New Guinea

Preserving Traditional Culture against

Modernity’s Cargo-Cult Mentality

Scott Flower

ABSTRACT: Papua New Guinea is famous for its religious diversity, innovation, and role as the intellectual home of the ‘‘cargo-cult.’’ Contrary to the dominant contemporary trend toward localized and syncretized forms of Christianity, one of the fastest-growing new religious movements in Papua New Guinea is the not so ‘‘new’’ religion of Islam. From 2000–2012, the Muslim convert population grew more than 1,000 percent, and data from fieldwork between 2007 and 2011 suggests that globalization factors, especially missionaries and media, are contributing to increased conversion rates. Transition from traditional life to moder-nity is sparking a range of social and personal crises leading people to search for new religions more closely aligned with traditional, local, cultural and material dimensions. This makes future conversion growth in Papua New Guinea likely.

KEYWORDS: Islam, religious conversion, globalization, cargo cult, kastom

Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 18, Issue 4, pages 55–82. ISSN 1092-6690 (print), 1541-8480. (electronic).2015 by The Regents of the

P

apua New Guinea (PNG) in many respects is a country ideally suited to new religious movements. The effects of globalization1since colonization have destabilized individual and group under-standings of their world and facilitated interest in religious alternatives. PNG is famous for its proliferating new religious movements, which are ‘‘transitional in nature’’ and often referred to as ‘‘cargoist, revitalizing, nativist or just plain new.’’2

The recent growth of Islam in PNG is unique when compared to that of other Pacific countries. Unlike in Fiji, New Caledonia or Indonesian Papua, the growth of the PNG Muslim population is not linked to mass migration of born Muslims. Rather, the conversion to Islam by indige-nous Papua New Guineans has led to an approximate 1,000 percent increase in the PNG Muslim population, from 476 at the beginning of the new millennium to more than 5,000 by 2012.3

Two globalization factors—missionaries and media—have strongly influenced Islamic growth in PNG. Media coverage appears to have had the greater effect by raising local awareness of an alternative to Christianity. The rapid growth of Islam correlates strongly with the spike in media reporting on Islam and Muslims in PNG following the 11 September 2001 (‘‘9/11’’) attacks on the United States along with a signif-icant increase in the number of foreign Muslim missionaries visiting the country.4Conversions, however, usually are cemented through

person-to-person Islamic missionary efforts. In fact, 75 percent of the 73 converts I interviewed between 2007 and 20115 claimed that interactions with

missionaries were among the most influential reasons for their conver-sion. Missionaries in PNG are exclusively Sunni and belong to the trans-national Islamic revivalist group known as the Tablighi Jamaat, or Jamaat al-Tablighi. These missionaries are residents or citizens of Australia, pre-dominantly from Sydney and Melbourne, and mostly of Pakistani, Indian or Bangladeshi origin.6

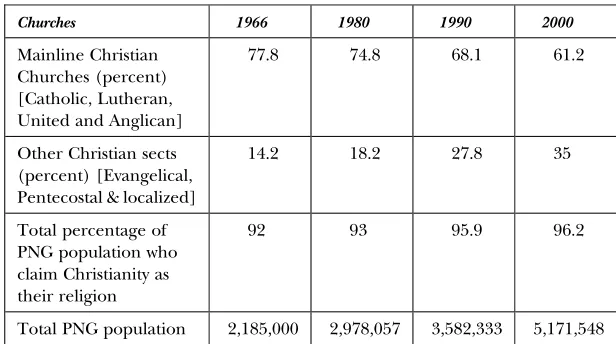

There is a general consensus that dramatic religious change in PNG is underway partly as a response to a range of crises resulting from globalization.7The scale of religious change in PNG is large. The most

notable trend is the declining popularity of mainline Christian churches (Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran and United Church), dominant during the colonial period but now declining in real terms. Over the same period (1996–2000), conversions to more fundamentalist Pentecostal, evangelical and charismatic Christian churches8 have increased from

14.2 percent to over 35 percent, and other revivalist forms of syncretized religion such as cargo cults have grown as well.9Papua New Guineans

often publicly declare theirs to be a Christian country, which seems reasonable: available statistics show over 96 percent of the total popula-tion is affiliated with a Christian sect.10This effectively pits Christianity

despite the government threatening to ban Islam and a range of preju-dice and even violence against new Muslim converts,12indications

sug-gest that Islamic conversion growth rates will persist.

All the fieldwork participants discussed in this article are indigenous Papua New Guineans and converts to Sunni Islam (no Shia Muslims were discovered). They were interviewed using a standardized pre-set questionnaire to enable analysis of response variation. Interviews fol-lowed a verbal information and consent process, with most held in pri-vate rooms at local Islamic centers in Port Moresby and Lae, as well as in rural centers. Interviewees were self-selecting in that they requested to be interviewed following my formal introduction as a researcher by local senior Muslims.

There are two predominant themes among the narratives of indige-nous converts to Islam presented here. First, all 73 converts I interviewed stated that Muslim beliefs and practices were closer to their traditional custom (kastom) than Christianity, and this was the main reason for conversion to Islam. A large number also believed that their ancestors must have been Muslim prior to colonization and the adoption of Christianity; and, in alignment with research by Aloysius Pieris and Dornal Dorr, they based this assertion on the claim that traditional religious perspectives were much closer in similarity to Islam despite Christianity sharing some similarities with traditional religion.13

Second, they viewed Islam as a well-established global religion that pro-vides a means of countering the failure of Christianity and cargo cults to deliver material or social prosperity.

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE NEW, AND BACK TO THE OLD

Papua New Guinea has a population of more than 6.5 million and is predominantly comprised of people of Melanesian descent, with a small minority having Micronesian or Polynesian heritage. PNG is a highly fractioned country with more than 800 known indigenous languages and three official languages—English, Tok Pisin (Pidgin) and Hiri Motu. Approximately 85 percent of the population continues to live traditional, village-based lives dependent on subsistence and small cash-crop agriculture. The remaining 15 percent live relatively modern urban lives in Port Moresby, Lae, Madang, Wewak, Goroka, Mount Hagen and Kokopo.14

German colony of New Guinea using military force at the outset of World War I. Japan and the United States took part of the country during World War II. In 1946 the United Nations approved Australia’s administration of the island, which continued into the early 1960s. Between 1962 and 1973 there was an incremental transition from direct colonial rule to representative self-government, with the country finally becoming independent on 16 September 1975.

InventingKastom

A congruence of belief, value, symbol and ritual in PNG traditional religions facilitated Papua New Guineans’ conversion to Christianity, suggesting cultural congruence was a major factor leading to conver-sions to Islam in PNG today. This view assumes that religious concepts and emotions are more difficult to relate to when a convert lacks specific religious tradition or cultural conditioning.15 Knowledge of traditional

religion and a strong familiarity with Christian religious concepts is more likely to facilitate conversion to Islam. Particularly important is a con-vert’s comparison of Christianity—shared reverence for God’s Word in holy books (the Old Testament and Gospels), prophets (Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, on through to Jesus), and religious messages and sim-ilar historical narratives in Christianity and Islam. This finding is not surprising given that converts to fundamentalist Christian sects in Melanesia often have good knowledge of the Christian Bible, with many people able to cite numerous passages directly.16

These factors immediately legitimize Islam as a religious alternative but, unlike mainline Christianity, Islam has clear and explicit social practices similar to traditional religion and culture in PNG, and congru-ence in these aspects is particularly important. There are similarities between each of the four religious orientations discussed here—tradi-tional, mainline/colonizing Christianity, Pentecostal/Evangelical Christianity, and Islam. The differences among them, however, are more important,17including their systematic ordering of power, and the

iden-tification and moral relevance of power in managing both the beneficial and dangerous aspects of human life.18

Importantly for theory, and in support of the view of Clifford Geertz,19

Islamic conversion in PNG involves people from particular antecedent religious cultures thinking about imported ideas that a religion such as Islam brings. The PNG case also supports Robin W. G Horton’s view that conversions occur within a dynamic contextual superstructure of religious change that can be understood only in terms of existing tendencies in a specific changing society.20Muslim converts’ expectations of their new

religion parallel the expectations of their old religion,21and in this light

cultural congruence: ‘‘The difference is that Islam brings us back to our traditional values like our forefathers, and [Muslims] practice with respect for customs and traditions, and this is what makes me become Muslim.’’22

While religious and cultural congruence cannot be over-emphasized, a degree of caution must be exercised in generalizing about the variety of religious beliefs and cultural practices deeply ingrained through orally transmitted traditions in Papua New Guinea—kastom—that shape religious meaning, ritual and conversion. Many researchers argue that conversion will not occur unless it corresponds with the convert’s pre-existing ideas about truth or meaning, with new beliefs being under-stood through the old.23 In this sense continuity is a central referent

of tradition.24 Joel Robbins has argued that the issue of continuity in

religious belief and practice is under-theorized in respect to Christianity; however, the importance of tradition and continuity of practice referred to assunnais much stronger in Islam, reflected in the greater volume of research on traditions within Islam.25

The body of literature on religion and culture in PNG is large, diverse and highly complex, and retrospective analyses of kastomrisk romanti-cizing the traditional past.26Without descending into a comprehensive

treatment of PNG religion and culture, I examine only those elements of congruence in the religious and cultural literature relevant to under-standing Islamic conversion.27

For many years, scholars of PNG constructed an ideal type of tradi-tional religion that failed to represent the diversity of religious practice and belief during colonization.28Despite the need to recognize

irregu-larities in PNG religious patterns, however, many ritual forms are con-sistently present throughout most of PNG, such as strict relational prohibitions (men/women, kin, marriage), funerary practices, and behavioral regulations (food, hunting and other social mores). Although changes to traditional religions occurred prior to coloniza-tion, the more distinctive features of existing traditional religions per-sist.29 Research continues to show many common themes across tribal

religions in PNG, including some aspects of tribal law, initiatory rituals, and cyclical celebrations.30 I argue that these general features—more

congruent with Islam than with Christianity—appear to be facilitating contemporary conversions to Islam.

LESSONS FROM THE DISSEMINATION OF CHRISTIANITY IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA

Though the practice of most traditional rituals ceased with the arrival of Christianity and some new beliefs were adopted, most analysts see the underlying spirituality of Christianity as rooted in the primal cosmology32

associated with traditional religion.33A cosmology is not pulled out of the

air to suit the convenience of a community but rather is conditioned by its unique history of social and psychological dimensions.34To understand

this situation and why Islam is attracting converts, one must examine the way that locals took up Christianity and how Christian missionaries pro-moted it.

Apart from material influences discussed below, Christianity was received with enthusiasm because it was seen by many indigenous con-verts as a name for the religion they already knew.35 People viewed

Christian knowledge as having belonged to their own ancient traditions handed down before the arrival of Europeans.36

The colonization of PNG, while confronting for locals, was reason-ably limited in scale. Apart from coastal areas, colonial rule inland was relatively shallow, and many highland regions were only formally colo-nized in the 1930s and 1940s. From the late-nineteenth century, Christian missions played a major role in pacifying and influencing the indigenous peoples. Colonial officials ruled in ways that often were per-sonal and violent rather than bureaucratic, but their power and territo-rial reach was relatively limited.37

Christian missionaries were not in a position, and did not aim, to remove or destroy the entire traditional religious culture; rather, they endowed ‘‘preexisting traditions with Christian meaning,’’ colloquially referred to as ‘‘grafting the new vine to old, well established roots and stumps.’’38Christian churches simultaneously and deliberately put a stop

to many traditional religious rituals, but they drew selectively from tra-ditional religious beliefs and concepts to enhance their own evangeliz-ing, particularly among highland cultures.39Christian missionaries were

advised to make greater use of the Old Testament as being more rele-vant to the cycle of seasons for Melanesians, who lived close to the soil.40

Missionaries in Melanesia continue to integrate Christian beliefs into traditional cosmologies.41

Religious and Cultural Congruence

This makes Islam particularly attractive in the context of widespread confusion about religion and social chaos in PNG.

Traditional religions in Papua New Guinea were not centered on issues such as how to come to terms with the sinful nature of human beings. Rather, salvation was seen as fulfillment in every aspect of life— health, success, fertility, respect, honor or influence over others. Ultimately, salvation was the absence of negative forces including sickness, death, defeat, infertility or poverty.42In Islam, more than in Christianity,

‘‘the quality of the relationship with God depends on fulfillment of duties by the follower, and the practice of ritual, the following of Islamic custom, and the observance of Islamic law (Sharia).’’43If mainline churches

con-tinue to be perceived as failures in delivering social order and prosperity, the greater congruence of Islam withkastommay lead to increased con-versions to Islam. This prediction fits the broader religious trend in PNG for people to move to stricter Pentecostal and evangelical forms of Christianity.

In the interviews converts mentioned many aspects of congruence between Islam andkastomin Papua New Guinea. The most strongly evi-dent included: belief in a monotheistic God, religion as an integrated element of life, and strict rules of law and justice. The most overarching similarity was that Islam, like kastom, was a ‘‘complete way of life’’ with detailed rules governing religious and social conduct. According to Saeed, a 24-year-old male: ‘‘Islam gives perfect guidelines for life, like if I want to get married and how I should raise my kids up. Everything is there; it’s like a manual to human beings. All that we need is there in Islam.’’44

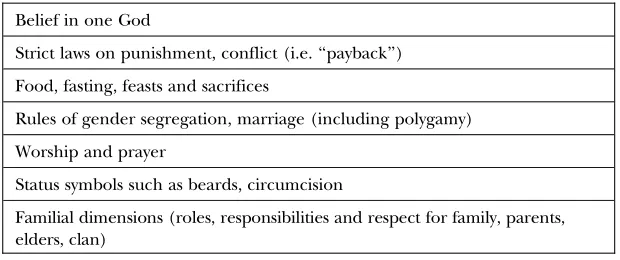

Islamic scholarship and the Qur’an verify the similarities claimed to exist between Islam andkastom.45Figure 1 shows the aspects of religious

and cultural practices in order of most frequent mention in the interviews as being closer to Islam, and/or not promoted, accepted or approved by Christianity or Western ways:

Belief in one God

Strict laws on punishment, conflict (i.e. ‘‘payback’’)

Food, fasting, feasts and sacrifices

Rules of gender segregation, marriage (including polygamy)

Worship and prayer

Status symbols such as beards, circumcision

Familial dimensions (roles, responsibilities and respect for family, parents, elders, clan)

SOCIAL AND PERSONAL CRISES FACILITATING CONVERSION

History provides numerous examples of how religion can influence members of a society to adhere to values, principles and rules deemed appropriate for a specific social entity.46In societies where religion and

culture are more unified, evidence suggests that criminal and deviant behavior is significantly lower despite (in many cases) a lack of Western institutions such as police and courts.47In this sense, it appears rational

and logical that PNG converts believe that conversion to a strong reli-gion such as Islam is a means of returning to previous religious values and attaining order.

Importantly, most ‘‘Papua New Guineans don’t necessarily want a merciful god. . .they want a powerful god who has the power to secure happiness for the follower on earth.’’48 Islam possesses a defined and

strict approach to life and promotessalat (prayer) five times daily to ‘‘prevent the commitment’’ of evil, ‘‘prohibit obscenity, wickedness and evil,’’ and help followers ‘‘be free from all diseases’’ and make them ‘‘healthy and strong.’’49This view is supported to a degree by empirical

evidence suggesting that rates of violence and overall crime are lower where larger proportions of the population are actively religious and apply religious moral values that deter followers from engaging in devi-ant behavior.50

Weak laws and, more specifically, weak law enforcement in PNG are stimulating widespread public demands for the introduction of stricter laws with more severe punishments. This sentiment, based on the cultural tradition of ‘‘payback,’’ is leading even non-Muslims to call for Islamic law. Speaking in Parliament in 2007, Prime Minister Sir Michael Somare pointed to rapidly increasing problems maintaining law and order:

Our societies are now deteriorating and attitudes of the people are changing. For those people who pack rape [gang rape], we should bring in the legislation to impose mandatory corporal punishment of public flogging. Muslims are doing it and it works. We pretend to go for church services with our Bibles but we still tell lies. I think it is time we got tough. Capital punishment and public flogging should be exercised now or we should give life sentences to serious lawbreakers. Thieves should have their hands chopped off.51

sharia). Numerous letters to editors of national newspapers I have read in archives in Papua New Guinea suggest that awareness of and support for strict Islamic laws in PNG appear to be reasonably widespread among both Muslims and non-Muslims.

Some in PNG specifically request Mosaic laws while others call for sharialaws, both of which are straightforward and demand compliance. One letter to the editor suggested, ‘‘six Saudis should be brought to PNG to mete out the punishments.’’52 This general view was shared by most

Muslim converts I interviewed, including Yusuf, a 48-year-old male:

In PNG the law is very weak. Killing is there, raping is there, adultery is there but they don’t impose the laws. Under Islamic law you know everything will improve. The country will be peaceful because if some-body steals they cut off his hand. The people will know that if I steal I will lose my hand so the stealing will stop.53

In May 2013 the PNG government responded to public support for harsher punishments by reinstating the death penalty.54 Some Muslim

converts believe that increasing crime and social chaos are the result of political crisis resulting from external influences. The need for religion to resolve this crisis was clearly expressed by 24-year-old convert Abu Bakr:

Australia came here and brought their law. The law was written by Australians themselves because at the time we didn’t have any lawyers.. . . They came in and said, Somare, you’re going to be signing and be the first Prime Minister. Our laws were designed by somebody from outside, so we have problems. I look at Islamicshariaand as I studiedshariaand looked at Muslim countries and I discovered that it’s different. For example here in PNG, we have the political integrity bill but this doesn’t really work. It just protects the interests of political leaders.Shariawill not just protect the interests of any leader. Everybody. . .is equal insharia. It is the lawful court of Allah himself. Because when people make laws for the country, they do it in the interests of their leader.55

Another form of social crisis prompting conversions is the loss of respect for parents and elders. For many years, tribal leaders have spo-ken of deteriorating cooperation and social control of youth.56Islam has

very strict rules on how one should treat parents, relatives, elders, dis-tinguished persons and even non-Muslims.57 According to Saeed: ‘‘In

The Ideal Muslim[a book distributed by missionaries] it makes clear that your neighbor has rights over you, your wife has rights over you, your kinsman has rights over you. You have to balance this in life.’’58

seen as chattel to be owned by men, came third in importance to men after pigs and land. Christian promotion of women’s equality (i.e. changes to marriage law, polygyny, and gender segregation) has disor-iented traditional gender relations and is seen by many male converts as a major cause of social problems such as increased promiscuity, premar-ital sex, rape, increased sexual disease and domestic violence. According to Mikail, a 36-year-old male:

In our kastomthe girl stays with the parents and family and we give them a man to marry. They don’t go to disco or public places and that’s why our traditional customs are important. Before, a woman had to be a virgin before she got married but today this doesn’t happen. It’s a sad story. Now we have babies with no father, unmarried sex and an AIDS epidemic because we have been weakened by the Western missionaries.59

All female converts I interviewed saw the removal of gender segrega-tion as a negative effect of Christianity and Western values. For female converts, Islam provides the means to redress this perceived problem, for example for Musinah, a 40-year-old female: ‘‘Wearinghijabcan protect women. From my point of view, women’s body is sensitive to men. If men get bad thoughts of woman because of their dressing then it’s not good.’’60

Women’s involvement in religion and religious ritual, particularly among fundamentalist churches, also accentuates this gender crisis.61According

to 34-year old-Nadia:

I see the job of a woman is different from the men. It’s washing clothes and cooking food and sweeping and cleaning the house, nursing chil-dren. These are all a woman’s job. I cannot go and do man’s work like breaking firewood or building a house or digging a drain, cutting bushes or building house. All these are a man’s job.62

The Christian emphasis on monogamy in PNG has also damaged the traditional practice of polygyny. Today, men continue to take multiple wives in order to secure cheap labor, extend networks, strengthen inter-group alliances, raise sons to replace them, grow the population, and attain social status. The practice is widespread in the Highlands, and in the Western Highlands province more than 50 percent of all men are polygynists.63Half of all converts I interviewed

said this contributed to their conversion to Islam. Most churches (particularly Pentecostals, evangelicals and Seventh-day Adventists) insist that only monogamists can join and attend church, although some have a policy of accepting men who already have multiple wives with the caveat that the men cannot progress to baptism.64 Despite

(especially among tribal/clan leaders) and is claimed to be the way of Highlands ‘‘big-men.’’

Christian opposition to polygyny and its associated guilt and stigma contribute to Islamic conversion for a number of reasons. Denial of hav-ing multiple wives limits men’s ability to improve their political and eco-nomic position via traditional means, and denying baptism effectively denies followers a path to salvation. Male convert Wassim, age 22, put it this way:

The Christian principle is one-to-one, so [men] can have no more than one [wife] and they oppose polygamy. This is a problem to us, because when you see some places women outnumbered the men and it’s a prob-lem. Nowadays we realize that when Christians avoid women from getting married in polygamy, these women go out and become sexual objects with money, becoming prostitute and lots of problems are related to this. Actually polygamy was already practiced by our ancestors and was a very important part of society. Sexual relations is a right given by almighty God, and our ancestors were well organized and they knew the impor-tance of this by controlling marriage and having polygamy in society it was very peaceful. Sex is a desire like eating, drinking or sleeping. Sex for every adult is a must that needs to be fulfilled so it’s no problem [in Islam]. So when the Christians say you can only marry one wife, lots of problems come now.65

Personal crises also are significant motivators to conversion. Sixty-nine percent (two women and 34 men) of the Muslim converts I interviewed experienced one or more types of personal crisis prior to conversion, most commonly involving alcohol, drugs and violence. This finding generally aligns with the literature suggesting that most individuals experience some type of personal turmoil prior to religious conversion.66 Each

form of personal crisis was related in some way to the wider context and appeared to be exacerbated for urban converts in Port Moresby and Lae. For converts in PNG, conversion to Islam helps relieve or manage these personal crises.

According to Ali, age 28: ‘‘I was involved with alcohol and gambling and womanizing, and this creates a lot of problems that I don’t want. This is one reason why I become Muslim.’’67Likewise for Hussein, age

25: ‘‘I was into alcohol and drugs, mostly marijuana. I would stop cars and pull the drivers out. I used to get guns and do bad things.’’68And

35-year-old Ruqaiya explained:

The Same, But Different

For the converts I interviewed, prior knowledge of Christianity was by far the largest factor in their conversion. A detailed knowledge of Christian theology, doctrine and the Bible meant they already had a con-ceptual framework for understanding Islam, encountering Islamic liter-ature or interacting with Muslims. This influence of religious knowledge was greatest among the nine Muslims who had received formal religious training in Christian churches. Deeper or more detailed knowledge of Christianity heightened their concern and anxiety about Christianity and enabled them to see more theological contradictions or illogical doctrines, further reducing their belief that Christianity was the true religion.

Converts often discussed similarities between the Qur’an and the Bible, such as the prophets, content of the Old Testament, and religious values and principles. As explained by 32-year-old Ibrahim:

When I was young I was [Seventh-day Adventist]. I learned a lot about the Bible, everything SDAs do Bible comes first.. . .When I looked back through the Old Testament I was thinking, Islam is saying this, that there is one true God and nobody can be a partner to God. This is the greatest sin that people do this. A human or anything else should not get the same respect as God himself.. . .It’s the greatest sin but people say Jesus is the one. So I read many books and found out that Islam is true. God gave the Ten Commandments and said put no other god before me as the first one and if there was meant to be other gods then he would have men-tioned it in the Ten Commandments, but there is nothing else.70

Another significant factor was the absence of time constraints. Among the sample population, 70 percent were either unemployed or under-employed at the time of their conversion, meaning they had free time to pursue a new religious option.

MORAL, NOT MATERIAL, PURSUITS: ISLAM AS COUNTER-CARGO CULT

When Europeans arrived in PNG with material and technological wealth, many Papua New Guineans believed either that the new arrivals were their dead ancestors or possessed special religious devotions that gave white people their goods and power. Conversions at the time pri-marily stemmed from people’s search for material equality.71 During

not unique to PNG and Melanesia; the pattern of missions and money has also been identified as a cause of conversions in much of Africa and Southeast Asia.73Accordingly, some argue that locals viewed conversion

to Christianity simply as the rot bilong kago74 (road to cargo or new

goods) and converted less for theological reasons than for practical purposes.75Based on the literature, some degree of material influence

should be expected in all conversions in PNG. Certainly, the rise in Pentecostal popularity in PNG is related partly to the focus on material wealth and the prosperity gospel.76However, it is incorrect to conclude

that conversions to Christianity and now Islam are simply opportunistic attempts to obtain cargo. Indeed, for many years scholars have empha-sized that PNG new religious movements are not always (or only) cargo-cultist.77

Materialism, however, holds great attraction for Papua New Guineans,78and the relationship between wealth and religion is

embed-ded in PNG traditional religious ontology, which sees religion as unified, with no partition between material and spiritual. Traditional lifeways accentuated the importance of religious belief and practice to deliver people from trouble and provide wealth and health ‘‘in the present as well as in the hereafter.’’79 Consequently, many argue that PNG new

religious movements should be seen as salvation movements following the responses of traditional cultural and religious sentiments to chang-ing social, cultural and/or religious environments.80 In PNG,

particu-larly, conversion to Islam must be examined through this wider lens. Christian churches provide most of the social welfare services in PNG, thus it is reasonable to assume that it would be difficult for people to leave Christianity if these services are accessible only to Christians. Offering material goods as an incentive to convert to a new religion is not an artifact of earlier times. Seventh-day Adventism, the fastest grow-ing Christian denomination in PNG today, draws converts by ‘‘promisgrow-ing or giving them clothing and money.’’81Over the last twenty years,

how-ever, government subsidies to churches have diminished, resulting in a significant contraction—and in some cases closure—of Christian-operated social welfare services (kago), particularly in provinces (such as Chimbu and Oro) in which Islam is seeing strong growth.82 This

reduction has occurred within the broader context of PNG welfare cut-backs from the late 1990s into early 2000.83 This coincides with the

period leading up to the surge in conversions to Islam that commenced in late 2001. It might be hypothesized that if Muslim groups provide social welfare as part of their proselytizing strategy, conversions to Islam may be likely. My observations of PNG Muslim converts’ socio-economic position confirm that, at least initially, material influences are present.

subsidized school fees, potential to travel overseas for Islamic education or conferences, and very limited healthcare assistance. When I asked converts whether they were converting to Islam forkago, most denied material reasons, even giving the impression that conversions based on material desires carried negative connotations. Yet, comments through-out the interviews (combined with socio-economic backgrounds) sug-gested that material factors were initially at play. Half of the converts interviewed said material concernsmightbe a reason why some people convert. Three converts did confess they had converted to Islam for material things—two for food and a place to sleep, and the other for education. Interestingly, all three said that once they converted they realized that material opportunities were limited but decided to remain Muslim because of the teachings and doctrines. This aligns with the view of some PNG converts that the material and spiritual aspects of life are united.

Converts’ family and tribal members reportedly are also intrigued by material aspects and often ask converts what material things Islam provides. During an informal discussion with a group of female converts, I was told that the provision of social welfare by the Islamic Society of Papua New Guinea was needed (though not yet provided) for converts to practice theirdı¯n(religion) effectively.

Despite the initial importance of material factors, for most converts interviewed this motivation declined over time and gave way to an inter-esting paradox. Islam appears to become a coping strategy for many converts through its promotion of material simplicity, economic inde-pendence and self-sufficiency, themes that resonated strongly with con-verts disappointed in Christians’ ability to meet their material and spiritual expectations. Islam is promoted on the basis that one must work hard to obtain material comfort in the physical world, and that moral concerns are the most important for salvation. In the words of 27-year-old male convert Asad:

I want to live a simple life, just stay simple and do mysalat. I must work hard and struggle in order to live. In thehadiths it says you do not stay for nothing. One of theSahaba[the ‘‘companions’’ who were the first fol-lowers of the prophet Muhammad] told a story about a poor man. The Prophet Muhammad gave him money and said buy an axe. When he did the man started chopping firewood and made money which shows we must do whatever we can. We can’t rely on other people and expect things to come, like waiting for cargo. We need to work and be inde-pendent. That’s how I am different as a Muslim.84

DISCUSSION: THEORIES OF RELIGIOUS CONVERSION

Traditional tribal societies in Papua New Guinea have undergone an incalculable degree of cultural, social, political and religious change as a result of colonization, decolonization and modernity. In precolonial societies, religion was an integral and unifying dimension of an indigenous person’s life, and culture was virtually indistinguishable from religion.85

The foundations of belief, social order and knowledge in traditional PNG tribal societies have been severely affected by globalization.

Traditional foundations became devalued and began to disappear as a result of the twin invasions of Christianity and Western modernity.86

Christian missions, Western education, loss of traditional knowledge, urban migration and its weakening of existing social bonds, improve-ment in women’s status, and traditional wealth and exchange systems have given way to a monetized economy. Inevitably, Christianization and colonization have created tensions between traditional and modern value systems87 thereby creating opportunities for religions that offer

alternatives.

Globalization theories of religious conversion provide numerous ex-amples of how colonization and decolonization, international migra-tion, improved communications and travel have stimulated religious revival and facilitated the spread of Christianity and Islam.88A key claim

of globalization theory is that converts are attracted to a different reli-gion because they view it as modern or new, especially if its narrative suits people who feel dispossessed or displaced, or desire spiritual renewal.89

Indeed, postcolonial theorists argue that earlier conversions to Christianity and Islam in Africa, Asia, and North and South America were a colonization of people’s spirituality by force rather than choice.90

Christianity was ‘‘installed at the national level in PNG. . .as a tradition-alized state religion by a departing colonial power and local elites under colonial influence,’’ even though Christianity today is ‘‘often used as a key vehicle for the expression of individual and collective identity and indigenous spirituality.’’91From this perspective, change to the religion

instilled through colonization or a syncretic blend of old and new can be anticipated as a form of indigenous resistance and innovation.

It is worth noting here that Islam’s global spread more often targets societies than the state, calling to people’s spiritual needs and ‘‘illustrat-ing multiform expressions of religious practice and discourse that link individuals and groups to larger social movements.’’92

interaction and agency of both proselytizers and converts. The same globalization processes that brought greater outside interaction and mobility to small, traditional African communities are also expanding the religious reality in PNG. Local understandings of the wider world are being formulated through the expansion of existing myths, symbols and rituals to align local realities with global events and knowledge.93

The growing body of research that applies globalization theory to the growth of fundamentalist Christianity in PNG suggests that conversions to new religious alternatives is occurring as a result of individuals’ efforts to understand and explain globalization and modern concepts.94These

studies in Papua New Guinea align with Horton’s theory and adequately describe how Muslim converts also attempt to reconcile local and global knowledge in a two-way process that allows them to attach local signifi-cance to global events and vice-versa. Based on data obtained through my fieldwork, it appears that in PNG the single biggest effect of global-ization on religious affiliation has been secularglobal-ization,95 which has

pierced the ‘‘sacred canopy’’ of religion96that previously was the center

of social life, resulting in religious culture becoming more diverse and religion losing its social authority.

Despite globalization and secularization, however, many people in PNG still see religion as an integral part of the cultural system,97and this

fits nicely with Islamic philosophy. Papua New Guinean philosopher Bernard Narokobi (1937–2010) once explained this dominant local per-spective, claiming that people in PNG still do not differentiate between religious and non-religious experience and have a total and living encounter with the universe.98This view is shared globally by Muslims;

interestingly, pre-Reformation Christianity also held such a view.99

New Christian Sects

The response to secularization in Papua New Guinea has been sim-ilar to that in most other parts of the world, with a rise in conversions to fundamentalist religions, particularly Christian and Islamic forms, a sce-nario that paradoxically contributes to even greater secularization.100As

presented in Figure 2, over the last 40 years in PNG there has been a pro-liferation of new Christian groups, with the number currently exceeding 200. Where it was common for earlier communities in PNG to have only one church, ‘‘today it is quite common for people even of villages in remote areas with populations of fewer than 500 souls to be co-existing with a variety of new religious groups and churches.’’101Figure 2 shows

the populations of ‘‘mainline’’ and ‘‘other’’ Christian churches from 1966 to 2000.102

involving arson, assault and murder.103In the past, some scholars argued

that Christian churches provided the basis for national unity in PNG,104

but it is hard to see such unity against a background of increasingly complex divisions. Papua New Guineans themselves commonly hold that

Christianity in PNG is characterized by disunity, bitter inter-denominational conflicts, and the endless intrusion of man-made customs in the praise and veneration of the almighty and that, in the hands of feeble men Christianity has become fragmented into a thousand shards, like rem-nants of a shattered stained glass cathedral window.105

A number of PNG Christian leaders have highlighted disunity and growing secularization as a major problem, stating that ‘‘churches are highly suspicious of each other and can only find unity in matters that are of no importance one way or another.’’106The most common

disputes appear to involve resources, internal religious institutional politics and theological issues.107 Some PNG church leaders claim

sectarianism is increasing because Christian churches are corrupt,108

while others assert that Christianity should be ‘‘put on trial’’ because ‘‘many who go to church also drink, smoke, and [have] immoral relationships.’’109

Theological disputes often stem from conflicting interpretations of the Bible, splitting some of the stronger Christian groups such as the Seventh-day Adventists.110 This trend occurs in PNG because of the

Bible’s growing importance for people. Christianity in Papua New Guinea shares features of fundamentalist Pentecostalism and evangeli-cal Christianity globally in terms of emphasis on the Bible—and its literal interpretation—as the highest religious authority.111 Bruce M. Knauft

has highlighted this tendency of biblical literalism in PNG, quoting Churches 1966 1980 1990 2000

Mainline Christian Churches (percent) [Catholic, Lutheran, United and Anglican]

77.8 74.8 68.1 61.2

Other Christian sects (percent) [Evangelical, Pentecostal & localized]

14.2 18.2 27.8 35

Total percentage of PNG population who claim Christianity as their religion

92 93 95.9 96.2

Total PNG population 2,185,000 2,978,057 3,582,333 5,171,548

fundamentalist Christian converts as saying, ‘‘the Bible is not just the talk of the church leaders, but the talk of God himself. You must read the Bible in order to understand.’’112All types of Islam and its four schools

of jurisprudence believe the Qur’an is literally the word of Allah (God), and Muslim missionaries in PNG promote this fact as a divine advantage over Christianity. Despite the fundamentalist Christian claim that bibli-cal authors wrote with the finger of God, the primary difference here is that the Christian Bible is comprised of contributions from different human authors whereas the verses of the Qur’an were revealed by a sin-gle individual. Even though Qur’anic verses were memorized and writ-ten down by a number of persons, another single individual gathered and compiled them to make the Qur’an.

The proliferation of fundamentalist Christian churches in Melanesia may be based on their adherence to ‘‘strict laws that promise individual certainty’’ or provide a ‘‘shortcut to certainty.’’113Knauft has noted that

Christian fundamentalism appeals to many in PNG because of its reac-tionary proclamations regarding the global rise of immorality as well as excessive wealth and greed, and the call for personal suffering and abnegation of new ways, which are best described as ‘‘anti-modern rather than modern.’’114 Both Joel Robbins and Holger Jebens argue

that fundamentalist churches in PNG are notable for their emphasis on self-control, support for certain limited forms of gender equality, and a very firm rejection of indigenous religious traditions.115

My fieldwork interviews and reviews of news media in Papua New Guinea support Manfred Ernst’s view suggesting that Islam is appealing and growing at a similar rate to fundamentalist Christian churches for similar reasons. Three-quarters of the converts I interviewed claimed that a major appeal of Islam was its strict rules. Many also mentioned a desire for widespread conversion to Islam in PNG as a means of bring-ing peace, stability and greater law and order to the country.

Like fast-growing fundamentalist Christian churches, Islam has strict prohibitions against alcohol, tobacco and pork, as well as strong norms of worship, Qur’an study programs, (literal) Qur’anic interpretation, and fasting. These laws provide a sense of clarity and security in a chang-ing social environment. In this sense Islam is similar to fundamentalist churches, which are seen as actually practicing religion rather than merely possessing acceptable religious beliefs. Mikail explained this pat-tern of religious change:

Muslims in PNG are widely perceived as morally strict and devoutly religious. Even the Secretary of the PNG Council of Churches has said that ‘‘Christians have much to learn from their Muslim brothers and sisters who display conviction in their faith and an enthusiasm for prac-ticing it.’’117

CONCLUSION

Islam in Papua New Guinea is growing primarily as a result of cultural and religious similarities between Islam and traditional religions, and as a response to widespread social change and resultant personal and per-ceived social crises. The growth of Islam, however, is a only a small part of a much bigger trend of dramatic religious change underway in the country, which is marked by the decline of membership in Christian denominations associated with colonialism (Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran and United Church) and the surging growth of more funda-mentalist Pentecostal, evangelical and charismatic Christian churches.

Moreover, media coverage of 9/11 made people aware of a religion other than Christianity, introducing the potential for conversions. Upon researching Islam, visiting local mosques or talking with foreign Muslim missionaries, an increasing number of people decided to convert. At the same time, the conversions seemed to be linked largely to cultural and material factors. Material incentives influence initial conversion to Islam, but do not significantly drive growth to the degree suggested in the literature on religious conversion and the historical presence of cargo cults in PNG. In postcolonial PNG, Islam seems to be a philosophy that enables Papua New Guinean Muslim converts to cope with per-ceived material deprivation and the failure of previous religions to deliver material wealth. Indeed, contrary to the promises of prosperity touted by growing Pentecostal churches in PNG, the Tablighi Jamaat missionaries teach a less comforting reality that Muslims must work and struggle to obtain material wealth, and that even if wealth is attained only a moral life is essential for salvation.

and converting on the basis of which one in their view has the closest alignment.

Future growth of Islamic conversions in PNG is likely given the influ-ence of cultural and material factors of conversion and the trajectory of change from traditional to modern worlds. The resultant increasing range and intensity of social and personal crises emanating from social transformation will continue to motivate people to search for new mean-ings and social connections in their lives. The not so new religion of Islam offers to Papua New Guineans a relatively new source of beliefs and practices that reaffirm old values in a new globalized world.

ENDNOTES

1

For the purpose of this article, globalization is defined as a historical process of change and ‘‘the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa.’’ Quoted in Anthony Giddens,Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age(Cambridge: Polity, 1991), 64.

2 Garry W. Trompf,Religions of Melanesia: A Bibliographic Survey(Westport,

Conn.: Praeger, 2006), 32.

3 For a complete presentation of Islamic conversion statistics and geographic

spread in Papua New Guinea, see Scott Flower, ‘‘The Growing Muslim Minority in Papua New Guinea,’’Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs32, no. 3 (2012): 1–13.

4 For a comprehensive account of the causes and process of Islamic conversion

in Papua New Guinea, see Flower, ‘‘The Growth of Islam in Papua New Guinea: Implications for Security and Policy,’’ Ph.D. diss., Australian National University, 2010.

5

Although every convert interviewed chose an Islamic name following their conversion, aliases are used to protect their anonymity.

6

Flower, ‘‘Growth of Islam in Papua New Guinea,’’ 232–41. For background to the Tablighi Jamaat and its presence in Australia, see Jan Ali,Islamic Revivalism Encounters the Modern World: A Study of the Tablıˆgh Jamia’at, Studies in World Religions 2 (Delhi: Sterling, 2012).

7 Manfred Ernst, ed.,Globalization and the Re-Shaping of Christianity in the Pacific

Islands(Suva, Fiji: Pacific Theological College, 2006); Malcolm Crick, ‘‘Three Ethnographic Examples of Resistance, Change and Compromise,’’ inGlobal Forces, Local Realities: Anthropological Perspectives on Change in the Third World, ed. Bill Geddes and Malcolm Crick (Geelong, Victoria: Deakin University Press, 1997), 257–318.

8

9 Philip Gibbs, ‘‘Papua New Guinea,’’ in Ernst,Globalization and the Re-Shaping of

Christianity in the Pacific Islands, 92–98.

This article does not seek to examine the syncretic nature of Islam or Christianity in PNG. The degree of religious syncretism in Papua New Guinea and the complex interrelationships between old and new religions render the determination of distinctions of mutual influence artificial. See Holger Jebens, Pathways to Heaven: Contesting Mainline and Fundamentalist Christianity in Papua New Guinea(New York: Berghahn Books, 2005). Also see Charles Stewart and Rosalind Shaw, ed., Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis (London: Routledge, 1994). Tradition and traditional religion are also widely viewed as problematic concepts in the literature because they are not static constructs. See Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Roger M. Keesing, ‘‘Kastom in Melanesia: An Overview,’’ Mankind 13, no. 4 (1982): 297–301; Andrew Lattas, Cultures of Secrecy: Reinventing Race in Bush Kaliai Cargo Cults (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998).

10

To those unfamiliar with the PNG religious landscape, it may appear contra-dictory or surprising to learn that although 96 percent of PNG citizens are affiliated with Christian denominations, many are also members of cargo cults. Christianity in PNG is blended and syncretized with traditional religions; most Papua New Guineans involved with cargo cults co-opt concepts, symbols and rhetoric from within Christianity and incorporate these into their cargo cult beliefs and rituals.

11 Scott Flower, ‘‘The Struggle to Establish Islam in Papua New Guinea (1976–

1983),’’Journal of Pacific History44, no. 3 (2009): 241–60.

12 Scott Flower, ‘‘Christian-Muslim Relations in Papua New Guinea,’’Journal of

Islam and Christian Muslim Relations23, no. 1 (2012): 201–17.

13 The claim by converts that they are returning to their original religion is

striking, given the research findings of Aloysius Pieris and Donal Dorr, who claim that primal cultures (such as those of indigenous people of PNG) do not actually give away their traditional religion to convert to world religions such as Christianity or Islam. In their respective works, Pieris and Dorr add that so-called primal people in fact cannot give up their traditional religion completely because their cosmic spirituality is so deeply ingrained that it remains an underlying dimension of their religious ontology and epistemol-ogy. They argue that a traditional religion’s beliefs, values and symbols actu-ally determine the degree to which conversions occur, especiactu-ally where primal/traditional religions are concerned with sacred earthly matters while metacosmic religions such as Christianity and Islam are concerned with otherworldly realities. This means any new religion that shares a degree of similarity with old beliefs may be readily adopted. See Aloysius Pieris, S.J.,An Asian Theology of Liberation(New York: T & T Clark, 1988), 7; Aloysius Pieris, S.J.,Fire and Water: Basic Issues in Asian Buddhism and Christianity(Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1996); and Donal Dorr,Mission in Today’s World (Dublin: Columba Press, 2000).

14

15 Talal Asad,Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity

and Islam(Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1993), 134; and Leon Salzman, ‘‘The Psychology of Religious and Ideological Conversion,’’Psychiatry 16, no. 2 (1953): 177–87.

16 Alan R. Tippett,Solomon Islands Christianity: A Study of Growth and Obstruction

(London: Lutterworth Press, 1967), 79–81.

17 While there are many similarities between the three Abrahamic religions

(Judaism, Christianity, Islam) there also are large differences regarding doc-trinal matters (such as salvation), rituals, and the symbols and values of faith. Muslim converts refer to and cite these as reasons for their conversion. For a discussion see Adam Dodds, ‘‘The Abrahamic Faiths? Continuity and Discontinuity in Christian and Islamic Doctrine,’’Evangelical Quarterly81, no. 3 (2009): 230–53.

18 Kenelm Burridge, New Heaven, New Earth: A Study of Millenarian Activities

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1969), 3.

19

Clifford Geertz, ‘‘Religion as a Cultural System,’’ inAnthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion, ed. Michael Banton (London: Tavistock, 1966), 2.

20

Robin Horton, ‘‘African Conversion,’’Africa: Journal of the International African Institute41, no. 2 (1971): 23; Horton, ‘‘On the Rationality of Conversion, Part I,’’ Africa45, no. 3 (1975): 16; and Horton, ‘‘On the Rationality of Conversion, Part II,’’Africa45, no. 4 (1975): 26.

21

Richard W. Bulliet, Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979), 33–42.

22

Imran was a subsistence farmer interviewed in the village of Karilmaril, Chimbu Province, 8 September 2007.

23 Rebecca S. Norris, ‘‘Converting to What? Embodied Culture and the

Adoption of New Beliefs,’’ in The Anthropology of Religious Conversion, ed. Andrew Buckser and Stephen D. Glazier (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003): 171–82.

24 Ton Otto and Poul Pedersen, ‘‘Disentangling Traditions: Culture, Agency

and Power,’’ inTradition and Agency: Tracing Cultural Continuity and Invention, ed. Ton Otto and Poul Pedersen (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2005), 11–49; Rodney Stark, ‘‘How New Religions Succeed: A Theoretical Model,’’ inThe Future of New Religious Movements, ed. David G. Bromley and Phillip E. Hammond (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1987), 11–29; and Rodney Stark, ‘‘Why Religious Movements Succeed or Fail: A Revised General Model,’’Journal of Contemporary Religion11, no. 2 (1996): 133–46.

25

Joel Robbins, ‘‘Continuity Thinking and the Problem of Christian Culture: Belief, Time, and the Anthropology of Christianity,’’Current Anthropology48, no. 1 (2007): 5–38.

26 Jaap Timmer,Living with Intricate Futures: Order and Confusion in Imyan Worlds,

Irian Jaya, Indonesia(Nijmegen: Centre for Pacific and Asian Studies, 2000), 3.

27 I do not assume that traditional religions or societies in PNG were static prior

could occur through individual revelation (such as dreams) or through group consensus. This was possible because traditional religions, while strict in the application of lore, lacked the strictness of religious hierarchies and orders such as lay priests, priests and bishops. See Trompf,Religions of Melanesia,5.

28

Ron Brunton, ‘‘Misconstrued Order in Melanesian Religions,’’Man15, no. 1 (1980): 112–28.

29

G. W. Trompf, Melanesian Religion(New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 141–62.

30

G. E. Gorman, ‘‘Foreword,’’ in Trompf,Religions of Melanesia, ix-xxi.

31

Ton Otto and Ad Borsboom, eds.,Cultural Dynamics of Religious Change in Oceania(Leiden: Brill, 1997), 7.

32

Cosmology is defined here as a concept of the universe and the place of humans and other creatures in it. See Fiona Bowie,The Anthropology of Religion: An Introduction(Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 108.

33

Analysts see the underlying spirituality of specific forms of Christianity in PNG as rooted in primal cosmology, and not necessarily Christianity in its broadest sense. See Philip Gibbs, ‘‘It’s in the Blood: Dialogue with Primal Religion in Papua New Guinea,’’ Catalyst: Social Pastoral Journal for Melanesia 34, no. 2 (2004): 129–39; Peter Lawrence and Mervyn J. Meggitt, eds.,Gods, Ghosts, and Men in Melanesia: Some Religions of Australian New Guinea and the New Hebrides (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1965), 8–9; and Brunton, ‘‘Misconstrued Order in Melanesian Religions,’’ 25–32.

34 Freya Mathews,The Ecological Self(London: Routledge, 1994), 13.

35 Garry W. Trompf, ed., The Gospel Is Not Western: Black Theologies from the

Southwest Pacific(Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1987), 23–37.

36 While it is true that Christianity was adopted by many indigenous converts as

a name for the religion they already knew, converts to Islam embrace that religion because it is even more closely aligned to their traditional religions. See John Barker, ‘‘Introduction: Ethnographic Perspectives on Christianity in Pacific Societies,’’ in Christianity in Oceania: Ethnographic Perspectives(Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1990), 5–7.

37

Edward P. Wolfers, Race Relations and Colonial Rule in Papua New Guinea (Sydney: Australia and New Zealand Book Co., 1975), 7–9.

38

Trompf,Melanesian Religion,262–64

39

R. M. Smith, ‘‘Christ, Keysser and Culture: Lutheran Evangelistic Policy and Practice in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea,’’Canberra Anthropology2, no. 1 (1979): 78–97; and Christian Keysser,A People Reborn(Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey Library, 1980), 5.

40 Tippett,Solomon Islands Christianity,79. 41

Nils Bubandt, ‘‘On the Genealogy of Sasi: Transformations of an Imagined Tradition in Eastern Indonesia,’’ in Otto and Pedersen, Tradition and Agency, 193–232.

42 Gibbs, ‘‘Papua New Guinea,’’ 91.

43 Malcolm Ruel, ‘‘Christians as Believers,’’ inA Reader in the Anthropology of

44 Saeed was a 24-year-old male of mixed Karema and Chimbu ethnicity who was

unemployed at the time of the interview and living in temporary shelter at the Port Moresby mosque. He was an adopted child who had struggled with alcohol and drug abuse. Personal interview, 5 July 2007.

45

Muhammad Ali Al-Hashimi,The Ideal Muslim(Riyadh: International Islamic Publishing House, 2005); Muhammad al-Ghazali,Muslim’s Character(Riyadh: Mubarat SK. Hassan Tahir. Al-Islamiah, 1985); Abdullahi A. An-Na’im,Islamic Family Law in a Changing World: A Global Resource Book(New York: Zed Books, 2002); and N. J. Dawood,The Qur’an(New York: Penguin Books, 2003).

46

Bertram H. Raven, ‘‘Kurt Lewin Address: Influence, Power, Religion, and the Mechanisms of Social Control,’’Journal of Social Issues55, no. 1 (1999): 161–86.

47

Freda Adler,Nations Not Obsessed with Crime(Littleton, Colo.: Fred Rothman & Co., 1983).

48 Douglas Hayward, ‘‘Melanesian Millenarian Movements: An Overview,’’ in

Religious Movements in Melanesia Today, ed. Wendy Flannery and Glen W. Bays, vol. 1 (Goroka, PNG: Melanesian Institute for Pastoral and Socio-Economic Service, 1983), 16.

49

al-Ghazali,Muslim’s Character, 2.

50

Matthew R. Lee, ‘‘The Religious Institutional Base and Violent Crime in Rural Areas,’’Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion45, no. 3 (2006): 309–24.

51

This quotation from Somare was written down as a fieldwork note on 10 October 2007 from the 1993 PNG Parliamentary Hansard (official Parliamentary record). In 2006 politician Don Polye called for Islamic punish-ments such as stoning, public floggings and the cutting off of limbs for crimes such as murder, rape, drug smuggling and theft, claiming law should be ‘‘a tooth for a tooth and an eye for an eye.’’ See Isaac Nicholas ‘‘PNG Minister Mulls ‘Islamic’ Penalties for Violent Crime,’’The National, 29 June 2006, 3.

52 D. Songro, ‘‘Execute Murderers and Rapists,’’Post Courier(Mount Hagen), 22

May 2002, 7.

53 Yusuf was a leading senior Muslim living in Port Moresby and was employed as

Director of Information Technology at Central Bank of Papua New Guinea at the time of being interviewed in Port Moresby.

54 ‘‘UN Human Rights Office Regrets Papua New Guinea’s Decision to Resume

Death Penalty,’’ UN News Centre, 31 May 2013, at www.un.org/apps/news/ story.asp?NewsID¼45049&Cr¼death+penalty&Cr1#.UkEHU4ZmjuA.

55 When interviewed on 17 September 2007 Abu Bakr was living in a squatter

settlement.

56 Paula Brown, Beyond a Mountain Valley: The Simbu of Papua New Guinea

(Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1995), 254.

57 al-Hashimi,The Ideal Muslim, 82–89. 58 Personal interview, 5 July 2007.

59 Mikail was employed as a high school teacher and he was interviewed in his

office at the Kerowagi High School, Chimbu Province, 12 September 2007.

60 Musinah was employed at a store in Alotau, PNG. Personal interview, 13

61 Pentecostal and evangelical churches in PNG are not exceptional here, given

the global trend is for more women than men to join, stay with and be more active in fundamentalist churches (Pentecostal and evangelical), insofar as these churches tend to enhance women’s autonomy and equality. See Bernice Martin ‘‘The Pentecostal Gender Paradox: A Cautionary Tale for the Sociology of Religion,’’ inThe Blackwell Companion to Sociology of Religion, ed. Richard K. Fenn (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 52–66.

62 Personal interview, 7 October 2007. 63

See Joseph Ketan,The Name Must Not Go Down: Political Competition and State-Society Relations in Mount Hagen, Papua New Guinea (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, 2004), 78.

64 Pamela J. Stewart and Andrew Strathern, ‘‘The Great Exchange: Moka with

God,’’Journal of Ritual Studies15, no. 2 (2001): 91–104.

65 Personal interview, 8 August 2007. Wassim was unemployed and living in

a squatter settlement.

66 John Lofland and Norman Skonovd, ‘‘Conversion Motifs,’’ Journal for the

Scientific Study of Religion 4 (1981): 373–85; Lewis R. Rambo, Understanding Religious Conversion(New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993), 44–55; and Chana Ullman,The Transformed Self: The Psychology of Religious Conversion(New York: Plenum Press, 1989), 18–31.

67

Ali was a trained welder but at the time of interview held only casual employ-ment. Personal interview, 23 August 2007.

68

Personal interview, 22 August 2007. Hussein was unemployed and living at a squatter settlement.

69

Personal interview, 12 September 2007. Ruqaiya had just returned from a visit to Malaysia where she was being religiously trained by an Islamic missionary group known as RISEAP.

70

Personal interview, 10 August 2007. Ibrahim was employed part-time as a secu-rity guard.

71

Colin De’Ath, ‘‘Christians in the Trans-Gogol and the Madang Province,’’ Bikmaus 2, no. 2 (1981): 66–93; Trompf, Melanesian Religion, 141–62; and Burridge,New Heaven, New Earth, 25–29.

72 Peter Biskup, Brian Jinks and Hank Nelson, eds.,A Short History of New Guinea

(Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1970), 6–15.

73 Webb Keane, ‘‘Materialism, Missionaries, and Modern Subjects in Colonial

Indonesia,’’ inConversion to Modernities: The Globalization of Christianity, ed. Peter van der Veer (New York: Routledge, 1996), 137–69; Carol Summers, ‘‘Tickets, Concerts and School Fees: Money and New Christian Communities in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1900–1940,’’ inConversion: Old Worlds and New, ed. Kenneth Mills and Anthony Grafton (New York: University of Rochester Press, 2003), 241–70.

74

Peter Lawrence,Road Belong Cargo: A Study of the Cargo Movement in the Southern Madang District New Guinea(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1964).

75

Jan Pouwer, ‘‘The Colonisation, Decolonisation and Recolonisation of West New Guinea,’’Journal of Pacific History34, no. 2 (1999): 157–79.

76

77 Carl Loeliger and Garry Trompf,New Religious Movements in Melanesia(Suva:

Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1985).

78

Compared with primal religions in other parts of the world, a large volume of research shows that Melanesian religions had a ‘‘relatively stronger preoccupa-tion with wealth and prosperity as compared to the focus on health in African primal religions, which explains why cargo cult phenomena are more intense in Melanesia than anywhere else in the world.’’ Trompf,Religions of Melanesia, 32.

79 John G. Strelan,Search for Salvation: Studies in the History and Theology of Cargo

Cults(Adelaide: Lutheran Publishing House, 1977), 13.

80

Andrew J. Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart, ‘‘Introduction: A Complexity of Contexts, A Multiplicity of Changes,’’ inReligious and Ritual Change: Cosmologies and Histories, ed. Pamela J. Stewart and Andrew Strathern (Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press, 2009): 3–68.

81

Jebens,Pathways to Heaven, 173.

82 M. Gerawa, ‘‘Govt Blamed in Chimbu Closure,’’Post Courier(Mount Hagen),

15 April 1997, 5; and N. Setepano, ‘‘Church Health Services Close Down in Three Provinces,’’Post Courier(Mount Hagen), 14 April 1997, 8.

83 Joe Meava, ‘‘Why Govt Cut Ventures – PM,’’Post Courier(Mount Hagen), 14

April 1999, 4.

84

Personal interview, Port Moresby, 27 July 2007. Asad was living with extended family.

85

Clifford Geertz,The Interpretation of Cultures(New York: Basic Books, 1973), 89.

86

Trompf,Melanesian Religion,141–62.

87

Garry W. Trompf, ‘‘Competing Value-Orientations in Papua New Guinea,’’ in Ethics and Development in Papua New Guinea, ed. Gernot Fugmann (Goroka: Melanesian Institute for Pastoral and Socio-Economic Service, 1986), 17–34.

88

Barbara D. Metcalf, ‘‘‘Remaking Ourselves’: Islamic Self-Fashioning in a Global Movement of Spiritual Renewal,’’ inAccounting for Fundamentalisms: The Dynamic Character of Movements, ed. Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1994), 706–25; and Karla O. Poewe, ed., Charismatic Christianity as Global Culture(Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994).

89

Robert W. Hefner, ‘‘Multiple Modernities: Christianity, Islam and Hinduism in a Globalizing Age,’’Annual Review of Anthropology27 (1998): 83–104; Steven Kaplan, ed.,Indigenous Responses to Western Christianity (New York: New York University Press, 1995); and van der Veer,Conversion to Modernities.

90

Vicente L. Rafael,Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society under Early Spanish Rule(Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1988), 6–9; and Gauri Viswanathan,Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief(Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998).

91

Bronwyn Douglas, ‘‘From Invisible Christians to Gothic Theatre: The Romance of the Millennial in Melanesian Anthropology,’’Current Anthropology 42, no. 5 (2001): 616–17.

92

93 Horton, ‘‘African Conversion,’’ 85–108; Horton, ‘‘On the Rationality of

Conversion, Part I,’’ 219–35.

94 Joel Robbins, ‘‘The Globalization of Pentecostal and Charismatic

Christianity,’’ Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 117–43; Richard Eves, ‘‘Waiting for the Day: Globalization and Apocalypticism in Central New Ireland, Papua New Guinea,’’ Oceania71, no. 2 (2000): 73–91; Richard Eves, ‘‘Money, Mayhem and the Beast: Narratives of the World’s End from New Ireland (Papua New Guinea),’’Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute9, no. 3 (2003): 527–47; and Ernst,Globalization and the Re-Shaping of Christianity in the Pacific Islands.

95

For a comprehensive presentation of data relating to this point and discussion of secularization in PNG, see Flower, ‘‘Growth of Islam in Papua New Guinea.’’

96 Peter L. Berger,The Scared Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion

(New York: Doubleday, 1967).

97 Geertz, ‘‘Religion as a Cultural System,’’ 1–39; and Trompf, Religions of

Melanesia.

98 Bernard Narokobi, The Melanesian Way: Total Cosmic Vision of Life (Port

Moresby: Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, 1980); and Bernard Narokobi, ‘‘What Is Religious Experience for a Melanesian?’’ inLiving Theology in Melanesia: A Reader, ed. John D’Arcy May (Goroka: Melanesian Institute for Pastoral and Socio-Economic Service, 1985), 7–12.

99

Many academics agree with Narokobi’s perspective and point out that the integrated worldview held by most people in PNG is at odds with Christianity and Western science. See Asad,Genealogies of Religion; Trompf,Melanesian Religion; and Ernst,Globalization and the Re-Shaping of Christianity in the Pacific Islands.

100

Gabriel Almond, R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan, eds., Strong Religion: The Rise of Fundamentalisms around the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003); Steve Bruce, Fundamentalism(Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2000); Michael O. Emerson and David Hartman, ‘‘The Rise of Religious Fundamentalism,’’ Annual Review of Sociology32 (2006): 127–44; Marty and Appleby,Accounting for Fundamentalisms; and Mark Riesebrodt, ‘‘Fundamentalism and the Resurgence of Religion,’’Numen47 (2000): 266–87.

101

Ernst,Globalization and the Re-Shaping of Christianity in the Pacific Islands, 5.

102

Gibbs, ‘‘Papua New Guinea,’’ 98.

103

David C. Wakefield, ‘‘Sectarianism and the Miniafia People of Papua New Guinea,’’Journal of Ritual Studies15, no. 2 (2001): 38–54; and De’Ath, ‘‘Christians in the Trans-Gogol and the Madang Province.’’

104

Bronwen Douglas, ‘‘Why Religion, Race, and Gender Matter in Pacific Politics,’’Development Bulletin1, no. 59 (2002): 11–14.

105

‘‘PNG Churches: First Heal Themselves,’’The National, 8 December 2003, 15.

106 E. Sasere, ‘‘Muslim Faith Opens Doors,’’Post Courier(Mount Hagen), 14 May

2003, 5.

107 A. Alphonse, ‘‘Archbishop Faces Church Split,’’The National, 15 February

2007, 3.

108 John Walters, ‘‘Down with the Crooks,’’The National, 26 April 2007, 7. 109