Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 18:54

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

College challenge to ensure “timely graduation”:

Understanding college students’ mindsets during

the financial crisis

Xiaoying Chen & Jasmine Yur-Austin

To cite this article: Xiaoying Chen & Jasmine Yur-Austin (2016) College challenge to ensure “timely graduation”: Understanding college students’ mindsets during the financial crisis, Journal of Education for Business, 91:1, 32-37, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1110106 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110106

Published online: 23 Nov 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 10

View related articles

College challenge to ensure

“

timely graduation

”

: Understanding college students

’

mindsets during the

fi

nancial crisis

Xiaoying Chen and Jasmine Yur-Austin

California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, California, USA

ABSTRACT

Since mid-2007, the United States has experienced the direst economic recession since the Great Depression. While considerable institutional resources have been spent on boosting 4-year graduation rates, many college students purposefully delayed graduation, waiting to enter the labor market until the overall economic situation had improved. The survey results suggested that students who were unemployed, who knew someone being laid off, who were pessimistic about the job market, or who targeted private industry jobs tended to stay in school longer. These results support the well-documented warehouse hypothesis: that students use schools as warehouses to shield themselves from the deteriorating job market.

KEYWORDS

education;financial crises; warehouse

Following the onset of the 2007–2009 financial crisis, many college students and parents began raising the worrying question of whether a college degree would really led to a good job matching the student’s educa-tional training. News of the rising naeduca-tional unemploy-ment rate and other poor economic conditions were fueling concern among college students, who were wor-ried aboutfinishing school and finding jobs. From May 2007 to August 2009, the national unemployment rate went from 4.5% to 9.7% (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). In particular, the hiring demand for recent college graduates was adversely affected more, in proportion, than the situation of currently employed workers. The research of Abel, Dietz, and Su (2014) indicated that the average unemployment rate among recent college gradu-ates (those 22–27 years old) was 4.3%, higher than the 2.9% rate for all college graduates (22–65 years old). Their study was conducted from 1990 through thefirst quarter of 2013. The gap between the two groups’yearly unemployment rates grew significantly around 2001 and again in 2007–2009, when the United States faced two different periods of recession.

Careers management is increasingly left up to the individual, as the focus of employment is more on the individual’s employability than on the organiza-tion’s responsibility to individuals (e.g., Clarke & Patrickson, 2008). Employability also depends on context, varying for example with supply and demand for labor (Clarke, 2008). According to the

warehouse hypothesis (e.g., Bozick, 2009), when eco-nomic conditions, which are typically assessed using unemployment rates, are favorable, young people are less likely to stay in school and more likely to go into the labor market. The opposite is true when economic conditions are not favorable. Schools thus function as warehouses, buffering students from unstable labor market conditions. In addition, many studies have indicated that initial entry into the labor market can have profound and persistent nega-tive effects on the development of a college gradu-ate’s career. Kahn (2010) and Oreopoulos, von Wachter, and Heisz (2012) showed that North American college graduates endured a lasting down-ward trend in earning power for up to ten years after graduating during a period of recession. Similar findings were reported for data sets from other nations, such as Austria (Brunner & Kuhn, 2010), Japan (Genda, Kondo, & Ohta, 2010), and Germany (Stevens, 2007). Vedder, Denhart, Denhart, Matgour-anis, and Robe (2010) reported that 38% of college graduates were underemployed in 2008. These grad-uates worked in low-paying, low-skill jobs, and did not use the education and training they had received in college. Similar findings were reported by Li, Mal-vin, and Simonson (2014), who found that most business majors experienced a wage penalty of between 4% and 14% because of overeducation. Given these prospects, it seems that college students

CONTACT Xiaoying Chen cindy.chen@csulb.edu California State University, Long Beach, Department of Finance, 1250 Bellflower Blvd., Long Beach, CA 90840, USA.

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC 2016, VOL. 91, NO. 1, 32–37

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110106

might indeed be better off waiting to enter the labor market until overall economic conditions improve.

While college students were intentionally delaying graduation, many institutions were directing substantial resources toward improving their four-year graduation rates. Some employed interventionist advising programs to achieve this goal. In the summer of 2009 President Obama, responding to the notion that college attainment was necessary for the United States to secure world eco-nomic leadership and improve intergenerational income disparity (Bernanke, 2008), introduced the American Graduation Initiative, calling for the college graduation rate to be raised to 60% by 2020, and for the United States to regain the position of having the highest pro-portion of people with college educations. As a result, considerable institutional resources were spent on boost-ing the graduation rate. California Governor Jerry Brown also set the goal of having each of California’s public uni-versities increase the proportion of students graduating by 10% within four years.

These divergent views motivated this study. If stu-dents’ interests are not aligned with institutions’ goals, these discussions of four-year college graduation rates could continue fruitlessly for years. We were interested in assessing whether and to what extent the deteriorating job market and the direfinancial crises, which were exac-erbated by the distressed auto industry, the bailouts of AIG, and rising home foreclosures, affected students’

own graduation decisions. We also explored the individ-ual factors that might differentiate students’ tendencies to warehousing. The information on students was classi-fied into three categories: (a) demographic and academic data, (b) experiences related to the worsening economic conditions, and (c) career plans. We believed that a thor-ough examination of students’ responses during a time of economic hardship and labor market uncertainty could provide important insights into the assistance col-leges and universities could offer to students during such periods.

Hypotheses

Demographic and academic data

Although we tested a variety of demographic and aca-demic variables, we expected gender, race, and grade point average (GPA) to be significantly related to the decision to delay work. For example, past research has suggested that in a depressed economy, men were more likely than women to delay working, and people of color were more likely than whites to do so (e.g., Rivkin, 1995). We also expected students with low GPAs to

worry more about finding jobs than students with high GPAs, and thus to delay graduation. Thus, we hypothe-sized the following:

Hypothesis 1(H1): Men would be more likely to delay graduation than women.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): People of color would be more likely to delay graduation than whites.

Hypothesis 3(H3): Students with low GPAs would be more likely to delay graduation than students with high GPAs.

Experience with worsening economic conditions

We examined four aspects of students’experiences with the worsening economic conditions and made specific hypotheses for each of them: (a) perception of the job market, (b) awareness of others’ job losses, (c) employ-ment status, and (d)financial obligations. Thus:

Hypothesis 4(H4): Students who are optimistic about job market would be less likely to delay graduation.

Hypothesis 5(H5): Students who know someone who has been laid off would be more likely to delay graduation than students who do not.

While the warehouse hypothesis assumed that work and school were mutually exclusive (see Bozick, 2009), many young people today work while attending school. Accordingly, we postulated that having a job would make a student less likely to change in their academic plans, and that such students would not need to delay graduation. Specifically, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Students who are currently employed would be less likely to delay graduation than would students who are not employed. We also expected that students withfinancial obliga-tions (operationalized as student loans) would delay graduation to avoid paying those loans back during the economic downturn. Specifically, we had the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7(H7): Students with student loans would be more likely to delay graduation than students without.

Career plans

Finally, we expected students who planned to work in private industry to feel more pressure than those plan-ning to work for the government, and would therefore be more likely to delay graduation in the hopes offinding more optimal work. However, we formed no specific hypothesis on this.

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS 33

Method

Participants, procedure, and measures

The data were collected from students in a business col-lege in a Southern California public university. The sur-vey method was adopted as our fundamental approach. Students were asked to rate the extent to which economic conditions might affect their decisions to postpone grad-uation, on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly increased) to 5 (strongly decreased). To show how the economy affected these attitudes, the same ques-tionnaires were distributed separately in both 2008 and 2012. Participation was voluntary and anonymity was assured.

Next, we explored the individual factors that could differentiate warehousing responses among students. First, we assessed each student’s perception of the job market with a question “How long will it take you to find a job?” Second, we determined the student’s employment status, their awareness of their ownfi nan-cial troubles and loan obligations, and any job losses among their friends. Third, we collected demographic data (including self-reported academic data, such as major and GPA). Finally, we asked about the student’s career choices.

Results

In spite of various governmental policies that had been implemented to reinvigorate the economy, students in 2012 were more concerned about job markets, and they thought it would take longer to find jobs. In 2008, 35.84% of our respondents expected to need three months or less to get a job offer after graduation, 31.74% expected 4–6 months, and 13.65% expected longer. In 2012, these numbers were 27.59%, 36.55%, and 20.00%, respectively. We rated these views from 1 (for 0–3 months) to 5 (for more than a year). The mean of the scale was 1.44 in 2008 and 1.72 in 2012. These two values are 95% significantly different according to a two-sample

t-test assuming unequal variances (as shown inTable 1). The survey also included the questions“Do you know someone who became unemployed in the last two years due to the worsening economy?” and “Have your employers adopted actions (freezing payments, cutting working hours, less bonus, etc.) due to the current econ-omy?” The data indicated that a significant number of students had felt the impact of the recession personally. In 2008, 71.33% in 2008 knew someone who had become unemployed; this was 80.00% in 2012. In 2008, 40.61% had suffered pay freezes, loss of hours, or reduced bonuses due to the economic situation; this was 33.79% in 2012.

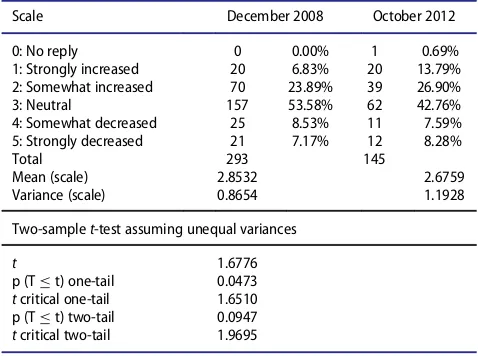

Overall, it was very possible that college students were choosing to be warehoused in schools in order to buffer themselves from the deteriorating job market and the economic recession. We asked students to rate the extent to extent to which economic conditions might affect their decision to postpone graduation on a 5-point Lik-ert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly increased) to 5 (strongly decreased). The responses are reported in Table 2. Responses of strongly increased grew from 6.83% to 13.79%. Somewhat increased changed only slightly (23.89% in 2008; 26.90% in 2012) and neutral dropped from 53.58% to 42.76%. Somewhat decreased and strongly decreased each stayed around 15 or 16%. The mean of the scale was 2.8532 in 2008 and 2.6759 in 2012. These two mean values are 95% significantly differ-ent from each other, suggesting that studdiffer-ents are indeed

Table 2.Delay to students’graduation plans: Responses to“How would you say the recent economy conditions have made you to delay your expected graduation date?”

Scale December 2008 October 2012

0: No reply 0 0.00% 1 0.69%

1: Strongly increased 20 6.83% 20 13.79% 2: Somewhat increased 70 23.89% 39 26.90%

3: Neutral 157 53.58% 62 42.76%

4: Somewhat decreased 25 8.53% 11 7.59% 5: Strongly decreased 21 7.17% 12 8.28%

Total 293 145

Mean (scale) 2.8532 2.6759

Variance (scale) 0.8654 1.1928

Two-samplet-test assuming unequal variances

t 1.6776

p (Tt) one-tail 0.0473 tcritical one-tail 1.6510 p (Tt) two-tail 0.0947 tcritical two-tail 1.9695

Table 1.Attitude about the job market: Responses to“How long will it take tofind a job?”

Scale December 2008 October 2012

0: No reply 55 18.77% 23 15.86%

Two-samplet-test assuming unequal variances

t ¡2.3956

p (Tt) one-tail 0.0087 tcritical one-tail 1.6509 p (Tt) two-tail 0.0173 tcritical two-tail 1.9694

more likely to delay their graduation due to the econ-omy. The warehousing concern was more extensive in 2012 than in 2008. It seemed then that after witnessing lingering negative effects of the depressed labor market from 2008 onward, more students were staying in school longer than they would have done otherwise.

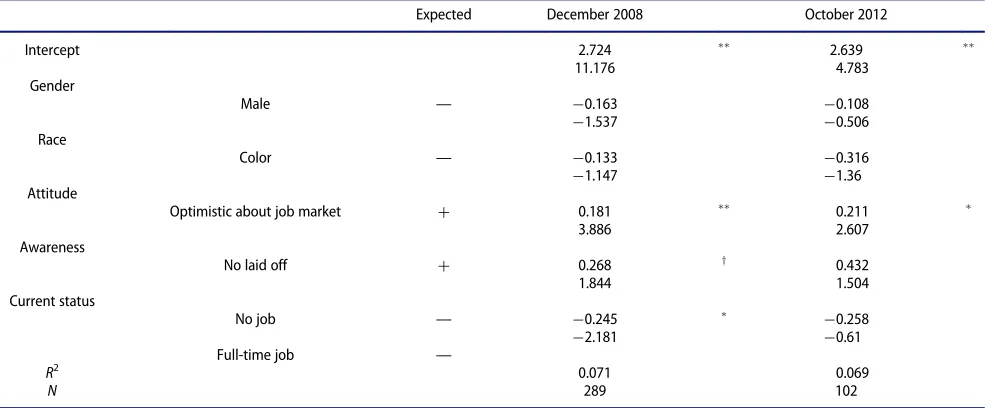

The multivariate analysis of warehousing is reported inTable 3. The dependent variable is the answer on the Likert-type scale to“How would you say the recent eco-nomic conditions have made you delay your expected graduate date?”with responses ranging from 1 (strongly increased) to 5 (strongly decreased). Therefore, a negative coefficient indicates a tendency to delay graduation, while a positive coefficient shows that a factor tends to mitigate the tendency to do so. Male is a dummy vari-able, 1 for male students and 0 for female students. Color is a dummy variable, 1 for non-White students and 0 for White. Job market is a Likert-scale variable ranging from 1 (a strong belief that it will take longer tofind a job) to 5 (a strong belief that it will take less time tofind a job). If the respondent did not know anyone who had been laid off recently, the unaware of anyone being laid off variable was 1 and was 0 otherwise. If the respondent had no job, full-time or part-time, the dummy variable no job was set to 1 and was 0 otherwise. If the student had a full-time job, the dummy variable full full-time job was 1 and was 0 otherwise.

We first considered our hypotheses about demo-graphic differences, including gender and race (H1 and

H2). Data released by the U.S. Department of Labor

(Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015) indicated the unem-ployment rate of women was lower than that of men: 6.8% of men were unemployed, versus 5.6% of women, in the fourth quarter of 2008. The unemployment rate was even more divergent in the second quarter of 2009: 10.2% for men and 7.9% for women. We expected that men were more likely than women to be warehoused and to delay their graduation dates and postpone their careers. However, our study did not find a connection between gender and warehousing.

We next examined the connections between race and warehousing. There was mixed support forH2, that peo-ple of color would be more likely to delay graduation. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (Bureau of Labor Statistics,2015), Blacks had lingering double-digit unemployment rates: 11.5% during the fourth quarter of 2008, 13.1% in the first quarter of 2009, and 13.78% in the fourth quarter of 2012. Rivkin (1995) didfind Blacks more likely to delay graduation than whites. The popula-tion of Blacks in the present study was too small to draw concrete conclusions but the evidence here supports Riv-kin’sfinding.

We next examined the relationship between ware-housing and personal experience with the recession (H4

and H5). Ourfindings strongly supportedH4: students who were pessimistic about the job market were more likely to postpone graduation. The results were robust between the 2008 and 2012 groups. Many of our respondents knew people who had been laid off, and this showed a tremendous influence on the decision to stay

Table 3.Influential factors to delay students’graduation plans.

Expected December 2008 October 2012

Intercept 2.724 2.639

11.176 4.783

Gender

Male — ¡0.163 ¡0.108

¡1.537 ¡0.506

Race

Color — ¡0.133 ¡0.316

¡1.147 ¡1.36

Attitude

Optimistic about job market C 0.181 0.211

3.886 2.607

Awareness

No laid off C 0.268 y 0.432

1.844 1.504

Current status

No job — ¡0.245

¡0.258

¡2.181 ¡0.61

Full-time job —

R2 0.071 0.069

N 289 102

Note.The dependent variable is the answer on the 5-point Likert-type scale to“How would you say the recent economic conditions have made you delay your expected graduate date?”with options ranging 1 (strongly increased) to 5 (strongly decreased). A negative coefficient indicates a tendency to delay graduation, while a positive coefficient shows that a factor tends to mitigate the tendency to do so.

ypD.1.

pD.05.pD.01.

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS 35

in school longer. As we expected, people who knew per-sonally about job losses were more likely to be ware-housed in 2008. The same association was found in 2012, but the coefficient was not statistically significant.

More than two-thirds of our respondents were employed at the time of the survey. Employed students may be better informed about marketable skills in the depressed job market. In 2008, students’job statuses sig-nificantly affected their choices of warehousing (H6). The coefficient was¡0.245, which is statistically signifi -cant. Our survey suggested that unemployed students were more likely to delay graduation; schools worked as warehouses for shielding inexperienced students from the unfavorable job market. Liu, Salvanes, and Sørensen (2012) suggested that college students entering the labor market during a recession tended to feel a persistent neg-ative impact on their career advancement. This became more evident when their skills mismatched the demands of the hiring industries.

Due to mutilcollinearity, with many individual varia-bles being highly correlated, we chose to present some hypothesized factors in the multiple regression model (Table 3) but to test others individually. For example, we speculated that students with loan obligations would be more likely to delay graduation (H7), as this lets them defer payments, but we didn’tfind consistent and robust evidence for this. We also found no evidence supporting

H3, that GPA was a factor in warehousing decisions. We also found no significant associations between the extent of warehousing and family income or age, on which we had not formed specific hypotheses. We exam-ined the connections between warehousing and business majors, expecting that the currently tarnished image of the finance graduate (given the financial crisis) might lead finance students to stay in school, but we did not find evidence of this.

Subgroup analysis

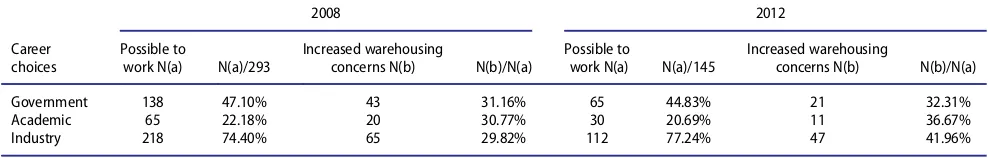

Last, we explored connections between career plans and warehousing. Students rated their likelihood of working in specificfields after college. The fields we considered were government, academia, and industry (seeTable 4). Industry includes a number offields educated in business

schools, such as information systems,financial activities, management services, and other professional services. Students also rated their interest in each area.

In 2008, 138 respondents thought they might work in government after graduation, perhaps because govern-ment jobs had the lowest unemploygovern-ment rates (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). Two hundred eighteen stu-dents chose to work in industry and 65 in academia. In 2012, 65 respondents were interested in government, 112 in industry, 30 in academia. Interestingly, the balance among these choices was similar in 2008 and 2012 (47.10% vs. 44.83%, 22.18% vs. 20.69%, 74.40% vs. 77.24%, respectively). Students could express interest in multiple fields, meaning each total is greater than the number of respondents.

We focused on students’ likelihood of working in a specific field and tallied their views on the extent to which economic conditions might affect their postpon-ing graduation, from 1 (strongly increased) to 5 (strongly decreased). For example, we found that 43 of the 138 stu-dents (31.16%) who were interested in government jobs had either strongly or somewhat increased their chances of warehousing—that is, were considering timing the job market and postponing their graduation. This was 30.77% for the academia group and 29.82% for the industry group. In 2012, students of all career preferen-ces tended to stay in school longer. In the industry group, in particular, 41.96% were now concerned enough to postpone graduation, an increase of more than a third.

Conclusion

This study provided new evidence in support of the warehouse hypothesis (see Bozick, 2009), which holds that young people are more likely to stay in school when the unemployment rate is high and jobs are scarce. In particular, we sought to highlight the personal factors that shaped students’ perceptions of the overall sound-ness of the economy and accordingly affected their grad-uation plans. We investigated students’ demographic and academic data, their experiences with the worsening economic conditions, and their career plans. The 2008 and 2012 surveys offer snapshots of students’ decisions

Table 4.Career choices and students’reported response to worsening economic conditions.

2008 2012

Government 138 47.10% 43 31.16% 65 44.83% 21 32.31%

Academic 65 22.18% 20 30.77% 30 20.69% 11 36.67%

Industry 218 74.40% 65 29.82% 112 77.24% 47 41.96%

about staying in school at two distinct points in the financial crisis.

We found that between 2008 and 2012, more full-time and experienced employees went back to school. Even though the recession officially ended in 2009, household finances hadn’t fully recovered by 2012. Family income dropped dramatically from 2008 until 2012, and as a consequence more students took loans, and they bor-rowed more money. In 2008, 28.33% of respondents had student loans; in 2012, 47.59% did. In 2008, about 20% of student loans were greater than $20,000; in 2012, 30% were. We collected data directly related to students’ per-ceptions of the job market. Students in 2012 were more concerned about job markets, and they believed that it would take longer to find jobs. When students were asked to rate the extent to which the economic condi-tions might affect their decision to postpone graduation, the warehousing concern turned out to be more preva-lent in 2012 than in 2008. After witnessing lingering neg-ative effects in the labor market from 2008 onward, more students were trying to stay in school longer.

Schools work as warehouses to shield students from the unfavorable job market. Our results suggested that unemployed students were more likely to delay gradua-tion. Knowing someone who had been laid off also gave students an incentive to stay in school longer. Similar responses were observed among students who expected it to take a long time to find jobs. Male students, non-Whites, seniors, and low-GPA students did not demon-strate more significant warehouse effects. Students who planned to work in private industry might have felt more pressure than others and been more likely to delay grad-uation in the hope offinding better work.

Our study is subject to certain limitations. First, we surveyed only students from the College of Business Administration; other students’ opinions are not repre-sented. Second, career choices were limited to three job sectors; future research should investigate more specific industry categories. Third, the survey we employed did not allow open comments, which may have caused us to omit valuable suggestions from students. We nonetheless anticipate that this survey will facilitate a conversation between students, administrators, and faculty members during the most challenging economic crisis since the Great Depression.

References

Abel, R., Deitz, R., & Su, Y. (2014). Are recent college graduates

finding good jobs?Current Issues in Economics and Finance,

20, 1–8.

Bernanke, B. (2008, June 4).Remarks on Class Day 2008. Har-vard University. Retrieved from http://www.federalreserve. gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20080604a.htm

Bozick, R. (2009). Job opportunities, economic resources, and the postsecondary destinations of American youth. Demog-raphy,46, 493–512.

Brunner, B., & Kuhn, A. (2010). The impact of labor market entry conditions on initial job assignment, human capital accumulation, and wages. University of Zurich Institute for Empirical Research in Economics Working Paper, No. 520. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015). Labor force statistics from

the current population survey. Retrieved from http://data. bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000

Clarke, M. (2008). Understanding and managing employability in changing career contexts.Journal of European Industrial Training,32, 258–284.

Clarke, M., & Patrickson, M. (2008). The new covenant of employability.Employee Relations,30, 121–141.

Genda, Y., Kondo, A., & Ohta, S. (2010). Long-term effects of a recession at labor market entry in Japan and the United States.Journal of Human Resources,45, 157–196.

Kahn, L. (2010). The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy.Labor Econom-ics,17, 303–306.

Li, I., Malvin, M. & Simonson, R. (2014). Overeducation and mismatch: Wage penalties for college degrees in business.

Journal of Education for Business,90, 119–125.

Liu, K., Salvanes, K., & Sørensen, E. (2012, August).Good skills in bad times: Cyclical skill mismatch and the long-term effects of graduating in a recession. Discussion Paper at NHH Norwegian School of Economics. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp6820.pdf

Oreopoulos, P., von Wachter, T., & Andrew, H. (2012). The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a reces-sion.American Economic Journal: Applied Economics,4, 1– 29.

Rivkin, S. G. (1995). Black/white differences in schooling and employment.Journal of Human Resources,30, 826–852. Stevens, K. (2007). Adult labour market outcomes: the role of

economic conditions at entry into the labour market.

Retrieved from http://www.iza.org/conference_files/ SUMS2007/stevens_k3362.pdf.

Vedder, R., Denhart, C., Denhart, M., Matgouranis, C., & Robe, J. (2010, December). From Wall Street to Wal-Mart: Why college graduates are not getting good jobs.Center for Col-lege Affordability and Productivity. Retrieved from http:// centerforcollegeaffordability.org/research/studies/from-wall-street-to-wal-mart.

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS 37