E

MPLOYMENT

R

ELATIONS IN

C

HINA

:

A S

TUDY OF

T

WO

M

ANUFACTURING

C

OMPANIES

FANGLEECOOKE*

T

he need for China to survive and to compete in the rapidly globalising world economy has never been so compelling as in the past decade. Reforming state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has thus been at the top of the Chinese government’s agenda since the mid-1990s. This has led to the emergence of new patterns of enterprise ownership and consequently new employment relations which are distinctively different from those in the traditional SOEs. This paper explores the ways key elements of employment relations may have changed as a result of ownership change; why the trade unions have failed to perform adequately, and what the impact has been on workers of the new form of employment relations. In this paper, the term employment relationsis used to include a broad range of issues which fall within the scope of analysis of both traditional fields of industrial relations and human resource management. In particular, aspects of employ-ment relations such as recruitemploy-ment, pay, training, work reorganisation and the role of the trade unions are explored.As a nation, China’s need to survive and to compete in the rapidly globalising world economy has never been so compelling as in the past decade. By the end of the last century, reforming and revitalising the outmoded state-owned enter-prises (SOEs), which made up over 50 per cent of its GDP and employed the majority of its workers, was at the top of the Chinese government’s agenda as part of its social and economic reform. In the process of this reform, millions of workers were laid off from their life-long jobs and from the only company they had ever worked for, and thousands of formerly SOEs changed ownership to private-owned, joint venture or employee share-ownership. This dramatic change has fundamentally altered the nature of employment relations once characterised by central planning, low pay, low productivity, slow pace of work and relatively harmonised labour-management relations in which employees had no real voice in the business but could expect to be relatively well looked after. The mass change of ownership from the former SOEs has resulted in the national systems of employment relations losing much of their distinctive character on the one hand,

while creating a context for the reshaping of new employment relations at enter-prise level on the other. As Kochan (1996) identified, the critical human resource (HR) challenges facing firms in China are liberalising the labour markets, and decentralising management authority without disintegrating into civil and polit-ical unrest. Yet few in-depth micro-level investigations such as well-informed case studies have been carried out, to explore in what way changes are happening and the impact of these changes on the workers.

This paper explores, through in-depth case studies of two small and medium-sized manufacturing companies in southern China, in what way the workers’ terms and conditions and their wider experience of work may have changed (often for the worse) as a result of ownership change; why trade unions have failed to per-form adequately in the new context of employment relations; and what the impact has been of the new form of employment relations on workers. The term employ-ment relations is used in a broad sense in this paper to cover a broad range of issues which fall within the scope of analysis of both traditional fields of indus-trial relations and human resource management. In particular, aspects which are central to the domain of employment relations such as recruitment and promo-tion, pay, training, work reorganisation and the role of the trade unions are explored.

CHANGING CONTEXT OF INTERNATIONAL EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS

The nature of employment relations is determined by the relative power of capital and labour, and the interactions between employers, workers, their col-lective organisations and the state. In recent years, new forms of international competition aided by rapid technological innovations and adoption, and reduced barriers to cross-border trading have significantly altered not only the ways indi-vidual organisations and nations arrange their production systems, business strate-gies and organisational structures, but also the power base from which individuals and their representing bodies respond to the changes at workplace, industry and national level. This phenomenon has captured the attention of scholars of indus-trial sociology. Notably, Piore and Sabel’s influential thesis The Second Industrial Divide(1984) and Kochan et al.’s work The Transformation of American Industrial Relations(1986) have been a source of on-going debates concerning the devel-opment of new management approaches to industrial relations and production systems. Amongst other issues, both books ‘raised troubling questions about the future of trade unions, suggesting that unless unions took account of these devel-opments their future viability was doubtful’ (Kitay 1998: 3). While the debate goes on as to whether employment relations have been transformed and to what extent new models of employment relations are emerging in the Western indus-trialised countries and the newly indusindus-trialised Asian-Pacific nations over the last two decades, recent social and economic reforms in China have certainly brought profound consequences for its employment relations, particularly in the formerly state-owned enterprises.

which included medical care, housing benefits, pensions and jobs for spouses and workers’ school-leaver children to name but a few (Cooke 2000). In the com-munist system, in which labour and capital are supposed to share the same inter-ests, trade unions in the SOEs in China play only a welfare role under the leadership of the Communist Party. They carry out this function effectively by acting as a ‘conveyor belt’ between the Communist Party and the workers in the enterprise (Hoffman 1981). Under the new ownership form, the welfare role of the state has largely disappeared and the harmonious management-labour relationship has been replaced with one which is characterised by conflicting inter-ests, rising disputes and increasing inequality in contractual arrangements between management and labour. For example, in a survey of over 3000 workers con-ducted in 1998 in Sichuan Province on their perception of labour-management relations, 21.6 per cent of the workers felt that the relationship was good, whereas 11.3 per cent considered it reasonable, 19.7 per cent thought it average, and 47.4 per cent voted poor. For those who felt that relations were poor, 22.1 per cent believed that management was abusing disciplinary procedures; 27.4 per cent felt that their managers were autocratic; and 42.6 per cent considered that the distribution system was unfair (Lu 1999).

According to the Labour Law (Chapter 1, No. 7), ‘Trade Unions shall repres-ent and protect the legal rights and interests of workers independrepres-ently and autonomously and develop their activities according to the law’. However, trade unions in China have not been able, for various reasons, to take up an indepen-dent bargaining role to protect the welfare and interests of the workers in a style more commonly found in the Western economy, even though this role of the trade unions is clearly defined in the Labour Law implemented in 1995 in China. Some trade union officials took pride in considering themselves the representa-tives of the enterprises. Some even confronted workers on behalf of the manage-ment during the handling of labour-managemanage-ment disputes, forgetting that they should be representing the workers’ interests instead (e.g. Lu 1999; Sheehan 1999).

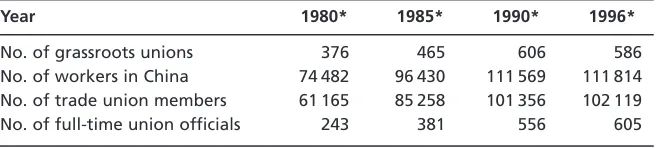

The formal national union structure in China goes back to the early 1920s with the setting up of the All China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) in 1925 in Guangzhou. The current structure of Chinese trade union organisation has not changed drastically since 1949 (Warner 1990). The types of unions have remained roughly the same, although there has been an expansion of union membership as urbanisation has drawn more workers into industry (Ng & Warner 1998). Drawing their membership from all sorts of occupations and sectors includ-ing manual and non-manual workers in factory, hospital, school and university, the trade unions do not have any distinctive ‘trade’ characteristics, as they all belong to the same ‘father’: ACFTU (see Table 1). The formal ‘representative function’ of the unions is supplemented by the trade union-guided Workers’ Congress which is a new organisation formed by workers’ representatives (Zhu 1995). The Workers’ Congress has been given the legal right to:

important rules and regulations; it may decide on major issues concerning workers’ conditions and welfare; it may appraise and supervise the leading administrative cadres at various levels and put forward suggestions for awards and punishments and their appointment and approval; and it democratically elects the director (Liu 1989: 5–6).

SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZEDSOES INCHINA

Small and medium-sized SOEs are chosen for study here because they occupy the gap between large SOEs and non-SOEs. They lack the advantages of either the former: having large-scale, advanced technology, higher level of technical skills, favourable policy, or the latter: autonomy of decision-making and hence flexibility in the market competition. The small SOEs are in the most disadvan-taged position in the market, their organisational system incomplete and their technology management backward. As market competition intensifies, the prob-lems facing these small enterprises become more pertinent. Many of them have been making a loss in recent years. According to Liu (1997), 24 000 SOEs made a loss in 1994. Of these, 19 700 were small and medium-sized enterprises, i.e. 82 per cent of the total loss making firms. In 1998, China’s legions of small and medium-sized SOEs were told to fend for themselves, as part of the Prime Minister Zhu Yongji’s initiative of reforming the SOEs (The Economist,13 June 1998). Many were forced to wean themselves from the state abruptly. Reform seemed to be the only way out, and (partial) privatisation and employee-share ownership appeared to be the favoured choice.

On the other hand, small and medium-sized SOEs do have an advantage in the process of reform, compared with the large SOEs. They have relatively small capital assets and debts, a clear ownership relationship, they find buyers and con-tractors more easily, and have far fewer accessories that come with the enter-prise, unlike the large enterprises which carry with them a miniature society consisting of school, clinic, entertainment club, shops, restaurant, police station etc. (Cooke 2000). These small enterprises are also less constrained by the traditional command system. They are more independent and can change their products or services more rapidly. But much depends on the leadership quality of the senior manager(s). Equally, intervention from the state is limited when these enterprises change ownership or reform their HR policies, because the pos-sibility and the impact of labour unrest will be limited. While attention from the 22 THE JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS March 2002

Table 1 Basic statistics on trade unions in China

Year 1980* 1985* 1990* 1996*

No. of grassroots unions 376 465 606 586

No. of workers in China 74 482 96 430 111 569 111 814 No. of trade union members 61 165 85 258 101 356 102 119 No. of full-time union officials 243 381 556 605

*All figures in thousands.

state is heavily involved in overseeing a smooth reform of large enterprises in order to minimise the risk of social upheaval, workers in small enterprises are largely left to their own devices in their battles with management. Managers in these enterprises have stronger powers not only to ‘hire and fire’ but also to reorganise work and to determine pay levels and other HR policies.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research is a pilot study of a larger scale project on changing employment relations in the (former) SOEs in Guangdong Province funded by the Provincial Government. An in-depth case study approach was adopted for the research in which two manufacturing companies (BeerCo and MotorCo) were investigated. Both are located in a medium-sized industrial city in Guangdong Province in southern China. The two companies have changed ownership from SOE to a joint venture (BeerCo) or an employee share ownership (MotorCo), with the former a flagship company of the city and the latter a pretty much average-performer. As the pseudonyms suggest, BeerCo produces a range of beer products while MotorCo manufactures a series of small electric motors for con-struction and production equipment.

While the choice of the size (small and medium-sized) of the case study-firms has a strong rationale as explained earlier, the choice of these two particular manu-facturing firms is more opportunistic. As any (Western) researchers, government officials and business people who have experience of dealing with matters in China will know, ‘guanxi’,or a network of personal relationships is very important in getting anything done. Many China scholars also view ‘guanxi’ as a deep-seated cultural fact of Chinese society (e.g. Bian 1994; Yang 1994, Ruizendaal 1995; Tsang 1998; Guthrie 1998; Gamble 2000; Glover & Siu 2000; Tung & Worm 2001). In general, academics in China do not have much bargaining power in negotiating research access with business organisations, which do not have a tradition of supporting social science research either in the form of surveys or case studies. Gaining access at a meaningful level is not easy without ‘guanxi’, and even if access is granted the interviewees may not be inclined to reveal a true picture but repeat well-rehearsed official lines. The emphasis on hierarchical structure in Chinese society also predetermines that access negotiation takes place at a higher end of the management level of the two parties in order to give face to the company’s high ranking officials and to stress the high profile of the research. BeerCo and MotorCo were therefore chosen specifically because a personal relationship at the higher end of the hierarchy already existed.

Although the existence of the personal relationships prior to the conduct of the research has been advantageous to the research team in providing pre-understanding and pre-understanding of the case study firms (Gummerson 1991), the researchers were aware that they should not allow this to limit their per-spectives. Rather, they should draw upon such insight and expand it indepen-dently by demonstrating theoretical sensitivity or flexibility of mind (Gummerson 1991).

a process through which the subtlety of local meaning may be lost. More impor-tantly, the interviewees were more receptive to the researchers because language, at least in China, serves not only as a means of communication but also as ‘a hall-mark of local identity’ (Ruizendaal 1995: 4).

Over 20 formal interviews were carried out, in addition to informal conver-sations, with senior managers, middle managers, trade union officials, supervisors and shop/office-floor staff between September 1999 to June 2000. Six interviews (one director, two managers and three workers) were conducted in MotorCo and the rest were with BeerCo. An open-ended, semi-structured interview technique was employed so that new avenues which presented themselves in the course of discussion could be followed up. Interviews with the shop/office-floor personnel typically lasted about 45 minutes. Interviews with the managers normally lasted much longer (between one and three hours). Company documents such as policy statements and training plans were obtained, but the more sensitive documents, for example the exact amount of pay received by individual managers or workers, were not disclosed for tax reasons. Follow-up interviews were made in April 2001 to capture any changes relevant to the research that may have taken place since the first round of interviews.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE CASE STUDY FIRMS

Beer brewing in China is a booming, but at the same time highly competitive, industry. The total beer output of the country rose from 690 000 tons in 1980 to over 15 million tons by 1995, rendering China the second largest beer pro-ducing country after the United States with an increasing variety of products (see Wang 1998 for more details of the industry). The growing industry is, however, completely unplanned and uncoordinated, packed with ever emerging small plants of low production capacity (with the average at below 22 000 tons) at township level which are swamped by a few superpower foreign plants. For example, in the 1980s there were over 2000 breweries producing nearly 1500 brands of beer products (Wang 1998). By 1990, the number of breweries had fallen to about 800, and only 550 of them still survived in 1999. In 1995, the total sale volume of the five top home-grown breweries made up only 12 per cent of the market, whereas the top seven American breweries in China took 75 per cent (Wang 1997). According to the Third Industry Census in 1995, the total production capacity of the industry by the end of 1995 was 22.53 million tons, but only 73.5 per cent of that capacity was utilised. By the beginning of 1996, the top ten breweries in the world had all found willing brewery partners in China to set up joint-venture businesses. Most of these joint joint-ventures have provided opportunities (funding and technology) for the breweries (many of them originally owned by the local government) to expand the scale of production and upgrade product quality (Gu 1997). BeerCo is one of the larger units and is included in the top 50 breweries in the country and the best in Guangdong Province, a prosperous province in southern China.

which has led to intensified sales competition and price cuts. In 1996, the aver-age price of motors was reduced by 20 per cent which was continued by another 10 per cent in 1997 and a further 12 per cent in 1998 (Yuegang Xinxi 1999). Again, the product market has been dominated by a few large and strong players. MotorCo does not even feature in the market. It survives on marginal businesses.

BeerCo

BeerCo was formed in 1987 as an SOE (see Table 2). The enterprise made heavy losses from day one until 1995 when a series of organisational changes includ-ing management and departmental restructurinclud-ing began to take place. The main reason for its loss making was poor sales which severely restricted the output of the plant. For example, the production target was 30 000 tons when BeerCo was formed, but this target was not reached until 1995. Prior to that, production had been lingering below 20 000 tons. In 1996 the local government decided to change its ownership status from a SOE to a joint venture (with Hong Kong investment) in an attempt to improve its competitiveness. It was thought by the BeerCo man-agement and workers that a joint venture would bring in much needed external investment which would double the financial base of BeerCo so that it would have more capacity to operate in the competitive brewing industry. However, the joint venture turned out to be a transfer of ownership instead of a capital injection, in which 51 per cent of the shares were transferred to a Hong Kong investment company. The ownership transfer took place in early 1997 and the Hong Kong Partner invested in a new production line for BeerCo. When BeerCo was first set up, there was only one semi-automatic production line with a production capacity of 60 000 tons per year. Since the introduction of a fully automatic production line from Germany in 1997 (in production in 1998), BeerCo’s total annual production capacity has increased to 150 000 tons. Its beer products consistently met the ‘excellence’ grade of the national quality standard. In 1999, BeerCo was accredited ISO 9002 by the state quality authority after nearly two years’ preparation. The production target for the year 2000 was 100 000 tons, but much depends on BeerCo’s ability to sell. The reason for the

Table 2 General information on BeerCo and MotorCo

BeerCo MotorCo

Former ownership State-owned State-owned New ownership Joint-venture (state & Employee ownership

Hong Kong)

Ownership change 1997 1998

No. of employees (2000) 680 160

Quality initiatives ISO 9002 accreditation ISO 9000 application Product market Upper end of the market Lower end of the market Customer base National but mainly National but mainly

under-performance of sales is local protectionism and geographical monopoly which prevail in the beer product market in China. With a local consumption of only 20 000 tons, the sales team has to work very hard to promote their products to a wider geographical area.

Working on a round-the-clock shift system, BeerCo had a workforce of 680 people in June 2000. The total income (cash and material in kind) of the BeerCo employees has always been high by China’s standards even when it was making a loss. On average, the ordinary workers earned 26 000 RMB (about US$3130) in 1999 while managerial and professional staff were on 35 000 RMB (about US$4220). It was speculated that senior managers were on a much higher rate of pay but the figure was unknown.

MotorCo

MotorCo is a relatively small (by Chinese standards) manufacturing company established in 1974. In April 2000 it had 160 working employees and another 130 retired employees. MotorCo has long been a poorly-managed and unprofit-able company whose employees have been on low pay for workers in an SOE. In 1998, MotorCo changed ownership from a state-owned limited company to an employee share ownership limited company. The Managing Director owned 36 000 shares, directors owned 16 000–30 000 shares each, middle managers and professionals owned 10 000–15 000 shares and the ordinary workers owned 2500–6000 shares each. A ‘one share one vote’ system was adopted for the decision making process which ‘enables the workers’ participation in the man-agement of the Company’. In principle, the Managing Director and other direc-tors were to be ‘elected’ by shareholders.

materials for their production which in turn affects the quality of the products they turn out.

MotorCo has been producing a series of motors which, according to new motor authority regulations, were to be phased out in the near future. The Company makes a few high quality motors and changes their nameplates quarterly to deal with the quality inspection from the state authority. MotorCo was only operat-ing at half of its production capacity due to poor sales of standard products and lack of orders of specified products. The level of technical competence of the staff is generally low. The Manager of the Technical Department came from an apprentice background and has limited theoretical knowledge. On the other hand, the young graduates recruited in recent years have theoretical knowledge but lack practical experience. There is no apprentice training scheme. Not surprisingly, MotorCo does not have any business strategy, long-term planning, or even a plan for the following year. Research and development is unheard of. The Managing Director just ‘plays it by ear’. His directorship was a five-year contract. ‘If thing was smooth, then he would continue for a second term. If not, he would sell every-thing, make a profit and run’(The Production Manager). In the absence of strong leadership, a long-term business strategy and a skilled workforce, MotorCo is incapable of designing and producing new products which are competitive in the market place.

RESHAPING OF EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS UNDER THE NEW FORMS OF OWNERSHIP

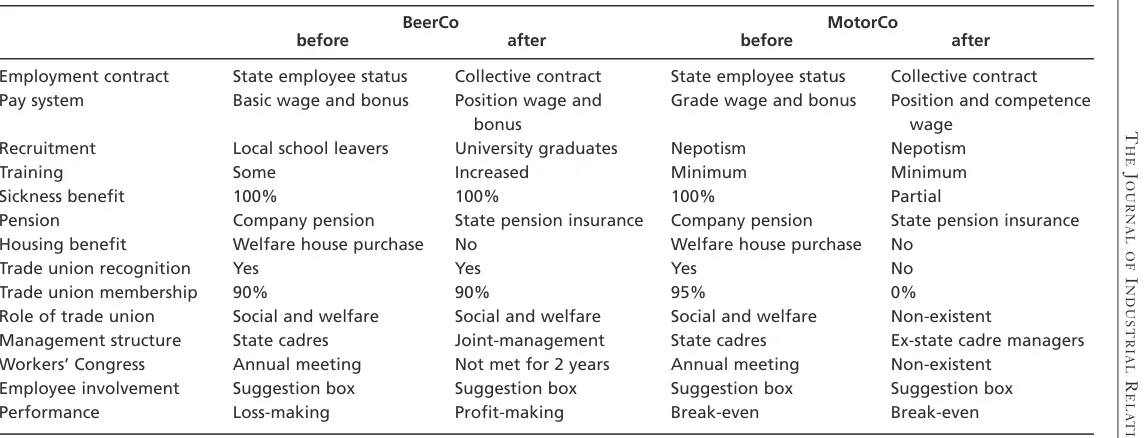

Unbound from the detailed control of the state, both BeerCo and MotorCo man-agement now have much greater autonomy in the operation of their business, including the freedom of making decisions in recruitment, pay and dismissal etc. Although managing by the rules and regulations remains largely the norm, the change of ownership of BeerCo and MotorCo has brought major changes to issues such as recruitment, training, promotion, pay, work organisation, and the role of the trade unions and Workers’ Congress. These changes are a somewhat mixed blessing for the workers (see Table 3).

Recruitment and promotion

28

T

HE

J

OURNAL

OF

I

NDUSTRIAL

R

ELA

TIONS

March

2002

Table 3 Employment relations in BeerCo and MotorCo before and after ownership change

BeerCo MotorCo

before after before after

Employment contract State employee status Collective contract State employee status Collective contract Pay system Basic wage and bonus Position wage and Grade wage and bonus Position and competence

bonus wage

Recruitment Local school leavers University graduates Nepotism Nepotism

Training Some Increased Minimum Minimum

Sickness benefit 100% 100% 100% Partial

Pension Company pension State pension insurance Company pension State pension insurance Housing benefit Welfare house purchase No Welfare house purchase No

Trade union recognition Yes Yes Yes No

Trade union membership 90% 90% 95% 0%

Role of trade union Social and welfare Social and welfare Social and welfare Non-existent

Management structure State cadres Joint-management State cadres Ex-state cadre managers Workers’ Congress Annual meeting Not met for 2 years Annual meeting Non-existent

Employee involvement Suggestion box Suggestion box Suggestion box Suggestion box

manager. The Company has now established a policy of flexibility in promotion which replaced the seniority system traditionally adopted in Chinese organ-isations. Those who are seen as capable of new responsibility will be promoted and those who are considered ineffective in their leadership will be demoted. This new policy has brought some resentment from the older workforce as the major-ity of the newly promoted are those who are relatively young with higher quali-fications and more updated skills and knowledge. Resentment of the new promotion system also came from sidelined managers and supervisors, many of whom are ex-army or ex-rural cadres of an older generation who owed their posi-tions more to their personal ties or political standing than to their expertise in industrial management (Sheehan 1999).

The change of ownership in MotorCo has not improved MotorCo’s ability to recruit high quality graduates from good universities. University graduates are unwilling to come to MotorCo because of its low pay and unhealthy prospects as a firm. Those who came would only stay temporarily, using MotorCo as a stepping stone to a better job elsewhere. Others came as a result of nepotism, carrying its own inherent disadvantages.

Training

Since the change of ownership, BeerCo has invested heavily in training its (pro-duction) workforce at different levels. Each person has to spend 100 hours on training each year. The objective of increased training has been to enhance the managerial staff’s management skills and the workers’ production-related skills and general education level. Two universities were given contracts to provide man-agement training (e.g. supervisory skills) for (potential) managers and supervisors, professional and technical training (e.g. accounting and finance, food chemistry, laboratory analysis) for professionals and technicians, and further education (e.g. literacy and numeracy) for the shop/office-floor employees. Production efficiency and health and safety have also been important elements in the training. In addi-tion, IT skill training has been available for all levels of employees should they want it. The training courses were repeated the following year to reinforce memory. In addition to in-house training, core members of staff were sent to the manufacturers for training when new packaging equipment was purchased. They then trained their colleagues. Most of these training activities have been carried out in the workers’ own spare time. According to the workers interviewed, most of the training has been a useful addition to their skills and knowledge. Training was particularly welcomed at the managerial and supervisory level. However, work re-organisation and intensification since the introduction of the second produc-tion line has made the trainees too tired to attend the courses or reduced their motivation to learn after they have been removed from the post for which they had been receiving training.

for ISO 9000 accreditation. A consultancy agency was contracted in to prepare the documentation for MotorCo. The preparation of the documentation has had no real impact whatsoever (e.g. training) on the workforce other than as a public relations exercise for the Company. The consultants go to one firm and prepare the documentation for the firm and then sell it to another firm. The Manager of the Technical Department commented, ‘ISO 9000 looks good on paper but not in practice’. Three managerial staff were sent on an internal asses-sors training course. It was a one-week course held by the ISO 9000 authority. Trainees were guaranteed their assessor qualification. Course fees were charged to their company. However, the skill, the quality and technology standards of MotorCo were nowhere near the true requirement of ISO 9000. The Director has a powerful network extending to the quality authority which issues the quality certificates. MotorCo was accredited ISO 9000 status at the end of 2000. The Managing Director’s approach to quality in a way reflects that which prevails in many companies in China. For example, Zhao et al.(1995) found that the standard of the product quality varies in China and that its managers and workers tend to have a low level of awareness of the quality management tech-niques fashionable in the West. Glover and Siu (2000) also found that public knowledge/image of the quality of a product are to a certain extent determined by the nature of the external guanxi rather than by the true quality of the product per se.

BeerCo’s increased investment in workforce skill training reflects a new train-ing trend more commonly found in large SOEs and joint ventures (e.g. Child 1996; Ding & Warner 1998; Cooke 2000). For SOEs, the drive to increase skill levels comes from the state which also foots the bill. For joint ventures and foreign-owned firms, mass skill training for the workforce is usually a necessity during the early stage (Bjorkman & Lu 1999a, b). In-house training methods are often adopted for workers while managerial and professional staff have more opportunities to be sent away for intensive training either at universities or at their parent firms overseas. The emphasis of the training is on technological skills and increasingly on managerial skills for managers. The lack of training at MotorCo also reflects the pattern of absence of training in many small and private firms in China which the state has little influence on and lends little support to.

Pay

The introduction of individual bonuses, a key feature of the reforms in China since the 1980s, intended to break the egalitarianism, has been particularly troublesome and had little real effect. For example, Shirk (1981) has noted that the awarding of bonuses by workers themselves in small-group ‘evaluation and comparison’ sessions resulted in a strongly egalitarian distribution of the extra money. Informal rotation systems were often used for workers to take turns to receive the highest bonus and then share it with their workmates by going out for dinner together.

The secrecy of the bonus system initially introduced at BeerCo removed the transparency which acts as a control mechanism to prevent the widening of bonus differentials and to judge peers’ performance against their bonus. Whether the bonus differential was wide enough to be deemed unreasonable or not was quite another matter. Then again, the argument was, if there was not a wide gap, why should it be so secretive? This bonus system was soon replaced by another wage system in which each department was given a lump sum for their operating cost and wage. This system again backfired quite quickly because each department was trying to keep the costs down in order to receive higher pay. Sales staff were not making any trips to promote sales; the production department was not replacing failing or failed parts of the equipment; and the canteen was feeding the workers with undesirable food. Hastily this system was yet again replaced by the latest system in which each department was given a fixed wage bill against a set production target. Wage increases for workers in the same department were dependent on the reduction of labour with sustained, and even enhanced, pro-ductivity. Equally, an increased number of workers (in order to meet production targets) will not warrant an increased wage bill for the department. No overtime would be paid, which has put a stop to the abuse of overtime claims (someone had previously claimed 800 hours overtime in a month). This latest system was welcomed by the shopfloor as their total income has generally risen, but this was achieved at the expense of the administrative and supporting staff who have been put on a lower rate of pay. For BeerCo, the total wage bill has not changed. It only took away from one group of workers (administrative and supporting workers) and gave to another (the production-related workers). Even among pro-duction workers, grievances over pay still exist mainly because of the flat rate of basic wage irrespective of length of service. This rule is at odds with the tradi-tional Chinese wage system in which seniority has played an important part in the wage structure.

of 50 per cent, and ordinary workers 20 per cent. This pay rise is not a reflec-tion of product output, quality or sales. Rather, it is the Managing Director’s attempt to show the workers that he is a ‘good boss’ and that they should be more motivated to work for him. The increased wage bill is financed by the income which the Company raises from renting buildings out as shops and offices. These buildings have been built around the factory in the last three years for the twin purpose of reinforcing plant security and increasing company revenue. It is not known how long this bonus will be maintained. As was illustrated earlier, regional differentials in pay exist in China for workers doing similar jobs, for geographical and therefore social and economic reasons (Johnston 1999). However, this ‘spatial inequality’ (Johnston 1999: 1) for the MotorCo workers was exacerbated by the absence of a mechanism through which wages can be negotiated and distributed in a fairer system.

Work reorganisation

In early 1999 after the second production line was put into operation, BeerCo restructured its production and packaging departments. Both departments have been downsized from 350 people for the first production line to 300 people covering both production lines on three shifts (round-the-clock). Displaced workers (who were deemed less competent than those workers who remained on the production lines) have been re-deployed to replace the temporary workers who were originally employed to carry out unskilled and laborious work. Grievance levels are high from this group of re-deployed workers, in part because they found it difficult to come to terms with the loss of face involved in down-ward adjustment and in part because they had neither the skill nor the strength (many of them were older workers) to carry out the (albeit unskilled) tasks required by their new post. Some of these displaced workers had been removed from the production line because of their previous poor behaviour record, yet no official warning has ever been given to them about their behaviour. Neither has train-ing or counselltrain-ing been given to the displaced workers to help them adapt to the new situation. When we asked the HR manager if BeerCo was going to do any-thing to ease the pain, the reply was: ‘they should be grateful to the Company that they were given a job instead of being kicked out of the company like many others were. There are plenty of people out there waiting to be employed’. Yet in the same interview the HR Manager declared that a new company culture (in line with that of ISO 9002) for BeerCo’s employees demanded care and respect for their fellow workers.

management among different shifts and groups of workers because ‘there will be no pressure or motivation (for the workers) without any competition’ (the HR Manager of BeerCo). In order to live up to the standard of ISO 9002, the Company has been very strict with the quality of the products. Workers have to redo their work if it has failed to meet the national standard of ‘excellence’ even if their work may have reached the ‘pass’ standard. Fatigue and stress were creep-ing in and morale was fallcreep-ing at the time of the interviews.

As in BeerCo, there was no redundancy in MotorCo when its ownership changed and the organisation was restructured. Although departmental mergers have taken place following the ownership change, limited work reorganisation has occurred. People mostly continue doing what they have always done. However, a few people were required to move to other posts mainly from a higher and more skilled post to a lower and less skilled post with less pay. Those who did not obey the order would be dismissed without redundancy pay. Three people were dismissed (termed ‘resigned’) under this ultimatum. In general, work has not been intensified for the workers in MotorCo because of their lack of production work.

THE ROLE OF THE TRADE UNION AND THEWORKERS’ CONGRESS

BeerCo has a full-house of trade union officials which includes a trade union chair-man, a deputy trade union chairwoman and a trade union officer. Each year, they are given a reasonable amount of funding for trade union activities, which involve mainly consoling sick and bereaved employees, organising entertainment and sports events aimed at boosting employee morale, and increasing commitment, as well as raising the Company’s profile in the local community. However, the trade union has no real impact at all in terms of safeguarding the workers’ inter-ests in labour-management disputes. As the HR Manager pointed out, ‘The trade union officials are not very competent at their job. We are now co-operating (joint-venture) with the capitalists (Hong Kong) and a strong trade union is needed to fight for the workers’ interests. But the trade union has not played that role effectively’. In fact, the trade union deputy chairwoman was the ex-Personnel Manager who was displaced as a result of departmental re-structuring (merger). Because BeerCo could not find a managerial position for her, a deputy trade union chairman post was created for her.

Trade Union Chairwoman expressed sympathy for the Company on this occa-sion, suggesting that ‘the workers should understand the Company’s difficulty and be more patient’. Another incident occurred in February 2000 when the trade union signed a collective contract, ‘a recent industrial relations innovation’ (Warner and Ng 1998: 1), with the Company on behalf of the workers. Workers have not been given a copy of this three-year rolling contract and nobody could recall what details had been included when they were asked in the interviews.

Things in MotorCo were worse. When MotorCo changed ownership from an SOE to employee share-ownership, the trade union was dissolved, or more precisely de-recognised, by the Managing Director, who claimed that the old trade union belonged to the old ownership and that a new trade union had to be re-established to represent the new ownership. He also decided that a full-time post would not be created for a trade union chairman because of the small scale of the company. However, ‘the Company would consult the workers and listen to their opinions and suggestions when making important decisions and procedures for the Company’ (Manifesto of the Managing Director). Nobody could argue against this assertion as the Labour Law only requires the founding of a trade union when a new company is set up, but it does not illegalise the dissolution of a trade union when an ownership change takes place. The workers of MotorCo did not want to re-establish a trade union because ‘it does not do anything for us’ (a production worker). In theory, the function of the trade union was replaced by that of the shareholder committee. In practice, none of the organisational mechanisms (the board of directors, the board of supervisors and the shareholder committee) has any power except the Managing Director himself, who alone made all the decisions including wage, bonus, recruitment, promotion, price of products etc. His decisions would only be handed down to the board of direc-tors for approval as a gesture. If it is a fact that Chinese senior managers are inclined to deal with matters personally and are reluctant to delegate responsi-bility (Child 1996), then MotorCo’s privatisation provides its Managing Director more freedom to do so. This situation was succinctly summarised by a senior manager of MotorCo:

The ownership change has created a perfect opportunity for the Managing Director to exercise his dictatorship without any cost, and to profit profusely at the expense of the poverty of the employees. Who said that ownership change could be achieved without any price? It is a load of rubbish.

The Workers’ Congress is required by law to hold an annual meeting but this has not occurred at BeerCo for more than two years. Even when it was held, it was only a symbolic gesture like that in many other Chinese organisations and an opportunity for a banquet for everybody. The workers knew very well that any issues, if raised, would not be dealt with. At MotorCo, the Managing Director decided that the Workers’ Congress should be merged with the annual shareholders’ meeting to discuss any issues concerning the management of the business.

the incoherence of HR and employment policies adopted by the firms and the inconsistent outcome of these policies, which often point to short-term behav-iour and exploitation of workers on the one hand, and increased pay and poten-tially higher employability of the workers due to multi-skilling and increased level of training on the other. The finding of this study also reflects that of Benson and Zu’s study (2000) which found that the performance of the trade union and the Workers’ Congress has been abysmal in resolving employees’ disputes with the management. Equally, the workers in these two firms apparently lack experience and aspiration in dealing with industrial disputes. As concerned workers (and some middle managers and supervisors) interviewed summarised: ‘to protest [against the management decisions] is to look for death, not to protest is to wait for death’. This observation may be too pessimistic but it reflects the unsettling labour-management issues which have emerged after the change of ownership. For MotorCo workers, as the Technical Manager put it:

The older ones may lack both the stamina and the financial power to find their own way in a labour market of high unemployment. Strong younger workers may be poorly equipped with the skill and knowledge necessary to compete in the labour markets where jobs are available.

Controlled by an authoritarian Managing Director and unprotected by the state or other institutional bodies, all they can do is to hang on to the sinking ship, sailing along silently towards its doomed destination. They are, perhaps, not entirely on their own in their fate.

CONCLUSIONS

Workers in China today face a very different workplace from their predecessors (Warner 2001). The changing nature of employment relations is one of the most sensitive issues associated with the economic reform and the open door policy of China (Leung 1988; Zhu 1995) which requires a changing role of the trade unions. As China’s enterprise reform deepens and unemployment becomes more widespread in the context of a downturn of the Asian Pacific economy, workers will face more adversarial conditions in their employment and welfare issues. The gulf between emerging management practices and the workers’ interests is rapidly widening, an issue with which the out-moded but dominant traditional indus-trial relations system obviously cannot cope. This is when a strong trade union is most needed to protect the workers’ interests at work as well as to assist the enterprise in its successful operation. The recent drive of ownership change (privatisation) by the Chinese Government has created a new form of employ-ment relations which is closer to that found in Western economies. However, the governance mechanism (including the social convention, legislation, and wider institutions that attempt to balance the relations) of the former remains far from being developed, let alone resembling the rigour and dynamics of the latter.

monitoring role in which they are to ‘monitor that the employing units abide by labour disciplines and regulations’ (Labour Law, Chapter 11: Item 88. Also see Warner (1996) for a detailed description of the Labour Law). In reality, this propo-sition rarely materialised. Past and contemporary empirical evidence hardly sup-ports the notion of trade union autonomy in China, whether for the trade unions in the large SOEs or in private or foreign-owned enterprises (Warner 1995; Ng & Warner 1998). Trade union officials in China have in general been considered unfamiliar with the Western style of collective bargaining, ‘with their serious lack of the necessary back-up bargaining resources, skills and capacities’ (Warner & Ng 1999: 307). The role of the trade unions, and more specifically, the trade union officials’ perception of their duties, remain little changed. They still continue to carry out their traditional functions such as organising social events, taking care of workers’ welfare, helping management to implement operational decisions, and coordinating relations between management and workers (Verma & Yan 1995). The trade union officials in China are often in their post not because they are the best candidates for the job, but because they have appeared to be ‘unsuccessful’ in their previous managerial posts, and/or have been sidelined as victims of subtle machinations of political power. As it is extremely difficult to sack an ordinary worker in a traditional Chinese enterprise, let alone a manage-rial member, these managemanage-rial outcasts would normally be housed in the trade union unit. In theory, they are still in positions of authority enjoying similar levels of terms and conditions to that of managerial positions, but in practice they have very little power and any attempt to readjust the power imbalance would be ignored.

in a transitory developing economy such as that of China which is plagued by large-scale unemployment, low skills, low investment, management prerogatives, and ineffective institutional intervention, these problems are even more acute and their adverse impact on the workers and eventually on society may be even more severe. It is, therefore, high time that a new employment relations system was constructed which is compatible with the emerging market economy in China.

REFERENCES

Benson J, Zu Y (2000) A Case Study Analysis of Human Resource Management in China’s Manufacturing Industry. China Industrial Economy4, 62–65.

Bian YJ (1994) Guanxi and the Allocation of Urban Jobs in China. The China Quarterly140, 971–99. Bjorkman I, Lu Y (1999a) A Corporate Perspective on the management of Human Resources in

China. Journal of World Business, 34(1), 16–25.

Bjorkman I, Lu Y (1999b) The Management of Human Resources in Chinese-Western Joint Ventures.Journal of World Business34(3), 306–324.

Child J (1996) Management in China during the Age of Reform.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooke FL (2000) Manpower Restructuring in the State-Owned Railway Industry of China: the Role of the State in Human Resource Strategy. International Journal of Human Resource Management11(5), 904–924.

Cully M, Woodland S, O’Reilly A, Dix G (1999) Britain at Work: as Depicted by the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey. London: Routledge.

Ding D, Warner M (1998) Labour Law, Industrial Relations and Human Resource Management in China: An Empirical Field Study in Central and South China. Working Paper No. 17/98, Judge Institute of Management Studies, Cambridge.

Easterby-Smith M, Malina D, Lu Y (1995) How Culture-sensitive Is HRM?. International Journal of Human Resource Management6(1), 31–59.

Fox A (1974) Beyond Contract: Work, Power and Trust Relations. London: Faber and Faber Limited. Gamble J (2000) Localising Management in Foreign-Invested Enterprises in China: Practical, Cultural, and Strategic Perspectives. International Journal of Human Resource Management11(5), 883–903.

Glover L, Siu N (2000) The Human Resource Barriers to Managing Quality in China. International Journal of Human Resource Management11(5), 867–882.

Gu E (1997) Foreign Direct Investment and the Restructuring of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (1992–1995): A New Institutionalist Perspective. China InformationVol. xii, No. 3, 46–71.

Guest D (1998) Is the Psychological Contract Worth Taking Seriously? The Journal of Organizational Behavior19, 649–664.

Gummerson E (1991) Qualitative Methods in Management Research.London: Sage Publications. Guthrie D (1998) The Declining Significance of Guanxi in China’s Economic Transition. The China

Quarterly154, 254–282.

Heery E, Salmon J, eds, (2000) The Insecure Workforce, London: Routledge.

Hill S, McGovern P, Mills C, Smeaton D, White M (2000) Why Study Contracts? Employment Contracts, Psychological Contracts and the Changing nature of work. Presented to the ESRC Conference: Future of Work III, London School of Economics and Political Science, Policy Studies Institute.

Hodgson G (1999) Economics and Utopia: Why the Learning Economy Is Not the End of History.London: Routledge.

Hoffman C (1981) People’s Republic of China. In: Albert A, ed., International Handbook of Industrial Relations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Johnston M (1999) Beyond Regional Analysis: Manufacturing Zones, Urban Employment and Spatial Inequality in China. The China Quarterly157, 1–21.

Kochan T (1996) Shaping Employment Relations for the 21st Century: Challenges Facing Business, Labor, and Government Leaders. In: Lee J, Verma A, eds, Changing Employment Relations in Asian Pacific Countries. Taiwan: Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research.

Kochan T, Katz H, McKersie R. (1986) The Transformation of American Industrial Relations. New York: Basic Books.

The Labour Law of China(1994).

Leung W (1988) Smashing the Iron Rice-Pot: Workers and Unions in China’s Market Socialism. Hong Kong: Asia Monitor Resource Centre.

Liu T (1989) Chinese Workers and Employees Participate in Democratic Management of Enterprises. Chinese Trade Unions(China) 2, 5–10.

Liu Y (1997) On the reform the small SOEs. Modern Enterprise Herald (China) 8, 38–40. Lu Y (1996) Management Decision-making in Chinese Enterprises. London: Macmillan.

Lu XX (1999) Characteristics of the Labour-Management Relations in the Period of Economic Transition in China. Economic Issues11, 13–15.

Ng SH, Warner M (1998) China’s Trade Unions and Management.London: Macmillan. Piore M, Sabel C (1984) The Second Industrial Divide. New York: Basic Books.

Ruizendaal R (1995) The Quanzhou Marionette Theatre: A Field Work Report (1986-1995). China Information Vol. X, No. 1, 1–18.

Sheehan J (1999) Chinese Workers: A New History.London: Routledge.

Shirk SL (1981) Recent Chinese Labour Policies and the Transformation of Industrial Organisation in China. China Quarterly88: 575–93.

The Third Industry Census(1995) Statistics Ministry of China.

Tsang E (1998) Can Guanxi Be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage for Doing Business in China? The Academy of Management Executive12(2), 64–73.

Tung R, Worm V (2001) Network Capitalism: The Role of Human Resources in Penetrating the China Market. International Journal of Human Resource Management12(4), 517–534. Verma A, Yan ZM (1995) The Changing Face of Human Resource Management in China:

Opportunities, Problems and Strategies. In: Verma A, Kochan T, Lansbury R, eds, Employment Relations in the Growing Asian Economies. London: Routledge.

Wang BB (1997) The Troubled Home-Grown Breweries in China. China National Conditions and Strength8, 32–34.

Wang X (1998) The Beer Industry. In: Renvid J, Li Y, eds, Doing Business With China, 2nd edn. Coopers and Lybrand, Kogan Page.

Warner M (1990) Chinese Trade Unions: Structure and function in a decade of economic reform, 1979–1989. Management Studies Research Paper No. 8/90, Cambridge University. Warner M (1993) Human Resource Management ‘with Chinese Characteristics’. International

Journal of Human Resource Management4(4), 45–65.

Warner M (1995) The Management of Human Resources in Chinese Industry. London: Macmillan. Warner M (1996) Chinese Enterprise Reform, Human Resources and the 1994 Labour Law. The

International Journal of Human Resource Management7(4), 779–796.

Warner M (1997a) Management-Labour Relations in the New Chinese Economy. Human Resource Management Journal7(4), 30–43.

Warner M (1997b) China’s HRM in Transition: Towards Relative Convergence? Asia pacific Business Review3(4), 19–33.

Warner M (2001) The New Chinese Worker and the Challenge of Globalisation: An Overview.

International Journal of Human Resource Management12(1), 134–141.

Warner M, Ng SH (1998) The Ongoing Evolution of Chinese Industrial Relations: The Negotiation of ‘Collective Contracts’ in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone. China InformationVol. xii, No. 4, 1–20.

Warner M, Ng SH (1999) Collective Contracts in Chinese Enterprises: a New Brand of Collective Bargaining under ‘Market Socialism’? British Journal of Industrial Relations37(2), 295–314. Yang M (1994) Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China.New York: Cornell

University Press.

Yu KC (1998) Chinese Employees’ Perceptions of Distributive Fairness. In: Francesco AM, Gold BA, eds, International Organisational Behavior.New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Yuegang Xinxi Bao(Guangdong Hong Kong Information Daily) (1999) The Declining Market for Small Electric Motors. 14th February.

Zhao X, Young ST, Zhang J (1995) A Survey of Quality Issues Among Chinese Executives and Workers. Production and Inventory Management JournalFirst Quarter, 44–48.

Zhu Y (1995) Major Changes Under Way in China’s Industrial Relations. International Labour Review