C

OMMITMENT WITHIN A

B

ANKING

S

ERVICES

C

ALL

C

ENTRE

EDROSE*

T

he advent of the call centre workplace phenomenon has re-kindled debate within labour process theory, particularly in relation to control issues concerning service sector work and routinisation of clerical and white-collar labour. There has been rather more limited discussion of employment relations matters emanating from the call centre labour process. This paper considers issues such as absenteeism and labour turnover, management control, work intensification, union and organisational commitment within a banking services call centre based in Liverpool, UK. The main findings of the research indicate that employees or ‘agents’ were frustrated and bored with repetitive and standardised work operations; that there were high levels of managerial control and surveillance and that there was little opportunity for exercising creativity and autonomy in the work situation. The commitment of agents to their organisation was, not surpris-ingly in the light of these findings, correspondsurpris-ingly low. Agents, who were unionised, were moderately committed to their trade union despite some disappointment concern-ing the apparent inability of local union representatives to pursue and process grievances effectively. The paper concludes that the ‘sweatshop’ image of call centres is to some extent at least, confirmed within the research context.Call centres are one of the most rapidly growing global industries within a wide range of sectors. From a management perspective, call centres increase the efficiency of customer service interactions while minimising the cost of those interactions. Call centres through enabling technologies such as ‘data ware-housing’ and ‘data mining’ also establish ‘customer information databases’ which are essential to increasing efficiency of service while justifying costs. Call centres are used by organisations for a variety of functions including telesales, customer service, collections and account management. The perspective from an employee and organised labour standpoint is not so sanguine. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) in Britain, in recognition of the fact that 350 call handlers or ‘agents’ contacted the organisation in a period of 6 days, identified bullying, the setting of impossible sales targets, not getting wages on time and hostility towards trade union representation as major problems facing employ-ees. In Australia, where call centre growth has been extremely rapid in recent years, unions such as the Australian Services Union (ASU) have recently launched

a recruitment campaign, by emphasising employers’ control over employees, pres-surised work and absence of career prospects.

This paper, which deals with the British context, focuses upon two issues affect-ing call centres generally. The first concerns the ongoaffect-ing debate about the employment and human consequences of the call centre labour process and the extent to which call centre employees show any degree of commitment to their employing organisation, while the second relates to the notion of union com-mitment and the extent to which a unionised workforce perceives the union as an effective channel for dealing with issues central to the concerns of call centre workers or ‘agents’. Correspondingly, one of the main assertions made in this paper is that, within a call centre context, it is highly unlikely that call centre employees will display both high levels of organisational and union commitment.

With regard to the first issue, existing research tends to fall into one of two camps. The first, which we may call the ‘bleak house’ view stresses the control-ling and alienating nature of call centre work and technology, depicting agents as working on an ‘assembly line in the head’ (Taylor & Bain 1999). Call centres are metonymically referred to as ‘psychic prisons’ and ‘electronic panopticons’, emphasising the totalising environments in which ‘agents’ work and from which there is no escaping the constant electronic surveillance of work operations and the monitoring of performance. Agents are isolated from their colleagues despite attempts to encourage, or at the very least pay lip service to, ‘teamworking’. The demographics of call centre employment where an increasing proportion of agents are part-timers and students tends to encourage a culture of ephemerality mani-fested by high labour turnover or ‘churn’ and voluntary absenteeism. The flat organisational hierarchy within the call centre, facilitated by the technology employed, tends to limit the promotion opportunities of an already peripheral-ised workforce.The second ‘camp’, which contrasts with the first and which we may describe as the ‘happy house’ view is that of the empowered ‘pink-collared’ worker, who can respond to a range of customer service requirements thanks to the IT on his/her desk and who has a high level of skills, knowledge and on-the-job training. Agents are considered to be a key strategic resource for the organ-isation and, as such, receive pleasant working conditions, and relatively high levels pay and benefits. Clarity of staff roles and increased accountability result in improved teamworking, customer contact and increased productivity.

private medical and dental care do not detract from the ‘sweatshop conditions’ which prevail. Within unionised contexts, however, union commitment may be regarded as a substitute or a palliative for the absence of any significant degree of organisational commitment experienced by employees.

CALL CENTRE GROWTH AND THEUK FINANCIAL SERVICES SECTOR The UK call centre market is the largest in Europe with a 39 per cent share of the market and the call centre industry is one of the fastest growing industries in the UK with around 400 000 full-time equivalent jobs accounting for 1.8 per cent of all employment. Estimates of future growth within the call centre industry vary. As the UK call centre market is relatively mature, the rate of increase in agent positions will probably slow within the next few years, the demand for call centre agents also being reduced as speech recognition and other technolo-gies develop and internet use increases. It has been predicted, for example, that by 2004, 40 per cent of all call centre workers in the UK will be replaced by speech recognition software (OTR 2001). Notwithstanding this, and according to Datamonitor (2000), an additional 480 call centres (including a significant proportion within the public sector) will have been created by 2003, providing a further 100 000 jobs.

In terms of vertical market size, financial services remains the largest market accounting for just under 45 000 agent positions and 27 per cent of the call centre market, followed by manufacturing and distribution (22 per cent) and tele-coms (10 per cent). In relation to employment generally, the overall proportion of outsourcing in the UK call centre market was 7 per cent of agent positions in 1997, rising to 10 per cent in 2000 (Datamonitor 2000). Within financial services, there are a number of problems, (many of which are not confined to the UK), which affect the extent, development, and nature of call centres and their employment profile.

From over-regulation to under-regulation

The trend during the past 15 years has been towards a highly deregulated market, mainly as a result of the 1986 Financial Services Act which opened up the sector to increased competition and provided opportunities for non-traditional providers such as supermarkets and others such as Virgin to enter the sector.

Globalising tendencies

migrate to low wage economies such as India and Mexico. As it is technically no more complex to route customer calls to these countries, as opposed to say Liverpool, companies can expect to profit from such global enterprise.

‘Rationalisation’

Partly as a result of increased competitive pressures within a progressively deregulated market, UK banks were forced to rationalise operations, close branches, make staff redundant and restructure themselves in order to protect their market share and maximise profitability. For example, between 1990 and 1995, 120 000 jobs were lost in the core financial services sector. By 2002, further losses will drive down the workforce towards the 200 000 mark, assum-ing an ongoassum-ing annual decline in the workforce of around 2 per cent together with further mergers and takeovers such as the RBS takeover of NatWest and the Lloyds/TSB takeover of Abbey National.

Technology

Within banking, initial developments in technology have resulted in the auto-mation of processing with the introduction of cash dispensers (ATMs) and a move from a relatively highly skilled, labour intensive retail operation based around products and services, to one located increasingly away from the High Street branch within call centres. Innovations such as voice recognition, and sophisti-cated software which facilitates data warehousing, have transformed the way products are marketed and sold. Call centre technology can substantially increase productivity in telephone call handling. Automated call distribution (ACD), computer–telephony integration (such as the ‘screen popping’ of customer infor-mation to computer screens) and the use of standard scripts by staff mean that the time taken to deal with calls, and the ‘free’ time between calls, can be pared to the bare minimum. The technique of predictive dialling (the use of software to dial outbound calls automatically, transferring calls when they are answered to available members of staff) alone enables the ‘equivalent of one day’s work to be done in one hour’ (Bibby 2001).

The call centre ‘challenge’

changes in the pattern of telephone use and consumer perceptions of overcharging on the part of banks and insurance companies, thereby adding a competitive dimension to this area of sales.

THE CALL CENTRE LABOUR PROCESS WITHIN FINANCIAL SERVICES The call centre labour process has been well documented in recent years (Garson 1988; Frenkel et al. 1998; Mitial 1999; Taylor & Bain 1999; TUC 2001). However, many of the characteristics of call centre work have a common antecedent stem-ming from Marx’s ideas concerning alienation. Subsequent contributions focus-ing specifically on ‘white-collar’ work durfocus-ing the course of the twentieth century (Lockwood 1958; Blackburn & Prandy 1965, for example) refer to the process of ‘proletarianisation’ of the white-collar worker in terms of work, market and status situations. For example, changing work situations concern the routinisation of tasks as a result of technological developments which facilitated deskilling of, and tighter supervisory/managerial control over, work operations. Changing market situations for clerical labour were determined partly by the supply and demand for such labour. Where the increased supply of relatively unskilled labour often exceeded the demand for such labour, the result was reflected in lower wages and a deterioration in terms and conditions of employment vis-a-vis manual workers which in turn resulted in a deterioration in the social status of clerical labour. A further related development was concerned with the femin-isation of routine clerical work; employers could more easily dispense with female workers as increasing numbers of them sought temporary work prior to mar-riage and family building. The lowering of status and deterioration of the labour process and work situation of clerical labour (Baldry et al. 1998) also gave rise to increased unionisation of white-collar workers within the finance and banking sector, and more generally. We could, therefore, contend that the call centre labour process merely replicates the situation of clerical labour which had already become proletarianised, feminised and deskilled. An appropriate depiction of call centre work from this perspective is provided by Bibby (2001):

. . . human agents submit to a highly controlled work regime. Call centres have evoked comparisons with the sort of assembly-line working in manufacturing associated with Henry Ford and Taylorism. Some have described call centres as the electronic assem-bly line of the twenty-first century. The degree of surveillance necessary has also invited unfavourable comparisons, for example with nineteenth century designs for prisons or even (by one call centre worker) with Roman slave ships: ‘You feel like you are on a galley boat being watched, answering calls every 30 seconds, monitored and told off if there are mistakes’. (Channel 4 TV (UK), Special Report, broadcast 14 Dec. 1999).

The TUC (2001), in its report heralding the ‘call centre workers’ campaign’ describes a number of cases exemplifying the ‘sweatshop’ approach taken by many employers. For example, there have been instances where:

• employees ‘were expected to make time up when they went to the toilet’; • employees ‘were expected to take two calls a minute for seven and a half hours

a day;

• employees had to buy their own headsets;

• employees experienced ‘acoustic shock’ (sound surges via telephone headsets resulting in acute pain and loss of short-term memory).

Nevertheless, there is a powerful case (Frenkel et al. 1998) for arguing that the call centre phenomenon has also had the effect of polarising the call centre labour process into two ‘ideal typical’ forms which may be termed ‘routinised’ and ‘empowered’, where the former represents an amplification of the deskilling and proletarianisation processes referred to, while the latter is concerned with post Fordist flexible specialisation (Piore & Sabel 1984) and with ‘upskilling’ rather than deskilling tendencies. The TUC (2001) report also provides examples of ‘best practice’ which include flexible working arrangements, provision of creche and other facilities, recognition of trade unions, open learning facilities, group rather than individual performance measurement and zero tolerance for any form of harassment , bullying, intimidation or victimisation. Within financial services, elements of both routinisation and empowerment types are likely to exist, with the former predominating over the latter. In essence, the following character-istics of the call centre labour process in financial services may be present: • emotional labour (Hochschild 1983) and ‘smiling down the phone’ (Taylor &

Bain 1999);

• use of ACD/voice recognition to accelerate and intensify work operations; • ‘dual supervision’––both electronic and human within the workplace and

aug-mented by customer response outside the workplace; • work duties essentially ‘customer satisfaction’ driven.

It should be emphasised that the diverse nature of the financial services sector is reflected in the diversity of call centres within it over a range of variables, the most important of which include size of organisation and workplace, nature and complexity of operations, presence or absence of trade unions, monitoring and surveillance measures and agents’ exposure to these and the sheer intensity of work operations.

UNIONISATION AND UNION COMMITMENT WITHIN FINANCIAL SERVICES There is some evidence which suggests that there is a greater propensity towards trade unionism in banking, insurance and finance than in many other industry sectors. (Gall 1997; Kelly 1996, 1998). Whether this trend is indicative of greater collective resistance to the labour process as manifested by ‘militancy’ is, how-ever, questionable. Two significant events in recent years seem to point to con-tradictory conclusions.

employees seek to protect their increasingly precarious employment situation. During the past decade or so, for example, performance-related, profit-related and sales/commission-based pay systems have increasingly replaced automatic cost of living pay increases, while the workforce has become increasingly ‘flexible’ with the growing use of part-time, temporary agency staff. Direct com-munication with staff is common and sickness and absenteeism records have been used as redundancy criteria. Sick pay has been made dependent on length of service for new staff and a new corporate culture based on competitive sales-oriented policies introduced. The culture of the customer now dominates as man-agement attempts to shift the focus of control from outside the individual to within so that employees themselves become accountable for their own performance and supposedly ‘committed to attaining quality in a highly motivated fashion’ (Oakland 1989). Until very recently, the actions of financial sector companies suggested that they were taking a more exacting and uncompromising line with trade unions as a consequence of both the introduction of human resource man-agement (HRM) and total quality manman-agement (TQM) policies and increased collective resistance as a reaction to the exercise of managerial prerogative within a period of increasing employment and organisational change. Manifestations of this tougher managerial stance include instances of employers refusing to recog-nise and de-recognising trade and staff unions, one of the most notable being the withdrawal of collective bargaining rights from managerial employees of Midland Bank (now HSBC) in 1996.

The second eventwas the signing of a ‘Partnership Agreement’ between Barclays and the newly merged Unifi in April 2000. The Employment Relations Act 1999 places the concept of partnership between management and unions at the

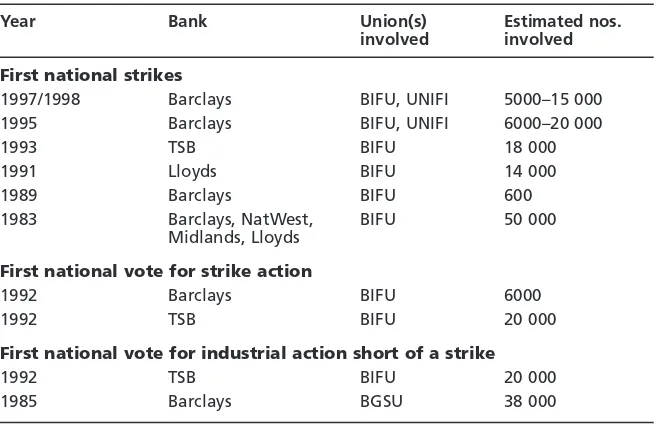

Table 1 Instances of industrial action within banking

Year Bank Union(s) Estimated nos.

involved involved

First national strikes

1997/1998 Barclays BIFU, UNIFI 5000–15 000 1995 Barclays BIFU, UNIFI 6000–20 000

1993 TSB BIFU 18 000

1991 Lloyds BIFU 14 000

1989 Barclays BIFU 600

1983 Barclays, NatWest, BIFU 50 000 Midlands, Lloyds

First national vote for strike action

1992 Barclays BIFU 6000

1992 TSB BIFU 20 000

First national vote for industrial action short of a strike

1992 TSB BIFU 20 000

1985 Barclays BGSU 38 000

centre of its workplace agenda with the intention of replacing ‘the notion of con-flict between employers and employees with the promotion of partnership’. The agreement was the result of almost two years of discussion between Unifi and Barclays to rebuild a relationship after a damaging dispute in 1997/1998, and ‘commits both parties to work for the success of the business and to make Barclays a better place to work for all its employees’ (Unifi 2000). To be sure, evidence of adversarial industrial relations within banking was not difficult to find during the 1980s and 1990s, as Table 1 indicates. Instances of industrial action to include strikes and action short of striking were particularly frequent during the 1990s, with Barclays featuring prominently.

However, it should be noted that bank employees in general could not be described as ‘militant’. Many ballots for industrial action continue to be rejected by the finance unions and staff associations and their members. In addition, the pattern of voting for action by union members has been neither consistent nor constant; a substantial proportion of votes for industrial action followed by actual engagement had been taken solely by computer workers and this is attributable to the differences in their immediate working environment compared to branch or clerical bank staff. Moreover, the labour process within banking services call centres could be considered highly conducive to taking industrial action.

THE PARTNERSHIP DEAL IN CONTEXT

Within Barclays, the acknowledgement on the part of management of the potential for call centre staff to take such action resulted in the derecognition of Unifi (pre-merger) in most dedicated call centres. In this context, the partner-ship project at Barclays could represent an ‘about turn’ in the company’s employ-ment relations and according to Norman Haslam, Barclays’ employee relations director, marks ‘a move forward in industrial relations from the past difficult relationship and, at times, conflict’(IRS 1999). In place of the adversarial relation-ships that had characterised employment relations at the bank––culminating in national strikes by Barclays staff over changes to pay and grading structures in 1997––senior management began to recognise the need for change. Over the course of 1998, Barclays and the unions held a series of informal meetings to explore the opportunities for a partnership approach, recognising that ‘a positive working relationship is an essential ingredient for the future success of the business’(IRS 1999). By working together and exploring areas of common interest, the bank hopes to improve the working environment of its staff while delivering improved service to its customers. Barclays’ ‘new’ approach, therefore, promotes the idea that commercial success and better employee relations are not mutually exclu-sive and that partnership can achieve business objectives and promote the interests of staff. It is a mutual acknowledgement of ‘the unions’ recognition of Barclays’ right to take business decisions combined with our acknowledgement of theirs to challenge and influence these decisions [which] is pivotal to the partnership approach’ (IRS 1999). In essence, the partnership approach contains four main elements: • a set of partnership principles that underpin the collaborative approach,

• a three-year partnership pay deal, effective from 1 April 1999, covering the bank’s 50 000 clerical and managerial staff.

• the setting up of joint working parties to make recommendations on topics such as job security, equal opportunities, job evaluation, performance man-agement, flexible working, family-friendly policies and health and safety. • discussions on a new recognition and procedure agreement that will enshrine

a partnership approach to employee relations and provide for the appointment of jointly recognised union representatives.

UNIONISATION

The extent of unionisation within financial services call centres probably reflects the density of unionisation within the call centre sector generally. In common with WERS 98 (Cully et al. 1999) findings for workplaces in general, we may assume that smaller, stand-alone call centres are more likely to eschew recogni-tion of trade unions than larger call centres and workplaces, while larger call centres which are also part of a wider organisation are more likely to recognise trade unions and therefore have a significant union presence. Public sector work-places and call centres are more likely to have a union presence than private sector workplaces and older workplaces tend to be more unionised than younger workplaces. However, some large organisations, particularly those that are inwardly investing, such as MBNA, are determined to remain union free and may even export their anti-union ideology into the UK. Such companies com-monly adopt union substitution policies and practices in order to ensure that employees do not join trade unions. Within the banking sector in particular, call centres have been set up by major institutions, some of which such as Barclays have established collective bargaining arrangements in operation. Other institu-tions such as HSBC had selectively de-recognised trade unions mainly in its call centres, while still others such as MBNA have always remained union-free. Consequently, levels of union penetration within financial services, as with the call centre sector overall, still tend to vary considerably (IDS 1999; Bain & Taylor 1999).

The current situation with regard to union penetration and recognition, accord-ing to the IDS (2000) report dealaccord-ing with pay and conditions in call centres, is that around 44 per cent of call centres are unionised––which is a fair reflection of national union density. The report also confirms WERS findings that union recognition is more likely to occur in public sector call centres, the privatised utilities and within certain areas of the finance sector. In order to boost recruit-ment within the finance and communications sector Unifi and the telecoms union, Communication Workers Union (CWU), launched an initiative whereby mem-bers of both unions may seamlessly transfer union memmem-bership should they switch between finance and telecoms. The scheme, entitled ‘movin’ on’ is also intended to tackle the problem of movement between sectors and high turnover rates within call centres.

Union commitment

and has been largely neglected within the UK (Guest & Dewe 1991). This is somewhat surprising, particularly within the call centre context, since it could be argued that union commitment may be inversely correlated with organisa-tional commitment. Labour process theory suggests that a lack of organisaorganisa-tional commitment may generate individual ‘resistance’ which does not translate into collective ‘resistance’ (Knights & McCabe 1998). However, Bain and Taylor (1999) and Taylor and Bain (1999) at least imply that the call centre labour process and the experience of work as being ‘intensive, pressurised and frequently stress-ful’ together with a general dissatisfaction with management on the part of oper-ators concerning lack of career and promotion prospects and a failure to secure employee commitment generally, constitute important factors which determine employee receptivity towards unionisation. Bearing in mind the wide variation in the extent of unionisation across call centres, the main focus of Bain and Taylor’s work has been upon union recruitment strategies rather than retention and the generation of union commitment on the part of employees. The latter concerns have been examined in more detail by Waddington (1999) in relation to membership retention and trade union organisation within the banking sector.

Much of the research within the area of union commitment is based on Gordon et al.’s (1980) four-factor measure of commitment which comprise union loyalty (sense of pride and an awareness of the benefits of union membership), responsi-bility to the union(such as the extent to which members fulfil their basic obliga-tions to the union), willingness to work for the union (by participating in union activity beyond that normally expected of rank and file members) and belief in unionism (reflecting a general belief in the concept of trade unionism). While the debate dealing with union commitment is wide-ranging and incorporates the notion of ‘dual commitment’ which explores the possibility of both high com-mitment to employing organisation andtrade union, this paper makes reference to both the ‘union loyalty’ dimension where we contrast both ‘affective’ and ‘instrumental’ union commitment and the question of why people join unions.

Affective commitment concerns and reflects a sense of shared values, identity and pride in the union and is consistent with what Sverke and Sjoberg (1994) refer to as ‘value rationality-based commitment to the union’. On the other hand, instrumental commitment is based on the perceived benefits flowing from the union and described as ‘instrumental rationality-based commitment to the union’ (Sverke & Sjoberg 1994). Instrumental commitment is essentially based on self-interest through the satisfaction of relevant personal goals and is viewed as the extent to which the union is perceived to be effective in achieving certain valued goals. As such, this type of commitment is less ideologically oriented and more short-term than affective commitment. The two types of commitment are not necessarily mutually exclusive as both types can manifest themselves in individual union members. Hence, it could be argued that overall commitment will be stronger and more sustainable if it is primarily of an affective nature.

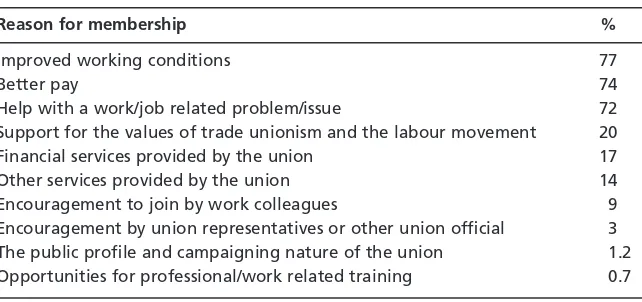

if I had a problem at work’, while 72 per cent gave ‘improved pay and condi-tions’ as a reason. A significant minority of members––14.8 per cent believed in trade unions and wanted to take part in union activities. The particular signifi-cance of these findings is that the traditional ‘collective’ reasons for joining and remaining in the union are in the ascendancy while other reasons such as finan-cial services (3.8 per cent), professional training (0.4 per cent) and membership services (7 per cent) are far less important and this suggests that membership retention is based on collective reasons rather than on individual services. Waddington’s findings also suggest that union recruitment strategies should go beyond the provision of union services in order to make the union attractive and re-focus upon the solidaristic and traditional collectivist issues.

THE RESEARCH CONTEXT

The research was undertaken at the Liverpool call centre of ‘Barclays Direct Loans Services’ (BDLS) which was formed in 1993 and which incorporated both ‘Barclayloan’ and ‘Mercantile Credit’ personal loan facilities. BDLS is a largely autonomous division of the Barclays Group and is accountable to it. BDLS provides ‘phone-a-loan’ and postal services to both Barclays and non-Barclays customers who can telephone BDLS to arrange a loan from 8AMto 11PMseven days a week. The main products that BDLS deal with are:

• Barclayloan which is marketed to both Barclays and non-Barclays customers and which accounted for 25 per cent of the company’s business in 1998; • Masterloan which is marketed to existing Barclaycard customers and which

constituted 52 per cent of BDLS’s business in 1998;

• Mercantile Credit which is marketed to non-Barclays customers and which accounted for 15 per cent of business.

At the time the research was undertaken there were around 500 employees com-prising teams and team leaders within BDLS, which itself comprises two main departments called Risk and Total Service Unit (TSU). Risk deals with the col-lection of overdue loans while TSU handles loan applications. Work in both departments is organised on a team basis: Risk comprises 13 teams, each con-taining up to 15 team members and one team leader and TSU has 24 teams each comprising up to 11 team members and one team leader. Work is closely moni-tored as evidenced by the nature of the targets set for agents as illustrated below for the Risk department.

• Target call length is 330 seconds which includes call time, updating customer records and typing details of call.

• Target unavailable time is 5 per cent of aggregate shift time. Hence agents working a seven hour shift are targeted to be available for accepting calls for six hours 35 minutes.

• Target promise kept ratio is 63 per cent. The Risk department is mainly con-cerned with collection of overdue amounts and advisors are targeted on how successful they are in collecting these amounts.

matched with the typewritten notes to see whether the conversation matches up. Advisors are normally targeted to achieve less than a 5 per cent error rate. • Advisors are required to put forward ideas that may lead to a reduction in unnecessary costs, the target being to achieve 40 points on the criteria set out. In addition, productivity statistics for every agent are immediately available to both management and agent, although it is usual to consider these during monthly performance reviews and quarterly performance appraisals. Should agents fall below the set target for one of the productivity measures, then one of their appraisal objectives will be to get back on target for whatever they have fallen behind on. The extent to which objectives are met also determines individualised performance-related-pay via the performance management appraisal system.

During the period of the survey, Barclays, the parent company, announced 6000 job cuts nationally and major restructuring plans which included BDLS Risk operations transferring to Manchester in November 1999 as part of a ‘rational-isation’ programme aimed at merging the Risk collections department with other Barclays collections operations such as the Branch Recovery Unit. While some Liverpool based staff would henceforth need to travel to Manchester (without any travel expenses) in order to keep their jobs, one third of the Risk department workforce have refused to relocate and have applied for voluntary redundancy

Three hundred agents who were randomly selected from both TSU and Risk departments, together with team leaders, received a questionnaire of which 250 were returned. The questionnaires were augmented by a series of interviews with the management team at BDLS.

SURVEY RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The following aspects relating to the survey were considered.

Workplace Issues

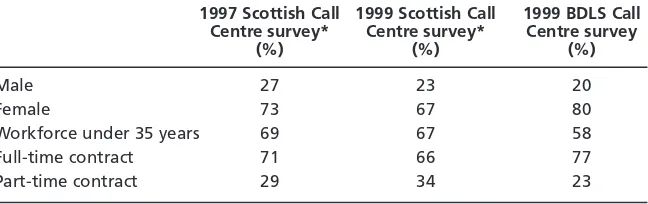

Information obtained concerning the gender composition of the workforce, the nature of the employment contract and the age of the workforce yielded the data shown in Table 2.

Taking the data of Bain and Taylor as comparator, the figures for BDLS con-firm the view that the call centre workforce is mainly female, relatively young

Table 2 Gender composition, employment contract and age of workforce

1997 Scottish Call 1999 Scottish Call 1999 BDLS Call Centre survey* Centre survey* Centre survey

(%) (%) (%)

Male 27 23 20

Female 73 67 80

Workforce under 35 years 69 67 58

Full-time contract 71 66 77

Part-time contract 29 34 23

and mainly on full-time contracts, although the proportion of part-time contracts is increasing. Reliable data concerning labour turnover or ‘churn’ was not avail-able. BDLS’s HR Department cited turnover and sickness absence rates for 1998 of 6 per cent and 4 per cent respectively, but interview comments tended to reveal that turnover and sickness absence were serious problems. One team leader, for example, commented:

Overall, staff in the various departments of BDLS are given jobs which are both monotonous and demotivating. If jobs were more varied it would help keep people interested. Presently, staff sickness due to stress is at an all-time high and I feel this is a result of working in a call centre environment. Staff recognition for hard work also needs improvement.

In similar vein, a sales and service advisor stated:

Staff morale is at an all-time low. I have been here for three years and have never known so much sickness and many colleagues are looking for jobs outside this company. There are many good staff here and if things continue, BDLS is likely to lose the lot.

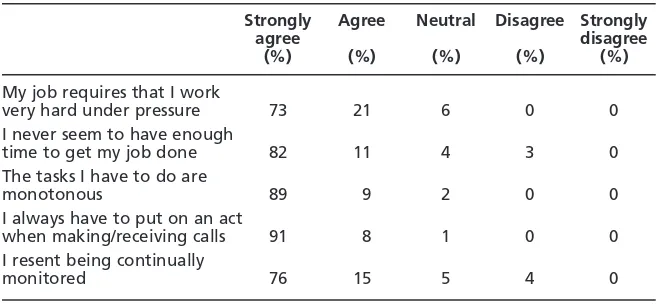

Agents’ perceptions of their job were largely negative. Most respondents indicated that their work was highly pressurised, intensive and monotonous and identified elements of their work which contributed to this. Table 3 shows the extent of agent dissatisfaction.

These negative perceptions tend to confirm the prevailing view based on admit-tedly limited survey research that call centre work is ‘intensive, pressurised and frequently stressful’ (Bain & Taylor 1999; Taylor & Bain 1999). Work pressure centred upon the issue of targets as the following quotes illustrate:

The issue of targets is never ending, we either do not meet the targets set out or we shoot ourselves in the foot by meeting them and then the targets are raised for the following year (Risk advisor).

Table 3 Agent perceptions of their job

Strongly Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly

agree disagree

(%) (%) (%) (%) (%)

My job requires that I work

very hard under pressure 73 21 6 0 0 I never seem to have enough

time to get my job done 82 11 4 3 0 The tasks I have to do are

monotonous 89 9 2 0 0

I always have to put on an act

when making/receiving calls 91 8 1 0 0 I resent being continually

I feel I always maintain a high standard of work but sometimes targets are not met [not] through lack of hard work and dedication but due to particular calls. You can’t put targets on each customer. One day, your calls may take three minutes and no call work is required. Another day, your calls may take longer and you have a diffi-cult query to deal with. As a consequence, your daily figures look poor but the fact is that you have worked extremely hard to ensure that a query has been resolved in a satisfactory manner (Sales and Service Advisor).

I understand all businesses have targets but I feel too much emphasis is placed on this in our department at the expense of employee job satisfaction (Risk Advisor).

Other comments concern the extent of monitoring and surveillance, the monot-onous and routine nature of the job, the ‘emotional labour’ context (Hochschild 1983), and team working.

On monitoring and teamwork:

BDLS emphasise the importance of being a ‘team player’. The reality is that we don’t have any time for teamwork and bonding as a team. As soon as we walk into work, we are monitored from being available for calls to handling calls in a correct manner. Life at BDLS is governed by this black box (referring to the Rockwell computer monitoring system: Risk Advisor).

As colleagues we never get to speak to each other. Even break times are difficult because it could be five of us on break together and we have only fifteen minutes. If someone wants to tell us some news that will probably take about five minutes, we can’t talk at once so very often, you never get to share things with colleagues (Sales and Service Advisor).

On emotional labour:

You always have to ‘sweet talk’ the customer and you can never be yourself. I remem-ber reading something by Sartre on waiting in a restaurant where the waiter plays mental games with his customers because the job is so mind-numbingly boring–– acting in ‘bad faith’ I think it was. It’s exactly the same in this job. I commit myself with difficulty especially with difficult customers (Service and Sales Advisor).

In essence, therefore, along most dimensions of control, call centre work at BDLS is seen as oppressive by a majority of respondents. However, it would be erroneous to assume that electronic surveillance and monitoring are the only elements of control worthy of mention (Smith & Thompson 1998). Timed breaks, call reaction times, target setting and the sheer pace of work operations all con-tribute towards the climate of control and the Taylorisation of the BDLS call centre labour process. Our survey indicates that the degree of control over the labour process is inversely correlated with perceptions of the degree of influence advisors had over their work. When asked about the amount of influence employ-ees felt they had over their jobs, 72 per cent of respondents indicated that they had little or no influence or discretion over their work operations, which is unsurprising when other elements of control referred to above, are taken into consideration.

corresponds with findings from other studies (Clark 1996; Spector 1997). Older agents new to the job tended to be more positive in their views of their work situation than younger ones. However with regard to length of service, the longer an agent had been with BDLS, the more negative were her/his job and work related attitudes. One interesting finding concerns the number of hours worked: part-time employees, and particularly those working less than ten hours a week, were more likely than full-time employees to be satisfied with at least some aspects of their work and this corresponds with similar findings from Cully et al.’s (1999) WERS survey. The variation in respondent’s views across the age, length of service and hours of work criteria was attributed largely to the relative absence of any career progression and promotion opportunities despite the high rate of labour turnover (IRS 1999).

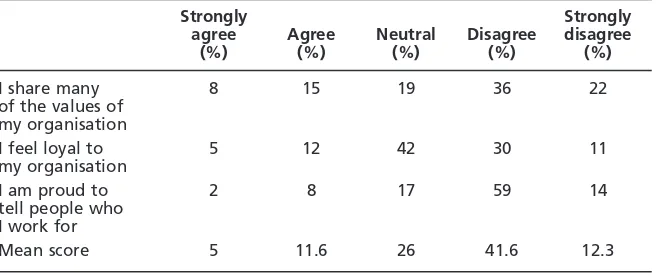

The final work-related issue to be considered concerned the extent to which agents identified with BDLS/Barclays as an organisation. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Table 4 reveals generally low levels of loyalty to the employing organ-isation. Agents were asked about whether they agreed or disagreed with the fol-lowing statements:

• I share many of the values of my organisation. • I feel loyal to my organisation.

• I am proud to tell people who I work for.

Taken together, these statements could be regarded as a measure of organisational commitment, although no attempt is made in this paper to compare the results of this measure with those used to gauge trade union commitment.

Low levels of commitment within BDLS tend to reflect the largely negative views held about the labour process and work issues generally. These measures (Table 4) are borne out by statements gleaned from interviews with Risk and Customer Services Advisors. Typical amongst these was:

You can throw loyalty out of the window when you are never consulted about the work or what the company does (Service Advisor).

Table 4 Indicators of employee commitment

Strongly Strongly

agree Agree Neutral Disagree disagree

(%) (%) (%) (%) (%)

I share many 8 15 19 36 22

of the values of my organisation

I feel loyal to 5 12 42 30 11 my organisation

I am proud to 2 8 17 59 14

tell people who I work for

Commitment to the Union

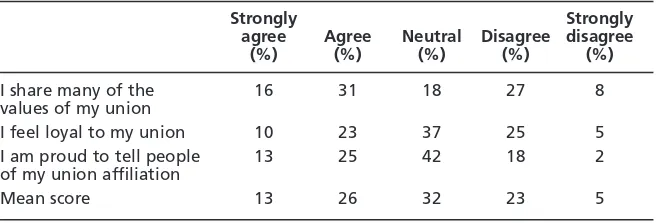

It was not, however, the main intention of this paper to consider organisational commitment in any detail. Issues such as the relationship between various indices of organisational commitment, work and job involvement and group commit-ment, and their positive and negative outcomes relating to, for example, work performance and levels of absenteeism and turnover are the concern of further research. More importantly for the purposes of this research, a re-phrased ques-tion was asked which yielded responses concerning commitment to the union, thereby enabling some comparisons to be made concerning the relationship, if any, between organisational and union commitment. The results are shown in Table 5.

The data reveal that a significant minority of respondents (39 per cent) have an overall strong commitment to the union, which contrasts with 16.6 per cent of respondents in the corresponding organisational commitment categories. Perhaps more importantly, almost 54 per cent of respondents had low organ-isational commitment measures as contrasted with 28 per cent who had corres-pondingly low union commitment measures.

Explanations for this situation could stem from the ‘dual commitment’ notion (Angle & Perry 1986; Magenau et al.1988; Sverke & Sjoberg 1994). In essence, ‘dual commitment’ (measures of both organisation and union allegiance) may be interpreted in one of two ways. Firstly, union and organisation values may be perceived as part of a holistic work milieu and are more likely to be congruent with each other (for example congruence with high organisational commitment and high union commitment). Hence we could argue that when workplace employment relations (as an independent variable) are characterised by cooper-ation, the more likely it is that commitment to both organisation and union is relatively high. On the other hand, should employment relations be adversarial, then commitment may be incongruent (low organisational and relatively high union commitment). Secondly, it could be assumed (Magenau et al. 1988) that union and organisational commitment are themselves separate variables, each influenced to varying degrees by different factors. For example, favourable perceptions of the job and workplace may contribute to relatively high organ-isational commitment levels, while a favourable evaluation of the union’s per-formance may determine the extent of union commitment. The debate needs to

Table 5 Indicators of union commitment

Strongly Strongly

agree Agree Neutral Disagree disagree

(%) (%) (%) (%) (%)

I share many of the 16 31 18 27 8 values of my union

I feel loyal to my union 10 23 37 25 5 I am proud to tell people 13 25 42 18 2 of my union affiliation

be refined and expanded upon and is beyond the scope of this paper. At this stage, however, we could tentatively suggest that negative views of the workplace have given rise to low organisational commitment levels. By the same token we could assume that respondent views of the performance of their union, reasons given for joining and the issues regarded as important for the union to pursue are all indicators of commitment (or the lack of commitment) to the union. To this end, we are not only concerned to identify the general level of commitment (see Table 4), but also the nature of that commitment on an instrumental–affective scale.

Responses were elicited concerning agents’ reasons for joining Unifi in the first place. Agents were asked to identify three main reasons, and these were then ranked in order of importance as shown in Table 6.

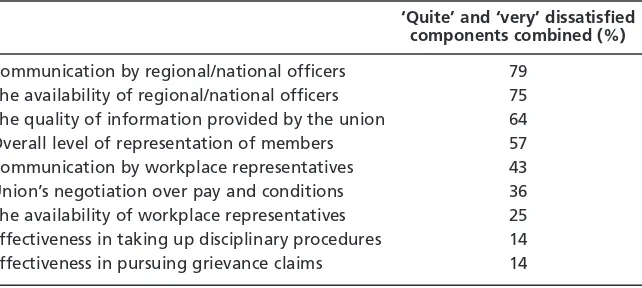

Affective commitment, which is indicated by a perception and sense of shared values, identity and pride in the union was strongly identified in Table 5 and also reinforced by significant support for trade union and labour movement values (Table 6). However, as was to be expected, instrumental commitment on the basis of perceived benefits such as improvements in pay and working conditions was considerably higher. What is somewhat surprising is the relatively insignificant role played by the union and its representatives at area/regional and workplace levels in influencing decisions to become a union member. Further probing con-cerning the effectiveness of union representation over a variety of issues revealed a high proportion of respondents who felt that the union was not successful in representing any of the issues identified in Table 7. The reasons for this state of affairs according to a sample of agents who were interviewed relate to important events that took place in the recent past and the current situation of uncertainty, and this is explained in more detail below.

In 1997, Barclays announced an integrated new method of appraisal, grading and pay which included a move towards a performance management system and which ultimately rated people on a four-item scale as one of ‘exceed’, ‘met’, ‘fallen short’, or ‘unacceptable’. Thirteen grades were reduced to seven and salary became linked to performance rather than being based on length of service via annual

Table 6 Reasons for joining Unifi

Reason for membership %

Improved working conditions 77

Better pay 74

pay rises. In addition, Barclays proposed introducing salary scales built around a ‘bar’ salary, which, the bank argued, ‘would be used to ensure that everyone’s salary would be competitive’ (Senior HR manager). One implication of the ‘bar’ would be that a majority of employees whose salaries were above the ‘bar’ would not be guaranteed a salary increase should their performance figures merely ‘meet’ (as opposed to ‘exceed’) their agreed targets. Although Barclays withdrew the ‘bar’ proposal after industrial action, opinion was divided as to its effectiveness. This, and the months of procrastination by Unifi prior to the action being called, together with the lack of consultation with the membership severely dented the confidence which the membership had in the union.

Arguably, responses were also influenced by the announcement that the ‘Risk’ operation would be moving to Manchester with the implication of considerable redundancies. The perceived weakness of the union in attempting to influence BDLS to change its decision were expressed during interviews. The following statements were typical:

I am very disappointed with the representation from the union head office, espe-cially our jobs being moved to Manchester (Female Risk Advisor).

Presently, I have little faith in the union and feel that they have had no success (Female Risk Advisor).

A related issue concerns agent satisfaction with the performance of union repres-entation, particularly at national level. Table 8 reveals high levels of dissatisfac-tion with representadissatisfac-tion at this level––as one team manager put it:

I feel that internal representatives are trying to do a good job but they are left very much to their own devices by the full time regional/national representatives who seem very wary about getting involved directly with issues. I therefore see staff representatives becoming overburdened and stressed at the unfair work load placed upon them.

Table 7 Success in Representing Union Members

Union ‘most successful’ % Union ‘least successful’ %

None 36 Don’t know 28

Removing ‘bar’ from pay 32 Pay and grading 25 Don’t know 21 Move to Manchester 18 Healthcare 12 Performance management 14 Sickness pay over 6 months 12 Redundancies/job losses 14 Improved performance management 8 Keeping staff informed 10 Reinstated breaks 4 Fighting for displaced staff 10 Maternity rights 4 Working conditions 10

Grading 2 Flexible working 4

This view was supported by a fellow colleague:

I have approached the union about my grievance. Workplace representatives have been very supportive but regional officers have been of no help. Management and unions are being allowed by the bank to flout and break the rules to meet their own needs.

Strong dissatisfaction was also voiced over the quality of information provided by the union with one Sales and Services Advisor commenting:

Too much literature is sent by the union at exorbitant cost and much of it is not relevant to our work needs. I am sure it could be scaled down and made more precise.

Attitudes concerning representation at the workplace tended to be more posi-tive, with 41 per cent of respondents having frequent contact with workplace union representatives, and a further 27 per cent having occasional contact. This may be explained, at least partly, by the concern about, and growing mistrust of, BDLS and the imminent relocation move to Manchester. To a large extent, suspicions of the motives of BDLS are also directed at regional and national levels of Unifi itself, and in recent months suspicions and distrust of both Unifi and Barclays has been exacerbated by the newly created ‘partnership ethos’ (see above).

PRESCRIPTION FOR CHANGE?

The terms ‘sweatshop’, ‘electronic panopticon’ and the like tend to exaggerate the reality of the call centre labour process and employment relationship. To be sure, agents’ work is often stressful and monotonous, but to describe the entire call centre labour process and work situation through the use of metaphorical analogy is unhelpful. In essence, our research at BDLS has uncovered a labour process which exacerbates the ‘Taylorisation’ of white-collar work (see also Taylor & Bain 1999) with its control, monitoring and surveillance mechanisms. Moreover, we have established that organisational commitment amongst BDLS

Table 8 Satisfaction with Unifi Performance

‘Quite’ and ‘very’ dissatisfied components combined (%)

agents is particularly low––no doubt partly due to the nature of call centre work and partly stemming from factors such as pay, type of contract and lack of career prospects. The research also revealed considerable disappointment with Unifi in relation to a number of unresolved issues despite considerable identification with the aims of trade unionism generally. Major concerns focus upon a number of issues identified below.

Pay

In common with the vast majority of call centres within financial services (IDS 2000), the pay levels of BDLS agents, excluding overtime and bonuses, is low in comparison with other bank and insurance sector staff and average gross annual earnings of full-time employees generally (the disparity with the latter category is often by as much as 59 per cent, TUC 2001). Pay related to performance either on an individual or on a team basis is an increasingly important component of the remuneration package, reflecting the greater emphasis which banks and insur-ance companies are giving to selling, as opposed simply to customer service, in their telephone relationships with customers.

Hours of work and shift patterns

Direct banking and insurance services using call centres are often open for busi-ness twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. As a result, flexible and part-time working patterns proliferate within BDLS and most call centres with evening/weekend work being treated no differently from other working hours.

Employment status and rights

Within banking and insurance, in common with most other sectors, varying pro-portions of agency staff work alongside full-time and/or permanent part-time employees. However, the use of agency staff was being phased out in BDLS, and while this is not typical of many call centres in the sector, there is, nevertheless, some evidence to suggest that some organisations such as the Co-operative Bank were lessening their dependency upon such employees by agreement with Unifi. Outsourcing remains a problem for most trade unions within the finance sector and while some organisations, including Barclays, have expressed a commitment within the context of ‘partnership’ for all call centres to stay ‘in house’, this prac-tice and is set to increase within Europe (Datamonitor 2000).

Health and safety issues

CONCLUSION: NOT QUITE A SWEATSHOP?

The survey results confirm the prevailing view of call centres as being rather oppressive environments to work in. This is not surprising as Barclays, in attempt-ing to regain competitive advantage over other bankattempt-ing institutions in recent years, has intensified work through increasing productivity targets, and facilitated management control through the introduction of new surveillance and ‘dialler’ technologies despite attempts to involve the trade union nationally in a ‘part-nership’ exercise. It is hardly surprising, therefore that the ‘sweatshop’ image persists. Agents regarded their work operations as being highly repetitive and standardised, while management were criticised for reinforcing the already heavy surveillance of work operations, thereby adding to the control element. Agents noted that both discretion and autonomy concerning the performance of their jobs and tasks were severely curtailed by various work intensification methods facilitated by new technology. The survey results also find support for the view that there is a vast chasm between the company rhetoric which espouses HRM ‘values’––albeit under the guise of ‘partnership’––such as the promotion of employees’ organisational ‘commitment’ and ‘empowerment’, and the reality of being under constant scrutiny to ensure ‘zero errors’ and the deployment of standardised telephony techniques which inter alia engender low levels of organ-isational commitment. Unfortunately, resorting to union representatives, and expecting them to act effectively concerning agents’ grievances often did not have the desired effect, although in general, union commitment levels were consider-ably higher than those displayed for the employing organisation. The research, therefore, indicates that there is still much to be done within BDLS and within finance call centres generally by both employers and trade unions. Employers need to ensure that the ‘sweatshop’ image of call centres is banished by dealing with the issues raised above and in this paper generally, while trade unions need to refine their recruitment strategies and deal effectively with call centre-related grievances.

REFERENCES

Angle HL, Perry JL (1986) Dual commitment and labor–management relationship climates.

Academy of Management Journal29(1), 31–50.

Bain P, Taylor P (1999) Employee relations, worker attitudes and trade union representation in call centres. Presented to the 17th International Labour Process Conference,University of London. Baldry C, Bain P, Taylor P (1998) Bright Satanic Offices: Intensification, Control and Team Taylorisation. In: Thompson P, Warhurst C, eds, Workplaces of the Future.London: Macmillan. Bibby A (2001) Organising in Call Centres. www.eclipse.co.uk

Blackburn RM, Prandy K (1965) White collar unionisation: a conceptual framework. British Journal of Sociology16, 49–66.

Clark A (1996) Job satisfaction in Britain. British Journal of Industrial Relations34(2), 189–217. Cully M, Woodland S, O’Reilly A, Dix G (1999) Britain at Work.London: Routledge. Datamonitor (1998) Call Centres in Europe. London: Datamonitor.

Datamonitor (2000) Call Centres in Europe.London: Datamonitor.

Frenkel S, Korcynski M, Shire K, Tam M (1998) Beyond bureaucracy? Work organisation in call centres. The International Journal of Human Resource Management9(6), 957–79.

Gall G (1997) Developments in trade unionism in the financial sector in Britain. Work, Employment and Society11(2), 219–235.

Garson B (1988) The Electronic Sweatshop: How Computers Are Transforming the Office of the Future into the Factory of the Past. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Gordon ME, Philpott JW, Burt RE, Thompson CA, Spiller WE (1980) Commitment to the union: Development of a measure and examination of its correlates. Journal of Applied Psychology65(4), 479–99.

Guest D, Dewe P (1991) Company or trade union: which wins workers’ alliegance? A study of commitment in the UK electronics industry. British Journal of Industrial Relations29(1), 75–96. Hochschild AR (1983) The Managed Heart: Commercialisation of Human Feeling. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

IDS (1999) Pay and Conditions in Call Centres.London: Incomes Data Services. IDS (2000) Pay and Conditions in Call Centres.London: Incomes Data Services.

IRS Employment Trends (1999) Women in teleservices frustrated by routine. Industrial Relations Services No. 675, London.

IRS (1999) Partnership agreement––Barclays Bank and UNIFI.

Kelloway EK, Catano VM, Southwell RR (1992) The construct validity of union commitment: Development and dimensionality of a shorter scale. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology65, 197–21.

Kelly J (1996) Union militancy and social partnership. In: Ackers P, Smith C, Smith P, eds, The New Workplace and Trade Unionism. London: Routledge.

Kelly J (1998) Rethinking Industrial Relations. London: Routledge.

Knights D, McCabe D (1998) What happens when the phone goes wild? Staff stress and spaces for escape in a BPR telephone banking work regime. Journal of Management Studies35(2), 34–57. Lockwood D (1958) The Blackcoated Worker: a Study in Class Consciousness. London: Allen and Unwin. Magenau JM, Martin JE, Peterson MM (1988) Dual and unilateral commitment among stewards

and rank-and-file members. Academy of Management Journal31(2), 359–76. Mitial (1999) 1999 UK and Eire Call Centre Study. London: Mitial Research. Oakland J (1989) Total Quality Management. Oxford: Heinemann.

OTR (Organisation and Technology Research) (2001) Developments in Call Centre Technology.

London: OTR.

Piore MJ, Sabel CF (1984) The Second Industrial Divide.New York: Basic Books.

Smith C, Thompson P (1998) Re-evaluating the labour process debate. Economic and Industrial Democracy19(4), 232–247.

Spector C (1997) Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes and Consequences.London: Sage. Sverke M, Sjoberg A (1994) Dual commitment to company and union in Sweden: An

examina-tion of predictors and taxanomic split methods. Economic and Industrial Democracy15, 531–64. Taylor P, Bain P (1999) An assembly line in the head: work and employee relations in the call

centre. Industrial Relations Journal30(2), 101–117.

Thacker JW, Fields MW, Tetrick LE (1989) The factor structure of union commitment: An appli-cation of confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology74(2), 228–32.

TUC (2001) It’s Your Call.London: Trade Union Congress.

UNIFI (2000) UNIFI and Barclays sign Partnership Agreement. Media News April 28.

Waddington J (1999) Membership retention and trade union organisation: The case of unions in bank-ing. Data presented at UNIFI Inaugural Congress, Blackpool.

Waddington J, Whitson C (1997) Why do people join unions in a period of membership decline?