Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cimw20

Download by: [UQ Library] Date: 27 January 2016, At: 15:36

Indonesia and the Malay World

ISSN: 1363-9811 (Print) 1469-8382 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cimw20

Negotiating cultural constraints: strategic

decision-making by widows and divorcees (janda)

in contemporary Bali

I Nyoman Darma Putra & Helen Creese

To cite this article: I Nyoman Darma Putra & Helen Creese (2016) Negotiating cultural

constraints: strategic decision-making by widows and divorcees (janda) in contemporary Bali, Indonesia and the Malay World, 44:128, 104-122, DOI: 10.1080/13639811.2015.1100869

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2015.1100869

Published online: 07 Dec 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 13

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Negotiating cultural constraints: strategic decision-making

by widows and divorcees (

janda

) in contemporary Bali

I Nyoman Darma Putra and Helen CreeseABSTRACT

This article discusses the strategies deployed by widows and divorcees (janda) in negotiating cultural constraints and social stigmatisation in contemporary Bali. In Balinese patriarchal society, women are disadvantaged in terms of their access to employment and commonly earn less than men. When a marriage ends, Balinese widows and divorcees not only lose their partners but also an important source of family income. Janda may need to take on additional burdens in supporting themselves and their families and are therefore economically vulnerable. In addition, janda are often considered to be sexually available, may be the target of men’s sexual advances and thus become a frequent source of gossip. The dual state-village administrative system further complicates divorce and remarriage within Balinese patriarchal society. In order to understand how Balinese janda cope with these social and cultural constraints, this article focuses on the contrasting life histories of threejanda. Deploying Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of economic, cultural, social and symbolic capital, the analysis demonstrates that access to multiple forms of capital plays an important role in enabling Balinesejandato make their lives bearable and manageable. With adequate access to economic resources, janda can not only demonstrate their independence and ability to support their children, but also are able to meet their social and religious obligations. In this way they can maintain their respectability and social acceptance within their local communities. These findings contribute to a wider and more complex picture of the life of Balinesejanda.

As elsewhere in Indonesia, in Bali the end of a marriage may signal major changes in status and personal relationships for women, leaving them economically vulnerable and poten-tially open to stigma. In spite of a long history of formal legal protection (Creese2016, this issue; Parker2016, this issue) and official national rhetoric about women’s inherent equal-ity and‘value,’within Bali’s patriarchal social system,janda–widows and divorcees–are disadvantaged in culturally specific ways that may exacerbate the burden of their single status.1Significant local factors in decision-making following a divorce or the death of a

© 2015 Editors, Indonesia and the Malay World

1

Janda(Balinesebalu) is an Indonesian term that refers to both widows and divorcees, sometimes differentiated asjanda matiandjanda cerairespectively. In order to situate this article in the context of this special issue onjandaand stigma-tisation in Indonesia more generally, we prefer the termjandaover its Balinese equivalent,balu, because the Balinese VOL. 44, NO. 128, 104–122

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2015.1100869

spouse, which will be explored more fully below, include Bali’s patrilineal descent system and virilocal residence patterns that may force divorced and widowed women to leave the marital home and extended family networks. Many experience alienation and exclusion from religious and communal life and may risk losing access to their children who typi-cally remain in the father’s family. Children who move away from their father’s compound to live with their mother when the parents are divorced or their mother widowed must still perform all their own life cycle ceremonies and religious obligations within the patrilinial familial environment. When a marriage ends, whether through divorce or the death of a spouse, a core concern for Balinesejandaremains the importance of ensuring their chil-dren remain fully integrated into their former partner’s family lineage. This concern may necessitate maintaining strained personal relationships with a former partner or his extended family over many years. Stigmatisation and perceptions of sexual availability and promiscuity may mean that Balinesejandaalso face similar burdens to those reported in the case studies from across the archipelago documented elsewhere in this special issue (Mahy et al.2016; Parker et al.2016). Women who are widowed or divorced may also have to negotiate complex caste boundaries that may be transgressed when new relationships are formed and experience difficulties in meeting their religious and social obligations. Although the economic, social and cultural consequences of choosing to leave a marriage often seem insurmountable and may restrict choice, many Balinese women make that decision, develop strategies to forge new and meaningful lives and rebuild the social and cultural capital that the end of a marriage may have diluted.

In spite of the vast scholarly literature on Balinese society and culture, almost no atten-tion has been paid to the life-experiences ofjandain the community. Issues surrounding jandamay feature in contemporary studies ofadatlaw, which remains a potent force in the regulation of Balinese social relationships, but the discussion is primarily in relation to their rights, or rather their unequal rights, to inheritance (Panetja1989; Sukranatha2002; Windia2014; Creese2016). Despite widespread regional variation, the position ofjandais always marginal before the (adat) law and exacerbates the economic and social burdens thatjanda face. Apart from some incidental attention to the challenges faced byjanda in Jennaway’s study of the lives of rural village women in north Bali (2002), only one recent study (Margi2007), set in a strikingly similar environment to that of Jennaway’s

field site a decade earlier, focuses on the life experiences of jandain a rural village in north Bali. Margi considers the experiences of 19 divorced women who have returned to their natal homes as single women in terms of the measure of empathy and social phi-lanthropy (kedermawanan sosial) extended to them by their natal families and their communities.

In this article, we seek to contribute to thefield by presenting the life-histories of three Balinese janda who, through personal choice or circumstances, have successfully navi-gated Balinese cultural and social constraints to rebuild their lives after widowhood and divorce. These women are not, of course, representative of the experiences of all Balinese janda, but they, nevertheless, exemplify the challenges faced by women following the end of a marital relationship. Their diverse stories reflect their individual experiences and strat-egies as they negotiate their economic, socio-cultural and religious identities within

termbaludoes not differentiate gender and is applied equally to men who are divorced or widowed. Moreover, the Indonesian wordjandais in common use in Bali.

Balinese society. Two of these life-histories are autobiographical and are based on recent interviews carried out in 2013–2014 by Darma Putra. Thefirst story focuses on Musti, now 65 years of age, who has been both widowed and divorced, and the second on Oki, a younger divorcee, now 47, who has remained single. The third case study, the story of Tutik, is biographical and draws on collective family memory through a series of inter-views with members of her extended family. Tutik, ajandawhose first husband disap-peared during the anti-communist violence of 1965–1966, later remarried and divorced. We have included Tutik’s story to illuminate the propensity for stigmatisation to endure even after the death of thejandaherself. All personal names used in this article are pseudonyms.

Our analysis, follows the frames of reference utilised by Parker et al. (2016) and draws on Bourdieu’s concept of different forms of capital (1977; 1986) to demonstrate how Balinese janda are able to exercise agency by mobilising support from their families and communities in ways that allow them to accumulate, expend and negotiate the various forms of capital – economic, social, cultural and symbolic. We extend the concept of ‘symbolic capital’ still further in the Balinese context to indicate not simply ‘respectability of janda’ but to denote the reintegration of janda into the Bali-nese adat community, a core social and religious relationship that the end of a mar-riage may have fractured. By accessing multiple forms of capital, individual janda are able to recoup their status as productive and active members of these communities. Moreover, these strategies enable them to avert debilitating stigmatisation by creating respectability as a form of honour. As in the examples discussed elsewhere in this special issue, it is possible for Balinese janda to overcome stigma and suspicion through the acquisition and expenditure of various forms of capital over time. Before turning to our case studies, we provide a brief overview of some broader aspects of Balinese social organisation that provide the arena in which these experiences play out. This background information will highlight the specific cultural context in which the janda to be described below act and make decisions when their marital relationships end.

Administrative dualism− thedesa adatanddesa dinas

In common with other provinces in Indonesia, the lowest administrative level in Bali is the village.2Bali has a longstanding dual administrative system, dating back to the colonial period, that separates civil administration in the desa dinas from social and cultural affairs in thedesa adat (desa pakraman; Warren 2003).3This administrative dualism is a legacy of the Dutch mission to restore and preserve ‘authentic Bali’. It was founded on a view of village society as the locus of the‘original’Bali and as fundamentally religious in character (Liefrinck1927: 281, 285). An administrative system was implemented that severed religion and culture from more worldly matters of politics and administration (Schulte Nordholt 1996: 240–3). Today, the desa dinas and desa adat comprise a number of local neighbourhood wards or banjar with complementary but distinct

2

Despite its rural connotations in English, thedesaor village also refers to residential sectors in urban areas.

3In 2014, the central government issued a new law, Village Regulation No. 6/2014, which will recognise only one village

administrative unit. The law is due to come into effect in 2015. Balinese have indicated a strong preference for retaining the current dual system.

functions and separate heads at each level.4Thedesa dinashas responsibility for all civil regulation including the issuing of identity cards, birth and marriage certificates and so on. All Balinese must be registered as members of adesa dinas, but Hindu Balinese, compris-ing 83.5% of Bali’s population according to the 2010 National Population Census, must register in both thedesa dinasanddesa adat.

For practical purposes, Balinese may move betweendesa dinasaffiliations in accord-ance with their place of residence and employment but will normally retain lifetime mem-bership of theirdesa adat. For men, theirdesa adatis normally the village into which they are born; for women at marriage, it becomes that of their husband’s family, with significant consequences for women who move away after they are widowed or divorced. All members are required to provide material support and voluntary service to the desa adat for communal religious and social activity and Balinese who no longer reside in their village return there for life-cycle rituals and for the frequent, significant temple fes-tivals and religious observations. Thedesa adathas formal administrative status but its real power lies in its oversight of alladatconcerns, including matters relating to the validation of marriages and divorces. Since the Reformation period in Indonesia, the symbolic power and authority of thedesa adathave increased significantly not only because of the general decentralisation of governance across Indonesia but also because of the rise of a spirited and resilient Balinese regional identity that is reflected in the local Ajeg Bali (Bali Stands Strong) movement. This sometimes ulconservative valorisation of Balinese tra-ditional values and of Bali’s religious and cultural distinctiveness has played out in popular discourse and media and for over a decade now has been, and remains, a powerful force in shaping community attitudes and values (Allen and Palermo2005; Schulte Nordholt2007; Lewis and Lewis2009; Putra and Creese2012). Thedesa adathas the responsibility to safe-guard the community against both internal and external negative influences and threats and has become the front line for guarding against the destruction of Balinese religion and culture. Both within and outside thedesa adatthere has been a focus on the appli-cation ofadatlaw (hukum adat), with the colonial documentation discussed in the com-panion article on legal processes in this issue (Creese2016), particularly Korn’sAdatrecht volume (1932) again providing authoritative definitions of Balinese adat for the 21st century (see, for example, Panetja1989; Windia2014).

Adatmarriage and divorce practices in Bali

Under Indonesia’s Marriage Law 1974, a marriage is legal if it is performed in accordance with the laws of the couple’s religion. For Balinese Hindus, marriage therefore requires the completion of specificadat rituals that reflect Balinese patrilineal kinship and virilocal residence patterns. As part of adat law, the bride must perform a mapamit or leave-taking ritual at her family temples, as a symbolic gesture to inform the ancestors that she will leave the house and be integrated into her partner’s family compound and family (Pitana1997: 95–6). In a simple wedding ceremony (masakapan) performed in the husband’s compound temple, the woman is presented to his ancestors and accepted by them as a member of their kin group. To validate the marriage underadat law, the

4The lowest level of administration is the

banjar. Thebanjar dinasis headed by thekepala lingkunganand thebanjar adat

by theklian. Above them sit the village level heads, thelurah(in urban areas) orkepala desa(in rural areas) of the admin-istrativedesa dinasand thebandesaof thedesa adat.

heads of thebanjar dinasandbanjar adatof both the bride and groom must witness the rituals. The central purpose of these rituals is to hand over the bride symbolically to her husband’s ancestors and family. In a series of parallel ceremonies, the heads of the two natal banjar (dinas and adat) release the bride to their counterparts in the husband’s banjarwho accept her into her newbanjar. The head of the groom’sbanjar adatthen announces the marriage in the following monthly banjar meeting. Although they do not always attend the rituals, the desa-level heads of both parties, the two lurah and bandesa, must witness the necessary certificates thus bringing the total number of official administrative officials involved to eight. The adat ceremonies usually precede formal administrative registration with the desa dinas, which is responsible for organising the paperwork necessary for the issuing of the marriage certificate by the district-level govern-ment office.

Divorce is a far more muted affair than marriage. The couple report their intention to the twoklian. After a separation period of three months, a certificate of divorce (surat keterangan cerai), signed by the heads of both the desa adat and the desa dinas, can then be issued without further recourse to civil procedures (Margi 2007: 131–2). Nevertheless, at the end of a marriage,adatrituals that parallel in reverse those performed at marriage are required. The woman must first take leave of her husband’s family and ancestors in amapamitceremony and is reunited with her natal ancestral spirits by ritually notifying them of her return (matur uning).

For Bali’s majority Hindu Balinese, this administrative bifurcation maps directly onto concepts of sekala (the practical, material world) and niskala (the invisible world, the domain of deities, ancestors and spiritual matters). It is difficult to encapsulate the power and importance of theniskala, but it was, and remains, crucial to personal well-being and community life.Niskalaconcerns determine individual actions and decision-making and adat concerns therefore impinge directly on the lives of Balinese janda. Failure to attend to the niskala dimension or to perform these rituals at marriage and divorce leave the woman in spiritual limbo with no place to worship her ancestors so central to Hindu-Balinese religion and no home from which thefinal rites of cremation and return to the ancestors can be carried out.

Return to the natal family−mulih deha

Under Balineseadatlaw, widows are expected to remain living within the husband’s home or family compound and thus they and any children of the marriage remain part of his ancestral group until the end of their lives and cremation ceremonies. In a practical sense, such living arrangements were, and are, sometimes impossible and pragmatic cul-tural solutions needed to be found. This solution is provided by the longstanding adat institution of returning to the natal family, or mulih deha, literally to return to the status of a daughter. This practice, which is attested in the traditional law codes (Creese

2008; 2016), continues to provide a core social mechanism forjanda in contemporary Bali and is, in fact, central to the capacity of individualjandato rebuild their lives.

In his study of divorced women in a small north Bali village noted above, Margi (2007) provides strong evidence for the effectiveness of the institution ofmulih deha.The 19 par-ticipants in his study were all young divorcees who had successfully renegotiated a position of respect and status within their natal families. There were many reasons for divorce,

ranging from their husbands’drunkenness, gambling and jealousy or failure to provide for them, to the women’s own health problems, including often their refusal to accept a co-wife (mamadu) or failure to have children (Margi 2007: 131). Their decision was not without considerable personal sacrifice since those who had children, the majority of the participants, had no legal guardianship over them and were no longer directly involved in raising them. They, nevertheless, took comfort in their success and well-being. They reported initial feelings of sadness, emptiness and hopelessness for the future (Margi

2007: 133). After divorce, the women supported themselves, and often their relatives and children, through their labour, working in the fields, raising livestock, running small warung (roadside stalls) and sewing. Their acceptance into their natal families also led to their reintegration as members of those family groups into the communal life of the banjar. For the families too, there were strong motivations for acceptance including averting the shame of having their daughters become homeless or destitute, but also unwavering affection for their children. As one of Margi’s informants commented (2007: 135):‘there is no such thing as an ex-family member’(sing ada laad nyame), or as one father remarked somewhat poignantly:‘I did not give away my daughter [at marriage], I only gave away the love she had for her husband’(tiang nenten mekidiang pianak, sake-wanten titiang mekidiang tresnan ipun). Once that love was rejected, it was only natural for his daughter to return.

The women in Margi’s study identified various all too familiar forms of stigma levelled at them including charges of sexual promiscuity or availability, enticing men, barrenness, disrespect to their husbands and failure to keep their families together. They sought to overcome or avert stigma through hard work and exemplary behaviour so that no charges of improper conduct could be levelled at them (Margi 2007: 137–9). These women, although remaining emotionally vulnerable, had achieved some measure of satis-faction in their post-divorce lives and had negotiated an acceptable place and status in community life. All these women were uneducated and had not moved away from the village in which they were born, but their circumstances and challenges have more general applicability. We turn now to our case studies to explore the different paths by which three women have balanced thesekalaandniskala, the material and the spiritual dimensions of becoming and beingjandain Bali.

Case studies

Musti’s story

Musti, now aged 64, is a commoner Balinese who was born and still lives in her home village, west of Denpasar. In 1967, when she was 17 years old, she married Made, a man from the same village. In the 1960s it was not uncommon in her village to marry at a relatively young age. The couple had two children, a son who was born in 1968 and a daughter who was born in 1970. Made died in 1979, when Musti was 29 years of age. Musti described the early years of their marriage as a time of hardship, with insufficient income to meet the family’s daily needs. Although their village was located only about four kilometres west of the city centre of Denpasar, up until the 1970s it was still a rural area with only one access road to the city centre. Agriculture and associated industries were the main sources of income in this village. Most people worked as farmers, some worked in town. Musti’s husband worked at an abattoir in Denpasar for a few hours each

morning and Musti worked as a casual labourer for a rice hulling factory delivering sacks of rice from the factory to shops or households by bicycle.

Three years after they were married, Musti opened a smallwarungto sell food, rice and beef soup (nasi soto). Made was able to obtain the meat from the abattoir where he worked at a special discount price. Musti’swarungbusiness became successful in a relatively short time, but her husband left his job at the butchery to become abalian(a traditional healer). He quickly developed a reputation as a skilled healer and was able to cure a number of sick people who came to him to seek help. Soon after becoming abalian,Made collapsed sud-denly one day. Delays in getting transport to take him to the hospital for emergency treat-ment meant he could not be saved.Balianwork between thesekalaandniskaladomains, and local rumour attributed his death to the supernatural intervention of enemies of his former patients.

Following Made’s death, Musti accepted her lot as a widow within traditional Balinese society. She remained living with her children in her late husband’s family compound and continued to run herwarungto support herself and her two young children. At 29 years of age, she was still young and attractive and a number of men started to approach her for sexual favours, including two of her brothers-in-law. Thefirst of these men was Wayan, the elder brother of her late husband. He was the most senior and most well-to-do member of her husband’s extended family and therefore exercised considerable influence within the family. He accepted the responsibility of caring for Musti and her children, including sending them to school, thus fulfilling hisadatobligations to his late brother’s family. According to Musti, Wayan tried to persuade her to have an affair with him, but she refused. At about the same time, Musti said, she was approached by another of her brothers-in-law, Nyoman, the husband of her elder sister, Sangri. Musti was more attracted to Nyoman than Wayan. She closed down herwarung and started to work in Nyoman and Sangri’s rice hulling factory. Musti’s task was to collect and deliver rice for the factory. In the course of her work, Nyoman often accompanied her and this enforced proximity made their relationship grow stronger. As a consequence, Musti’s relationship with her son and her brother-in-law, Wayan, became increasingly strained.

To distance herself from Wayan’s attentions, Musti returned to her natal home located just half a kilometre away in the same village. Her brother-in-law and father-in law dis-approved of her return to her natal home in violation of her obligation as a widow to remain in her late husband’s home. Her children remained in their father’s compound, but she maintained contact with them and contributed to their support. After two years as a widow, and as her relationship with Nyoman developed, Musti agreed to enter into a polygamous marriage with Nyoman for which the permission of hisfirst wife, Sangri, was needed. In spite of her initial resistance, Sangri finally consented to having Musti as a co-wife, motivated by a mixture of sisterly concern and face-saving: firstly, she wanted to help her sister who, since leaving her husband’s family, had no clear status in village religious and community life and, secondly, she wanted to stop unpleasant commu-nity gossip and condemnation of the couple living together outside marriage. Musti’s mar-riage to Nyoman lasted less than six months, largely because of Sangri’s unhappiness and dissatisfaction with their co-wife arrangement. Constant arguments made living together as a threesome impossible and Musti once again returned to live in her parents’ house (mulih deha).

Musti turned her energy and attention to her trading activities. After working for some time for other local business women, she set up her own business travelling around Bali and Java buying rice, which she then sold to local traders. The business generated sufficient profit for her to buy her own truck and hire a driver, Ketut, who had previously worked in her sister’s family business. Ketut was married and lived in west Bali. On their journeys to Java to buy rice, he took Musti to stay in his house. Musti began a relationship with Ketut. Initially, Ketut’s wife, Ngarti, was upset, but as she was dependent on the support and money her husband earned working for Musti, she was powerless to end the relationship. Moreover, Musti provided them with money to renovate their house and provided Ngarti with capital to open a smallwarung. She also paid their children’s school fees. Although they lived as a couple, Musti refused to repeat the mistake of becoming a co-wife. Her de facto relationship with Ketut continued and lasted for more than 20 years. She said that sometimes people commented negatively on her lifestyle, but she ignored them and stated that she was the one to determine her own needs and take responsibility for her life. Throughout the years she lived with Ketut, Musti maintained her relationship with her children and met her responsibilities to support them. As adults and married themselves, they gradually came to accept their mother’s life choices and her son invited her to return to the family compound. Musti agreed to leave Ketut and return provided her late hus-band’s family would accept her unconditionally. Adatrituals were performed in order for Musti to be presented again to her late husband’s ancestors and taken back into the kin group. The ritual served as a symbolic apology for any unacceptable past actions and allowed her spiritual reintegration into the family. Musti now lives with her son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren within her first husband’s family compound. She has helped her son to develop a successful small business but no longer runs her own business.

Commentary 1

In many ways, Musti’s life trajectory fits thejandastereotype for her generation charac-terised by early marriage, early widowhood, loss of status and return to the natal home, quick remarriage and rapid divorce. Nevertheless, largely through her own efforts, she was able to achieve economic independence and personal autonomy, in spite of her back-ground as a commoner Balinese (jaba) from a semi-rural and poor village with little edu-cation. Thrown back on her own resources and through her commitment to hard work, Musti succeeded in establishing and successfully running her business which grew from a small roadside stall to a larger scale enterprise.

At the time of herfirst husband Made’s death, Musti faced an unhappy future. Under adat law, she was required to remain in her husband’s family and remarriage required their permission. Historically a close male relative of the deceased was viewed as the ideal partner to avoid disputes over inheritance and preserve the patriline but Wayan, her late husband’s brother, was not proposing marriage. His sexual predation, and Musti’s unwillingness to enter a relationship with him, disrupted the normal adat pattern of widowhood, forcing Musti to leave her children and return to her natal home. For Musti, as for the rural divorcees described by Margi (2007), the natal family and personal relationships within them provided the necessary support at this time of per-sonal crisis. At that time, and again following her divorce from Nyoman, her natal family and community provided a refuge. Her sister Sangri’s willingness to accept Musti as a

co-wife is an example of the centrality of family support, even if their co-habitation rapidly proved to be unsustainable.

There are hints of stigmatisation or at least community disapproval about her life-style choices, but Musti herself dismissed these factors as unimportant. It was largely Sangri’s reaction to neighbourhood gossip that had precipitated her marriage to Nyoman in the

first place. She was comfortable with her relationships with men outside marriage, includ-ing her long term de facto relationship with Ketut. After her divorce, Musti moved away to a different part of the island, a common strategy to avoid stigma (see Mahy et al.2016) which may have mitigated any negative community comment.

Musti eventually forged a highly successful career away from her community, while preserving her children’s ties to their ancestral patriline through their continued residence with their father’s family, but her early experiences reveal significant structural disadvan-tage because of her uncertain status within theadatcommunity. Although Nyoman and Musti’s union had been formalised with a small traditionalmasakapanritual to mark their marriage religiously and symbolically and to make it socially acceptable in adat terms, Musti felt some regret that the complete set of rituals that mark a new marriage had not been performed. From anadatperspective there was some question about the validity of her marriage to Nyoman because, as a widow, she ought to have remained in her late husband’s family. In addition, administratively, she had no formal certification to legalise her marriage and subsequent divorce.

In contemporary Bali, as we have noted above, marriages and divorces must be legalised and ratified both administratively in accordance with the national Marriage Law and underadatlaw. The two processes are complementary: failure to undertake theadat cesses can lead to alienation and community rejection while neglect of administrative pro-cedures can result in lack of access to essential administrative services. Divorce, however, is a costly business, and in poor, rural village communities, such as those described by Jenn-away (2002) and Margi (2007), where everyone is aware of everyone else’s personal cir-cumstances, the final administrative step of civil registration of marriage and particularly of divorce can simply be overlooked.

Administrative lapses surrounding formal registration and certificates of this kind, were even more common 35 years ago and, for Musti, had later real world consequences. Musti’s status as a single woman, who had been both widowed and divorced, became a major issue when she tried to buy her own truck on an instalment plan and was asked to produce the identity card (KTP,kartu tanda penduduk) required of all Indonesian citi-zens. She had not needed one previously, and Musti now found it difficult to obtain one because of her ambiguous marital status. Herfirst marriage meant that she belonged to her

first husband’sbanjar(ward community), but her membership was no longer recognised because she did not reside there and had married someone from anotherbanjar. The ward community of her second husband, Nyoman, did not recognise her because their marriage and divorce had not been legalised. The head of her parents’ward community also refused to issue her with the necessary paperwork to apply for an identity card because she had not registered there at all. Ultimately, Musti was able to buy her truck through her brother’s personal connections with the head of the ward whom he persuaded to issue a temporary KTP to his sister. Nevertheless, these status issues highlight the vital nature of the appro-priate attention to the adat and administrative processes surrounding marriage and divorce.

Musti’s success hinged on her business acumen and her capacity to generate significant economic capital to support herself. The combination offinancial means and the willingness to accept personal responsibility for her actions allowed her to gratify her own needs and desires, including a 20-year de facto relationship with Ketut. Throughout this time she not only met her responsibilities towards her original family but also supported her de facto family. Thefinal chapter in Musti’s life is an interesting one. While she arguably left her village with low levels of social and cultural capital after her divorce from Nyoman, in her later years she has been able to make use of her accumulated economic capital to return to her natal village and restore her symbolic capital. Her savings have allowed her to retire from active work and now provide her with the time for leisure and rest. Like the Muslimjanda from West Java who participate inpengajianreligious gatherings discussed in Parker et al (2016), Musti has employed the strategy of performing piety as a way of gaining respect-ability and distancing herself from herjandapast. Not only has she been reintegrated into herfirst husband’s kin group but she has also become a respected member of her commu-nity who has immersed herself in the study of moral and religious values. She participates in a textual singing group (pesantian), and regularly joins interactive pesantian pro-grammes on radio and television (Putra and Creese2012). She has undertaken pilgrimages to temples both in and outside Bali and assisted other members of her radio singing com-munity who are less well off to participate in these excursions. She regularly performs voluntary work (ngayah) in her village by singing with her group in temple festivals and other social and religious events. Her life has come full circle and she has returned to a valued place in her community of origin, back with her late husband’s family under the protection of her son.

Tutik’s story

Tutik was born in 1946 into an educated middle-class family in a town in west Bali, one of seven siblings. Her father, a primary school teacher, was Balinese, while her mother was a Javanese Muslim and ran a small warung selling light meals, crackers, and fruit salad. Apart from her father’s income as a primary school teacher, her parents also earned money by renting out spare rooms in their compound, which was located on the main road between Denpasar and Gilimanuk, the harbour connecting Bali and East Java. After she graduated from junior high school, her parents wanted to send Tutik to Singar-aja, north Bali, to continue her studies at a senior high school there. Being a teacher, her father not only understood the importance of education but had sufficient income to support his children’s education. In 1962, at the age of 16, just as Tutik was preparing to go to Singaraja to continue her studies, she eloped with an upper caste man, Agung Bawa, and married him, moving into his family compound in the palace (puri) where the family upheldadat traditions. The couple had two daughters. Agung Bawa’s family had belonged to the Balinese ruling elite in the pre-colonial period and had maintained their social and political status and power throughout the colonial and early independence periods. Tutik’s hypergamous union to an upper caste man raised her caste status and she was given the new honorific high caste title of Biang, by which her natal family now had to address her. Her father and immediate family members were very upset about her mar-riage but were unable to prevent it because of the symbolic power such high caste families exercised within the community.

Tutik’s husband, Agung Bawa, and prominent members of his extended family were heavily involved in post-independence period politics and aligned with left-wing factions. During the period of chaos after the alleged communist coup in 1965, a number of family members, including Agung Bawa, were captured and killed, the familypuriwas destroyed and the extended family virtually annihilated. Tutik thus became ajanda PKI–that is, the wife of a suspected Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) activist or sympathiser (see Pohlman2016, this issue). Rather than risk potential threats of personal and sexual vio-lence commonly experienced by women suspected of communist sympathies or connec-tions during this period, Tutik returned to her natal home where her parents, who belonged to the nationalist wing, might afford her some protection. She took her eldest daughter with her, while the other daughter was raised by her husband’s sister who had married a Christian and had then converted to Christianity.

Although her family had some means, Tutik needed to work to support herself and provide for her two daughters. Initially, she helped her mother to run her smallwarung and her father to manage the renting out of the extra rooms in their compound. As a beau-tiful, young widow, herwarungattracted many people especially men wishing to seduce her. When her father transformed the front section of their family house into a hotel, he appointed Tutik as manager of the hotel; the smallwarungbecame a restaurant.

There were few hotels in the town until the early 1980s, therefore business people and government officers who came to the region frequently stayed there, reportedly lured by Tutik’s sexual availability. The success of the business allowed her to accumulate consider-able capital. She became active in professional organisations such as the local branch of the Indonesian Business Women’s Union (Ikatan Wanita Pengusaha Indonesia) and devel-oped wide social and professional networks. In spite of her successful business which pro-vided her with a good income, it was rumoured that Tutik supplemented her income regularly by sleeping with the guests at her hotel. In the mid 1970s, the main road that links Denpasar and Gilimanuk Harbour underwent a major reconstruction project. The

field-manager of the project, a man from the Philippines, became a long term resident of Tutik’s hotel. They began a love affair and Tutik often spent time with him travelling by car to project sites in the town and surrounding villages. On two or three occasions, men offered marriage but these polygamous marriages failed to take place because of objections from the men’s current wives and children. As a face-saving gesture for what she must have seen as a personal‘failure’to remarry, Tutik simply informed her relatives that her deceased husband’s spirit refused to permit it.

In 1982, Anak Agung Adi Perdana, a high caste man from Bangli who held a senior position in the provincial governor’s office began a relationship with her. When Tutik became pregnant by him, Adi Perdana refused to marry her because he was already married to a Javanese woman, and also because he was not prepared to accept that he was the only man who might have been the father of the child. Tutik’s father then mobi-lised his political networks and connections to report Adi Perdana to his superior, who forced him to consent to the marriage. The marriage took place when Tutik was five months pregnant. Adi Perdana did not attend the wedding ceremony and Tutik was married symbolically to hiskris, a pre-colonial prerogative of the high caste ruling elite (Pitana 1997: 73; 103). Because Tutik’s family had coerced him into marrying her to ensure the baby would be born legitimately, the marriage was a sham and lasted only a few weeks. Tutik quicklyfiled for divorce. As soon as it was granted, Tutik took leave

of her husband’s kin group with amapamitritual and returned to her natal home as a single woman again (mulih deha). Four months later, Tutik gave birth to a baby boy, who was given the upper caste titles of Anak Agung. Although Tutik looked after the baby and he remained with her, he was accepted as the son of Adi Perdana by his extended family. All the necessary life cycle rituals, such as the toothfiling ceremony and wedding rituals, were performed in his father’spuri. Tutik returned to her former life. She remained single, but as she grew older, her hotel and restaurant business became less successful because of increased competition but, so it was reported, also perhaps because her sexual attractiveness had diminished. She died of cancer in 2002.

Commentary 2

A number of common threads run through the stories of Tutik and Musti. The two women were generational peers, born just five years apart; both married young, were widowed in the early years of their marriage, married again but were soon divorced and both then chose not to remarry. Having taken the decision to forge their own futures, they both pursued their individual needs and surmounted a number of socio-cultural obstacles in different ways. Nevertheless, both were able to muster substantial economic resources that allowed them not only to pursue personal gratification but also to support their children and families. Although they had much in common, the individual experiences of Musti and Tutik provide some significant points of contrast. Following her divorce, Musti entered a long term relationship that continued for 20 years; Tutik, by choice or necessity, had multiple sexual partners. Musti’s origins were in a semi-rural village environment but Tutik was an urban Balinese from an educated family with greater cultural capital. Musti remained within her own caste group and avoided stigma by moving away from the confines of a closed village environment. Tutik’s journey, however, involved elements of politics, caste differences and changes in status and the stigma of sexual availability and promiscuity.

When Tutik’s marriage to herfirst husband was brought to an abrupt end by the anti-communist violence that swept through Indonesia in 1965–1966, she left the puri and returned to her natal family. She took her eldest daughter with her, while her younger daughter was raised by her husband’s sister in a Christian environment. The breakup of the family is likely to have been spearheaded as much by pragmatic asadatconsiderations, since there were so few surviving male members of her husband’s family to concern them-selves with the fate of his widow and her daughters. Although both daughters lived outside their father’s family, they retained their high caste status and titles and, foradatpurposes including lifecycle rituals, they remained part of their high caste kin group. Several years later, the second daughter suffered a serious illness that the family attributed to alienation from her family and Balinese Hindu heritage. Tutik then persuaded her to come and live with her once again.

Her husband’s death and the strong leftist political presence of the family locally left Tutik vulnerable to the violence perpetrated against women, including Balinese women, during the 1965-1966 crackdown (Dwyer 2004; Pohlman2016). Tutik escaped this fate by taking theadatroute ofmulih dehaand returning to the protection of her national-ist-leaning natal family. Tutik, a woman of commoner origins, married up twice to upper caste men, the first time for love, the second time from necessity. When Tutik married Agung Bawa in 1962, her family was powerless to stop it. By the time of her

second marriage to Adi Perdana 20 years later in 1982, the ascribed status of upper caste descent had crumbled before the authority of the acquired status that had been made poss-ible for commoner Balinese like Tutik’s father through education and success within the civil bureaucracy. Through her first marriage to a high caste man, when she joined her husband’s kin group, Tutik acquired new status and, despite her family’s objections, fol-lowed her heart. The second time, her father was able to mobilise his political connections to enforce her shotgun wedding to the high caste Adi Perdana in order to legitimise the child born to Tutik. Her marriages thus illustrate significant shifts in symbolic capital within Balineseadatsociety across the New Order period.

Tutik had enough disposable income from her hotel business to meet not just her own needs but also to provide for members of her extended family. She was well respected by members of her family and relatives who recalled her generosity, for example, in taking several of them on all-expenses paid tours of Bali and to Jakarta. Her economic capital was therefore able to stave off any loss of social and cultural capital that disapproval of her life-choices might have generated. At the same time, Tutik’s story also throws into relief the enduring nature of the stigmatisation of single women who seek or dare to pursue sexual relationships outside marriage, a stigma that is able to live on even after the person dies. Shades of disapproval of Tutik and her lifestyle appeared in a series of interviews with her family members. According to family gossip a propensity for promis-cuity was intergenerational and hardly surprising: her father had been a womaniser and had a daughter out of wedlock, while one of her daughters was also regarded as promiscu-ous and had run off with a half Javanese-Balinese man by whom she had a son. One family member, a doctor, reported that Tutik’s death from cervical cancer in 2002 at the age of 56 was directly related to her immoral behaviour and sexual activity. It is important to remember in this context, however, that Tutik does not speak for herself but instead her life-story has been related by extended family members. Nor is it possible to know if she felt the pain of stigma but made her own choices regardless. Unlike Musti, Tutik did not have the opportunity to renegotiate her status in the end stages of life or to re-invest her economic capital in other forms of redemptive symbolic capital.

Oki’s story

Oki was born in 1969 into a high castebrahmanafamily from Denpasar where she grew up. In 1997, when she was 28 years old, Oki married Tino, a Christian born in Jakarta whom she had met when he moved to Bali in 1994 to take up a position in the same international airline company in which she was working. Soon after their engagement, Oki resigned from the company and began working instead for another international airline based in Denpasar. Their employment provided the family with a substantial combined income. They were able to buy a piece of land in Gianyar and a house in Jakarta. The couple had two sons.

In order for Oki to continue to be actively engaged in her Balinese culture and religion, Tino became a Hindu and was embedded in Balinese culture and society through a some-what atypical nyentana marriage arrangement (see Creese 2016). Because Oki has a brother, no substitute male heir was needed, but Tino was, nevertheless, formally adopted into Oki’s natal high castebrahmanafamily to enable the couple to participate as full members of the localbanjar adat. Tino was not entitled to usebrahmanahonorific titles but their close friends often jokingly addressed him by the malebrahmanatitle Ida

Bagus, calling him‘Ida Bagus Tino’. As Hindu Balinese, the couple were required to reg-ister as members of both the customary village (desa adat) and the administrative village (desa dinas). Through thenyentanamarriage, they were registered as members of Oki’s father’s desa adat. They built a house in a different district on the other side of the town where they lived and registered themselves as members of thedesa dinasthere.

After about 10 years of marriage their relationship broke down when Tino began an affair with a girl whom he wanted to marry. Faced with irreconcilable differences, Oki instigated civil divorce proceedings through the Denpasar District Court. Tino did not contest the divorce. With sufficient economic resources to share, the couple reached an amicable arrangement about custody and the division of marital property and they agreed that Tino would take the house in Jakarta, while Oki kept the family home in Den-pasar and their land in Gianyar. The children remained with Oki in DenDen-pasar. Because Tino had become a Hindu and thus, inniskalaterms, was spiritually under the guardian-ship of the gods in Oki’s family temple, a ritualpamegat(detachment) ceremony was held to release him symbolically before he returned to Jakarta.

In accordance withadat, Oki reported her divorced status to the head of the banjar adat. Her new single status as mulih deha was formally announced and she became a member of the banjar under her parents’ membership. The family’s former status as full members of the ward in Tino’s name was withdrawn. For administrative matters, Oki renewed her family card in the desa dinas near her home and replaced her husband as the head of household. Under the adatsystem, Oki thus now belongs as a ‘child’in her parents’family; under thedinassystem, she is the head of her own family, as a single mother. A year or two after her divorce, Oki began an affair with a married man, a former friend from junior high school whose marriage had already broken down. Oki does not believe that she will remarry in the near future because her partner is suffering from a serious chronic disease.

As a single mother, Oki has had to look after her children, earn a living, and take care of all matters relating to her household. At the time of her divorce she did not have a per-manent job. She established a small printing and design business with her sister but it soon failed. Drawing on her professional experience working in international companies and small businesses, she joined a property business. She sold her land in Gianyar and used the money to buy a villa in a fast growing tourist resort in south Bali. The income from the rental supports her and her children. Her ability to speak English makes it easier for her to market and promote her villa to foreign tenants. Social networks that she developed through her professional contacts and experiences have contributed to her sense of self-confidence. Now in her mid-forties, Oki has achievedfinancial indepen-dence and does not rely on her family for material support. She continues to work in the property market and hospitality industries.

Commentary 3

Oki’s experience as ajandadiffers in many ways from that of Musti and Tutik. For Oki, born in the late 1960s, and for other women of her generation, there was a different range of options than those faced by older women such as Musti and Tutik. While they were both married in their teens, Oki was 28 before she married. Her marriage to Tino was a modern urban-based relationship, an interfaith and inter-ethnic marriage between two professionals, resident in the provincial capital, Denpasar. Their marriage and divorce,

too, were formalised through civil proceedings. Nevertheless, culturaladatties ensured a number of traditional practices still shaped their relationship and its end.

Because Tino was willing to convert to Hinduism and able to marry-in to her family, Oki, and importantly her two sons, were also able to practise their religion and be full members of theadat community that shapes religious and social activity in Bali. Tino willingly took ritual leave from the family after they were divorced. Oki’s acceptance back into her natal home and community was facilitated by her family’s brahmana status and the fact that her father was the head of thebanjar. In spite of her economic independence and personal autonomy, the importance of reintegration into her customary village as a single woman in an appropriatelyadatway into the community is clear. Her status and intermittent presence in thedesa adatare facilitated by her economic circum-stances. As many modern Balinese nowfind,financial contributions can be an acceptable substitute for an individual’s physical presence and labour. She has sufficient income to be able to donate funds when requested by her banjar. She also regularly performs socio-religious obligatory service (ngayah) in herbanjaras a way to maintain social acceptance. She is a singer, and she often joins in her village group choir in competitions as a way to maintain her social network in thedesa adat.

Oki says she is unlikely to remarry but, like Musti and Tutik, she is happy to seek relation-ships outside marriage. Because she belongs to an upper caste family, remarriage would, in any case, be more complicated for Oki. Under strict caste rules,brahmanawomen have a limited range of available marriage partners. Although Balinese women from lower castes can marry up as Tutik did, hypogamy is strictly proscribed andbrahmanawomen from the highest caste group may only marry someone from the same caste group. Because Tino was not Balinese, however, no caste boundaries were transgressed.

In addition to her modern urban lifestyle and comfortable economic circumstances, the nyentanamarriage between Oki and Tino, a non-Balinese man who was unencumbered by Balineseadatconcerns and obligations, undoubtedly smoothed the path to an amicable divorce. Although Oki reported never experiencing any direct stigmatisation as a divorcee, she initially kept her status a secret and said that she had tried to cover it up because she was worried about what others would say about her. When she revealed her status as a single parent, however, she found her friends were sympathetic and admired her capability in caring for herself and her children. The physical separation of her professional and family life in urban west Denpasar from her responsibilities as a member of the desa adatlocated on the other side of the city reflects changes in social mores within Balinese society more widely and facilitates her personal autonomy and a lifestyle that is relatively free of gossip andadatcommunity interference.

Oki attributes herfinancial independence and success to the income she receives from renting her villa and from working hard.‘Nobody will support us,’she said,‘if we cannot support ourselvesfinancially.’The risk she took in taking out a nine-year bank mortgage tofinance the purchase of the villa has paid off and confirmed for her the advantages of independence and her single status. She noted:

I am not a risk taker, but in this situation I had to be daring. I made the decision on my own. If I had had a husband, he might not have agreed to sell the land or borrow the money to buy a villa. My husband might disapprove of my investment. It has been four years now, I have had no problem in renting the villa and using the money to pay off the mortgage.

Oki keeps her daily andadatlives in balance. As she lamented in a Facebook post on a particularly difficult day recently when the plumber failed to turn up as arranged and she had to rush her son to hospital for an emergency appendectomy, the greatest diffi cul-ties she faces as a divorcee relate not tofinancial management but to the daily physical and emotional toll that single parenthood entails. Independence and resilience come at a cost, but for Oki the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks.

Oki’s story, and the different life choices she has been able to make when compared to women from earlier generations such as Musti and Tutik, may represent the changing face of family relationships. Demographic research indicates that patriarchal cultures generally have lower divorce rates (Heaton et al2001). In 1975, Geertz and Geertz reported that divorce was uncommon in Bali where it still remains the exception. National Bureau of Statistics (BPS, Badan Pusat Statistik) figures indicate that overall divorce rates for Bali were below the national average in the period 2009−2013. Divorce rates for women

remain amongst the lowest nationally.5 The overall proportion of divorced men and women remained relatively stable in the same period (Table 1).

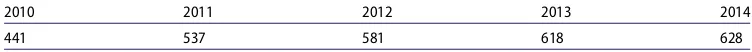

Conservative family values prevail in the media and general community. The popular and tabloid press regularly laments supposedly high divorce rates and lifestyle magazines have described marital breakdown, adultery and divorce as becoming a‘trend or lifestyle’ (Anggreni2004; Tokoh2011). There is some evidence that divorce rates in Bali may be rising. The number of divorces granted by the Denpasar District Court (Pengadilan Negeri Denpasar), for example, rose by over 50% in the five-year period 2010−2014

(Table 2).6 This trend may point to increased agency and freedom of personal choice amongst Balinese women at least in major urban centres such as Denpasar, as Oki’s story might suggest.

Conclusion

As elsewhere in Indonesia the status ofjandain Bali is anomalous in a society in which mar-riage remains the norm.In addition to issues faced byjandaelsewhere in Indonesia, such as stigmatisation, Balinesejandaconfront a range of culturally specific religious and social Table 1.Divorce rates for women and for men and women, 2009–2013. Source: BPS-RI, SUSENAS

2009–2013.

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Female Male + Female

Bali 1.28 1.36 1.46 1.23 1.55 1.02 1.20 1.11 1.03 1.11

Indonesia 1.76 1.82 1.76 1.68 2.40 2.54 2.57 2.49 2.34 1.78

Table 2.Number of divorces granted in the Denpasar District Court, 2010–2014.

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

441 537 581 618 628

5

With the exception of Papua, Bali had the lowest number of divorced women as a percentage of the population aged ten years and over amongst Indonesia’s thirty-three provinces in the period 2009-2012. In 2013, divorce rates for women increased slightly and were thefifth lowest after Papua, Lampung, Riau and the Riau Archipelago.

6The data inTable 2are unof

ficialfigures supplied to the authors by District Court officials.

constraints as they rebuild their lives following divorce or the death of a spouse. Successful janda-hood in Bali, however, requires attention not only to pragmatic concerns and material well being; it must be equally balanced by the ongoing negotiation of theniskala or spiritual dimensions of personal, extended family and community responsibilities. The Balinese dual administrative system that requiresjandato navigate both administrative andadathurdles, illustrates the complexity of the secular-adatinteraction that accompa-nies all marriage and divorce processes. It is difficult to convey the importance for Balinese of meeting their obligations to the gods and ancestors that necessitates full participation in theirdesa adatand temple communities. The evidence from our case studies, however, highlights the strong pull ofadatresponsibilities in daily life. Bali’s patriarchal social struc-ture bindsjandato their husbands’ families and ancestors for life, regardless of marital status at any given moment; they must ensure that their children continue to meet their reli-gious obligations, and divorce, or remarriage for widows, can therefore never be a simple personal decision. The emotional toll onjandawho leave the marital home and the care of their children to their husbands’extended families is profound. These Bali-specific cul-tural dimensions, however, have both negative and positive impacts on the decision-making and lifestyle of individuals. Crucial to the capacity ofjandato become independent, in Bali as elsewhere in Indonesia, is the support of families and communities. The uniquely Bali-nese social institution of returning to the natal home,mulih deha,which meets both the practical (sekala) and spiritual (niskala) needs of individual jandais the foundation of the reintegration and acceptance ofjandawithin thebanjarcommunity.

In spite of these obstacles, the three women whose stories are retold here have success-fully negotiatedjanda-hood. Their stories provide rich examples of the multiple strategies available tojanda.The key to successful single status for all three of thesejandahas been the accumulation of adequate economic capital to meet their day-to-day needs. Through their own efforts and hard work, all three women have been able to live in relative comfort and to provide both for their immediate and extended families. They have been able to reinvest the economic capital their hard work and energy has created in various forms of social and cultural capital that enable them to negotiate their status and position as full members of Balineseadatsociety. While economic resources are crucial, as Margi’s study (2007) demonstrates, poor and rural women who marry within their natal villages are also able to negotiate their new status asjanda ceraieffectively.

Our case studies, which include the two ‘whole-of-life’ histories of Musti and Tutik, demonstrate how these various strategies enable twojanda, who at different times were both widowed and divorced, to negotiate their life chances successfully and to reframe the economic, social cultural and, crucially, the symbolic capital disrupted by the end of a marriage to achieve successful lives and respected status as single women. Their stories underline the ongoing nature of negotiating life as ajandaas circumstances and resources change. Ultimately, these threejandastories are reflections of agency that docu-ment the opportunities for Balinese women from diverse backgrounds to rebuild their cul-tural and social networks though participation in community life. Such possibilities exist even in the face of grinding poverty but even more so when hard work and circumstances provide individual women with sufficient capital to overcome disadvantage and forge meaningful personal and communal lives, that can ultimately be traded and transformed into social acceptance and the cultural and symbolic capital that underpins meaningful existence in Balinese society.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the UWA-UQ Bilateral Research Collaboration Awards which funded the collaboration of researchers on this project.

Author biographies

I Nyoman Darma Putra teaches Indonesian literature in the Faculty of Letters and Culture, Udayana University (Bali) and is an adjunct professor in the School of Language and Cultures, the University of Queensland. He is the author ofA literary mirror: Balinese reflections on moder-nity and identity in the twentieth century(KITLV/Brill, 2011). Email:idarmaputra@yahoo.com Helen Creeseis Associate Professor in Indonesian in the School of Language and Cultures, the University of Queensland. Her most recent book is Bali in the early nineteenth century: the ethnographic accounts of Pierre Dubois,(Brill forthcoming). Email:h.creese@uq.edu.au

References

Allen, Pamela and Palermo, Carmencita. 2005. Ajeg Bali: multiple meanings, diverse agendas.

Indonesia and the Malay World33 (97): 239–55.

Anggreni, Luh Putu. 2004. Perceraian dan perlindungan terhadap anak [Divorce and the protection of children].Tokoh23–29 May.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977.Outline of a theory of practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood, pp. 241–58.

Creese, Helen. 2008. The regulation of marriage and sexuality in precolonial Balinese law codes. Special issue on ‘Gender text performance and agency in Asian cultural contexts’.

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 16. <http://intersections.anu.edu.

au/issue16/creese.htm>

Creese, Helen. 2016. The legal status of widows and divorcees (janda) in colonial Bali.Indonesia and the Malay World44 (128): 84–103.

Dwyer, Leslie. 2004. The intimacy of terror: gender and the violence of 1965-66 in Bali. Special issue on‘Women’s stories from Indonesia’.Intersections:Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific

10. <http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue10/dwyer.html>

Geertz, Hildred and Geertz, Clifford. 1975.Kinship in Bali. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Heaton, T., Cammack, M. and Young, L. 2001. Why is the divorce rate declining in Bali?Journal of

Marriage and Family63: 480–90.

Jennaway, Megan. 2002.Sisters and lovers: women and desire in Bali. Lanham MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Korn, V.E. 1932.Het adatrecht van Bali. Tweede herziene druk[The adat law of Bali. 2nd revised edition]. The Hague: Naeff. First edn 1924.

Lewis, Jeff and Lewis, Belinda. 2009.Bali’s silent crisis: desire, tragedy and transition. Lanham MD: Lexington Books.

Mahy, Petra, Winarnita, Monika Swasti and Herriman, Nicolas. 2016. Presumptions of promis-cuity: reflections on being a widow or divorcee from three Indonesian communities.Indonesia and the Malay World44 (128): 47–67.

Margi, I Ketut. 2007. Jandamulih deha: Sisi kedermawanan sosial terhadap kepapaan perempuan di desa Padang Bulia Buleleng Bali [Jandareturning to their natal family: aspects of social philan-thropy in female poverty in Padang Bulia, Buleleng Bali].Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Sains dan Humaniora1 (2): 121–42.

Liefrinck, F.A. 1927.Bali en Lombok geschriften[Writings on Bali and Lombok]. Amsterdam: De Bussy.

Panetja, Gde. 1989. Aneka catatan tentang hukum adat Bali [Notes on Balinese adat law]. Denpasar: Guna Agung. Second edn.

Parker, Lyn. 2016. The theory and context of the stigmatisation of widows and divorcees (janda) in Indonesia.Indonesia and the Malay World44 (128): 7–26.

Parker, L., Riyani, I. and Nolan, B. 2016. The stigmatisation of widows and divorcees (janda) in Indonesia, and the possibilities for agency.Indonesia and the Malay World44 (128): 27–46. Pitana, I Gde. 1997. In search of difference: origin groups, status and identity in contemporary Bali.

PhD thesis, Australian National University.

Pohlman, Annie. 2016.Janda PKI: stigma and sexual violence against communist widows following the 1965–1966 massacres in Indonesia.Indonesia and the Malay World44 (128): 68–83. Putra, I Nyoman Darma and Creese, Helen. 2012. More than just‘numpang nampang,’women’s

participation in interactive textual; singing on Balinese radio and television.Indonesia and the Malay World40 (118): 272–97.

Schulte Nordholt, Henk. 1996.The spell of power: a history of Balinese politics 1650–1940. Leiden: KITLV Press.

Schulte Nordholt, Henk. 2007. Bali. An open fortress, 1995–2005: regional autonomy, electoral democracy and entrenched identities. Singapore: NUS Press.

Sukranatha, A.A. Ketut. 2002. Kedudukan perempuan Bali terhadap harta bersama dalam hal terjadi perceraian. Analisis perkembangan yurisprudensi [The position of Balinese women in relation to shared property at divorce: an analysis of juridisprudential development]. Research report, Faculty of Law, Udayana University, Bali, Indonesia.

Tokoh2011.Tokoh: bacaan wanita dan keluarga[Celebrity: women and family magazine]. Issue 651, 10–16 July.

Warren, Carol, 2003.Adat and dinas: Balinese communities in the Indonesian state. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Windia, Wayan P. 2014.Hukum adat Bali: aneka kasus dan penyelesaiannya[Balinese adat law: several cases and their resolution.] Denpasar: Udayana University Press.

Website

Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia <http://bps.go.id/linkTabelStatis/view/id/1602>