Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:06

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Examining Student Preferences of Group Work

Evaluation Approaches: Evidence From Business

Management Undergraduate Students

Terry H. Wagar & Wendy R. Carroll

To cite this article: Terry H. Wagar & Wendy R. Carroll (2012) Examining Student

Preferences of Group Work Evaluation Approaches: Evidence From Business Management Undergraduate Students, Journal of Education for Business, 87:6, 358-362, DOI:

10.1080/08832323.2011.628345

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.628345

Published online: 30 Aug 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 185

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.628345

Examining Student Preferences of Group Work

Evaluation Approaches: Evidence From Business

Management Undergraduate Students

Terry H. Wagar

Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Wendy R. Carroll

University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada

Although there has been increased research attention on the development of peer evaluation instruments, there has been less emphasis on understanding student preferences for specific peer evaluation approaches. The authors used data from a study conducted with undergraduate students in management courses to examine student preferences of group work evaluation approaches and their perceptions about fairness, workload, and due process for each approach. The findings suggest that students prefer a confidential questionnaire to conduct peer evalua-tions and perceive it to be the fairest approach, although also reducing concerns for evaluating shared workload. However, there was evidence that student perceptions of due process in approaches without an instructor’s involvement were lower.

Keywords: due process, fairness, peer assessments, peer evaluation, groups, undergraduate, workload

Despite a growing literature about the use of peer eval-uations in business school education, much less research has been conducted examining student preferences among different peer evaluation approaches and associated percep-tions about outcomes such as due process. Research about group work in higher education has focused on areas such as working effectively as a team (Willcoxson, 2006), mo-tivating team members (Fellenz, 2006), examining validity and reliability of peer evaluations (Baker, 2008; Clark, 1989; Morahan-Martin, 1996), and understanding factors influenc-ing peer evaluation outcomes such as location (Dommeyer, 2006) and race (Ghorpa & Lackritz, 2001). The use of peer evaluations has been implemented by faculty to address chal-lenges of fairness relating to individual contribution of work to projects (Fellenz, 2006; Mathews, 1994) and group mem-ber behaviors of social loafing (Aggarwal & O’Brien, 2008) and free riding (Brooks & Ammons, 2003).

Correspondence should be addressed to Wendy R. Carroll, University of Prince Edward Island, School of Business, 550 University Avenue, Charlot-tetown, Prince Edward Island C1A 4P3, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]

Although research attention has helped to strengthen de-sign features of group work and peer evaluation instruments, less has been done to understand student preferences and perceptions about approaches to group work evaluation. One study by Chen and Lou (2004) using an experimental design examined student motivation to participate in the peer eval-uation process and found that grade assignment and conflict reduction were two of the most important outcomes for stu-dents. Chen and Lou’s findings provide important guidance for further developing our understanding of student percep-tions of the peer evaluation approach.

In the present article we discuss the findings from a study conducted with senior-level university students in an indus-trial relations management course. Students participated in a group collective bargaining project that required the teams to prepare for and participate in a negotiation simulation, and produce a written report. The purpose of this study was to ex-amine student preferences among a variety of different peer evaluation approaches and then examine the associations be-tween different peer evaluation approaches and related out-comes such as due process. In this article, we provide a brief overview of the literature about peer evaluation and assess-ment, followed by a presentation of the methodology and

STUDENT PREFERENCES OF PEER EVALUATION 359

findings from the study. Finally, we discuss the implications of these findings for the application of peer evaluations in management education courses and considerations for future research directions.

EVALUATING GROUP WORK

Group Work in Business Education

Group work in management education has become a famil-iar design feature of courses, aimed at enhancing collabo-rative learning (Gueldenzoph & May, 2002; Topping, 2005) and developing student skills for the workplace (Aggarwal & O’Brien, 2008; Humphreys & Greenan, 1997). Creating teams to complete course work components facilitates peer learning (Gueldenzoph & May, 2002; Topping, 2005, 2009) and simulates an opportunity for students to develop man-agement skills such as leadership and teamwork (Gammie & Matson, 2007). Although these objectives are possible to achieve in course settings, there are differences between the classroom and the organizational environment (i.e., culture, length of time, and structure) that influence the success of the teams. These differences contribute to challenges in the process and assessment of group performance.

The benefits of peer and collaborative learning have been known for some time (Topping, 2009). Studies about group work in business education point to these benefits as well. For example, Aggarwal and O’Brien (2008) found that working in project teams exposes students to real-world work situa-tions, leads to higher level learning outcomes, creates more opportunities for critical thinking and responding to critical feedback from fellow group members, and advances student achievement. In addition, students working in teams may interact with students from different backgrounds, life expe-riences, and cultures. Teams need to work cooperatively to solve problems and, in addition to increasing their knowl-edge, students may enhance their presentation, writing, and conflict resolution skills. A group project can provide stu-dents with the chance to undertake a project that is larger in scope and more demanding than an individual assignment, thereby increasing the learning opportunity and outcomes.

Student Preferences and Perceptions

Although the use of group work in management education has become common practice, faculty and students struggle with issues relating to working effectively in groups (Will-coxson, 2006) and evaluating fairly student contributions to the work produced (Aggarwal & O’Brien, 2008; Brooks & Ammons, 2003; Fellenz, 2006; Mathews, 1994). Assessing and evaluating individual contribution is a challenging issue in group projects. An alternative to giving the same grade to all members of a group is to provide some opportunity for peer assessment. In most instances, group members are in a much better position than the professor to assess contribu-tions to the group project because a lot of the group effort

may be away from the classroom and thus the professor may only observe a small portion of the total work undertaken by the group. In addition to potentially addressing the free rider and social loafer problems, the presence of a peer eval-uation puts team members on notice that their performance will be assessed by their peers and may encourage potential free-riders to participate in the group activities (as a result of the impact of nonparticipation on their final grade; Brooks & Ammons, 2003; Waller, 1996).

Although group projects may simply focus on the end product such as the group paper and presentation, Baker (2008) noted that considerable information about specific task and relationship behaviors is lost. For example, did each member participate fully in the process of research and idea generation and did each member show up for meetings, help the team meet deadlines, and work well with others? In an effort to obtain input about individual member contributions, some form of peer assessment is frequently used. Although it has been questioned whether students should be in the po-sition to affect the grades of their peers, but it has also been argued that team members are in a better position than the in-structor to assess member contributions because of the nature of the interactions and experience of team work (Guelden-zoph & May, 2002). To facilitate the peer evaluation pro-cess, instructors have used a variety of assessments including (a) rating scales where students are asked to rate their peers on a number of factors such as quality of work, meeting dead-lines, and managing group conflict (Baker, 2008; Paswan & Gollakota, 2004); (b) allocation of points reflecting overall contribution to the group; (c) member rankings (either on overall contribution or selected dimensions); and (d) project diaries (Dommeyer, 2007) or learning logs (Ballantine & Larres, 2007).

Few studies have focused on examining student percep-tions of peer evaluation with the exception of Chen and Lou’s (2004). The findings from Chen and Lou’s study revealed that students found peer evaluations useful to provide grades for group members. In addition, the students’ perceptions of re-ducing conflict resolution and determining workload were increased with the use of peer evaluations. Although there have been studies examining student perceptions of individ-ual peer evaluation approaches, there has been no research, to our knowledge, focused on examining a student’s pref-erence among a variety of peer evaluation approaches. In our study, we further our understanding about student per-ceptions of peer evaluations by asking students about their preference for different forms of administering peer evalua-tions and their percepevalua-tions of fairness, workload sharing, and due process for each type.

METHOD

The data for this study come from a survey administered to students enrolled in senior-level industrial relation courses

in a business school undergraduate program. The survey was administered over several semesters and includes 15 differ-ence sections of the course. In teams of 4–5 students repre-senting either union or management, students in the courses completed a major collective bargaining project worth 25% of their grade. Students were randomly assigned to one side of the negotiation team by drawing a piece of paper from a hat that indicated the team side (union or management) and negotiation simulation number (collective bargaining simu-lation 1, 2, 3).

The students on each of the teams were required as part of the course to complete a peer evaluation using a confidential questionnaire to rate their contribution and that of their group members to the project. By way of example, if all students contributed equally to the project, each student would receive a score of 100, that is, 100% of the grade obtained in the project. A total of 546 students completed the peer evaluation. The students were then asked to complete a survey about their preferred peer evaluation approach, but participation in the survey was voluntary. Approximately 500 of the students who completed the peer evaluations completed the survey. In the survey, we asked students to consider four different eval-uation alternatives and provide their preferences for the four alternatives. These alternatives were described to students as the following:

1. Everyone gets the same grade: The instructor, prior to the start of the group exercise, states that every group member will receive the same grade for the project (that is, an equal allocation of points).

2. Group allocation of grades: The instructor indicates that once the project is completed, it is up to the group to decide how the points should be allocated. In other words, the group should meet and submit to the in-structor the allocation decided on by the group. 3. Confidential questionnaire: The instructor states that

each student must complete a confidential question-naire rating the contribution of every other group mem-ber. An individual’s overall contribution will be deter-mined by averaging the points allocated to each group member.

4. Meeting with professor: The instructor indicates that after the project is completed, the group meets with the instructor and each individual must rate the other group members and explain or justify his or her allocation of points. All members of the group will be allowed to address comments made by the other group members but the instructor will make the final decision regarding allocation of points.

For each of the four approaches, we also asked participants to indicate their perceptions of the fairness of the approach using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very un-fair) to 7 (very fair), their concern that other students would not share the workload in a responsible manner using a

7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not very concerned) to 7 (very concerned), and perceptions of due process us-ing a 7-point Likert-type scale rangus-ing from 1 (definitely no violation) to 7 (definitely a violation of due process).

RESULTS

About 47% of the respondents were male and the average age of participants was slightly less than 25 years, and about 16% of the participants were 30 years of age or older. Most of the students (approximately 78%) were in their third or fourth year of the business administration program and about 74% were working on a full- or part-time basis. Of those working, 63% indicated that they worked in groups while on the job.

When completing the individual confidential question-naire for their actual course assignment, about 58% of stu-dents opted for an equal allocation, that is, they gave every person in their group a score of 100%, although 42% had an unequal allocation. In terms of their own rating, 8% gave themselves a rating of less than 100%, 65% gave a score of 100%, and 27% gave themselves a higher rating (greater than 100). Most students were relatively satisfied with their group (average score of 5.76 on a 7-point scale).

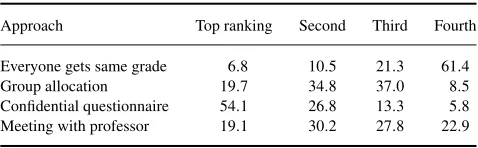

Students were asked to rank the four approaches to peer evaluation outlined previously with 1 being the top ranking and 4 representing the lowest ranking. These results are pro-vided in Table 1. Overall, there was a preference for the use of a confidential questionnaire, with 54% of students ranking this approach as number 1 and just under 27% ranking it sec-ond. In addition, less than 7% of students ranked “everyone gets the same grade” as number 1 and less than 11% ranked it second. Overall, there was a clear preference for the use of a confidential questionnaire.

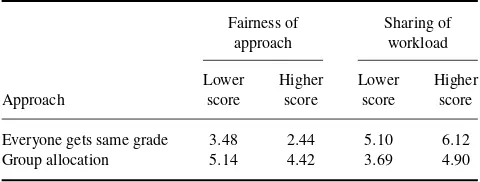

For the questions about the fairness of the approach and concern for sharing the workload in a responsible manner, the results for these two questions are provided in Table 2. In terms of the fairness of the approach, everyone receiving the same grade had the lowest average score although the use of a confidential questionnaire was perceived as the fairest approach with a mean score of 5.10 (above the scale midpoint but still almost two points away from a maximum score of 7). About 15% of participants viewed the use of a confidential questionnaire as unfair (as measured by a score of 3 or less) and 13% were neutral (score of 4). Just over 18% of students gave the approach a maximum score of 7.

TABLE 1

Ranking of the Four Approaches (%)

Approach Top ranking Second Third Fourth

Everyone gets same grade 6.8 10.5 21.3 61.4 Group allocation 19.7 34.8 37.0 8.5 Confidential questionnaire 54.1 26.8 13.3 5.8 Meeting with professor 19.1 30.2 27.8 22.9

STUDENT PREFERENCES OF PEER EVALUATION 361

TABLE 2

Perceptions Relating to Fairness and Workload

Fairness of

Note.For fairness of approach, responses were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very unfair) to 7 (very fair). For sharing of workload, responses were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not very concerned) to 7 (very concerned).

Students were also asked about their perceptions of due process. Two of the approaches (the use of a confidential questionnaire and meeting with professor) may be viewed as a violation of procedural justice measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely no violation) to 7 (definitely a violation of due process. When considering the approach in which the professor meets with the group and then decides the allocation, the average score was 2.88 (indi-cating moderate concern about the violation of due process). With reference to the use of a confidential questionnaire, the mean score was 4.41, indicating some concern about due pro-cess. In other words, students indicated more of a concern for due process when the instructor was not involved in the process.

For the most part, demographic characteristics were not significantly related to the ranking of the four approaches or the perceptions of fairness and workload. Students who opted for an equal allocation in the initial process were more likely to support the approach of giving everyone the same grade relative to those favoring an unequal allocation. The average score on the question addressing the fairness of giv-ing everyone he same grade was 3.12 (out of a maximum of 7) for students giving an equal allocation of points and 2.75 for students who did not give an equal allocation. Thet-test was significant atp<.05.

When considering both the first and second approaches (giving everyone the same grade or having the group de-cide), Table 3 reveals that students who gave themselves a score of less than 100 were more likely to perceive that the approach was fair (t-test significant atp<.01) and less likely

to be concerned that the workload would not be shared in a responsible manner (p<.01) although those who gave

them-selves a score above 100 were more likely to perceive that the approach was unfair (p<.05) and express greater concern

about the sharing of work (p<.01).

In summary, the findings from our study suggest that stu-dents prefer a confidential questionnaire to evaluate their peers when working on group projects. This finding is con-sistent with evidence from industry settings where it has

been found that employees prefer anonymity when conduct-ing evaluations of their peers (Bamberger, Erev, Kimmel, & Tali, 2005). Compared to the other three approaches outlined in the survey, the confidential questionnaire allowed students to evaluate each member of the team without being identi-fied. It is also not surprising that students do not advocate an approach where all students get the same grade, regardless of effort, given that one of the major concerns of students about group work is the uneven distribution of workload. Overall, students perceive the confidential questionnaire to be the fairest of the four approaches and the best mechanism for addressing issues related to contribution by each of the members.

IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

It is interesting to note that although students preferred the confidential questionnaire to evaluate team members, they were more concerned about due process when an in-structor was not involved. This concern about due process may suggest that students recognize issues of rater biases such as leniency of friends rating friends and sabotage by those competitive for marks. Although students indicated the confidential questionnaire as their first preference, the group allocation and meeting with the instructor approach received approximately the same percentage in the rankings. As such, students selected approaches based on perceptions of fairness and workload sharing, but not driven by due process.

There are a number of strengths and limitations to this research that must be taken into consideration when inter-preting the results of the studies. A strength of this study was the use of a field design using an actual task performed by students for evaluation in a course of study. However, it must also be recognized that the data collected for this study were from a single university in a specific region. Conducting this research in a broader context, including national and inter-national settings, will enhance the findings and inform the literature in this area more fully.

TABLE 3

Lower and Higher Allocation and Perceptions of Fairness and Workload

Approach score score score score

Everyone gets same grade 3.48 2.44 5.10 6.12 Group allocation 5.14 4.42 3.69 4.90

Note.For the lower score, students gave themselves a score of less than 100. For the higher score, students gave themselves a score of greater than 100.

Although we did not hypothesize about specific differ-ences in demographics, it is interesting to note that female students showed more of a preference for a confidential ap-proach to peer evaluations than their male counterparts. There was some moderate evidence (p < .05) that women were

more likely to prefer the use of a confidential questionnaire although preference for working in a group was positively associated with perceptions of fairness when considering having the group allocate points, the use of a confidential questionnaire, and having the allocation determined by the professor. This finding lends to future researchers examining differences between male and female students in the peer evaluation process and associations with various outcomes.

From an instructor perspective, the findings from this study have a number of implications. With the increased integration of group work in business curriculum it is im-portant for instructors to focus not only on the design of the peer evaluation instrument but also student preferences to approach taken to peer evaluations. The findings from this study suggest that instructors should consider implementing peer evaluations in such a way that confidentiality is provided for the ratee and rater. In addition, the findings also suggest that student perceptions of due process increase with instruc-tor involvement. Students rated the approach of all members of the group receiving the same grade as the lowest suggest-ing that differentiation among student contributions to project work is important. Designing a peer evaluation approach that considers confidentiality and instructor involvement will en-hance student perceptions of fairness.

CONCLUSION

This study provides interesting insights about student pref-erences when conducting peer evaluations for group work projects. Given the prevalence of group work in business pro-grams, it is important to develop a process that students per-ceive as fair. Although students prefer their feedback about group members to be confidential, other techniques that en-hance the quality of the feedback should be considered to help students become more confident to share ratings. Stu-dent experiences with peer evaluation processes may have future implications as they progress into the workplace and receive and conduct evaluations on peers and subordinates. Establishing approaches and processes in business programs to support this transition is important from an educational and practical perspective.

REFERENCES

Aggarwal, P., & O’Brien, C. L. (2008). Social loafing on group projects.

Journal of Marketing Education,30, 255–264.

Baker, D. F. (2008). Peer assessment in small groups: A comparison of methods.Journal of Management Education,32, 183–209.

Ballantine, J., & Larres, P. M. (2007). Final year accounting undergraduates’ attitudes to group assessment and the role of learning logs.Accounting Education,16, 163–183.

Bamberger, P. A., Erev, I., Kimmel, M., & Tali, O.-C. (2005). Peer as-sessment, individual performance, and contribution to group processes: The impact of rater anonymity.Group & Organization Management,30, 344–377.

Brooks, C. M., & Ammons, J. L. (2003). Free riding in group projects and the effects of timing, frequency, and specificity of criteria in peer assessments.Journal of Education for Business,78, 268–272.

Chen, Y., & Lou, H. (2004). Students’ perceptions of peer evaluation: An expectancy perspective.Journal of Education for Business,79, 275–282. Clark, G. L. (1989). Peer evaluations: An empirical test of their validity and

reliability.Journal of Marketing Education,11, 41.

Dommeyer, C. J. (2006). The effect of evaluation location on peer evalua-tions.Journal of Education for Business,82, 21–26.

Dommeyer, C. J. (2007). Using the diary method to deal with social loafers on the group project: Its effects on peer evaluations, group behavior, and attitudes.Journal of Marketing Education,29, 175–188.

Fellenz, M. R. (2006). Toward fairness in assessing student groupwork: A protocol for peer evaluations of individual contributions.Journal of Management Education,30, 570–591.

Gammie, E., & Matson, M. (2007). Group assessment at final degree level: An evaluation.Accounting Education,16, 185–206.

Ghorpa, J., & Lackritz, J. R. (2001). Peer evaluation in the classroom: A check for sex and race/ethnicity effects.Journal of Education for Business,

76, 274–281.

Gueldenzoph, L. E., & May, G. L. (2002). Collaborative peer evaluation: Best practices for group member assessments.Business Communication Quarterly,65, 9–20.

Humphreys, P., & Greenan, K. (1997). Developing work-based transfer-able skills in a university environment.Journal of European Industrial Training,21, 63–69.

Mathews, B. P. (1994). Assessing individual contributions: Experience of peer evaluation in major group projects.British Journal of Educational Technology,25, 19–28.

Morahan-Martin, J. (1996). Should peers’ evaluations be used in class projects? Questions regarding reliability, leniency.Psychological Reports,

78, 1243–1250.

Paswan, A. K., & Gollakota, K. (2004). Dimensions of peer evaluation, overall satisfaction, and overall evaluation: An investigation in a group task environment.Journal of Education for Business,79, 225–231. Topping, K. J. (2005). Trends in peer learning.Educational Psychology,25,

631–645.

Topping, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment.Theory Into Practice,48, 20–27. doi:10.1080/00405840802577569

Waller, J. E. (1996). Social loafing and the group-evaluation effect: Effect of dissimilarity in a social-comparison.Psychological Reports,78, 177–178. Willcoxson, L. E. (2006). “It’s not fair!” Assessing the dynamics and re-sourcing of teamwork.Journal of Management Education,30, 798–808.