Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 20:04

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

INDONESIA'S NEW FISHERIES LAW: WILL IT

ENCOURAGE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OR

EXACERBATE OVER-EXPLOITATION?

Jason Patlis

To cite this article: Jason Patlis (2007) INDONESIA'S NEW FISHERIES LAW: WILL IT ENCOURAGE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OR EXACERBATE OVER-EXPLOITATION?, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 43:2, 201-226, DOI: 10.1080/00074910701408065

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910701408065

Published online: 10 Apr 2008.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 198

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/07/020201-25 © 2007 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910701408065

INDONESIA’S NEW FISHERIES LAW:

WILL IT ENCOURAGE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT

OR EXACERBATE OVER-EXPLOITATION?

Jason Patlis*

World Wildlife Fund, Washington DC

Indonesia is at a vital juncture in the direction of its fi sheries management. There is

ample evidence that fi sheries resources throughout Indonesia continue to decline

and that over-fi shing not only persists but is a growing problem. Without

govern-ment intervention, fi sheries, like other natural resources, are subject to open access

and therefore over-exploitation. Confronted with the drive to increase fi sheries

pro-duction to benefi t the economy, spur business development, provide an essential

food source and maintain local livelihoods, the government must at the same time seek to ensure that this resource is not depleted. The enactment of a new statute governing fi sheries affords an opportunity to balance these competing goals and

address some serious problems in fi sheries management and enforcement. This

paper analyses Law 31/2004 on Fisheries and concludes that, given early indica-tions on implementation, the government should more aggressively improve the regulatory and enforcement mechanisms needed to achieve sustainable fi sheries

management.

Although Indonesia is the world’s biggest archipelagic country, government agen-cies have largely ignored its fi sheries, giving more attention to the nation’s wealth

of terrestrial natural resources, extracted by logging, mining and drilling. Despite the lack of government attention until recently (or perhaps because of it), fi sheries

have not been ignored by big businesses and local communities, but have been heavily exploited without signifi cant oversight or monitoring, and consequently

with little data collection. Indeed, like other natural resources, fi sheries are often

the victim of open access in the absence of some form of government interven-tion, and this leads to likely over-exploitation and ultimate depletion. Scholars raised the spectre of over-exploitation as early as the 1960s (Yowono 1998). With growing recognition of the importance of fi sheries and the maritime sector, and

of the need for greater oversight of it, the government created a new Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF, Departemen Kelautan dan Perikanan) and a new national maritime board (Dewan Maritim Indonesia, DMI) in 1999. And after a 19-year wait, Law 9/1985 on Fisheries was fi nally replaced in 2004, with

the enactment of Law 31/2004 on Fisheries. A host of new implementing regula-tions is currently at various stages of administrative review.

* The views contained in this paper are those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Wildlife Fund.

cBIEAug07.indb 201

cBIEAug07.indb 201 27/6/07 5:33:42 PM27/6/07 5:33:42 PM

How these regulations are drafted, and how the new law is implemented and enforced, will determine the future direction of Indonesia’s fi sheries, and will

depend on the government’s outlook. As noted by Brown, Bengen and Knight (2005), policy makers are split into two camps: those who believe that Indonesia’s

fi sheries are under-developed, with considerable potential for further growth,

and with opportunities for signifi cant investment to improve infrastructure and

increase effort; and those who believe that they are already over-exploited, with under-reported data belying depletion, and with an immediate need to curtail

fi shing effort and focus on conservation of major marine areas.1 Mous et al. (2005)

also recognise the competing pressures on Indonesian fi sheries: while there is a

growing body of evidence that they are ‘fully exploited or over-exploited’, there is still increasing pressure to ‘exploit ”untapped resources”’.

The new Law 31/2004 refl ects these contrasting—and perhaps, but not

neces-sarily, irreconcilable—views. On the one hand, it offers a great deal of verbiage and over-arching direction in support of fi sheries conservation and sustainable

devel-opment; on the other, it establishes a number of programs to increase and improve

fi shing effort. Which way implementation of the law ultimately tilts will depend

on the regulations now in draft. The directions of the law are broad enough to allow implementing regulations to favour greater conservation, increased exploi-tation, or both. As individual aspects of the law will each be elaborated through individual regulations, and implemented by different divisions within the MMAF, it is highly possible—and indeed likely—that the contrary directions implicit in the law will be carried forward into the regulations.

A concerted effort is also being made to deal with enforcement issues: the min-istry has adopted a number of initiatives to establish community-based enforce-ment approaches for near-shore fi sheries, and to improve patrolling of offshore fi sheries, targeting in particular illegal foreign fi shing in Indonesian waters.

How-ever, historically weak enforcement mechanisms and a fragmented institutional structure for dealing with marine issues may hamper these efforts.

Taking all this into account, some degree of optimism might be allowed—the framework is in place to improve fi sheries management signifi cantly—but given

past experience, current drafts of the regulations, and continuing problems in enforcement, a pessimistic outlook is more justifi ed. Indonesia is likely to follow

the example of fi sheries in many parts of the globe: continued over-fi shing, a sharp

collapse in fi sh stocks, and then a patchwork set of measures to recover the fi shery.

THE VALUE OF INDONESIA’S FISHERIES

Fisheries account for approximately 2.2% of Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP). The sector is a major employer, providing roughly 3 million direct full-time and part-full-time jobs in 2002 according to Brown, Bengen and Knight (2005),

1 Falling into the fi rst camp, the Minister of Marine Affairs indicated earlier this year

(Ja-karta Post, 12/3/2007) that the gap between maximum sustainable yield (MSY) and actual catch represented an opportunity to increase fi shing effort (to boost the economic

being of coastal communities and fi shers and improve nutrition through increased fi sh

consumption), rather than evidence of possible over-fi shing. He specifi cally cited annual

catch levels of 3.8–4.8 million tons compared with an MSY of 6.4 million tons per year.

cBIEAug07.indb 202

cBIEAug07.indb 202 27/6/07 5:33:42 PM27/6/07 5:33:42 PM

while JICA (2005) estimates a slightly lower number of fi shers—2.57 million in

2002—with a 2.2% growth rate since 1999. At the other end of the scale, Dutton (2005) cites Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) data indicating 6.7 million

fi shers (both fresh-water and marine). Tax receipts from fi sheries are very small—

much smaller proportionally than in forestry and other natural resource sectors. Brown, Bengen and Knight (2005) recommend a greater effort on the part of the government to collect taxes and other revenues currently lost as a result of the

dif-fi culties inherent in monitoring fi sh landings throughout the country.

Apart from their economic signifi cance, fi sheries play a strong role in the

iden-tities and traditions of many cultures across the archipelago. Traditional fi shing

techniques and practices are still employed in many areas (Titahelu 2005). The western marine waters of Indonesia are relatively shallow, lying above the Sunda shelf surrounding Java, Sumatra and Kalimantan, while the eastern waters are quite deep (except for the Arafura Sea separating western Papua and Australia). The western waters are rich in near-shore, smaller fi sheries, while the eastern waters

serve as migratory corridors for many large pelagic (open ocean) species. Small-scale fi sheries, using gear such as lines, traps, beach seines, lift nets, pole and line,

trolling gear and mini-seines, account for almost 95% of the overall fi shing effort

in the country (FAO 2000; Dutton 2005).2 Vessels using hooks and lines account for roughly 35% of the catch; gill nets for 31.4%; seines and purse seines for 7.7% and 1.6%, respectively; traps for 8.4%; and lift nets for 6.5% (JICA 2005).

Indonesia’s fi shing fl eet approximates 460,000 vessels. According to JICA (2005),

non-powered boats that go out on daily excursions comprise roughly half of the

fl eet, although the number is steadily decreasing as more fi shers acquire small

outboard and inboard motors for their boats: in 1999, there were 241,517 non-powered boats (53.0%) and by 2002 this fi gure had dropped to 219,079 (47.6%).

Compare this with the increase in outboard motors, from 124,043 boats in 1999 to 130,185 in 2002. The increase in inboard motors on vessels smaller than fi ve gross

tons (GT) is even more dramatic: from 57,768 in 1999 to 74,292 in 2002.

At the same time, the number of large industrial vessels has more than doubled in this period: vessels of 100–200 GT with inboard motors increased from 756 to 1,612 boats; and vessels greater than 200 GT with inboard motors rose from 211 in 1999 to 559 in 2002 (JICA 2005). Dutton (2005) and Brown, Bengen and Knight (2005) observe similar trends over the last 20 years, noting not only that the fl eet is

increasing dramatically in terms of the number of boats, but also that its composi-tion is shifting heavily to larger vessels. These trends have a signifi cant bearing

on the status of the fi sheries. The major question they pose is whether the fi sheries

are still under-developed, with room to grow, or whether they are being over-exploited, with a need for greater control over fi shing effort.

Estimates of the overall catch from Indonesia’s fi sheries vary quite widely.

Citing the 2003 issue of the central statistics agency’s Statistik Perikanan Indonesia (Indonesian Fisheries Statistics), Brown, Bengen and Knight (2005) state that total production is 5 million tons per year, of which 70% (3.5 million tons) is from marine capture fi sheries, and the rest from aquaculture and fresh water. Mous et

al. (2005)—also citing government data from 2003—report that production from marine capture fi sheries is 4.4 million tons. Yet another government report states

2 For explanation of fi sheries terms used here, see <http://www.fao.org/fi /glossary/>.

cBIEAug07.indb 203

cBIEAug07.indb 203 27/6/07 5:33:42 PM27/6/07 5:33:42 PM

that total production in 2003 was 4.7 million tons, up from 4.3 million tons in 2001 (Departemen Kelautan dan Perikanan 2004). And JICA (2005) reports that total marine capture fi sheries output increased from 3.68 million tons in 1999 to 4.07

million tons in 2002 (implying an average annual growth rate of 3.42%).

These estimates of actual yield can be compared to the estimates of maximum sustainable yield (MSY)—that is, the total catch that can be borne by fi sheries

while still maintaining long-term sustainability.3 The legal quota for the fi

sher-ies harvest is tied to this fi gure: total allowable catch (TAC) is set equal to 80%

of MSY, in accordance with the ‘precautionary principle’ (Mous et al. 2005). Like those for the actual catch, the MSY fi gures vary greatly. Mous et al. (2005) observe

that estimates of MSY range over a factor of two—from 3.7 to 7.7 million tons per year—although the most reliable estimate is probably around 5.0 million tons per year. A study by JICA (2005) argues that MSY is 6.2 million tons per year.4 On this basis the annual TAC would be just under 5 million tons.

Given these ranges of variation in both sustainable catch and actual catch, it is extremely diffi cult to gain an accurate picture of the health of Indonesia’s fi sheries. Fauzi (2003) estimates the actual catch to be closer to 8.4 million tons

per year—roughly double the offi cial estimates, considerably more than the

esti-mated MSY of 6.2 million tons, and even further in excess of the corresponding TAC. He suggests that these discrepancies can be explained by a variety of fac-tors. One is over-capacity of the fi shing industry. Another is the illegal activity for

which no offi cial data exist: Fauzi (2003) cites an estimate that 3,200 Thai fi shing

vessels are illegally harvesting more than 2 million tons per year in aggregate. Yet another factor is that actual production is under-estimated in offi cial data as a

consequence of unreported catch, bycatch, and waste (Fauzi 2003).

Data for fi sh landings are also incomplete and inaccurate. In 1997, for example,

the government published a target for total landings of 143,000 tons, and subse-quently reported landings totalling 280,000 tons, while the FAO estimated that actual landings surpassed 3.6 million tons.

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK GOVERNING INDONESIA’S FISHERIES Overview of marine fi sheries management

The common starting point for any discussion of natural resource consumption and management in Indonesia is the provision in article 33(3) of the constitution that ‘[t]he land, waters and the natural resources within [Indonesia] shall be under the powers of the State and shall be used to the greatest benefi t of the people.‘

3 The concept of MSY dates from the 1930s and, as described by Mous et al. (2005), pro-motes ‘equilibrium fi shing—catching an amount of fi sh that is equal to the amount of fi sh

that is added to the population through growth and reproduction‘. Mous et al. (2005) fur-ther explain that a fi shery can be over-exploited even if harvest levels remain below the

MSY. If fi sh stocks have been pushed too low, fi shing at the MSY does not afford stocks an

opportunity to reproduce, so catch levels will be lower than they would be at the optimal stock level.

4 Of this total, roughly 52.4% are small pelagics living in near-shore waters, 28.9% are demersal (bottom-dwelling) fi sh, also in near-shore fi sheries, and 15.8% are large pelagics

(tuna, mackerel, sharks).

cBIEAug07.indb 204

cBIEAug07.indb 204 27/6/07 5:33:43 PM27/6/07 5:33:43 PM

This provision has been interpreted and analysed by numerous scholars, many of whom have criticised its implementation in favour of large economic interests rather than ‘the people‘, or rakyat (Lynch and Harwell 2002). Whether exploitation of fi sheries in Indonesian waters serves to benefi t big business or local

communi-ties, and with what prioricommuni-ties, is one of the key questions to be decided in imple-menting the new fi sheries statute. Regardless of its interpretation, it is this article

33(3) that gives authority to the central government to regulate the development and management of the resource.

An interesting anomaly of fi sheries management is that the overall

manage-ment scheme is not at all evident in the primary statute governing the sector, which establishes only the broad directions and parameters. Rather, the manage-ment scheme must be gleaned from reading the complete set of individual regula-tions and ministerial decrees promulgated by the government.

In sum, Indonesia’s management of maritime fi sheries consists of three

pri-mary components:

• limits on fi sheries catch yields for specifi c regions throughout the nation;

• geographic restrictions within near-shore and offshore waters based on size of vessel; and

• issue of permits for individual vessels and production facilities.

The nation’s maritime area is divided into 11 fi sheries resource management

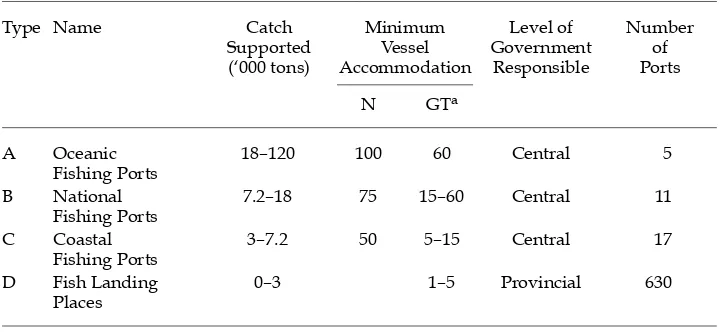

areas. For each area, the central government establishes TAC limits, based on MSY. A TAC limit is calculated for each of the four types of landing centres shown in table 1. Roughly 77% of the fi sh landing centres are in western Indonesia, and

the remaining 23% in the eastern part of the country (FAO 2000).

In terms of geographic restrictions based on vessel size, the government regu-lates vessels as follows: only vessels of 5 GT or less may fi sh within three miles of

the shoreline; vessels over 25 GT may not fi sh within four miles of the shoreline;

and vessels over 100 GT may not fi sh within fi ve miles of the shoreline.

TABLE 1 Types of Fish Landing Centres

Type Name Catch

Pursuant to Regulation 54/2002 (which superseded Regulation 15/1990), all vessels are required to be registered, certifi ed as operational, and in possession of

permits for sailing and for fi sheries business. Small-scale fi shing operations are

exempted from this requirement. Vessels of more than 30 GT are licensed by the ministry; vessels of 10 to 30 GT (and with motors of 90 horsepower or less) are licensed by the province; and vessels of under 10 GT but over 3 GT are licensed by the district. Vessels of 3 GT or less do not need a licence. The requisite paperwork is handled by a variety of offi cials, including those from the ministry, the regional fi sheries agency, the harbour-master and the local port authority. According to

Cacaud (2001), no less than 27 steps are required for the issue of fi sheries permits,

and there is an effort now, especially following the enactment of Law 31/2004, to streamline this process.

Legislation

Decentralisation has had a tremendous bearing on marine resource management, in particular providing regional delimitations of up to 12 nautical miles seaward from the shoreline for provincial management, and up to one-third of provin-cial waters for district and municipality management.5 The original decentralisa-tion law, Law 22/1999 on regional autonomy, drew a very ambiguous distincdecentralisa-tion between the jurisdictional authority of the province over its marine area (wilayah laut daerah provinsi) specifi ed in article 3, and the management authority of the

district over its marine area (kewenangan pengelolaan wilayah laut), specifi ed in

article 10. As discussed in Patlis et al. (2001), a great number of ambiguities and potential confl icts were created by the wording of Law 22/1999 and its

imple-menting regulations. Cacaud (2001) also discusses ambiguities within fi sheries

management as a result of decentralisation, raising questions about the estab-lishment of TAC limits within fi sheries regions. Many of these problems were

resolved with the enactment of Law 32/2004 on regional autonomy, which super-seded Law 22/1999 (Patlis 2005a: 235–6):

Under Law 32/2004, both provinces and districts are given broad and clear author-ity for management within their marine areas (wilayah laut) (Article 18(1)). … The new areas of authority under Law 32/2004 include exploration, exploitation, con-servation and management of marine resources; spatial planning; and enforcement of laws (Article 18(3)). Regional governments will share in the benefi ts of

manage-ment of the seabed in their marine areas (Article 18(2)). Guidelines are provided for cadastral marine boundary determination (Article 18(4) and (5)). Law 22/1999, in contrast, was silent on these issues: no provision was made for the use of the seabed, on the assumption that it would remain under central government control; furthermore, no provision was made for the designation of marine areas, cadastral determination, spatial planning and other aspects vital to determining the nature and scope of regional marine authority.

5 Districts and municipalities may declare management control over up to one-third of the provincial waters, which will generally be four nautical miles. In some cases, depending on maritime borders between provinces or between Indonesia and other countries, a prov-ince’s marine jurisdiction will be less than 12 nautical miles, in which case the district/mu-nicipal marine area will be less than four miles. There may also be circumstances in which a district or municipality does not wish to manage the one-third provincial maritime area authorised.

cBIEAug07.indb 206

cBIEAug07.indb 206 27/6/07 5:33:43 PM27/6/07 5:33:43 PM

Law 33/2004 on the fi scal balance between central and regional governments

complements Law 32/2004 and supersedes Law 25/1999. Its article 14 provides that 20% of fi sheries revenues are to go to the central government, while 80% go

to the district and municipal governments. Article 18 in turn provides that the revenues to districts and municipalities are to be split evenly across the country. Revenues are defi ned in the elucidation of article 18 to mean ‘levies imposed on

Indonesian fi shing company holders of a Fishing Permit …, a Fishing Allocation

…, and a Fish Transport Permit … for [the] opportunity granted by the Indonesian government to operate in Indonesian waters’. The revenue sharing allocation for

fi sheries is profoundly different from that for other natural resource sectors in two

ways: fi rst, for fi sheries, no share of revenues goes to the provincial governments

as in other sectors; second, for fi sheries, the revenues for regional governments

are shared equally, and not weighted in favour of the region of origin of the natu-ral resource. This was done more for practical reasons (that landings can come from throughout large marine regions, and fi sh cannot be claimed by any given

district) than for philosophical reasons (that fi sheries are a true national resource,

and therefore benefi ts accrue across the nation). Nevertheless, given the

constitu-tional provision that the resource is to be used for the benefi t of the people, and

given that fi sheries is a common resource, there is a sense of regulatory aesthetic

in the equal sharing of fi sheries revenues nationwide.

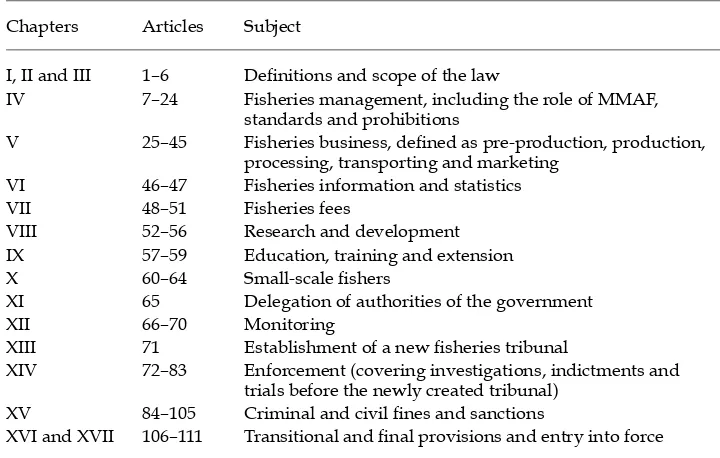

The structure of Law 31/2004 is outlined in table 2. As with most of the natural resource sectors, there are inherent tensions between the decentralisation laws and the law on fi sheries. Even though Law 32/2004 provides for provincial and

district authority within 12 miles and 4 miles (or one-third of provincial waters), respectively, Law 31/2004 defi nes the fi sheries management areas of the nation

as including all territorial waters, Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ),

TABLE 2 Outline of Law 31/2004 on Fisheries

Chapters Articles Subject

I, II and III 1–6 Defi nitions and scope of the law

IV 7–24 Fisheries management, including the role of MMAF, standards and prohibitions

V 25–45 Fisheries business, defi ned as pre-production, production,

processing, transporting and marketing VI 46–47 Fisheries information and statistics VII 48–51 Fisheries fees

VIII 52–56 Research and development IX 57–59 Education, training and extension X 60–64 Small-scale fi shers

XI 65 Delegation of authorities of the government XII 66–70 Monitoring

XIII 71 Establishment of a new fi sheries tribunal

XIV 72–83 Enforcement (covering investigations, indictments and trials before the newly created tribunal)

XV 84–105 Criminal and civil fi nes and sanctions

XVI and XVII 106–111 Transitional and fi nal provisions and entry into force

cBIEAug07.indb 207

cBIEAug07.indb 207 27/6/07 5:33:44 PM27/6/07 5:33:44 PM

and freshwater bodies as well (article 5). This gives the central government authority to regulate in the provincial and district/municipal waters of 12 and 4 miles, respectively, notwithstanding the regional authority provided under Law 34/2004. There are many other centralistic provisions throughout Law 31/2004. For example, it is the MMAF that:

• sets the total allowable catch within the fi sheries management area (article

7(1)(c));

• sets total allocations for both capture and aquaculture fi sheries (article 7(1)(a)

and (c));

• sets type, quantity and size of fi shing gear (article 7(1)(f) and (g));

• sets fi shing zones and seasons (article 7(1)(h));

• identifi es reserves and protected marine species and areas (article 7(1)(q), (s)

and (t) and 7(5));

• permits construction and import of fi shing vessels (article 35); and

• determines the plans, classifi cations, standards and accreditation of fi shing

ports (article 41).

Other provisions of the law specify that it is the central government that shall regulate all aspects of capture and aquaculture fi shing and supporting industries,

such as:

• use of waters for aquaculture (article 18);

• transporting and storage devices for aquaculture (article 19); • fi sh handling and processing (article 23);

• issuing permits (although provinces and districts/municipalities share some permitting authorities) (articles 28 and 31);

• developing fi shery information and statistical data systems, networks and

centres (article 46);

• regulating fi sheries research and development (article 52); and

• implementing education, training and extension programs (articles 57, 60 and 63).

Indeed, the law leaves very little explicitly in the hands of regional govern-ments. Only one article (article 65) broaches the subject of delegation of authori-ties from the central government to regional governments—and all it says is that the delegation of fi sheries functions shall be done through subsequent

govern-ment rule-making. So Law 31/2004 is still largely centralistic in nature, with an entirely unclear role for provinces and districts.6

Law 31/2004 also poses great uncertainties—and inherent contradictions—as to the future direction of fi sheries management. On the surface, the over- arching

mandate within the law is provided in article 6(1), which states that fi sheries

man-agement is to be ‘conducted to achieve optimum and sustainable benefi ts, and to

ensure sustainability of fi sheries‘. However, other provisions go in either of two

directions. On the one hand, many provisions mandate conservation of fi sheries

6 Patlis et al. (2001) and Patlis (2005a) discuss the broader confl icts between the

decen-tralisation laws and the statutes governing individual sectors such as fi sheries and forestry.

Even though the latter have been enacted after the decentralisation law, they nevertheless remain very centralistic in tone and text.

cBIEAug07.indb 208

cBIEAug07.indb 208 27/6/07 5:33:44 PM27/6/07 5:33:44 PM

(article 3(i)), fi sheries habitat, and protected marine species (article 7(5)), and call

for strict prohibitions against certain activities that would damage these resources (e.g. articles 8, 9, 12 and 16). On the other, many provisions call for expansion of fi shing effort (article 3(c)), increases in supply and consumption (article 3(d)),

higher revenues from fi sheries (article 3(b)), general promotion of exploitation

(article 3(f) and (g)), and more rapid fi sheries development (article 7(6)). These

confl icting themes permeate the law.

The uncertainties are exacerbated by the absence from the law of substan-tive standards for either fi sheries management or conservation. To be sure, MSY

remains the bottom line. However, the law does not prescribe how this should be calculated. Furthermore, in order to ensure sustainability of fi sheries, pursuant

to article 11(1), the minister may declare the existence of a critical condition that endangers fi sh supply, fi sh species or fi sh areas; however, the law specifi es no

cri-teria as to when such a condition might exist. With respect to conservation, article 13(1) states that ‘efforts shall be [made] for the conservation of the eco system, conservation of fi sh species, and conservation of fi sh genetics‘, and article 13(2)

provides that such provisions are to be elaborated through regulation. There is no specifi cation of how much to conserve, to what extent, or by what means. In

addi-tion, important terms either are not defi ned or are defi ned vaguely (e.g. ‘a fi shing

vessel’ is any vessel or fl oating device used to catch fi sh, and ‘fi shing’ is defi ned as

any activity intended to catch fi sh with any device or method). These defi nitions

are too simplistic, broad and over-inclusive to have any meaningful bearing on implementation and enforcement.

Where standards do exist, they are ambiguous and broad. For example, article 12(1) prohibits persons from conducting activities that will result in pollution or degradation of fi sheries resources or the fi sheries environment; article 16(1)

pro-hibits persons from importing, exporting, supplying or farming fi sh in a manner

that is detrimental to the community, fi sh farmers, fi sheries resources or the

envi-ronment; and article 23(1) prohibits persons from using raw materials, supple-ments, additives or equipment that endanger human health or the environment. The law offers no insights into the meanings of such profoundly broad prohibi-tions or the standards that determine what is considered detrimental or a danger to health or environment.

The new law does improve the legal certainty of the fi sheries permit scheme,

in a subtle but important manner. Where Law 31/2004 spells out in great detail the necessary permits for conducting fi sheries activities, the original Law 9/1985

was silent. Article 10 of that law merely required a fi sheries permit (izin usaha

perikanan), and it was Regulation 15/1990 that created and fl eshed out the

per-mit system. In codifying this system in statute, Law 31/2004 should improve the business climate to some degree by increasing the legal certainty associated with permits.

The mechanics of the new legal framework under Law 31/2004 do not change substantially from the existing framework in terms of licences and permits. A fi

sh-eries business licence (surat izin usaha perikanan, or SIUP) is required for any entity carrying out fi shing business (article 26(1)). A fi shing licence (surat izin penangkapan

ikan, or SIPI), must be issued to fi shing vessels (domestic and foreign-fl agged) to

conduct fi shing activities, and is a component of the SIUP (article 27). Licences

are issued for certain types of gear and vessel sizes. A licence for transporting

cBIEAug07.indb 209

cBIEAug07.indb 209 27/6/07 5:33:44 PM27/6/07 5:33:44 PM

harvested fi sh (surat izin kapal pengangkut ikan, or SIKPI) is also required for

ves-sels transporting fi sh (article 28). In addition to these three main permits, vessels

are required to register with MMAF (article 36) and, before sailing, are required to obtain a sailing permit from the local harbour-master (article 42), a prerequisite for which is a certifi cate of operational adequacy from each port’s fi shery control

offi cer (article 43). The important change is that these details are now contained in

the text of the law, instead of being scattered across several implementing regula-tions as they were under Law 9/1985.

Law 31/2004 also contains a series of provisions designed to support small-scale fi shers. Article 6(2) states that fi sheries management shall take into account

adat (traditional) law, indigenous customs and community participation (consist-ent with article 18B of the constitution). Small-scale fi shers receive two types of

benefi ts: exemptions from regulatory burdens; and affi rmative incentives and

assistance. They are not required to obtain a SIUP (article 26(2)) or to pay fi sheries

fees (article 48(2)). They are entitled to access to credit programs to be established by the ministry, and to education and training (article 60(1)). While they are free to fi sh throughout Indonesian waters (article 61(1)), the only procedural

require-ment is that they register free of charge with the local fi sheries agency (article

61(5)), and the only substantive requirement is that they comply with the conser-vation regulations to be promulgated by the minister (article 61(3) and (5)).

The new fi sheries law has more detail than the old as to prohibitions and

pre-scriptions. As Cacaud (2001) observes, ‘[t]he Fisheries Act of 1985 is a short text enacted at a time when it was still believed that fi shing effort and fi shing

capac-ity could continue to increase without adversely impacting the abundance of the

fi shery resources‘. Article 6(1) of Law 9/1985 had a blanket prohibition against

‘conducting fi sh catching and fi sh cultivation activities by utilising materials

and/or devices that can endanger the habitat of fi sh resources and their

envi-ronment‘, and article 7(1) had a blanket prohibition against ‘activities that may cause pollution and damage to fi sh resources or their environment‘. These articles

only implicitly banned the most destructive of fi shing practices such as using

cya-nide or explosives. Prosecutions had to demonstrate causal links between specifi c fi shing practices and gear types and damage to fi sh resources and the marine

environment. In addition to the small number and non-specifi c nature of its

pro-hibitions, Law 9/1985 did not provide for any meaningful management frame-work: as argued by Cacaud (2001), ‘it does not provide for any fi sheries planning

tools (e.g. fi sheries management plans); provisions with regard to enforcement

should be reviewed (e.g. designation of enforcement offi cers, determination of

enforcement offi cers’ powers); and it contains few monitoring measures (e.g. data

collection, logbook, register of fi shing vessels)’. Gillet (2000) also notes

ambigui-ties in Law 9/1985 and other laws and regulations in the defi nition of ‘fi sheries

management‘.

In contrast, Law 31/2004 prohibits a long list of fi shing activities. For example,

article 8 prohibits the use of chemical substances, biological substances, explosives, gear and other means or equipment that could harm or endanger the sustainabil-ity of fi sheries resources or their environment. With the gear types themselves

prohibited, prosecutions need only to demonstrate use of the gear, rather than a more complicated causal link between the gear type and a prohibited impact. In addition, penalties in the new law are more carefully crafted: they apply to the

cBIEAug07.indb 210

cBIEAug07.indb 210 27/6/07 5:33:45 PM27/6/07 5:33:45 PM

fi sher directly, as well as to the captain of the vessel, and the proprietor of the

ves-sel or the fi shing company. To be sure, the prohibitions could be stronger. There

is an exception for use of these substances and techniques for ‘research purposes’ (article 8(5)), a term which is undefi ned but may allow a large loophole. And they

could be clearer: the same generic prohibition against any and all fi shing types

that damage the environment that appeared in article 7 of Law 9/1985 is repeated in similar language in articles 8 and 12 of Law 31/2004, and can include most of the fi shing gear types used by fi shers and permitted by the MMAF.

The biggest difference between the original fi sheries law and the new one is the

increased emphasis on enforcement and adjudication. Law 31/2004 establishes a fi sheries tribunal to handle prosecutions for violations of fi sheries regulations.

This is a unique attribute in the Indonesian judicial system—offering a specialised venue for cases within a particular sector. The goal is to provide more expeditious, transparent and honest decisions than in the past. The fi rst such courts were to be

established in the country’s largest ports—Jakarta, Medan, Pontianak, Bitung and Tual—within two years of the law’s enactment.

However, the key determinant of whether Law 31/2004 will adequately address the problems facing Indonesia’s fi sheries rests with its interpretation in

imple-menting regulations. To underscore the uncertainties and lack of clarity in Law 31/2004, and to highlight just how much direction within fi sheries management

remains unclear at this point, one can look at the number of key issues that are left to be elaborated in future implementing regulations. All told, Law 31/2004 provides for 36 implementing regulations on topics ranging from the issue of

fi sheries permits to imports and exports; fi sh harvesting, processing and

trans-porting; conservation; research and development; and outreach. The appendix to this paper provides a complete list of all required implementing regulations, the provisions of the law to be elaborated in those regulations, and the strategy of the ministry in drafting them.

Regulations

Given the dearth of literature on fi sheries laws—and what little there is

gener-ally starts and stops at the statutory level, without discussion of regulations or decrees—it is worth reviewing at least the litany of regulations and decrees on the books, with a fuller analysis of their contents and interplay with one another reserved for a subsequent paper. As a prefatory note, Patlis (2005a) discusses the hierarchy of Indonesian law, with the general order of authority as follows: the constitution; statutes (undang-undang); government regulations (peraturan pe merintah); presidential decrees (keputusanpresiden); ministerial decrees ( keputusan menteri); provincial laws; and district laws. With the enactment of Law 10/2004 on the Establishment of Laws, presidential and ministerial decrees (keputusan) were renamed presidential and ministerial regulations (peraturan).

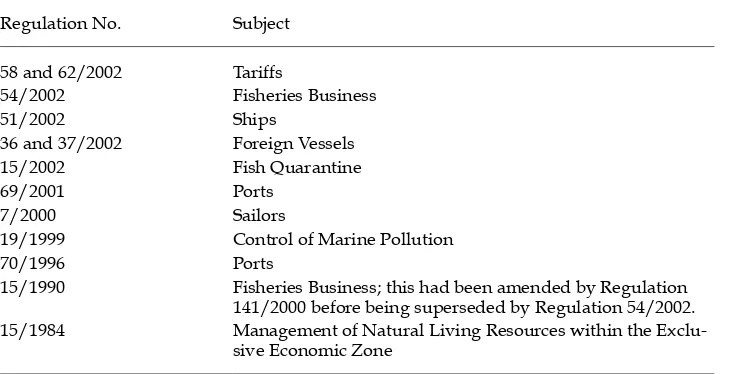

A number of government regulations governing the fi sheries sector were

prom-ulgated to implement Law 9/1985. Among the more important recent regulations relating to fi sheries and marine resources are those listed in table 3.

The primary regulation is No. 54/2002 relating to Fisheries Business, which gives considerable detail about the permit scheme for fi sheries activities. It

dis-cusses the various permits, when they are required, how to obtain them, for how long they are valid and where they are valid. Regulation 51/2002 on Ships

cBIEAug07.indb 211

cBIEAug07.indb 211 27/6/07 5:33:45 PM27/6/07 5:33:45 PM

addresses the various permits required for operating and owning a ship in Indo-nesian waters, regulations for foreign-fl agged vessels, and criteria for

seaworthi-ness of vessels. Regulation 15/2002 on Fish Quarantine addresses certifi cation for

the hygiene and health of fi sh in transit, which is to be provided by local offi cials

in the places of shipment and arrival. Regulation 69/2001 defi nes and regulates

the three major types of ports in Indonesia—national, provincial and district. Article 40 of that regulation specifi cally mentions fi shing ports, but only in

pass-ing, and leaves further elaboration to a lower ministerial decree—MMAF Decree 46/2002 on the Organisation of Coastal Fishing Ports.

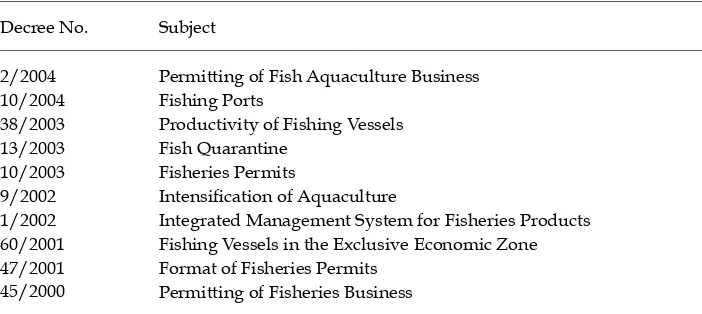

There are not many presidential decrees on fi sheries. Presidential Decrees

14/2000 and 174/1998 allow for the conveyance of seized fi shing vessels to

com-munity fi shers. One of the more important decrees, Presidential Decree 85/1982,

addresses the impact of shrimp trawling on near-shore coastal waters specifi cally

by prohibiting trawling for shrimp in western Indonesian waters. Dozens of min-isterial decrees and regulations govern fi shing in general. A partial list of the more

important decrees is given in table 4.

As is often the case in Indonesia, the transitional nature of the new fi sheries

law and the status of implementing regulations under the old law leave fi sheries

in a state of legal fl ux. Article 109 of Law 31/2004 provides that ‘all implementing

regulations of Law 9 of 1985 concerning Fisheries are still valid, as long as they are not in contravention of, and have not been repealed by, this law‘. Patlis (2005a) discusses the problems with this legal formulation, known as an ‘implied repeal‘. With no explicit statement of which regulations might be in contravention of the new law, and no particular arbiter—and given the inherent vagueness and exces-sive breadth of many provisions of the new law—there is no clear sense of which regulations remain in force and which are invalidated, albeit implicitly.

There are both mitigating and exacerbating factors to be considered in deter-mining what the transitional period of the next few years will be like. On the one hand, to the extent that Law 31/2004 specifi es the fi sheries permit system, it adopts

TABLE 3 Important Regulations Relating to Fisheries and Marine Resources

Regulation No. Subject

58 and 62/2002 Tariffs

54/2002 Fisheries Business 51/2002 Ships

36 and 37/2002 Foreign Vessels

15/2002 Fish Quarantine 69/2001 Ports

7/2000 Sailors

19/1999 Control of Marine Pollution 70/1996 Ports

15/1990 Fisheries Business; this had been amended by Regulation 141/2000 before being superseded by Regulation 54/2002. 15/1984 Management of Natural Living Resources within the

Exclu-sive Economic Zone

cBIEAug07.indb 212

cBIEAug07.indb 212 27/6/07 5:33:45 PM27/6/07 5:33:45 PM

and reinforces the pre-existing regulatory framework, serving to strengthen legal and business certainty in this regard. Where Law 31/2004 is vague or silent on the details (as is typical of most statutes, deferring to implementing regulations for the details of a management regime), it can easily accommodate the pre-existing regulatory framework. Given that this framework is relatively new—the major

fi sheries business regulation is No. 54, promulgated in 2002—there is a strong

likelihood that Law 31/2004 was drafted with this new regime in mind, and is unlikely to change it. On the other hand, the delays experienced in promulgating new regulations—the fi rst series of regulations on capture fi sheries, aquaculture

and conservation, scheduled for completion in 2006, were not yet ready at the time of writing in early 2007—increase uncertainty and confusion about how to implement Law 31/2004, and which regulations currently apply.

Institutions

This section provides a brief history and overview of the various agencies involved in fi sheries management, more to underscore the complications involved in fi

sh-eries management than to analyse these institutional arrangements critically. Historically, fi sheries were managed under the Ministry of Agriculture. In 1999,

President Abdurrahman Wahid established an early version of the MMAF, known as the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Exploration (Dahuri and Dutton 2000), which pulled in civil servants from the Ministry of Home Affairs, the National Development Planning Agency, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Forestry (for marine conservation purposes). As the ministry’s mandate evolved to cover broader issues in marine conservation, management and exploitation, its fi rst minister, Sarwono Kusumaatmadja, changed its name to the current one.

The creation of the MMAF in 1999 led to a sharp improvement in, and strength-ening of, the management of coastal and marine resources. The ministry has consolidated and coordinated policies across all aspects of management of those resources. The focus has shifted from marine exploitation to marine management, with strong institutional recognition of conservation. While the ministry is still in the process of implementing those new policies, and much work remains to be

TABLE 4 Important Ministerial Decrees Governing Fishing

Decree No. Subject

2/2004 Permitting of Fish Aquaculture Business 10/2004 Fishing Ports

38/2003 Productivity of Fishing Vessels 13/2003 Fish Quarantine

10/2003 Fisheries Permits

9/2002 Intensifi cation of Aquaculture

1/2002 Integrated Management System for Fisheries Products 60/2001 Fishing Vessels in the Exclusive Economic Zone 47/2001 Format of Fisheries Permits

45/2000 Permitting of Fisheries Business

cBIEAug07.indb 213

cBIEAug07.indb 213 27/6/07 5:33:46 PM27/6/07 5:33:46 PM

done to integrate its diverse missions fully, it shows great signs of promise. The current ministerial decree establishing the structure and organisation of the min-istry is Decree Kep.05/MEN/2003.

The one fundamental institutional defi ciency in the MMAF’s scope concerns

the conservation of non-fi shery marine living resources, such as endangered

marine species, coral reefs, grasses and mangroves. Original authority for living resources and biological diversity generally, including habitat conservation, rests with the Ministry of Forestry. However, residual authority for marine affairs gen-erally rests with the MMAF. This authority includes fi sheries resources, fi sheries

habitats, coral reef habitats and, in a general and broad way, marine biological diversity. The MMAF is thus responsible for many aspects of marine and coastal conservation (except the establishment of certain types of marine protected areas, and the management of certain laws, such as the Convention on Biological Diver-sity ratifi ed through Law 5/1994, and Law 5/1990 on Conservation of Natural

Living Resources and Their Ecosystems). This division of management authority has slowed and complicated conservation efforts, and should be corrected. The MMAF has competence over marine and coastal resources, but this should also include protecting their habitat under existing legal authorities and in accordance with the designation of special marine protected areas.

In addition to creating the ministry, with the issue of Presidential Decree 161/1999 President Wahid established the DMI, with the lofty mission of co ordinating and improving overall policy and management of marine resources, activities and areas. The board’s membership consists of 13 central government agencies, each having some role in marine and coastal policy and management. The chair is the president, and the vice-chair is the Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries. Total membership is 27, with the remaining members being academic, NGO and business representatives. The board has been relatively ineffectual in coordinating all sectors and line ministries whose actions and policies affect coastal and marine resources. It meets irregularly and infrequently, and has a very limited budget to maintain staff and operations. Moreover, its authority is very broad, but as yet unclear and ill-defi ned. To date, it has issued no

substan-tive decree or document relating to marine management, but merely a series of decrees addressing membership and logistics.

The ministry, through Ministerial Decree 994/Kpts/Ik.150/9/99 issued in 1999, established coordinating councils for fi sheries management decisions (Forum

Koor-dinasi Pengelolaan Pemanfaatan Sumberdaya Ikan, or FKPPS). There is one FKPPS at the central level, and one in each of nine fi sheries management areas (Cacaud

2001). The national FKPPS meets once every two years, and last met shortly after the enactment of Law 31/2004 to discuss its implementation (FKPPS Nasional 2004). It identifi ed the need to develop fi sheries management plans, and to improve

the accuracy of catch data and estimates of fi sh abundance, identifi cation of fi

sher-ies potential, coordination of research and enforcement, and the permit system.

Regional and international developments

The original Law 9/1985 was enacted just before Indonesia ratifi ed the UN

Con-vention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (through enactment of Law 17/1985). However, it adheres to two of the basic tenets of fi sheries management contained in

UNCLOS. Article 61 of UNCLOS provides that coastal states should determine the

cBIEAug07.indb 214

cBIEAug07.indb 214 27/6/07 5:33:46 PM27/6/07 5:33:46 PM

total allowable catch for fi sheries within their EEZ, and article 62 provides that, to

the extent that a coastal state does not attain capacity, it should allow foreign-fl agged

vessels to fi sh. While the tenets of the law are followed—article 9 of Law 9/1985

allows only Indonesian nationals to engage in fi shing unless otherwise allowed

under international law—implementation and enforcement have suffered.

In addition, Law 9/1985 was enacted long before other important international treaties and standards governing fi sheries management came into effect. Among

the most important are the ‘Compliance Agreement‘ (the Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fish-ing Vessels on the High Seas, approved on 24 November 1993), the Fish Stocks Agreement, completed on 4 August 1995, and the Code of Conduct for Responsi-ble Fisheries, completed in 1995, which is voluntary. In addition, Indonesia itself played an important role in the drafting and signing, on 5 September 2000, of the Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacifi c Ocean. These treaties, as well as the

pre-cautionary principle, the concept of sustainable fi sheries management, and

mean-ingful procedures for enforcement that are embodied within the treaties, were thus not codifi ed in statute (although they were included in lower-level

regula-tions and decrees) before the enactment of Law 31/2004.

However, Law 31/2004 is, in many places, vague enough to make it diffi cult

to discern how Indonesia’s obligations under international fi sheries laws are to be

carried out. There are no specifi c references to the precautionary principle in Law

31/2004, for example. At the same time, there are generic references to the need to comply with international law. For example, in discussing the TAC, the elucidation of article 7 of the law states that ‘the implementation of the principle of total allowa-ble catch shall take into account international obligations with regard to fi sheries’.

At the time of writing, Indonesia was considering ratifi cation of the Fish Stocks

Agreement, also known as the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provi-sions of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea of December 10, 1982 relat-ing to the Conservation and Management of Straddlrelat-ing Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (the UN Fish Stocks Agreement, or UNFSA).7 This would greatly improve the prospects of sustainable fi sheries within the region. For

exam-ple, it would strengthen the role of regional fi sheries management organisations

(RFMOs), and improve capacity building for science, monitoring and enforcement. Under articles 21 and 22 of the UNFSA, states party to the agreement can board and inspect vessels sailing under the fl ags of other parties on the high seas.

However, ratifi cation of the UNFSA would also present Indonesia with a

number of challenges in implementation. Among its requirements, the UNFSA places great emphasis on improving data relating to straddling stocks, in order to make sustainable fi sheries management decisions consistent with the

pre-cautionary approach. This may be diffi cult for Indonesia and other developing

countries, because of limited personnel, training, budget resources and infra-structure. To comply with these provisions, Indonesia may need to expend addi-tional funds on research and information. Also, effective monitoring, control and surveillance of vessels fl ying its fl ag (as set out in the duties of fl ag states under

7 Straddling stocks of fi sh migrate between, or occur in both, the high seas and the EEZ of

one or more states.

cBIEAug07.indb 215

cBIEAug07.indb 215 27/6/07 5:33:46 PM27/6/07 5:33:46 PM

article 18 of the UNFSA) or of those licensed to operate in its EEZs, may require additional costs, staffi ng, training, and enforcement infrastructure (vessels, port

samplers and inspectors, vessel record databases and tracking systems).

ENFORCEMENT

Law enforcement is an integral ingredient in fi sheries management. There is a

near-universal recognition that many of the pressures on Indonesian fi sheries—over-fi shing; use of destructive fi shing techniques; fi shing in prohibited, protected areas;

and lack of reporting—stem from defi ciencies in fi sheries law enforcement. Cacaud

(2001) and Gillet (2000) cite several studies documenting poor enforcement and sur-veillance. The issue is highly complex: there are disparate reasons for individual defi ciencies; a wide range of social, economic, cultural and ecological effects of poor

enforcement; and a broad array of potential cures and mitigation strategies. Maritime enforcement is conducted by the navy and the water police, as pro-vided originally in a series of laws relating to maritime governance: Law 1/1973 on the Continental Shelf; Law 5/1983 on the EEZ; Law 9/1985 on Fisheries (super-seded by Law 31/2004); and Law 17/1985 ratifying the UN Convention on Law of the Sea. The police (POLRI) was part of the military until 2000, when President Wahid issued Presidential Decree 2/2000, formally separating the two forces. According to the US Department of State (2005):

[S]ince POLRI was separated from the TNI in mid-2000, the Maritime Police Di-rectorate has lacked training, equipment, and leadership to perform enforcement duties effi ciently. The Maritime Police will need to be modernised over the next

several years … [and] will need a new strategic plan and modernisation of current operational units. Maritime Police personnel will require training as well as equip-ment and technical assistance to patrol ports and waterways effectively.

While Indonesia has requested aid from the US for maritime law enforcement, the reason is to address drug and terror-related crimes, not fi shing violations. To be

sure, there will be ancillary benefi ts for fi sheries management in having a better

trained maritime police force, but that is of secondary importance internationally. In addition to the formal arrest and seizure authority held by the navy and water police, there are a number of agencies with authority for patrols and deten-tion at sea, including the MMAF. There is a loose body known as the Coordinating Body for Maritime Safety (Badan Koordinasi Keamanan Laut, or Bakorkamla), established in 1971 and comprising representatives from the navy, police, customs department and Ministry of Justice, which historically has not been effectual. This fragmented approach to enforcement has led to protection of the parochial inter-ests of agencies, limited funding and poor prioritisation of effort. Several options for improving maritime enforcement have been discussed routinely among policy makers. One possibility is the formation of a single new centralised monitoring and enforcement agency that can focus on enforcement of maritime laws other than those relating to national security and safety, which are the responsibility of the navy and water police. Such an alternative would be similar to the US Coast Guard (Knight 2001). Another possibility is to revitalise the Bakorkamla: this has been attempted a number of times, most recently with the issue of Presiden-tial Regulation 81/2005. However, there is still pessimism among experts about whether this will signifi cantly improve matters (Kompas, 18/3/2006).

cBIEAug07.indb 216

cBIEAug07.indb 216 27/6/07 5:33:47 PM27/6/07 5:33:47 PM

Erdmann and Bishop (2004) identify a comprehensive list of 16 ‘challenges‘ to tropical marine enforcement (table 5). These ‘challenges’—a euphemism for defi ciencies experienced in both developing and developed countries around the

globe—fall into three basic categories of enforcement problems: TABLE 5 Sixteen ‘Challenges’ to Tropical Marine Enforcement

There is a pronounced lack of high-level recognition (from police, politicians and the judicial system) of the seriousness of marine resource crimes.

•

Laws governing marine resource use are frequently unclear to both resource users and enforcement offi cials, and were often designed without practical enforcement

measures in mind—creating ‘legal loopholes’ and hindering efforts at prosecution. •

Sanctions for marine crimes are often [so] weak or small ... that they are simply considered a ‘cost of business’ and not a true deterrent.

•

Corruption remains a serious problem, with frequent involvement of high-ranking political, military or police offi cials in lucrative marine resource crimes.

•

Prosecution of cases of marine resource crimes by foreign vessels is often hampered by international diplomacy and ‘leveraging’ by offending vessels’ governments. •

Overlapping jurisdictions and a lack of coordination between and even within the agencies responsible for management of coastal and marine resources hinder effective enforcement efforts.

•

In many countries with a strong, centralistic government, national laws governing marine resource use are in direct confl ict with village-level customary law and

traditional tenure practices. •

Lack of local community involvement in design and implementation of enforcement systems often results in the perception that laws are being imposed ‘from the outside’ and can lead to resistance and lack of local support.

•

Local citizens wishing to report a marine resource crime often do [not] know the proper reporting channels or which agency is their designated ‘fi rst contact’.

•

Reporting citizens and even enforcement offi cials are often harassed and threatened

by those involved in or accused of marine environmental crimes. •

Most tropical MPAs [Marine Protected Areas] suffer from insuffi cient funding,

human resources and equipment to carry out regular enforcement activities. •

Even when MPAs provide funding for patrols, there is frequently no source of funding for keeping arrested perpetrators in jail or for investigation or court costs. •

International donors and funding agencies, including some international environmental NGOs, are often reluctant to fund ‘cold and thorny’ enforcement activities, opting instead for ‘warm and fuzzy’ management initiatives such as ‘alternative livelihood programs’, which are considered less controversial. •

In many tropical developing countries, local NGOs frequently strongly oppose marine enforcement programs (on the grounds that they unfairly target ‘poor

fi sherfolk’) and may go to great lengths to hamper enforcement efforts or discredit

these efforts in the local media. •

Frequent turnover in staffi ng of enforcement posts, prosecutors and judges

further complicates efforts to train these critical constituents of an effective marine enforcement system.

•

Practical enforcement issues are rarely a primary consideration in the design of MPAs or coastal management projects.

•

Source: Adapted from Erdmann and Bishop (2004).

cBIEAug07.indb 217

cBIEAug07.indb 217 27/6/07 5:33:47 PM27/6/07 5:33:47 PM

• development: drafting of laws and regulations; clarity and knowledge of sanctions; fi ne-setting; and consultation with, and participation of, the

regulated community and civil society;

• implementation: jurisdiction of agencies; levels of funding and training; and corruption among agents;

• adjudication: dismissal of cases because of evidentiary problems; corruption; and levels of training and knowledge among judicial members.

All three categories of problems manifest themselves in Indonesian fi sheries

enforcement. One example concerns the prohibition of bomb and cyanide fi

sh-ing. There is a long-held and widely accepted view among policy makers, NGOs and the media that bomb fi shing and cyanide fi shing are strictly prohibited. The

fact is that, prior to Law 31/2004, there were no provisions at all on the books, in either the statutory or the regulatory framework, that explicitly prohibited bomb and cyanide fi shing. What existed was the generic provision in article 6(1) of Law

9/1985 that stated: ‘Any person or corporate body shall be prohibited [from con-ducting] fi sh catching and fi sh cultivation activities by utilising materials and/or

devices that can endanger the habitat of fi sh resources and their environment‘. To

be sure, the elucidation of this article makes specifi c reference to bomb fi shing and

cyanide fi shing, stating:

[t]he utilisation of explosives, poisonous substances, electric current, etc. not only kills the fi sh, but can also cause damage to their environment and infl ict losses on fi shermen and fi sh farmers. If damage occurs as a result of the utilisation of said

substances and devices, the recovery to its previous condition will need a very long time, or might not even be possible. Therefore, the utilisation of said substances must be prohibited.

This formulation does not prohibit bomb fi shing and cyanide fi shing a priori.

Rather, it places a burden upon the prosecutor to prove that fi sh resources, habitats

and the environment have been endangered as a result of their use. Mark Erdmann of Conservation International (pers. comm.) recounts several instances in which judges have dismissed cases against bomb fi shing and cyanide fi shing owing to

lack of evidence of harm to the resource. Law 31/2004 fi xes this problem with an

explicit prohibition of bomb and cyanide fi shing.

The MMAF is taking a number of actions to address enforcement problems. Some are rather perfunctory in nature, without much indication that they will resolve the current problems in enforcement. Examples include:

• Ministerial Decree 2/2002 regarding Guidance on Enforcement Monitoring for Capture Fisheries. This document identifi es who and what is entailed in

enforcement actions, for example, which agencies are involved, and which documents should be checked. It identifi es no less than eight required permits

and four other general documents about the legality of the vessel itself. It is helpful to have one decree that restates all the permits otherwise required across scores of decrees, but it will not increase patrols.

• Ministerial Decree 1/2003 on the Establishment of a Team for Accountable Reporting (Tim Penyusunan Laporan Akuntabilitas Kinerja Instansi Pemerintah). • Ministerial Decree 25/2004 on Guidance for Functional Monitoring within the MMAF. This provides for a series of audits intended to review operations and functions within the ministry.

cBIEAug07.indb 218

cBIEAug07.indb 218 27/6/07 5:33:47 PM27/6/07 5:33:47 PM

One promising development is the formation of the fi sheries tribunals. These

tribunals are intended to expedite and facilitate fi sheries claims. It is to be hoped

that they will provide a more transparent, honest and knowledgeable forum for adjudicating cases than exists at present. Initially, fi ve tribunals will be

estab-lished, in the country’s largest fi shing ports at Jakarta, Medan, Pontianak, Bitung

and Tual. Each tribunal will consist of one career judge from the municipal court and two ad hoc judges. However, the tribunals will take a minimum of two years to set up and, as we wait for the implementing regulations, it is diffi cult to know

whether they will succeed. However, their very creation spells a positive step for enforcement and prosecution of fi sheries violations.

Another promising development is the recent creation of a community-based

fi sheries monitoring program (Sistem Pengawasan Masyarakat), as set out in

Ministerial Decree 58/2001. This system provides for community involvement in fi sheries enforcement: communities participating in the program (Kelompok

Masyarakat Pengawas) receive radios and have access to a central monitoring and reporting system in the MMAF that operates 24 hours a day. If they witness illegal

fi shing they can report it to the MMAF, which will work with enforcement

per-sonnel to respond as quickly as possible. The system is modelled on Indonesia’s national system of neighbourhood patrols (Sistem Keamanan Lingkungan), long in existence and codifi ed in Presidential Decrees 28/1999 and 29/1999, and in

articles 10 and 11 of Law 2/2002 on the Police. Indeed, the MMAF ministerial decree promoted the program so keenly that it awarded prizes to the three most active communities (Ministerial Decree 3/2004).

FUTURE PROSPECTS FOR FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

This section discusses some of the initiatives and approaches the government is considering, and some that it might wish to consider, in order to improve fi sheries

management for economic, ecological, social and cultural benefi ts.

Institutional strengthening

While the creation of the MMAF consolidated marine management by the central government, there are still residual issues—such as the jurisdictional dispute over marine conservation with the Ministry of Forestry—that need to be resolved. In addition, within the ministry there needs to be a better harmonisation of its vari-ous missions, including conservation, research, and increasing fi sheries output.

With the general concern to accelerate economic growth, the ministry has been under pressure to expand fi sheries output, and the conservation mission has

suf-fered as a result. This internal contradiction is found in many countries. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which manages both fi

sher-ies and protected marine resources, is often caught between competing goals, for example. The ministry’s research agenda has supported fi sheries production more

extensively than conservation, although with the establishment of its Sea Partner-ship Program, launched with the help of the USAID Coastal Resources Manage-ment Program (Tighe et al. 2003), and now funded by the World Bank, research and extension are receiving more funding and attention than ever before.

Institutional strengthening needs to focus on the coordinating bodies. Bakor-kamla was discussed earlier. The DMI also needs to be revitalised. First, it must

cBIEAug07.indb 219

cBIEAug07.indb 219 27/6/07 5:33:48 PM27/6/07 5:33:48 PM