IN

H

UMAN

R

ESOURCE

M

ANAGEMENT

E

NVIRONMENTS WITH A

U

NION

P

RESENCE

TIMOTHYBARTRAM* ANDCHRISTINACREGAN**

T

his paper investigates consultative management–union relations in organisations that are characterised by human resource management practices. It presents the findings of a preliminary analysis of the data. Two large organisations are examined, one the subsidiary of a multinational, and the other a public hospital. The findings demonstrate that there are two criteria for the possibility of mutual gain. These consist of, first, an appreciation by management of the collective loyalties of workers and, second, the achievement of real gains for employees arising from their constraint in the use of collectively bargained procedures and industrial action.INTRODUCTION

This paper seeks to determine the circumstances in which consultative management-union relations in the ‘high performance’ workplace might benefit both parties.

From an employment relations stance, consultation can be defined as management–employee communication that occurs outside the frame of collective bargaining (see Brown & Ainsworth 2000, for a review of consultation in Australia in the 1980s and 1990s). It can take many forms, ranging from formal joint consultation schemes (JCCs), with regular meetings and written procedures, to ad hoc, informal arrangements (Ben-Avner & Jones 1995). In their formal guise, consultative practices have a long pedigree and have entered the armoury of human resource management (HRM) in the form of participation or employee involvement (EI).

The investigation was carried out by a comparison of two large, unionised enterprises, situated in Victoria, that employed HRM techniques in a climate of workplace change. These findings represent the results of the first analysis of

case study data that were collected in Victoria over the last five years as part of a wider, large-scale project.1One study took place in a multinational enterprise in 1997–8 and 2002, and the other in a public sector firm over the period 1999–2000.

The paper is organised as follows. There is a brief literature review from which predictions are derived regarding factors that might bring about joint gain. This is followed by the empirical work. Finally, the results are discussed.

CONSULTATION: A POSITIVE-SUM GAME?

In an effectively unionised organisation that is faced with the challenge of competitive pressures, management has the problem of introducing changes that strike at the heart of collectivism: issues of flexibility include skill definitions, job controls, work intensification, wage rates and job loss. In the past, these have often been dealt with by collective bargaining with its inherent threat of industrial action. In the new employment relationship, characterised as HRM, management’s aim is to introduce flexibility yet avoid industrial conflict. There is ample evidence to demonstrate that, where there is an effective union presence, management often consults with unions to achieve this end (McInnes 1985; Ramsey 1993; Ackers et al. 1992; Brown & Ainsworth 2000). While thorough statistical analyses of consultation in Australian workplaces have been carried out (Marchington 1992a,b) there is little case study material, so, following Lansbury and Davis (1992) and Davis and Lansbury (1996), such an approach is undertaken in this paper.

There is a major stream of industrial relations literature that suggests that unions reap little benefit from consultation. In his classic study, Ramsay (1977) argued that, while the objective of labour is ‘the primacy of democracy itself’, participation is a unitarist device ‘best understood as a means of attempting to secure labour’s compliance’. In the current context of competitive pressures, McInnes (1985) argued in the same vein: consultation is used to elicit information from the workforce, to assure it of management’s expertise, and to engender co-operation by ‘educat[ing] stewards about the economics of business life’. Consultation, therefore, is primarily in the interests of management.

More recently, however, a view has developed that there may be scope for mutual gain, as managers search for competitiveness and employees for job survival in a context of globalised pressures (Kochan et al. 1986; Kizilos & Reshef 1997). Collective bargaining—with its threat of industrial conflict—may be an impediment to such a goal, so consultation has taken on a greater significance. It may be seen as a positive-sum game in which both managers and workers gain. The price for managers is a sacrifice of some of their prerogative, and for workers, a constraint on their capacity to collectively bargain.

following section, the validity of these criteria are examined by preliminary investigations of the data.

EMPIRICAL WORK Data and methods

We conducted questionnaire-based interviews, observation and archival research at two enterprises, beginning in the late 1990s. One study took place in a major multinational organisation and the other in a public sector hospital. The first study was carried out in a private sector organisation in the Australian subsidiary of a large capital-intensive multinational company that specialised in the design, manufacture and after-sales service of telecommunications equipment. This investigation took place in two divisions of one of its plants, involving 350 employees. There were two unions, both representing manual workers, one electrical and the other largely unskilled general trades. At the time of the study, there was no enterprise bargaining. Management had set up a formal consultation forum (JCC) of which all members were union representatives.

We collected most of the data in 1997. First, we observed the meetings of the JCC on six occasions between April and September. Second, we carried out lengthy semi-structured personal interviews with four senior managers, and the seven employee representatives on the JCC. Third, we examined company archives and literature in the form of annual reports, brochures, the JCC constitution and training manual, and the minutes of the JCC for 1996–7. In 1998, we made a report to the executive director with whom we had a lengthy interview. In 2002, we had interviews with the HRM manager.

The second study took place in a Victorian public hospital that offered services in acute, extended and psychiatric care. At the time of the study, it had a total staff of 2287 (Company Annual Report 1999). The largest occupational group consisted of nursing staff (716, 31%). The chief executive officer (CEO) reported to a board of management and, thereby, the Minister for Health. The hospital had a formal HRM department, with a director, manager and administrative/ clerical staff. Enterprise bargaining was carried out. One of the unions offered to participate in this study. Its membership consisted of senior and middle manage-ment, administrative, clerical, service and maintenance employees, and certain groups of nurses. The hospital also had a consultative relationship with the unions, and met with their representatives frequently, but in an informal, ad hoc and pragmatic manner.

The major part of the hospital data that was used in this paper comprises 40–120 minute semi-structured interviews that took place in August and September 2000. They were conducted with the CEO, the executive HRM director, three shop stewards and the trade union branch secretary. The archival data consisted of the following: annual reports and the current enterprise bargaining agreement.

differences lay in capital/labour intensity, private/public sector representation and level of bargaining unit.

In this paper, brief examples of the findings are presented. The content was validated by internal comparison and supporting evidence from observation and archival material.

RESULTS

Examples of the text are presented in Tables 1–3.

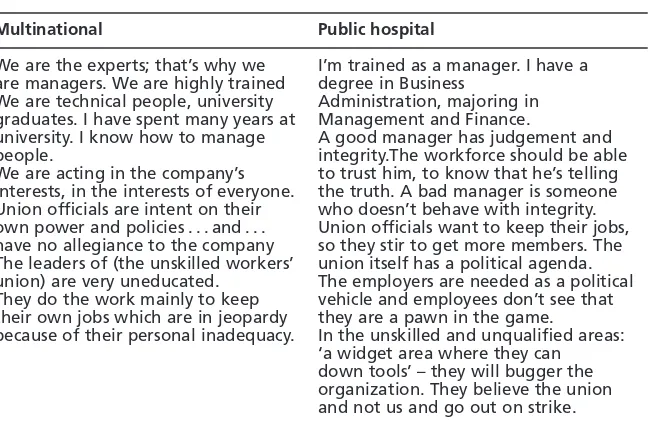

The interviews were investigated in relation to the two criteria: 1. Management must hold pluralist values

The existence of a pluralist attitude on the part of management was not sup-ported in either organisation (see Table 1). Managers held a unitarist philosophy. They felt they had the right to manage by virtue of their expertise and education. They argued that company and employee interests were synonymous and that employees should trust managers to act in their interests. These findings strongly support Ramsay (1997) and McInnes (1985). Moreover, management in both organisations was unsympathetic to trade unions, particularly to the represent-atives of unskilled workers.

2. Both parties must appreciate the possibility of mutual gain.

This was supported in the public hospital, but not in the multinational (see Table 2).

The findings for the multinational concur with those from case studies in the UK (McInnes 1985). Workers perceived consultation as undermining the union and they felt this was contrary to their own goals. Management attempted to use the JCC to bypass industrial agreements. The urgency of

Table 1 Managers and unitarism

Multinational Public hospital

We are the experts; that’s why we I’m trained as a manager. I have a are managers. We are highly trained degree in Business

We are technical people, university Administration, majoring in graduates. I have spent many years at Management and Finance.

university. I know how to manage A good manager has judgement and people. integrity.The workforce should be able We are acting in the company’s to trust him, to know that he’s telling interests, in the interests of everyone. the truth. A bad manager is someone Union officials are intent on their who doesn’t behave with integrity. own power and policies . . . and . . . Union officials want to keep their jobs, have no allegiance to the company so they stir to get more members. The The leaders of (the unskilled workers’ union itself has a political agenda. union) are very uneducated. The employers are needed as a political They do the work mainly to keep vehicle and employees don’t see that their own jobs which are in jeopardy they are a pawn in the game.

their appeals frightened workers. Flexibility was associated with job loss and alerted employees to their vulnerability.2 Representatives were told about definite lay-offs that they felt powerless to affect. They felt that only the union could offer them any protection or at least negotiate redundancy settlements. In a situation where they were forced to make a choice, union loyalties were reinforced. Not only did neither side feel it had gained, but existing mistrust was increased.

The results from the hospital are quite different. There was a perception of mutual gain. Management, in a quality-based HRM environment, cooperated with a collective bargaining system but constrained its effects by consulting informally with unions. Rather than bypassing unions, the HRM director worked with union leaders and consulted them to ‘iron out’ problems that could have led to industrial conflict. He oiled the wheels of enterprise-based collective bargaining in the interests of both management generally and of his own remuneration and success. In this particular environment where some job loss was averted, this also served the interests of employees.

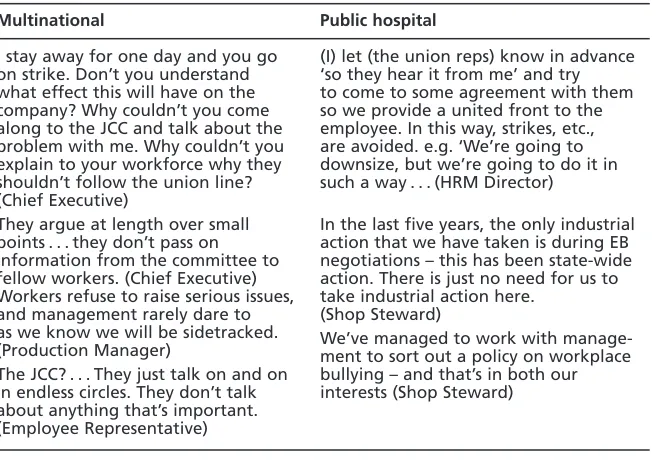

In terms of the effectiveness of consultation (see Table 3), the formal, ideologically-based JCC was held to be a failure at the multinational, where neither criterion was satisfied. But at the hospital, where there was a perception

Table 2 Perception of mutual gain

Multinational Public hospital

Managers

We’d be really happy if employees We want to be singing the same song as continued to work the same number the unions.

of hours each week. But, ideally, we’d The key is to get on with unions so they like to choose when those hours are – will support change.

and on what days – and to pay them the agreed flat rate.

Union members

They try to use it (the JCC) to We are very worried about job loss. determine industrial relations outside Consequently, we work with

normal collective bargaining. management, and do not take industrial action for local concerns.

Have you noticed how often they Job security is a major issue for us. The mention lay-offs and shutdown? health sector has rapidly evolved in (Name of local competitor) shut down terms of capital works and technology. not long ago, and it frightens me to We have to keep up with changes death to think about it. There’s no and be proactively involved in the work round here. change process.

Fear-mongering: that’s what the JCC The trade union and management lobby is for. They (management) have this the government to get additional down to a fine art. funding so that members’ jobs can be

quality of their services and excellent. The only thing that will protect us is

of mutual gain, the limited pragmatic consultative relationship was deemed successful by both parties.

It was not merely the perception of mutual gain that was important, but the possibility of its realisation. The multinational was subject to the vagaries of global competition, and labour costs had little impact, especially in a capital-intensive firm whose fortunes depended on international finance rather than flexible practices. The public sector hospital was not subject to globalised competition and industry-level bargaining. Moreover, in a labour-intensive industry, the reaction of unions was important in terms of affecting output because labour’s contribution was essential to quality service. Management and union lobbied together to gain additional finance from government. Managers achieved change without conflict.

CONCLUSION

What is the importance of these findings for trade unions? First, trade union consultation will only be worthwhile where there is a realistic expectation of a ‘pay-off’, especially with regard to a prevention of job loss. Second, it is unrealistic to expect management to share a pluralist ideology. Management is unequivocally unitarist. It is important, however, that managers recognise that some employees have collective values and loyalties that lie outside the company. Unions should be wary of attempts to use consultation as a ‘bypassing’ technique. If these two criteria are not upheld, unions may be well advised to rely on traditional methods of bargaining.

Table 3 Effectiveness of consultation: perceptions of different parties

Multinational Public hospital

I stay away for one day and you go (I) let (the union reps) know in advance on strike. Don’t you understand ‘so they hear it from me’ and try what effect this will have on the to come to some agreement with them company? Why couldn’t you come so we provide a united front to the along to the JCC and talk about the employee. In this way, strikes, etc., problem with me. Why couldn’t you are avoided. e.g. ‘We’re going to explain to your workforce why they downsize, but we’re going to do it in shouldn’t follow the union line? such a way . . . (HRM Director)

(Chief Executive)

They argue at length over small In the last five years, the only industrial points . . . they don’t pass on action that we have taken is during EB information from the committee to negotiations – this has been state-wide fellow workers. (Chief Executive) action. There is just no need for us to Workers refuse to raise serious issues, take industrial action here.

and management rarely dare to (Shop Steward)

as we know we will be sidetracked. We’ve managed to work with manage-(Production Manager) ment to sort out a policy on workplace The JCC? . . . They just talk on and on bullying – and that’s in both our in endless circles. They don’t talk interests (Shop Steward)

ENDNOTES

1. A long term, wide-ranging study of employee participation in Australia is being conducted in the Centre for Employment and Labour Relations Law at Melbourne University.

2. A separate quantitative regression analysis, based on a survey of workers from the two divisions which the JCC represented, demonstrated that those who felt their jobs were insecure were significantly less likely to be favourable to the process of consultation than those who felt secure (Kwei 1997).

REFERENCES

Ackers P, Marchington M, Wilkinson A, Goodman J (1992) The use of cycles? Explaining employee involvement in the 1990s.Industrial Relations Journal24, 268–83.

Ben-Avner A, Jones DC (1995) Employee participation, ownership and productivity: A theoretical framework, Industrial Relations34 (4), 532–54.

Brown M, Ainsworth S (2000) A Review and Integration of Research on Employee Participation in Australia, 1983–1999. Centre for Employment and Labour Relations Law, Working Paper No.18, December.

Davis E Lansbury R (1996) Managing together: Consultation and Participation in the Workplace.Sydney: Longman.

Keenoy T (1990) HRM: A case of the wolf in sheep’s clothing? Personnel Review19 (2), 3–9. Kizilos M, Reshef Y (1997) The effects of workplace unionisation on worker responses to HRM

innovation. The Journal of Labor Research18 (4), 641–656.

Kochan TA, Katz HC, McKersie R B (1986) The Transformation of American Industrial Relations, N.Y.: Basic Books.

Kochan T, Osterman P (1994) The Mutual Gains Enterprise. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Kwei M (1997) The invisible whip: Extending the cycles of control.Honours dissertation, Department of Management and Industrial Relations, University of Melbourne.

Lansbury RD Davis EM (1992) Employee participation: some Australian cases.International Labor Review131 (2), 231–48.

Marchington M (1992a) The growth of employee involvement in Australia. Journal of Industrial Relations9, 472–81.

Marchington M (1992b) Surveying the practice of joint consultation in Australia. Journal of Industrial Relations12, 530–49.

McInnes J (1985) Conjuring up consultation: the role and extent of joint consultation in post-war private manufacturing industry. British Journal of Industrial Relations23 (1), 93–113. Ramsay H (1977) Cycles of control: worker participation in sociological and historical perspective.

Sociology11 (3), 481–506.