Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Comparison of Management Faculty Perspectives

on Quizzing and Its Alternatives

Paul Bacdayan

To cite this article: Paul Bacdayan (2004) Comparison of Management Faculty Perspectives on Quizzing and Its Alternatives, Journal of Education for Business, 80:1, 5-9, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.80.1.5-9

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.1.5-9

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 12

View related articles

hen an entire section of students shows up without having pre-pared the day’s homework, it can hinder the in-class activities for that day. When such behavior becomes frequent, the atmosphere and achievement of the class can decline markedly. Students who ignore homework assignments may subsequently miss related points in lec-tures, behave passively in case discus-sions, or miss the conceptual element in experiential exercises.

The topic of how to deal with poor student preparation—including giving quizzes and their alternatives—is timely. The economic downturn has tightened university budgets (Chaptman, 2002; Klein, 2004; Russell, 2003) and promot-ed conditions that may rpromot-educe student preparation. For example, larger classes are efficient but may reduce preparation by allowing student anonymity (Chism, 1989; Doran & Golen, 1998). Also, cuts in financial aid may reduce student preparation as students work ever more hours at part-time jobs (Dutton & Gokcekus, 2002). These economic fac-tors serve only to heighten the effect of other conditions that already lower stu-dent preparation. These conditions include disengaged students (Trout, 1997), a decline in the basic academic skills of incoming students (Lanier, Tan-ner, Zhu, & Heady, 1997), and students with expectations of acceptable grades

for subpar work (Landrum, 1999). Finally, instructors may be reluctant to push students because of concerns that low student grades will result in low teaching evaluations (Wallace & Wal-lace, 1998; Winsor, 1977). These factors all may combine to reduce student preparation and allow a decline in acad-emic standards.

As a policy response to the potential erosion of academic standards, Crumb-ley (1995) argued that it may be neces-sary for some schools or departments to introduce “regulated courses.” In such courses, all instructors apply rig-orous uniform procedures (including norms for workload, testing proce-dures, and grade distributions). Although this uniformity somewhat restricts the instructor’s discretion, Crumbley argued that it can help boost academic standards while insulating instructors from backlash from

stu-dents unhappy about being pushed. The regulated course presents a united front to students and reduces dispari-ties in workload between sections.

A less extreme policy, but with some resemblance to the regulated course, might simply mandate the use of quizzes to boost student preparation. Quizzes are defined as short, relatively frequent (often weekly) tests on a limited amount of material. This definition is in line with previous uses in the educational litera-ture (Michaelsen, Fink, & Watson, 1994; Noll, 1939; Turney, 1931) and accom-modates the fact that quizzes can vary widely in weight, question type, content overlap with exams, and other character-istics. A uniform policy of mandated quizzing, especially in large multi-instructor introductory courses, would serve to protect those who might other-wise hesitate to quiz. But would it truly be necessary to propose such a policy at very many schools? Data indicate that although quizzes may be useful for some instructors, not all will find that a policy of uniform quizzing is the best way to boost student preparation.

Research Questions

In this article, I offer data about fac-ulty perceptions on three practical ques-tions related to the idea of uniform man-dated quizzes.

Comparison of Management Faculty

Perspectives on Quizzing and

Its Alternatives

PAUL BACDAYAN

University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth Dartmouth, Massachusetts

W

ABSTRACT.In this study, the author compares the views of faculty mem-bers who give quizzes and those who do not regarding (a) the potential drawbacks of quizzing and (b) the via-bility of various quiz alternatives such as graded homework. The results sug-gest that quizzers and nonquizzers have much in common and that quizzing is simply one of a variety of potentially effective techniques for boosting student preparation. The author also presents data on typical quiz practices.

My first question is “What represents typical quizzing practices?” A clear pic-ture of typical quizzing practices could help set the parameters for any mandated quizzing approach. Also, this informa-tion could help individual instructors, whether they currently use quizzes or not, to visualize the quiz arrangements and course designs that quiz-using col-leagues have found workable. Accord-ingly, data are needed on the number of quizzes given, their weight, the degree of warning given, and the use of group quizzes (Michaelsen et al., 1994).

The remaining research questions compare the views of instructors who quiz (“quizzers”) with the views of those who do not quiz (“nonquizzers”). These questions address the advisability of a uniform quizzing policy by identi-fying quiz drawbacks as well as viable nonquiz methods that can supplement or replace quizzes.

The second question is “What draw-backs of quizzing might discourage quiz usage?” Instructors may perceive both instrumental and pedagogical drawbacks to quizzing. Each kind of drawback has different implications for the potential usefulness of a uniform quizzing policy. For example, on the one hand, if instructors perceive instru-mental drawbacks to quizzing (i.e., quizzing hurts instructors), this finding would be favorableto a quizzing poli-cy. Faculty members may believe that quizzes—especially if they contribute to lower grades for some students— will worsen the end-of-term teaching evaluations. Certainly there is a long history of concern about the impact of lower grades on student evaluations of teaching (Wallace & Wallace, 1998; Winsor, 1977; Worthington & Wong, 1979). On the other hand, a finding that instructors perceive pedagogical draw-backs (i.e., quizzing somehow hurts the learning process) would be unfavorable to a quiz policy. For example, faculty members may believe that quizzes take excessive class time from other valu-able activities.

The third research question is “How do quizzes compare with potential alter-native techniques for motivating student preparation?” If faculty members per-ceive viable alternatives to quizzing, it might be preferable to allow them to use

those techniques instead. These alterna-tives include both “soft” and “hard” techniques. Soft techniques include inspirational speeches and focusing on topics or exercises of interest to the stu-dents (Buskist & Wylie, 1998). Hard techniques include graded homework and announced quizzes. Hard techniques align extrinsic rewards with desired behavior, as suggested by Kerr (1975) in his well-known article “The folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B.” Even small increases in accountability can change student behavior, as illustrated by McDougall and Cordeiro’s (1993) finding that community college students who expected cold-call questions pre-pared significantly more than students who expected a lecture.

Data on these three questions would tell us more about the nature and advis-ability of a uniform quizzing policy, as well as about potentially viable alterna-tives to quizzing.

Method

Responses from 78 faculty members, which respresented a 68% response rate, provided the data for addressing the three research questions. All respondents were instructors in organizational behavior, human resources, or strategy. Participants were members of an academic profes-sional organization. A total of 115 sur-veys were distributed to members at the group’s annual meeting in spring 2001. I present a profile of the respondents in Table 1. They are evenly divided between tenured and untenured faculty members. We should note that the sample was split almost evenly between those who had used quizzes in the previous 3 years (53%) and those who had not (47%).

Findings

Typical Quizzing Practices

I initially defined quizzes as short, relatively frequent tests on a limited amount of material. The data in this sec-tion allow us to go beyond that defini-tion to specify what represents com-mon, mainstream practices regarding quizzes. Furthermore, by revealing the compromises that other quizzers have found acceptable, the data also provide

a baseline against which quizzers may compare their own practices.

Number of quizzes per semester. For those who quizzed, the average number of quizzes per semester was 6.6. This represents about half the weeks in a 14-week semester.

Weight assigned to quiz scores. The average assigned weight was 16% of the final grade. Weights of 10%, 15%, and 20% were most common. Quizzes were not substituting for other forms of eval-uation (exams, papers, participation) but appeared to be supplementing these other indicators of student performance.

Pop and announced quizzes. Pop quizzes were given relatively rarely. Announced quizzes outnumbered pop quizzes by a wide margin: Sixty-four percent of the respondents reported using only announced quizzes, with the remainder evenly split between other formats. I show these results in Figure 1.

Group and individual quizzes.Finally, it appears that group quizzes are rare compared with individual quizzes (Michaelsen et al., 1994). Seventy-nine percent of the faculty respondents in my study reported using individual quizzes exclusively.

TABLE 1. Profile of Instructors (N= 78)

At schools that grant MBAs: 83% At schools that do not grant PhDs in

business: 74%

Teach management/HRM/OB: 67% Teach strategy: 23%

Teach other fields: 10% At schools with AACSB

accreditation: 57% Male: 55%

Female: 45%

At public (state-affiliated) schools: 54%

Gave quizzes to classes within the past 3 years: 53%

Tenured: 50%

Not tenured: 50% (32% are tenure-track, 18% are adjuncts or students)

Have >21 years of teaching: 30% Have 10–20 years of teaching: 34% Have 1–9 years of teaching: 36%

Perceived Drawbacks of Quiz Use

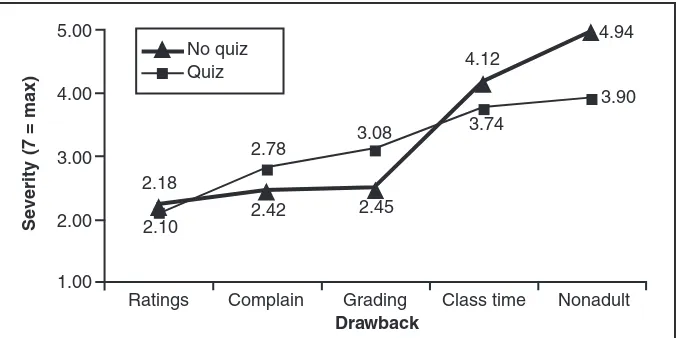

A second set of questions asked instructors about selected drawbacks that might discouragequiz use. Using a 7-point scale with the anchor points 1 (minimal drawback), 4 (moderate drawback), and 7 (large drawback), respondents rated items for degree of difficulty posed. In Figure 2, I com-pare the ratings by nonquizzers and quizzers. The drawbacks are again arranged in ascending order by the rat-ings of the nonquizzers; issues on the right are the biggest drawbacks for the nonquizzers.

Answers for all five items tend to suggest relatively low absolute levels of concern; most answers were under 4.0 (i.e., moderate drawback or less). The item of greatest concern for nonquizzers was “Quizzes are not consistent with treating students as adults.” Although the quizzers saw this as a moderate dis-advantage (average 3.90), the non-quizzers were inclined to see it as a larg-er disadvantage (avlarg-erage 4.94). Of the five items, this was the only one with a statistically significant difference (p = .018, t test of independent samples). The item about nonadult treatment appears to the right of Figure 2.

The next-greatest perceived draw-back, the amount of in-class time that quizzes can consume, was also peda-gogical. Grading (an instrumental con-cern) was not seen as a major drawback.

Interestingly, the perceived possibility of student backlash appeared to be a minor issue, as shown by results for the last two instrumental items: “Students might complain about the quizzes” and “Quizzes might lower (harm) the ratings that I get from students.” Neither had a high average, and neither showed statis-tically significant contrasts between the quizzers and nonquizzers. (The item regarding instructor ratings got a mean rating of only 2.10 from quizzers and 2.18 from nonquizzers.) The numbers indicate less concern among the respon-dents regarding ratings than one might expect, given the amount of publications focusing on concerns about the impact of student evaluations of teaching on academic standards (Crumbley, 1995). Thus, the results do not support the adoption of a uniform quiz policy.

Quizzes Versus Alternative Ways to Boost Preparation

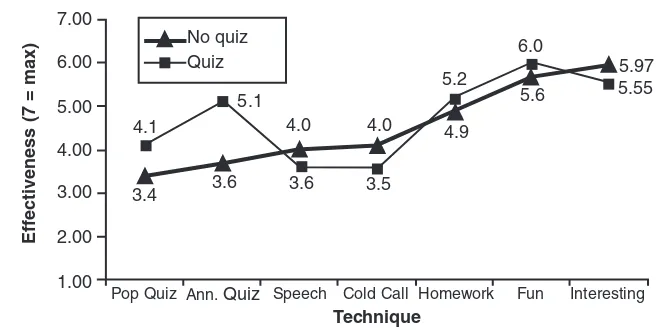

I presented faculty members with seven techniques, including quizzes, and asked them to rate each technique for its effectiveness in motivating preparation (see Figure 3). Respondents answered on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all effec-tive) to 7 (highly effective). In Figure 3, I compare the ratings by nonquizzers (n= 37) and quizzers (n= 41). The techniques are arranged in ascending order accord-ing to the rataccord-ings of the nonquizzers; techniques on the right were deemed most effective by the nonquizzers. Only the quiz-related techniques showed sta-tistically significant differences (ttest of independent samples) between quizzers and nonquizzers. Quizzers ascribed

greater effectiveness to both forms of quizzing (pop quizzes, p = .035; announced quizzes, p = .000). These items appear on the left side of Figure 3. Quizzes aside, the respondents agreed on the effectiveness of the other five techniques. One of the soft tech-niques, inspirational speeches, received low absolute ratings from both quizzers and nonquizzers. Soft techniques that topped the list for both groups included making class fun and focusing on topics interesting to the students. Among hard techniques, cold calling received rela-tively low ratings, whereas graded homework scored relatively well. The techniques with the highest joint ratings from both groups were a mix of hard and soft techniques: graded homework, interesting topics, and making class fun.

Announced 64%

MIxed 18% Pop 18%

FIGURE 1. Proportion of quizzes announced, pop, and mixed.

Ratings 5.00

No quiz

FIGURE 2. Drawbacks of quizzing.

Quiz 4.00

3.00

2.00

1.00

Se

verity (7 = max)

Complain Grading Class time Nonadult

Drawback

2.18

2.78 3.08

3.74

3.90

2.10 2.42

2.45

4.12

4.94

Discussion

The generalizability of the findings is limited to some extent by the sample. Respondents were in the discipline of management and worked at teaching-oriented schools. The results may differ for disciplines such as accounting or at highly research-oriented schools. Future research might explore differences among disciplines or types of schools. Despite limitations in the sample, how-ever, the current findings do provide the basis for five implications.

Implications for Instructors

First, regarding mandatory quiz cies, the findings suggest that such poli-cies may simply be unnecessary. Stu-dent backlash about quizzes apparently was not a major concern for the respon-dents in the current sample. The united front presented by a mandatory quiz policy apparently provides unneeded protection.

Second, the data suggest that instruc-tors (both quizzers and nonquizzers) perceive a whole portfolio of viable techniques. Not even the quizzers them-selves appear to rely solely on quizzing; rather, they are generally positive about the motivational impact of techniques such as making class fun. Conversely, nonquizzers are not entirely averse to hard approaches: Graded homework was rated highly by both groups. Regarding uniform quiz policies, these results indicate that quizzing need not be mandated as long as instructors are

willing to employ a variety of motiva-tional techniques.

Even for especially tough groups of students for whom only hard techniques will suffice, instructors can create accountability without quizzing. In addi-tion to graded homework, they can use the McAleer Interactive Case Analysis Method (Desiraju & Gopinath, 2001; Siciliano & McAleer, 1997) and the technique of frequent testing (Murphy & Stanga, 1994). The McAleer method fea-tures a requirement that class members submit action recommendations about a case on the day before the discussion. The frequent testing method uses numer-ous small tests instead of a handful of major exams. Murphy and Stanga (1994) compared a traditional accounting class (using 2 or 3 exams) with a frequent-testing treatment (using 6 mini-exams). Although the results on the final were the same, the scores on the mini-exams were higher than the scores for the tradi-tional condition. Interestingly, the end-of-term teaching evaluations were higher for the frequent-testing group. These additional techniques—the McAleer Interactive Case Analysis method and the “frequent testing” approach—offer potentially useful new ways to create interim student accountability for class preparation.

Third, quizzers might reflect serious-ly on how their use of quizzes might support the ideal of “treating students as adults.” The idea of treating students as adults is important because such treat-ment may enhance students’ intrinsic motivation for learning. The need to

cul-tivate internalized study habits already has been raised by mainstream educa-tional researchers (Nolen, 1988). Inter-nalization matters in a business school setting because business graduates need a positive attitude toward lifelong learn-ing to keep up with changes in technol-ogy and business practices (Lynton, 1984). Quizzes raise a red flag because, like other extrinsic motivators, they may lessen intrinsic motivation (Deci, 1971). However, an instructor’s use of quizzes does not mean necessarily that the instructor does not care about treating students like adults. Instructors who use quizzes might benefit from asking: Does the way that quizzes are used in my class simply compel short-term perfor-mance, or can it also help to develop stu-dents’ intrinsic motivation and lifelong study habits? Quizzes may not automat-ically extinguish intrinsic motivation, especially when supplemented by non-quiz motivational techniques. Quizzes for some students also may be a neces-sary developmental step that guides them toward acting like adults: A stu-dent’s small wins on quizzes ultimately may build that student’s work habits and develop a sense of self-efficacy (Wesp, 1986).

Fourth, if classroom conditions should indicate that quizzes are appro-priate, then announced quizzes may work best. In this study, I found that quizzers see announced quizzes as hav-ing a much stronger motivational impact than pop quizzes. The specific deadline of an announced quiz may pro-voke more actual study than the free-floating threat of a pop quiz.

Fifth and finally, the conditions that may call for hard motivational techniques (including quizzes) may be on the upswing. Serious budget shortfalls exist at many public and private colleges (Associated Press, 2002; Chaptman, 2002), and tuition increases may be insufficient to close the gap (Klein, 2004; Russell, 2003). As a result, administra-tors are being forced to cut financial aid, boost admissions, and trim staff. Student preparation may decline further as more students respond to less availability of financial aid by taking part-time jobs (Dutton & Gokcekus, 2002) and larger classes allow student anonymity (Chism, 1989; Doran & Golen, 1998).

Pop Quiz

5.00

No quiz

FIGURE 3. Motivational techniques compared for effectiveness.

Quiz

ectiveness (7 = max)

Ann.Quiz Speech Cold Call Homework Technique

Conclusion

A classroom full of prepared students can better undertake in-class learning activities. Unfortunately, students do not always prepare. Indeed, the current economic contraction may foster situa-tions (such as a move to large secsitua-tions) that require increased attention to stu-dent motivation. To boost stustu-dent prepa-ration, faculty members should under-stand faculty views on what works best, including not only quizzes but alterna-tives as well. An appreciation of the options can give instructors the tech-niques to help the contemporary class truly perform.

REFERENCES

Associated Press. (2002, November 26). State coffers are hit hard; Budgets worst since WWII; Tax hikes loom. The Boston Globe,p. C2.

Buskist, W., & Wylie, D. (1998). A method for enhancing student interest in large introductory classes. Teaching of Psychology, 25(3), 203–205.

Chaptman, D. (2002, December 6). Cuts put squeeze on Wisconsin campuses; Schools say they’re strapped for funds. The Boston Globe,p. A18.

Chism, N. V. (1989). Large enrollment classes: Necessary evil or not necessarily evil? Notes on Teaching, 5 [occasional paper]. Columbus: Ohio State University, Center for Teaching Excellence.

Crumbley, D. L. (1995). The dysfunctional atmos-phere of higher education: Games professors play. Accounting Perspectives, 1,67–76. Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated

rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Per-sonality and Social Psychology, 18,105–115. Desiraju, R., & Gopinath, C. (2001). Encouraging

participation in case discussions: A comparison of the MICA and the Harvard Case methods. Journal of Management Education, 25, 394–408.

Doran, M. S., & Golen, S. (1998). Identifying communication barriers to learning in large group accounting instruction. Journal of Edu-cation for Business, 73(4), 221–224. Dutton, M., & Gokcekus, O. (2002, Fall). Work

hours and academic performance. Journal of the Academy of Business Education, 3, 99–105. Kerr, S. (1975). On the folly of rewarding A, while

hoping for B. Academy of Management Jour-nal, 18, 769–783.

Klein, A. (2004, March 5). States move to limit increases in tuition. The Chronicle of Higher Education,p. 26.

Landrum, R. E. (1999). Student expectations of grade inflation. Journal of Research and Devel-opment in Education, 32,124–128.

Lanier, P. A., Tanner, J. R., Zhu, Z., & Heady, R. B. (1997). Evaluating instructors’ perceptions of students’ preparation for management curric-ula. Journal of Education for Business, 73, 77–84.

Lynton, E. A. (1984). The missing connection between business and the universities. New York: Macmillan.

McDougall, D., & Cordeiro, P. (1993). Effects of random-questioning expectations on communi-ty college students’ preparedness for lecture and discussion. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 17,39–49.

Michaelsen, L. K., Fink, L. D., & Watson, W. E. (1994). Pre-instructional minitests: An

effi-cient solution to the problem of covering con-tent. Journal of Management Education, 18, 32–44.

Murphy, D. P., & Stanga, K. P. (1994). The effects of frequent testing in an income tax course: An experiment.Journal of Accounting Education, 12(1), 27–41.

Nolen, S. B. (1988). Reasons for studying: Moti-vational orientations and study strategies. Cog-nition and Instruction, 5,269–287.

Noll, V. H. (1939). The effect of written tests upon achievement in college classes: An experiment and a summary of evidence.Journal of Educa-tional Research, 32,345–357.

Russell, J. (2003, September 4). A leaner UMass opens with much bigger classes. The Boston Globe,p. B4.

Siciliano, J., & McAleer, G. M. (1997). Increasing student participation in case discussions: Using the MICA method in strategic management courses.Journal of Management Education, 21, 209–220.

Trout, P. A. (1997). Disengaged students and the decline of academic standards. Academic Ques-tions, 10,46–56.

Turney, A. H. (1931). The effect of frequent short objective tests upon the achievement of college students in educational psychology. School and Society, 33,760–762.

Wallace, J. J., & Wallace, W. A. (1998). Why the costs of student evaluations have long since exceeded their value.Issues in Accounting Edu-cation, 13,443–447.

Wesp, R. (1986). Reducing procrastination through required course involvement. Teaching of Psychology, 13,128–130.

Winsor, J. L. (1977). A’s, B’s, but not C’s?: A comment. Contemporary Education, 48,82–84. Worthington, A. G., & Wong, P. T. P. (1979).

Effects of earned and assigned grades on stu-dent evaluations of an instructor. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71,764–775.