Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:24

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Investigating the Benefits of Web-Centric

Instruction for Student Learning–An Exploratory

Study of an MBA Course

Michaela Driver

To cite this article: Michaela Driver (2002) Investigating the Benefits of Web-Centric Instruction for Student Learning–An Exploratory Study of an MBA Course, Journal of Education for

Business, 77:4, 236-245, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599078

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599078

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 17

View related articles

Investigating the Benefits of Web-

Centric Instruction for Student

Learning-An

Exploratory Study

of

an MBA Course

MICHAELA DRIVER

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

East Tennessee State University

Johnson City, Tennessee

y purpose in this study was to

M

investigate the effects of Web- centric instruction on students’ social interaction, involvement with course content, technical skills, and overall learning experience. To accomplish thisgoal, I first examined the forces driving

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

business schools to adopt new instruc- tional technologies, particularly those built around the Internet. Then I devel- oped a conceptual framework that edu- cational institutions such as business schools may use to structure their own learning processes as they adopt new instructional technologies. Then I

undertook a semester-long exploratory study focusing on the effects of Web- centric learning on various student out- comes in an MBA program.

Forces for Change in Environments of Business Schools

Powerful forces are driving business schools toward adopting new instructional technologies. Like other educational insti- tutions, many business schools already have embarked on substantial transforma- tions, often without full preparation (Mil- liron, 1999). According to recent statistics, U.S. universities currently offer over 54,000 courses online with an enrollment of over 1.6 million students (Sistek-Chan- dler, 2000), and online education is expected to grow from today’s $350-mil-

ABSTRACT. In this article, the author presents the results of an exploratory study in which she sur- veyed students to examine the benefits of Web-centric learning environments for the quality of student learning. More specifically, the author investi- gated the effects of Web-centric instruction on the quality of students’ social interaction, involvement with the course content, technical skills, and overall learning experience. Pre- liminary results of this study, conduct-

ed in

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an MBA course, indicate that students seemed to benefit positivelyfrom the instructional methods used.

lion to a $Zbillion industry by the year 2003 (McGinn, 2000). These statistics lend support to predictions that lifelong learning is not just a passing trend but per- haps will be the driving force behind edu- cation in the future (Weber, 1999). As more and more students, especially work-

ing professionals,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

turn

to institutions ofhigher education to keep pace with the growing of the knowledge economy and to “renew themselves continuously and

intellectually” (Horvath

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Teles, 1999, p.51), colleges and universities are strug- gling to embrace new computer-assisted educational technologies to accommodate the rising demand (Milliron, 1999). Dis- tance learning and instructional delivery via the Internet have become strategic planning concerns for institutions of high- er education (Kessler & Keefe, 1999) as more and more instructors are setting out

on their own to enhance student learning through the Internet (Roach, 1999). In fact, the strong push for technology- enhanced instruction has led some researchers to predict that distance learn- ing and traditional face-to-face instruction will become indistinguishable in the future (DuM, 2000). One author has pre- dicted that “by the year 2025, at least 95% of instruction in the United States will be digitally enhanced” (Dunn, 2000, p. 36). This shows that business schools, like most educational institutions, are under tremendous pressure to offer technology- enhanced instruction, which is why it is critical that a process be adopted that al- lows them to do so while minimizing the risks of failure. In this article, I show how such a process can be applied and what benefits the institution can hope to gain for its students from experimentation with precursors to fully Web-based instruction.

Technology-En hanced Instruction Within an Organizational Learning Framework

In this article, I examine technology-

enhanced instruction within the frame- work of an organizational learning approach to the adoption of such tech- nology in educational institutions. This framework encourages institutions to follow an evolutionary pattern in the adoption of new instructional technolo-

236

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education forzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Businessgies: Institutions should move from a Web-present stage to a Web-enhanced stage, then to a Web-centric stage, and finally to a Web-based stage (Driver, 2000). In the Web-present stage, the institution uses any instructional deliv- ery system in which the Internet is the repository of logistical and peripheral course information. In the Web- enhanced stage, the instructional deliv- ery system uses the Internet as a repos- itory for course materials as well as for student research and communication (Driver). The Web-centric stage in- volves any instructional delivery sys- tem that uses the Internet (a) for every purpose described in the Web- enhanced stage and (b) as a key resource to support communications and the sharing of ideas among stu- dents and between students and their instructor (Driver, 2000). Finally, the Web-based stage involves any instruc- tional delivery that uses the Internet almost exclusively to provide course materials and to facilitate all forms of communication and idea exchanges among students and between the stu- dents and their instructor (Driver). Though students and their instructor are likely to meet face-to-face in Web- centric learning environments, in Web- based environments they can work entirely in different places and at dif- ferent times-that is, asynchronously and at a transactional distance (Driver). The four stages of instructional delivery can be viewed as a continuum of organizational learning require- ments with regard to the institution, which adopts the instructional technol- ogy at each stage. This continuum ranges from a minimal requirement for new organizational learning in the Web-present stage to an extensive requirement in the Web-based stage (Driver). The transition from the Web- centric to the Web-based stage may involve the highest potential for failure for any institution. Though many insti- tutions are being pressured by increas- ing demand to rush to offer Web-based programs (Milliron, 1999), spending additional learning time in the Web- centric stage before doing so may sig- nificantly reduce the risk of failure (Driver, 2000). An understanding of how Web-centric instruction can bene-

fit students and of how students can be assured that hoped-for benefits will accrue at the precursor stage can help institutions prepare for fully Web- based instruction. In this study, I pre- sent the results of two surveys focusing on the effects of Web-centered instruc- tional resources on the learning experi- ence of students over the course of 1 semester.

Specifically, I collected data to inves- tigate the effect of a Web-centric learn- ing environment on the following dimensions, which have been identified previously as critical to student learning at a transactional distance (Barbera,

2000; Moore

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Kearsley, 1996; Porter,1997; Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995; Wegegrif, 1998):

Social interaction and the develop- ment of a community of learners among students and between students and instructor,

Student involvement with the sub- ject matterkourse content,

Students’ development of technical skills for using Internet-based learning tools and communicating in electronic environments, and

Overall class learning experience.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Course Details

The course featured a Web site built on a Blackboard platform and offered the following resources to students: an announcement page, an online syllabus, lecture slides with audio comments, online readings, links to other sites and resources, audiohideo clips from previ- ous student presentations, a student e- mail roster, a general discussion board, several group discussion boards for work on group projects, and a chat room. The course was designed with the assumption that most of the course- related interaction would take place at a distance, with students conducting course discussions from their own com- puters at home and at work or from campus computer labs at their own leisure and pace. The students were pre- dominantly working professionals and attended the MBA program on a part- time basis. The course was conducted on the campus of a regional university in the southeastern United States and dealt with the management of change in

today’s business organizations. It was broadcast via two-way interactive tele- vision simultaneously to students at four different locations. Though content presented to students on the Web was reviewed and discussed during the tele- vised section, discussions on content occurred mainly on the discussion board; therefore, the course could be

described as Web-centric.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Method

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I designed

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an exploratory study to measure, at least tentatively, the impactof Web-centric learning environments on student outcomes. My purpose was strictly to see if expected student out- comes would indeed fall in the direction indicated by prior research. I adminis- tered exploratory surveys to a group of graduate students enrolled in an MBA course entitled Managing Organization- al Change. These students had never had either an online course or signifi- cant prior experience with Web-centric learning. The survey instrument consist- ed of 36 questions on 3-point Likert- type scales and 1 open-ended question for additional comments. The survey was administered twice, during the 1st and the last 2 weeks of class, to a total of 38 students. If any individual student failed to complete the survey the 1st or 2nd time around, that student’s data were eliminated from the final set of usable responses. (See Appendix for a list of the survey questions.) The sur- veys were anonymous, and the instruc- tor did not have access to the results until after the course was over and grades turned in (an assistant checked the responses and collected the data, so

that the students’ anonymity would be completely preserved). Thirty-four stu- dents filled out the survey at both administrations, resulting in 34 respon- dents who provided complete informa- tion out of an original 38.

Results

I examined the study results with regard to the effects of Web-centric learning environments on four student dimensions: social interaction, involve- ment with the course content, technical skills, and overall learning experience.

MurcWApril2002 237

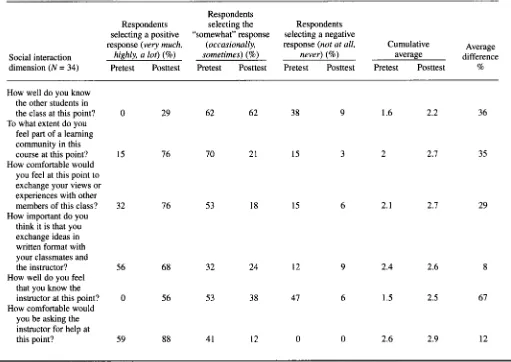

TABLE 1. Percentages, Cumulative Averages, and Percentage Differences From First Survey Administration

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

RespondentsRespondents selecting the Respondents

selecting a positive “somewhat” response selecting a negative

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

highly, a

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Zot)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(%) sometimes) (%) never) (%) average difference Averageresponse (very much, (occasionally, response (not at all, Cumulative Social interaction

dimension ( N = 34)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest %How well do you know the other students in

the class at this point?

To what extent do you

feel part of a learning

community in this course at this point? How comfortable would

you feel at this point to exchange your views or

experiences with other members of this class?

How important do you think it is that you exchange ideas in

written format with your classmates and

the instructor? How well do you feel

that you know the

instructor at this point? How comfortable would

you be asking the instructor for help at

this point?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0 29 62 62 38 9 1.6 2.2 36

15 76 70 21 15 3 2 2.7 35 32 76 53 18 15 6 2.1 2.7 29

56 68 32 24 12 9 2.4 2.6 8

0 56 53 38 47 6 1.5 2.5 67 59 88 41 12 0 0 2.6 2.9 12

The Effects

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Web-Centric Learning Environments on Student SocialInteraction

Social interaction in a course encom- passes both student-to-student and stu- dent-to-instructor interactions and has been identified as a critical dimension of effective learning environments (Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995; Wegegrif, 1998). In fact, the extent to which stu- dents and instructors are able to build a community of learners will positively affect the students’ involvement with the course and the absorption and application of concepts presented (Wegegrif, 1998). A community of

learners refers to a group’s perception that all members share the responsibili- ty for teaching and learning and that they can learn by freely sharing ideas and experiences within the group (Wegegrif)

.

The survey contained several ques-

tions asking students about their percep- tions with regard to social interaction and the development of a community of learners within the class. In Table 1, I show the results for these questions for the first administration of the survey, labeled “pre” for pretest, and for the second administration, labeled “post” for post test.

In Table 1, I present the responses to the questions by percentage of respon- dents, the cumulative average response for each question, and the percentage differences between the first and second administrations of the survey. I comput- ed the cumulative average responses by adding the point values for each respon- dent’s answer (e.g., a rating of “highly effective” equaled three points on a 3-

point Likert-type scale) and dividing that by the number of respondents. I computed the percentage differences between the pre-and posttest averages by calculating the difference between the

pre-and posttest averages and then divid- ing it by the average for the pretest to show the percentage by which responses changed when compared with the begin- ning of the semester. According to the data in Table 1, there was a noticeable effect on students’ perceptions of the level of social interaction in the class. Prior to taking the class, students felt that they did not know each other very well and did not feel part of a learning com- munity. By the end of the course, they felt strongly that they knew each other and were part of a community of learn- ers. They also felt very comfortable with exchanging their views with each other and believed that they knew the instruc- tor much better by the end of the class. All of these results seem to indicate that the Web-centric learning environment had a positive effect on students’ social interaction and that it indeed facilitated the development of a community of

learners, as has been claimed in earlier

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

238

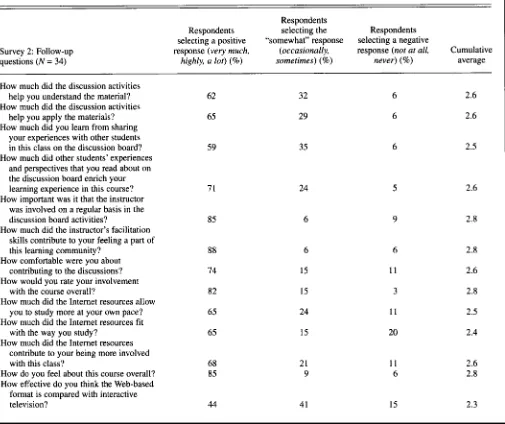

Journal of Education for Business [image:4.612.53.564.61.423.2]TABLE 2. Percentages and Cumulative Averages From Second Survey Administration for Follow-Up Questions

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Survey

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2: Follow-upquestions

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( N =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

34)Respondents

Respondents selecting the Respondents selecting a positive “somewhat” response selecting a negative

response

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(very much, (occasionally, response (not at all, Cumulativehighly, a lot) (%) sometimes) (%) never) (%) average How much did the discussion activities

help you understand the material? How much did the discussion activities

help you apply the materials? How much did you learn from sharing

your experiences with other students

in this class on the discussion board? How much did other students’ experiences

and perspectives that you read about on the discussion board enrich your learning experience in this course? How important was it that the instructor

was involved on a regular basis in the discussion board activities?

How much did the instructor’s facilitation

skills contribute to your feeling a part of

this learning community? How comfortable were you about

contributing to the discussions? How would you rate your involvement

with the course overall?

How much did the Internet resources allow you to study more at your own pace? How much did the Internet resources fit

with the way you study?

How much did the Internet resources contribute to your being more involved with this class?

How do you feel about this course overall? How effective do you think the Web-based

format is compared with interactive television?

62 65 59

71

85

88 74

82 65 65 68 85

32 29 35

24 6 6 15 15 24

15

21 9

5 9 6

1 1

3

11

20

1 1

6

2.6 2.6 2.5

2.6 2.8 2.8 2.6 2.8 2.5 2.4 2.6 2.8

44 41 15 2.3

research (Hiltz & Wellman, 1997; Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995).

Some follow-up questions were also asked at the second survey administra- tion-that is, after the students had completed the course work (see Table

2 ) . Responses to these follow-up ques-

tions also support the finding that the Web-centric learning environments had a positive effect on students’ social interaction. I present these percentages and cumulative averages in Table 2.

The data in Table 2 indicate that the Web-centric instructional format in which social interaction took place pri- marily via Internet-based resources was an effective means for building a com- munity of learners in this class. When comparing the Web-based format with

interactive television, over 40% of the respondents described the Web-based format as highly effective and over 40% described it as somewhat effective. This response indicates that (a) interactive television, though more resource intense for the institution, is not neces- sarily a more effective tool for the deliv- ery of distance education and (b) invest- ments into less capital-intensive, Web-based tools may have at least equal or greater benefits for student learning. Another apparent finding shown in Table 2 is that the course format result-

ed in a significant level of student involvement: Nearly 90% of the respon- dents rated their involvement with the course as high. Because only 68% of the

respondents rated the Internet resources

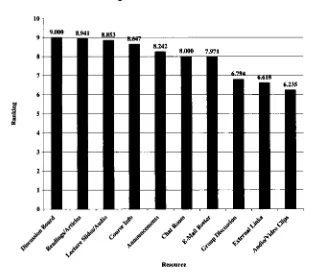

as contributing to this involvement, it is likely that the activities that took place; the instructors’ facilitation online (rated as important by over 80% of the respon- dents); and the ideas shared with other students online (rated as important to the learning experience by over 70%) contributed significantly to student involvement with the course. Further evidence for the importance of Web- centric instructional resources for social interaction is seen in the respondent rankings of the effectiveness of the var- ious learning tools provided on the Web site. I present these rankings in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, respondents selected the discussion board as the most effective of the 10 learning tools provided to them on the Web site. On

MarcWApril2002 239

[image:5.612.60.565.55.479.2]FIGURE 1. Student Rankings of Internet Resources

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

lo 1

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

OD

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

B

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. Averages

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

are based on ratings on a scale ranging from 1 (least valuable) to 10 (most valuable).average, the respondents gave the dis- cussion board a score of 9 on a scale ranging from 1 (least effective) to 10

(most effective). The discussion board was in fact at the heart of the Web-cen- tric learning environment and was the students’ main source of interaction in the course, with over 90% of the stu- dents accessing the discussion board at least once a week. Over 90% of the stu- dents also accessed the lecture slides either once at the beginning of the semester to download and print out the slides or weekly to view the slides on- line. Over 90% of the students viewed the readings and articles online on a weekly basis and accessed course infor- mation at least once during the semes- ter. All students accessed the announce- ment section every time they logged on, whereas the chat room was used only once by all class members. Over 80% of the students used the e-mail feature on a regular basis, and over 70% used the group discussion pages. External links and audiohideo clips were accessed by only over 10% of the students, indicat- ing that students did not spend signifi- cant time on nonessential activities and had some trouble downloading the pre-

sentations because of their computer set-ups or connection speeds.

The Effects of Web-Centric Learning Environments on Students’ Involvement With Course Content

Previous research has suggested that Internet resources and Web-centric learning environments have a positive effect on students’ level of involvement with course content (Andriole, Lytle, &

Monsanto, 1995; Freberg, 2000; Hiltz &

Wellman, 1997). Internet resources have been found to enhance students’ level of comprehension of materials and increased their perceptions of the mate- rials’ relevance (Gaud, 1999). Re- searchers have also found that Internet resources encourage students to engage in more active learning by providing more opportunities to “interact with the core concepts” (Freberg, 2000, p. 48). Additionally, Web-centric learning envi- ronments have been found to enhance student class preparation and make in- class note taking easier for students, thereby helping them to use lectures more effectively and to listen more actively (Karuppan & Karuppan, 1999)

This study’s exploratory survey results, shown in Table 3, support this

previous research. As can be seen from the percentages for each answer on the first and second administrations of the survey as well as from the cumulative averages for each question and the per- centage difference between the aver- ages, students’ level of involvement with the course content improved noticeably. Though the interest in the course con- tent and the relevance of the subject mat- ter were rated as high from the beginning by over 60% of students, their knowl- edge of the subject matter increased dra- matically. Before taking the course, 7 1 %

of the students indicated that they had only some knowledge of the course’s subject matter+rganizational learning and change-but none of the students felt that they knew a great deal about it. By the end of the course, 85% of the stu- dents felt that they knew a great deal about the subject matter. This result seems to indicate that the Web-centric environment was an effective means for facilitating student learning.

Follow-up questions asked in the sec- ond survey administration and presented in Table 2 provide a little more insight into exactly how the Web-centric envi- ronment may have increased the level of student involvement with the course content. At the end of the course, over 90% of the respondents indicated that the discussion activities on the Web site had helped them in understanding and applying the materials. Over 90% indi- cated that they learned from sharing experiences with other students. Over 80% stated that the Internet resources fit with the way they studied and allowed them to study more at their own pace. Finally, 82% of the respondents rated

their overall involvement with the course as high. These results seem to indicate that Web-centric learning environments, particularly subject-related resources, have a positive effect on student involve- ment with the course content.

The Effects of Web-Centric Learning Environments on Students’

Technical Skills

Technical skills with regard to using computers and functioning effectively in electronic environments have been

240 Journal of Education for Business

[image:6.612.50.361.52.324.2]TABLE 3. Percentages, Cumulative Averages, and Percentage Differences From First Survey Administration for

Responses to Questions Relating to Student Involvement With the Course Content

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Respondents

Respondents selecting the Respondents selecting a positive “somewhat” response selecting a negative

Involvement with response

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(very much, (occasionally, response (not at all, Cumulative Averagecourse content highly, a lot) (%)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

sometimes) (%) never) (%) average differencedimension ( N = 34)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest %How much do you know

at this point about

organizational learning and change

management? 0 85 71 9 29 6 1.7 2.8 64

How much is the subject area (organizational

learning and change)

of interest to you at

this point? 65 76 32 18 3 6 2.6 2.1 4

How relevant is the

subject area to your

professional

development? 65 71 32 24 3 6 2.6 2.6

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0identified as critical for college stu- dents-not just as a basic educational standard but as a requirement for obtaining attractive and well-paying jobs (Furnell, Evans, Phippen, & Abu- Rgheff, 1999; Marsick, 1998; Young, 1998). Computer literacy, together with the ability to communicate effectively in virtually connected work groups, may become a prerequisite for most jobs in the near future (Marsick, 1998). Web- centric and Web-based learning envi- ronments are uniquely suited to provide such technical skills as part of the cur- riculum, and the participation of stu- dents in Internet-oriented courses should positively affect such skills (Schultz, 1998; Young, 1998).

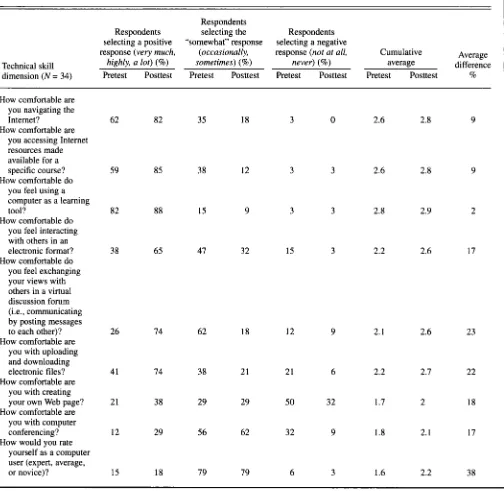

My exploratory survey results, shown in Table 4, seem to demonstrate these previous claims. As can be seen from the percentages for each answer on the first and second survey administration as well as from the cumulative averages for each question and the percentage difference between the averages in Table 4, there was an apparent notice- able effect on students’ technical skills. At the beginning of the course, only a little over half of the students were com- fortable navigating the Internet and accessing resources made available on a course Web site. By the end of the

course, over 80% of the respondents felt comfortable navigating the Internet and accessing Web resources. Eighty-eight percent felt positive about using a com- puter as a learning tool (up from 82% in the pretest), and over 60% felt comfort- able interacting with others in an elec- tronic format (up from 38% in the pretest). By the end of the course, over 70% of the students were comfortable exchanging their views with others in a virtual discussion format (up from 26% in the pretest) and uploading and down- loading electronic files (up from 41% in the pretest). All of this indicates that, by the end of the course, students had sig- nificantly increased their perceived competencies with regard to working in electronic environments-competencies that are critical in the workplace today.

The Effects

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Web-Centric Learning Environments on Students’ OverallLearning Experience

Previous research has suggested that Web-centric and Web-based learning environments have a positive effect on students’ overall learning experience (Andriole, Lytle, & Monsanto, 1995; Barnes, Sims, & Jamison, 1999; Fre- berg, 2000; Gaud, 1999; Hiltz & Well- man, 1997; Karuppan & Karuppan,

1999). In one study, researchers found that students in Web-centric learning environments felt that they learned more and that this environment was more exciting than traditional instruc- tion (Andriole). In another study, researchers found that students in Web- centric environments were more satis- fied than those in a traditional class- room and that their overall mastery of the material was equal to or greater than the mastery that students gained in a tra- ditional classroom (Hiltz & Wellman, 1997). Therefore, one would expect that Web-centric environments have a posi- tive effect on the students’ overall learn- ing experience.

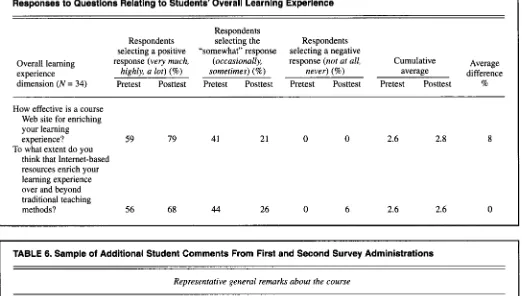

My exploratory survey results, shown

in Table 5, seem to support these find- ings. As can be seen from the percent- ages for each answer on the first and second survey administrations, as well as from the cumulative averages for each question and the percentage differ- ences between the averages in Table 5, there was a noticeable effect on stu- dents’ overall learning experience. At the beginning of the semester, 59% of the respondents expected that the Web site for the course would enrich their learning experience, and 56% thought that the Internet-based resources would enrich their learning experience over

MarcWApril2002 241

[image:7.612.51.566.59.310.2] [image:7.612.50.568.68.311.2]TABLE 4. Percentages, Cumulative Averages, and Percentage Differences From First Survey Administration for

Responses to Questions Relating to Students’ Technical Skills

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Technical skill

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Respondents

Respondents selecting the Respondents

selecting a positive “somewhat” response selecting a negative

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

highly, a lor) (%)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

sometimes) (%) never) (%) average difference response (very much, (occasionally, response (nor at all, Cumulative Averagedimension ( N = 34) Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest %

How comfortable are you navigating the Internet?

How comfortable are you accessing Internet resources made available for a specific course? How comfortable do

you feel using a computer as a learning tool?

How comfortable do you feel interacting with others in an electronic format? How comfortable do you feel exchanging your views with others in a virtual discussion forum (i.e., communicating by posting messages to each other)? How comfortable are

you with uploading and downloading electronic files? How comfortable are

you with creating your own Web page? How comfortable are

you with computer conferencing ?

How would you rate yourself as a computer user (expert, average, or novice)?

62 82 59 85

82 88 38 65 26 74 41 74 21 38 12 29

15 18

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

35

38 15 41 62 38 29 56 79

18 3 12 3 9 3 32 15

18 12 21 21 29 50 62 32 79 6

0 2.6 3 2.6 3 2.8 3 2.2 9 2.1 6 2.2 32 1.7 9 1.8 3 I .6

2.8 2.8 2.9 2.6 2.6 2.7 2 2.1 2.2

9 9 2 17 23 22

18

17 38

and beyond traditional teaching meth- ods. By the end of the course, 79% of

the respondents thought that the Web site did enrich their learning experience, and 68% believed that the Internet resources enriched their learning experi- ence more than traditional instructional resources had. These results seem to indicate that the Internet resources pro- vided had the desired effect on student learning outcomes and enriched student learning significantly. This positive effect was also evident in various com-

ments made on the survey at both administrations (see Table 6 for a repre- sentative sample of these comments).

Comments on the survey adminis-

tered at the beginning of the class indi- cated that students were excited about using the Internet as a learning tool and about learning to use new technologies and functioning effectively in electronic environments. In comments on the sur- vey administered at the end of the class, students remarked on the Web-centric environment’s overall superiority as a

learning tool compared with televised and traditional classes. The students also stated that the Web-centric format was convenient to their busy life styles, called it an “exciting and innovative way of obtaining an education,” and rated the course as the “highest ranking in involvement, knowledge and learning opportunities.” These comments indi- cate that the course format was per- ceived by students as having a signifi- cantly positive effect on their experience, not just on how and when

242 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Business [image:8.612.61.565.65.556.2]TABLE 5. Percentages, Cumulative Averages, and Percentage Dlfferences From First Survey Administration for

Responses to Questions Relating to Students’ Overall Learning Experience

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Respondents

Respondents selecting the Respondents selecting a positive “somewhat” response selecting a negative

Average Overall learning

experience

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

highly, azyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

lot) (%)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

sometimes) (%) never) (%) average difference response (very much, (occasionally, response (not at all, Cumulativedimension ( N = 34) Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest %

79 41

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

21 0 0 2.6 2.8How effective is a course Web site for enriching your learning

experience? 59 8

think that Internet-based resources enrich your learning experience over and beyond traditional teaching

methods? 56 68 44 26 0 6 2.6 2.6 0

To what extent do you

TABLE 6. Sample of Additional Student Comments From First and Second Survey Administrations

Representative general remarks about the course

Pretest Posttest

I am very glad that you are taking the initiative and utilizing I like this class format because everyone has an equal chance the extensive technology available to us to enhance your

course. Your class is the first class I have taken in the MBA program (and I only have three classes left after this Spring)

that had anything like this. I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

am sure it will be a great benefit while working on group projects because it is always difficultto get everyone together. Also, being able to access all the class notes and other information will be very convenient.

to contribute. In most traditional classes, one or two people contribute while everyone else listens or loses interest. I feel you should be commended for putting together this

course using the Internet. Graduate students complained of not having enough time to complete course work and projects due to their work schedules, and you listened and have done some-

thing about it. technology.

Probably the best course I have ever attended. Highest rank- ing in course materials, course content, instructor preparedness, instructor optimism, involvement and knowledge, learning opportunities, new learning methods, and application of new I am most appreciative of the opportunity to be using the I really enjoyed this class, and it was a refreshing experience. Internet as a learning tool. Thanks.

My humble opinion is that this an exciting and innovative way of obtaining an education. Utilizing technologies such as these by means of a course puts one in the driver’s seat for uti- lizing it more creatively on the job. I think this is splendid!

The Internet helped me stay involved with the class and keep up to date while I was dealing with some very dificult prob- lems at work and was not able to attend class.

I look forward to taking this class, and feel it will strengthen I thoroughly enjoyed the class. I feel that the discussion board was very helpful to my understanding the material. After reading what others had to say on the discussion board, I was able to have a greater understanding of the course material. my abilities as far as the Internet is concerned. I also feel that

the course will provide an alternative approach to conversing among students and may therefore facilitate ideas that may not have been presented or considered before.

I think that this is a wonderful idea! I work full time and

have a hard time scheduling group meetings. Being able to meet via the Internet (and sit at home in my pajamas) will be very convenient for me. Also, I look for any ways to improve my computer and Internet knowledge.

I have to say that the Internet is a much more effective tool than television classes or even regular class settings.

MarcWApril2002 243

[image:9.612.47.569.57.353.2]they learned, but also on their level of

involvement and enthusiasm overall.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Conclusion

The results of this exploratory study indicate, at least tentatively, that Web- centric learning environments have a positive effect on student social interac- tion, involvement with course content, technical skills, and overall learning experience. Consequently, if an institu- tion that is moving toward Web-based course offerings can experiment with Web-centric instructional methods and validate that these outcomes are indeed accruing to students, the institution should be in a good position to move further toward distance teaching. Alter- natively, even if an institution is not cur- rently in a position to offer fully Web- based programs, the institution may still find it worthwhile to supplement its reg- ular offerings with Web-centric instruc- tional methods because of the benefits that students seem to derive from this format.

Nevertheless, some limitations of the study and potential concerns over the use of Web-centric learning environ- ments should be noted. First of all, the sample in this study was very small, consisting of only 34 respondents.

Therefore, these finding may not be generalizable to larger or other student populations. Second, because of the sample size, the ordinal nature of the data collected in the survey, the pres- ence of only three answer categories on the response scales, and the absence of inferential statistics used for their inter- pretation, the potential validity of the findings is questionable for populations outside the sample itself. More research based on larger sample sizes, more response categories, and more inferen- tial statistics for examining the reliabili- ty and validity of potential findings needs to be undertaken on the benefits and shortcomings of Web-centric instruction. However, this study still makes an important contribution as an example of the kind of investigation that business schools should undertake before offering instruction entirely based on the Internet. As my results in this study show, the benefits of precursor forms of Web-oriented instruction must

be carefully examined, and student dents in Web-centric courses, they are learning outcomes must be validated, not likely to materialize in Web-based before the organization can consider courses. Therefore, it is critical that the itself ready for such a step. If the hoped- organization validate such outcomes for outcomes for student learning before continuing its move toward more

offered at a distance do not accrue to stu- course offerings at a distance.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

APPENDIX. The Survey Questions

1.

2. 3.

4.

5.

6. 7.

8. 9. 10. 11.

12.

13.

14.

15. 16.

17.

18. 19. 20.

21.

22.

23.

24. 25. 26.

27.

28.

How effective is a course Web site for enriching your learning experience? How comfortable are you navigating the Internet?

How comfortable are you accessing Internet resources made available for a

specific course?

How comfortable do you feel using a computer as a learning tool?

How comfortable do you feel interacting with others in an electronic format? How comfortable do you feel exchanging your views with others in a virtual discussion forum (i.e., communicating by posting messages to one another)? How comfortable are you with uploading and downloading electronic files? How comfortable are you with creating your own Web page?

How comfortable are you with computer conferencing?

How well do you know the other students in this class at this point? How much do you feel part of a learning community in this course at this point?

How comfortable would you feel at this point to exchange your views or

experiences with other members of this class?

How much do you know at this point about organizational learning and change management?

How much is the subject area (organizational learning and change) of interest to you at this point?

How relevant is the subject area to your professional development? How important do you think it is that you exchange ideas in written format with your classmates and the instructor?

To what extend do you think that Internet-based resources enrich your learning experience over and beyond traditional teaching methods?

How well do you feel you know the instructor at this point?

How comfortable would you be asking the instructor for help at this point?

At this point, do you foresee any barriers to using an Internet Web site as a learning tool in this course? If yes, please explain.

How would you rate yourself as a computer user:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

expert (3), average (2), ornovice (l)?

How do you feel about this course being offered entirely online via the

Internet?

Please rank each of the resources used in this course for its effectiveness as a learning tool for you, on a scale ranging from 10 (most effective) to

2 (not effective at all):

a. Announcement page

b. Course information (syllabus online) c. Lecture slides with audio comments d. Readings/articles on line

e. Links to other sites and resources

f. Audiohide0 clips from previous student presentations

g. E-mail roster of students h. Discussion board

i. Group discussion boards j. Chat room

How much did the discussion activities help you understand the material? How much did the discussion activities help you apply the materials? How much did you learn from sharing your experiences with other students in

this class on the discussion board?

How much did the other students’ experiences and perspectives that you read about on the discussion board enrich your learning experience in this course? How important was it that the instructor was involved on a regular basis in the

discussion board activities?

continued

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

on next page244 Journal of Education for Business

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

APPENDIX

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Continued)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

29.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

How much did the instructor’s facilitation skills contribute to your feeling a30. How comfortable were you about contributing to the discussions? 3 1. How would you rate your involvement with the course overall?

32. How much did the Internet resources allow you to study more at your own

33. How much did the Internet resources fit with the way you study?

34. How much did the Internet resources contribute to your being more involved

35. How do you feel about this course overall?

36. How effective do you think the Web-based format is compared with interactive

37. Please make any additional comments:

part of this learning community? pace?

with this class? television?

REFERENCES

Andriole, S. J., Lytle, R. H., & Monsanto, C. A. (1995). Asynchronous learning networks:

Drexel’s experience.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Technological Horizons inEducation, 23(3), 97-102.

Barbera, E. (2000). Study actions developed in a virtual university. Virtual University Journal, 3, 3 1 4 2 .

Barnes, D. M., Sims, J. P., & Jamison, W. (1999). Use Of Internet-based resources to support an introductory animal and poultry science course. Journal of Animal Science, 77(5), 1306-1314. Driver, M. (2000). Integrating Internet-based

resources into classroom instruction: An orga-

nizational learning approach. Journal of Busi-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ness Education, 1(Spring), 1 4 3 0 .

Dunn, S. (2000). The virtualizing of education. The Futurist, 34(2), 34-38.

Freberg, L. (2000). Integrating Internet resources

into the higher education classroom. Syllabus,

Furnell, S. M., Evans, M., Phippen, A,, & Abu- Rgheff, M. (1999). Online distance learning: Expectations, requirements and barriers. Virtual University Journal, 2(2), 34-48.

Gaud, W. S. (1999). Assessing the impact of Web Courses. Syllabus, NovemberDecember 49-50 Hiltz, S. R., & Wellman, B. (1997). Asynchro- nous learning networks as a virtual Classroom. Comrnunications of the ACM, 40(9), 44-50. Horvath, A,, & Teles, L. (1999). Novice users’

reactions to a Web-enriched classroom. Virtual University Journal, 2(2), 49-57.

Karuppan, C. M. , & Karuppan, M. ( 1999). Empirically based guidelines for developing teaching materials on the Web. Business Com-

munication Quarterly,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

62(3), 37-45.Kessler, D. A,, & Keefe, B.(1999). Going the dis- 13(7), 48-50.

tance. American School & University, 7(1 I), 44-47.

Marsick, V. J. (1998). Transformative learning from experience in the Knowledge Era. Daedalus, 127(4), 119-137.

McGinn, D. (2000). College online. Newsweek, 135(17), 54-58.

Milliron, M. D. (1999). Enterprise vision: Unleashing the power of the Internet in the edu- cation enterprise. Technological Horizons in Education, 27(1), 26-29.

Moore, M. G., & G . Kearsley. (1996). Distance education, a systems view. Boston: Wadsworth Publishing.

Porter, L. R. (1997). Creating the virtual class- room: Distance learning with the Internet. New York: Wiley.

Roach, R. (1999). The higher education technolo- gy revolution. Black Issues in Higher Educa- tion, 16(13), 92-97.

Rohfeld, R. W., & Hiemstra, R. (1995). Moderat- ing discussions in the electronic classroom. In Z. L. Berge & M. P. Collins (Eds.), Computer- mediated communication and the on-line class- room in distance education. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Schultz, K. (1998). Using integration models. Techniques, (November), 48-50.

Sistek-Chandler. C. (2000). Webifying courses: Online education platforms. Converge, (April), 34-38.

Weber, J. (1999, October 4). School is never out. Business Week, 164-168.

Wegegrif, R. (1998). The social dimension of asynchronous learning networks. JAWV, 2( I ) ,

Young, J. (1998). Computers and teaching: Evolu- tion of a cyberclass. Political Science & Poli- tics, 31(3), 568-573.

1-17.

MarcWApril2002 245