ZAKAT LAWS IN INDONESIA

By :

Heru Susetyo, SH. LL.M. M.Si. Ph.D

2018

i

Heru Susetyo

Zakat Laws In Indonesia / Heru Susetyo, - Cet. 1. Depok: Publisher Faculty of Law University of Indonesia, 2018

viii, 269 page ; 17 cm x 25 cm 297.54

Zakat Law

ISBN 978-602-5871-02-3

designed cover by

First edition

First Printing, May 2018 Zakat Laws In Indonesia By: Heru Susetyo

All rights reserved to authors are reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form of stencils,

photocopies, microfilms or any other means without the written permission of the author and publisher

Published by:

Publisher Agency Faculty of Law University of Indonesia

Jl. Prof. Mr. Djokosoetono, Kampus U.I. Depok 16424 Fakultas Hukum Gedung D Lantai 4 Ruang D.402

Telepon. +61.21.727.0003, Pesawat 173, Faxsimile. +62.21.727.0052 E-mail. law.publisher@ui.ac.id

For my mother

ii

My mother

My mother

And my father…

Who have shown me their unconditional love and support all my life

For my lovely wife, Widi Utami … who have shown me her unconditional love and support in times of trouble and pleasure

For my lovely boys, Radhi, Faris and Adian and lovely girl, Amira…to make my life more cheerful and meaningful…

To all of them this book is dedicated….

iii

Foreword

FromProf. Dr. Topo Santoso, SH, MH.

Dean Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia (2013 – 2017)

Assalamualaikum warrahmatullahi wabarakatuh

The book written by Dr. Heru Susetyo is part of textbook grant program of 2017 which was managed by Badan Penerbit (Publishing Agency) Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia. Thank you so much for Dr. Heru Susetyo, Prof Uswatun Hasanah, and other researchers at Center for Islam and Islamic Law Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia that have strongly supported the publication of this book.

This book is very important for students, faculties, as well as researchers who are interested to study zakat and zakat management in Indonesia, since it describes about the socio political dynamic of zakat secularization in Indonesia.

Furthermore, let me express my utmost gratitude for Dr. Arie Afriansyah, Ms. Qurrata Ayuni, Ms. Ryan Muthiara Wasthi, and Mr. Dede Wawan from Badan Penerbit (Publishing Agency) Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia for selecting, editing and finally publishing this book.

I do hope that this book will enrich the discourse of Islamic Law in Indonesia. Happy reading !

Wassalamu’alaikum Warrahmatullahi wabarakatuh

iv

Foreword by

Prof. Dr. Dra. Uswatun Hasanah, MA.

Professor of Islamic Law Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia

Assalamualaikum warrahmatullahi wabarakatuh

This book is derived from PhD dissertation made by Dr. Heru Susetyo at PhD program in Human Rights and Peace Studies, Mahidol University, Thailand where I also co-supervise and co-examined it. Congratulations for Dr. Heru Susetyo !

This book is not about the fiqh of zakat but about the socio political dynamic of zakat secularization in Indonesia. Therefore this book is distinctive and peculiar. Very few books talks about zakat practices in Indonesia, and even less that is written in English.

I take this opportunity to express my utmost gratitude for Prof. Topo Santoso, Dean of FHUI 2013 -2017, Prof Melda Kamil, the Current Dean of FHUI, and all researchers of Center for Islam and Islamic Law Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia (LKIHI FHUI), not to mention Badan Penerbit (Publishing Agency) Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia for selecting, editing and finally publishing this book.

I do expect this this textbook of zakat will enrich the discourse of zakat management and Islamic Law in Indonesia.

Wassalamu’alaikum Warrahmatullahi wabarakatuh

v

Preface from the Author

Assalamualaikum warrahmatullahi wabarakatuh

All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds. The Beneficent, the Merciful. Master of the Day of Judgment. Thee do we serve and Thee do we beseech for help. May prayers and peace be always upon the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

This book is derived from PhD dissertation made at PhD program in Human Rights and Peace Studies, Mahidol University, Thailand, under supervision of Dr. Sriprapha Petcharamesree, Dr. Yukiko Nishikawa (IHRP Mahidol University and Nagoya University), Prof Dr. Uswatun Hasanah (from Universitas Indonesia) and under generous support and assistance from Dr. Yanuar Sumarlan (IHRP Mahidol University). Thank you so much for Dr. Sriprapha, Dr. Yukiko, Prof Uswatun and Dr. Yanuar for the opportunity given to me to study with you and exhaust your valuable scholarship.

The author also indebted to Dean Prof. Hikmahanto Juwana, Dean (almarhum) Prof Safri Nugraha, Acting Dean Dr. Siti Hajati Hossein, Dean Prof. Topo Santoso and current Dean Prof Melda Kamil. Without their generous support and attention this dissertation and book won’t be finished.

This book talks about the socio political dynamic of zakat secularization in Indonesia. Zakat management in Indonesia, the most predominantly Muslim country in the world, is very unique. The fiqh is almost similar with other Muslim countries but the practices and zakat management is different. It is greatly influenced by national and local socio-political dynamic.

Last but not least, the author also expresses utmost gratitude for Dr. Arie Afriansyah, Ms. Qurrata Ayuni, Ms. Ryan Muthiara Wasti, and Mr. Dede Wawan from Badan Penerbit (Publishing Agency) Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia for selecting, editing and finally publishing this book.

Hopefully this book will enrich the discourse of zakat practices and Islamic Law in Indonesia.

Wassalamu’alaikum Warrahmatullahi wabarakatuh

vi

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD PROF. DR. TOPO SANTOSO, SH., MH....i

FOREWORD PROF. DR. DRA.USWATUNHASANAH, MA....ii

PREFACE FROM THE AUTHOR...iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS...iv

ABOUT THE AUTHORS ...vi

CHAPTER IINTRODUCTION...1

I.I. Background CHAPTER II WHAT IS ZAKAT II.1. Introduction13 II.2. Zakat: Conceptual Basis II.3. Zakat as Islamic Social Fund II.4. Zakat and The Role of The State II.5. Zakat Attraction to the State25 II.6. Conclusion ...31

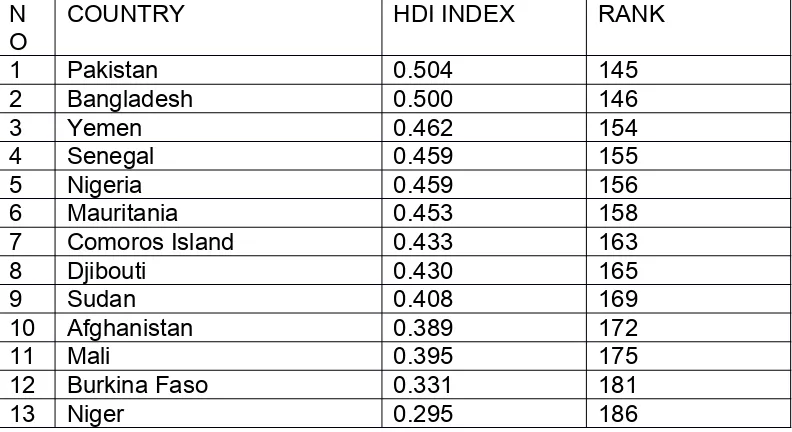

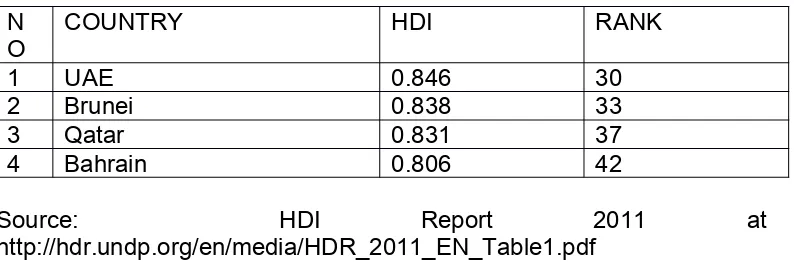

CHAPTER III ZAKAT IN MUSLIM WORLD III.1. Introduction III.2. Zakat, Poverty and Muslim World III.3. Zakat Practices in Selected Countries III.4. Zakat Practice in Indonesia III.5. The Distinction of Zakat Management in Indonesia III.6. Conclusion CHAPTER IV INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF ZAKAT BY THE STATE IN INDONESIA IV.1. Introduction56 IV.2. Development of Institutionalization of Zakat in Indonesia...56 IV.3. State-Based Zakat Management in Different Administration

IV.4. Zakat Management by Non-State Zakat Agencies IV.5. Politicization of Zakat

IV.6. Socio Political Dynamic of Zakat In Indonesia IV.7. Conclusion

viii

CHAPTER V SOCIO-POLITICAL DYNAMIC OF INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF

V.1. Introduction

V.2. Legal Struggle for Securing People’s Rights on Zakat Administration

V.3. Implications on Zakat Administration

V.4. Impact on Zakat Collection and Distribution : People Resistance

IV.5. Institutionalization of Zakat and Justice143 IV.6. Conclusion9

CHAPTER VI INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF ZAKAT AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

VI.1. Introduction

VI.2. Right to Social Security in International and Regional Instruments

VI.3. State and Non State Social Security

VI.4. Social Security Rights in Country Report and UPR VI.5. Zakat as Social Security

VI.6. Zakat : Compulsory of Philanthropy? Rights or Welfare? ...186 VI.7. Conclusion ...193

CHAPTER VII CONCLUSION

GLOSSARY ...206

BIBLIOGRAPHY208

LIST OF INTERVIEWEES ...213

ix

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Short Bio data

Heru Susetyo, SH. LL.M. M.Si. Ph.D.

Heru Susetyo in an assistant professor at Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia Department of Law, Society and Development and also Chairman of Center for Islam and Islamic Law at Faculty of Law Universitas Indonesia (since 2015). He is currently teaching human rights, victimology, law and social welfare, children protection law, law and society for undergraduate and Legal Research Method and Zakat Wakaf for Master of Law students. Besides, he also teaches at Faculty of Social Sciences and Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia. Graduated from Universitas Indonesia in 1996 (bachelor or law) and 2003 (master of social work) and also obtained master of International human rights law (LL.M) from Northwestern Law School, Chicago (2003) and a PhD in Human Rights and Peace studies from Mahidol University, Thailand (in 2014). Currently, he is conducting research to obtain PhD in victimology at INTERVICT, Tilburg University, and The Netherlands. Instead of teaching, Heru Susetyo has written numerous articles in various newspapers, magazines and online media and also published several journals and books related to human rights, victimology, terrorism, social work and international criminal law. He has also been responsible to handle research and publication affairs at faculty of University as Manager of Research and Publication (since 2018), Editor in Chief of Jurnal Hukum dan Pembangunan FHUI (since 2018) and Editor in Chief of Journal of Islam and Islamic Law Studies (since 2007). He is reachable by email at

hsusetyo@ui.ac.id and his own blog : http://herususetyo.com

x

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

I.1. BACKGROUND

Zakat is a form of religious contribution (alms) in Islamic teaching. Islam is the religion embraced by majority of Indonesian people. In 2010, Muslim population in Indonesia amounted to 207.8 million people out of 237.6 million (or 87.3 percent)127. With this large number, Indonesia is considered as the most populous Muslim country in the world to surpass Pakistan, India, Turkey and Egypt. The large number of Muslim population does not reflect that Indonesia is Islamic country. Nevertheless, the influence of Islam still significance both in the government as well as in society. Yazid, et.al. (2010) clarified that the relevance of religion has been an important issue both in the context of policy and social sciences. In terms of policy, there are a number of institutions which are related to religion. The welfare institutions, educational institutions and even banking institutions are connected to religion. Therefore, religion used to have an extensive role in almost every aspect of society. In terms of policy, religion has a close relationship with the state and religious leaders who are very actively involved in the government.

However, in the case of Indonesia, the relation between Islam and the state is unique and the way Indonesian people practicing Islam are actually more in Indonesian way, rather than the Arabian way128. Some Indonesian Muslim scholars are irritated by the Western inclination to identify Islam per se with the Middle East and Arabism. Former President Wahid, for example, repeatedly pointed out that ‘Islam and Arab culture are not the same’ (Woodward 1996: 136 in Kolig, 2009). Wahid is said to have demanded that Islam be ‘indigenized’ in Indonesia; i.e., it should be ‘deeply

127

Based on survey conducted by Badan Pusat Statistik (Central Agency for Statistics) in 2010. Other religious groups are Christians (16,528,513), Catholics (6,907,873) Hindu (4,012,116), Buddhists (1,703,254) Confucianists (117,091) and others (around 1.3 million).

128The Islamic teaching was born and developed in Arabian Peninsula in 6th -7th

centuries by Prophet Muhammad PBUH and his companions and disciples.

planted in modern Indonesian soil’ by adapting it to Indonesian conditions and shedding the Arabic precedence (Abdullah, 1996: 69 in Kolig, 2009).

For a religion in a state with Muslim majority, Islam is not just a religionbut it is the way of life. In the case of Indonesia, some Muslims still practice Islam and follow the five pillars of Islam while other Indonesian Muslims are not.129

Zakat or Alms is one of the most important Muslim’s ways of life. It is in fact the third pillar of Islam which makes it an obligation for Muslim to fulfill the requirement of paying zakat in money or in kinds. However, since some Indonesian Muslims are not really practicing Islam and with no penalties imposed by the government, the fulfillment of zakat payment obligation is dependent on the individual Muslim’s belief or ‘taqwa’ (piety).

Due to the low number of zakat revenues received by zakat collecting institutions and small number of Muslim people disbursing their zakat money, the government of Indonesia then intervened in zakat affairs by creating state-based zakat collecting institutions and announced new laws related to zakat affairs since the 1990s. From this point of view, the practice of zakat in Indonesia is good measure of institutionalization. Nevertheless, texts of institutionalization of zakat policy is very scarce in the literature. Among of them are Yazid (2010) who discussed institutionalization of zakat in Malaysia, and Mohamad (2010) who studied bureaucratization and institutionalization of the Sharia in Malaysia.

The concept of secularism is an ideology or doctrine. It is the separation of religion from other affairs and not necessarily exclusion of religion from having authority over political and social affairs. Institutionalization hypotheses actually consists of three different interpretations: institutionalization as a decline of religious belief and practices, institutionalization as marginalization of religion to a privatized sphere, and institutionalization as the segregation of secular spheres from religious standards and institutions (Cassanova, 1994 in Yazid, 2010).

Institutionalization in Indonesia in religious affairs started when the state established Ministry of Religion in 3 January 1946, only four months after Indonesian Independence on 17 August 1945. This ministry managed to regulate religious affairs of all acknowledged religions in Indonesia (Islam, Christian, Catholic, Hinduism, Buddhism and later on Confucianism). In Islamic affairs, the ministry managed to regulate hajj

129

There is a famous people’s terminology to address Indonesian Muslim swho are not really practicing Islam as ‘Islam KTP”. KTP or Kartu Tanda Penduduk (National Identity Card) contains religious affiliation and some people put ‘Islam’ as their religious affiliation on KTP but they are not actually practicing Islam.

(pilgrimage), Islamic education, Islamic propagation, and subsequently the zakat and waqf (under special directorate).

Related to zakat affairs in Indonesia, zakat was initially managed and administrated solely by Indonesian Muslims, even long before Indonesian independence in 1945. Yet, after establishing the Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kementerian Agama), the state managed to secularize zakat affairs by announcing Law on Zakat Administration No. 38/1999 and installing state-based zakat agencies called BAZNAS (Badan Amil Zakat Nasional or National Zakat Agency).

Geertz (in Kolig, 2001) saw institutionalization mainly in terms of ‘institutionalization of thought’, brought about by the growth of science and resultant loss of religious certainties. Modernization cannot occur without institutionalization. Islamic societies, in his view, show little sign of institutionalization and hence cannot truly be modernized. On the contrary, they show a tendency to resist modernization by engaging in anti-secular movements, thus manifesting their inability to keep up with the western society. Clifford Geertz, who studied Javanese and local muslim in Java Island in the 1900s, might be right when he said that Islamic societies showed a little sign of institutionalization and hence could not truly be modernized. In the case of Indonesia, even though, the state has exhausted all efforts to secularize muslim affairs, particularly in zakat affairs, yet the people do have their own needs and wants on zakat which are different from those of the state.

Dinc (2006) holds that institutionalization is defined as the decline of the social significance of traditional religions as an unmistakable very important part of the modernization process. Institutionalization is strongly connected to the decline of the community in the modern societies, which also meant the decline of the communitarian spirit and the rise of materialist, individualist culture and promotion of the individual vis-à-vis social group. Turner (in Isin & Nielsen, 2008) argued that within Islam there are a parallel set of acts that constitute a religious community. Just as acts of citizenship are necessary to construct a commonwealth, acts of piety are necessary to create a community. The worth of citizens within the civil city is measured by their contributions to the community through activity in three arenas or ‘pillars’ such as work, war, and reproduction. These are very obvious in the case of Islam where the worth of an individual is measured formally in terms of the Five Pillars of orthodoxy, namely the hajj (pilgrimage), shalat (the prayer ritual), shaum (fasting during Ramadhan Month), syahadah (the profession of faith) and zakat (almsgiving). Zakat appears as tax, and hence a Muslim who pays their taxes are active members of the umma, which is a global political community.

The problem emerges when zakat, as a divine and also a religious instrument, must be accommodated in secular (or semi-secular) muslim country, like Indonesia. Not just secular, Indonesia also has various social security mechanisms originated from traditional values, beliefs, religions, as well as state laws, in other words, the legal pluralism of social security mechanism is applicable in Indonesia.

For the zakat itself, since there is a notion that zakat money is not belonging to zakat payers (the money which are temporarily under zakat payers’ ownership are actually belonged to zakat recipients), zakat money are claimable. Zakat can be classified as the poor’s right and not simply the rich’s. However, to classify zakat as a right and not simply a charity, it must be contextualized and related to human rights, particularly social security rights.

The right to social security is recognized since the end of the Second World War, as a basic human right. For its fundamental importance, social security is one of the greatest achievements of modern society, even if it is certainly not fully available to everybody. For those who have access to it, social security means freedom – to a certain extent – from the perennial anxiety about present and future means of existence. This is a form of real freedom, to which people are very strongly attached (Langendonck and Put, 2006).

Among the significant legal and moral basis concerning social security rights is Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) 1948 which simply states that "Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security". This is further elaborated upon in Article 25 which says in its first section: "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.”

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights concluded in the United Nations on 19 December 1966. Article 9 of the Covenant repeats the wording of the Declaration concerning "the right of everyone to social security", with the addition of "including social insurance". This seems to indicate that assistance-type benefits are not sufficient for the right to social security, but that some hard entitlements without individual assessment of need are required. But apart from this, the text does not add anything to the vague general statement in the Universal Declaration. Therefore, this important right lacks a clear definition. In the international instruments, that define this right, it is stated in general terms, without further specification. It is far from clear what are the precise

obligations of states that ratify the international instruments concerning this right and/or who incorporates this right in their national Constitution (Langendonck and Put, 2006).

This unclear definition then leads to unclear concepts. Social security right might be one of unpopular and less discussed rights in this planet. While many people talk a lot about civil and political rights, economic rights, development rights, etc., few people pay attention to social security rights. This notion is in line with the general comments of ESCR Committee to Right of Social Security which express this issue as follows :

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee) is concerned over the very low levels of access to social security with a large majority (about 80 percent) of the global population currently lacking access to formal social security. Among these 80 percent, 20 percent live in extreme poverty. During its monitoring of the implementation of the Covenant, the Committee has consistently expressed its concern over the denial of or lack of access to adequate social security, which has undermined the realization of many Covenant rights. The Committee has also consistently addressed the right to social security, not only during its consideration of the reports of States parties but also in its general comments and various statements.130

Meanwhile, social security systems do not just belong to international laws. The practices and concepts of social securities have been found in many nations, ethnicities, values, religions, and beliefs, both in modern and traditional life, either in the current and the past, in a modest and even in complex forms.

General Comment No. 19 of ESCR to the rights of social security distinctly mentions that (point no. 5) :

“Other forms of social security are also acceptable, including (a) privately run schemes, and (b) self-help or other measures, such as community-based or mutual schemes. Whichever system is chosen, it must conform to the essential elements of the right to social security and to that extent should be viewed as contributing to the right to social security and be protected by States parties in accordance with this general comment.”131

Given the case of Islamic law, Islam is a world’s religion worshipped by around a quarter of world population. Yet, Islam is not just a religion, but

130

General Comments No. 10 point (7) and (8) of ESCR Committe at 39th Session on 3 – 27 November 2007,, available at http://www.refworld.org/docid/47b17b5b39c.html.

131General Comments No. 10 point (5) of ESCR Committe at 39th Session on 3 –

27 November 2007, available at http://www.refworld.org/docid/47b17b5b39c.html.

also a teaching containing with comprehensive laws and orders. The teaching and practices of Islam have shown us some forms of social security. Nevertheless, some scholars have doubted that Islam is compatible to human rights and whether the Islamic Social Security System can coexist with other systems in harmony.

To understand more about this issue, the social security system in Indonesia might be given as a good example. Indonesia is the most populated Muslim country in the world with about 207 millions Muslim inhabitants (out of 237 million in 2010). However, the country is not an Islamic country132, but rather a country which accommodates all religions and beliefs under the state philosophy of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity).133 Islamic laws are existing in Indonesia along with secular laws and customary laws. In other words, Islamic laws are existing in legal pluralism situation. Islamic laws have coexisted with other laws in Indonesia for many years.

Indonesia is also a country that ratified major human rights conventions, including International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (through the Law No. 12/2005) and International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (through the Law No. 11/ 2005). The country has also enacted some laws related to human rights such as Human Rights Act No. 39 year 1999, Human Rights Court Act No. 26 year 2000, the Law on Ratification of Convention against Torture in 1998, The Law on Ratification of Children Rights Convention in 1990, The Law on Ratification of CEDAW in 1984, and so on.

Islamic Laws in Indonesia had been developed long before the Indonesian Independence in 1945, precisely during the Dutch Colonialization. Before the 1945 independence, Islamic courts and some Islamic laws had also been introduced in very modest manner. Yet, the real development and formal recognition of Islamic Laws in national legal

132

Simon Butt (2010: 1) mentioned that Indonesia is home to more Muslims than any other country. Yet it is not an Islamic state and is unlikely to become one, despite the strong and sustained urgings of some Muslim groups. Indonesian Islam is, like Indonesian society itself, dynamic and diverse, accommodating a wide variety of practices and beliefs. Butt also quoted Gertz (1960) and Ricklefs (2008) that many scholars agree that a large majority of Indonesian Muslims are moderate and tolerant. Although holding a strong sense of Islamic identity and ritually oberving the five pillars of Islam, these Muslims also accept the multitude of local spiritual observances not necessarily inspired by Islam.

133

There are a lot of debates whether Indonesia is really a secular country, because, Indonesia is still greatly influenced with religious values, particularly Islamic values. Imtiyaz Yusuf, an expert of Islamic Politic from Mahidol University, (interview in Bangkok, 29 April 2013) prefers to address Indonesia as ‘semi-secular country.’

system were actually beginning after the Indonesian Independence in 1945 up to present.

The first milestone and significant national law heavily influenced by Islamic law was Indonesian Marriage Law No. 1 year 1974. The law is actually a national law but many of its provisions are clearly derived and greatly influenced by Islamic Marriage Law.134 Following marriage Law, the country also enacted Indonesian Law on Islamic Court No. 7/1989, Islamic Family Law Compilation year 1991, the Law on Zakat No. 38/1999 (later amended by Law No. 23/2011), the Law on Wakaf (endowment) No. 41/2004, the Law on Islamic Banking System No. 21/2008 and Law No. 19/2008 on State Sharia Obligation (or Sukuk in Arabic Language), the Law No. 3/2006 (amended by Law No. 50/2009) on extensification of jurisdiction of Islamic court.

While the aforementioned laws deal mostly with family and economic affairs, the Islamic laws in Aceh have gone further by introducing local ordinances/local bylaws in Islamic Criminal Laws (or Qanun) which have specific jurisdictions on certain areas, namely : adultery (zina), gambling (maisir), alcohol (khamr), and khalwat (man and women out of wedlock intimately conjoined together in a remote place), and also (in 2009) introducing a qanun on jinayah (or local ordinance in Islamic Criminal Law) which also covers stoning to death punishment (rajam) for adulterers and amputation for thief (but so far, until beginning of 2014, this law has not been implemented because of heavy criticism from public).

Among several prevailing Islamic laws in Indonesia, there are at least three laws containing the provision of ‘social security’ in various types, namely The Law on Zakat No. 38/ 1999, the Law on Wakaf No. 41/2004, and the Law on Islamic Banking No. 21/2008. The Law on Zakat No. 38/1999 clearly mentions, on its consideration part, that zakat is one of potential financial resources for community welfare. Zakat is an Islamic instrument made to establish social justice, and that zakat pays special attention to the needy people. Article 16 of Zakat law mentions that money originated from zakat collection will be disbursed for those who are eligible to be the beneficiaries according to holy Al Qur’an and Islamic teaching. Furthermore, the same article rules that the utilization of zakat collection must be strictly based on priorities of the needy people (mustahiq) and is utilized for productive efforts. In addition, the infaq, shadaqah, wasiat, waris and kafarat (all are type of giving provided by Muslim) must be utilized, preferably for productive efforts.

134

The nationalist and democratic party of Indonesia ( PDI or Partai Demokrasi Indonesia) disapproved this Marriage Bill of 1974. Their MP’s walked out from the forum for following reasons: the bill was regarded as heavily influenced by Islamic values or Islamic interest and it was incompatible to nationalism spirit embraced by the party.

The Law on Zakat No. 38/1999 had been subsequently amended by Law No. 23/2011 on Zakat Administration. This new law was enacted on 27 October 2011 and suddenly became as hot issue that raised public criticism. Many people, particularly private or non-state zakat agencies, held back to the law since it has introduced the new relation and new situation between state and the people in zakat management where the provisions were more in favor of the state (state-heavy). The State tried to centralize the zakat management in Indonesia through independent agency created by state namely BAZNAS, while the private zakat agencies treated only as supporting agents. Moreover, the collection and disbursement of zakat money without state’s written approval are considered as a crime (Articles 38 to 41 of the said law).

Meanwhile, The Law on Wakaf135 No. 41/2004 states that wakaf as an Islamic institution has economic potential and benefit that need to be effectively and efficiently administered solely for the sake of worship and religious interest as well as to promote people welfare in Indonesia. Article 5 mentions of the said law stated that wakaf is established for economic benefit and general welfare. Regarding the utilization of wakaf, Article 22 of the same law further elaborates that the utilization of wakaf treasure can only be done for: (i). Infrastructures and activities of worship, (ii) infrastructures and activities of education and health, (iii) Assistance to the poor, unaccompanied children, orphans, scholarship, (iv) promoting and enhancing Muslim’s economy, and (v) other general welfare compatible with Sharia and national laws.

Furthermore, The Law No. 21 year 2008 on Islamic Banking System also clearly mentions in Article 4 that Islamic/Sharia Bank’s obligation is to collect and disburse people’s funds. Islamic/Sharia Bank can also function as a Baitul Maal136 institution by receiving funds originated from zakat, infaq, shadaqah, hibah or other social funds and disburse them to the organizations responsible to administer social funds. Also, the Islamic Banks are authorized to collect social funds originated from cash wakaf and transfer them to wakaf organizer (nazhir) according to the intention of the givers.

Regarding zakat management and the relation between state and the people, Salim (2008: 12) mentions that the Qur’an does not elaborate the

135

Wakaf or waqf is a donation given by muslim people in the form of land, building, house and other immovable things to the God (Allah SWT) merely for the sake of worship, to benefit the community. Mostly wakaf donation are in the form of land or building which are subsequently transformed into Mosque (mosque), Islamic Schools, hospital and other public facilities.

136

Literally means House of Wealth or House of Treasury.

provisions on zakat management and enforcement. In fact, there is no clear directive as to whether to centralize or decentralize, institutionalize or personalize the application of zakat. Although the Qur’an mentions eight recipients of zakat including zakat agency or zakat collectors (al amilin alayha), there is no further instruction and elaboration on zakat collection, obligation to pay their zakat to certain agency, or possibility to give their zakat directly to the poor and needy. The application of zakat in the modern period has never been the same from one Muslim country to another. Practices range from complete incorporation of zakat as a regular tax of the Islamic states (such as in Pakisan, Sudan, Libya, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia) to the establishment of intermediary financial institutions that receive voluntary payments of zakat (like in Jordan, Egypt, Bahrain, Kuwait and Indonesia), to the disbursement of zakat according to the individual’s private conscience (like in Morocco and Oman).

There are many cases in Indonesia related to zakat mismanagement (zakat disbursement) and zakat policies like in Pasuruan (East Java Province) in 2008, in Jakarta 2009, in Makassar (South Sulawesi Province) 2012 and 2013 respectively, also the Massive protests related to Regent Decree on Zakat Payment of Civil Servants took place in Lombok Timur Regency (2005), in Malang (East Java Province 2011) and in Pekanbaru Riau Province (2013)137. All the cases show that zakat management and zakat policies in Indonesia are not properly managed and regulated. Hence, they are subject to criticism by some parties.

For example, at the first case, a wealthy and pious man in Pasuruan Regency, East Java, disbursed his zakat money directly to poor people around his residence. This action lead to 40 human casualties since people fought, pushed, and hit each other in order to get the zakat money at first chance.

The second case occurred right after the Islamic Holy Day (Idul Fitri) in September 2009. Jakarta Provincial Governor at that time, Fauzi Bowo, disbursed zakat money directly to the people who massively gathered in front of Jakarta Government Provincial Office at Jalan Medan Merdeka Selatan. People pushed, kicked and stampeded due the irresponsible rumors that the amount of zakat money was insufficient. Nobody was killed, but many people were taken to hospital due to severe injuries. Another case took place during Ramadan month (August 2012 and July 2013) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, when a rich man directly distribute his

137

INFOZ magazine (20th Edition December 2013), a magazine owned by Forum Zakat revealed that in Pekanbaru, Riau Province and Malang City, East Java province, people strongly protested the regulations that oblige civil servants to deduct 2.5 percent of their monthly salary as zakat money and disburse them to state-based zakat agencies.

zakat to the poor people for the amount of IDR10000/each, which also caused stampede and injuries to many people.

Last case related to zakat disbursement took place in Lombok Timur Regency, West Nusa Tenggara Province. The teachers, who were also civil servant within the region, launched a mass protest against the enforcement of Lombok Timur Regent Decree No. 17/2003 as an implementing regulation to Lombok Timur Local Ordinances No. 9/ 2002 on Zakat. The Regent Decree obliged all Muslim civil servants (including teachers) to pay the zakat money to designated state-based zakat agency. The payment of zakat carried out by automatically deduct the amount of 2.5 percent of their monthly salary. The decree soon triggered a massive protest. The civil servant teachers conducted a strike for several days and pushed the Regent to revoke the decree. The cause of this resistance was due to the fact that not of all them are muzakki or zakat payers. Half of the teachers earned low salary and had a lot of debt, therefore, they are not qualified to be zakat payers (Salim, 2008: 19). Salim (2008) later claims that the Regent Decree violates Muslim individual’s right on freedom to choose the method of payment of zakat, they cannot freely disburse their own zakat money due to uniform method of payment imposed by the Regent Decree.

Thus, it is clear that even in predominated Muslim country like Indonesia, the implementation of an Islamic economy instrument, like zakat, is not that easy. Hooker (2008) mentioned that when it comes to relation between zakat and tax, it is revealed that the characteristics of zakat present problems for the contemporary nation-states The individual Muslim is no longer just a Muslim, he or she is also a citizen, and therefore subject to the secular laws of the state. Zakat is a tax, and taxes are a state matter with their own laws (Hooker, 2008: 32).

Other problems related to zakat management are the methods of payment and disbursement. The fatwa138 from the 1970s through to the present have always insisted that payment should be personal, and hence that individuals should be able to choose the amount and method of payment (Hooker, 2003: 11). Zakat has two components: fitrah, a small sum paid as part of one’s religious obligations at Ramadan, and maal, a larger sum based on one’s disposable income. Fitrah is always paid by Muslims. However, the state did not intervene seriously in the collection of zakat maal until 1999, the year when the first national Law of Zakat was enacted (Hooker, 2008: 33).

138

Fatawa or fatwa is a judgment made by Muslim Scholar (ulama) on certain issues upon request by muslim people or initiative made by board of ulama to resolve a problem or provide an Islamic legal views on certain issues.

A national system of zakat was introduced in 1999 under the Zakat Management Law (No. 38 year 1999). It attempted to do two things: first, to institute an effective nation-wide system for the collection and distribution of zakat, and second, to reconcile the state and private systems through the provision of a common administrative framework. The law permits the collection of zakat by two sort of agencies: a national Zakat Agency Board (Badan Amil Zakat/BAZ) and private Zakat Agencies (Lembaga Amil Zakat/ LAZ). The latter includes organizations of varying sizes and capacities. There is no machinery to compel payment, although some districts and city authorities have been trying to do so in the case of civil servants. In theory, the amounts paid in zakat are deductible from income tax (Hooker, 2008: 33).

Unfortunately, the new law on zakat management No. 23/2011 and its implementing regulation, Government Regulation (Peraturan Pemerintah) No. 14/ 2014139 have reduced public participation in zakat management. The said laws stipulate that Badan Amil Zakat Nasional (National Zakat Agency) is set as the primary zakat administrator in Indonesia. It may have branches in provinces and cities/ regencies. This unequal position left the private zakat agencies as only the supporting agents in zakat management. They may collect zakat only if they were officially acknowledged by the National Zakat Agency (BAZNAS). The previous law of 1999 did not establish such unequal position. Instead the 1999 law acknowledged the more flexible room for public participation. Therefore, the coalition of non-state zakat agencies which felt that they were discriminated by the law later challenged this new zakat law by filing a judicial review of Law No. 23/2011 to Indonesian Constitutional Court on 16 August 2012 followed by a judicial review of Peraturan Pemerintah (Government Regulation) No. 14/2014 to Indonesian Supreme Court on 17 July 2014.

The aforementioned discourses regarding Islamic social security laws (particularly zakat) and its implementation in Indonesia have shown the complex and complicated manner of the institutionalization of Islamic-based social security instrument into a non-Islamic country. The state, people, and other stakeholders in this discourse must deal with these circumstances and harmonize various laws in multicultural situation including to human rights, which seemed to be a relatively new issue for many Indonesians. Moreover, the institutionalization also bring forth contestation. Contestation between state and civil society as well as

139

The new law on Zakat Management No. 23 year 2011 is an amendment to the old zakat law No. 38 year 1999. It was passed by Indonesian parliament on 27 October 2011 and the Government Regulation No. 14/2014 was enacted by President of Indonesia on 14 February 2014.

contestation within state apparatus in administering zakat affairs. Hence, institutionalization of zakat in Indonesia has presented not just religious issues but also a socio-political dynamic within it.

CHAPTER II

WHAT IS ZAKAT

II.1. Introduction

This chapter is intended to discuss zakat as Islamic economy instrument by exploring the Islamic social security instruments, the origin and background of zakat in Islamic teaching and Islamic history, and the basic concepts of zakat among other Islamic economy instruments.

The next part will describe about how zakat was managed and distributed by religious institutions both in Islamic history as well as in Indonesia. The last part deals with the analysis about why the state of Indonesia interested in administering zakat affairs.

Administration of zakat by secular (or semi secular state) like Indonesia is an interesting thing to be studied since zakat is a divine religious instrument intended to uphold social justice. Interestingly, Indonesia is not a state based on religion, although considered as the most predominantly muslim country in the world.

II.2. Zakat: Conceptual Basis

Islam is among the world major religion with around 1.5 billions of disciples all over the world. Not just a religion, Islam is a way of life, a guidance, a set of laws and complex system to govern Muslim’s entire life. The main sources of Islamic laws are the Holy Qur’an (Koran) and the Prophet Muhammad’s speech and behaviors (usually called as Sunnah or Hadits). Other important sources are muslim scholars’ thought and opinions (qiyas and ijtihad) which can be classified into several main school of thoughts. As a religion and a complex system of life, Islam is both a relationship between human beings and the God (Allah), between human themselves (muamalah) and between human beings to other living creatures, the entire planets.

The relationship between human and the God (habluminallah) is represented at the terminology of ‘ibadah’. Ibadah consists of series of activities such as taking a pledge (syahadah) that Allah is the one and only God and that Prophet Muhammad is Allah’s messenger, observing prayer (shalat), fasting, paying zakat, and doing pilgrimage (hajj) to Makkah if a Muslim is able and adequatet.

Islamic social and economic systems are both ibadah and muamalah. They reflect the relation between Muslim and the God (Allah) namely ibadah (or worship) and reflect the relation among Muslims (muamalah). Ibadah and muamalah integrates two dimensions of muslims’life. Therefore, discussion about Islamic social security should also consider its dimension as both profane and divine.

Rehman and Askari (2010: 7) mentioned thatIslam unites ethical principles with institutional measures (laws and rules) to create a framework for how an Islamic inspired economy and society should function. Institutions proposed by Islam relating to governance, social solidarity, cooperation and justice are designed to achieve economic development and growth. The essence of an Islamic society is that it is a rule-based system, centering on the concept of justice (Al’Adl’). Broad measures to address perceived resource scarcity and to achieve an equitable distribution of wealth and resource under the rubric of justice are three-fold : a) the fostering of ethical and moral values such as justice, equality, honesty, etc, b) economic tools and instruments such as zakah, sadaqah, and inheritance and property laws, and c) the development of the institutional capacity and political will to insure that these principle and norms are adequately upheld. At the core of the model is the principle of justice while the principle equity, fiscal prudence, respect of property rights and hard work branch out from this central theme (Rehman and Askari, 2010: 7).

In Islam, Zakat is known as a tax-like mechanism to distribute wealth to the poor. Zakat accounts for 2.5 percent of the wealth and savings which have remained constant for one full year. In Arabic, the term Zakat is derived from the phrase Zaka which means growth, pure and blessed. The meaning of growth in this context is to grow up and develop human dignity (Djamil,2004 in Mintarti,2011 : 83). The goal of zakat in Islam is not just to help the poor people, but to lift the people up higher than their wealth. So the people can freely manage but not driven by wealth. Zakat aims to liberate the soul of the people from their wealth. The worst of the man are those who are driven by wealth and render the wealth as their God (Qaradhawi, 1988 in Mintarti,2011 : 83). Qaradhawi further stated that zakat is empowerment. Zakat empowers the weak people. Hence, zakat must be apprehended as driving force, restorating force and promoting the wellbeing of its recipients (Djamil,2004 in Mintarti, 2011 : 83).

and other worldly desires as it builds a sense of responsibility towards those who are in need. Zakat is also a mechanism to eradicate poverty and sustain good quality lives for people (Yementimes Staff, 2008).

The concept and principle of justice are among the underlying idea of Islamic social security instrument. And so is zakat that is intended to uphold social justice and income distribution. Zakat is therefore, an obligation of Muslims to give a specific amount of their wealth with certain condition and requirements to beneficiaries called mustahiq (Al Qardhawi in Salleh and Rahman, 2011: 7). The concept of zakat exemplifies Islam’s strong concern with social and economic justice. According to Arif (in Saleh, 2011: 7) zakat serves as an ‘equitable distribution of wealth and income, which is enforced through moral obligation and fiscal measures.” Zakat is monetary devotion based on the idea that all things belong to Allah (God), and that wealth is therefore positioned at the disposal of mankind as a trust. The passion of human beings is sanctified through earmarking a proportion of the wealth for the distressed and needy as mandated in the Qur’an. Zakat does not only purify property, but also purifies one from selfishness and greed. The recipients of Zakat also purify themselves from envy, jealousy, hatred and uneasiness as it will foster goodwill, gratefulness and warm wishes for the contributors (Dhar, 2013).

In Islam, wealth is a means and not an end. And the management thereof should be for the benefit of the community, directed to please God, and aimed to the afterlife. As wealth is considered as belongings of God, with mankind nothing other than its temporary guardian, social responsibility and accountability are essential to this concept (Wouters in Ahmed, 2013: 150).

The idea of zakat is, therefore, derived from the idea, That your wealth is actually not yours. They belong to the God. And indeed, in your wealth, there is some parts belonged to the community.140

In wider perspective, zakat is intended as a means to achieve social justice. Social justice implies that every individual in a community is assured of minimum means of livelihood. Al-Shafi’I, Malik and Ibn Hanbal141 stressed that the fulfillment of one’s basic needs is the main criterion for the distribution of zakat. Failure to satisfy the basic needs of the masses can lead to the occurrence of poverty and wide disparity between the rich and the poor

140

Paul Wouters (in Ahmed, 2013) later mentioned that Islamic wealth management acknowledges responsibility toward the community and redistribution as key concepts at the very start of the chain and not as end result.

141

(Hassan in Sadeq, 1991: 213). Related to this discourse, Mintarti (2011:78) believes that zakat in Islam has two meanings: theological-individual and social meanings. Theological-individual meaning means that zakat is intended to purify wealth and soul. In this array, the zakat affects only to individuals and their relation to the God (Allah). However, the social meaning of zakat means that zakat is also has social dimension, namely to eradicate poverty and social injustice. Zakat money will be circulated to other people, not just enjoyed by the rich. And here is the essence of zakat: the distribution of income and wealth. The prophet Muhammad PBUH said: "Any owner of gold and silver who does not deliver from them their right, on the Day of Qiyamah (Day of Judgment), (the gold and silver) will be shaped as foils of fire. Then it will be heated in the fire of Hell, (and) then with it he will be ironed on his side, his forehead, and his back" (narrated by Muslim). Qardhawi, a well-known Muslim scholar, states (1993:62) that zakat is obligatory after the holy Qur’an verses which were delivered to Prophet Muhammad during the Medina period. The verse on the obligation of zakat is quite clear and the order and instruction to pay zakat money is firm. The order to pay zakat is in line with the order to perform shalat (prayer).

Zakat is obligatory when a certain amount of money or nisab is reached or exceeded. Zakat is not obligatory if the amount owned is less than this nisab. The nisab (or minimum amount) of gold and golden currency is 20 mithqal (One mithqal is approximately 4.25 grams), or approximately 85 grams of pure gold. The nisab of silver and silver currency is 200 dirhams, which is approximately 595 grams of pure silver. The nisab of other kinds of money and currency is to be scaled to that of gold, or 85 grams of pure gold. This means that the nisab of money is the price of 85 grams of pure gold, on the day in which Zakat is paid.

Nonetheless, the word ‘Zakat’ which means purification is becoming obligatory according to Qur’anic verse and it is the main form of alm which is obligatory. For this reason zakat remains obligatory even if there are no needy persons in a community. The system of zakat is designed to help the poor and the needy, and it is a highly desirable characteristic of the believers that in addition to prayers and other acts of worships they are always conscious of this duty, and this is the best strategy to remove social-economical injustice and disparities (Wahidi, 2012 : 63).

salaries, inheritance, grants,etc.), the owner needs to add the increase to the nisab amount owned at the beginning of the year, then pay Zakat, 2.5 percent of the total at the end of the lunar year. (There are small differences in the fiqh schools here).142

In Indonesian situation, Indonesian compilation on Syariah Economic (Kompilasi Hukum Ekonomi Syariah, 2009) mentioned in Article 668 (2) that zakat is part of wealth obliged to be disbursed by a Muslim or Muslim’s institution to those who deserve to receive it. Furthermore, Article 679 (1) of the compilation stated that zakat is counted from the whole income excluded the living costs. The group of persons deserve to receive zakat money are called as mustahiq (from Arabic word, means ‘those who deserve’). The mustahiq of zakat has already been stipulated in the holy Qur’an.

Another important thing in wealth distribution in Islam is Baitul Maal (House of Wealth). Baitul Maal is the manifestation of an Islamic philosophical concept built upon three main principles relating to the concepts of wealth, trust, and socio-economic justice. Being a manifestation rather than a fixed institution in Islam. Baitul Maal can involve either one or more institutions developed to achieve the ends provided in the concepts of wealth, trust, and socio-economic justice (Ghazali, 1990: 46).

The attainment of socio-economic justice is an immediate objective of Baitul Maal. This is clear since Baitul Maal bears the responsibility of undertaking the workings of the society’s fiscal system, development planning and welfare provisions. The structure of Baitul Maal can be in the form of one or more institutions, it can be said that the Baitul Maal will act as a treasury complemented by a full-fledged administrative machinery entrusted with the task of planning and distribution of society’s wealth in the whole socio-economic and political set up of the nation (Ghazali,1990: 46 – 47).

Bait in Arabic means a house and maal is property. Baitul maal, therefore, means the treasury of the public. The very concept of the Baitul Maal is the concept of trust, the wealth of Baitul Maal is to be treated as Allah’s wealth or Muslim’s wealth, as against the imperial treasury as used to be known during the medieval period. This concept implied that monies paid into the treasury were Allah’s trust and the common property of all the Muslims and that the Caliph or a ruler was in the position of a trustee, whose duty was to spend the treasury on the common concerns of all Muslims while allowing for himself nothing more than a fixed stipend (Doi, 2002: 388).

The concept of Islamic state and the establishment of Baitul Maal are inseparable. The word Baitul Maal does not occur in the Qur’an as such, but the sources from which the funds flow into Baitul Maal are all mentioned in one way or the other in the Holy Qur’an. The institution, however, is

142

mentioned frequently in the al-hadits of the prophet. Baitul Maal came into being in the life term of the Prophet immediately after the coming into existence of the Islamic State of Medina. It developed fully in the time of the Rashidun Caliphs, particularly the second Caliph Umar bin Al Khattab (Doi, 2002).

The sources from which funds are collected in the Baitul Maal are as follows (Doi, 2002 and Ghazali, 1990):

a. Zakat, One of the pillars of Islam which demands that 2.5 percent of 1/40 part of our savings should be given the poor and needy. These funds were collected and managed in the Baitul Maal of Muslims for the welfare of the ummah. The zakat is only payable by Muslim subjects from their cash property, trade merchandise and herds of cattle. The non-Muslims are exempted from the payment of zakat.

b. Sadaqah or infaq, It is a voluntary charity given by individuals over and above the payment of the compulsory zakat to relieve the problem and sufferings of fellow-human beings. According to the hadits, sadaqah must be given in such a way that even the left hand or the donor does not know what the right hand gives.

c. Jizzyah, the jizzyah is an annual tax levied on non-Muslim citizens living in the Islamic state. Just as the Muslims pay the compulsory zakat, the non-Muslims pay the jizzyah. In return, it will be the duty of the Muslim state to protect their lives and property, like any Muslim citizen. The jizyah collected will go to the Baitul Maal.143

d. Kharaj, a tax levied on the producer of the landed property owned by the non-Muslim in the Islamic state. Just as the Muslim pay ushr, the non-Muslim are supposed to pay kharaj to the baitul maal.

e. Ushr,, the taxation to be paid on the produce of the landed property of the Muslims at the rate of ten percent if it through natural rainfall in an Islamic state. But if the water has been supplied through irrigation, it will be at the rate of 20 percent. This amount is to be paid in the Baitul Maal which will cater for the welfare and needs of the individuals as well as the ummah as a whole.

143

f. Chums, a certain percentage of whatever a Muslim army gets as a booty (ghanimah) after fighting war with enemies and gaining victory over them. Likewise, a certain percentage of the income from the natural resources, mines, petroleum, and other natural hidden treasures owned by individuals is also called khumus. Such proceeds go to the Baitul Maal and is used for the welfare of the nation.

g. Fay, a property captured from the enemy forces without

fighting any battles with them. Such property, if acquired, will go to the central funds of the Baitul Maal.

h. Dara’ib, are the general taxes which the Islamic state deems fit to impose on its citizens to carry out some public welfare works or when the state needs funds in the event of any emergency. The proceeds go to the Baitul Maal.

i. Waqf, these are the religious trust and the proceeds from these religious trust properties go to the Baitul Maal.

j. Ushur, constitutes the revenue collected from the proceeds out of trade and business carried out by all the citizens of the Islamic state irrespective of their religious beliefs. This revenue also goes to the Baitul Maal.

k. Kiraal Ard, the income generated from the government and it goes to the central funds of the Baitul Maal.

l. Amwal al fadillah, any income from the government owned natural resources is called amwal al fadhilah and goes to the Baitul Maal.

This research focuses only on zakat for the following reasons: zakat is considered as special wealth and its disbursement must meet some restrictions and limitations. This is partly because zakat money is mandatory, while wealth (like in infaq,shadaqah or other social funds which are not mandatory) has no restrictions or specific categories in disbursement. People have their own freedom to dispense their own money either by themselves or through social institutions, and there are no specific categories of recipients (like in zakat recipients). For zakat disbursement, the Qur’an and history of Islam tell us that zakat should be managed by power. Power in this meaning could be state or state-based institutions. The role of the state in zakat affairs and its management to secularize zakat among other social security instruments in a multicultural society like Indonesia are the reasons why studying zakat in Indonesian context is always interesting.

Muslim jurist are unanimous in their opinion that Muslims as well as non Muslims are to be treated equally in their rights to be looked after from the funds of Baitul Maal in any Muslim State.144 However, whether non muslim

144

deserves to be zakat recipients, muslim scholars have different opinions. Zakat is only given by Muslims and Non Muslims are exempted from it. Imam Zufar (in Do’i, 1994) thinks that it is lawful to give zakat to the poor and destitute dhimmis145 in order to draw them closer to Muslims. He claims that although Non Muslims have not contributed anything to zakat, they still can be the recipients from the zakat funds. Another group of jurists only allows the payment of zakat to the poor dhimmis when one can not find any poor Muslim recipients, while there are still some jurists belonging to different schools who insist that zakat should not be given to Non-Muslims (Do’i, 1994 : 110).

II.3. Zakat as Islamic Social Fund

The original teaching of Islam about zakat clearly classifies zakat as obligatory for Muslim people. Zakat is obligatory for Muslims who meet certain requirements where they must set aside their money in certain amount and for certain period as stipulated by Islamic teaching, to be disbursed to needy people (zakat recipients). Saidi in Kurniawati et.al. (2004:1) mentioned that public fund in Islam can be differentiated to three categories i.e. for social, professional, and commercial purposes. Social fund is fund intended as social assistance, either directly provided to the needy people or through social organization channel which will subsequently be delivered to the needy people without personal or political interests. Professional fund is a fund that needs special authority and skills since the fund is intended as rolling fund. The best example for professional fund is wakaf fund. Meanwhile, commercial funds are funds intended for investment or business purposes. Fahmi (2010) asserts that zakat is the most important social security in Islam, while Sudewo (2007) indicates that zakat is the most important political decision in Islam.

The main sources for social fund in Islam are Zakat, Infaq and Shadaqah. Zakat is the particular form of money which have considerable symbolic importance because it is one of the five pillars of Islam and thus an individual obligation to God. It is also one of only two of the pillars directly involving money (the other is hajj). The Five Pillars of Islam (or ‘Arkanal Islam’ in Arabic, ‘Rukun Islam’ in Indonesian) are five expressions as follows : As-shahadah (witnessing) that Allah is one and Prophet Muhammad is the last prophet of Allah SWT, prayers (shalat) regularly, Zakat, Fasting in the month of Ramadhan (shaum) and pilgrimage or hajj at Baitullah (kaba) in Makkah.

Nafik (in IMZ, 2011 : 175) interpolates that zakat can be utilized as a welfare indicator, a means to narrow economic gap. An instrument for growth

145

and economic empowerment, and a tool to control the economy. Zakat will have long- term impact should it is employed for empowering the mustahiq (zakat recipients), not just a charity. The charity approach of zakat will render the zakat recipients unproductive and will affect only to short term economic impact.

Nafik (in IMZ, 2011 : 181) further claims that zakat works as welfare indicator universaly, everytime, everywhere and at all economic systems. Somebody will become as zakat payer (muzakki) when his/ her wealth has reached the certain limit (nisab). Somebody who are categorized as muzakkican be categorized as wealthy man. Why? In counting the nisab, the zakatable wealth are those which are already deducted for regular cost or regular consumption. If the amount of remaining money still higher than nisab limit after being deducted for regular cost, then he or she can be considered as muzakki or ‘wealth person’.

Research conducted by Laila & Amalia (in IMZ, 2011 : 229 – 251) and Mintarti (in IMZ, 2011 : 43) shown that empowerment programs by utilizing zakat money conducted by non-state zakat agency in Indonesia has successfully empower poor people. The indicator is the income of zakat recipients is increasing. The zakat recipients’ increment of salary, in turn, will also affect their ability to meet the basic needs such as food, clothes, house, education, health and recreation. Furthermore, the facilitation program conducted by non-state zakat agency has successfully increased the skills, knowledge and attitude of the mustahiq. Further, zakat can be employed to transform and empower a community.146

Beik (2009: 47) who studied the role of Dompet Dhuafa Republika in alleviating poverty through zakat also inferred that zakat can reduce the number of poor families from 84 percent to 74 percent (in a research area). Research conducted by Hartoyo and Purnamasari (2010) in Garut Regency, West Java Province in 2010 also concluded that zakat (in this case is zakat recipients of Lembaga Amil Zakat (non-state zakat agency) Persis) can diminish the poverty gap to 7.52 percent and elevate the income of its zakat recipients up to 3.70 percent. Another study conducted by Anriani (2010) in Bogor City, West Java Province (to the zakat recipients of Badan Amil Zakat Kota Bogor or Bogor City Zakat Agency) concluded that the zakat recipients (mustahiq) of BAZ Kota Bogor has diminished around 8.77 percent in 2010 after a few years became as zakat recipients. Tsani (2010) asserted that the zakat recipients (mustahiq) of BAZDA Lampung Selatan Regency, Lampung Province , In Malaysia, Ibrahim (2006 in Fahmi, 2010) found that zakat had

146

reduced the number of mustahiq (zakat recipients) in Selangor State from 62 percent to 47 percent.

Concerning the utilization of zakat, Mintarti (2011 : 77) mentions that among the goals of zakat is to combat the poverty by taking out the poor people from their poverty, to improve their quality of life and to transform the mustahiq (zakat recipients) into zakat payers (muzakki). Mintarti believes that zakat can empower people. Zakat-based community empowerment is done through developing economic and social improvement of poor people by instigating active participation of poor people, facilitated by amil who are also acting as facilitator of the program. Hence, the goals of zakat are no just to combat the poverty by providing temporary assistance but to extend the ownership and transforming mustahiq (zakat recipients) into muzakki (zakat payer).

II.4. Zakat and The Role of The State

Regarding the role of the state in wealth management, in this case is the practices of Baitul Maal (house of wealth), are different from time to time. During the life of Prophet Muhammad SAW period state expenditures were mostly for state defense, disbursement of zakat and ushr for those who were eligible, payment of civil servants, payment of state’s debts, and allowances for traveler (musafir), also for secondary needs such as supporting those who studied Islam in Medina, support for the guests and delegations, gifts for other governments, or to cover the debts of deceased men or women who were in poor condition and unable to pay their debts. To manage the incomes as well as the expenditures, Prophet Muhammad SAW assigned the Baitul Maal (Hidayat, 2009 : 116).

Meanwhile, Gamal Al Banna (2006 : 18) mentions that during the Medina period, source of state income was mainly from the zakat which was taken from the rich people and disbursed to poor people. However, zakat funds were not utilized for running the government. Also, the government did not collect the tax in Medina (Madinah). Zakat was not collected through force, but more on one’s sincerity.

mentioned in previous chapter, social security mechanism usually work to secure the health problem, accident, retirement, bereavement as well as to support the family who lost their loved ones (Al Banna, 2006 : 18).

Thereafter, to disburse the Baitul Maal’s treasure, The Caliph Umar ibn Khattab set up some departments , namely : (a) department of military services, (b) department of justice and execution, (c) department of education and Islamic development, (d) department of social security. Department of social security managed to distribute financial assistance to all poor and needy people as well as those who live in suffering. This department began to work as early as year 20 hijriah Islamic Year (or 630 AD) by assessing the needs of some people who had defended Islam, those who have family relationship to the Prophet Muhammad SAW147, women, children and slaves, they were all eligible to obtain social security from Baitul Maal (Al Banna, 2006 : 18).

Wahidi (2012) convinces that government of an Islamic State can collect zakat even by force for well being of society. This assumption is based on the historical holy war (jihad) announced by the first caliph Abubakar Asshidiq against the first aroused munafiq (hypocrite) Musailamah Al Kazab after very short time from the departure of Holy Prophet towards eternity. When this hypocrite heard about the sad departure he claimed that only the Prophet was authorized to collect zakat when he was not present anymore in this world nobody was obliged to pay zakat. The Caliph announced ‘jihad’ against Al Kazab as he refused to pay zakat.

However, in this contemporary world where some Muslims are not living in Muslim countries and some Muslim countries are not enacting Islamic Constitution, it is difficult to see the practice of Caliph Abubakr Asshidiq to collect zakat money by force shown by present Muslim rulers in Muslim countries. In some jurisdictions, collecting zakat by force even can be considered as violation to human rights and a threat to democracy. Regarding the role of the state in Islamic economy, Chapra (1992: 223) stated that the role of the state in an Islamic economy is not an ‘intervention’ which smacks of an underlying commitment to laissez-faire capitalism. It is also not in the nature of collectivization and regimentation which suppress freedom and sap individual initiative and enterprise. It is also not in the nature of the secularist welfare state which, for its aversion to value judgments and claims on resources, leads to macroeconomic imbalances. It is rather, a positive role, a moral obligation to help realize the well-being of all by ensuring a balance between private and social interest, maintaining the economic train

147