www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Development of stereotypies and polydipsia in wild

ž

/

caught bank voles Clethrionomys glareolus and

their laboratory-bred offspring.

Is polydipsia a symptom of diabetes mellitus?

B. Schoenecker

), K.E. Heller, T. Freimanis

Zoological Institute, UniÕersity of Copenhagen, TagensÕej 16, DK-2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark

Accepted 31 January 2000

Abstract

Ž The development of stereotypies and polydipsia was studied in wild caught bank voles P:

. Ž .

ns92 and their laboratory-bred offspring F1: ns248 . All animals were kept isolated in barren cages in the laboratory. In the P generation, no individuals developed stereotypies, but 22%

Ž .

developed polydipsia )21 mlrday water intake against normally 10 mlrday . Polydipsia was

Ž . Ž .

more frequent among males 34% than females 13% . In F1, 30% developed locomotor

stereotypies alone, 21% showed polydipsia alone, and, additionally, 7% developed both

stereotyp-Ž .

ies and polydipsia. Fewer males than females developed stereotypies 23% vs. 38% , whereas

Ž .

polydipsia was more frequent in males than in females 30% vs. 11% . The occurrence and distribution of polydipsia among sexes were the same in F1 and P. The distribution of different

Ž .

types of stereotypies in stereotyping voles were backward somersaulting BS, 80% , high-speed

Ž . Ž .

jumping JUMP, 29% , pacing following a fixed route PF, 12% and windscreen wiper

Ž . Ž .

movement WIN, 5% . Some individuals 10% showed two or more different types of stereotyp-ies. The average age for developing stereotypies was 96 days while polydipsia was registered at the age of 63 days in both sexes. Voles showing both polydipsia and stereotypies developed

Ž .

polydipsia later 79 days than polydipsic voles not showing stereotypies. This difference was especially pronounced in stereotyping females in which the occurrence of polydipsia was postponed to the age of 114 days. Polydipsic voles were tested positive for glucosuria indicating

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q45-3532-1302; fax:q45-3532-1299.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] B. Schoenecker .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

that polydipsia could be a symptom of diabetes mellitus. It is suggested that the development of stereotypies and polydipsia among bank voles in the laboratory are the results of frustration and prolonged stress. Stereotypies seem to depend on frustrative experiences early in life, while polydipsia may be related to diabetes mellitus caused by the experience of prolonged stress. Moreover, circumstances related to the development of stereotypies may be adaptive by reducing the risks of prolonged stress, including the development of fatal polydipsia. q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Bank voles; Stereotypies; Polydipsia; Diabetes mellitus; Adaptive value

1. Introduction

Stereotypies are the collective term for a group of phenotypic different behaviours that share the following three characteristics: Morphologically identical movements,

¨

Ž .

which are repeated regularly and have no obvious function Odberg, 1978 . Stereotypies occur in many different species kept in captivity or intensive husbandry and farms ŽMason, 1991 . Stressors like barren environments Sørensen, 1987 , scheduled and. Ž .

Ž .

restricted feeding Falk, 1969, 1971; Bildsøe et al., 1991; Lawrence and Terlouw, 1993 ,

Ž .

social deprivation Sahakian et al., 1975; Broom, 1983; Arellano et al., 1992 , frustration

¨

¨

ŽFeldman, 1978; Odberg, 1978; Rushen, 1985; Odberg, 1987; boredom Wemelsfelder,. Ž

. Ž .

1993 and tethering Cronin et al., 1985a are generally associated with stereotypies. The eliciting circumstances, the ontogeny, and the context in which stereotypies are

per-Ž .

formed are very heterogenic Cronin et al., 1985b; Mason, 1991, 1993 . Laboratory-bred, but not wild caught, bank voles housed in barren cages develop spontaneous locomotor

¨

Ž .

stereotypies with a high frequency Odberg, 1986 . The voles perform easily recognis-Ž .

able stereotypies such as backward somersaulting BS , jumping, pacing following a

Ž . Ž . Ž

fixed route PF and windscreen wiper movement WIN Sørensen and Randrup, 1986;

¨

.Odberg, 1986; Sørensen, 1987; Cooper and Nicol, 1991, 1996 . Increasing the size and complexity of the housing conditions reduces the incidence of stereotypies in bank voles

¨

ŽOdberg, 1987 , but old voles show stronger perseverance of stereotypies than younger.

Ž .

voles after environmental enrichment Cooper and Nicol, 1996 . Moreover, there seems to be no difference in mortality or fecundity between laboratory-bred and wild caught

Ž .

voles Cooper and Nicol, 1996 .

Both wild caught and captivity-bred bank voles have been reported to develop

Ž .

excessive drinking or polydipsia in the laboratory Sørensen and Randrup, 1986 , but the causes of this abnormality, its ontogeny and its relation to the occurrence of locomotor stereotypies is uncertain. Likewise, there is no detailed information on possible sex differences in the development of stereotypy and polydipsia, just as we know only a little about mortality especially in polydipsic voles.

The present study aimed at examining the development of stereotypic behaviour and polydipsia in wild caught bank voles and their laboratory-bred offspring when kept isolated under barren housing conditions. Attention was specifically paid to associations with age and sex. Moreover, the possibility that polydipsia in bank voles could be a

Ž .

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Housing and breeding

Ž . Ž .

Wild bank voles 38 males and 54 females representing the parental generation P were caught in August and September on the island Zealand, Denmark, using traditional live traps. The animals were transferred to small barren cages of transparent plastic Ž13.5=16.0=22.5 cm and kept physically isolated in the laboratory under 12 h light.

Ž .

conditions 0800–2000 h . The cages were supplied with a woodcutting bed, and food Žstandard rat chow and water were available ad libitum. Cage cleaning was performed. every second week or when necessary. A portion of a grain mixture was given when the cages were cleaned.

After an initial observation period of at least 5-week duration, single mating pairs

Ž .

were transferred to larger enriched cages 14.5=21.5=37.5 cm supplied with a Ž .

woodcutting bed, toilet paper, and paper rolls. The resultant offspring F1 consisted of 138 males and 110 females in 52 different litters born from November to May. F1 individuals were weaned between the ages of 25 and 53 days and kept physically isolated for 180 days.

2.2. ObserÕations and classification

One-zero sampling for 3–4 h everyday during the isolation period paid attention to stereotypic behaviour. When stereotypies were recognisable, the age and sex of the voles were noted along with the type of stereotypy performed. Mean daily water consumption was calculated for all animals. No attempts were made to estimate the amount of water not ingested.

Ž .

Voles were classified as stereotypers S if stereotypic behaviour were noted in bouts of at least five repetitions during the daily observation periods. These bouts, separated by small intervals, could continue for hours. The term S covered BS, high-speed

Ž . Ž

jumping JUMP , PF and WINs as previously defined Sørensen, 1987; Sørensen and

¨

.Randrup, 1986; Odberg, 1986; Cooper and Nicol, 1991, 1996 . Voles were classified as Ž .

polydipsic PD if their average daily water intake at least for a continuous month

Ž .

exceeded 21 ml compared with 10 mlrday for average consumption . Voles showing Ž .

both PD and S were classified as polydipsic stereotypers PDS . Voles showing neither Ž .

PD nor S were classified as wildtype W .

Twenty polydipsic and 20 non-polydipsic voles were randomly selected and tested for

Ž w

glucosuria as a possible indication of diabetes mellitus TESTAPE , Eli Lilly and .

Company .

2.3. Statistical analyses

Spearman rank correlation tests were used to estimate effects of isolation age on the age of development of stereotypies and polydipsia. Intersex differences in stereotypy fre-quencies and water consumption were tested with chi-square tests using Yates continuity correction factor. The same test was used on data from polydipsic and non-polydipsic voles with respect to glucosuria. The chosen significance level was 0.05 and the tests were two-tailed. Corrections for ties were performed if necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Stereotypies

Ž . Ž

Table 1 illustrates the proportion % of animals in the four classifications W, S, PD .

and PDS in each of the two generations.

No individuals in the P generation developed stereotypies, whereas stereotypic

Ž .

behaviour was observed in 37% F1 individuals SqPDS . There were no sex differ-ences in the number of SqPDS animals, but significantly fewer males than females

Ž . Ž .

developed stereotypies alone S P-0.05 . Approximately 10% of the F1 animals developed two or more different types of stereotypies. The distribution of different types

Ž .

of stereotypies in F1 is depicted in Fig. 1. The preferred stereotypy was BS P-0.0001 .

Ž . Ž .

JUMP was preferred over PF P-0.01 and WIN P-0.0001 , and no sex differences were shown in stereotypy distribution.

Table 2 shows the age at which the F1 voles were classified as S, PD and PDS. Stereotypies were developed at the age of 96 days for both sexes. Comparisons of the

Ž .

two most common types of stereotypies showed that JUMP appeared earlier 60 days

Ž . Ž .

than BS 105 days P-0.0001 .

There were no relationships between the age at isolation and age at which stereotyp-ies were observed, and there were no effects of isolation age on the number of stereotyping voles.

Table 1

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Proportion % of male and female voles classified as stereotypers S , polydipsic PD and as both

Ž .

stereotypers and polydipsic PDS in P and F1

ClassificationrGeneration W S PD PDS PDqPDS SqPDS

Ž .

Fig. 1. Proportions % of male and female voles showing different types of stereotypies. The total exceeds 100% because some voles showed two or more stereotypies. Abbreviations as in text.

3.2. Polydipsia

Ž There were no significant differences between the occurrence of polydipsia PDq

. Ž . Ž .

PDS in P 22% and F1 29% , but the proportion of polydipsic males was more than Ž

twice the proportion of polydipsic females in both generations P: P-0.05; F1: . Ž .

P-0.001 Table 1 . Daily water consumption in male and female W voles was 9.8 and 9.0 mlrday, respectively. S males drank 9.2 mlrday and S females reached 10.3

Ž .

mlrday P-0.05 compared with W females . PD males drank 67.0 mlrday and PD females reached 60.8 mlrday, while PDS males and females drank 65.6 mlrday and 50.7 mlrday, respectively. There was no sex effect on water consumption.

There was no sex difference in age for showing polydipsia, but polydipsia was

Ž . Ž .

developed later than stereotypies in males 60 vs. 99 days, P-0.001 Table 2 . There

Table 2

Ž . Ž .

Average age in days for the occurrence of stereotypies S and polydipsia PD

PDS-S and PDS-PD indicate age for classification as S and PD in voles showing both stereotypies and polydipsia. Differences between different classifications are shown below.

Day of observation S PD PDS-S PDS-PD

F1

Ž .

Males ns85 99 60 86 62

)

Ž .

Females ns60 94 74 90 114

Malesqfemales 96 63 87 79

Day of observation Males Females Malesqfemales

)) ) )))

S vs. PD NS

S vs PDS-S NS NS NS

)) )

S vs. PDS-PD NS

)) ) )))

PD vs. PDS-S NS

)

PD vs. PDS-PD NS NS

)

PDS-S vs. PDS-PD NS NS

) P-0.05. ) )

P-0.01. ) ) )

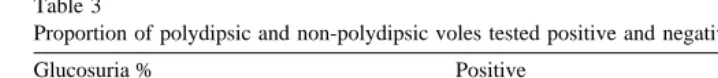

Table 3

Proportion of polydipsic and non-polydipsic voles tested positive and negative for glucosuria

Glucosuria % Positive Negative

Ž .

Polydipsic ns20 65 35

) ) )

Ž .

Non-polydipsic ns20 0 100

) ) )

P-0.001.

were no effects of isolation age on the number of voles developing polydipsia, the time for polydipsia to occur or the amount of water consumed.

3.3. Stereotypies and polydipsia

Ž .

Approximately 7% F1 voles were classified as PDS Table 1 with no significant difference related to sex.

Ž . Ž .

PDS animals developed polydipsia later 79 days than PD animals 63 days , and

Ž . Ž .

this was especially pronounced in females 114 vs. 74 days, P-0.05 Table 2 .

Ž .

Comparisons between all non-stereotyping voles WqPD, ns156 and all

stereo-Ž .

typing voles SqPDS, ns92 showed that polydipsia occurred most frequently in

Ž .

non-stereotypers WqPD: 34%; SqPDS: 20%, P-0.05 .

3.4. Polydipsia and glucosuria

Ž .

Table 3 shows the proportion % of voles tested positive for glucosuria. None of the non-polydipsic voles were tested positive, whereas 65% polydipsic voles showed clear

Ž .

signs of glucosuria P-0.001 .

4. Discussion

The present study repeats the previous findings that laboratory-bred, but not wild

¨

Ž caught voles, easily develop stereotypies under barren housing conditions Odberg,

. 1986; Sørensen, 1987; Sørensen and Randrup, 1986; Cooper and Nicol, 1991, 1996 . Moreover, it demonstrates that males are more disposed to develop stereotypies than females, whereas there are no sex differences in the types of stereotypies shown. BS is the most commonly observed stereotypy in our Danish voles and this is in contrast to the finding of JUMP being the preferred stereotypy in laboratory-bred voles originating

Ž .

from geographically different populations Sørensen, 1987 . Thus, it appears that strain or population differences relate to the types of stereotypies preferably developed in the

¨

Ž .laboratory. Odberg 1987 recorded jumping stereotypies before the age of 30 days in Ž .

voles, and Cooper and Nicol 1991 report that stereotypies in laboratory-bred voles develop when the animals are 4 months old. Apart from possible strain or population differences, estimates of the occurrence of stereotypies depend on the definition of

Ž .

that the behaviour has to fulfil in order to be classified as a stereotypy. It cannot be ignored, however, that management and handling of the laboratory-bred voles play a role for the type of stereotypies developed. When cleaning the cages in the present study, it was necessary to transfer the animals from their home cages with old woodcut bedding to cages with new bedding material. During this procedure, young voles responded almost immediately by showing non-stereotyped jumping movements in the cage corners or against the cage walls in both old and new cages. Non-stereotyping older voles responded with digging in the new bedding material while stereotyping voles exhibited their preferred stereotypy. The jumping responses of the young voles occurred in the breeding cages as well as after isolation. Non-stereotyped jumping in young voles may be interpreted as unsuccessful attempts to escape during disturbance, and the lack of a successful outcome of an otherwise adequate escape response could be the source of

¨

Ž .

subsequent stereotypic behaviour as also suggested by Odberg, 1986 . If so, stereotypic behaviour already developed may be elicited at least partially by the same circumstances that originally caused their development, but in addition that, stereotypies may also occur in other contexts. It could be that these other contexts share the common frustrating feature of unsuccessful results of otherwise adequate behavioural responses such as frustrating effects of social deprivation. The lack of stereotypy development in wild caught voles may thus relate to the lack of such frustrating experiences among young voles in the wild. This interpretation is partially supported by the finding that environmental enrichment of the cage milieu reduces the perseverance of stereotypies in

Ž .

young but not to the same extent in old laboratory-bred voles Cooper et al., 1996 . The development of spontaneous polydipsia in both wild caught and laboratory-bred voles is difficult to interpret. We assume that polydipsia due to its association with high

Ž .

mortality Sørensen and Randrup, 1986 is rare in the wild.

Polydipsia has been observed as a result of diabetes mellitus induced by prolonged glucocorticoid treatment, exposure to toxins, viral infections, surgical lesions and other

Ž

presumable stressful influences Craighead, 1975; Hunt et al., 1976; Mormedes and .

Rossini, 1981; Schlosser et al., 1984; Tarui et al., 1987; Goodwin, 1991 . In the present study, polydipsia was clearly associated with glucosuria. It is therefore possible that keeping voles isolated under barren conditions in the laboratory represents a stressful experience for the animals leading to diabetes and excessive drinking.

Modifying temporal reward patterns under experimental learning conditions can also

Ž .

provoke excessive drinking in rodents Schedule Induced Polydipsia or SIP and this experimentally induced response is frequently used as an animal model for human

Ž .

mental disorders e.g. Woods et al., 1993; Roerh et al., 1995 . Polydipsia is a characteristic feature of chronic schizophrenic humans, but although some

psychophar-Ž

maca effectively reduce spontaneous polydipsia in psychiatric patients Fuller et al., .

1996; Spears et al., 1996; Verghese et al., 1996 , provoked SIP in rodents may be left

Ž .

unaffected by similar treatments Roerh et al., 1995 . Referring to the above-mentioned possible frustrating or stress-related feature of keeping voles isolated under barren conditions, the occurrence of polydipsia in the present study may very well parallel the condition of SIP, which also seems associated with frustration.

The same holds true for explaining why males seem more prone to develop polydipsia than females, while no major sex differences were found in the tendency to develop stereotypies. One possibility is, of course, that both sexes experience frustration under the laboratory conditions leading to stereotypies, but that males are more easily brought to a state of prolonged stress, and for that reason, more easily develop the pathologic state of polydipsia and perhaps diabetes mellitus.

Based on the present findings, the development of stereotypies appears to mitigate the development of polydipsia in both sexes. Very few individuals developed both stereotyp-ies and polydipsia, but among these few, polydipsia occurred later than in voles developing polydipsia alone.

In conclusion, we suggest that the development of stereotypies and polydipsia among bank voles in the laboratory are the results of frustration and prolonged stress. Stereotypies seem to depend on frustrative experiences early in life, while polydipsia may be related to diabetes mellitus caused by the experience of prolonged stress. Moreover, circumstances related to the development of stereotypies may have an adaptive value by reducing the risks of prolonged stress, including the development of fatal polydipsia.

Acknowledgements

The Danish Natural Science Research Council supported this study.

References

Arellano, P.E., Pijoan, C., Jacobson, L.D., Algers, B., 1992. Stereotyped behaviour, social interactions and

Ž .

suckling pattern of pigs housed in groups or in single crates. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 35 2 , 157–166. Bildsøe, M., Heller, K.E., Jeppesen, L.L., 1991. Effects of immobility stress and food restriction on

stereotypies in low and high stereotyping female ranch mink. Behav. Processes 25, 179–189.

Ž .

Broom, D.M., 1983. Stereotypies as animal welfare indicators. In: Smidt, D. Ed. , Indicators Relevant to Farm Animal Welfare. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, pp. 81–87.

Cooper, J.J., Nicol, C.J., 1991. Stereotypic behaviour affects environmental preference in bank voles, Clethrionomys glareolus. Anim. Behav. 41, 971–977.

Cooper, J.J., Nicol, C.J., 1996. Stereotypic behaviour in wild caught and laboratory bred bank voles,

Ž .

Clethrionomys glareolus. Anim. Welfare 5 3 , 245–257.

Craighead, J.E., 1975. Animal models: mice infected with the M variant of encephalomyocarditis virus. Am. J.

Ž .

Pathol. 78 3 , 537–540.

Cronin, G.M., Wiepkema, P.R., Hofstede, G.J., 1985a. The development of abnormal stereotyped behaviours in sows in response to neck tethering. In: The Development and Significance of Abnormal Stereotyped Behaviours in Tethered Sows. Agricultural University, pp. 19–50, PhD thesis.

Cronin, G.M., Wiepkema, P.R., van Ree, J.M., 1985b. Evidence for a relationship between endorphins and the performance of abnormal stereotyped behaviours in tethered sows. In: The development and significance of abnormal stereotyped behaviours in tethered sows. Agricultural University, Wageningen, pp. 51–82, PhD thesis.

Ž .

Feldman, R.S., 1978. Environmental and physiological determinants of fixated behaviour in mammals. In:

Ž .

Carsi Ed. , Proc. 1st World Congress on Ethology Applied to Zoo-technics Vol. 1 Madrid Industrias graficas Espagna, pp. 487–493.

Fuller, M.A., Jurjus, G., Kwon, K., Konicki, P.E., Jaskiw, G.E., 1996. Clozapine reduces water-drinking

Ž .

behavior in schizophrenic patients with polydipsia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 16 4 , 329–332.

Ganong, W.F., 1991. Review of Medical Physiology. 15th edn. Appleton and Lange, Prentice-Hall, London, UK.

Ž .

Goodwin, J.S., 1991. In: Sites, D.P., Terr, A.I. Eds. , Basic and Clinical Immunology. 7th edn. Lange Medical Books, pp. 787–794.

Hunt, C.E., Lindsey, J.R., Walkley, S.U., 1976. Animal models of diabetes and obesity, including the PBBrld

Ž .

mouse. Fed. Proc. 35 5 , 1206–1217.

Lawrence, A.B., Terlouw, E.M.C., 1993. A review of behavioral factors involved in the development and

Ž .

continued performance of stereotypic behaviors in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 71 10 , 2815–2825. Mason, G.J., 1991. Stereotypies: a critical review. Anim. Behav. 41, 1015–1037.

Ž .

Mason, G.J., 1993. Forms of stereotypic behaviour. In: Lawrence, A.B., Rushen, J. Eds. , Stereotypic Animal Behaviour: Fundamentals and Applications to Welfare. C.A.B.I., Wallingford, UK, pp. 7–40.

Mormedes, J.P., Rossini, A.A., 1981. Animal models of diabetes. Am. J. Med. 70, 353–360.

¨ Ž .

Odberg, F.O., 1978. Abnormal behaviours: stereotypies. In: Carsi Ed. , Proc. 1st World Congress on Ethology Applied to Zoo-technics vol. 1 Madrid Industrias graficas Espagna, pp. 475–480.

¨ Ž .

Odberg, F.O., 1986. The jumping stereotypy in the bank vole Clethrionomys glareolus . Biol. Behav. 11, 130–143.

¨

Odberg, F.O., 1987. Behavioral responses to stress in farm animals. In: Wiepkema, P.R., van Adrichem,

Ž .

P.W.M. Eds. , Biology of Stress in Farm Animals: An Integrative Approach. Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecht, pp. 135–150.

Roerh, J., Woods, A., Corbett, R., Kongsamut, S., 1995. Changes in paroxetine binding in the cerebral cortex of polydipsic rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 278, 75–78.

Rushen, J.P., 1985. Stereotypies, aggression and the feeding schedules of tethered sows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 14, 137–147.

Sahakian, B.J., Robbins, T.W., Morgan, M.J., Iversen, S.D., 1975. The effects of psychomotor stimulants on stereotypy and locomotor activity in socially-deprived and control rats. Brain Res. 84, 195–205. Spears, N.M., Leadbetter, R.A., Shutty, M.S., 1996. Clozapine treatment in polydipsia and intermittent

Ž .

hyponatremia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 57 3 , 123–128.

Sørensen, G., 1987. Stereotyped behaviour, hyperaggressiveness and ‘‘tyrannic’’ hierachy induced in bank

Ž .

voles Clethrionomys glareolus by a restricted cage milieu. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychia-try 11, 9–21.

Sørensen, G., Randrup, A., 1986. Possible protective value of severe psychopathology against lethal effects of an unfavourable milieu. Stress Med. 2, 103–105.

Tarui, S., Yamada, K., Hanafusa, T., 1987. Animal models utilized in the research of diabetes mellitus with special reference to insulitis-associated diabets. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 229, 211–223.

Verghese, C., deLeon, J., Josiassen, R.C., 1996. Problems and progress in the diagnosis and treatment of

Ž .

polydipsia and hyponatremia. Schizophr. Bull. 22 3 , 709–713.

Wemelsfelder, F., 1993. The concept of animal boredom and its relationship to stereotyped behaviour. In:

Ž .

Lawrence, A.B., Rushen, J. Eds. , Stereotypic Animal Behaviour: Fundamental and Applications to Welfare. C.A.B.I., Wallingford, UK, pp. 65–95.