoes carried to the appropriate port administrations (II.8). National shipping companies could own or charter foreign-fl ag vessels for

domes-tic trade provided this was reported (II.5). Although previously foreign-fl ag ships

could be used under dispensation, this provision was a signifi cant weakening of

cabotage. Foreign-fl ag ships could trade between foreign ports and Indonesian

ports provided they appointed a local agent, which no longer had to be a domestic shipping company (II.6). Licensing was simplifi ed. The formerly separate licence

categories of inter-island (nusantara), specialist (khusus), offshore (lepas pantai) and local (lokaal) shipping were collapsed into a single category of domestic shipping (III.9). ‘People’s shipping’, being either auxiliary sailing vessels of up to 850 cubic metres (m3; previously 500 m3 or 175 tonnes) or motor vessels of less than 100 m3

(35 tonnes) remained subject to less stringent requirements (IV.14).

11 Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia No. 17 Tahun 1988 tentang Penyelenggaraan dan Pengusahaan Angkutan Laut [PP 17/1988 on the Organisation and Operation of Sea Transport], 21 November.

cbieDec08b.indb 388

cbieDec08b.indb 388 31/10/08 4:53:02 PM31/10/08 4:53:02 PM

The impact of PP 17/1988 was swift and dramatic. It was felt most immediately in the offi ce of the DG of Sea Communications, which suddenly became very

quiet. When company directors no longer had to pay court to the regulators, even the car-park attendants experienced a substantial loss of income (Djunaedi Hadi-sumarto, interview, May 2007). Shipping companies were now free to purchase or charter the ships that best suited their business and proceeded to do so, while organising their operations in the most commercially profi table way. Well-run

Indonesian shipping companies now had scope to expand—some into container shipping, some into bulk shipping—and become substantial players, not only in domestic shipping but also regionally. Existing container operators Samudera Indonesia and Meratus were joined by newcomers Tempuran Emas, Salam Pacifi c

Indonesia and Tanto Lines in developing national container shipping networks, while the fi rst two fi rms diversifi ed into regional networks. Whereas in the 1970s

the largest inter-island fl eet was about 12 ships (Dick 1987), as of mid-2007

Mera-tus and Tempuran Emas both operated around 20–30 ships.12 Berlian Laju Tanker

was spectacularly successful in building up a fl eet of oil, chemical and gas tankers

which, as of mid-2008, stood at 84 ships of 2.0 million tonnes capacity.13

The deregulation of the mid-1980s therefore achieved its objectives. The cost of shipping from Indonesian ports and between Indonesian ports fell substantially, to the benefi t of trade and national integration. Well-run shipping companies

now had opportunities to expand, and did so beyond the wildest imagining of anyone at that time. New entrants came into the industry and also did well. Yet many existing fi rms struggled to survive in an internationally competitive

envi-ronment. Good connections with government offi cials were no longer enough to

secure a profi table business. The Asian crisis of 1997–98 was a further blow and

gave credence to those who argued that deregulation had crippled the Indonesian shipping industry. Vocal critics pointed out that by the mid-2000s Indonesian-fl ag

ships carried less than 5% of foreign trade and not much above 50% of domestic shipments.14 This was alleged to be causing a massive drain of foreign exchange,

estimated at $15 billion per annum (Wibawa 2006b). This nationalist argument took no account of economic and commercial realities, but it fell on the usual fertile ground. Amid the political turmoil and in the absence of any organised defence by the economic ministers, the stage was set for policy to be reversed.

RE-REGULATION

In October 1999, during the last weeks of the presidency of B.J. Habibie, the dereg-ulated policy regime was overturned by PP 82/1999, which revoked PP 17/1988 and rendered Inpres 4/1985 all but inoperative.15 The new regulation neatly

12 PT Meratus Line, <http://www.meratusline.com>; Temas Line, <http://www.temasline. com/index.php?act=home>; accessed 21 July 2008.

13 Berlian Laju Tanker Tbk, <http://www.blt.com.id/index.jsp>, accessed 21 July 2008. 14 ‘MoU signed to keep domestic shipping industry above water’, Jakarta Post, 29/3/2006.

15 Inpres 4/1985 was effective because of the authority of President Soeharto; its weakness was that it was not a legislative instrument but merely a presidential directive.

cbieDec08b.indb 389

cbieDec08b.indb 389 31/10/08 4:53:02 PM31/10/08 4:53:02 PM

reversed a previous policy defeat suffered by the two elder Habibie brothers, B.J. and Fanny. In the 1980s, when B.J. Habibie was still Minister for Research and Technology, his younger brother Fanny Habibie had become Director General of Sea Communications. B.J. Habibie identifi ed ship-building as one of his

strate-gic, high-tech industries and with his brother arranged it that ships older than 25 years should be scrapped and replaced by new ships built in Indonesian yards— pre-eminently that of PT PAL in Surabaya—which came under the control of the Ministry for Research and Technology (Dick 1987: ch. 9). Although the minister sought to justify this policy on grounds of safety, it was in fact completely arbi-trary. Ships older than 25 years with thick marine plate and good maintenance could be in much better condition than newer ships built with thinner mild steel. The Minister of Transport, Air Marshal Roesmin Noerjadin, was most unhappy about the decision, but Minister Habibie had already secured President Soeharto’s assent and so it became an order (Djunaedi, interview, May 2007).

Thus, by regulation, the shipping industry was directed to serve the interests not of trade, as befi tted the policy needs of the time, but of the ship-building

industry. Shippers thereby suffered a double penalty, being obliged to depend upon an inadequate and ineffi cient domestic shipping industry but also, through

more expensive vessels, having to subsidise the development of a ‘strategic’ domestic ship-building industry.

However, after the deregulation of domestic shipping with PP 17/1988, ship-ping companies could no longer be obliged to buy unsuitable and high-cost ships from domestic yards. This marked the fi rst big policy defeat for the Habibie

broth-ers at the hands of the technocrats. It was therefore no coincidence that in October 1999 it was none other than President Habibie who, near the end of his brief term in offi ce, signed the new PP 82/1999. It was within his power to restore the status quo ante, and he did so.

PP 82/1999 was in time overtaken by Inpres 5/2005, which re-introduced cabo-tage, and by a new shipping law (Law 17/2008). Nevertheless, the new law takes up much of the content of PP 82/1999, while conferring superior legal status. The following discussion refers to the relevant articles in the new 2008 law, with cross-reference to PP 82/1999 and Inpres 5/2005 where appropriate.

Licensing of shipping

The fi rst substantive issue is the specifi cation of shipping licence categories. Here

the new law maintains an awkward double classifi cation of maritime sectors.

Article 6 divides water transport into sea transport (angkutan laut), inland water-ways (sungai dan danau) and ferries (penyeberangan) connecting roads or railways between adjacent islands. Article 7 then sub-divides sea transport into interna-tional shipping, domestic shipping, non-common carriers or ancillary shipping (khusus) and people’s shipping (rakyat), the latter using prahu or ‘traditional’ ves-sels. This somewhat simplifi es PP 82/1999, which had retained a residual

cat-egory of restricted or cross-border sea transport (lintas batas) as an echo of the category, inherited from the 1936 shipping law, of local (lokaal) shipping for ves-sels of less than 175 gross tonnes operating over a restricted radius under conces-sional requirements of manning and safety (Dick 1987).

Articles 8–30 elaborate the content of each licence category, with some

simpli-fi cation of licence requirements. The requirements for international sea (formerly

cbieDec08b.indb 390

cbieDec08b.indb 390 31/10/08 4:53:03 PM31/10/08 4:53:03 PM

ocean, or samudera) transport companies are no longer prescriptive. Formerly it was specifi ed, rather needlessly, that such fi rms must operate at least one ship of

a minimum size of 5,000 tonnes under the Indonesian fl ag (PP 82/1999: II.2.6–10).

Now there are just standard requirements that ships in this category serve ports open to international shipping and that foreign-fl ag ships have a local agent.

Deep-sea shipping companies may be in the form of joint ventures with foreign partners, provided they operate at least one vessel of 5,000 gross tonnes under the Indonesian fl ag and with an Indonesian crew (29.2).

The requirements for domestic sea transport have also been further

simpli-fi ed. Under PP 82/1999, domestic sea transport (II.1.2–4) combined what used

to be separate licences for inter-island (nusantara) and offshore (lepas pantai) tug and barge operations. Now it is suffi cient that a domestic shipping fi rm

own at least one ship of more than 175 gross tonnes under the Indonesian fl ag

(article 29).

In Indonesia the distinction between international and domestic shipping is not clear-cut because of the proximity of Singapore and Malaysian ports. It is often effi cient for ships on inter-island routes to ship cargo to or from Singapore on one

leg of the journey rather than sail in ballast. Containerisation and the use of feeder shipping have made this option even more viable. If the aim of policy were to reduce the costs of shipping rather than to protect national-fl ag ship- owners, such

integration would be encouraged.

Ancillary shipping companies are licensed to serve only the vertically inte-grated shipping needs of their own business group (article 13; II.1.2–5). Typically this involves the bulk carriage of raw materials such as crude oil or coal, or proc-essed goods such as refi ned oil products, vegetable oils, chemicals or cement.

However, if the minister determines that there is a shortage of necessary shipping capacity, he or she may issue permission for these companies to serve third parties (article 13.4–5).

People’s shipping is defi ned broadly as ’a people’s enterprise (usaha masyarakat)

with traditional features‘ (article 15.1). The category used to apply only to small unpowered sailing craft (prahu) which, falling outside the main shipping regula-tions, could sail on an annual pass (jaarpas) issued by any local authority, and with no seaworthiness or safety requirements beyond the voluntary self-preservation of the crew. After the mid-1970s, as sailing prahu began to be fi tted with engines,

the distinction between ‘people’s shipping’ and small motorised ‘local shipping’ became blurred. Their consolidation in PP 82/1999 (article II.3.12.2) was a sensible step. The new law (article 1.5) likewise specifi es ‘sailing vessels, auxiliary sailing

vessels and motor vessels of a certain size [i.e. less than 175 gross tonnes]’ as all falling within the category of people’s shipping.

Articles 18–23 regulate the licensing of inland waterways transportation and ferries. These two categories are oddities in that, as ‘land bridges’, they formally come under the authority of the DG of Land Communications in ill-defi ned

rela-tionship to the DG of Highways, but with the DG of Sea Communications being responsible for the licensing of the vessels.

Article 24 addresses what has been known since 1974 as pioneer shipping (pelayaran perintis) (Dick 1987). The new law contextualises this as ‘sea transport for backward or remote areas’. Its primary purpose is to provide essential serv-ices that would not be viable on a commercial basis with suffi cient frequency,

cbieDec08b.indb 391

cbieDec08b.indb 391 31/10/08 4:53:03 PM31/10/08 4:53:03 PM

reliability or safety. In colonial times, such services in areas beyond the wide reach of the KPM were provided by the Gouvernments Marine (literally ‘Gov-ernment Navy’), which was something like the US Coastguard. While its pri-mary purpose was the maintenance of navigation aids, a large fl eet of ‘white

ships’ (kapal putih) also maintained communications and administrative serv-ices in remote districts such as the islands along the west coast of Sumatra, the Anambas–Natuna Islands, Nusa Tenggara, Maluku and what was then Dutch New Guinea. Passengers and cargo were carried on an incidental basis, along with mail. Most of these ships were lost during the Japanese occupation. After independence the government re-equipped what became the Directorate of Navigation with a fi ne fl eet of coastguard, lighthouse and general-purpose

ships. Through lack of maintenance, by the beginning of the New Order in the mid-1960s few of these ships were still in commission. In 1974 pioneer services were revived under government subsidy in remote districts, and became much sought after by provincial governments as a means of improving communica-tions on central government account. The problem was the lack of incentives for effi cient operation. The 2008 law specifi es that shipping to backward and

remote areas should be carried out by government, but qualifi es this by allowing

that the task may be contracted out long-term to national shipping fi rms under

government subsidy and subject to annual review. This could perhaps become a framework for a more rigorous community service obligation approach, but such a development does not seem to be imminent.

Articles 27–30 of the 2008 law set out the operating requirements for shipping licences. Here there are two signifi cant variations from PP 82/1999. First, in

rec-ognition of regional autonomy since 2001, the authority for issuing licences for people’s shipping, inland waterways and ferries has been delegated where appro-priate to provincial and local governments. Secondly, for international and domes-tic shipping fi rms there has been a marked simplifi cation. Owners are no longer

required to hold both a business licence (izin usaha) and an operating licence for the ships. The basic requirements are now simply that a fi rm be a legal entity

and own an Indonesian-fl ag vessel of at least 175 gross tonnes. Formerly, under

PP 82/1999 (part III), a sea transport company had to be legally registered for that purpose and to hold a valid business licence, which in turn required the fi rm to

provide the minister with details of incorporation, proof of ownership of a ship larger than 175 tonnes, employment of suitably qualifi ed staff, proof of company

domicile and a tax fi le number. Having received a business licence, a company

then incurred obligations to meet its licence requirements: commence activities within six months, observe all relevant laws and regulations, provide facilities for carrying mail, and report its activities every year, along with any changes of ownership, domicile or ships. Should these requirements be breached, the min-ister was empowered to cancel the operating licence, including on grounds of national security or endangering public safety or the environment. It remains to be seen, however, whether the apparent simplifi cation will be carried forward in

the implementing regulations.

For inland waterways transport and ferries, however, a secondary licence is still required (article 28). Firms serving inland waterways must also obtain a route permit (izin trayek), while ferry operators must obtain a ship operating approval (persetujuan pengoperasian kapal).

cbieDec08b.indb 392

cbieDec08b.indb 392 31/10/08 4:53:03 PM31/10/08 4:53:03 PM

Licensing of routes

Whereas the licensing of shipping companies is now fairly permissive, the regu-lation of domestic shipping routes intrudes into commercial operations. Articles 9–10 of the 2008 law (and part V of PP 82/1999) distinguish between liner ship-ping, which involves scheduled services on fi xed routes (trayek tetap dan teratur),

and tramp shipping. The law requires that companies providing inter-island liner services be organised into a system-wide network with respect to the distribution of economic activity, regional development, spatial plans, inter- and intra-modal integration, and the realisation of national unity. This network is to be deter-mined jointly by the central government, regional governments and INSA, taking account of submissions by the Association of Sea Transport Users. It is then to be promulgated by the minister. The allocation of ships to the liner network is for shipping companies to determine, subject to a mélange of considerations: vessels to be seaworthy, fl ying the national fl ag and crewed by Indonesian nationals; the

potential demand for and supply of shipping space (PP 82/1999 also specifi ed

reasonable load factors); the adequacy of port facilities; and the appropriate type and size of vessels. Their operation (whatever that means) is to be reported to the government. The one signifi cant respect in which the 2008 law is here more liberal

than PP 82/1999 is that there is no longer a requirement that shipping companies commit their ships to routes for at least six months and that the minister evaluate and identify the need for capacity changes across all routes every six months.

This regulation revives elements of the Regular Liner System that was fi rst

intro-duced in 1964 by the then Department of Shipping and enforced more systemati-cally after 1969 by the Directorate of Traffi c in the DG of Sea Communications (Dick

1987). Then, all inter-island ships were allocated to routes with set ports of call and specifi ed frequencies. The laudable intention was to ensure that all ports in the

archipelago received some minimum level of service, regardless of profi tability.

Hence ‘fat’ routes were balanced by ‘thin’ routes, and busy ports by minor ports. On paper it looked marvellous, a triumph of central planning over a disorderly market—the KPM system but with the Directorate General co ordinating in lieu of a private monopolist. In reality, companies did more or less as they liked, and paid the Directorate of Operations—the ‘wettest’ directorate in a ‘wet’ Directorate Gen-eral—to turn a blind eye. This costly farce was terminated by PP 17/1988, which allowed shipping companies to make their own commercial decisions.

While the goal of developing a sound national liner system is commendable, it may be asked on what basis the DG of Sea Communications (on behalf of the minister) is able to organise a centrally planned system better than a market in which private companies risk their own capital and make commercial decisions. This regulatory role is given even more prominence in the 2008 law (part II, articles 9–10, as compared with part V of PP 82/1999), even ahead of business licensing. The reality, of course, is that the Directorate General does not have even a fraction of the necessary information and expertise to carry out the task. In theory this will be overcome by the 2008 law’s part XV (PP 82/1999, part XI), which mandates a shipping information system to be managed by the central government in conjunction with regional governments. Every shipping com-pany is required to submit detailed operational data on its fl eet, cargoes, routes

and other services to the relevant central or regional government for compila-tion and disseminacompila-tion. Equivalent obligacompila-tions are imposed in the fi elds of port

cbieDec08b.indb 393

cbieDec08b.indb 393 31/10/08 4:53:04 PM31/10/08 4:53:04 PM

services, marine safety, the maritime environment and human resources. If they were nationally comprehensive, some at least of these data would be useful, but the experience of recent years and the lack of incentive for compliance, whether by private fi rms, government agencies or regional governments, suggest that

the whole apparatus is likely to be redundant, serving only to occupy bureau-cratic resources and generate additional income for bureaucrats as a de facto tax on the shipping industry.

Tariff setting

Part VIII (articles 35–38) of Law 17/2008 gives the government powers to set pas-senger fares and, indirectly, freight rates. In a modest liberalisation from PP 82/1999 (part VI), set fares now apply only to economy-class passengers. Previously, fares were to be set on a formula that specifi ed a fi xed base rate and a variable distance

factor, plus a margin for non-economy passengers; the omniscient minister would also determine the allocation of sitting and sleeping capacity between economy and non-economy passengers. In practice all this mainly applied to Pelni, as the predominant inter-island passenger carrier. Pelni being a state enterprise, there was no good reason other than precedent why the tariffs should be set by the minister rather than by Pelni itself, which thereby lost control over its revenues and fi nancial results.

Freight rates for inter-island goods movement are still allowed to be agreed commercially between the shipping company and shipper, thereby retaining an element of the 1980s deregulation. However, the new law stipulates that such negotiations must be in accordance with the tariff types, structure and categories specifi ed by the government. Hence, although an offi cial freight tariff is no longer

binding, it remains the framework for tariff-setting. In reality, of course, the gov-ernment cannot oversee the multiplicity of commercial rates. Where this article is likely to ‘bite’ is in the enforcement of artifi cially low rates for ‘essential’

com-modities—a subsidy unlikely to facilitate their smooth distribution.

Cabotage

Cabotage is a protectionist policy that requires domestic sea cargo to be carried by national-fl ag ships. It is applied by many countries as an aspect of sovereignty

and is recognised by international law. In the case of Indonesia it was a tenet of economic nationalism, and it was therefore particularly galling that until 1957 a substantial share of inter-island cargo was still carried by the Dutch-fl ag KPM

(Dick 1987). Nevertheless, even after the KPM had been expelled, the gap was

fi lled by chartered foreign-fl ag tonnage. After 1967, foreign-fl ag ships continued

to sail in inter-island trade under various hire-purchase arrangements. Not until the mid-1970s was cabotage at last enforced. It then applied strictly for barely a decade before the deregulation of the mid- to late 1980s released shippers from the stranglehold of a high-cost national-fl ag fl eet.

The principle of cabotage was restated by PP 82/1999 and its enforcement man-dated by Inpres 5/2005:

1.a. Domestic inter-island cargo must be carried by Indonesian-fl ag ships operated by

Indonesian companies as soon as possible after this Instruction comes into effect.

Inpres No. 5/2005 also applied a cargo reservation policy to government goods:

cbieDec08b.indb 394

cbieDec08b.indb 394 31/10/08 4:53:04 PM31/10/08 4:53:04 PM

1.b. Imports that are sourced or whose carriage is fi nanced through the budgets of

the national or regional governments must use ships that are operated by national shipping companies, with strict regard to the laws governing the provision of offi cial

goods and services.

The enforcement of cabotage was backed by a series of other regulatory meas-ures to support the development of the national-fl ag fl eet. Section 1.2 dealt in

vague terms with taxation, fi nance and insurance. Section 1.3 on communications

sought to underpin restored powers over the routing of inter-island liner ship-ping with various incentives for such shipship-ping. Other articles called for revision of procedures for the transfer of ships to the Indonesian fl ag; for accelerated ratifi

-cation of the international conventions on Maritime Liens and Mortgages and the Arrest of Ships; for support for people’s shipping; and for accelerated formation of a Sea Freight Information Exchange.

The rest of Inpres 5/2005 related to other ministries impinging upon the ship-ping industry. Section 1.5 (Energy and Mineral Resources) instructed the Minister for Mining to ensure that adequate bunkers were available for Indonesian-fl ag

inter-island ships; section 1.6 (Education and Training) instructed regional gov-ernments and the private sector to develop education and training centres to inter national standard, and to promote collaboration between these centres and service providers (presumably employers) to produce seafarers of international standard. These were admirable objectives, but there was no mechanism to achieve them.

A presidential instruction is not a legislative document but a directive from the president as to what is to be done, typically across several ministries. Working within the framework of existing laws, it does not go through parliament but sets out priorities and goals for the government. Essentially it is a coordinating docu-ment that gives a policy direction more force than would a similar docudocu-ment com-ing from ministerial level or even from a coordinatcom-ing minister, notwithstandcom-ing that the economic coordinating minister is instructed to coordinate the implemen-tation of the instruction and to report back to the president. The 2008 law was therefore necessary to give full legislative force to the new regulatory impulse. Its wording is unambiguous in both the positive and the negative:

Domestic sea transport is to be carried out by national shipping companies using Indonesian-fl ag ships crewed by Indonesian nationals (article 8.1)

Foreign ships are prohibited from carrying passengers or cargo between the islands or ports of Indonesian waters (article 8.2).

The impact of cabotage is discussed further below.

Ports and port services

The 2008 law (part VII) deals at length with ports and may be a modest improve-ment over PP 82/1999. Inpres 5/2005 (1.3.b) had dealt only very generally with ports by setting out broad policy guidelines: to review the running of ports to give more effective and effi cient service; to review the ports open to foreign trade;

to develop port infrastructure; gradually to separate the functions of regulator and operator and to allow competition between terminals and between ports; to abolish charges for non-public services; and to improve the overall level of public service. Perhaps the most signifi cant point was the recognition, for the fi rst time,

cbieDec08b.indb 395

cbieDec08b.indb 395 31/10/08 4:53:04 PM31/10/08 4:53:04 PM

of inter-port competition—a reality in a more decentralised Indonesia and almost certainly to the benefi t of shippers.

Part VII’s 48 articles are too extensive to permit detailed exposition here and it is suffi cient to focus on the key issues. First, the new law specifi es a 20-year

National Port Masterplan as the basis for port location, operation and develop-ment. This in turn will involve specifi cation, port by port, of both working areas

(daerah lingkungan kerja) and port development areas (daerah lingkungan kepentin-gan), to be determined after recommendation by the relevant governor or mayor. The section on port management elaborates the key distinction made in Inpres 5/2005 between regulation and management. For one or more commercial ports, port authorities (otoritas pelabuhan) will be formed as civil service units under ministerial authority but, through coordination with local government, will have delegated powers to issue concessions to, and regulate the activities of, port oper-ators (badan usaha pelabuhan). For non-commercial ports, management units (unit penyelenggara pelabuhan) will be constituted with somewhat more extensive pow-ers. What is involved here is application of a ‘landlord’ model of port manage-ment. Port authorities will be empowered to organise land use, supervise use of the working and development areas, direct the movement of vessels and set stand-ards of operational performance (article 84). After a three-year transition period (article 344) this will involve new competition for, and perhaps the demise of, the four regional port corporations (Pelabuhan Indonesia, or Pelindo) that since 1983 have been a monopolistic and bureaucratic obstacle to the development of a more effi cient port system in Indonesia.

Another potentially important innovation concerns the role of special (khusus) port terminals, which in effect are private ports mainly for specialised handling. As in previous legislation, the 2008 law specifi es that such terminals

may handle only ancillary and not common cargo, except by ministerial dispen-sation. However, the law also specifi es that such terminals may be converted to

public ports. This provision has the potential to enhance inter- and intra-port competition (Ray 2008), though companies may be reluctant to surrender owner-ship of their assets to the new port authorities and submit to an as yet uncertain regulatory regime.

The new legislation appears less satisfactory when it comes to port services. Article 31 sets out the types and licensing requirements for no fewer than 11 cat-egories (six under PP 82/1999) of ancillary services (usaha penunjang): stevedoring (bongkar–muat); freight forwarding (pengurusan transportasi); harbour lighterage; equipment leasing; cargo tallying; container depots; ship management; ship bro-king; ship manning agencies; vessel agencies; and ship repair and maintenance. Here also there has been a simplifi cation of the licensing process, but it seems that

each individual activity, albeit often closely associated with others, must still be separately licensed, though national shipping companies may engage in steve-doring and forwarding of their own cargo.

There also continues to be ambiguity in the setting of tariffs for port and mari-time services. As in the case of domestic shipping, tariffs are to be set by com-mercial negotiation but according to the type, structure and categories specifi ed

elsewhere by the minister (article 36). Port authorities must advise the minister on tariffs for port facilities and services under their control (article 83). Given that ports are to some extent natural monopolies, there is a case for regulatory

cbieDec08b.indb 396

cbieDec08b.indb 396 31/10/08 4:53:04 PM31/10/08 4:53:04 PM

oversight, but the role of government should be one of monitoring performance rather than becoming involved in the detail of tariff setting.

Thus the logic of door-to-door cargo movement in the age of containers and electronic data processing still fails to permeate the most recent legislation. Effi

-cient logistics requires close integration between land-based services and ship-ping. How companies choose to organise the various tasks should be an internal matter, not one for interference by the port authority or minister. Likewise, inte-gration between shipping, agencies and port services should be encouraged, not discouraged. The test should be a market, not a regulatory one. In practice, the number of fi rms and the amount of information required make it

impos-sible for the bureaucracy to monitor what is happening. Bureaucratic pedantry merely adds to the regulatory burden, both in compliance costs and in expo-sure to ‘squeeze’. Periodic screenings, like police raids, become just an excuse to raise unoffi cial revenue. In this regulatory maze, simplicity and clarity are not

the aims.

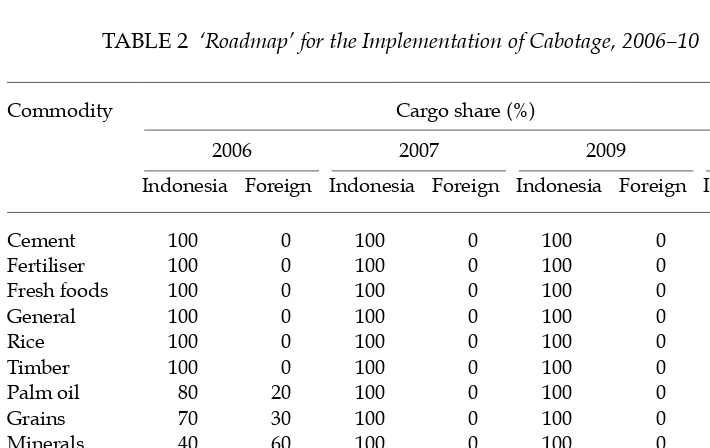

IMPACT Cabotage

Cabotage is being implemented in stages according to a ministerial ‘roadmap’ that will see all inter-island cargoes carried by Indonesian ships by 2010 (table 2). By the end of 2007 it was calculated that, over the three years since Inpres 5/2005 was issued, the number of Indonesian-fl ag ships had risen by 30%, while the

share of international cargo carried by them had increased from 3.5% to 5.9% and

TABLE 2 ‘Roadmap’ for the Implementation of Cabotage, 2006–10

Commodity Cargo share (%)

2006 2007 2009 2010

Indonesia Foreign Indonesia Foreign Indonesia Foreign Indonesia

Cement 100 0 100 0 100 0 100

Fertiliser 100 0 100 0 100 0 100

Fresh foods 100 0 100 0 100 0 100

General 100 0 100 0 100 0 100

Rice 100 0 100 0 100 0 100

Timber 100 0 100 0 100 0 100

Palm oil 80 20 100 0 100 0 100

Grains 70 30 100 0 100 0 100

Minerals 40 60 100 0 100 0 100

Other crops 70 30 80 20 100 0 100

Other liquids 40 60 65 35 100 0 100

Coal 60 40 75 25 95 5 100

Oil 40 60 60 40 90 10 100

Source: Rapat Pokja Perhubungan (transport working group meeting), 11/8/2005, in Wibawa (2006a).

cbieDec08b.indb 397

cbieDec08b.indb 397 31/10/08 4:53:05 PM31/10/08 4:53:05 PM

that of inter-island cargo from 54% to 65%.16 Singularly lacking, however, are any

economic measures of the impact of cabotage on the cost of transport and on effi

-ciency. If the transfer of fl ag were costless, the short-term economic consequences

would be minimal. However if, as seems more likely, Indonesian-fl ag ships are

more expensive because of higher rates of tax and full exposure to Indonesian law and the domestic regulatory system, the burden will be passed on to ship-pers, and is likely to increase over time as higher costs are built into a protected industry.

The strongest reason for believing that cabotage will embed higher transport costs is that it again exposes Indonesian-fl ag shipping to the full force of

bureau-cratic regulation and legal uncertainty. Under the deregulated system, Indonesian ship-owners and shippers had ways to evade bureaucratic ‘squeeze’. Now they are locked in. It is surely no coincidence that cabotage and re-regulation were part of the same Inpres 5/2005 package. The triple authority of the DG of Sea Communications to license fi rms and capacity, to specify routing and to set

tar-iffs had already been re-introduced in PP 82/1999. It was now given renewed force and inter-departmental legitimacy. Matters that in PP 17/1988 had been rec-ognised as commercial decisions returned under Inpres 5/2005 to the ambit of government. In 2007 the Directorate General sought to end a prolonged freight rate war between domestic container operators by announcing a review of routes and schedules. Explaining that this would be done in conjunction with INSA, the director general pointed out that under PP 82/1999 and Inpres 5/2005 he had full powers to conduct such a review: ‘Before we had the basis of Inpres No. 5/2005, we would use PP No. 82/1999’ (Wibawa 2007). His action was strongly supported by a shipping manager, who was quoted as saying that the government as regula-tor should determine the volume of cargo on each route and the number of ships required. Thus an ordinary commercial issue that would normally be resolved by the market became an arena for regulatory intervention.

The reality is, of course, that the DG of Sea Transport and the Directorate of Traffi c, in particular, do not have the resources to monitor the routing and freight

rates of every ship. What they can do is interfere—make a nuisance of themselves from time to time in order to be paid off, rather like traffi c police. It is a subtle

form of protection racket at the proximate expense of ship-owners, but with the costs passed on to shippers and producers and, ultimately, to consumers through higher prices.

The inhibiting effect of cabotage on market pressures for better performance should also be taken into account. Within the shipping industry there is a wide range of performance, from companies that are near international best practice to others that would not survive without protection and rent-seeking. Protection benefi ts the good fi rms by giving them a higher margin of profi t and some

insula-tion from competiinsula-tion, thereby weakening market incentives for them to continue to improve their effi ciency in line with international trends. It benefi ts the bad fi rms by keeping them in business with weaker incentives for improved

ance. The protected market is therefore less effective in generating high perform-ance. Ineffi ciency tends to worsen over time.

16 ‘Indonesian ships increase domination of domestic cargo transport’, Asia Pulse, 18/7/2008.

cbieDec08b.indb 398

cbieDec08b.indb 398 31/10/08 4:53:05 PM31/10/08 4:53:05 PM

Any margin of ineffi ciency in inter-island shipping is equivalent to a tariff on

inter-island trade over and above the natural level of protection (Dick 1987).

Arti-fi cially high inter-island transport costs discourage trade and therefore

produc-tion in exactly the same way as does an internal revenue or protective tariff.17 This

was the rationale for the de facto abolition of cabotage and regulation under the trade reforms of the mid- to late 1980s.

Logistics

Global supply chains, in conjunction with the containerisation of international non-bulk cargoes, impose stringent requirements on the effi ciency of freight fl ows door-to-door. The three key parameters are cost, transit time and

reliabil-ity; under just-in-time inventory systems, transit time is now measured in hours rather than days. Not only Indonesian shipping but also Indonesian ports and road freight systems perform poorly by all three criteria. The Ministry of Com-munications has under its control all the main elements except customs: ship-ping, ports, roads and rail. What is lacking is any overall economic objective. The clear statement about an ‘integrated system of national communications’ embodied in PP 17/1988, along with commitment to the development of other sectors of the economy, was revoked by PP 82/1999 in favour of the vague state-ment that:

Apart from having a strategic role in the realisation of the Archipelago Vision, sea transport should support (memperkukuh) national defence and strengthen relations between countries in achieving national goals, and also serve as a means of develop-ing the national economy.

The economic purpose looks to have been added as an afterthought. This is

con-fi rmed by comparison with Law 21/1992 on Shipping, whose opening article

includes this formulation but without the additional phrase about the economy. The 2008 shipping law is not much of an improvement. The preamble states that shipping is

part of a national transportation system whose potential and role must be developed to realise a transport system that is effective and effi cient and can assist the

achieve-ment of a stable and dynamic national distribution network.

However, neither the preamble nor the following statement of objectives (II.2–3) gives any priority to economic goals over a collection of more amorphous aims, many relating to defence and security. Nor is there any guidance as to how eco-nomic goals are to be realised.

Nowhere in the most recent law, regulation or presidential instruction does the word ‘logistics’ appear, though the term ‘inter-modal integration’ is now used. It may be concluded that the concept of logistics has not yet entered the offi cial

mindset. If one may assess priorities in terms of the order in which they are set out, the mindset of the 2008 shipping law is defensive, with primary emphasis upon national defence and security. In other words, the nationalist impulse to prevent the intrusion of foreign-fl ag shipping and foreign service providers fl ows

logically from the formulation of the problem. Nor is there any recognition that

17 The same logic applies to offi cial and unoffi cial levies on inter-district trade.

cbieDec08b.indb 399

cbieDec08b.indb 399 31/10/08 4:53:05 PM31/10/08 4:53:05 PM

the provision of transport services even by domestic fi rms is now for the most

part a commercial enterprise subject to commercial considerations. Between the lines, one senses the old view that the means of transport should be owned and controlled by state enterprises as an instrument of government policy—with the qualifi cation that, if they are not owned and controlled by state enterprises, they

should at least be regulated to achieve national policy objectives.

The defi ciencies of Indonesia’s logistics system are now likely also to become

an obstacle to regional integration. In August 2007, ASEAN trade ministers signed a joint protocol for integration of the logistics sector (ASEAN 2007). Yet a concurrent study commissioned by the ASEAN Secretariat revealed that Indonesia has the worst logistics among the 10 member countries when assessed in terms of regulatory environment, foreign investment climate and adequacy of infrastructure (Souza et al. 2007). Thus either Indonesia sets the lowest common denominator or ASEAN integration must proceed with no more than its nominal participation.

Regulation is the root cause of multiple and related problems of logistics. First, ports are the main bottleneck in the sea transport system. Ships spend more than half their time in port—domestic shipping even longer than ocean-going—but because of lack of equipment and poor labour organisation barely a third of that time is productive (Ray and Blankfeld 2002; Ray 2008). Some main container terminals are now controlled by private operators, but the role of the four Pelindo corporations, both as owners of physical assets and as regulators, has yet to be sorted out, including their dual relationships with the DG of Sea Communications and the Ministry of State Enterprises. Poorly designed leasing contracts combined with monopoly, especially in Jakarta, have led to excessive charges.

Second, port services are still fragmented into multiple business licence catego-ries, without any recognition of logistics chains or of the impact of advances in information technology upon the handling of goods and the fl ow of

documenta-tion. Phased introduction of electronic documentation and a ‘single customs win-dow’ will make this all the more cumbersome. As can be seen in the experience of service providers and in lobbying over the draft maritime law,18 each separately

licensed fi rm and its business association fi ghts tooth and nail for its own turf

against all the logic of service integration, whether by national or international container-ship operators and freight forwarders. Indonesia ought to be encour-aging the involvement of foreign logistics fi rms as a means of promoting global

integration and technology transfer to local fi rms, not raising barriers to entry.

Indonesia’s export development needs the quality of service guarantees that glo-bal fi rms provide, whether through wholly owned subsidiaries, joint ventures,

alliances or sub-contracting.

Third, in the main cities, especially Jakarta, the cost of traffi c congestion can

hardly be over-emphasised. My inquiries suggest that trucks from the industrial estates around Jakarta spend so much time in transit and waiting that they make only one delivery a day, whereas around-the-clock working should allow two or even three deliveries. In consequence, there are two or three times as many trucks on the roads as there should be and the cost is two or three times what it ought

18 ‘Draf RUU Pelayaran kembali protes [Draft Shipping Law brings more protests]’, Bisnis Indonesia, 14/5/2007.

cbieDec08b.indb 400

cbieDec08b.indb 400 31/10/08 4:53:06 PM31/10/08 4:53:06 PM

to be. There is no coordination between Sea Communications, Land Communica-tions, Highways, city administrations and industrial estates to tackle this mas-sive ineffi ciency, and no sense of urgency about doing so. Congestion charges, as

proposed in the election platform of the new Governor of Jakarta, H. Fauzi Bowo, would be a breakthrough (Fauzi Bowo 2007: 15).

Ironically, one need fl y only one and a half hours from Jakarta or take a

half-hour ferry ride from Batam to see the most effi cient logistics centre in the world,

namely Singapore. The striking contrast between the maritime and fi nancial

regimes of Indonesia and Singapore is paralleled in logistics. Singapore is the largest container port in the world, and is a triumph not only of shipping but also of port layout and organisation, multi-modal integration and automated docu-mentation. Best practice can be studied at close quarters and applied to Indonesia if there is a will to do so.

Marine safety

Public safety has been recognised as a clear case of market failure in the ship-ping industry ever since the mid-1870s, when the British government introduced hull markings (load-lines) to prevent over-loading. Self-regulation does not work, because companies under-estimate marine risks and set a lower value on human life than is publicly acceptable. International standards are now agreed through the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention. Thus in well-governed countries, governments set, monitor and enforce strict standards for maritime, airline and road safety. In Indonesia, however, market failure is compounded, rather than corrected, by government failure. The necessary laws and regulations are in place. As reiterated in the 2008 law (parts VIII and IX), the government has the power to issue fi nes and cancel

licences for breaches of maritime safety. Yet monitoring is minimal and enforce-ment almost non-existent. Both private and state companies routinely fl out safety

standards and buy their way out of inspections, paying for false certifi cates of

compliance. The state-owned Indonesian Classifi cation Bureau (Biro Klasifi kasi

Indonesia, BKI), the sole national authority empowered to issue seaworthiness certifi cates, has long had a notorious international reputation, to which the DG of

Sea Communications has remained fairly indifferent.

These matters came to public attention in early 2007 because of the heavy loss of life in two maritime disasters—the capsize of the ‘ro–ro’ (roll on–roll off) ferry

Nusantara Senopati during bad weather in the Java Sea, and the fi re aboard the

ro–ro ferry Levina en route from Jakarta to Bangka (Irfan et al. 2007; Media, Fir-mansyah and Rusydi 2007). Both disasters brought to light problems of overload-ing, poor safety equipment and sloppy procedures, which were not specifi c to

these two ill-fated vessels but common to ships under the Indonesian fl

ag—espe-cially those not sailing to foreign ports that require mandatory inspections. In April 2007 an investigative television team compiled a short report about safety standards on ferries crossing the Sunda Strait from Merak to Bakahuni. Safety equipment was found to be inadequate and poorly maintained, safety drills non-existent, and vehicles secured by nothing more than wooden chocks, so that any collision was likely to lead to immediate capsize. The only reason more disasters do not occur, as they do in the Philippines, for example, is that Indonesian waters are calmer and seldom troubled by typhoons.

cbieDec08b.indb 401

cbieDec08b.indb 401 31/10/08 4:53:06 PM31/10/08 4:53:06 PM

The government’s response to the public outcry over these two disasters was ineffectual. In May 2007 the Minister of Communications was appointed head of the State Secretariat—a move that could well be viewed as a promotion. The unfortunate captain of the Levina later had his certifi cate suspended. No sanctions

were imposed on any ship-owner, nor was there any crackdown on inadequate safety equipment and procedures.19 Even INSA became concerned, because

insur-ers no longer trusted certifi cates of seaworthiness issued by BKI.20 Argument

con-tinued over the appropriate extent of autonomy for BKI, with the former minister, Hatta Radjasa, pushing for the state-owned enterprise to be brought back under direct bureaucratic control (Sijabat and Santosa 2007). On the one issue on which it clearly should have intervened and was under public pressure to do so, the bureaucracy was simply paralysed.

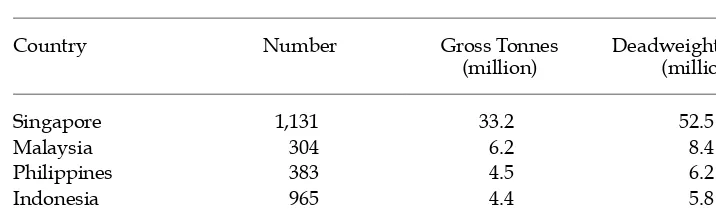

Development of the shipping industry

As expressed in PP 17/1988, the objective that shipping should serve the interests of domestic and foreign trade was a statement about the proper role of shipping, not a case against development of the shipping industry. Indonesia has most of the key resources to be a leading maritime nation: it is a large cargo generator, has abundant cheap labour to crew ships, and possesses a core of entrepreneurs and managers with experience in the shipping industry. Yet in the almost 60 years since the transfer of effective independent sovereignty in 1949, progress has been disappointing. The fl eet of the city-state of Singapore dwarfs that of Indonesia,

which ranks below Malaysia’s fl eet and close to that of the Philippines in terms of

tonnage (table 3).

The slow development of Indonesia’s shipping industry is not due to any lack of entrepreneurship. The best proof of this is that many ship-owners who set up their businesses in Singapore had their origins in Indonesia but migrated after independence to become Singaporean citizens. Others who remain

Indo-19 The prosecutions that followed upon the heavy loss of life from the sinking of Pelni’s passenger ship Tampomas II in 1981 remain exceptional (Dick 1987: 150–1).

20 ‘Perbaikan kapal belum penuhi standard [Ship repair not yet up to standard]’, Bisnis Indonesia, 9/5/2008.

TABLE 3 ASEAN Shipping Fleets, 2007a

Country Number Gross Tonnes (million)

Deadweight Tonnes (million)

Singapore 1,131 33.2 52.5

Malaysia 304 6.2 8.4

Philippines 383 4.5 6.2

Indonesia 965 4.4 5.8

Thailand 405 2.6 4.0

a Vessels over 1,000 gross tonnes only.

Source: CIA (2008).

cbieDec08b.indb 402

cbieDec08b.indb 402 31/10/08 4:53:06 PM31/10/08 4:53:06 PM