www.elsevier.com / locate / econbase

Gross employment flows in U.S. coal mining

a b,c ,

*

Timothy Dunne , David R. Merrell

a

Department of Economics, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 79013, USA

b

Carnegie Mellon University, School of Public Policy and Management, Hamburg Hall 238, 5000 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

c

Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC 20233, USA

Received 14 June 2000; accepted 6 December 2000

Abstract

This paper examines patterns of job creation and destruction in U.S. coal mining and compares those patterns to known regularities in U.S. manufacturing. Using a unique panel data set of coal mines from 1973 to 1996, this paper finds the following: annual employment flows in coal mining are substantially higher than in manufacturing, high job creation, destruction, and reallocation rates are attributable in part to mine openings and closings, a significant amount of job destruction and creation is attributable to temporary shutdowns and re-openings, and job destruction is counter-cyclical and more volatile than job creation. 2001 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Job creation / destruction; Gross employment flows; Entry; Exit

JEL classification: D21; J63

1

1. Introduction

Over the course of the last decade, economists have been increasingly interested in the

2

measurement and analysis of establishment and firm employment dynamics. Macroeconomists have shown great interest in analyzing job creation and job destruction as a mechanism to better understand

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 11-412-268-4070; fax: 1-412-268-7036. E-mail address: [email protected] (D.R. Merrell).

1

The results and findings herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official findings of the U.S. Bureau of the Census or the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration.

2

The recently published third volume of the Handbook of Labor Economics that has a separate chapter devoted to the employment flows literature evidences this fact. The chapter is entitled ‘‘Gross Job Flows’’ and is authored by Steven Davis and John Haltiwanger and appears in the Handbook of Labor Economics (1999), Volume 3B.

3

business cycles; the literature has focused on the asymmetries in the job creation and job destruction process over the business cycle. Labor economists have highlighted the importance of employment reallocation due to demand-side fluctuations–presenting important implications for analyzing worker

4

mobility, worker dislocations, and matching models of workers and firms. Industrial organization economists have used new data on establishment and firm entry, growth and exit to examine industrial

5

dynamics, patterns of industrial evolution, and productivity growth. In short, the development of new data sets that allow researchers to examine the employment dynamics of individual plants and firms has created new empirical insights that have formed the basis for a wide range of both theoretical and empirical studies.

This paper extends the literature on gross employment flows by using a new data series on job creation and job destruction for the U.S. coal mining sector. The previous U.S. literature on job creation and job destruction has focused predominately on manufacturing industries; see Davis and Haltiwanger (1992); Davis et al. (1996) and Dunne et al. (1989a). There is a small and growing literature examining non-manufacturing sectors stemming from work done by the U.S. Small Business Administration, Spletzer (2000), and by Foster et al. (1998). However, none of these studies is able to develop long annual time series on non-manufacturing industries. Hence, the time-series data on

6

non-manufacturing sectors in the U.S. is relatively scarce. This new data on the U.S. coal mining sector has the strengths of providing an annual time series of employment flows over a long period of time and of being able to study those changes outside of the manufacturing sector.

Moreover, coal mining has some interesting institutional features that may yield differences in the job creation and destruction series as compared to manufacturing. First, the life span of a coal mine is limited by remaining coal reserves. As reserves run out, mines (even very productive ones) are forced to close; see Merrell (1999). This suggests that mine openings and mine closings may play a larger role in employment reallocation in the mining sector as compared to manufacturing. In addition, coal mining has undergone dramatic changes in mine technology, mine type (underground versus surface), and locations (Western coal versus Appalachian coal)–yielding significant improvements in labor productivity. These changes have resulted in a substantial net decline in employment in the industry even though production has risen markedly.

2. Data and analysis

The data used in the analysis come from the Mine Safety and Health Administration’s (MSHA) data files on employment, hours, and production for all coal mines in the United States. Unlike other

3

Research in macroeconomics on employment flows include Caballero and Engel (1993); Caballero et al. (1997); and Campbell and Kuttner (1997).

4

For example, Hopenhayn and Rogerson (1993) examine interaction of government policy that reduces worker mobility and employment reallocation in a general equilibrium framework. Mortensen and Pissarides (1994) develop a model of unemployment and job creation and job destruction.

5

Industrial organization papers that examine employment dynamics include Evans (1987); Dunne et al. (1989b) and Troske (1996). Papers examining reallocation and productivity growth include Baily et al. (1992); Olley and Pakes (1996) and Aw et al. (1997).

6

data sources, the data on U.S. coal mining contains the statistical universe of mines in every year. In this paper, we will utilize the data on mine-level employment to construct measures of annual gross employment flows. Our approach will follow that of Davis and Haltiwanger (1992) and Davis et al. (1996) and define job creation (POS ) and job destruction (NEG ) as follows:it it

TEit2TEit21

where TE represents total employment at mine i in period t and TEit it21 represents total employment

7

at mine i in period t21; throughout, TE is measured in the first quarter of a year. TE includes total employment at the mine but does not include coal processing operations or white-collar workers. The POS variable is constructed for all plants with expanding employment between tit 21 and t, while NEG is constructed for all plants with contracting employment between tit 21 and t. The denominator used here is the same as Davis and Haltiwanger (1992) and represents the average employment at a mine in periods t and t21. This formulation constrains the job creation and job destruction rates to the interval [0,2] where an opening or closing mine has a job creation or destruction rate equal to two, repsectively. Finally, both POS and NEG are used to construct aggregate measures of job creationit it and job destruction. POS is the employment weighted average of job creation in period t, and NEG ist t the employment weighted average of job destruction in period t. In addition to the POS and NEGt t aggregate employment flow variables, we also construct the net employment growth rate in coal mining (NETt5POSt 2 NEG ) and total reallocation of employment across mines between tt 21 and t (REALt5POSt1NEG ). These are the main variables used throughout the analysis that follows.t

2.1. Aggregate trends

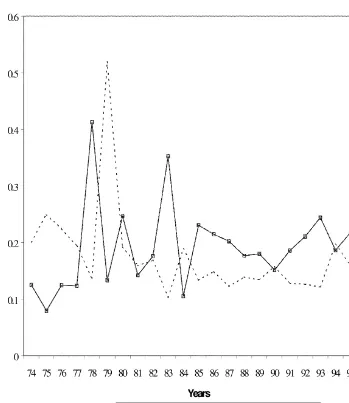

The job creation, job destruction, and reallocation series are presented in Table A.1 for the period 1973 through 1996. The median annual job creation rate is 0.158, while for job destruction the median rate is 0.186. Fig. 1 plots the job creation and destruction series for coal mining. Examining the job creation series, we see that job creation was relatively high in the 1970s, a period of rapidly rising energy prices, and yet job creation was relatively low in the 1980s and 1990s, a period of substantial employment decline in the coal mining sector. In general, the opposite patterns occur for the job destruction rates. It is generally lower in the 1970s and rises thereafter.

A few specific points are worth noting. First, the large spike in job destruction in 1977 accompanied by the large spike in job creation in 1978 is due to an industry strike that occurred in the 1977–1978

8

period. Second, the level of job creation and job destruction is much higher in coal mining than what

7

Throughout the paper, a first quarter to first quarter comparison is used. This is identical to the construction used by Davis et al. (1996).

8

Fig. 1. Job creation and job destruction in coal mining: 1973–1996.

is found in other sectors of the economy. In U.S. manufacturing, job creation and destruction rates

9

average around 0.09 and 0.10, respectively, for the 1970s and 1980s. Third, job destruction appears more cyclically sensitive than job creation. This is particularly true in the large (non-energy induced)

9

recession of 1982–1983. Job destruction increases markedly, while job creation falls modestly. If one computes the coefficient of variation for each series (omitting the strike years), one finds that the coefficient of variation for job destruction is 37.4% higher than the coefficient of variation for job creation (32.87 versus 23.92). Job destruction is more cyclically volatile than job creation–a finding

10

consistent with the U.S. manufacturing evidence.

With respect to the cyclicality of employment reallocation, we find that reallocation is negatively correlated with industry growth. That is, employment reallocation is counter-cyclical. The Pearson correlation (again, excluding strike years) between NET and REAL is estimated at 20.579 (.006). This is consistent with the known manufacturing patterns where employment reallocation is also found to be counter-cyclical, and this finding also agrees with the predictions of models of job creation and job destruction as offered by Caballero and Hammour (1994) and Campbell and Fisher (1997)–viz., that there should exist asymmetries in employment adjustment over the cycle resulting from asymmetric and non-convex adjustment costs. This will cause firms to concentrate their employment changes into discrete episodes since the opportunity cost (lost revenue) of restructuring

11

in an expansionary period is greater than the lost revenue in a contractionary period. Hence, firms will have a tendency to concentrate their employment restructuring episodes in downturns.

2.2. Mine openings and closings

Fig. 2 provides a breakdown of the employment flows by source: mine openings, mine closings, continuing mine expansion, and continuing mine contraction. One should be careful to note that we treat both a de novo mine and a re-opened mine as an opening, and a mine shutdown is considered a closing even if it is temporary. Basically, an opening is any mine that goes from zero to positive employment between t and t11, and a closing is any mine that goes from positive employment to zero employment between t and t11. Fig. 2 shows that the openings and closings are quite important in terms of job creation and job destruction. About two-thirds of job destruction is attributable to mine closure while about one-half of job creation is attributable to mine opening. The importance of closing mines is particularly pronounced in the late 1980s and 1990s, as job destruction due to mine closings is substantially higher in that period. The pattern of extensive job creation and job destruction due to openings and closings is starkly different than what is found in manufacturing. In manufacturing, job destruction due to closures accounts for about 23% of overall job destruction, and job creation due to openings accounts for 16% of total job creation; see Davis et al. (1996). Hence, openings and closings play a much more important role in reallocating employment in coal mining than would be found in manufacturing.

A key difference between manufacturing and mining is that a significant fraction of mine closings and openings are temporary. Table 1 provides some basic information regarding the nature of mine re-openings and temporary closings for five sample years: 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995. Column 2 shows the percent of closing mines in a year that will re-open in the future. Data for 1995 will be censored quite heavily; so it is not presented. Table 1 shows that a substantial fraction of closing mines will re-open. For example, in 1985, 28.4% of the mines that close that year will re-open

10

Note, however, that the 1974–1975 recession is not apparent in the coal data. This is because this recession was energy related, and energy related industries felt little of the impact of the recession on output or employment.

11

Fig. 2. Employment flows–continuing mines, openings and closings 1973 to 1996.

between 1986 and 1996 (the last year of the data). A similar pattern is observed for mine re-openings. Column 3 shows the percent of opening mines that operated previously. Again, because our data go back only to 1973, data for 1975 will be censored heavily and will not be presented. In 1985, slightly

Table 1

Temporary mine closings and mine re-openings Year Percent of closing Percent of opening

mines that will mines that were re-open previously in operation

1975 34.0 N /A

1980 27.6 37.1

1985 28.4 41.4

1990 19.6 37.4

over 40% of opening mines had been operating in the 1973–1983 period. On an employment weighted basis, temporary closings account for approximately 20% to 30% of job destruction attributable to plant closings. In the case of mine openings, re-openings account for 40% to 50% of job creation due to mine openings. Again, it is difficult to be overly precise here because of censoring, but the key point is that temporary mine closings and mine re-openings are an important feature of job creation and job destruction in the coal mining sector.

3. Conclusion

This paper documents the patterns of employment flows in the U.S. coal mining sector. The contributions of the paper are threefold. First, the paper develops a new data series on employment flows for the coal mining sector where previous studies have focused predominately on the manufacturing sector or on particular states. Coal mining has features that generate substantially different patterns than manufacturing. In particular, mine openings and closings play a dominant role in job creation and job destruction; this is not the case in manufacturing. Second, temporary closings and mine reopenings are important sources of gross employment flows. This suggests that either local shocks that mines receive are either large or that costs of temporary shutdown and re-opening are relatively low. Finally, while there are important differences between mining and manufacturing, there are also some striking similarities. The level of job creation and job destruction greatly exceeds the net changes, as is true in manufacturing. In addition, employment reallocation is strongly counter-cyclical and more volatile–consistent with the manufacturing evidence.

Appendix A. Table A.1. Employment Flows in Coal Mining: 1973–1996

Year Job Job Net Employment

creation destruction employment reallocation

rate rate growth rate

1974 0.201 0.125 0.076 0.326

1975 0.249 0.080 0.170 0.329

1976 0.224 0.125 0.100 0.349

1977 0.194 0.123 0.070 0.317

1978 0.136 0.412 20.276 0.549

1979 0.519 0.133 0.386 0.652

1980 0.193 0.247 20.054 0.439

1981 0.159 0.142 0.017 0.301

1982 0.168 0.176 20.007 0.344

1983 0.103 0.352 20.250 0.455

1984 0.189 0.105 0.084 0.294

1985 0.134 0.231 20.097 0.364

0.324

Aw, B.-Y., Chen, T.-J., Roberts, M., 1997. Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials, turnover, and exports in taiwanese manufacturing. In: Mimeo. The Pennsylvania State University.

Baily, M., Hulten, C., Campbell, D., 1992. Productivity dynamics in manufacturing plants. In: Brookings Papers On Economic Activity. Microeconomics, pp. 187–267.

Caballero, R., Engel, E., 1993. Microeconomic adjustment hazards and aggregate dynamics. Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, 359–383.

Caballero, R., Engel, E., Haltiwanger, J., 1997. Aggregate employment dynamics: Building from microeconomic evidence. American Economic Review 87, 115–137.

Caballero, R., Hammour, M., 1994. The cleansing effect of recessions. American Economic Review 84, 1350–1368. Campbell, J., Fisher, J., 1997. Understanding aggregate job flows. In: Economic Perspectives, Vol. 21. Federal Reserve Bank

of Chicago, pp. 19–37.

Campbell, J., Kuttner, K., 1996. Macroeconomic effects of employment reallocation. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 44, 87–116.

Davis, S., Haltiwanger, J., 1992. Gross job creation, gross job destruction, and employment reallocation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, 819–863.

Davis, S., Haltiwanger, J., Schuh, S., 1996. In: Job Creation and Destruction. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M., Samuelson, L., 1989a. The growth and failure of US manufacturing plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics 104, 671–698.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M., Samuelson, L., 1989b. Plant turnover and gross employment flows in the US manufacturing sector. Journal of Labor Economics 7, 48–71.

Energy Information Administration, 1995. In: Coal Data: A Reference, DOE / EIA-0064(93), Distribution Category UC-98. Evans, D., 1987. Test of alternative theories of firm growth. Journal of Political Economy 95, 657–674.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., Krizan, C., 1998. Aggregate productivity growth: lessons from microeconomic evidence. In: Mimeo. University of Maryland.

Hopenhayn, H., Rogerson, R., 1993. Job turnover and policy evaluation: A general equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy 101, 915–938.

Merrell, D., 1999. Implications of resource exhaustion on exit patterns in U.S. coal mining. In: Mimeo. H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy and Management, Carnegie Mellon University.

Mortensen, D., Pissarides, C., 1994. Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. Review of Economic Studies 61, 397–415.

Olley, S., Pakes, A., 1996. The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica 64, 1263–1297.

Spletzer, J., 2000. The contribution of establishment births and deaths to employment growth. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 18, 113–126.