ENHANCING STUDENTS’ LEARNING AUTONOMY

THROUGH THE COLLABORATIVE AUDIO-JOURNAL PROJECT IN LISTENING COMPREHENSIONIII

A Thesis

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree

in English Language Education

By Priyatno Ardi

Student Number: 031214097

ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA

“when you want something, all the universe conspires

in helping you to achieve it”

(Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist)

I dedicate this thesis to my future life

ABSTRACT

Ardi, Priyatno. 2007. Enhancing Students’ Learning Autonomy through the Collaborative Audio-Journal Project in Listening Comprehension III. Yogyakarta: Sanata Dharma University.

Learning autonomy is one of formal educational goals, supporting the idea that learning is a lifelong process hence. The field of English language teaching and learning in Indonesia needs to promote learning autonomy to assist the students to face globalization. In so doing, the teacher provides the autonomous learning setting encouraging the students to actively involve in the learning processes. Since the autonomous teacher tends to encourage the students to learn autonomously, addressing the autonomous learning to English teacher candidates becomes the first step to enhance students’ learning autonomy in Indonesia.

The present study investigated the innovation of English learning program, namely the collaborative audio-journal project, implemented in Listening Comprehension III of the English Language Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. It was to increase students’ learning autonomy. There were three questions addressed. The first question discussed the procedures of the implementation of the collaborative audio-journal project. The second and third question explored students’ experiences in the project accomplishment. The second question talked about students’ perceptions toward the project, whereas the third question figured out the employed metacognitive strategies.

To answer the research questions, the researcher employed a qualitative method. Two instruments were used to obtain the data, namely reflection sheet and interview. There were three results obtained from the study. First, based on the discussion of the procedures, the project was indeed intended to enhance students’ learning autonomy through the small group interaction bearing self-interdependence and the reflection raising self-awareness. Second, the students felt the anxiety in their first encounter with the project but they changed it into the enjoyment as they went through it. Third, students employed the metacognitive strategies, including planning, problem solving, monitoring, and evaluating. The planning proposed by the students were time and quality, creativity, and strategy. The students encountered the constraints, such as facilities, time management, language proficiency, and restlessness, which entailed problem solving strategies. The students monitored the project by rereading, re-listening, and comparing. Lastly, the students conducted self-evaluation on the process and the product.

The researcher concluded three important points. First, learning autonomy enhanced through the project was reactive autonomy, functioning as the beginning of students’ proactive autonomy in their future learning. Second, students’ developmental perceptions suggested that motivation and willingness increase. Third, the employed metacognitive strategies implied that the students controlled their learning management. Suggestions were given to (1) the teacher to give sufficient feedback on students’ journal responses, (2) the students to keep on managing their learning, and (3) future researchers on learning autonomy to further investigate the psychological constructs related to the development of learning autonomy.

ABSTRAK

Ardi, Priyatno. 2007. Enhancing Students’ Learning Autonomy through the Collaborative Audio-Journal Project in Listening Comprehension III. Yogyakarta: Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Kemandirian belajar menjadi salah satu tujuan pendidikan formal yang mendukung pembelajaran sepanjang hayat. Bidang pengajaran dan pembelajaran bahasa Inggris di Indonesia perlu mengembangkan kemandirian belajar untuk mempersiapkan para siswa menghadapi era globalisasi. Dalam hal ini, guru hendaknya menciptakan kondisi belajar yang mendukung perkembangan kemandirian belajar para siswa (autonomous learning) sehingga mereka terdorong untuk semakin berperan aktif dalam proses pembelajaran. Karena guru yang mandiri cenderung mendukung para siswanya untuk mandiri, autonomous learning perlu diterapkan pada para calon guru bahasa Inggris sebagai langkah awal untuk mengembangkan kemandirian belajar para siswa di Indonesia.

Studi ini mengkaji inovasi program pembelajaran, yaitu the collaborative audio-journal project, yang diterapkan di kelas Listening Comprehension III, Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, Universitas Sanata Dharma. Program ini bertujuan untuk meningkatkan kemandirian belajar mahasiswa. Ada tiga permasalahan dikemukakan dalam penelitian ini. Permasalahan pertama membahas prosedur penerapan program tersebut. Permasalahan kedua memaparkan pandangan mahasiswa terhadap program tersebut. Permasalahan ketiga membahas strategi metakognitif yang digunakan oleh mahasiswa.

Peneliti menggunakan metode penelitian kualitatif. Ada dua alat yang digunakan untuk mengumpulkan data, yaitu lembar refleksi dan wawancara. Ada tiga hasil yang diperoleh. Pertama, berdasarkan pembahasan prosedurnya, program ini memang benar bertujuan untuk meningkatkan kemandirian belajar mahasiswa melalui kelompok kecil yang mendukung self-interdependence dan refleksi yang meningkatkan kesadaran belajar. Kedua, para mahasiswa mengalami kecemasan ketika pertama kali diberi tugas tetapi kecemasan itu berubah menjadi kegembiraan seiring dengan proses pengerjaannya. Ketiga, mahasiswa menggunakan strategi metakognitif. Mereka merencanakan pengerjaan tugas, seperti waktu dan kualitas, kreativitas, dan strategi. Mereka menemukan masalah, seperti fasilitas, pengaturan waktu, kemampuan bahasa, dan kemalasan. Mereka menggunakan strategi pemecahan masalah untuk mengatasinya. Mereka memantau melalui tiga cara, yaitu membaca kembali, mendengarkan lagi, dan membandingkan. Mereka mengevaluasi, baik proses maupun hasilnya.

Peneliti menyimpulkan tiga poin penting. Pertama, kemandirian belajar yang diciptakan melalui program ini adalah reactive autonomy. Kedua, perubahan pandangan mahasiswa terhadap tugas tersebut menggambarkan perkembangan kesediaan dan motivasi mereka dalam mengerjakannya. Ketiga, penggunaan strategi metakognitif menunjukan bahwa mahasiswa sungguh mengatur belajar mereka. Peneliti memberi saran kepada (1) dosen agar memberi masukan pada jurnal respon mahasiswa, (2) mahasiswa agar tetap mengatur sendiri belajar mereka, dan (3) peneliti mendatang agar mengkaji lebih dalam faktor psikologis yang berpengaruh dalam perkembangan kemandirian belajar.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I hardly imagine having accomplished my thesis entitled “Enhancing

Students’ Learning Autonomy through the Collaborative Audio-Journal Project in

Listening Comprehension III” without the blessing of my only Lord, Jesus Christ. His kind and sacred heart faithfully accompanied me in the thesis accomplishment,

both in my ups and my downs. My gratefulness is worth giving to Mother Mary, to whom I go whenever I feel burdened and frustrated. Her sincere smile touches

me very much, reminding me of the words of wisdom “Dum Spiro, Spero”.

In the last six months, I owe much to Markus Budiraharjo, my major sponsor, for giving me attention, suggestions, guidance, and motivation during the

finishing process of my thesis. Finishing this final project, I am greatly indebted to

Christina Kristiyani, my co-sponsor, who gave valuable feedbacks, support and guidance. My sincere gratitude also goes to all PBI lecturers, who have guided me to be a mature person, and the secretariat staffs (Mbak Tari and Mbak Dani), who have supported me during the last four years.

I would like to thank my family, my father, Ag. Subardi, my mother, Yuli Supriyatini, and my brother, Budi Astika, for their stories, support, love, kindness, and warmth. My deepest love and gratitude go to my girlfriend, Ayus, for love, patience, care, warmth, kindness, sharing moments, and support.

Who I am now is inevitably under the influence of persons who took part

in my past life. Hence, this thesis is worth dedicating to all of my former teachers, who had educated me for years so as to make me who I am now, and my previous formatores, especially Rm. A. Budi Wihandono, Pr. and Rm. Fx.

Sukendar, Pr., who always pray for me, especially in my hard times of the thesis accomplishment. I also intend to offer my greatest thankfulness to all my friends in “Be Still My Friends (BSMF) Community”, particularly those who join

[email protected], for sharing moments and laughs we have.

My deepest gratefulness goes to my friends of PBI’03, especially Leli, Niko, Tony, Fendi, Dudi, Wiwid, Datu, Dame, Ipad, Titin, Arum, Siwi, Nina, Yusta, Yoyok, Anas, Ayuni, Fitrianingsih, Utik, Krisna, Rere, Santi, Febri, Andri, Siwi, Lukas, Jii, Tika, Mirta, Suki, Bayu, Punto, Bagong, Upik, Neti, Ucik, Linda, Melani, Lisa, Dita, Nita, Reta, and Lintang, for friendship, discussion, and support we ever had during my four-year study. I owe a debt of

gratitude to all of my participants for spending times to give me precious data. My appreciation also goes to the following persons: Septi PBI’05 for helping me type the reflection sheet; Sisca PBI’05 for sharing moments we have; Bu Yuseva for willingness to read and give valuable feedbacks on my thesis. Lastly, I thank

persons whose names cannot be mentioned one by one, who helped me in the

finishing process of my thesis.

Priyatno Ardi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TITLE PAGE ... i

APPROVAL PAGE ... ii

PAGE OF BOARD OF EXAMINERS ... iii

PAGE OF DEDICATION ... iv

STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALITY ... v

ABSTRACT ... vi

ABSTRAK ... vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... x

LIST OF FIGURES ... xiii

LIST OF TABLES ... xiv

LIST OF APPENDICES ... xv

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study ... 1

B. Problem Formulation ... 5

C. Problem Limitation ... 5

D. Objectives of the Study ... 6

E. Benefits of the Study ... 7

F. Definition of Terms ... 7

CHAPTER II: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

A. Theoretical Description ... 10

1. Theory of Second Language (L2) Listening ... 10

a. Cognitive Processes in Listening Comprehension ... 12

b. Communicative Perspectives of Teaching L2 Listening ... 14

c. Journal as Low Stakes Writing ... 17

d. Listening Project ... 18

2. Metacognition ... 19

a. Metacognitive Knowledge ... 20

b. Metacognitive Strategy ... 23

3. Learning Autonomy in Language Learning ... 26

a. Reason for Learning Autonomy ... 26

b. Concept of Learning Autonomy ... 28

c. Language Learning Autonomy in Asia ... 33

d. Collaborative Learning ... 34

B. Theoretical Framework ... 37

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY A. Research Method ... 39

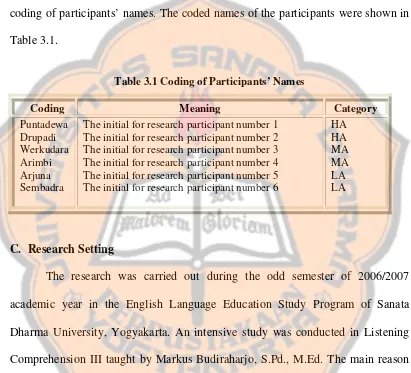

B. Research Participants ... 40

C. Research Setting ... 41

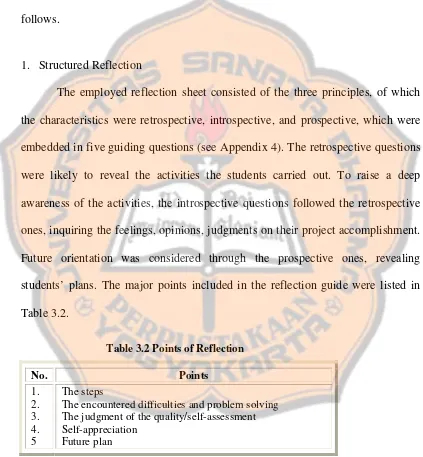

D. Research Instruments ... 42

E. Data Gathering Techniques ... 43

F. Data Analysis Techniques ... 44

G. Research Procedures ... 47

CHAPTER IV: RESEARCH FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS A. Procedures of the Collaborative Audio-Journal Project ... 48

B. Students’ Experiences ... 52

1. Students’ Perceptions ... 53

a. Students’ Initial Perceptions ... 53

b. Students’ Developmental Perceptions ... 56

2. Metacognitive Strategies ... 60

a. Planning ... 60

b. Problem Solving ... 66

c. Monitoring ... 72

d. Evaluating ... 78

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS A. Conclusions ... 84

B. Suggestions ... 86

REFERENCES ... 88

APPENDICES ... 92

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

2.1 Integrated Skill Models ... 15

2.2 Control over Cognitive Process ... 30

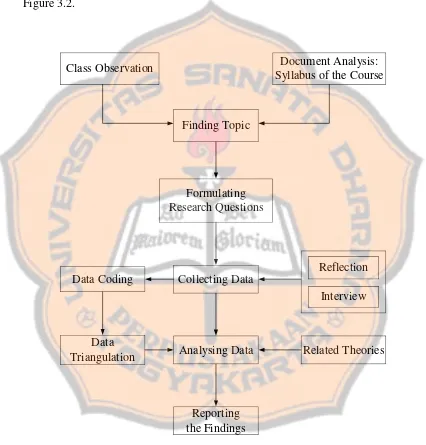

3.1 Data Triangulation of the Third Research Question ... 46

3.2 Research Procedures ... 47

LIST OF TABLES

Page

3.1 Coding of Participants’ Names ... 41

3.2 Points of Reflection ... 42

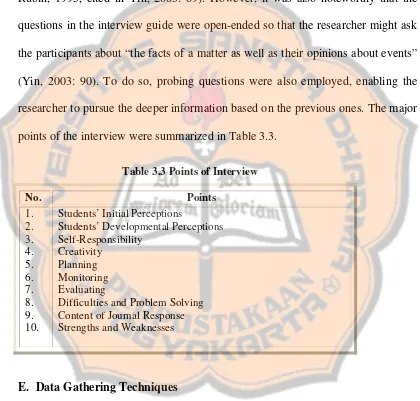

3.3 Points of Interview ... 43

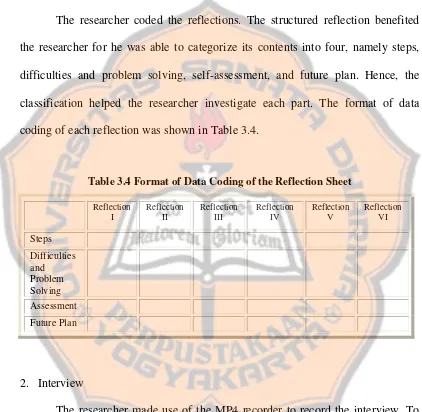

3.4 Format of Data Coding of the Reflection Sheet ... 45

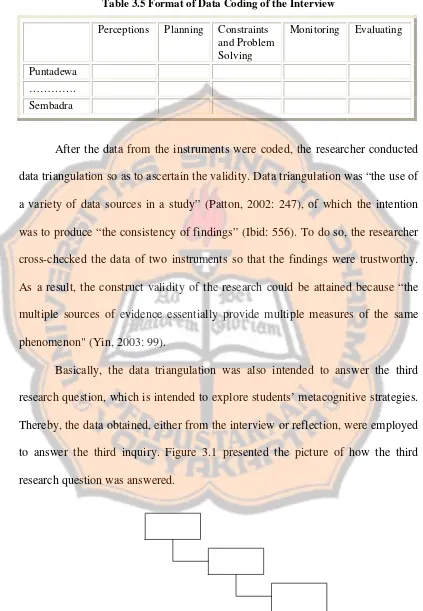

3.5 Format of Data Coding of the Interview ... 46

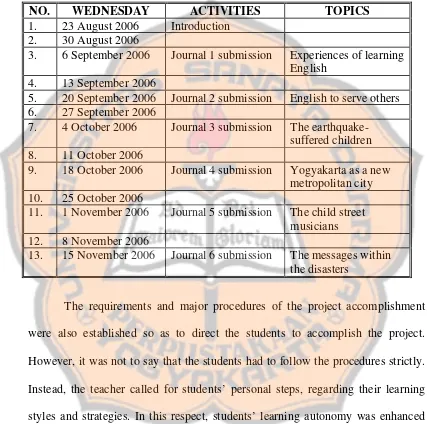

4.1 Schedule of Journal Response Submission ... 49

4.2 Procedures of Project Accomplishment ... 50

LIST OF APPENDICES

Page

Appendix 1: Listening Comprehension III Syllabus ... 92

Appendix 2: Transcripts of Teacher-Made Audio-Journals ... 95

Appendix 3: Examples of Students’ Written Journal Response ... 105

Appendix 4: Guiding Questions of Reflection ... 111

Appendix 5: Participants’ Reflection ... 112

Appendix 6: Guiding Questions for Interviewing the Participants ... 124

Appendix 7: Transcripts of Interview ... 125

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, the researcher elaborates six major underlying issues,

namely background of the study, problem limitation, problem formulation,

objectives of the study, benefits of the study, and definition of terms. Hence, the

introduction is intended to build the main rationale for conducting the research.

A. Background of the Study

Learning autonomy is indisputable to be one of formal educational goals

(Bould, 1988, cited in McClure, 2001), of which the orientation is to develop the

attitude that learning is a lifelong process (Knowles, 1968, cited in Wenden, 1987).

In this respect, the objective involves a requirement that the educational

practitioners promote students’ learning autonomy in teaching-learning processes.

Fostering learning autonomy means increasing students’ active involvement and

minimizing teacher’s intervention in learning processes. As a result, the students

increase responsibility for their own learning by decision or choice making

(Littlewood, 1996) and ultimately keep on learning after finishing formal

education (Littlewood, 1999).

The field of language teaching and learning also gives special attention to

learning autonomy as an indispensable issue having been a widespread discussion

since the Council of Europe’s Modern Languages Project (1971) (Benson, 2001).

Even though the birth of the idea is in western context, the influence spreads to all

parts of the world for it is believed to be a fruitful way to learn language. Even, it

is recently argued that students’ control over language learning becomes greater

due to the proliferation of technology. An interactive video program called A la

recontre de Philippe, for instance, offers a simulated target community in which

the students can involve in daily activities and interact with the target language

(Murray, 1999). Apparently, to promote learning autonomy also means to give the

students an opportunity to deal with the available resources.

As a response to globalization, the issue of learning autonomy is indeed

worth considering in teaching English as foreign language in Indonesia. Since

English is a global language and a lot of knowledge is conveyed through English,

possessing “a working knowledge of English” becomes a requirement for

Indonesians to take part in international communication, to improve “global

literacy” (Hart, 2002: 35), and to share values with other countries. In other words,

mastering English is an urgent need for Indonesians to be knowledgeable about the

world. Notwithstanding, it seems difficult to acquire the condition for the growth

of English knowledge in Indonesia, considering the fact that English is regarded as

no more than a compulsory subject taught in school and unfortunately most of the

students rely much on the teacher in learning English.

It is undeniable that most of the students hardly possess self-initiatives to

learn English on their own. As to East culture, the teacher is viewed as the decision

maker of learning process (cf. Littlewood, 1999). As a result, the students merely

accept and follow teacher’s policy. However, this indeed signifies a challenging

task for the teacher to provide autonomous learning settings which exercise the

greater degree of students’ learning autonomy. Consequently, the students are

that learning occurs only in classroom is altered into the notion that learning takes

place every where and every time. Hence, the role of teacher is strategic to

encourage the students to direct their own learning so as to master the working

knowledge of English.

Nonetheless, regarding the vital and strategic role of the teachers to

promote learning autonomy, Sert (2005) maintains that the teachers who do not

experience learning language autonomously will hardly foster the students to take

control of their own learning. In other words, autonomous teachers tend to have a

great deal to initiate autonomous students. Indeed, it also constitutes that

promoting learning autonomy to English teacher candidates is a first path to

develop future students’ learning autonomy in Indonesia. For this reason, it is

necessary to address the autonomous learning setting to the English teacher

candidates.

The English Language Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma

University, which prepares its students to be English teachers, seeks to contribute

autonomous English teacher candidates who will ultimately be beneficial for the

development of learning autonomy among their future students. Providing

innovations in teaching happens to be a new challenge for the lecturers to enhance

students’ learning autonomy. One of the efforts is the collaborative audio-journal

project implemented by one of lecturers in Listening Comprehension III, treated as

a biweekly home assignment during the odd semester of 2006/2007 academic year.

Based on an informal interview with the lecturer, the implementation of the

project is triggered by the fact that most of the students consider Listening

just come and sit passively waiting for the lecturer to play the recordings. In the

same way, they are not required to accomplish home assignments and/or to prepare

themselves to join the class. Those indeed suggest students’ passive role in the

teaching-learning processes for the students are not exercised to actively manage

the learning processes on their own. Students’ dependence on the lecturer is

greatly apparent instead.

Incorporating portable MP3 or MP4 players, the project facilitates the

students to accomplish the given tasks outside the classroom, expanding from

classroom boundaries. In this sense, student centeredness is practically displayed

in order that the students actively pace themselves to accomplish the project. As a

consequence, the students themselves plan, monitor, and evaluate the project

accomplishment. Thereby, it can be inferred that the project “provides a principled

and practicable route toward autonomy” (Thomas, 1991, cited in Benson, 2001:

21).

The project also seeks to integrate and improve simultaneously English

literacy skills, such as listening, writing, vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammar.

Hence, the project is to contribute the communicative endeavor of teaching

listening since the other productive skills are integrated to facilitate the

communication (Norman, Levihn, and Hedenquist, 2001). The brief explanation of

the project accomplishment is as follows. First, the students listen to the recording

and find the idea of the teacher made-audio journals. Second, the students respond

to the journals in a piece of writing. In this regard, vocabulary development,

grammar, and organized ideas are taken into account simultaneously. Third, the

journals, speaking skills and pronunciation are emphasized. Overall, the project

aids the students to view that language is a concurrently working system rather

than a collection of segregated skills.

As its name suggests, the activities of the project accomplishment give a

preference to collaborative learning which allows the students to involve in group

work in order to accomplish the task. Little (2004: 1) asserts that “self-instruction

is a matter of internalizing social interactive processes”. The students’ interaction

in completing the project enables them to negotiate meaning and finally reach

interdependent problem solving. Thus, the self-interdependence shapes

considerably the concept of learning autonomy adhered to Asian learners (cf.

Littlewood, 1999; Dardjowidjojo, 2006).

B. Problem Formulation

The questions addressed in the research are:

1. How do the procedures of the collaborative audio-journal project foster

students’ learning autonomy?

2. How do the students perceive the collaborative audio-journal project?

3. How do the students employ the metacognitive strategies in the project

accomplishment?

C. Problem Limitation

The research is limited to the collaborative audio-journal project which is

implemented in Listening Comprehension III. The project is an attempt to

procedures established by the teacher, which are intended to give the students

general direction in accomplishing the project. In this case, the procedures, to a

certain extent, also picture the learning autonomy which is intended to enhance. As

the students deal with the project, they build perceptions toward it. The

perceptions are taken into account since they portray students’ motivation and

willingness to complete the project.

Through the presence of portable MP3 or MP4, the students are also

facilitated to manage their own paces in the project accomplishment. As a result,

during the project accomplishment, they themselves are likely to plan, monitor,

evaluate, and solve the encountered problems. Such metacognitive strategies (cf.

Chamot et al., 1999) are considered in this research for they represent students’

learning autonomy, particularly in the control over learning management (Benson,

2001).

D. Objectives of the Study

The objectives of the study are to answer three questions. The answer to

the first question covers the discussion about the procedures of the collaborative

audio-journal project. It finally attempts to decide the kind of autonomy which is

intended to enhance through the project accomplishment. The answer to the

second and third question explores students’ experiences in accomplishing the

project. The second question explores students’ initial and developmental

perceptions. The third question depicts students’ project management through

planning, problem solving, monitoring, and evaluating strategies. The experiences

E. Benefits of the Study

The study hopefully benefits those who deal with language teaching and

learning, particularly teachers, students, and future researchers in Indonesia. First,

it provides the teachers with the knowledge of language learning autonomy and its

essential effects on language learners’ self-management in learning language. As a

result, the teachers are likely encouraged to create atmospheres which foster

students’ learning autonomy. Second, the study makes language learners more

aware that they themselves are responsible to manage their learning. As a result,

they consider that learning is self-driven so as to be well prepared in the lifelong

learning process. Third, the study benefits future researchers because it can be

used as the basis for conducting further researches on language learning autonomy.

F. Definition of Terms

This section presents the definition of terms which is intended to avoid

confusion and misconception, namely learning autonomy, autonomous learning,

collaborative audio-journal project, and Listening Comprehension III.

1. Learning Autonomy

The original and mostly cited definition of learning autonomy in language

learning appears to be Holec’s definition (1979: 3), unfolding that “learning

autonomy is the ability to take charge of one’s own learning”. To hold learning

autonomy as an observable field, Benson (2001: 47) alters the term “take charge”

into “take control” and thereby defines learning autonomy as “the capacity to take

of learning autonomy, which is identified through students’ experiences in the

process of accomplishing the project.

2. Autonomous Learning

Autonomous learning differs from learning autonomy. As learning

autonomy is defined as the capacity to take control of one’s own learning,

autonomous learning is “learning in which the students’ capacity for autonomy is

exercised and displayed” (Benson, 2001: 110). It is then characterized by

particular procedures and relationship between students and teacher, whether it is

more or less self-driven. Thereby, in this study, the collaborative audio-journal

project functions as an autonomous learning that enables the students to take the

greater control of their learning.

3. Collaborative Audio-Journal Project

The collaborative audio-journal project refers to the out-of-class activity of

Listening Comprehension III. In this respect, the students listen to the six teacher

made-audio journals, respond to those journals in the written form, and finally

record the written responses in MP3 format. Inasmuch as the project is out-of-class

activity, the students are addressed to a great opportunity to pace themselves in

accomplishing the project, such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Besides,

the project also aims to improve students’ English literacy skills in tandem and to

encourage collaborative skills among students. Hence, this study regards the

collaborative audio-journal project as an innovative and autonomous learning

4. Listening Comprehension III

Listening III is a compulsory subject taken by the students of the English

Language Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. Nurwidasa et

al. (2004: 84) convey that the main goal of Listening Comprehension III is

“students understand short and longer dialogues, and monologues of TOEFL, so

that they can reach the score of 450 and above”. Inasmuch as the study focuses

much on the out-of-class activity, Listening Comprehension III works as a general

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

This chapter is intended to review some theories related to the issue of the

study and to formulate the theoretical framework. For this reason, the researcher

divides this chapter into two major sub-headings, namely theoretical description

and theoretical framework. The theoretical description provides the theoretical

review of the issues, whereas the theoretical framework explains the thread of the

theories to formulate the orientation of the study.

A. Theoretical Description

There are three main issues raised in the study, namely theory of second

language (L2) listening, metacognition, and learning autonomy. Accordingly, the

discussion of those three issues was based on the previous literatures or researches.

1. Theory of Second Language (L2) Listening

It is incontrovertible that listening skill plays a critical role in language

acquisition and is thus worthwhile to consider in teaching language. Its function,

by most experts, is frequently juxtaposed to the input hypothesis, i.e. providing

comprehensible language inputs enriching one’s linguistic stock articulated

through the other productive skills afterward (Krashen and Terrell, 1983). Indeed,

comprehension is the central part of acquiring and learning language. Citing Færch

and Kasper (1986), Goh (2002a) argues that L1 and L2 comprehension process

shares common similarities regardless of linguistic and sociolinguistic limitation.

Furthermore, Goh (2002a) unfolds that listening is as a skill, product, and

process. As a skill, listening obviously emerges to be one of four language skills in

spite of speaking, reading, and writing. Listening can also be broken down into a

large number of sub-skills (Lynch and Mendelsohn, 2002), such as listening for

gist, drawing inferences, making prediction, and many others, which are,

according to Rhodes (1987), cited in Feyten (1991), crucial to the success of

listening comprehension. Nevertheless, those sub-skills are covert and only

identified through the observable behaviors of completing the given tasks aiming

to elicit students’ comprehension. The answers to the given questions are, by no

means, taken into consideration and thereby constitute the notion that listening is a

product, showed in “the number of correct and incorrect answers” (Goh, 2002a: 4).

To arrive at such a performance, an underlying mental process occurs within the

listeners, shaping the idea that listening as a process.

A traditional view, however, reveals that the process of listening is passive

for it is categorized as a receptive skill (Helgensen, 2003), meaning that listeners

merely receive the information effortlessly. This view is extremely influenced by

behaviorist theory highlighting that learners are passive processor (Hutchinson and

Waters, 1987). Currently, the belief shifts into the concept that listening is an

active mental process of meaning making, depicted in the process of interpreting

the message. Citing Buck (1995), Helgensen (2003) argues that the meaning does

not remain in what to listen to but is built through the interaction between the

listeners and the text itself. In this respect, listening is believed as an interpretive

process (Lynch and Mendelsohn, 2002), taking into account the constructive

a. Cognitive Processes in Listening Comprehension

Carrier (1999) argues that most L2 listening researches focus on cognitive

factors due to the fact that cognitive factors apparently give much contribution to

the success of listening comprehension. Besides, understanding the cognitive

process may account for how “linguistic information is processed by a number of

cognitive systems: attention, perception, and memory” (Goh, 2002a: 4) and it

hence pictures that listeners do process the information actively. For this reason,

this section views the cognitive perspective of listening comprehension process.

The mostly agreed and discussed cognitive process deals with the dual

perspectives of listening, namely bottom-up and top-down processes.

1) Bottom-Up Processing

Bottom-up processing requires the listeners to process the information,

started from smaller component parts of language, i.e. sounds, into larger parts,

such as words, phrases, clauses, and sentences (Morley, 2001) prior to

understanding the aural input (Goh, 2002a). Directing attention to specific

linguistic inputs, the L2 listeners take advantage of this process as it helps them

identify the target language. Regarding this view as a passive rather than active

process, quoting Anderson and Lynch (1988), Lynch and Mendelsohn (2002: 197)

consider the listeners as “tape recorder” for successful comprehension is viewed as

the ability to memorize and recall word-for-word the speaker says. Though the

level of bottom-up processing is thought to be lower than that of top-down

processing (Peterson, 2001), Goh (2002a: 5) tends to accept that this process

because the listeners, particularly those of L2, decode linguistic inputs through

active mental process.

2) Top-Down Processing

As the initial process of bottom-up is linguistic inputs forming meaningful

units, the principle of top-down processing conversely entails the listeners to

activate their schema which pertains to the given information prior to reaching

comprehension. The schema refers to world knowledge a person has in mind.

There are two kinds of schema, viz. content and rhetorical or textual schema. The

content schema deals with the content of the knowledge resulted from life

experiences, while the rhetorical schema is the knowledge of the particular

structure or organization (Lynch and Mendelsohn, 2002; Long, 1989). Thereby,

making sense of what is listened to, the listeners trigger their existing knowledge

to infer and predict the new information to create the meaning in mind (Morley,

2001). In this respect, listener is “an active model builder” for it focuses on the

interpretation of the given information rather than the memorization of the stream

of speech (Anderson and Lynch, 1988, cited in Lynch and Mendelsohn, 2002:

197).

It is noteworthy that either bottom up or top-down processing is taken into

account in listening and even frequently applied simultaneously by the listeners, of

which the process is called an interactive processing (Peterson, 2001).

Nonetheless, the extent to which one model is used depends on the purpose for

listening (Vandergrift, 2004). Focusing on content-oriented listening, for example,

situational experiences rather than the linguistic inputs for the sake of

comprehension.

b. Communicative Perspectives of Teaching L2 Listening

The emphasis of teaching language gradually shifts from the grammar

primarily emphasized instruction to the communication focused instruction. Up to

the late 1960s, the audio-lingual method had dominated language teaching.

Influenced heavily by behavioral psychology and structural linguistics, it

emphasized mimicry and memorization on learning to reach the habit formation of

structural pattern. In teaching listening, the learners were exposed to drilling and

repeating what speaker said; hence, it is in accord to Anderson and Lynch’s

analogy (1988), as cited in Lynch and Mendelson (2002) that the listener is as a

tape recorder. Comprehension was, thereby, accounted if the listeners were able to

memorize whatever the speaker said. In 1970s, the communicative language

teaching movement (CLT) began influencing language teaching, hence

enlightening the communicative nature of language and replacing the audio-lingual

method. Considered as a major source of comprehensible input (Helgesen, 2003),

listening for meaning appeared to be the primary focus of teaching listening (Rost,

2002). Finally, since 1990, the principles of communicative approach have been

adopted and been a new trend in language teaching.

The main idea of communicative language teaching is to encourage the

students to use language for communicative purposes – knowing about and how to

use the target language. Influencing someone with purposes is recognized as the

communication is identified through the change of behaviors or linguistic

responses. In listening, the linguistic responses are mediated by the productive

skills. Therefore, to facilitate the communicative linguistic outcomes, the teaching

of listening skills is integrated with the other productive skills. Figure 2.1 depicts

two different integrated skill models offered by Norman et al. (2001), of which the

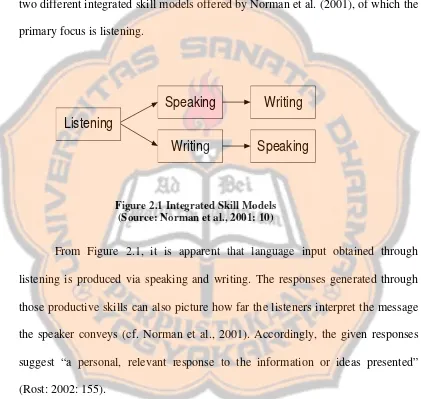

primary focus is listening.

Listening

Speaking

Writing

Writing

Speaking

Figure 2.1 Integrated Skill Models (Source: Norman et al., 2001: 10)

From Figure 2.1, it is apparent that language input obtained through

listening is produced via speaking and writing. The responses generated through

those productive skills can also picture how far the listeners interpret the message

the speaker conveys (cf. Norman et al., 2001). Accordingly, the given responses

suggest “a personal, relevant response to the information or ideas presented”

(Rost: 2002: 155).

It is also worth noting that the communicative approach not only alters the

grammar focused instruction but also entails other significant consequences in

language learning and teaching. Quoting Jacobs and Farrell (2003), Richards

(2005: 27-28), unveils eight changes in today’s language teaching pedagogy

1) It is important to provide a greater chance for the learners to manage their own

learning, either content or process, thus breeding learner autonomy, a topic

discussed in greater depth in section 3 of this chapter.

2) Inasmuch as learning is social endeavor, providing collaborative learning in

classroom, hence requiring the students to accomplish the given task in

interaction with others, represents an effort to evoke the social nature of

learning and significantly supports learning autonomy due to students’

interdependence in negotiating the meaning.

3) The curricular integration seeks to link English tasks to other subjects so that

project work calls for “exploring issues outside of the language classroom”.

4) The content becomes the heart of language learning so as to elicit meaningful

language.

5) Appreciating students’ differences, i.e. by noticing students’ strengths and

weaknesses, needs thinking in the communicative language teaching.

Consequently, developing students’ use and awareness of their own learning

strategies becomes the emphasis of instruction.

6) Valuing higher-order thinking skills, known as critical and creative thinking,

serves the students to use the language beyond the language classroom,

facilitating the students to become ready in a life-long learning process

accordingly.

7) Learning assessment conducted using the multiple-choice items or other items

merely testing the lower-order skills does not work. Yet, the multiple forms to

attain the comprehensive picture of the students, such as portfolio, interviews,

8) The role of the teacher also changes from the only knowledge source into the

facilitator.

c. Journal as Low-Stakes Writing

The previous section reveals that communicative teaching of listening

needs the other productive skills so as to identify whether the listeners understand

the intended messages. Writing is a medium to picture the listeners’

comprehension. In this case, the listeners may respond to the speaker in the form

of journal writing. Although the journal response is often applied in teaching

reading, well known as reader response, it is also possible to employ the journal

response in teaching listening. The students are then assigned to write their

response to what they listen to. The written journal may contain students’

generated ideas, students’ analytical thinking, students’ feeling, and the like.

There are two kinds of writing, namely high-stakes writing and low-stakes

writing (Vacca and Vacca, 2000). High-stakes writing is intended to produce a

finished product, whereas low-stakes writing appears to be an unfinished product.

Citing Elbow (1997), Vacca and Vacca (2000: 218) contend that high-stakes

writing demands the students to produce excellent pieces of writing which are

judged from “soundness of content and clarity of presentation”, e.g. an academic

paper. Although it is unfinished, the low-stakes writing also represents students’

thought but “does not merit the careful scrutiny which a finished piece of writing

deserves” (Gere, 1985, cited in Vacca and Vacca, 2000: 219). Therefore, the

students are free to write and elaborate their ideas without being worried by the

Journal response is considered to be low-stakes writing (Vacca and Vacca,

2000). The journal writing facilitates the students to respond and “interact

personally with ideas and information without pressure of producing polished,

finished products” (Elbow, 1997, cited in Vacca and Vacca, 2000: 218). Therefore,

it allows the students to use their personal language so as to make sense of the

ideas or information they encounter in listening passage. All at once, background

knowledge is activated so that the information the students maintain in mind

approaches the new information. Overall, journals can be used to monitor students’

comprehension, interpret or analyze the content, and even help the students

identify the encountered problems.

d. Listening Project

Listening project is “the extended activity that involves listening and other

skills in an integral way” in which the students may work, either individually or

collaboratively, in classroom meeting (or) as well as in outside classroom (Rost,

2002: 162). Furthermore, he suggests the aim of the project involve various kinds

of listening. Interviewing the native speaker of English, for example, leads the

students to create a bidirectional mode of listening (cf. Morley, 2001). Thereby,

the listening project, as argued by White (1998), cited in Rost (2002), encourages

the students to apply the obtained skills to the real world communication.

Nunan (2004) insists that the project-based instruction be considered as

“maxi-tasks” (his quotation) for it requires systematic and integrated tasks ending

up in the final project. The project itself seeks to find the proper model so as to

aspects. For this reason, project-based instruction has been developed through

three generations (Ribe and Vidal, 1993, cited in Nunan, 2004). Considering the

importance of communication, the nature of the first project model seeks to

develop communicative ability among the students. Yet, it is widely argued that

the competence underlies the communicative performances. For this reason, the

second generation project is to increase not only the communicative performance

but also cognitive aspects of the students, such as learning strategy, thinking skills,

and so on. As the aim of education is to help the students accomplish a

fully-developed person, in spite of enhancing communicative and cognitive growth, the

third generation project promotes personality development through the foreign or

second language education. Therefore, fostering the students to build attitudinal

changes, learner awareness, learner autonomy, motivation, and the like constitutes

the ultimate aim of this project.

2. Metacognition

Quoting Flavell (1970), Sinclair (1999: 102) depicts metacognition as

self-knowledge and awareness the learners hold about the learning process. Recent

literatures consider metacognition as an umbrella concept comprising both

metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive strategy (see Goh and Taib, 2006;

Wenden, 1999). Moreover, Wenden (1999: 436) simply elaborates the definition

of metacognitive knowledge as “information learners acquire about their learning”

and of metacognitive strategy as “general skills through which learners manage,

direct, regulate, and guide their learning”. Those components seem separate,

a. Metacognitive Knowledge

Metacognitive knowledge represents the learners’ knowledge about their

learning processes (Wenden, 1999), including the beliefs remaining in the learners

“about the ways different factors act and interact to affect the course and outcomes

of learning” (Goh, 2002b: 37). A subdivision of metacognitive knowledge (see

Ellis, 1999), learners’ beliefs strongly support them in building metacognitive

knowledge but in most literatures both terms are interchangeably used (Wenden,

1999). Additionally, a long debate about whether this knowledge is only acquired

by adult learners or children do have it in their very young age also occurs in the

discussion (cf. Ellis, 1999).

As a matter of fact, metacognitive knowledge increases steadily as just the

children grow up. The very young learners, to a certain extent, embrace the

metacognitive ability (Ellis, 1999) but rarely are they aware of it so that the ability

is not consciously applied yet (Goh and Taib, 2006). As the learners involve in

social activities, they encounter a lot of experiences, changing and enriching their

metacognitive knowledge hence, but it is still subconsciously acquired.

Meanwhile, when the learners reach cognitive maturity, as Wenden (1999) states,

the students manage to bring the metacognitive knowledge into the awareness

level through the ability to reflect on their learning process. In this sense, the

metacognitive knowledge is raised into metacognitive awareness so that the

learners can communicate it to others.

Based on the work of Flavell (1976), Goh and Taib (2006) divide

metacognitive knowledge into three aspects, namely person knowledge, task

information about oneself as a learner, taking into account factors that influence

learning, such as attitudes, beliefs, expectations, motivation, needs, learning style,

and preferred learning environment (Ellis, 1999). In this regard, the person

knowledge is determined by the ability to look at self aspects akin to learning

(Bransford et al., 2000), thus facilitating the students to be aware of their learning

strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, a part of person knowledge, students’ beliefs

or perceptions strongly influence the outcomes of learning (cf. Wenden, 1987).

Most correlation studies on the learners’ belief, as stated by Victori and Lockhart

(1995), find that successful learners bear positive self-beliefs about learning

processes. As a result, they develop learning strategies to work against their

weaknesses. In contrast, maintaining negative beliefs, poor learners tend to show

poor cognitive performances, classroom anxiety, and a negative attitude toward

autonomy.

As the task is at hand, being knowledgeable about the task, i.e. knowing the

purposes, the demands, and the procedures to carry out them, becomes an

important requirement to bear in mind in order to perform the given tasks

successfully. This understanding about the nature of the given task, thereby,

conveys the notion of task knowledge. However, citing Wenden (1993), Victori

and Lockhart (1995) assert that the aspect of task knowledge is often neglected in

learner training. Indeed, the understanding of the task is crucial to point to the

chosen strategies so as to carry out the learning process.

Regarding their belief and the nature of the given task, the students are

expected to think of strategies suiting them best and effective to be applied in their

(Cohen, 1998, cited in Benson, 2001) which effectively contributes to “the

development of the language system the learner constructs and affects learning

directly” (Rubin, 1987: 23) exists to be the idea of the strategic knowledge. This

knowledge constitutes what kinds of strategies are best for them to accomplish the

tasks. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the learners employing more learning

strategies are considered as the more successful learners (Peterson, 2001).

Reviewing O’Malley and Chamot (1995), Cotterall and Reinders (2004)

propose three major types of strategy, namely cognitive, socio-affective, and

metacognitive. Cognitive strategies deal straightly with the target language, such

as identifying, remembering, storing or retrieving words, sounds or other aspects

of target language. The cognitive strategy is divided into four minor strategies,

namely rehearsal, elaboration, approximation, and paraphrase. The rehearsal

strategy works when the learners are “doing” (speaking, listening, writing, etc)

repeatedly with target language. Linking new information and what is already

known in mind (see also Chamot, 1987) constitutes the idea of elaboration

strategy. For example, hearing the word “dictionary”, the learners probably have

the word for a book in mind. As to the next two minor cognitive strategies,

Cotterall and Reinders (2004: 3) emphasize that they point to “communication

strategies”. Approximation is employed when the learners use a more general

rather than specific word to express meaning, e.g. saying “relative” instead of

“cousin”. Not knowing the word of target language, the learners are often

circumlocutory to explain the meaning, called the paraphrase strategy hereafter.

All in all, cognitive strategy is used to control information about the target

The second category of strategy is socio-affective. As its name implies, the

heart of this strategy is to regard the interpersonal and intrapersonal aspects of the

learners. Cotterall and Reinders (2004) provide three examples of this strategy,

including cooperation, questioning for clarification, and self-talk. Basically,

cooperation strategy includes the learners to work together to negotiate the

meaning. Finding difficulties in learning, the learners often ask either their friends

or the teacher to gain further explanation, portraying the example of the

questioning for clarification strategy hence. Self-talk strategy happens when the

learners need inside rather than outside supports, which are realized through the

positive statements encouraging the learners to learn language further. Being stuck

in accomplishing the task, for example, the learners may say tacitly, “I have to do

the best”. In sum, socio-affective strategy enables the learners to manipulate their

learning related to others and self (Benson, 2001). The third strategy is

metacognitive. As long as this strategy is also the other component of

metacognition, the discussion is available in the next section.

b. Metacognitive Strategy

Metacognitive strategy is simply explained as the strategy about learning,

including planning, monitoring, problem solving, and evaluating (Chamot et al.,

1999), which enables the learners to oversee, self-direct and review the process of

learning (Wenden, 1987). The detailed discussion about such kinds of

1) Planning

Planning is an important step to become a self-regulated learner. Citing

O’Mallay and Chamot (1990), Benson (2001: 82) provides three aims of planning.

Firstly, it fosters the students to build the general but comprehensive picture of

“the concept or principle in an anticipated learning activity” (advance

organization). Secondly, it facilitates the students to propose strategies for

handling the upcoming tasks. Thirdly, it enables the students to generate a plan for

the parts, sequence, main ideas, or language functions to be used in handling a task

(organization planning).

2) Problem Solving

The students are to identify the task problems which hinder the successful

completion. After identifying the problems, they choose the strategies to overcome

them. In this regard, problem solving strategy is important to bear an autonomous

learner because an autonomous learner is a problem solver (Benson, 2001).

3) Monitoring

Monitoring strategy is to help the students to regulate their learning. The

students are to check, verify, or correct their comprehension or performance in

accomplishing the task (O’Mallay and Chamot, 1990, cited in Benson, 2001). In

this respect, they monitor how they are doing in learning.

4) Evaluating

Evaluating is to decide how well the students are doing in accomplishing

including the strategy use, language repertoire, or ability to perform the task at

hand (O’Mallay and Chamot, 1990, cited in Benson, 2001). As a result, they are

able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their learning.

Needless to say, metacognitive strategy provides a great contribution to the

greater level of students’ control over learning process. Furthermore, Cotterall and

Reinders (2004) offer three reasons for making use of metacognitive strategy in

learning language. Firstly, the learners manage to build a sense of control and a

focus on particular thing at a time through planning. Secondly, as long as its

characteristic is goal setting, the goal fosters the learners to decide the supporting

tasks and strategies effective to attain it. Thirdly, employing general metacognitive

strategies, such as planning, monitoring, problem solving, and

self-evaluation, considerably promotes learners’ autonomy in learning language.

As stated previously, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive strategy

are complementary. Being aware of the metacognitive knowledge, the students are

able to see themselves as learners, to identify the requirements of the tasks, and to

think of the strategy they will use. The awareness is then manifested in the

metacognitive strategy which comprises planning, problem solving, monitoring,

and evaluating. In this respect, the metacognitive knowledge plays as a starting

point for employing the metacognitive strategy (Benson, 2001). On the other hand,

the employed metacognitive strategy enables the students to develop their further

metacognitive knowledge (Ellis, 1999) for the experiences the students find while

applying metacognitive strategy shape the knowledge about themselves as

3. Learning Autonomy in Language Learning

In the field of language learning and teaching, learning autonomy is a

relatively new pedagogy that must be precisely considered in practical ways.

Although other concepts which are derived from different theoretical framework,

viz. active learning, authentic learning, self-regulated learning, and independent

learning, are often closely associated with learning autonomy, all of them share a

common principle, i.e. the greater active involvement of learners in learning

(Niemi, 2002). Concisely, all of them entail the learners to manage, monitor, and

evaluate the learning, even without the direct control of the teacher.

a. Reason for Learning Autonomy

The concept of learning autonomy is under the influences of theories which

are beyond the field of language education. Benson (2001) at least provides four

theories principal to the importance of learning autonomy, such as educational

reform, adult education, the psychology of learning, and political philosophy. First,

from the perspective of educational reform, it is stated that the learners are

intrinsically good, responsible for their own deed, problem solver, critical,

reflective, and self-actualizer. Thereby, education must direct its orientation to

bring forth such kinds of human nature through the promotion of learning

autonomy. Second, adult education, through the advocacy of self-directed learning,

apparently prompts the idea of learning autonomy. It is assumed that directing self

to learn in non-institutional learning means having a greater responsibility to learn

(Brockett and Hiemstra, 1991, cited in Benson, 2001). Third, the psychology of

process, the learners are able to control their own learning accordingly. Fourth, the

political philosophy contributes that personal autonomy determines self-existence

as social beings. It means that each individual is free to direct themselves without

being forced by institution or external authority.

Despite all, here is also the ground for the importance of learning

autonomy viewed from social and ideological context bringing about the challenge

to develop human quality. In the 1960s, as the beginning of modern age, the

society experienced what the so-called social progress, encountering a challenge to

improve the quality of human life rather than the well-being material (Holec, 1979;

Benson, 2001). It is thought that the quality of life can only be developed through

having sense of self-responsibility toward the life itself. Meanwhile, formal

education is believed to prepare the individual “in running the affairs of the society

in which they live” (Holec, 1979: 1). Meaning to say, education is to be a

fundamental path for enhancing self-responsibility in educational context,

particularly in language education, to improve the quality of human life.

Facing the challenge to improve self-responsibility toward life, the idea of

autonomy was articulated in language learning, firstly through the Council of

Europe’s Modern Language Project in 1971 (Benson, 2001). Most notably, the

Council of Europe’s Modern Language Project aimed to foster adults’ lifelong

learning. To do so, the pilot project was conducted in the University of Nancy,

France, through the establishment of Centre de Recherches et d’Applications en

Langues (CRAPEL) by Yves Chalon, who is well known as the father of

autonomy in language learning afterward. The innovation offered by CRAPEL

Chalon died in 1972 and Henri Holec was appointed to replace his position in

CRAPEL. In the following years, the idea of learning autonomy in language

learning was shaped through Holec’s project reports (1979) to the Council of

Europe. Consequently, he is known as a key figure of language learning autonomy,

whose great work is often cited by the following advocates of learning autonomy.

b. Concept of Learning Autonomy

As previously mentioned, Holec is the first person advocating the notion of

learning autonomy in language learning. In his report to the Council of Europe,

Holec (1979: 3) defines learning autonomy as “capability to take charge of one’s

learning”. Moreover, he clarifies five requirements, or in Dardjowidjojo’s words

(2006) as doctrines, of what the students have to take to be fully autonomous

learners. First, the learners have to be able to determine the objectives of learning,

which function as a direction toward their learning. Second, to achieve the goal,

they must decide the suitable materials and monitor the progress of their learning.

Third, after the goal and material are determined, they think about methods or

techniques supporting them to attain the goal. Fourth, self-monitoring is crucial for

it enables them to check, verify, or correct while performing the language task

(O’Malley and Chamot, 1990, cited in Benson, 2001) so as to judge whether their

learning is successful and to decide which parts must be changed and which must

be continued. Fifth, employing self-evaluation entails the students to evaluate

themselves on “how much they have accomplished” (Dardjowidjojo, 2006: 5).

Based on Holec’s initial definition, most advocates of learning autonomy

language learning. Putting the emphasis on the importance of learning

management, Benson (2001: 47) defines learning autonomy as “the capacity to

control one’s own learning”. In his viewpoint, the idea of controlling over learning

is more observable than that of taking charge. Hence, to hold learning autonomy as

an observable field, the term “take charge” is changed into “control”. Moreover, he

elaborates the levels of control the students employ consisting of three

interdependent aspects, namely control over learning management, control over

cognitive processes, and control over learning content.

1) Control over Learning Management

The control over learning management points to the controlled behaviors to

handle the planning, organization, and evaluation of students’ learning. In this

regard, the behaviors are closely related to the metacognitive strategies, as

discussed in section 2. The other strategies, such as cognitive and socio-affective,

are also important in managing learning for they are consciously selected and used

by the students. Benson (2001: 80) states that “the conscious use of learning

strategies implies the control over learning management”. It is also undeniable that

the management of learning is affected by cognitive operations. The next

subsection discusses the cognitive processes which influence the control of

learning management.

2) Control over Cognitive Process

The control of cognitive processes is concerned with the psychological

assumed that the controlled cognitive processes constitute the controlled

behaviors, be either the process or the content of learning (Little, 1991, cited in

Benson, 2001). In this viewpoint, the control of cognitive processes contributes an

essential role in enhancing autonomy in language learning hence. Benson (2001),

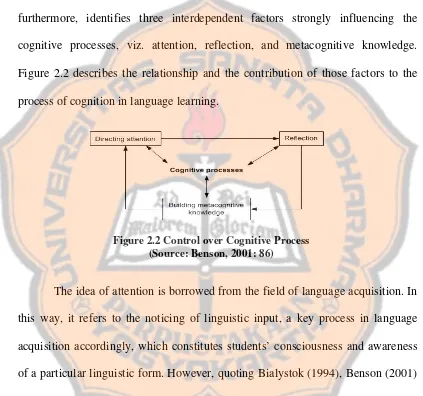

furthermore, identifies three interdependent factors strongly influencing the

cognitive processes, viz. attention, reflection, and metacognitive knowledge.

Figure 2.2 describes the relationship and the contribution of those factors to the

process of cognition in language learning.

Figure 2.2 Control over Cognitive Process (Source: Benson, 2001: 86)

The idea of attention is borrowed from the field of language acquisition. In

this way, it refers to the noticing of linguistic input, a key process in language

acquisition accordingly, which constitutes students’ consciousness and awareness

of a particular linguistic form. However, quoting Bialystok (1994), Benson (2001)

contends that the students not only give much attention to the linguistic input but

also direct themselves to construct the mental representation or the meaning of the

input. Though the idea of attention offered by Bialystok seemingly considers the

mere receptive aspect of language learning, in communicative endeavor, it is not

only limited to how the students receive the linguistic inputs but is also expanded

Discussing attention toward language input calls attention to talking about

the process on how the students attain the linguistic input. The picture of this

process is elicited via students’ reflection. Little (1997), cited in Benson (2001),

asserts that reflection is indispensable to enhance learning autonomy. Benson

(2001: 93), furthermore, asserts that reflection and autonomy are interconnected in

terms of “the cognitive and behavioral processes by which individuals take control

of the stream of experience they are subject to”. Critical reflection, as stated by

Holec (1980), cited in Wenden (1987), fosters the students to dig up the

psychological attitudes toward learning to bring about the change of their learning

behaviors. Thinking retrospectively, introspectively, and prospectively, the

students judge whether their learning experiences run well as expected.

Consequently, they are able to change their learning behavior. Thus, reflection

plays as a basis for control over learning management (Benson, 2001).

The reflected learning facilitates the students to look at themselves and

finally find the strengths and weaknesses of their learning. Consequently,

reflection raises students’ learning awareness. Furthermore, the students also bear

their metacognitive knowledge about their learning, consisting of person

knowledge, task knowledge, and strategic knowledge (see section 2,

metacognition). The metacognitive knowledge is used in their upcoming learning

management in terms of planning, problem solving, monitoring and evaluating.

3. Control over Learning Content

The third aspect of learning autonomy is control over learning content.

discussed previously, but failing to find the material to be learned does not

guarantee learning to take place. Controlling the learning content also conveys the

challenge for the students to decide what they want to learn in order to reach the

goal of their learning (Benson, 2001). As to the control over learning content,

Littlewood (1999) proposes two kinds of learning autonomy, namely proactive

autonomy and reactive autonomy.

Proactive autonomy is somewhat idealistic in the effort of promoting

autonomy in language learning. It indeed suggests that the learners regulate both

the direction and the activity of learning. Given this respect, the learners are as

“the locus of causality towards their learning” (Littlewood, 1999: 74). Proactive

autonomy is regarded to be in accordance with the clarification of ideal autonomy

articulated by Holec (1979) that the learners are able to determine the objective,

select technique and methods, and evaluate what is learned in order to take charge

of their learning. Thus, the clarification appears to be the main key for proactive

autonomy. In short, the ideal form of autonomy lies in the total involvement of the

students in their learning.

Reactive autonomy, on the other hand, requires the students to regulate the

activities when the direction is set by external authority (Littlewood, 1999).

However, it also functions as an initial step to achieve the ideal learning autonomy

for autonomy, as asserted by Gardner (2000), is a continuum process. Meaning to

say, the reactive autonomy seeds the proactive autonomy. In this kind of

autonomy, the teacher provides the students with stimulus, through establishing

the goal, procedures, and the materials. Yet, once the stimulus is determined, the

achieve the determined goal. This level of autonomy is pertinent to Asian students

who value the authority and interdependence of learning.

c. Language Learning Autonomy in Asia

Since the notion of learning autonomy is born in western context, the

principles are based on western culture in which self-independence is strongly

valued. It can be clearly seen in the definition of autonomy proposed by Holec

(1979). In his clarification, learning autonomy appraises individual independence

of learning, without the presence of the teacher or other capable persons. Even, in

the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of learning autonomy was addressed to the

concept of individualization, entailing that the students worked in isolation

(Benson, 2001). Yet, the concept is still understandable since it emerged in

individualistic culture. The individualist orientation believes that individual is

unique and encourages the students to “express themselves, make personal

choices, and strive for self-actualization” (Littlewood, 1999: 79). In this manner,

the belief entails the students as the locus of causality toward their learning,

categorized as proactive autonomy accordingly.

However, instead of being limited to the west, learning autonomy is

universal in nature. The concept of learning autonomy is accepted differently by

different cultures (Sinclair, 2000, cited in Dardjowidjojo, 2006) because the

culture, including beliefs underlying it, directs people to act. Littlewood (1999)

argues that Asian students possess learning autonomy but certainly the criteria are

different from those of the west context. It is widely known that east culture is