Urban Design Research Reflection Lucy Montague

PhD candidate, Edinburgh College of Art

Abstract

Whilst traditional research degrees are well established as having textual output, the development of design as an integral part of the research process and product is

emerging in a number of disciplines, including my own – architecture and urban design. Throughout architectural and urban design education, design skills are cultivated and become inextricably linked to the parallel skills of problem solving and communication. It seems appropriate then that this means of exploring and expressing ideas should be able to extend beyond taught programmes into research, broadening and enriching the methodological potential. At present any evidence of this appears to be more implicit than explicit.

This paper explores the different issues around research by design in relation to urban design and reviews some of the emerging and established approaches. It then considers the approach which I have adopted for my own work. An initial review of the literature, illustrates that four categories can be determined: quasi-scientific, creative practice, speculation and reflection. These methods deal with design in

different ways – generative, analytical or illustrative – and within each there is a variety of components and structures. I have chosen to move forward with the reflective

approach as it centres the designer within the research with a clear understanding of the design process which is made explicit.

Urban design is a creative discipline in which there is normally a pre-requisite for clients to commission the work and consequently the objectives are prescribed from outside. An array of external pressures is inherited such as budget, site and regulations and the designer is required to respond to all of these. With this central role, using the model of the reflective practitioner, I argue that the researcher/designer has an

opportunity to reflect on the design process relative to the external context and explicit and implicit theoretical influences.

Keywords. Design; urban; reflection.

Introduction

Increasingly there is an argument to be made for design as a skill, activity and output to extend into academic research within design disciplines. One such discipline is urban design - one of several fields within the built environment in which the primary concern is design in its broadest sense. It is the means and the medium through which investigations are made, problems are resolved and recommendations are communicated.

An initial review of literature on research by design revealed that there is relatively little formal discussion taking place about the nature, structure and limits of this methodology. Further review, including unpublished material and discussions with academics within related fields, indicated that there may be four categories. In each, the role of design has been considered, as well as the

development of these methodological approaches for design as a process distinct from other creative practices and more specifically for urban design.

The starting point for this work was a requirement to find a methodology which would allow investigation into the relationship between theory and praxis in urban design. This has been the objective of the work presented in this paper – to find a way to address my topic with research by design.

Design

Design is process, product and discipline. Using the premise that both process and product could be components within research an examination of product and process reveals possible definitions. Although there is some disagreement in defining urban design’s activities as a discipline (Cuthbert, 2007) and in defining its output, it is possible to articulate an understanding of both for the purposes of this work.

Design Product

The urban design product can be broken down into a site evaluation (analytical site-specific document), development framework (primarily two dimensional and textual strategic document governing medium to long term plans) and masterplan (three dimensional spatial proposal and accompanying process of implementation). This process is sequential, the project brief along with the understanding and conclusions gained from the site evaluation informing the development of both the framework and the masterplan as an appropriate response or relevant manifestation.

Design Process

In contrast with this, design as a process is “associated with a mystique of practical competence”

(Schön, 1983). It is argued that this intangibility is because in the creative process, intuition and perception have a significant role in the way a designer operates (Zeisel, 2006). This enigmatic quality of design seems to not only be a common perception but seen as a tribute to the skill and talent of a designer and in fact something to celebrate (Downton, 2004). Whether founded or not, there is a key difference between design and research as the former is generative and the latter, analytical.

There might be two ways in which thiscould be approached. One is deconstruction through the stratification relating to stages of work (described under design product), and the other is to

understand the process as a series of activities which the designer undertakes i.e. the process of the designer.

Looking at the overall work of an urban design it could be broken down into the following stages. When a commission (development brief) is received the urban designer should first evaluate it (the relevant site and briefing document) through the gathering and analysis of information, both qualitative and quantitative, so that an understanding is gained of the context within which they are working. This equips the designer with a picture of the context which can then inform the generation and development of specific outputs (design proposals) determined by the brief. In summary, the urban designer has a brief and site which specify a context and an intended outcome. As ideas are generated they are considered against the requirements of the site and brief in order to test their appropriateness.

exploratory, hypothesis and move testing - and that design practice in its broadest sense uses all of these in combination (as opposed to research which strategically isolates one).

Exploratory experiment

“…an action is taken only to see what follows, without accompanying predictions or expectations…” (Schön, 1983)

It is probing and playful in nature and a success when it leads to the discovery of something that exists. It is demonstrated in a child’s exploration of their environment, an artist’s juxtaposition of different colours and a scientist’s examination of a new material.

Move testing

“…take action in order to produce an intended change.” (Schön, 1983)

A move can be affirmed or negated. You may successfully achieve the intended result but others may occur as well or instead. Examples given for this type of experiment include a chess player moving a pawn to protect his queen and a parent bribing their child to stop them crying.

Hypothesis testing

“…tries to produce conditions that disconfirm each of the competing hypotheses.” (Schön, 1983)

Testing using the process of elimination with the hypotheses which most successfully resists refutation being accepted.

Considering these modes of testing in design practice relative to urban design practice, it appears that the first mode of experimentation – exploratory – is effectively trial-and-error. As such it has no strategy for achieving the intended aims and outcome given by the brief and site and is therefore likely to be somewhat haphazard and inefficient. The remaining two - move and hypothesis testing – offer more sophisticated methods which can be recognised within the urban design process. Move testing could be associated with a specific design decision based up on an agreed objective whilst hypothesis testing could be seen through the creation of various design options which are tested against agreed objectives to find the most successful one. It is possible that hypothesis testing may take place implicitly for the design practitioner, by discounting various possibilities due to

knowledge or precedence through experience. In each case, the fundamental constitution is that objectives have been confirmed before a move is made and in each case the result or results are tested against these objectives. The selection of testing mode at each stage in the design process may vary according to appropriateness or the individual designer’s working preferences. This

understanding of the practice of design can now be related to the possible roles it may occupy in academic research.

Research by design

Design is a key activity, concern and output for urban designers and it seems appropriate that this means of exploring and expressing ideas should be able to extend beyond taught programmes into research, broadening and enriching the methodological potential. As expressed briefly in the previous section of this paper, there is a disparity in the nature of design and the nature of research due to one being generative and the other analytical. This potential conflict is indirectly commented on by Garfinkel who states that ethnographic study supports the active involvement of the researcher and accepts that this inevitably affects the material being handled and/or results produced (Garfinkel, 1967). Coyne explicitly states that when using design as a methodology, “…research accepts these tenets of involvement, but actively deploys intervention as a research tool.” (Coyne, 2006). Taking this position, generative design could occupy an integral role in research.

One widely accepted description of academic research is that it must consist of a “stated research proposal, based on an analysis of current knowledge and understanding, a documented research process, with a clearly identified method, and a research product which can be critically assessed by the peer group through some form of publicly available format.” {{50 Jenkins, Paul 2011}}. It is possible then that What might be accepted by the peer group as good design might not be accepted by the peer group as good research and vice versa. Instead it is the process of

investigation and its relationship to a specified research question and output that is crucial. Despite the variations in approach between institutions, what is commonly understood is that research by design has both a textual and a design output. This regulatory obligation means that a relationship between the two parts is required. One can postulate that the link may be established by one element contextualising, expanding, illustrating or interrogating the other. However, methodologically, there is more than one way of engaging this relationship.

Approaches

In the interests of making an appropriate choice for my PhD, I have investigated the existing body of work and my findings can broadly be categorised into four alternative strategies for research by design. These are quasi-scientific, creative practice, speculation and reflection.

Drawing on the traditional scientific model for research, this approach sets a theoretical hypothesis which is then tested using design. The generation of design is the generation of data which can then be tested against pre-determined, theoretically driven criteria in order to draw conclusions.

Because of its quasi-scientific nature this is in some ways less of a leap from traditional analytical research. As design occupies the role of data production, it is primarily product not process oriented (Coyne, 2006). Using this model it is not possible for the author to both generate the design and evaluate the design. The objectivity of analysis against the criteria would be

compromised. Therefore this approach offers the opportunity for interaction through design (Coyne, 2006) with a third party or parties producing the design element or the evaluation.

Creative practice as a methodology is well established within the field of art, where a piece such as a sculpture, installation, painting or performance is developed in conjunction with a theoretical

discussion and exhibited as part of dissemination. In contrast to the sequential quasi-scientific model in which each part is completed consecutively, creative practice is structured in such a way that design and text are parallel strands. A theoretical basis is explored and develops textually alongside the process of design. A relationship is created through the continual referral of one to the other (Forsyth, 2011).

Through design and text progressing simultaneously and the direct and consistent nature of the relationship between the two, a symbiosis is established. Comment and scrutiny of the

developmental process of design is possible as this is exposed throughout the course of the research. In this instance the researcher is also the designer. Coyne affirms that using this approach, “the creative output is integral to the research process, and may even constitute the main mode of

communication within the research discourse.”(2006). Organisationally, this allows the researcher to continually design from the start to the finish of the research project. It may also be possible that the parallel development of design and theory could happen more than once, intermittently

Two means of using design as speculation within research appear to be in existence. For the first of these the design acts as a speculative conclusion to the theoretical discussion which has preceded it (Coyne, 2006). In this instance the design could be treated as a recommendation considering or realising the outcome of the theoretical debate.

Donald Schön’s The Reflective Practitioner (1983)articulates his theory of How Professionals Think in Action and suggests approaches to the epistemology of practice. Schön’s understanding is that there are several types of experimentation, identified as hypothesis testing, move testing and

exploratory testing (as described earlier in this paper). Schön emphasises that the overarching question is ‘What if?’ and the role of the experiment is to act in order to see what the action leads to. (Schon, 1983)

The suggestion which Schön makes is reflection-in-action, in which experiment based. “The practitioner allows himself to experience surprise, puzzlement, or confusion in a situation which he finds uncertain or unique. He reflects on the phenomenon before him, and on the prior

understandings which have been implicit in his behaviour. He carries out an experiment which serves to generate both a new understanding of the phenomenon and a change in the situation.”

(Schön, 1983). He argues that knowledge is created and communicated when the professional responds to these situations “by examining practice reflectively and reflexively [leading] to developmental insight.” (Schön, 1983)

When applied to research by design, this indicates an approach in which the investigative process of design is central to the work. A theoretical context is established within which the design is created. The design process is made explicit by the researcher/designer who then retrospectively reflects. This reflection considers both the process of design and the research as a whole which allows connections to be made to the original theoretical context.

Selecting an approach

Having reviewed four approaches to research by design it is possible to appreciate that when selecting a methodology two things could be considered.

The first of these is the compatibility of an approach with an individual’s specific research question and objectives. For this to be assessed there must be a balanced understanding of the opportunities and constraints of each method. Therefore there is a match to be made, as with traditional research by dissertation, between the scope of the method and what the research is

attempting to find out. For example, the review of approaches summarised in this paper demonstrate that some methods allow scrutiny of design as process, whereas others are primarily dealing with design as a product which can be evaluated or speculated on. It is important to establish which of these is relevant to the research question being addressed – whether the information required is product or process based, or not exclusive to one or the other.

Secondly, it is important to consider what the role the researcher wishes to occupy. The researcher must decide whether to position his/herself centrally to the research or if some elements can be externalised. He/she must decide also whether the design element is to be integrally linked through the structure and approach as a process or whether it is a separate whole which locates itself within a framework; whether they wish design to be a continuous activity throughout the research process or a contained component at one point or at recurring points. These aspects must be reflected in terms of how the individual researcher would like to work, what activities he/she most enjoys, what his/her strengths and skills sets are and what his/her ambitions for the piece of work involve.

When selecting a methodology for my own PhD research, the first points of consideration were my research question and the associated research objectives:

Objectives Establish what the relationship between theory and praxis is considered to be.

Examine the role of theory in the process of urban design through the generation of design.

Reflect on the process of design in order to conclude how it was informed by theory.

I also had additional preferences which informed my decision: The desire to carry out the design myself as this is my strength, skills set and what I find enjoyable; a wish to centre myself with the research and design processes having experienced difficulties in concluding previous research which required me to remain at an ‘objective’ distance.

When collated, these determine a methodology which will allows me to: scrutinize the process of design rather than the product and the research as a whole relative to the inherited external context of urban design and to explicit and implicit theoretical influences; centre myself within the project as researcher and designer.

Having considered the four approaches described in this paper relative to these requirements and the possible ways in which they could be applied to this piece of work, I have chosen to move

forward with the reflective approach. With this model, I argue that the researcher/designer occupies a central role and therefore has an opportunity to reflect on the design process relative to the external context and explicit and implicit theoretical influences. I will be able to carry out the design element myself, which is an important facet to me individually, whilst the opportunity to consider the

research as a whole is retained through the reflective section. This reflection on the research as a whole closes the loop between the praxis (design) and theory (literature review + methodology).

The structure of my research can be described using the levels of enquiry delineated by Groat & Wang (Groat & Wang, 2002) – systems of enquiry (theoretical/contextual framework), strategy (methodological approach) and tactics (techniques).

These components share a relationship which is created by the strategy (reflection) and allows the tactics (literature review, site evaluation, design generation, commentary, analysis and reflection) to address the contextual framework (research by design).

The first two components address the two different threads of this piece of research. The first is the subject area – theory and praxis in urban design - and the second is the contextual framework – research by design. Information is gathered through a review of literature, ordered through a series of themes and creating a theoretical position. The methodology is established through examination of existing published thoughts on research by design and developed by consideration of how these may be adapted, applied and approached from my work’s particular subject.

The design component is executed as a standard design project, with a real site and live brief both of which are evaluated and inform the subsequent design proposals. A development framework and masterplan are produced. As the design process is executed, from evaluation to masterplan, it is made explicit through a commentary. This is not an analytical commentary but a recording of the moves made and the rationale behind them. This commentary then allows analysis of the

development of the design, i.e. the process not the product, to take place. After the design is completed my understanding of the design process is then reflected on relative to the issues and themes discussed within the literature review and methodology - the relationship between theory and praxis.

Conclusion

In summary, this review reveals that four approaches of research by design can be categorised -

quasi-scientific, creative practice, speculation and reflection. It also shows that the scope of these approaches differs with varying restraints and opportunities. Informed by this information, the reflective approach has been selected for this work. It addresses the requirements of the research question - chiefly by facilitating a study of the research process - and it responds to individual preferences – centring the designer/researcher within the work. The resulting structure sets a theoretical context through a review of existing literature pertaining to theory, praxis and urban design and generates a design project, the process of which is made explicit through a commentary and analysis. This is then reflected on relative to the theory discussed in the literature review and the research as a whole is subject to reflection before conclusions are\ drawn.

References

Books

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Groat, L. N., & Wang, D. (2002). Architectural research methods. New York: J. Wiley. Laurel, B. (Ed.). (2003). Design research: Methods and perspectives. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner : How professionals think in action. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Journals

Cuthbert, A. R. (2007). Urban design: Requiem for an era - review and critique of the last 50 years. Urban Design International, (12), 177-223.

Websites

The University of Sheffield. (2011). MPhil and PhD by design. Retrieved March 03, 2011, from http://www.shef.ac.uk/architecture/programmes/pgschool/research/design.html

University of Edinburgh. (2011). PhD by design. Retrieved Ferbruary 15, 2011, from http://www.ed.ac.uk/schools‐ departments/arts‐culture‐environment/graduate‐school/research/phd‐in‐design

University of Edinburgh. (nd). PhD in design: Invitation. Retrieved March 10, 2011, from http://www.ace.ed.ac.uk/PHdinDesign/text.html

Interviews

Cairns, S. (2010). Personal communication

Unpublished papers/lecture

Coyne, R. (2006). Creative and practice-led research unpublished notes. Unpublished manuscript. Forsyth, W. (2011). Masters research methods lecture

Reflective Practice in Urban Design

The role of theory in the creative process of urban design

Lucy Montague

Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Edinburgh College of Art, The University of Edinburgh

lucymontague@hotmail.co.uk

Abstract. This paper presents part of a PhD that explores the ways in which theories in urban design influence the process of urban design, and the extent to which they may inform design decisions. The focus of the paper is the empirical stage of the research; the execution of a site evaluation, urban design framework and masterplan design for Croydon in London, a commentary recording that process, and the subsequent analysis of it. Reflection on that process and product appears to indicate that theory’s influence in the creative process of urban design is distinctive but subservient to a variety of other influences. Apparently, the more conceptual and strategic the stage of design, the more extensive and explicit theory’s influence is. Conversely, the more spatial and detailed the stage of design, the more tacit and fragmented theory’s involvement seems to be. It is often implicit, embedded within the guiding principles that the individual designer exercises when generating and evaluating ideas, evidenced in the thought processes and decisions that are made.

Keywords. Reflection; urban; theory; design; analysis.

Introduction

This paper presents part of the research undertaken for a PhD by design, the interest of which is the role of urban design theory in the creative process of urban design. The focus of the paper is the empirical stage of the research; the process of design, commentary and analysis. In conclusion, some initial findings are considered.

Theory and urban design

Acting within the context of multiple constraints (site, budget, brief, clients, users, public policy and regulation) the urban designer is required to respond to various and sometimes conflicting interests in “...the symbolic attempt to express urban meaning in certain urban forms.” (Castells, 1983). In this complex situation some design decisions are determined by the inherited context however, when a decision cannot be determined this way the designer must make a judgment. These decisions may be made arbitrarily but it is more likely that the individual uses some form of criteria. A variety of sources including experience, education, episodic knowledge, currently accepted paradigms of the field, or theories in urban design may form the bases for criteria, and subscription to them may be explicit or implicit.

This paper discusses research that seeks to explore the ways in which theories in urban design might influence the creative process of urban design. Its objectives are to study existing theory related to design, examine the process of design and urban design, and relate knowledge of urban design theory to the design process. Since the design process and its evaluation are specific to the author they cannot be assumed to be generally applicable however they may act as indicators of trends in the relationship between theory and practice in urban design.

The reflective approach

Under this philosophy of research by design, a strategy based upon Donald Schön’s ‘The Reflective Practitioner’ (1983) has been developed. It consists of a literature review; appraisal of research by design methodologies (Montague, 2012); generation of an urban design by the author and an accompanying commentary; analysis of the commentary; reflection on the findings in the context of the literature review.

Design

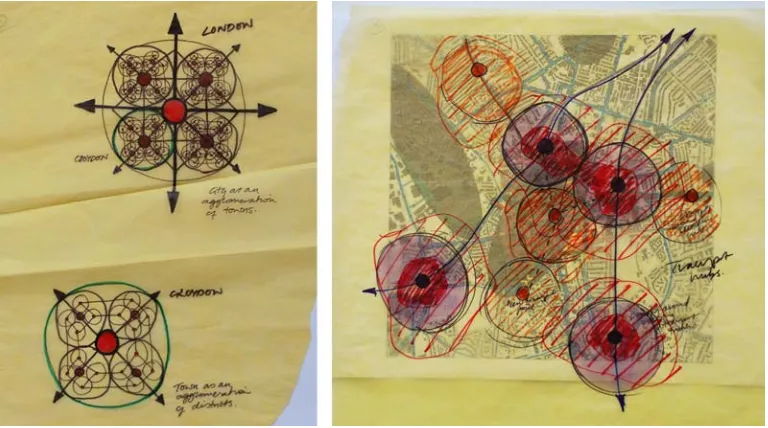

research includes standard outputs of urban design - a socio-economic, cultural and physical site evaluation, an urban design framework (see fig.1) and a masterplan proposal. After considering a range of options against established criteria, Croydon in Greater London was selected as the site for design.

Commentary

A commentary of the design process is kept to build an evidence base of design activity and making implicit behaviour explicit. This merely records the actions undertaken as the design progresses and the reasons for those actions, and is not analytical. It is what might be termed ‘descriptive reflection’ – “...a factual account of an event.” (Hatton and Smith, 1995, quoted in (Pedgley, 2007) or could viewed as an example of Schön’s reflection-in-action as it documents the designer’s reasoning when engaging directly with the design process (Schön, 1983).

This method of documenting design activity is thought by Pedgley (2007) to be a highly valuable and underused tool in the research work of individual designer/researchers. His review of approaches to documenting own design activity shows the keeping of a diary as a more suitable choice than action research or participant observation as these involve interaction with others which may not always be relevant or possible.

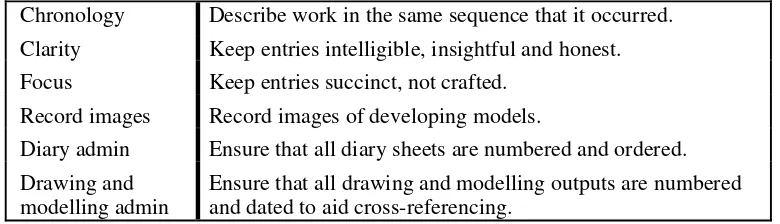

A commentary could be written concurrent with designing or retrospectively (Pedgley, 2007). The concurrent format is as close as possible to the act of designing as design is paused momentarily in order to make an entry. Pedgley’s experience of this approach led him to conclude that it is disruptive to the act of designing and his experience of daily entries was preferable, deemed to be “...neither too close to the activity so as to intrude upon it and reduce authenticity, nor so distant to risk excessive post-event rationalisation and misremembered information” (2007). Based on this evidence, entries for the design diary of this research were intially made on a daily basis. Commentary activity also endeavoured to conform to the criteria for good practice in design diary keeping shown in Table 1, based on Pedgley’s suggestions.

Chronology Describe work in the same sequence that it occurred.

Clarity Keep entries intelligible, insightful and honest. Focus Keep entries succinct, not crafted.

Record images Record images of developing models.

Diary admin Ensure that all diary sheets are numbered and ordered. Drawing and

modelling admin

Ensure that all drawing and modelling outputs are numbered and dated to aid cross-referencing.

Table 1

Criteria for good commentary practice

Figure 1

Excerpt from the design commentary

Analysis

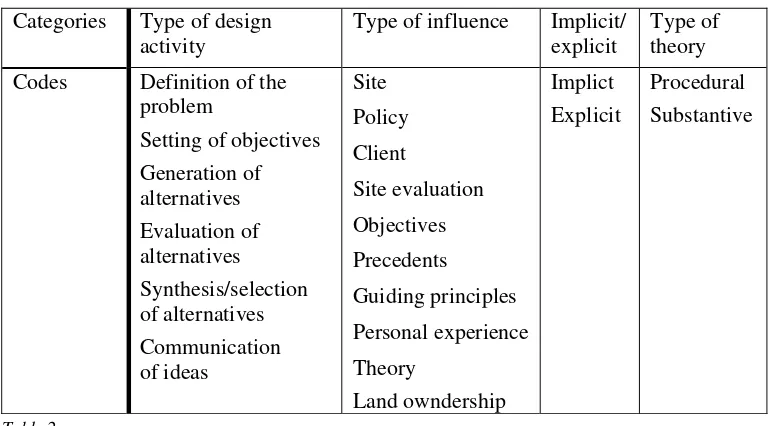

Having completed the commentary, it is important to assign attributes to each entry in order to process the large volume of raw data and start to understand what it showing (Pedgley, 2007, Gero, McNeill, 2006, Matthews, 2007). The following steps are taken to process the commentary in this work:

1. All sketches referenced in the diary are digitised so that they can be included in the research results. 2. The material is reviewed to see if any critical steps in the design have been erroneously omitted.

Additionally, any off-topic entries are purged.

3. Individual entries are classified using codes informed by the findings of the literature review. 4. Shorthand, abbreviations and acronyms are expanded.

5. The activity is analysed chronologically and by category to find relevant phenomena and pick out any trends.

The classification of each commentary entry is done in several ways (see Table 2). Four categories are determined by the different aspects of the research objectives, in line with the literature review: the type of design activity; the type of influence acting upon it; whether this influence is explicit or implicit; and, where theory appears to have been an influence, what type of theory.

Categories Type of design

Within each of these categories, codes are established according to the findings of the literature review. For example, the review of literature pertaining to the design process showed that although a range of models and representations exist (generic as well as specific to urban design), and despite variations in terminology, essentially the underlying stages and activities which are defined remain the same (Moughtin, 1999; Punter, 1997; Cowan, 2003; Lawson, 2006; Lang, 2005). These are drawn out and used as the codes for describing what type of design activity is taking place in each commentary entry (see Table 3). These classifications are intended to show where and how theory may have been an influence, tacitly or otherwise.

Initial Findings

influences. Crucially, it is limited by and subservient to constraints such as site, brief, and policy. These appear to inform the design with greater frequency.

Seemingly, the more conceptual and strategic the stage of design, the more extensive and explicit theory’s influence is. In the example shown in figures 2 and 3, theory, in the form of Peter Calthorpe’s ‘Transport Oriented Development’ (1993) is consciously deployed as a device which provides clear strategic guidance which responds to the diagnosed problems as well as the designer and client’s objectives.

Figure 2

Excerpt from the commentary analysis

Figure 3

Sketches relating to commentary entries 2.15 and 2.16

of Great American Cities’ (Jacobs, 1962), ‘Responsive Environments’ (Bentley, 1985) and ‘Cities for People’ (Gehl, 2010).

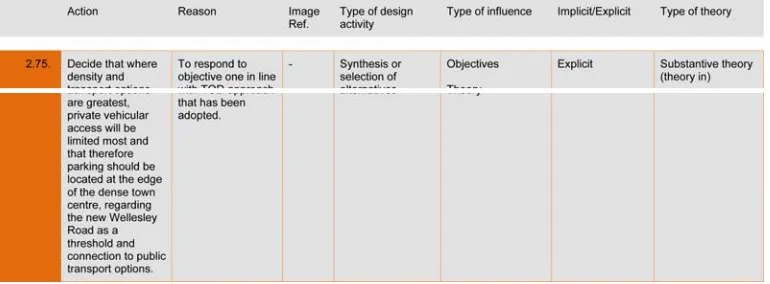

Figure 4

Excerpt from the commentary analysis

Although in some instances theory appears to provide direct guidance, other occurrences appear to show the extrapolation of a theory’s principles to inform decisions about specific situation in hand, as the evidence in figure 5 suggests. Here, the adopted strategy of Transport Oriented Development is interpreted when trying to make a decision about the level of car parking provision which should be incorporated.

Figure 5

Excerpt from the commentary analysis

Conclusion

There appear to be three initial, substantive findings, all of which might reasonably have been predicted prior to the research. In addition, at this stage, there is one main outcome in relation to the working process.

The methodological approach appears to have provided sufficient and credible evidence of theory’s role in urban design’s creative process and product. As anticipated by Pedgley (2007), maintenance of the commentary was unvoidably disruptive to designing. The indended daily entries were sometimes made less frequently whilst at other times were made several times a day. However, provided the recording of material (sketches, models and commentary) is rigorously administered, it seems capable of making design activity, including tacit aspects, transparent and communicable.

References

Bentley, I. (1985) Responsive environments: a manual for designers. London, Architectural.

Calthorpe, P. (1993) The next American metropolis: ecology, community, and the American dream. New York, Princeton Architectural Press.

Cowan, R. (2003) The Dictionary of urbanism. Tisbury, Streetwise Press. Flavell, R. (2001) PhD thesis, Edinburgh College of Art.

Gehl, J. (2010) Cities for people. Washington, Island Press.

Gero, J. & McNeill, T. (2006) An Approach to the Analysis of Design Protocols. Design Studies, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 21-61. Jacobs, J. (1962) The death and life of great American cities. London, Jonathan Cape.

Lang, J.T. (2005) Urban design: a typology of procedures and products. Oxford, Elsevier/Architectural Press.

Lawson, B. (2006) How designers think: the design process demystified. 4th ed. Oxford ; Burlington, MA, Elsevier/Architectural. Matthews, B. (2007) Locating design phenomena: a methodological excursion. Design Studies, vol. 28, pp. 369-385.

Montague, L. (2012) Urban Design Research Reflection. In: Newton, C. ed. Fragile International Student Conference Proceedings, April 2011, Brussels & Ghent, Belgium. Sint-Lucas School of Architecture, pp. 264-271.

Moughtin, C. (1999) Urban design: method and techniques. Oxford, Architectural Press.

Niedderer, K. & Roworth-Stokes, S. (2007) The Role and Use of Creative Practice in Research and its Contribution to Knowledge. In: International Association of Societies of Design Research, November 2007, Hong Kong. , pp. 1-18.

Pedgley, O. (2007) Capturing and Analysing Own Design Activity. Design Studies, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 463-483.

Punter, J. (1997) Urban Design Theory in Planning Practice: The British Perspective. Built Environment, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 263. Rust, C., Hawkins, S., Whiteley, G., Wilson & A, R.J. (2000) Knowledge and the Artefact. In: Proceeedings of Doctoral Education in Design Conference, July 2000, La Clusaz, France.