Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Content Guidelines for an Undergraduate Human

Resources Curriculum: Recommendations From

Human Resources Professionals

Michael Z. Sincoff & Crystal L. Owen

To cite this article: Michael Z. Sincoff & Crystal L. Owen (2004) Content Guidelines for an Undergraduate Human Resources Curriculum: Recommendations From Human Resources Professionals, Journal of Education for Business, 80:2, 80-85, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.2.80-85 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.2.80-85

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 47

View related articles

esigning an effective curriculum for an undergraduate program in human resources (HR) is no easy task. One reason for the difficulty is the dra-matic rate of change in the business world, which means that those charged with the design and development of undergraduate business curricula are faced with a need for continuous review to ensure pertinent curricular offerings that will prepare their graduates for suc-cessful careers in their chosen disci-plines (Giullian, Odom, & Totaro, 2000; Skousen & Bertelsen, 1994). The design task is made even more difficult by the need for programs that are appropriate as university offerings; in other words, programs that offer more than simply vocational training (Kaufman, 1999).

Another reason for the difficulty in designing effective HR undergraduate programs is the absence of a clearly defined and widely accepted common body of knowledge for the field. Unlike, for example, accounting professionals, who must demonstrate mastery of a common body of knowledge by passing the CPA exam, or lawyers, who must pass the bar to practice law, HR profes-sionals have no certification require-ment to practice in the HR field. The Human Resources Certification Insti-tute (HRCI), associated with the Society for Human Resource Management, offers two levels of certification to

demonstrate HR competency—profes-sional certification (PHR) for those rel-atively new to the field and senior pro-fessional certification (SPHR) for those who are experienced. Yet, although Losey (1997, 1999) argued persuasively for accepting the HRCI exam content as a common body of knowledge for the HR profession, HRCI certification is neither required nor widely recognized as a sufficient measure of knowledge for practicing HR professionals.

As a result, educators typically turn to the research literature for information to guide curricular decisions. Unfortunately, research findings are limited in terms of offering guidance for the design of effec-tive undergraduate HR programs. As Hansen (2002) pointed out, much of the discussion in the recent research literature has focused on broad changes in the chal-lenges facing HR executives and senior managers and has placed considerably less emphasis on how to prepare new HR job entrants (Kochan, 1997; Schuler, 1990; Ulrich, 1997a, 1997b). Thus, the literature’s usefulness in designing effec-tive undergraduate curricula is limited. Of the articles that do address curricular issues, most offer prescriptions based on the authors’ knowledge of the field rather than on empirical evidence. For example, Shaw (1994) proposed the notion of inte-grating information technology (i.e., computers) into the human resources cur-riculum. Kaufman described the evolu-tion and current status of university HR programs, observing that “modern-day HR education mirrors the trend in indus-try to treat the practice of human resources as a management function on par with other functional areas of busi-ness and performed to promote the long-term profit objectives of the firm” (1999, p. 108). He further noted that there is a discrepancy between what is taught in HR education and what is wanted by

Content Guidelines for an

Undergraduate Human Resources

Curriculum: Recommendations

From Human Resources

Professionals

D

ABSTRACT. In this study, the authors surveyed 445 human resources (HR) professionals to deter-mine their views regarding the HR curriculum content that will lead to graduates’ success in entry-level (first-job) HR positions. Ninety-eight ques-tionnaires (22%) were returned. Respondents identified five topics— equal employment opportunity/affir-mative action (EEO/AA), employee rights and responsibilities, recruit-ment, selection, and compensation— as most important. They considered internship experience to be more valu-able than professional human resource certification and indicated that HR curricula should reflect workplace and societal trends, general business understanding, and communication and teamwork skills. For HR curricu-lum development, the authors suggest a “niche” approach that provides in-depth training in some common HR functions, along with training in com-munication and teamwork skills.

MICHAEL Z. SINCOFF

Wright State University Dayton, Ohio

CRYSTAL L. OWEN

University of North Florida Jacksonville, Florida

executives in business. Walker and Black (2000) argued in favor of a process-centered business curriculum containing four courses intended to replace the tradi-tional, common-body-of-knowledge, business core curriculum. Their proposal for an HR acquisition process course is significant. Walker and Black recom-mended that such a course should contain the following topics: wage structures, employment law, manpower planning, hiring, training, organizing, compen-sation, tax issues in compencompen-sation, HR/ payroll systems, payroll accounting, eval-uating productivity and behavior, and terminating/retiring employees.

The empirical studies that focus on curricular issues tend to address graduate level HR education rather than under-graduate education (Giannantonio & Hurley, 2002; Heneman, 1999; Langbert, 2000). In spite of the fact that there are over 30 U.S. colleges of business offer-ing undergraduate degrees in HR (Indus-trial Relations Research Association [IRRA], 2003), our review of recent research identified only three empirical studies that directly address the question of which HR fields and skills are most relevant for entry-level HR professionals from undergraduate HR programs. Van Eynde and Tucker (1997), for example, used the Delphi technique on a panel of 24 senior-level HR executives who indi-cated that the most important HR curric-ular offerings for entry-level baccalaure-ate gradubaccalaure-ates, in order of importance, should be the HR strategic role, compen-sation, EEO, organization development, communication and counseling, HR planning, and selection. Johnson and King (2002) interviewed 12 human resources/industrial relations (HR/IR) executives to determine the relative importance of a variety of HR competen-cies for entry-level HR practitioners. They found a different set of recom-mended competencies. For the subjects in the Johnson and King study, recruit-ment, communication, selection, perfor-mance appraisal, training, and HR plan-ning were among the most important traditional HR competencies for entry-level HR practitioners. Way (2002) argued that current jobholders, rather than senior management, had the most current and accurate information on topic areas of importance for first-job

appli-cants. Way surveyed HR professionals to determine their perceptions of the rela-tive importance of educational courses in preparing a person with no prior relevant education or experience for an HR job. He found general HR management, selection, employment law, staffing, ben-efits, compensation, and training to be the most important perceived areas of HR knowledge.

HRCI is an additional source of infor-mation about undergraduate HR curricu-lum content that is based on feedback from HR professionals. HR undergradu-ates can sit for the Professional in Human Resources (PHR) exam. Using a modi-fied Delphi technique, HRCI regularly consults HR practitioners, consultants, educators, and researchers to develop and modify its certification exams (Weinberg, 2002) as well as conduct expert reviews, extensive literature searches, and analy-ses of HR textbooks. Content areas of HR knowledge as defined by HRCI for the PHR exam, in order of exam emphasis, are workforce planning and employment; employee and labor relations; compensa-tion and benefits; HR development; strategic management; and occupational health, safety, and security.

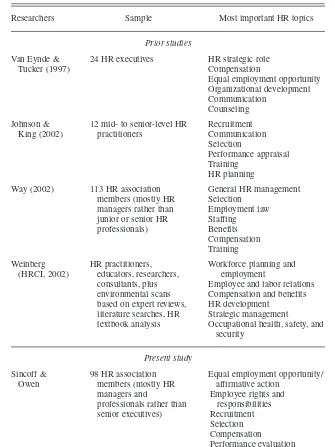

Arguably, we need more empirical research to extend our knowledge of appropriate content for undergraduate HR programs. To help ensure curricular relevancy of course offerings, the AACSB International (2002) recom-mended that business educators engage in dialogue with business and community stakeholders to develop course content that satisfies the needs of all constituents. Certainly the existing studies focusing on undergraduate curricular needs are con-sistent with the AACSB recommendation in terms of approach, but the results vary across the three empirical studies and the HRCI in terms of curriculum content (see Table 1 for a comparison summary). For this reason, in this study we sought to investigate further the specific course content that HR professionals perceive as necessary for HR undergraduates to com-plete to be qualified to assume entry-level (first-job) HR positions upon graduation.

Method

A panel of three HR experts devel-oped a questionnaire to determine how

important various HR subject matter areas in an undergraduate HR curricu-lum are to entry-level HR professionals. Two members of the panel (the authors of this article) were senior-level faculty members whose teaching emphasis was in HR. The third panelist was an executive-level HR practitioner with more than 25 years of HR experience. We based questionnaire content on a review of the literature, the experiences of the panel members, and a content review of HR textbooks.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections. Section 1 asked the pri-mary research question: “How impor-tant is coursework in the following HR topics for ‘first-job’ HR professionals?” Possible responses were divided into 20 possible response topics. We asked respondents to rate each topic on a 5-point, Likert-type scale that included the following anchors: 5 (vital), 4 (very important but not critical), 3 ( impor-tant), 2 (of marginal importance), and 1 (not at all important).

Section 2 of the questionnaire con-tained two questions to ascertain the respondents’ beliefs as to the relative importance of HRCI certification and hands-on student experience in HR. The first question was, “To what extent do you perceive PHR certification (e.g., having passed the exam) pos-sessed by a recent HR graduate a ‘plus’ in your evaluation of that individual as a job applicant?” We provided the fol-lowing response alternatives: (a) “PHR certification is highly valued and would be a significant ‘plus’ in my evaluation” (3 points); (b) “PHR certi-fication is valued and would be a ‘plus,’ but it would not have a signifi-cant impact on my evaluation” (2 points); and (c) “PHR certification is not that important to me in evaluating recent graduates” (1 point).

Similarly, the second question in Sec-tion 2 was, “To what extent do you per-ceive hands-on experience as a student HR consultant for a [local] business to be a ‘plus’ in your evaluation of a recent HR graduate as a job applicant?” Response alternatives were (a) “Student consulting experience is highly valued and would be a significant ‘plus’ in my evaluation” (3 points); (b) “Student con-sulting experience is valued and would

be a ‘plus,’ but it would not have a sig-nificant impact on my evaluation” (2 points); and (c) “Student consulting experience is not that important to me in evaluating recent graduates” (1 point).

In Section 3 of the questionnaire, we provided space for respondents to indi-cate additional topics that they deemed important but that may have been omit-ted on the questionnaire, as well as to elaborate on any answers and make any additional comments.

In 2001–2002, we mailed question-naires to the 445 current members of a professional HR association in the

Midwest. Ninety-eight questionnaires were returned, representing a response rate of 22%, which is reasonable in survey research of this type. Associa-tion membership consisted primarily of nonexecutive-level HR managers and professionals. We did not collect demographic data on the respondents at the request of the association.

Results

In Table 2, we show the mean ratings associated with each of the HR topics addressed in Section 1 of the

question-naire. Of the 20 course topics presented to the respondents, five (EEO/AA, employee rights and responsibilities, recruitment, selection, and compensa-tion) were identified as very important to vital,with ratings of 4.03 to 4.78. The respondents rated the following 14 course topics as important to very important (performance evaluation/ appraisal, HR information and assess-ment systems, organizational develop-ment, strategic role of HR, training and development, orientation, labor/man-agement relations, safety, job analysis and design, future of HRM, leadership effectiveness, career planning and development, evaluating the HR func-tion, and HR audits), with ratings between 3.17 and 3.88. Only one topic, global HR, was ranked as marginally important(2.64).

Ratings for EEO/AA, employee rights and responsibilities, recruitment, and selection were significantly higher than ratings for topics in the other ratings cat-egories (e.g., all catcat-egories besidesvery important to vital). The rating for com-pensation (4.03) was significantly higher than ratings for topics with lower ratings, with the exception of performance evalu-ation/appraisal (3.88), which was not significantly different from the compen-sation rating. The rating for global HR was significantly lower than ratings for all other topics.

In Section 2 of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to rate, on a 3-point scale, the degree to which PHR certification versus hands-on experience would be perceived as a “plus” in eval-uating a recent HR graduate as a job applicant. Both PHR certification and hands-on experience were seen by this group of HR professionals as positive attributes for recent HR graduates applying for jobs, with an average rating of 2.25 for PHR certification and 2.64 for experience in the form of student HR consulting with local businesses. However, consulting experience was perceived as significantly more impor-tant than PHR certification (t= 4.33; p< .01). In the comments section of the questionnaire, several respondents were compelled to comment on the value of HR experience over PHR certification. For example, one respondent wrote, “Real-life, hands-on experience is more

TABLE 1. A Comparison of Undergraduate Curriculum Topics Identified as Most Important for Entry-Level Human Resources (HR) Professionals in Prior Studies and the Present Study

Researchers Sample Most important HR topics

Prior studies

Van Eynde & 24 HR executives HR strategic role

Tucker (1997) Compensation

Equal employment opportunity Organizational development Communication

Counseling

Johnson & 12 mid- to senior-level HR Recruitment King (2002) practitioners Communication

Selection

Performance appraisal Training

HR planning

Way (2002) 113 HR association General HR management members (mostly HR Selection

managers rather than Employment law junior or senior HR Staffing

professionals) Benefits Compensation Training

Weinberg HR practitioners, Workforce planning and (HRCI, 2002) educators, researchers, employment

consultants, plus Employee and labor relations environmental scans Compensation and benefits based on expert reviews, HR development

literature searches, HR Strategic management textbook analysis Occupational health, safety, and

security

Present study

Sincoff & 98 HR association Equal employment opportunity/ Owen members (mostly HR affirmative action

managers and Employee rights and professionals rather than responsibilities senior executives) Recruitment

Selection Compensation Performance evaluation

valuable than PHR. Nothing can replace actual face-to-face discussion or learn-ing firsthand what really happens in the workplace.” Another commented, “The PHR tells me the person is committed to HR, knowledgeable, and willing to work. Experience, however, is always invaluable.”

Although many respondents (42, or 42.9%) made comments in Section 3 of the questionnaire, most of these com-ments were specific to the needs of the respondents’ particular organizations. For example, one respondent wrote, “Safety issues have an important role in my everyday responsibilities. This is an area where it is difficult to find assistance and know what the OSHA reps say and mean. I would recom-mend additional training in this area.” Yet, the topic of safety was rated 3.45 by the respondents as a group, 13th in importance, and mentioned by only one other respondent in the comments section.

Two points, however, were repeated consistently in Section 3 and deserve special mention. First, respondents indi-cated that interpersonal communication skills need to be taught to HR students.

These skills, according to the respon-dents, include public speaking and mak-ing effective presentations, writmak-ing reports, listening, and reading ability. The ability to work in teams was also high on the list of communication skills. One respondent summed up this idea by writing, “The student also needs to know how to work in teams and have effective communication skills. I have seen graduates fail more as a result of how they deal with people than their [lack of] technical skills.”

The second point repeatedly men-tioned by the respondents is that under-graduate curricula should include at least one, and ideally more than one, internship opportunity so that students can learn to apply classroom theory. Respondents allowed that the internship could be in the form of student teams having HR project management con-sulting engagements with real business organizations or in the form of HR co-op work experience. As one respondent noted, “Nothing can replace actual face-to-face discussion or learning firsthand what really happens in the workplace. It is one thing to read about it. It is another to do it.” Another respondent said,

“Classroom theory cannot prepare the HR novice. For the myriad unique chal-lenges presented to HR on a daily basis, I often say, ‘Just when I think I’ve heard everything, an employee will present something new that I couldn’t have imagined or made up.’”

In addition to these two points about specific skills or experiences that respondents would value in HR gradu-ates, several made comments about the need for undergraduates to start their professional lives with a firm grasp of functional HR skills. One respondent commented that “my experience is that they don’t need a lot of HR planning or big-picture knowledge for the first few years on the job.” Another wrote that knowledge of functional HR skills “gives a good foundation for the employer to teach about the HR role in the company, strategic planning, etc.” On the other hand, several others offered comments about the need for HR graduates to possess strong business skills as well as HR skills. For example, as one respondent wrote, “It is impor-tant for HR to think of themselves as a business partner and to understand how the company functions, how to relate to customers, and how HR can help departments meet goals.”

Discussion

In the current study of HR profession-als, the course topics receiving the high-est ratings in terms of their importance for inclusion in an undergraduate HR curriculum were EEO/AA, employee rights and responsibilities, recruitment, selection, compensation, and perfor-mance evaluation. Ideally, we had hoped that the results of this study, together with those of previous studies, would provide a synthesis that would allow us to pinpoint the course topics most important for inclusion in an undergrad-uate HR curriculum. Yet, a comparison of the results of the current study with the results of previous studies as pre-sented in Table 1 indicates that we can-not make such a synthesis. Although some HR course topics identified as important in the current study are com-mon to two or three of the previous stud-ies, we do not have enough evidence from the results of the five studies to

TABLE 2. Respondents’ Ratings of Importance of Undergraduate Course Topics for First-Job Human Resources (HR) Professionals

Course topic Rating

Equal employment opportunity/affirmative action 4.78

Employee rights and responsibilities 4.33

Recruitment 4.33

Selection 4.20

Compensation 4.03

Performance evaluation 3.88

HR information and assessment systems 3.78

Organizational development 3.74

Strategic role of HR 3.70

Training and development 3.67

Orientation 3.61

Labor/management relations 3.53

Safety 3.45

Job analysis and design 3.42

Future of HR management 3.37

Leadership effectiveness 3.25

Career planning and development 3.22

Evaluating the HR function 3.22

HR audits 3.17

Global HR 2.64

Note. Respondents answered on a scale with the following anchors: 5 (vital), 4 (very important but not critical), 3 (important), 2 (of marginal importance), and 1 (not at all important).

identify a definitive list of course topics that should be included in an undergrad-uate curriculum.

Our results, however, do contribute to a pattern that emerges when we com-pare previous empirical studies with each other and with the results of the current study. Studies based on the per-ceptions of executive-level HR profes-sionals (i.e., Johnson & King, 2002; Van Eynde & Tucker, 1997) indicate a con-cern for a skill set that encompasses more than knowledge of fundamental HR functional areas, including organi-zational development, communication, counseling, and the role of strategic HR planning. Rather than focusing on entry-level needs, senior managers and executives may be more aware of needs that reflect HR professionals’ long-term career concerns and higher-level organi-zational needs. Way (2002), for exam-ple, argued that current job holders have more timely and accurate information about the qualifications needed by entry-level HR employees.

Consistent with Way’s assertion, the results of the present study are more sim-ilar to Way’s results than they are to those of the other three studies. In other words, job incumbents at the practitioner level see functional HR skills as the most important areas of knowledge for entry-level HR employees. This perception makes perfect sense, given that the jobs of entry-level employees will require more fundamental HR tasks than, say, strategic HR-planning activities. Also, it is difficult to develop a strategic perspec-tive unless one understands the funda-mental activities that define the field of HR. For this reason, an effective under-graduate program should include courses on specific HR topic areas such as selec-tion, recruitment, compensaselec-tion, and employment law.

Yet, these functional skills will not be enough for long-term career success. As one of our respondents commented, “If HR professionals want to be successful they should better understand how busi-ness works.” Taken together with the studies by Van Eynde and Tucker (1997), Johnson and King (2002), Way (2002), (Weinberg, 2002), and the HRCI certification research, the results of our study suggest that an undergrad-uate degree in business with a major in

HR does have the potential to prepare students for long-term success as HR professionals, but only if the degree reflects training in effective communi-cation and team skills as well as funda-mental business and HR knowledge.

Still, the question remains as to what should be the content of an effective undergraduate HR curriculum that will prepare graduates for entry-level HR jobs. The classic call for more research in this area is appropriate at this point because it would be premature to sug-gest that two studies—the present one and that of Way (2002)—based on the perceptions of 211 Midwest HR practi-tioners are a sufficient basis on which to build universal recommendations for an effective HR curriculum. Nonetheless, our study’s results, combined with those of previous research, do suggest some considerations for those faced with the task of designing such a curriculum.

First, we should keep in mind the qualifications required for entry-level HR employees so that program graduates have knowledge, skills, and abilities that offer immediate value to employers. Cur-riculum focus should reflect workplace and societal trends and broad business understanding, with emphasis on those HR functional areas most likely to com-prise the tasks and responsibilities of entry-level employees. It should also incorporate other skills required for long-term professional success, such as com-munication and team skills.

Second, we should recognize that it may well be impossible to design a “one-size-fits-all” curriculum. As Bar-ber (1999) pointed out, it is difficult to imagine a single program providing suf-ficient coverage of all of the content areas suggested as necessary for HR professionals, and a business major that offers in-depth education on every func-tional area of HR would require more years to complete than most undergrad-uates are willing to devote to earning their degrees. Yet, the generalist approach reflected in most undergradu-ate HR programs does not prepare its graduates to perform any specific HR task without additional training. As one of our respondents commented, “Entry-level HR positions are typically in the administrative areas in order to give the HR employee exposure to HR before

investing in training or development in specific areas.”

A more useful approach in terms of the long-term career success of HR graduates could be for programs to reflect a “niche” approach to HR educa-tion, providing in-depth training on a subset of the more common HR func-tions (e.g., staffing, compensation) and including some training in communica-tion and team skills. Graduates of such a program would be highly qualified as entry-level employees because they would be prepared to make a specific and immediate contribution to the orga-nization with minimal training in their area of specialization.

Of course, one could argue that this niche type of education could mean that program graduates would not be consid-ered for jobs that do not require the spe-cialized skill set developed in such a program, and thus their job opportuni-ties would be limited. On the other hand, if the skill sets offered by a niche program are developed to match the most pressing organizational needs, program graduates not only would find jobs more readily but would be better prepared for rapid career progress because of their ability to make an immediate contribution to organization-al effectiveness with minimorganization-al additionorganization-al training. In addition, organizations are increasingly likely to outsource some of their HR functions (Stewart, 1996), which suggests, if this trend continues, that many of the future jobs in HR will be offered by firms to which the HR functions are outsourced and, thus, will require specialized skill sets. The niche approach will require that developers of HR curricula demonstrate superior pre-dictive skills to ascertain which HR niche will be important when students graduate and, therefore, what needs to be taught. However, use of this approach may result in the loss of an HR generalist foundation in students, which could cause a depletion of HR generalists in higher-level HR jobs.

In conclusion, we believe that those charged with developing undergraduate HR curricula need to adopt a strategic perspective to create effective HR edu-cation. Just as the opinion leaders in the HR literature suggest that businesses need to consider the strategic role of HR,

we need to consider the development of HR curricula strategically, which means identifying the mission of our programs in terms of what we are trying to accom-plish and for whom. Because of the inherent limitations in an undergraduate program, we must seek to optimize our effectiveness by establishing and focus-ing on precise goals. If we try to provide an HR program that is all things to all people, we are likely to fail.

REFERENCES

AACSB International. (2002, April). Management education at risk: A report from the Manage-ment Education Task Force, Executive Sum-mary. St. Louis: Author.

Barber, A. E. (1999). Implications for the design of human resource management—Education, training, and certification. Human Resource Management, 38(2), 177–182.

Giannantonio, C. M., & Hurley, A. E. (2002). Executive insights into HR practices and educa-tion. Human Resources Management Review, 12,491–511.

Giullian, M. A., Odom, M. D., & Totaro, M. W. (2000). Developing essential skills for success in the business world: A look at forecasting. Jour-nal of Applied Business Research, 16(3), 51–61.

Hansen, W. L. (2002). Developing new proficien-cies for human resource and industrial relations professionals. Human Resource Management Review, 12,513–538.

Heneman, R. L. (1999). Emphasizing analytical skills in HR graduate education: The Ohio State University MLHR program. Human Resource Management, 38(2), 131–134.

Industrial Relations Research Association (IRRA). (2003, October 11). Industrial relations and human resources degree programs in the U.S., Canada, Germany, and Australia. Retrieved October 24, 2003, from http://www.irra. edu/Pubs/DegreePrograms/degreeprograms.htm Johnson, C. D., & King, J. (2002). Are we

proper-ly training future HR/IR practitioners? A review of the curricula. Human Resource Management Review, 12,539–554.

Kaufman, B. E. (1999). Evolution and current sta-tus of university HR programs. Human Resource Management, 38(2), 103–110. Kochan, T. A. (1997). Rebalancing the role of

human resources. Human Resource Manage-ment, 36(1), 121–127.

Langbert, M. (2000). Professors, managers, and human resource education. Human Resource Management, 39(1), 65–78.

Losey, M. R. (1997). The future HR professional: Competency buttressed by advocacy and ethics. Human Resource Management, 36(1), 147–150.

Losey, M. R. (1999). Mastering the competencies of HR management. Human Resource Manage-ment, 38(2), 99–102.

Schuler, R. S. (1990). Repositioning the human resource function: Transformation or demise? Academy of Management Executive, 4(3), 49–60.

Shaw, S. (1994). Integrating IT into the human resource management curriculum: Pain or plea-sure? Education & Training, 36(2), 25–30. Skousen, K. F., & Bertelsen, D. P. (1994). A look

at change in management education. S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, 59(1), 13–20. Stewart, T. A. (1996, January 15). Taking on the

last bureaucracy. Fortune, 133(1), 105–108. Ulrich, D. (1997a). HR of the future: Conclusions

and observations. Human Resource Manage-ment, 36,175–179.

Ulrich, D. (1997b). Judge me more by my future than by my past. Human Resource Manage-ment, 36,5–8.

Van Eynde, D. F., & Tucker, S. L. (1997). A quali-ty human resource curriculum: Recommenda-tions from leading senior HR executives. Human Resource Management, 36(4), 397–408. Walker, K. B., & Black, E. L. (2000).

Reengineer-ing the undergraduate business core curricu-lum: Aligning business schools with business for improved performance. Business Process Management Journal, 6(3), 194–211. Way, P. K. (2002). HR/IR professionals’

educa-tional needs and master’s program curricula. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 471–489.

Weinberg, R. B. (2002). Defining the HR body of knowledge. Human Resource Institute certifi-cation guide(7th ed.), pp. 25–27.